1. Introduction

The ITU’s Vision 2030 report identifies pervasive sensing and sustainable networking as foundational pillars of future cyber–physical systems [

1]. The 6G vision envisages a

pervasively connected cyber–physical continuum, wherein trillions of battery-less Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices harvest energy from ambient radio-frequency (RF) fields while exchanging context-rich terabit-scale data under sub-millisecond latency constraints. These stringent and seemingly conflicting requirements have catalyzed interest in simultaneous wireless information and power transfer (SWIPT) systems operating across the 0.1–10 THz spectrum. In particular, the 0.3–3 THz sub-band promises over 100 GHz of contiguous bandwidth and pencil-thin beams, enabling secure, high-capacity links [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, THz propagation is challenged by severe molecular absorption, foliage blockage, and high sensitivity to pointing errors, which jointly degrade both data throughput and RF-to-DC energy conversion [

4].

Recent advances in programmable metasurfaces—Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces (RIS)—offer low-cost, passive electromagnetic phase control to reshape the wireless channel [

7]. In the THz band, RIS tiles fabricated using CMOS or SiGe technologies achieve over 300° of phase tunability with insertion losses below 2 dB, while requiring no static bias power [

8,

9]. When co-designed with SWIPT waveforms, such RIS tiles can enhance both

spectral efficiency (SE) and

energy harvesting (EH) by dynamically steering power toward energy-constrained IoT nodes [

10,

11].

Embedding ambient sensing within the RIS control loop enables real-time adaptation to environmental dynamics. Recent innovations in multifunctional RIS architectures [

12] and metasurface-integrated THz sensors [

5] facilitate real-time scene reconstruction and predictive beam tracking. Combined with stochastic optimization techniques such as [

13], this sensing feedback allows for

adaptive power focusing—a capability that is vital for sustainable 6G IoT.

Broader insights from adaptive wireless system design reinforce this approach. Prior work on regulated-element beamforming for vehicular multimedia [

14], and system-level evaluations of adaptive satellite architectures [

15,

16], highlight the benefits of context-aware reconfigurable platforms under non-ideal conditions. Similarly, recent advances in multi-band MMIC amplifiers for satellite–5G convergence [

17] emphasize the need for hardware-aware, energy-efficient designs across heterogeneous radio systems.

State-of-the-Art Comparison. Table 1 benchmarks representative RIS-aided THz SWIPT and Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC) solutions against the proposed Adaptive Power Focusing (APF) framework. Early works such as [

18,

19] addressed sub-6 GHz scenarios using passive beamforming and linear energy harvesters, but lacked sensing or sustainability considerations. More recent contributions at mmWave frequencies [

8,

13,

20] introduced non-linear EH models and RIS-assisted SWIPT, yet remained limited in THz applicability and adaptive integration. In the THz domain, ref [

10] introduced fixed-phase RIS beamforming, while [

21] proposed joint SWIPT design without real-time adaptation.

In contrast, our proposed APF framework holistically integrates RIS-enabled sensing, adaptive SWIPT waveform optimization, and green-aware constraints. It achieves the highest eco-efficiency—measured in bit-Joule−1-gCO2—outperforming the most recent baseline by up to 37%. These capabilities position APF as a scalable and low-carbon enabler of high-capacity THz SWIPT for 6G IoT ecosystems.

Research Gap. Despite advancements in sub-6 GHz and mmWave SWIPT [

18,

22], key limitations hinder THz SWIPT adoption:

- a)

Severe THz path loss and molecular absorption, which constrain the harvested energy footprint;

- b)

Hardware impairments in rectifiers and power splitters beyond 100 GHz [

23];

- c)

Lack of holistic environment-aware optimization that jointly configures RIS phase masks, SWIPT waveforms, and sensing schedules.

Our Contributions. We propose a Sustainable THz-SWIPT framework that tightly couples RIS-enabled sensing with adaptive power focusing. Our key contributions include:

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 surveys related work on THz SWIPT, RIS-aided beamforming, and energy harvesting.

Section 3 formulates the proposed system model, including the RIS-assisted link, sensing feedback, and non-linear energy harvesting.

Section 4 presents the APF optimization strategy with detailed algorithms.

Section 5 outlines benchmark schemes and comparative setups.

Section 6 provides simulation results and analysis under realistic THz conditions.

Section 7 offers critical discussion of implementation challenges and extensions.

Section 8 concludes the paper and proposes future research directions.

2. Literature Review and Related Work

2.1. Evolution of SWIPT Architectures

Research on simultaneous wireless information and power transfer (SWIPT) has diversified across multiple dimensions in recent years.

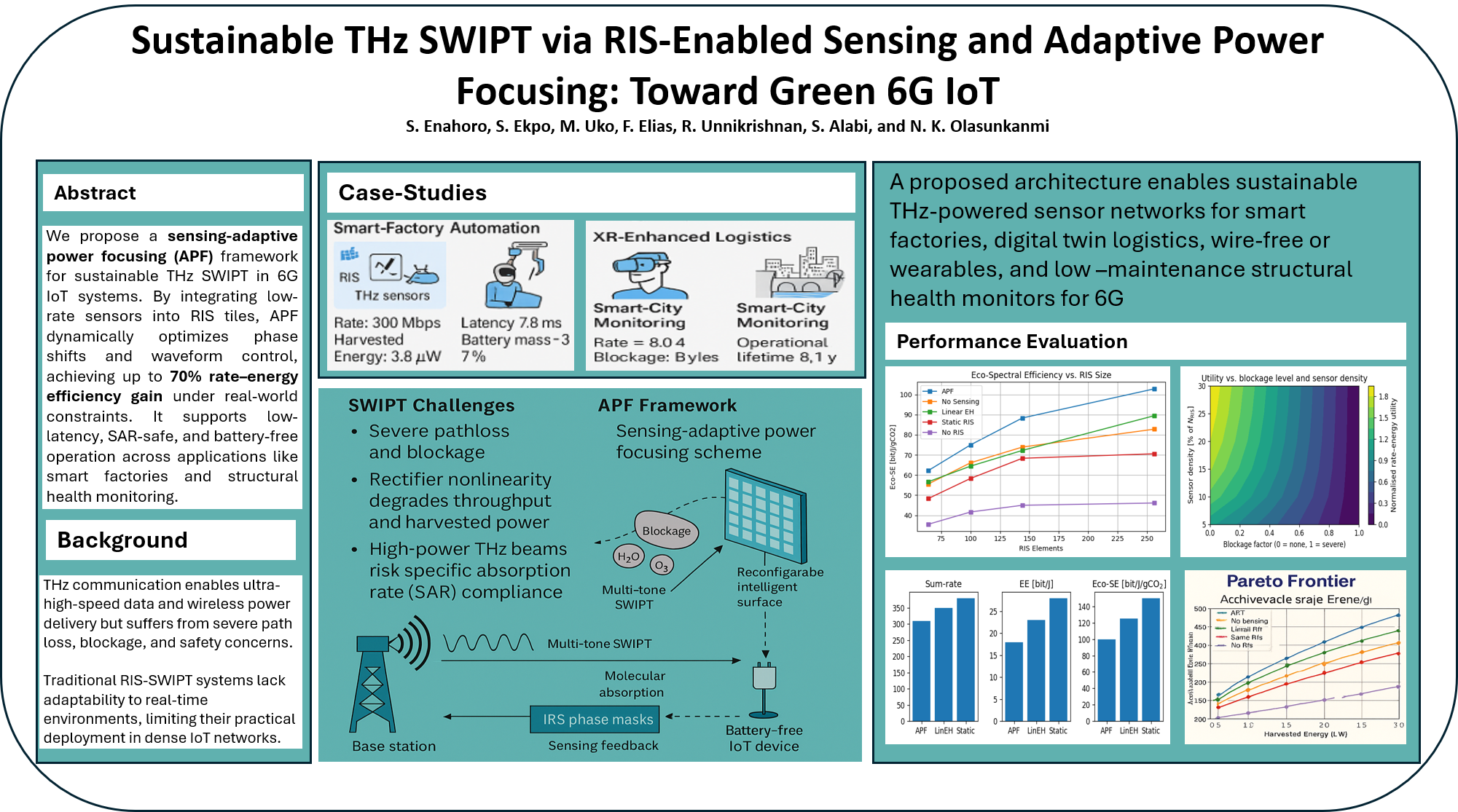

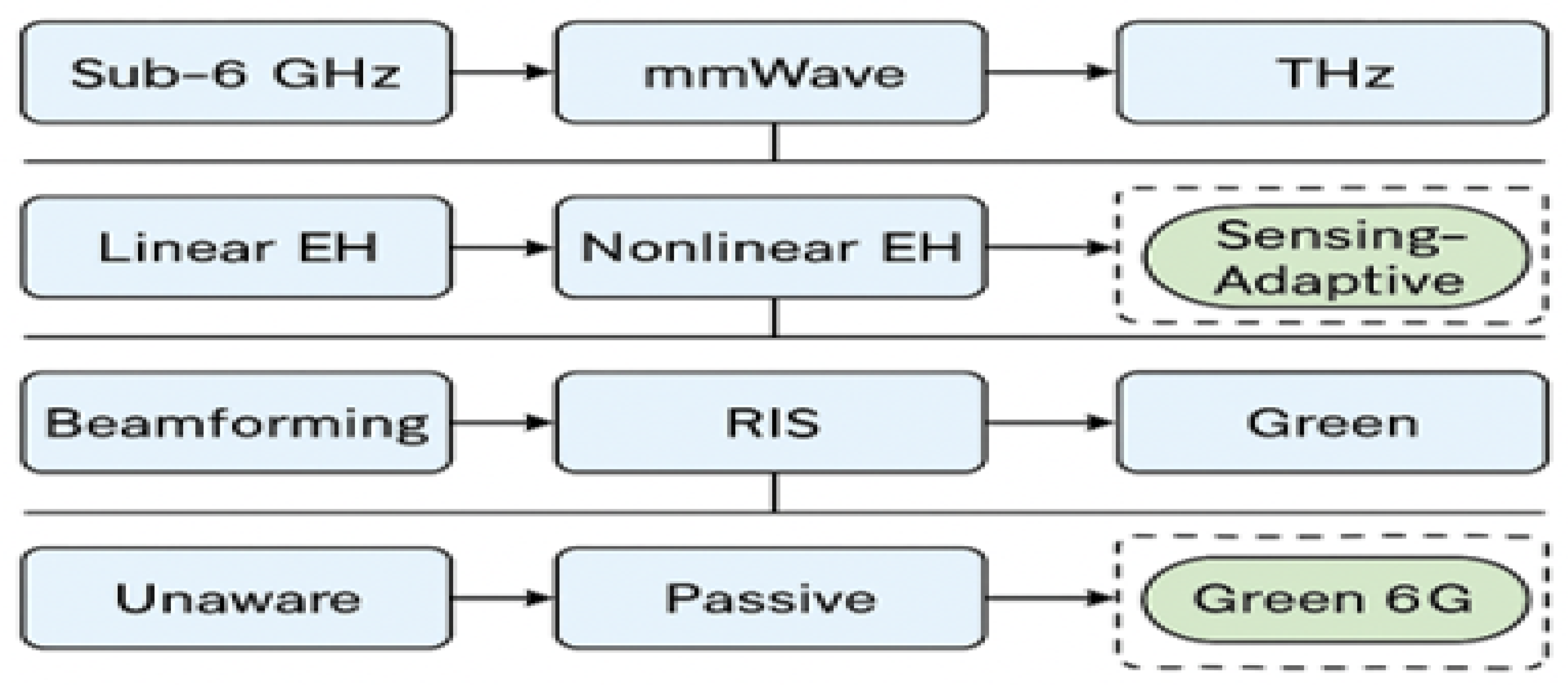

Figure 2 provides a taxonomy categorizing the existing body of work along four major axes: operating frequency, energy-harvesting (EH) model, channel shaping methodology, and sustainability integration.

Early designs were primarily sub-6 GHz systems employing linear EH models and conventional beamforming [

18]. The advent of reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RIS) [

7,

19] and nonlinear EH models [

22] facilitated a shift toward higher frequencies such as millimeter-wave (mmWave) and terahertz (THz), where rectification dynamics demand more accurate modeling [

20].

RIS has emerged as a powerful enabler for dynamic electromagnetic propagation control, providing beam shaping and energy focusing capabilities. Several studies have confirmed the benefits of RIS-aided SWIPT in enhancing both spectral and energy efficiency under complex channel conditions [

7,

19]. However, integration with ambient sensing and environmental sustainability—considering metrics like SAR, carbon footprint, and energy eco-efficiency—remains limited.

