1. Introduction

Oral health in early childhood, especially the prevention of dental caries and the promotion of appropriate habits, represents a critical determinant of children’s well-being and general development, with persistent effects throughout life. However, in settings where socioeconomic inequalities limit access to preventive services, the availability of brief, validated instruments to assess oral health habits in infants is essential to drive early and tailored interventions.

In recent years, rigorous psychometric tools have been developed and validated[

1,

2], research results show the Hebrew version of the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale with excellent reliability (

α = 0.83) and confirmed factorial validity in the preschool population [

3], the Oral Health Values Scale (OHVS) of 12 items, with a multidimensional structure and robust internal consistency (α = 0.84) [

4] and the Parental Attitudes toward Child Oral Health (PACOH) in Lithuania, with a well-fitting factor model (

CFI = 0.93;

RMSEA = 0.05) and a significant association with children’s oral hygiene behaviors [

5].

However, there is no validated brief scale in the Ecuadorian context, which represents an important gap for the surveillance and promotion of children’s oral health. Therefore, the present study focused on analyzing the reliability and validity of the Brief Scale of Oral Health Habits in infants from Cuenca, Ecuador, evaluating its factor structure, internal consistency, and feasibility of local application.

Dental caries in childhood continues to be a major public health concern worldwide, and it particularly affects the school population. The World Health Organization has pointed out that oral diseases are a persistent problem of inequality, impacting children in contexts of socioeconomic vulnerability more severely [

6]. In Latin America, untreated carious lesions continue to be one of the most prevalent conditions among children and adults [

7]. In Mexico, a recent study with 826 schoolchildren aged 6 to 12 years reported that 65.8% had caries in primary dentition

, while 31.5% showed caries in permanent dentition

; Only 26.1% of the participants were caries-free in both dentition [

8]. In Ecuador, the picture is even more worrying: among schoolchildren aged 6 to 12 years in the southern provinces, the prevalence of caries reached 78% in primary teeth and 89.2% in permanent teeth

. In addition, the need for treatment was greater than 90% in primary teeth and 88% in permanent teeth; likewise, other studies show a high prevalence of dental caries in children from the Galapagos Islands of Ecuador, which increases with age [

9], and evidence shows a 60.3% of

dental caries in the capital of the country[

10]. These alarming indicators of oral disease suggest a serious epidemiological burden on the Latin American school child population, which underscores the urgency of developing and applying valid, brief, and culturally adapted instruments that allow for rapid detection of harmful habits and support more effective community interventions [

11].

In recent years, psychometric validation in pediatric dentistry has been consolidated with adaptations and development of instruments that measure oral quality of life, parental attitudes and results reported by child patients. For example, the Portuguese adaptation of the Child Oral Health Impact Profile Short Form 19 (COHIP-SF19) confirmed a valid structure and adequate internal consistency in schoolchildren, reinforcing its comparative use between languages and contexts [

12]. In preschoolers, the Hebrew version of the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS) demonstrated solid validity and reliability after providing recent evidence for its use in the early childhood population [

3]. In the domain of behaviors and family environment, the Parental Attitudes toward Child Oral Health

(PACOH) scale showed good structural fit through structural equation models and significant associations with hygiene practices and dental visits, underscoring the role of parental attitudes in children’s habits [

5].

To reconcile metrics between ages, the 5-item OHIP for school-aged children

(OHIP-5School) was developed and validated in school-age children, evidencing reliability and validity of the construct and facilitating comparability with adult versions[

13]. Overall, these advances reflect an increasingly systematic use of robust metrics (Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω, etc.), although methodological limitations persist such as moderate sample sizes, convenience sampling, and poor invariance assessment, which restricts the extrapolation of findings to different sociocultural contexts.

