Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

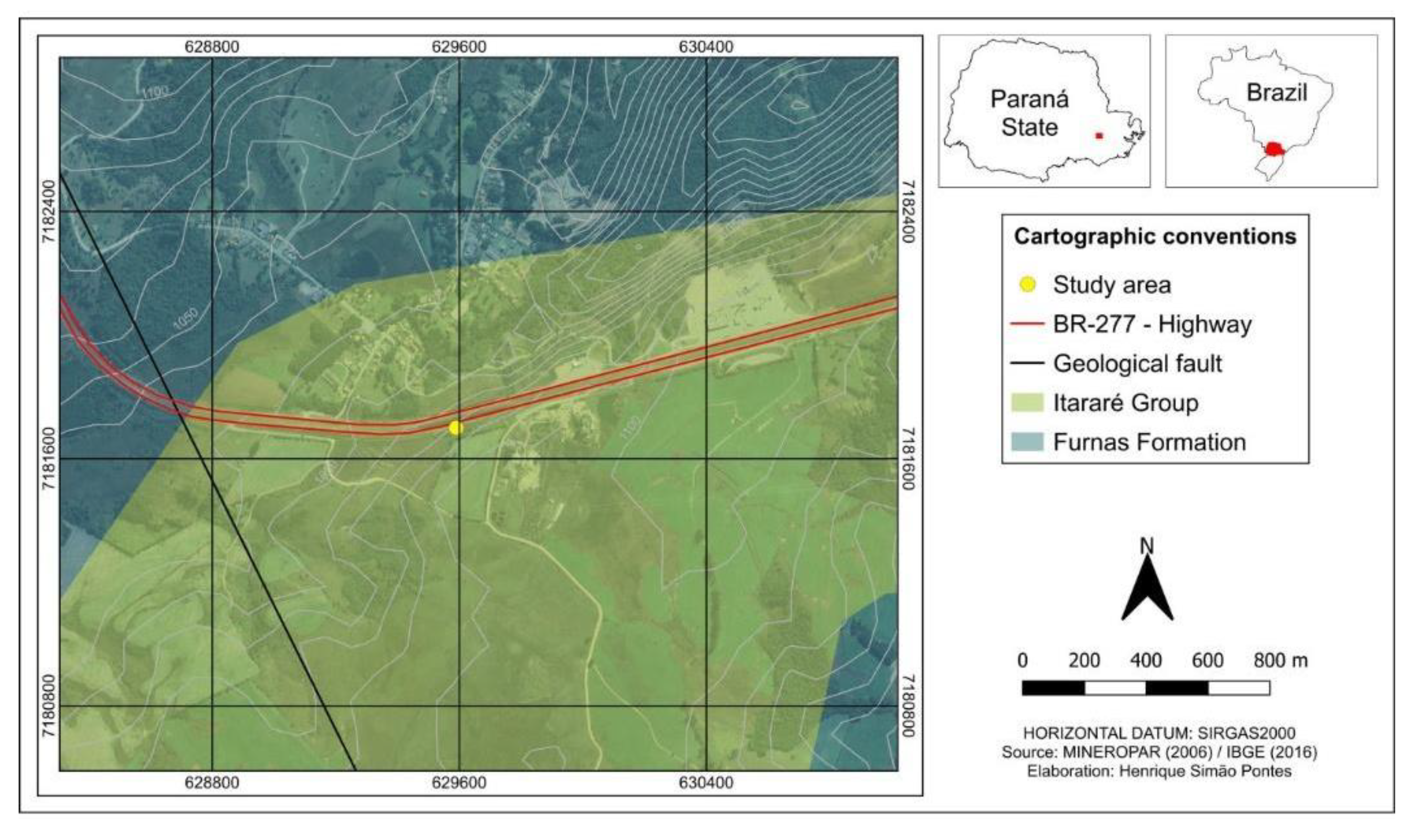

2.1. Study Area, Site Selection and Rocky Sampling

