Submitted:

19 March 2025

Posted:

20 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Participants

2.2. Dependent Variables

2.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

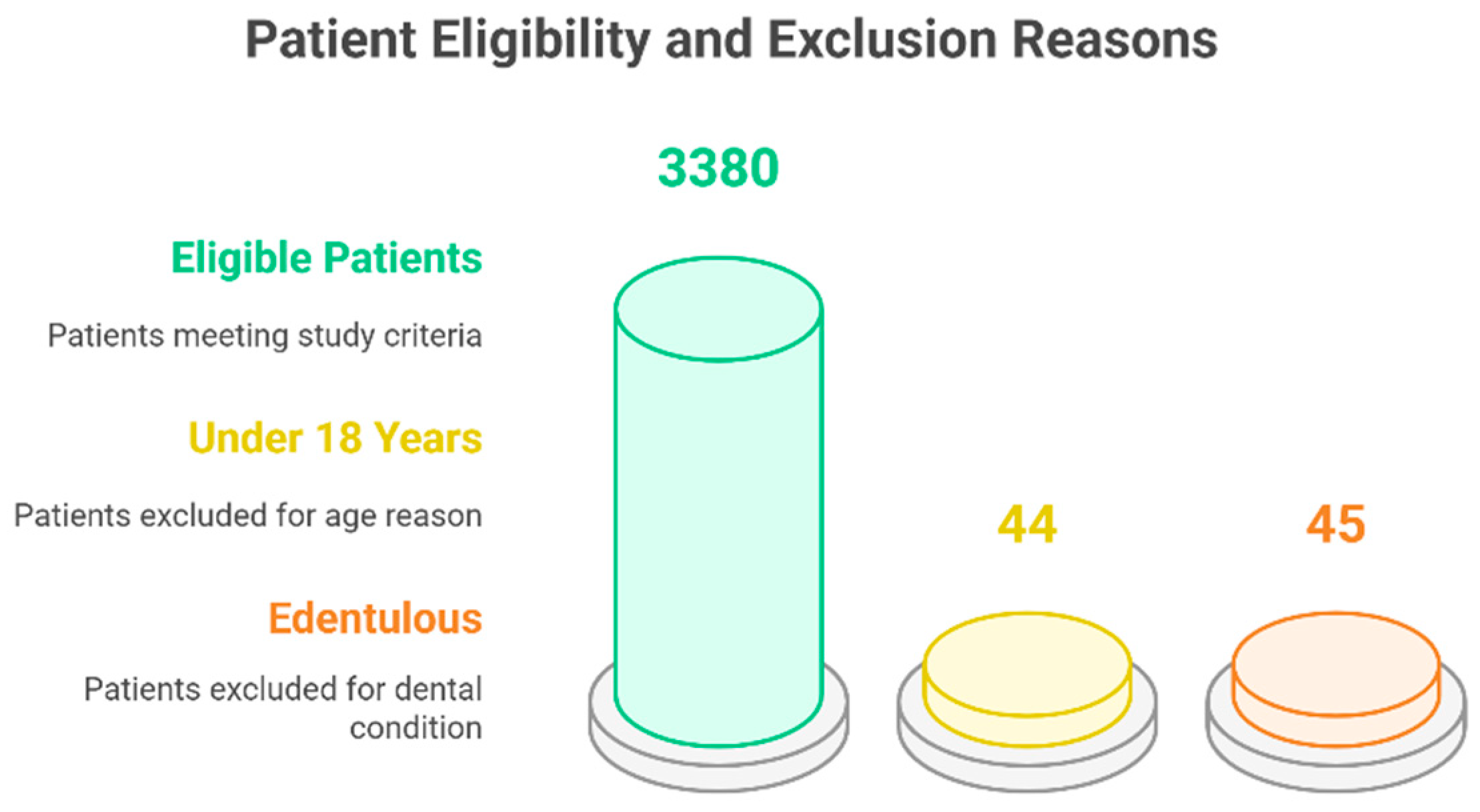

3.1. Participants inclusion and characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Halabi, M.; Salami, A.; Alnuaimi, E.; Kowash, M.; Hussein, I. Assessment of paediatric dental guidelines and caries management alternatives in the post COVID-19 period. A critical review and clinical recommendations. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry 2020, 21, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, T.F.d.; Martins, M.L.; Jural, L.A.; Maciel, I.P.; Magno, M.B.; Coqueiro, R.d.S.; Pithon, M.M.; Leal, S.C.; Fonseca-Gonçalves, A.; Maia, L.C. Did the Use of Minimum Interventions for Caries Management Change during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Cross-Sectional Study. Caries Research 2023, 57, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekes, K.; Ritschl, V.; Stamm, T. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on pediatric dentistry in Austria: Knowledge, perception and attitude among pediatric dentists in a cross-sectional survey. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 2021, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cărămidă, M.; Dumitrache, M.A.; Țâncu, A.M.C.; Ilici, R.R.; Ilinca, R.; Sfeatcu, R. Oral Habits during the Lockdown from the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in the Romanian Population. Medicina 2022, 58, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, E.; Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Proença, L.; Mendes, J.J.; Manso, A.C. Caries Experience before and after COVID-19 Restrictions: An Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak-Szymanik, A.; Wdowiak, A.; Szymanik, P.; Grocholewicz, K. Pandemic COVID-19 influence on adult’s oral hygiene, dietary habits and caries disease—literature review. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19, 12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.M.; Jeffery, R.W. Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults. Health psychology 2003, 22, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichter, M.; Nichter, M.; Carkoglu, A.; Tobacco Etiology Research, N. Reconsidering stress and smoking: a qualitative study among college students. Tob Control 2007, 16, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, J.A.; West, R. Self-perceived smoking motives and their correlates in a general population sample. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2009, 11, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, C.; Dingemans, A.; Junghans, A.F.; Boevé, A. Feeling bad or feeling good, does emotion affect your consumption of food? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2018, 92, 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, C.; Gökmen, V. Neuroactive compounds in foods: Occurrence, mechanism and potential health effects. Food Research International 2020, 128, 108744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martín, B.C.; Meule, A. Food craving: new contributions on its assessment, moderators, and consequences. 2015, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havermans, R.C.; Vancleef, L.; Kalamatianos, A.; Nederkoorn, C. Eating and inflicting pain out of boredom. Appetite 2015, 85, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama, Y.; Isumi, A.; Fujiwara, T. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic exposure on child dental caries: difference-in-differences analysis. Caries Research 2022, 56, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth 2019, 13, S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, E.; Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Proença, L.; Mendes, J.J.; Manso, A.C. Caries experience and risk indicators in a Portuguese Population: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.J.; Viana, J.; Cruz, F.; Garrido, L.; Jessen, I.; Rodrigues, J.; Proença, L.; Delgado, A.S.; Machado, V.; Botelho, J. Radiographically screened periodontitis is associated with deteriorated oral-health quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Plos one 2022, 17, e0269934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.L. The international standard classification of education 2011. In Class and stratification analysis; Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2013; Volume 30, pp. 