Submitted:

21 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

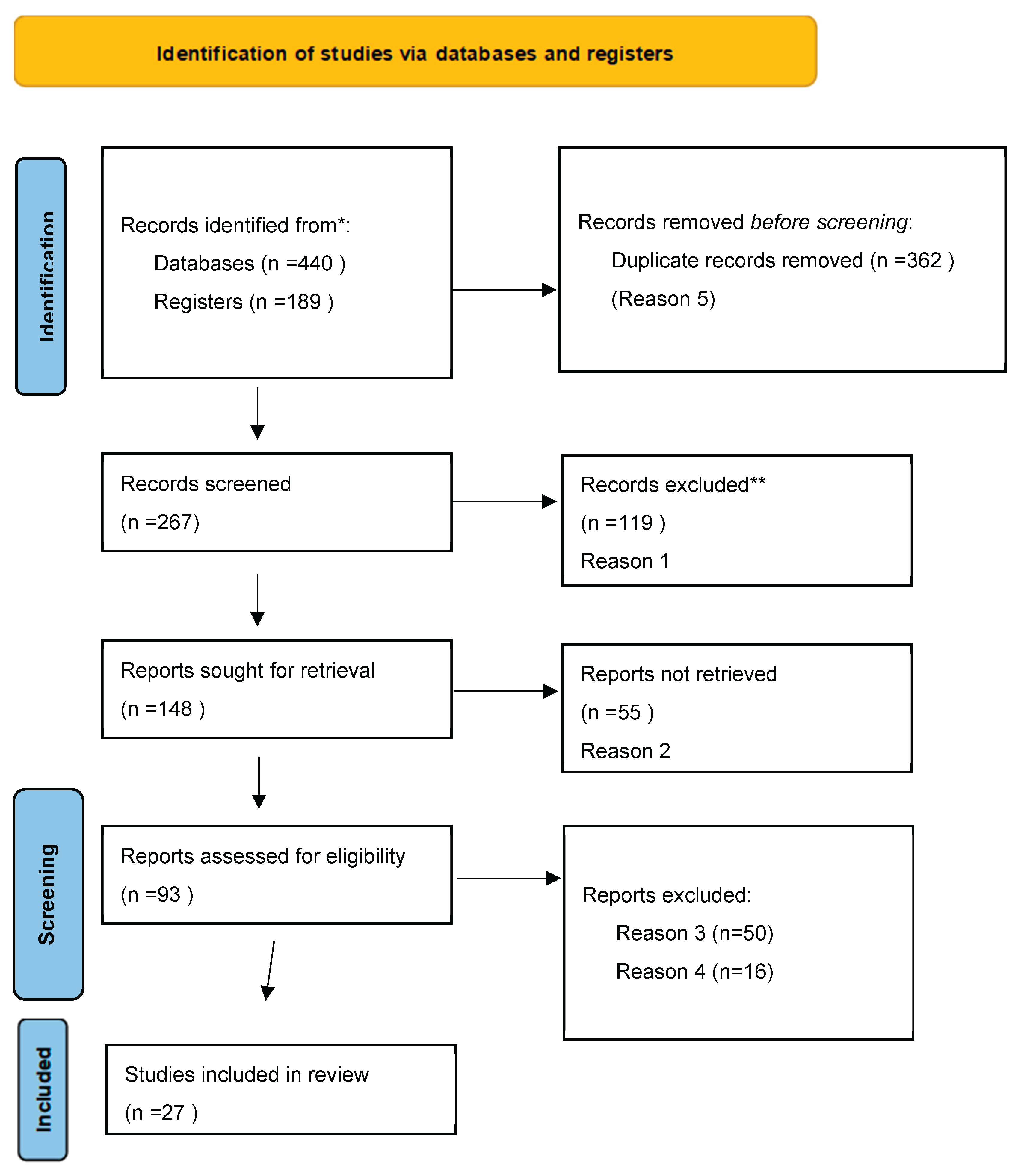

Flowchart and Study Selection Process

3. Results

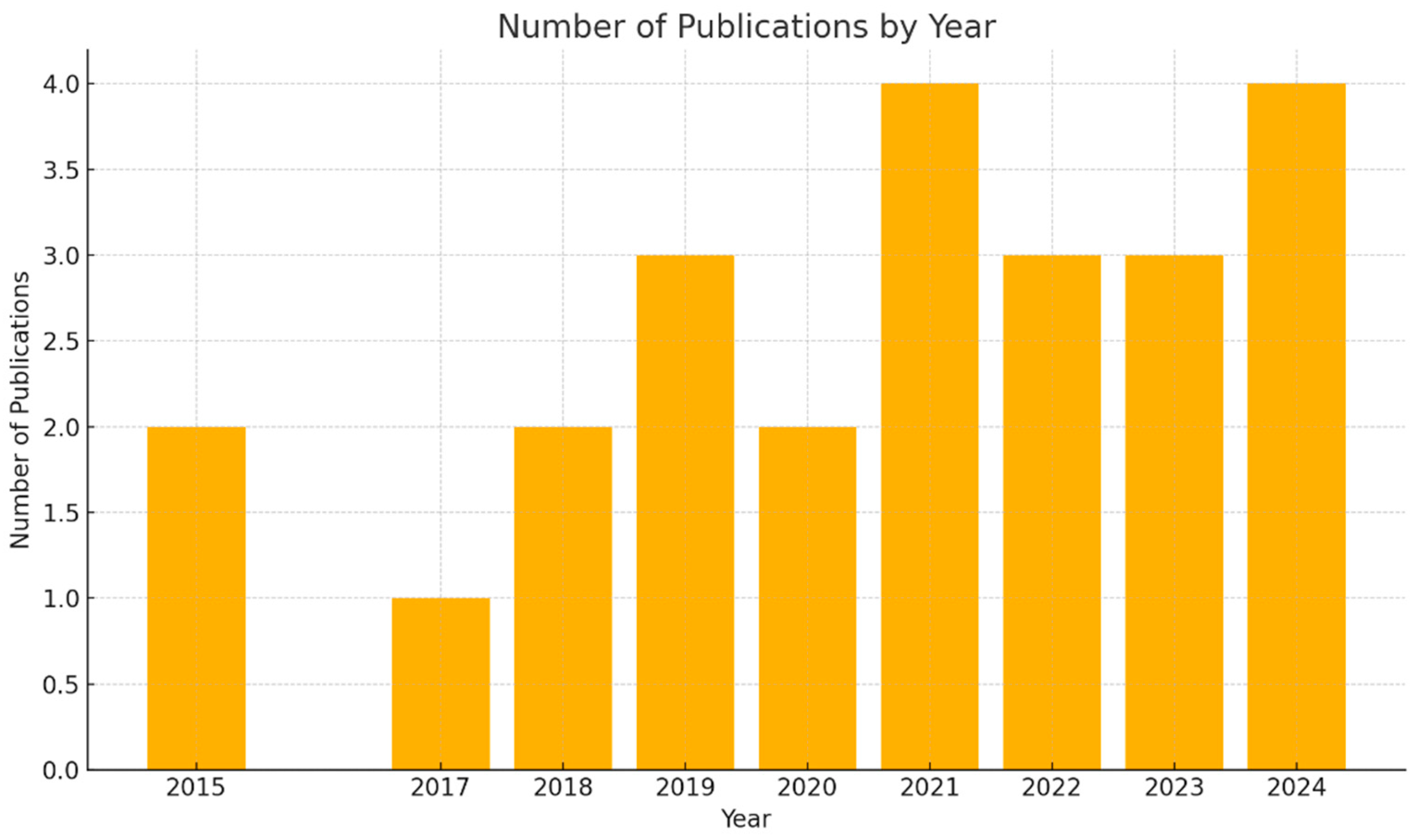

Type of Study and Study Design

Population and Sample Size

Data Collection Methods

Statistical Methodology, Analyses, and Recommendations

Limitations Reported

Comparative and Cross-Cultural Analysis

Overall Implications

4. Discussion

Current Gaps in Nutrition Education Among Clinicians

Proposed Competency-Based Curriculum

Interprofessional Coordination and Collaboration

Institutional and Policy Recommendations

Role of National Coordination Centers

Enhancing Dentists’ Own Oral Health Through Integrated Nutrition Education and Practice

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaman, G. B., & Hocaoğlu, Ç. (2022). Examination of eating and nutritional habits in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrition, 105, 111839. [CrossRef]

- Slavkin HC, Dubois PA, Kleinman DV, Fuccillo R. Science-Informed Health Policies for Oral and Systemic Health. J Healthc Leadersh. 2023 Mar 16;15:43-57. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A., Bak, M., Mahoney, C., Hoyle, L., Kelly, M., Atherton, I. M., & Kyle, R. G. (2019). Health-related behaviours of nurses and other healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional study using the Scottish Health Survey. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(6), 1239–1251. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Varzakas, T. Diet and Oral Health Coaching Methods and Models for the Independent Elderly. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills A, Berlin-Broner Y, Levin L. Improving Patient Well-Being as a Broader Perspective in Dentistry. Int Dent J. 2023 Dec;73(6):785-792. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gaffar, B., Farooqi, F. A., Nazir, M. A., Bakhurji, E., Al-Khalifa, K. S., Alhareky, M., & Virtanen, J. I. (2022). Oral health-related interdisciplinary practices among healthcare professionals in Saudi Arabia: Does integrated care exist? BMC Oral Health, 22(1), 75. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A., Eyler, A., Cesarone, G., Harris, J., Hayibor, L., & Evanoff, B. (2023). Exploring university and healthcare workers’ physical activity, diet, and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open Medicine, 11, 21650799221147814. [CrossRef]