2.2. Chemical Composition of the Samples

2.3. Radiation Shielding Parameters

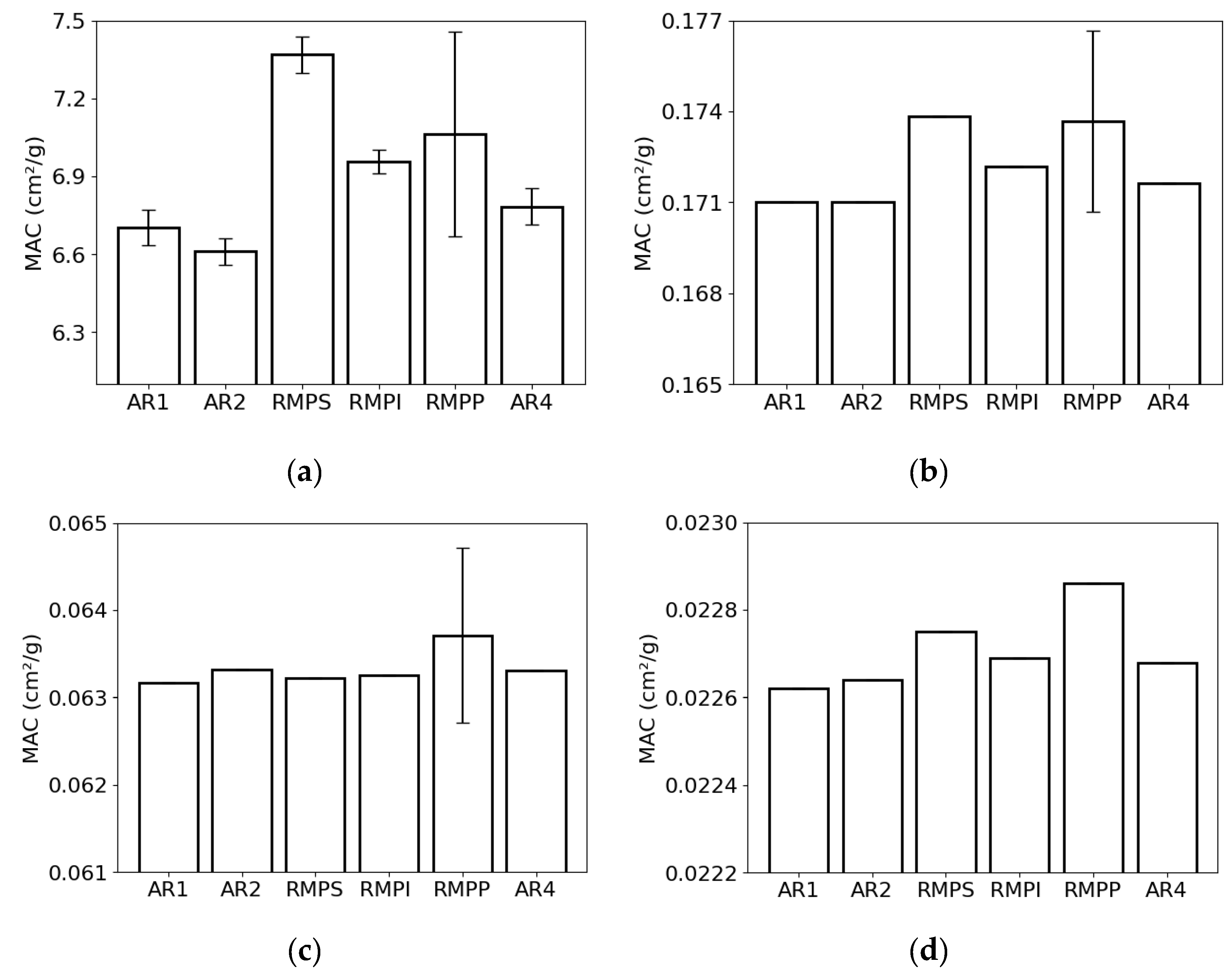

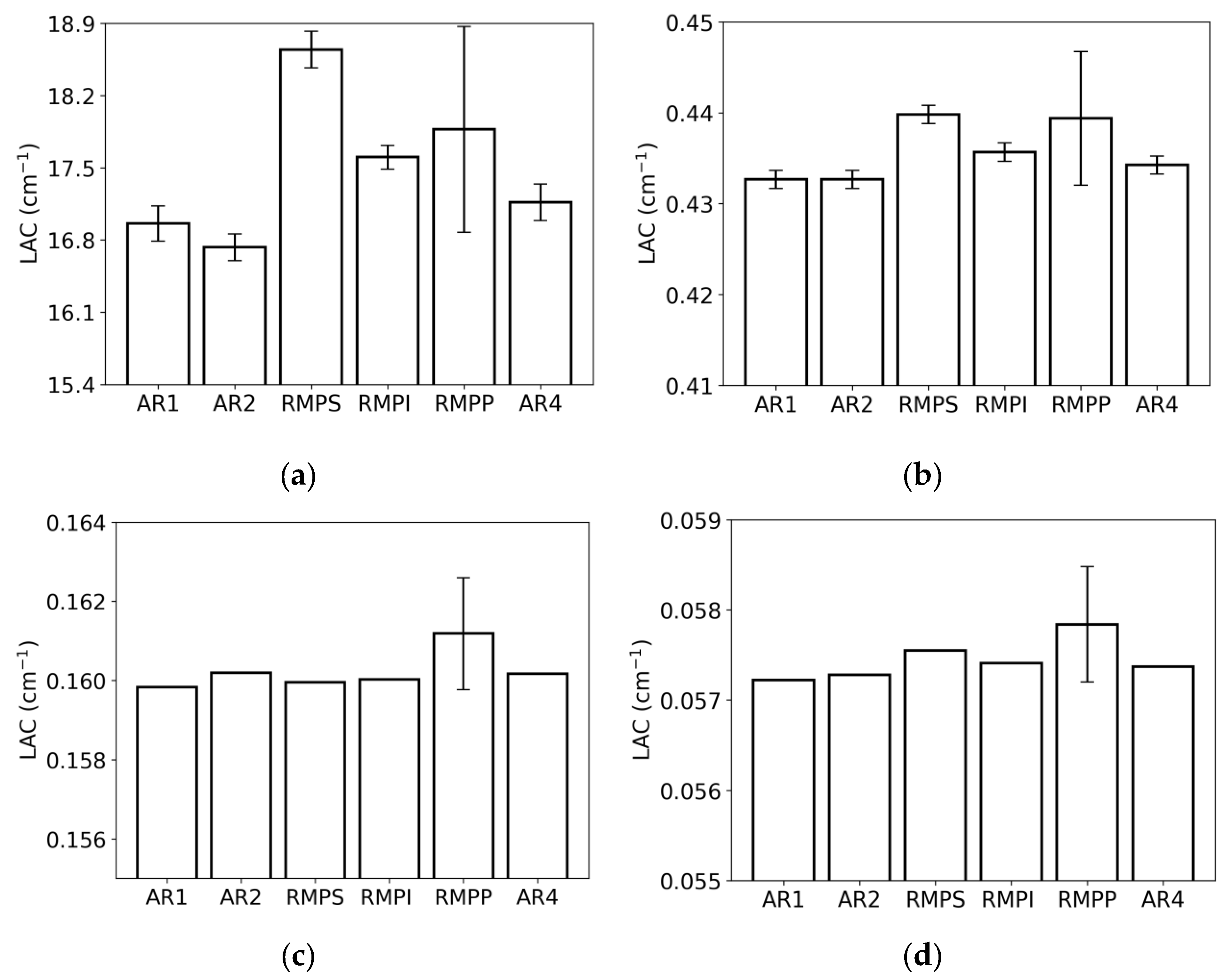

