1. Introduction

1.1. The Global Scale and Economic Burden of Early Childhood Caries

Oral health is an integral and inseparable component of overall health, yet Early Childhood Caries (ECC) persists as a significant and inadequately addressed global public health crisis [

1]. The World Health Organization has identified dental caries as the most common non-communicable disease worldwide, and its impact on pediatric populations is particularly severe [

1]. According to a landmark report from the U.S. Surgeon General, dental caries is the single most common chronic disease of childhood, occurring at a rate five times more frequently than asthma among children and adolescents [

2]. This high prevalence is not confined to a single nation, but is a widespread international phenomenon. A systematic review and meta-analysis of global data on ECC confirms that in many regions, the prevalence in preschool-aged children frequently exceeds 70%, though significant variation exists based on geography and socioeconomic conditions [

3].

To illustrate the scale of this issue, recent cross-sectional studies from various parts of the world paint a stark picture. In Asia, a study in Huizhou, China, reported a caries prevalence of 72.9% among 3–5-year-olds [

4], while a systematic review of studies in Indonesia found an overall prevalence of 76% [

5]. The situation is similarly dire in other regions; in rural Egypt, ECC affects 74% of preschool children [

6]. In some populations, the prevalence reaches near-universal levels, such as among preschoolers in the Palestinian Territories, where an alarming 97% experience dental decay [

7].

The consequences of such high prevalence extend beyond individual health, placing a substantial and growing burden on national healthcare systems [

1]. Global spending on oral healthcare, including both public and private sources, has reached approximately

$387 billion US dollars, although the allocation is highly uneven across different regions and nations [

8]. High out-of-pocket costs and catastrophic expenses prevent many from seeking oral health care. In 2015, dental issues cost approximately

$357 billion in treatment and

$188 billion in productivity losses worldwide, with disparities among countries of different income levels [

9].

The management of ECC often requires high-tech, interventionist care, which consumes significant financial resources, especially in high-income countries. This economic strain is compounded by shortages of appropriately trained oral healthcare personnel and systemic barriers that hinder the implementation of effective, widespread prevention programs [

1,

10].. As a result, healthcare systems are often locked in a cycle of reactive, costly treatment rather than cost-effective prevention, struggling to manage the sheer volume of need presented by the nearly 530 million children globally who suffer from untreated dental caries in their primary teeth [

1].

1.2. The Role of Socioeconomic Gradients and Social Determinants

The immense burden of ECC is not distributed equally across populations. Its prevalence is strongly and inversely correlated with national income levels and a range of interconnected socioeconomic factors [

3]. A clear socioeconomic gradient is well-documented in the literature, demonstrating that children from higher-income countries and more affluent families have significantly better oral health outcomes. A comprehensive systematic review found that children in high-income countries may have up to 90% lower odds of experiencing poor oral health compared to their counterparts in low- or middle-income nations [

11]. This disparity is starkly evident within the European continent, where a clear demarcation exists between wealthier Western European nations, which report lower caries rates, and less wealthy Eastern European nations like Romania, where the prevalence of dental caries remains particularly high [

11,

12].

These inequities are driven by a complex interplay of social determinants of health, which operate at the individual, family, and community levels [

13]. Among the most influential of these is parental education. A large body of evidence consistently shows that lower parental education levels are a significant risk factor for higher caries prevalence and poorer oral health behaviors in children [

14,

15]. The educational attainment of the mother, in particular, has been identified as a powerful predictor of a child’s oral health status, influencing factors such as dietary habits, oral hygiene practices, and the utilization of preventive and restorative dental care [

15]. For families residing in rural areas, the specific focus of the present study, these challenges are often magnified. Rural populations frequently face a unique set of persistent barriers to accessing pediatric dental care, including prohibitive out-of-pocket costs, lack of adequate insurance coverage, long travel distances to dental facilities, and a scarcity of pediatric dental providers [

16,

17].

1.3. The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Dual Threat to Pediatric Oral Health

The COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in early 2020, introduced an unprecedented disruption to this already challenging landscape, creating a dual threat to pediatric oral health. The first threat was the profound interruption of routine dental care. Globally, the pandemic triggered a significant and abrupt decrease in the utilization of preventive dental services for young children [

18,

19]. In the United States, for example, the proportion of children who had a dental visit in the past year fell from 82.6% to 78.2%, with preventive services experiencing the sharpest decline [

19]. Similar trends were reported internationally; a study in Saudi Arabia documented a drop of nearly 40% in pediatric dental patient flow during the pandemic period [

20]. This reduction in care was not only due to systemic lockdowns and clinic closures but was also fueled by widespread parental hesitancy, as caregivers delayed or avoided appointments due to fears of infection and other logistical challenges [

21]. While innovative solutions like teledentistry emerged to provide triage and ensure some continuity of care [

22,

23], its effectiveness was limited by challenges related to digital infrastructure and access, particularly in low-resource and rural communities. Teledentistry ultimately served as a valuable supplement but could not replace the necessity of in-person clinical examinations and preventive procedures [

23,

24].

The second, simultaneous threat was a significant and detrimental shift in children’s daily health behaviors. Numerous studies documented that lockdown measures led to negative changes in dietary habits, creating a more cariogenic environment within the home [

25,

26]. A clear and consistent trend emerged of increased consumption of high-calorie snacks, sweets, junk food, and sugary drinks [

25,

26]. This shift was attributed to a confluence of factors, including increased access to unhealthy foods at home, boredom from confinement, emotional eating as a coping mechanism for stress, and a general relaxation of parental rules regarding diet during a period of crisis [

26,

27]. This combination of reduced professional preventive care and increased daily exposure to cariogenic diets created a high-risk “perfect storm” environment, primed for the initiation and progression of dental caries in young, vulnerable children.

In Romania, the beginning of 2020 debuted with the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, which changed the perception and behavior of the population regarding dental treatments and quality of life [

28]. During the state of emergency, the dental offices were officially closed, with only a few dental offices open for emergency care [

29]. Although the pandemic has ended, it has changed perceptions regarding dental treatments: the anxiety has risen; the financial status of the population was affected, and the belief that oral health can be postponed has changed [

28].

1.4. Rationale and Aims of the Current Study

The existing literature clearly establishes the high global burden of ECC, its deep roots in socioeconomic disparities, and the dual pandemic-driven threats of reduced preventive care and increased sugar consumption. We know from robust evidence that early and regular preventive dental visits are highly effective, significantly reducing future caries incidence and promoting long-term oral health [

30,

31]. The widespread disruption to these visits is therefore a major public health concern. However, a critical gap remains in our understanding of the combined, quantifiable clinical impact of these pandemic-era trends within specific, high-risk populations.

Particularly in a setting like rural Romania, a region characterized by a high pre-existing caries burden, documented socioeconomic challenges, and known barriers to accessing care [

12,

16,

32], the net clinical consequences of the pandemic have not been directly measured. It is unknown how the positive finding of improved tooth-brushing frequency, as observed in our study, interacts with the negative impacts of increased sugar intake and reduced professional care. Therefore, this study was designed to fill this critical knowledge gap by providing a direct comparison of the oral health status of 6-year-old children in this vulnerable region, both pre- and post-pandemic. The primary objective was to assess the relationship between the COVID-19 period and observed changes in dental caries prevalence, oral hygiene habits, nutrition, and dental care utilization patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

A comparative, cross-sectional oral health survey was conducted in rural pediatric populations from Cluj County, in the Transylvania region of Romania. The study aimed to compare the oral health status between two distinct cohorts of 6-year-old children assessed at different time points: one pre-pandemic and one post-pandemic. The study protocol was approved by the relevant local (school), regional (school inspectorate), and national authorities (Ministry of Health from Romania, Approval No. 3411/05.04.2018), as referenced in the initial cohort’s publication [

32]. Prior to any examination, written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all participating children, in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Study Population and Sampling Strategy

The total study population comprised 213 children, aged 6 years old, from rural schools in Cluj County. The participants were allocated into two groups based on the period of assessment.

