Submitted:

16 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

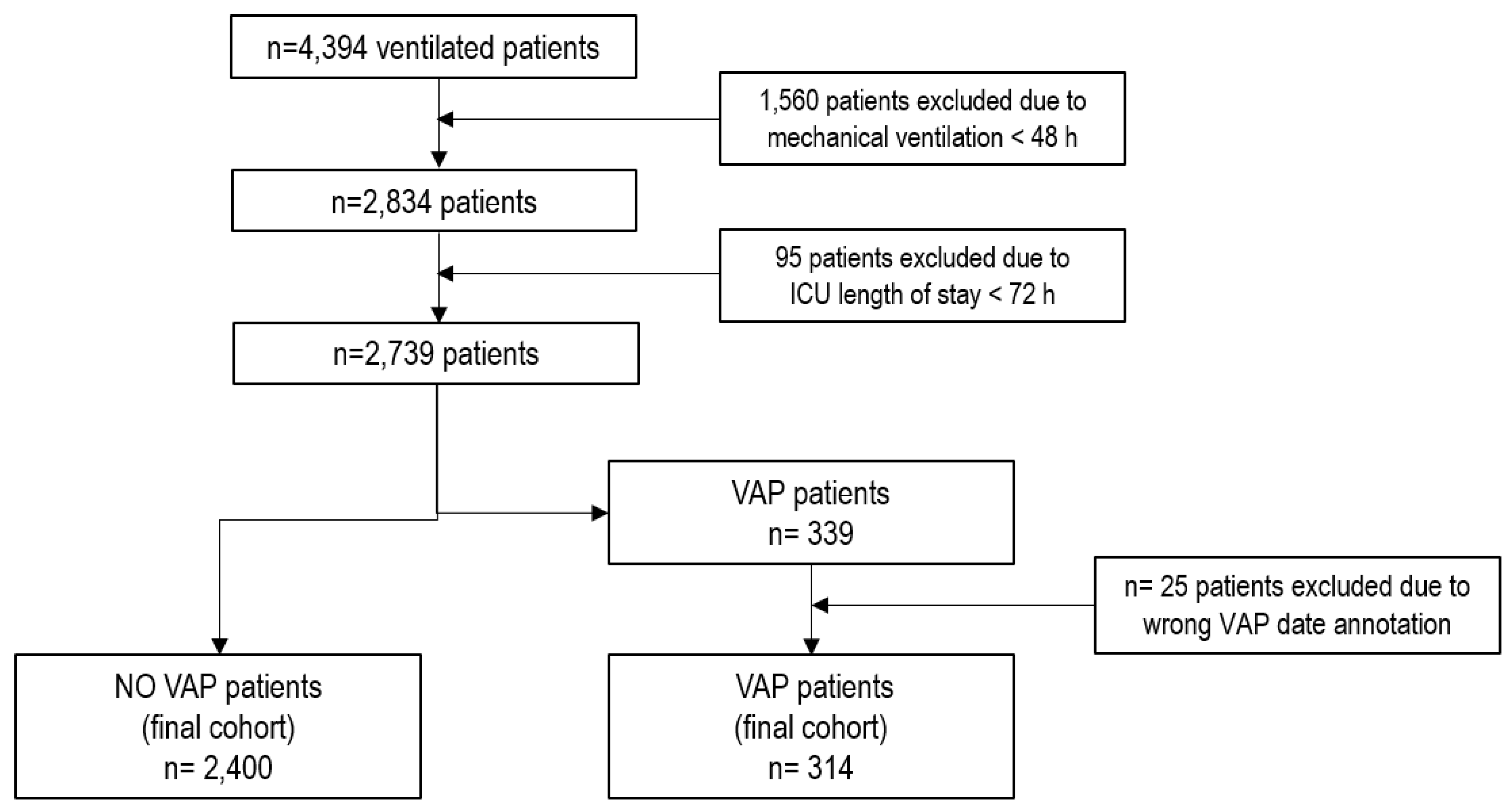

2.2. Population

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Missing Data Imputation

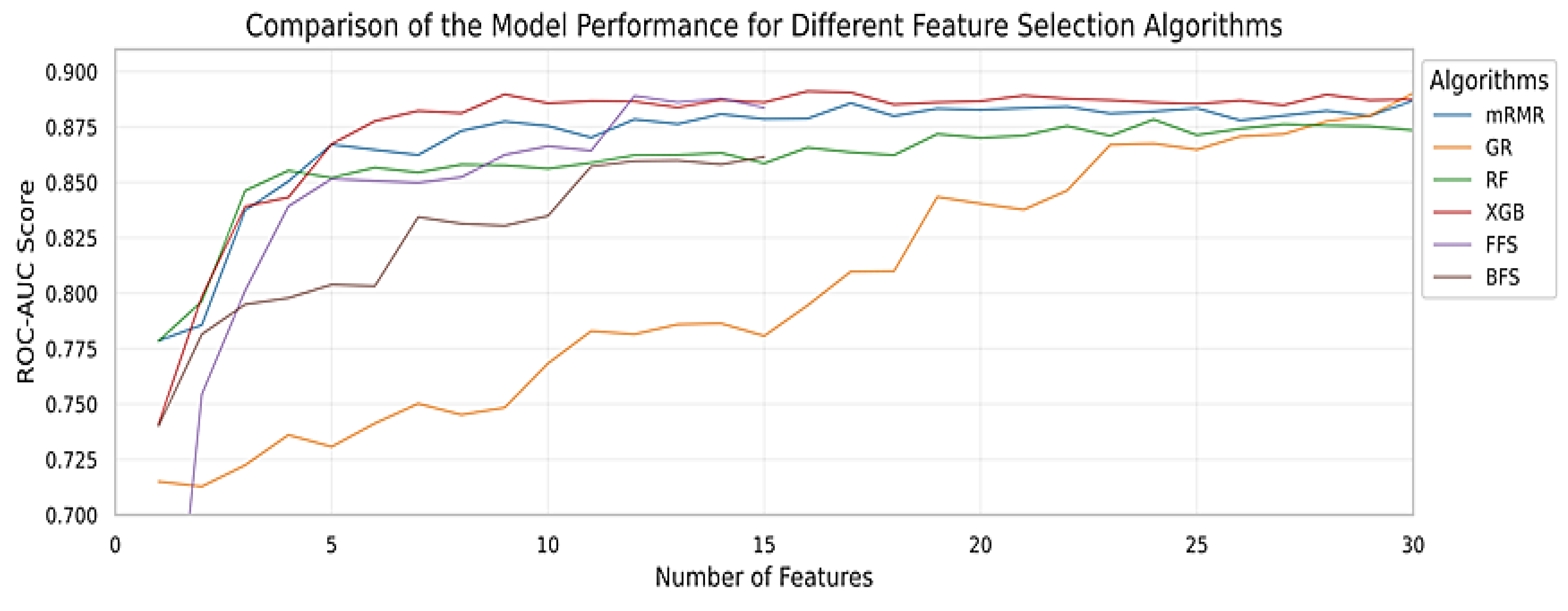

2.3.2. Feature Selection

2.4. Models

2.4.1. Data Splitting

2.4.2. Class Imbalance

2.4.3. Hyperparameter Tuning

2.4.4. Model Explainability

2.5. Definitions

2.6. Objectives

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population

3.2. Models Performance

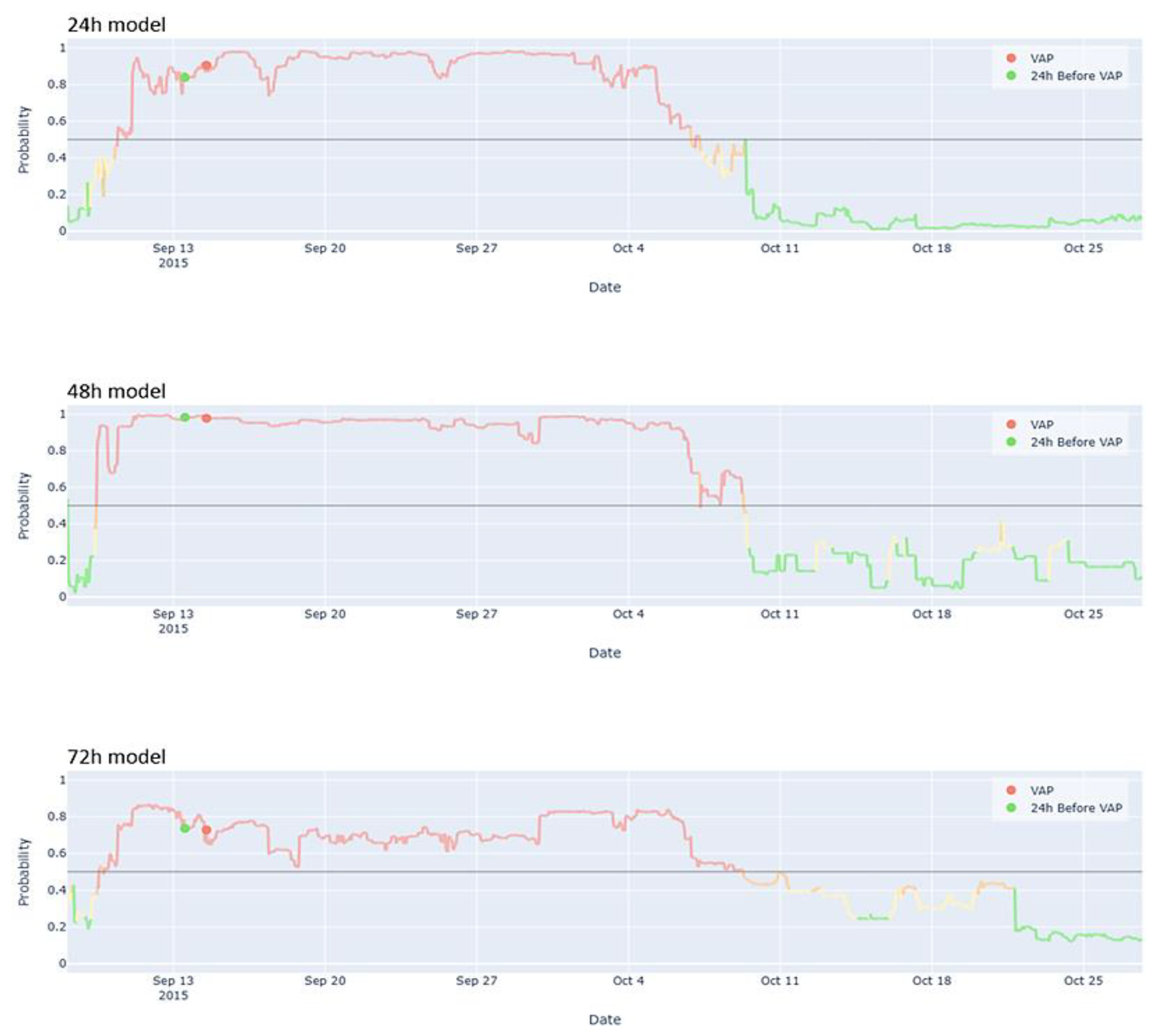

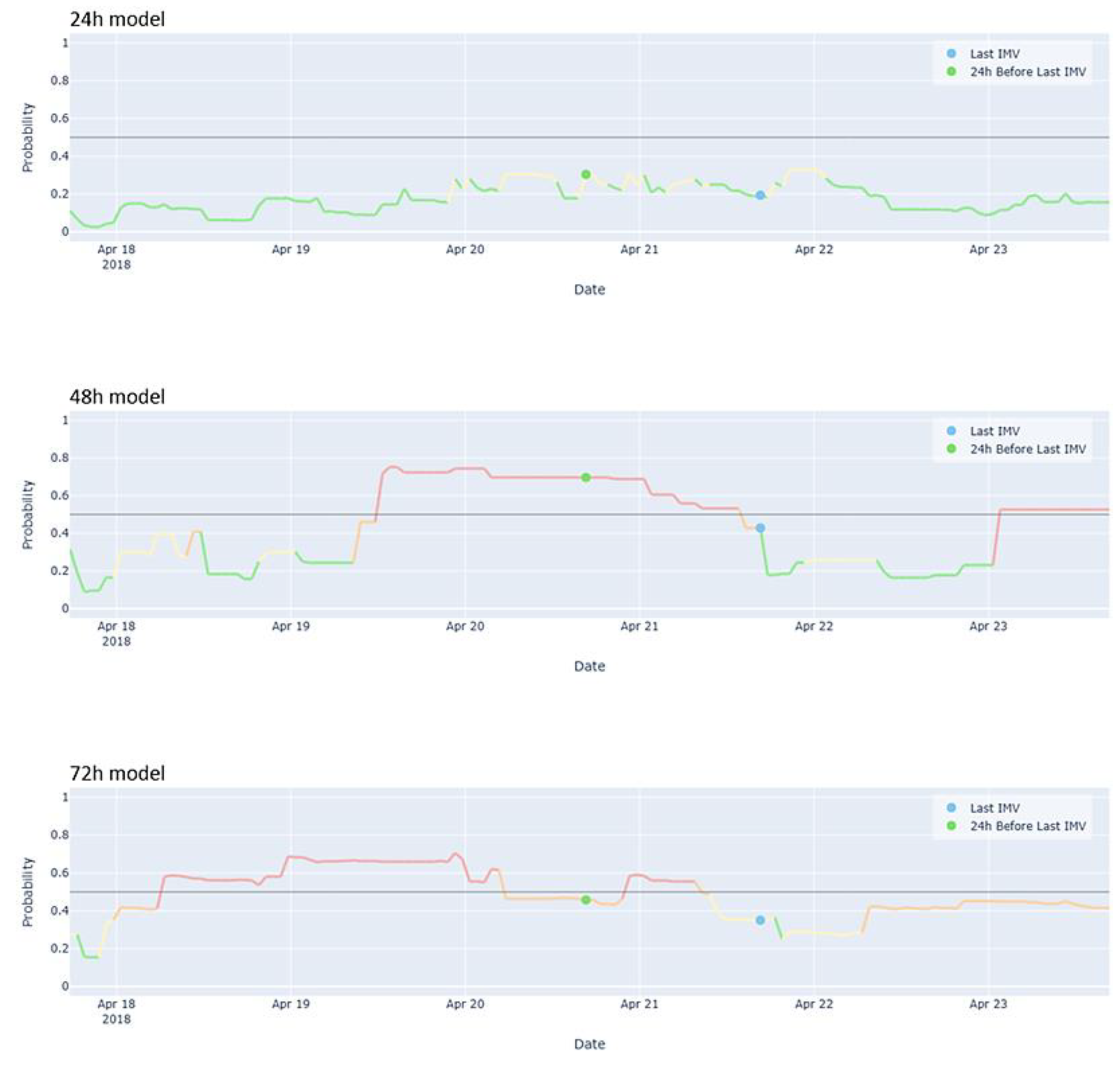

3.3. User-Friendly Model Visualization

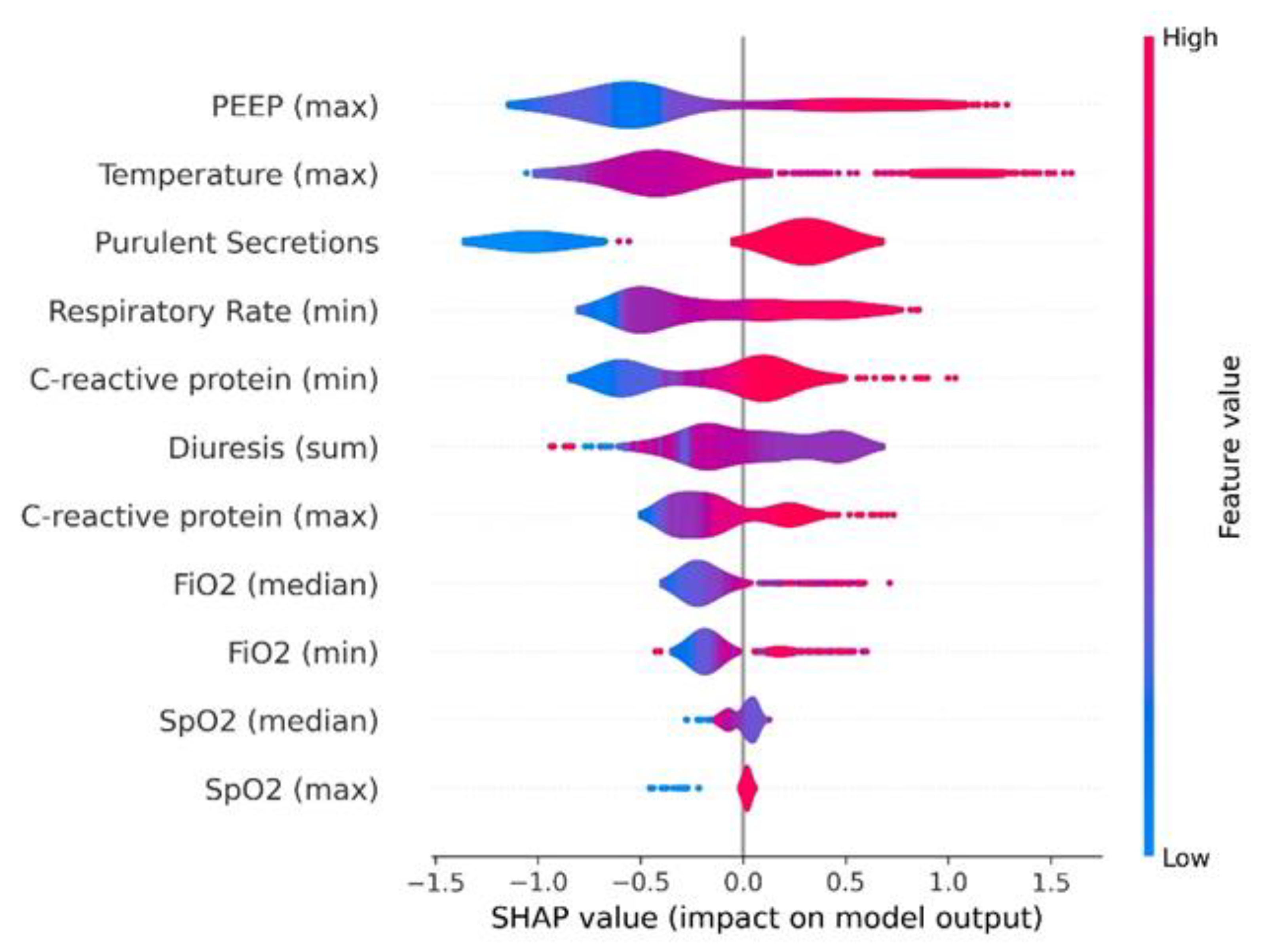

3.4. Model Explainability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| XGBoost | Extreme gradient boosting |

| mRMR | Minimum Redundancy-Maximum Relevance |

| GR | Gain Ratio |

| FFS | Forward Feature Selection |

| BFS | Backward Feature Selection |

| AUC | Area under curve |

References