- Tantimahanon, A., Sipiyaruk, K., & Tantipoj, C. (2024). Determinants of dietary behaviors among dental professionals: Insights across educational levels. BMC Oral Health, 24, Article 724. [CrossRef]

- Canuto, R., Garcez, A., Spritzer, P. M., & Olinto, M. T. A. (2021). Associations of perceived stress and salivary cortisol with the snack and fast-food dietary pattern in women shift workers. Stress, 24(6), 763–771. [CrossRef]

- Abouelezz, N. F., Ahmed, W. S. E., Elhussieny, D. M., Ahmed, G. S., & Zaky, M. S. M. E. (2024). Dietary habits and perceived barriers of healthy eating among healthcare workers in a tertiary hospital in Egypt: A cross-sectional study. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 117(Supplement_2), hcae175.884. [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkawy, A. M., Bragg, D., Watson, P., Neal, K., Sahota, O., Maughan, R. J., & Lobo, D. N. (2016). Hydration amongst nurses and doctors on-call (the HANDS on prospective cohort study). Clinical Nutrition, 35(4), 935–942. [CrossRef]

- Utter J, McCray S, Denny S. Eating Behaviours Among Healthcare Workers and Their Relationships With Work-Related Burnout. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2023;0(0). [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulou, M., Antoniadou, M., Amargianitakis, M., Gortzi, O., Androutsos, O., & Varzakas, T. (2023). Nutritional factors associated with dental caries across the lifespan: A review. Applied Sciences, 13(24), 13254. [CrossRef]

- Tohary, I. A., Jan, A. S., Alotaibi, M. A., Alosaimi, T. B., Alotaibi, A. E. A., Alshayb, A. A., Sadig, J. A. A., Tumayhi, H. Y. A., Rubayyi, S. H., Amri, S. A., & Almutairi, H. T. (2022). The impact of diet and nutrition on oral health: A systematic review. Migration Letters, 19(S5), 338–346. https://www.migrationletters.com.