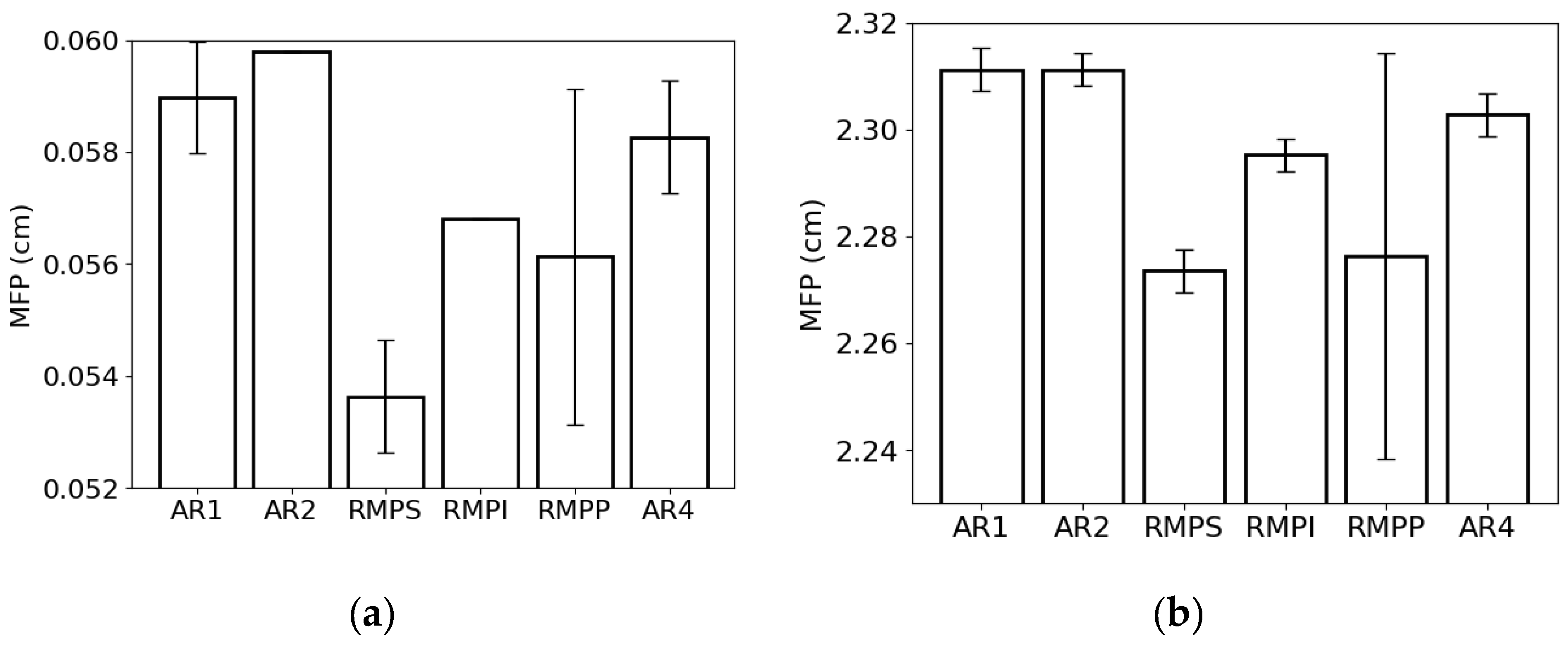

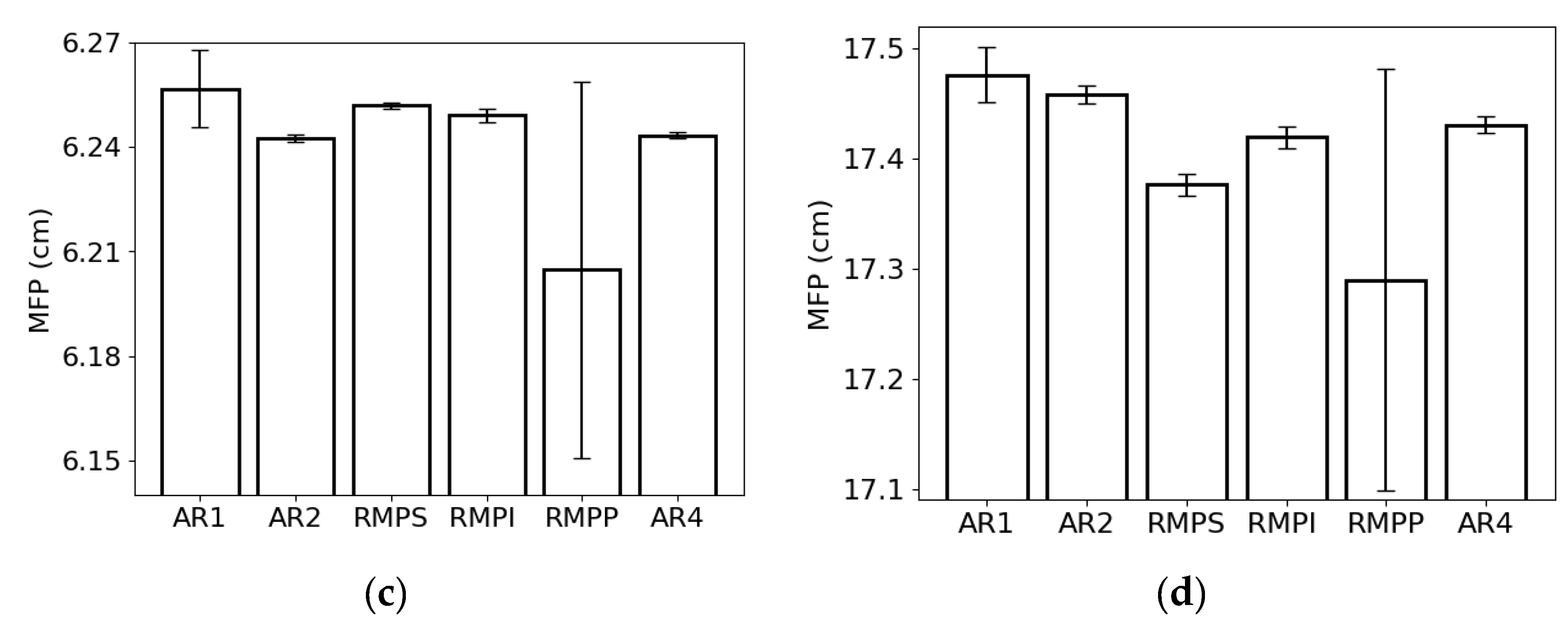

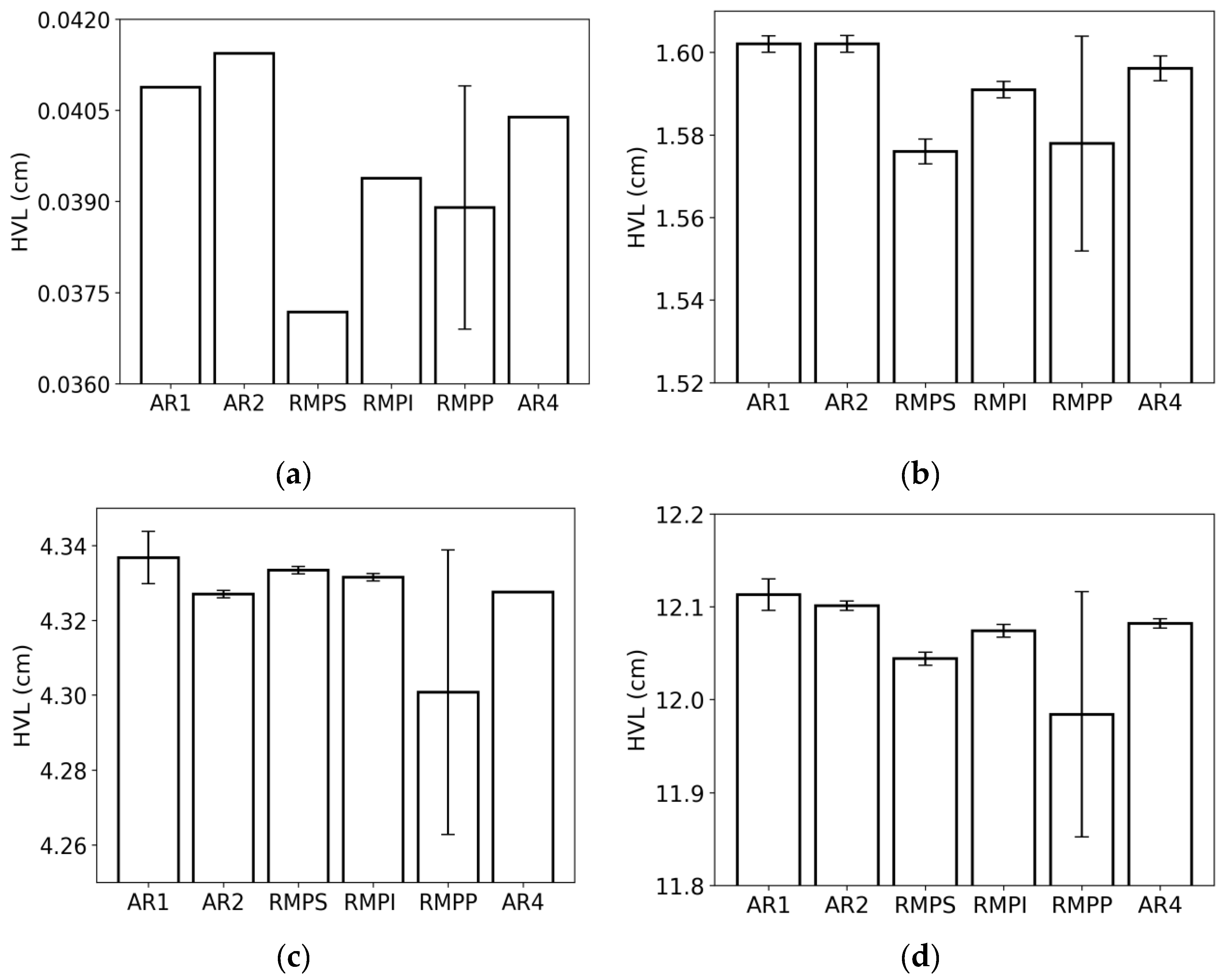

