Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Treatment

Cell Transfection

Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK-8)

Insulin Level Detection

Copper Ion Detection

Measurement of a-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase (α-KG) and Pyruvate Acid (PA)

RNA Extraction and qPCR

Western Blotting Assay

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

Statistical Analayis

Results

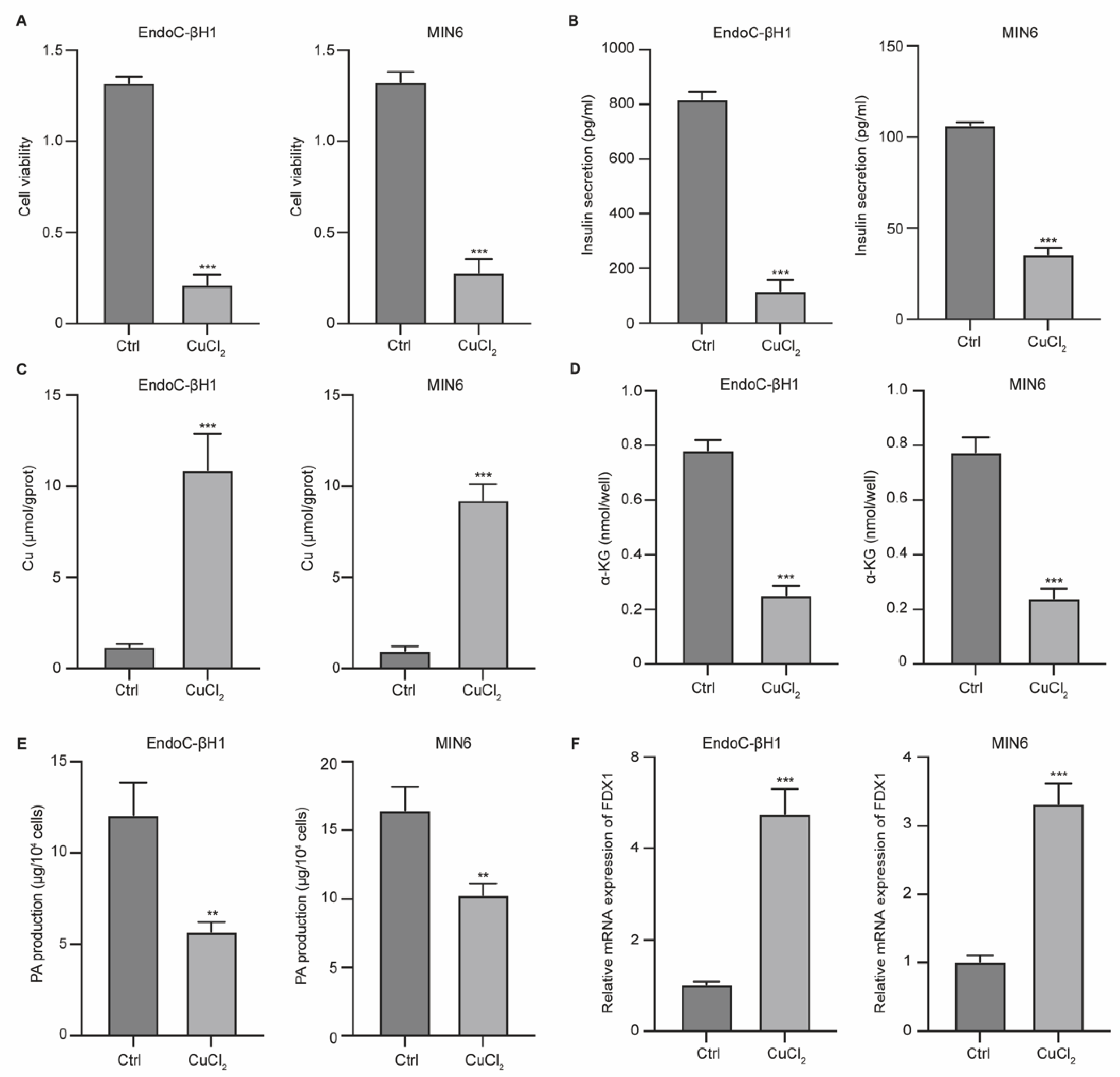

Cuprotosis in Pancreatic β Cells