- Howroyd, F.; Chacko, C.; MacDuff, A.; Gautam, N.; Pouchet, B.; Tunnicliffe, B.; Weblin, J.; Gao-Smith, F.; Ahmed, Z.; Duggal, N.A.; Veenith, T. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: pathobiological heterogeneity and diagnostic challenges. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papazian, L.; Klompas, M. ; Luyt, C-E. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med 2020, 46, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erb, C.T.; Patel, B.; Orr, J. E.; Bice, T.; Richards, J.B.; Metersky, M.L.; Wilson, K.C.; Thomson, C.C. Management of Adults with Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016, 13, 2258–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalil, A.C.; Metersky, M.L.; Klompas, M.; Muscedere, J.; Sweeney, D.A.; Palmer, L.B.; Napolitano, L.M.; O’Grady, N.P.; Bartlett, J.G.; Carratalá, J.; et al. Executive summary: management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 2016, 63, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalanuria, A.A.; Zai, W.; Mirski, M. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in the ICU. Crit Care. 2014, 18, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael Klompas, M. Does This Patient Have Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia? JAMA 2007, 297, 1583–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirtland, S.H.; Corley, D.E.; Winterbauer, R.H.; Springmeyer, S.C.; Casey, K.R.; Hampson, N.B.; Dreis, D.F. The diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a comparison of histologic, microbiologic, and clinical criteria. Chest. 1997, 112, 445–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto,K. ; Houlihan, C.; Balas, A.; Lobach, D. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: A systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ 2005, 330, 765. [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.J.; Schwartz, A.; Weaver, F.; Galanter, W.; Olender, S.; Kochendorfer, K.; Binns-Calvey, A.; Saini, R.; et al. Effect of Electronic Health Record Clinical Decision Support on Contextualization of Care A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022, 