1. Introduction

Respiratory problems are among the most common and critical health concerns in pig production systems. These conditions adversely impact key production indicators such as average daily gain (ADG), feed conversion rate (FCR), and mortality rate, ultimately leading to increased production costs [

8] and reduced carcass quality. Many small-scale swine farmers are particularly vulnerable to these effects, with some even being forced to cease production altogether. The most important pathogens associated with respiratory diseases in pigs include Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome virus (PRRSv),

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (

Mh),

Pasteurella spp., Porcine Circovirus type 2 (PCV2), Swine Influenza virus, and Streptococcus spp. Among these, PRRSv and

Mh have been identified as the primary causes of respiratory illnesses in pigs, both globally and in Thailand [

4,

11,

16,

35].

PRRSv, an arterivirus, is classified into PRRSV-1 and PRRSV-2 genotypes [

2]. The virus replicates in alveolar macrophages and respiratory epithelial cells and is often associated with productive coughing in infected pigs [

35]. It can also cause systemic infections that result in reproductive failures [

17]. In Thailand, both genotypes are prevalent in swine-dense regions [

26]. For diagnostic purposes, blood samples were selected in this study due to their suitability for detecting infection in both acute and chronic stages [

13]. RT-PCR was employed for viral detection, a method with high sensitivity and reliability—even in asymptomatic or preclinical animals [

7,

20]. Notably, PRRSv is a major contributor to the Porcine Respiratory Disease Complex (PRDC), often co-infecting with PCV2 and

Mh [

34].

PCV2 is known to cause Postweaning Multisystemic Wasting Syndrome (PMWS), which leads to poor growth, emaciation, and chronic respiratory lesions [

10,

21]. Although its direct relationship to coughing is not well-defined, it plays a key role in respiratory disease complexity. In contrast,

Mh is the causative agent of enzootic pneumonia, which is typically characterized by non-productive coughs. This pathogen adheres to tracheal cilia, disrupting mucociliary clearance and predisposing the lung to secondary infections [

18]. Transmission occurs via aerosols or direct contact. Diagnostic samples often include lungs, trachea, or tonsils and are examined through PCR or culture. Importantly, different pathogens may produce distinct cough types: viral infections often cause productive coughs, while bacterial infections such as

Mh typically result in non-productive coughs [

6]. However, identifying cough types based on sound remains challenging due to the subjective nature of human perception [

23].

Because coughing is one of the earliest and most noticeable clinical signs of respiratory disease, the ability to detect and differentiate cough types accurately and early is crucial. Unfortunately, current diagnostic methods are reactive, invasive, and not always practical on commercial farms. This has driven interest in non-invasive, real-time surveillance tools. Syndromic surveillance, which emphasizes early recognition of abnormal signs before full outbreaks occur, provides a promising framework for such efforts. Recent technological developments in artificial intelligence (AI) have opened new possibilities for improving disease detection in swine production. AI has been used for activity monitoring, temperature analysis, weight estimation [

29], and even analyzing pig vocalizations to assess stress or pain [

27]. Importantly, machine learning algorithms have also been applied to classify pig coughing and background noise using spectrogram-based sound analysis [

30].

This study builds upon these developments by investigating the use of machine learning to classify pig coughs into productive and non-productive types and to assess their association with specific respiratory pathogens. The findings could support early disease detection and more precise health monitoring in pig farms, contributing to improved welfare and productivity.