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- Khamees, A.; Awadi, S.; Rawashdeh, S.; Talafha, M.; Alzoubi, M.; Almdallal, W.; Al-Eitan, S.; Saeed, A.; Al-Zoubi, R.M.; Al-Zoubi, M.S. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on smoking habits and lifestyle: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep 2023, 6, e1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, G.; Camussi, E.; Piccinelli, C.; Senore, C.; Armaroli, P.; Ortale, A.; Garena, F.; Giordano, L. Did social isolation during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic have an impact on the lifestyles of citizens? Epidemiol Prev 2020, 44, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Evripidou, K.; Siargkas, A.; Breda, J.; Chourdakis, M. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on smoking and vaping: systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 2023, 218, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.; Ferreira, S.; Moreira, P.; Machado-Sousa, M.; Couto, B.; Raposo-Lima, C.; Costa, P.; Morgado, P.; Picó-Pérez, M. Stress, anxiety, and depression trajectories during the "first wave" of the COVID-19 pandemic: what drives resilient, adaptive and maladaptive responses in the Portuguese population? Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1333997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmura, F.; Liberatore, L.; Musso, F.; Bravi, L.; Pierli, G. Organic Honey - Comparison of Generational Behaviour and Consumption Trends After Covid-19. Journal of Food Products Marketing 2024, 30, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedik, P.; Hudecova, M.; Predanocyova, K. Exploring Consumers' Preferences and Attitudes to Honey: Generation Approach in Slovakia. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Y.A.; Giorgio, G.M.; Addeo, N.F.; Asiry, K.A.; Piccolo, G.; Nizza, A.; Di Meo, C.; Alanazi, N.A.; Al-Qurashi, A.D.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impacts on bees, beekeeping, and potential role of bee products as antiviral agents and immune enhancers. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2022, 29, 9592–9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellana, F.; De Nucci, S.; De Pergola, G.; Di Chito, M.; Lisco, G.; Triggiani, V.; Sardone, R.; Zupo, R. Trends in Coffee and Tea Consumption during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.R.; Ackerman, J.M.; Wolfson, J.A.; Gearhardt, A.N. COVID-19 stress and eating and drinking behaviors in the United States during the early stages of the pandemic. Appetite 2021, 162, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thubsang, A.; Thiwongwiang, C.; Wisetdee, C.; Chompoonuch, J.; Anson, M.; Phalamat, S.; Arreeras, T. COVID-19 pandemic affected on coffee beverage decision and consumers’ behavior. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA); 2022; pp. 976–980. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, S.; Sosa-Napolskij, M.; Lobo, G.; Silva, I. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Portuguese population: Consumption of alcohol, stimulant drinks, illegal substances, and pharmaceuticals. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0260322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.L.; Pereira, J.L.; Franco, L.; Guinot, F. COVID-19 lockdown: impact on oral health-related behaviors and practices of Portuguese and Spanish children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 16004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszynska, E.; Cofta, S.; Hernik, A.; Otulakowska-Skrzynska, J.; Springer, D.; Roszak, M.; Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Self-Reported Dietary Choices and Oral Health Care Needs during COVID-19 Quarantine: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotnicka, M.; Karwowska, K.; Kłobukowski, F.; Wasilewska, E.; Małgorzewicz, S. Dietary Habits before and during the COVID-19 Epidemic in Selected European Countries. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestre, A.; Sospedra, I.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M.; Gutierrez-Hervas, A.; Fernández-Saez, J.; Hurtado-Sánchez, J.A.; Norte, A. Assessment of Spanish food consumption patterns during COVID-19 home confinement. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; Initiative, S. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 805–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n = 3,380) | Pre-lockdown (n =2,278 ) | Post-lockdown (n=1,102) |