Group 1 (Pre-pandemic Cohort) consisted of 77 children from the Cluj County examined between 2018 and 2020 as part of a national oral health project. The sampling for this cohort followed the World Health Organization (WHO) Pathfinder survey methodology, a stratified cluster sampling approach designed to obtain representative data. The detailed application of this methodology has been described in a previous publication [

32].

Group 2 (Post-pandemic Cohort) consisted of 136 children examined in 2024. This cohort was recruited using a multi-stage convenience sampling method. Initially, a list of accessible rural schools within Cluj County was compiled. Subsequently, school headmasters were contacted to present the study’s objectives and procedures. All schools that expressed a willingness to participate were included in the sample. Within these consenting schools, parents of all 6-year-old children were invited to informational meetings where the study was explained. All children whose parents or legal guardians provided written informed consent were enrolled in the study.

2.3. Examiner Calibration

To ensure diagnostic consistency, all examiners involved in the study underwent a calibration process based on WHO guidelines (WHO, 2013). For Group 1, the calibration of examiners for the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) was conducted as detailed by Lucaciu et al. (2020) [

32], achieving a Cohen’s Kappa value of 0.75.

For Group 2, four experienced dentists were calibrated for the direct application of the DMFT index. In accordance with WHO (2013) criteria [

33], a tooth was recorded as Decayed (D) only when a lesion presented with an “unmistakable cavity, undermined enamel, or a detectably softened floor or wall” upon gentle probing. Inter-examiner reliability for the examining team was established once a Cohen’s Kappa value of 0.85 was achieved. The final clinical examinations for Group 2 were performed by two of the four calibrated dentists.

2.4. Data Collection and Diagnostic Criteria

Clinical examinations for both groups were conducted on school premises in a seated position under natural light, aided by a plane dental mirror and a ball-tipped WHO Community Periodontal Index (CPI) probe for gentle tactile assessment.

For Group 1, clinical data on caries status were collected using the two-digit ICDAS II coding system, which records both the restorative status and the severity of the carious lesion. For Group 2, caries status was assessed directly using the Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index.

In addition to the clinical examination, parents of all participants completed a structured questionnaire. The baseline instrument, based on WHO recommendations, collected data on parental education level, the frequency of and reasons for the child’s dental visits, oral hygiene habits (e.g., frequency of cleaning, tools used), and dietary patterns, with a focus on the consumption frequency of nine categories of sugary foods and drinks.

In addition to the clinical examination, the parents or legal guardians of all participants completed a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire administered to both groups, based on WHO recommendations for national surveys, was divided into the following sections: (1) Level of education for the father and mother (or other legal guardians); (2) Frequency of the child’s toothache or discomfort, number of dental visits in the last year, and the reason for the most recent dental visit (e.g., pain, check-up, treatment); (3) Frequency of teeth cleaning, types of tools used (e.g., toothbrush, toothpicks, dental floss), and whether toothpaste is used; and (4) A food frequency questionnaire assessing the consumption of nine specific categories of foods and drinks: fresh fruit; biscuits, cakes, cream, sweet pies, buns; sweetened soft drinks; sweetened fruit juices; honey; chewing gum containing sugar; sweets/candy; milk with sugar/honey; and cocoa with sugar/honey. Parents rated the frequency on a 5-point scale from “Never” to “A few times a day.”

For the Group 2 cohort, this questionnaire was supplemented with seven additional questions designed to assess the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2022). This supplementary section queried parents on: (1) Difficulties in accessing dental services when needed since 2020; (2) Financial challenges since the pandemic affecting their ability to prioritize the child’s dental care; (3) Changes in the child’s consumption of sugary snacks and drinks compared to the pre-pandemic period; (4) The development or worsening of stress-related oral habits (e.g., teeth grinding, nail biting) and whether these habits persist; (5) Changes in the frequency of the child’s dental visits compared to the pre-pandemic period; (6) Changes in the child’s level of fear of going to the dentist; and (7) Whether they believed dental problems in the past year were influenced by pandemic-related delays in care.

2.5. Data Transformation for Comparative Analysis

To facilitate a direct comparison between the two groups, the ICDAS data from Group 1 were systematically transformed into DMFT scores. This conversion was performed according to a validated methodology that defines caries at the cavitation threshold [

34]. The specific criteria for the transformation were as follows:

Decayed (D): A tooth was categorized as decayed if its most severe ICDAS caries code was 3 (localized enamel breakdown), 4 (underlying dark shadow), 5 (distinct cavity with visible dentin), or 6 (extensive distinct cavity). The inclusion of non-cavitated dentinal lesions (ICDAS 4) was consistent with the chosen validated protocol, although it is recognized that this extends beyond the strictest interpretation of a visible cavity.

Missing (M): A tooth was categorized as missing due to caries if it was recorded with ICDAS code 97.

Filled (F): A tooth was categorized as filled if the first digit of its ICDAS code, corresponding to restorative status, was 3 (tooth-colored restoration) or 4 (amalgam restoration).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were independently entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet by two researchers to verify accuracy. The collected data were analyzed using the Data Analysis ToolPak in Microsoft Excel and the Social Science Statistics online software package. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of data distribution. For comparing categorical variables between the two groups, such as the proportion of children with affected versus sound teeth, the Chi-square (χ²) test was used. The independent samples t-test was used to analyze differences in independent mean values, such as dietary scores. A p-value of less than .05 was considered to be statistically significant for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The final study population consisted of 213 children from two distinct cohorts: the pre-pandemic Group 1 (2018-2020), with a sample size of 77 children (n=77), and the post-pandemic Group 2 (2024), with a sample size of 136 children (n=136). The demographic characteristics of each cohort were analyzed to provide context for the clinical findings. The gender distribution showed slight differences between the groups. In Group 1, females constituted a majority of the sample at 57% (n=44), while males accounted for 43% (n=33). Conversely, Group 2 had a slight male majority, with males constituting 52% (n=71) and females 48% (n=65) of the cohort.