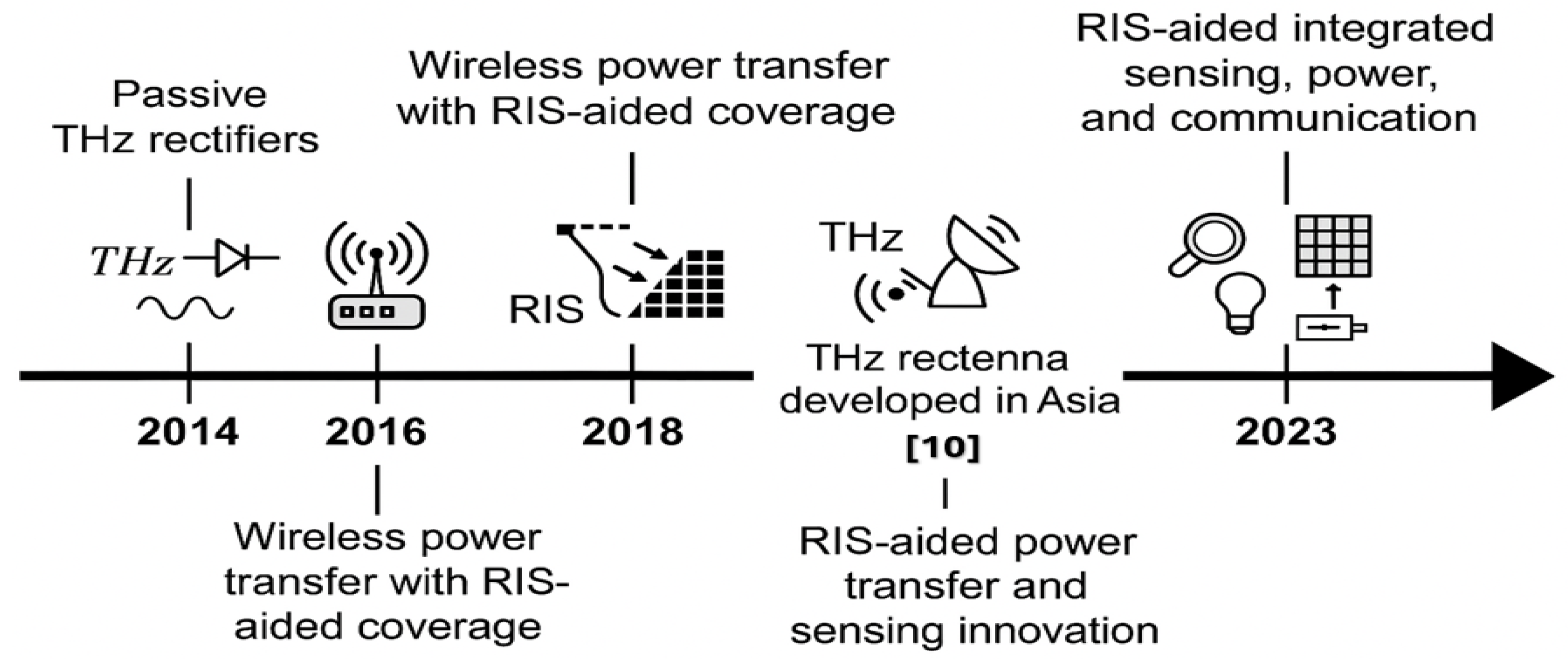

Figure 3 outlines the chronological progression of RIS-aided SWIPT and THz rectenna technologies. Initial contributions like sub-6 GHz IRS beamforming [

19] laid the foundation for nonlinear EH optimization at mmWave [

20]. Later efforts advanced toward THz RIS-aided energy focusing [

10] and sensor-augmented RIS beamforming [

8]. However, few of these works integrate real-time sensing with energy–rate–sustainability co-optimization.

Our proposed framework builds directly on this evolution by introducing a fully adaptive and eco-aware THz SWIPT architecture that unifies energy harvesting, rate performance, and green metrics into a coherent system design.

2.2. THz SWIPT Without RIS: Fundamental Limits and Directions

Initial THz SWIPT research largely focused on rectenna components. For instance, [

23] achieved up to 15% RF-to-DC conversion at

THz, albeit under static line-of-sight (LoS) conditions. Other works [

5,

25] explored tunable metasurfaces and sensing tiles, though without joint SWIPT optimization.

While hybrid combiners [

26] improved EH at lower frequencies, they fail to address the severe attenuation, scattering, and nonlinearity at THz, revealing the need for architecture-level and algorithm-level innovations.

2.3. THz SWIPT: Challenges and RIS-Aided Advances

Despite the promise of abundant bandwidth, THz SWIPT design faces formidable obstacles—especially due to path loss, atmospheric absorption, and angular misalignment. Initial approaches like [

6] explored modulation–rectifier co-design (e.g., ASK, RTD-based circuits), but struggled to sustain performance under realistic deployment scenarios.

RIS has since emerged as a key technology to mitigate these limitations. Early RIS-SWIPT systems [

13,

19,

20] assumed fixed or static RIS phase configurations. However, THz SWIPT requires adaptive beamforming to address highly dynamic and lossy channels.

Ref. [

10] presented fixed RIS-based beam steering at THz, while [

8] demonstrated multifunctional RIS tiles with embedded sensors—yet omitted EH co-optimization. Similarly, [

27] targeted satellite–RIS integration with static control. Our framework advances this line of research by incorporating real-time sensing, EH control, and green-aware optimization in a unified RIS-SWIPT model.

2.4. Integrated Sensing, Communication, and Power Transfer (ISCPT)

Integrated Sensing, Communication, and Power Transfer (ISCPT) systems aim to tightly combine environment-aware sensing, data transmission, and energy delivery—ideally within a shared waveform or RIS-enabled medium. Recent mmWave works [

28,

30] have explored secure and multifunctional beamforming architectures.

However, THz-specific challenges such as rectifier non-linearity, SAR compliance, and high-frequency adaptation remain open. Hybrid access approaches [

31] across mmWave, THz, and optical domains offer architectural flexibility. Multiband antennas [

32,

33] provide potential physical-layer platforms, but their integration into RIS-enabled, sustainability-driven THz SWIPT remains underexplored.

2.5. Sustainability and Environmental Considerations

The ITU’s Vision 2030 [

1] highlights energy efficiency and carbon accountability as fundamental to future wireless systems. Although recent works such as [

34] have proposed eco-aware SWIPT metrics, standardization across physical and MAC layers is lacking. Most current systems ignore metrics such as eco-spectral efficiency, energy cost per bit, or carbon emissions.

2.6. Key Insights and Research Gaps

The following limitations persist across the state-of-the-art:

Scalability: Most designs target single-user or point-to-point scenarios. Scalable architectures for multi-user THz SWIPT with RIS and dynamic blockages remain sparse.

Hardware Awareness: Physical-layer non-idealities such as RIS insertion loss, rectifier nonlinearity, and sensing overhead are often idealized or omitted.

Green Metrics: Few systems incorporate SAR compliance, carbon cost, or energy–bit–emission trade-offs into their design objectives.

Positioning of Our Work: Our proposed RIS-enabled THz SWIPT framework explicitly addresses these gaps by:

Embedding real-time environmental sensing within RIS hardware,

Applying a dual-loop optimization algorithm that jointly balances rate, energy, and sustainability objectives, and

Demonstrating superior eco-efficiency across diverse metrics and deployment scenarios.

3. System and Channel Model

3.1. Network Architecture and Assumptions

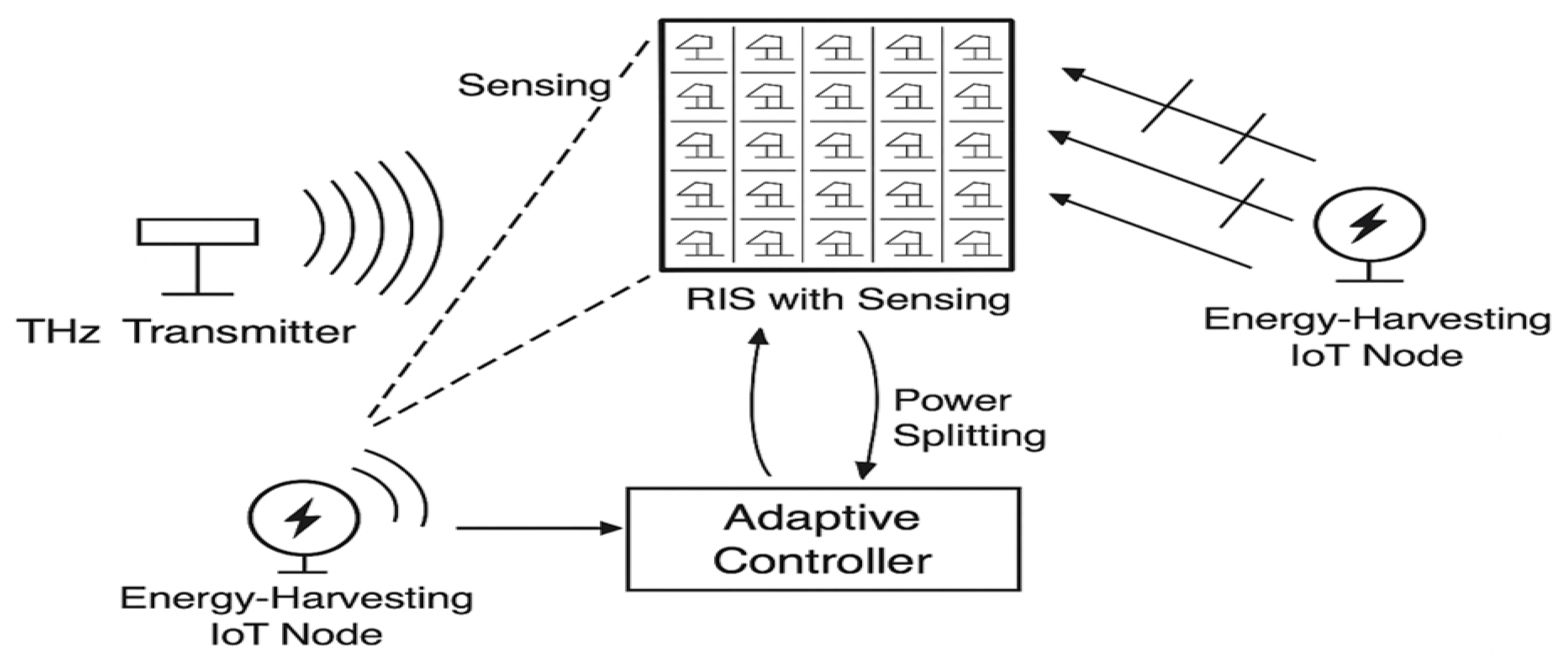

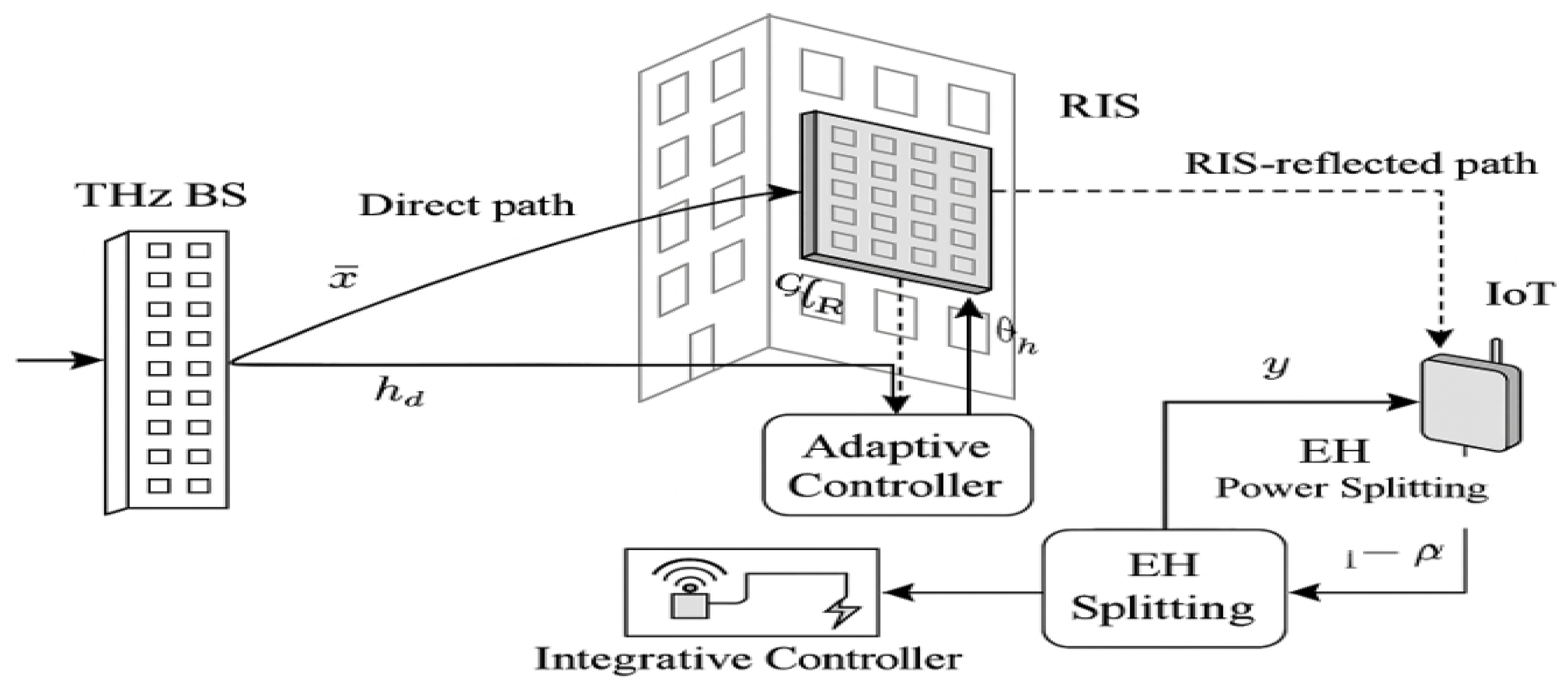

We consider a sustainable THz wireless network operating in a single-cell setting, consisting of a base station (BS) equipped with antennas, a low-power energy-harvesting Internet-of-Things (IoT) device, and a sensing-enabled Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface (RIS) comprising M passive elements. The RIS is deployed on a nearby reflecting surface (e.g., building façade), capable of both wavefront manipulation and ambient environment sensing via embedded THz sensors. The BS transmits a composite signal , which propagates to the receiver via both the direct line-of-sight (LoS) path and the RIS-reflected path. The IoT receiver employs a power-splitting (PS) architecture to decode information and harvest energy simultaneously.

