Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a multifactorial inflammatory process characterized by the deposition of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL), endothelial cell injury, and plaque accumulation in the vessel wall [

1]. As a major risk factor for atherosclerosis, hypercholesterolemia leads to the deposition of ox-LDL within the endovascular wall [

2]. Ox-LDL induces endothelial cell injury through the LOX-1-ROS-NF-κB and p53-Bax/bcl-2-caspase-3 pathways, resulting in excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, release of adhesion molecules, and damage to low-density lipoprotein receptors [

3]. Endothelial cell injury and dysfunction are considered the initial steps in the formation of atherosclerosis [

4]. In atherosclerotic lesions of coronary arteries, senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal), a marker of cellular senescence, has been found in endothelial cells [

5]. Senescence of vascular endothelial cells may play a key role in vascular aging and the development of atherosclerosis [

6]. Moreover, ox-LDL can induce endothelial cell senescence by promoting excessive lipid deposition and overexpression of senescence-related proteins, such as p21 and p53 [

7].

Epigenetics refers to the regulatory processes that control heritable gene expression without altering the DNA sequence [

8,

9]. Various types of epigenetic modifications have been identified, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and regulation by non-coding RNAs, among which DNA and RNA methylation modifications are particularly important [

10,

11]. With the rapid development of specific antibodies and high-throughput sequencing technologies, N6-methyladenosine modification (m6A) has evolved from prokaryotes to eukaryotes [

12]. The basic process of m6A modification involves installation by m6A methyltransferases, removal by m6A demethylases, and recognition by m6A reader proteins, thereby regulating RNA metabolism methyltransferases [

13].

Increasing evidence suggests that m6A can influence the expression of target genes, thereby regulating various physiological processes [

14]. m6A modification is the most prevalent mRNA modification in eukaryotic cells and is a reversible chemical process dynamically controlled by the balanced activity of m6A methyltransferases and demethylases [

15]. Due to its critical role in RNA translation, stability, and alternative splicing, m6A modification is implicated in tumorigenesis, making it a potential key target [

16]. And dysregulation of methyltransferases, such as methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) and RNA-binding motif protein 15 (RBM15), has been reported in various diseases [

17]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of RBM15 in damage and senescence of endothelial cells during atherosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Treatment

HUVECs were bought from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) and incubated in endothelial cell medium (Thermo, USA) that added with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Procell, China) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin reagent (Gibco, USA). HUVECs were stimulated with 100 µg/mL ox-LDL (low-density lipoprotein; MCE, USA) for 24 h to induce cell damage. The SIRT6 siRNA and RBM15 overexpression vectors were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China) Cell transfection of plasmid (2 μg) and siRNA (50 nM) was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were collected for subsequent experiments.

Cell Viability

Cell viability was determined by l counting kit 8 (CCK-8) assay kit (Beyotime, China). In short, cells stimulated with ox-LDL and transfected with indicated oligonucleotides were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells per well. Cells were incubated in 37°C incubator for 48 h, and CCK-8 reagent was added for another 2-hour incubation. Then optical density (OD) values at 450 nm were measured.

Western Blot

The total proteins were extracted from HUVECs using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) that contains protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma, USA), and the concentrations of proteins were determined using the BCA assay kit (Beyotime, China). An equal amount of protein was separated using 8% to 10% SDS-PAGE and blotted to nitrocellulose (NC) membranes (Millipore, USA). The blots were blocked with 5% skim milk for 2 h and incubated with primary antibodies for RBM15, p21, p53, SIRT6, and β-actin overnight at 4°C. After that, the membranes were hatched in horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary ant-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were then incubated with ECL reagent (Thermo, USA) and visualized by an imaging system (Tanon, China). All antibodies were bought from Abcam (USA) and diluted at 1:2000 in PBST buffer.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Assay

Total RNA was extracted from HUVECs using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The cDNA synthesis reaction was conducted using First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Transgen, China). Next, cDNA was amplified and quantified using SYBR Green PCR system (Transgen, China). The relative levels of target genes were calculated using the 2-∆∆Ct method. β-actin was used as internal control.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels were measured by ELISA assay. In short, HUVECs were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured for 48 h, then cell culture medium was collected and analyzed with ELISA kits (Thermo, USA).

