1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the most threatening danger for public health worldwide, which occur due to frequent use or abuse of clinical antimicrobial drugs [

1]. Therefore, microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses develop a survival mechanism towards known antimicrobial drugs leading to rendering those drugs ineffective [

2]. Antioxidant activity of a product refer to its ability to reduce, inhibit, or prevent oxidation reactions through their ability to terminate free radicals, the presence of free radicals causing oxidation, which is often lead to cell and tissue damage [

3]. Therefore, there is always need to develop new antimicrobial agents with certain antioxidant activity to combat the AMR.

Nanomaterials science is a fast advancing field that represent several components based on the shape and dimensions of these materials, such as nanoparticles, nanowires, nanotubes, and nanosheets [

4]. These nanomaterials are exhibiting very interesting physical, chemical, and biological applications due to their large surface area, resulted from their extremely small particle size within small volume quantity, typically these particles’ size are ranging from 1–100 nm [

5]. Over the past decades, many nanomaterials have been developed for diverse applications, in particular energy storage [

6], catalysis [

7], and pharmaceutical applications [

8]. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have recently been reported as promising antimicrobial agents [

9]. In addition to that, nannoplankton (nannofossils) have been identified in sedimentary successions from the Jurassic period [

10]. Among these nanomaterials, gold containing nanoparticles (AuNPs) found to be one of the most stable nanomaterials with many applications, including drug delivery [

11], photothermal therapy and immunotherapy [

12], as well as cancer therapy [

13,

14,

15]. However, these AuNPs have been reported to exhibit some oxidative damage to cell lines and tissues used in vitro and in vivo, respectively. It has been concluded that liver and kidney functions being the most affected organs by the applications of AuNPs [

16]. It is well documented in the literature that a greener approach such as applying biosynthetic strategies, to access nanoparticles, utilizing a plant extract reduced the level of toxicity present in the nanoparticles [

17,

18], including AuNPs [

19]. This is probably due to the presence of phytochemicals in plant extracts, which are known for their nutrition value and therapeutic properties [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Rocket (

Eruca sativa Mill.) is an edible plant belong to the Brassicaceae family. This species is native from Mediterranean to China through Arabian Peninsula [

25]. Phytochemical extracts from rocket reported several biological activities, including cardiovascular [

26], male reproductive health [

27], and antioxidants [

28]. Polyphenolic compounds, including flavonoids are the principal phytochemicals found in the several tissues of rocket that enhance its antioxidant activities [

29].

In the present study, novel AuNPs were biosynthesized using water extract obtained from the leaves of Eruca sativa plant and their biocompatibility properties were assessed using hemolytic effect on red blood cells, hepatic enzymes levels, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). In kidney functions two biomarker levels were studied, these are urea and creatinine. Furthermore, the antioxidant properties was measured and the antimicrobial activity were investigated on five different microorganism, namely Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae (Gram-positive), Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram-negative), and Candida albicans (fungi).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation of the Eruca Sativa Leaves Extract

The Eruca sativa leaves aqueous extract was prepared using fresh plant leaves and heated to 60 °C to facilitate the release of bioactive compounds, enhance extraction efficiency, and increase solubility. Heating beyond 70–80 °C may lead to the degradation of these active constituents. The resulting extract exhibited a green color, primarily due to the presence of chlorophyll pigments naturally found in the plant leaves. It is recommended to store the plant extract at 4 °C and utilized within 24 h. We noticed that, extended storage beyond this period resulted in microbial contamination and subsequent spoilage.

2.2. Preparation of the Gold Stock Solution and Its Dilution

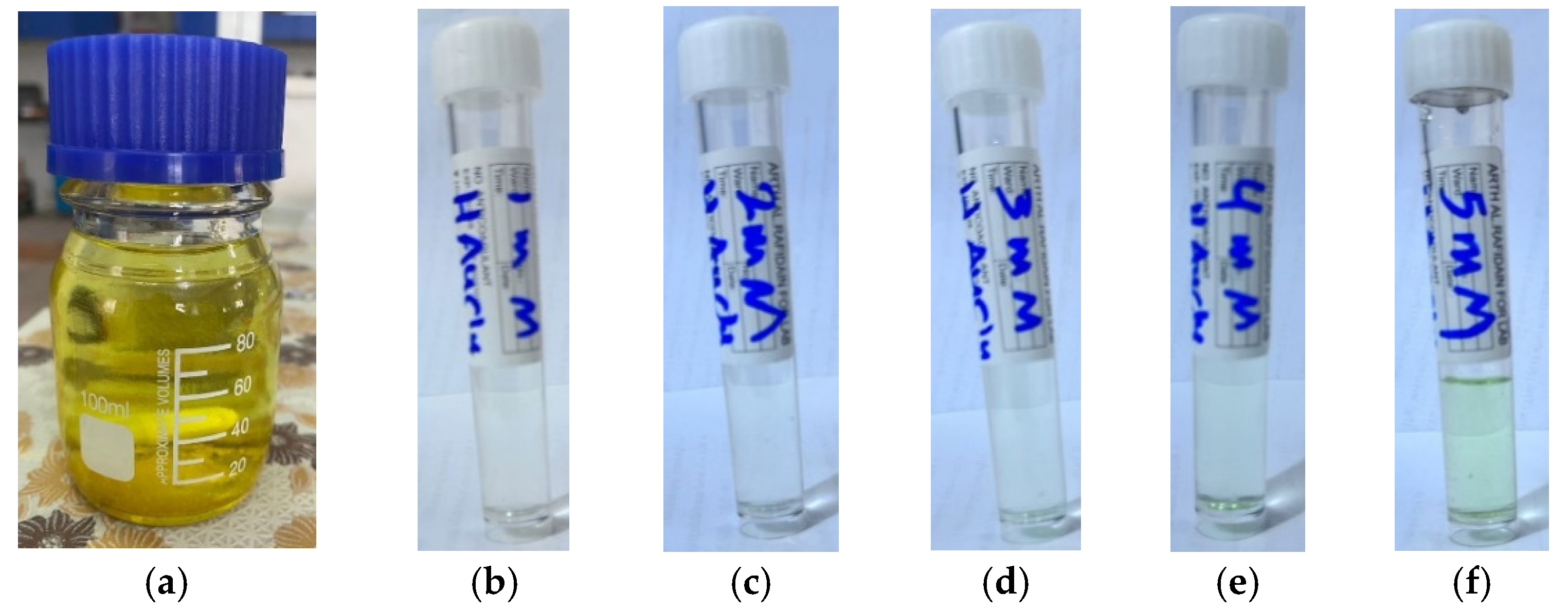

Tetrachloroauric(III) acid trihydrate (HAuCl

4·3H

2O) is yellow crystalline and fully dissolved in water producing a yellow solution (

Figure 1a). The solution exhibited clear homogeneity with no visible precipitation or impurities, indicating complete dissolution of the gold salt in the aqueous medium. This step is essential to ensure the success of the subsequent reduction reaction and the uniform and stable formation of gold nanoparticles. The prepared stock solution was diluted to prepare five different concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mM),

Figure 1b–e.

