1. Introduction

The gut microbiota represents the second gene pool in the human body and participates in the regulation of various biological processes [

1]. The mutually symbiotic relationship between microorganisms and the human body is vital for sustaining our health. However, a lack of effective communication between the host organism and the microbiome can contribute to the development of human diseases [

2]. The gut microbiota serves as an incredible reservoir of microorganisms. Variations in the composition of the gut microbiota occur depending on the particular anatomical area being examined [

3]. These differences are chiefly influenced by factors like pH level and concentration of oxygen. The greatest bacterial colonization occurs predominantly in the large intestine [

4]. The small intestine, under normal physiological conditions, is colonized by a specific number of microorganisms, from 10

4–5 CFU/ml in the proximal region and to 10

7–8 CFU/mL in the distal part [

5]. However, when the host's defence mechanisms are compromised, bacterial translocation and overgrowth can occur in the small or large intestine [

6,

7,

8].

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and intestinal methanogen overgrowth (IMO) are one of two types of gut microbiota disruptions [

9]. Despite extensive research on SIBO in recent years, it remains an overlooked issue for many specialists. Thanks to the latest non-invasive diagnostics methods, such as SIBO breath tests, diagnosis’s becoming more common [

6]. Breath tests enable the measurement of gases, such as hydrogen (H

2) and methane (CH

4), produced by intestinal bacteria as a result of carbohydrate fermentation and facilitate the identification of SIBO subtypes such as hydrogen-dominant, methane-dominant or hydrogen/methane–dominant [

10,

11]. In most cases of SIBO, H

2 is the primary byproduct. However, approximately 30% of individuals with SIBO harbour methane-producing

Archaea (

Methanobrevibacter smithii) in their gut [

12].

The primary cause of SIBO is identified as increased permeability to lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which trigger an inflammatory response and lead to chronic inflammation [

13]. However, it's important to remember that SIBO is just the tip of the iceberg—a dysfunction of many organs and a variety of diseases may contribute to excessive bacterial overgrowth and lead to SIBO [

14]. Common gastrointestinal symptoms like abdominal pain, nausea, bloating, gas, diarrhea, and/or constipation are considered the typical symptoms of dysbiosis [

15]. Moreover, these issues can result in malabsorption, leading to nutritional deficiencies (vitamin A, D, E, B12), hypoproteinemia, anemia and weight loss [

4,

16,

17,

18]. While SIBO is not a life-threatening condition, it can worsen the patient's health and underlying comorbidities [

19,

20,

21,

22].

Diet is a modifiable factor that plays a crucial role in shaping the composition, diversity and stability of the gut microbiota [

23,

24]. A diet rich in fiber and plant-based foods, supplemented with prebiotics, and low in choline and fat represents a healthy microbiota [

25]. Conversely, a regimen deficient in fiber, fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs), and characterized by an elevated intake of omega-6 fatty acids typical of a Western dietary pattern, may predispose to dysbiotic conditions [

25,

26]. This approach may lead to nutritional deficiencies and microbiota alteration [

27,

28,

29].

In treating SIBO, it is essential to focus on the proper functioning of the entire organism, including clinical symptoms and nutritional status, rather than solely attempting to eradicate or starve excessive microbial growth in the small intestine. Individuals experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms frequently turn to prolonged dietary restrictions, sometimes neglecting the significance of restoring microbial equilibrium in the gut [

23,

30]. Furthermore, patients blindly choose to consume only permitted products, often leading to an inadequate intake of fiber, calcium, or iron due to poor meal planning [

31,

32,

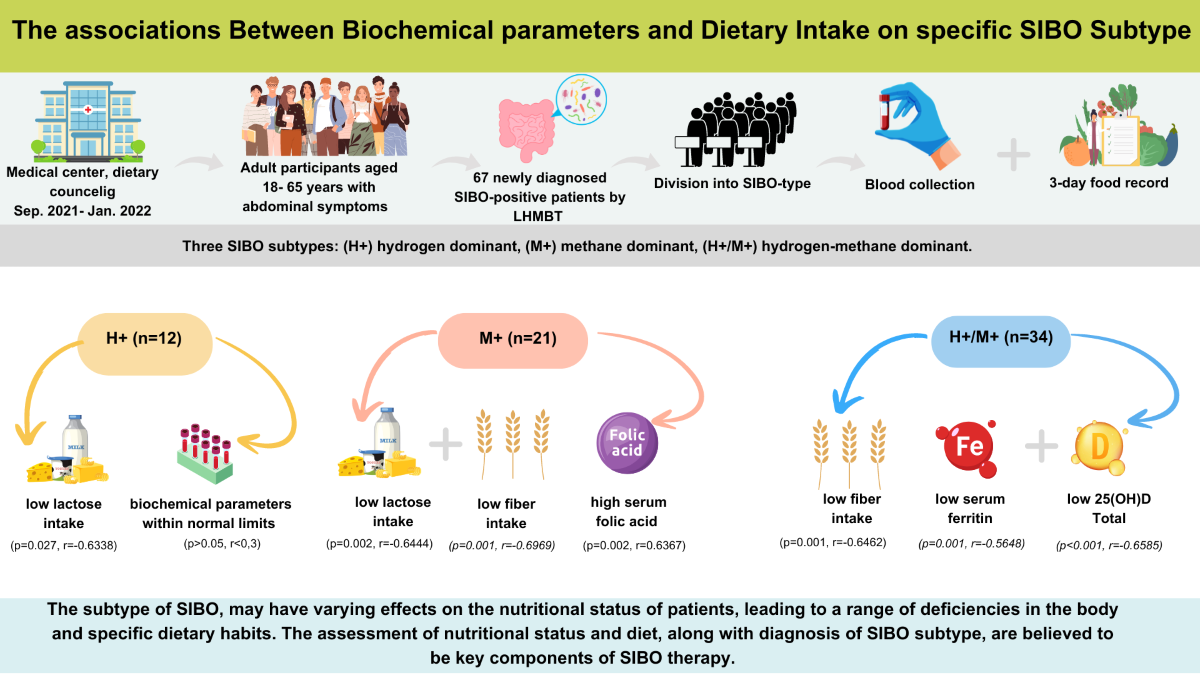

33]. However, it remains unclear whether a specific subtype of SIBO may predispose patients to a particular clinical presentation (i.e. nausea, diarrhea, constipation), which influences their dietary choices and patterns, or whether a patient’s baseline diet and nutritional intake may increase the risk of developing a specific SIBO subtype. The objective of this article is to investigate possible correlations between dietary intake, serum levels of biochemical parameters, and SIBO subtype in newly diagnosed SIBO patients.

2. Results

2.1. Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics

In the study, there were a combined total of 67 participants who had recently received a diagnosis of SIBO and were distributed among three distinct SIBO groups.

Table 1 depicts the demographic and anthropometric characteristics categorized by the SIBO subtype. The largest group comprised patients with H+/M+ (51%), followed by M+ (31%), with the H+ group being the smallest at 18%. Females comprised over 70% of each group. Age, weight, BMI, and the PAL were comparable among SIBO groups. However, there were statistically significant differences in height among the H+/M+ and H+ groups. Patients dominant in H+/M+ exhibited notably significantly lower height in comparison to the H+ group

(p=0.023). The clinical symptoms of the patients is described in our previous article [

34].