SA-β-Gal Assay

HUVECs were plated in 24-well plates after indicated induction and treatment. The cells were then fixed and stained with SA-β-gal staining working solution. Cells were then observed under optical microscopy (Leica, Germany).

Detection of SOD Activity

The SOD activity was measured by Total SOD activity detection kit (Beyotime, China) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were homogenized and reacted with working solution at 37°C incubator for 30 min. The values at OD 450 nm were measured and calculated.

Detection of MDA Production

Malondialdehyde (MDA) is the production of oxidative stress. HUVECs were lysed and the MDA level was measured by Malondialdehyde (MDA) Fluorometric Assay Kit in accordance with manufacturer’s protocol.

MeRIP-qPCR Experiment

The m6A modification level in SIRT6 mRNA was determined through Magna MeRIP m6A Kit (Millipore, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA was extracted, purified, and sonicated, followed by incubation with magnetic beads that conjugated with anti-m6A antibody. The methylated RNA was then eluted from beads and purified. SIRT6 mRNA level was analyzed by qPCR assay.

mRNA Stability Detection

At 48 h after transfection, HUVECs were treated with actinomycin D at 5 μg/ml (Sigma, USA) for 0, 3, and 6 h. Total RNA was then extracted, and SIRT6 mRNA level was analyzed via qPCR assay.

Statistics

Data in this study were shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. Data analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism Version 7 (GraphPad Software, USA). The difference between two groups was analyzed using student’s t-test, and the difference among more groups was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. Statistical significance was set when p value was less than 0.05.