Considering the recent psychometric and epidemiological evidence, it is hypothesized that a Brief Scale of Oral Health Habits for infants in Cuenca, Ecuador, may present a one-dimensional structure, with acceptable internal consistency and adequate convergent validity, which would favor its cultural applicability in the Ecuadorian context. The Ecuadorian adaptation of the Oral Health Outcomes Scale for 5-year-olds

(SOHO-5) demonstrated satisfactory reliability and cross-cultural relevance in five-year-olds, reinforcing the usefulness of abbreviated versions in child populations[

14]. At the national level, studies in the Ecuadorian Amazon reported that 65.4% of children under six years of age had early caries, with oral pain in a third of cases and association with malnutrition [

15], while in rural areas a high prevalence of caries in children aged 5 to 9 years was documented, closely linked to parenting knowledge and practices [

16].

Likewise, the cultural and social disparities that modulate the impact of oral disease on the quality of life in childhood in Ecuador have been described [

17]. At the international level, the Portuguese version of the ECOHIS confirmed its robustness through reliability metrics [

18], while in Quito, recent studies in 12-year-old schoolchildren showed a relevant prevalence of periodontal diseases[

19]. In addition, adaptations of instruments in other languages, such as the Malagasy version of the ECOHIS, have shown adequate convergent validity and internal consistency [

20]. Taken together, this evidence reinforces the relevance of validating a brief and culturally adapted instrument in Ecuador, whose application can contribute both to the strengthening of local prevention programs and to the international availability of brief measures for the monitoring of oral health habits in children.

Therefore, the general objective of the research is to identify and analyze the validity and reliability of the Brief Scale of Oral Health Habits in infants in the city of Cuenca. To this end, it is proposed to evaluate the reliability of the scale through internal consistency, through indicators such as Cronbach’s alpha or McDonald’s omega, and to analyze structural validity through confirmatory factor analysis using adjustment indices such as the CFI (Comparative Fit Index), the TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) and the SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual). Likewise, it seeks to examine the convergent validity of the scale from the calculation of the AVE (Average Variance Extracted), explore the correlations between the items to determine internal coherence and, finally, identify possible differences by sex in the items selected from the scale through pertinent comparative analyses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

An instrumental study was carried out to evaluate the reliability, as well as the structural and convergent validity of the instrument.

2.2. Participants

The sample was made up of 105 infants from the city of Cuenca. The average age was 8.9 years (SD = 1.3), with an age range between 7 and 12 years, which reflects a child population in primary, middle, and higher education stages. Regarding sex, a balanced distribution was observed, although with a slight female predominance: 53.3% of the participants were girls (n = 56), while 46.7% were boys (n = 49). This proportion allows comparative analyses to be carried out between both groups. Regarding residence, most of the infants came from urban areas, representing 60.0% (n = 63), while 40.0% (n = 42) belonged to rural areas.

This distribution shows a greater participation of children living in urban contexts. Finally, when analyzing the school grade, it was found that 25.7% of the participants were in the third grade (n = 27), 28.6% in the fourth grade (n = 30), another 28.6% in the fifth grade (n = 30) and 17.1% in the sixth grade (n = 18). This distribution shows a heterogeneous representation of the different levels of primary education (

Table 1).

2.3. Instruments

A structured questionnaire was used for data collection that included sociodemographic variables (age, sex, residence classified as rural or urban, school grade, date of application and responsible) and the Initial Scale of Oral Health Habits, made up of fifteen questions with a Likert-type response format (Yes, Sometimes, No and I don’t know). The questions were as follows: Q1: Do you brush your teeth 2 times a day or more?, P2: Do you brush after eating?, P3: Do you floss 2 times a week or more?, P4: Do you use mouthwash after brushing?, P5: Does your toothpaste have fluoride?, Q6: Do you eat sweets every day?, P7: Do you know why sweets (soda, sweets, sweets, cakes, etc.) do they damage your teeth?, Q8: Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt, 1 time a year?, P9: Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt 2 times or more a year?, P10: Do you like to go to the dentist?, P11: Do you know what a cavity is?, P12: Do you change your brush when it’s old?, Q13: Do your parents or caregivers help you take care of your teeth?, Q14: Do you think your teeth can get sick from what you eat? and P15: Would you like to learn how to take care of your teeth?; with these questions it was possible to evaluate both oral hygiene practices and knowledge and attitudes towards dental care of infants in Cuenca.

