1. Introduction

Melatonin is a hormone derived from the amino acid tryptophan, via the intermediary neurotransmitter serotonin, and it is best known as a regulator of sleep via its release from the pineal gland at night. However, a little-known fact is that melatonin is also synthesized in the gut by enterochromaffin cells, which are the most abundant enteroendocrine cells in the gut, found primarily in the small intestine [

1,

2]. This was discovered by a team of Russian scientists in 1975 [

3,

4]. It has been claimed that the gut produces 400 times as much melatonin as the pineal gland, but it remains unclear exactly how this source of melatonin affects human health [

5]. Gut microbes regulate the synthesis and metabolism of melatonin in the gut, and gut dysbiosis may disrupt melatonin homeostasis, leading to neurological disease [

6]. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced by the gut microbes stimulate the synthesis of serotonin from tryptophan and its release from enterochromaffin cells, potentially enhancing melatonin production [

7]. Gut motility is regulated through the effects of these microbiome metabolites on serotonin synthesis by enterochromaffin cells [

8].

Melatonin synthesis takes place primarily in the mitochondria. There, it performs several critical functions, such as scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS), helping to maintain the mitochondrial membrane potential, supporting ATP synthesis by the ATPase pumps, and enhancing the efficiency of the electron transport chain [

9,

10]. It also promotes mitochondrial fusion over mitochondrial fission and facilitates intercellular mitochondrial transfer via tunneling nanotubes [

11]. Exactly how it achieves all these remarkable feats is not entirely understood.

Our team has been focusing on the issue of deuterium homeostasis in the body, particularly with respect to deuterium’s damaging effects on mitochondrial ATPase pumps, and we have published several papers related to different aspects of this topic [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Deuterium is a heavy isotope of protium, containing a neutron in addition to a proton. This makes it twice as heavy, and significantly alters its biophysical and biochemical properties, compared to protium. The ATPase pumps in the mitochondria rely on proton motive force as the source of energy for ATP production. Our investigations into metabolism have led us to believe that a crucial aspect of mitochondrial health is the maintenance of very low levels of deuterium in the mitochondria, a feat that is achieved through the activities of many specialized enzymes operating throughout the cell.

Deuterium is a natural nonradioactive element, present in seawater at 155 parts per million. It randomly substitutes for protium in all molecules that contain hydrogen. Certain enzymes, especially flavoproteins and isomerases, play a crucial role in scrubbing deuterium from biologically important molecules and in maintaining deuterium depleted (deupleted) metabolic water in the mitochondria [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Flavoproteins are an important class of enzymes that use flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as a cofactor, and they typically have a high deuterium kinetic isotope effect (KIE), meaning that the reaction is much slower if they must extract a deuteron rather than a proton from the substrate. The reaction involves proton tunneling, which deuterons are much less effective at due to their bulkier size [

17]. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes are a powerful class of flavoproteins that are highly expressed in the liver, mainly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), but also in the mitochondria, and we propose that they offer critical support for reducing the deuterium burden. As we shall see, we propose here that CYP2C19, expressed in cells lining the gut wall, helps to maintain low deuterium in the mitochondria via its metabolism of melatonin.

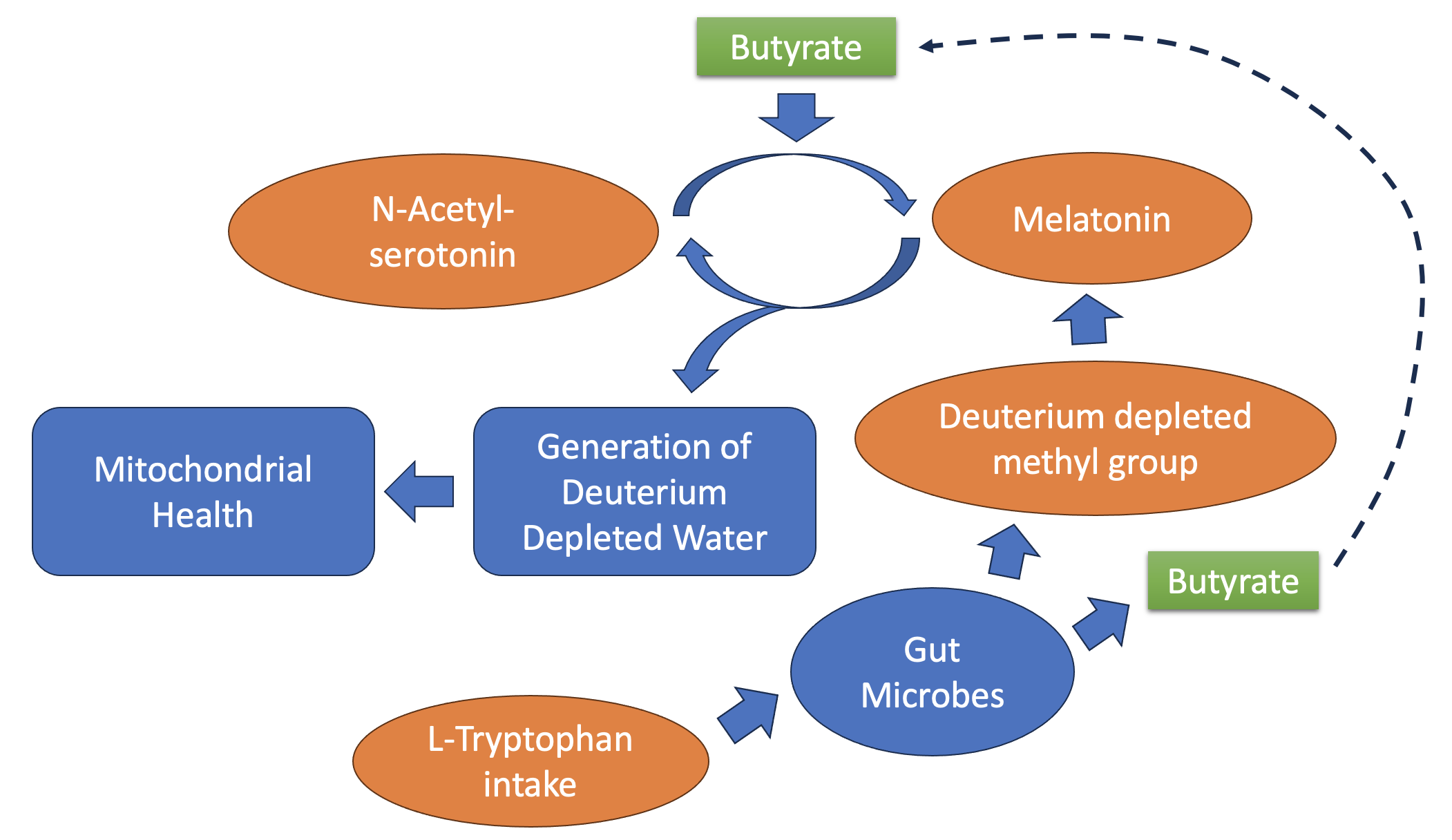

Our investigations have led us to conclude that activities in the ER support a reduction in the deuterium burden there, and that deupleted protons can be transferred from the ER to the mitochondria through a mechanism that involves the synthesis of an intermediary, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). In the mitochondria, H2O2 is further reduced to deupleted water via glutathione peroxidase. In this paper, we propose that an important aspect of melatonin’s role in the gut is supporting the supply of deupleted water to the mitochondria of enterocytes and colonocytes. This is achieved through repeated recycling between melatonin and its precursor, N-acetylserotonin. We identify a crucial role for the gut microbes in supplying a deupleted methyl group to convert N-acetylserotonin to melatonin, which is then fully metabolized in the reverse step catalyzed by CYP2C19 to produce four molecules of deupleted water.

2. The Co-Evolutionary Origin of the Mitochondrion and the Role of Melatonin Synthesis

The indoleamine melatonin is probably the master redox regulator molecule of all antioxidant compounds found in nature. Being amphiphilic in nature, melatonin holds a central position in directing the antioxidant defenses of both a) lipophilic antioxidant compounds such as vitamin E, which is embedded in cellular phospholipid membranes and b) hydrophilic compounds such as vitamin C and glutathione (GSH), which are localized to the aqueous environments of the cellular cytosol and organelles [

18]. Current research advocates that this design is not by accident, as melatonin provided the first innate immune defense through its potent antioxidant capabilities, arguably essential for current life on earth to exist.

Melatonin is an ancient molecule initially synthesized millions or even billions of years ago [

18] to sustain the homeostasis of early lifeforms. Mitochondria are believed to be descendants of purple non-sulfur bacteria (

Rhodospirillum rubrum), and chloroplasts are believed to have evolved from cyanobacteria. Both

R. rubrum and the cyanobacteria synthesize melatonin. To this day, mitochondria and chloroplasts are the primary site of melatonin synthesis in the cells that contain them. The photosynthetic gram negative bacterium

R. rubrum is most probably the bacterium that later, through endosymbiosis with proto-eukaryotes, interacted with a proto-mitochondrion to give rise to the central respiratory organelle of the cell, the mitochondrion, that we find in humans and other mammals today [

18,

19]. However, even the red blood cells that do not contain mitochondria are capable of synthesizing melatonin, indicating also the cytosolic capacity of cells to produce this miraculous antioxidant [

20].

R. rubrum synthesizes melatonin in a circadian rhythm [

21] and this is probably one of the most ancient forms of antioxidant defense science has discovered. The genetic transformation of mitochondria through evolutionarily sustained bacterial endosymbiosis is now indisputably supported [

22]. Likewise, and in parallel, plant chloroplasts have evolved though endosymbiosis with cyanobacteria. Plant chloroplasts synthesize melatonin, but they are also fed through their roots by melatonin synthesized by bacteria in the soil [

18]. It is therefore the case that plants use higher amounts of melatonin than what they can synthesize on their own.