2.3. Green Synthesis of the AuNPs Using Eruca Sativa Leaves Extract

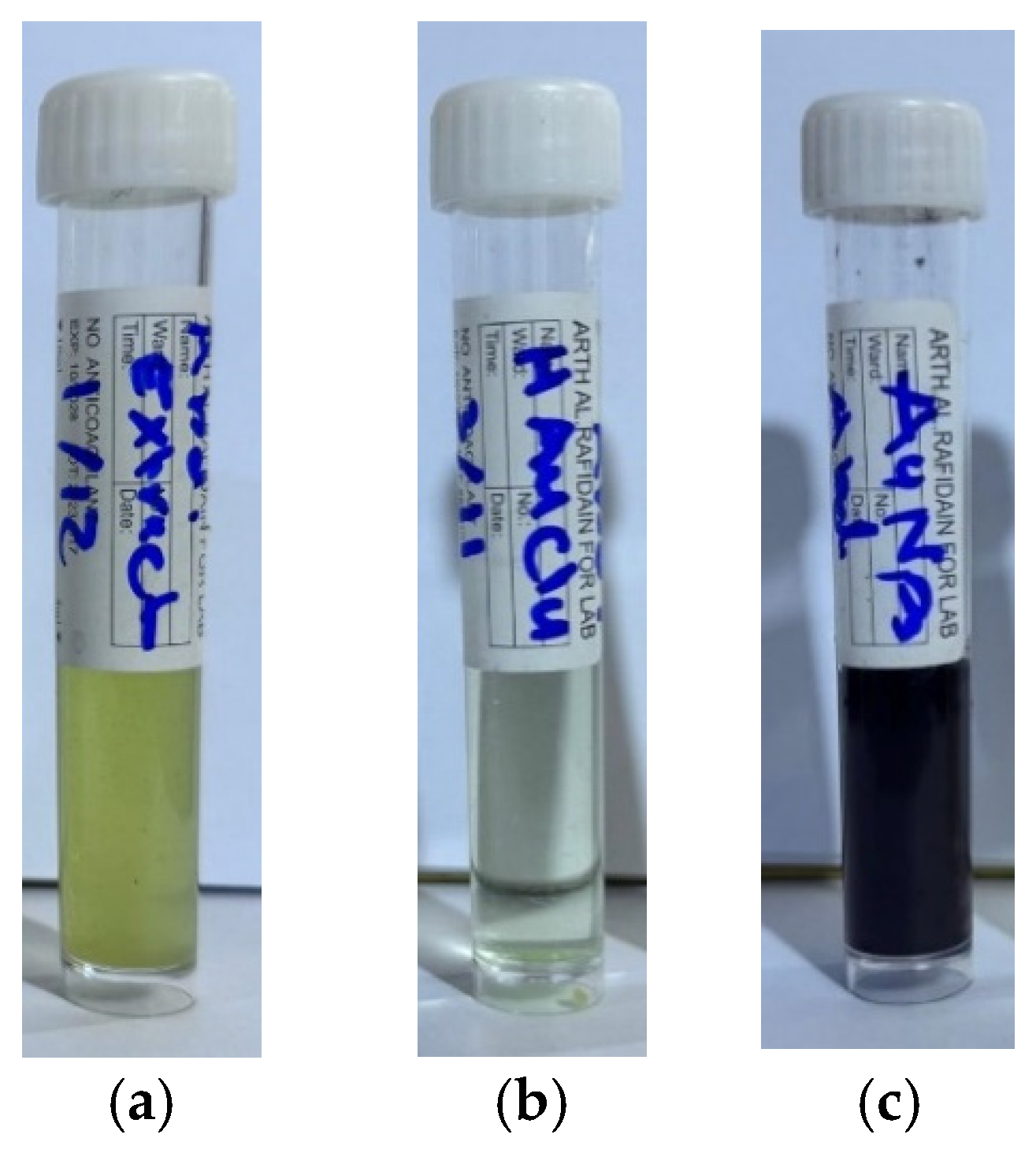

In the synthesis of gold nanoparticles, the plant extract (

Figure 2a) was added gradually to the gold salt solution (

Figure 2b) to ensure controlled nucleation and uniform particle formation. The reaction is typically carried out under elevated temperatures, which play important role in accelerating the reduction process, promoting nanoparticle formation, and improving size distribution and stability of the resulting gold nanoparticles. The color change, typically from pale yellow to ruby red, serves as a visual indicator of successful nanoparticle synthesis due to the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) phenomenon associated with gold nanoparticles [

30], see

Figure 2c.

Using plant extract, such as the leaves of

Eruca sativa plant, can improve the AuNPs with respect several parameters, including the reduction of Au(III) ions, stabilization of the synthesized nanostructures, and to add some biological effects of the phytochemicals present in the plant [

31]. The concentration of the extract influences the size, shape, and regularity of the produced AuNPs. The synthesis of AuNPs may be substantially altered by adjusting the reducing properties of various plant species, which contain varying levels of active reducing agents. However, when the quantities of plant extracts increase, AuNPs often decrease in size [

32]. The impact of phytochemicals that form, grow, and stabilize the crystals, along with their decreased production rate, accounts for the reduction in size. This has prompted scientists to develop synthetic strategies that provide enhanced control over size and form [

33].

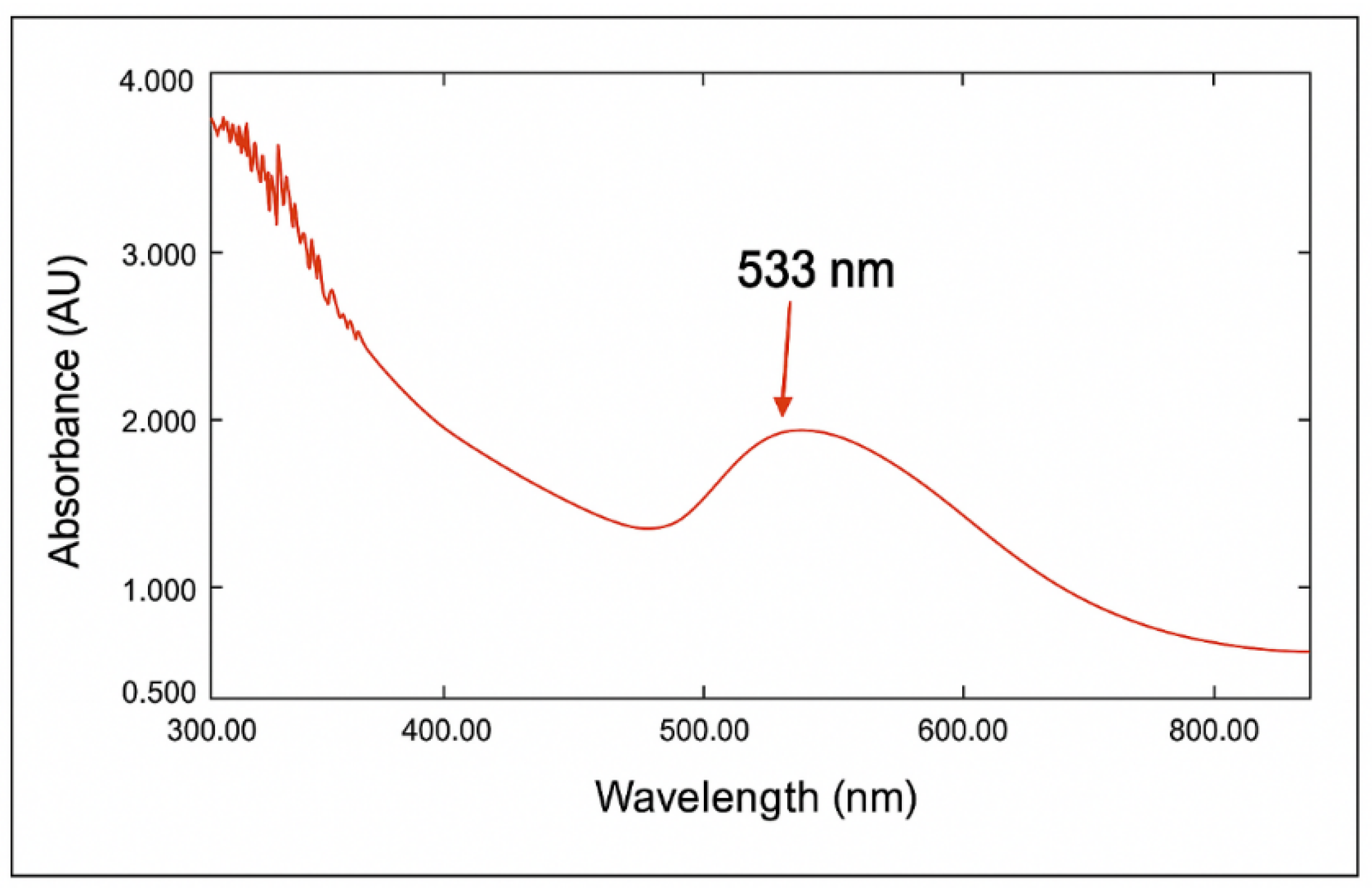

2.4. UV-Vis Spectroscopy Study

The characteristics of AuNPs were determined by UV-Vis spectroscopy. The data revealed the absence of a distinct band for the

Eruca sativa extract; however, upon the addition of gold solution (HAuCl

4), a broad peak emerged within the range of 530–540 nm [

34]. The λ

max at 533 nm indicate the development of mono-dispersed spherical AuNPs (

Figure 3) as previously reported [

35], as it is confirmed by other characterizations. This reaction transpires about 10 minutes, accompanied by a noticeable color shift. The color shift is a recognized occurrence in nanoparticle synthesis, especially concerning AuNPs, where the color alteration serves as a visual indicator of nanoparticle creation [

32].

