1. Introduction

The human–dog bond is one of the oldest and most deeply rooted interspecies relationships, evolving over thousands of years and manifesting in a variety of forms. Dogs (

Canis lupus familiaris) were among the first animals domesticated by humans, with archaeological evidence suggesting a partnership dating back over 15,000 years [

1]. Initially used for hunting and guarding, selective breeding led to the development of specific traits that made dogs suitable for specialized work. A quote by Anderson and Lebiere (1998: 60-61) mentions that “at no time in an individual's life will he steadily be in the company of one another, be it mother, friend, mate, or child...The exceptional indelible relationship is between a person and his dog companion.” [

2]

(pp. 60–61)

Among these human-dog relationships, the dynamic between working dogs and their human partners stands out as a particularly unique and complex dynamic that differs significantly from the typical bond seen between pet dogs and their owners. Working dogs play critical roles in various domains due to their olfactory acuity, trainability, and social intelligence. However, their success is often not purely a function of individual skill, but of the quality of the relationship between dog and handler. Bonding in human-working dog teams fosters trust, enhances communication, and improves resilience under pressure [

3]. As organizations increasingly rely on canine teams, understanding the relational dynamics between handlers and dogs becomes vital for performance and welfare. While pet dogs are mainly kept for companionship, comfort, and emotional support within the home, working dogs are specifically trained to perform skilled tasks that require a high level of cooperation and communication with their human handlers.

Research indicates that the human–dog bond activates oxytocin pathways in both species, reinforcing attachment and cooperative behaviors [

4]. This mutual hormonal response is comparable to the parent–infant bond in humans and is thought to facilitate trust and communication. This is amplified in the working dog team relationship. One of the defining characteristics of working dog teams is the level of interdependence and mutual trust that develops between the dog and the handler. Unlike a standard pet-owner relationship, where the primary focus is on affection and care, the working dog partnership is built around achieving shared goals. The handler must be able to interpret the dog’s body language, signals, and subtle cues accurately, while the dog must be responsive, adaptable, and able to perform under varying and sometimes stressful conditions. This requires extensive training for both the dog and the handler, fostering a relationship that is as much about teamwork and professionalism as it is about companionship [

5]. Handlers use verbal commands, body language, and rewards to shape behavior, while dogs respond to subtle cues and changes in tone [

6]. Miscommunication or a weak bond can lead to decreased task performance and increased stress for both partners.

Specific stories highlight the depth and diversity of these working dog partnerships, particularly in military contexts. For example, “Lucca,” a Marine Corps explosives detection dog, completed over 400 missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, saving countless lives by detecting improvised explosive devices. Her handler described their relationship as one of “absolute trust,” where each relied on the other for safety and support [

7]. Similarly, one of the most moving examples of the human-canine bond in military service, is the story of Corporal Megan Leavey and her bomb-sniffing partner, Sergeant Rex. Paired during her time in the U.S. Marine Corps, Leavey and Rex served through over 100 missions in Iraq, including high-risk patrols in Fallujah and Ramadi. Their connection was forged under fire, both were injured by an improvised explosive device (IED) during a mission, yet their commitment to each other and their duties never faltered. After returning home, Leavey faced years of emotional and bureaucratic hurdles in her effort to adopt Rex, who remained on active duty. Her persistence paid off when Rex was medically retired, and the two were finally reunited. Though their time together in retirement was short, it was filled with comfort, peace, and the kind of loyalty that only grows through shared sacrifice. Their story, later portrayed in the film

Megan Leavey, stands as a powerful testament to the profound bond between working dogs and their handlers, one rooted not just in duty, but in deep, mutual devotion. These military partnerships are not only operationally critical but also provide emotional support and companionship to handlers, often helping them cope with the psychological stresses of deployment [

8].

Beyond the military, working dog teams play vital roles in civilian life. In search and rescue, teams like handler Debra Tosch and her dog Abby have been deployed to disaster sites across the United States, where Abby’s keen sense of smell and Tosch’s ability to read her signals have led to the successful location of missing persons. Guide dogs for the visually impaired, such as those trained by organizations like Guide Dogs for the Blind, form partnerships that allow individuals to navigate the world with confidence and independence, relying on the dog’s judgment in complex environments [

5].

A key distinction between working dogs and pet dogs lies in their training, daily routines, and the expectations placed upon them. While pet dogs primarily provide emotional comfort and companionship, working dogs are selected and trained for specific temperaments and skills that suit their intended roles. Their daily lives are structured around training sessions, task performance, and ongoing assessments of their welfare and effectiveness. According to Cobb, the welfare of working dogs is closely monitored, and their handlers are trained to recognize signs of stress or fatigue, ensuring the dogs can perform their duties safely and effectively [

5]. In contrast, pet dogs typically have more relaxed routines and are not required to perform under pressure or in potentially hazardous situations. The relationship with their owners is mostly centered on play, affection, and shared leisure activities, whereas working dog teams are defined by a professional partnership that demands discipline, reliability, and mutual reliance. In the following article, we will focus on one such working dog team dynamic which involves the domain of search and rescue (SAR).