The most recent theory supports the idea that mitochondria initially evolved in anaerobic conditions in close interaction and dependence with methanogenic alpha-proteobacteria that used hydrogen (H

2) as a reducing agent. The H

2 dependence and exchange gave rise to the facilitation of ancestral organisms on oxygen dependence and therefore eukaryogenesis that resulted in the evolution and formation of mitochondria [

23]. This is probably why the facultative anaerobe

R. rubrum, which has the capacity to utilize oxygen via the dimethyl sulfoxide route, provided the most likely evolutionary endosymbiosis solution to form the mitochondrion [

23,

24].

Melatonin, apart from its pineal cell synthesis and secretion in the brain, is also probably synthesized by nearly all human cells, mainly in the mitochondrial matrix, with a back-and-forth metabolism between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes, and this practice possibly holds for all vertebrate cells. The essential amino acid tryptophan is the precursor molecule to melatonin, through an intermediary, serotonin [

25,

26]. Melatonin is formed in a two-step process that adds first an acetyl group and then a methyl group to serotonin. Remarkably, oocyte mitochondria readily produce melatonin. Thereon, all descendent mitochondria of cells continue to produce melatonin to provide the master antioxidant defense and aid in mitochondrial energy (ATP) production.

Furthermore, there is substantial genetic linkage on melatonin metabolism between bacteria and eukaryotes. Primarily in mammals, melatonin is synthesized from acetyl Coenzyme A (Acetyl CoA), which is used as a substrate by serotonin N-acetyl transferase (SNAT). Homologous genes to SNAT are found in archaeobacteria and are thought to have been horizontally transferred and integrated into the eukaryotic and then mammalian genomes by the endosymbiotic bacteria that gave rise to both mitochondria and chloroplasts [

18,

27]. SNAT is located in the matrix and inter-membrane space of mitochondria in all cell types, indicating that, apart from the pineal gland, there is substantial extra-pineal synthesis of melatonin in mitochondria of various mammalian cell types and tissues due to the horizontal transfer of genes from ancestral bacterial endosymbiosis [

18,

28,

29]. Melatonin synthesis has thus provided the necessary essential molecule, melatonin, for life to sustain oxygen metabolism and combat the oxidative stress inevitably generated by respiration almost throughout the existence of life on earth.

3. S-Adenosylmethionine, Methylation Pathways, and Short Chain Fatty Acids

Methylation pathways, also known as one-carbon metabolism, play an important role in signaling mechanisms, with methylation of proteins (especially histones), RNA and DNA controlling metabolic flow in many ways. S-adenosylmethionine is considered to be the “universal methyl donor,” as it is typically the source of methyl groups that are attached to other molecules [

30]. Importantly, S-adenosylmethionine is also the source of the methyl group that is added to N-acetyl serotonin to synthesize melatonin.

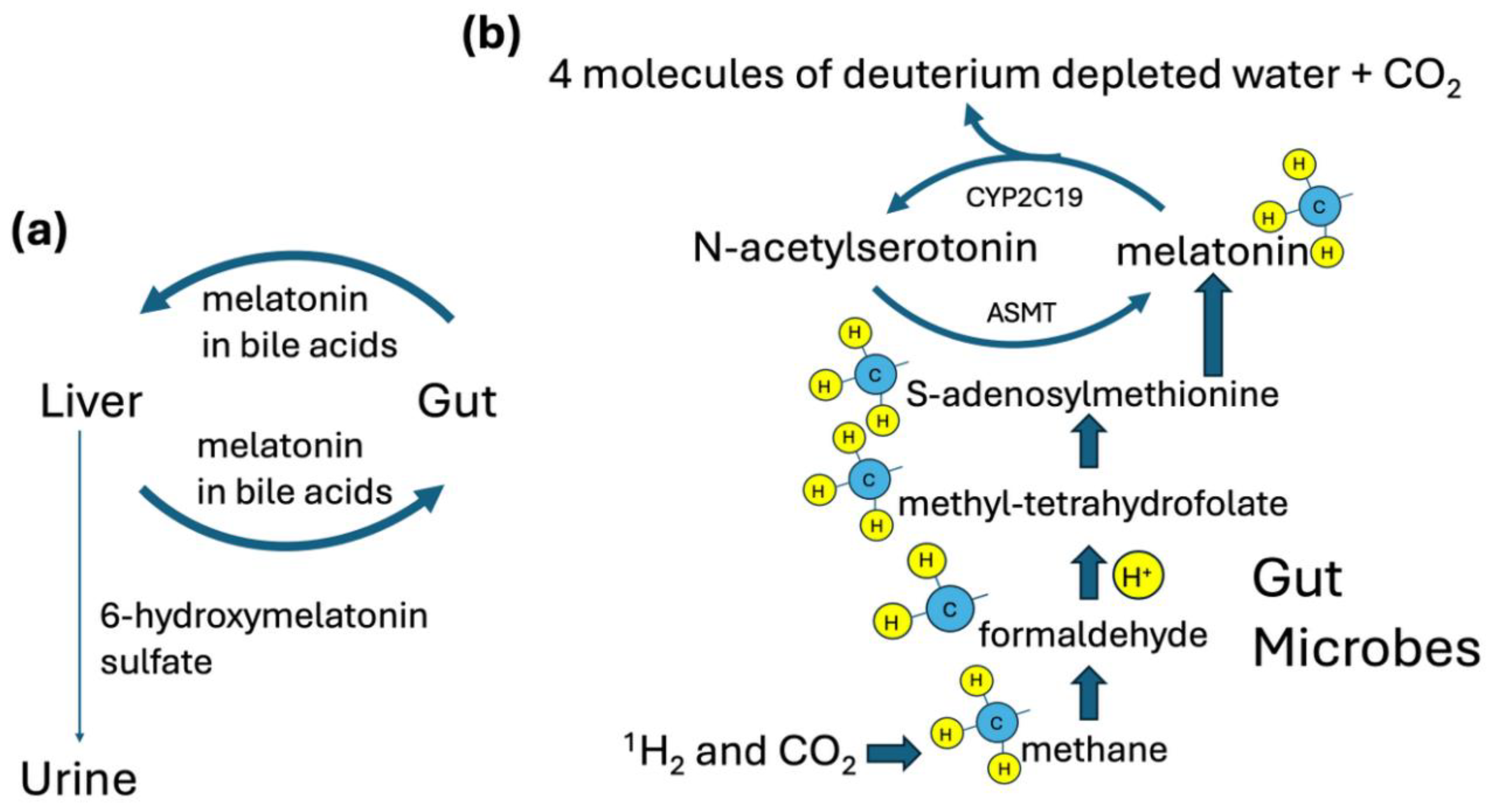

It is highly likely that the methyl group bound to the sulfur atom in methionine is extremely deupleted, unless it is a synthetic form of methionine as found in supplements. The process of methionine synthesis in the gut traces back to formaldehyde, which, in turn, traces back to hydrogen gas produced by the gut microbes [

12]. The fermentation process in the gut extracts protons from small organic molecules to produce H

2 gas, which is 80% depleted in deuterium [

31]. H

2 is then used as a reducing agent by methanogenic bacteria to produce methane gas from carbon dioxide. The methane gas is then converted to methanol followed by formaldehyde (HCHO) through further microbial enzymatic action. Formaldehyde reacts both enzymatically and nonenzymatically with tetrahydrofolate to produce methylene tetrahydrofolate [

32,

33,

34]. A final step, catalyzed by the enzyme methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), yields methyltetrahydrofolate, which is the source of the methyl group that is transferred to homocysteine to produce methionine [

35]. MTHFR is a flavoprotein with a deuterium KIE of 2.9 [

36].

Using similar arguments, the short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), acetate, propionate and butyrate, can also be expected to be deupleted. Acetogenic bacteria use H

2 gas to reduce carbon dioxide to acetate, and acetate is a precursor to propionate and butyrate. SCFAs, especially butyrate, are essential nutrients produced by the gut microbes for the host [

12].

4. Butyrate is the Leading Short Chain Fatty Acid Offering Protection to Human Health

Current scientific evidence strongly suggests that human health heavily depends on the production of SCFAs by gut microbiota, mainly produced in the colon. The numerous health benefits, including cardiovascular, immunomodulatory and anticancer, are thoroughly described in a study by RG Xiong [

37]. SCFAs are the main source of energy for colonocytes and enteroendocrine cells. SCFAs, especially butyrate, activate hormone release from enteroendocrine cells, and they have important roles in energy homeostasis and satiety. They also suppress inflammation in the gut and help maintain the integrity of the gut wall [

38].

SCFAs and their metabolites are the metabolic products of microbiome fermentation (including the vagina and skin) and amongst them, propionate, butyrate and acetate constitute 90% of SCFAs produced by the microbiome [

39]. However, butyrate seems to be the most important and well-studied SCFA for its impact on human health. Butyrate is directly implicated in the preservation of human gastrointestinal (GI) tract homeostasis and protection from various liver and metabolic diseases, and its benefits extend to important anti-inflammatory and anticancer modes of action throughout the human organism as well [

40,

41,

42]. With respect to its anticancer effects, butyrate works as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, taking its place among a class of molecules that have gained much attention lately as promising anticancer agents [

43]. Butyrate has been shown to stimulate increased synthesis of serotonin by enterochromaffin cells in the gut [

7].