Results

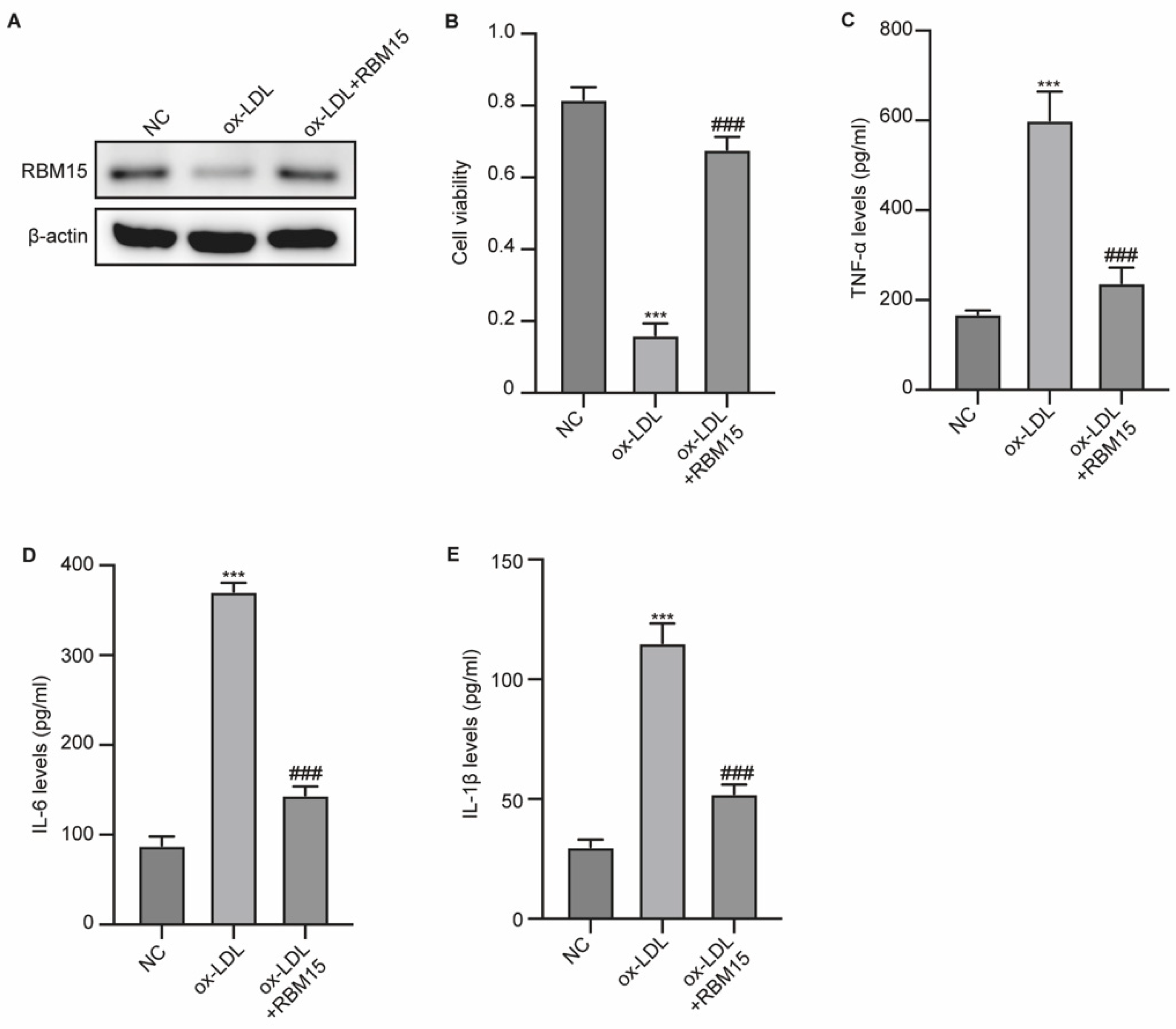

RBM15 Affects ox-LDL-Induced Damage of HUVECs

To evaluate the role of RBM15 in vascular damage, we established an ox-LDL-induced HUVEC model. We observed that ox-LDL induction notably reduced the expression of RBM15 in HUVECs, which is recovered by transfection with RBM15 overexpression vectors (

Figure 1A). Besides, the viability of HUVECs suppressed by ox-LDL was significantly reversed by RBM15 overexpression (

Figure 1B). Simultaneously, ox-LDL elevated the production of proinflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, and RBM15 overexpression repressed this elevation (

Figure 1C-E). These data indicated that RBM15 expression is correlated with HUVEC phenotypes.