| Sex, % (n) | |||

| Female | 59.4 (2,007) | 60.1 (1,369) | 56.8 (476) |

| Male | 40.6 (1,373) | 39.9 (909) | 43.2 (362) |

| Age, mean | 43.21 | 43.36 | 42.90 |

| Age interval (years), % (n) | |||

| 18-24 | 21.3 (719) | 21.2 (484) | 21.3 (235) |

| 25-44 | 32.4 (1,094) | 32.3 (736) | 32.5 (358) |

| 45-64 | 32.2 (1,088) | 31.9 (727) | 32.8 (361) |

| ≥65 | 14.2 (479) | 14.5 (331) | 13.4 (148) |

| Education, % (n) | |||

| No studies | 22.4 (756) | 24.1 (550) | 18.7 (206) |

| Elementary | 37.4 (1,265) | 37.7 (859) | 36.8 (406) |

| Middle | 26.9 (1,247) | 37.4 (853) | 35.8 (394) |

| Higher | 3.3 (112) | 0.7 (16) | 8.7 (96) |

| BMI (Kg/m2) % (n) | |||

| < 18,5 | 3.6 (120) | 3.8 (86) | 3.1 (34) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 46.1 (1,558) | 44.5 (1,013) | 49.5 (545) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 34.1 (1,153) | 34.4 (784) | 33.5 (369) |

| ≥ 30.0 | 16.2 (549) | 17.3 (35) | 14.0 (154) |

| Active Smoker % (n) | |||

| No | 79.2 (2,678) | 82.0 (1,869) | 73.4 (809) |

| Yes | 20.8 (702) | 18.0 (409) | 26.6 (293) |

| Variable | Total (n = 3,380) | Pre-lockdown (n =2,278 ) | Post-lockdown (n=1,102) |

| Type of toothbrush, % (n) | |||

| Manual | 88.6 (2,993) | 88.5 (2,017) | 88.6 (976) |

| Electric | 10.9 (368) | 10.8 (246) | 11.1 (122) |

| Toothbrush frequency % (n) | |||

| 2–3 times/daily | 75.6 (2,555) | 81.2 (1,847) | 64.2 (708) |

| 1 time/daily | 15.0 (507) | 15.5 (352) | 14.1 (155) |

| 2–6 times/weekly | 7.3 (248) | 1.9 (44) | 18.5 (204) |

| Never | 2.1 (70) | 1.5 (35) | 3.2 (35) |

| Dental Floss usage, % (n) | |||

| No | 65.8 (2,225) | 62.0 (1,413) | 73.7 (812) |

| Yes | 34.2 (1,155) | 38.0 (865) | 26.3 (290) |

| Mouth wash usage, % (n) | |||

| No | 56.9 (1,924) | 55.5 (1,264) | 59.9 (660) |

| Yes | 43.1 (1,456) | 44.5 (1,014) | 40.1 (442) |

| Variable | Total (n = 3,380) | Pre-lockdown (n =2,278 ) | Post-lockdown (n=1,102) |

| Fresh fruit % (n) | |||

| Several times a day | 44.7 (1,512) | 43.8 (997) | 46.7 (515) |

| Every day | 30.5 (1,031) | 30.4 (693) | 30.7 (338) |

| Once a week | 18.3 (618) | 19.1 (435) | 16.6 (183) |

| Several times a month | 2.7 (90) | 2.7 (61) | 2.6 (29) |

| Seldom/never | 3.8 (129) | 4.0 (92) | 3.4 (37) |

| Biscuits and cakes % (n) | |||

| Not know/not answer | 0.1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.3 (3) |