1.1. Search and Rescue Dog Teams

The goal of search and rescue dogs is to utilize their superior olfactory ability as well as agility and speed to locate a lost individual in a way that humans often cannot. Dogs have an extraordinary olfactory capability, which far exceeds that of humans. Dogs can be trained by humans to use such abilities in a variety of fields, with a detection limit often much lower than that of sophisticated laboratory instruments. In SAR, there are three main K9 disciplines. In area/air scent search, the dog typically works off lead and is tasked with finding any human in a large acreage. The advantage here is that the canine partner can cover much more ground than if the human worked by themselves. The second discipline is trailing (sometimes called tracking). This is what many people envision SAR to be. There is a scent article from the missing person that the dog smells and then trails the direction that the person walks. The third discipline is human remains detection/cadaver searching. This could be for a whole body or something as small as a few drops of blood, a single tooth, or a bone. The training is intensive and typically involves hundreds, if not thousands of hours, before the SAR dog team is certified and can be operational on actual searches. The following research study below highlights findings from SAR handlers relating to their experience and the perceptions of the bond that they share with their canine partners as well as the roles and responsibilities associated with the task of locating missing people.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

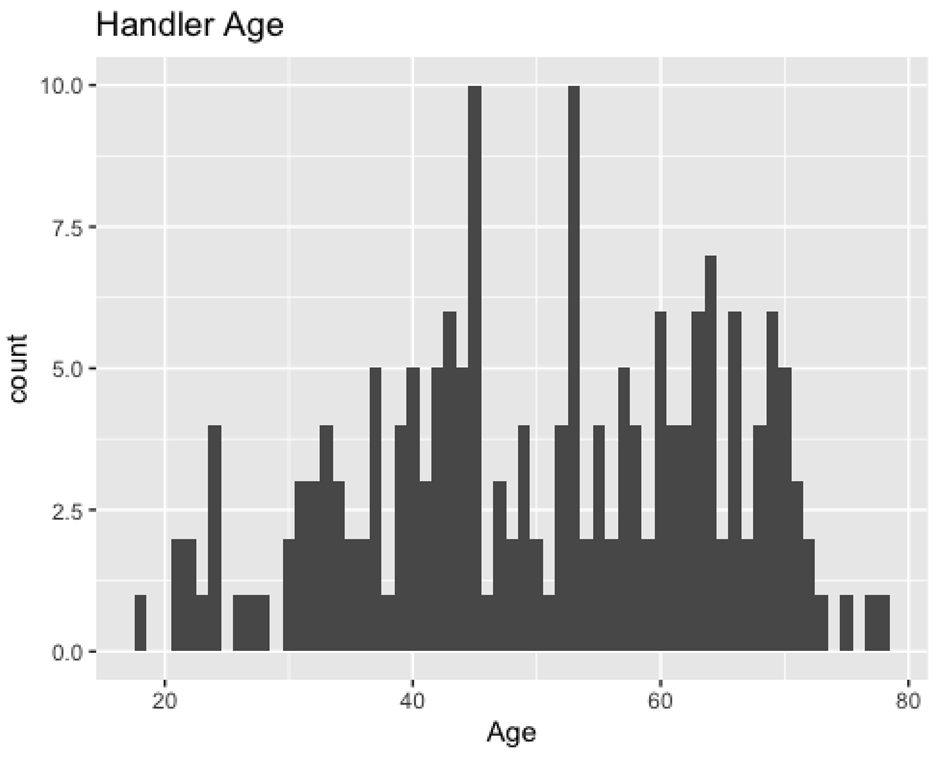

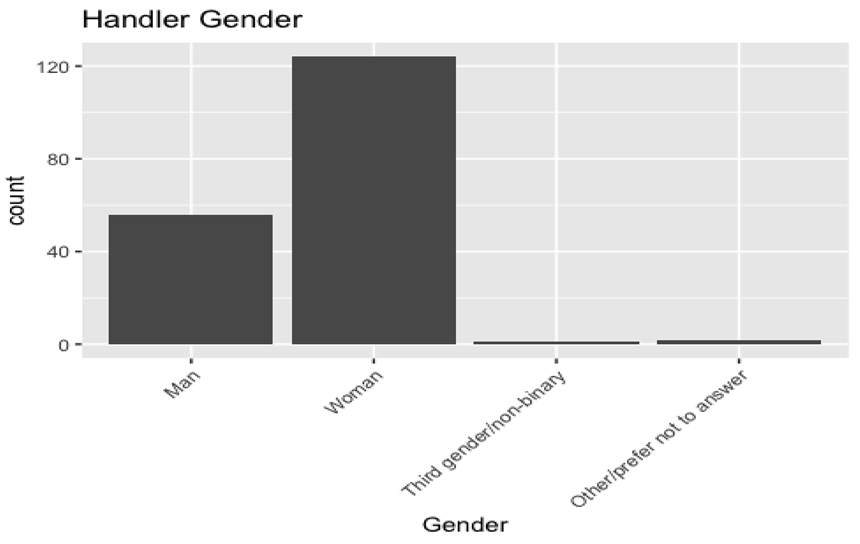

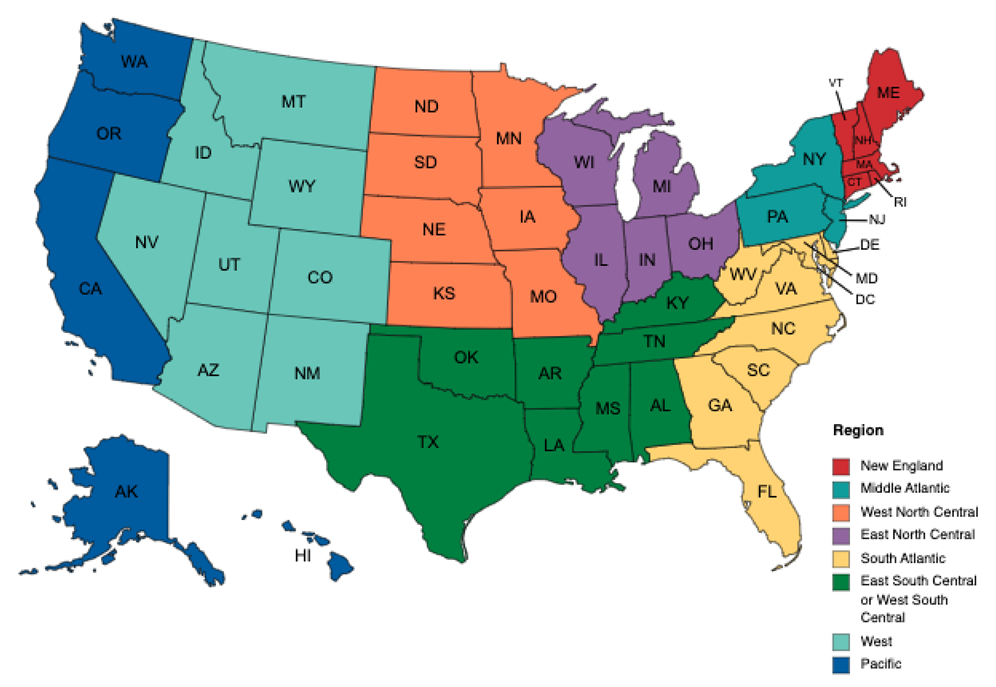

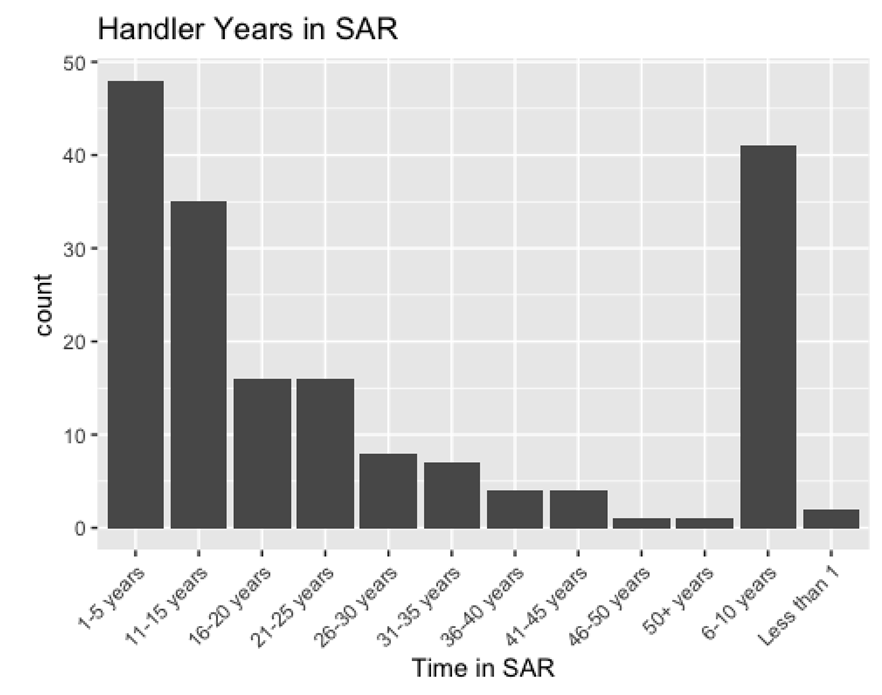

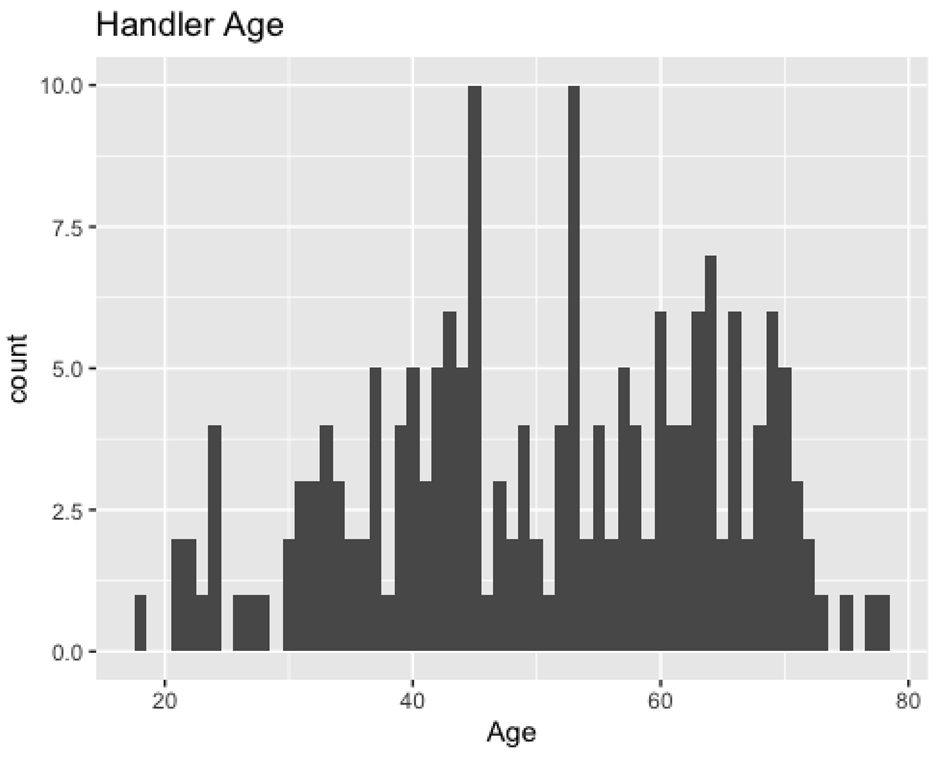

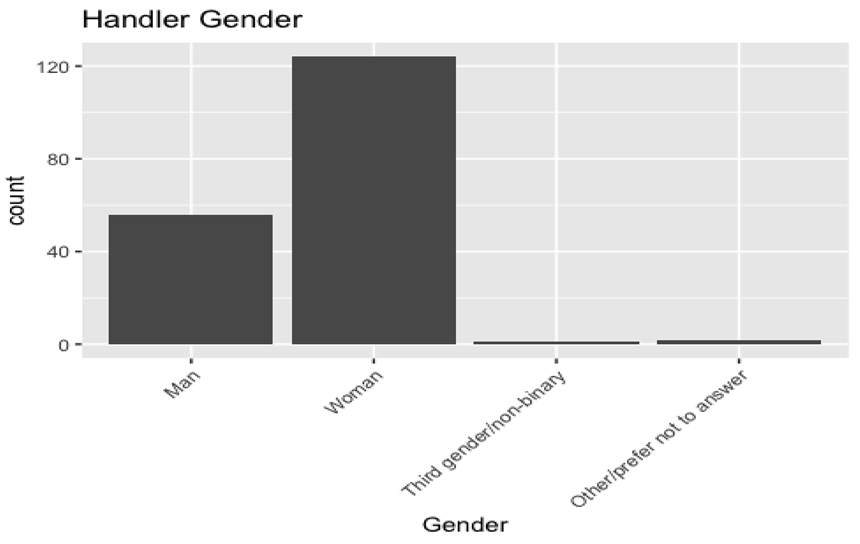

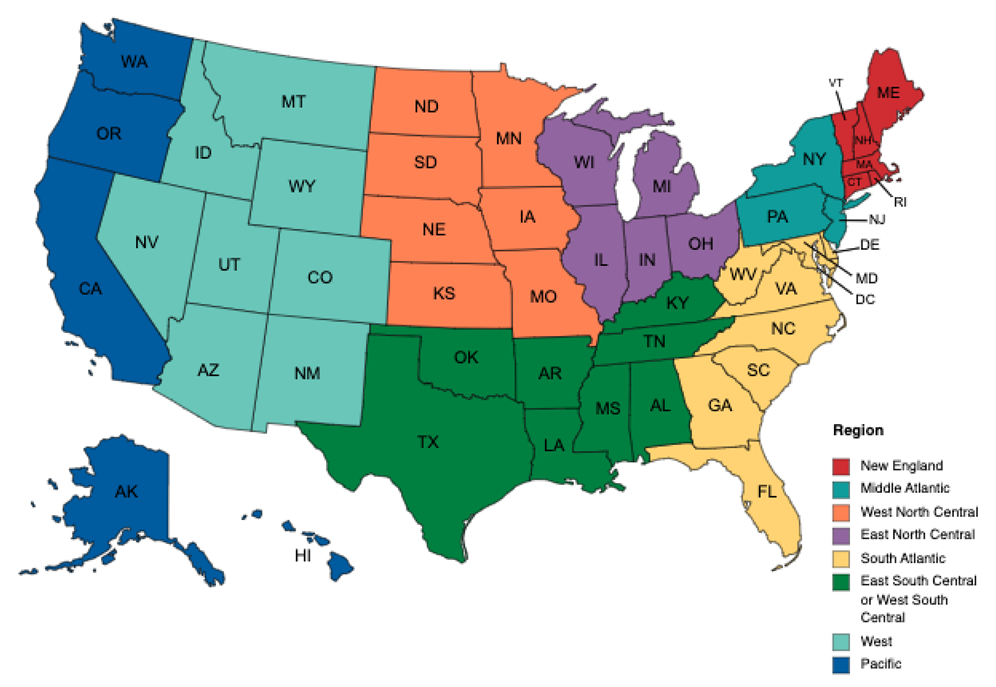

