Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

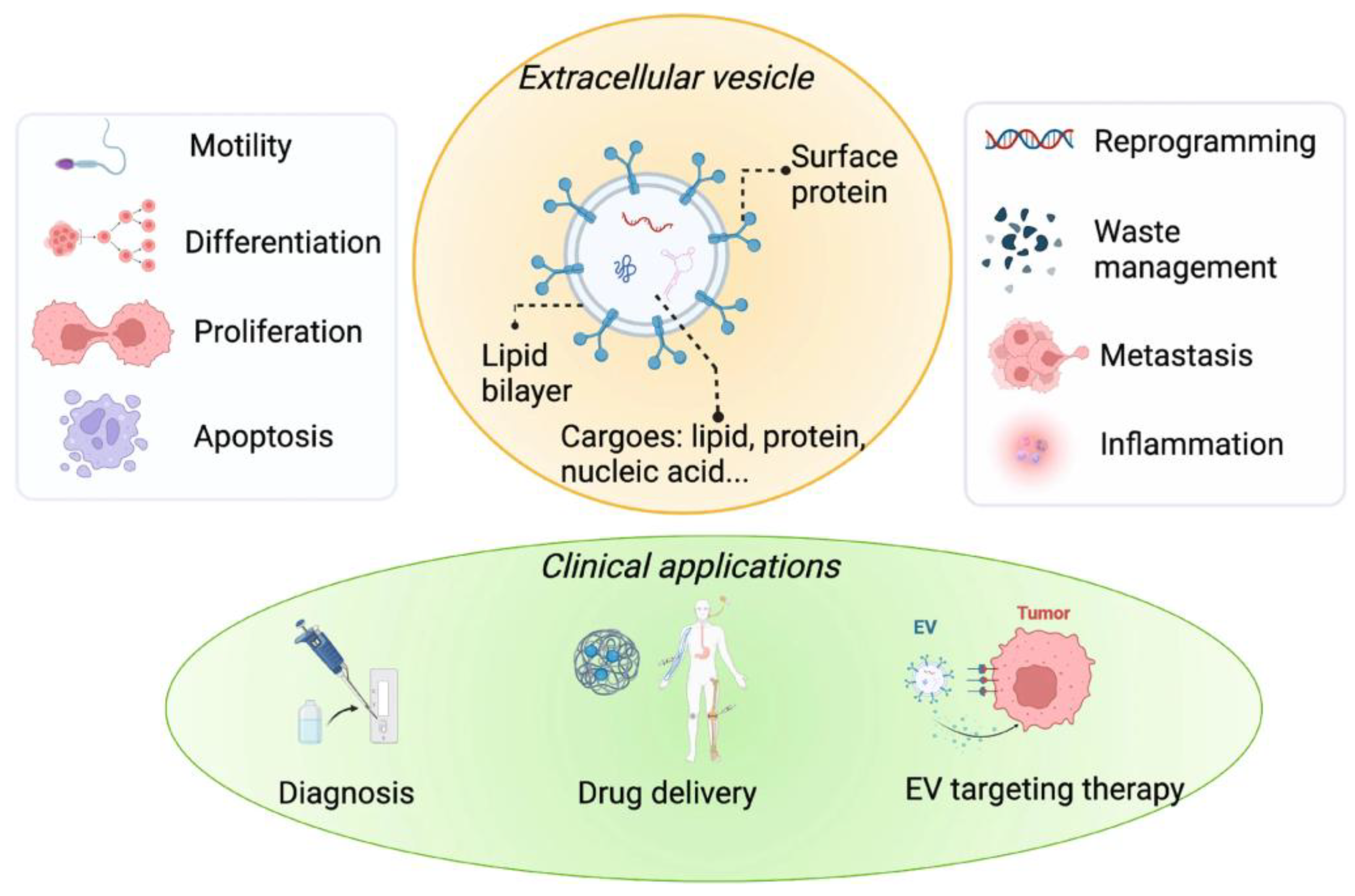

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

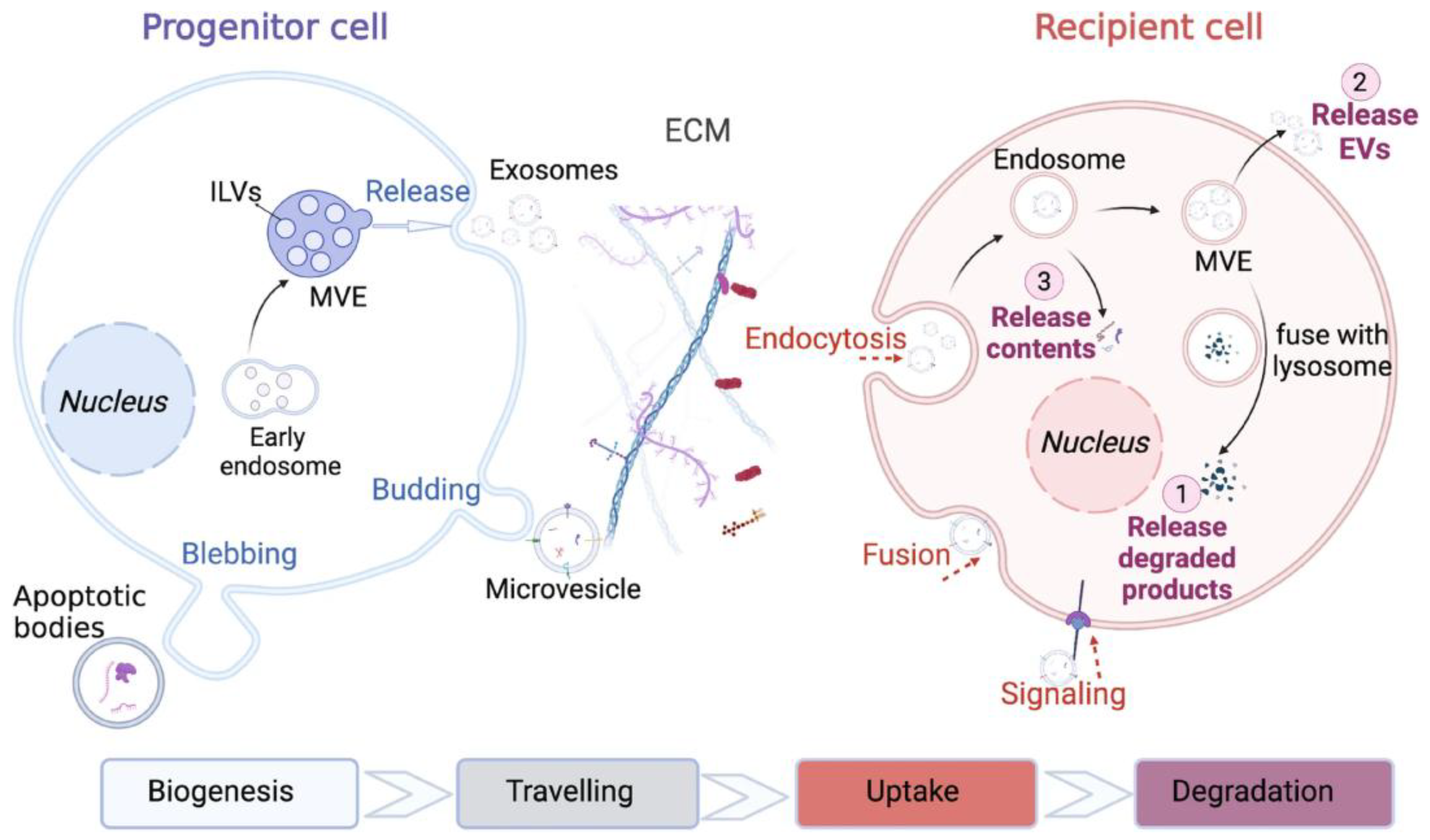

2. Molecular Mechanisms of EV Biogenesis and Cargo Sorting

3. EV-Mediated Intercellular Communication in Disease Microenvironments

4. Pharmacological Targeting of EV Pathways

| Agent/Strategy | Target/Mechanism | Effect on EVs | Application Context | Citation |

| GW4869 | Inhibits neutral sphingomyelinase | Reduces exosome release | Cancer, inflammation | [103] |

| Imipramine | Disrupts endolysosomal trafficking | Blocks exosome secretion | Oncology, neurodegeneration | [104] |

| Monensin | Alters Golgi pH, enhances EV secretion | Promotes EV release | Therapeutic EV production | [105] |

| Forskolin | Activates adenylyl cyclase/cAMP pathway | Increases EV release | Neuroregeneration | [106] |

| Dynasore | Inhibits dynamin-dependent endocytosis | Blocks EV uptake | Prevents EV-mediated signal spread | [107] |

| Trichostatin A | HDAC inhibitor, alters gene expression | Modifies EV cargo | Immunomodulatory EVs | [108] |

| Fenretinide | Inhibits dihydroceramide desaturase (DES1) | Disrupts ceramide-dependent EV release | Antitumor EV suppression | [109] |

| AMPK activators | Modulate cellular metabolism | Downregulate Rab27-mediated secretion | Oncogenic EV suppression | [110] |

| UBL3 modulation | Alters S-prenylation of surface proteins | Reprograms cargo packaging | EV engineering for precision therapy | [62,111] |

5. EVs as Drug Delivery Vehicles and Biomarker Reservoirs

6. EVs in Personalized Medicine and Companion Diagnostics

6.1. Patient-Derived EVs in Cancer Monitoring

6.2. EVs in Targeted Therapy Matching and Disease Profiling

6.3. EVs in Precision Immunotherapy and Patient Stratification

7. Challenges and Future Perspectives in EV-Based Drug Discovery

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| Aβ | Amyloid beta |

| BBB | Blood-Brain Barrier |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CM | Conditioned Medium |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| DC | Dendritic Cell |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| EV | Extracellular Vesicle |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GSC | Glioma Stem Cell |

| GTPase | Guanosine Triphosphatase |

| HNSCC | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| HSP | Heat Shock Protein |

| ILV | Intraluminal Vesicle |

| ISEV | International Society for Extracellular Vesicles |

| KO | Knockout |

| LAMP | Lysosomal-Associated Membrane Protein |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| miR | microRNA (generic notation) |

| MISEV | Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles |

| MSC | Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| siRNA | Small Interfering RNA |

| sEV | Small Extracellular Vesicle |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TNBC | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