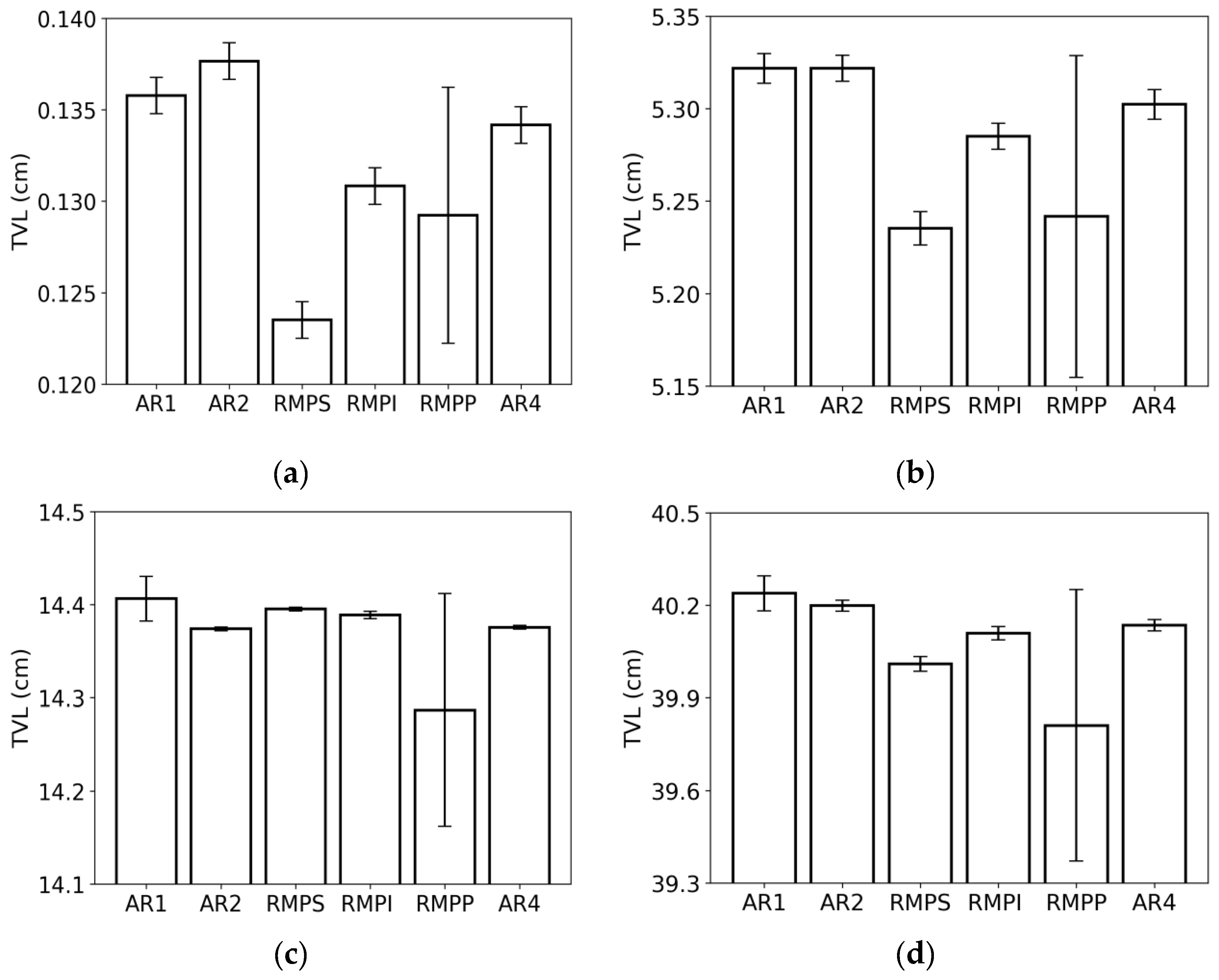

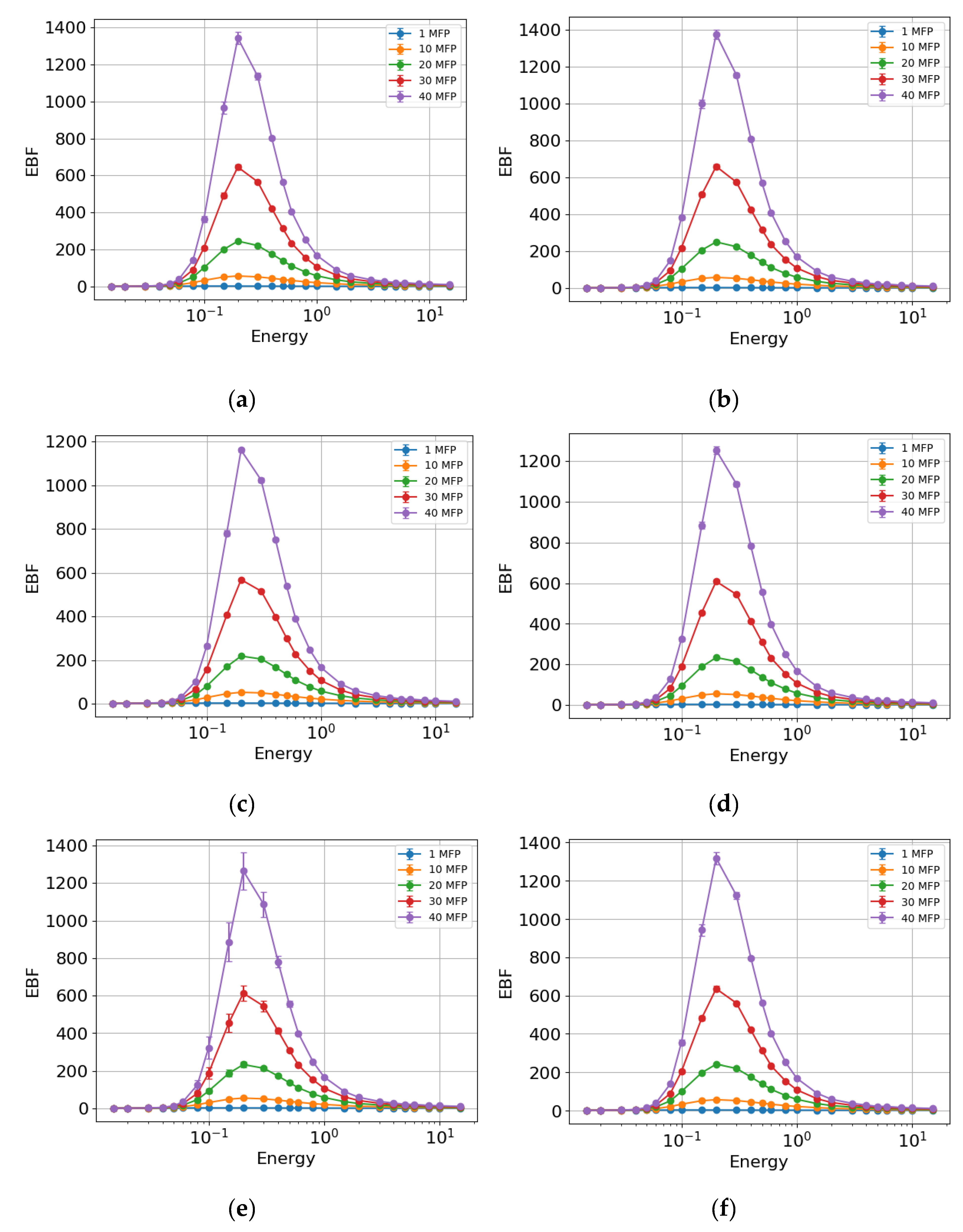

3. Results

| Sample | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | K2O | SO3 | TiO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR1 | 67.330.00 | 27.770.00 | 2.500.00 | 1.230.00 | 0.620.00 | 0.510.00 |