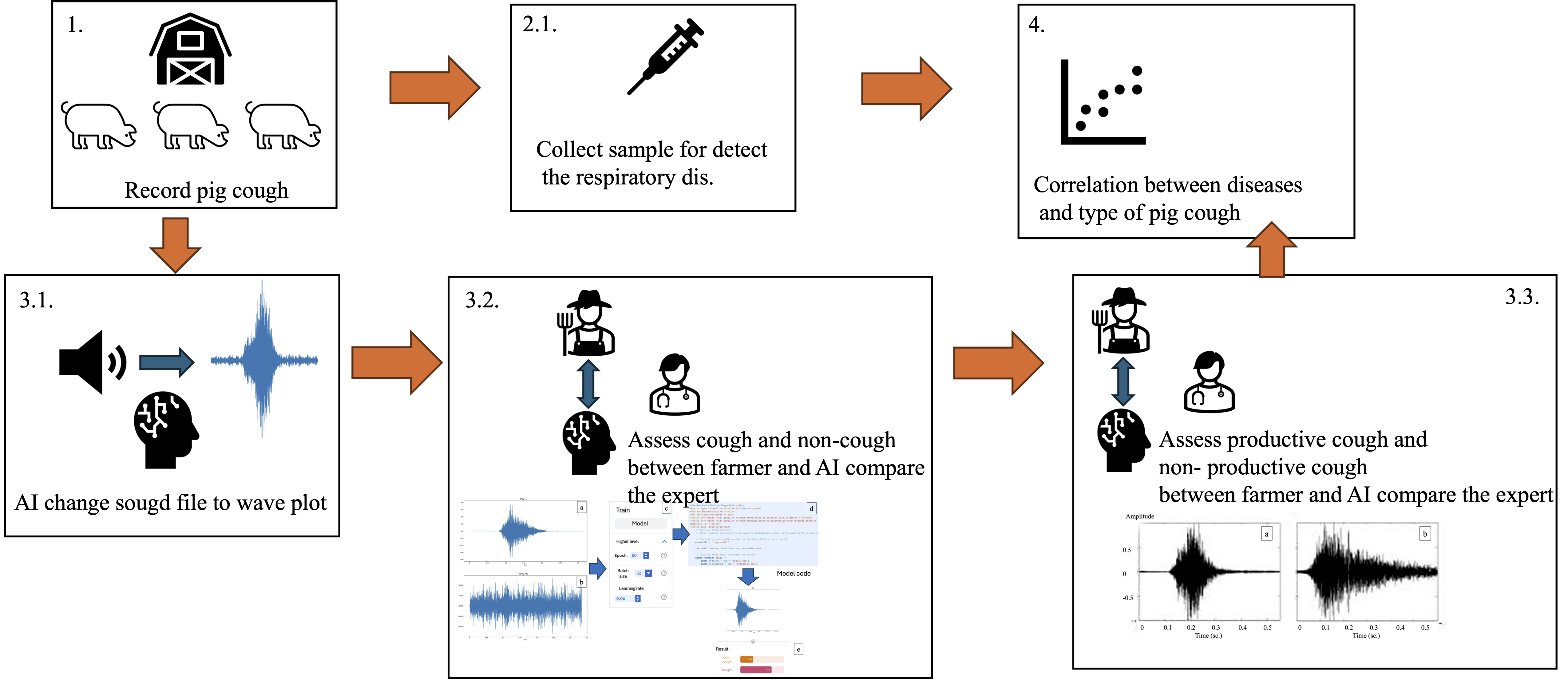

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sample Size for Coughing Pigs

Fattening pigs aged between 3 and 5 months, crossbred from Large White × Landrace and Duroc, were selected from small-holder farms affiliated with the Chiang Mai–Lamphun Pig Farmers Cooperative Limited. These farms had documented histories of coughing symptoms among fattening pigs. The required sample size of pigs exhibiting coughing symptoms was determined using G*Power software. A one-tailed hypothesis was employed, with a significance level (α) set at 0.05 and a statistical power (1 − β) of 0.95. Based on these parameters, the minimum sample size was calculated to be 34 pigs. Data collection and sample usage were approved by each participating farm, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Thailand (Approval No. S15-2567).

2.2. Recording of Pig Cough Sounds

The observation of coughing symptoms in fattening pigs was carried out at the participating farms. The pigs were stimulated to move around inside the pen for approximately 3 to 5 minutes, and then the coughing behavior was carefully observed by the farm owner at each farm. When a fattening pig was identified as coughing, it was marked with color spray as an indicator for further observation. After that, the pig farmer recorded the cough sound of the identified pig. Each sound file was labeled with a code that matched the specific pig that showed coughing symptoms. Before being processed using AI to convert the sound into a spectrogram image, each sound file was reviewed by an expert to confirm whether it was truly a pig cough or not. Furthermore, the sounds confirmed as pig coughs were then assessed by both the farmer and the expert to determine whether the cough was productive cough or non-productive cough. The recorded and verified sounds were later analyzed in a studio room, where the files were converted and used for further classification and analysis of sound types.

2.3. Conversion of Sound Data into Image

The recorded sound files were analyzed using a software program that was developed with Python programming language. The sound files were converted into wave plot images by using specific commands as shown below.

def plot_waves(y, sr):

file_path = 'sound_name.wav'

y, sr = librosa.load(file_path)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(60,25))

librosa.display.waveshow(np.array(y),sr=sr)

step = 0.2

duration = librosa.get_duration(y=y, sr=sr)

xticks = math.ceil(duration / step)

xticks = [x * step for x in range(xticks + 1)]

plt.suptitle("

Figure 1: Waveplot",x=0.5, y=0.915,fontsize=16)

plt.xlim(left=0, right=4)

plt.show()

plot_waves(y, sr)

