1. Introduction

The spread and persistence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) remains to be a global health threat, a review article on AMR estimated that approximately 10 million people will die annually due to AMR related cases by the year 2050 if this problem is not addressed[

1,

2]. The environment can be contaminated by pathogenic bacteria and AMR encoding genes from clinical waste turning it into a reservoir for future exogenous infections which significantly contributes to this problem[

3,

4].

Healthcare settings and teachings institutions that have a microbiology laboratory often produce infectious wastes ranging from infectious clinical samples to bacterial cultures. These wastes are often treated before disposal by autoclaving at 121°C and 0.1 MPa for 30 minutes which ensures the total killing of most bacterial pathogen, thereafter; the autoclaved waste is discarded into the municipal sanitary sewage system for further treatment and recycling[

5,

6,

7]. Poor handling and disposal of microbiological wastes poses a risk of introducing AMR encoding genes and pathogens into the environment via the wastewater/sewage water system(s)[

8,

9].

Within the environment free naked AMR encoding genes from killed clinical isolates can be transferred to environmental bacteria via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) mechanisms such as conjugation, transformation, and transduction. The amplification of AMR in environmental bacteria niches intensifies the global burden of AMR, as it can be a reservoir for exogenous infections by multi drug resistant (MDR) bacteria which are often deadly and costly[

10,

11,

12].

Autoclaving is a practice employed by microbiology laboratories and hospitals for the treatment of microbiological waste(s) before disposal. However, the stability status of AMR encoding genes (DNA fragments) carried by these pathogens is not well understood which poses a risk of introducing viable AMR genes from clinical pathogens into the environment which can later be assimilated by environmental bacteria leading to the propagation of AMR burden. This information is crucial to inform the effective public health interventions and environmental policies. Therefore, this study was designed to determine the stability/integrity status of AMR encoding genes following autoclaving of the microbiological waste in Mwanza, Tanzania.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design, Duration and Setting

This was a laboratory based experimental study conducted between May and July of 2024 at the microbiology and immunology research laboratory of the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences (CUHAS).

Study Population and Data Collection

This study used fresh cultured wild type E. coli (ATCC 25922) control strains and in-house prepared extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli carrying blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes which were available and stored at -80℃ at the CUHAS microbiology laboratory. The E. coli samples were then aliquoted into 18 parts each (for E. coli ATCC 25922 and ESBL E. coli) using cryovial tubes before autoclaving. A research book was used to record experimental information such as temperature, autoclaving time and all other laboratory procedures.

Recovery of Bacteria Isolates, Autoclaving and PCR Amplification

E.coli ATCC 25922 and E. coli carrying blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes were retrieved out of -80°C, the vials were then left for 30 minutes at room temperature so as to allow thawing, thereafter; the isolates were sub-cultured onto MacConkey agar (OXOID, Hampshire, United Kingdom) supplemented with 2μg cefotaxime (MCA-C) for ESBL E. coli while the wild-type E. coli was sub-cultured onto plain MCA and incubated at 35-37℃ for 18-24 hours to obtain pure fresh colonies.

A loopful (10μl) of fresh pure cultured E. coli ATCC 25922 and E. coli (carrying blaCTX-M and blaTEM) genes was obtained and transferred into two separate vials containing sterile normal saline to form a suspension (this process was repeated for 18 times for each isolate). Each aliquot was then subjected to autoclaving at a temperature and pressure settings of 121°C and 0.1 MPa (1 bar) respectively, for 5, 10 ,15, 20, 25 and 30 minutes respectively using a commercial autoclave (YX-18LM-50A; Shanghai Boxun Medical Biological Instrument Corp., China). The experiment was repeated 3 times. Each autoclaved vial was then subjected to centrifugation at 13200 revolution per minute (rpm) for 10 minutes followed by supernatant retrieval for PCR analysis.