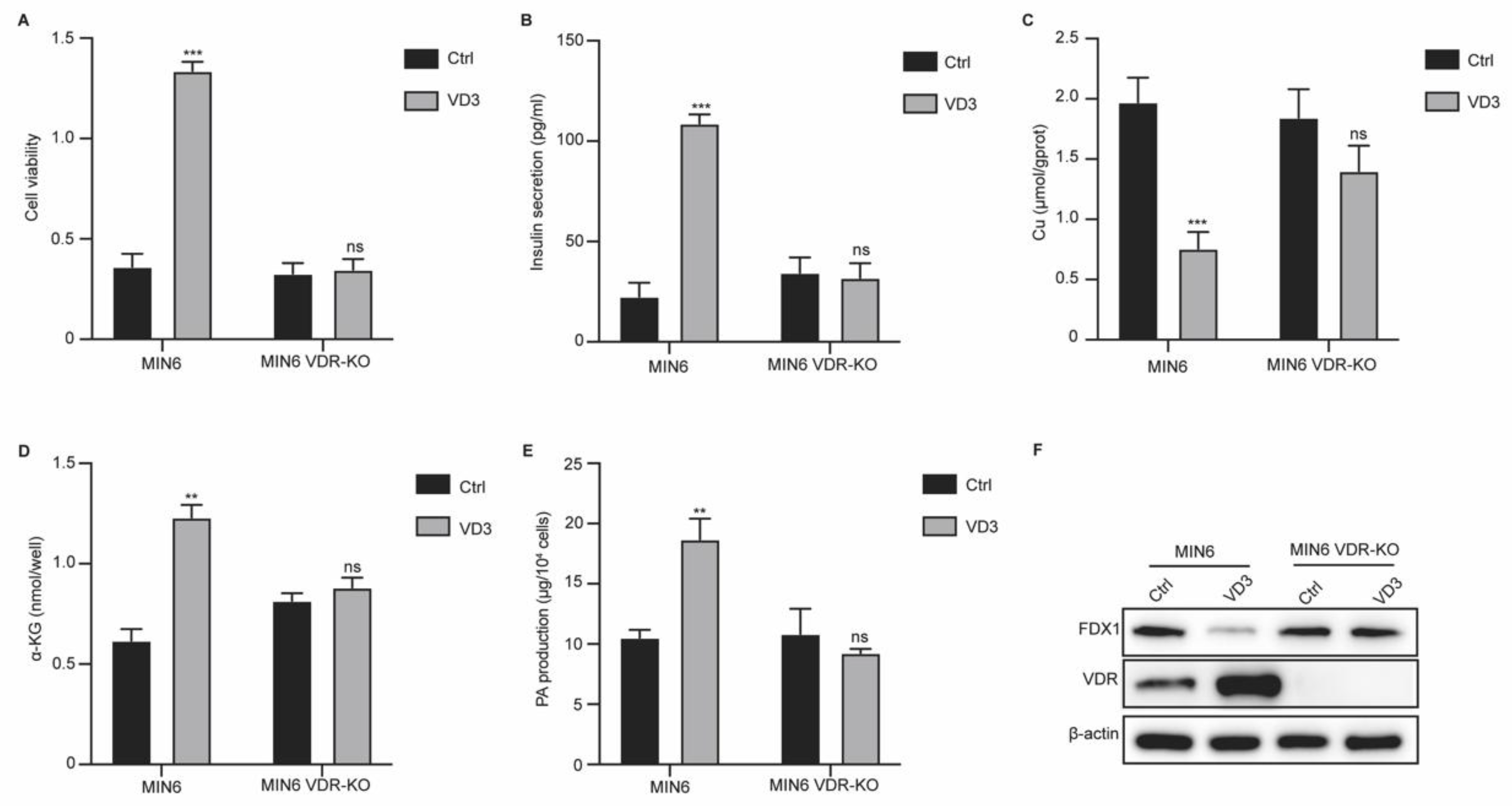

VD3/VDR Regulates Pancreatic β Cells Cuprotosis

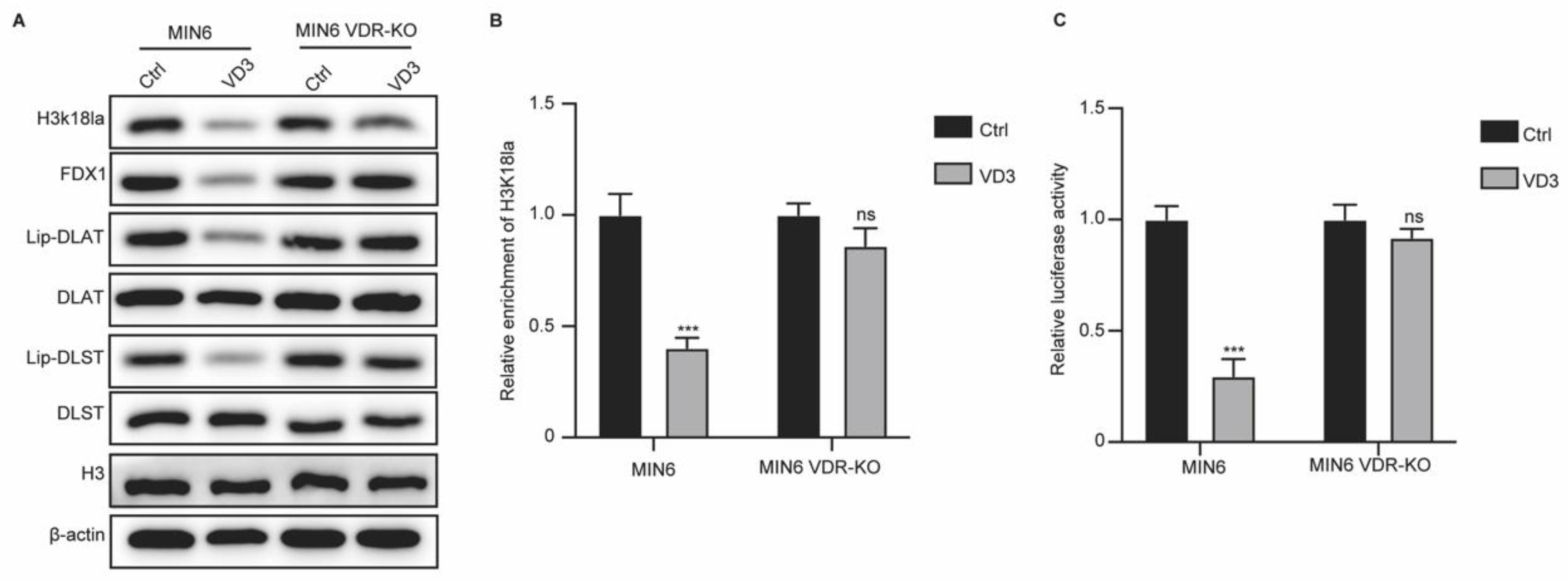

VD3/VDR Axis Regulates FDX1 Expression in Pancreatic β Cells Via Regulating H3K18la Modification

