Introduction

In traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture meridians consist of 14 major, invisible channels running longitudinally over the body surface, thereby connecting head, dorsum or abdomen, and limbs. Names have been assigned to the channels, generally based on the organs they reach: conception vessel, governor vessel, lung, large intestine, stomach, spleen, heart, small intestine, bladder, kidney, pericardium, triple energizer, gall bladder, and liver (Hu, Bao, & Ma, 1990; Worsley & Worsley, 2004; Z. Zhu & Hao, 1998). Major channels, plus many minor channels, form a complex system. Along the channels are at least 361 acupoints (Chapple, 2013) suitable for acupuncture stimulation. According to traditional theory, Qi and blood, the life supporting substances, flow in the meridian channels to keep the body at harmony: loss of harmony results in disease. Acupuncture can elicit Qi and regulate the balance of Yin and Yang, thereby having therapeutic effects. The meridian theory, along with concepts such as Five Elements and Yin-Yang, constitute the basis of traditional Chinese medicine (Men & Guo, 2010).

Acupuncture, which has been practiced in China and East Asia for at least 2500 years, is now becoming popular throughout the world. However, a scientific basis for acupuncture has not been established. Beginning in the 1950s, acupuncture research has focused on discovering the mechanism underlying the effects of acupuncture and the essence of meridians. A variety of observations have emerged, but strikingly absent is a dedicated anatomical structure defining the meridians. Nor is it clear how the meridians function to produce the observed effects of “needling” at specific anatomical points. Nevertheless, many observations support the existence of meridians. For example, some meridian channels coincide with low impedance lines found using body-surface conductance measurements (Ahn et al., 2008; Hu et al., 1990; Z. Zhu & Hao, 1998). Moreover, some channel paths have lower hydraulic resistance than nearby tissues (W. B. Zhang et al., 2008), channels can exhibit high-temperature bands revealed by infrared imaging (Hu et al., 1990; J. Li et al., 2012; Z. Zhu & Hao, 1998), and channels have louder and higher-pitched sounds generated by percussion than nearby, extra-channel regions (Xiong et al., 2023; Z. Zhu & Hao, 1998). Channels also show preferential migration of dyes and radioactive isotopes injected at acupoints (Hu et al., 1990; Xiong et al., 2023; Z. Zhu & Hao, 1998), and in some cases channels show visible red or white lines following acupuncture stimulation (Dimitrov et al., 2021). In one case, a patient with liver and kidney disorders exhibited prominent, bloody bands along the Gall Bladder and Kidney channels that disappeared when the patient recovered from these diseases (D. Li & Li, 1981).

Examination of the channels has revealed that they follow spaces between bones, muscles, and vascular/lymphatic vessels; they tend to be filled with connective tissue in addition to interstitial fluid (Dorsher, 2009; Langevin et al., 2002; Xie, 2002). Mast cells, nerve endings, and small vessels enrich the paths, especially at acupoints. Overall, meridians are viewed as a functional system without a dedicated anatomical structure (Dimitrov et al., 2021; A. H. Li, Zhang, & Xie, 2004; Maurer et al., 2019).

Needle stimulation at acupoints can induce DeQi (gaining Qi) in patients. When DeQi is induced, patients may feel heaviness, tingling, sour taste, and electric shock, depending on individual cases. Acupuncturists who grip the needles may experience a feeling similar to a fish biting bait on a fishhook. DeQi is more descriptively called “propagated sensations along channels (PSCs)”. These propagated sensations are not simply patient perceptions: they associate with measurable physiological activities, such as nerve discharges in the channels and high-potential reactions in the corresponding brain cortical somatosensory area, sometimes even without subjective feeling (Xu, Zheng, Pan, Zhu, & Hu, 2013; Z. Zhu et al., 2014). Propagated sensations, when traveling over neurological innervated segments, at speeds of about 10-20 cm/s (Hu et al., 1990; Z. Zhu & Hao, 1998), can be blocked by mechanical pressure along channel paths, by lowering temperature, and by injection of anesthetics (Hu et al., 1990; B. Zhu et al., 2002; Z. Zhu & Hao, 1998). Under pathological conditions, the propagating sensations tend to travel to diseased areas, straying from the usual paths (J. Zhang, Pei, Li, & al., 1981). Experiments show that PSCs are not simply nervous signals as often perceived (Longhurst, 2010), because moderate pressure (1 kg/cm2) applied to points on a channel can block PSCs while such pressure does not affect nerve conduction (Hu, Wu, Li, Li, & Gong, 1987). Moreover, non-nervous tissues, such as myofascia and muscles, are involved in PSCs (Langevin et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2013). Although PSCs are known to be important in acupuncture therapy, their essence and how they promote the therapeutic outcomes of acupuncture are unclear.