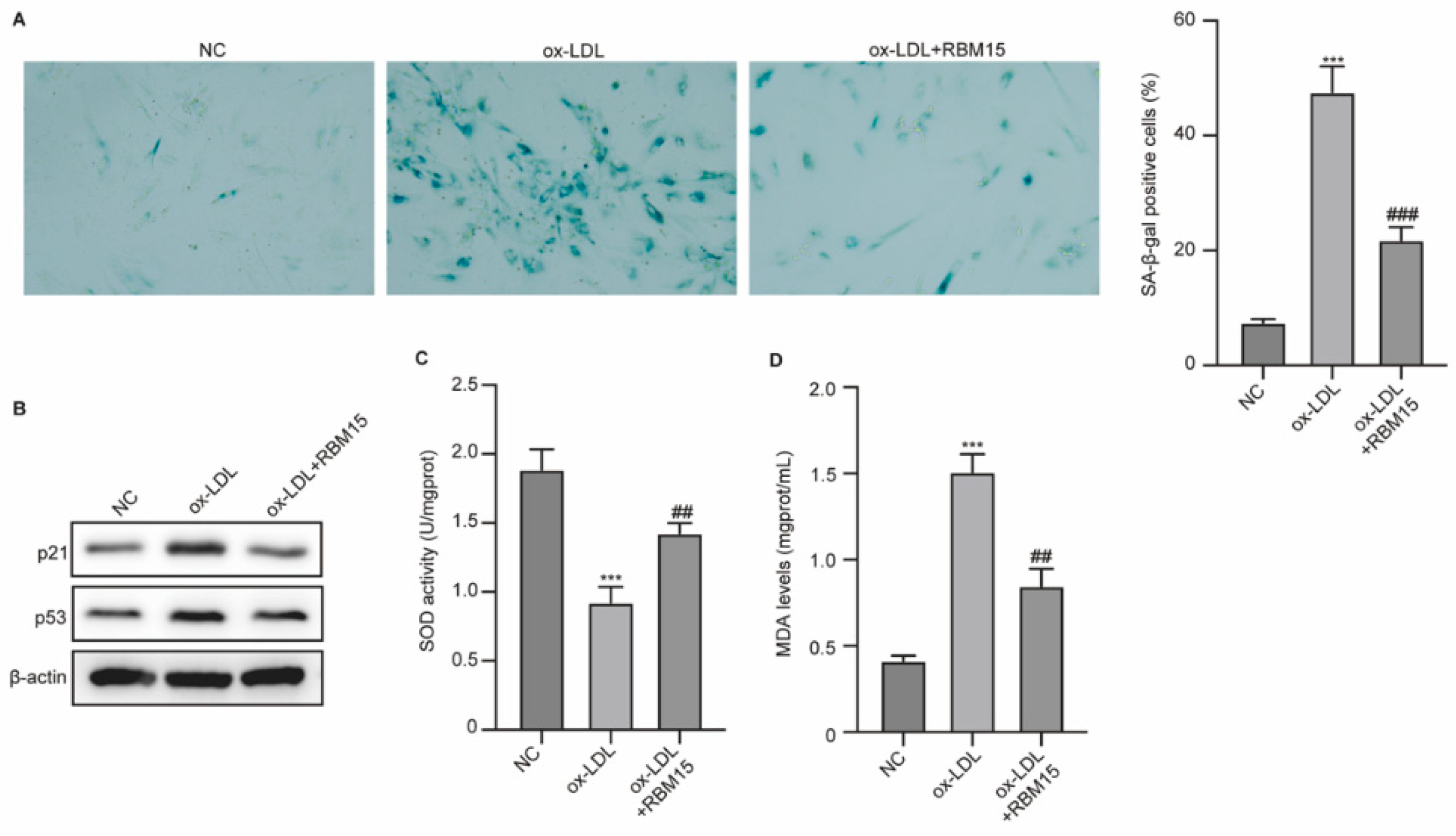

RBM15 Modulates ox-LDL-Induced Senescence of HUVECs

The results from SA-β-Gal staining showed enhanced senescence of HUVECs under ox-LDL induction, and overexpression of RBM15 reversed this effect (

Figure 2A). Moreover, the biomarkers of senescence, including p21 and p53, were notably elevated by ox-LDL and recovered by RBM15 (

Figure 2B). The activity of SOD was reduced, and MDA level was increased by ox-LDL, which was reversed by RBM15 overexpression (

Figure 2C and D). These data indicated that RBM15 modulated the senescence and damages of HUVECs.