PCR Amplification and Detection of ESBL Genes

Multiplex PCR assay was used for detection of ESBL genes: blaCTX-M and blaTEM. Briefly, 2 µL of each DNA sample was amplified in a 25 µL reaction PCR Eppendorf tube containing HotStarTaq® DNA polymerase master mix (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and each primer at a reaction concentration of 200nM, the primer sequence, melting temperature and amplicon size have been indicated in (

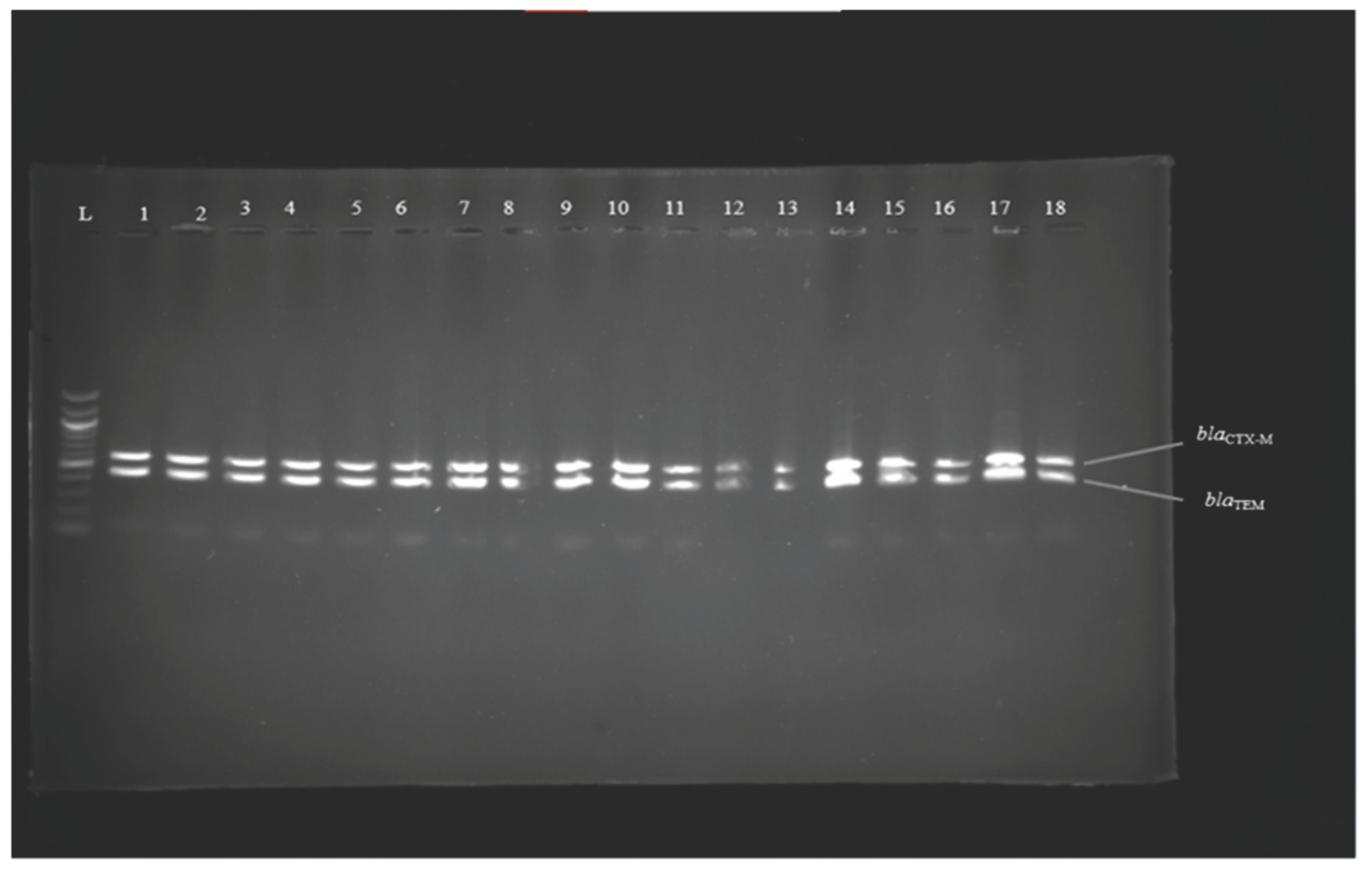

Table 1) below. PCR reactions were carried out in thermal cycler machine (T100™, BIO-RAD, Kaki-Bukit, Singapore) which was conditioned at: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 mins; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 40 sec, annealing at 58 °C for 40 sec, and extension at 68 °C for 2 mins; and a final extension at 68 °C for 10 mins. PCR amplicons were separated by the electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel with SYBR Safe dye and visualized under UV light.