Studies of meridian essence have led to many theories that now fall largely into four categories: neurogenic theory, interstitial fluid theory, connective tissue theory, and physical field theory (J. Li et al., 2012; Longhurst, 2010; Qi, He, Gu, & al., 2024; Yang & Han, 2015; W. B. Zhang et al., 2008). To date, none of the proposals clearly defines the essence of PSCs and meridians or how a seemingly diffuse network propagates sensations: the meridian system appears to be a functional integration of many different tissues. The central question is how acupuncture signals transmit from one tissue to another without specialized structures or direct contact; the tissues involved may even be of different types. Such cross-tissue signal transmission, termed “ephaptic coupling”, has been observed in physiological studies (Buller & Proske, 1978; Katz & Schmitt, 1940; B. Zhu et al., 2002), but the mechanism is unknown. That is the main concern of this paper.

The Hypothesis

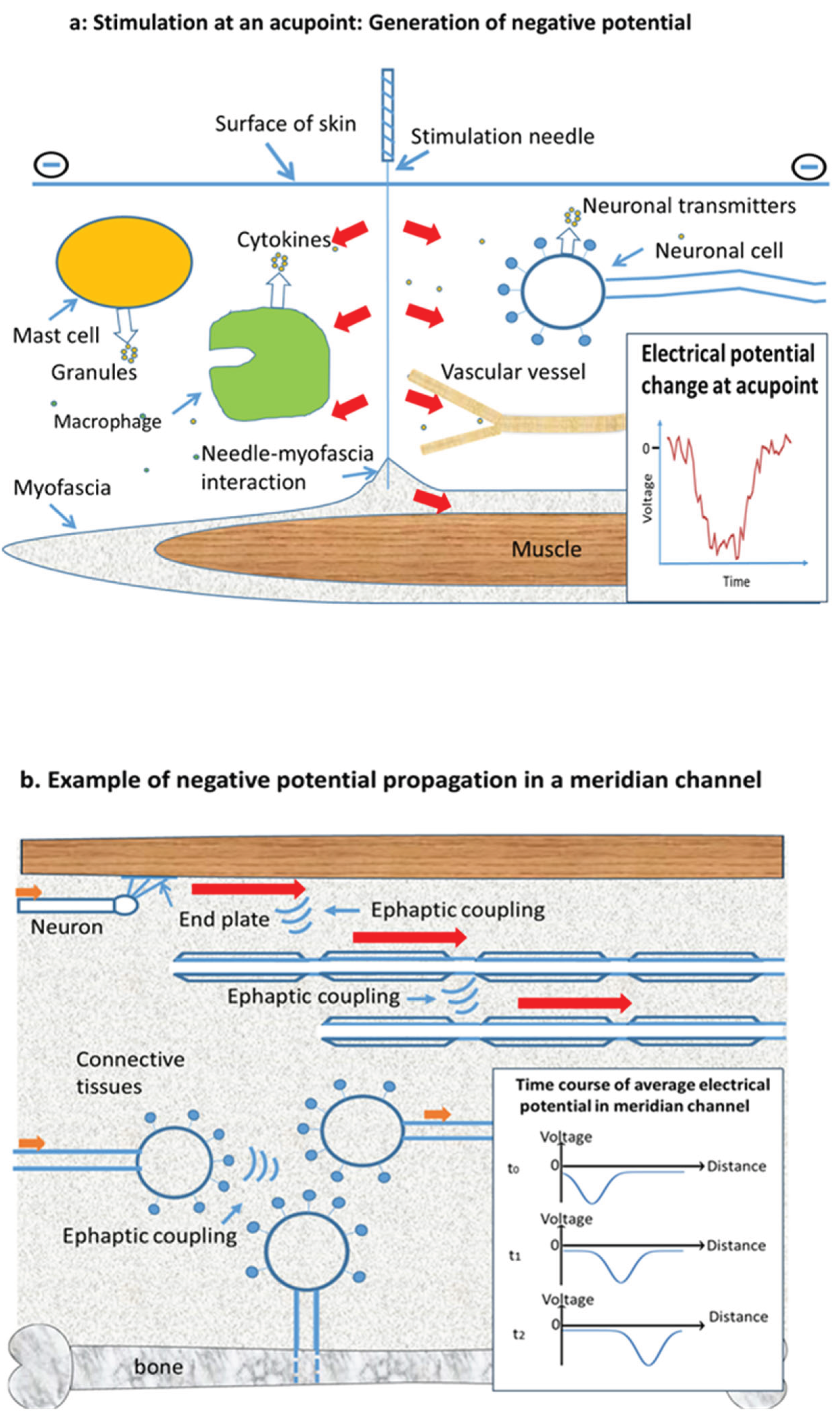

We postulate that the components of meridian superstructure collectively relay extracellular impulses of negative potential (EINPs) that jump from one excitable cell to another by self-propulsion and ion diffusion. These impulse waves are proposed to be the physical manifestation of the PSCs that generate the physiological effects of acupuncture occurring via the membrane depolarizing function of negative potentials.

Mechanistically, a sudden drop of electrical potential at a point in interstitial fluid would propel anions away from the point and attract cations toward it by Coulomb force due to a potential gradient. Additionally, negative potentials associate with high density of anions and low density of cations. Density gradients would cause anions to diffuse away from and cations toward the point of low potential. Such ion movements would lower the electrical potential at neighboring locations, causing an EINP to propagate to neighboring cells where it could excite cells. This is how EINP could propagate along a channel as a pulse initiated from either an active cell or from acupuncture (

