1. Introduction

The lower urinary tract (LUT) is responsible for the storage and voiding phase, relying on the coordinated activity of a storage reservoir, the urinary bladder, and an outlet, composed of the bladder neck, the urethra, and the striated muscles of the external urethral sphincter (EUS), also known as the rhabdosphincter [

1,

2]. The physiology of micturition, which is conserved among mammals, involves electrical impulses traveling from supraspinal pathways along with three major players: thoracolumbar sympathetic nerves (hypogastric nerve and sympathetic chain), sacral parasympathetic and somatic nerves (pelvic and pudendal nerve) [

3]. Since the micturition cycle is controlled by complex neural mechanisms, disorders affecting either the central, the peripheral or the autonomic nervous system can result in LUT dysfunction [

4]. Symptoms of such dysfunction, such as incontinence or urinary retention, afflict over two billion individuals, profoundly impacting their quality of life due to the physical and psychosocial consequences [

4,

5]. The implications extend not only to humans but also to clinical veterinary care: dogs and cats experiencing LUT dysfunction may leave urine puddles in their resting spots or involuntarily dribble while moving [

3]. As in humans, this poses a significant concern due to the increased susceptibility to urinary tract infections, which can greatly affect the quality of life for both the animals and their caregivers [

3].

Neuromodulation strategies, which make use of transcutaneous or implanted electrodes to deliver an electrical current to the peripheral nervous system, e.g., sacral or tibial nerves, have been used in the last years as an alternative to pharmacological treatment to restore LUT control or relieve LUT symptoms [

6]. Among all, pudendal nerve stimulation is a promising alternative to sacral nerve stimulation in terms of long-term efficacy and voiding control, showing a response in 93% of patients for whom Sacral Nerve Stimulation, already approved by the Food and Drug Administration, had failed [

7,

8,

9]. The pudendal nerve is found within the sacral region and derives from the ventral branches of the sacral nerves. Its structure is well described in humans, where it consists of three ventral rami from S2-S4 of the sacral plexus that converge adjacent to the lateral wall of the pelvic cavity. Most of its path is associated with the branches of the internal pudendal artery and vein [

10]. The pudendal nerve as a whole carries sensorimotor stimuli from/to the genital and perineal area and performs a direct control of the pelvic and perineal striated musculature, such as the external anal sphincter (EAS) and EUS [

10]. Thus, the role of the pudendal nerve within the micturition process is mainly to support contraction of the EUS through cholinergic receptors responding to the somatic efferent function of the nerve when storage of urine is needed [

11]. However, it has also been proven the existence of an afferent pathway within the pudendal nerve: activation of the so-called ‘pudendal-to-bladder’ reflex can either evoke bladder contraction or relaxation depending on the frequency of stimulation [

12].

The presence of both sensory and motor fibers makes the pudendal nerve an optimal candidate for the use of a bidirectional intraneural prosthesis: after placing the prosthesis within nerve fascicles, bladder states can be detected from sensory signals while stimulation of motor fibers can be delivered based on the bladder real-time need, paving the way towards the restoration of a more physiological urination cycle [

13]. However, pudendal nerve stimulation is currently performed by using epineural electrodes placed beside the nerve, which lack selectivity in nerve fiber recruitment and overall nerve stimulation may cause side effects [

8,

9].

To develop custom bidirectional intraneural prostheses and to investigate this novel approach, animal studies are still required since the morphology of the target nerve is fundamental to optimize prosthesis design. However, Shen

et al. underlined the importance as well as the lack of an ideal animal model for the study of urinary bladder function [

14]. Concerning the pudendal nerve, its morphology, path, and sensorimotor components were well described in male and female rats [

15,

16,

17], female rabbits [

18], and male and female cats [

19,

20]. Common features include its origin from the lumbosacral region and a branching pattern as it enters the sacral plexus: while in humans a tripartite branching in a genital, a perineal, and a rectal component is described [

21], in the previously mentioned animal models two main branches, a motor and a sensory component, appears to leave the plexus and enter the ischio-rectal fossa. Selective stimulation of the pudendal nerve sensory branch proved to induce bladder contraction and increase voiding efficacy. However, selectivity was achieved from surgical exposure of the sensory branch, which translates poorly in humans. [

7,

22]. The use of intraneural prostheses as a tool for bidirectional communication with motor and sensory pathways has also been explored using Utah arrays as neural prostheses: their high invasiveness makes them very traumatic, especially when implanted within the peripheral nervous system [

23,

24]. Larger animals such as pigs offer more comprehensive data compared to smaller rodents, thereby providing valuable insights into clinical physiology having anatomical size and urinary system characteristics very similar to those of humans, compared to smaller animals such as rats, rabbits, and cats [

25,

26]. Pigs are particularly useful for research on the initiation of micturition, as micturition patterns observed in female pigs mimic those of humans, including urethral relaxation, which is significantly different from that observed in rats and cats [

25,

27]. The porcine pudendal nerve is an ideal candidate, but knowledge about its morphology and pathway is limited.

Here, we present anatomical observations on the porcine pudendal nerve from dissection to histological and immunohistochemical evaluation. The aim is to identify a minimally invasive surgical approach to target pudendal nerve fascicles responsible for EUS control and to identify the spatial distribution of its motor and sensory fibers. The size of the pudendal nerve, number of fascicles, fascicle distribution, and fiber function is indeed fundamental for the development of highly selective customized intraneural prosthesis. These results pave the way for neuromodulation studies on large animal models to treat urinary bladder dysfunction and restore the physiological urination cycle.

We can summarize the contribution of this study with the following list:

Describing the surgical procedure to implant an intraneural interface within the porcine pudendal nerve without muscle resection and confirmation of the EUS recruitment with neuromodulation studies.