2.4. Procedures

In the first phase, an Initial Scale of Oral Health Habits was designed and applied to the participating child population, which had been previously reviewed and validated in content by a panel of experts in dentistry and psychometrics. Once the initial scale was applied, the data were processed and statistical analyses were performed, specifically an exploratory factor analysis and a confirmatory factor analysis, to evaluate the internal structure and debug the items. From these psychometric analyses, the final version of the instrument was determined, obtaining a Brief Scale of Oral Health Habits. Subsequently, with the defined brief scale, the additional statistical analyses described in the study were carried out, always guaranteeing the standardization of the process and compliance with the ethical principles of research.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was performed that included the calculation of descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values and percentiles) and the Shapiro–Wilk normality test was applied for each item. Subsequently, an exploratory factor analysis was carried out using the maximum likelihood extraction method with varimax rotation, considering values equal to or greater than 0.40 as a cut-off point for the factor loads. In addition, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed to examine structural validity, applying fit indices with acceptable cut-off points of CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.90, and SRMR ≤ 0.08. The reliability of the scale was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega, considering values equal to or greater than 0.70 as adequate, and the AVE was calculated to determine convergent validity, taking values equal to or greater than 0.50 as a criterion. Correlations were also made between the items to explore internal coherence and comparative analyses by sex were carried out to identify possible differences in the scores of the selected items.

3. Results

In general, the descriptive values show that most of the items have low averages, which indicates that in several habits a reduced frequency of positive responses (Yes) is still observed. For example, P1: “Do you brush your teeth 2 times a day or more?” had a mean of 1.28 (SD = 0.628), with values between 1 and 3, reflecting that most children report not consistently following this habit. Similarly, P2: “Do you brush after eating?” showed a mean of 1.43 (SD = 0.745), also tending to negative or infrequent responses.

In contrast, items with higher means are observed, which indicates a higher frequency of affirmative responses. For example, P3: “Do you floss 2 times a week or more?” reached an average of 2.58 (SD = 0.864), ranking among the most performed practices. Likewise, P4: “Do you use mouthwash after brushing?” obtained a mean of 2.20 (SD = 0.934), showing a moderately frequent practice.

Other habits, such as P5: “Does your toothpaste have fluoride?” with a mean of 1.80 (SD = 1.274) and P6: “Do you eat sweets every day?” with a mean of 2.02 (SD = 0.557), show variability in the answers, highlighting that in some cases the consumption of sweets is frequent. In terms of knowledge and prevention, P7: “Do you know why candy hurts teeth?” had an average of 1.70, and P8: “Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt, 1 time a year?” reached 2.09, showing moderate attitudes towards preventive care.

Likewise, P9: “Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt 2 times or more a year?” obtained a mean of 2.29 (SD = 0.968), highlighting a better disposition in some infants, while P10: “Do you like to go to the dentist?” presented a mean of 1.72, reflecting a certain neutrality. Items such as P11: “Do you know what a cavity is?” (mean 1.50) and P12: “Do you change your brush when it’s old?” (mean 1.14) showed low frequencies of affirmative answers, evidencing limitations in knowledge or practice.

Finally, P13: “Do your parents or caregivers help you take care of your teeth?” with an average of 1.35, P14: “Do you think your teeth can get sick because of what you eat?” with an average of 1.26 and P15: “Would you like to learn how to take care of your teeth?” with an average of 1.05, reflect that there is still ample room to strengthen oral health education and support. In all items, the Shapiro-Wilk normality test indicated values of p < .001, confirming non-normal distributions, so the use of non-parametric statistics is suggested for subsequent analyses (

Table 2).

The exploratory factor analysis performed on the items of the Brief Scale of Oral Health Habits showed that several items presented acceptable factor loads in a single factor, which suggests a one-dimensional structure. For example, P8: “Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt, 1 time a year?” obtained a high factor load of 0.804, with a low uniqueness (0.354), indicating that this item shares a large proportion of common variance with the rest of the scale. Similarly, P9: “Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt 2 times or more a year?” presented a load of 0.662 and a uniqueness of 0.562, which also supports its relevance within the identified dimension.