Figure 1). Wherever EINP waves go, they would trigger membrane depolarization, which can have striking physiological effects (Abdul Kadir, Stacey, & Barrett-Jolley, 2018) in addition to eliciting action potentials in neurons and muscles.

We propose that EINPs due to needling at acupoints arise from three sources. One is the negative charge of human skin, which, relative to the dermis, can be as high as -30 mv (Foulds & Barker, 1983). A metal needle inserted into the dermis would introduce a negative potential at the acupoint. As expected, surface-insulated needles have reduced acupuncture efficiency (Zou & Huang, 2019). Second, needle insertion would inevitably pierce a few cell membranes, thereby releasing negative charge into the extracellular space. A third source is expected to be collagen, a major component of connective tissue (Fox, Gray, Koptiuch, Badger, & Langevin, 2014). Connective tissues provide matrices for channels and interact with the needle via collagen. Collagen possesses piezoelectric/converse-piezoelectric properties (Kamel, 2022) that, upon mechanical/electrical stimulation, can generate electrical potentials or deformation surrounding a needle. At acupoints, needle-introduced EINPs may cause mast cell degranulation, macrophage secretion of cytokines, and neurotransmitter secretion by neurons (Haslberger, Romanin, & Koerber, 1992; Hochner, Parnas, & Parnas, 1989; Kassel, Amrani, Landry, & Bronner, 1995). We propose that these biologically active materials will sensitize excitable cells around the area of needle insertion. Collective excitation would then generate effects, such as excitation of nerves that signal the central nervous system and that pass the signal along meridian channels.