- Crespo-Escobar, P., Vázquez-Polo, M., van der Hofstadt, M., Nuñez, C., Montoro-Huguet, M. A., Churruca, I., & Simón, E. (2024). Knowledge gaps in gluten-free diet awareness among patients and healthcare professionals: A call for enhanced nutritional education. Nutrients, 16(15), 2512. [CrossRef]

- Lieffers, J. R., Vanzan, A. G. T., & de Mello, J. R. (2021). Nutrition care practices of dietitians and oral health professionals for oral health conditions: A scoping review. Nutrients, 13(10), 3588. [CrossRef]

- Thircuir, S., Chen, N. N., & Madsen, K. A. (2023). Addressing the gap of nutrition in medical education: Experiences and expectations of medical students and residents in France and the United States. Nutrients, 15(24), 5054. [CrossRef]

- Lahiouel, A., Kellett, J., Isbel, S., & D’Cunha, N. M. (2023). An exploratory study of nutrition knowledge and challenges faced by informal carers of community-dwelling people with dementia: Online survey and thematic analysis. Geriatrics (Basel), 8(4), 77. [CrossRef]

- Hobby, J., Parkinson, J., & Ball, L. (2024). Exploring health professionals’ perceptions of how their own diet influences their self-efficacy in providing nutrition care. Psychology & Health, 39(2), 252–267. [CrossRef]

- Torquati, L., Pavey, T., Kolbe-Alexander, T., & Leveritt, M. (2017). Promoting diet and physical activity in nurses. American Journal of Health Promotion, 31(1), 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W., Waqas, A., Saleem, H. A., & Naveed, S. (2017). Exploring diet, exercise, chronic illnesses, occupational stressors and mental well-being of healthcare professionals in Punjab, Pakistan. BMC Research Notes, 10(1), 745. [CrossRef]

- Chui, H., Bryant, E., Sarabia, C., Maskeen, S., & Stewart-Knox, B. (2019). Burnout, eating behaviour traits and dietary patterns. British Food Journal. [CrossRef]

- Sert, E., & Kendirkiran, G. (2024). Effects of emotional eating behaviour and burnout levels of nurses on job performance: A cross-sectional descriptive study. SAGE Open Nursing. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Hulsegge, G., Boer, J. M., van der Beek, A. J., Verschuren, W. M., Sluijs, I., Vermeulen, R., & Proper, K. I. (2016). Shift workers have a similar diet quality but higher energy intake than day workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 42(6), 459–468. [CrossRef]

- Bouillon-Minois, J.-B., Thivel, D., Croizier, C., Ajebo, É., Cambier, S., Boudet, G., Adeyemi, O. J., Ugbolue, U. C., Bagheri, R., Vallet, G. T., Schmidt, J., Trousselard, M., & Dutheil, F. (2022). The negative impact of night shifts on diet in emergency healthcare workers. Nutrients, 14(4), 829. [CrossRef]

- Tejoyuwono, A. (2020). Health lecturers and students’ views about healthcare workers as healthy lifestyle role models: A qualitative study. Indonesian Journal of Nursing Practices, 4, Article 1105. [CrossRef]

- Torquati, L., Pavey, T., & Leveritt, M. (2017). Promoting diet and physical activity in nurses: A systematic review. American Journal of Health Promotion, 31(1), 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Schiavo, J. H. (2019). PROSPERO: An international register of systematic review protocols. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 38(2), 171-180. [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2022). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. IBM Corp.

- Mamun, A.A.; Mahmudiono, T.; Yudhastuti, R.; Triatmaja, N.T.; Chen, H.-L. Effectiveness of Food-Based Intervention to Improve the Linear Growth of Children under Five: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Znyk, M., & Kaleta, D. (2024). Unhealthy eating habits and determinants of diet quality in primary healthcare professionals in Poland: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients, 16(19), Article 3367. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Xu, X., Liu, Y., Yao, Y., Zhang, P., Liu, J., Zhang, Q., Li, R., Li, H., Liu, Y., & Chen, W. (2023). Association of eating habits with health perception and diseases among Chinese physicians: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10. [CrossRef]

- Wolska, A., Stasiewicz, B., Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K., Ziętek, M., Solek-Pastuszka, J., Drozd, A., Palma, J., & Stachowska, E. (2022). Unhealthy food choices among healthcare shift workers: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients, 14(20), Article 4327. [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, A., Mehrotra, A., Babu, A. K., Ji, P., Mapare, S. A., & Pawar, R. O. (2021). Oral health knowledge, attitude, and practices among healthcare professionals: A questionnaire-based survey. Journal of Pharmacy & BioAllied Sciences, 13(Suppl 2), S1452–S1457. [CrossRef]

- Mota, I. A., de Oliveira Sobrinho, G. D., Morais, I. P. S., & Dantas, T. F. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on eating habits, physical activity, and sleep in Brazilian healthcare professionals. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 79(5), [page numbers if available]. [CrossRef]

- Portero de la Cruz, S., Cebrino, J., Herruzo, J., & Vaquero-Abellán, M. (2020). A multicenter study into burnout, perceived stress, job satisfaction, coping strategies, and general health among emergency department nursing staff. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(4), 1007. [CrossRef]

- Souza, R. V., Sarmento, R. A., de Almeida, J. C., & Canuto, R. (2018). The effect of shift work on eating habits: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 45(1). [CrossRef]

- Almoteb, M. M., Alalyani, S. S., Gowdar, I. M., Penumatsa, N. V., Siddiqui, M. A. M., & Sharanesha, R. B. (2019). Oral hygiene status and practices among healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study. Journal of International Oral Health, 11(5), 268–273. [CrossRef]

- Van Horn L, Lenders CM, Pratt CA, Beech B, Carney PA, Dietz W, DiMaria-Ghalili R, Harlan T, Hash R, Kohlmeier M, Kolasa K, Krebs NF, Kushner RF, Lieh-Lai M, Lindsley J, Meacham S, Nicastro H, Nowson C, Palmer C, Paniagua M, Philips E, Ray S, Rose S, Salive M, Schofield M, Thompson K, Trilk JL, Twillman G, White JD, Zappalà G, Vargas A, Lynch C. Advancing Nutrition Education, Training, and Research for Medical Students, Residents, Fellows, Attending Physicians, and Other Clinicians: Building Competencies and Interdisciplinary Coordination. Adv Nutr. 2019 Nov 1;10(6):1181-1200. [CrossRef]

- Touger-Decker, Riva et al.Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Oral Health and Nutrition. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Volume 113, Issue 5, 693 – 701.