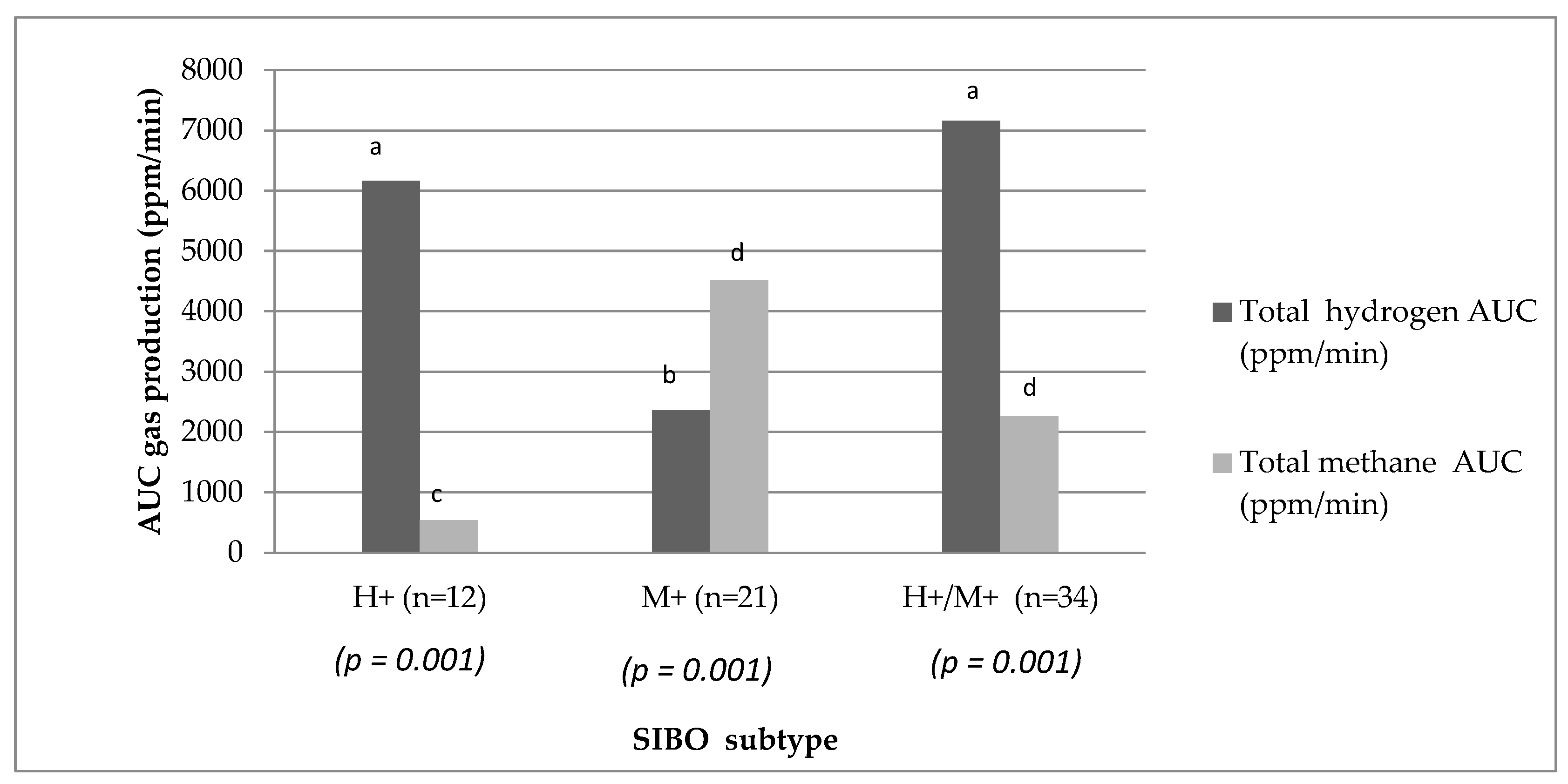

2.2. Hydrogen and Methane Production

The detailed results of gas concentrations expressed as area under the curve (AUC) in each group were extensively discussed in our previous article [

34]. The summary of these results is presented in

Figure 1. There were notable distinctions in the exhaled gases detected during the LHMBT among SIBO Subtype

(p = 0.001).

2.3. Biochemical Parameters

The serum levels of vitamin D, B12, folic acid, ferritin, and iron are described in

Table 2, whereas

Table 3 evaluates the percentage of individuals within each group exhibiting deficient, excessive, or normal concentrations of the aforementioned biochemical parameters. No discernible disparities were observed among groups concerning serum vitamin D levels; nevertheless, the median concentration of vitamin D within each group was below the recommended optimal threshold. Decidedly less than half of the patients in each group, ranging from 23% to 44%, exhibited optimal levels of vitamin D concentration. Regarding vitamin B12, the values remained consistent across groups. However, it is noteworthy that among H+ dominant patients, 50% exhibited a borderline level of B12. In the remaining groups M+ and H+/M+, the majority presented with optimal concentrations of vitamin B12. During the comparison of serum levels of folic acid, it was noted that the concentration remained similar across the three groups. More than 80% of individuals in each group exhibited optimal concentrations of folic acid. The median concentration of iron in each group was within the normal range, and no significant differences were observed between the groups.

Only a small percentage of individuals exhibited either deficient or excessive serum iron levels. Significant disparities in serum ferritin levels were observed between the two groups, with H+ patients demonstrating elevated ferritin levels compared to H+/M+ individuals (p=0.042). Although more than 50% of M+ dominant patients displayed a tendency towards iron deficiency (<10.0-15.0 ng/ml), none of the H+ dominant patients exhibited iron deficiency. However, these discrepancies were not deemed statistically significant. Moreover, over 50% of the H+ group exhibited optimal ferritin levels.

2.4. Energy and Macronutrients Intake

Table 4 presents the median daily intake of energy and macronutrients, whereas

Table 5 shows percentage of people who met the nutrient requirements. No differences were observed in energy intake between the SIBO subtype. Only 50% of participants in the H+ dominant group met their total energy requirements (TEE). Moreover, over 50% of patients in the M+ group exhibited a daily energy intake lower than the recommended total energy requirement for the day. However, statistical significance was not attained in this regard. The carbohydrate intake throughout the day remained at a similar level across all three groups. Furthermore, over 40% of all participants in each group did not meet the EAR requirements for carbohydrate intake.

The fiber intake varied significantly between groups, with the M+ group exhibiting higher fiber consumption than the H+ group. Meanwhile, the H+/M+ group demonstrated similarities to both of the other groups (p=0.036). All individuals in the H+ group (100%) had lower fiber intake than the AI. Only 20% of individuals in the H+ dominant group and M+ group met their fiber requirements. Looking specifically at the consumption of fermentable sugars, only the intake of lactose differed significantly among patients. A markedly lower intake was observed in the H+ group compared to the H+/M+ group (p=0.001). The daily fat intake did not differ between the groups; however, when considering the percentage contribution of fat, the H+ group exhibited a significantly lower fat content compared to the M+ and H+/M+ groups (p=0.019). Interestingly, over 70% of patients in the M+ and H+/M+ groups had statistically higher daily fat intake compared to the RI (p=0.032).

The consumption of SFA, MUFA and Omega-3 fatty acids did not differ significantly between the groups. However, over 50% of individuals in each group had higher SFA intake than the recommended level. The ratio of omega-3/6 fatty acids was higher than what is typically recommended in the literature in all participants. The daily protein intake, both in grams and as a percentage, was similar across all groups. However, it was observed that the protein intake per gram per kilogram per day exceeded the recommended norm in over 70% of all patients.

2.5. Micronutrients Intake in SIBO Type

Table 6 delineates the median daily consumption of selected vitamins and minerals.

Table 7 presents the percentage of individuals within each SIBO type who met the requirements according to micronutrients intake. The intake of the examined vitamins (A, D, E, B12, folate) and minerals (iron, calcium) did not exhibit statistically significant differences between the groups. An overwhelming majority of individuals in each group met the recommended daily intake for vitamin A according to the EAR.

In over 87% of all patients in the study, lower vitamin D intake was observed compared to the AI. The majority of individuals (58%) who did not meet their vitamin B12 requirements are those with H+ SIBO (p=0.039) compared to M+ and H+/M+. Over 67% of all patients had inadequate intake of calcium compared to the EAR. Less than 50% of all patients met the EAR for folate. More than 50% of all patients met the EAR for iron and RI for vitamin E.