We emphasize that the EINP idea is distinct from saltatory conduction, the rapid transmission of electrical signals (action potentials) along myelinated axons. In saltatory conduction, the signal appears to "jump" over the myelin sheath between two nodes of Ranvier, significantly speeding conduction compared to unmyelinated axons (Tonomura & Gu, 2023). Saltatory conduction is associated with a clearly defined anatomical structure while EINP propagation is not. Moreover, saltatory conduction takes place in a single cell while PSCs are postulated to transmit from one cell to another.

We postulate that the force generating PSCs is membrane polarization energy. It would drive propagation of both intracellular and extracellular action potentials in an energetically favored process following stimulation, such as skin puncture. Once an EINP is generated at a spot, it would propagate along an energy-favorable path, a meridian channel, because these channels would be more densely packed with excitable cells and would have thicker interstitial fluid than surrounding tissue. After an EINP wave passes, the excited cells would regain their negative intracellular resting potential and ion concentration at the expense of ATP hydrolysis.

Evaluation and Testing of the Hypothesis

The validity of the hypothesis can be assessed by considering its ability to explain existing observations. Propagation of EINP waves requires 1) that the wave path be rich in excitable membranes so the decaying EINP wave can be relayed and 2) that the path be filled with interstitial fluid so ions can move readily under the Coulomb force of potential and ion gradients. The specific path for each channel would be determined by these two conditions: they would be responsible for the major properties of the channel paths. For example, the channels are proposed to possess spaces containing interstitial fluid and therefore would have high electrical conductance (Ahn et al., 2008; Z. Zhu & Hao, 1998) and low hydraulic resistance (W. B. Zhang et al., 2008). That would account for migration of dye and radioactive isotopes along the channels. Point mechanical pressure is expected to squeeze fluid out of channels, thereby blocking propagating EINP waves. Since the channels are considered to be filled with an almost incompressible liquid, they are expected to respond to being struck by producing vibrations having an elevated frequency and amplitude: percussion on the channels generates sounds that are louder and have a higher pitch than sounds generated from nearby soft tissue (Xiong et al., 2023; Z. Zhu & Hao, 1998). High temperature bands could derive from ATP production. After the passage of an ENPI wave, depolarized cells are expected to restore the resting states of membrane potential and ion concentration by pumping out Na+ and Ca2+, a process that uses ATP (Raghavan, Fee, & Barkhaus, 2019) and inevitably generates heat. That would also cause higher CO2 content and lower O2 pressure in the channels (W. B. Zhang, Tian, Zhu, & Xu, 2009). Finally, in electroacupuncture a cathode rather than an anode is used as a test electrode, presumably because cathodes can provide negative potential for initiation of PSCs.

According to the hypothesis, PSCs can move from one tissue to another without synapses in neurons or gap junctions for cell-cell signaling. An example is seen in a rat model at the Zusanli acupoint: electrical signals transmit from superficial peroneal nerves to deep peroneal nerves even after both nerves have been severed from the spinal cord (Wang, Zheng, Lu, & Wu, 1987). A similar phenomenon has been observed with acupoints on a dorsal portion of the rat Foot Taiyang Bladder meridian (Guo et al., 2016).

Key support for the hypothesis is the detection of negative impulses in channels. For example, in an experiment with a rat model, a needle, serving for both stimulation and measurement, was inserted at a dorsal point equivalent to a human acupoint in the Bladder meridian. At approximately 500 ms after needle insertion, an impulse with a negative polarity of 60 mv, lasting about 30 ms, was observed (MA, Zheng, & Xie, 2001). Additionally, at an adjacent acupoint an impulse, composed mainly of negative potential, was measured by an inserted needle. A similar phenomenon was seen with the human Pericardium meridian channel (Spaulding, Ahn, & Colbert, 2013). These experiments provide a method for detecting the predicted waves of depolarization.

Rigorous testing of the hypothesis would involve measuring the negative potential impulses along the channels, especially at acupoints, when PSCs are elicited. Indeed, such impulses have been detected in a channel near the needle-stimulating point (Spaulding et al., 2013). We expect that the phenomenon will be seen in all channels and at distant acupoints by inserting needles at the sites and detecting the negative electric potentials as sensations move along a channel.