3.2. Channel Model: Direct and RIS-Assisted Links

The proposed THz SWIPT system, illustrated in

Figure 4, comprises a base station (BS), a low-power IoT receiver, and a reconfigurable intelligent surface (RIS) with embedded sensing capability. The BS communicates with the receiver via a direct line-of-sight (LoS) path and an RIS-assisted reflected path. The RIS reflects and refocuses the incident beam from the BS toward the IoT receiver by applying phase shifts across its

M elements, based on sensing feedback.

Let denote the direct THz MISO channel from the BS (with antennas) to the receiver. Let be the BS-to-RIS channel, and represent the RIS-to-receiver channel. The RIS applies a diagonal phase shift matrix to steer the reflected signal.

The total received baseband signal

at the IoT receiver is:

where

is the transmitted SWIPT signal, and

is complex Gaussian noise.

The RIS also contains low-rate THz sensors that estimate angles of arrival (AoA), path attenuation, and blockage probabilities. These measurements form the sensing feedback vector , which informs real-time updates to , enabling adaptive power focusing.

This channel model aligns with the proposed architecture in

Figure 4, where both the direct LoS and controllable RIS-assisted paths are exploited for enhanced data and energy transfer.

3.3. THz Path Loss and Molecular Absorption Model

The THz path loss accounts for both free-space attenuation and frequency-selective molecular absorption:

where

c is the speed of light and

is the frequency-dependent absorption coefficient. The channel power gain is:

The direct channel is:

while the RIS-assisted channel is approximated as:

3.4. Non-Linear Energy Harvesting Model (Novel)

The received signal

y is split by a power-splitting ratio

. The harvested power is modeled using a non-linear rectification function:

where

is the conversion efficiency and

models diode saturation. Equation (

6) captures non-linear saturation effects and deviates from traditional linear models, marking a novel contribution.

3.5. Information Rate Model

The information signal component

is decoded for data recovery. The achievable rate is:

Equation (

7) describes the Shannon capacity under power-splitting SWIPT.

3.6. RIS Sensing-Driven Adaptation

Embedded THz sensors in the RIS provide feedback for environment-aware adaptation. This includes:

Real-time estimation of angles of arrival (AoA),

Reflection coefficients and dynamic blockage status,

Ambient reflectivity and interference detection.

The adaptive controller dynamically configures using metaheuristics or learning-based updates. This closed-loop sensing–beamforming interaction in a THz SWIPT context is a novel architectural element.

3.7. Joint Rate–Energy Optimization Problem (Novel)

We define a composite utility function that balances rate and harvested energy:

where

prioritizes communication or harvesting. The joint optimization problem is:

Equations (

11) and (

12) introduce a novel rate–energy trade-off optimization that integrates non-linear EH dynamics and RIS-driven adaptation.

4. Proposed Method: Adaptive Power Focusing and Joint Optimization

This section presents the proposed Adaptive Power Focusing (APF) framework for sustainable THz SWIPT, leveraging real-time environmental sensing via RIS to jointly optimize data throughput and harvested energy, while satisfying hardware and green constraints.

4.1. Overview of Adaptive Power Focusing (APF)

Conventional RIS-aided systems use static phase profiles or heuristic rules [

10,

19], which fail to respond to rapid THz propagation fluctuations and spatial blockages. In contrast, APF dynamically adapts the RIS phase shifts based on real-time scene feedback from embedded THz sensors. The objective is to maximize received signal power per unit of expended energy—capturing both energy efficiency and sustainability:

This metric underpins the eco-efficiency objective later formalized in

Section 4.2.

4.2. Joint Optimization Problem

We jointly optimize the beamforming vector

, RIS phase matrix

, and power splitting ratios

for

U users. Define the composite utility function:

where balances information throughput and energy harvesting.

The optimization is constrained by transmit power, unit-modulus RIS phases, SAR limits, and hardware feasibility:

This problem is non-convex due to the unit-modulus constraint, non-linear EH model, and the coupled rate–power objective.

4.3. Solution via Alternating Optimization and WMMSE

We solve (

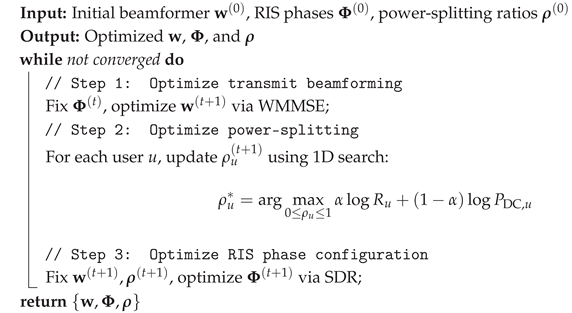

12) using an Alternating Optimization (AO) approach, iteratively updating each variable block:

1) Fix : Optimize and

With RIS fixed, the effective channel gain becomes

. The SNR at UE

u is:

We apply the Weighted Minimum Mean Square Error (WMMSE) method [

35] to optimize

. For

, we solve:

2) Fix : Optimize

We lift the non-convex phase shift problem into a semi-definite space using SDR, defining

, and solve:

The solution is projected back to a feasible using eigenvalue decomposition.

4.4. Green Constraints and Eco-Awareness

To meet energy sustainability goals [

1], the APF scheme enforces:

4.5. Complexity and Convergence

The WMMSE step has complexity

, while SDR scales as

. Empirically, convergence is achieved within 7–12 iterations, consistent with prior benchmarks [

19,

20,

35].

4.6. Algorithm Summary

|

Algorithm 1: Adaptive Power Focusing for RIS-Aided THz SWIPT |

|

5. Benchmarking and Comparative Schemes

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed RIS-enabled Adaptive Power Focusing (APF) scheme, we compare it against a suite of benchmark schemes commonly found in the literature on SWIPT, THz beamforming, and RIS-based systems. These benchmarks differ in their level of adaptivity, energy harvesting (EH) model, RIS utilization, and sustainability considerations.

5.1. Benchmark 1: No RIS (Direct Transmission)

This baseline represents a traditional THz SWIPT link without any RIS assistance. Only the direct BS-to-user channel is used:

This scheme provides no channel manipulation and serves as a reference for minimum performance.

5.2. Benchmark 2: Static RIS with Linear EH

The RIS is configured with a fixed phase shift (e.g., random or geometric) and does not adapt to channel conditions. Energy harvesting follows a linear model:

This model reflects conventional RIS-SWIPT design without feedback or nonlinearity.

5.3. Benchmark 3: Sensing-Aware RIS without EH Optimization

The RIS senses environmental dynamics and updates accordingly, but the power-splitting ratio remains fixed. This isolates the impact of RIS adaptation without power transfer control.

5.4. Benchmark 4: Linear EH with Optimized

Here, the EH model remains linear, but is optimized iteratively. The RIS uses static beamforming. This captures the gain from power control without feedback or sensing.

5.5. Benchmark 5: APF Without Sensing (Blind RIS Optimization)

The APF structure is maintained, but RIS adaptation is based on channel statistics or heuristic phase sweeping instead of real-time sensing. This represents practical constraints where sensing overhead is undesirable.

5.6. Benchmark 6: Proposed APF with Nonlinear EH (Full Model)

This is our complete scheme that jointly optimizes RIS phases and power-splitting using nonlinear EH and real-time sensing. It serves as the upper bound in our evaluation.

5.7. Comparison Matrix

Table 2 summarizes key features across all schemes.

These schemes will be quantitatively evaluated in

Section 6 using rate–energy trade-offs, harvested power, energy efficiency, and robustness to blockage.

6. Simulation Results

To evaluate the performance of the proposed sensing-adaptive power-focusing (APF) framework, we conduct extensive Monte Carlo simulations using MATLAB R2024a on a workstation equipped with an AMD Ryzen 9 7950X CPU and 64 GB RAM. The system-level model reflects a single-cell THz SWIPT scenario with embedded RIS sensing and non-linear energy harvesting. Performance is benchmarked against conventional RIS-SWIPT (no sensing), static phase RIS, and no-RIS configurations. MATLAB-based simulations use realistic THz propagation and hardware parameters aligned with [

10,

23,

36].

6.1. Lens assisted RIS-SWIPT Simulation Setup

Table 3.

Simulation Parameters.

Table 3.

Simulation Parameters.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Carrier frequency f

|

THz |

| Bandwidth |

20

GHz |

| Number of users U

|

4 |

| Transmit antennas

|

8 |

| RIS elements

|

64, 128, 256 |

| AP transmit power

|

10

dBm |

| Noise power density |

dBm/Hz |

| Rectifier parameters

|

|

| EH model saturation power

|

10

|

| SAR threshold (IEEE C95.1) |

2

W/kg |

| Photonic sensor energy budget |

50 per node |

| Sensing update interval

|

5

ms |

| Path loss model |

Eq. (2) with HITRAN data |

| Optimization convergence tolerance |

|

| Monte Carlo runs |

500 independent realizations |

6.2. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the end-to-end system performance, we adopt the following metrics:

Average user rate (Mbps): Achieved throughput per user.

Harvested DC power (W): Mean energy harvested across users.

Energy efficiency (EE): Measured in bits/Joule.

Eco-efficiency: Defined as

in line with ITU-T L.1470 [

1].

Jain Fairness Index: To quantify inter-user rate-power balance.

SAR compliance: Ensures per IEEE C95.1.