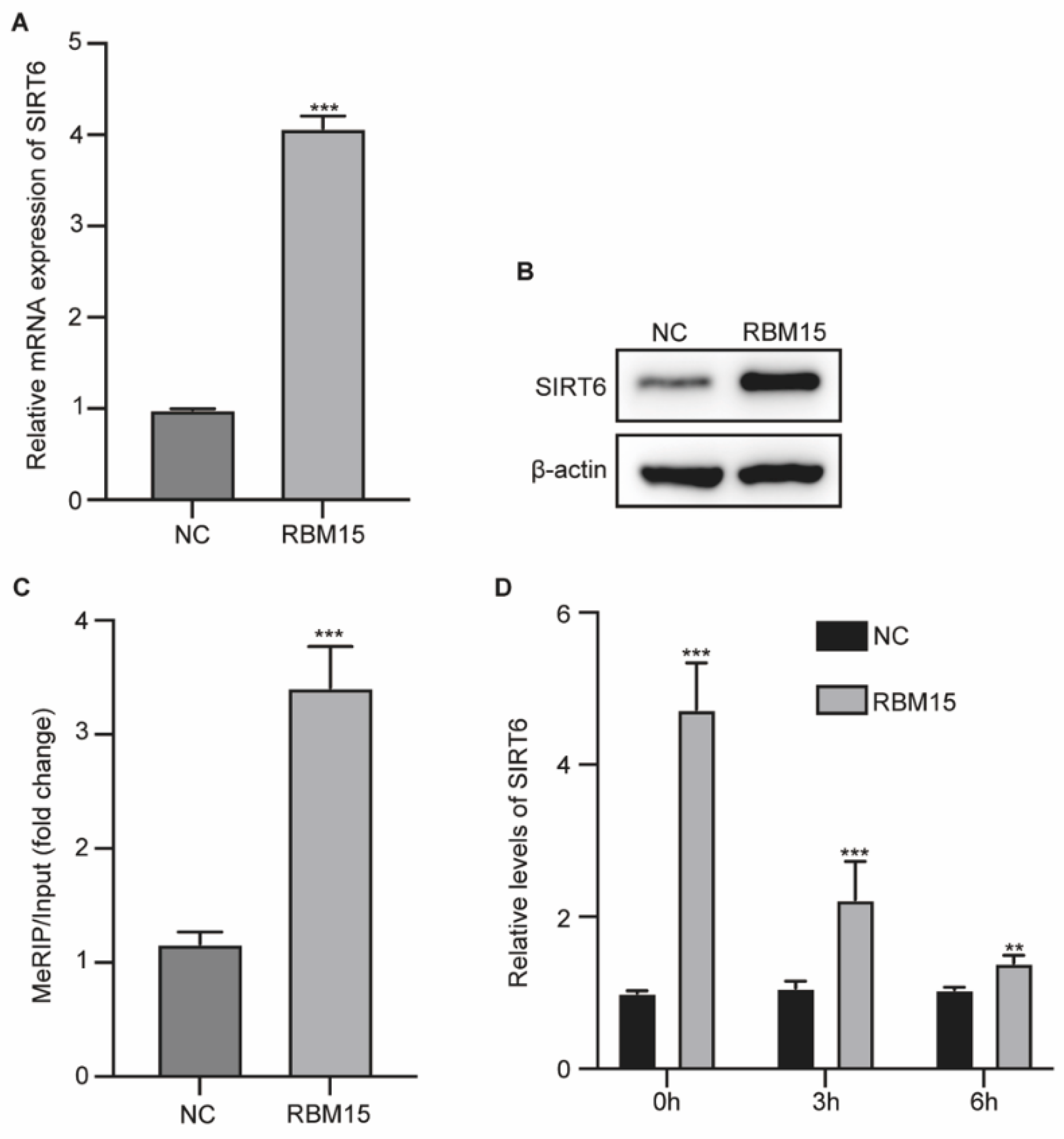

RBM15 Epigenetically Regulates SIRT6 Function in HUVECs

We next explored the potential molecular mechanisms underlying RBM15-regulated HUVEC behaviors. Results from qPCR assay showed that overexpression of RBM15 could elevate the RNA and protein level of SIRT6 in HUVECs (Fig. 3A and B). Analysis by MeRIP-qPCR assay indicated that overexpression of RBM15 elevated the m6A enrichment on SIRT6 mRNA (

Figure 3C). HUVECs were treated with actinomycin D to inhibit mRNA translation, and overexpression of RBM15 elevated the mRNA level of RBM15 and its stability (

Figure 3D). These data indicated that RBM15 regulated the m6A modification of RBM15 in HUVECs.