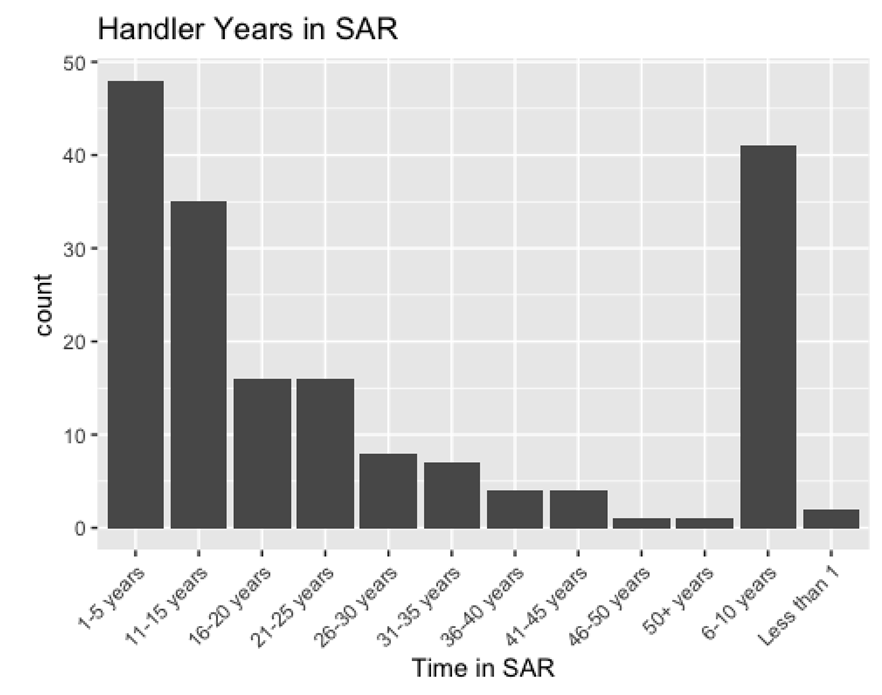

A total of 210 search and rescue dog handlers participated in an online survey. After removing incomplete data, the final dataset included 183 handlers. 56 males, 124 females, 1 non-binary, and 2 preferred not to disclose (Mean age = 50.52, SD = 14.10). Participants were involved in Search and Rescue (SAR) operations, with a mean of 10.5 years of experience (SD = 10.89). Most identified as White (n = 161), with smaller representations from Asian (n = 5), Hispanic/Latino (n = 4), and Bi-racial (n = 4) backgrounds; a few identified as American Indian/Alaska Native or other ethnicities (n = 9), and 7 preferred not to respond. Geographically, respondents were distributed across the U.S., with notable concentrations in the East North Central (n = 25), South Atlantic (n = 27), and West North Central (n = 22) regions; 20 participants lived outside the U.S., and 36 chose not to disclose their region. The group reflected a wide range of SAR engagement, with many participants reporting work in multiple environments, including wilderness (n = 167), rural (n = 128), and suburban (n = 108) settings. On average, participants reported spending nearly 10 hours per week on SAR activities (Mean = 9.89, SD = 6.42), highlighting their significant commitment to this field. See

Table 1 for a summary of the participants’ gender, age, and years of SAR experience. See

Table 2 for a summary of the participants’ ethnic background. See

Table 3 for the geographic regions and operational environments where SAR participants are active. See

Table 4 for the average number of hours per week participants reported spending on SAR activities. See

Table 5 for the distribution of participants’ years of experience in SAR operations. See

Table 6 for a statistical overview of the participants' experience in SAR and with different K9s in SAR.