- Ab-Murat, N., Mason, L., Abdul Kadir, R., & Yusoff, N. (2018). Self-perceived mental well-being amongst Malaysian dentists. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 24(2), 233–239. [CrossRef]

- Orgel, R., & Cavender, M. A. (2018). Healthy living for healthcare workers: It is time to set an example. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 25(5), 485–487. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W., Taggart, F., Shafique, M. S., Muzafar, Y., Abidi, S., Ghani, N., Malik, Z., Zahid, T., Waqas, A., & Ghaffar, N. (2015). Diet, exercise and mental-wellbeing of healthcare professionals (doctors, dentists and nurses) in Pakistan. PeerJ, 3, e1250. [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A., Ahmad, W., Haddad, M., Taggart, F. M., Muhammad, Z., Bukhari, M. H., Sami, S. A., Batool, S. M., Najeeb, F., Hanif, A., Rizvi, Z. A., & Ejaz, S. (2015). Measuring the well-being of healthcare professionals in the Punjab: A psychometric evaluation of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale in a Pakistani population. PeerJ, 3, e1264. [CrossRef]

- Taylor M. Oral health and nutrition guidance for professionals June 2012. Accessed on 21 June from https://www.scottishdental.nhs.scot/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/OralHealthAndNutritionGuidance.pdf.

- Shmarina, E., Ericson, D., Götrick, B. et al. Dental professionals’ perception of their role in the practice of oral health promotion: a qualitative interview study. BMC Oral Health 23, 43 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Escoto KH, Laska MN, Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ. Work hours and perceived time barriers to healthful eating among young adults. Am J Health Behav. 2012 Nov;36(6):786-96. [CrossRef]

- WHO Technical Report Series, 916. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Accessed on 21 june from https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42665/WHO_TRS_916.pdf.

- Wilson T, Temple NJ, Bray GA. Nutrition Guide for Physicians and Related Healthcare Professions. Nutrition and Health (NH) series. Springer nature link.2022.

- Public health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention Third edition, 2017. Accessed on 21 june from https://www.bsperio.org.uk/assets/downloads/Delivering_better_oral_health.pdf.

- Kaye J, Lee S, Chinn CH. The need for effective interprofessional collaboration between nutrition and dentistry. Front Public Health. 2025 Feb 26;13:1534525. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka M, Adam LA, Ball LE, Crowley J, McLean RM. Nutrition Education and Practice in University Dental and Oral Health Programmes and Curricula: A Scoping Review. Eur J Dent Educ. 2025, 29(1), 64-83. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Mangoulia, P.; Myrianthefs, P. Quality of Life and Wellbeing Parameters of Academic Dental and Nursing Personnel vs. Quality of Services. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández CE, Torre MJ, Vargas CJ, Aravena CA, Santander J, Marshall TA. Diet and Nutrition Integration in Dental Education: A Scoping Review. Eur J Dent Educ. 2025 Jun 5. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg DM, Cole A, Maile EJ, et al. Proposed Nutrition Competencies for Medical Students and Physician Trainees: A Consensus Statement. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(9):e2435425. [CrossRef]

- 56. CareQuest Institute for Oral Health. Transforming Oral Health Care Through Interprofessional Education: Use Cases. Boston, MA: April 2025. accessed 21 june from https://www.carequest.org/system/files/CareQuest_Institute_IPE-UseCases_4.1.25_Final.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou M, Varzakas T. Breaking the vicious circle of diet, malnutrition and oral health for the independent elderly. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021, 61(19), 3233-3255. [CrossRef]

- Ehsan F, Iqbal S, Younis MA, Khalid M. An educational intervention to enhance self-care practices among 1st year dental students- a mixed method study design. BMC Med Educ. 2024, 14, 24(1):1304. [CrossRef]

- Noorullah K, Oshita SE, McNeil AT, Ijaz A, Iqbal L, Tomar SL, Smith PD, Bilal S. Bridging Nutrition and Dentistry: An Interprofessional Education (IPE) Experience Model. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2025 May 31;18:3039-3049. [CrossRef]

- Boak R, Palermo C, Beck EJ, Pelly F, Wall C, Gallegos D. Five Actions to Strengthen the Nutrition and Dietetics Profession Into the Future: Perspectives From Australia and New Zealand. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2025 Jun;38(3):e70064. [CrossRef]

- Bendowska A, Baum E. The Significance of Cooperation in Interdisciplinary Health Care Teams as Perceived by Polish Medical Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023, 5, 20(2):954. [CrossRef]

- Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS, Benishek LE, Thompson D, Pronovost PJ, Weaver SJ. Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am Psychol. 2018 May-Jun;73(4):433-450. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, M. Closing the gap between medical knowledge and patient outcomes through new training infrastacture. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2023, 133, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DiMaria-Ghalili RA, Mirtallo JM, Tobin BW, Hark L, Van Horn L, Palmer CA. Challenges and opportunities for nutrition education and training in the health care professions: intraprofessional and interprofessional call to action. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014, 99(5 Suppl):1184S-93S. [CrossRef]

- Forsetlund L, O’Brien MA, Forsén L, Reinar LM, Okwen MP, Horsley T, Rose CJ. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021, 15;9(9):CD003030. [CrossRef]