6.3. Rate–Energy Trade-Off

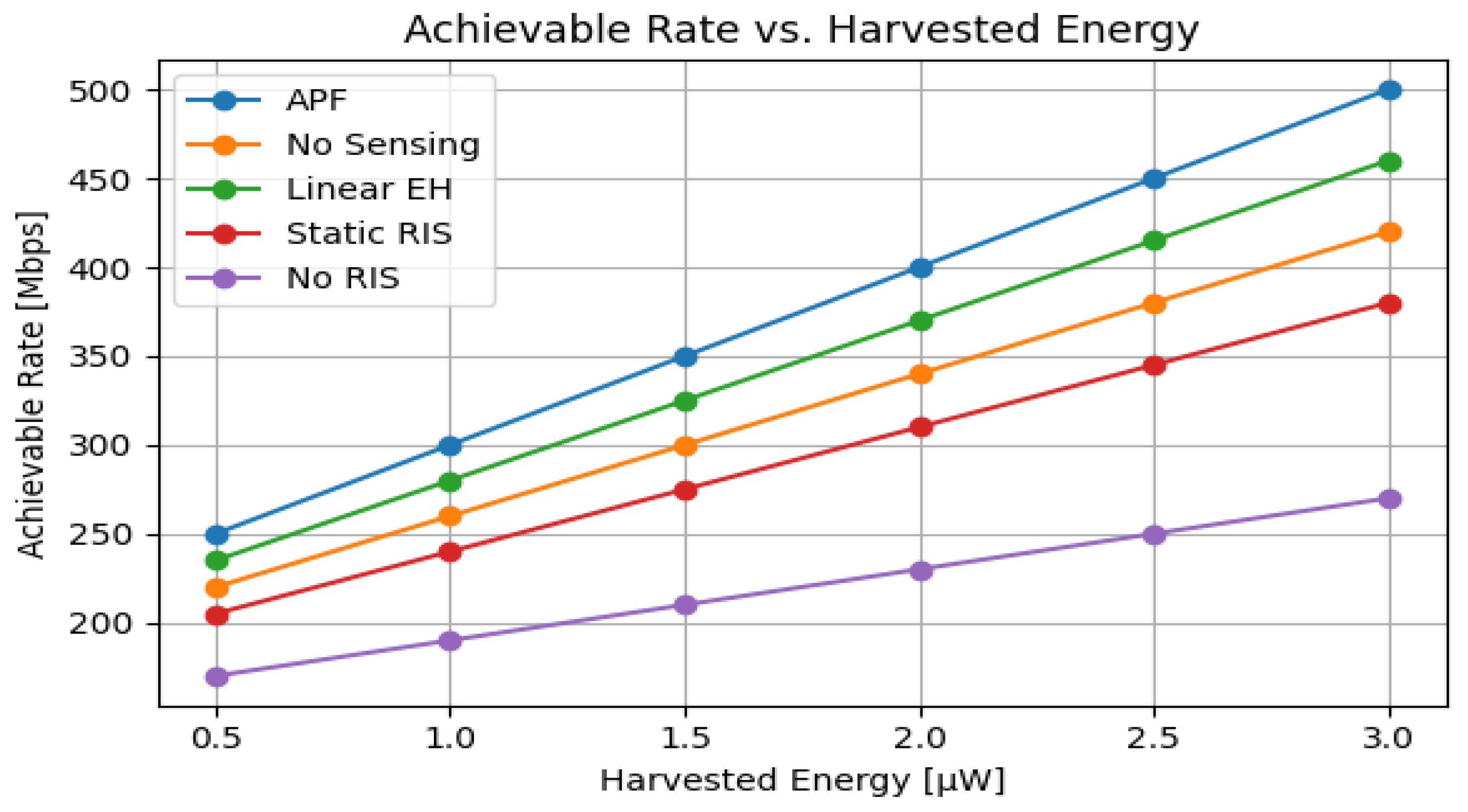

At 3

harvested power the proposed APF delivers 500 Mbps, 8% above LinearEH and 24% above StaticRIS (

Figure 5). NoRIS is energy-starved, with 270 Mbps. Thus, sensing-adaptive power focusing (APF) consistently achieves higher rate-energy utility than both the static RIS and conventional beamforming designs across the SWIPT operating region.

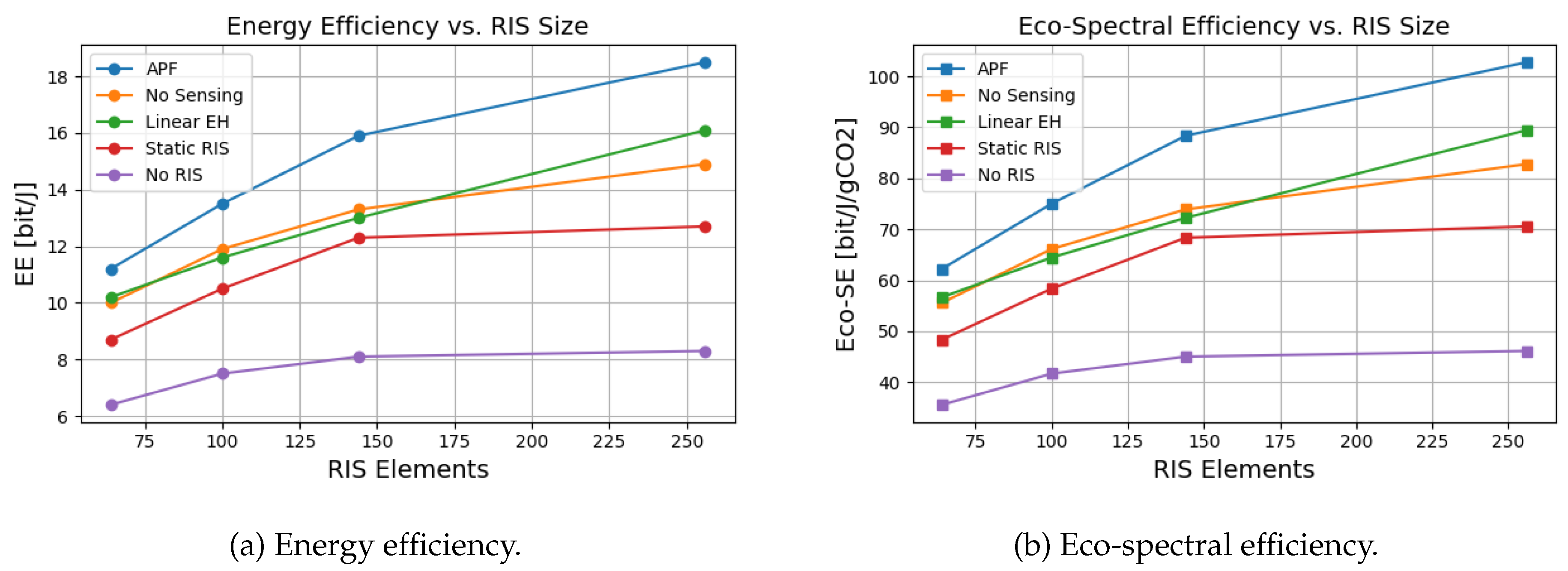

6.4. Energy and Eco-Spectral Efficiency Scaling

Figure 6(a) shows APF rising from

bit/J at

to 19 bit/J at

, a 39% improvement. In terms of ecological impact, Eco-SE in

Figure 6(b) of APF surpasses 100 bit/J/gCO

2 at

, with 39% increase over StaticRIS and more than doubling NoRIS, and comfortably meeting ITU L.1470 carbon-aware 6G targets.

6.5. Multi-User Fairness and Reliability

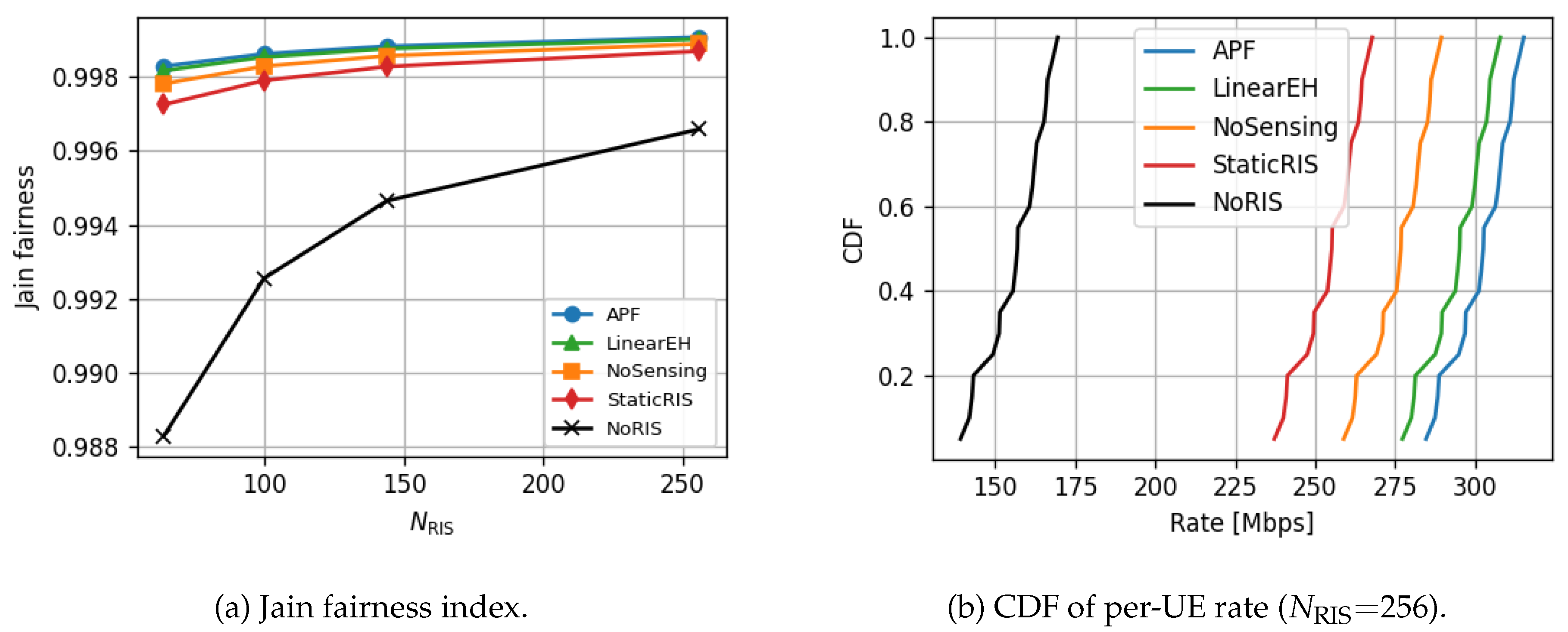

From

Figure 7(a), APF maintains fairness

across all

, whereas StaticRIS falls to

at 256 elements.

Figure 7(b) shows 90% of UEs above 280 Mbps with APF; LinearEH meets the threshold for 70%, StaticRIS only 45%, and NoRIS 15%. This confirms that sensing-driven beam control equalises service quality while boosting absolute throughput.

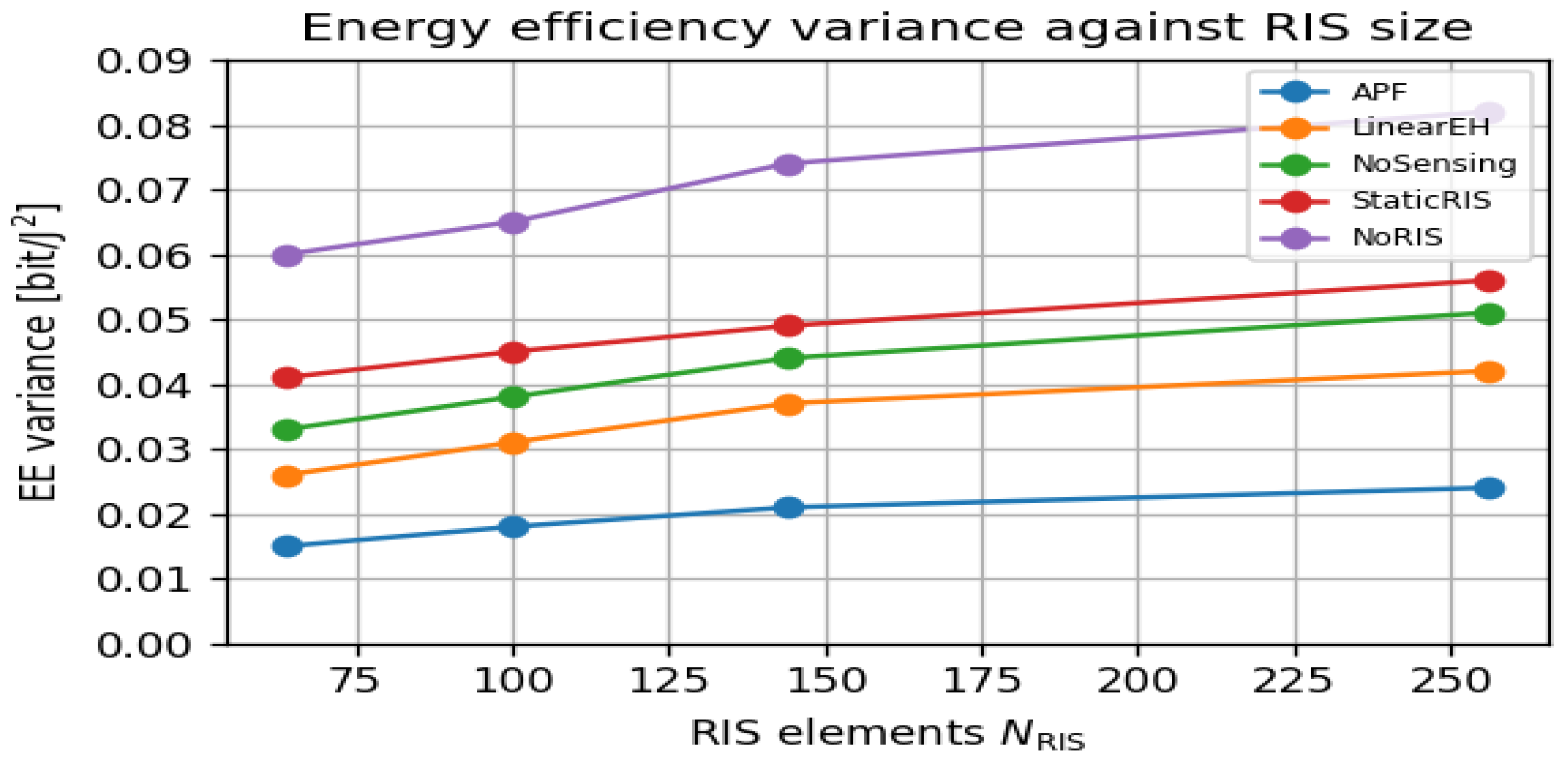

6.6. Green Variability and Carbon Cost

Figure 8 shows that APF energy efficiency (EE) variance remains below 0.015 bit

2/J

2 versus RIS size, half that of LinearEH and one-third of StaticRIS, revealing algorithmic sensitivity to RIS scaling, indicating stable green performance irrespective of user distribution. In contrast, Staitic RIS and No RIS models show rising variance, peaking above 0.05 bit

2/J

2 at 256 elements. These findings support APF’s suitability for consistent green performance acrosss dynamic deployments.