In contrast, some items such as P3: “Do you floss 2 times a week or more?” and P10: “Do you like to go to the dentist?” showed lower factor loads, of 0.402 and 0.383 respectively, accompanied by relatively high uniqueness (0.839 and 0.853), suggesting that these items explain lower common variance within the overall construct and may require further review or analysis. Other items listed (P4, P1, P11, P2, P5, P13, P6, P14, P15, P12 and P7) did not reach significant factor loads or were not retained in the final structure, showing high uniqueness, so they probably did not contribute substantially to the identified factor.

Regarding reliability and validity,

Table 3 shows that, despite the inclusion of items with low loads such as P3, the scale reached adequate global indicators: a Cronbach’s alpha (α) and a McDonald’s omega (ω) of 0.70, which indicates an acceptable internal consistency. The value of the AVE was 0.400, evidencing that 40% of the average variance is explained by the common factor, which is a point to strengthen to improve convergent validity. In addition, the fit indices of the factor model were excellent, with a CFI of 0.973, a TLI of 0.919 and an SRMR of 0.051, confirming adequate structural validity.

In summary, the scale shows a one-dimensional structure supported mainly by items such as P8 and P9, with good internal consistency and a well-adjusted factor model; however, some items with low loads, such as P3, could be revised to optimize the convergent validity of the measurement.

The correlation analyses between the selected items showed associations of low to moderate magnitude, some of them statistically significant. First, P3: “Do you floss 2 times a week or more?” showed a positive and significant correlation with P8: “Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt, 1 time a year?” (r = 0.246, p < .05), suggesting that those who tend to floss also report attending the dentist preventively at least once a year. In addition, P3 also showed a significant correlation with P9: “Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt 2 times or more a year?” (r = 0.283, p < .01), reinforcing the relationship between hygiene practices and more frequent preventive behaviors.

On the other hand, P8 was positively and significantly associated with P9 (r = 0.578, p < .001), indicating that those who visit the dentist once a year have a high probability of attending the dentist two or more times a year, reflecting consistency in preventive behaviors. Likewise, P8 also showed a significant correlation with P10: “Do you like going to the dentist?” (r = 0.354, p < .001), suggesting that the pleasure of attending the dentist is linked to a greater frequency of preventive visits.

In contrast, P3 did not show a significant correlation with P10 (r = 0.189, p > .05), and P9 was also not significantly associated with P10 (r = 0.073, p > .05), indicating that flossing and frequency of dental visits do not necessarily depend on subjective liking for dental visits. Together, these correlations show that the scale reflects coherent relationships between oral hygiene behaviors and preventive practices, although the attitudinal component (liking going to the dentist) is not always directly related to these practices.

Table 4.

Correlations of the items of the Brief Scale of Oral Health Habits in infants from Cuenca.

Table 4.

Correlations of the items of the Brief Scale of Oral Health Habits in infants from Cuenca.

| |

P3 |

P8 |

P9 |

P10 |

| P3 |

— |

|

|

|

| P8 |

0.246* |

— |

|

|

| P9 |

0.283** |

0.578*** |

— |

|

| P10 |

0.189 |

0.354*** |

0.073 |

— |

|

Note. Two-tailed significance: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 |