2.6. Correlations

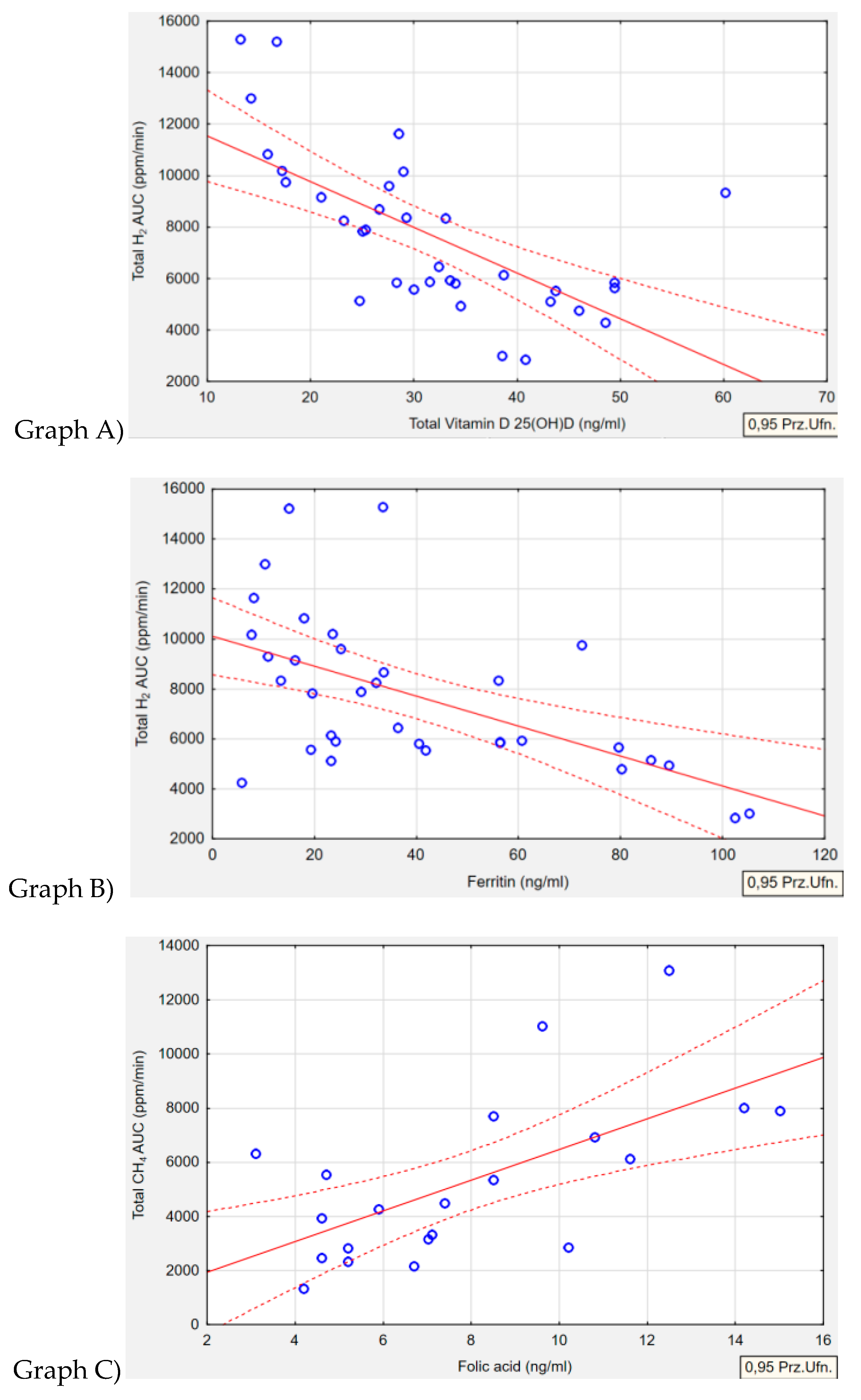

2.6.1. Biochemical Parameters Correlations

Table 8 outlines the relationships between type of gas produced by the microorganism and serum level of biochemical parameters. An inverse correlation was observed in the H+/M+ group between serum vitamin D and total AUC of H

2 gas

(p<0.001, r=-0.6585). It was noted that higher concentrations of exhaled H

2 were associated with significantly lower levels of serum vitamin D (

Figure 2; Graph A). A similar inverse correlation was found in the same H+/M+ group regarding ferritin levels. Lower serum ferritin concentrations were associated with higher levels of H

2 gas production (

p=0.001, r=-0.5648) (

Figure 2; Graph B). In reference to the correlation between folate concentration and methane levels in the M+ group, it was observed that higher folate levels were solely associated with increased CH

4 concentrations

(p=0.002, r=0.6367) (

Figure 2; Graph C). No correlation was detected between the levels of exhaled H

2 or CH

4 and the serum concentrations of iron or B12 in any of the groups. Furthermore, in the H+ group, no correlations were observed in terms of biochemical parameters.

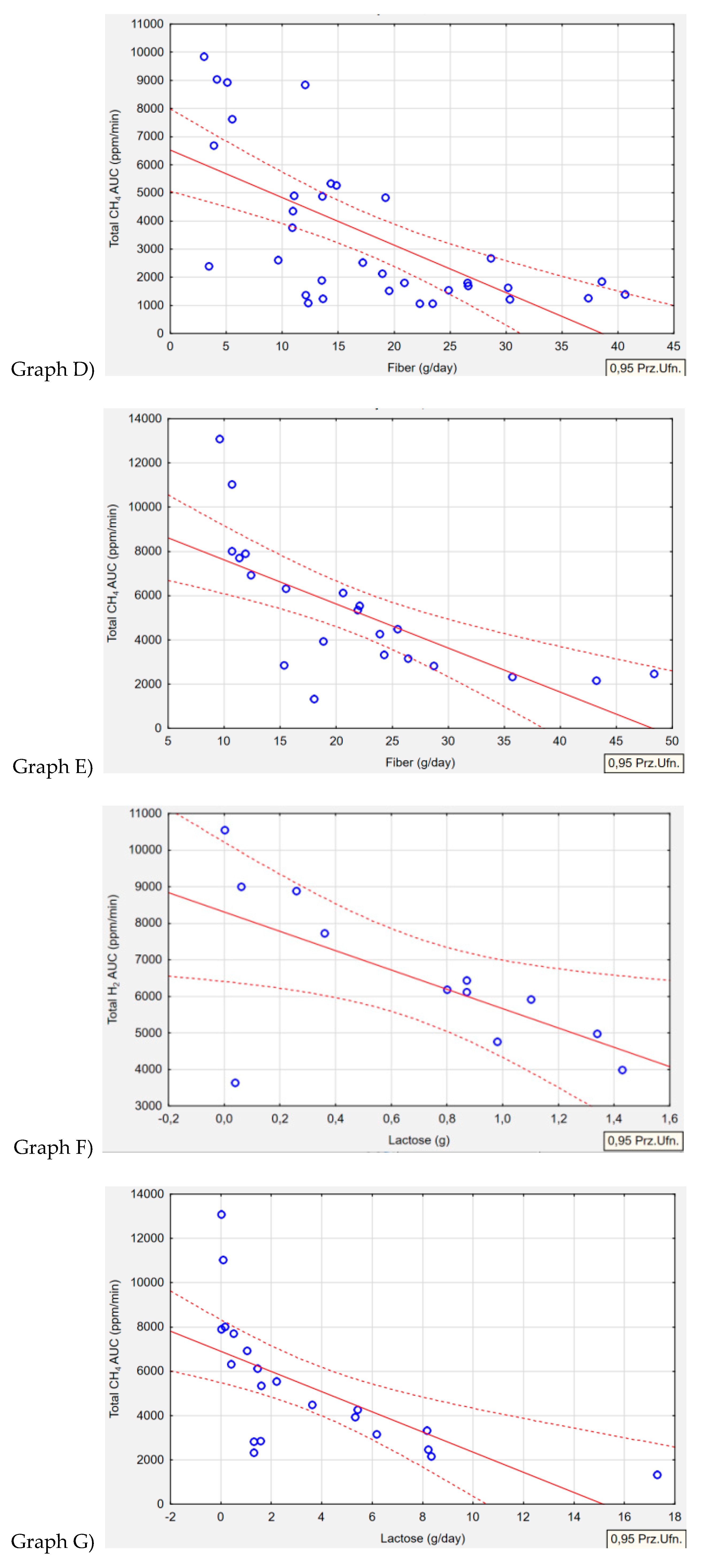

2.6.2. Dietary Correlations

Table 9 summarizes relationships between type of gas produced by the microorganism and nutrient intake. Regarding the intake of macronutrients and selected vitamins and minerals, four correlations were identified. In the H+/M+ group

(p=0.001, r=-0.6462) and M+ group

(p=0.001, r=-0.6969), an association was observed between fiber intake and exhaled CH

4 gas. The higher the concentration of CH

4 gas production, the lower the intake of fiber in both groups (

Figure 3, Graph D, Graph E). Lactose intake correlated with both H

2 and CH

4 gas production. In the H+ group, higher levels of exhaled H

2 gas were associated with lower lactose intake in the diet

(p=0.027, r=-0.6338) (

Figure 3, Graph F). Conversely, in the M+ group, lower lactose intake was correlated with higher levels of exhaled CH

4 gas

(p=0.002, r=-0.6444) (

Figure 3, Graph G).

The remaining parameters, including energy intake, protein, fat, carbohydrate intake, as well as vitamins A, D, E, B12, folate, and minerals such as calcium and iron, were not correlated with exhaled H2 or CH4.