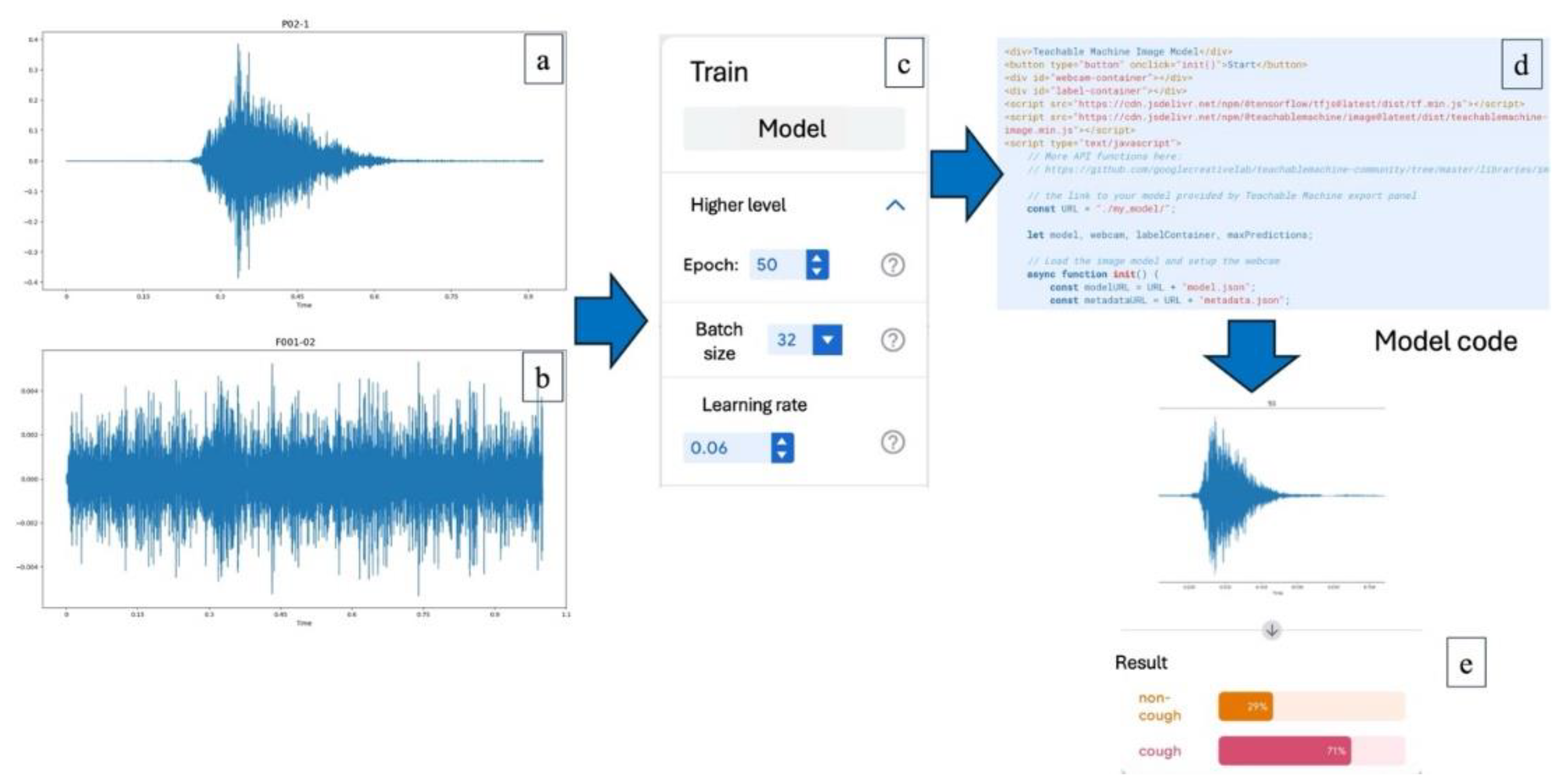

Training the AI System

In this process, the AI system was instructed to classify the spectrogram images into two categories: cough and non-cough. Once the images identified as cough were separated, the AI was further trained to distinguish between productive and non-productive cough images. These classifications were used to analyze correlations in subsequent steps. The wave plot images obtained from the sound data were used to train the AI system. The training process was conducted using Google Teachable Machine. The model was trained for 50 epochs, with a batch size of 32 and a learning rate set at 0.06, which was identified as the optimal parameter configuration based on preliminary analysis.

Figure 1.

Training the AI system to analyze pig cough sounds; (a) A wave plot representing a reference pig cough sound, (b) A wave plot of a non-cough sound used as a comparison, (c) Configuration parameters used in the AI training process via Google Teachable Machine, including 50 epochs, batch size of 32, and a learning rate of 0.06, (d) Example of the model code used to deploy the trained AI model for classification, (e) Output result from the AI analysis indicating classification confidence between "cough" and "non-cough" categories.

Figure 1.

Training the AI system to analyze pig cough sounds; (a) A wave plot representing a reference pig cough sound, (b) A wave plot of a non-cough sound used as a comparison, (c) Configuration parameters used in the AI training process via Google Teachable Machine, including 50 epochs, batch size of 32, and a learning rate of 0.06, (d) Example of the model code used to deploy the trained AI model for classification, (e) Output result from the AI analysis indicating classification confidence between "cough" and "non-cough" categories.