| UBL3 | Ubiquitin-Like Protein 3 |

| WT | Wild-Type |

References

- Moghassemi, S.; Dadashzadeh, A.; Sousa, M.J.; Vlieghe, H.; Yang, J.; León-Félix, C.M.; Amorim, C.A. Extracellular Vesicles in Nanomedicine and Regenerative Medicine: A Review over the Last Decade. Bioact Mater 2024, 36, 126–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chronopoulos, A.; Kalluri, R. Emerging Role of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer. Oncogene 2020 39:46 2020, 39, 6951–6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Andaloussi, S.; Mäger, I.; Breakefield, X.O.; Wood, M.J.A. Extracellular Vesicles: Biology and Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2013 12:5 2013, 12, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding Light on the Cell Biology of Extracellular Vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Samuel, M.; Kumar, S.; Mathivanan, S. Ticket to a Bubble Ride: Cargo Sorting into Exosomes and Extracellular Vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 2019, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.M.; Andreu, Z.; Zavec, A.B.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological Properties of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Physiological Functions. J Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Biogenesis, Secretion, and Intercellular Interactions of Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular Vesicles: Exosomes, Microvesicles, and Friends. Journal of Cell Biology 2013, 200, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, L.; Coccè, V.; Bonomi, A.; Ami, D.; Ceccarelli, P.; Ciusani, E.; Viganò, L.; Locatelli, A.; Sisto, F.; Doglia, S.M.; et al. Paclitaxel Is Incorporated by Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Released in Exosomes That Inhibit in Vitro Tumor Growth: A New Approach for Drug Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2014, 192, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roefs, M.T.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; Vader, P. Extracellular Vesicle-Associated Proteins in Tissue Repair. Trends Cell Biol 2020, 30, 990–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamerkar, S.; Lebleu, V.S.; Sugimoto, H.; Yang, S.; Ruivo, C.F.; Melo, S.A.; Lee, J.J.; Kalluri, R. Exosomes Facilitate Therapeutic Targeting of Oncogenic KRAS in Pancreatic Cancer. Nature 2017, 546, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skog, J.; Würdinger, T.; van Rijn, S.; Meijer, D.H.; Gainche, L.; Curry, W.T.; Carter, B.S.; Krichevsky, A.M.; Breakefield, X.O. Glioblastoma Microvesicles Transport RNA and Proteins That Promote Tumour Growth and Provide Diagnostic Biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol 2008, 10, 1470–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, L.M.; Wang, M.Z. Overview of Extracellular Vesicles, Their Origin, Composition, Purpose, and Methods for Exosome Isolation and Analysis. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Hasan, M.M.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Waliullah, A.S.M.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, C.; Oyama, S.; Mimi, M.A.; Tomochika, Y.; et al. UBL3 Interacts with Alpha-Synuclein in Cells and the Interaction Is Downregulated by the EGFR Pathway Inhibitor Osimertinib. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, S.; Zhang, H.; Ferdous, R.; Tomochika, Y.; Chen, B.; Jiang, S.; Islam, M.S.; Hasan, M.M.; Zhai, Q.; Waliullah, A.S.M.; et al. UBL3 Interacts with PolyQ-Expanded Huntingtin Fragments and Modifies Their Intracellular Sorting. Neurol Int 2024, 16, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Erviti, L.; Seow, Y.; Yin, H.; Betts, C.; Lakhal, S.; Wood, M.J.A. Delivery of SiRNA to the Mouse Brain by Systemic Injection of Targeted Exosomes. Nature Biotechnology 2011 29:4 2011, 29, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, M.J.; Klyachko, N.L.; Zhao, Y.; Gupta, R.; Plotnikova, E.G.; He, Z.; Patel, T.; Piroyan, A.; Sokolsky, M.; Kabanov, A. V.; et al. Exosomes as Drug Delivery Vehicles for Parkinson’s Disease Therapy. Journal of Controlled Release 2015, 207, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, Z.H.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y. Extracellular Vesicle Transportation and Uptake by Recipient Cells: A Critical Process to Regulate Human Diseases. Processes (Basel) 2021, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, K.C.; Antonyak, M.A.; Cerione, R.A. Extracellular Vesicle Docking at the Cellular Port: Extracellular Vesicle Binding and Uptake. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2017, 67, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Tesic Mark, M.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour Exosome Integrins Determine Organotropic Metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vader, P.; Mol, E.A.; Pasterkamp, G.; Schiffelers, R.M. Extracellular Vesicles for Drug Delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2016, 106, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.; Guan, Y.; Xie, A.; Yan, Z.; Gao, S.; Li, W.; Rao, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, T. Extracellular Vesicles: A Rising Star for Therapeutics and Drug Delivery. J Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, B.; Gong, H.; Zhang, K.; Lin, Y.; Sun, M. Extracellular Vesicles: Biological Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Transl Neurodegener 2024, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Kahyo, T.; Zhang, H.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, S.; Ji, Q.; Ferdous, R.; Islam, M.S.; Oyama, S.; et al. Alpha-Synuclein Interaction with UBL3 Is Upregulated by Microsomal Glutathione S-Transferase 3, Leading to Increased Extracellular Transport of the Alpha-Synuclein under Oxidative Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyachko, N.L.; Arzt, C.J.; Li, S.M.; Gololobova, O.A.; Batrakova, E. V. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapeutics: Preclinical and Clinical Investigations. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marar, C.; Starich, B.; Wirtz, D. Extracellular Vesicles in Immunomodulation and Tumor Progression. Nature Immunology 2021 22:5 2021, 22, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyfe, J.; Casari, I.; Manfredi, M.; Falasca, M. Role of Lipid Signalling in Extracellular Vesicles-Mediated Cell-to-Cell Communication. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2023, 73, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crewe, C. Energetic Stress-Induced Metabolic Regulation by Extracellular Vesicles. Compr Physiol 2023, 13, 5051–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetler, D.J.; Di Florio, D.N.; Bruno, K.A.; Ikezu, T.; March, K.L.; Cooper, L.T.; Wolfram, J.; Fairweather, D.L. Extracellular Vesicles as Personalized Medicine. Mol Aspects Med 2023, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, E.; Pan, K.; Li, Z. Engineering Extracellular Vesicles for Targeted Therapeutics in Cardiovascular Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024, 11, 1503830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureliano, M.; Maihemuti, M.; Afsana Mimi, M.; Sohag, S.M.; Hasan, M.M. Single-Cell Transcriptomics in Spinal Cord Studies: Progress and Perspectives. BioChem 2025, Vol. 5, Page 16 2025, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, L.; Vassalli, G. Exosomes: Therapy Delivery Tools and Biomarkers of Diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2017, 174, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.; Breyne, K.; Ughetto, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Breakefield, X.O. RNA Delivery by Extracellular Vesicles in Mammalian Cells and Its Applications. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2020 21:10 2020, 21, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluijter, J.P.G.; Davidson, S.M.; Boulanger, C.M.; Buzás, E.I.; De Kleijn, D.P.V.; Engel, F.B.; Giricz, Z.; Hausenloy, D.J.; Kishore, R.; Lecour, S.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles in Diagnostics and Therapy of the Ischaemic Heart: Position Paper from the Working Group on Cellular Biology of the Heart of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc Res 2018, 114, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Cheng, C.; Sun, C.; Cheng, X. Harnessing Engineered Extracellular Vesicles for Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy: Advancements in Cancer Immunotherapy. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2025 44:1 2025, 44, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.E.; de Jong, O.G.; Brouwer, M.; Wood, M.J.; Lavieu, G.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Vader, P. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapeutics: Natural versus Engineered Targeting and Trafficking. Exp Mol Med 2019, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.C.; Jayasinghe, M.K.; Pham, T.T.; Yang, Y.; Wei, L.; Usman, W.M.; Chen, H.; Pirisinu, M.; Gong, J.; Kim, S.; et al. Covalent Conjugation of Extracellular Vesicles with Peptides and Nanobodies for Targeted Therapeutic Delivery. J Extracell Vesicles 2021, 10, e12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeppner, T.R.; Herz, J.; Görgens, A.; Schlechter, J.; Ludwig, A.-K.; Radtke, S.; de Miroschedji, K.; Horn, P.A.; Giebel, B.; Hermann, D.M. Extracellular Vesicles Improve Post-Stroke Neuroregeneration and Prevent Postischemic Immunosuppression. Stem Cells Transl Med 2015, 4, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimi, M.A.; Hasan, M.M.; Takanashi, Y.; Waliullah, A.S.M.; Mamun, M. Al; Chi, Z.; Kahyo, T.; Aramaki, S.; Takatsuka, D.; Koizumi, K.; et al. UBL3 Overexpression Enhances EV-Mediated Achilles Protein Secretion in Conditioned Media of MDA-MB-231 Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2024, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, X.; Kang, L.; Guan, J. Extracellular Vesicles as Therapeutic Modulators of Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focus on Signaling Mechanisms. J Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Pastor, A. Extracellular Vesicles as Mediators of Neuroinflammation in Intercellular and Inter-Organ Crosstalk. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Sadida, H.Q.; Marzooqi, S. Al; Jerobin, J.; Altemani, F.H.; Algehainy, N.; Alanazi, M.A.; Abou-Samra, A.B.; Kumar, R.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles as Tools and Targets in Therapy for Diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024 9:1 2024, 9, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, M.; Xiong, S.; Xiao, N.; Li, J.; He, X.; Xie, J. Recent Progress in Extracellular Vesicle-Based Carriers for Targeted Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sódar, B.W.; Kittel, Á.; Pálóczi, K.; Vukman, K. V.; Osteikoetxea, X.; Szabó-Taylor, K.; Németh, A.; Sperlágh, B.; Baranyai, T.; Giricz, Z.; et al. Low-Density Lipoprotein Mimics Blood Plasma-Derived Exosomes and Microvesicles during Isolation and Detection. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lener, T.; Gimona, M.; Aigner, L.; Börger, V.; Buzas, E.; Camussi, G.; Chaput, N.; Chatterjee, D.; Court, F.A.; del Portillo, H.A.; et al. Applying Extracellular Vesicles Based Therapeutics in Clinical Trials - An ISEV Position Paper. J Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lan, M.; Chen, Y. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV): Ten-Year Evolution (2014–2023). Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ren, L.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Fu, W.; Yi, J.; Wang, J.; Du, G. The Biology, Function, and Applications of Exosomes in Cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021, 11, 2783–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; An, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Yu, M.; Zhang, R.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Q. Controlled Synthesis of Ag2Te@Ag2S Core–Shell Quantum Dots with Enhanced and Tunable Fluorescence in the Second Near-Infrared Window. Small 2020, 16, 2001003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Liu, M.; Mo, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; et al. Trends in the Biological Functions and Medical Applications of Extracellular Vesicles and Analogues. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021, 11, 2114–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Shin, K.J.; Chae, Y.C. Regulation of Cargo Selection in Exosome Biogenesis and Its Biomedical Applications in Cancer. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2024 56:4 2024, 56, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Bai, H.; Ren, L.; Zhang, L. The Role of Exosome and the ESCRT Pathway on Enveloped Virus Infection. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, N.; Kyuuma, M.; Sugamura, K. Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport Proteins in Cancer Pathogenesis, Vesicular Transport, and Non-endosomal Functions. Cancer Sci 2008, 99, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, S.; Perocheau, D.; Touramanidou, L.; Baruteau, J. The Exosome Journey: From Biogenesis to Uptake and Intracellular Signalling. Cell Communication and Signaling 2021 19:1 2021, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Deun, J.; Mestdagh, P.; Sormunen, R.; Cocquyt, V.; Vermaelen, K.; Vandesompele, J.; Bracke, M.; De Wever, O.; Hendrix, A. The Impact of Disparate Isolation Methods for Extracellular Vesicles on Downstream RNA Profiling. J Extracell Vesicles 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, Z.; Yáñez-Mó, M. Tetraspanins in Extracellular Vesicle Formation and Function. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 109543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trajkovic, K.; Hsu, C.; Chiantia, S.; Rajendran, L.; Wenzel, D.; Wieland, F.; Schwille, P.; Brügger, B.; Simons, M. Ceramide Triggers Budding of Exosome Vesicles into Multivesicular Endosomes. Science (1979) 2008, 319, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, Y.; Hiragi, S.; Fukuda, M. Rab Family of Small GTPases: An Updated View on Their Regulation and Functions. FEBS J 2020, 288, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Baixauli, F.; Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Sánchez-Madrid, F.; Mittelbrunn, M. SORTING IT OUT: REGULATION OF EXOSOME LOADING. Semin Cancer Biol 2014, 28, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, M.; Carmo, N.B.; Krumeich, S.; Fanget, I.; Raposo, G.; Savina, A.; Moita, C.F.; Schauer, K.; Hume, A.N.; Freitas, R.P.; et al. Rab27a and Rab27b Control Different Steps of the Exosome Secretion Pathway. Nat Cell Biol 2010, 12, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.F.; Li, W.J.; Hu, K.S.; Gao, J.; Zhai, W.L.; Yang, J.H.; Zhang, S.J. Exosome Biogenesis: Machinery, Regulation, and Therapeutic Implications in Cancer. Mol Cancer 2022, 21, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenquer, M.; Amorim, M.J. Exosome Biogenesis, Regulation, and Function in Viral Infection. Viruses 2015, 7, 5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takanashi, Y.; Kahyo, T.; Kamamoto, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Ping, Y.; Mizuno, K.; Kawase, A.; Koizumi, K.; Satou, M.; et al. Ubiquitin-like 3 as a New Protein-Sorting Factor for Small Extracellular Vesicles. Cell Struct Funct 2022, 47, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ageta, H.; Ageta-Ishihara, N.; Hitachi, K.; Karayel, O.; Onouchi, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kahyo, T.; Hatanaka, K.; Ikegami, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; et al. UBL3 Modification Influences Protein Sorting to Small Extracellular Vesicles. Nature Communications 2018 9:1 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnino, J.M.; Ni, K.; Jin, Y. Post-Translational Modification Regulates Formation and Cargo-Loading of Extracellular Vesicles. Front Immunol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atukorala, I.; Mathivanan, S. The Role of Post-Translational Modifications in Targeting Protein Cargo to Extracellular Vesicles. Subcell Biochem 2021, 97, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Singh, J.; Schekman, R. Two RNA-Binding Proteins Mediate the Sorting of MiR223 from Mitochondria into Exosomes. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, B.; Goettsch, C. Extracellular Vesicles as Delivery Vehicles of Specific Cellular Cargo. Cells 2020, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Sadida, H.Q.; Marzooqi, S. Al; Jerobin, J.; Altemani, F.H.; Algehainy, N.; Alanazi, M.A.; Abou-Samra, A.B.; Kumar, R.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles as Tools and Targets in Therapy for Diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024 9:1 2024, 9, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menck, K.; Sönmezer, C.; Worst, T.S.; Schulz, M.; Dihazi, G.H.; Streit, F.; Erdmann, G.; Kling, S.; Boutros, M.; Binder, C.; et al. Neutral Sphingomyelinases Control Extracellular Vesicles Budding from the Plasma Membrane. J Extracell Vesicles 2017, 6, 1378056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthikumar, S.; Gangoda, L.; Liem, M.; Fonseka, P.; Atukorala, I.; Ozcitti, C.; Mechler, A.; Adda, C.G.; Ang, C.S.; Mathivanan, S. Proteogenomic Analysis Reveals Exosomes Are More Oncogenic than Ectosomes. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 15375–15396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, H.W.; Michael, M.Z.; Gleadle, J.M. Hypoxic Enhancement of Exosome Release by Breast Cancer Cells. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelbrunn, M.; Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Villarroya-Beltri, C.; González, S.; Sánchez-Cabo, F.; González, M.Á.; Bernad, A.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. Unidirectional Transfer of MicroRNA-Loaded Exosomes from T Cells to Antigen-Presenting Cells. Nature Communications 2011 2:1 2011, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budnik, V.; Ruiz-Cañada, C.; Wendler, F. Extracellular Vesicles Round off Communication in the Nervous System. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2016 17:3 2016, 17, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.J.; Wang, C. A Review of the Regulatory Mechanisms of Extracellular Vesicles-Mediated Intercellular Communication. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023 21:1 2023, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Vila, M.; Yoshioka, Y.; Ochiya, T. Biological Functions Driven by MRNAs Carried by Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sang, R.; Wang, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, W. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Regulate Cancer Progression in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 8, 796385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurj, A.; Zanoaga, O.; Braicu, C.; Lazar, V.; Tomuleasa, C.; Irimie, A.; Berindan-neagoe, I. A Comprehensive Picture of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Contents. Molecular Transfer to Cancer Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sang, R.; Wang, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, W. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Regulate Cancer Progression in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 8, 796385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Montermini, L.; Kim, D.K.; Meehan, B.; Roth, F.P.; Rak, J. The Impact of Oncogenic EGFRvIII on the Proteome of Extracellular Vesicles Released from Glioblastoma Cells. Mol Cell Proteomics 2018, 17, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, S.E.; Nowicki, M.O.; Ricklefs, F.L.; Chiocca, E.A. Immune Escape Mediated by Exosomal PD-L1 in Cancer. Adv Biosyst 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, S.; Pucci, M.; Alessandro, R.; Fontana, S. Extracellular Vesicles and Tumor-Immune Escape: Biological Functions and Clinical Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiovine, C.; Digifico, E.; Anfray, C.; Ummarino, A.; Andón, F.T. Targeting Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Anti-Cancer Therapies: Convincing the Traitors to Do the Right Thing. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.A.; Mehraj, U. Double-Crosser of the Immune System: Macrophages in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Current Immunology Reviews (Discontinued) 2019, 15, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Tesic Mark, M.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour Exosome Integrins Determine Organotropic Metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, T. Pathogenic and Protective Roles of Extracellular Vesicles in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J Biochem 2021, 169, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.S. Extracellular Vesicles in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Double-Edged Sword. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine 2017 14:6 2017, 14, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Li, X. dong; Zhang, S. miao; Wang, H. wei; Wang, Y. liang Extracellular Vesicles in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Insights and New Perspectives. Genes Dis 2021, 8, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.F. Extracellular Vesicles and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Journal of Neuroscience 2019, 39, 9269–9273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghav, A.; Singh, M.; Jeong, G.B.; Giri, R.; Agarwal, S.; Kala, S.; Gautam, K.A. Extracellular Vesicles in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 1061076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyarce, K.; Cepeda, M.Y.; Lagos, R.; Garrido, C.; Vega-Letter, A.M.; Garcia-Robles, M.; Luz-Crawford, P.; Elizondo-Vega, R. Neuroprotective and Neurotoxic Effects of Glial-Derived Exosomes. Front Cell Neurosci 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, M.; Bonetto, V. Extracellular Vesicles and a Novel Form of Communication in the Brain. Front Neurosci 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggio, M.; Hu, T.; Pai, C.C.; Chu, B.; Belair, C.D.; Chang, A.; Montabana, E.; Lang, U.E.; Fu, Q.; Fong, L.; et al. Suppression of Exosomal PD-L1 Induces Systemic Anti-Tumor Immunity and Memory. Cell 2019, 177, 414–427.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernek, L.; Düchler, M. Functions of Cancer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Immunosuppression. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2017, 65, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, P.D.; Morelli, A.E. Regulation of Immune Responses by Extracellular Vesicles. Nature Reviews Immunology 2014 14:3 2014, 14, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, A.L.; Baxter, A.A.; Poon, I.K.H. Gift Bags from the Sentinel Cells of the Immune System: The Diverse Role of Dendritic Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. J Leukoc Biol 2022, 111, 903–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, E.S.; Ginini, L.; Gil, Z. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Metabolic Reprogramming of the Tumor Microenvironment. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encarnação, C.C.; Faria, G.M.; Franco, V.A.; Botelho, L.G.X.; Moraes, J.A.; Renovato-Martins, M. Interconnections within the Tumor Microenvironment: Extracellular Vesicles as Critical Players of Metabolic Reprogramming in Tumor Cells. J Cancer Metastasis Treat 2024;10:28. 