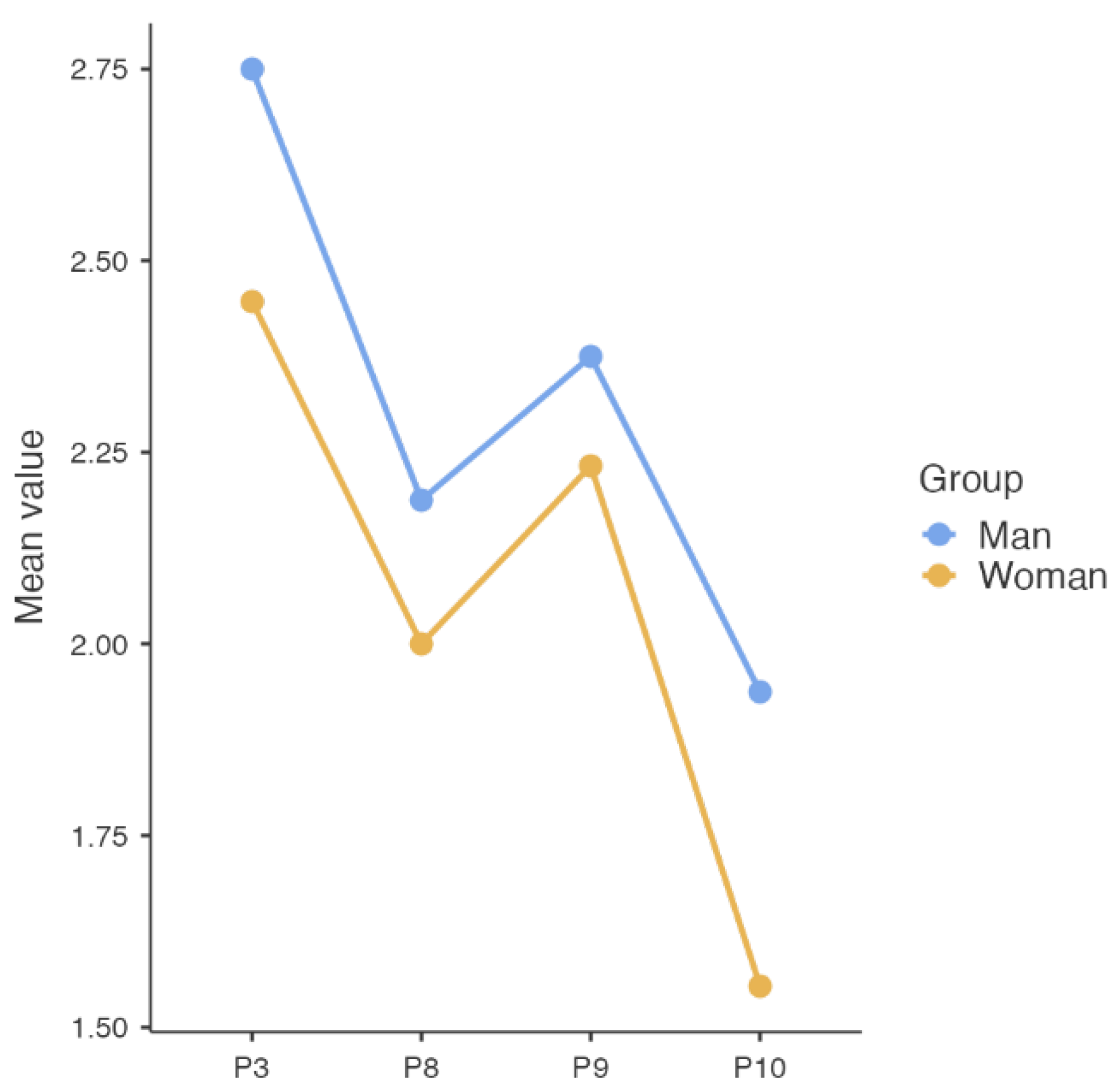

When analyzing the means by sex, it was observed that boys tended to report greater oral care practices compared to girls. In P3: “Do you floss 2 times a week or more?”, boys scored an average of 2,750 versus 2,446 for girls, indicating that boys reported flossing more frequently. In P8: “Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt, 1 time a year?”, again a slight advantage is observed in boys (mean of 2,188) compared to girls (mean of 2,000), reflecting a greater tendency to go to preventive consultations.

Likewise, in P9: “Do you go to the dentist even if your teeth don’t hurt 2 times or more a year?”, boys also showed a higher average (2,375) compared to girls (2,232), reinforcing the idea that more frequent preventive behaviors occur in this group. Finally, in P10: “Do you like to go to the dentist?”, the same trend was maintained, with an average of 1,938 in boys and 1,554 in girls, which suggests that boys report greater pleasure towards visiting the dentist.

Figure 1 visualizes these differences, showing parallel lines in the four variables evaluated, with consistently higher values for the male group compared to the female group. These differences suggest that, within the sample studied, boys have slightly more favourable habits and attitudes towards preventive oral health than girls, especially the use of dental floss and regular attendance at the dentist.