3.2. Clinical Caries Assessment: DMFT Comparison Between Groups

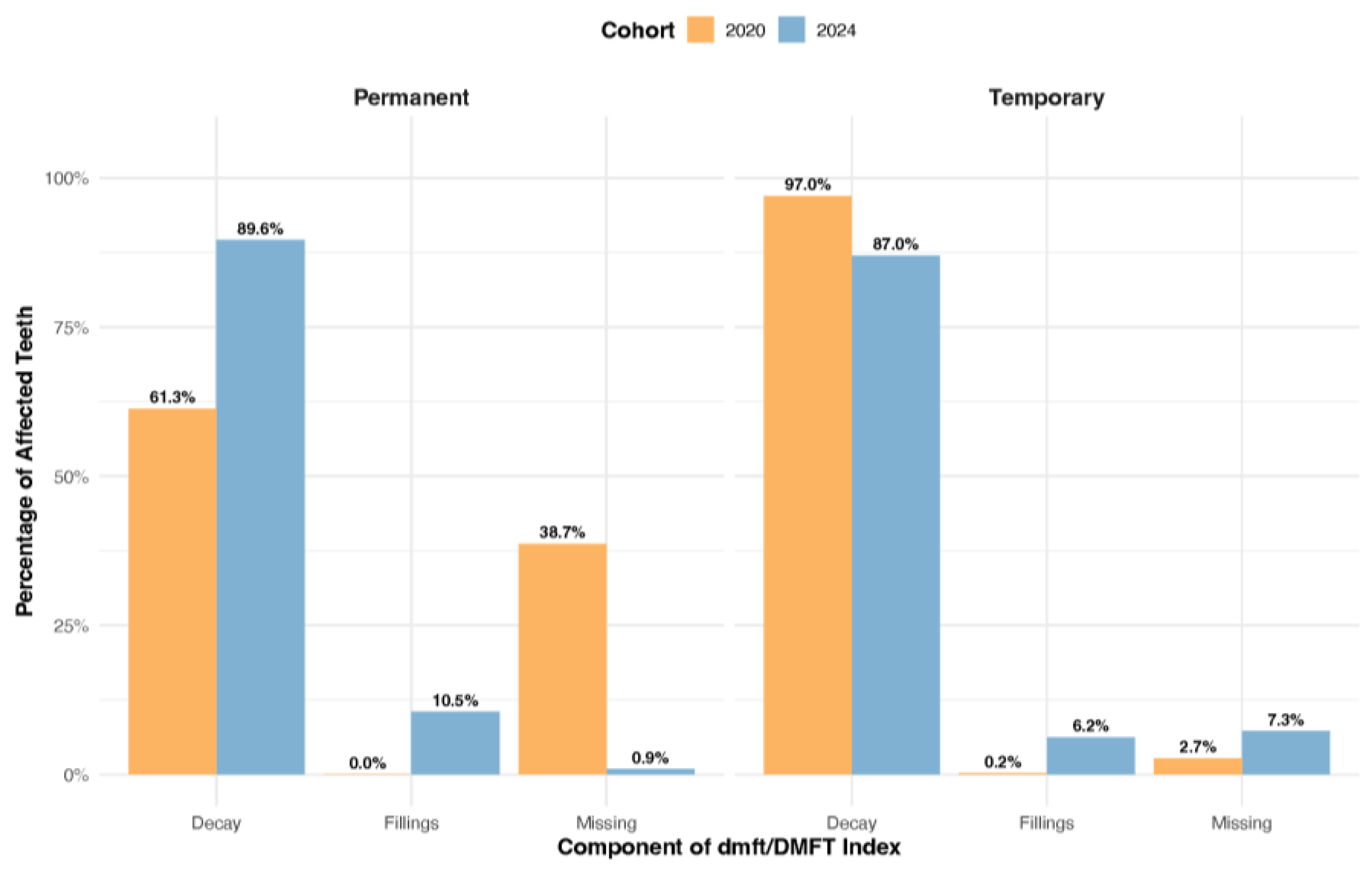

A comparison of caries experience revealed significant and contrasting patterns of disease between the two cohorts in both the primary and permanent dentitions. A detailed breakdown of the mean dmft/DMFT scores, their components, and tooth-level prevalence is presented in

Table 1. In the primary dentition, children in Group 1 (2020 cohort) demonstrated a significantly higher overall prevalence of affected teeth. An analysis of all primary teeth examined showed that 43.3% were affected by decay, extraction, or fillings, a figure substantially higher than the 26.8% observed in Group 2 (2024 cohort), with this difference being statistically significant (

p < .001). This elevated disease burden in the earlier cohort was primarily driven by untreated decay. The Decayed (D) component constituted 97.0% of all affected primary teeth in Group 1, a rate significantly higher than the 87.2% observed in Group 2 (χ² = 32.91,

p < .001). This indicates that while both groups experienced considerable decay, the contribution of untreated carious lesions to the overall disease picture was more pronounced in the pre-pandemic period. Conversely, indicators of dental treatment and disease sequelae showed an inverse trend. The proportion of missing (M) primary teeth due to caries was significantly higher in Group 2, representing 7.3% of affected teeth compared to just 2.7% in Group 1 (χ² = 10.99,

p = .001). Similarly, restorative care, represented by the Filled (F) component, was notably more common in the 2024 cohort. In Group 2, fillings accounted for 6.23% of affected primary teeth, a twenty-fold increase compared to the mere 0.3% observed in Group 1 (χ² = 11.69,

p < .001).

In the permanent dentition, a striking reversal of this pattern was observed. The 2024 cohort (Group 2) exhibited a significantly higher proportion of affected permanent teeth, at 29.6%, compared to only 6.8% in the 2020 cohort (Group 1), a highly significant difference (

p < .001), as shown in

Table 1. This increased disease prevalence in the later cohort was largely attributable to the decay (D) and filled (F) components. In Group 2, 89.6% of affected permanent teeth were decayed, and a notable 10.5% were filled, indicating that these children were experiencing and receiving treatment for caries in their newly erupted permanent teeth. This stands in stark contrast to Group 1, which had a lower proportion of decayed permanent teeth (61.3%) and, critically, no recorded fillings in the permanent dentition. The most dramatic difference was observed in the missing (M) component; in Group 1, tooth loss accounted for a substantial 38.7% of all affected permanent teeth. In Group 2, the count of missing permanent teeth was only two (n=2), a number too low to permit meaningful statistical comparison but indicative of a significant shift away from extractions as a management outcome for permanent teeth. A graphical overview providing a general summary of these clinical findings is presented in

Figure 1.

3.3. Association of Oral Health Status with Questionnaire Data

3.3.1. Parental Education Level

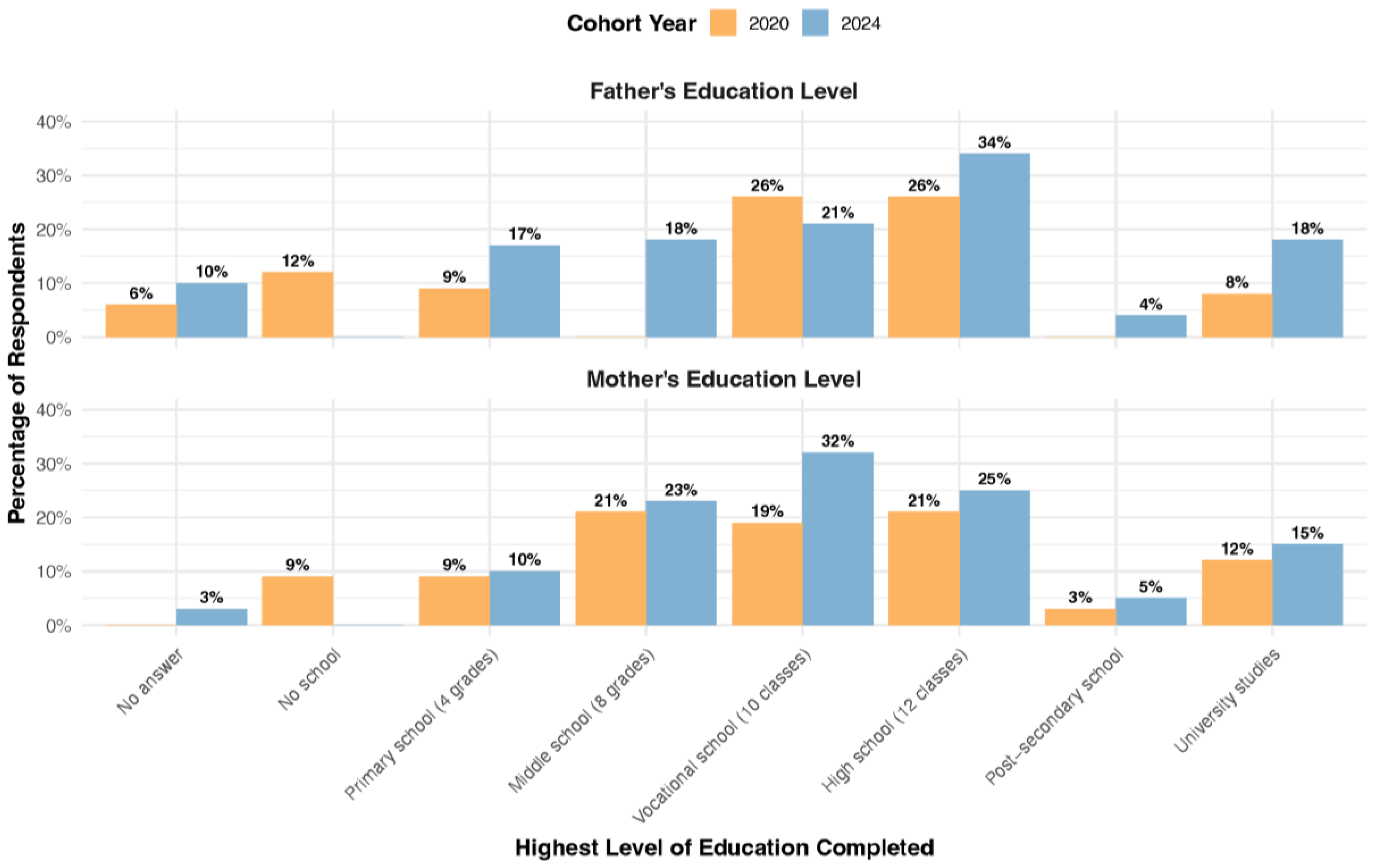

The educational attainment of parents, a key socioeconomic indicator, differed considerably between the two cohorts (