Describing the branching, and the morpho-physiology of the porcine pudendal nerve at the level of the surgical exposure.

3. Discussion

Previous literature studies highlighted the need for animal models for developing innovative strategies to treat LUT dysfunction [

14]. Thor

et al. emphasized the importance of investigations into the afferent and efferent neurons innervating perineal muscles in large animal species [

2]. Pigs offer the advantages of having anatomical, size, and urinary system characteristics very similar to those of humans, thus providing results more easily translated into clinical research [

25].

The pudendal nerve anatomy in the swine species was found to be poorly described, beside some general descriptions found in veterinary textbooks [

28], it was not possible to find a detailed description of a standardized approach to surgically target the pudendal nerve, nor an extensive characterization of its branching pattern, morphology, and functional anatomy. It was thus necessary to work on dead animals to precisely describe the nerve path and thus generating a pudendal nerve surgical access. An ischio-rectal approach was adopted since it reduces the risk of abdominal viscera damage [

18]. First, we approached the sciatic nerve as described by Strauss

et al. [

29]; then rostrally following its course towards the spine, it was possible to see its shared emergence from the sacral spinal nerves with the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve was identified as lying near the pudendal vein and artery. Once the nerve was identified, muscle and ligament-sparing surgical access was tune-fined as described in

Section 4.1. The S1 pudendal spinal origin was the only minimally invasive approachable segment. Indeed, in mammals, the pudendal nerve generally arises from the spinal nerves in the lumbosacral region, forming a sacral plexus in the pelvic region. It then enters the pelvic cavity and originates as the proper pudendal nerve, which lies beside the sacrospinous ligament. At the level of the ischio-rectal fossa, it then branches off to go to the perineal muscles (EUS, EAS, bulbospongious muscle, ischiocavernous) [

11]. Ischio-rectal approach for pudendal neuromodulation was described in other animal models, mainly rats, and cats. However, the described incision was created in close proximity to the base of the tail, and both muscle and fat were excised [

7]. The resection of gluteal muscles makes the clinical translation of this study much more difficult. Therefore, surgically accessing the proper pudendal nerve and creating a space for the implantation of a neuroprosthesis in a muscle and ligament-sparing approach is not possible. We thus decided to target the S1 pudendal spinal origin as the site for the implantation of neural prostheses. It is worth noting that, as highlighted by Barone

et al. [

28], the anatomical variability between species and animals is very wide, so the S1 target identified in this study as the most cranial sacral root could emerge from other sacral vertebrae in some cases. Stimulation of S1, described in

Section 4.2., showed that at this location it is possible to target EUS motor fiber. Giannotti

et al. [

13] had already indirectly shown that this segment contains also sensory fibers from which it is possible to estimate the bladder state. Thus, this surgical approach could be an ideal candidate for the implantation of a bidirectional intraneural prosthesis enabling to selective targeting of motor and sensory fibers. Selectivity in neural fibers engaging was demonstrated to be highly desirable to restore continence, increase voiding efficacy, and reduce possible side effects such as detrusor-sphincter-dyssynergia, but so far this was achieved by implanting multiple neural prostheses in pudendal nerve sensory and motor branches [

7,

22,

30]. The implantation of a single bidirectional prosthesis could reduce tissue damage and surgical complications.

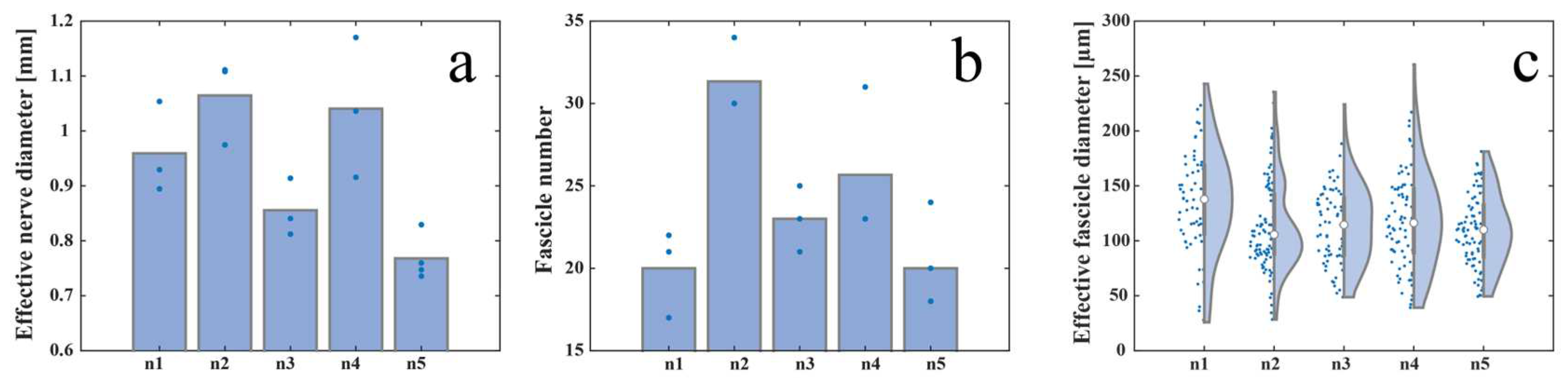

Once the implantation site was identified, we attempted to histologically characterize the S1 pudendal spinal origin in its morphology. This will allow the future development of custom neural prostheses based on the nerve dimensions and morphology. Foditsch

et al. 2014 previously attempted to histologically characterize the pudendal nerve, reporting a highly variable nerve diameter ranging from 0.2 to 1.1 mm [

31]. However, these results are poorly comparable to those shown here since their access to the pudendal nerve has been performed in laparoscopy, thus approaching the nerve within the perineal region. Furthermore, their animal size was lower and females instead of males were used; thus, it is reasonable that our findings show a higher nerve diameter, with a minimum value of around 0.8 mm. Generally, previous studies have focused efforts on characterizing specific pudendal nerve branches: Bremer

et al. histologically characterized the motor and the sensory branch of the pudendal nerve in rats [