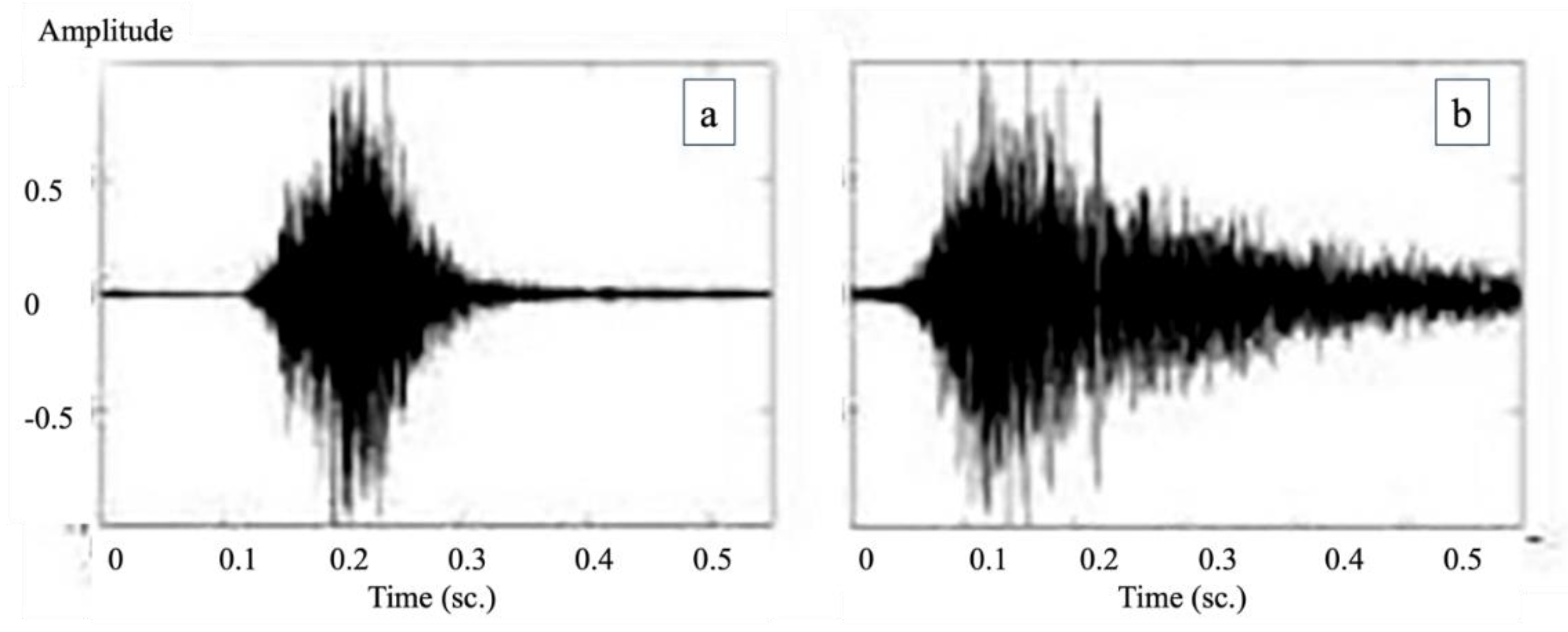

In the next step, the system was trained to distinguish between non-productive and productive coughs (

Figure 2). The method used was the same as the one for separating cough from non-cough sounds. However, the reference sounds used for training were changed to clearly identified samples of either non-productive or productive coughs, which had been reviewed and agreed upon by both the farmers and the veterinary experts. These sounds were then converted into spectrogram images and used to teach the AI to recognize the differences between the two types. This allowed for more accurate classification of pig coughs and helped support further analysis of pig health conditions on the farms.

2.4. Collection of Blood and Tonsil Swab Samples

The pigs that showed coughing symptoms were restrained using a snare, which was placed between the upper and lower jaw teeth. Then, a mouth gag was inserted into the pig’s mouth to keep it open. After that, a sterilized cotton swab was used to rub the surface of the tonsil gland, and the swab was placed into BHL medium broth. The sample was kept at a temperature of 4-8°C before being sent for laboratory analysis to detect Mh. For blood sample collection, 2 mL of blood was drawn from the pig’s jugular vein using a sterile EDTA tube. The blood samples were also kept at 4-8°C and then sent to the laboratory for further diagnosis of PRRS virus and PCV2 virus.

2.5. Real-Time RT-PCR Method for Diagnosis of PRRS Virus

The detection of PRRS virus (PRRSv) was performed using the real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (real-time RT-PCR) technique. The process began with the extraction of viral RNA, followed by amplification of the target RNA using PCR, which allows the monitoring of RNA amplification in real-time. RNA was extracted from the samples using a commercial RNA extraction kit. The extracted RNA solution was kept on ice during the entire testing process to prevent RNA degradation. The master mix for the one-step real-time RT-PCR reaction was prepared, including three control samples: positive control for Type 1, positive control for Type 2, and a negative control. The reaction was conducted using the LightCycler® multiplex RNA virus master (Roche GmbH, Germany). The 20 µl one-step real-time RT-PCR reaction included the following components: 1) 4.0 µl of 5 x RT-qPCR reaction mix, 2) 0.1 µl of 200x RT enzyme solution, 3) Primers at a final concentration of 500-600 nM, and 4) Probes at a final concentration of 250-300 nM.

The amplification of the target RNA was monitored in real-time by detecting the increase in specific fluorescence signals. For PRRS virus type 1, fluorescence was detected in the Cy5 channel, while for type 2, the HEX channel was used (

Table 1). The results were reported as cycle threshold (Ct or Cq), which indicates the cycle number at which a significant increase in fluorescence was observed. A typical amplification curve appeared in the form of an S-shaped (sigmoid or exponential) graph.