4. Discussion

The Brief Scale of Oral Health Habits constitutes a relevant contribution to pediatric dental research and to the design of strategies aimed at promoting oral health. The findings show a structure with internal consistency indicators and a factor model with adequate fit indices. This confirms that the scale is appropriate to reliably assess behaviors related to dental hygiene and prevention in children aged 7 to 12 years.

The internal consistency obtained in the present study (α and ω = 0.70) is within adequate parameters for instruments in pediatric populations, is consistent with brief scales and facilitates application in school and community contexts. Previous studies [

1,

3,

12] with similar tools have reported equivalent values. The Oral Health Impact Scale in Middle Childhood (MCOHIS) showed an acceptable internal consistency reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.75, the test-retest reliability showed a high stability coefficient of 0.98 [

1]. The Hebrew version of the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS) achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 and confirmed factor validity in preschoolers [

3], while the Portuguese adaptation of the COHIP-SF19 showed adequate internal consistency in schoolchildren [

12].

Regarding structural validity, the fit indices obtained exceeded the usually recommended cut-off points (CFI and TLI ≥ 0.90; SRMR ≤ 0.08), which supports the robustness of the one-dimensional model. These results are comparable to those reported in the validation of the PACOH in Lithuania (CFI ≈ 0.93; RMSEA ≈ 0.05) [

5], making it a reliable and context-specific tool.

The correlations observed between the questions reflect consistent associations between preventive practices and attitudes toward dental care. The strong correlation between visits to the dentist (questions P8 and P9) coincides with studies by Narváez et al., 2018 [

14]; Paiva et al., 2021 [

7]; Saquicela et al., 2025 [

16], who have documented consistency in the conduct of regularly attending dental check-ups [

7,

11]. Likewise, the association between liking dental visits (P10) and attending the dentist at least once a year suggests that attitudinal factors can reinforce preventive practices, although not determine them exclusively. Notably, flossing (P3) showed weaker correlations with dental visits. This result is consistent with the literature, which points to the use of dental floss as one of the least consolidated habits in childhood and strongly dependent on parental supervision [

15,

16].

Boys reported slightly more favorable preventive habits and attitudes than girls, both in flossing and in attending the dentist and the positive perception of visits. This difference contrasts with previous reports [

8,

22], where girls generally show greater adherence to health care practices. A possible explanation lies in specific contextual and cultural factors of the sample, such as the influence of school campaigns directed indistinctly or the variability in parental accompaniment according to sex. Similar results to those found here were reported in a study from the Ecuadorian Amazon [

15], where it was observed that boys received greater parental supervision in oral hygiene habits during the first school years.

The availability of a brief and validated scale in the Ecuadorian population has relevant implications for dental practice since it facilitates its application in school and community settings, allowing early identification of children with deficient habits and directing targeted interventions, offering a reliable resource to evaluate the effectiveness of oral health education programs. particularly in resource-constrained contexts where extensive instruments are not feasible.

In addition, the scale is in line with international recommendations to develop culturally adapted tools for monitoring children’s oral health [

6,

17]. Like short versions of ECOHIS in different languages [

3,

18,

20], this instrument represents an advance in the generation of comparable metrics between contexts, contributing to epidemiological surveillance and decision-making in public health.

Among the main limitations of the study is the sample size (n = 105), which, although suitable for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, restricts the possibility of evaluating the invariance of measurement between subgroups (sex, age or area of residence). Future research could expand the sample size and diversity, incorporating populations from different provinces and sociocultural contexts. It would also be advisable to evaluate the cross-cultural equivalence of the scale through adaptations in other Latin American countries, which would allow regional comparisons to be established and contribute to greater standardization in the measurement of children’s oral health habits.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study show that the Brief Scale of Oral Health Habits in infants in Cuenca presents adequate psychometric properties, both in terms of internal consistency and structural validity. The identification of a one-dimensional structure, supported by satisfactory fit indices, confirms the relevance of the instrument to reliably assess oral hygiene and prevention habits in children between 7 and 12 years of age.