32]; the motor branch in female rats has been also analyzed by Kane

et al. [

33], but the characterization of the proper pudendal nerve before its branching has not been reported in rats. An extensive characterization of the dorsal nerve of the penis, a branch of the pudendal nerve, was reported in cats, but these results are not comparable to them here described for the different locations examined [

34]. A histological section of pudendal nerve fascicles was also reported in monkeys but the sample was explanted from the pelvic region instead of the ischio-rectal [

35]. Finally, a deep analysis of the human pudendal nerve was described by Gustafson

et al. [

21], but also in this case the focus has been posed on the nerve branches instead of the sacral spinal nerves that originate the pudendal nerve. This work represents the first extensive description of the porcine pudendal nerve at the level of the S1 pudendal spinal origin, which can be targeted with muscle and ligament-sparing surgery. We reported an intra-animal and inter-animal characterization of the S1 tract, estimating the parameters of effective nerve diameter, effective fascicle diameter, and fascicle number. The diameter of the nerve was found to increase progressively in the caudal direction, due to both progressive branching of the nerve and increasing fascicle diameter. In each case, a high standard deviation demonstrates the high anatomical variability making it difficult to extrapolate conclusions. The staining method chosen also seems to have an impact in calculating the actual value of nerve size. However, the parameters obtained allow for indications regarding the average number of fascicles and the size range of the S1 tract of the porcine pudendal nerve, paving the way for optimized sizing of ad hoc developed neural prostheses.

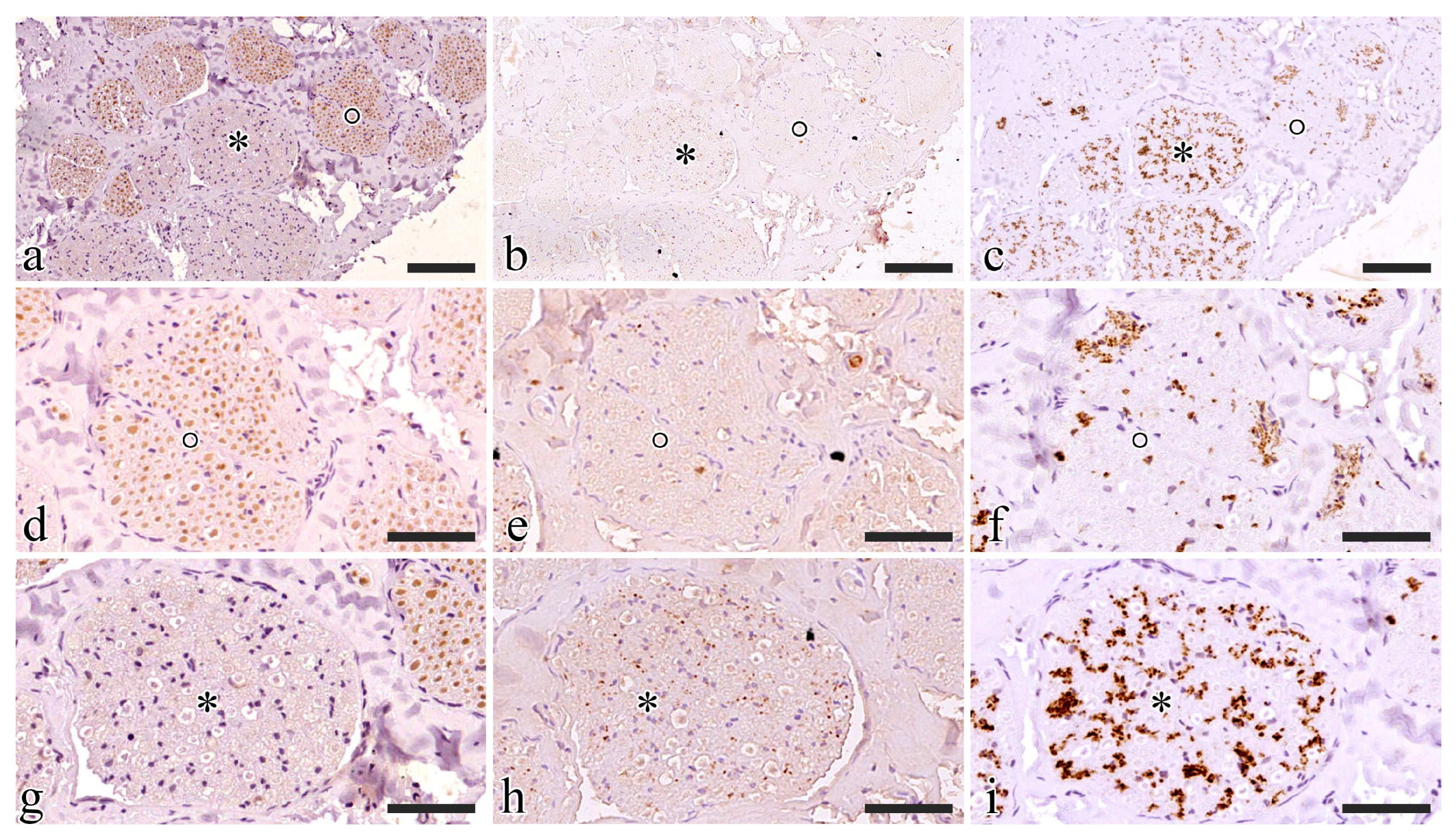

Micturition, as reported above, is, however, a complex physiological process where the pudendal nerve not only controls the sphincteric contraction and relaxation of the EUS but has been shown to take indirectly part of the bladder contraction or relaxation throughout the ‘pudendal-to-bladder’ reflex [