Figure 2). In Group 2, a higher proportion of parents reported completing high school or university studies compared to their counterparts in Group 1. Specifically, 34% of fathers and 25% of mothers in the 2024 cohort had completed high school, compared to 26% of fathers and 21% of mothers in the 2020 cohort. This trend was also evident at the university level, with 18% of fathers and 15% of mothers in Group 2 holding a university degree, compared to 8% and 12%, respectively, in Group 1.

An association was observed between these educational profiles and the clinical outcomes. The higher prevalence of restorative treatment (fillings) in Group 2 coincided with the higher overall level of parental education in that cohort. Conversely, the higher rate of missing permanent teeth due to disease in Group 1 was associated with a comparatively lower level of parental education, suggesting a potential link between socioeconomic factors and treatment pathways.

3.3.2. Consumption of Sweets

Analysis of dietary patterns, based on parental responses to the questionnaire, revealed a significant difference in the consumption of sugary foods and drinks between the two cohorts. As detailed in

Table 2, the 2024 cohort reported a statistically higher frequency of consumption for nearly all cariogenic items compared to the 2020 cohort. The most pronounced differences were seen in the consumption of “Fresh fruit,” “Cookies, cakes...,” and “Sweets/candies,” all of which were significantly higher in the 2024 cohort (p < 0.001). The overall mean sweets consumption score per child was also significantly higher in the 2024 cohort (2.36 ± 0.031) compared to the 2020 cohort (1.99 ± 0.079), confirming a shift towards a more cariogenic dietary pattern in the more recent group.

This observed increase in the consumption of sugary items in the 2024 cohort coincides with the clinical findings presented previously. Specifically, the higher reported sugar intake in the 2024 group is associated with the significantly higher prevalence of caries experience (DMFT) found in the permanent dentition of these same children.

3.3.3. Oral Hygiene and Dental Service Utilization

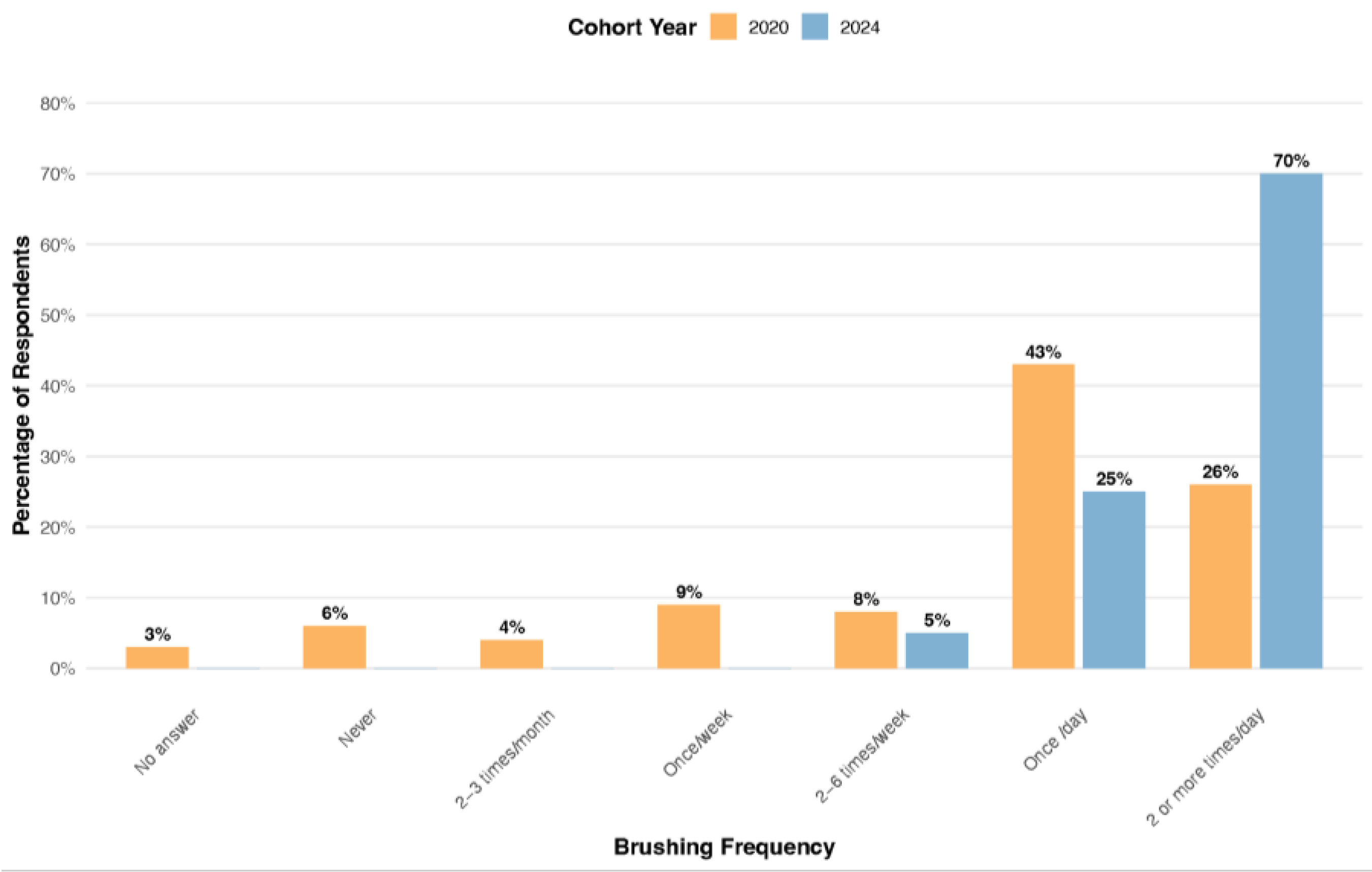

Self-reported oral hygiene habits, as depicted in

Figure 3, showed that a greater percentage of children in Group 2 reported brushing their teeth twice or more per day (70%, n=95) compared to Group 1 (26%, n=20). A substantially higher percentage of children in the 2024 cohort (Group 2) reported brushing their teeth two or more times per day (70%, n=95) compared to only 26% (n=20) of children in the 2020 cohort (Group 1). Conversely, a larger proportion of children in Group 1 reported brushing only once per day (43%, n=33) compared to Group 2 (25%, n=34). The clinical data were further analyzed to assess the relationship between this self-reported brushing frequency, mean sweets consumption, and primary caries experience (dmft), as detailed in

Table 3.

In the 2020 cohort, a clear association between more frequent brushing and better oral health was observed. Children who brushed at least twice a day had a significantly lower mean dmft score compared to those who brushed only once a day (4.67 vs. 6.74; p < 0.05). This finding aligns with the expected protective effect of regular oral hygiene.