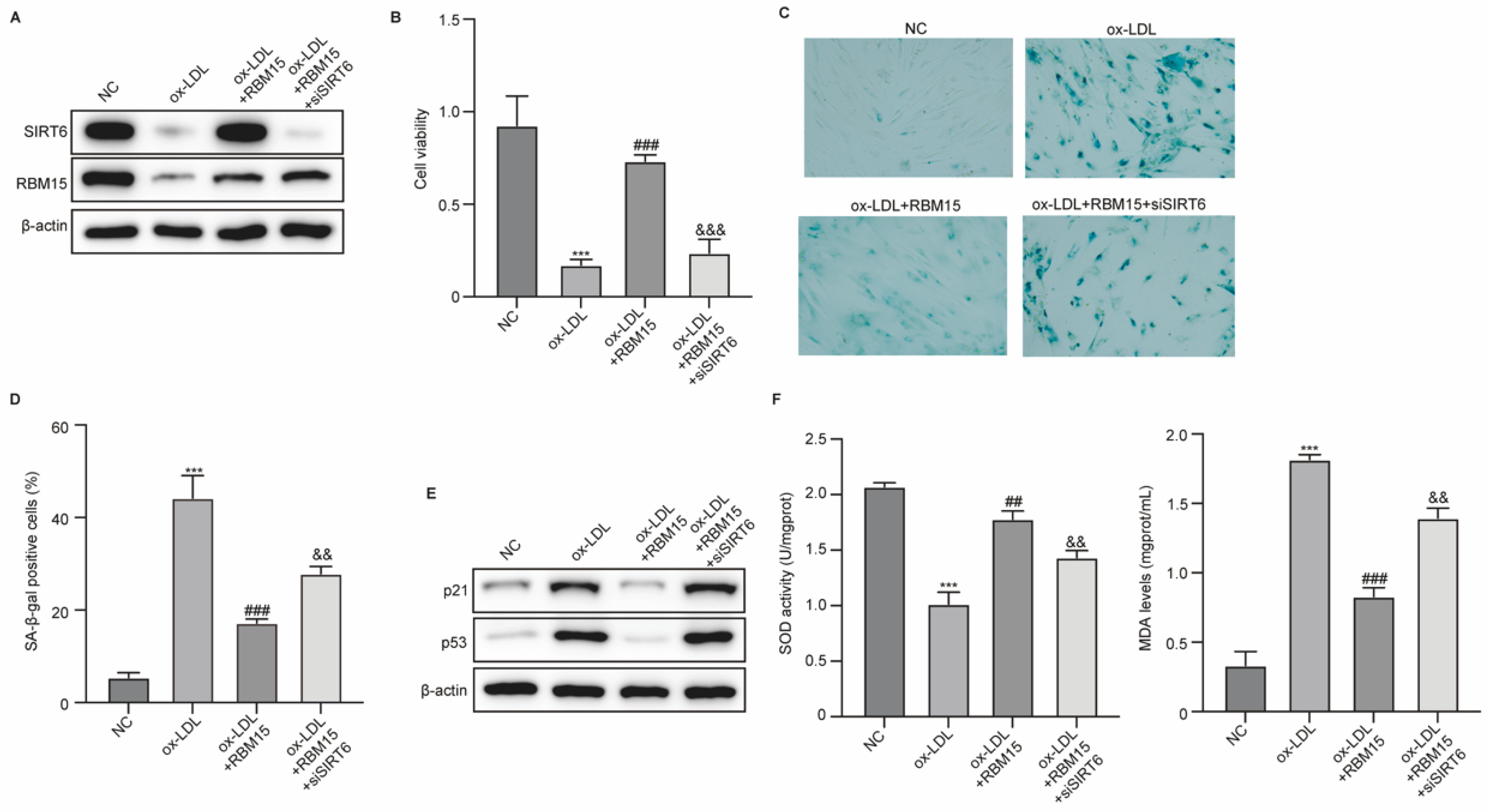

RBM15 Modulates ox-LDL-Induced Damage and Senescence of HUVECs via SIRT6

Subsequently, we determined the role of RBM15/SIRT6 in ox-LDL-induced damage and senescence of HUVECs. HUVECs were induced by ox-LDL and transfected with RBM15 overexpression vectors and siSIRT6. The results from western blot indicated that ox-LDL treatment suppressed expression of RBM15 and SIRT6 in HUVECs, which is reversed by RBM15 overexpression, and siSIRT6 effectively repressed SIRT6 expression caused by RBM15 overexpression in HUVECs (

Figure 4A). Overexpression of RBM15 recovered the viability and reduced senescence of HUVECs caused by ox-LDL, whereas knockdown of SIRT6 abolished these effects (Figure 5B-D). The treatment with siSIRT6 also abolished the RBM15-repressed expression of p21 and p53 (

Figure 4E). Furthermore, RBM15 recovered the activity of SOD and reduced production of MDA in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs, which was reversed by knockdown of SIRT6 (

Figure 4F). These data suggested that SIRT6 mediated the effects of RBM15 on damages and senescence of HUVECs.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that RBM15 alleviated injury and senescence of cells that induced by ox-LDL. The exploration on molecular mechanisms further revealed that RBM15 epigenetically regulated the m6A enrichment on SIRT6 mRNA to enhance its stability and expression. The m6A modification has been identified as one of the post-transcriptional regulatory markers in different types of RNAs [

18]. RNA m6A modification has been documented to play important roles in regulating RNA splicing, translation, stability, translocation, and the high-level structure [

19]. m6A is installed by methyltransferase complex including METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, KIAA1429, METTL16, RBM15, and ZC3H13 [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Numerous studies focusing on m6A RNA methylation have demonstrated that the regulators of m6A RNA methylation are involved in various human diseases [