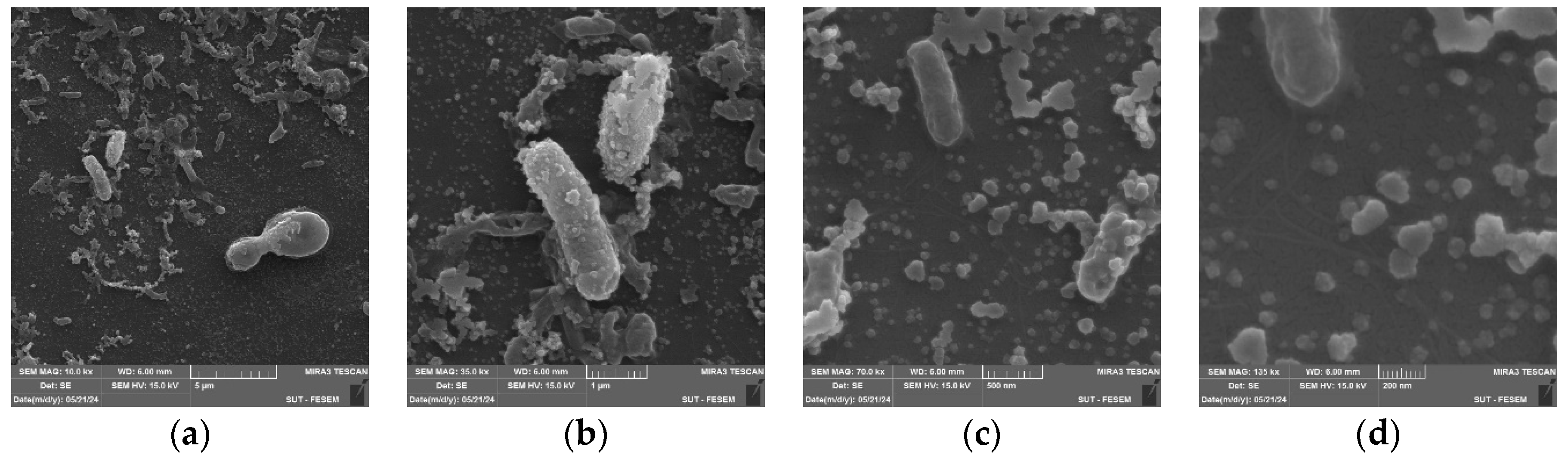

2.5. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) Analysis

The morphology and dimensions of the biosynthesized AuNPs are analyzed using FESEM, which shows the particle size distribution histogram of AuNPs. Pictures in

Figure 4 are taken at different SEM magnification: 10.0 kx (

a), 35.0 kx (

b), 70.0 kx (

c), and 135.0 kx (

d), demonstrates that the generated AuNPs display spherical forms. The mean particle sizes were analyzed using ImageJ program and were found to be around 37–70 nm.

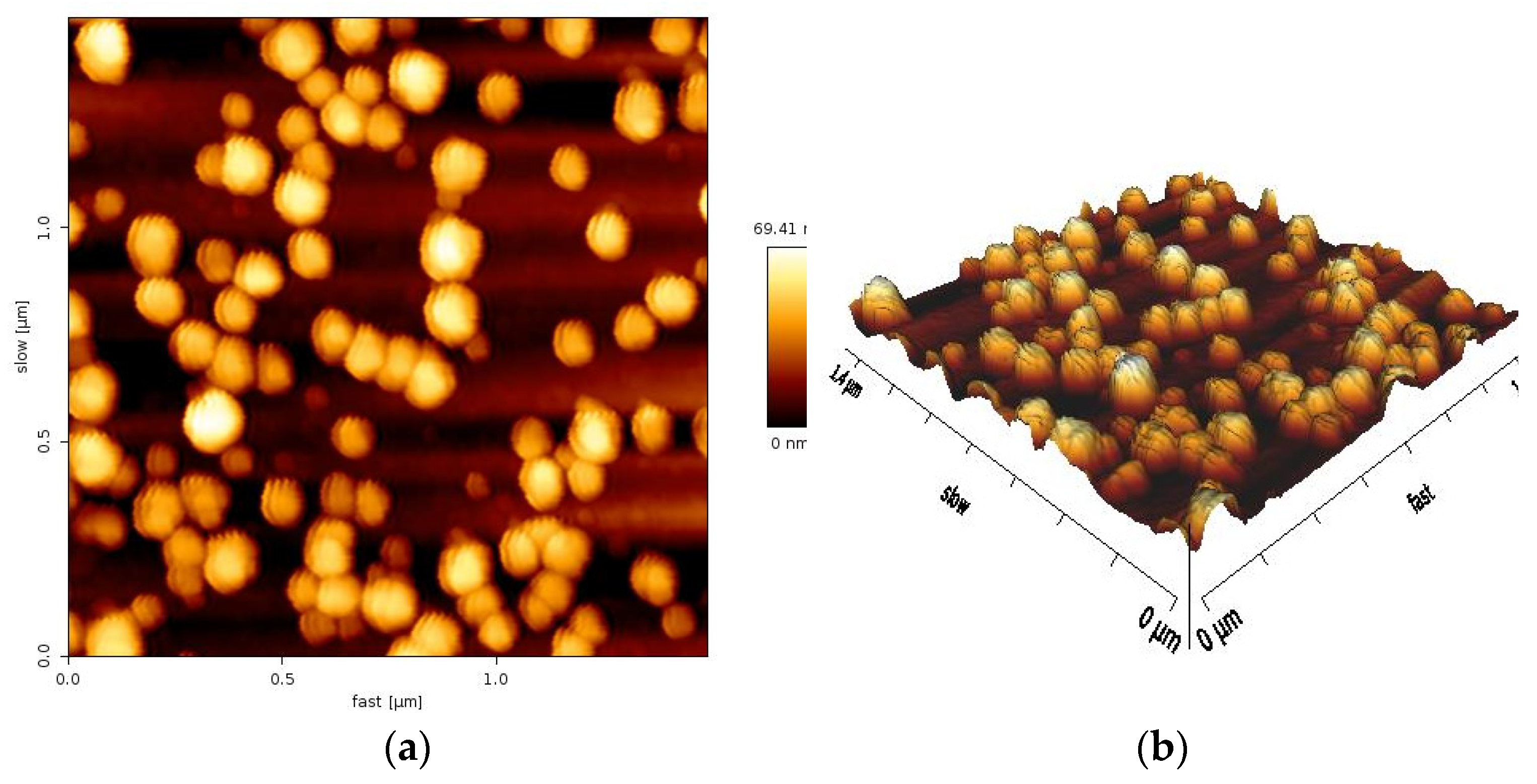

2.6. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Analysis

The biosynthesized AuNPs were studied by AFM analysis to determine their size and shape. The origin of the surface morphology found to be irregularly shaped particle sizes and the wide size range of AuNPs prepared using

Eruca sativa plant extract. The particle size of the AuNPs ranged from 20 to 90 nm, with an average size of 69.41 nm.

Figure 5 illustrates the 2D and 3D AFM images together with the associated size distribution of AuNPs. The AFM sample taken one month following the synthesis of AuNPs exhibited no aggregation or agglomeration, which indicate that these AuNPs exhibit a very good stability. The obtained particle size is in consistent with the published results from earlier investigations [

36]. Other researchers reported the particle size of AuNPs with different sizes [

37]. The discrepancies in particle sizes of the biosynthesized AuNPs probably due to the utilization of different synthesis approach and/or using variations in plant species.

2.7. Hemolysis Assay

The hemolytic activity of the biosynthesized AuNPs was measured and compared with positive control (PC), using deionized water, represent full hemolysis activity (0.991 AU), while the negative control (NC), using saline, showed absorbance intensity 0.087 AU that correlate to no hemolysis. The measurement were conducted at fixed wavelength (415 nm), which is the hemoglobin absorbance. The increase of the absorbance intensity represent the increase in hemoglobin release, which indicate elevated level of hemolysis [

38]. The study of hemolytic activity of the AuNPs and the two controls are outlined in

Table 1. The AuNPs showed intensity (0.095 AU), which is very close to the negative control, this indicates the biosynthesized AuNPs using Eruca sativa plant leaves extract, does not induce or shows a very little red blood cells lysis.

The hemolysis coefficient (HC) was calculated using the equation mentioned in the experimental part and found to be <1%, which indicates that the biosynthesized AuNPs exhibit minimal hemolytic activity, and thus, they are not significantly toxic to red blood cells under the conditions tested. This hemolytic result suggests that AuNPs are biocompatible and have very low toxicity toward red blood cells and hence can be utilized in medical applications, including drug delivery or diagnosis, without causing significant damage to red blood cells.

