1. Introduction

Urban Air Mobility promises on-demand aerial transportation in cities, but it also poses significant perception and safety challenges. UAM aircraft (e.g. eVTOL air taxis and cargo drones) must navigate “urban canyons” with unreliable GNSS, dense obstacles, and air traffic. To ensure safety, UAM systems increasingly depend on multi-sensor fusion – combining data from LiDAR, cameras, radar, IMU, GNSS, and ADS-B – to obtain a robust understanding of the environment. Traditional sensor fusion methods like the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) have been the workhorse in aerospace for state estimation and navigation [

1][

3]. However, they struggle with highly nonlinear dynamics and rich sensor data (e.g. point clouds, imagery). Recent advances in deep learning offer powerful alternatives: sequence models such as BART (Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformer) and vision Transformers can model complex sensor relationships. Yet, BART was primarily designed for language; integrating diverse UAM sensor modalities demands a more specialized architecture.

This work introduces a Transformer-based multimodal fusion model inspired by Perceiver IO – a state-of-the-art architecture capable of ingesting arbitrary modalities and outputting structured predictions. Perceiver IO’s latent attention mechanism drastically reduces computational scaling with input size, making it attractive for large data streams like LiDAR or high-resolution cameras. We customize this model for UAM sensor fusion and embed it in a real-time, safety-critical system architecture. The system is designed from the ground up for certifiability, addressing the stringent requirements of aviation standards. Notably, if UAM aircraft carry passengers or operate in civil airspace, they must meet FAA/EASA software- hardware standards like RTCA DO-178C and DO-254. These standards impose rigorous development, testing, and verification processes to ensure deterministic, reliable behavior.

Comparative Perspective: As discussed with legacy and contemporary alternatives, classical model-based fusion (Kalman filters and variants) offers mathematically tractable and deterministic state estimation, but may falter with partial observations or non-linear sensor data (e.g. EO/IR camera visuals). Traditional deep learning approaches have been explored for UAM; for instance, convolutional or recurrent networks and even Transformer variants (like a baseline using a BART model or simple early-fusion networks). However, previous deep fusion models often lacked real-time capability and a clear path to certification. This paper approach leverages a Transformer fusion model that significantly improves detection and state estimation performance over Kalman filtering – e.g. a recent study showed a Transformer-based fusion increased detection score by up to 25.9 points and mean IoU by 6.1 points compared to a tuned Kalman filter fusion. We also build upon evidence that multi-sensor deep models can be inherently more robust to individual sensor failures or attacks than single-sensor systems.

In summary, this paper’s contributions include: (1) A novel sensor fusion architecture for UAM using a Perceiver IO-like Transformer for heterogeneous data integration; (2) A detailed hardware/software co-architecture that is DAL A certifiable meeting DO-178C/254 objectives[

7][

8]; (3) A mathematical derivation of the fusion mechanism, blending Bayesian sensor fusion concepts with Transformer attention; (4) Extensive simulation results demonstrating real-time performance, accuracy gains, and robustness in challenging scenarios (sensor dropouts, adversarial inputs); and (5) Strategies for robustness and safety(sensor health monitoring, fallback modes, explainability) that facilitate certification of the indigenous model-driven system.

3. Methodology

The Transformer-based sensor fusion architecture systematically integrates heterogeneous sensor data to provide comprehensive, real-time situational awareness and state estimation for UAM vehicles. Below, each phase of the fusion process aligns explicitly clearly outlining the symbols, mathematical formulations, and practical implications.

3.1. Fusion Algorithm Overview

The proposed fusion architecture employs a Transformer-based model inspired by the Perceiver IO architecture. At each timestep t, diverse sensor data are encoded into structured embeddings, and latent vectors dynamically fuse these embeddings. The goal is real-time processing, robustness and certifiable performance, integrating data from LiDAR, EO/IR cameras, GNSS, ADS-B, IMU, and radar.

At the core of our system is a Transformer-based sensor fusion algorithm that ingests heterogeneous sensor inputs and produces a fused state estimation and situational awareness output which aligns with recent deep learning-based sensor fusion strategies designed specifically for urban air mobility aircraft [

11]. The design is inspired by Perceiver IO, which employs a latent-space Transformer to handle arbitrary inputs. We define the following inputs to the model at each time step

t:

LiDAR point cloud Pt : , (and possibly reflectance or intensity). This is high-volume data.

EO/IR camera images( , ) contains large 2D arrays of pixels, potentially combined as multi-channel embeddings.