Specific studies on germ-free (GF) animals (animals that lack an intestinal microbiome), pinpoint more conclusively the contribution of butyrate activities on human health. As might be expected, GF animals are severely depleted in butyrate production in their gut [

44]. In this regard, the colonocytes isolated from GF animals appear to suffer from a) mitochondrial dysfunction (having severely altered mitochondrial respiration), and b) impairment in autophagy. A lack of butyrate seems to be the sole contributor to these disease producing processes [

44].

Ob/ob mice are a mouse model of obesity and type II diabetes. They have a defect in leptin synthesis which causes them to overeat. A study published in 2016 showed that a characteristic feature of these mice is reduced levels of butyrate-producing bacteria in the gut. This was associated with an alteration in the bile acid profile which, through signalling mechanisms, induced increased fatty deposits in the liver [

45].

As GF animals provide the optimal model to investigate butyrate’s health activity, the study of AD Vincent et al. is most revealing [

38]. These researchers investigated the impact of butyrate on colon motility by determining the levels of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, also known as serotonin) which is synthesized from the amino-acid tryptophan. The production of serotonin and release in the gut of GF animals has been proven to enhance colonic motility. In these GF animals, when the microbiome was reconstituted, a parallel elevated level of serotonin in the blood, apart from that in the colon, was also recorded [

46].

Returning to the AD Vincent et al. study, butyrate was found to be the sole driver of colonic motility, directly elevating the level of colonic serotonin. Moreover, in the same study, the researchers used genetically ablated animals that could not express tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (TPH-1), the rate limiting enzyme for the synthesis of serotonin from tryptophan. By using these genetically ablated animals, the researchers were able to conclusively determine that it was the butyrate levels that directly increased serotonin and serotonin signalling mechanisms, which improved lower gut motility. This complements other studies, where it has been shown that butyrate controls serotonin levels by decreasing the activity of the serotonin transporter (SERT), thus limiting its clearance [

47]. It is therefore remarkable how butyrate, a metabolic product of the gut microbiome, controls serotonin synthesis and thus indirectly controls the synthesis of melatonin in the gut [

41].

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is an important appetite-suppressing hormone released from intestinal L cells in the gut. It is well established that sodium butyrate promotes GLP-1 secretion from intestinal L cells, acting in part through its effects as an HDAC inhibitor [

48]. Treatment of db/db mice with either sodium butyrate or

Clostridium butyricum, a microbe that produces butyrate, resulted in improved markers for liver inflammation and reduced lipid accumulation, along with upregulation of serum GLP-1 levels and improved tight junction function in the gut [

49]. A comprehensive review paper with over 100 references concluded that the evidence is very strong that butyrate is therapeutic in treating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [

50].

Furthermore, currently, butyrate is considered as an essential molecule for speeding up post-operative surgical healing, and it works as an anticancer agent in colon cancer cases, promoting the growth of non-malignant colonocytes [

51].

5. Does Hydrogen Peroxide Act as a Carrier Molecule for Deupleted Water in the Cell?

H

2O

2 is a potent signaling molecule that is a crucial player in many redox reactions. H

2O

2 is water soluble, but it can also cross lipid membranes, facilitated by aquaporins. A significant amount of H

2O

2 is synthesized in the ER, particularly through the activity of protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and ER oxidoreductin 1 (ERO1), which are involved in the formation of disulfide bonds in proteins to facilitate their folding [

52]. Aquaporin 11 in the ER membrane promotes the export of H

2O

2 into the cytoplasm [

53]. Elevated levels of H

2O

2 can be toxic to the cell. ERO1 is a flavoprotein localized to the ER membrane [

54], and, as such, it has a high deuterium KIE, which will lead to the synthesis of deupleted H

2O

2.

When the levels of H

2O

2 rise in the cytoplasm, mitochondria can play a protective role by importing H

2O

2 and reducing each molecule of H

2O

2 to two molecules of water through glutathione peroxidase [

55]. Mitochondria thus serve an important role in protecting the cell from damage due to excess H

2O

2 in the cytoplasm. Notably, H

2O

2 produced in the ER can become water molecules inside the mitochondria in this way. Both the protons sourced from the ER and the protons sourced from the mitochondria can be expected to be deupleted. Glutathione receives its protons from NADPH, synthesized in the mitochondria from mitochondrial NADH, which carries a highly deupleted proton [

12].

It is possible that the isomerase peptidyl prolyl isomerase (PPIase) plays a role in sequestering deuterium within proline residues in proteins such as collagen, in the ER. Collagen is the most common protein in the body, making up nearly one third of the body’s total protein mass. It is highly enriched in proline, and it appears plausible that proline can trap deuterium on its alpha-carbon atom [

56]. An experiment on fully deuterated prolyl residues in a peptide showed that the reaction catalyzed by PPIase has an unusual

inverse deuterium KIE: the isomerization rate is increased when proline is deuterated. The authors stated that deuterium facilitates the twisted-amide conformation in the prolyl amide bond, increasing the rate of isomerization [

57]. It is conceivable that a consequence of prolyl isomerization in the ER is to populate the alpha carbon of the proline ring with deuterium, thus decreasing the amount of deuterium in the solvent water. If this is true, it would help explain the enrichment of deuterium in bone that was found in a study on seals [

58]. Bone contains a large amount of collagen, and deuterium doping in bones strengthens them, a useful feature for seals to support their deep dives. Their bones were found experimentally to contain 300 ppm deuterium, twice the normal concentration [

58]. A study on proline has revealed that the alpha carbon of proline, once deuterated, is very reluctant to give up its deuterium atom, even when the amino acid is immersed in a highly acidic solvent [

59].

It has been shown experimentally that the two isomerases that are active in the ER, PPIase and PDI, collaborate to accelerate the rate of protein folding, i.e., PPIase improves the efficiency of PDI [

60]. We hypothesize that PPIase removes deuterium from the water, whereas PDI facilitates the synthesis of deupleted H

2O

2, which is then delivered to the mitochondria and converted there to two molecules of deuterium depleted water (DDW). Thus, PPIase further reduces the likelihood that deuterium will be incorporated into H

2O

2.

6. Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in the Endoplasmic Reticulum in the Gut and Liver

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes are a superfamily of enzymes that metabolize many substrates using NAD(P)H as a reducing agent. Their reactions typically involve extracting a proton from the substrate, splitting the oxygen molecule, and replacing -H with -OH in the substrate. Water is very common as a product of the reaction (through reduction of the other oxygen atom in molecular oxygen), and this water molecule will be deupleted because CYP enzymes are flavoproteins, which use proton tunneling to facilitate proton transport [

17]. Deuterons pass through water channels 20 times less efficiently than protons [

61]. The majority of the CYP enzymes in human cells localize to the ER membrane, where they are responsible for metabolizing many pharmaceutical drugs, as well as endogenous molecules including steroids (e.g., cholesterol and vitamin D), fatty acids, and vitamin A [

62]. Metabolism by CYP enzymes typically converts the substrate into a more water-soluble molecule that can then be excreted through the kidneys. In humans, almost 80% of oxidative metabolism and metabolism of half of the common drugs are attributed to CYP enzymes [

63].

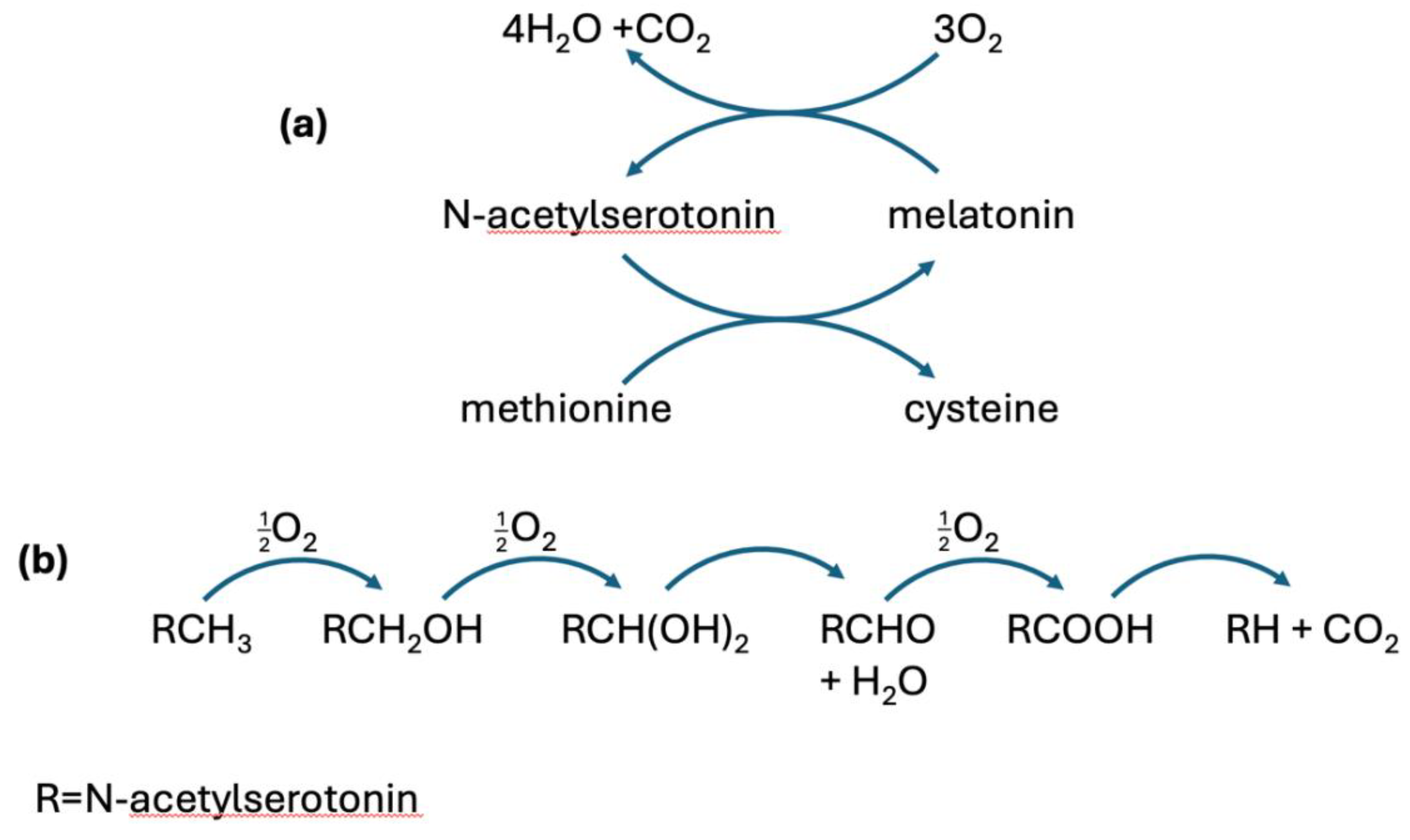

CYP enzymes also metabolize melatonin. CYP1A2 and CYP1B1 in the liver convert melatonin to 6-hydroxy-melatonin, which is then sulfated and excreted in the urine as the principal metabolite of melatonin [