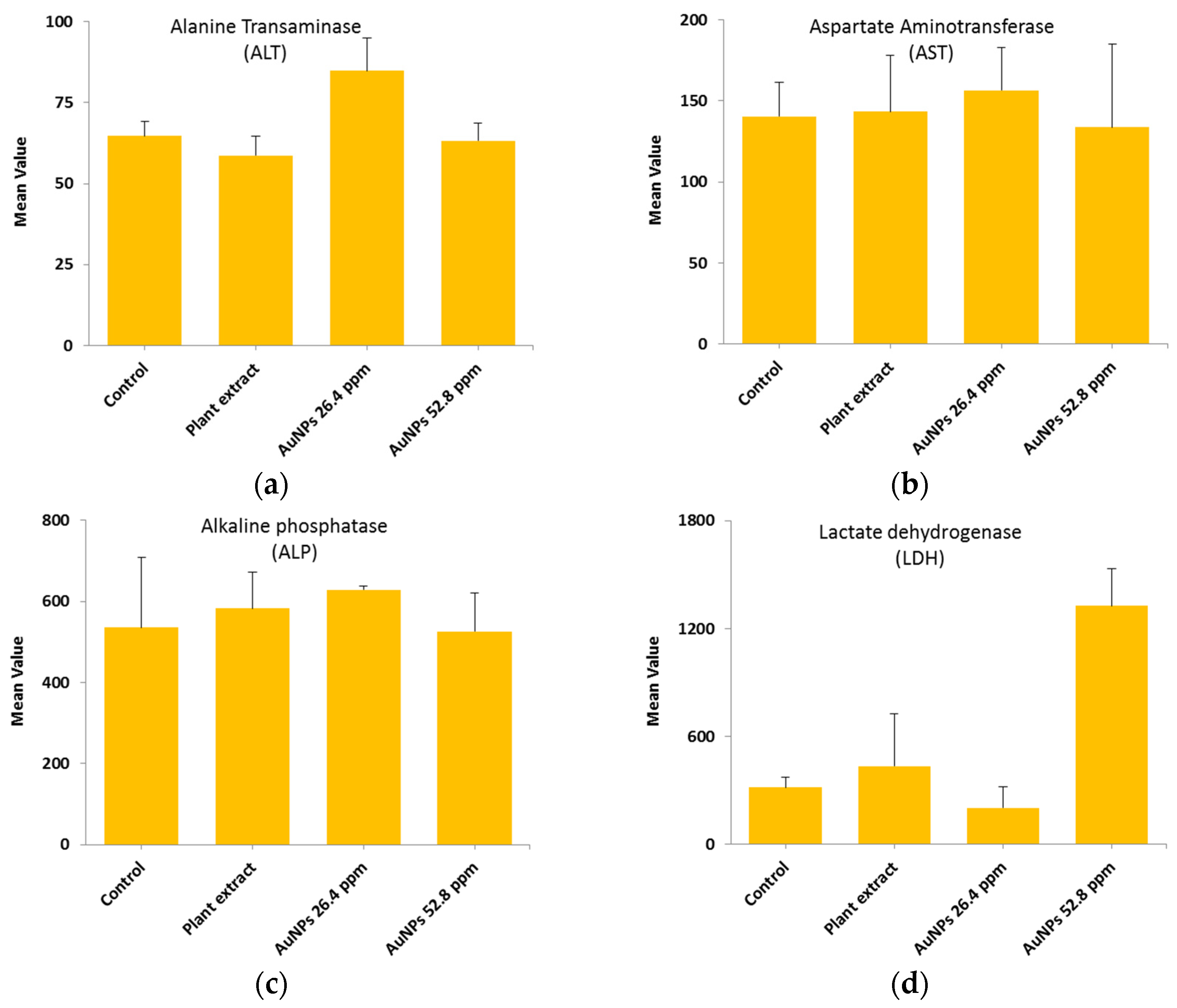

2.8. Hemolysis Assay

2.8.1. Hepatic Function

The results of hepatic function level for the four groups (Control, Extract, AuNPs 26.4 µg/mL and AuNPs 52.8 µg/mL) has been measured using the mean ± SD and are listed in

Table 2 and

Figure 6.

The results suggest that there is no significant difference among ALT, AST, and ALP, at all tested materials, including control (deionized water), plant extract, AuNPs (26.4 mM), and AuNPs (52.8 mM). On the other hand, the LDH enzyme level shows significant difference with respect the high concentration of using AuNPs (52.8 mM), while at lower concentration there was no toxicity observed. This indicate that the low concentration of gold nanoparticles (26.4 µg/mL) is preferable with regards the LDH enzyme.

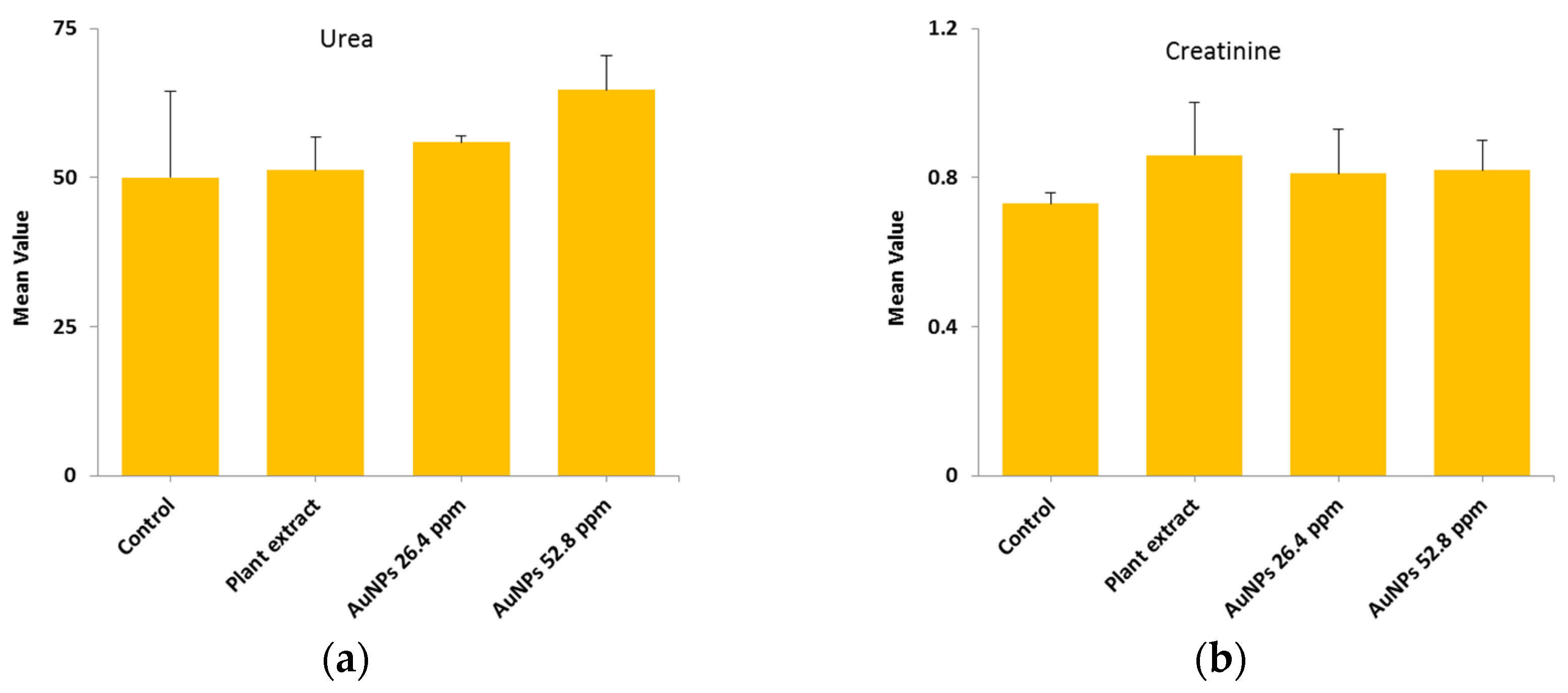

2.8.2. Hepatic Function

In order to study the renal function, two parameters (urea and creatinine) were selected based on their importance with regards the efficacy of renal filtration and overall renal health. All groups, including control, plant extract, AuNPs (26.4 µg/mL), and AuNPs (52.8 µg/mL) were measured and the mean ± SD are illustrated in

Table 3 and

Figure 7.

The results showed no significant difference (p>0.05) among tested groups, this indicate there is no change in the normal urea and creatinine levels and therefore there is no impact on liver cells.