- Nasseripour, M.; Agouropoulos, A.; Van Harten, M.T.; Correia, M.; Sabri, N.; Rollman, A. Current State of Professionalism Curriculum in Oral Health Education. Eur J Dent Educ. 2025, 29(1), 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyemienbai, E.J.; Logue, D.; McMonagle, G.; Doherty, R.; Ryan, L.; Keaver, L. Enhancing Nutrition Care in Primary Healthcare: Exploring Practices, Barriers, and Multidisciplinary Solutions in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemiparast M, Negarandeh R, Theofanidis D. Exploring the barriers of utilizing theoretical knowledge in clinical settings: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019, 12, 6(4):399-405. [CrossRef]

- Ejiohuo O, Onyeaka H, Unegbu KC, Chikezie OG, Odeyemi OA, Lawal A, Odeyemi OA. Nourishing the Mind: How Food Security Influences Mental Wellbeing. Nutrients. 2024 Feb 9;16(4):501. [CrossRef]

- Re B, Alessandro Zardini, Francesca Sanguineti, Pietro Previtali. Healthy eating initiatives in the workplace: a configurational approach. https://www.emerald.com/insight/0007-070X.htm Accessed on 21 june from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/bfj-10-2024-1080/full/pdf.

- Abo-Khalil, AG. Integrating sustainability into higher education challenges and opportunities for universities worldwide. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollaar, V.R.Y.; Naumann, E.; Haverkort, E.B.; Jerković-Ćosić, K.; Kok, W.E.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E. Success factors and barriers in interprofessional collaboration between dental hygienists and dietitians in community-dwelling older people: Focus group interviews. international journal of dental hygiene. 2023, 22, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadou, M.; Antoniadis, R. A Systemic Model for Resilience and Time Management in Healthcare Academia: Application in a Dental University Setting. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P. M., Petersen, K. S., Hibbeln, J. R., Hurley, D., Kolick, V., Peoples, S., Rodriguez, N., & Woodward-Lopez, G. (2021). Nutrition and behavioral health disorders: Depression and anxiety. Nutrition Reviews, 79(3), 247–260. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care; Robinson SK, Meisnere M, Phillips RL Jr., et al., editors. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2021 May 4. 6, Designing Interprofessional Teams and Preparing the Future Primary Care Workforce. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK571818/.

- Μangoulia, P.; Kanellopoulou, A.; Manta, G.; Chrysochoou, G.; Dimitriou, E.; Kalogerakou, T.; Antoniadou, M. Exploring the Levels of Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Resilience, Hope, and Spiritual Well-Being Among Greek Dentistry and Nursing Students in Response to Academic Responsibilities Two Years After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2025, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsahoryi NA, Ghada A. Maghaireh, Fwziah Jammal Hammad. Understanding dental caries in adults: A cross-sectional examination of risk factors and dietary behaviors. Clinical Nutrition Open Science, 2024, 57, 163-176. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Leadership and Managerial Skills in Dentistry: Characteristics and Challenges Based on a Preliminary Case Study. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research(US); 2021 Dec. Section 4, Oral Health Workforce, Education, Practice and Integration. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578298/.

- Varzakas, T.; Antoniadou, M. A Holistic Approach for Ethics and Sustainability in the Food Chain: The Gateway to Oral and Systemic Health. Foods 2024, 13, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornman, J.; Louw, B. Leadership Development Strategies in Interprofessional Healthcare Collaboration: A Rapid Review. J Healthc Leadersh. 2023, 23, 15:175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadou, M. Quality of Life and Satisfaction from Career and Work–Life Integration of Greek Dentists before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, M., Urquhart, O., Bhosale, A.S. et al. A unified voice to drive global improvements in oral health. BMC Global Public Health 2023, 1, 19. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Prevention and Treatment of Dental Caries with Mercury-Free Products and Minimal Intervention: WHO Oral Health Briefing Note Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogerakou, T, Antoniadou, M. The role of dietary antioxidants, food supplements, and functional foods for energy enhancement in healthcare professionals. Antioxidants, 2024, 13(12), 1508. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030; Regional summary of the African Region; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sarris, J., Logan, A. C., Akbaraly, T. N., Amminger, G. P., Balanzá-Martínez, V., Freeman, M. P., Hibbeln, J., Matsuoka, Y., Mischoulon, D., Mizoue, T., Nanri, A., Nishi, D., Ramsey, D., Rucklidge, J. J., Sanchez-Villegas, A., Scholey, A., Su, K.-P., Jacka, F. N., & International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2015, 2(3), 271–274. [CrossRef]

- Gondivkar, S. M., Gadbail, A. R., Gondivkar, R. S., Sarode, S. C., Sarode, G. S., Patil, S., Awan, K. H. Nutrition and oral health. Disease-a-Month, 2019, 65(6), 147–154. [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, A., Nolen-Doerr, E., Mantzoros, C. S. The effect of the Mediterranean diet on metabolic health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials in adults. Nutrients, 2020, 12(11), 3342. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Quality of Life and Satisfaction from Career and Work–Life Integration of Greek Dentists before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadou, M. Estimation of Factors Affecting Burnout in Greek Dentists before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, K. P., Ezerins, M. E., Rosen, C. C., Gabriel, A. S., Patel, C., Lim, G. J. H. Socioeconomic Status and Employee Well-Being: An Intersectional and Resource-Based View of Health Inequalities at Work. Journal of Management, 2025, 51(6), 2549-2588. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Type of study- Single/multi center | Population | Exposure | Comparators | Funding and Confilct | statistical significance | Limitations | Ethics approval | Sample calulation | Confounders | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Tantimahanon et al., (2024), [8]. |