Implications of the Hypothesis

The hypothesis defines the physical nature of acupuncture-simulated PSCs, the EINP waves in the meridian channels. Since EINPs are measurable, their detection could have a major impact on acupuncture acceptance by establishing the existence of meridians. At the physiological level, the PSCs are proposed to functionally integrate interstitial fluids, the peripheral nervous system, the circulatory system, the immune system, the endocrine system, and muscle bundles into a large regulatory system. Understanding the interactions among the parts of this system through EINPs could lead to many new treatment modalities.

With respect to acupuncture practice, measurable EINP waves would enable a quantitative description of needle manipulation, a practice that is now based largely on individual experience: PSC is a subjective feeling by patients that is measured only indirectly by methods such as electromyography (Zhong et al., 2024). By measuring the amplitude, duration, and propagation velocity of EINP waves, the efficacy of the many needling techniques can be evaluated and optimized. In acupuncture efficacy testing, points outside the channels are used as negative or sham controls. Acupoints often fail to outperform sham controls when tested by standard means (Langevin et al., 2011). This paradox could be resolved by finding no EINP outside stimulation points. Overall, application of the hypothesis could greatly increase the rigor of acupuncture practice.

Limitations and Conclusions

Unresolved issues exist. For example, with some measurements, the amplitude of extracellular potential are small compared to the threshold required to evoke action potential in excitable cells: extracellular potentials are in some cases only a few negative mv (Dipalo et al., 2017), while the threshold for eliciting action potentials is on the order of -30 mv. That difference may be why acupuncturists facilitate PSCs by massaging skin along the target channel, by needling acupoints ahead of PSCs, and by repetitive stimulation at acupoints. While experiments show that a moving PSC can cause an electrical burst, largely of negative potential, at acupoints (MA et al., 2001), more attention is needed concerning the idea that acupoints may serve as energy refill stations that augment PSC signals. A separate issue is the inaccuracy of the extracellular potential measurement. Pulsed electrical potentials in interstitial fluid decrease rapidly with distance. Thus, the distance between the measuring pole and the source of potential needs to be more carefully considered than is currently the practice. Still another issue is the use of metal poles in measurements: they can flatten the potential’s sharp peaks due to electrochemical reactions at the metal-solution interface (Xu, Xu, Sun, Li, & Xu, 2018). Overcoming this issue will require technical advances. Nevertheless, we are optimistic that more refined amplitude measurements will establish a quantitative basis for the depolarization wave hypothesis.

In summary, acupuncture is proposed to treat disease by needle puncture of body surfaces to generate PSCs that move along the meridian channels to diseased sites. The critical question is how acupuncture signals jump from one cell to another without special structures or direct cellular contact. The EINP wave hypothesis provides a testable explanation by postulating that acupuncture-generated extracellular action potentials self-propel to nearby excitable cells through interactions between electrical fields and electrolytes and through ion diffusion. The negative potentials depolarize cell membranes and elicit additional action potential. Since the hypothesis is amenable to theoretical description and experimental testing, it could bring acupuncture into the purview of modern medicine.

Conflicts of Interests:

the authors do not have competing interests.

Author Contributions

J-Y Wang formulated the concepts; J-Y Wang and J Wang wrote an initial rough draft, K Drlica and J-Y Wang improved and completed the manuscript.

Funding

this research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for critical comments on the manuscript: Xilin Zhao and Bo Shopsin. The first author also thanks Professor Liaofu Luo for introducing him to meridians and for the helpful discussion on EINP theory of meridians. He also thanks acupuncturist Dr. Dafu Cao for sharing acupuncture experience.