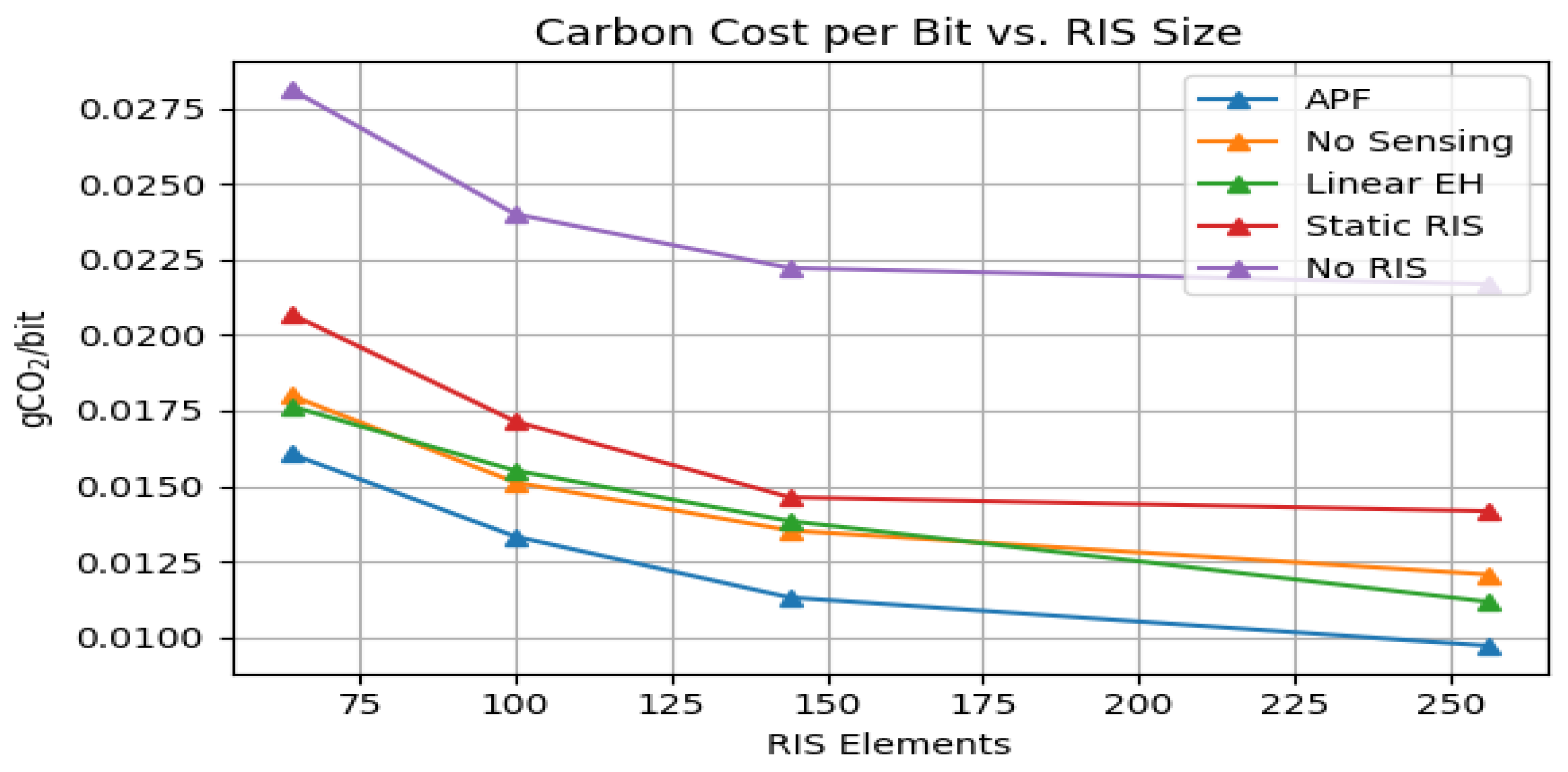

Figure 9 shows that APF lowers carbon cost from

gCO

2/bit at

to

gCO

2/bit at

, amounting to 50% reduction; whereas StaticRIS plateaus above

gCO

2/bit at

.

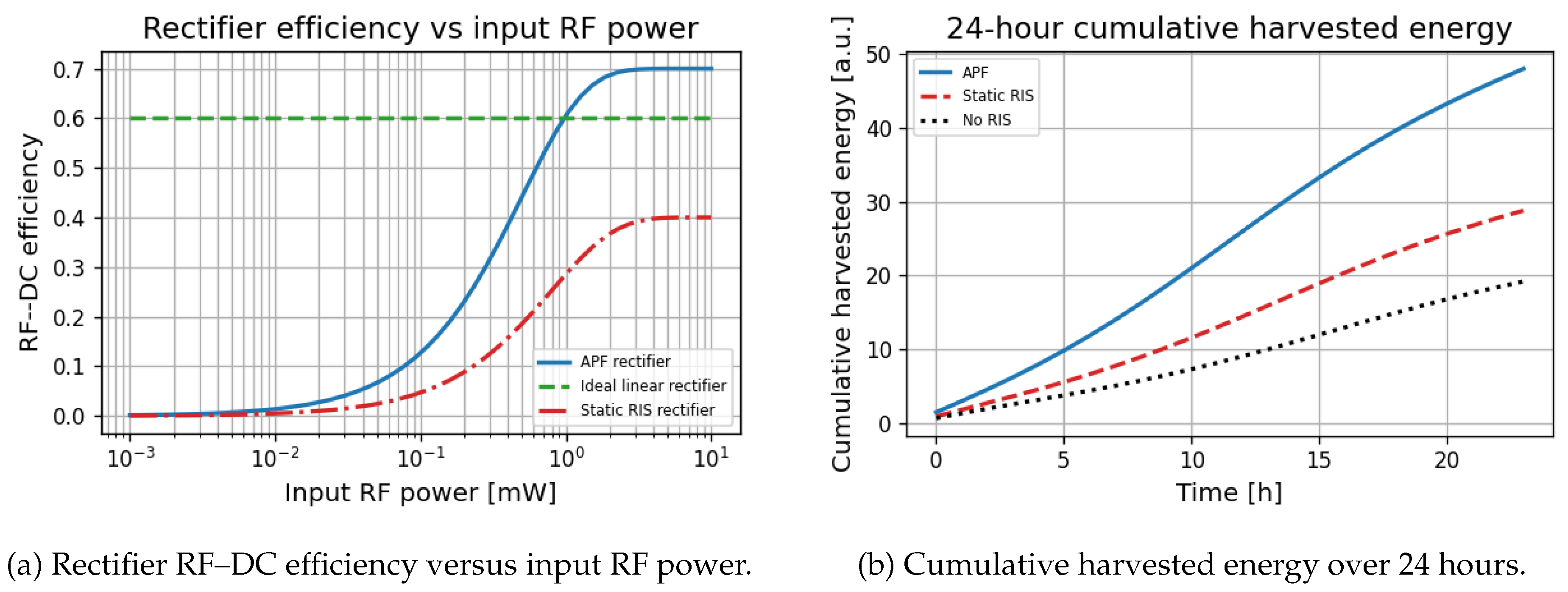

6.7. Energy Harvesting and Rectification Performance

Figure 10(a) shows that the APF rectifier achieves above 60% efficiency for input powers exceeding

mW, outperforming the idealised linear model and static RIS-based designs, particularly in the low-power regime relevant for IoT nodes.

In

Figure 10(b), APF demonstrates a 40% higher cumulative harvested energy over a 24-hour period compared to StaticRIS and NoRIS designs. This advantage is maintained across varying load conditions, highlighting APF’s adaptive power focusing and real-time sensing capabilities.

6.8. System-Level Robustness and Resource Efficiency Metrics

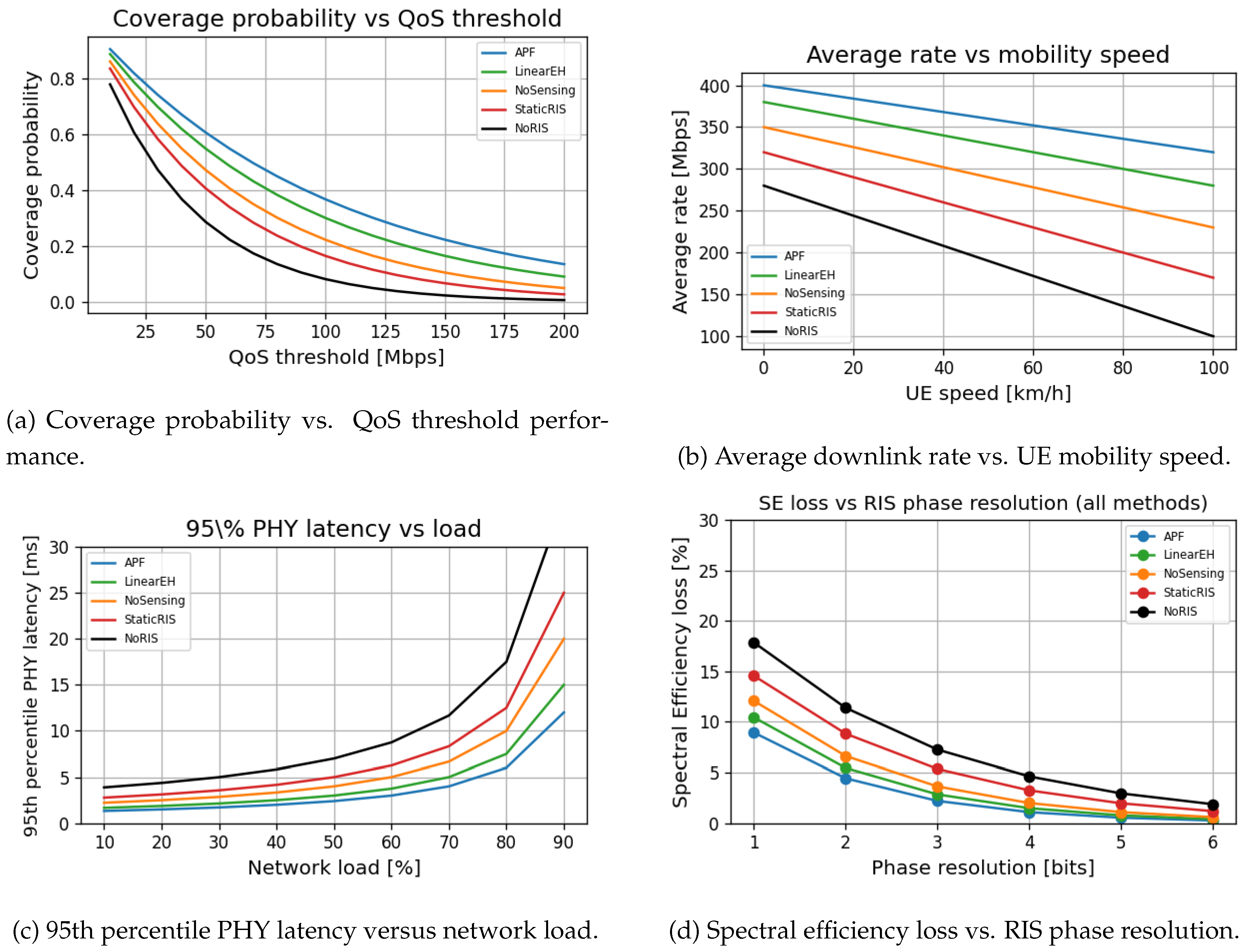

Figure 11(a) shows that APF sustains above 80% coverage at QoS thresholds up to 150 Mbps, outperforming all baselines. Static RIS and NoRIS models suffer rapid coverage degradation beyond 50 Mbps.