Cross-sectional (multi-center) | Dental professionals (UG, PG, DT; n=842) | Dietary behaviors | Knowledge, attitude, alcohol consumption | No conflicts mentioned; funded by Mahidol University | Significant correlation (P < 0.001 for all groups) | Self-reported survey may lead to response bias. Age range primarily under 30, limiting generalizability. | Approved by Mahidol University IRB (MU-DT/PY-IRB 2023/004.1701) | Calculated using formula for finite population (CI 95%, margin error 6%) | Stress, socioeconomic factors, living environment | Attitude was the strongest determinant. Alcohol consumption negatively associated with healthy behaviors. |

| 2. Crespo-Escobar et al. (2024)[15] | Cross-sectional, multi-center | CeD patients (n=2,437); HCPs (n=346); Relatives (n=1,294) | Knowledge and adherence to GFD | Knowledge gaps in GFD; adherence in CeD | Not disclosed | Significant differences in knowledge sources and quality of GFD information provision (p < 0.05) | Self-report bias; focus on Spain; overrepresentation of association members; limited dietitian availability in public healthcare; cultural specificity of findings. | Approved by the Ethics Committee of UPV/EHU | Sampling via snowball method, no formal sample calculation. | Sociodemographic data, professional role, patient association membership | Knowledge gaps in GFD adherence among CeD patients and HCPs; limited time in consultations; reliance on unreliable sources (e.g., Internet). |

| 3.Hobby et al. (2024)[19]. | Cross-sectional qualitative design | 22 health professionals (including dietitians) | Perceptions of how personal diet influences self-efficacy in providing nutrition care | Not applicable | Not reported | Not applicable | Small sample size; findings may not be generalizable due to recruitment through media channels; self-reported data may introduce bias | Approved | Not applicable | Social environment, personal experiences | Health professionals perceive personal dietary habits strongly influence their self-efficacy in providing nutrition care. Strategies supporting healthier diets may enhance care quality. |

| 4.Znyk & Kaleta (2024)[31]. | Cross-sectional study | 161 doctors and 331 nurses in Poland | Eating habits and diet quality during shifts | General population; different work conditions | Not reported | Univariate logistic regression showed significant determinants of diet (p < 0.05) | Self-reported data may introduce recall bias; cross-sectional design; no questions about income; small sample size; conducted during COVID-19 pandemic, potentially affecting habits. | Approved | Not applicable | Work experience, number of patients, BMI, smoking | Unhealthy eating habits affected 25.8% of healthcare workers, linked to smoking, work experience, and patient load. Nurses exhibited higher prevalence of unhealthy habits. |

| 5.Dimopoulou et al (2023)[13] | Narrative review (single centralized author group, not empirical; no study centers) | General human populations across lifespan (children to older adults), aggregated from various studies | Nutritional factors: dietary sugar, frequency of intake, macro/micronutrient patterns linked to dental caries | Varied across included studies (e.g., high vs. low sugar intake; frequent vs. infrequent snacking; nutrient-rich vs. nutrient-poor diets) | Not reported in article; no conflicts declared | Not applicable (review synthesis; no original hypothesis testing) | Heterogeneity of included studies (designs, populations, methods) - Potential publication bias - Narrative synthesis (no meta-analysis) - Quality and validity of primary studies vary |

Not applicable (literature review; no new human or animal research) | Not applicable | Confounders reported variably in included studies (e.g., socioeconomic status, oral hygiene, fluoride exposure), but no uniform adjustment in this review | Associations between nutrition-related variables (sugar intake, snacking frequency, nutrient deficiencies) and dental caries incidence across age groups |

| 6.Chen et al. (2023) [32] | Cross-sectional study | In-service physicians in mainland China | Eating habits (e.g., eating out, irregular meals, eating too fast) | Physicians with healthier eating habits | Not reported | Significant associations between unhealthy eating habits and suboptimal health/disease occurrence (p < 0.05) | Convenience sampling; self-reported data may introduce recall bias; cross-sectional design limits causal inference. | Approved | Not applicable | Sociodemographic characteristics, BMI classification | High prevalence of unhealthy eating habits linked to increased rates of suboptimal health, obesity, and metabolic diseases among physicians. Eating too fast and eating out were common. |

| 7.Utter et al. (2023)[12] | Cross-sectional study, single center (large healthcare organization in South-East Queensland, Australia) | 501 healthcare workers (varied roles) | Dietary behaviors (overall diet quality, fruit/vegetable intake, family shared meals) | Different levels of dietary indicators (e.g., high vs low diet quality) | Not specified | Significant inverse relationship: healthier diet associated with lower burnout (adjusted for covariates) | Cross-sectional design (no causality); self-reported data; single site; no sample size calculation reported | Not explicitly stated (likely approved by institutional ethics board) | Not reported | Age, gender, role, employment level | Burnout levels; dietary behavior indicators |

| 8.Sert & Kendirkiran (2023) [23] | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 255 nurses working in Istanbul | Emotional eating behavior, burnout levels, and their effect on job performance | Nurses with different experience levels and job satisfaction levels | Not reported | Significant positive relationship between burnout, emotional eating, and job performance | Small sample size; single hospital study may not generalize findings; self-reported scales may introduce bias | Approved | Not detailed | Work environment factors, job satisfaction, and intensive care exposure | Burnout and emotional eating behavior negatively affect job performance. Recommendations include stress management training, psychiatric support, and organizational changes to improve nurses’ emotional and physical well-being. |

| 9.Gilbert et al. (2023) [7] | Observational (multi-wave) | University and medical center staff (n=1,994 wave 1; 1,426 wave 2; 1,363 wave 3) | Physical activity and diet during COVID-19 | Mental well-being, depression, anxiety, stress | Not specified | Maintained or increased physical activity and a healthy diet were significantly associated with reduced risk of worse mental health outcomes (ORs 0.44–0.76). | Self-reported data, potential recall bias, no pre-pandemic data, generalizability limited to one employer. | Approved by Washington University IRB | No specific sample calculation described; participation across three waves | Clinical role, age, gender, race, income, ethnicity | Maintaining/increasing PA and diet correlated with better mental health outcomes (e.g., reduced anxiety, stress). |