25]. RBM15 is a writer of methyltransferase that was recently reported to participate in several cancer types. For example, RBM15 is reported to be significantly increased in laryngeal cancer and was associated with unfavorable prognosis [

26]. A tumor typing analysis reported that RBM15 level is significantly higher in osteosarcoma than in the control cell line and RBM15 showed a negative and positive correlation with T cells gamma delta and activated natural killer cells, respectively [

27]. Besides, the knockdown of RBM15 suppressed the proliferation and metastasis and promoted cell apoptosis in the colorectal cancer cell lines [

28]. Here, we determined that RBM15 epigenetically modulated the mRNA stability of SIRT6 and subsequently alleviated the oxidative stress and senescence of HUVECs caused by ox-LDL, and knockdown of SIRT6 abolished the protective effects of RBM15.

Mounting evidence suggests that SIRT6 acts as a multifaceted enzyme, functioning as a deacetylase, mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase, and long fatty deacylase [

29,

30]. It plays integral roles in various cellular signaling pathways, ranging from DNA damage repair in the early stages to disease progression [

31]. SIRT6 is intricately linked to aging, including genomic damage, telomere integrity, and DNA repair mechanisms [

32]. Moreover, it is involved in metabolic processes such as glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, insulin secretion, lipid synthesis, lipolysis, and thermogenesis [

33]. Additionally, SIRT6 plays a crucial role in inflammation and the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, cardiac hypertrophy, heart failure, and ischemia-reperfusion injury [

34,

35]. SIRT6 is markedly reduced in vascular smooth muscle cells in human and mouse atherosclerotic plaques, and overexpression of SIRT6 delayed senescence and downregulated the expression of inflammatory cytokines in vascular smooth muscle cells [

36]. Consistently, our work determined that knockdown of SIRT6 promoted the HUVEC senescence and cell injury.

Conclusion

To summarize, we identified that the methyltransferase RBM15 epigenetically regulated the m6A enrichment of SIRT6 in vascular endothelial cells to alleviate cell injury and senescence. Our findings provided a novel molecular mechanism underlying endothelial cell damage and senescence during atherosclerosis and may provide a novel strategy for atherosclerosis therapy.