| Several times a day | 6.3 (213) | 5.9 (134) | 7.2 (79) |

| Every day | 17.8 (600) | 18.8 (428) | 15.6 (172) |

| Once a week | 44.1 (1,490) | 44.2 (1,007) | 43.8 (483) |

| Several times a month | 4.0 (135) | 4.3 (97) | 3.4 (38) |

| Seldom/never | 27.8 (939) | 26.9 (612) | 29.7 (327) |

| Jam or Honey % (n) | |||

| Not know/not answer | 0.1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.3 (3) |

| Several times a day | 1.1 (37) | 1.2 (28) | 0.8 (9) |

| Every day | 7.7 (260) | 7.0 (160) | 9.1 (100) |

| Once a week | 19.9 (673) | 19.4 (441) | 21.1 (232) |

| Several times a month | 2.0 (67) | 2.0 (46) | 1.9 (21) |

| Seldom/never | 69.2 (2,340) | 70.4 (1,603) | 66.9 (737) |

| Sweets/candies, % (n) | |||

| Not know/not answer | 0.1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.2 (2) |

| Several times a day | 5.6 (190) | 5.4 (122) | 6.2 (68) |

| Every day | 12.9 (436) | 13.2 (300) | 12.3 (136) |

| Once a week | 44.1 (1,490) | 43.4 (988) | 45.6 (502) |

| Several times a month | 3.6 (123) | 3.5 (79) | 4.0 (44) |

| Seldom/never | 33.7 (1,139) | 34.6 (789) | 31.8 (350) |

| Lemonade or soft drinks, % (n) | |||

| Not know/not answer | 0.1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.3 (3) |

| Several times a day | 6.4 (216) | 6.2 (141) | 6.8 (75) |

| Every day | 9.7 (327) | 10.2 (233) | 8.5 (94) |

| Once a week | 26.0 (878) | 25.9 (591) | 26.0 (287) |

| Several times a month | 3.3 (111) | 3.3 (75) | 3.3 (36) |

| Seldom/never | 54.6 (1,845) | 54.3 (1,238) | 55.1 (607) |

| Tea with sugar, % (n) | |||

| Not know/not answer | 0.2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.35 (6) |

| Several times a day | 2.8 (95) | 2.8 (64) | 2.8 (31) |

| Every day | 7.0 (237) | 7.1 (161) | 6.9 (76) |

| Once a week | 10.4 (352) | 10.7 (244) | 9.8 (108) |

| Several times a month | 1.5 (51) | 1.2 (27) | 2.2 (24) |

| Seldom/never | 78.1 (2,639) | 78.2 (1,782) | 77.8 (857) |

| Coffee with sugar, % (n) | |||

| Not know/not answer | 5.3 (178) | 0 (0) | 16.2 (178) |

| Several times a day | 21.0 (711) | 22.5 (512) | 18.1 (199) |

| Every day | 15.2 (513) | 16.3 (372) | 12.8 (141) |

| Once a week | 5.3 (180) | 6.0 (136) | 4.0 (44) |

| Several times a month | 1.3 (43) | 1.3 (29) | 1.3 (14) |

| Seldom/never | 51.9 (1,755) | 54.0 (1,229) | 47.7 (526) |

| Variable | Mean (Pre-lockdown) |

Mean (Post-lockdown) |

p-value | Significant Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 1.65 | 1.58 | 0.007 | Yes |

| Active smoker | 0.18 | 0.27 | <0.001 | Yes |

| Gum bleeding | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.367 | No |

| Dental mobility | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.167 | No |

| Fresh fruit consumption | 2.32 | 2.24 | 0.076 | No |

| Biscuits | 3.90 | 4.01 | 0.152 | No |

| Honey/Jam | 5.19 | 5.06 | 0.013 | Yes |

| Candy chewing | 5.39 | 5.46 | 0.199 | No |

| Sweets | 4.23 | 4.17 | 0.199 | No |

| Soft drinks | 4.69 | 4.73 | 0.247 | No |

| Tea with sugar | 5.31 | 5.29 | 0.772 | No |

| Coffee with sugar | 4.15 | 3.58 | <0.001 | Yes |

| Manual toothbrush | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.984 | No |

| Electric toothbrush | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.406 | No |

| Dental floss usage | 0.38 | 0.26 | <0.001 | Yes |

| Interdental brush | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.812 | No |

| Mouthwash usage | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.015 | Yes |

| Tooth brushing frequency | 0.24 | 0.62 | <0.001 | Yes |

| Teeth self-perception | 3.65 | 3.42 | 0.713 | No |

| Gum self-perception | 3.46 | 3.16 | 0.422 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).