64]. However, melatonin is recycled multiple times from the gut to the liver and back via the bile acids, and there are CYP enzymes in the gut lining, namely CYP2C19, that metabolize melatonin back to N-acetylserotonin by removing the methyl group attached to the oxygen atom. Thus, a single molecule of melatonin can go through many cycles of conversion back and forth between N-acetylserotonin and melatonin in the gut. With each cycle, the methyl group, sourced from methionine, is completely metabolized to carbon dioxide and water, producing four molecules of deupleted water each time.

Figure 1 schematizes the reaction catalyzed by CYP2C19 that metabolizes the methyl group in melatonin.

Ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes demethylate the cytosines in DNA through a similar process that involves repeated hydroxylation of the methyl group to convert it first to a hydroxymethyl, then to a formyl, and finally to a carboxyl group, before release of CO

2 [

65]. With each step, glutamate is converted to succinate, which receives a deupleted proton from the methyl group. Succinate feeds protons to the intermembrane space of the mitochondria via succinate dehydrogenase, so it is very important for its protons to be deupleted.

These observations lead us to propose that melatonin may play an essential role in the gut wall in supplying deupleted water to the ER of human cells lining the gut. Läpple et al. wrote in the abstract of their paper: “Although, overall, the expression and activity of CYP2C enzymes is lower in the gut than in the liver, the surface area of the proximal small intestine is large and intestinal CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 may well contribute to the first-pass metabolism of their substrate drugs” [

66]. We argue here that CYP2C19 also plays an essential role in synthesizing deupleted water by metabolizing methyl groups attached to melatonin, that were derived from methionine, the universal methyl donor. These methyl groups can be traced back to hydrogen gas produced by the gut microbes, which is 80% depleted in deuterium, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

7. Considerations around Melatonin and Tryptophan Supplementation

Consumption of melatonin as a dietary supplement has increased dramatically over the past two decades in the United States, and that trend is expected to continue into the future [

67,

68]. Bulk production of melatonin for the retail market is not without its significant limitations and drawbacks, though.

Arnao et.al. have written an excellent overview of the health benefits and manufacturing challenges of commercially produced melatonin. The production challenges are briefly described here. Virtually all commercially available melatonin on the market at this time is manufactured through chemical synthesis. While there are several different chemical pathways that can be utilized, each one produces multiple reaction byproducts that are toxic to varying degrees. This has made product safety and purity a significant concern and has also encouraged the identification of an organic source of melatonin that can be extracted and purified for retail sale [

69].

It is now well-established that melatonin is endogenously produced not only by all animals, but also by several species of bacteria, fungi, and plants as well, the latter often referred to as “phytomelatonin” to designate the plant-based source. Unfortunately, the quantity of melatonin that can be extracted per unit volume of plant material is miniscule, requiring inordinately large amounts of biomass to obtain even a single typical standard supplemental dose of 3mg. To sidestep this problem, a few pharmaceutical manufacturers have utilized genetically modified bacteria to dramatically increase microbial melatonin production. While these efforts have been relatively successful, it is generally recognized that the primary market for supplemental melatonin—health-conscious consumers—would likely be reticent to purchase a product derived from genetically modified organisms [

69].

Beyond the issue of toxic byproducts, we have described in this paper another reason to favor organically/endogenously produced melatonin over that produced via chemical synthesis. Namely, there is a confluence of factors including enzyme kinetics, deupleted methyl groups, and others that strongly favor production and recycling of endogenous melatonin that is severely deupleted and thus contributing to overall organismal deuterium regulation and cellular DDW production.

Given our contention that there is a dramatically larger amount of melatonin that is being de novo synthesized from dietary tryptophan as well as recycled via interconversion to N-acetylserotonin, we believe it is worth revisiting the use of tryptophan supplementation. This feeds into the chain of events that should ultimately expand the pool of endogenous, deupleted melatonin, ultimately enhancing all the health benefits already described for that molecule.

There is substantial evidence that intake of tryptophan does in fact have a significant role in determining endogenous melatonin production. Zimmermann et. al. (1993) noted that dietary tryptophan restriction for less than 24 hours resulted in reduction in baseline serum tryptophan by over 80%, and a concurrent blunting of melatonin production took place as well [

70].

Just as depletion of tryptophan reduces melatonin production, Estaban et. al. demonstrated in 2004, in a rat model, that supplementation with tryptophan increases both serotonin and melatonin production with concomitant enhancement of innate immunity. This confirmed a prior study, again in a rat model, showing that loading with tryptophan increases serum melatonin 4-fold. This was true in both pineal-gland-intact and pinealectomized rats, demonstrating that the increased melatonin was not of pineal origin, but likely gastrointestinal [

71].

There are now thousands of articles published on supplemental melatonin, most describing significant health benefits that cover an astoundingly wide range of pathologies [

72]. Supplemental tryptophan, too, has been shown to have potentially significant benefit in the treatment of autism, cardiovascular disease, cognitive function, chronic kidney disease, depression, inflammatory bowel disease, microbial infections, and others [

73]. Given our detailed explanation of how endogenous melatonin production contributes to systemic deuterium regulation—which both synergizes with and adds to the health benefits previously established for supplemental melatonin—we suspect that studies comparing the benefits of supplemental melatonin vs tryptophan loading will find the latter to be equivalent to or perhaps even superior to the former therapeutically.

8. Melatonin’s Role in Taming the Severity of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Spike Protein-Related Pathology

Melatonin is a powerful neuroprotective, immunomodulatory and antioxidant hormone secreted mainly from the pineal gland in the brain, but also from other tissues throughout the body including the retina, the gastrointestinal tract, the bone marrow cells and the lymphocytes. A detailed analysis of its pharmacological and therapeutic properties is described in the S. Torjiman study [

74]. In relation to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection and its spike protein-related pathology, the implications of melatonin deficiency seem to be severe.

The initial and main pathway by which SARS-CoV-2 infects human cells is through the interaction of its spike protein receptor-binding domain (RBD) with angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE 2) [

75]. The subsequent proteolytic activation, endocytosis and entry of the virus into the cells and the subsequent viral replication initiates the pathological consequences of COVID-19, as well as long COVID, which persists after the acute phase and involves multiple organs [

76]. According to a study by E. Cecon et al. [

77], melatonin, by binding to ACE2 allosterically, meaning to another domain of the ACE2-RBD/spike protein interface, prevents SARS-CoV-2 virus entry into endothelial cells. The melatonin allosteric interaction with ACE2, although at a different domain than the active site for the enzyme, produces a conformational change to the ACE2 molecule that negatively alters its affinity to the spike protein RBD. The researchers who conducted this study, by using rat models, have also shown that melatonin treatment decreased virus load in the brain and diminished brain inflammation otherwise caused by SARS CoV-2 infection.

Moreover, these researchers observed that melatonin protected the cerebral small vessels from damage upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. They have also found that the main pathological pathway that was inhibited by melatonin treatment, and subsequently saved the cerebral vessels from damage, was the inhibition of NF-κB activation. This was achieved by lowering the expression of NF-κΒ gene expression by melatonin[

77]. Earlier studies have shown that melatonin, at micromolar concentrations, prevents the activation of the NF-κB pathway by inhibiting its translocation to the nucleus [

78]. This has a direct negative impact on the transcription of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and low iNOS expression results in decreased production of nitric oxide (NO).

8.1. Taming the Cytokine Storm

For the human organism to achieve micromolar concentrations of melatonin and avoid tissue injury, it will require a local (extra-pineal) production of melatonin by activated immune competent cells. Melatonin, apart from being a strong positive immunomodulator of a lymphocyte-activated immune system, is also a potent activator of the innate immune system, which involves monocytes, macrophages and natural killer cells, amongst many other immune cells [

79]. Moreover, this potent neurohormone readjusts the explosion of cytokines seen in SARS-CoV-2 infection and can have profound therapeutic benefits as a treatment during COVID-19 [

80].

Experimental studies on activated lymphocytes show that these cells are equipped with the necessary metabolic enzymes and are able to produce up to five times more than the nocturnal concentration of melatonin encountered in human serum under normal physiologic conditions [

80,

81]. The expression of melatonin in activated lymphocytes is linked directly to the enhancement of interleukin-2 (IL-2) production. Moreover, a deficiency in the release of melatonin by lymphocytes reduces the expression of the IL-2 receptor, a condition that is reversed by the addition of exogenous melatonin [

82].