12]. Thus, the functional phenotype of pudendal nerve fibers and their spatial distribution were investigated using selected antibodies (TH, ChAT, P-substance). In the current study, S1 pudendal spinal origin was found to be a mixed nerve where somatic and autonomic neurotransmitters are present, confirming also in pigs Timoth

et al. fundings in contrast to the prevailing belief that it is purely somatic [

36]. While we can assume that TH immunoreactive fibers do belong to the sympathetic system, we cannot conclude that ChAT-positive fibers also include parasympathetic preganglionic fibers that might belong to the pelvic nerve which also originate from S1. However, the probability that they are preganglionic pelvic fibers is not high since in both rats and rabbits it has been seen that the pelvic immediately branches from S1, entering the pelvic plexus within the pelvic cavity, while the pudendal nerve and sacral plexus lie on the dorsal surface of the ischium to enter the pelvic cavity within the ischio-rectal fossa [

15,

18]. The presence of TH-positive fibers in pigs highlights the role of the pudendal nerve: besides the sensory and sensorimotor innervation of the striated perineal muscles, this has also been shown to provide sympathetic postganglionic innervation to the pelvic organs [

15]. More precisely, sympathetic innervation has been hypothesized to be responsible for the innervation of the penis and the control of the genitourinary system in rats [

37,

38,

39].

Electrical stimulation of the S1 pudendal spinal origin resulted in EUS contraction, confirming that this location is suitable for pudendal neuromodulation experiments aiming at restoring lower urinary tract dysfunction. EAS showed to have a lower activation threshold compared to EUS and reaches at lower current amplitude its maximum contraction level. The fact that EAS is activated for lower currents suggests the need to use stimulation that selectively activates only EUS. This is necessary in order to modulate EUS activity to restore urinary dysfunction without inducing problems such as fecal incontinence. For this reason, the use of an intraneural prosthesis could provide the required selectivity, as already shown in human upper limb amputees [

40]. A limitation of this preliminary study is that the electrical contacts of the intraneural electrode implanted were all activated simultaneously, making it impossible to test the ability to be selective toward EUS. Future studies will focus on stimulating one site at a time in order to find contacts that selectively target the fibers responsible for controlling the EUS sphincter. In addition, future studies will aim to understand how to translate the results of this study performed on S1 in pigs into humans, where the pudendal nerve originates at S2-S4, with a major contribution from S3.

Our results showed a spatial separation between the TH and SP positive fibers and the ChAT positive fibers, suggesting a spatial organization of fascicles mainly responsible for somatic control of perineal muscles (ChAT positive areas) and fascicles mainly responsible for carrying sensory information from the pelvic area and autonomic control of genital functions. This funding will open the possibility for further neuromodulation studies targeting the pudendal nerve at the S1 level with minimally invasive implanted bidirectional intraneural prostheses which could selectively interact with the functionally different areas of the pig pudendal nerve, thus enabling both the monitoring of bladder state from sensory fibers both the control of the sphincters with motor ones.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Surgical Site and Pudendal Gross Anatomy