2.6. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) for Detection of Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2)

Detection of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) DNA was performed using a quantitative PCR (qPCR) protocol adapted from Franzo et al. (2018) [

9] and Yuan et al. (2014) [

31] (

Table 2). It is started that DNA was extracted from tonsil swab samples preserved in broth medium using a commercial DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted DNA was kept on ice during preparation to prevent degradation. Then, the qPCR reaction was prepared in a total volume of 20 µl, comprising the following components: 10.0 µl of 2× qPCR reaction mix, 400 nM of each forward and reverse primer and 200 nM of probe specific for PCV2. 1.0 µl of DNA template or control (positive or negative), Nuclease-free water to adjust to final volume Master mix (12.5 µl per tube) was aliquoted into PCR tubes, followed by the addition of 1.0 µl of extracted DNA. Positive and negative controls were included in each run. The negative control consisted of nuclease-free water. Thermal Cycling Conditions, the qPCR was conducted using a real-time thermal cycler under the following conditions: Initial denaturation: 95 °C for 10 minutes (1 cycle), Amplification: 95 °C for 15 seconds (45 cycles), Cooling: 25 °C for 45 seconds (1 cycle). And then fluorescence signals were monitored at each cycle to detect the specific amplification of the PCV2 target sequence. Results were reported based on the cycle threshold (Ct) values corresponding to exponential amplification curves.

2.7. Bacterial Culture and qPCR-Based Confirmation of Mycoplasma Hyopneumoniae.

The presence of

Mh was initially assessed by culturing samples in BBL™ Mycoplasma broth (BHL medium) at 37 °C. Cultures were monitored for color change, which indicates metabolic activity. In the absence of visible color change, blind passages were performed every 5–7 days for a total of 21 days to enhance bacterial recovery [

26]. DNA was extracted from the cultured broth using a commercial DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) targeting the Mhp183 gene, which is specific to

Mh to confirm the presence of the pathogen (

Table 3).

The qPCR amplification was performed under the following thermal cycling conditions: DNA polymerase activation at 95 °C for 15 minutes to activate the enzyme. Forty cycles of: Denaturation at 95 °C for 15 seconds, Combined annealing and extension at 60 °C for 60 seconds.

2.8. Statistical Analysis of the Relationship Between Coughing Symptoms and Pathogen Detection

Three types of evaluators including pig farmers, an artificial intelligence (AI) system, and the swine pratictioner expert were asked to interpret wave plots in order to determine whether the sound represented a cough and, if so, to classify the type of cough. The results of the analysis were used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of cough detection, as well as detection of non-productive coughs. These evaluations were performed for pig farmers vs. the AI system and the swine pratictioner expert vs. the AI system. The accuracy of cough identification and cough type classification was then compared using Bayesian probability theory. And also, the classification results for non-productive coughs were statistically analyzed in relation to PCR test results using Spearman’s correlation coefficient and the Kappa coefficient, implemented in the R statistical software. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Detection Results for Mycoplasma Hyopneumoniae (Mh), Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2), and Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSv)

Out of 49 tonsil swab samples, 10 samples tested positive for Mh. For Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2), 29 out of 49 blood samples showed positive results. In contrast, no positive results were found for PRRSv in any of the tested samples.

3.2. Probability Analysis of General Cough Detection

The sensitivity and specificity of pig farmers in identifying coughing sounds, as compared with the swine pratictioner expert, were 1.00 and 0.056, respectively. For the AI-based cough detection system, the sensitivity and specificity were 1.00 and 0.50, respectively, when benchmarked against swine experts. Bayesian probability analysis was used to determine the likelihood that each system correctly identified cough events. The posterior probabilities for accurate cough detection by pig farmers and by the AI system were 0.31 and 0.46, respectively. These results suggest that although both observers and AI systems are capable of recognizing cough events (high sensitivity), the AI system demonstrates greater ability in avoiding false positives (higher specificity), thereby providing a more balanced and reliable diagnostic outcome.