Melatonin is a strong positive modulator of a T helper 1 (Th1) over a Th2 type immune response in the human organism. On the other hand, the strong protagonists of the innate immune response, the monocytes, when activated by melatonin, produce increased amounts of IL-1 and IL-12 cytokines [

83]. This constitutes melatonin as an important positive regulator of the IFN-γ and Th1 responses, and a strong counteractor of a Th2 response. This is an important immune signaling modulation since IL-12 drives the CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes to produce the immunoregulatory cytokine, IL-10 [

84].The production of IL-10 is a strong anti-inflammatory signal to compromise and to prevent excessive tissue damage upon infection and production of autoimmune events. Notably, apart from many immune cells of the adaptive response, IL-10 is also produced by resident macrophages, microglia and cardiac macrophages to protect from an exacerbated inflammatory response. Therefore, the presence of adequate amounts of melatonin can be regarded as an important homeostatic immune equilibrator during the excessive cytokine expansion in response to SARS CoV-2 infection.

Macrophages are believed to be the major cell type responsible for the cytokine storms associated with severe COVID-19 [

85]. Macrophages normally convert from a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype as an infection reaches resolution. However, a study by Salina et al. showed that SARS-CoV-2 is able to lock macrophages into an M1 state, causing excessive tissue damage due to a cytokine storm [

86]. Remarkably, melatonin promotes the conversion of macrophages from an M1 to an M2 state [

87]. Furthermore, M2 macrophages, but not M1 macrophages, highly express CYP2C19, the enzyme that fully metabolizes the methyl group in melatonin [

88].

8.2. Protection from Coagulopathy

A study by A. Hosseinzadeh et al. strengthens the arguments for using melatonin as a prophylactic agent against coagulopathy and intense platelet activation that cause severe and life-endangering pathological outcomes during COVID-19 [

80]. In a randomized clinical trial, the administration of 10 mg of melatonin per day as an adjuvant in hospitalised severe COVID-19 patients helped to lower the occurrence of thrombosis and sepsis incidents. This resulted in reduced patient mortality compared to the patients not receiving melatonin [

82].

Complementarily, in a previous rat-injury model investigation, where the animals were subjected to burns, 10 mg of melatonin intraperitoneal injection hours after the injury reduced fibrin degradation products (FDP) and led to increased glutathione (GSH) concentrations. The increased GSH matched the lowering of lipid peroxidation in the animals, causing the authors to suggest a potent antioxidant role for melatonin, which reduced injury complication events [

89].

D-Dimer is an FDP that is frequently used to diagnose coagulation incidents. Especially during COVID-19 and long after the infection, elevated levels of D-Dimer persist, indicating increased severity of illness and organ injuries [

90]. In a clinical study involving healthy men who were subjected to psychosocial stress, the oral use of 3 mg of melatonin one hour before the stress event attenuated the rise of D-Dimers and limited the pro-coagulant stress-induced events. Its action suggested that it could play a potent role against atherosclerotic thrombosis associated with neural stress [

91].

Regarding spike protein-related pathologies that also associate with mRNA COVID-19 vaccination, the study of MTJ Halma et al. [

92] presents in detail how vaccine injuries due to the spike protein involve neural, cardiac and other organ pathologic events. Central to the pathologic events is the intense activation of NF-κB and p38 MAPK that produce, amongst other pathologic sequelae, neurodegeneration [

93,

94].

Spike protein-related pathology involves the activation of Toll like receptors (TLR) 2 and 4. Moreover, the mRNA vaccine-produced spike protein is distributed via exosomes, intracellular networks and direct cell fusion in multiple organs, including the brain [

95,

96]. A spike protein-related pathological outcome is long COVID, which comprises a range of disease conditions associated with the long-term expression of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. In the state-of-the-art review by DP Cardineli et al., it is described that melatonin, through its antioxidant effects, can reduce the NF-κB-related pro-inflammatory response and offer a neuroprotective shield against synaptic impairment and neuronal degeneration that leads to cognitive impairment [

97].

8.3. Protection from Neurodegeneration

A fine study on melatonin and glutathione regulation elucidates how melatonin can work to offer brain protection against neurodegeneration. The authors, RJ Reiter et al., formulate the antioxidant activity of melatonin to be the major protagonist against disease. Melatonin, apart from being a direct stimulant of glutathione, upregulates the antioxidant enzymes glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase. By cooperating with other compounds against oxidative stress and reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS), it also offers protection against the dangerous metabolites generated from nitric oxide (NO) [

98]. Similar to its effects on macrophages, melatonin promotes the conversion of M1 microglia in the brain to an M2 phenotype [

99].

The upregulation of glutathione is especially important, as it has been described in detail to be a therapeutic pathway to control severe inflammation manifested in COVID-19 [

100]. Moreover, as already described, melatonin downregulates iNOS production as well as the NF-κB response [

77]. What should be added, however, is that the potent NF-κB compilation of transcription factors has two arms acting during inflammation, a pro-oxidant and an antioxidant arm that target genes during the stimulation by ROS [

101].

Therefore, melatonin, by upregulating glutathione and downregulating the expression of iNOS, seems to mostly favour the antioxidant arm of NF-κB, providing extra antioxidant facilitation during inflammation by NF-κB itself [

101]. The antioxidant effect of melatonin via indirect control of NF-κB offers further antioxidant protection by the upregulation of many genes, including heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) and catalase, amongst many others. In simple terms, melatonin can work against spike protein-related pathology in multiple ways, from being a strong antioxidant to being a negative promoter of harmful cytokines such as IL-6 (NF-κB signaling pathway), which is a protagonist in acute myocarditis pathology [

102] which frequently develops after mRNA vaccination [

103,

104]. Similar NF-κB / IL-6 related pathology is involved in neurodegeneration responsible for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) [

105].

Melatonin also upregulates thioredoxin 1 (Trx1). Thioredoxins contain cysteine active sites that react with ROS and protect from the oxidation of other proteins, limiting oxidative stress and thus combating inflammatory disease [

106]. On one hand, melatonin upregulates the Trx1 pathway [

107], and on the other hand, the activation of NF-kB is required for the activation of Trx1 and superoxide dismutase, another important antioxidant enzyme [

108]. The SARS CoV-2 spike protein causes a rise in TNF-α as part of the inflammatory response, which is responsible for cognitive dysfunction. TNF-α is responsible for the related pathologies seen in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Therefore, melatonin, when present in a TNF-α rich-inflammatory environment [

108], can be an important antioxidant, limiting inflammation in the brain through the modulation of NF-kB to promote the Trx1 antioxidant pathway [

101].

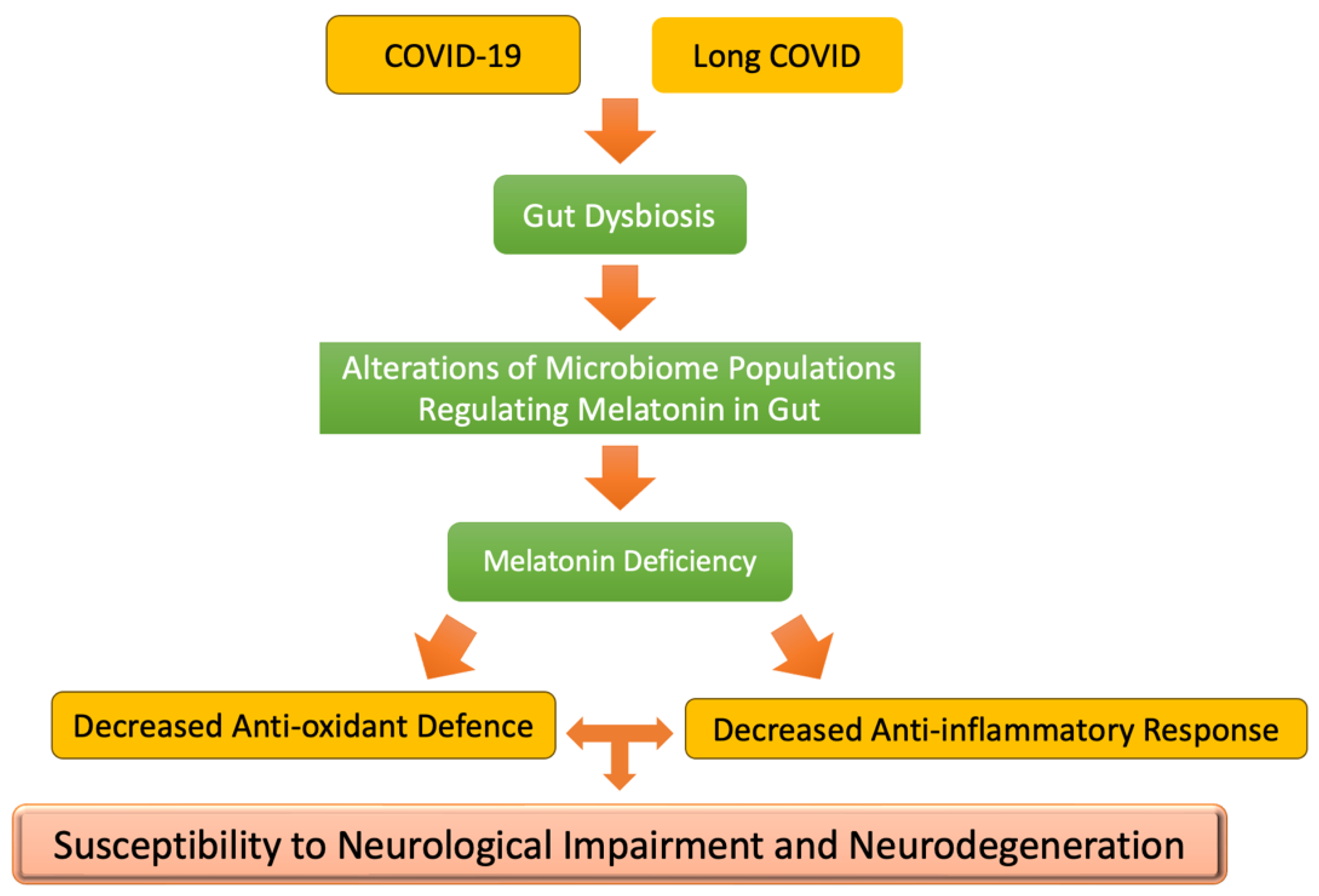

As illustrated in

Figure 3, COVID-19 infection causes a profound gut microbiome alteration and subsequent dysbiosis with direct consequences to disease severity (for review, see [