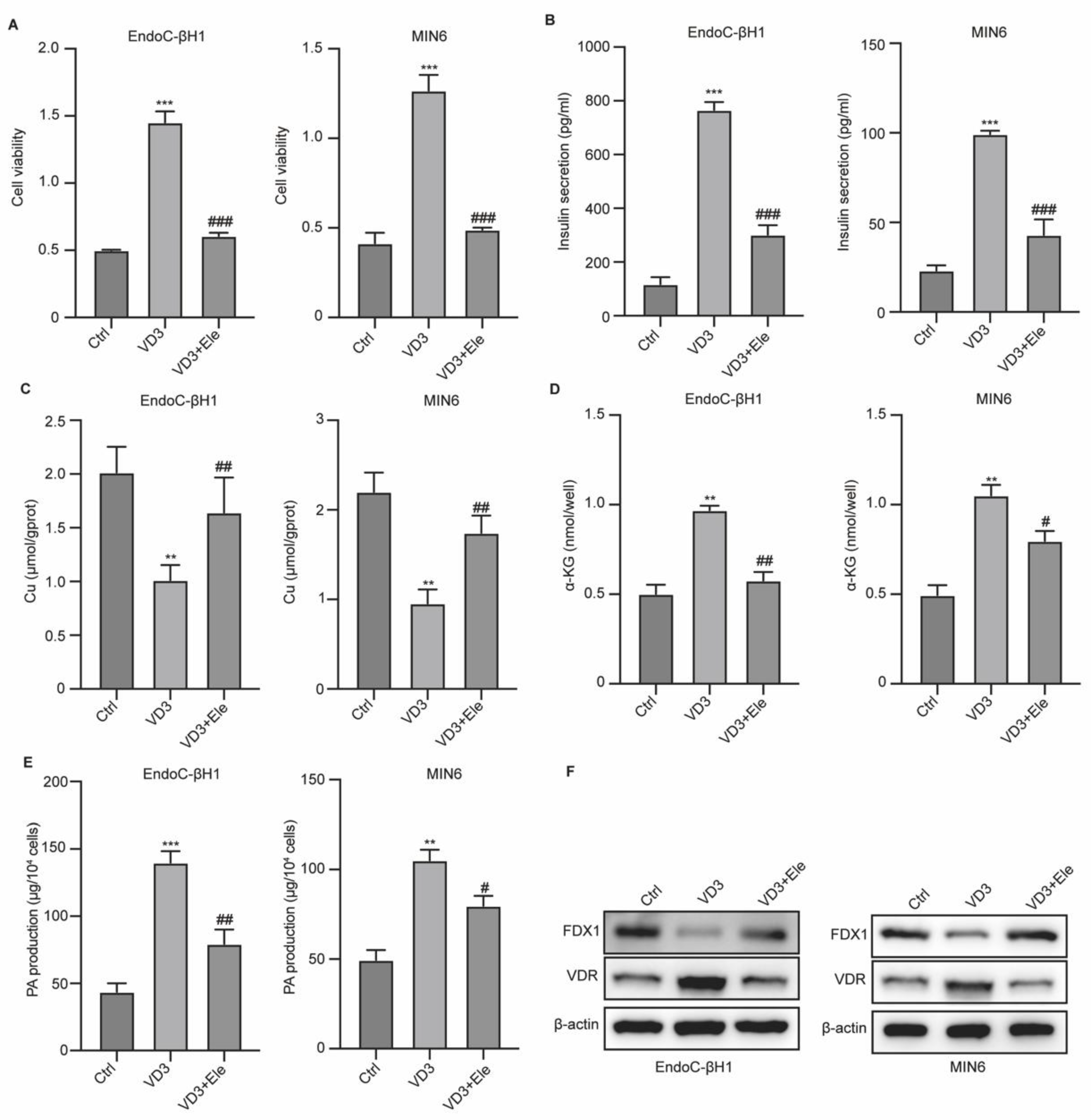

VD3 Affects Pancreatic β Cell Function Via the Regulating Cuprotosis

Discussion

Conclusion

Funding

References

- Chen, T., et al., Ferroptosis and cuproptposis in kidney Diseases: dysfunction of cell metabolism. Apoptosis, 2024. 29(3-4): p. 289-302. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z. and S. Xi, The effects of heavy metals on human metabolism. Toxicol Mech Methods, 2020. 30(3): p. 167-176. [CrossRef]

- Kornblatt, A.P., V.G. Nicoletti, and A. Travaglia, The neglected role of copper ions in wound healing. J Inorg Biochem, 2016. 161: p. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., et al., Copper incorporated biomaterial-based technologies for multifunctional wound repair. Theranostics, 2024. 14(2): p. 547-570. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L., et al., Mitochondrial copper depletion suppresses triple-negative breast cancer in mice. Nat Biotechnol, 2021. 39(3): p. 357-367. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q., et al., Copper in Diabetes Mellitus: a Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Plasma and Serum Studies. Biol Trace Elem Res, 2017. 177(1): p. 53-63. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, H., T. Davoodian, and M.D.L. Johnson, The promise of copper ionophores as antimicrobials. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2023. 75: p. 102355. [CrossRef]

- Huo, S., et al., ATF3/SPI1/SLC31A1 Signaling Promotes Cuproptosis Induced by Advanced Glycosylation End Products in Diabetic Myocardial Injury. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(2). [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., et al., Cuproptosis: mechanisms and links with cancers. Mol Cancer, 2023. 22(1): p. 46. [CrossRef]