Autoclaved wastes were left to cool at room temperature for 15-20 minutes followed by inoculation onto MCA which were incubated at 35-37℃ for 18-24 hours, this was done to assess the post autoclave viability of bacteria which was confirmed by observing the growth of lactose fermenting colonies.

Quality Control

Autoclave tape (Alpine Dental Inc ,NY, USA) was used to control autoclave performance by observing the formation of black stripes on the tape after each session. For multiplex PCR assay, internal quality control was performed by running each DNA sample in duplicates and for external quality control, in-house prepared E. coli (carrying blaCTX-M and blaTEM) genes) and DNA free water were used as a positive and negative control respectively.

3. Results

Viability and Stability Status of Bacteria and ARG’s After Autoclaving

A total of 18 experiments were performed in this study to check the stability status of ARG’s namely bla

CTX-M and bla

TEM harbored by

E. coli. All autoclaved

E. coli were killed as they did not grow after being subcultured onto MCA, however; bla

CTX-M and bla

TEM DNA fragments were still stable at the end of each autoclave session regardless of autoclaving time as they were amplified and detected by multiplex PCR,

Table 2 &

Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Image 1 Results of multiplex PCR amplification of genes blaCTX-M (593 bp) and blaTEM (445 bp) lanes; 1 to 18 = DNA samples of autoclaved E. coli resistant strains; L = 100 bp DNA ladder.

Figure 1.

Image 1 Results of multiplex PCR amplification of genes blaCTX-M (593 bp) and blaTEM (445 bp) lanes; 1 to 18 = DNA samples of autoclaved E. coli resistant strains; L = 100 bp DNA ladder.

4. Discussion

This study utilized multiplex PCR to assess the integrity of DNA fragments of bla

CTX-M and bla

TEM genes after being autoclaved at different exposure times. The findings of this study showed that the DNA fragments of bla

CTX-M and bla

TEM genes maintained their integrity despite being exposed to prolonged autoclaving time confirming that ARG’s are not completely destroyed following autoclaving. The findings are of critical concern about the potential risk of contaminating the environment once the waste is discarded into municipal sewage systems and therefore acting as an ARG’s hotspot[

11]. Our study findings are in agreement with those by Franco et al, 2020 who documented the persistence of DNA fragments from cell cultures despite being autoclaved for up to 30 minutes at 121℃ and at a pressure of 1.1 atm[

15].

Autoclaving is widely regarded as a robust method for sterilizing microbiological waste [

16], this was evident in this study where all

E. coli were completely killed after being autoclaved. However, its effectiveness in degrading genetic material, such as plasmid-encoded ARG’s, has not been well-documented. This study showed that although autoclaving killed all bacterial cells, residual genetic material, including bla

CTX-M and bla

TEM, were still detected in the treated microbiological waste. Their persistence in sewage waste streams poses a risk for horizontal gene transfer (HGT) to other bacterial populations present in municipal sewage systems and in turn escalates the burden of AMR in the environment[

11,

17].

This study highlights the importance of re-evaluating current bio-safety protocols, especially in laboratories and healthcare settings where large volumes of microbiological waste are generated. The persistence of ARGs like blaCTX-M and blaTEM in autoclaved waste presents potential public health risk if such waste is not appropriately treated before being released into municipal sewage systems. Future research should focus on assessing the efficacy of alternative or additional treatments for complete eradication of ARGs in autoclaved waste and evaluating the environmental impact of these genes in Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) and downstream the ecosystems.

This study did not assess if the plasmids remain intact following autoclaving, this can be an area of focus for future studies so as to unmask the true burden and potential risk of ARG’s persistence in the microbiological waste.

5. Conclusions

Autoclaving achieved total killing of bacteria, however, failed to destroy the stability/integrity of ARG’s DNA fragments in the microbiological waste. We recommend enhancement of waste treatment strategies that go beyond microbial inactivation so as to address the persistence of ARGs in autoclaved waste so as to mitigate their contribution to the global AMR crisis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on Preprints.org,

Figure 1: Results of multiplex PCR amplification of genes bla

CTX-M (593 bp) and bla

TEM (445 bp); Table S1: Viability status of bacteria and ARG’s at different autoclave times.