| AR2 | 72.150.02 | 24.220.01 | 2.480.00 | 0.390.00 | 0.590.00 | 0.650.00 |

| RMPS | 66.560.01 | 26.690.02 | 3.940.00 | 1.750.00 | 0.730.00 | 0.540.00 |

| RMPI | 67.980.00 | 26.950.00 | 2.830.00 | 1.710.00 | - | 0.410.00 |

| RMPP | 68.480.01 | 26.300.01 | 2.370.01 | 1.740.00 | 0.640.00 | 0.480.00 |

| AR4 | 73.230.01 | 22.530.01 | 2.600.00 | 1.140.00 | 0.430.00 | 0.480.00 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arif Sazali, M.; Alang Md Rashid, N.K.; Hamzah, K. A Review on Multilayer Radiation Shielding. IOP Conf. Ser. : Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 555, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, C.V.; Alsayed, Z.; Badawi, M.S.; Thabet, A.A.; Pawar, P.P. Polymeric composite materials for radiation shielding: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2057–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onaizi, A.M.; Amran, M.; Tang, W.; Betoush, N.; Alhassan, M.; Rashid, R.S.; Onaizi, S.A. Radiation-shielding concrete: A review of materials, performance, and the impact of radiation on concrete properties. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, A.E.S.; Ali, M.A.M.; Ismail, M.R. Natural fibre high-density polyethylene and lead oxide composites for radiation shielding. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2003, 66, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioro, L.S.; Sadovskiy, B.F.; Pioro, I.L. Research and development of a high-efficiency one-stage melting converter-burial-bunker method for vitrification of high-level radioactive wastes. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2001, 205, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Buriahi, M.S.; Sayyed, M.I.; Bantan, R.A.; Al-Hadeethi, Y. Nuclear radiation shielding characteristics of some natural rocks by using EPICS2017 library. Materials 2021, 14, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, M.A.; El-Khayatt, A.M.; Shahien, M.G.; Bakhit, B.R.; Suliman, I.I.; Zayed, A.M. Radiation Attenuation Assessment of Serpentinite Rocks from a Geological Perspective. Toxics 2022, 10, 697–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J. Study on Shielding and Radiation Resistance of Basalt Fiber to Gamma Ray. Materials 2022, 15, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.A.H.; Rashid, R.S.M.; Amran, M.; Hejazii, F.; Azreen, N.M.; Fediuk, R.; Voo, Y.L.; Vatin, N.I.; Idris, M.I. Recent Trends in Advanced Radiation Shielding Concrete for Construction of Facilities: Materials and Properties. Polymers 2022, 14, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarloo, B.; Lehner, P.; Bakhtiari Doost, R. Mechanical Properties and Gamma Radiation Transmission Rate of Heavyweight Concrete Containing Barite Aggregates. Materials 2022, 15, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, E.; Mesbahi, A.; Malekzadeh, R.; Mansouri, A. Shielding Characteristics of Nanocomposites for Protection against X- and Gamma Rays in Medical Applications: Effect of Particle Size, Photon Energy and Nano-Particle Concentration. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2020, 59, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çelen, Y.Y.; Akkurt, I.; Ceylan, Y.; Atçeken, H. Application of Experiment and Simulation to Estimate Radiation Shielding Capacity of Various Rocks. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhat, M.E.; Demir, N.; Akar Tarim, U.; Gurler, O. Calculation of Gamma-Ray Mass Attenuation Coefficients of Some Egyptian Soil Samples Using Monte Carlo Methods. Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids 2014, 169, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, F.; Kaçal, M.R.; Sayyed, M.I.; Karataş, H.A. Study of Gamma Radiation Attenuation Properties of Some Selected Ternary Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 782, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, M.I.; AlZaatreh, M.Y.; Dong, M.G.; Zaid, M.H.M.; Matori, K.A.; Tekin, H.O. A Comprehensive Study of the Energy Absorption and Exposure Buildup Factors of Different Bricks for Gamma-Rays Shielding. Results Phys. 2017, 7, 2528–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, F.F.; Delgado, D.; Spisila, A.L.; Brumatti, M. Divisão Litoestratigráfica Do Grupo Itararé No Estado Do Paraná. Bol. Parana. De Geociências 2021, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, I.S.; Pontes, H.S.; Ribeiro, A.G. Classificação e fatores condicionantes dos movimentos de massa em taludes de corte na BR 277- Balsa Nova, Paraná. Rev. SODEBRAS 2023, 18, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şakar, E.; Özpolat, Ö.F.; Alım, B.; Sayyed, M.I.; Kurudirek, M. Phy-X / PSD: Development of a User Friendly Online Software for Calculation of Parameters Relevant to Radiation Shielding and Dosimetry. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2020, 166, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cai, X.; Chen, L.; Cao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, L. Influence of Cyclic Wetting and Drying on Physical and Dynamic Compressive Properties of Sandstone. Eng. Geol. 2017, 220, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.F.O.; Stael, G.C.; Azeredo, R.B.; Ade, M.V.B.; Bergamaschi, S.; Lourenço, J.; Bermudez, S.L.B. Petrographic and Petrophysical Characterization of Sandstones from Rio Bonito Formation, Paraná Basin (Southern Brazil). An. Da Acad. Bras. De Ciências 2024, 96, e20240365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, A.; Archer, J.S. Sandstone Reservoir Description: An Overview of the Role of Geology and Mineralogy. Clay Miner. 1986, 21, 791–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Chen, K.; Hayatdavoudi, A.; Sawant, K.; Lomas, M. Effects of Clay Content, Cement and Mineral Composition Characteristics on Sandstone Rock Strength and Deformability Behaviors. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 176, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, M.; Alexandrowicz, Z.; Rzepa, G. Composition of Weathering Crusts on Sandstones from Natural Outcrops and Architectonic Elements in an Urban Environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014, 21, 14023–14036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Stattegger, K.; Garbe-Schoenberg, C.