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scientific study to investigate the association between the biochemical parameters, dietary intake, inclusive of nutrients and energy, and SIBO subtype. In this study, several inverse relationships were revealed between the H+/M+ group and serum ferritin, serum vitamin D and ingested fiber. Meanwhile, the M+ group showed correlations with serum folate, fiber intake, and lactose intake. The H+ group only demonstrated associations with lactose intake.

3.1. Biochemical Parameters

3.1.1. Vitamin D

In the proximal part of the small intestine, SIBO may instigate the deconjugation of bile acids which reduce the solubilization of dietary fat within micelles [

35]. This alteration leads to the presence of unconjugated bile acids and a shift in their site of reabsorption, consequently leading to reduced absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E) [

35].

In our study, the inverse correlation noted solely within the H+/M+ group between vitamin D and H

2 gas concentration could potentially be associated with the median amount of exhaled H

2 gas during the lactose breath test. In the H+/M+ group, the concentration was 7155 ppm/min AUC, compared to 6160 ppm/min AUC in the H+ group and 2306 ppm/min AUC in the M+ group. However, the values only reached a statistically significant difference in the H+/M+ group and M+ group. It is important to consider that methane-producing

Archea are a hydrogen cross-feeder, hence the lack of differences in H

2 breath concentrations between the H+/M+ and H+ groups may be attributed to this phenomenon [

12]. Although each of the patients examined were recently diagnosed with SIBO, evidently, higher H

2 levels in exhaled breath contributed to the impairment of vitamin D absorption and a more pronounced state of dysbiosis could potentially affect this group. This is corroborated by other studies, which suggest that in more severe cases of SIBO, vitamin D deficiencies will manifest [

36]. To date, few studies have assessed vitamin D levels in patients with SIBO, and none of these studies have correlated vitamin D levels and SIBO subtype

. In a study conducted by Zhang et al., significantly lower serum vitamin D levels were observed in pregnant patients with gestational diabetes and SIBO compared to the control group without SIBO [

37]. Among patients with concurrent SIBO and chronic pancreatitis or systemic sclerosis, no differences were noted in vitamin D levels compared to the group without SIBO [

38,

39]. In a case report study involving a patient with a treatment-resistant sacral pressure sore, compounded by underlying SIBO, and observed malnutrition leading to low levels of various nutrients, including vitamin D, despite supplementation. Notably, the eradication of overgrowth alone resulted in an elevation of vitamin D levels [

40]. One consequence of vitamin D deficiency is hypocalcemia, and osteoporosis is a recognized manifestation of untreated SIBO [

41].

3.1.2. Ferritin and Iron

This study revealed that the lowest median level of ferritin (30.5 ng/ml), reflecting early iron deficiency, was observed in the H+/M+ group. The M+ group also had low ferritin levels (35.0 ng/ml), indicative of early deficiency of iron, but was not statistically significant with others groups. The H+ group exhibited optimal ferritin levels (62.0 ng/ml). This may suggest that overgrowth of both H2 bacteria and CH4 archea predisposes to impaired iron absorption, thus reducing ferritin levels. Interestingly, the median iron levels did not differ between the groups. It is worth noting that iron is a parameter that fluctuates throughout the day and does not reflect actual iron stores like ferritin does. Similar to the vitamin D concentration, the results demonstrated that only the amount of H2 gas produced in the H+/M+ group influences the serum ferritin concentration, resulting in lower ferritin levels and higher H2 gas concentrations in exhaled breath. This further supports the idea that a higher degree of bacterial fermentation from excessive overgrowth of H2-producing bacteria contributes to impaired iron absorption and ultimately affects iron storage in cells.

Ferritin is the most sensitive indicator of iron reserves and a valuable biomarker for evaluating iron deficiency (ID). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), low ferritin levels are defined as <15 μg/L for adults and <12 μg/L for children. Nevertheless, in clinical practice, iron deficiency can be identified when ferritin levels fall below 30 μg/L [

42]. Growing clinical research suggests that the gut microbiota significantly influences iron metabolism. Between 5% to 20% of the iron is assimilated in the duodenum, while 80% of the ingested iron is utilized by the intestinal microbiota, predominantly within the colon [

43]. The intestinal microbiota utilizes iron as a cofactor in proteins essential for its survival. In environments with low iron levels, certain bacterial species such as

Eubacterium recitale, Roseburia spp. experience a decrease in abundance, while members of the

Lactobacillaceae famili and

Enterobacteriaceae family (including

Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella, E. coli) increase in abundance [

44]. Therefore, considering iron supplementation in patients with iron deficiency and SIBO during bacterial eradication therapy seems to have negative consequences on the gut microbiota[

45].

3.1.3. Folic Acid

A distinct correlation was found between CH

4-producing

Achaea and heightened synthesis of serum folic acid. Currently there are no published studies that assess the concentration of folic acid in blood serum among patients with different types of SIBO overgrowth. One previous study by Platovsky et al. found that participants with higher folate levels had a 1.75 times greater likelihood of having SIBO than those with normal folate levels (95% CI=0.74-4.14) [

46]. Other studies, such as those by Marie et al. and Tauber et al. only studied patients with systemic sclerosis and did not find any differences in serum folic acid between the SIBO group and the control group [

39,

47]. In contrast, Kaniel et al. showed that lower serum folate level in SIBO patients after One Anastomosis Gastric Bypass Surgery did not differ when compared to patients without SIBO [

48].

Many authors have also postulated that SIBO is linked with normal or increased folate levels [

14,

49,

50,

51]. It is known that bacteria have the ability to synthesis other vitamins. The gut microbiota contributes significantly to the production and utilization of folate (vitamin B9) [

52]. Based on an assessment of human gastrointestinal bacterial genomes, approximately 13.3% of bacteria are equipped with the capability of synthesizing folate de novo, while 39% have the potential to produce folic acid when supplied with additional para-aminobenzoic acid from either other microorganism or food sources [

53]. Altogether, the microbiome holds promising therapeutic potential for addressing vitamin B9 level.

3.1.4. Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin)

The results of this study demonstrate that the level of vitamin B12 was not associated with any type of bacterial overgrowth in patients with SIBO, regardless of SIBO subtype. Perhaps in the case of vitamin B12 levels, at such an early stage of overgrowth, our patients did not experience significant deficiencies in vitamin B12. There is only one study by Madigan et al. [

54] that investigated the relationship between vitaminB12 and SIBO-phenotype, and revealed that methanogenic SIBO manifested only in an older population and was linked to a reduced occurrence of vitamin B12 deficiency. Future research should focus on assessing vitamin B12 levels and SIBO subtypes at a variety of patient age groups to determine if changes in this parameter may be linked to time from diagnosis, degree of overgrowth or patient age.

3.2. Dietary Intake

3.2.1. Fiber

Decreased consumption of fiber-rich products by patient’s in this study, alongside higher levels of bacterial fermentation by

Archaea, may suggest an association between

Achaea and poor tolerance to fiber products. Furthermore, the lower fiber intake may have contributed to exacerbating CH

4 overgrowth. It is worth noting that in our previous study, patients in the M+ group exhibited a higher percentage of constipation compared to patients in H+ group who had a higher median consumption of fiber in the present study [

34]. It is possible that due to existing constipation, patients increased their fiber intake compared to those in the H+ dominant group. In terms of diarrhea, our research has demonstrated that those with H

2-dominant SIBO exhibit higher rates of diarrhea and the lowest fiber intake [

34]. It is possible that individuals in this group were concerned about exacerbating their symptoms, leading to a reduction in fiber consumption. However, the decreased intake of fiber seen among subjects in this study could increase the risk of SIBO development by slowing down gut motility and disrupting bacterial balance. Our findings are consistent with prior research, indicating that increases of

Methanobrevibacter, Prevotella, Collinsella, Dialister or Biophila were strongly linked with a lower intake of fiber in overweight pregnant women [

55]. A limited consumption of fiber encourages the proliferation of microorganisms that have the ability to utilize mucus glycoproteins secreted by the host [

56]. This can potentially affect the integrity of the colonic mucus barrier and lead to the overgrowth and proliferation of pathogens [

57]. According to other studies, patients with SIBO consumed less fiber than control groups [

22,

58]. In contrast to these findings, Cortez et al. did not find any difference in fiber intake among overweight patients with SIBO or not [

59]. Saffouri et al. observed that a brief change in fiber intake can have a negative impact on a patient's well-being. During a 7-day shift from a high-fiber diet (>11 cal/1000 cal) to a low-fiber diet (<10g/1000 cal), gastrointestinal symptoms developed in 80% healthy volunteers, with SIBO developing in 2 out of 16 individuals [

60].