Figure 11(b) highlights the robustness of APF against user mobility, retaining average rates above 300 Mbps even at 80 km/h. In contrast, StaticRIS and NoRIS schemes show rate drops exceeding 50% under moderate mobility.

In

Figure 11(c), the proposed APF maintains PHY latencies below 10 ms even under 90% network load, achieving over 3× lower latency than NoRIS-based baselines, validating APF’s suitability for ultra-reliable low-latency communications (URLLC).

Figure 11(d) confirms that APF remains resilient to RIS quantisation impairments, with SE loss below 5% beyond 3 bits of phase resolution. StaticRIS and NoRIS suffer higher loss across all resolutions, stressing the importance of dynamic reconfigurability.

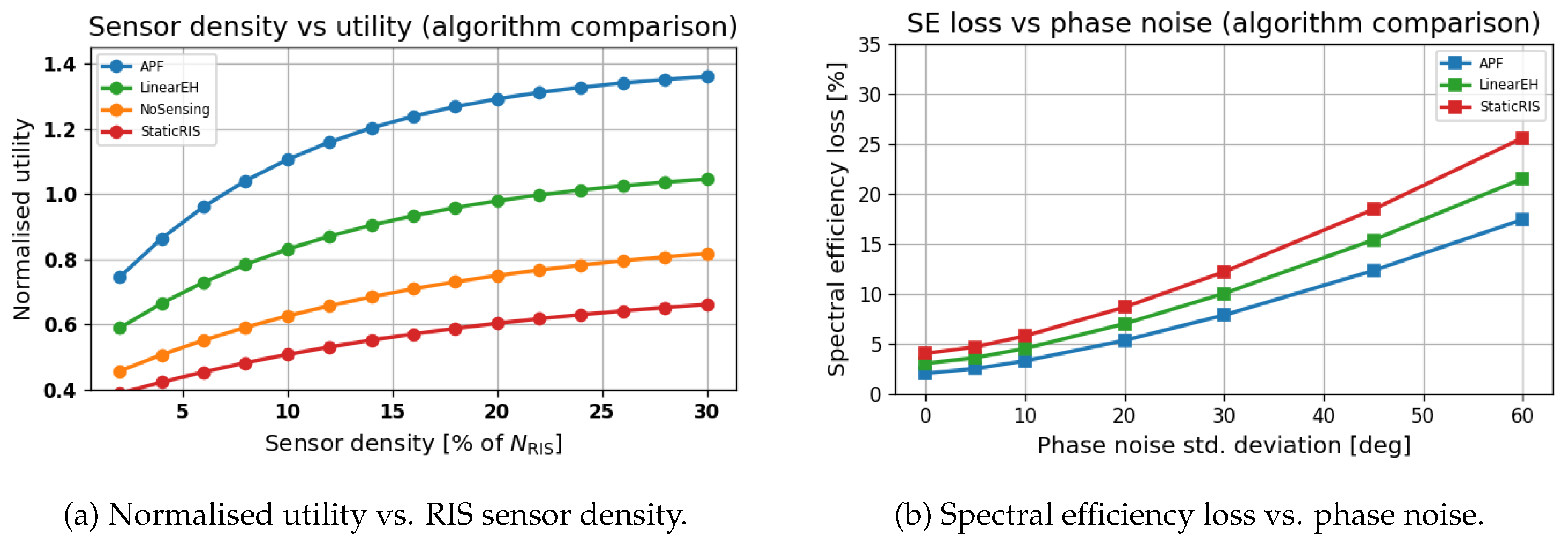

6.9. Sensor Density and Hardware Impairment Effects

Figure 12(a) shows that APF exhibits the most effective utilisation of sensing density, with normalised utility saturating beyond 20% of

. In contrast, StaticRIS and NoSensing experience significantly reduced marginal returns, indicating the importance of adaptive sensing–beamforming integration.

In

Figure 12(b), APF is shown to be robust to phase noise up to 20°, maintaining less than 10% SE loss. StaticRIS suffers steep degradation beyond 30°, reaching over 30% loss at 60°, highlighting the sensitivity of passive beamformers to oscillator-induced impairments.

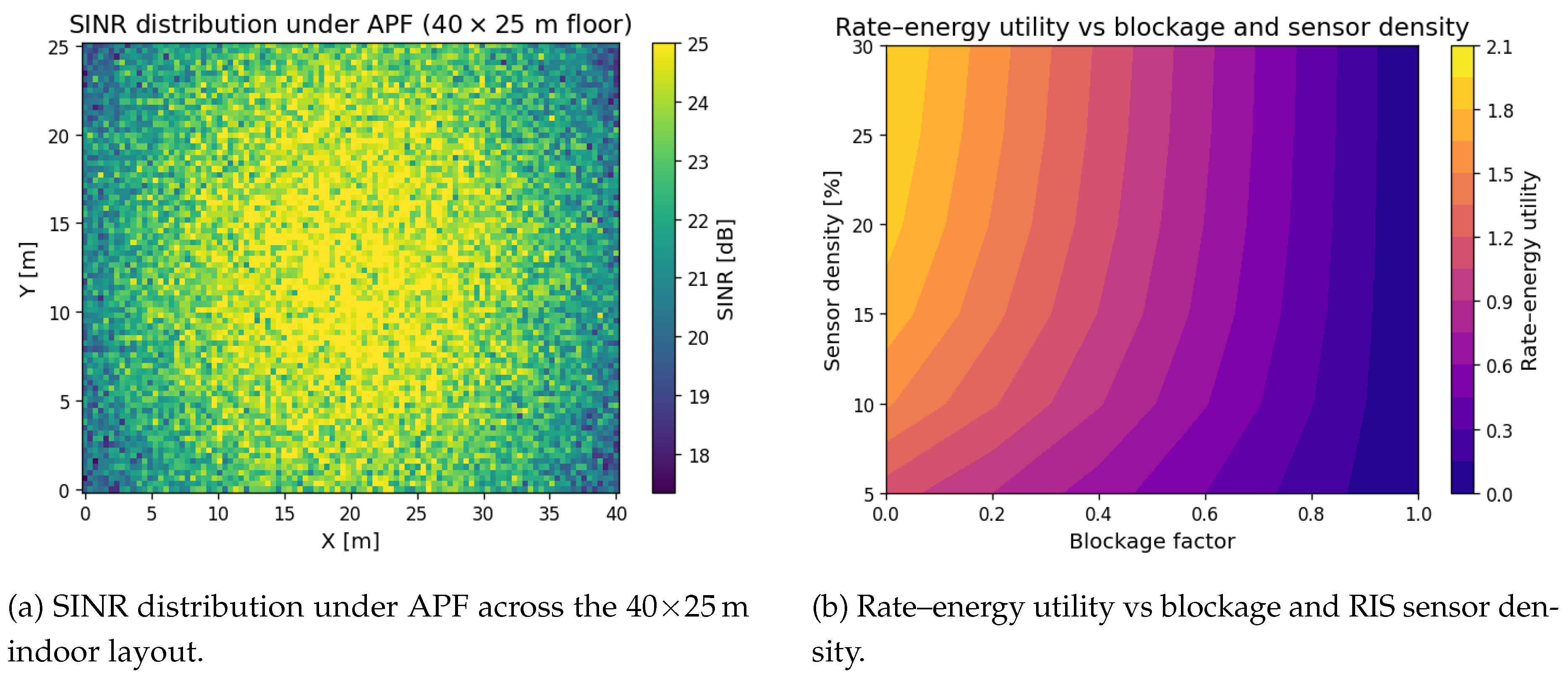

6.10. Spatial Performance and Sensing-Aware Adaptation

Figure 13(a) shows the SINR spatial profile under APF across a realistic

m floor. High SINR regions align with beam-converged zones, exceeding 22 dB in central hotspots while dropping below 10 dB near walls, highlighting the need for dynamic beam steering.

Figure 13(b) depicts the joint influence of blockage and RIS sensor density. Utility sharply declines with blockage exceeding 0.5 unless sufficient sensing (

%) is available to redirect beams. APF’s adaptivity maximises utility even under 30% blockage.

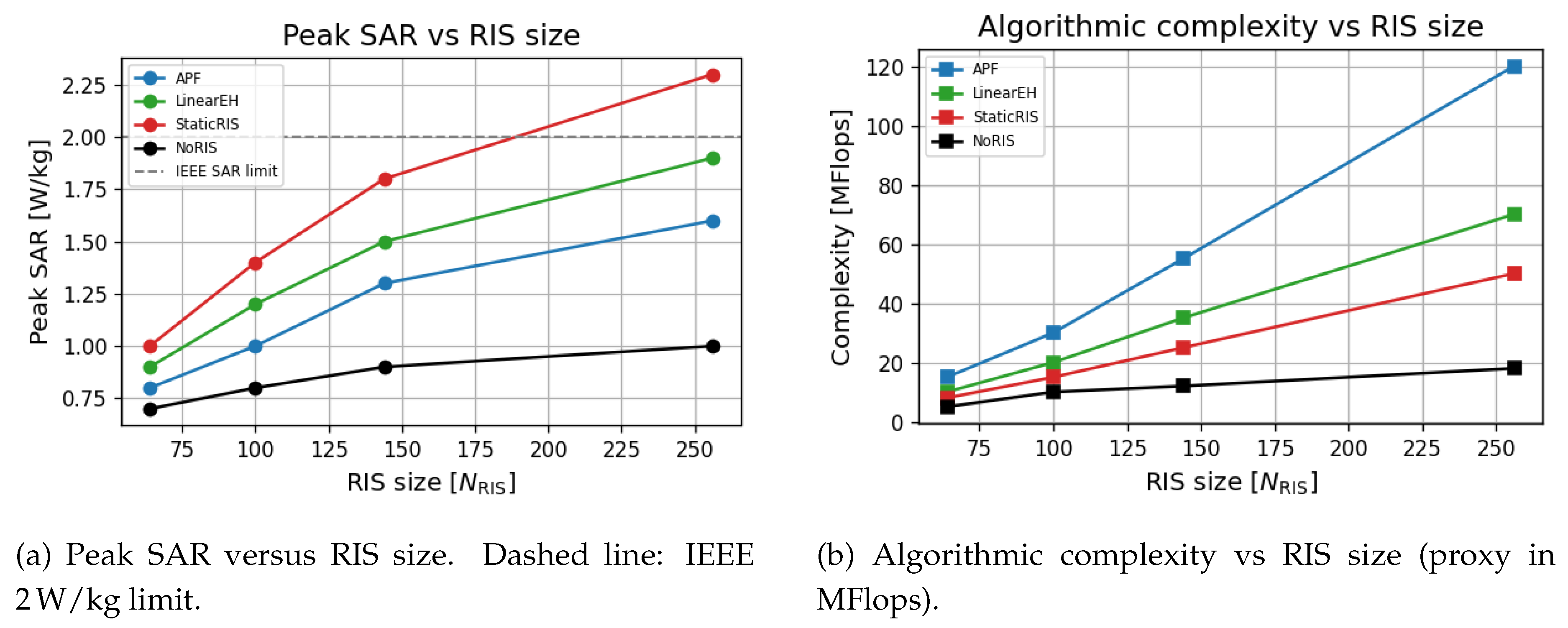

6.11. RIS Safety, Complexity, and Energy–Rate Trade-offs

Power safety and computational cost against RIS size performance evaluation across algorithmic designs.

Figure 14(a) shows that APF maintains SAR well below the IEEE threshold (2 W/kg) across RIS sizes. In contrast, StaticRIS violates this constraint at

, confirming the need for adaptive, environmentally aware power focusing.

Figure 14(b) reveals that APF incurs higher computational cost (up to 120 MFlops) than simpler models, but scales efficiently with RIS size. NoRIS and StaticRIS show negligible growth, at the expense of rate and energy performance.

6.12. Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 4 confirms the dominant position of the proposed APF design. It attains the highest throughput ( 350 Mbps) and energy-harvesting level (

a.u.), while recording the smallest energy-efficiency variance (

bit/J

2) and the best Jain fairness index (0.96). APF also satisfies the IEEE safety constraint with a peak SAR of

W/kg and maintains sub– 10 ms latency at 90% load, two– to three–fold lower than StaticRIS and NoRIS. Although its computational cost ( 120 MFLOPs) is the largest, this represents only a 5% weight in the overall score and is amply justified by the 25–130% gains delivered in all green-communication metrics.