109]). The decline of beneficial microbial populations in the patient’s microbiome during COVID-19 and the rise of pathogenic populations may have a direct impact on the melatonin produced in the gut [

110]. Hence, we observe increased apoptosis of intestinal enterocytes (including colonocytes) during and after COVID-19. Equally, it has been suggested that mRNA COVID-19 vaccination can cause alterations and dysbiosis in the gut microbiome that could also lead to deficiency in melatonin production [

111], although this is still arguable [

112]. Nevertheless, the direct impact of the loss of apoptosis inhibition by melatonin may have disastrous consequences for susceptibility to neurodegeneration in long COVID [

113]. Supplementary studies are needed to identify the generated pathology—microbiome-related conditions with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Related and significant studies have identified a loss of butyrate-producing bacteria in long COVID that can be the outcome of spike protein toxicity [

114]. An activation of the kynurenine metabolic pathway that would lead to a decline in melatonin production has been traced in long COVID, which is linked to neurological (cognitive) impairment in these patients [

115].

9. Conclusions

Melatonin, an ancient natural hormone that first appeared in one-celled animals millions or even billions of years ago, plays a fundamental role in nearly all lifeforms. In this paper, we develop a novel perspective on melatonin that relates to deuterium homeostasis. While melatonin is best known for its role in regulating circadian rhythms via its release from the pineal gland, the gut produces 400 times as much melatonin as the pineal gland. This melatonin is recycled between the gut and the liver multiple times before finally exiting via the blood stream and the kidneys as an oxidized and sulfated metabolite. During this recycling, melatonin is repeatedly converted back to N-acetylserotonin and regenerated, each time consuming a methyl group drawn from S-adenosylmethionine.

The synthesis and metabolism of melatonin in the gut is important for human health. Through methylation pathways, starting from S-adenosylmethionine, and via the metabolism of melatonin, essential deuterium depleted water for healthy mitochondrial functioning to generate ATP is co-produced. Gut dysbiosis results in a deficiency of microbial populations regulating melatonin homeostasis, carried out in part through the production of SCFAs, especially butyrate. Butyrate itself is also an excellent source of deupleted protons to support respiration-generated energy in enterocytes and colonocytes.

We make several arguments here to support our contention that S-adenosylmethionine and melatonin collaborate to support the production of deupleted water in the ER in enterocytes. The protons in the water derived from melatonin methyl groups can be traced back to severely deupleted hydrogen gas produced by the gut microbes during fermentation. We also discuss other processes that take place in the ER unrelated to melatonin, which may serve to maintain low deuterium in its solvent water. We further hypothesize that the deupleted water in the ER is transferred from the ER to the mitochondria via the cytoplasm, facilitated by the production of hydrogen peroxide serving as an intermediary, which serves to keep the molecule separate from the cytoplasmic water, in order to maintain its deupleted status.

The SCFA butyrate is another important metabolite produced by the gut microbes that has been found to be an essential nutrient for both the enterocytes and the colonocytes lining the gut barrier. Butyrate is a deupleted nutrient for the same reason that methyl groups are -- it obtains its protons from severely deupleted hydrogen gas produced during fermentation. Interestingly, butyrate stimulates the synthesis of tryptophan in the enterochromaffin cells in the gut barrier. Tryptophan is a precursor to serotonin and melatonin. Butyrate deficiency in the gut is linked to many chronic diseases.

Melatonin has been shown in an extensive literature to have remarkable beneficial properties as an antioxidant and in promoting a strong immune system to protect from infectious disease and promote rapid recovery. It is possible that its ability to derive deupleted water from methyl groups is an overlooked aspect of its healing properties. There is strong evidence that melatonin has remarkable benefits in protecting from and healing from COVID-19 and long COVID. Presumably due to the toxic effects of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, gut dysbiosis, as a consequence of COVD-19 and long COVID, results in melatonin deficiency in the gut, decreasing the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capabilities of the host. This may be a causal factor in neurological-cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration encountered as sequelae in these diseases.

While melatonin supplementation might be seen as beneficial to health, complications arise in sourcing it either from natural sources or synthetically. Sourcing it from melatonin-containing foods or tryptophan supplementation might be more appropriate for these reasons.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to this manuscript in planning, conception and design, writing and editing multiple drafts of the manuscript and reading and approving the final manuscript.

Funding

Stephanie Seneff received funding from Quanta Computer, Inc. under contract #6950759. The other authors received no funding for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data were associated with this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

References

- Pal, P.K.; Sarkar, S.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Tan, D.X.; Bandyopadhyay, D. Enterochromaffin cells as the source of melatonin: key findings and functional relevance in mammals. Melatonin Res. 2019, 2, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Kurth, S.; Pugin, B.; Bokulich, N.A. Microbial melatonin metabolism in the human intestine as a therapeutic target for dysbiosis and rhythm disorders. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raikhlin, N.T.; Kvetnoy, I.M.; Tolkachev, V.N. Melatonin may be synthesised in enterochromaffin cells. Nature 1975, 255, 344–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raikhlin, N.T.; Kvetnoy, I.M. Melatonin and enterochromaffine cells. Acta Histochem. 1976, 55, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Q. Distribution, function and physiological role of melatonin in the lower gut. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 3888–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Taghizadieh, M.; Mehdizadehfar, E.; Hasani, A.; Fard, J.K.; Feizi, H.; Hamishehkar, H.; Ansarin, M.; Yekani, M.; Memar, M.Y. Gut microbiota in neurological diseases: Melatonin plays an important regulatory role. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigstad, C.S.; Salmonson, C.E.; Rainey, J.F., III; Szurszewski, J.H.; Linden, D.R.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Farrugia, G.; Kashyap, P.C. Gut microbes promote colonic serotonin production through an effect of short-chain fatty acids on enterochromaffin cells. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Pan, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W.; Wang, X. Intestinal Crosstalk between Microbiota and Serotonin and its Impact on Gut Motility. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2018, 19, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Manchester, L.C.; Qin, L.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin: A Mitochondrial Targeting Molecule Involving Mitochondrial Protection and Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; García, J.A.; Escames, G.; Venegas, C.; Ortiz, F.; López, L.C.; Acuña-Castroviejo, D. Melatonin protects the mitochondria from oxidative damage reducing oxygen consumption, membrane potential, and superoxide anion production. J. Pineal Res. 2009, 46, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasoni, M.G.; Carloni, S.; Canonico, B.; Burattini, S.; Cesarini, E.; Papa, S.; Pagliarini, M.; Ambrogini, P.; Balduini, W.; Luchetti, F. Melatonin reshapes the mitochondrial network and promotes intercellular mitochondrial transfer via tunneling nanotubes after ischemic-like injury in hippocampal HT22 cells. J. Pineal Res. 2021, 71, e12747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seneff, S.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M. Cancer, deuterium, and gut microbes: A novel perspective. Endocr. Metab. Sci. 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; Seneff, S. Explaining deuterium-depleted water as a cancer therapy: a narrative review. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneff, S.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M. Taurine prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and protects mitochondria from reactive oxygen species and deuterium toxicity. Amino Acids 2025, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seneff, S.; Nigh, G.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M. Is Deuterium Sequestering by Reactive Carbon Atoms an Important Mechanism to Reduce Deuterium Content in Biological Water? FASEB BioAdvances 2025, 7, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneff S, Nigh G, Kyriakopoulos AM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: is impaired deuterium-depleted nutrient supply by gut microbes a primary factor? Biocell 2025 [In Press].