3.2.2. Lactose

This study confirms that lower consumption of lactose-rich products is associated with the higher concentrations of exhaled H

2 and CH

4. This could indicate a relationship between the amount of lactose consumed throughout the day and the extent of certain bacterial overgrowths. In our present research the H+ group had the lowest amount of lactose consumption. This may, be connected with the highest degree of diarrhea in the H

2 dominant group which was demonstrated in our previous study [

34]. According to Jo et al. [

61] H

2-dominant SIBO was found to be significantly more prevalent in patients with lactase deficiency compared to healthy controls, with rates of 27.6% versus 6.7%, respectively. In another study, SIBO was recorded in 90% of elderly individuals diagnosed with lactose malabsorption (LM) compare to 20% of control group [

62]. Eradication of bacterial overgrowth corresponded with the alleviation of LM [

62]. A retrospective analysis unveiled the prevalence of carbohydrate malabsorption among patients undergoing the lactulose breath test, and emphasized that SIBO may elevate the probability of lactose Intolerance. However, intolerance in such cases is reversible with appropriate SIBO treatment [

63].

It is well estbalished that SIBO contributes to malabsorption syndrome [

64]. The overgrowth of microorganisms leads to reduced availability of sugars consumed by bacteria [

35]. Bacteria release toxins and metabolic byproducts, which can impair the integrity of the epithelial layer covering the intestinal villi [

35]. Consequently, this diminishes the function of brush-border disaccharidases and impaires disaccharide digestion [

63]. The increased bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates notably induces abdominal symptoms, especially an elevated production of H

2 gas, which is primarily associated with IBS-Diarrhea [

65]. Signs of lactose intolerance commonly appear when lactase activity falls below 50% [

66]. Furthermore, the majority of people with lactase non-persistence can manage small quantities of lactose (less than 12 g, roughly equivalent to one cup), particularly when consumed alongside with other products in diet or when divided throughout the day [

66].

This is the first study to evaluate lactose consumption in patients with specific SIBO subtype, however seeing as low lactose intake was found in both H+ and M+ groups, the results align with current literature that supports patients with SIBO are likely already consuming less lactose at baseline for symptom control. These results add to the growing body of literature to address dietary intake of lactose in patients with SIBO, regardless of subtype.

3.2.3. Fat

This is the first study to evaluate fat intake based on SIBO subtype. The H

2 dominant group consumed significantly less fat compared to the other two groups. Over 70% of patients in the M+ and H+/M+ groups had excessive fat intake compared to the recommended dietary guidelines. Previous to these results, one study conducted on Sprague-Dawley rats revealed that animals fed a high-fat diet exhibited higher abundance of

Methanobrevibacter smithii in the duodenum, ileum, and cecum compared to those fed a normal diet [

67]. Only three other studies have assessed total fat intake in patients with SIBO and without SIBO by using the Hydrogen Breath Test or Hydrogen-Methane breath test [

22,

58,

59]. All authors did not find any significant differences in fat intake between the SIBO group and the control group [

22,

58,

59]. A study conducted in Iran on patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia demonstrated a higher intake of fats compare to the control group (38.3% vs. 37.4%) [

68].

In clinical practice, it is often observed that patients with SIBO independently increase the fat intake in their diet due symptoms experienced after consuming carbohydrates. However, it is essential to remember that certain types of fat can either positively or negatively affect the gut microbiota and colonic pH [

26]. Laboratory studies have indeed shown that lipids in the duodenum can slow down small bowel movement and interfere with the clearance of intestinal gas, which leads to gas retention and bloating [

69]. A systematic review has indicated that dietary fat may have a significant impact on the onset of symptoms related to functional dyspepsia [

70].

Lower fat intake in the H+ group could have been influenced by a higher degree of diarrhea and poor fat tolerance. Depending on the type of overgrowth and current symptoms, the appropriate fat requirements should be determined.

3.2.4. Vitamin B12

The consumption of vitamin B12 in the H+ group reflects the borderline serum blood levels, where over 50% of patients had significant concentrations and intake at the borderline of normal compared to other two groups. None of the existing studies to- date evaluate the intake of vitamin B12 in different subtypes of SIBO.

3.2.5. Other Nutrients Intake

The remaining dietary components such as energy intake, protein, total carbohydrates, fructose, SFA, MUFA PUFA, omega-3/omega-6 ratio, cholesterol, vitamin A and E, folic acid, calcium, and iron were not associated with any changes based on the type of SIBO. There are no previous studies that have assessed the intake of these parameters and SIBO subtype.

4. Materials and Methods

This was an observational study performed during the period of September 2021 to January 2022 in Warsaw, Poland. This research serves as an extension of previous research, wherein the correlation between three subtypes of SIBO and selected anthropometric parameters was investigated [

34]. In the context of this article, our objective is to demonstrate potential associations between in biochemical parameters and dietary intake in patients with three subtypes of SIBO.

4.1. Sample

Adult participants between the ages of 18 to 65 years old presenting with existing abdominal symptoms occurring at least three times per month in the past six months were recruited from a dietary counseling and medical center. The study only included those individuals who newly had SIBO confirmed through a non-invasive hydrogen-methane breath test with lactulose substrate (LHMB) and have not started yet antibiotic therapy or use of often recommended elimination diet. Participants were required to adhere to a meticulous preparatory procedure for the study, failure to meet this criteria precluded their inclusion in the study. The exclusion criteria included individuals exhibiting a medical history indicative of eating disorders, a confirmed diagnosis of celiac disease, the presence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), hypoglycemia, hematophobia and pregnant and lactating women. The research protocol received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee at the Institute of Human Nutrition in Warsaw, Poland (n 13/2021,date 07.05.2021). All patients provided written consent to participate in the study.

4.2. Lactulose Hydrogen–Methane Breath Test (LHMB)

Among all patients, the lactulose breath tests were conducted and analyzed in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the North American Breath Testing Consensus Guideline (

Table 10) [

10].

The te

The test enabled the measurement of gas concentrations (H2, CH4, CO2) in the collected breath samples of participants during exhalation. The initial gas samples were taken prior to the administration of lactulose solution (10g) diluted in water (150ml) and subsequent post-lactose samples were collected over 180 minutes at every 10 or 20 minutes. The levels of H2 and CH4 in the exhaled samples were measured in parts per million (ppm). The examination utilized a QuinTron BreathTracker (v 3.0, Warsaw, Poland) for analysis.

4.3. Biochemical Assessment

Laboratory investigations were employed to assess the biochemical parameters in all patients. We aimed to determine the levels of the following parameters: folic acid, vitamin D 25(OH)D Total, ferritin, iron, and vitamin B12. The participants’ venous blood samples were drawn for this anlysis by qualified nurses in a certified ALAB diagnostics laboratory in Warsaw, Poland. The patients were instructed to discontinue all supplements (especially vitamin D, iron and B vitamins) one week prior to the examination and arrive the laboratory in a fasted state before blood draw. The serum concentrations of total vitamin D, folic acid, ferritin and vitamin B12 were determined utilizing the direct chemiluminescence metod [

71]. In parallel, the iron concentration was assessed through spectrophotometry methodology on the Abbott ANLINITY I analyzer [

72]. The ALAB laboratory reported total serum vitamin D 25(OH)D concentrations according to the following category: deficiency (<20 ng/ml), suboptimal (20-30 ng/ml), optimal (>30-50 ng/ml) and high (50-100 ng/ml). Normal levels of vitamin B12 were defined by the laboratory as (200-883 pg/ml), however we categorized vitamin B12 concentrations as borderline (<200.0-300.0 pg/ml) or optimal (300.0-883.0 pg/ml) which were in accordance with other authors [

73,

74]. The laboratory established normal folic acid levels as (3.1-20.5 ng/ml). We classified folic acid concentrations as low (<2.1-3.0 ng/ml), borderline (>3.0-4.0 ng/ml) and optimal (>4.0-20.5 ng/ml), in another article, a similar classification was applied [

75]. The normal reference range for serum ferritin levels defined by the laboratory was (21.0-270 ng/ml) for male and (4.6-204.0 ng/ml) for female. Serum iron levels were reported by the laboratory as low (<37.0 µg/dl), optimal (37.0-145.0 µg/dl) and high (>145.0 µg/dl) for women and low (<59.0 µg/dl), optimal (59.0-158.0 µg/dl) and high (>158.0µg/dl) for men. Given the broad range of serum ferritin norms, recognized as a significant indicator of iron stores, we have delineated the following ferritin ranges as: iron deficiency (<10.0-15.0 ng/ml), early iron deficiency (>15.0-50.0 ng/ml) or optimal (>50.0-200.0 ng/ml) for women and (>50.0-270.0 ng/ml) for men, which are also widely accepted by other authors [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80]. The serum concentrations of all biochemical parameters were expressed as both a median and a percentage of individuals exhibiting deficient, optimal or excessive concentrations compare to recommended levels. Data regarding age, height, and body mass were acquired from patients during the body composition analysis, which was extensively described in our previous article [

34].