Author Contributions

Jing Lin and Jing Tong designed the study, Jing Lin, Tianwen Zhang, Chaoqun Wu performed the experiments, Jing Lin and Jing Tong wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Key Specialized Construction Project in Cardiology Department of Zhejiang Province (2023-SZZ) and Ningbo Key Research and Development Program (2022Z150).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Hartley, A.; Haskard, D.; Khamis, R. Oxidized LDL and anti-oxidized LDL antibodies in atherosclerosis - Novel insights and future directions in diagnosis and therapy<sup/>. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2019, 29, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattoor, A.J.; Pothineni, N.V.K.; Palagiri, D.; Mehta, J.L. Oxidative Stress in Atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2017, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.R.; Sinha, S.; Owens, G.K. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2016, 118, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grootaert, M.O.J.; Moulis, M.; Roth, L.; Martinet, W.; Vindis, C.; Bennett, M.R.; De Meyer, G.R.Y. Vascular smooth muscle cell death, autophagy and senescence in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 2018, 114, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado-Oliveira, G.; Ramos, C.; Marques, A.R.A.; Vieira, O.V. Cell Senescence, Multiple Organelle Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.M.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Q.; Hu, Y.W. The emerging role of cell senescence in atherosclerosis. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020, 59, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunau, C.; Le Luyer, J.; Laporte, M.; Joly, D. The Epigenetics Dilemma. Genes (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Modern epigenetics methods in biological research. Methods 2021, 187, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M.A.; Kouzarides, T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell 2012, 150, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hong, T.; Wang, S.; Mo, J.; Tian, T.; Zhou, X. Epigenetic modification of nucleic acids: from basic studies to medical applications. Chem Soc Rev 2017, 46, 2844–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wu, R.; Ming, L. The role of m6A RNA methylation in cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 112, 108613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, X.; Huang, T.; Zhao, X.; Chen, W.; Gu, N.; Zhang, R. Dynamic landscape and evolution of m6A methylation in human. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, 6251–6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerum, S.; Meynier, V.; Catala, M.; Tisné, C. A comprehensive review of m6A/m6Am RNA methyltransferase structures. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, 7239–7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccara, S.; Ries, R.J.; Jaffrey, S.R. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthiya, R.; Khandelia, P. m6A RNA Methylation: Ramifications for Gene Expression and Human Health. Mol Biotechnol 2020, 62, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Li, L.; Luo, E.; Hou, J.; Yan, G.; Wang, D.; Qiao, Y.; Tang, C. Role of m6A RNA methylation in cardiovascular disease (Review). Int J Mol Med 2020, 46, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Chen, C.; Ji, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, G.; Yuan, W.; Kan, Q.; Sun, Z. The interplay between m6A RNA methylation and noncoding RNA in cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2019, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Kong, S.; Tao, M.; Ju, S. The potential role of RNA N6-methyladenosine in Cancer progression. Mol Cancer 2020, 19, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Lv, R.; Ma, H.; Shen, H.; He, C.; Wang, J.; Jiao, F.; Liu, H.; Yang, P.; Tan, L.; et al. Zc3h13 Regulates Nuclear RNA m(6)A Methylation and Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Mol Cell 2018, 69, 1028–1038.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.P.; Chen, C.K.; Pickering, B.F.; Chow, A.; Jackson, C.; Guttman, M.; Jaffrey, S.R. m(6)A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature 2016, 537, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton, K.E.; Chen, B.; Liu, K.; Hunter, O.V.; Xie, Y.; Tu, B.P.; Conrad, N.K. The U6 snRNA m(6)A Methyltransferase METTL16 Regulates SAM Synthetase Intron Retention. Cell 2017, 169, 824–835.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokar, J.A.; Shambaugh, M.E.; Polayes, D.; Matera, A.G.; Rottman, F.M. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. Rna 1997, 3, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwala, S.D.; Blitzblau, H.G.; Hochwagen, A.; Fink, G.R. RNA methylation by the MIS complex regulates a cell fate decision in yeast. PLoS Genet 2012, 8, e1002732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widagdo, J.; Anggono, V. The m6A-epitranscriptomic signature in neurobiology: from neurodevelopment to brain plasticity. J Neurochem 2018, 147, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tian, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Yan, B.; Yang, L.; Li, Q.; Zhao, R.; Liu, M.; Wang, P.; et al. RBM15 facilitates laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma progression by regulating TMBIM6 stability through IGF2BP3 dependent. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2021, 40, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Qu, H.; Zhan, X.; Liu, D.; Liang, T.; Chen, L.; Huang, S.; Sun, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, T.; et al. Identification of osteosarcoma m6A-related prognostic biomarkers using artificial intelligence: RBM15. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Mei, Y.; Hou, M. Knockdown RBM15 Inhibits Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation and Metastasis Via N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) Modification of MyD88 mRNA. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2022, 37, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J.L.; Baeza, J.; Denu, J.M. Activation of the protein deacetylase SIRT6 by long-chain fatty acids and widespread deacylation by mammalian sirtuins. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 31350–31356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Das, S. SIRT6 deacetylates PKM2 to suppress its nuclear localization and oncogenic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E538–E547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasselli, L.; Zheng, W.; Chua, K.F. SIRT6: Novel Mechanisms and Links to Aging and Disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2017, 28, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnik, S.; Auwerx, J.; Sinclair, D.A.; Matter, C.M. Protective effects of sirtuins in cardiovascular diseases: from bench to bedside. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 3404–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalkiadaki, A.; Guarente, L. Sirtuins mediate mammalian metabolic responses to nutrient availability. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012, 8, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; You, T.; Liu, P. Sirtuin-6 inhibits cardiac fibroblasts differentiation into myofibroblasts via inactivation of nuclear factor κB signaling. Transl Res 2015, 165, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Yin, M.; Koroleva, M.; Mastrangelo, M.A.; Zhang, W.; Bai, P.; Little, P.J.; Jin, Z.G. SIRT6 protects against endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2016, 8, 1064–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootaert, M.O.J.; Finigan, A.; Figg, N.L.; Uryga, A.K.; Bennett, M.R. SIRT6 Protects Smooth Muscle Cells From Senescence and Reduces Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2021, 128, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).