5, e2238231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.J.; Kelly, B.; Ashley, N.; Binns-Calvey, A.; Sharma, G.; Schwartz, A.; Weaver, F.M. Content coding for contextualization of care: evaluating physician performance at patient-centered decision making Med Decis Making 2014, 34, 97-106. [CrossRef]

- Manrique, S.; Ruiz-Botella, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Gordo, F.; Guardiola, J.J.; Bodí, M.; Gómez, J. ; on behalf the Advanced Analysis of Critical Data (AACD)Research Group. Secondary use of data extracted from a clinical information system to assess the adherence of tidal volume and its impact on outcomes. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2022, 46, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, D.; Riaño, D.; Gómez, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Bodí, M. Methods and measures to quantify ICU patient heterogeneity. J Biomed Inform. 2021, 117, 103768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabregat, A.; Magret, M.; Ferré, J.A.; Vernet, A.; Guasch, N.; Rodríguez, A.; Gómez, J.; Bodí, M. A Machine Learning decision-making tool for extubation in Intensive Care Unit patients. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 200, 105869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Emanuel, E.J. Predicting the Future — Big Data, Machine Learning, and Clinical Medicine. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 1216–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Dean, J.; Kohane, I. Machine Learning in Medicine. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravid Shwartz-Ziv, R.; Armon, A. Tabular data: Deep learning is not all you need. Information Fusion 2022, 81, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J. ; Hastie,T. ; Robert Tibshirani, R. Additive logistic regression: a statistical view of boosting. Ann. Statist 2000, 28, 337–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. “Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework,” in Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, ser. KDD ’19, Anchorage, AK, 2019, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; pp. 2623–2631. [CrossRef]