| 10.Tohary et al. (2022), [14] | Systematic review | Various studies on oral health | Diet and nutrition’s impact on oral health | Sugary diets, processed foods, nutrient-rich diets | Not specified | Not applicable | Relied on secondary data, potential biases in source studies, observational nature of included research | Not applicable | No specific sample calculation described. | Various dietary patterns and nutrient deficiencies | A balanced diet with essential nutrients supports oral health. High sugar and processed food consumption linked to oral diseases like caries. |

| 11.Bouillon-Minois et al. (2022),[25] | Prospective observational | 184 emergency HCWs | Night shifts on food and water intake | Day shifts as baseline | Not stated | Calorie intake decreased by 206 kcal (p=0.049) and water consumption by 243 mL (p=0.010). | Small sample size, limited to emergency HCWs; self-reported food intake data; no long-term follow-up | Yes | Not reported | Time of day, shift duration | Night shifts reduced caloric intake by 14.7%, water consumption by 16.7%, carbohydrates by 8.7%, proteins by 17.6%, and lipids by 18.7%; increased periods without eating or drinking. |

| 12.Wolska et al. (2022)[33] | Cross-sectional study | 445 healthcare workers | Shift work and dietary patterns | Daily work | Not reported | Significant differences in dietary patterns and fat intake among shift workers (p < 0.05) | Regional sample; self-reported dietary data using FFQ; cross-sectional design limits causal relationships | Approved | Not applicable | Mealtime consistency, Polish-aMED® score, dietary fat intake | Shift workers showed 2x higher odds of adherence to ‘Meat/fats/alcohol/fish’ pattern; lower adherence to ‘Pro-healthy’ dietary patterns and consistency in mealtime; higher fat intake. |

| 13.Mehrotra et al. (2021)[34] | Cross-sectional survey | 473 HCWs (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, interns, technicians) | Oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices | Comparison across HCW categories | Not stated | Significant differences in oral health knowledge among HCW categories (P < 0.05) | Self-reported data; limited sample size; cross-sectional design | Yes | Not applicable | Demographics, profession, gender | Positive attitude towards professional dental care across all HCWs; significant variation in knowledge and practices based on profession. |

| 14.Mota et al. (2021, Brazil)[35] | Cross-sectional study | 710 Brazilian HCWs (predominantly women, aged 30-40, mostly physicians) | Impact of COVID-19 on eating habits, physical activity, and sleep | General population data for comparison | Not stated | Significant changes in sleep, diet, and physical activity patterns among HCWs | Self-reported data; potential recall bias; limited generalizability to HCWs outside Brazil | Yes | Not reported | Gender, age, professional role | Sleep-related complaints (66%); increase in carbohydrate and alcohol intake (24.5% and 27%, respectively); reduced physical activity (81.8%); self-medication for insomnia (60.3%). |

| 15.Lieffers et al., (2021),[16] | Scoping Review | Oral health professionals and dietitians in high-income countries | Nutrition care practices for oral health conditions | Nutrition care practices for oral health conditions | No conflicts reported, various funding sources | Not applicable | Limited data on dietitians; lack of detail on care provided; language restrictions (English only) | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Identified gaps in literature; recommendations for future research on collaboration and practices |

| 16.Portero de la Cruz et al. (2020))[36] | Cross-sectional study | 171 emergency nurses | Burnout, perceived stress, diet, job satisfaction | Not applicable | No conflict of interest | Lack of physical exercise, gender, and years worked were significant predictors of burnout | Single region; potential reporting bias due to self-reported measures; cross-sectional design limits causal inference | Approved | Not applicable | Gender, years of experience, coping strategies, anxiety | Prevalence of high burnout: 8.19%. Moderate perceived stress and job satisfaction; frequent social dysfunction and somatic symptoms; problem-focused coping is commonly used. |

| 17.Souza et al. (2019)[37] | Systematic review | 33 observational studies | Shift work and its impact on eating habits | Day workers or other non-shift workers | Not reported | High risk of bias in most studies reviewed | Quality scores <70%; high bias in comparability, sample selection, and non-response; limited longitudinal data | Not applicable | Not applicable | Time of exposure, duration of workday, sleep patterns | Shift work is associated with irregular meal patterns, meal skipping, and increased consumption of unhealthy foods like saturated fats and soft drinks. Longitudinal studies are needed for causal inferences. |

| 18.Schneider et al. (2019)[3] | Secondary analysis of cross-sectional data | 18,820 participants (471 nurses, 433 healthcare professionals, 813 care workers, 17,103 non-healthcare workers) | Health-related behaviours: smoking, alcohol, physical activity, fruit/vegetable intake | General working population in Scotland | Not reported | Significant differences found in smoking, physical activity, and fruit/vegetable intake; no significant differences in alcohol consumption | Small sample size for certain subgroups (e.g., nurses); self-reported behaviours may introduce bias | Not reported | Not reported | Age, occupation group | Nurses reported better health-related behaviours (except alcohol consumption) compared to the general population. Other healthcare professionals exhibited the best behaviours overall. |

| 19.Almoteb et al. (2019)[38] | Cross-sectional study | 431 HCWs (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, technicians) | Oral hygiene status, practices, and knowledge | Comparison of doctors vs. others | Not stated | Significant differences in oral hygiene practices among HCWs (P < 0.05) | Limited to one hospital; cross-sectional design; lack of WHO oral hygiene pro forma | Yes (PSAU/CDS/430400428/2016) | Based on formula | Age, gender, profession | Fair oral hygiene status observed; doctors demonstrated better interdental aid usage; need for improved oral health education and integration into medical training. |