2.2. Recruitment and Procedure

The participants were recruited through social media and SAR group forum online sources. Their participation was completely voluntary and they were not compensated for their time. Participants initially read and agreed to an informed consent and then completed a series of surveys that included demographic and search and rescue experience questions. A summary table of demographics and SAR experience questions can be found in

Appendix A. The survey questions then focused on the handler’s perceptions of their K9 partner provided in Appendix B.1. For these items, participants were asked to indicate their strength of agreement with the statement using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1= ”Strongly Disagree” to 5 = ”Strongly Agree.” The Likert scale used for these items is presented in Table B.1 in

Appendix B. The online survey took approximately 15-30 minutes to complete.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics were analyzed for the perception study questions. As you can see from

Table 7, handlers overwhelmingly found their K9 partners to be trustworthy, reliable, and enjoyed working with them. K9 handlers also were likely to consider their K9 partner as both a tool and a family member and would want that K9 to search for them if they were missing. The only question that fell below the neutral point and handlers disagreed with was the question regarding the expectation that the K9 should pull more weight on the team than the human.

A One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the relationship between the number of years in search and rescue and how it may influence the handler’s perception of their K9 partner. The only significant finding related to the question “My K9 partner is a member of the family” F(2, 56)= 5.50, p=.006. Post-hoc analysis revealed that the longer the handler was in SAR, the higher their agreement with the idea that the K9 was considered a family member.

An additional One-way ANOVA was also run to look at how the number of hours spent working their K9 partners may influence the handler’s perceptions. In this instance, there were three significant findings. The first had to do with trusting the motives of the K9 and giving it the benefit of the doubt F(4, 56)= 2.70, p=.035. The second significant finding was whether the handler would want their K9 to find them if they were missing F(4, 56)= 5.07, p<.001. The third significant finding related to this question “I rely on my K9 partner more than the other human team members” F(4, 56)= 4.38, p=.003. In each of the following, post-hoc analysis showed that the longer/more hours that the handler worked with their K9 partner, the more likely they were to agree with the statements presented.

An independent samples T-test was conducted to examine how the sex of the handler may impact their perception of their K9s. The only perception survey that produced a significant finding was for the questions “I regularly talk to my K9 partner when on a mission” (t(2,151)=2.33, p=.021). In this instance, females were more likely to talk to their K9 than males were.

4. Discussion

This study clearly shows that the bond between handlers and their working dogs develops over time and with experience. The more time handler-dog dyads spend working together, the more they are able to fine-tune their collaboration, communication, and mutual understanding. The fact that experienced handlers treat their canine partners with the same affection that is generally reserved for family members speaks to the strong emotional bond between them. The handlers get to know their dogs so intimately that they understand the motives behind their actions and behavior. Handlers reported that if they were missing, they would want their own canine to search for them. This demonstrates the strong bond and trust developed in SAR teams. Without faith that one partner is going to protect and look after the other, the efficacy and safety of search and rescue missions would be seriously hindered, as would the wellbeing of handlers and dogs alike.

Handlers reported relying on their canine partners more than on other human team members. This finding may be explained with the nature of search and rescue missions, in which dangerous circumstances can arise suddenly and in which quick action and coordination are often required. In such contexts, the handler and the dog operate as one unit, leveraging each partner’s abilities. Canines can identify scents and cover large areas of ground quickly, while humans interpret their dogs’ signals and let them take the lead. By working together and relying on each other’s strengths, they build a stronger sense of trust. The benefits of such a strong partnership between handlers and their dogs has clear implications for training of both handlers and dogs. Training programs and support programs for SAR teams need to be designed with the human-dog dyad at the center in order to harness the full power of their collaboration.

Limitations of this study include geography and lack of open-ended questions on the survey. All the handlers polled were mainly from the United States (with only a small percentage operating outside the U.S.). A more geographically diverse sample could show if different cultures develop the same attachment to and perception of working dogs. A second limitation is the use of a survey that lacked open-ended questions. Further research into the subject could benefit from including open-ended questions, in which the handlers have the space to describe their lived experience in detail and in their own words. A qualitative analysis of such accounts may uncover new perspectives on the subject matter. Future research may also want to expand the study of handler-dog collaboration by directly observing handler-dog dyads in action and analyzing their interactions. Another avenue for potential research is examining the personalities of handler-dog pairings to identify better matches.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the relationship between working dogs and their humans is distinguished by a blend of emotional closeness, professional collaboration, and shared responsibility. Through real-world examples and research, it is clear that these partnerships not only enhance the effectiveness and welfare of both team members but also demonstrate the remarkable potential of human-animal cooperation in diverse and demanding environments [5, 7, 8].

Research has shown that dogs perform better on detection, tracking, and obedience tasks when bonded with their handlers [

9]. The bond increases motivation, responsiveness, and compliance with verbal and non-verbal cues. Similarly, handlers and dogs with strong relationships show reduced stress markers during simulations and real-world deployments [

10]. Other research has supported the idea that handlers report greater confidence and better decision-making when they feel attuned to their dog’s signals and behaviors. This relational awareness supports adaptive leadership in unpredictable environments [

11]. However, while bonding is beneficial, over-attachment may complicate objectivity or lead to difficulties in retirement or reassignment of the dog. Balancing emotional connection with mission focus requires institutional support, handler training, and clear ethical guidelines [

12].