4.4. Dietary Assessment Tool

Dietary analysis relied on self-reported data. To evaluate dietary intake, each participant was instructed to meticulously record a 3-day food intake diary, encompassing two week days (Monday to Friday) and one weekend day (Saturday or Sunday) before considering any elimination diet. During this 3-day period, participants were asked to maintain their typical eating patterns. Patients were provided with a standard template to fill out, along with accompanying instructions containing: detailed composition of each meal, quantity of each meal ingredient recorded in household measures or in grams, type of culinary processing (i.e cooking, frying, baking), all snacks, sweets, sweetened beverages, alcohol, additive such as sugar or cream for tea/coffee, as well as time and location of meal consumption. Additionally, the template included an example of the expected meal descriptions. A dietitian verified the accuracy of all completed records. Data from the 3-day food records were entered into the nutrition program „DietetykPro”(Warsaw, Poland), utilizing the database of the National Food and Nutrition Institute in Warsaw and the United States Department of Agriculture Foods Database [

81]. Median daily values were derived from the information collected from the 3-day dietary records. The median intake of nutrients: protein (g, % energy, g/kg), carbohydrates (g, % energy), fiber (g), lactose (g), fructose (g), fat (g, % energy), saturated fatty acids (SFA) (g, % energy), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) (g, % energy), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) (g, %energy), omega-3 (g), omega-6 (g), cholesterol (mg), vitamin A (µg retinol equivalents), vitamin E (mg α-tocopherol equivalents), vitamin D (µg), folate (µg), vitamin B12 (µg),calcium (mg),and iron (mg) were estimated and compared with the relevant nutritional standards and guidelines [

82]. The median energy intake was justaposed with the individual energy requirements, which the patients had estimated through the body composition analysis delineated in the preceding article [

34]. The total energy expenditure (TEE) was calculated by combining the basal energy expenditure (BEE) derived from the body composition assessment and the physical activity index (PAL) [

83]. Physical activity levels were evaluated through the utilization of the validated KomPAN

® questionnaire mentioned in preceding article [

34]. The ratio of omega-3/6 fatty acids was compared with the typical recommended ratio mentioned widely in the literature [

84,

85]. All results were presented as a percentage of individuals with insufficient, adequate and excessive consumption compared to estimated average requirement (EAR), adequate intake (AI), and reference intake (RI) norms for all nutrients [

82].

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistica 13.0 Software. Both parametric and non-parametric tests were employed to analyze independent categorical variables. The serum concentration of iron (µg/dl), intake of: energy (kcal), TEE (kcal), carbohydrates (%), protein (%, g/kg), fat (g, %), omega-6/3 ratio, and folate (µg) were evaluated by Univariate ANOVA, with a post-hoc Turkey test. The serum level of: total vitamin D (ng/ml), vitamin B12 (pg/ml), folic acid (ng/ml), ferritin (ng/ml), and intake of: BEE (kcal), carbohydrates (g), fiber (g), lactose (g), fructose (g), protein (g), SFA (g, %), MUFA (g, %), omega-3, omega-6, PUFA (g, %), cholesterol, vitamins A (µg),E (µg),D (µg) and B12 (µg), calcium (mg), iron (mg) and median H2 (ppm/min) and CH4 (ppm/min) production values were analyzed with the use of the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test, verified on the basis of the Shapiro-Wilk test, with a post-hoc Bonferroni test. All analyses were deemed statistically significant with a threshold of p<0.05. Pearson correlation analyses were employed to assess the correlation between gas production and biochemical parameters, energy with dietary intake in three SIBO subtypes (p≤ 0.05, r≥-/+ 0.3).

4.6. Outcome Measures

The identified gases were systematically analyzed and classified into three distinct subtypes of SIBO according to predefined guidelines:

Hydrogen-dominant SIBO (H+): H2>20 ppm from baseline within 90 min, CH4<10 ppm any time during the test;

Methane-dominant SIBO (M+): H2<20 ppm from baseline within 90 min, CH4>10 ppm any time during the test;

Hydrogen–methane-dominant SIBO (H+/M+): H2>20 ppm from baseline within 90 min, CH4>10 ppm any time during the test;

The serum levels of biochemical parameters from laboratory tests and nutrient intake from the 3-day food, were compared among the three SIBO subtypes.

5. Strengths and Limitations

This study had some limitations. Patient were specifically selected based on a new diagnosis of SIBO to determine whether differences could be observed between groups at an early stage of diagnosis. We excluded patients during the antibiotic therapy or the use of recommended elimination diets during treatment to not influence the assessment of patients' conditions. However, it's important to note that some correlations may not have been observed due to the early stage of SIBO detection. The sample size was small, and each subgroup did not have the same number of participants, which could be another reason why the H+/M+ and M+ groups exhibited higher numbers of observed correlations as they were larger groups than H+ group. The 3-day food record and questionnaire was documented by the patients themselves, which may be prone to recall bias, despite the author’s due diligence to clarify cases where doubtful data may have been provided. However, considering these limitations, significant attention was dedicated to the accuracy of conducting breath tests, as SIBO is often over recognized. This research underscores the significant role of assessing both H2 and CH4 gases in patients with SIBO, in order to comprehensively evaluate their nutritional status and dietary habits. This study is also the first to thoroughly assess three types of bacterial overgrowth. When selecting an appropriate therapeutic approach for patients with SIBO, it is paramount to first diagnose the correct type of bacterial overgrowth. This allows for a more targeted treatment plan and addresses the underlying causes in nutritional deficiencies and dietary irregularities.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that the type of SIBO may have varying effects on the nutritional status of patients, leading to a range of deficiencies in the body. Furthermore, the consumption of certain nutrients by patients may result from a particular type of microbial overgrowth, predisposing them to certain gastrointestinal symptoms. Additionally, inadequate or excessive intake of specific foods may predispose the development of a particular type of SIBO. The assessment of nutritional status and dietary habits of patients with SIBO should be a key component of bacterial eradication therapy. Improved nutritional status of patients can lead to greater treatment efficacy and may also contribute to reducing the risk of SIBO recurrence. Often, recurrence arises from focusing solely on the functioning of the small intestine, neglecting the role of the large intestine as a primary contributor to gut microbiota.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization,J.P.W-G and M.E.D; methodology, J.P.W-G software, J.P.W-G.; validation, J.P.W-G.; formal analysis, J.P.W-G.; investigation, J.P.W-G resources, J.P.W-G data curation, J.P.W-G; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.W-G.; writing—review and editing, J.P.W-G and N.D.; visualization, J.P.W-G supervision, M.E.D.; project administration, M.E.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

The study was financially supported by the Polish Ministry of Education and Sciences within funds of the Institute of Human Nutrition Sciences, Warsaw University of Life Sciences (WULS) for scientific research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Human Nutrition and Consumer Science, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Poland (n 13/2021,date 07.05.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study”. Respondents were informed about solely scientific purpose of the study, its anonymity and possibility of resigning from participating in the study at any stage.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported thanks to Unamedica Center in Warsaw. Technical support was given from qualified specialist during the breath testing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Ho, W.T.P.; Liu, C.; Chow, S.K.H.; Ip, M.; Yu, J.; Wong, H.S.; Cheung, W.H.; Sung, J.J.Y.; Wong, R.M.Y. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Bone Homeostasis. Bone Jt. Res. 2021, 10, 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Ogunrinola, G.A.; Oyewale, J.O.; Oshamika, O.O.; Olasehinde, G.I. The Human Microbiome and Its Impacts on Health. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, R.; Inoue, K.Y.; Nishino, K.; Yamasaki, S. Intestinal and Fecal PH in Human Health. Front. Microbiomes 2023, 2, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Avelar Rodriguez, D.; Ryan, P.M.D.; Toro Monjaraz, E.M.; Ramirez Mayans, J.A.; Quigley, E.M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Children: A State-Of-The-Art Review. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Kastl, A.J.; Terry, N.A.; Wu, G.D.; Albenberg, L.G. The Structure and Function of the Human Small Intestinal Microbiota: Current Understanding and Future Directions. Cmgh 2020, 9, 33–45. [CrossRef]

- Ginnebaugh, B.; Chey, W.D.; Saad, R. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: How to Diagnose and Treat (and Then Treat Again). Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2020, 49, 571–587.