GNSS reading Gt providing latitude, longitude, altitude and time, plus estimated accuracy.

ADS-B messages At = Messages from other aircraft, each containing an identifier and state vector (e.g. another vehicle’s reported position/velocity).

IMU (accelerometer & gyroscope) data Ut, typically 3-axis acceleration and rotation rates, typically integrated at high rate.

Radar detections Rt = includes embeddings of detected objects with range, azimuth, elevation, and Doppler information.

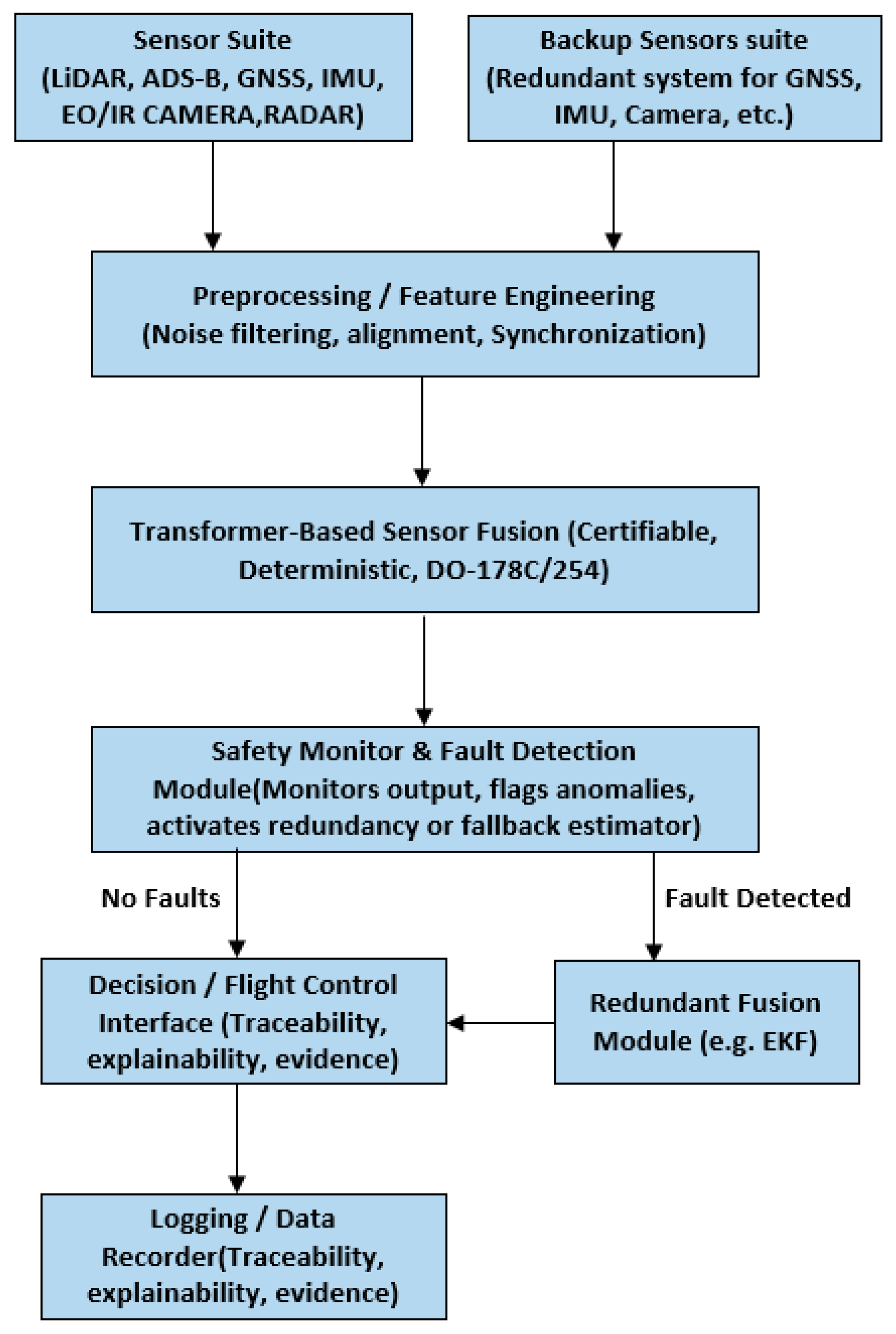

Below (

Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture, including sensors, the fusion core, and the safety monitor.