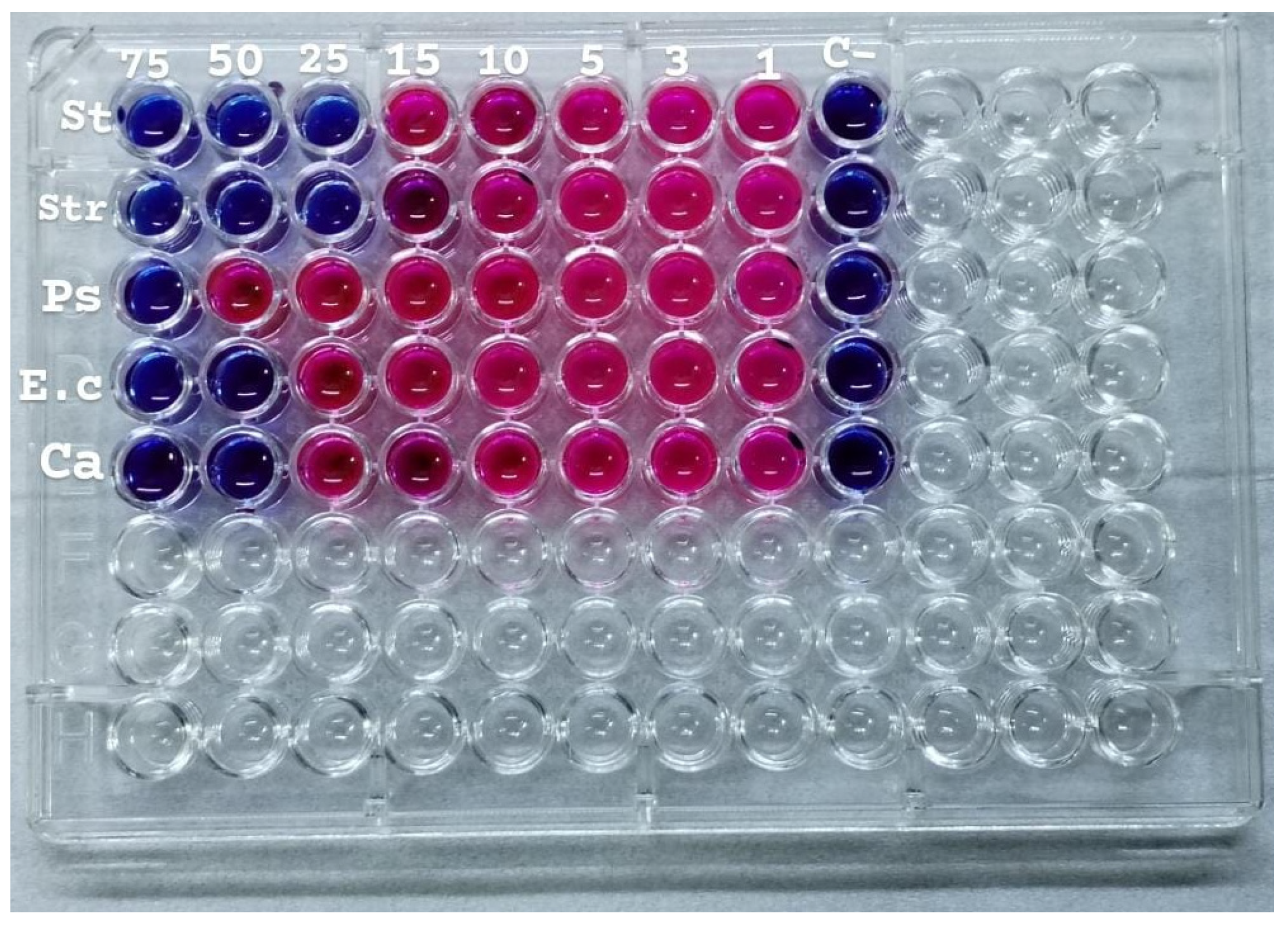

2.9. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The AuNPs was evaluated in vitro against five microbial isolates:

S. aureus and

S. pneumoniae (Gram-positive),

P. aeruginosa and

E. coli (Gram-negative), and

C. albicans (fungi). The MIC was determined by solution color change on the plate: Pink/Red wells means no microbial growth inhibition observed, while the blue/purple color wells represent lack of microbial growth, which means inhibition of microorganism growth. The MIC results as follows;

S. aureus and

S. pneumoniae (13.2 µg/mL),

P. aeruginosa (39.6 µg/mL),

E. coli and

C. albicans (26.4 µg/mL), see

Figure 8.

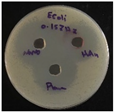

2.10. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of the biosynthesized AuNPs, plant extract, and gold salt (HAuCl

4) using the well diffusion method were conducted on five microorganisms, two Gram-positive (

S. aureus,

S. pneumonia), two Gram-negative (

P. aeruginosa,

E. coli), and one fungi (

C. albicans). The minimum inhibitory concentration MIC results obtained in section 3.9 were utilized to measure the antimicrobial activity, see

Table 4.

The values presented in

Table 4 indicated zones of inhibition (measured in millimeter), demonstrated the efficacy of each drug in inhibiting microbial growth. Elevated readings indicated enhanced efficacy.

The zones of inhibition ranged from 35 mm to 40 mm, with selectivity against S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and C. albicans (40 mm for each). The plant extract showed a moderate activity with inhibition zones ranging from 34 to 37 mm. HAuCl4 (gold salt) showed the least effective of the tested products with zones of inhibition in the range 28–30 mm. The results revealed that AuNPs was the most effective antibacterial agent, likely due to its high reactivity and ability to penetrate microbial cells due to its extremely small size (70 nm).

With regards the mechanism of action, recent studies suggest that gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) exhibit antibacterial activity through multiple integrated mechanisms. Including, AuNPs can interact with bacterial cell walls, disrupting membrane integrity and increasing permeability, leading to leakage of cellular contents and eventual cell death. This mechanism is comparable to the inhibitory effect observed with silver nanoparticles [

40]. In another study, AuNPs are capable of inducing the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause oxidative damage to cellular proteins, lipids, and DNA. This oxidative stress leads to severe impairment of bacterial cell function [

41]. Moreover, AuNPs may bind to intracellular proteins and nucleic acids, interfering with transcription and translation processes, thereby inhibiting bacterial replication. This mechanism is supported by findings from studies on organo-ligand-based nanomaterials with confirmed antibacterial efficacy [

42]. These findings suggest that AuNPs probably act through a multifaceted approach, targeting bacterial cells through physical disruption and biochemical interference, leading to effective antimicrobial action.

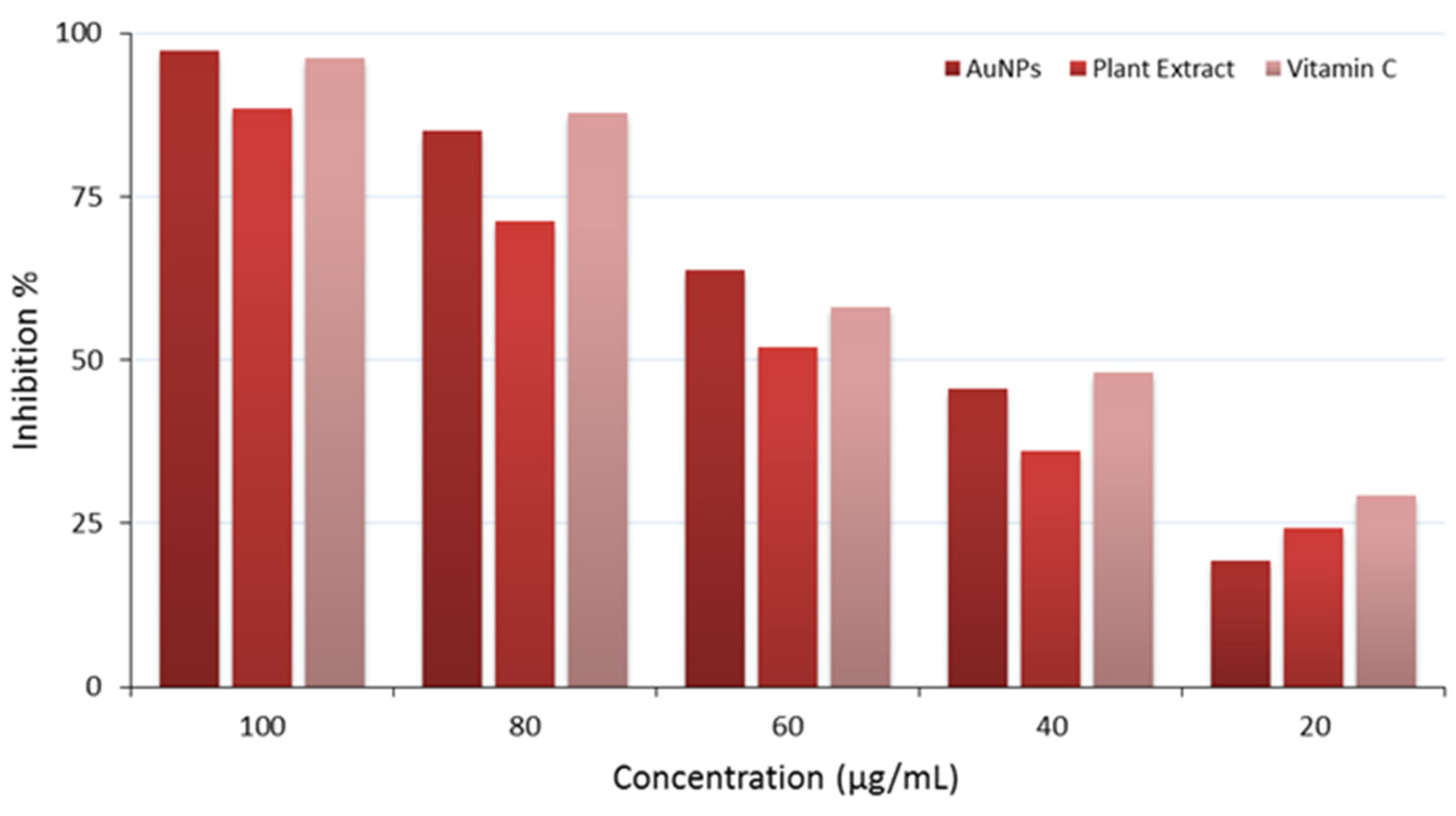

2.11. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

The antioxidant activity has been conducted on the biosynthesized AuNPs, the plant extract, and vitamin C, results are illustrated in

Table 5 and

Figure 9.