- Metersky, M.L.; Wang, Y.; Klompas, M.; Eckenrode, S.; Bakullari, A.; Eldridge, N. Trend in ventilator-associated pneumonia rates between 2005 and 2013. JAMA 2016, 316, 2427–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Ala-Kokko, T.; Ahvenjärvi, L.; Karhu, J.; Ohtonen, P.; Syrjälä, H. What is the applicability of a novel surveillance concept of ventilator-associated events? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017, 38, 983–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claverías, L.; Gómez, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Albiol, J.; Esteban, F.; Bodí, M. Support to the organization of the Intensive Care Units during the pandemic through maps created from the Clinical Information Systems. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2021, 45, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodí, M.; Claverias, L.; Esteban, F.; Sirgo, G.; De Haro, L.; Guardiola, J.J.; Gracia, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Gómez, J. Automatic generation of minimum dataset and quality indicators from data collected routinely by the clinical information system in an intensive care unit. Int J Med Inform. 2021, 145, 104327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Estrada, S.; Lagunes, L.; Peña-López, Y.; Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Nseir, S.; Arvaniti, K.; et al. Assessing predictive accuracy for outcomes of ventilator-associated events in an international cohort: the EUVAE study. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 1212–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, S.M.; Tran, A.; Cheng, W.; Klompas, M.; Kyeremanteng, K.; Mehta, S.; et al. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill adult patients-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1170–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirracchio, R.; Cohen, M.J.; Malenica, I.; Cohen, J.; Chambaz, A.; Cannesson, M.; et al. Big data and targeted machine learning in action to assist medical decision in the ICU. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019, 38, 377–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, M.; Rubio, J.; Gavaldà, R.; Rello, J. Artificial intelligence for clinical decision support in critical care, required and accelerated by COVID-19. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020, 39, 691–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuckchady, D.; Heckman, M.G.; Diehl, N.N.; Creech, T.; Carey, D.; Domnick, R.; Hellinger, W.C. Assessment of an automated surveillance system fordetection of initial ventilator-associated events. American Journal of Infection Control 2015, 43, 1119–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.P.; Silva, G.; Gillis, J.; Novack, V.; Talmor, D.; Klompas, M.; Howell, M.M. Automated Surveillance for Ventilator-Associated Events. CHEST 2014, 146, 1612–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Gao, F.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, M.; Xiong, L. Does ventilator associated event surveillance detect ventilator associated pneumonia in intensive care units? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2016, 20, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y-H. ; Shih, C-H.; Abbod, M.F.; Sheih, J.S.; Hsiao, Y.J. Development of an E-nose system using machine learning methods to predict ventilatorassociated pneumonia. Microsystem Technologies 2022, 28, 341–351. [CrossRef]

- Liao YH, Wang ZC, Zhang FG, Abbod MF, Shih CH, Shieh JS. Machine learning methods applied to predict ventilator-associated pneumònia with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection via sensor array of electronic nose in intensive care unit. Sensors 2019, 19, 1866. [CrossRef]

- Giang, C. ; Calvert,J. ; Rahmani, K.; Barnes, G.; Siefkas, A.; Green-Saxena, A.; et al. Predicting ventilator-associated pneumonia with machine learning. Medicine 2021, 100, e26246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang,Y. ; Zhu, C.; Tian, C.; Lin,Q.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Dongshu Ni, D.; Ma, X. Early prediction of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critical care patients: a Machine learning model. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2022, 22, 250. [CrossRef]

- Samadani, A.; Wang, T.; van Zon, K.; Leo Anthony Celi, L. VAP risk index: Early prediction and hospital phenotyping of ventilator-associated pneumonia using machine learning. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2023, 146, 102715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodí, M.; Samper, M.A.; Sirgo, G.; Esteban, F.; Canadell, L.; Berrueta, J.; Gómez, J.; Rodríguez, A. Assessing the impact of real-time random safety audits through full propensity score matching on reliable data from the clinical information system. Int J Med Inform. 2024, 184, 105352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirgo, G.; Samper, M.A.; Berrueta, J.; Cañellas, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Bodí, M. Reformulating real-time random safety analysis during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2024, 28, 502117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodí, M.; Oliva, I.; Martín, M.C.; Sirgo, G. Real-time random safety audits: A transforming tool adapted to new times. Med Intensiva. 2017, 41, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodí, M.; Oliva, I.; Martín, M.C.; Gilavert, M.C.; Muñoz, C.; Olona, M.; Sirgo, G. Impact of random safety analyses on structure, process and outcome indicators: multicentre study. Ann Intensive Care. 2017, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee,J. ; Maslove, D.M.; Dubin, J.A. Personalized mortality prediction driven by electronic medical data and a patient similarity metric. PloS One 2015, 10, e0127428. [CrossRef]

- Frondelius,T.; Atkova, I.; Jouko Miettunen, J.; Rello, J.; Jansson, M.M. Diagnostic and prognostic prediction models in ventilator-associated pneumonia: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction modelling studies. Journal of Critical Care 2022, 67. [CrossRef]

- Lekadir, K.; Frangi, A.F; Porras, A.R.; Glocker, B. ; Cintas,C. ; Langlotz, C.P. et al. FUTURE-AI: international consensus guideline for trustworthy and deployable artificial intelligence in healthcare. BMJ 2025, 388, e081554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Whole Population (n = 2714) |