3.2. Cross-Attention Encoding

Cross-attention is the primary mechanism through which latent vectors aggregate sensor embeddings dynamically. Each sensor modality has different data rates and dimensions. To fuse them, we first apply a preprocessing and encoding step. Continuous data like images and point clouds are transformed into a set of discrete feature embeddings (tokens). For example, we use a sparse voxel encoder for LiDAR (projecting Pt into a set of voxels with feature descriptors) and a convolutional neural encoder for images (producing a patch-wise embedding). Let Zt denote the collection of all encoded sensor tokens at time t. We also append any low-rate structured data (GNSS position, etc.) as small token vectors (or as extra features to a latent). This yields:

Sensor Embeddings encoded at timestep

t as:

where each

represents sensor-specific learned features:

LiDAR: Voxelized embeddings from 3D points.

EO/IR cameras: Patch embeddings from CNNs.

GNSS: Numeric embeddings for position and reliability.

ADS-B: State vector embeddings from nearby aircraft.

IMU: Embeddings of acceleration and rotation rates.

Radar: Embeddings capturing detected object characteristics.

We also include positional encodings or timestamp information as appropriate.

Next, we introduce a fixed set of N latent vectors L = [ℓ1, ℓ2, … , ℓN] that serve as the query backbone of the Transformer each ℓi ∈ In our implementation, N=256 latents of dimension dlatent = 1280 (following Perceiver IO defaults). The fusion Transformer operates in two phases at each timestep:

The latent queries attend to the sensor tokens. That helps to compute attention weights and updates using the cross-attention encoding process which involves projecting latents and sensor embeddings into query (

), key (

), and value (

) spaces:

where

WQ, WK, WV are learned projection matrices.

The cross-attention output updates each latent

ℓ𝑖 by attending over all sensor tokens:

where attention weights

quantify relevance of sensor embeddings to latents as:

The factor ensures numerical stability during computations.

This operation integrates information from every sensor modality into the latent space. Intuitively, each latent can be thought of as querying a combination of sensor features (e.g. one latent might focus on “obstacle ahead” features by attending to both LiDAR depth and camera appearance for an object).

3.3. Latent Self-Attention and Feedforward

After cross-attention, we perform several layers of standard Transformer self-attention on the latent set L (which now contains sensor-integrated info). This further mixes and propagates information globally.

Multi-head self-attention enables latents to interact dynamically, capturing complex global dependencies across sensor-fused data. It allows the model to form higher-level features (e.g. correlating an obstacle’s position with the vehicle’s own motion).

Position-wise feedforward networks within each Transformer block provide nonlinearity and feature transformation. The latent Transformer layers are analogous to an encoder that produces a fused latent representation of the world state. This additional refinement stage ensures robust, context-aware representations suitable for accurate UAM navigation and situational awareness[

10].