However, a paradoxical pattern emerged in the 2024 cohort. Despite the higher reported frequency of brushing, no statistically significant reduction in mean dmft was observed for children brushing twice a day compared to once a day. Furthermore, the children in Group 2 who reported better hygiene (brushing ≥ twice/day) still presented with a higher mean dmft (4.93) than their counterparts in Group 1 who reported the same brushing frequency (4.67).

The data in

Table 3 suggest that the confounding influence of diet may explain this apparent paradox. Within each brushing frequency category, the children in Group 2 consistently had significantly higher mean sweets consumption scores than the children in Group 1. For instance, among children who brushed their teeth once a day, the mean sweets score for Group 2 was 2.44, significantly higher than the score of 1.96 for Group 1 (

t = -5.07,

p < .001). A similar significant difference was found for those brushing twice a day (

t = -4.57,

p < .001). This suggests that a more cariogenic diet negated the potential benefits of more frequent brushing in the 2024 cohort.

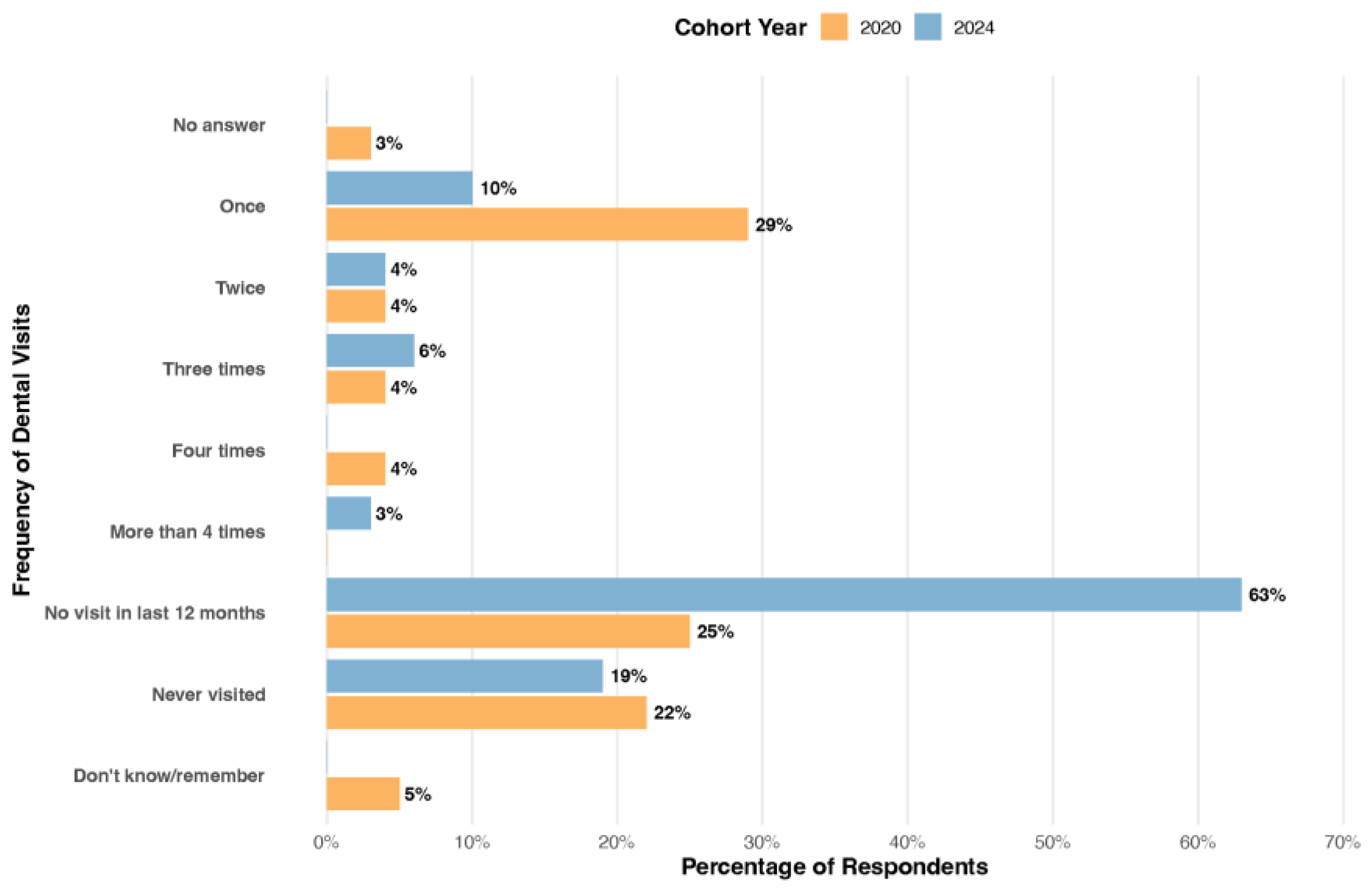

Profound differences in the patterns of dental service utilization were observed between the two cohorts (

Figure 4). The most striking finding was the high proportion of children in the 2024 cohort (Group 2) who had not accessed dental care in the preceding year. A significant majority of this group (63%, n=86) reported not having been to the dentist in the last 12 months, a figure more than double the 25% (n=19) reported for the 2020 cohort (Group 1). Conversely, children in the 2020 cohort reported more regular, if infrequent, visits. Nearly one-third of children in Group 1 (29%, n=22) had visited the dentist once in the last year, compared to only 10% (n=14) in Group 2. In total, 17% of children in Group 1 reported multiple visits (two or more) in the past year, compared to just 8% in Group 2. This difference in dental attendance is consistent with the clinical findings. The lack of recent dental visits in the 2024 cohort is associated with the higher percentage of untreated decay observed in their permanent dentition (89.6%) compared to the 2020 cohort (61.3%).