The findings assess the antioxidant activity of three distinct substances AuNPs, Plant Extract, and Vitamin C, evaluated at varied doses (100, 80, 60, 40, and 20 µg/mL). The inhibition percentages were quantified to assess their efficacy in neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS), significant contributors to oxidative stress and cellular damage. All three tested materials (AuNPs, plant extract, and vitamin C) showed a concentration dependent manner. AuNPs showed almost full percent inhibition (97.2%) at 100 µg/mL. it shows slightly stronger antioxidant activity compared to the standard (vitamin C). Interestingly, the plant extract showed notable antioxidant activity, demonstrating an inhibition percentage of around 88.5% at 100 µg/mL, this antioxidant activity probably due to the presence of phytochemicals in the plant extract that involve in this antioxidant activity.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

All chemicals were used as purchased from respective company: Tetrachloroauric(III) acid trihydrate from Merck KGaA, Germany; 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), vitamin C, copper sulfate, ferric chloride, methanol, potassium mercuric iodide, potassium iodide, resazurin dye from Sigma Aldrich, Germany. All stock solutions and further dilutions were prepared using deionized water. Healthy Wistar rats (male) were obtained from the Biotechnology Research Center, Al-Nahrain University, Baghdad, Iraq. Atomic Force Microscope (AFM), Model AA3000, Angstrom Advance Inc, USA; Centrifuge (Digital), Rotina, Germany; FE-SEM, FESEM MIRA3 TESCAN instrument, UK; FT-IR-shimadzu-8400S spectrophotometer, Shimadzu-8400S, Japan.

3.2. Preparation of the Eruca Sativa Mill. Leaves Extract

The rocket (Eruca sativa Mill.) plant was freshly collected near the city of Baqubah, Diyala-Iraq. They were identified by a plant taxonomist, Prof. Dr. Khazal Dabaa Wadi, Department of Biology, College of Science, Diyala University, Iraq. The leaves were taken from the plant, washed three times with tab water and finally with distilled water to remove any mud or dirt. The leaves were chopped into small pieces around 1 cm2 using sterilized scissors. The small pieces of rocket (20 g) were mixed with distilled water (100 mL) and heated using hot plate at 60 °C for one hour. The mixture was then let to cool down to room temperature. The solution was then filtered through Whatman filter paper No. 1. The filtrate was collected and placed in a sealed glass bottle and stored at 4 °C until it is used for the preparation of AuNPs.

3.3. Preparation of the Gold Stock Solution and Its Dilution

The gold solution was prepared from dissolving tetrachloroauric(III) acid trihydrate (1 g) in deionized water (100 mL) resulting in 25 mM concentration (

Figure 1,

a). From this stock solution, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mM solutions were prepared,

Figure 1,

b–f, respectively, and utilized for the green synthesis of AuNPs.

3.4. Green Synthesis of AuNPs

Eruca sativa plant extract (10 mL) was gradually added to the gold salt solutions at variant concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mM) over 15 min at 60 °C. The 5 mM concentration gave the most stable and reproducible AuNPs (

Figure 2). The formation of AuNPs with the

Eruca sativa extract was followed by the change in the reaction mixture color from light yellow to purple-violet, which serve as a preliminary indicator for the synthesis of AuNPs [

43].

3.5. Characterization of the Biosynthesized Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)

3.5.1. Ultraviolet–Visible (UV–Vis) Spectroscopy

The UV-Vis spectrum was obtained using a spectrophotometer model (PG-Instruments Limited, T80, Germany). At regular intervals, spectroscopic assays assessed the reduction of AuNPs. The wavelength range is 300 to 800 nanometers. Three milliliters of the sample were put into UV cuvette and subsequently assessed at ambient temperature. UV-Vis spectroscopy is useful tool for the characterization of nanoparticles [

44].

3.5.2. The Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) Analysis

The morphology of the prepared AuNPs was examined using FE-SEM instrument. The observed chemical composition of the synthesized nanostructures was determined using energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX). This analysis provide a high resolution pictures to the surface of the nanoparticles, which make this technique usefully for the characterization of nanoparticle size distribution [

45].

3.5.3. The Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Analysis

The samples were analyzed using an AFM (Nanonics imaging MN1000) to determine the precise particle size and quantify the nanosize effect. The method of evaporating the droplet was used to create AFM suspensions samples of nanoparticle fluid. The drop was placed on a glass covering slide (2 × 6 cm

2) and then drained before imaging, either by leaving it overnight in a dust-free environment or by using an oven/heater at a low temperature to expedite the drying process [

46].

3.6. Ethical Approval

This research has been considered by the scientific and ethical committee Ref.: BCSMU/0524/0003C in Date: May 01, 2024, Department of Chemistry, College of Science, Mustansiriyah University. It meets the Three Rs. requirements (replacement, reduction, and refinement).

3.7. Hemolytic Activity

This In rat whole blood, the hemolytic ability of AuNPs was investigated as previouls described [

47]. In brief, 0.5 mL of AuNPs sample incubated with a corresponding volume of blood, obtained from rats, for 24 h at 37 °C in a biological thermostat. Blank samples were prepared; deionized water served as the positive controls (PC) and saline as the negative controls (NC). Following incubation, the samples were vortexed for 5 minutes. The mixture were analyzed using spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 415 nm, which is similar to the absorption band of oxyhemoglobin, hemolytic activity was assessed using the hemolysis coefficient (HC). The following formula was used to compute hemolytic activity:

O represents the optical density of the sample, NC denotes the negative control (0% hemolysis of the blank sample), and PC signifies the positive control (52.8 µg/mL hemolysis of the blank sample) [

48].

3.8. Animals and Experimental Design

The experimental animals, male Wistar rat (6–8 weeks old, weighing 200–250 g), were housed in the animal facility of the Biotechnology Research Center, Al-Nahrain University, Baghdad, Iraq, and was handled by a specialized team at the center. Sixteen rats were randomly distributed into four groups of four rats each. Group 1 received deionized water and served as the control, group 2 received the extract at 50 mg/kg body weight orally once, group 3 was administrated the concentrated dose of AuNPs (52.8 µg/mL), and group 4 received diluted AuNPs (26.4 µg/mL). All test animals received oral gastric gavage once a day with varying materials (deionized water, plant extract, and AuNPs) and each rat was continuously monitored every day for 28 days post-administration [

49].

3.9. Hepatic and Renal Function Analysis

3.9.1. Blood Samples Collection

Upon completion of the treatments, the rats were anesthetized with diethyl ether, and blood samples were procured by heart puncture into gel/clot activator tubes for 30 min to expedite clotting, followed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes to isolate serum. Blood specimens for hematological analysis were obtained in an EDTA tube [

50].

3.9.2. Serum Analysis of Hepatic and Renal Function

Cobas c111 Automated Analyzer (Roche, Germany) with the suitable kits were used to assessed the liver and kidney functions. The subsequent parameters liver functions were assessed using the measurement of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The renal functions were assessed by the measurement of urea and creatinine.

3.10. Statistical Analysis

All markers represented like mean ± stander deviation (SD). The differences in levels of these markers among study groups were statistically measured by F-test (ANOVA). Duncan test was done to measure differences among mean levels. p≤0.05 was depended for differences calculation. Present data were programmed by SPSS v. 20.0 and Microsoft Office Excel 2013 statistical software.

3.11. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

Double serial dilutions (0.52–39.6 μg/mL) of AuNPs were prepared from a stock solution (10 mg·mL

−1) in a microtiter plate utilizing Mueller-Hinton broth as the diluent. All wells, excluding the negative control wells, were inoculated with 20 μL of a bacterial suspension according to McFarland standard no. 0.5 (1.5×108 CFU/mL). Microtiter plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 to 20 h. After incubation, 20 µL of resazurin dye was added to each well and incubated for extra 2 h to monitor any color changes. The sub-minimum inhibitory concentration was visually assessed in broth micro dilutions as the minimal levels at which the color changed from blue to pink in the resazurin broth assay [

51].