- Schlechte, J.; Skalosky, I.; Geuking, M.B.; McDonald, B. Long-Distance Relationships - Regulation of Systemic Host Defense against Infections by the Gut Microbiota. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 809–818. [CrossRef]

- Iacob, S.; Iacob, D.G.; Luminos, L.M. Intestinal Microbiota as a Host Defense Mechanism to Infectious Threats. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Takakura, W.; Pimentel, M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome – An Update. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, A.; Buresi, M.; Lembo, A.; Lin, H.; McCallum, R.; Rao, S.; Schmulson, M.; Valdovinos, M.; Zakko, S.; Pimentel, M. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 775–784. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Rezaie, A. Pros and Cons of Breath Testing for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 19, 140–146.

- Smith, N.W.; Shorten, P.R.; Altermann, E.H.; Roy, N.C.; McNabb, W.C. Hydrogen Cross-Feeders of the Human Gastrointestinal Tract. Gut Microbes 2019, 10, 270–288. [CrossRef]

- Sroka, N., Rydzewska-Rosołowska, A., Kakareko, K., Rosołowski, M., Głowińska, I., Hryszko, T. Show Me What You Have Inside — The Complex Interplay between SIBO and Multiple Medical Conditions — A. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bushyhead, D.; Quigley, E.M.M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth—Pathophysiology and Its Implications for Definition and Management. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 593–607. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Singh, R.; Ro, S.; Ghoshal, U.C. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Underpinning the Symptoms and Pathophysiology. JGH Open 2021, 5, 976–987. [CrossRef]

- Losurdo, G.; Leandro, G.; Ierardi, E.; Perri, F.; Barone, M.; Principi, M.; Di Leo, A. Breath Tests for the Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020, 26, 16–28. [CrossRef]

- Adike, A.; DiBaise, J.K. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Nutritional Implications, Diagnosis, and Management. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2018, 47, 193–208. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Talley, N.J.; Holtmann, G. Current and Future Approaches for Diagnosing Small Intestinal Dysbiosis in Patients With Symptoms of Functional Dyspepsia. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Morrison, M.; Burger, D.; Martin, N.; Rich, J.; Jones, M.; Koloski, N.; Walker, M.M.; Talley, N.J.; Holtmann, G.J. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis: The Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 49, 624–635. [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Shukla, R.; Ghoshal, U. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Bridge between Functional Organic Dichotomy. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 196–208. [CrossRef]

- Losurdo, G.; D’abramo, F.S.; Indellicati, G.; Lillo, C.; Ierardi, E.; Di Leo, A. The Influence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Digestive and Extra-Intestinal Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ierardi, E.; Losurdo, G.; Sorrentino, C.; Giorgio, F.; Rossi, G.; Marinaro, A.; Romagno, K.R.; Di Leo, A.; Principi, M. Macronutrient Intakes in Obese Subjects with or without Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: An Alimentary Survey. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 51, 277–280. [CrossRef]

- Leeming, E.R.; Johnson, A.J.; Spector, T.D.; Roy, C.I.L. Effect of Diet on the Gut Microbiota: Rethinking Intervention Duration. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Ferenc, K.; Sokal-Dembowska, A.; Helma, K.; Motyka, E.; Jarmakiewicz-Czaja, S.; Filip, R. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota by Nutrition and Its Relationship to Epigenetics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Hills, R.D.; Pontefract, B.A.; Mishcon, H.R.; Black, C.A.; Sutton, S.C.; Theberge, C.R. Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1–40. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; Abrouk, M.; Farahnik, B.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, T.H.; et al. Influence of Diet on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Human Health. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.; Rocha, R.; Cotrim, H.P. Diet and Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Is There Evidence? World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 4713–4716. [CrossRef]

- Halmos, E.P.; Power, V.A.; Shepherd, S.J.; Gibson, P.R.; Muir, J.G. A Diet Low in FODMAPs Reduces Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 67-75.e5. [CrossRef]

- Wielgosz-Grochowska, J.P.; Domanski, N.; Drywień, M.E. Efficacy of an Irritable Bowel Syndrome Diet in the Treatment of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Losso, J.N. Food Processing, Dysbiosis, Gastrointestinal Inflammatory Diseases, and Antiangiogenic Functional Foods or Beverages. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 235–258. [CrossRef]

- Staudacher, H.M.; Ralph, F.S.E.; Irving, P.M.; Whelan, K.; Lomer, M.C.E. Nutrient Intake, Diet Quality, and Diet Diversity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and the Impact of the Low FODMAP Diet. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 535–547. [CrossRef]

- Bellini, M.; Tonarelli, S.; Nagy, A.G.; Pancetti, A.; Costa, F.; Ricchiuti, A.; de Bortoli, N.; Mosca, M.; Marchi, S.; Rossi, A. Low FODMAP Diet: Evidence, Doubts, and Hopes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Staudacher, H.M.; Scholz, M.; Lomer, M.C.; Ralph, F.S.; Irving, P.M.; Lindsay, J.O.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.; Whelan, K. Gut Microbiota Associations with Diet in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and the Effect of Low FODMAP Diet and Probiotics. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1861–1870. [CrossRef]

- Wielgosz-Grochowska, J.P.; Domanski, N.; Drywień, M.E. Influence of Body Composition and Specific Anthropometric Parameters on SIBO Type. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Miazga, A.; Osiński, M.; Cichy, W.; Zaba, R. Current Views on the Etiopathogenesis, Clinical Manifestation, Diagnostics, Treatment and Correlation with Other Nosological Entities of SIBO. Adv. Med. Sci. 2015, 60, 118–124. [CrossRef]

- Skrzydło-Radomańska, B.; Cukrowska, B. How to Recognize and Treat Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Z.; Ban, Y.; Wang, B.; Hou, X.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; et al. Application of Methane and Hydrogen-Based Breath Test in the Study of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Intestinal Microbes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 176, 108818. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.A.; Baker, J.R.; Wamsteker, E.J.; Saad, R.; DiMagno, M.J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Is Common in Chronic Pancreatitis and Associates with Diabetes, Chronic Pancreatitis Severity, Low Zinc Levels, and Opiate Use. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 1163–1171. [CrossRef]

- Tauber, M.; Avouac, J.; Benahmed, A.; Barbot, L.; Coustet, B.; Kahan, A.; Allanore, Y. Prevalence and Predictors of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Systemic Sclerosis Patients with Gastrointestinal Symptoms. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2014, 32, 5–10.

- Kubota, Y.; Nagano, H.; Ishii, K.; Kono, T.; Kono, S.; Akita, S.; Mitsukawa, N.; Tanaka, T. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth as a Cause of Protracted Wound Healing and Vitamin D Deficiency in a Spinal Cord Injured Patient with a Sacral Pressure Sore: A Case Report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Stotzer, P.O.; Johansson, C.; Mellström, D.; Lindstedt, G.; Kilander, A.F. Bone Mineral Density in Patients with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003, 50, 1415–1418.

- Daru, J.; Allotey, J.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Khan, K.S. Serum Ferritin Thresholds for the Diagnosis of Iron Deficiency in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Transfus. Med. 2017, 27, 167–174. [CrossRef]

- Bohm, M.; Shin, A.; Teagarden, S.; Xu, H.; Gupta, A.; Siwiec, R.; Nelson, D.; Wo, J.M. Risk Factors Associated with Upper Aerodigestive Tract or Coliform Bacterial Overgrowth of the Small Intestine in Symptomatic Patients. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 54, 150–157. [CrossRef]

- Rosell-Díaz, M.; Santos-González, E.; Motger-Albertí, A.; Ramió-Torrentà, L.; Garre-Olmo, J.; Pérez-Brocal, V.; Moya, A.; Jové, M.; Pamplona, R.; Puig, J.; et al. Gut Microbiota Links to Serum Ferritin and Cognition. Gut Microbes 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bloor, S.R.; Schutte, R.; Hobson, A.R. Oral Iron Supplementation—Gastrointestinal Side Effects and the Impact on the Gut Microbiota. Microbiol. Res. (Pavia). 2021, 12, 491–502. [CrossRef]

- Platovsky, A.; Tokayer, A. Folate Levels in Patients With Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, S530. [CrossRef]

- Marie, I.; Ducrotté, P.; Denis, P.; Menard, J.F.; Levesque, H. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Systemic Sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009, 48, 1314–1319. [CrossRef]

- Kaniel, O.; Sherf-Dagan, S.; Szold, A.; Langer, P.; Khalfin, B.; Kessler, Y.; Raziel, A.; Sakran, N.; Motro, Y.; Goitein, D.; et al. The Effects of One Anastomosis Gastric Bypass Surgery on the Gastrointestinal Tract. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Achufusi, T.G.O.; Sharma, A.; Zamora, E.A.; Manocha, D. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment Methods. Cureus 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Quigley, E.M.M.; Murray, J.A.; Pimentel, M. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1526–1532. [CrossRef]

- Zaidel, O.; Lin, H.C. Uninvited Guests: The Impact of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth on Nutritional Status. Pract. Gastroenterol. 2003, 27, 27-30+33.