Our results revealed that increased time spent between handlers and their K9 partners was associated with greater trust and perception of the dog as family. Handlers often expressed a preference for relying on their K9 over a human team member, even identifying they would want their own dog to search for them if they went missing. While gender did not affect overall perceptions of the dogs, female handlers were more likely to talk to their K9 partners than male handlers. These findings emphasize how the bond between humans and working dogs is a dynamic, mutual process that significantly impacts team functionality and welfare. Recognizing and nurturing this bond is not just a matter of emotional connection—it is a scientific and operational imperative. Continued interdisciplinary research into human-animal relationships will enhance the effectiveness, well-being, and longevity of working dog teams.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C.L.; methodology, H.C.L.; formal analysis, H.C.L.; investigation, H.C.L.; data curation, J.R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.L.; writing—review and editing, H.C.L., R.J., S.E., L.H., and J.R.L.; visualization, J.R.L.; supervision, H.C.L.; project administration, H.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Arizona State University (protocol code #00017758 and 03/28/2023).”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Any interested party may contact the authors to obtain the study data for their use.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with this project.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IED |

Improvised Explosive Device |

| K9 |

Canine/dog |

| SAR |

Search and Rescue |

Appendix A

Demographic & SAR Experience Survey Questions

What is your current age (in years)?

What is your race/ethnicity?

What region of the U.S. do you currently live in?

How long (in years) have you participated in Search and Rescue in any capacity?

What type of environment(s) do you typically work in?

What type of environment(s) do you typically work in?

How long (in years) have you worked with any K9 partner for SAR?

How many K9 partners have you worked for SAR (past and present)?

How many hours per week (on average) do you spend taking part in any SAR related activity (missions, training, pr events, etc.)?

With which, if any, organization(s) have you been certified (with or without your dog)?

How old is your K9 partner?

How long have you worked with your K9 partner?

Where did you get your K9 partner?

What is the K9's breed?

What is the K9's sex?

Is the K9 intact or altered?

In which discipline(s) have you worked with your K9 partner?

In which discipline(s) are you currently certified with your K9 partner?

How many hours per week (on average) do you work with your K9 partner in SAR related activities (training, missions, or events, obedience, etc.)?

Describe where your K9 resides when they are not working with you in SAR.

Have you made any finds with your K9 partner on an actual mission?

Share any details of the find(s) including the terrain, how long you were working before you made the find, and if the process went similar to how you trained. If not, how was it different?

Appendix B

Perceptions Survey Questions

I feel that my K9 partner is trustworthy.

I feel that my K9 partner is reliable.

I enjoy working with my K9 partner.

If someone questioned my K9 partner’s motives, I would give my K9 partner the benefit of the doubt.

I regularly talk to my K9 partner when on a mission.

I feel comfortable letting my K9 partner work independently of me.

I feel comfortable telling the authorities (police, incident command, etc.) that my K9 partner has located the missing person/source, even when I cannot visually confirm the location.

My K9 partner is always correct (found the subject or source) when they give me their trained final response.

If I was lost, I would want my K9 partner to find me.

My K9 partner is a tool to use to find the missing person.

My K9 partner is a member of the family.

I expect my K9 partner to pull the bulk of the weight on the team.

I expect to pull more weight than my K9 partner on the team.

I trust my K9 partner more than the other human team members.

I rely on my K9 partner more than the other human team members.

I enjoy working with my K9 partner more than the other human team members.

References

- Morey, D.F. Dogs: Domestication and the Development of a Social Bond; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Lebiere, C. The Atomic Components of Thought; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa, M.; Mitsui, S.; En, S.; Ohtani, N.; Ohta, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Kikusui, T. Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human–dog bonds. Science 2015, 348, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, M.L.; Branson, N.; McGreevy, P.D.; Lill, A.; Bennett, P.C. The animal welfare science of working dogs: Current perspectives on recent advances and future directions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 666898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugazza, C.; Miklósi, Á. Deferred imitation and declarative memory in domestic dogs. Anim. Cogn. 2014, 17, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US War Dogs Association. War Dogs Case Studies. Available online: https://www.uswardogs.org/war-dogs-case-studies (accessed on 06/01/2025).

- Soldiers’ Angels. Dogs of Duty: The Story and Legacy of Military Working Dogs. Available online: https://soldiersangels.org/military-working-dogs/ (accessed on 06/01/2025).

- Lazarowski, L.; Dorman, D.C. Explosives detection by military working dogs: Olfactory generalization from components to mixtures. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 151, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, N.; Shimoju, S.; Ishigami, T. Behavioral and stress responses of guide dogs to training and human contact. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 171, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.K.; Olson, J.K.; Gasper, L. Working dog handler perspectives on dog–handler bonding in detection teams. J. Vet. Behav. 2021, 44, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F.; McCullough, L.; Roy, S. Companion animals and health: The balance of benefits and challenges. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Search and Rescue (SAR) Study Participants in the United States and Internationally.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Search and Rescue (SAR) Study Participants in the United States and Internationally.

| Characteristic |

Value/Count |

Figure Representation |

| Total Participants |

183 |

|

| Gender: Male |

56 |

| Gender: Female |

124 |

| Gender: Non-binary |

1 |

| Gender: Not disclosed |

2 |

| Mean Age (years) |

50.52 |

| Age SD |

14.1 |

| Mean SAR Experience (years) |

10.5 |

| SAR Experience SD |

10.89 |

Table 2.