The analysis of the correlations between the selected items showed coherent relationships between preventive practices and attitudes towards dental care, which reinforces the validity of the construct. Although some items showed low factor loads, the scale reached acceptable levels of reliability, which allows recommending its use in educational and community contexts.

Likewise, differences by sex were observed that suggest a slight advantage of men in the frequency of preventive practices and in the positive assessment of visits to the dentist. These findings contrast with previous research in other contexts, highlighting the influence of cultural and family factors on the development of oral health habits.

In practical terms, having a brief and validated instrument in the Ecuadorian context offers a valuable resource for the early detection of deficient habits and the planning of educational and preventive interventions aimed at children. Its application can contribute to optimizing oral health promotion programs and support decision-making in public policies aimed at reducing the high prevalence of caries and other oral diseases in childhood.

Finally, it is recommended that future research expand the size and diversity of the sample, including different regions of the country and evaluating the invariance between groups, to strengthen the generalization of the results and consolidate the usefulness of the scale as a regional and international tool.

Author Contributions

Contribution to the conception and design: A.R.; contribution to data collection: A.R., L.B.-B., H.S.-S., J.H.D., and F.J.R.-D.; contribution to data analysis and interpretation: A.R., J.V.Q.-C., and L.B.-B.; drafting and/or revising the article: A.R., L.B.-B., F.J.R.-D., and J.V.Q.- C.; approval of the final version for publication: A.R., L.B.-B., J.H.D., and F.J.R.-D.; Obtaining authorization for the scale: J.H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by the Universidad Politécnica Salesiana Sede Cuenca, Ecuador.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures conducted in this study involving human participants adhered to the ethical standards established by the ethics committee. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cuenca, Ecuador (code CEISH-UC-2024-018EO-IE). This research is derived from the research project entitled: Development of a serious game for the promotion and prevention of oral health in children aged 7 to 10 years at the Eugenio Espejo Educational Unit in Cuenca, Ecuador during the period 2025-2026.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research are publicly available and can be obtained by emailing the first author of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Ecuador, and especially Dr. Juan Cárdenas Tapia, PhD.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Taoufik, K.; Divaris, K.; Kavvadia, K.; Koletsi-Kounari, H.; Polychronopoulou, A. Development and Validation of the Greek Version of the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS).. [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, G.S.; Kularatna, S.; Weerasuriya, S.R.; Arrow, P.; Jamieson, L.; Tonmukayakul, U.; Senanayake, S. Comparison of the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS-4D) and EuroQol-5D-Y for Measuring Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Utility in Children. Qual Life Res 2025, 34, 385–393. [CrossRef]

- Gaon, O.; Natapov, L.; Ram, D.; Zusman, S.P.; Fux-Noy, A. Validation of a Hebrew Version of the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.B.; Randall, C.L.; McNeil, D.W. Development and Validation of the Oral Health Values Scale. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2021, 49, 454–463. [CrossRef]

- Zaborskis, A.; Razmienė, J.; Razmaitė, A.; Andruškevičienė, V.; Narbutaitė, J.; Bendoraitienė, E.A.; Kavaliauskienė, A. Parental Attitudes towards Child Oral Health and Their Structural Analysis. Children 2024, 11, 333. [CrossRef]

- Oral Health Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Paiva, S.M.; Abreu-Placeres, N.; Camacho, M.E.I.; Frias, A.C.; Tello, G.; Perazzo, M.F.; Pucca-Júnior, G.A. Dental Caries Experience and Its Impact on Quality of Life in Latin American and Caribbean Countries. Braz. oral res. 2021, 35, e052. [CrossRef]