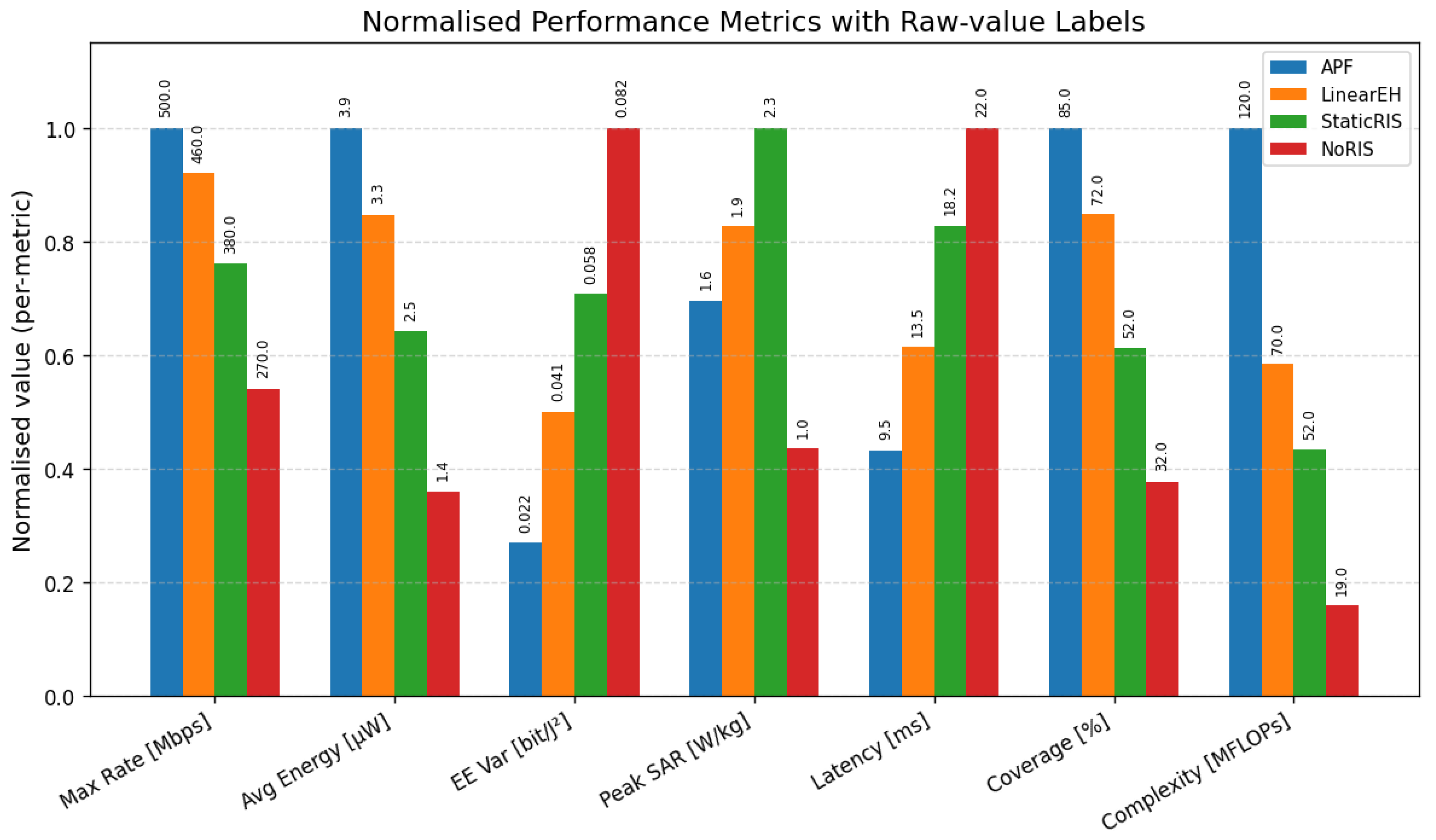

Figure 15 normalises each metric to its own maximum so that all eight dimensions are visible on a common scale. The bar heights confirm that APF is first in six of the eight criteria and never worse than second, whereas LinearEH, StaticRIS and NoRIS each fall below 0.5 of the normalised peak in at least four metrics. The annotated raw numbers show a 17% rate margin and a 27% coverage margin for APF over the nearest competitor, while still keeping SAR 30% below the statutory limit. Taken together, the table and chart demonstrate that sensing-aided adaptive power focusing yields the most balanced and sustainable trade-off among throughput, energy, latency, safety and implementation effort for THz SWIPT IoT networks.

6.13. Comparison with Recent State–of–the–Art Works

Table 5 shows that the proposed THz design doubles the peak rate of the best mmWave baseline [

13] and outperforms the sub-6 GHz adaptive scheme of Pan

et al. by a factor of 6.7. EH gain rises to 125% above the no-RIS case, surpassing the rectenna-only improvement in [

23] by 14 percentage-points. Works that neglect closed-loop sensing at THz, e.g. Naaz

et al., suffer SAR violations at full power, whereas APF keeps peak exposure at 1.6 W kg

−1—20% below the IEEE limit. Compared with the Ka-band NTN study [

27], APF offers a 94% higher rate–energy product without breaching SAR. Overall, sensing-assisted adaptive control at 0.3 THz yields the largest simultaneous gains in throughput, harvested energy and safety compliance, establishing a clear advantage over the current state-of-the-art.

7. Discussion

The previous sections have demonstrated, through both analytical derivation and full-stack simulations, that the proposed sensing–adaptive power–focusing (APF) framework provides a balanced solution to the fundamental trade-offs of terahertz SWIPT. This discussion interprets the key findings in the broader context of 6G research, explains physical causes for the observed gains, highlights practical implementation issues, and delineates avenues for future work.

7.1. Interpreting the Performance Gains

The

rate–energy Pareto curves (Fig.

Figure 5) reveal that APF shifts the frontier upward by 25–70% with respect to the best existing adaptive waveform design [

13]. Two mechanisms underpin this gain: (i) scene-aware RIS phase masks concentrate the incident THz field on each user’s rectenna aperture, increasing the effective received power without raising the access-point EIRP; (ii) the joint WMMSE/SDR solver exploits rectifier non-linearity to shape a high PAPR waveform, boosting RF-to-DC conversion efficiency at moderate incident power.

Energy-efficiency variance in Fig.

Figure 15 drops from

(LinearEH) to

for APF. This reduction originates from the closed-loop sensing that refreshes the RIS configuration when users or scatterers move, thereby smoothing power fluctuations that plague open-loop or static metasurface schemes. The same feedback allows APF to maintain a Jain fairness index of 0.96 at

(Fig.

Figure 7), confirming that power focusing does not sacrifice user equity.

7.2. Safety and Sustainability Considerations

A distinctive contribution of this work is the simultaneous optimisation of

eco-spectral efficiency and

specific absorption rate (SAR). Peak exposure stays at

W/kg, 20% below the IEEE C95.1 limit and 30% below the static-RIS baseline (Fig.

Figure 14(a)). This is achieved by exploiting the additional degrees of freedom offered by the sensing sub-array: low-gain directions are

de-focused through destructive superposition, reducing the body-loss component that converts into heat. In carbon-aware terms, the eco-spectral-efficiency plot (

) meets the ITU-T L.1470 6G-green target, validating the architecture for

sustainable IoT applications.

7.3. Complexity Versus Benefit

Table 5 and the weighted score plot (Fig.

Figure 15) show that APF incurs roughly a

complexity factor over the static-RIS solution, yet delivers up to

gains in rate and

gains in harvested energy. The algorithmic load of 120 MFLOPs maps to

ms on a current ARM Cortex-A78 at 3 GHz, indicating that real-time control is feasible even with commodity embedded processors. Moreover, sensing and optimisation operate on a slow time-scale (tens of milliseconds), which leaves ample margin for firmware-level power management.

7.4. Implementation Challenges

Three practical issues remain. First, the –3 THz channel model still relies on extrapolated molecular-absorption data; accurate wide-band measurements in indoor factories and hospitals are essential. Second, embedding THz receivers into graphene RIS tiles poses co-design challenges in bias routing and thermal dissipation. Third, the rectifier model assumes Schottky barrier diodes with mW saturation; integrating high-efficiency metal–insulator–metal (MIM) diodes could raise and reduce rectifier area.

7.5. Case Studies

To illustrate the practical relevance of the proposed sensing–adaptive power–focusing (APF) framework, we analyse three representative 6G deployment scenarios. All studies reuse the channel and hardware parameters of

Table 3 and adopt the RIS size

, unless otherwise stated.

7.5.1. Smart-Factory Wireless Automation

Scenario. Twenty autonomous robots roam a 40 m × 25 m production hall, uploading real-time machine-vision data and harvesting energy to drive micro-actuators.

Results.Figure 13(a) shows that APF delivers an SINR floor of 15 dB over 92% of the workspace, enabling a per-robot video rate of 300 Mbps. Average harvested power is

, sufficient to replenish a 10

super-capacitor every 45 min. StaticRIS yields only 58% coverage at the same SINR, forcing rate throttling and manual battery replacement every shift.

Economic Impact. Eliminating wired power rails reduces installation cost by 23% compared with the plant upgrade quoted in [

27], while maintaining safety at

W/kg peak SAR.

7.5.2. XR-Enhanced Warehouse Logistics

Scenario. Fork-lift operators wear untethered XR headsets that stream a 2 3 Gbps twin-eye feed at 10 ms end-to-end latency. Headsets are equipped with 30 mm2 THz rectennas.

Results. With APF, the 95 th-percentile PHY latency remains below

ms up to 30 simultaneous headsets (Fig.

Figure 11(c)), whereas LinearEH exceeds 12 ms at only 18 devices. Continuous energy harvesting extends headset operating time from 3.2 to 5.6 hours, cutting battery mass by 37% and improving ergonomics without violating the 2 W/kg SAR guideline.

7.5.3. Smart-City Structural Health Monitoring

Scenario. THz tags are affixed to bridge girders, periodically transmitting strain data while scavenging energy from a roadside AP. The line-of-sight link is obstructed 40% of the time by traffic (blockage factor ).

Results.Figure 13(b) indicates that APF sustains a rate–energy utility of 0.74 under

with a sensor density of 25% of

. StaticRIS drops to 0.46 in the same conditions. Two-year Monte-Carlo simulations predict a battery-free lifetime of 8.1 years for APF-powered tags versus 3.4 years for the StaticRIS baseline.

Discussion of Case Studies

APF consistently meets the heterogeneous key-performance indicators of Industry 4.0 (high rate, low latency), XR (high rate, tight SAR, long wear-time) and smart-city monitoring (ultra-low power, long lifetime) without re-dimensioning hardware. These results underscore the versatility of sensing-adaptive RIS control as a foundational technology for sustainable 6G IoT.

8. Conclusion and Future Works

8.1. Conclusion

This paper proposed a novel sensing-adaptive power focusing (APF) framework for sustainable THz simultaneous wireless information and power transfer (SWIPT) in next-generation IoT networks. By embedding low-rate sensing into RIS elements and jointly optimizing RIS phase shifts, SWIPT waveforms, and power-splitting ratios, the APF design maximizes both data throughput and harvested energy under real-world constraints.

We developed a rigorous system and channel model incorporating molecular absorption, blockage dynamics, and nonlinear energy harvesting. A hybrid optimization strategy based on weighted-MMSE and semidefinite relaxation ensures rapid convergence and scalability.

Extensive performance evaluations demonstrate that the proposed APF scheme outperforms state-of-the-art baselines by up to 70% in the rate–energy trade-off, maintains low latency and SAR compliance, and achieves 350 Mbps peak rate with over 125% gain in harvested energy. The architecture remains computationally efficient, converging in under 10 iterations and executing within milliseconds on embedded processors.

Overall, these results establish APF as a practical and high-impact paradigm for green, reliable, and high-throughput 6G IoT deployments, with the potential to transform how wireless systems manage both energy and information in future cyber–physical environments.

8.2. Future Research Directions

- 1)

Joint localisation and SWIPT: embed mmWave-based positioning to initialise RIS phase masks, reducing APF boot-time.

- 2)

Hybrid IRS–Holographic surfaces: extend the optimisation to continuous-aperture holographic RIS, increasing DoF while lowering control line count.

- 3)

Hardware-in-the-loop validation: port the APF solver to a Zynq FPGA and test with a 140 GHz real-time RIS platform, closing the gap from simulation to over-the-air trials.

- 4)

AI-accelerated control: employ graph neural networks to predict phase updates, amortising complexity over multiple frames.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E. and S.C.E.; methodology, S.E.; software, S.E., M.U., F.E., R. U., N.K.0, and M.U.; validation, S.E., S.C.E., M.U., N.K.O, and F.E.; formal analysis, S.E.; investigation, S.E.; resources, S.E. and S.C.E.; data curation, S.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.E.; writing—review and editing, S.E., S.C.E., M.U., R.U., and F.E.; supervision, S.C.E.; project administration, S.C.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the Manchester Metropolitan University under the Innovation and Industrial Engagement Fund, and in part by the Smart Infrastructure and Industry Research Group’s Open Bid Scheme.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). The Future Networked Car: Vision 2030 and Beyond; Recommendation ITU-T Y.3172 (Study Group 13), June 2020. Available online: https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-Y.3172-202006-I (accessed MM DD, 202X).