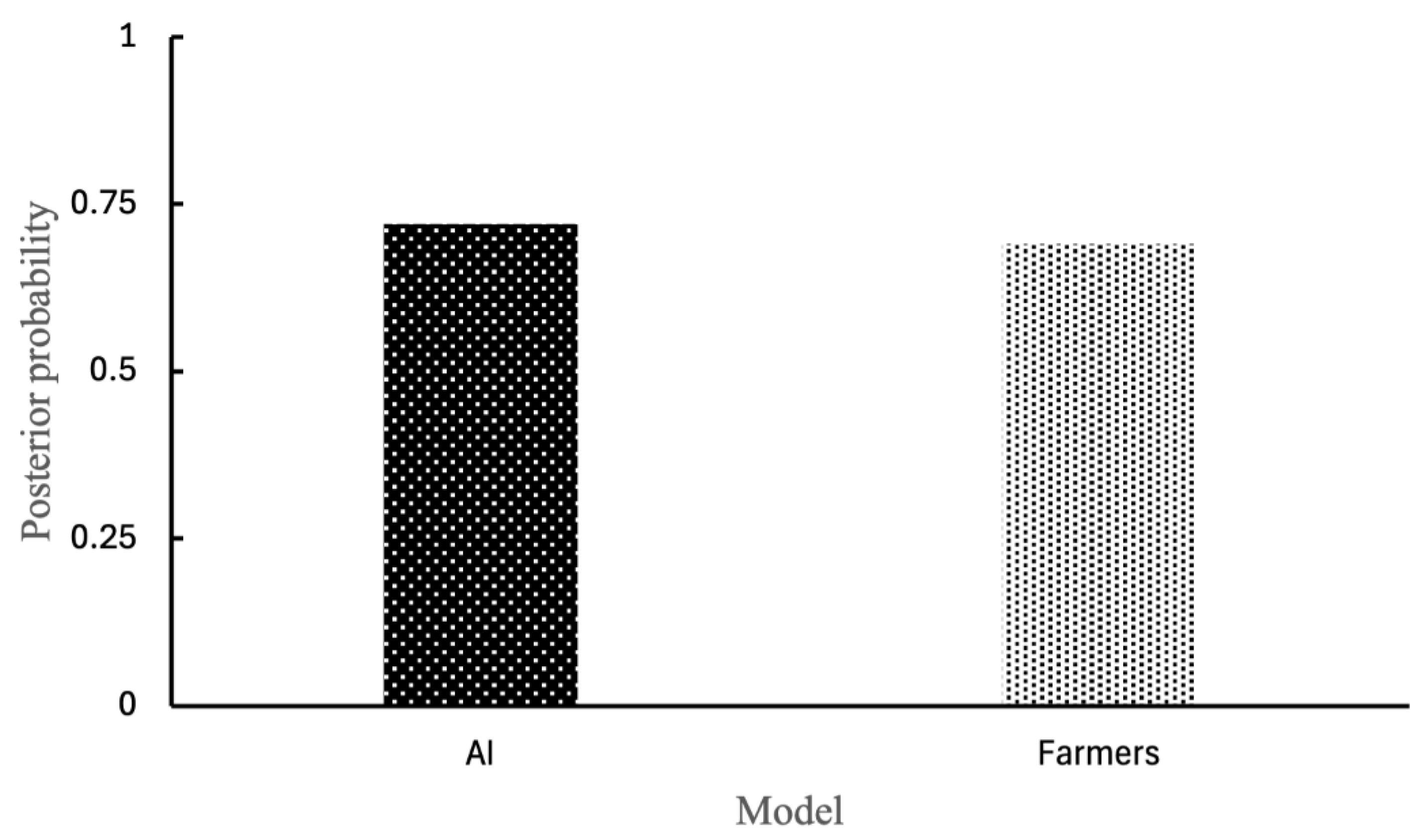

3.3. Probability Analysis of Non-Productive Cough Detection

In the identification of non-productive coughs (i.e., dry coughs), the sensitivity and specificity of pig farmers, compared to swine experts, were 0.80 and 0.85, respectively. The AI system showed slightly higher sensitivity (0.90) and equal specificity (0.85). Bayesian analysis of posterior probabilities revealed that the likelihood of correctly detecting a non-productive cough was 0.69 for pig farmers and 0.72 for the AI system (

Figure 3). These findings indicate that both human and AI systems have strong diagnostic performance in detecting non-productive coughs, with the AI system showing slightly better overall probability due to higher sensitivity.

3.4. Correlation Between Infection (PCV2 and Mh) and Coughing or Non-Productive Cough

To evaluate the relationship between respiratory infections and coughing symptoms, both Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (to assess monotonic association) and Cohen’s kappa coefficient (to assess agreement beyond chance) were used. The correlation between either PCV2 or

Mh infection and general coughing symptoms yielded a Spearman’s coefficient of 0.40 and a Cohen’s kappa of 0.36, indicating a moderate level of association and agreement between infection status and observed cough. In contrast, the correlation between PCV2 infection and non-productive cough was low, with a Spearman’s coefficient of 0.05 and a Cohen’s kappa of 0.037 (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Respiratory diseases in swine production remain one of the major concerns due to their impact on animal welfare and productivity. Among the early clinical signs, coughing is commonly observed; however, identifying and interpreting cough characteristics can be subjective when relying solely on human observers. In this study, we explored the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) to detect and classify coughs in pigs and investigated the association between cough characteristics and two major respiratory pathogens:

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (

Mh) and Porcine Circovirus type 2 (PCV2). Dry, non-productive cough is a characteristic clinical symptom of

Mh infection in pigs, especially when pigs are stimulated to move, as noted in clinical observations [

25]. Spectrogram and wave plot analysis has been shown to reliably distinguish infectious pig coughs from other ambient farm noises. In particular, Berckmans et al. (2008)[

3] demonstrated that coughs from infected pigs display distinctive wave plot patterns with longer duration and altered frequency content compared to healthy coughing or ambient sounds, as visualized in both time and frequency domain representations.

The results demonstrated that the AI system outperformed pig farmers in identifying general coughing sounds (0.46 vs. 0.31) and was particularly more effective in detecting non-productive (dry) coughs (0.72 vs. 0.69). Although the difference appears modest, the AI’s consistent and objective ability to classify cough types offers a clear advantage, especially in large-scale or continuous monitoring contexts. This finding aligns with prior research showing that AI-based acoustic monitoring systems can significantly enhance real-time animal health surveillance. For example, Zhao et al. (2020)[

33] developed a DNN–HMM acoustic model that effectively distinguished pig coughs, non-coughs, and silence segments with an improved Word Error Rate compared to conventional models. Similarly, a systematic review found that microphone-based cough detection systems can achieve accuracies between 73% and 93% in detecting respiratory distress in pigs, demonstrating their potential for welfare and health monitoring [

28].