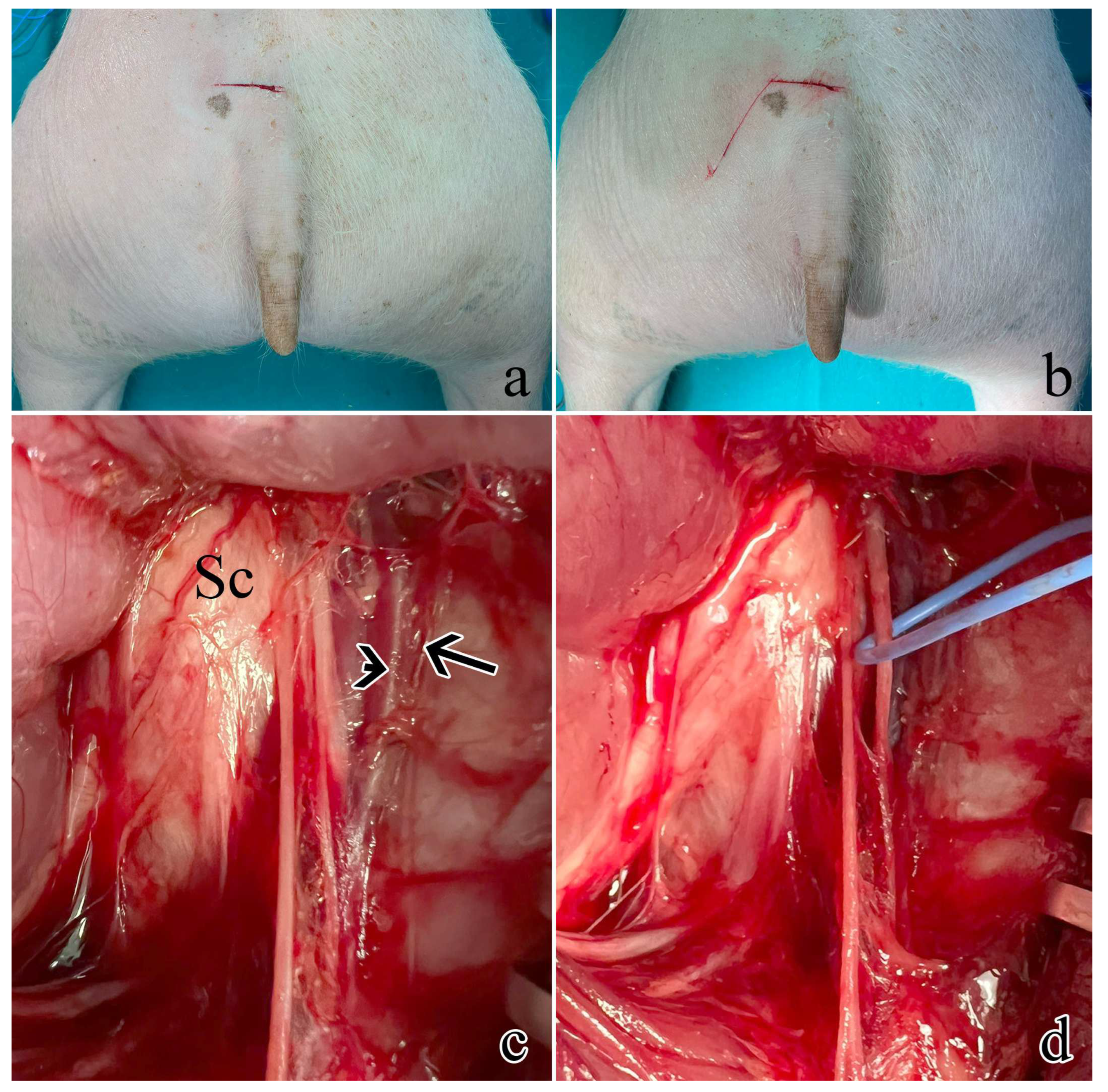

The surgical procedure was defined by using three male animals unrelated to this study that were dissected to identify the pudendal sacral spinal nerves and their accessibility. The rostral S1 pudendal spinal origin was selected as the implantation site for neuromodulatory experiments.

Five male farm pigs (Azienda Agricola e Allevamento Alessandro Stassano, Cedri di Peccioli Pisa) weighing 30-35 kg were used. The animals received premedication with Zoletil

® at a dosage of 10 mg/kg. Subsequently, they were induced into anesthesia through the intravenous administration of Propofol at a dosage of 2 mg/kg, followed by maintenance under 1–3% sevoflurane in a mixture of air containing 50% oxygen. Throughout the procedure, continuous monitoring was employed to track oxygen saturation, arterial pressure, and heart rate. Surgical access was performed to expose the left pudendal nerve a first cutaneous incision was made on a transversal plane located 6 cm rostrally from the base of the tail, 2 cm wide from the sagittal plane (

Figure 6a); a second cutaneous incision was performed starting from the lateral end of the first one going caudally and laterally on a 30° angle (

Figure 6b) ideally following the separation between the muscles gluteus superficialis and medius; after the exposure of the gluteal fascia, the gluteus superficialis and medius were retracted to expose the sciatic nerve (

Figure 6c). Once the sciatic nerve was found, the pudendal one was identified medially lining the internal pudendal artery and vein (

Figure 6d).

4.2. Intraneural Electrode Implantation and Electrical Stimulation

Once the rostral pudendal sacral spinal nerve was identified, an intraneural electrode was implanted within nerve fascicles. The design of the custom-developed intraneural electrode was inspired by the Transversal Intrafascicular Multichannel Electrode (TIME) [

41]. The intraneural electrode was composed of 16 electrical contacts coated with iridium oxide (IrOx) laying onto a flexible polyimide substrate. A detailed description of the design and fabrication procedure can be found in a previous study of our group [

13], while the insertion procedure has been described by Boretius et al. [

41]. Briefly, the intraneural electrode was linked to a suture needle, which was treaded within nerve fascicles; the needle was then pulled from the opposite side of the nerve, allowing the electrical contacts to interface nerve fascicles. The electrode was then connected to a TDT system (Tucker-David Technologies Inc., TDT, US) to provide the nerve with an electrical current injected through the electrical contacts. The electrical current waveform was composed of biphasic cathodic first stimuli, with increasing current amplitude ranging from 100 to 3000 µA delivered in 20 steps with three repetitions for each current amplitude and 200 µs pulse width (