2024, 10, N/A-N/A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Hu, D.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, T.; Wang, X. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Regulate Macrophage Polarization: Role and Therapeutic Perspectives. Front Immunol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, F.; Xia, Y.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Zhong, T.; Wang, X. Research Progress on Astrocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Rev Neurosci 2024, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, L.; Banciu, M. Intercellular Crosstalk Via Extracellular Vesicles in Tumor Milieu as Emerging Therapies for Cancer Progression. Curr Pharm Des 2019, 25, 1980–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Hu, Y.; Yan, W. Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Interorgan Communication in Metabolic Diseases. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2023, 34, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulcahy, L.A.; Pink, R.C.; Raul, D.; Carter, F.; David, D.; Carter, R.F. Routes and Mechanisms of Extracellular Vesicle Uptake. J Extracell Vesicles 2014, 3, 24641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Ru, Z.; Xiao, W.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, C.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H. Adipose Tissue Browning in Cancer-Associated Cachexia Can Be Attenuated by Inhibition of Exosome Generation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 506, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, M.; Kim, S.; Singh, S.; Kridel, S.J.; Deep, G. Role of Extracellular Vesicles Secretion in Paclitaxel Resistance of Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Drug Resistance 2022, 5, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, K.; Lu, Y.; Sun, B.; Sun, J.; Liang, W. Monensin Enhanced Generation of Extracellular Vesicles as Transfersomes for Promoting Tumor Penetration of Pyropheophorbide-a from Fusogenic Liposome. Nano Lett 2022, 22, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erwin, N.; Serafim, M.F.; He, M. Enhancing the Cellular Production of Extracellular Vesicles for Developing Therapeutic Applications. Pharm Res 2022, 40, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Du, Z.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, J. Endocytic Pathway Inhibition Attenuates Extracellular Vesicle-Induced Reduction of Chemosensitivity to Bortezomib in Multiple Myeloma Cells. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, K.; Brunet, M.Y.; Fernandez-Rhodes, M.; Williams, S.; Heaney, L.M.; Gethings, L.A.; Federici, A.; Davies, O.G.; Hoey, D.; Cox, S.C. Epigenetic Reprogramming Enhances the Therapeutic Efficacy of Osteoblast-Derived Extracellular Vesicles to Promote Human Bone Marrow Stem Cell Osteogenic Differentiation. J Extracell Vesicles 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WO2021046550A1 - Extracellular Vesicle-Fenretinide Compositions, Extracellular Vesicle-c-Kit Inhibitor Compositions, Methods of Making and Uses Thereof - Google Patents. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2021046550A1/en (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Arkwright, R.; Deshmukh, R.; Adapa, N.; Stevens, R.; Zonder, E.; Zhang, Z.; Farshi, P.; Ahmed, R.; El-Banna, H.; Chan, T.-H.; et al. Lessons from Nature: Sources and Strategies for Developing AMPK Activators for Cancer Chemotherapeutics. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2015, 15, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Waliullah, A.S.M.; Aramaki, S.; Ping, Y.; Takanashi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhai, Q.; Yan, J.; Oyama, S.; et al. A New Potential Therapeutic Target for Cancer in Ubiquitin-Like Proteins—UBL3. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essandoh, K.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Qin, D.; Hao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zingarelli, B.; Peng, T.; Fan, G.C. Blockade of Exosome Generation with GW4869 Dampens the Sepsis-Induced Inflammation and Cardiac Dysfunction. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1852, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menck, K.; Sönmezer, C.; Worst, T.S.; Schulz, M.; Dihazi, G.H.; Streit, F.; Erdmann, G.; Kling, S.; Boutros, M.; Binder, C.; et al. Neutral Sphingomyelinases Control Extracellular Vesicles Budding from the Plasma Membrane. J Extracell Vesicles 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, M.; O’Driscoll, L. Inhibiting Extracellular Vesicles Formation and Release: A Review of EV Inhibitors. J Extracell Vesicles 2019, 9, 1703244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Breyne, K.; Ughetto, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Breakefield, X.O. RNA Delivery by Extracellular Vesicles in Mammalian Cells and Its Applications. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2020 21:10 2020, 21, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, K.; Lu, Y.; Sun, B.; Sun, J.; Liang, W. Monensin Enhanced Generation of Extracellular Vesicles as Transfersomes for Promoting Tumor Penetration of Pyropheophorbide-a from Fusogenic Liposome. Nano Lett 2022, 22, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Song, H.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Ren, X.; Wang, X. Promotion or Inhibition of Extracellular Vesicle Release: Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 340, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson Cullison, S.R.; Flemming, J.P.; Karagoz, K.; Wermuth, P.J.; Mahoney, M.G. Mechanisms of Extracellular Vesicle Uptake and Implications for the Design of Cancer Therapeutics. Journal of extracellular biology 2024, 3, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lener, T.; Gimona, M.; Aigner, L.; Börger, V.; Buzas, E.; Camussi, G.; Chaput, N.; Chatterjee, D.; Court, F.A.; del Portillo, H.A.; et al. Applying Extracellular Vesicles Based Therapeutics in Clinical Trials - An ISEV Position Paper. J Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageta, H.; Ageta-Ishihara, N.; Hitachi, K.; Karayel, O.; Onouchi, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kahyo, T.; Hatanaka, K.; Ikegami, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; et al. UBL3 Modification Influences Protein Sorting to Small Extracellular Vesicles. Nat Commun 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Waliullah, A.S.M.; Aramaki, S.; Ping, Y.; Takanashi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhai, Q.; Yan, J.; Oyama, S.; et al. A New Potential Therapeutic Target for Cancer in Ubiquitin-Like Proteins—UBL3. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, Vol. 24, Page 1231 2023, 24, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, A.C.; Dawson, T.R.; Di Vizio, D.; Weaver, A.M. Context-Specific Regulation of Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Cargo Selection. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2023 24:7 2023, 24, 454–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, P.; Vardaki, I.; Occhionero, A.; Panaretakis, T. Metabolic and Signaling Functions of Cancer Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 2016, 326, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, J.E.J.; Barbeau, L.M.O.; Ju, J.; Savelkouls, K.G.; Bouwman, F.G.; Zonneveld, M.I.; Bronckaers, A.; Kampen, K.R.; Keulers, T.G.H.; Rouschop, K.M.A. Cancer EV Stimulate Endothelial Glycolysis to Fuel Protein Synthesis via MTOR and AMPKα Activation. J Extracell Vesicles 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, M.; O’Driscoll, L. Inhibiting Extracellular Vesicles Formation and Release: A Review of EV Inhibitors. J Extracell Vesicles 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.M.; Bikman, B.T.; Wang, L.; Ying, L.; Reinhardt, E.; Shui, G.; Wenk, M.R.; Summers, S.A. Ablation of Dihydroceramide Desaturase Confers Resistance to Etoposide-Induced Apoptosis In Vitro. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Kumarasamy, R.V.; Pei, J.J.; Raju, K.; Kanniappan, G.V.; Palanisamy, C.P.; Mironescu, I.D. Integrating Engineered Nanomaterials with Extracellular Vesicles: Advancing Targeted Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications. Frontiers in Nanotechnology 2024, 6, 1513683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.P.K.; Holme, M.N.; Stevens, M.M. Re-Engineering Extracellular Vesicles as Smart Nanoscale Therapeutics. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremersch, S.; De Smedt, S.C.; Raemdonck, K. Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications of Extracellular Vesicles. Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 244, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Guan, Y.; Xie, A.; Yan, Z.; Gao, S.; Li, W.; Rao, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, T. Extracellular Vesicles: A Rising Star for Therapeutics and Drug Delivery. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2023 21:1 2023, 21, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Jones, T.W.; Dutta, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Narayanan, S.P.; Fagan, S.C.; Zhang, D. Overview and Update on Methods for Cargo Loading into Extracellular Vesicles. Processes 2021, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Godbout, K.; Lamothe, G.; Tremblay, J.P. CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Strategies with Engineered Extracellular Vesicles. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2023, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutaria, D.S.; Badawi, M.; Phelps, M.A.; Schmittgen, T.D. Achieving the Promise of Therapeutic Extracellular Vesicles: The Devil Is in Details of Therapeutic Loading. Pharm Res 2017, 34, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, K.; McConnell, R.E.; Xu, K.; Lewis, N.D.; Haupt, S.; Youniss, M.R.; Martin, S.; Sia, C.L.; McCoy, C.; Moniz, R.J.; et al. A Versatile Platform for Generating Engineered Extracellular Vesicles with Defined Therapeutic Properties. Molecular Therapy 2021, 29, 1729–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Ye, Z.; Xu, J. Engineering Extracellular Vesicles as Delivery Systems in Therapeutic Applications. Advanced Science 2023, 10, 2300552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, R.; Wu, X.; Sun, Y.; Yao, M.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Gu, J. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Peptide Ligand of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor for Targeted Delivery of Therapeutics. The FASEB Journal 2005, 19, 1978–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.; Busatto, S.; Pham, A.; Tian, M.; Suh, A.; Carson, K.; Quintero, A.; Lafrence, M.; Malik, H.; Santana, M.X.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Treatment. Theranostics 2019, 9, 8001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Pei, F.; Zeng, C.; Yao, Y.; Liao, W.; Zhao, Z. Extracellular Vesicles in Liquid Biopsies: Potential for Disease Diagnosis. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 6611244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revenfeld, A.L.S.; Bæk, R.; Nielsen, M.H.; Stensballe, A.; Varming, K.; Jørgensen, M. Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential of Extracellular Vesicles in Peripheral Blood. Clin Ther 2014, 36, 830–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukouris, S.; Mathivanan, S. Exosomes in Bodily Fluids Are a Highly Stable Resource of Disease Biomarkers. Proteomics Clin Appl 2015, 9, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, Y.; Kosaka, N.; Konishi, Y.; Ohta, H.; Okamoto, H.; Sonoda, H.; Nonaka, R.; Yamamoto, H.; Ishii, H.; Mori, M.; et al. Ultra-Sensitive Liquid Biopsy of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles Using ExoScreen. Nature Communications 2014 5:1 2014, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtzman, J.; Lee, H. Emerging Role of Extracellular Vesicles in the Respiratory System. Exp Mol Med 2020, 52, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.G.; Gray, E.; Heman-Ackah, S.M.; Mäger, I.; Talbot, K.; El Andaloussi, S.; Wood, M.J.; Turner, M.R. Extracellular Vesicles in Neurodegenerative Disease — Pathogenesis to Biomarkers. Nature Reviews Neurology 2016 12:6 2016, 12, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D.A.; Vader, P. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Hybrid Systems for Advanced Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducrot, C.; Loiseau, S.; Wong, C.; Madec, E.; Volatron, J.; Piffoux, M. Hybrid Extracellular Vesicles for Drug Delivery. Cancer Lett 2023, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, L.; Li, I.T.S. Targeting Capabilities of Native and Bioengineered Extracellular Vesicles for Drug Delivery. Bioengineering 2022, Vol. 9, Page 496 2022, 9, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Hu, J.; Shi, J.; Lee, L.J. Stimuli-Responsive Carriers for Controlled Intracellular Drug Release. Curr Med Chem 2019, 26, 2377–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, M.H.; Caires, H.R.; Ābols, A.; Xavier, C.P.R.; Linē, A. Extracellular Vesicles as a Novel Source of Biomarkers in Liquid Biopsies for Monitoring Cancer Progression and Drug Resistance. Drug Resistance Updates 2019, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayamajhi, S.; Sipes, J.; Tetlow, A.L.; Saha, S.; Bansal, A.; Godwin, A.K. Extracellular Vesicles as Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers across the Cancer Journey: From Early Detection to Recurrence. Clin Chem 2024, 70, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paproski, R.J.; Pink, D.; Sosnowski, D.L.; Vasquez, C.; Lewis, J.D. Building Predictive Disease Models Using Extracellular Vesicle Microscale Flow Cytometry and Machine Learning. Mol Oncol 2023, 17, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Fu, Y.; Liu, G.; Shu, B.; Davis, J.; Tofaris, G.K. Multiplexed Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles for Biomarker Development. Nanomicro Lett 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.E. Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer Therapy. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 86, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, M.H.; Caires, H.R.; Ābols, A.; Xavier, C.P.R.; Linē, A. Extracellular Vesicles as a Novel Source of Biomarkers in Liquid Biopsies for Monitoring Cancer Progression and Drug Resistance. Drug Resistance Updates 2019, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, T.; Sumrin, A.; Bilal, M.; Bashir, H.; Khawar, M.B. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Potential Tool for Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy. Saudi J Biol Sci 2022, 29, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2023): From Basic to Advanced Approaches. J Extracell Vesicles 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, Y.; Kosaka, N.; Konishi, Y.; Ohta, H.; Okamoto, H.; Sonoda, H.; Nonaka, R.; Yamamoto, H.; Ishii, H.; Mori, M.; et al. Ultra-Sensitive Liquid Biopsy of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles Using ExoScreen. Nature Communications 2014 5:1 2014, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Herrero, E.; Campos-Silva, C.; Cáceres-Martell, Y.; Robado De Lope, L.; Sanz-Moreno, S.; Serna-Blasco, R.; Rodríguez-Festa, A.; Ares Trotta, D.; Martín-Acosta, P.; Patiño, C.; et al. ALK-Fusion Transcripts Can Be Detected in Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) from Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer Cell Lines and Patient Plasma: Toward EV-Based Noninvasive Testing. Clin Chem 2022, 68, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, E.; Owen, S.; Prantzalos, E.; Radomski, A.; Carman, N.; Lo, T.W.; Zeinali, M.; Subramanian, C.; Ramnath, N.; Nagrath, S. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations Carried in Extracellular Vesicle-Derived Cargo Mirror Disease Status in Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 724389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova-Salas, I.; Aguilar, D.; Cordoba-Terreros, S.; Agundez, L.; Brandariz, J.; Herranz, N.; Mas, A.; Gonzalez, M.; Morales-Barrera, R.; Sierra, A.; et al. Circulating Tumor Extracellular Vesicles to Monitor Metastatic Prostate Cancer Genomics and Transcriptomic Evolution. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1301–1312.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciani, Y.; Nardella, C.; Demichelis, F. Casting a Wider Net: The Clinical Potential of EV Transcriptomics in Multi-Analyte Liquid Biopsy. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miguel-Perez, D.; Russo, A.; Arrieta, O.; Ak, M.; Barron, F.; Gunasekaran, M.; Mamindla, P.; Lara-Mejia, L.; Peterson, C.B.; Er, M.E.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle PD-L1 Dynamics Predict Durable Response to Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors and Survival in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research 2022, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, M.; Hu, T.; Pai, C.C.; Chu, B.; Belair, C.D.; Chang, A.; Montabana, E.; Lang, U.E.; Fu, Q.; Fong, L.; et al. Suppression of Exosomal PD-L1 Induces Systemic Anti-Tumor Immunity and Memory. Cell 2019, 177, 414–427.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchetti, D.; Zurlo, I.V.; Colella, F.; Ricciardi-Tenore, C.; Di Salvatore, M.; Tortora, G.; De Maria, R.; Giuliante, F.; Cassano, A.; Basso, M.; et al. Mutational Status of Plasma Exosomal KRAS Predicts Outcome in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, S.A.; Luecke, L.B.; Kahlert, C.; Fernandez, A.F.; Gammon, S.T.; Kaye, J.; LeBleu, V.S.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Weitz, J.; Rahbari, N.; et al. Glypican-1 Identifies Cancer Exosomes and Detects Early Pancreatic Cancer. Nature 2015 523:7559 2015, 523, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goričar, K.; Dolžan, V.; Lenassi, M. Extracellular Vesicles: A Novel Tool Facilitating Personalized Medicine and Pharmacogenomics in Oncology. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 671298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beetler, D.J.; Di Florio, D.N.; Bruno, K.A.; Ikezu, T.; March, K.L.; Cooper, L.T.; Wolfram, J.; Fairweather, D.L. Extracellular Vesicles as Personalized Medicine. Mol Aspects Med 2023, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiramonai, L.; Liang, X.J.; Zhu, M. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Strategies for Tumor Immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2025, Vol. 17, Page 257 2025, 17, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, L.; Wu, L.; Li, Y. Extracellular Vesicles in Tumor Immunity: Mechanisms and Novel Insights. Molecular Cancer 2025 24:1 2025, 24, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z. Emerging Role of Exosomes in Cancer Therapy: Progress and Challenges. Molecular Cancer 2025 24:1 2025, 24, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; Mun, J.-G.; Han, Y.; Ho Seo, J.; Spada, S.; Cortese, K.; Aloi, N.; Area della Ricerca di Palermo, C.; Anna Piro, I. Cancer Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: A Potential Target for Overcoming Tumor Immunotherapy Resistance and Immune Evasion Strategies. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1601266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, B.; Li, B.; Wu, H.; Jiang, M. Cold and Hot Tumors: From Molecular Mechanisms to Targeted Therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024 9:1 2024, 9, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Kaslan, M.; Lee, S.H.; Yao, J.; Gao, Z. Progress in Exosome Isolation Techniques. Theranostics 2017, 7, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2023): From Basic to Advanced Approaches. J Extracell Vesicles 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Naranjo, J.C.; Wu, H.J.; Ugaz, V.M. Microfluidics for Exosome Isolation and Analysis: Enabling Liquid Biopsy for Personalized Medicine. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riazifar, M.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Pone, E.J.; Yeri, A.; Lasser, C.; Segaliny, A.I.; McIntyre, L.L.; Shelke, G.V.; Hutchins, E.; Hamamoto, A.; et al. Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes as Nanotherapeutics for Autoimmune and Neurodegenerative Disorders. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 6670–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschmann, D.; Mussack, V.; Byrd, J.B. Separation, Characterization, and Standardization of Extracellular Vesicles for Drug Delivery Applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 174, 348–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateescu, B.; Kowal, E.J.K.; van Balkom, B.W.M.; Bartel, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Buzás, E.I.; Buck, A.H.; de Candia, P.; Chow, F.W.N.; Das, S.; et al. Obstacles and Opportunities in the Functional Analysis of Extracellular Vesicle RNA - An ISEV Position Paper. J Extracell Vesicles 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Zickler, A.M.; El Andaloussi, S. Dosing Extracellular Vesicles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 178, 113961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.P.K.; Stevens, M.M. Strategic Design of Extracellular Vesicle Drug Delivery Systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2018, 130, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Nordin, J.Z.; McLachlan, A.J.; Chrzanowski, W. Extracellular Vesicles as the Next-Generation Modulators of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Medications and Their Potential as Adjuvant Therapeutics. Clin Transl Med 2024, 14, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takakura, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Takahashi, Y. Therapeutic Application of Small Extracellular Vesicles (SEVs): Pharmaceutical and Pharmacokinetic Challenges. Biol Pharm Bull 2020, 43, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, S.; Konstantinov, K.; Young, J.D. Manufactured Extracellular Vesicles as Human Therapeutics: Challenges, Advances, and Opportunities. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2022, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villata, S.; Canta, M.; Cauda, V. Evs and Bioengineering: From Cellular Products to Engineered Nanomachines. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claridge, B.; Lozano, J.; Poh, Q.H.; Greening, D.W. Development of Extracellular Vesicle Therapeutics: Challenges, Considerations, and Opportunities. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida Fuzeta, M.; Gonçalves, P.P.; Fernandes-Platzgummer, A.; Cabral, J.M.S.; Bernardes, N.; da Silva, C.L. From Promise to Reality: Bioengineering Strategies to Enhance the Therapeutic Potential of Extracellular Vesicles. Bioengineering 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.C.; Maragh, S.; Ghiran, I.C.; Jones, J.C.; Derose, P.C.; Elsheikh, E.; Vreeland, W.N.; Wang, L. Measurement and Standardization Challenges for Extracellular Vesicle Therapeutic Delivery Vectors. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 2149–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).