When analyzing the relationship between cough type and pathogen detection, our findings indicated a moderate association between general coughing and combined detection of respiratory pathogens (PCV2 and

Mh), with Spearman’s rho of 0.40 and Cohen’s kappa of 0.36 (95% CI: 0.10–0.62). In contrast, the correlation between PCV2 and non-productive cough was weak (rho = 0.05; kappa = 0.037, 95% CI: –0.20–0.27), suggesting that PCV2 infection alone is not a reliable predictor of this clinical sign. These results align with previous reports demonstrating that PCV2 often plays a subclinical role or acts synergistically rather than as a primary respiratory pathogen. Notably, co-infection of PCV2 and

Mh has been experimentally shown to exacerbate lung lesions in PRDC models [

22,

32]. Conversely, some findings report minimal lung pathology in PCV2-only infections (Such variability underscores the complex interplay between PCV2 and other respiratory pathogens, reinforcing the need for longitudinal field studies to better delineate these relationships [

15].

In contrast, a strong correlation was observed between

Mh infection and non-productive coughs (Spearman’s rho = 0.80; kappa = 0.79, CI: 0.56–1.00). This finding is consistent with the pathophysiology of

Mh, which typically causes dry, persistent coughing due to the organism's ability to adhere to and damage ciliated epithelial cells in the respiratory tract [

14,

24]. In experimental co-infection studies,

Mh has been shown to induce chronic coughing when combined with other pathogens such as PCV2, reinforcing its role in respiratory disease complexes [

32]. Moreover, the high agreement between AI-detected dry coughs and laboratory-confirmed

Mh infection supports the potential of AI systems as effective screening tools. Recent studies have demonstrated that deep learning models can detect pig coughs with high accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity under commercial farm conditions [

5]. AI-based cough monitoring also enables earlier detection of

Mh outbreaks, which is crucial for timely intervention and reducing antibiotic use [

19]. The high kappa value observed in this study further reinforces the utility of AI as a proxy for clinical diagnosis, particularly in field settings where routine diagnostic testing is not always feasible.

These findings emphasize the usefulness of AI in pig farms, particularly for continuous and objective monitoring of respiratory symptoms. The ability to differentiate cough types and correlate them with specific pathogens like Mh provides a promising avenue for non-invasive early warning systems. However, some limitations should be noted. The relatively small sample size (n = 49) may have influenced the statistical power, especially regarding the PCV2 group. Additionally, environmental noise and the presence of multiple pigs in the same enclosure could affect acoustic detection accuracy.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential of artificial intelligence systems in improving the detection and classification of coughs in pigs, with a particular strength in identifying non-productive coughs associated with Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Future research should focus on expanding sample sizes, incorporating real-time AI models in farm environments, and integrating multimodal data such as temperature, behavior, and video imaging to enhance diagnostic precision. Additionally, longitudinal studies can assess the predictive value of AI-detected coughs over time and determine whether such systems can be integrated into automated decision-support tools for veterinarians and farm managers.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—review and editing, Panuwat Yamsakul; Sample collection, Investigation, Data curation, Terdsak Yano and Kiettipoch Junchum; Methodology, Laboratory, Wijitra Anukul and Nattinee Kittiwan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Faculty of veterinary medicine, Chiang Mai university, Thailand.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Thailand (Approval No. S15-2567).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Relevant information is included in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank the faculty of veterinary medicine, Chiang Mai university, Thailand for supporting the budget.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Babbs, C.F. Biomechanical models of cough sounds in pneumonia: Mechanisms underlying sound-based diagnosis in low-resource settings. Purdue e-Pubs 2020. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cophstuph/1 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Bálint, Á.; Molnár, T.; Kecskeméti, S.; Kulcsár, G.; Soós, T.; Szabó, P.M.; Kaszab, E.; Fornyos, K.; Zádori, Z.; Bányai, K.; Szabó, I. Genetic variability of PRRSV vaccine strains used in the national eradication programme, Hungary. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berckmans, D.; Moshou, D.; Chen, L.; Ramon, H. A sound-based monitoring system for the detection of coughing in pigs. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 63, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonsoongnern, A.; Jirawattanapong, P.; Lertwatcharasarakul, P.; Phatthanakunanan, S.; Poolperm, P.; Urairong, S.; Navasakuljinda, W.; Urairong, K. The prevalence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in commercial suckling pigs in Thailand. World J. Vaccines 2012, 2, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Lee, H.; Kang, H.; Park, S.J.; Choi, Y.; Cho, K.H. Sound-based detection of swine respiratory disease using deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 183, 106055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Oh, S.; Lee, J.; Park, D.; Chang, H.H.; Kim, S. Automatic detection and recognition of pig wasting diseases using sound data in audio surveillance systems. Sensors (Basel) 2013, 13, 12929–12942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, U.; Lee, C.S.; Kim, J.W.; Chae, C.K. Efficacy of blood-based RT-PCR for early detection of PRRSV in preclinical swine populations. J. Vet. Diagn. 2020, 32, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Silva, M.; Guarino, M.; Aerts, J.M.; Berckmans, D. Cough sound analysis to identify respiratory infection in pigs. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 64, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Segalés, J. Porcine circovirus 2 (PCV-2) genotype update and proposal of a new genotyping methodology. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.; Opriessnig, T.; Meng, X.J.; Pelzer, K.; Buechner-Maxwell, V. Porcine circovirus type 2 and porcine circovirus-associated disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2009, 23, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantafong, T.; Sangtong, P.; Saenglub, W.; Mungkundar, C.; Romlamduan, N.; Lekchareonsuk, C.; Lekcharoensuk, P. Genetic diversity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in Thailand and Southeast Asia from 2008 to 2013. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 176, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiboeker, S.B.; Schommer, S.K.; Lee, S.-M.; Watkins, S.; Chittick, W.; Polson, D. Simultaneous detection of North American and European porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus using real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase–PCR. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2005, 17, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Pelaez, A.A.; Fernandez, M.A.; Santos, F.R.; Delgado, F.G. Comparison of serum and whole blood sampling for PRRSV RT-PCR detection in field conditions. Vet. Microbiol. 2022, 270, 109117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, D.; Segalés, J.; Meyns, T.; Sibila, M.; Pieters, M.; Haesebrouck, F. Control of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae infections in pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2008, 126, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opriessnig, T.; Meng, X.J.; Halbur, P.G. Experimental reproduction of PMWS in pigs with dual infection of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and PCV2. Vet. Pathol. 2004, 41, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, M.G.; Maes, D. Mycoplasmosis. In Diseases of Swine, 11th ed.; Zimmerman, J.J., Karriker, L.A., Ramirez, A., Schwartz, K.J., Stevenson, G.W., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 863–883. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, C.; Castro, J.M. Pathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in gestating sows. Vet. Res. 2000, 31, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottem, S. Interaction of mycoplasmas with host cells. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Takemoto, M.; Tanaka, S.; Oishi, K. Validation of a real-time monitoring system for pig cough detection in commercial farms using AI and its application to early disease surveillance. Animals 2023, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R.P.; Garcia, M.S.; Martinez, L.C. Field evaluation of RT-PCR for PRRSV in blood and oral fluids. Swine Health Prod. 2016, 24, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Segalés, J.; Allan, G.M.; Domingo, M. Circoviruses. In Diseases of Swine, 11th ed.; Zimmerman, J.J., Karriker, L.A., Ramirez, A., Schwartz, K.J., Stevenson, G.W., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 473–487. [Google Scholar]