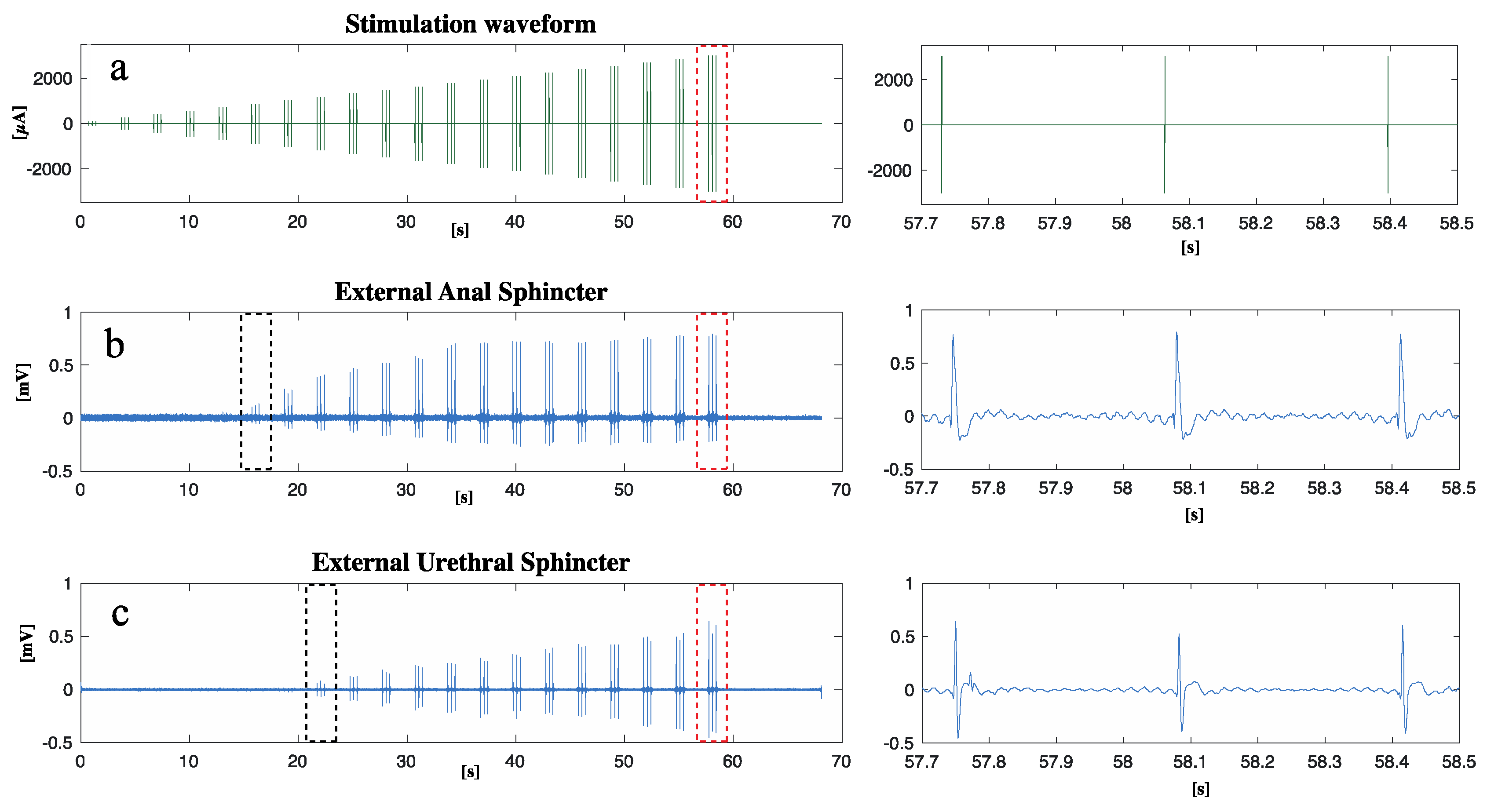

Figure 2a). Activation of the external anal sphincter was visually monitored, to confirm correct identification of the pudendal nerve.

In one animal, the activation of the external anal sphincter and the external urethral sphincter was also quantified by measuring their EMG activity. EMG of the external anal sphincter was measured by placing needle electrodes (SpesMedica, Ita) at 9 and 3 o’clock as described by Keung [

42]. The external urethral sphincter was implanted with needle electrodes (SpesMedica, Ita), after performing a midline ventral incision above the pubic bone to expose the muscle.

4.3. Histology

After humane sacrifice, the pudendal nerve was then dissected by recovering its roots and branches, placed on a polystyrene sheet, and fixed in 10% buffered formalin.

S1 pudendal spinal origin nerve was deeply characterized for its morphology and fibers’ immunophenotype. Formalin-fixed samples were routinely processed for either paraffin or JB-4 resin embedding. From the 5 animals (n1, n2, n3, n4, n5), both nerves were isolated and sampled.

From one animal (n5), the S1 segment from both the left and right pudendal nerve was embedded in 6 consecutive 3 mm long blocks and then underwent three different processing procedures (in pairs) as follows. Blocks 1 and 4 were paraffin-embedded and stained following a standard Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) procedure; blocks 2 and 5 were JB4 embedded and stained with Toluidine Blue (TB); blocks 3 and 6 underwent osmium tetroxide (OSO4) post-fixation before JB4 embedding. All the blocks were serially sectioned to analyze S1 pudendal nerve segment changes within the same animal. Blocks were cut using a microtome into 5 μm thick sections 100 μm apart. A total of 87 images of S1 pudendal nerve histological sections were obtained, including 18 H&E sections, 32 TB sections, and 37 OSO4 sections. The parameters evaluated were the number of fascicles, the effective fascicle diameter, and the effective nerve diameter, where effective means the diameter of the equivalent circle having the same area of the fascicles or nerve, respectively. This procedure also allowed to measure changes related to the sample processing procedure. Measures were obtained by using a custom algorithm implemented in MATLAB (MathWorks, US) after semi-automatic segmentation of histological images (ImageJ, National Institutes of Health, US) where nerve and fascicle contours have been highligthed. Statistical analysis was performed by applying a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test using MATLAB (MathWorks, US).

Samples obtained from the left pudendal nerve of the 4 remaining animals were cut into three blocks and paraffin-embedded. Three sections per block were stained with Mallory trichrome to measure the number of fascicles, effective fascicle diameter, and effective nerve diameter.

4.4. Immunohistochemistry

Choline Acetyltransferase (ChAT), Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), and Substance P (SP) were chosen as neuronal markers to investigate the sensorimotor composition of the S1 tract. ChAT, by catalyzing the transfer of an acetyl group from the coenzyme acetyl-CoA to choline, yielding acetylcholine, will unequivocally identify somatic motoneurons-derived fibers in S1 and/or parasympathetic preganglionic fibers; TH was instead selected as a marker of postganglionic sympathetic fibers since it catalyzes the conversion of L-tyrosine into L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine which is a precursor of dopamine, norepinephrine and epinephrine; Substance P is instead a marker of sensory neurons.