- Hay, S.; Pudney, C.R.; Scrutton, N.S. Structural and mechanistic aspects of flavoproteins: probes of hydrogen tunnelling. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 3930–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Manchester, L.C.; Liu, X.; Rosales-Corral, S.A.; Acuna-Castroviejo, D.; Reiter, R.J. Mitochondria and chloroplasts as the original sites of melatonin synthesis: a hypothesis related to melatonin's primary function and evolution in eukaryotes. J. Pineal Res. 2012, 54, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, C.; Ahmadinejad, N.; Wiegand, C.; Rotte, C.; Sebastiani, F.; Gelius-Dietrich, G.; Henze, K.; Kretschmann, E.; Richly, E.; Leister, D.; et al. A Genome Phylogeny for Mitochondria Among -Proteobacteria and a Predominantly Eubacterial Ancestry of Yeast Nuclear Genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004, 21, 1643–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengarten, H.; Meller, E.; Friedhoff, A.J. In vitro enzymatic formation of melatonin by human erythrocytes. . 1972, 4, 457–65. [Google Scholar]

- Manchester, L.C.; Poeggeler, B.; Alvares, F.L.; Ogden, G.B.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin immunoreactivity in the photosynthetic prokaryote Rhodospirillum rubrum: implications for an ancient antioxidant system. Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 1995, 41, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, G.M.; Kwak, Y.; Maynard, R.; Eyre-Walker, A. Endosymbioses Have Shaped the Evolution of Biological Diversity and Complexity Time and Time Again. Genome Biol. Evol. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, D.B.; Boyle, R.A.; Daines, S.J.; Sperling, E.A.; Pisani, D.; Donoghue, P.C.J.; Lenton, T.M. Eukaryogenesis and oxygen in Earth history. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, J.E.; Weaver, P.F. Fermentation and Anaerobic Respiration by Rhodospirillum rubrum and Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Bacteriol. 1982, 149, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Reiter, R.J. Mitochondria: the birth place, battle ground and the site of melatonin metabolism in cells. Melatonin Res. 2019, 2, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Sharma, R.; Rosales-Corral, S.; Zuccari, D.A.P.d.C.; Chuffa, L.G.d.A. Melatonin: A mitochondrial resident with a diverse skill set. Life Sci. 2022, 301, 120612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coon, S.L.; Klein, D.C. Evolution of arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase: Emergence and divergence. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2006, 252, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintela, T.; Gonçalves, I.; Silva, M.; Duarte, A.C.; Guedes, P.; Andrade, K.; Freitas, F.; Talhada, D.; Albuquerque, T.; Tavares, S.; et al. Choroid plexus is an additional source of melatonin in the brain. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 65, e12528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Manchester, L.C.; Terron, M.P.; Flores, L.J.; Reiter, R.J. One molecule, many derivatives: A never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? J. Pineal Res. 2006, 42, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezo, Y.; Clement, P.; Clement, A.; Elder, K. Methylation: An Ineluctable Biochemical and Physiological Process Essential to the Transmission of Life. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichevsky, M.I.; Friedman, I.; Newell, M.F.; Sisler, F.D. Deuterium Fractionation during Molecular Hydrogen Formation in a Marine Pseudomonad. J. Biol. Chem. 1961, 236, 2520–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducker, G.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D. One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, G.J.; KosálY, G.; Lidstrom, M.E. Formate as the Main Branch Point for Methylotrophic Metabolism in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 5057–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Noor, E.; Ramos-Parra, P.A.; García-Valencia, L.E.; Patterson, J.A.; de la Garza, R.I.D.; Hanson, A.D.; Bar-Even, A. In Vivo Rate of Formaldehyde Condensation with Tetrahydrofolate. Metabolites 2020, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarenhas, R.; Gouda, H.; Ruetz, M.; Banerjee, R.

- Schmidt, A.; Wu, H.; MacKenzie, R.E.; Chen, V.J.; Bewly, J.R.; Ray, J.E.; Toth, J.E.; Cygler, M. Structures of Three Inhibitor Complexes Provide Insight into the Reaction Mechanism of the Human Methylenetetrahydrofolate Dehydrogenase/Cyclohydrolase. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 6325–6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.-G.; Zhou, D.-D.; Wu, S.-X.; Huang, S.-Y.; Saimaiti, A.; Yang, Z.-J.; Shang, A.; Zhao, C.-N.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B. Health Benefits and Side Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Foods 2022, 11, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.D.; Wang, X.-Y.; Parsons, S.P.; Khan, W.I.; Huizinga, J.D. Abnormal absorptive colonic motor activity in germ-free mice is rectified by butyrate, an effect possibly mediated by mucosal serotonin. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2018, 315, G896–G907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-F.; Chen, X.; Tang, X. Short-chain fatty acid, acylation and cardiovascular diseases. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 657–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, K.; Venugopal, S.K.; Pisarello, M.J.L.; Gradilone, S.A. The Role of Gut Microbiome-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate in Hepatobiliary Diseases. Am. J. Pathol. 2023, 193, 1455–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Becker, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, D.; Ma, X. Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health? Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, S.; Zang, D.; Sun, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J. Butyrate as a promising therapeutic target in cancer: From pathogenesis to clinic (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2024, 64, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckschlager, T.; Plch, J.; Stiborova, M.; Hrabeta, J. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors as Anticancer Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, A.V.; Sadler, R.K.; Llovera, G.; Singh, V.; Roth, S.; Heindl, S.; Monasor, L.S.; Verhoeven, A.; Peters, F.; Parhizkar, S.; et al. Microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids modulate microglia and promote Aβ plaque deposition. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Kim, S.J.; Ko, E.K.; Ahn, S.; Seo, H.; Sung, M. Gut microbiota-associated bile acid deconjugation accelerates hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.M.; Yu, K.; Donaldson, G.P.; Shastri, G.G.; Ann, P.; Ma, L.; Nagler, C.R.; Ismagilov, R.F.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Hsiao, E.Y. Indigenous Bacteria from the Gut Microbiota Regulate Host Serotonin Biosynthesis. Cell 2015, 161, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Malhotra, P.; Maher, D.; Singh, V.; Dudeja, P.K.; Alrefai, W.; Saksena, S. Regulation of intestinal serotonin transporter expression via epigenetic mechanisms: role of HDAC2. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2013, 304, C334–C341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Chen, Y.-W.; Zhao, Z.-H.; Yang, R.-X.; Xin, F.-Z.; Liu, X.-L.; Pan, Q.; Zhou, H.; Fan, J.-G. Sodium butyrate reduces high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis through upregulation of hepatic GLP-1R expression. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, H.; Heng, C.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Qian, S.; et al. Amelioration of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by sodium butyrate is linked to the modulation of intestinal tight junctions in db/db mice. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10675–10689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, P.; Arefhosseini, S.; Bakhshimoghaddam, F.; Gurvan, H.J.; Hosseini, S.A. Mechanistic insights into the pleiotropic effects of butyrate as a potential therapeutic agent on NAFLD management: A systematic review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1037696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar, R.; Richard, C.S.; Santos, M.M. The role of butyrate in surgical and oncological outcomes in colorectal cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2021, 320, G601–G608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, E. ERO1: A protein disulfide oxidase and H2O2 producer. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 83, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestetti, S.; Galli, M.; Sorrentino, I.; Pinton, P.; Rimessi, A.; Sitia, R.; Medraño-Fernandez, I. Human aquaporin-11 guarantees efficient transport of H2O2 across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, B.P.; Weissman, J.S. The FAD- and O2-Dependent Reaction Cycle of Ero1-Mediated Oxidative Protein Folding in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailloux, R.J.; Mori, M. Mitochondrial Antioxidants and the Maintenance of Cellular Hydrogen Peroxide Levels. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7857251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneff, S. Is deuterium fractionation a major controlling factor in human metabolism and cancer? An essential role for proline. Preprints , 2024. 19 June. [CrossRef]

- Mercedes-Camacho, A.Y.; Mullins, A.B.; Mason, M.D.; Xu, G.G.; Mahoney, B.J.; Wang, X.; Peng, J.W.; Etzkorn, F.A. Kinetic Isotope Effects Support the Twisted Amide Mechanism of Pin1 Peptidyl-Prolyl Isomerase. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 7707–7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibi, H.; Chernobrovkin, A.L.; Eriksson, G.; Saei, A.A.; Timmons, Z.; Kitchener, A.C.; Kalthoff, D.C.; Lidén, K.; Makarov, A.A.; Zubarev, R.A. Abnormal (Hydroxy)proline Deuterium Content Redefines Hydrogen Chemical Mass. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 2484–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetten MR, Schoenheimerz R. The metabolism of I(-)-proline studied with the aid of deuterium and isotopic nitrogen. JBC 1944; 153(1): 113-132.

- Schönbrunner, E.R.; Schmid, F.X. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase improves the efficiency of protein disulfide isomerase as a catalyst of protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89, 4510–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCoursey, T.E.; Cherny, V.V. Deuterium Isotope Effects on Permeation and Gating of Proton Channels in Rat Alveolar Epithelium. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997, 109, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werck-Reichhart, D.; Feyereisen, R. Cytochromes P450: a success story. Genome Biol. 2000, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ma, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, X.; Huai, C.; Shen, L.; Zhang, N.; He, L.; et al. Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and Drug Metabolism in Humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Idle, J.R.; Krausz, K.W.; Gonzalez, F.J. Metabolism of melatonin by human cytochromes p450. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005, 33, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerecke, C.; Rodrigues, C.E.; Homann, T.; Kleuser, B. The Role of Ten-Eleven Translocation Proteins in Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 861351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Läpple, F.; Von Richter, O.; Fromm, M.F.; Richter, T.; Thon, K.P.; Wisser, H.; Griese, E.-U.; Eichelbaum, M.; Kivistö, K.T. Differential expression and function of CYP2C isoforms in human intestine and liver. Pharmacogenetics 2003, 13, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Somers, V.K.; Xu, H.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Covassin, N. Trends in Use of Melatonin Supplements Among US Adults, 1999-2018. JAMA 2022, 327, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Future Market Insights. Melatonin Market Analysis—Size, Share, and Forecast from 2025 to 2035. [last accessed , 2025]. https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/melatonin-market. 10 June.