| 20. Van Horn et al 2019[39] | Expert workshop–based position/report; synthesizes existing education initiatives; multi-institutional/disciplinary representation | Medical students, residents, fellows, attending physicians, and other clinicians in the U.S. (and collaborators internationally) | Nutrition education frameworks, competency-based curriculum, interprofessional coordination | Pre-workshop baseline of medical nutrition training vs. proposed competency-based updates; integrated models vs. traditional curricula | Supported by NIH (NHLBI, Office of Dietary Supplements, Office of Disease Prevention) and American Society for Nutrition; | Not applicable (informal consensus report; no primary data testing) | Not empirical; consensus may reflect workshop attendees’ views; lacks direct outcome data; U.S.-centric; potential bias from funding stakeholders | Not required for workshop synthesis | Not applicable | Not applicable (conceptual framework rather than an experimental design) | Recommendations/frameworks: competency-based nutrition education, national coordination center, interprofessional collaboration models, accreditation integration |

| 21. Touger-Decker et al (2019) [40] | Practice guideline/position paper (single committee-authored; not empirical research) | Dietitians, nutritionists, and oral health professionals—recommendation target; broader public indirectly | Integration of nutrition and oral health—screening, education, referrals, medical nutrition therapy | Best-practice integrated nutrition–oral health services vs. non-integrated or standard care | Endorsed and published by Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/Elsevier; no industry funding or conflicts disclosed | Not applicable (consensus guideline; no original data or statistical testing) | Position based on existing literature and expert consensus; may be influenced by publication bias; not a systematic review | Not required (non-research guideline development) | Not applicable | Not applicable (guideline synthesis, not primary research) | Recommendations for joint nutrition–oral health care practices, education, interprofessional collaboration, and research integration |

| 22.Ab-Murat et al., (2018)[41] | Cross-sectional survey | Malaysian dentists (81% response rate) | Mental well-being assessed through self-administered questionnaire using a conceptual framework | Not disclosed | - Positive mental well-being higher in those >40 years, married, and with children (P < 0.05) | ~2.5 (as of publication year) | Limited to Malaysian dentists - Self-reported data may introduce bias - No detailed funding disclosure - Lacks longitudinal analysis |

Approved, details not specified | Sample size not explicitly calculated | Age, marital status, parental status | - 61.7% reported positive mental well-being |

| 23.Orgel & Cavender (2018)[42] | Editorial commentary on survey | 1158 NHS staff | Lifestyle and cardiovascular health | General population benchmarks | Not stated | Rates of healthy diet and physical activity marginally better than public; significant room for improvement | Low response rate (13%); self-reported data; focus on cross-sectional findings | Not applicable | Not applicable | Fatigue, workplace environment | Poor diet (1 in 6 met recommendations; 5 in 6 consumed high sugar/fat), low physical activity (50%), and workplace barriers hinder health. Recommendations: subsidized healthy food, gym access, and behavioral counseling to improve HCWs’ health and reduce public risks. |

| 24.Torquati et al. (2017)[27] | Systematic review | Nurses/student nurses in healthcare | Interventions promoting diet and PA | Nurses with no or standard PA/diet interventions | Not reported | Promising but inconsistent effects on PA and diet outcomes in nurses. | Small sample sizes; low to moderate study quality; limited measurement of dietary outcomes; lack of objective measures. | Not applicable | Not applicable | Participant motivation, baseline health behaviors | Positive outcomes in PA (structured exercise, goal setting); dietary changes reported in few studies. Improved body composition in two studies without significant diet/PA changes. |

| 25.Ahmad et al. (2015)[43] | Cross-sectional | Healthcare professionals (N = 1,190; doctors, nurses, dentists in Punjab, Pakistan) | Dietary habits, exercise, mental well-being | Comparison with recommended guidelines (USDA, AHA, WEMWBS) | Not disclosed | Significant associations for diet, exercise, and mental well-being factors (p < 0.05) | Convenience sampling, limited to Punjab, Pakistan; self-reported BMI; no occupational stress scale; reliance on non-local guidelines (USDA); underrepresentation of dentists | Approved by CMH Lahore Medical and Dental College Ethical Review Committee | Sample size based on effect sizes; no a priori power calculation. | Sociodemographic factors, income, profession, occupational stressors | HCPs in Pakistan have poor adherence to dietary, exercise, and mental well-being guidelines, impacting both personal and professional outcomes. |

| 26.Waqas Ahmad et al., (2015)[44] | Cross-sectional | Healthcare professionals (N = 1,319; doctors, nurses, dentists, pharmacists, physiotherapists in Punjab, Pakistan) | Diet, exercise, mental well-being, chronic illnesses, occupational stressors | Comparison with global and USDA dietary standards, AHA exercise guidelines, WEMWBS mental well-being scores | Not disclosed | Identified significant predictors of mental well-being (p < 0.05) | Convenience sampling, restricted to Punjab, no validated occupational stress scale; BMI based on self-reported data; limited generalizability to Pakistan. | Ethical approval obtained, but WEMWBS not translated into Urdu | Not calculated; convenience sampling used with 87.35% response rate | Sociodemographic factors, household income, career satisfaction | HCPs in Punjab exhibit suboptimal dietary and exercise habits, moderate mental well-being, and high occupational stress levels affecting both personal and professional health. |

| 27.Taylor, M. (2012)[45] | Clinical guidance document developed by Oral Health & Nutrition Reference Group; not empirical research; single-author group | Healthcare professionals (dentists and oral health teams) in Scotland; recommendations tailored to general population, especially children under 5 | Use of dietary strategies and oral health advice (impact of fermentable carbohydrates, nutrient quality, frequency of eating) | Not applicable — guidance compares best-practice dietary/oral hygiene recommendations to standard or baseline practices | Developed under NHS Health Scotland; no conflicts of interest reported | Not applicable (guidance, not original research) | Based on expert consensus and existing evidence; no new data; may not reflect all global contexts; guidance publication date (2012) may limit current relevance | Not required (guidance document, not human subjects research) | Not applicable | Not applicable; recommendations inherently account for common dietary/oral health factors | Evidence-based oral health and nutrition advice aimed at reducing caries risk, promoting healthy diet frequency and content, supporting professional oral health counselling practices |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).