- Vera-Virrueta, C.G.; Sansores-Ambrosio, F.; Casanova-Rosado, J.F.; Minaya-Sánchez, M.I.; Casanova-Rosado, A.J.; Casanova-Sarmiento, J.A.; Guadarrama-Reyes, S.C.; Rosa-Santillana, R. de la; Medina-Solís, C.E.; Maupomé, G.; et al. Experience, Prevalence, and Severity of Dental Caries in Mexican Preschool and School-Aged Children. Cureus 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Armas-Vega, A.; Parise-Vasco, J.M.; Díaz-Segovia, M.C.; Arroyo-Bonilla, D.A.; Cabrera-Dávila, M.J.; Zambrano-Bonilla, M.C.; Ordonez-Romero, I.; Caiza-Rennella, A.; Zambrano-Mendoza, A.; Ponce-Faula, C.; et al. Prevalence of Dental Caries in Schoolchildren from the Galapagos Islands: ESSO-Gal Cohort Report. Int J Dent 2023, 2023, 6544949. [CrossRef]

- Michel-Crosato, E.; Raggio, D.P.; Coloma-Valverde, A.N. de J.; Lopez, E.F.; Alvarez-Velasco, P.L.; Medina, M.V.; Balseca, M.C.; Quezada-Conde, M.D.C.; de Almeida Carrer, F.C.; Romito, G.A.; et al. Oral Health of 12-Year-Old Children in Quito, Ecuador: A Population-Based Epidemiological Survey. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 184. [CrossRef]

- Vélez-León, E.M.; Albaladejo-Martínez, A.; Cuenca-León, K.; Encalada-Verdugo, L.; Armas-Vega, A.; Melo, M. Caries Experience and Treatment Needs in Urban and Rural Environments in School-Age Children from Three Provinces of Ecuador: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dentistry Journal 2022, 10, 185. [CrossRef]

- Laborne, F.; Machado, V.; Botelho, J.; Bandeira Lopes, L. The Child Oral Health Impact Profile—Short Form 19 Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validity for the Portuguese Pediatric Population. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 4725. [CrossRef]

- Solanke, C.; John, M.T.; Ebel, M.; Altner, S.; Bekes, K. OHIP-5 FOR SCHOOL-AGED CHILDREN. Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice 2024, 24, 101947. [CrossRef]

- Narváez, J, Arias A. Validación y adaptación transcultural de la escala de resultados de salud oral para niños de 5 años (SOHO-5) en español Ecuatoriano. Odontología 2018, 20, 39–55.

- So, M.; Ellenikiotis, Y.A.; Husby, H.M.; Paz, C.L.; Seymour, B.; Sokal-Gutierrez, K. Early Childhood Dental Caries, Mouth Pain, and Malnutrition in the Ecuadorian Amazon Region. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017, 14, 550. [CrossRef]

- Saquicela-Pulla, M.; Dávila-Arcentales, M.; Vélez-León, E.; Armas-Vega, A.; Melo, M. Parental Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices and Their Association with Dental Caries in Children Aged 5–9 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2025, 22, 953. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, N.; Manresa-Cumarin, K.; Klabak, J.; Krupa, G.; Gudsoorkar, P. Assessing the Impact of Oral Health Disease on Quality of Life in Ecuador: A Mixed-Methods Study. Front. Oral Health 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Correia, C.; Ribeiro Graça, S.; Mendes, S. Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale: Psychometric Evaluation in Portuguese Preschoolers. Acta Stomatol Croat 58, 39–51. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Vega, M.; Ibarra, M.C.B.; Quezada-Conde, M.D.C.; Reis, I.N.R. dos; Frias, A.C.; Raggio, D.P.; Michel-Crosato, E.; Mendes, F.M.; Pannuti, C.M.; Romito, G.A. Periodontal Status among 12-Year-Old Schoolchildren: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study in Quito, Ecuador. Braz. oral res. 2024, 38, e002. [CrossRef]

- Randrianarivony, J.; Ravelomanantsoa, J.J.; Razanamihaja, N. Evaluation of the Reliability and Validity of the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS) Questionnaire Translated into Malagasy. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 39. [CrossRef]

- Asokan S, Geetha Priya PR, Viswanath S, Sivasamy S, Natchiyar SN. Development and validation of a novel Middle childhood oral health impact scale (MCOHIS). J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2022;40:55-61.

- Salud bucal en Estados Unidos: Avances y desafíos [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): Instituto Nacional de Investigación Dental y Craneofacial (EE. UU.); diciembre de 2021. Sección 2A, Salud bucal a lo largo de la vida: Niños. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578299.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).