Ethnic Background of SAR Study Participants.

Table 2.

Ethnic Background of SAR Study Participants.

| Ethnicity |

Count |

Figure Representation |

| White |

161 |

|

| Asian |

5 |

| Hispanic/Latino |

4 |

| Bi-racial |

4 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native/Other |

9 |

| Not disclosed |

7 |

Table 3.

Geographic and Environmental Distribution of SAR Study Participants.

Table 3.

Geographic and Environmental Distribution of SAR Study Participants.

| Region/Environment |

Count |

Figure Representation |

| East North Central (U.S.) |

25 |

|

| South Atlantic (U.S.) |

27 |

| West North Central (U.S.) |

22 |

| Outside U.S. |

20 |

| Not disclosed |

36 |

| Wilderness SAR Environment |

167 |

| Rural SAR Environment |

128 |

| Suburban SAR Environment |

108 |

Table 4.

Average Weekly Time Commitment to SAR Activities Among Study Participants.

Table 4.

Average Weekly Time Commitment to SAR Activities Among Study Participants.

| Variable |

Value |

| Mean Hours per Week |

9.89 |

| Standard Deviation |

6.42 |

Table 5.

Distribution of Search and Rescue (SAR) Experience Among Study Participants.

Table 5.

Distribution of Search and Rescue (SAR) Experience Among Study Participants.

| Years in SAR Experience |

Number of Participants |

Figure Representation |

| Less than 1 year |

2 |

|

| 1–5 years |

48 |

| 6–10 years |

41 |

| 11–15 years |

35 |

| 16–20 years |

16 |

| 21–25 years |

16 |

| 26–30 years |

8 |

| 31–35 years |

7 |

| 36–40 years |

4 |

| 41–45 years |

4 |

| 46–50 years |

1 |

| 51+ years |

1 |

| Mean (years) |

10.5 |

| Standard Deviation |

10.89 |

Table 6.

Demographic and Experience Summary of Search and Rescue (SAR) Handlers.

Table 6.

Demographic and Experience Summary of Search and Rescue (SAR) Handlers.

| Inference from the SAR Background Question |

Mean |

SD |

| Respondent’s age |

50.47 years |

14.25 years |

| Average number of years the participants been involved in SAR |

13.32 years |

10.85 years |

| Average number of years the participants worked with a K9 partner |

10.05 years |

8.98 years |

| Average number of K9 partners participants have worked with |

2.78 partners |

1.96 partners |

Table 7.

Perception Survey Descriptive Statistics.

Table 7.

Perception Survey Descriptive Statistics.

| Perception Survey Question |

N |

Mean |

SE |

SD |

| I feel that my K9 partner is trustworthy. |

155 |

4.62 |

0.050 |

0.617 |

| I feel that my K9 partner is reliable. |

153 |

4.33 |

0.054 |

0.723 |

| I enjoy working with my K9 partner. |

155 |

4.90 |

0.041 |

0.507 |

| If someone questions my K9 partner’s motives, I would give my K9 partner the benefit of the doubt. |

153 |

4.16 |

0.074 |

0.919 |

| I regularly talk to my K9 partner when on a mission. |

155 |

3.65 |

0.095 |

1.183 |

| I feel comfortable letting my K9 partner work independently of me. |

155 |

4.45 |

0.069 |

0.854 |

| I feel comfortable telling the authorities (police, incident command, etc.) that my K9 partner has located the missing person/source, even when I cannot visually confirm the location. |

152 |

3.96 |

0.084 |

1.035 |

| My K9 partner is always correct (found the subject or source) when they give me their trained final response. |

155 |

3.92 |

0.072 |

0.894 |

| If I was lost, I would want my K9 partner to find me. |

154 |

4.71 |

0.065 |

0.806 |

| My K9 partner is a tool to use to find the missing person. |

154 |

4.37 |

0.076 |

0.942 |

| My K9 partner is a member of the family. |

155 |

4.85 |

0.046 |

0.571 |

| I expect my K9 partner to pull the bulk of the weight on the team. |

155 |

2.83 |

0.083 |

1.039 |

| I expect to pull more weight than my K9 partner on the team. |

154 |

3.10 |

0.080 |

0.998 |

| I trust my K9 partner more than the other human team members. |

154 |

3.84 |

0.083 |

1.036 |

| I rely on my K9 partner more than the other human team members. |

155 |

3.84 |

0.086 |

1.066 |

| I enjoy working with my K9 partner more than the other human team members. |

155 |

4.00 |

0.074 |

0.919 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).