Briefly, after paraffin embedding and sectioning, tissues were rehydrated for the immunostaining: epitope retrieval was carried out at 120°C in a pressure cooker for 3 min with a Tris/EDTA buffer (pH 9.0); peroxidase quenching was carried out by incubation with 1% H2O2in PBS for 7 min at room temperature (RT). Non-specific binding was prevented by incubating slides in a blocking solution composed of 0,05% Triton X (TX)-100 and 2% bovine serum albumin (SP-5050, Vector Labs) for 1 h at RT. Slides were then incubated with either goat polyclonal anti-Choline Acetyltransferase (ChAT) antibody (AB144P, Merk, 1:100), rabbit polyclonal anti-Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody (SC14007, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200), or rat monoclonal anti-Substance P (SP) antibody (GTX38990, Gentex, 1:200) overnight at 4°C. Then, slides were rinsed in PBS (3x10 min), and incubated with a biotinylated anti-goat (for ChAT, BA-9500, Vector Labs) or anti-rabbit (for TH, BA-1100, Vector Labs) or anti-rat IgG antibody (for SP, BA-9400, Vector Labs). Sections were again rinsed in PBS (3x10 min) and incubated for 30 minutes with ABC complex (PK-2100, Vector Laboratories) at RT. Staining was visualized by incubating sections in diaminobenzidine solution (SK-4105, Vector Labs). Before dehydration and mounting, slides were counterstained with Hematoxylin for 7 seconds to stain nuclei. The specificity of immunohistochemical staining was tested by replacing the primary antibodies with PBS. Under these conditions, staining was abolished. Whole slide images were acquired with Nano Zoomer Hamamatsu slide scanner at a magnification of 20x with automatic focusing.

Fascicles were scored for ChAT immunoreactivity, assuming that negative fascicles were mostly TH immunoreactive. Score ranged from a minimum of 1, corresponding to 25% of ChAT positivity, and 4 corresponding to 100% ChAT positivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G., S.Mi., S.Mu, and G.D.P.; methodology, A.G., S.Mu., A.P., V.M.; validation, A.G., S.Mu., A.B., and V.M.; formal analysis, C.V., and A.G.; investigation, A.G., F.B., S.Mu, G.L., A.P.; resources, S.Mi., V.M., A.B.; data curation, A.G., and C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., and V.M; writing—review and editing, A.G., V.M., S.Mi, A.B., S.Mu; visualization, A.G., V.M., and C. V; supervision, S.Mi; project administration, S.Mi.; funding acquisition, S.Mi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

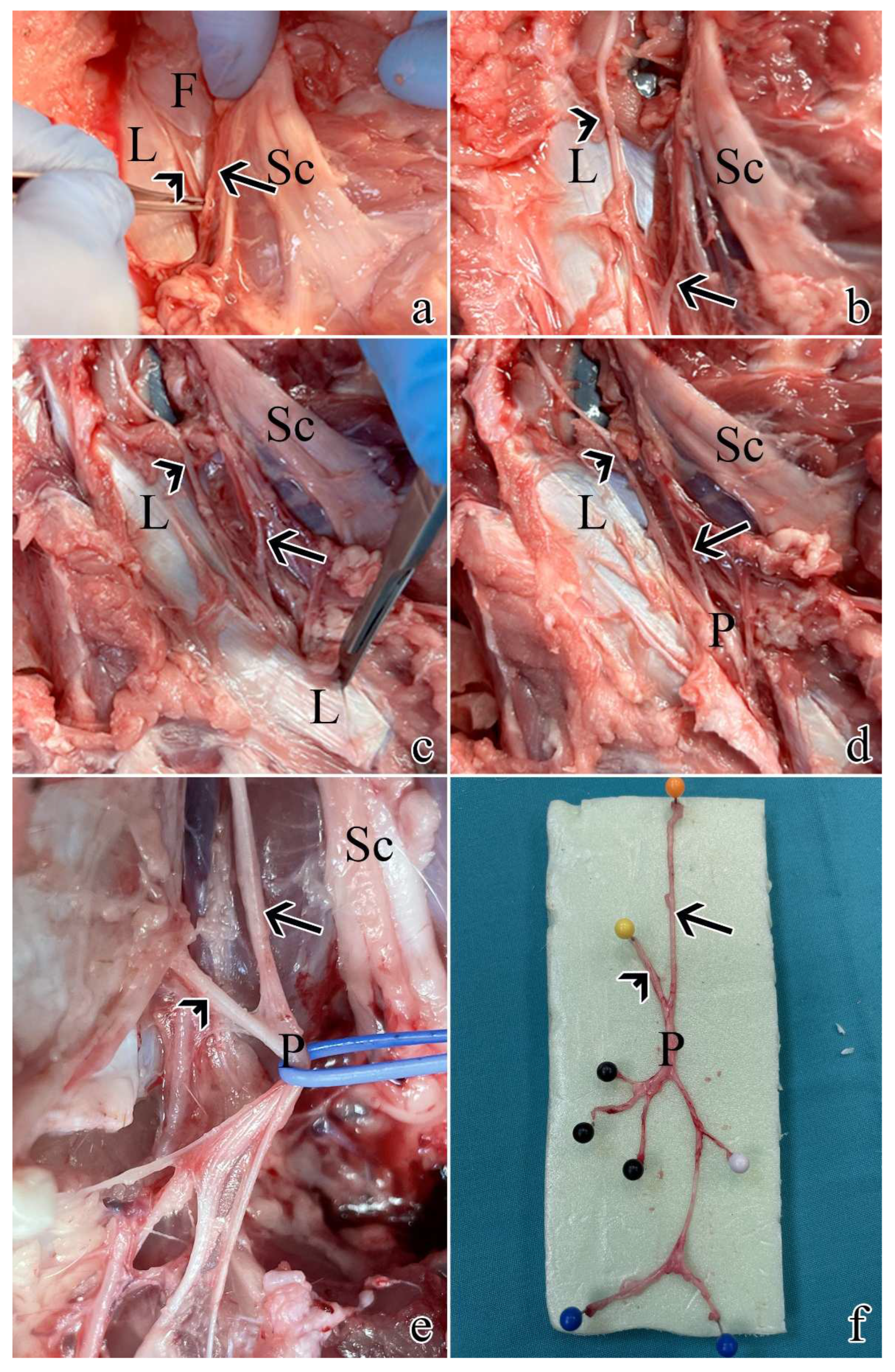

Figure 1.