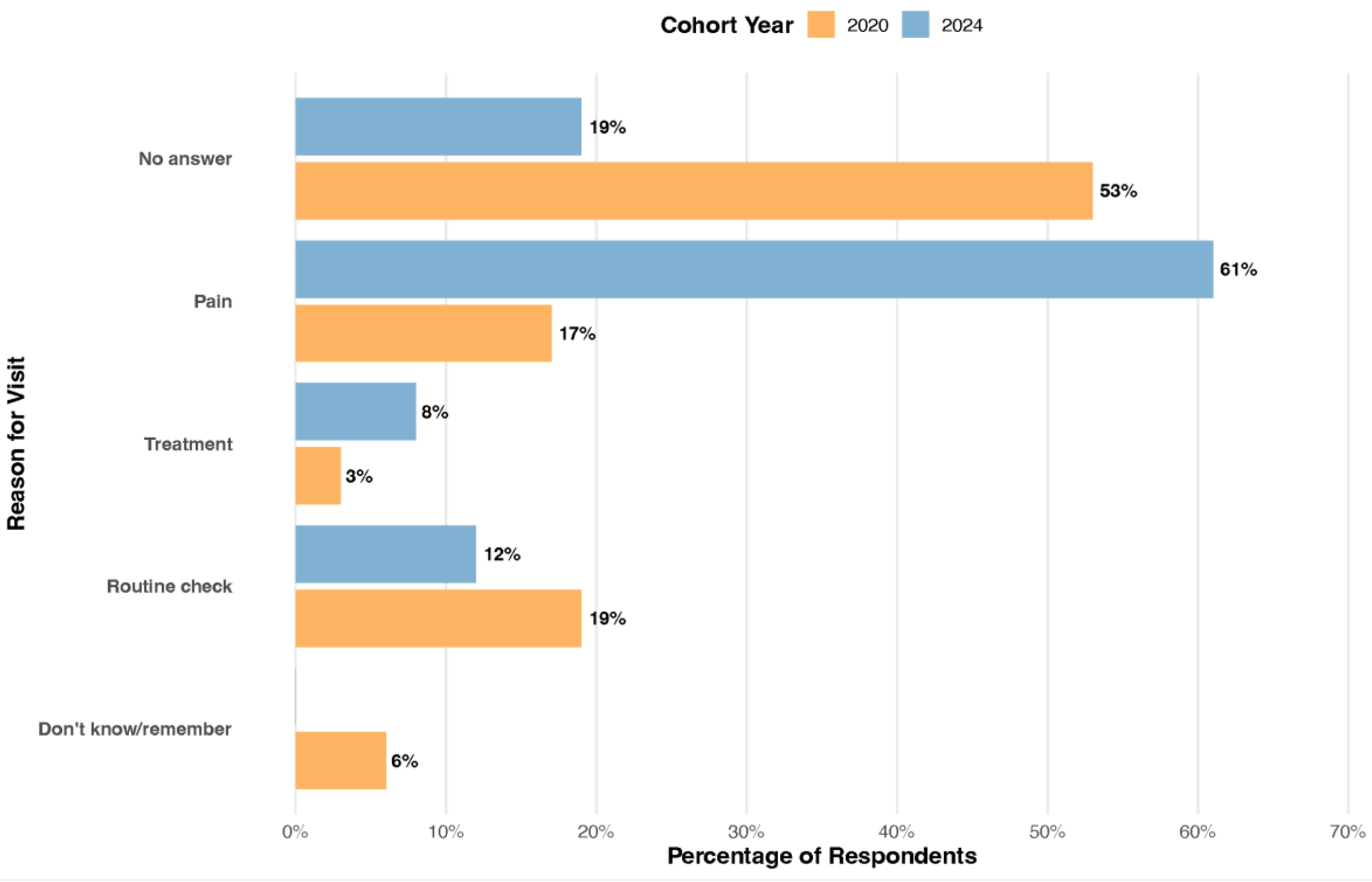

The motivation for seeking dental care differed significantly between the two cohorts (χ² = 38.70, p < .001), reflecting the shift in service utilization patterns. As shown in

Figure 5, the primary driver for dental visits in the 2024 cohort (Group 2) was the experience of pain, which accounted for a majority of visits (61%, n=83). In contrast, pain was a much less frequent reason for visits in the 2020 cohort (Group 1), accounting for only 17% (n=13) of attendances.

Conversely, routine check-ups were more common in the pre-pandemic period, making up 19% (n=15) of visits for Group 1, compared to 12% (n=16) for Group 2. These findings align with the self-reported data on dental problems, where a significantly higher proportion of children in the 2024 cohort reported experiencing pain or discomfort in the last year. This suggests a move away from preventive or routine care and towards problem-oriented, episodic care in the post-pandemic period.

3.4. Perceived Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The supplementary questionnaire administered to the parents of the 2024 cohort provided valuable insights into the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their children’s oral health. A notable portion of respondents (42%, n=57) directly attributed their child’s recent dental problems to pandemic-related factors, specifically citing restricted access to dental services. This perception is consistent with the clinical data, which show a high level of untreated decay, and the questionnaire data, indicating a lack of recent dental visits. Interestingly, 57% of these parents (n=78) also reported that their child had not required dental treatment in the last four years, a belief that contrasts with the clinical evidence of active disease. While a majority of parents (60%, n=82) believed their child’s sweets intake had remained stable, the comparative dietary data from Table 5 indicate a significant increase. On a positive note, most respondents (59%, n=80) felt that financial challenges during the pandemic did not negatively affect their ability to provide dental care or hygiene products for their children, suggesting that access and behavioral factors may have been more influential than direct economic hardship.

4. Discussion

The principal finding of this study is the emergence of a paradoxical and concerning oral health landscape among 6-year-old children in rural Romania following the COVID-19 pandemic. While our post-pandemic cohort demonstrated significantly improved oral hygiene practices, this positive behavioral shift was critically undermined by a concurrent increase in cariogenic dietary habits and a substantial decline in preventive dental care. This resulted in a four-fold increase in caries experience in the newly erupted permanent dentition, signaling a significant public health challenge that warrants immediate attention. This paper expands upon previous national data [

32] by providing a focused comparison of pre- and post-pandemic periods at a crucial age for dental development, offering a granular view of the pandemic’s multifaceted impact.

The central paradox observed, whereby improved toothbrushing frequency failed to confer a protective effect, is the most critical finding. Sugar consumption is the primary cause of caries; reducing sugar, especially frequency of intake, is the most effective prevention strategy. Toothbrushing with fluoride is a key protective behavior that helps mitigate, but does not fully counteract, the effects of high sugar consumption. Ideally, both behaviors should be optimized, maintaining a low-sugar intake and brushing twice daily with fluoride toothpaste. In children, sugar restriction is slightly more impactful in caries prevention than brushing alone, but both are essential and synergistic [

35]{Touger-Decker, 2003 #2705}. The post-pandemic cohort reported a near three-fold increase in children brushing at least twice daily (70% vs. 26%). In isolation, this suggests successful public health messaging [

36,

37]. However, this cohort also reported significantly higher consumption of sugary foods and drinks. This finding aligns with global trends documented during the pandemic, where lockdowns and heightened stress were linked to negative dietary changes and emotional eating [

38,

39]. The scientific literature is clear that while brushing is crucial, its protective effects can be overwhelmed by high-frequency sugar exposure, which maintains a constantly acidic oral environment conducive to demineralization [

40]. Our data compellingly suggest this is what occurred; the cariogenic challenge from the diet simply negated the benefits of more frequent mechanical plaque removal.

This narrative is further complicated by a dramatic shift in dental care utilization. The post-pandemic group had markedly fewer dental visits, with 63% of children not having seen a dentist in the last year, compared to just 25% in the pre-pandemic group. These results are in agreement with those of Chisini et al. (2021) [

41], who reported that in Brazil, dental procedures for children decreased by over 60% in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic levels. Critically, the motivation for visits shifted from routine check-ups to being primarily driven by pain (61% of visits vs. 17%). This represents a significant regression from proactive prevention to reactive, problem-oriented care. This trend, exacerbated by restricted access during the pandemic [

42], meant that opportunities for professional preventive measures like fluoride applications and fissure sealants on newly erupted permanent molars were missed. This lack of professional intervention, combined with the high-sugar diet, created a “perfect storm” for the explosive rise in caries observed in the permanent teeth (from 6.8% to 29.6% of teeth affected). The devastating impact of dental pain on a child’s and family’s quality of life, affecting sleep, school, and economic stability, is well-documented and highlights the societal cost of this trend [

43,

44].

An interesting divergence was noted between the two dentitions. While caries in the permanent dentition worsened, the overall dmft in the primary dentition was lower in the post-pandemic group. This may seem counterintuitive but can be explained by the composition of the index. The post-pandemic cohort, despite lower overall dmft, had a significantly higher proportion of missing (M) and filled (F) primary teeth. This suggests that when care was sought, likely due to advanced, painful lesions, the treatment was more definitive (extraction or restoration) rather than leaving decay untreated. In contrast, the alarming rise in DMFT in the permanent dentition is the most direct indicator of the pandemic’s impact, as these teeth erupted directly into a high-risk environment characterized by altered diets and reduced professional care. Newly erupted teeth are at a higher risk for caries because enamel continues to mature post-eruptively through the uptake of minerals. Immature enamel is more porous and less mineralized, making it more susceptible. The anatomy of first permanent molars presents deep pits and fissures, which are difficult to clean and easily retain plaque. Newly erupted molars may be partially covered by the gingiva, making the cleaning process more difficult [

45,

46].