-D. . Sandstone Petrology and Geochemistry of the Turpan Basin (NW China): Implications for the Tectonic Evolution of a Continental Basin. J. Sediment. Res. 2001, 71, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montibeller, C.C.; Rafael, G.; Zanardo, A.; Rohn, R.; Roveri, C.D. Geochemistry of Siltstones from the Permian Corumbataí Formation from the Paraná Basin(State of São Paulo, Brazil): Insights of Provenance, Tectonic and Climatic Settings. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2020, 102, 102582–102582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, J.C.; Cavallaro, F.A.; Garcia, R.H.; Santos, R.S.; Amade, R.A.; da Silva Bernardes, T.L.; Hamada, M.M. Chemical and physical analysis of sandstone rock from Botucatu formation. Braz. J. Radiat. Sci. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkurt, I.; Mavi, B.; Akkurt, A.; Basyigit, C.; Kilincarslan, S.; Yalim, H.A. Study on Dependence of Partial and Total Mass Attenuation Coefficients. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2005, 94, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen Baykal, D.; Tekin, H.O.; Çakirli Mutlu, R.B. An Investigation on Radiation Shielding Properties of Borosilicate Glass Systems. Int. J. Comput. Exp. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelone, M.; Bubba, T.A.; Esposito, A. Measurement of the Mass Attenuation Coefficient for Elemental Materials in the Range 6⩽Z⩽82 Using X-Rays from 13 up to 50 Kev. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2001, 55, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, I.; Demir, L.; Şahin, M. Determination of Mass Attenuation Coefficients, Effective Atomic and Electron Numbers for Some Natural Minerals. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2009, 78, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, S.S.; Sayyed, M.I.; Gaikwad, D.K. Pawar, Pravina P. Attenuation Coefficients and Exposure Buildup Factor of Some Rocks for Gamma Ray Shielding Applications. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2018, 148, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, M.I.; Issa, S.A.M.; Auda, S.H. Assessment of Radio-Protective Properties of Some Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2017, 100, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Azeem, S.A.; Harpy, N.M. Radioactive Attenuation Using Different Types of Natural Rocks. Materials 2024, 17, 3462–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaha, N.; Islam, G.S.; Kabir, M.F.; Khandaker, M.U.; Chowdhury, F.-U.-Z.; Bhuian, A.S.I. Ionizing Radiation Shielding Efficacy of Common Mortar and Concrete Used in Bangladeshi Dwellings. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Al alhareth, A.; Mobark, S.; Al-Mahri, W.; Sharyah, N.A.; Zmanan, S.A.; Albargi, H.B.; Abdalla, A.M. Experimental and Theoretical Investigations of the γ-Rays Shielding Performance of Rock Samples from Najran Region. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2023, 183, 109676–109676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Mudahar, G.S. Energy Dependence of Total Photon Attenuation Coefficients of Composite Materials. Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrumentation. Part A. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2002, 43, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appoloni, C.R.; Rios, E.A. Mass Attenuation Coefficients of Brazilian Soils in the Range 10–1450 KeV. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1994, 45, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şensoy, A.T.; Gökçe, H.S. Simulation and Optimization of Gamma-Ray Linear Attenuation Coefficients of Barite Concrete Shields. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 253, 119218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, L.F. Radiation Shielding Properties of Weathered Soils: Influence of the Chemical Composition and Granulometric Fractions. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2022, 54, 3470–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaky, K.M.; Sayyed, M.I. The Radiation Shielding Parameters of a Standard Silica Glass System. Silicon 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Singh, T.; Kumar, A.; Mudahar, G.S. Energy and Chemical Composition Dependence of Mass Attenuation Coefficients of Building Materials. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2004, 31, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Badiger, N. Investigation on Radiation Shielding Parameters of Ordinary, Heavy and Super Heavy Concretes. Nucl. Technol. Radiat. Prot. 2014, 29, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, S.A.M.; Rashad, M.; Hanafy, T.A.; Saddeek, Y.B. Experimental Investigations on Elastic and Radiation Shielding Parameters of WO3-B2O3-TeO2 Glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 544, 120207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükyıldız, M.; Kılıç, A.D.; Yılmaz, D. White and Some Colored Marbles as Alternative Radiation Shielding Materials for Applications. Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids 2020, 175, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, S.A.M.; Sayyed, M.I.; Kurudirek, M. Study of Gamma Radiation Shielding Properties of TeO2ZnO - TeO2 Glasses. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2017, 40, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsafi, M.; Alrashedi, M.F.; Sayyed, M.I.; Al-Hamarneh, I.F.; El-Nahal, M.A.; El-Khatib, M.; Khandaker, M.U.; Osman, H.; Askary, A.E. The Potentials of Egyptian and Indian Granites for Protection of Ionizing Radiation. Materials 2021, 14, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayana, G.; Baki, S.O.; Kaky, K.M.; Sayyed, M.I.; Tekin, H.O.; Lira, A.; Kityk, I.V.; Mahdi, M.A. Investigation of Structural, Thermal Properties and Shielding Parameters for Multicomponent Borate Glasses for Gamma and Neutron Radiation Shielding Applications. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2017, 471, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, M.I.; Lakshminarayana, G.; Kityk, I.V.; Mahdi, M.A. Evaluation of Shielding Parameters for Heavy Metal Fluoride Based Tellurite-Rich Glasses for Gamma Ray Shielding Applications. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2017, 139, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