- Segalés, J.; Domingo, M. Porcine circovirus 2 lung disease: characterized by respiratory distress and dyspnea. Int. Anim. Health J. 2002, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.; Ji, N.; Yin, Y.; Dai, B.; Tu, D.; Sun, B.; Hou, H.; Kou, S.; Zhao, Y. Fusion of acoustic and deep features for pig cough sound recognition. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 197, 107014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibila, M.; Pieters, M.; Molitor, T.; Maes, D.; Haesebrouck, F.; Segalés, J. Current perspectives on the diagnosis and epidemiology of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae infection. Vet. J. 2009, 181, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.A.P.S.; Storino, G.Y.; Ferreyra, F.S.M.; Zhang, M.; Fano, E.; Polson, D.; Wang, C.; Derscheid, R.J.; Zimmerman, J.J.; Clavijo, M.J. Cough associated with the detection of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae DNA in clinical and environmental specimens under controlled conditions. Porc. Health Manag. 2022, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanapongtharm, W.; Linard, C.; Pamaranon, N.; Kawkalong, S.; Noimoh, T.; Chanachai, K.; Parakgamawongsa, T.; Gilbert, M. Spatial epidemiology of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in Thailand. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzanidakis, C.; Simitzis, P.; Arvanitis, K.; Panagakis, P. An overview of the current trends in precision pig farming technologies. Livest. Sci. 2021, 249, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathes, C.M.; Kristensen, H.H.; Aerts, J.-M.; Berckmans, D. A systematic review on validated precision livestock farming technologies for pig production and its potential to assess animal welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 674038. [Google Scholar]

- Yamsakul, P.; Yano, T.; Na Lampang, K.; Khamkong, M.; Srikitjakarn, L. Infrared temperature sensor for use among sow herds. Vet. Integr. Sci. 2022, 21, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamsakul, P.; Yano, T.; Na Lampang, K.; Khamkong, M.; Srikitjakarn, L. Classification and correlation of coughing sounds and disease status in fattening pigs. Vet. Integr. Sci. 2023, 21, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Sun, M.; Zheng, Y.; Qi, Y.; Sun, J.; Song, Q. Rapid detection of porcine circovirus type 2 by TaqMan-based real-time polymerase chain reaction assays. Int. J. Appl. Res. Vet. Med. 2014, 12, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Oh, T.; Park, K.H.; Cho, H.; Chae, C. A dual swine challenge with Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2) and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae used to compare vaccine types. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 954213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Liu, W.H.; Gao, Y.; Lei, M.G.; Tan, H.Q.; Yang, D. DNN–HMM based acoustic model for continuous pig cough sound recognition. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2020, 13, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, J.Z. Analysis of co-infection dynamics in PRRSV+PCV2 and PRRSV+Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in swine herds. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J.J.; Dee, S.A.; Holtkamp, D.J.; Murtaugh, M.P.; Stadejek, T.; Stevenson, G.W.; Torremorell, M.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses (porcine arteriviruses). In Diseases of Swine, 11th ed.; Zimmerman, J.J., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 685–708. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).