3.12. Antimicrobial Activity

The agar well diffusion method was utilized to evaluate the antibacterial activity of AuNPs at the MIC concentration obtained above. The antibacterial activity of

Eruca sativa extract, AuNPs, and HAuCl

4 solution against

S. aureus and

S. pneumonia (Gram-positive),

E. coli and

P. Aeruginosa (Gram-negative), and

C. albicans (fungus). Each bacterial isolate was cultivated in nutrient broth and incubated at 37 ºC for 18 to 24 h. Following the incubation period, 0.1 mL of each bacterial suspension was spread on the surface of nutrient agar and incubated at 37 ºC for 24 hours. A single colony was placed into a test tube containing 5 mL of normal saline to produce a bacterial suspension of moderate turbidity comparable to the standard turbidity solution, approximately equivalent to 1.5 × 10

8 CFU/mL. A sterile cotton swab was utilized to carefully transfer a portion of the bacterial suspension, which was then uniformly spread on Mueller-Hinton agar medium and incubated for 10 minutes. Wells with the diameter of five-millimeter were created in the preceding agar layer, with three wells per plate designated for AuNPs, extract, and HAuCl

4 solution. Agar dishes were removed, and 50 µL of AuNPs, extract, and HAuCl

4 solution were added into each well utilizing a micropipette. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h, after which the diameters of the inhibition zones were measured in millimeters [

52].

3.12. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

The in vitro antioxidant activity of

Eruca sativa leaves extract, AuNPs, and vitamin C were assessed using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) free radical scavenging assay [

53]. In brief, 2 mL of different concentrations (10, 20, 40, 80, and 100 μg/mL) were mixed with 2 mL of DPPH (mg/mL) solution in methanol. Tubes were incubated in the dark for up to 30 min. Subsequently, samples absorbance were measured at λ = 517 nm. DPPH solution without AuNPs was used as a control. Vitamin C and methanol solution were used as standard and blank, respectively. The DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined using the following equation:

where, A0 = absorbance of the control; A1 = absorbance of the sample.

4. Conclusions

Novel gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were synthesized by green synthetic approach using

Eruca sativa plant leaves aqueous extract and characterized using UV-Vis, FESEM, and AFM analysis. The evaluation of hemolytic activity demonstrated that AuNPs exhibit favorable biocompatibility, with hemolysis rates less than 1%, suggesting no harmful to the red blood cells and implying their prospective safety for biomedical applications. At high AuNPs concentration (52.8 µg/mL), there was elevation level in liver enzymes LDH, while at the lower concentration (26.4 µg/mL) induced only mild alterations in LDH. All other tested liver and kidney biomarkers, including ALT, ASP, ALP, urea, and creatinine showed no significant impact of AuNPs and therefore, might be useful in biomedical applications. The extract of

Eruca sativa showed protective benefits against known AuNPs induced toxicity [

16], presumably owing to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. This protection probably reduced the damage to both hepatic and renal cells. Furthermore, the newly developed AuNPs was biologically evaluated against five different microorganisms, namely, two Gram-positive (

S. aureus,

S. pneumonia), two Gram-negative (

P. aeruginosa,

E. coli), and one fungi (

C. albicans). The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were measured, revealing potential activity and selectivity of AuNPs towards Gram-positive bacteria. The antioxidant profile of AuNPs, plant aqueous extract where measured using the DPPH assay and compared with vitamin C, the standard control. AuNPs found superior to vitamin C indicating its ability to act as antioxidant that might be useful for combating cell damages caused by oxidizing agents, such as free radicals. In conclusion, the green synthesized AuNPs using

Eruca sativa aqueous leaves extract showed strong biocompatibility in vivo, and the new product comprises antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. Therefore, this study suggest a new green synthesized AuNPs with potential application in very low doses (ppm scale) against microorganisms and might be useful as alternative for clinical drugs to combat the antimicrobial resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.N.J., M.T.M., and Y.B.; methodology, A.M.N.J., M.T.M., and Y.B.; software, A.M.H., Y.B.; validation, A.M.H., and A.M.N.J.; formal analysis, A.M.H., A.M.N.J., and Y.B.; investigation, A.M.H.; resources, A.M.N.J.; data curation, A.M.H. and Y.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.H., A.M.N.J., and M.T.M.; writing—review and editing, Y.B.; supervision, A.M.N.J.; funding acquisition, Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Arab-German Young Academy of Sciences and Humanities (AGYA) grant (01DL20003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the scientific and ethical committee Department of Chemistry, College of Science, Mustansiriyah University (BCSMU/0524/0003C, 01/05/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are made available in the submitted manuscript.

Acknowledgments

A.M.H., A.M.N.J., and M.T.M. would like to thank Mustansiriyah University (

www.uomustansiriyah.edu.iq) Baghdad-Iraq for its support in the present work. Y.B. would like to acknowledge Sultan Qaboos University (

https://www.squ.edu.om/) for its support in the present work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A0 |

Absorbance of the control |

| A1 |

Absorbance of the sample |

| AFM |

Atomic Force Microscopy |

| ALP |

Alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT |

Alanine transaminase |

| AMR |

Antimicrobial resistance |

| AST |

Aspartate aminotransferase |

| AU |

Arbitrary unit |

| AuNPs |

gold nanoparticles |

| dl |

Deciliter |

| DPPH |

2,2-DiPhenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl |

| FESEM |

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HC |

Hemolytic Activity |

| IU |

International Unit |

| kx |

Thousands of times magnification |

| LDH |

Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MIC |

Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| NC |

Negative control |

| NC |

Negative control |

| O |

Optical density |

| PC |

Positive control |

| PC |

Positive control |

|

p-value |

Probability value |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SPR |

Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| U/L |

Unit/Liter |

| UV-Vis |

Ultraviolet–visible |

References

- Ho, C.S.; Wong, C.T.H.; Aung, T.T.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Mehta, J.S.; Rauz, S.; McNally, A.; Kintses, B.; Peacock, S.J.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Ting, D.S.J. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Concise Update. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 100947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdi, I.S.; Abdula, A.M.; Jassim, A.M.N.; Baqi, Y. Design, Synthesis, Antimicrobial Properties, and Molecular Docking of Novel Furan-Derived Chalcones and Their 3,5-Diaryl-Δ2-pyrazoline Derivatives. Antibiotics 2023, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.J.; Won, Y.S.; Kim, E.K.; Park, S.I.; Lee, S.J. Free Radicals and Their Impact on Health and Antioxidant Defenses: A Review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle Classification, Physicochemical Properties, Characterization, and Applications: A Comprehensive Review for Biologists. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushnood, M. Nanomaterials: Surface Area to Volume Ratio. J. Mater. Sci. Nanomater. 2024, 8, 159. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantseva, E.; Bonaccorso, F.; Feng, X.; Cui, Y.; Gogotsi, Y. Energy Storage: The Future Enabled by Nanomaterials. Science 2019, 366, eaan8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Yang, E.; Kim, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, W. Biomimetic Chiral Nanomaterials with Selective Catalysis Activity. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2306979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illath, K.; Kar, S.; Gupta, P.; Shinde, A.; Wankhar, S.; Tseng, F.G.; Lim, K.T.; Nagai, M.; Santra, T.S. Microfluidic Nanomaterials: From Synthesis to Biomedical Applications. Biomaterials 2022, 280, 121247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadelkareem, A.M.; Al-Shammari, E.; Elkhalifa, A.O.; Adnan, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Patel, M.; Khan, M.I.; Mehmood, K.; Ashfaq, F.; Badraoui, R.; Ashraf, S.A. Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles from Eruca sativa Miller Leaf Extract Exhibits Antibacterial, Antioxidant, Anti-Quorum-Sensing, Antibiofilm, and Anti-Metastatic Activities. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.; McCann, T.; Al-Juboury, A.I.; Ustinova, M.A.; Sharezwri, A.O. Early Jurassic–Early Cretaceous Calcareous Nannofossil Biostratigraphy and Geochemistry, Northeastern Iraqi Kurdistan: Implications for Paleoclimate and Paleoecological Conditions. Geosciences 2022, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgeous, J.; AlSawaftah, N.; Abuwatfa, W.H.; Husseini, G.A. Review of Gold Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Properties, Shapes, Cellular Uptake, Targeting, Release Mechanisms and Applications in Drug Delivery and Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Crawford, B.M.; Vo-Dinh, T. Gold nanoparticles-mediated photothermal therapy and immunotherapy. Immunotherapy 2018, 10, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloise, N.; Strada, S.; Dacarro, G.; Visai, L. Gold Nanoparticles Contact with Cancer Cell: A Brief Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkmen Koc, S.N.; Rezaei Benam, S.; Aral, I.P.; Shahbazi, R.; Ulubayram, K. Gold Nanoparticles-Mediated Photothermal and Photodynamic Therapies for Cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 655, 124057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesharwani, P.; Ma, R.; Sang, L.; Fatima, M.; Sheikh, A.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Gupta, N.; Chen, Z.S.; Zhou, Y. Gold Nanoparticles and Gold Nanorods in the Landscape of Cancer Therapy. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.; Cao, C.; Cui, D. Toxicity of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs): A Review. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 26, 100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaabedin, A.A.Z.; Hamza, B.H.; Abdual-Majeed, A.M.A.-M.; Bamsaoud, S.F. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles to Study Its Effect on the Skin Using IR Thermography. Al-Mustansiriyah J. Sci. 2023, 34, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazim, K.A.; Moghaddam, H.M. Green Synthesis of Nickel Nanoparticles Using Lawsonia inermis Extract and Evaluation of Their Effectiveness against Staphylococcus aureus. Al-Mustansiriyah J. Sci. 2025, 36, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailova, E.O. Gold Nanoparticles: Biosynthesis and Potential of Biomedical Application. J. Funct. Biomater. 2021, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Al-Habib, A.A.S. Evaluation of the Activity of Petroselinum crispum Aqueous Extract as a Promoter for Rooting of Stem Cuttings of Some Plants. Al-Mustansiriyah J. Sci. 2020, 31, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alawi, R.A.; Al-Mashiqri, J.H.; Al-Nadabi, J.S.M.; Al-Shihi, B.I.; Baqi, Y. Date Palm Tree (Phoenix dactylifera L.): Natural Products and Therapeutic Options. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Alawi, R.; Alhamdani, M.S.S.; Hoheisel, J.D.; Baqi, Y. Antifibrotic and Tumor Microenvironment Modulating Effect of Date Palm Fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Extracts in Pancreatic Cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Alawi RA, Hoheisel JD, Alhamdani MSS, Baqi Y. Phoenix dactylifera L. (date palm) fruit extracts and fractions exhibit anti-proliferative activity against human pancreatic cancer cell lines. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42274. [CrossRef]