The influence of socioeconomic factors, particularly parental education, adds another layer of complexity. Although parental perception is useful for screening and prompting care, clinical dental exams remain essential, especially for early detection of caries lesions. The post-pandemic cohort had parents with higher overall educational attainment, which correlated positively with improved brushing habits, a finding consistent with other studies [

47,

48]. However, this educational advantage did not translate into better dietary control or proactive dental visits, demonstrating that knowledge of one health behavior (hygiene) does not automatically confer protection if other, more powerful risk factors are not controlled. This disconnect highlights the need for interventions that extend beyond simple instructions and address the complex social and environmental factors influencing health behaviors [

49].

Finally, the data from the COVID-19-specific questionnaire reveal a dangerous disconnect between parental perception and clinical reality. A majority of post-pandemic parents believed their child’s sugar intake had not changed and that they did not require dental treatment. This contrasts sharply with our clinical and dietary data. This gap highlights a low level of oral health literacy and awareness, where parents may not recognize early-stage decay or may underestimate the impact of diet. It reinforces that interventions must not only educate but also empower parents to become accurate assessors of their child’s oral health risks and needs [

50,

51].

4.1. Limitations

This study is not without limitations. The use of two different sampling strategies (Pathfinder vs. convenience) may introduce selection bias. Furthermore, the conversion of ICDAS data to the DMFT index, while following a validated protocol, has inherent challenges. However, the study’s strength lies in its unique position to provide a real-world clinical snapshot of a vulnerable population before and after a major global disruption, revealing trends that have profound implications for public health policy in Romania and beyond.

4.2. Future Directions

The most effective public health interventions for reducing childhood caries are multicomponent programs that combine nutritional counseling with oral hygiene promotion, delivered early, consistently, and in a culturally tailored manner. These interventions are most successful when they target parents and caregivers, use behavioral change strategies, and involve multiple settings (e.g., schools, clinics, community centers).

There is also the political perspective linked with the increased prevalence of caries lesions in 6-year-old children, due to systemic healthcare shortcomings, lack of pediatric dental specialists in the public sector, and socioeconomic disparities. Addressing these issues requires improved access to dental care, targeted prevention programs, and greater investment in oral health education and workforce development.

5. Conclusions

This study identifies a significant challenge in post-pandemic pediatric oral health within rural Romania. We observed a paradoxical situation in which documented improvements in home oral hygiene practices did not prevent a marked increase in dental caries in the permanent dentition. This outcome appears to be driven by the concurrent negative impacts of more cariogenic dietary patterns and diminished access to routine preventive dental services, which together outweigh the benefits of more frequent toothbrushing.

These findings suggest that public health initiatives focused predominantly on a single behavior, such as toothbrushing, may be insufficient to address the multifaceted nature of caries risk in the current environment. An approach that relies heavily on individual hygiene without equally addressing systemic factors shows apparent limitations. Consequently, a strategic evolution of pediatric oral health policies is essential. Future national programs should be broadened to create a more integrated framework, supplementing hygiene education with robust nutritional counseling, implementing measures to encourage proactive dental attendance, and developing targeted initiatives to improve parental health literacy. Adopting such a comprehensive strategy is crucial for effectively mitigating caries risk and securing better long-term oral health outcomes for children in Romania and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.L., O.A. and M.B.U.; methodology, M.I., O.L., A.M. and A.I.F.; software, O.L.; validation, A.I.F., O.A. and M.B.U.; formal analysis, M.I., O.L., A.M. and A.I.F.; investigation, M.I.; resources, M.I., O.L. and A.M.; data curation, A.I.F.; writing, original draft preparation, M.I., N.B.P., I.C.M., A.M., A.I.F and O.L.; writing, review and editing, M.I., N.B.P., I.C.M., A.M. and O.L.; visualization, O.L., A.I.F., O.A. and M.B.U.; supervision, O.L., O.A. and M.B.U.; project administration, M.I. and O.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the relevant local (school), regional (school inspectorate), and national authorities (Ministry of Health from Romania, Approval No. 3411/05.04.2018).

Informed Consent Statement

For minor participants, written informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians. Participation was voluntary, with informed consent obtained, and all responses were anonymized to ensure data privacy and ethical compliance.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CPI |

Community Periodontal Index |

| D |

Decayed |

| dmft |

decayed, missing, and filled primary teeth |

| DMFT |

Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth |

| ECC |

Early Childhood Caries |

| F |

Filled |

| ICDAS |

International Caries Detection and Assessment System |

| M |

Missing |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| U.S. |

United States |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| χ² |

Chi-square |

| |

|

References

- Saikia, A.; Aarthi, J.; Muthu, M.S.; Patil, S.S.; Anthonappa, R.P.; Walia, T.; Shahwan, M.; Mossey, P.; Dominguez, M. Sustainable development goals and ending ECC as a public health crisis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satcher, D.; Nottingham, J.H. Revisiting Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Am J Public Health 2017, 107, S32–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maklennan, A.; Borg-Bartolo, R.; Wierichs, R.J.; Esteves-Oliveira, M.; Campus, G. A systematic review and meta-analysis on early-childhood-caries global data. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Y.; Chen, W.T.; Lin, L.D.; Ma, H.Z.; Huang, F. The prevalence of dental caries and its associated factors among preschool children in Huizhou, China: a cross-sectional study. Front. Oral Health 2024, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F.; Yuliana, L.T.; Budi, H.S.; Ramasamy, R.; Ambiya, Z.I.; Ghaisani, A.M. Prevalence of dental caries among children in Indonesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Heliyon 2024, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, D.; Elkashlan, M.K.; Saleh, S.M. Early childhood caries risk indicators among preschool children in rural Egypt: a case control study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateeb, E.; Lim, S.; Amer, S.; Ismail, A. Behavioral and social determinants of early childhood caries among Palestinian preschoolers in Jerusalem area: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484 (accessed on June 25th).