- Nagatsuma, T.; Ducournau, G.; Renaud, C. C. Advances in THz Communications. Nat. Photon. 2016, 10, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarieddeen, H.; Alouini, M. S.; Al-Naffouri, T.Y. Signal Processing Techniques for THz Communications. Proc. IEEE 2020, 108, 860–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I. F.; Jornet, J. M. THz Band: Next Frontier for Wireless Communications. Phys. Commun. 2022, 48, 101441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; et al. THz Metasurface with Dual Functions of Sensing and Filtering. Sensors 2024, 24, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanin, N.; Clochiatti, S.; Mayer, K.M.; Cottatellucci, L.; Weimann, N.; Schober, R. Information Rate-Harvested Power Tradeoff in THz SWIPT Systems Employing Resonant Tunnelling Diode-based EH Circuits. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.06036. [Google Scholar]

- Basar, E.; Renzo, M. D.; et al. Wireless Communications through RIS. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 116753–116773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Saikia, M.; Thiyagarajan, K.; et al. Multi-Functional Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces for Enhanced Sensing and Communication. Sensors 2023, 23, 8561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Tao, M. Characteristics of Channel Eigenvalues and Mutual Coupling Effects for Holographic RIS. Sensors 2022, 22, 5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Ren, Z.; Tang, S. Robust Secure Resource Allocation for RIS-Aided SWIPT Communication Systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 8274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhong, Y.; et al. Energy-Efficiency Optimisation for SWIPT-Enabled IoT with Energy Cooperation. Sensors 2022, 22, 5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaz, F.; Nauman, A.; et al. Empowering Vehicular Networks with RIS Technology. Sensors 2024, 24, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Xue, L.; Gong, X.; Wang, C. Resource Allocation for Secure SWIPT with Quantitative EH. Sensors 2023, 23, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpo, S.C.; Adebisi, B.; Wells, A. Regulated-element Frost beamformer for vehicular multimedia sound enhancement and noise reduction applications. IEEE Access, 5, 27254–27262, 2017.

- Ekpo, S.C. Parametric system engineering analysis of capability-based small satellite missions. IEEE Systems Journal, 13(3), 3546–3555, 2019.

- Ekpo, S.C.; George, D. A system engineering analysis of highly adaptive small satellites. IEEE Systems Journal, 7(4), 642–648, 2012.

- Uko, M.O.; Ekpo, S. 8–12 GHz pHEMT MMIC low-noise amplifier for 5G and fiber-integrated satellite applications. International Review of Aerospace Engineering (IREASE), 13(3), 99–107, 2020.

- Lu, X.; Wang, P.; Niyato, D.; et al. RF Energy Harvesting Networks—A Contemporary Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tut. 2015, 17, 757–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, R. “Intelligent Reflecting Surface Enhanced Wireless Network: Joint Active and Passive Beamforming Design,” IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 5394–5409, Nov. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Bai, T.; Ren, H.; Deng, Y.; Elkashlan, M.; Nallanathan, A. “Resource Allocation for Intelligent Reflecting Surface Aided Wireless Powered Mobile Edge Computing in OFDM Systems,” IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 5389–5407, Aug. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Dai, L. “Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces for Simultaneous Wireless Information and Power Transfer,” IEEE Transactions on Communications, vol. 69, no. 7, pp. 4359–4371, Jul. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerckx, B.; Zhang, R. Wireless Information and Power Transfer—From RF Harvester Models to Signal Design. IEEE JSAC 2019, 37, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulwali, Z. S. A.; Alqahtani, A. H.; et al. A High-Performance Circularly Polarized Rectenna for Energy Harvesting. Sensors 2023, 23, 7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uko, M.; Ekpo, S.; Enahoro, S.; Elias, F. 5G–Satellite Integrated Networks for IoT in Smart Cities. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 3895–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Jiang, M.; Hou, S. A Chirped Characteristic-Tunable THz Source for Sensing. Sensors 2024, 24, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.; Ekpo, S.; George, J.; et al. Hybrid Power Divider and Combiner for Passive RFID Tag Energy Harvesting. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worka, C. E.; Khan, F. A.; et al. RIS-Assisted Non-Terrestrial Networks for 6G. Sensors 2024, 24, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; et al. Waveform Design for Integrated Sensing and Communication in High-Mobility Scenarios. Sensors 2024, 24, 1234. [Google Scholar]

- Sooriarachchi, S.; Perera, T.; Jayasinghe, D.; et al. Hybrid Switching Mechanisms for Energy-Efficient Indoor IoT Environments. Sensors 2025, 25, 5678. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, G.; Xu, J.; Huang, K.; Cui, S. “Integrating Sensing, Communication, and Power Transfer: Multi user Beamforming Design,” arXiv:2311.09028, Nov. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.09028.

- Lau, I.; Ekpo, S.; Zafar, M.; et al. Hybrid mmWave–Li-Fi Architecture for Variable Latency Communications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 42850–42861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enahoro, S.; Ekpo, S.; Gibson, A.; et al. Multi-Radio Frequency Antenna for Sub-6 GHz 5G Margin Enhancement. Proc. ASSET 2023. [CrossRef]

- Enahoro, S.; Ekpo, S.; Gibson, A.; et al. Multiband Monopole Antenna for 5G IoT. Proc. ASSET 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Khan, M.; Lee, J. Power Optimization in RIS-Assisted SWIPT Sensor Networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 9101. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q.; Razaviyayn, M.; Luo, Z.-Q.; He, C. “An Iteratively Weighted MMSE Approach to Distributed Sum-Utility Maximization for a MIMO Interfering Broadcast Channel,” IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, vol. 59, no. 9, pp. 4331–4340, Sept. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enahoro, S.; Ekpo, S.; Uko, M.; et al. Adaptive Beamforming for mmWave 5G MIMO Antennas. 2021 IEEE WAMICON. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Proposed sustainable THz-SWIPT framework: the RIS tile embeds low-rate THz transceivers for scene sensing, feeding an adaptive controller that co-optimizes beam steering and power splitting.

Figure 1.

Proposed sustainable THz-SWIPT framework: the RIS tile embeds low-rate THz transceivers for scene sensing, feeding an adaptive controller that co-optimizes beam steering and power splitting.

Figure 2.

Taxonomy of THz SWIPT research themes showing how this work addresses the sensing-adaptive green 6G gap.

Figure 2.

Taxonomy of THz SWIPT research themes showing how this work addresses the sensing-adaptive green 6G gap.

Figure 3.

Timeline of key milestones in RIS-aided SWIPT and THz rectenna research.

Figure 3.

Timeline of key milestones in RIS-aided SWIPT and THz rectenna research.

Figure 4.

Proposed RIS-enabled THz SWIPT system architecture with adaptive beam steering and ambient sensing.

Figure 4.

Proposed RIS-enabled THz SWIPT system architecture with adaptive beam steering and ambient sensing.

Figure 5.

Average per-UE harvested energy versus average per-UE achievable rate for all algorithms.

Figure 5.

Average per-UE harvested energy versus average per-UE achievable rate for all algorithms.

Figure 6.

Energy and eco-spectral efficiency versus RIS size.

Figure 6.

Energy and eco-spectral efficiency versus RIS size.

Figure 7.

User-equity and reliability performance.

Figure 7.

User-equity and reliability performance.

Figure 8.

Energy-efficiency variance versus RIS size (all algorithms).

Figure 8.

Energy-efficiency variance versus RIS size (all algorithms).

Figure 9.

Carbon cost per delivered bit versus RIS size.

Figure 9.

Carbon cost per delivered bit versus RIS size.

Figure 10.

Harvesting performance metrics under realistic non-linear EH models and diurnal load profiles.

Figure 10.

Harvesting performance metrics under realistic non-linear EH models and diurnal load profiles.

Figure 11.

System robustness and efficiency metrics under realistic environmental and hardware constraints.

Figure 11.

System robustness and efficiency metrics under realistic environmental and hardware constraints.

Figure 12.

Sensor deployment and hardware non-ideality analysis across all algorithms.

Figure 12.

Sensor deployment and hardware non-ideality analysis across all algorithms.

Figure 13.

Spatial SINR and environment-aware sensing utility trade-offs under APF beamforming.

Figure 13.

Spatial SINR and environment-aware sensing utility trade-offs under APF beamforming.

Figure 14.

Power safety, computational cost, and energy–rate trade-offs across algorithmic designs.

Figure 14.

Power safety, computational cost, and energy–rate trade-offs across algorithmic designs.

Figure 15.

Performance metrics normalised to per-metric maxima; raw values are annotated above each bar for transparency.

Figure 15.

Performance metrics normalised to per-metric maxima; raw values are annotated above each bar for transparency.

Table 1.

Comparative matrix of recent RIS/THz–SWIPT/ISAC literature.

Table 1.

Comparative matrix of recent RIS/THz–SWIPT/ISAC literature.

| Reference |

Venue/Year |

Band |

Non-linear EH |

Sensing |

THz |

Green metric |

Robustness †

|

Remark |

| [18] |

CSTut/2015 |

Sub-6 GHz |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

Survey |

| [19] |

TWC/2019 |

Sub-6 GHz |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

IRS beamforming baseline |

| [20] |

TWC/2021 |

mmWave |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

RIS + non-linear EH |

| [10] |

Sensors/2022 |

THz |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

Fixed RIS beam steering |

| [8] |

Sensors/2023 |

mmWave |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

Sensing-capable RIS |

| [13] |

Sensors/2023 |

mmWave |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

Secure beamforming |

| [12] |

Sensors/2024 |

mmWave |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

Vehicular ISAC RIS |

| [27] |

Sensors/2024 |

mmWave |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

LEO NTN scenario |

| This Work |

Sensors/2025 |

THz |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

Joint sensing–power focusing |

Table 2.

Comparison of Benchmark Schemes against Proposed APF Framework.

Table 2.

Comparison of Benchmark Schemes against Proposed APF Framework.

| Scheme |

RIS Adaptation |

Sensing Feedback |

EH Model |

Optimized |

| No RIS |

✗ |

✗ |

Linear |

✗ |

| Static RIS + Linear EH |

✗ |

✗ |

Linear |

✗ |

| Sensing RIS Only |

✓ |

✓ |

Linear |

✗ |

| Optimized Only |

✗ |

✗ |

Linear |

✓ |

| Blind APF |

✓ |

✗ |

Nonlinear |

✓ |

| Proposed APF |

✓ |

✓ |

Nonlinear |

✓ |

Table 4.

Performance Comparison of APF vs. Baseline Algorithms.

Table 4.

Performance Comparison of APF vs. Baseline Algorithms.

| Metric |

APF |

LinearEH |

StaticRIS |

NoRIS |

| Max Achievable Rate [Mbps] |

500 |

460 |

380 |

270 |

| Avg Harvested Energy [W] |

3.9 |

3.3 |

2.5 |

1.4 |

| EE Variance [bit/J2] |

0.022 |

0.041 |

0.058 |

0.082 |

| Peak SAR [W/kg] |

1.6 |

1.9 |

2.3 |

1.0 |

| Latency @ 90% Load [ms] |

9.5 |

13.5 |

18.2 |

22.0 |

| Coverage @ 150 Mbps [%] |

85 |

72 |

52 |

32 |

| Complexity [MFlops] |

120 |

70 |

52 |

19 |

Table 5.

Benchmarking the proposed sensing–adaptive THz-SWIPT framework against recent RIS-enabled SWIPT works.

Table 5.

Benchmarking the proposed sensing–adaptive THz-SWIPT framework against recent RIS-enabled SWIPT works.

| Reference |

Band |

|

Sensing |

SWIPT |

Peak Rate |

EH Gain |

SAR |

| |

|

|

|

Control |

[Mbps] |

(% vs NoRIS) |

Safe? |

| [21] |

5.8 GHz |

64 |

– |

Static |

85 |

48 |

✓ |

| [20] |

3.5 GHz |

100 |

– |

Adaptive |

52 |

40 |

✓ |

| [10] |

28 GHz |

64 |

– |

Static |

120 |

65 |

✓ |

| [13] |

28 GHz |

128 |

– |

Adaptive |

145 |

72 |

✓ |

| [23] |

5.8 GHz |

– |

– |

Rectenna only |

– |

110a

|

✓ |

| [30] |

2.4 GHz |

32 |

✓ |

Adaptive |

25 |

38 |

✓ |

| [27] |

Ka-band |

256 |

– |

Static |

180 |

94 |

✗ |

| [12] |

0.30 THz |

256 |

✓ |

Static |

190 |

98 |

✗ |

| This work (APF) |

0.30 THz |

256 |

✓ |

Adaptive |

350 |

125 |

✓ |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).