Non-VAP (n = 2400) |

VAP (n = 314) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 1843 (67.9) | 1609 (67.0) | 234 (74.5) | 0.009 |

| Age, median (Q1-Q3) years | 64 (52-72) | 64 (52-72) | 62 (50-71) | 0.027 | |

| Admission type, n (%) | Urgent | 2586 (95.3) | 2286 (95.2) | 300 (95.5) | 0.930 |

| Patient type, n (%) | Medical | 1737 (64.0) | 1507 (62.8) | 230 (73.2) | <0.001 |

| Surgical | 938 (34.6) | 860 (35.8) | 78 (24.8) | ||

| Traumatic | 39 (1.4) | 33 (1.4) | 6 (1.9) | ||

| ICU LOS, median (Q1-Q3) days | 8.1 (3.9-16.4) | 8.2 (3.8-16.7) | 7.9 (4.9-13.9) | 0.709 | |

| IMV days, median (Q1-Q3) days | 7.9 (4.4-15.3) | 7.9 (4.3-15.5) | 8.1 (5.3-13.3) | 0.278 | |

| SOFA score median, median (Q1-Q3) | 4 (2-7) | 4 (2-6) | 5 (3-7) | 0.001 | |

| First APACHE II, median (Q1-Q3) | 23 (17-29) | 23 (17-29) | 20 (15-25) | <0.001 | |

| Tracheostomy, n (%) | Yes | 382 (14.1) | 353 (14.7) | 29 (9.2) | 0.011 |

| Ventilator Settings | |||||

| FiO2 median, median (Q1-Q3) % | 35 (30-40) | 31 (30-40) | 45 (35-60) | <0.001 | |

| FiO2 max, median (Q1-Q3) % | 40 (30-99) | 40 (30-98.8) | 90.5 (50-100) | <0.001 | |

| FiO2 min, median (Q1-Q3) % | 30 (28-35) | 30 (28-35) | 40 (31-50.5) | <0.001 | |

| PEEP median, median (Q1-Q3) cmH2O | 6 (5-8) | 6 (5-7.9) | 8 (6-11) | <0.001 | |

| PEEP max, median (Q1-Q3) cmH2O | 7 (5-8.9) | 6.7 (5-8) | 10 (8-14) | <0.001 | |

| PEEP min, median (Q1-Q3) cmH2O | 5 (1.8-6) | 5 (1.6-6) | 6 (4.1-9.1) | <0.001 | |

| Vital Signs | |||||

| Tª median, median (Q1-Q3) ºC | 36.5 (36-37) | 36.5 (36-36.9) | 37 (36.5-37.4) | <0.001 | |

| Tª max, median (Q1-Q3) ºC | 37.1 (36.6-37.6) | 37 (36.6-37.5) | 37.8 (37.2-38.3) | <0.001 | |

| Tª min, median (Q1-Q3) ºC | 35.8 (35.3-36.3) | 35.8 (35.3-36.2) | 36.1 (35.5-36.6) | <0.001 | |

| SpO2 median, median (Q1-Q3) % | 98 (96-99) | 98 (96-99) | 97 (95-98) | <0.001 | |

| SpO2 max, median (Q1-Q3) % | 100 (100-100) | 100 (100-100) | 100 (100-100) | 0.135 | |

| SpO2 min, median (Q1-Q3) % | 89 (82-92) | 89 (82-93) | 87 (83-91) | 0.008 | |

| RR median, median (Q1-Q3) bpm | 18 (16-22) | 18 (16-21) | 21 (18-24) | <0.001 | |

| RR max, median (Q1-Q3) bpm | 34 (28-43) | 34 (28-43) | 32.5 (26-41) | 0.075 | |

| RR min, median (Q1-Q3) bpm | 13 (10-16) | 13 (9.8-16) | 17 (15-20) | <0.001 | |

| Laboratory | |||||

| WBC median, median (Q1-Q3) x103 | 10.8 (8.1-14.9) | 10.5 (8-14.5) | 13.3 (9.2-17.8) | <0.001 | |

| WBC max, median (Q1-Q3) x103 | 10.8 (8.1-15) | 10.6 (8-14.6) | 13.3 (9.2-18) | <0.001 | |

| WBC min, median (Q1-Q3) x103 | 10.7 (8-14.7) | 10.5 (7.9-14.3) | 13.1 (8.9-17.8) | <0.001 | |

| Lymphocytes median, (Q1-Q3) x103 | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 1.0 (0.6-1.4) | <0.001 | |

| Lymphocytes max, median (Q1-Q3) x103 | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 1.1 (0.8-1.6) | 1.0 (0.6-1.4) | <0.001 | |