Post-sacrifice dissection of all pudendal nerve origins and branches: a) exposure of S1 as described in

Section 4.1. using a muscle and ligament-sparing transgluteal surgery; b) the thoracolumbar fascia was removed rostrally and caudally to expose S2; c) caudal dissection allowed the identification of the sacrospinous ligament; d) resection of the ligament allowed to visualize the proper pudendal nerve; e) the pudendal nerve gives rise of multiple branches; f) pudendal nerve sample with its S1 and S2 origins and branches: black pins highlight the splanchnic component, while blue and white pins the cutaneous ones. Arrows highlight S1, while arrowheads indicate S2. L = sacrospinous ligament; F = thoracolumbar fascia; Sc = sciatic nerve; P = pudendal nerve.

Figure 1.

Post-sacrifice dissection of all pudendal nerve origins and branches: a) exposure of S1 as described in

Section 4.1. using a muscle and ligament-sparing transgluteal surgery; b) the thoracolumbar fascia was removed rostrally and caudally to expose S2; c) caudal dissection allowed the identification of the sacrospinous ligament; d) resection of the ligament allowed to visualize the proper pudendal nerve; e) the pudendal nerve gives rise of multiple branches; f) pudendal nerve sample with its S1 and S2 origins and branches: black pins highlight the splanchnic component, while blue and white pins the cutaneous ones. Arrows highlight S1, while arrowheads indicate S2. L = sacrospinous ligament; F = thoracolumbar fascia; Sc = sciatic nerve; P = pudendal nerve.

Figure 2.

After the implantation of an intraneural prosthesis, an electrical current was delivered to S1 while the EAS and EUS EMG activity was measured: a) waveform of the stimulation current delivered; b) EAS EMG response to stimulation; c) EUS EMG response to stimulation. A close-up of the region marked with red dots can be found on the right respectively for a, b, and c. Black dots in b and c show the first contraction of the EAS and EUS respectively.

Figure 2.

After the implantation of an intraneural prosthesis, an electrical current was delivered to S1 while the EAS and EUS EMG activity was measured: a) waveform of the stimulation current delivered; b) EAS EMG response to stimulation; c) EUS EMG response to stimulation. A close-up of the region marked with red dots can be found on the right respectively for a, b, and c. Black dots in b and c show the first contraction of the EAS and EUS respectively.

Figure 3.

Inter-animal variability measured as a) effective nerve diameter, b) fascicle number, and c) effective fascicle diameter among five animals.

Figure 3.

Inter-animal variability measured as a) effective nerve diameter, b) fascicle number, and c) effective fascicle diameter among five animals.

Figure 4.

Intra-animal variability measured by serially sectioning and processing with three different methods (a-b-c) the left (d-e-f) and right (g-h-i) S1 pudendal nerve tract: a) example of H&E stained paraffin-embedded section; b) example of TB stained JB4-embedded section; c) example of OSO4 post-fixed JB4-embedded section; d) effective nerve diameter, e) fascicle number, and f) effective fascicle diameter for the left pudendal nerve; g) effective nerve diameter, h) fascicle number, and i) effective fascicle diameter for the right pudendal nerve (the bars in d, e, g, h and the white circle in f and i represent the mean value of the previously mentioned parameters).

Figure 4.

Intra-animal variability measured by serially sectioning and processing with three different methods (a-b-c) the left (d-e-f) and right (g-h-i) S1 pudendal nerve tract: a) example of H&E stained paraffin-embedded section; b) example of TB stained JB4-embedded section; c) example of OSO4 post-fixed JB4-embedded section; d) effective nerve diameter, e) fascicle number, and f) effective fascicle diameter for the left pudendal nerve; g) effective nerve diameter, h) fascicle number, and i) effective fascicle diameter for the right pudendal nerve (the bars in d, e, g, h and the white circle in f and i represent the mean value of the previously mentioned parameters).

Figure 5.

Functional characterization of the S1 pudendal nerve tract by evaluating the immunoreactivity to ChAT (a-d-g), SP (b-e-h), and TH (c-f-i). a), b), and c) show the same region exposed to ChAT, SP, and TH respectively; d), e), and f) show the fascicle highlighted with a circle exposed to ChAT, SP, and TH respectively; g), h), and i) show the fascicle highlighted with an asterisk exposed to ChAT, SP, and TH respectively. Scale bars are equal to 100 µm in a-c and 50 µm in d-i.

Figure 5.

Functional characterization of the S1 pudendal nerve tract by evaluating the immunoreactivity to ChAT (a-d-g), SP (b-e-h), and TH (c-f-i). a), b), and c) show the same region exposed to ChAT, SP, and TH respectively; d), e), and f) show the fascicle highlighted with a circle exposed to ChAT, SP, and TH respectively; g), h), and i) show the fascicle highlighted with an asterisk exposed to ChAT, SP, and TH respectively. Scale bars are equal to 100 µm in a-c and 50 µm in d-i.

Figure 6.

Surgical procedure to expose the rostral S1 pudendal spinal origin: a) cutaneous incision on a transversal plane; b) second obliquus cutaneous incision; c) exposure and retraction of the gluteus superficialis and medius. Arrow indicates the pudendal artery, the arrowhead shows the pudendal vein, while Sc is the sciatic nerve; d) the pudendal one was identified medially lining the internal pudendal artery and vein and highlighted with the blue marker.

Figure 6.

Surgical procedure to expose the rostral S1 pudendal spinal origin: a) cutaneous incision on a transversal plane; b) second obliquus cutaneous incision; c) exposure and retraction of the gluteus superficialis and medius. Arrow indicates the pudendal artery, the arrowhead shows the pudendal vein, while Sc is the sciatic nerve; d) the pudendal one was identified medially lining the internal pudendal artery and vein and highlighted with the blue marker.