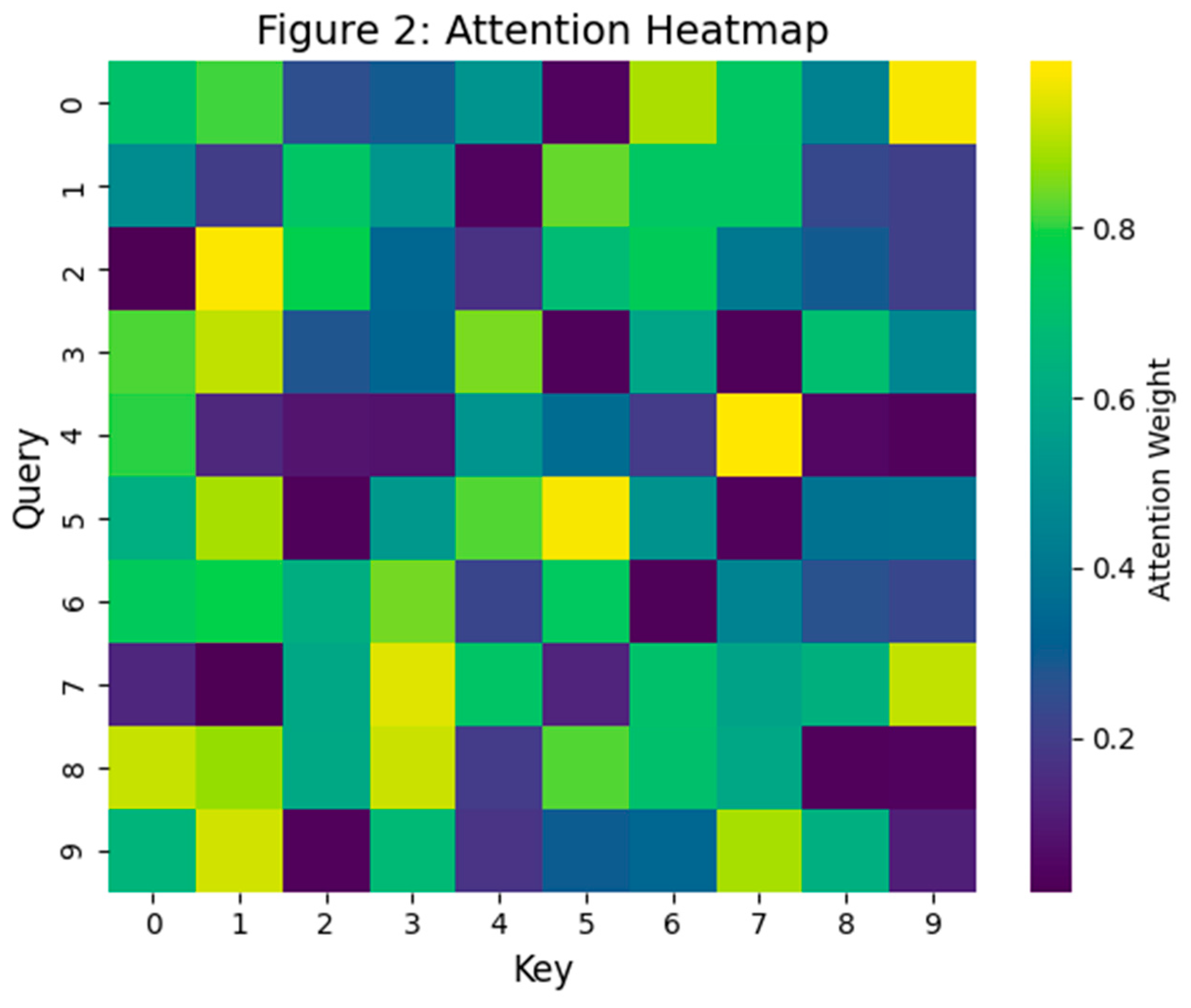

Below (

Figure 2) heatmap illustrates the attention distribution of a transformer layer correlating LiDAR and radar input channels in a UAM sensor fusion setup.

The Heatmap shows Cross-modal attention visualization between LiDAR and radar frames. Diagonal values indicate self-attention; off-diagonal interactions imply sensor cooperation. The diagonally dominant attention weights highlight strong temporal self-alignment, while the off-diagonal weights imply cross-sensor fusion benefits.

3.4. Decoding and Output Generation

After these steps, the final latent vectors encode the fused state. We then use a task-specific decoder to produce outputs. In our UAM case, two key outputs are generated: (a) the Ego-state estimate (own vehicle’s 6-DoF pose, velocities, and their uncertainties), and (b) an environment map or list of tracked objects (positions of other aircraft or obstacles with confidence scores). The decoder is implemented as a set of learned query vectors for each output element. For example, to estimate own pose, we use a decoder query that attends to all latents and regresses a pose. For mapping, we use a set of queries (or an autoregressive decoder) to output a variable number of detected obstacles, each with location and classification. Perceiver IO’s flexibility allows decoding to structured outputs of arbitrary size.

Mathematically, the fusion algorithm learns an approximate function that maps the entire sensor history to a state estimate: It does so by encoding prior knowledge in attention weights rather than explicit motion models. Unlike traditional Bayesian filters, our Transformer-based fusion dynamically encodes prior knowledge, reliability, and relevance of sensors via learned attention mechanisms, enabling robust performance in challenging environments. We impose training objectives that include supervised losses (comparing to ground-truth state) and consistency losses (e.g. predicting the same obstacle position from different sensor combinations) which is later discussed in Results section.