- Arnao, M.B.; Giraldo-Acosta, M.; Castejón-Castillejo, A.; Losada-Lorán, M.; Sánchez-Herrerías, P.; El Mihyaoui, A.; Cano, A.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Melatonin from Microorganisms, Algae, and Plants as Possible Alternatives to Synthetic Melatonin. Metabolites 2023, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, R.C.; McDougle, C.J.; Schumacher, M.; Olcese, J.; Mason, J.W.; Heninger, G.R.; Price, L.H. Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on nocturnal melatonin secretion in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993, 76, 1160–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, S.; Nicolaus, C.; Garmundi, A.; Rial, R.V.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Ortega, E.; Ibars, C.B. Effect of orally administered l-tryptophan on serotonin, melatonin, and the innate immune response in the rat. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 267, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamfar, W.W.; Khraiwesh, H.M.; Ibrahim, M.O.; Qadhi, A.H.; Azhar, W.F.; Ghafouri, K.J.; Alhussain, M.H.; AlShahrani, A.M.; Alghannam, A.F.; Abdulal, R.H.; et al. Comprehensive review of melatonin as a promising nutritional and nutraceutical supplement. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Analysis, Nutrition, and Health Benefits of Tryptophan. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordjman, S.; Chokron, S.; Delorme, R.; Charrier, A.; Bellissant, E.; Jaafari, N.; Fougerou, C. Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Q.; Shao, J.; Liang, S.; Yu, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, C. The long-term health outcomes, pathophysiological mechanisms and multidisciplinary management of long COVID. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecon, E.; Fernandois, D.; Renault, N.; Coelho, C.F.F.; Wenzel, J.; Bedart, C.; Izabelle, C.; Gallet, S.; Le Poder, S.; Klonjkowski, B.; et al. Melatonin drugs inhibit SARS-CoV-2 entry into the brain and virus-induced damage of cerebral small vessels. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, E.K.; Cecon, E.; Monteiro, A.W.A.; Silva, C.L.M.; Markus, R.P. Melatonin inhibits LPS-induced NO production in rat endothelial cells. J. Pineal Res. 2009, 46, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, J.R.; González-Yanes, C.; Maldonado, M.D. The role of melatonin in the cells of the innate immunity: a review. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 55, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, A.; Bagherifard, A.; Koosha, F.; Amiri, S.; Karimi-Behnagh, A.; Reiter, R.J.; Mehrzadi, S. Melatonin effect on platelets and coagulation: Implications for a prophylactic indication in COVID-19. Life Sci. 2022, 307, 120866–120866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Vico, A.; Calvo, J.R.; Abreu, P.; Lardone, P.J.; García-Mauriño, S.; Reiter, R.J.; Guerrero, J.M. Evidence of melatonin synthesis by human lymphocytes and its physiological significance: possible role as intracrine, autocrine, and/or paracrine substance. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 537–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.C.; Pandi, P.S.R.; Esquifino, A.I.; Cardinali, D.P.; Maestroni, G.J.M. The role of melatonin in immuno-enhancement: potential application in cancer. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2006, 87, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mauriño, S.; Pozo, D.; Carrillo-Vico, A.; Calvo, J.R.; Guerrero, J.M. Melatonin activates Th1 lymphocytes by increasing IL-12 production. Life Sci. 1999, 65, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyaard, L.; Hovenkamp, E.; A Otto, S.; Miedema, F. IL-12-induced IL-10 production by human T cells as a negative feedback for IL-12-induced immune responses. J. Immunol. 1996, 156, 2776–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, C.W.; Sugimura, R.; Kong, H. Locked in a pro-inflammatory state. eLife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salina, A.C.; Dos-Santos, D.; Rodrigues, T.S.; Fortes-Rocha, M.; Freitas-Filho, E.G.; Alzamora-Terrel, D.L.; Castro, I.M.; da Silva, T.F.F.; de Lima, M.H.; Nascimento, D.C.; et al. Efferocytosis of SARS-CoV-2-infected dying cells impairs macrophage anti-inflammatory functions and clearance of apoptotic cells. eLife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, S.; Zeng, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Deng, B.; Zhu, G.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Hardeland, R.; et al. Melatonin in macrophage biology: Current understanding and future perspectives. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 66, e12547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.Y.; Ahn, S.; Cho, Y.-S.; Seo, S.-K.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.-G.; Lee, S.-J. CYP2C19 Contributes to THP-1-Cell-Derived M2 Macrophage Polarization by Producing 11,12- and 14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid, Agonists of the PPARγ Receptor. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, Z.T.; Al Atrakji, M.Q.Y.M.A.; Mehuaiden, A.K. The Effect of Melatonin on Thrombosis, Sepsis and Mortality Rate in COVID-19 Patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 114, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A.; Prosch, H.; Zehetmayer, S.; Gysan, M.R.; Bernitzky, D.; Vonbank, K.; Idzko, M.; Gompelmann, D.; Sobh, E. Impact of persistent D-dimer elevation following recovery from COVID-19. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0258351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, P.H.; Bärtschi, C.; Spillmann, M.; Ehlert, U.; Von Känel, R. Effect of oral melatonin on the procoagulant response to acute psychosocial stress in healthy men: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J. Pineal Res. 2007, 44, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halma, M.T.J.; Plothe, C.; Marik, P.; Lawrie, T.A. Strategies for the Management of Spike Protein-Related Pathology. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; Nigh, G.; A McCullough, P.; Seneff, S. Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Activation, p53, and Autophagy Inhibition Characterize the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Spike Protein Induced Neurotoxicity. Cureus 2022, 14, e32361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Shafiei, M.S.; Longoria, C.; Schoggins, J.W.; Savani, R.C.; Zaki, H. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces inflammation via TLR2-dependent activation of the NF-κB pathway. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, P.I.; Lefringhausen, A.; Turni, C.; Neil, C.J.; Cosford, R.; Hudson, N.J.; Gillespie, J. ‘Spikeopathy’: COVID-19 Spike Protein Is Pathogenic, from Both Virus and Vaccine mRNA. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneff, S.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; Nigh, G.; A McCullough, P.; McCullough, P.A. A Potential Role of the Spike Protein in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e34872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardinali, D.P.; Brown, G.M.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Possible Application of Melatonin in Long COVID. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.; Sainz, R.M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: under promises but over delivers. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.-C.; Yang, C.-N.; Lee, W.-J.; Sheehan, J.; Wu, S.-M.; Chen, H.-S.; Lin, M.-H.; Shen, L.-W.; Lee, S.-H.; Shen, C.-C.; et al. Melatonin Enhanced Microglia M2 Polarization in Rat Model of Neuro-inflammation Via Regulating ER Stress/PPARδ/SIRT1 Signaling Axis. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2024, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvagno, F.; Vernone, A.; Pescarmona, G.P. The Role of Glutathione in Protecting against the Severe Inflammatory Response Triggered by COVID-19. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.J.; Liu, Z.-G. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-kappaκB signaling. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amioka, N.; Nakamura, K.; Kimura, T.; Ohta-Ogo, K.; Tanaka, T.; Toji, T.; Akagi, S.; Nakagawa, K.; Toh, N.; Yoshida, M.; et al. Pathological and clinical effects of interleukin-6 on human myocarditis. J. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, L.M.; Swank, Z.; Bartsch, Y.C.; Burns, M.D.; Kane, A.; Boribong, B.P.; Davis, J.P.; Loiselle, M.; Novak, T.; Senussi, Y.; et al. Circulating Spike Protein Detected in Post–COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Myocarditis. Circulation 2023, 147, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoninfante, A.; Andeweg, A.; Genov, G.; Cavaleri, M. Myocarditis associated with COVID-19 vaccination. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, E.; Motolani, A.; Campos, L.; Lu, T. The Pivotal Role of NF-kB in the Pathogenesis and Therapeutics of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhan, C.; Chen, L.; Lin, Z.; Song, Z. Thioredoxin-1 promotes the restoration of alveolar bone in periodontitis with diabetes. iScience 2023, 26, 107618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Cheng, Q.; Hu, Y.; Fan, X.; Liang, C.; Niu, C.; Kang, Q.; Wei, T. Melatonin antagonizes oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in retinal ganglion cells through activating the thioredoxin-1 pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 479, 3393–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djavaheri-Mergny, M.; Javelaud, D.; Wietzerbin, J.; Besançon, F. NF-κB activation prevents apoptotic oxidative stress via an increase of both thioredoxin and MnSOD levels in TNFα-treated Ewing sarcoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2004, 578, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smail, S.W.; Albarzinji, N.; Salih, R.H.; Taha, K.O.; Hirmiz, S.M.; Ismael, H.M.; Noori, M.F.; Azeez, S.S.; Janson, C. Microbiome dysbiosis in SARS-CoV-2 infection: implication for pathophysiology and management strategies of COVID-19. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1537456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonmatí-Carrión, M.; Rol, M.-A. Melatonin as a Mediator of the Gut Microbiota–Host Interaction: Implications for Health and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Casillas, A.; Fabrowski, M.; Brogna, C.; Cowley, D.; Redwan, E.M.; Uversky, V.N. Could the Spike Protein Derived from mRNA Vaccines Negatively Impact Beneficial Bacteria in the Gut? COVID 2024, 4, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, R.H.; Guan, R.; Kalmar, L.; Beier, S.; Horner, E.C.; Beristain-Covarrubias, N.; Yam-Puc, J.C.; Gerber, P.P.; Faria, L.; Kuroshchenkova, A.; et al. Stability of gut microbiome after COVID-19 vaccination in healthy and immuno-compromised individuals. Life Sci. Alliance 2024, 7, e202302529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, A.; Abulseoud, O.A. Melatonin: a ferroptosis inhibitor with potential therapeutic efficacy for the post-COVID-19 trajectory of accelerated brain aging and neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Author Correction: Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 408–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivelli, L.; Palmer, K.; Calandri, I.; Guekht, A.; Beghi, E.; Carroll, W.; Frontera, J.; García-Azorín, D.; Westenberg, E.; Winkler, A.S.; et al. Changes in cognitive functioning after COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer's Dement. 2022, 18, 1047–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).