- Guo, B., et al., Cuproptosis Induced by ROS Responsive Nanoparticles with Elesclomol and Copper Combined with αPD-L1 for Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Mater, 2023. 35(22): p. e2212267. [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P., et al., Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science, 2022. 375(6586): p. 1254-1261. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., et al., Melatonin ameliorates histone modification disorders in mammalian aged oocytes by neutralizing the alkylation of HDAC1. Free Radic Biol Med, 2023. 208: p. 361-370. [CrossRef]

- Millán-Zambrano, G., et al., Histone post-translational modifications - cause and consequence of genome function. Nat Rev Genet, 2022. 23(9): p. 563-580. [CrossRef]

- Zaib, S., N. Rana, and I. Khan, Histone Modifications and their Role in Epigenetics of Cancer. Curr Med Chem, 2022. 29(14): p. 2399-2411. 10.2174/0929867328666211108105214.

- Zhang, D., et al., Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature, 2019. 574(7779): p. 575-580. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., et al., Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2022. 7(1): p. 305. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.N., et al., Lactylation, a Novel Metabolic Reprogramming Code: Current Status and Prospects. Front Immunol, 2021. 12: p. 688910. [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.Y., et al., Positive feedback regulation of microglial glucose metabolism by histone H4 lysine 12 lactylation in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Metab, 2022. 34(4): p. 634-648.e6. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., et al., Histone lactylation drives oncogenesis by facilitating m(6)A reader protein YTHDF2 expression in ocular melanoma. Genome Biol, 2021. 22(1): p. 85. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W., et al., Lactic acid induces transcriptional repression of macrophage inflammatory response via histone acetylation. Cell Rep, 2024. 43(2): p. 113746. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., et al., Glis1 facilitates induction of pluripotency via an epigenome-metabolome-epigenome signalling cascade. Nat Metab, 2020. 2(9): p. 882-892. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., et al., Risk factors contributing to type 2 diabetes and recent advances in the treatment and prevention. Int J Med Sci, 2014. 11(11): p. 1185-200. [CrossRef]

- Habibian, N., et al., Role of vitamin D and vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms on residual beta cell function in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Rep, 2019. 71(2): p. 282-288. [CrossRef]

- Lips, P., et al., Vitamin D and type 2 diabetes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2017. 173: p. 280-285.

- Wu, M., et al., Vitamin D protects against high glucose-induced pancreatic β-cell dysfunction via AMPK-NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2022. 547: p. 111596. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X., et al., Combination therapy with saxagliptin and vitamin D for the preservation of β-cell function in adult-onset type 1 diabetes: a multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2023. 8(1): p. 158.

- Hu, X., et al., 1,25-(OH)2D3 protects pancreatic beta cells against H2O2-induced apoptosis through inhibiting the PERK-ATF4-CHOP pathway. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai), 2021. 53(1): p. 46-53. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., et al., 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 ameliorates diabetes-induced bone loss by attenuating FoxO1-mediated autophagy. J Biol Chem, 2021. 296: p. 100287. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., et al., 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D attenuates diabetic cardiac autophagy and damage by vitamin D receptor-mediated suppression of FoxO1 translocation. J Nutr Biochem, 2020. 80: p. 108380. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W., et al., 1ɑ,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) promotes osteogenesis by down-regulating FGF23 in diabetic mice. J Cell Mol Med, 2021. 25(8): p. 4148-4156.

- Wang, Q., Five cuprotosis-related lncRNA signatures for prognosis prediction in acute myeloid leukaemia. Hematology, 2023. 28(1): p. 2231737. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., et al., Cuprotosis-related signature predicts overall survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022. 10: p. 922995. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., et al., Machine learning-based characterization of cuprotosis-related biomarkers and immune infiltration in Parkinson's disease. Front Genet, 2022. 13: p. 1010361. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W., et al., Cuprotosis clusters predict prognosis and immunotherapy response in low-grade glioma. Apoptosis, 2024. 29(1-2): p. 169-190. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., et al., FDX1 inhibits thyroid cancer malignant progression by inducing cuprotosis. Heliyon, 2023. 9(8): p. e18655. [CrossRef]

- Lv, X., Y. Lv, and X. Dai, Lactate, histone lactylation and cancer hallmarks. Expert Rev Mol Med, 2023. 25: p. e7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., et al., Histone Lactylation Boosts Reparative Gene Activation Post-Myocardial Infarction. Circ Res, 2022. 131(11): p. 893-908. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).