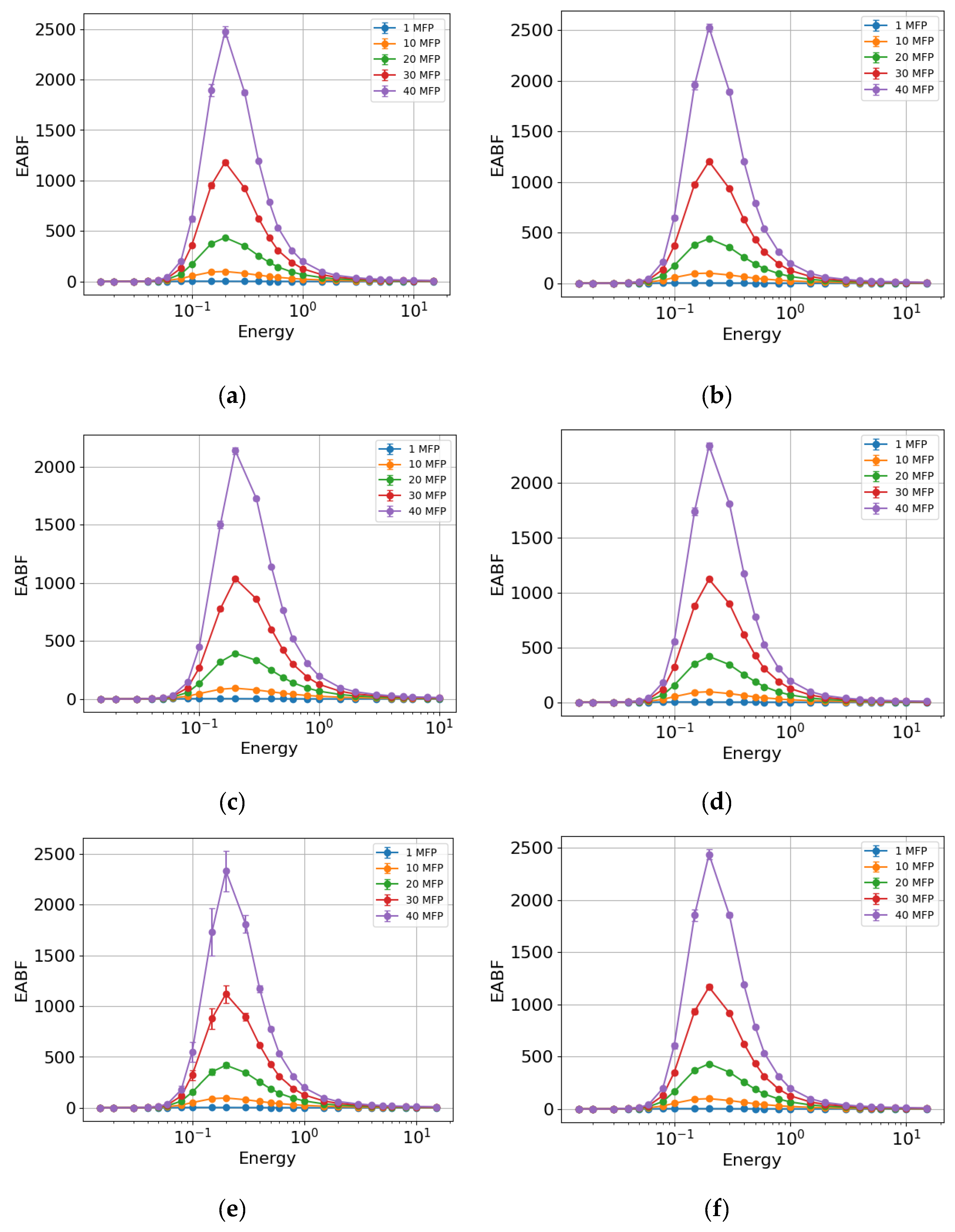

- Karabul, Y.; Amon Susam, L.; İçelli, O.; Eyecioğlu, Ö. Computation of EABF and EBF for Basalt Rock Samples. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A: Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2015, 797, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantan, R.A.R.; Sayyed, M.I.; Mahmoud, K.A.; Al-Hadeethi, Y. Application of Experimental Measurements, Monte Carlo Simulation and Theoretical Calculation to Estimate the Gamma Ray Shielding Capacity of Various Natural Rocks. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2020, 126, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashwan, M.A.; Abdelwahab, W.; Azer, M.K.; Zakaly, H.M.H.; Alarifi, S.S.; Ene, A.; Thabet, I.A. Physico-Mechanical Properties and Shielding Efficiency in Relation to Mineralogical and Geochemical Compositions of Um Had Granitoid, Central Eastern Desert, Egypt. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpuz, N. Radiation Shielding Properties of Glass Composition. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2023, 16, 100689–100689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, M.A.; Kodum, K.S.; Pires, L.F. How does the soil chemical composition affect the mass attenuation coefficient? A study using computer simulation to understand the radiation-soil interaction processes. Braz. J. Phys. 2021, 51, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.C.; Borges, J.A.R.; Pires, L.F.; Arthur, R.C.J.; Bacchi, O.O.S. Soil mass attenuation coefficient: Analysis and evaluation. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2014, 64, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).