| Lymphocytes min, median (Q1-Q3) x103 | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 1.0 (0.5-1.3) | <0.001 | |

| CRP median, median (Q1-Q3) mg/dL | 10 (4.5-19.4) | 9 (4.1-17.7) | 21.7 (12.1-29.6) | <0.001 | |

| CRP max, median (Q1-Q3) mg/dL | 10.1 (4.5-19.8) | 9.1 (4.1-17.8) | 22.3 (12.1-30.0) | <0.001 | |

| CRP min, median (Q1-Q3) mg/dL | 9.9 (4.4-19.1) | 8.9 (4.0-17.6) | 21.1 (11.8-29.6) | <0.001 | |

| PCT median, median (Q1-Q3) ng/mL | 0.4 (0.2-1.2) | 0.4 (0.2-1.2) | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) | 0.119 | |

| PCT max, median (Q1-Q3) ng/mL | 0.4 (0.2-1.2) | 0.4 (0.2-1.2) | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) | 0.122 | |

| PCT min, median (Q1-Q3) ng/mL | 0.4 (0.2-1.1) | 0.4 (0.2-1.1) | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) | 0.115 | |

| Creatinine median, median (Q1-Q3) mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4-1.0) | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1) | 0.018 | |

| Creatinine max, median (Q1-Q3) mg/dL | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1) | 0.018 | |

| Creatinine min, median (Q1-Q3) mg/dL | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1) | 0.02 | |

| Glucose median, median (Q1-Q3) mg/dL | 125.5 (111-144) | 125 (110.5-143.0) | 131.5 (117-150) | <0.001 | |

| Glucose max, median (Q1-Q3) mg/dL | 147 (127-178) | 146 (126-176) | 160 (134-184) | <0.001 | |

| Glucose min, median (Q1-Q3) mg/dL | 106 (92-123) | 106 (92-122) | 110 (93-128) | 0.059 | |

| Drugs | |||||

| Antibiotic, n (%) | Yes | 1533 (56.5) | 1321 (55) | 212 (67.5) | <0.001 |

| Noradrenaline dose acc, median (Q1-Q3) mg/kg/min | 0 (0.0-1.6) | 0 (0.0-0.7) | 1.4 (0-11.3) | <0.001 | |

| Dobutamine dose acc, median (Q1-Q3) mg/kg/min | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0.176 | |

| Manually recorded clinical parameters | |||||

| Secretion Consistency, n (%) | Thick | 1119 (41.5) | 962 (40.4) | 157 (50) | 0.011 |

| Fluid | 1542 (57.2) | 1387 (58.2) | 155 (49.4) | ||

| Mucus Plug | 27 (1) | 25 (1) | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Others | 9 (0.3) | 9 (0.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Purulent Secretions, n (%) | Yes | 1799 (66.8) | 1518 (63.8) | 281 (89.5) | <0.001 |

| Urinary Output acc, median (Q1-Q3) mL | 1710 (1140-2410) | 1710 (1120-2415) | 1695 (1250-2320) | 0.583 | |

| Nº aspirations, median (Q1-Q3) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-6) | 5 (3-7) | <0.001 | |

| Outcomes | |||||

| ICU crude mortality, n (%) | Yes | 770 (28.4) | 659 (27.5) | 111 (35.4) | 0.004 |

| 24h model | 48h model | 72h model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | XGBoost | XGBoost | XGBoost |

| Accuracy | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| Recall | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.73 |

| AUC | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.75 |

| Confusion matrix | | 52 11 | | 73 407 | |

| 48 15 | | 142 338 | |

| 46 17 | | 146 334 | |

| Majority proportion | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| N variables | 8 | 8 | 12 |

| N features | 11 | 10 | 13 |

| Features | - C-reactive protein (maximum) - C-reactive protein (minimum) - FiO₂ (median) - FiO₂ (minimum) - PEEP (maximum) - Purulent secretion appearance (yes/no) - Respiratory rate (minimum) - SpO₂ (maximum) - SpO₂ (median) - Temperature (maximum) - Urinary output (sum) |

- Antibiotic use (yes/no) - APACHE II (first measurement) - C-Reactive Protein (minimum) - FiO₂ (median) - FiO₂ (minimum) - PEEP (maximum) - PEEP (median) - Purulent secretion appearance (yes/no) - Respiratory Rate (minimum) - Temperature (median) |

- Age - Antibiotic use (yes/no) - Purulent secretion appearance (yes/no) - Days on invasive mechanical ventilation - Urinary output (sum) - FiO₂ (median) - Respiratory rate (median) - Respiratory rate (minimum) - Norepinephrine dose (sum) - C-reactive protein (median) - PEEP (median) - Patient type surgical (yes/no) - SpO₂ (maximum) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).