- Righolt, A.J.; Jevdjevic, M.; Marcenes, W.; Listl, S. Global-, Regional-, and Country-Level Economic Impacts of Dental Diseases in 2015. J Dent Res 2018, 97, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienhart, G.; Elsa, M.; Farge, P.; Schott, A.M.; Thivichon-Prince, B.; Chanelière, M. Factors perceived by health professionals to be barriers or facilitators to caries prevention in children: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, A.; Schmutz, K.A.; Borg-Bartolo, R.; Cocco, F.; Rosianu, R.S.; Jorda, R.; Maclennon, A.; Cortes-Martinicorenas, J.F.; Rahiotis, C.; Madléna, M.; et al. Caries status in 12-year-old children, geographical location and socioeconomic conditions across European countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 2025, 35, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, R.; Sava-Rosianu, R.; Jumanca, D.; Balean, O.; Damian, L.R.; Campus, G.G.; Maricutoiu, L.; Alexa, V.T.; Sfeatcu, R.; Daguci, C.; et al. Dental Caries, Oral Health Behavior, and Living Conditions in 6-8-Year-Old Romanian School Children. Children-Basel 2022, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shomuyiwa, D.O.; Bridge, G. Oral health of adolescents in West Africa: prioritizing its social determinants. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2023, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, G.; Franco, R.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Di Blasio, M.; Ronsivalle, V.; Cicciu, M. Children oral health and parents education status: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, R.; Sava-Rosianu, R.; Jumanca, D.; Balean, O.; Damian, L.R.; Fratila, A.D.; Maricutoiu, L.; Hajdu, A.I.; Focht, R.; Dumitrache, M.A.; et al. The Impact of Parental Education on Schoolchildren’s Oral Health-A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in Romania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, K.B.; Echeto, L.; Schentrup, D. Barriers to dental care in a rural community. J. Dent. Educ. 2023, 87, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.T.; Da Silva, K. Access to oral health care for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Wehby, G.L. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s oral health and oral health care use. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2022, 153, 787–+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karande, S.; Chong, G.T.F.; Megally, H.; Parmar, D.; Taylor, G.W.; Obadan-Udoh, E.M.; Agaku, I.T. Changes in dental and medical visits before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among US children aged 1-17 years. Community Dentist. Oral Epidemiol. 2023, 51, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, R.A.; Basudan, S.; Mahboub, M.; Baghlaf, K. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Dental Treatment in Children: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis in Jeddah City. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2022, 14, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, I.M.; Ghule, K.D.; Mathew, R.; Desai, J.; Gomes, S.; Mudaliar, A.; Bhori, M.; Tungare, K.; Gharat, A. Assessment of attitudes and practices regarding oral healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic among the parents of children aged 4-7 years. Dent. Med. Probl. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damoiselet, C.; Veynachter, T.; Jager, S.; Baudet, A.; Hernandez, M.; Clement, C. Teledentistry and management protocol in a pediatric dental department during the first COVID-19 lockdown. Arch Pediatr 2023, 30, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavi, A.; Atlasi, R.; Naemi, R. Teledentistry during COVID-19 pandemic: scientometric and content analysis approach. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golsanamloo, O.; Iranizadeh, S.; Jamei Khosroshahi, A.R.; Erfanparast, L.; Vafaei, A.; Ahmadinia, Y.; Maleki Dizaj, S. Accuracy of Teledentistry for Diagnosis and Treatment Planning of Pediatric Patients during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Telemed Appl 2022, 2022, 4147720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourghazi, F.; Eslami, M.; Ehsani, A.; Ejtahed, H.S.; Qorbani, M. Eating habits of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 era: A systematic review. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvetsky, A.C.; Kaidbey, J.H.; Ferguson, K.; Visek, A.J.; Sacheck, J. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Sugary Drink Consumption: A Qualitative Study. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umano, G.R.; Rondinelli, G.; Rivetti, G.; Klain, A.; Aiello, F.; Del Giudice, M.M.; Decimo, F.; Papparella, A.; Del Giudice, E.M. Effect of COVID-19 Lockdown on Children’s Eating Behaviours: A Longitudinal Study. Children-Basel 2022, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucaciu, O.; Boca, A.; Mesaros, A.S.; Petrescu, N.; Aghiorghiesei, O.; Mirica, I.C.; Hosu, I.; Armencea, G.; Bran, S.; Dinu, C.M. Assessing SARS-CoV-2 Infection Rate among Romanian Dental Practitioners. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerul Sănătății [Ministry of Health]. Ordin nr. 873 din 22 mai 2020 privind măsurile pentru prevenirea contaminării cu noul coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 și pentru asigurarea desfășurării activității în condiții de siguranță sanitară în domeniul asistenței medicale stomatologice, pe perioada stării de alertă. [Ordinance No. 873 of May 22, 2020 regarding measures for preventing contamination with the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and for ensuring the safe conduct of activities in the field of dental medical assistance, during the state of alert]. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/226057 (accessed on June 23).

- Babar, M.G.; Andiesta, N.S.; Bilal, S.; Yusof, Z.Y.M.; Doss, J.G.; Pau, A. A randomized controlled trial of 6-month dental home visits on 24-month caries incidence in preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2022, 50, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Houser, S.H.; Tian, M.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, J.; Zhang, W. Effects of early preventive dental visits and its associations with dental caries experience: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucaciu, P.O.; Mester, A.; Constantin, I.; Orban, N.; Cosma, L.; Candrea, S.; Sava-Rosianu, R.; Mesaros, A.S. A WHO Pathfinder Survey of Dental Caries in 6 and 12-Year Old Transylvanian Children and the Possible Correlation with Their Family Background, Oral-Health Behavior, and the Intake of Sweets. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Oral health surveys: basic methods - 5th edition. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548649#:~:text=Overview,into%20chronic%20disease%20surveillance%20systems.§ (accessed on June 23rd).

- Melgar, R.A.; Pereira, J.T.; Luz, P.B.; Hugo, F.N.; Araujo, F.B. Differential Impacts of Caries Classification in Children and Adults: A Comparison of ICDAS and DMF-T. Braz Dent J 2016, 27, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touger-Decker, R.; van Loveren, C. Sugars and dental caries. Am J Clin Nutr 2003, 78, 881S–892S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldo, M.; Matijevic, J.; Ivanisevic, A.M.; Cukovic-Bagic, I.; Marks, L.; Boric, D.N.; Jukic Krmek, S. IMPACT OF ORAL HYGIENE INSTRUCTIONS ON PLAQUE INDEX IN ADOLESCENTS. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosioara, A.I.; Nasui, B.A.; Ciuciuc, N.; Sîrbu, D.M.; Curseu, D.; Vesa, S.C.; Popescu, C.A.; Bleza, A.; Popa, M. Beyond BMI: Exploring Adolescent Lifestyle and Health Behaviours in Transylvania, Romania. Nutrients 2025, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmierski, K.F.M.; Borelli, J.L.; Rao, U. Negative affect, childhood adversity, and Adolescent’s Eating Following Stress. Appetite 2022, 168, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Mentzelou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papandreou, D.; Spanoudaki, M.; Vasios, G.K.; Pavlidou, E.; Mantzorou, M.; Giaginis, C. The Association of Emotional Eating with Overweight/Obesity, Depression, Anxiety/Stress, and Dietary Patterns: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozza, I.; Capasso, F.; Calcagnile, E.; Anelli, A.; Corridore, D.; Ferrara, C.; Ottolenghi, L. School-age dental screening: oral health and eating habits. Clin. Ter. 2019, 170, E36–E40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisini, L.A.; Costa, F.D.S.; Demarco, G.T.; da Silveira, E.R.; Demarco, F.F. COVID-19 pandemic impact on paediatric dentistry treatments in the Brazilian Public Health System. Int J Paediatr Dent 2021, 31, 1, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Fierro, N.; Borges-Yáñez, A.; Duarte, P.C.T.; Cordell, G.A.; Rodriguez-Garcia, A. COVID-19: the impact on oral health care. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2022, 27, 3005–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, A.; Bolat, D.; Hatipoglu, Ö. Impact of the severity and extension of dental caries lesions on Turkish preschool children’s oral health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira-Andrade, R.G.; Gomes, G.B.; de Almeida Pinto-Sarmento, T.C.; Firmino, R.T.; Pordeus, I.A.; Ramos-Jorge, M.L.; Paiva, S.M.; Granville-Garcia, A.F. Oral conditions and trouble sleeping among preschool children. Journal of Public Health 2016, 24, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinanoff, N.; Reisine, S. Update on early childhood caries since the Surgeon General’s Report. Acad Pediatr 2009, 9, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammari, A.B.; Bloch-Zupan, A.; Ashley, P. F. Systematic review of studies comparing the anti-caries efficacy of children’s toothpaste containing 600 ppm of fluoride or less with high fluoride toothpastes of 1,000 ppm or above. Caries res 2003, 37, 2, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, S.Y.; Meryem, B.; Abdellatif, M. Demographic factors associated with oral health behaviour in children aged 5-17 years in Algeria. Community Dent. Health 2024, 41, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, G.H.; Haag, D.; Bastos, J.L.; Mejia, G.; Jamieson, L. Triple Jeopardy in Oral Health: Additive Effects of Immigrant Status, Education, and Neighborhood. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2025, 10, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooley, M.; Skouteris, H.; Boganin, C.; Satur, J.; Kilpatrick, N. Parental influence and the development of dental caries in children aged 0-6 years: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of dentistry 2012, 40, 11, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomersall, J.C.; Slack-Smith, L.; Kilpatrick, N.; Muthu, M.S.; Riggs, E. Interventions with pregnant women, new mothers and other primary caregivers for preventing early childhood caries (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2024, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.Y.; Liao, C.S.; Lu, J.J.; Yeung, C.P.W.; Li, K.Y.; Gu, M.; Chu, C.H.; Yang, Y.Q. Improvement of parents’ oral health knowledge by a school-based oral health promotion for parents of preschool children: a prospective observational study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).