Author Contributions

JR, AC, VS, and SEM conceived, designed and executed the study; AS, JR, PD and VS collected the data ; JR, VS, and PD performed the laboratory analysis; JR wrote the manuscript, which was critically reviewed by all the authors.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study obtained an ethical clearance from the joint CUHAS/BMC Research Ethics and review committee with clearance number (CREC 3012/2024). Permission to conduct the study was obtained from CUHAS microbiology and immunology laboratory authorities.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are fully included in this manuscript. No additional datasets were generated or analyzed beyond what is presented herein.

Acknowledgments

We thank the CUHAS Microbiology and Immunology department for their support and technical assistance during data collection. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they had no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR |

Antimicrobial Resistance |

| ARGs |

Antimicrobial Resistance Genes |

| CTX-M |

Cefotaxime-Munich |

| CUHAS |

Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ESBL |

Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase |

| HGT |

Horizontal Gene Transfer |

| MCA |

MacConkey Agar |

| MCA-C |

MacConkey Agar-Cefotaxime |

| MDR |

Multi Drug Resistance |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RPM |

Revolutions per minute |

| SHV |

Sulfhydryl variable |

| TEM |

Temoneira |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- O’Neill J: Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. 2016.

- Aljeldah MM: Antimicrobial resistance and its spread is a global threat. Antibiotics 2022, 11(8):1082.

- Fouz N, Pangesti KN, Yasir M, Al-Malki AL, Azhar EI, Hill-Cawthorne GA, Abd El Ghany M: The contribution of wastewater to the transmission of antimicrobial resistance in the environment: implications of mass gathering settings. Tropical medicine and infectious disease 2020, 5(1):33.

- Despotovic M, de Nies L, Busi SB, Wilmes P: Reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance in the context of One Health. Current opinion in microbiology 2023, 73:102291.

- Hossain MS, Balakrishnan V, Rahman NNNA, Sarker MZI, Kadir MOA: Treatment of clinical solid waste using a steam autoclave as a possible alternative technology to incineration. International journal of environmental research and public health 2012, 9(3):855-867.

- Garibaldi BT, Reimers M, Ernst N, Bova G, Nowakowski E, Bukowski J, Ellis BC, Smith C, Sauer L, Dionne K: Validation of autoclave protocols for successful decontamination of category a medical waste generated from care of patients with serious communicable diseases. Journal of clinical microbiology 2017, 55(2):545-551. [CrossRef]

- Biological Waste Management [https://ehs.oregonstate.edu/biological-waste-management].

- Harris S, Morris C, Morris D, Cormican M, Cummins E: Antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli in the municipal wastewater system: effect of hospital effluent and environmental fate. Science of the total environment 2014, 468:1078-1085. [CrossRef]

- Marschang S, de Stefani E: Waste disposal in healthcare and effects on AMR.

- Liu G, Thomsen LE, Olsen JE: Antimicrobial-induced horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes in bacteria: A mini-review. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2022, 77(3):556-567. [CrossRef]

- Lerminiaux NA, Cameron AD: Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in clinical environments. Canadian journal of microbiology 2019, 65(1):34-44.

- Cosgrove SE: The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2006, 42(Supplement_2):S82-S89.

- Monstein HJ, Östholm-Balkhed Å, Nilsson M, Nilsson M, Dornbusch K, Nilsson L: Multiplex PCR amplification assay for the detection of blaSHV, blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes in Enterobacteriaceae. Apmis 2007, 115(12):1400-1408.

- Boyd DA, Tyler S, Christianson S, McGeer A, Muller MP, Willey BM, Bryce E, Gardam M, Nordmann P, Mulvey MR: Complete nucleotide sequence of a 92-kilobase plasmid harboring the CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase involved in an outbreak in long-term-care facilities in Toronto, Canada. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2004, 48(10):3758-3764. [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Franco D, Lin Q, Van Loosdrecht MC, Abbas B, Weissbrodt DG: Anticipating xenogenic pollution at the source: impact of sterilizations on DNA release from microbial cultures. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2020, 8:171. [CrossRef]

- Harjanti DW, Wahyono F, Ciptaningtyas VR: Effects of different sterilization methods of herbal formula on phytochemical compounds and antibacterial activity against mastitis-causing bacteria. Veterinary world 2020, 13(6):1187. [CrossRef]

- Von Wintersdorff CJ, Penders J, Van Niekerk JM, Mills ND, Majumder S, Van Alphen LB, Savelkoul PH, Wolffs PF: Dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in microbial ecosystems through horizontal gene transfer. Frontiers in microbiology 2016, 7:173.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).