- Awla, N.J.; Naqishbandi, A.M.; Baqi, Y. Preventive and Therapeutic Effects of Silybum marianum Seed Extract Rich in Silydianin and Silychristin in a Rat Model of Metabolic Syndrome. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 1715–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimova, S.S.; Glushenkova, A.I. Eruca sativa Mill. In Lipids, Lipophilic Components and Essential Oils from Plant Sources; Azimova, S.S., Glushenkova, A.I., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testai, L.; Pagnotta, E.; Piragine, E.; Flori, L.; Citi, V.; Martelli, A.; Mannelli, L.D.C.; Ghelardini, C.; Matteo, R.; Suriano, S.; Troccoli, A.; Pecchioni, N.; Calderone, V. Cardiovascular Benefits of Eruca sativa Mill. Defatted Seed Meal Extract: Potential Role of Hydrogen Sulfide. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 2616–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grami, D.; Selmi, S.; Rtibi, K.; Sebai, H.; De Toni, L. Emerging Role of Eruca sativa Mill. in Male Reproductive Health. Nutrients 2024, 16, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barillari, J.; Canistro, D.; Paolini, M.; Ferroni, F.; Pedulli, G.F.; Iori, R.; Valgimigli, L. Direct Antioxidant Activity of Purified Glucoerucin, the Dietary Secondary Metabolite Contained in Rocket (Eruca sativa Mill.) Seeds and Sprouts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2475–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiripour, H.; Iranbakhsh, A.; Saadatmand, S.; Mousavi, F.; Oraghi Ardebili, Z. Exogenous Application of Melatonin and Chitosan Mitigate Simulated Microgravity Stress in the Rocket (Eruca sativa L.) Plant. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 218, 109294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, K.M.; Bhaskar, S.; Cheerala, V.S.K.; Battampara, P.; Reddy, R.; Neelakantan, S.C.; Reddy, N.; Ramamurthy, S.S. Review of Gold Nanoparticles in Surface Plasmon-Coupled Emission Technology: Effect of Shape, Hollow Nanostructures, Nano-Assembly, Metal–Dielectric and Heterometallic Nanohybrids. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.; Kathuria, D.; Ram, A.; Verma, K.; Sharma, S.; Tohra, S.K.; Sharma, A. Evaluation of Cytotoxic and Antioxidant Potential of Green-Synthesized Silver and Gold Nanoparticles from Nepeta leucophylla Benth. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, e202402679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Hu, C.; Ren, Y.; Lu, Y.; Song, Y.; Ji, Y.; He, J. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Presl Leaf Extracts and Its Antifungal Activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, F.N.; Abaker, Z.M.; Makawi, S.Z.A. Phytochemical Substances—Mediated Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO NPs). Inorganics 2023, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Qiu, D.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, Q.; Li, J. Cu2+-Doped Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks and Gold Nanoparticle (AuNPs@ZIF-8/Cu) Nanocomposites Enable Label-Free and Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Oral Cancer-Related Biomarkers. Anal. Methods 2024, 16, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.X.; Shameli, K.; Miyake, M.; Kuwano, N.; Ahmad Khairudin, N.B.; Mohamad, S.E.; Yew, Y.P. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Extract of Garcinia mangostana Fruit Peels. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 8489094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.E.F.; Pereira, A.C.; Resende, M.A.C.; Ferreira, L.F. Gold Nanoparticles: A Didactic Step-by-Step of the Synthesis Using the Turkevich Method, Mechanisms, and Characterizations. Analytica 2023, 4, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, S.; Joseph, S.; Koshy, E.P.; Mathew, B. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles Using Mussaenda glabrata Leaf Extract and Their Environmental Applications to Dye Degradation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 17347–17357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæbø, I.P.; Bjørås, M.; Franzyk, H.; Helgesen, E.; Booth, J.A. Optimization of the Hemolysis Assay for the Assessment of Cytotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, D.B. Multiple Range and Multiple F Tests. Biometrics 1955, 11, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailova, E.O. Green Silver Nanoparticles: An Antibacterial Mechanism. Antibiotics 2024, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Kumar, P.; Gautam, H.K. Citrus maxima Extract-Coated Versatile Gold Nanoparticles Display ROS-Mediated Inhibition of MDR-Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Cancer Cells. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 155, 108152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rmaidh, A.Y.; Al-Mahdawi, A.S.; Al-Obaidi, N.S.; Al-Obaidi, M.A. Organic Ligands as Adsorbent Surface of Heavy Metals and Evaluating Antibacterial Activity of Synthesized Complexes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 148, 111148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Radadi, N.S.; Al-Bishri, W.M.; Salem, N.A.; ElShebiney, S.A. Plant-Mediated Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using an Aqueous Extract of Passiflora ligularis, Optimization, Characterizations, and Their Neuroprotective Effect on Propionic Acid-Induced Autism in Wistar Rats. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 101921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galúcio, J.M.P.; de Souza, S.G.B.; Vasconcelos, A.A.; Lima, A.K.O.; da Costa, K.S.; de Campos Braga, H.; Taube, P.S. Synthesis, Characterization, Applications, and Toxicity of Green Synthesized Nanoparticles. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2022, 23, 420–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Dasgupta, S.C.; Dasgupta, A.K.; Gomes, A.; Gomes, A. Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) Conjugated with Andrographolide Ameliorated Viper (Daboia russellii russellii) Venom-Induced Toxicities in Animal Model. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 3404–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Święch, D.; Kollbek, K.; Jabłoński, P.; Gajewska, M.; Palumbo, G.; Oćwieja, M.; Piergies, N. Exploring the Nanoscale: AFM-IR Visualization of Cysteine Adsorption on Gold Nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 318, 124433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghramh, H.A.; Khan, K.A.; Ibrahim, E.H.; Setzer, W.N. Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) Using Ricinus communis Leaf Ethanol Extract, Their Characterization, and Biological Applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolev, D.; Shumilo, M.; Shulmeyster, G.; Krutikov, A.; Golovkin, A.; Mishanin, A.; Gorshkov, A.; Spiridonova, A.; Domorad, A.; Krasichkov, A.; Galagudza, M. Hemolytic Activity, Cytotoxicity, and Antimicrobial Effects of Human Albumin- and Polysorbate-80-Coated Silver Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moatamed, E.R.; Hussein, A.A.; El-Desoky, M.M.; Khayat, Z.E. Comparative Study of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Its Bulk Form on Liver Function of Wistar Rat. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2019, 35, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.E.; Hassan, M.A.; El-Nekeety, A.A.; Abdel-Aziem, S.H.; Bakeer, R.M.; Abdel-Wahhab, M.A. Zinc-Loaded Whey Protein Nanoparticles Alleviate the Oxidative Damage and Enhance the Gene Expression of Inflammatory Mediators in Rats. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2022, 73, 127030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshikh, M.; Ahmed, S.; Funston, S.; Dunlop, P.; McGaw, M.; Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Resazurin-Based 96-Well Plate Microdilution Method for the Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Biosurfactants. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, I.A.; Boyce, S.T. Agar Well Diffusion Assay Testing of Bacterial Susceptibility to Various Antimicrobials in Concentrations Non-Toxic for Human Cells in Culture. Burns 1994, 20, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parejo, I.; Codina, C.; Petrakis, C.; Kefalas, P. Evaluation of Scavenging Activity Assessed by Co(II)/EDTA-Induced Luminol Chemiluminescence and DPPH* (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) Free Radical Assay. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2000, 44, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).