- Kok, D.E.; Steegenga, W.T.; Smid, E.J.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Ulrich, C.M.; Kampman, E. Bacterial Folate Biosynthesis and Colorectal Cancer Risk: More than Just a Gut Feeling. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 244–256. [CrossRef]

- Engevik, M.A.; Morra, C.N.; Röth, D.; Engevik, K.; Spinler, J.K.; Devaraj, S.; Crawford, S.E.; Estes, M.K.; Kalkum, M.; Versalovic, J. Microbial Metabolic Capacity for Intestinal Folate Production and Modulation of Host Folate Receptors. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Madigan, K.E.; Bundy, R.; Weinberg, R.B. Distinctive Clinical Correlates of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth with Methanogens. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1598-1605.e2. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Arango, L.F.; Barrett, H.L.; McIntyre, H.D.; Callaway, L.K.; Morrison, M.; Nitert, M.D. Contributions of the Maternal Oral and Gut Microbiome to Placental Microbial Colonization in Overweight and Obese Pregnant Women. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Desai, M. S., Seekatz, A. M., Koropatkin, N. M., Kamada, N., Hickey, C. A., Wolter, M., Pudlo, N. A., Kitamoto, S., Terrapon, N., Muller, A., Young, V. B., Henrissat, B., Wilmes, P., Stappenbeck, T. S., Núñez, G., & Martens, E.C. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell 2016, 5, 1339–1353, doi:110.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043.

- Fu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W. Dietary Fiber Intake and Gut Microbiota in Human Health. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Parlesak, A.; Klein, B.; Schecher, K.; Bode, J.C.; Bode, C. Prevalence of Small Bowel Bacterial Overgrowth and Its Association with Nutrition Intake in Nonhospitalized Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 768–773. [CrossRef]

- Cortez, A.P.B.; Fisberg, M.; Morais, M.B. de Macronutrient Intakes in Overweight Adolescents with or without Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 228–229. [CrossRef]

- Saffouri, G.B.; Shields-Cutler, R.R.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Lekatz, H.R.; Hale, V.L.; Cho, J.M.; Battaglioli, E.J.; Bhattarai, Y.; Thompson, K.J.; et al. Small Intestinal Microbial Dysbiosis Underlies Symptoms Associated with Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Jo, I.H.; Paik, C.-N.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, J.M.; Choi, S.Y.; Hong, K.P. Lactase Deficiency Diagnosed by Endoscopic Biopsy-Based Method Is Associated With Positivity to Glucose Breath Test. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2023, 29, 85–93. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.A.; Kim, R.; Stoita, A.; Mciver, C.J.; Kurtovic, J.; Riordan, S.M. Lactose Malabsorption in the Elderly: Role of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 43, 146–154. [CrossRef]

- Perets, T.T.; Hamouda, D.; Layfer, O.; Ashorov, O.; Boltin, D.; Levy, S.; Niv, Y.; Dickman, R. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth May Increase the Likelihood of Lactose and Sorbitol but Not Fructose Intolerance False Positive Diagnosis. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2017, 47, 447–451.

- Enko, D.; Rezanka, E.; Stolba, R.; Halwachs-Baumann, G. Lactose Malabsorption Testing in Daily Clinical Practice: A Critical Retrospective Analysis and Comparison of the Hydrogen/Methane Breath Test and Genetic Test (C/T-13910 Polymorphism) Results. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Scanu, A.M.; Bull, T.J.; Cannas, S.; Sanderson, J.D.; Sechi, L.A.; Dettori, G.; Zanetti, S.; Hermon-Taylor, J. Mycobacterium Avium Subspecies Paratuberculosis Infection in Cases of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Comparison with Crohn’s Disease and Johne’s Disease: Common Neural and Immune Pathogenicities. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 3883–3890. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Misselwitz, B.; Dai, N.; Fox, M. Lactose Intolerance in Adults: Biological Mechanism and Dietary Management. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8020–8035. [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.; Kim, G.; Morales, W.; Sung, J.; Rooks, E.; Pokkunuri, V.; Weitsman, S.; Barlow, G.M.; Chang, C.; Pimentel, M. Intestinal Methanobrevibacter Smithii but Not Total Bacteria Is Related to Diet-Induced Weight Gain in Rats. Obesity 2013, 21, 748–754. [CrossRef]

- Agah, S.; Aminianfar, A.; Keshteli, A.H.; Bitarafan, V.; Adibi, P.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Feinle-Bisset, C. Association between Dietary Macronutrient Intake and Symptoms in Uninvestigated Dyspepsia: Evidence from a Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Herdiana, Y. Functional Food in Relation to Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Duncanson, K.R.; Talley, N.J.; Walker, M.M.; Burrows, T.L. Food and Functional Dyspepsia: A Systematic Review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 390–407. [CrossRef]

- Cinquanta, L.; Fontana, D.E.; Bizzaro, N. Chemiluminescent Immunoassay Technology: What Does It Change in Autoantibody Detection? Autoimmun. Highlights 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Proskurnin, M.; Samarina, T. Rapid Assessment of Iron in Blood Plasma and Serum by Spectrophotometry with Cloud-Point Extraction. F1000Research 2015, 4, 2–7. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Uricoechea, H.; Nogueira, J.P.; Pinzón-Fernández, M. V.; Agredo-Delgado, V.; Vargas-Sierra, H.D. Population Status of Vitamin B12 Values in the General Population and in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes, in Southwestern Colombia. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Elgormus, Y.; Okuyan, O.; Dumur, S.; Sayili, U.; Uzun, H. The Epidemiology of Deficiency of Vitamin B12 in Preschool Children in Turkey. Med. 2023, 59, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.J.; Cook, J.R.; Rothberg, M.B. Clinical Utility of Folic Acid Testing for Patients with Anemia or Dementia. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 824–826. [CrossRef]

- Koulaouzidis, A.; Cottier, R.; Bhat, S.; Said, E.; Linaker, B.D.; Saeed, A.A. A Ferritin Level > 50 Μg/L Is Frequently Consistent with Iron Deficiency. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 20, 168–170. [CrossRef]

- Breymann, C.; Römer, T.; Dudenhausen, J.W. Treatment of Iron Deficiency in Women. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2013, 73, 256–261. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Gómez-Ramírez, S.; Besser, M.; Pavía, J.; Gomollón, F.; Liumbruno, G.M.; Bhandari, S.; Cladellas, M.; Shander, A.; Auerbach, M. Current Misconceptions in Diagnosis and Management of Iron Deficiency. Blood Transfus. 2017, 15, 422–437. [CrossRef]

- Girelli, D.; Ugolini, S.; Busti, F.; Marchi, G.; Castagna, A. Modern Iron Replacement Therapy: Clinical and Pathophysiological Insights. Int. J. Hematol. 2018, 107, 16–30. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Knovich, M.A.; Coffman, L.G.; Torti, F.M.; Torti, S. V. Serum Ferritin: Past, Present and Future. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj. 2010, 1800, 760–769. [CrossRef]

- Szponar, L.; Wolnicka, K.; Rychlik, E. Album Fotografii Produktów i Potraw /Album of Photographs of Food Products and Dishes; 2000; ISBN 8386060514.

- Wojtasik, A.; Woźniak, A.; Stoś, K.; Jarosz, M. Normy Żywienia Dla Populacji Polski i Ich Zastosowanie; 2020; ISBN 9788365870285.

- Johansson, G.; Westerterp, K.R. Assessment of the Physical Activity Level with Two Questions: Validation with Doubly Labeled Water. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1031–1033. [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The Importance of the Ratio of Omega-6/Omega-3 Essential Fatty Acids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2002, 56, 365–379. [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P.; DiNicolantonio, J.J. The Importance of a Balanced ω-6 to ω-3 Ratio in the Prevention and Management of Obesity. Open Hear. 2016, 3, 1–6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).