References

- Abdul Kadir, L.; Stacey, M.; Barrett-Jolley, R. Emerging roles of the membrane potential: action beyond the action potential. Front Physiol 9 2018, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, A. C.; Colbert, A. P.; Anderson, B. J.; Martinsen, O. G.; Hammerschlag, R.; Cina, S.; Langevin, H. M. Electrical properties of acupuncture points and meridians: a systematic review. Bioelectromagnetics 2008, 29(4), 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, A. J.; Proske, U. Further observations on back-firing in the motor nerve fibres of a muscle during twitch contractions. J Physiol 285 1978, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapple, W. Proposed catalog of the neuroanatomy and the stratified anatomy for the 361 acupuncture points of 14 channels. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2013, 6(5), 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, N.; Atanasova, D.; Tomov, N.; Pirovsky, N.; Ivanova, I.; Stefanov, I.; al., e. Needle-nerve interaction in acupuncture: a morphological study. Bulgarian Journal of Veterinary Medicine 2021, 24(3), 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipalo, M.; Amin, H.; Lovato, L.; Moia, F.; Caprettini, V.; Messina, G. C.; De Angelis, F. Intracellular and extracellular recording of spontaneous action potentials in mammalian neurons and cardiac cells with 3D plasmonic nanoelectrodes. Nano Lett 2017, 17(6), 3932–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsher, P. T. Myofascial meridians as anatomical evidence of acupuncture channels. Medical Acupuncture 2009, 21(2), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulds, I. S.; Barker, A. T. Human skin battery potentials and their possible role in wound healing. Br J Dermatol 1983, 109(5), 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. R.; Gray, W.; Koptiuch, C.; Badger, G. J.; Langevin, H. M. Anisotropic tissue motion induced by acupuncture needling along intermuscular connective tissue planes. J Altern Complement Med 2014, 20(4), 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cao, D. Y.; Zhang, Z. J.; Yao, F. R.; Wang, H. S.; Zhao, Y. Electrical signal propagated across acupoints along Foot Taiyang Bladder Meridian in rats. Chin J Integr Med 2016, 22(7), 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslberger, A.; Romanin, C.; Koerber, R. Membrane potential modulates release of tumor necrosis factor in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse macrophages. Mol Biol Cell 1992, 3(4), 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochner, B.; Parnas, H.; Parnas, I. Membrane depolarization evokes neurotransmitter release in the absence of calcium entry. Nature 1989, 342(6248), 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Bao, J.; Ma, Y. People's Medical Publishing House; Beijing, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Wu, B.; Li, B.; Li, W.; Gong, S. [Further investigation on the mechanism underlying the phenomenon of channel blocking]. In Zhen Ci Yan Jiu; 1987; pp. 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, N. A. Bio-piezoelectricity: fundamentals and applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Biophys Rev 2022, 14(3), 717–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassel, O.; Amrani, Y.; Landry, Y.; Bronner, C. Mast cell activation involves plasma membrane potential-and thapsigargin-sensitive intracellular calcium pools. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 1995, 9(6), 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.; Schmitt, O. H. Electric interaction between two adjacent nerve fibres. J Physiol 1940, 97(4), 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevin, H. M.; Churchill, D. L.; Wu, J.; Badger, G. J.; Yandow, J. A.; Fox, J. R.; Krag, M. H. Evidence of connective tissue involvement in acupuncture. FASEB J 2002, 16(8), 872–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevin, H. M.; Wayne, P. M.; Macpherson, H.; Schnyer, R.; Milley, R.M.; Napadow, V.; Hammerschlag, R. Paradoxes in acupuncture research: strategies for moving forward. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011 2011, 180805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A. H.; Zhang, J. M.; Xie, Y. K. Human acupuncture points mapped in rats are associated with excitable muscle/skin-nerve complexes with enriched nerve endings. Brain Res 1012 2004, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, X. [From a case of hemorrhagic bands along the channels to explore the connection of meridian to internal organs]. China Acupuncture and Moxibustion 1981 1981, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Liang, H.; Dong, H.; Li, Y.; Ng, E. H.; Wu, X. Biophysical characteristics of meridians and acupoints: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012 2012, 793841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, J. C. Defining meridians: a modern basis of understanding. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2010, 3(2), 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MA, C.; Zheng, Z.; Xie, Y. Meridian-like character of reflex electromyogram activity in longissimus dorsi muscles. Chinese Science Bulletin 46 2001, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, N.; Nissel, H.; Egerbacher, M.; Gornik, E.; Schuller, P.; Traxler, H. Anatomical evidence of acupuncture meridians in the human extracellular matrix: results from a macroscopic and microscopic interdisciplinary multicentre study on human corpses. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2019, 6976892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Men, J.; Guo, L. Men, J., Guo, L., Eds.; A general introduction to traditional Chinese medicine; Science Press/CRC Press; FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; He, B.; Gu, Q.; al., e. Scientific exploration and hypotheses concerning the meridian system in traditional Chinese medicine[J]. Acupuncture and Herbal Medicine 2024, 4(3), 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, M.; Fee, D.; Barkhaus, P. E. Generation and propagation of the action potential. Handb Clin Neurol 160 2019, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, K.; Ahn, A.; Colbert, A. P. Acupuncture needle stimulation induces changes in bioelectric potential. Medical Acupuncture 2013, 25(2), 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonomura, S.; Gu, G. Saltatory conduction and intrinsic electrophysiological properties at the nodes of Ranvier of Aα/β-afferent fibers and Aα-efferent fibers in rat sciatic nerves. Molecular Pain 19 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zheng, J.; Lu, Z.; Wu, C. [Transmission of excitation between peripheral nerve endings-a study on the peripheral mechanism of propagated sensation along meridians]. Bulletin of Science and Technology 1987, 3(5), 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Worsley, J. R.; Worsley, J. B. Classical five element acupuncture, Volume I, Meridians and points, Fourth edition; J.R. Worsley, Inc, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H. [Study on Qi-passage of meridians and collaterals]. China Acupuncture and Combustions 2002, 22(9), 599–602. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, F.; Xu, R.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Hu, Q.; Song, X.; al., e. Application of biophysical properties of meridians in the visualization of pericardium meridian. J. Acupuncture and Meridian Studies 2023, 16(3), 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xu, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, M.; Xu, S. Experimental and Computational Studies on the Basic Transmission Properties of Electromagnetic Waves in Softmaterial Waveguides. Sci Rep 2018, 8(1), 13824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zheng, S.; Pan, X.; Zhu, X.; Hu, X. The existence of propagated sensation along the meridian proved by neuroelectrophysiology. Neural Regen Res 2013, 8(28), 2633–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M. N.; Han, J. X. Review and analysis on the meridian research of China over the past sixty years. Chin J Integr Med 2015, 21(5), 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Pei, T.; Li, Y.; al., e. [A pilot study of Qi reaching affected area]. China Acupuncture and Moxiconbustion 1981 1981, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. B.; Tian, Y. Y.; Li, H.; Tian, J. H.; Luo, M. F.; Xu, F. L.; Wang, R. H. A discovery of low hydraulic resistance channel along meridians. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2008, 1(1), 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. B.; Tian, Y. Y.; Zhu, Z. X.; Xu, R. M. The distribution of transcutaneous CO2 emission and correlation with the points along the pericardium meridian. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2009, 2(3), 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Yao, L.; Liu, Y. Z.; Wang, Y.; He, M.; Sun, M. M.; Wang, H. F. Objectivization study of acupuncture Deqi and brain modulation mechanisms: a review. Front Neurosci 18 2024, 1386108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Rong, P.; Ben, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Gao, X. Generating-sensation and propagating-myoelectrical responses along the meridian. Sci China C Life Sci 2002, 45(1), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Hao, J. Biophysics of acupuncture and moxibustion-Scientific verification for the greatest invention of China; Beijing Publisher; Beijing, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Yan, Z.; Yu, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; al., e. Studies on the phenomenon of latent propagated sensation along the channels i: the discovery of a latent PSC and a preliminary study of its skin electrical conductance. American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2014, 9(3), 8100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Huang, R. [Effect of electro-acupuncture, manual acupuncture and insulated manual acupuncture at Zusanli on the function of acute gastric stress ulcers in rat model]. J. Hubei Univ. of Chinese Medicine 21 2019, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).