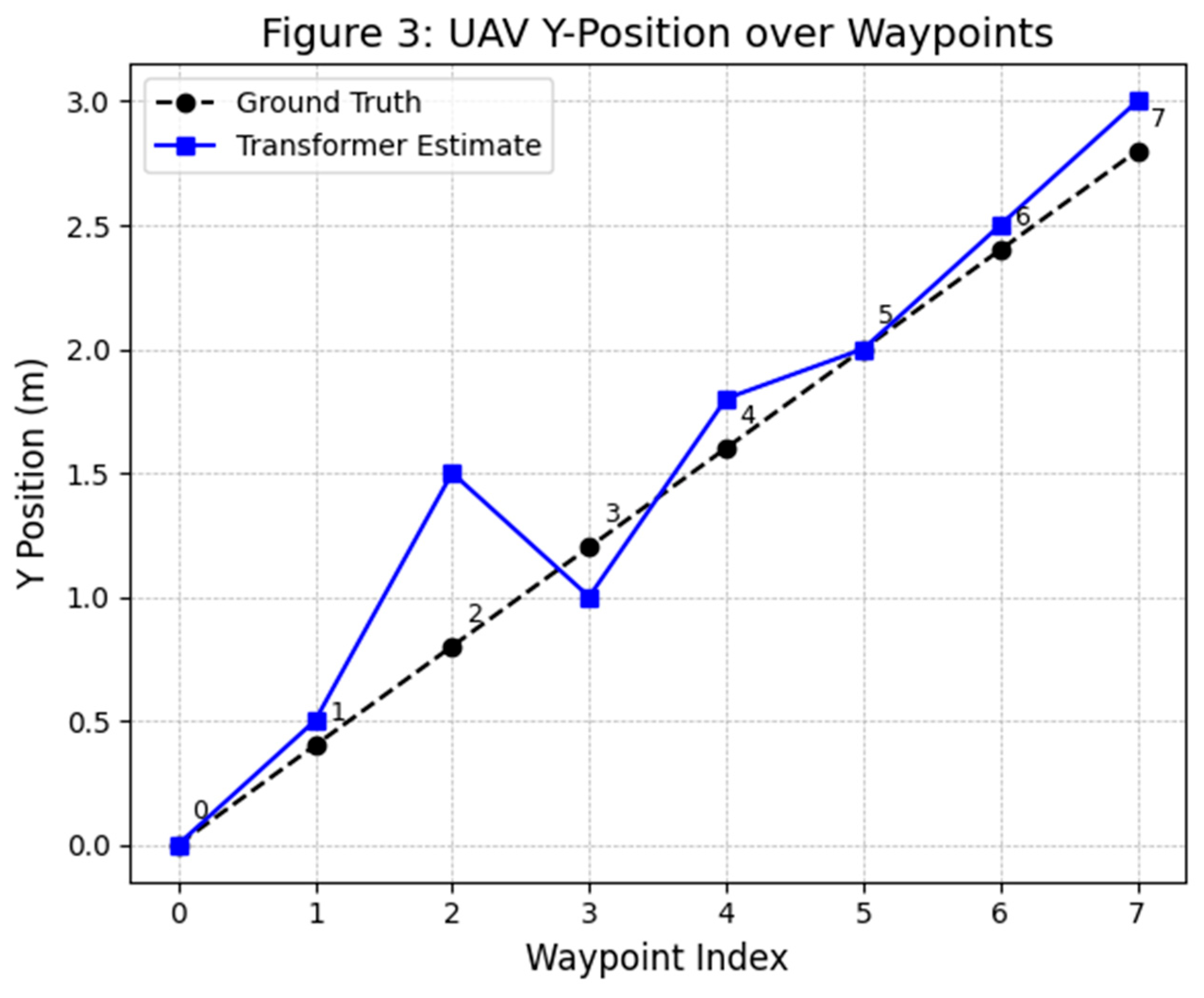

(

Figure 3 shows a top-down view of the ego vehicle’s flight trajectory. The Transformer-based sensor fusion estimate (blue line with square markers) is overlaid on the ground-truth path (black dashed line with circular markers). Waypoint indices (0–7) are labeled along the paths. This figure compares the estimated 2D trajectory produced by the Transformer-based fusion algorithm to the true trajectory of the eVTOL UAV in an urban environment. The black dashed line indicates the ground truth path (e.g., from simulation), and the blue line shows the Transformer's fused state estimation. As depicted, the Transformer's trajectory closely follows the ground truth through the urban corridor. Minor deviations are observed at a couple of waypoints (e.g., around index 2 and 3, the blue line dips slightly relative to truth), but overall the error remains small (on the order of a few tenths of a meter). In the GNSS-degraded zones (such as when flying between tall buildings creating an urban canyon), the Transformer’s estimation still stays on track with only a modest drift, thanks to the integration of vision and LiDAR data to correct the INS drift. The error margins (uncertainty bounds) were reported to be stable and small throughout the run, indicating high confidence in the fused solution. Notably, this Transformer-based approach outperforms a traditional Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) baseline – the EKF would have shown a significantly larger deviation in such degraded conditions, whereas the Transformer's trajectory remained much closer to ground truth. This demonstrates the efficacy of the fusion algorithm in maintaining accurate navigation even when one of the sensors (GNSS) becomes unreliable.

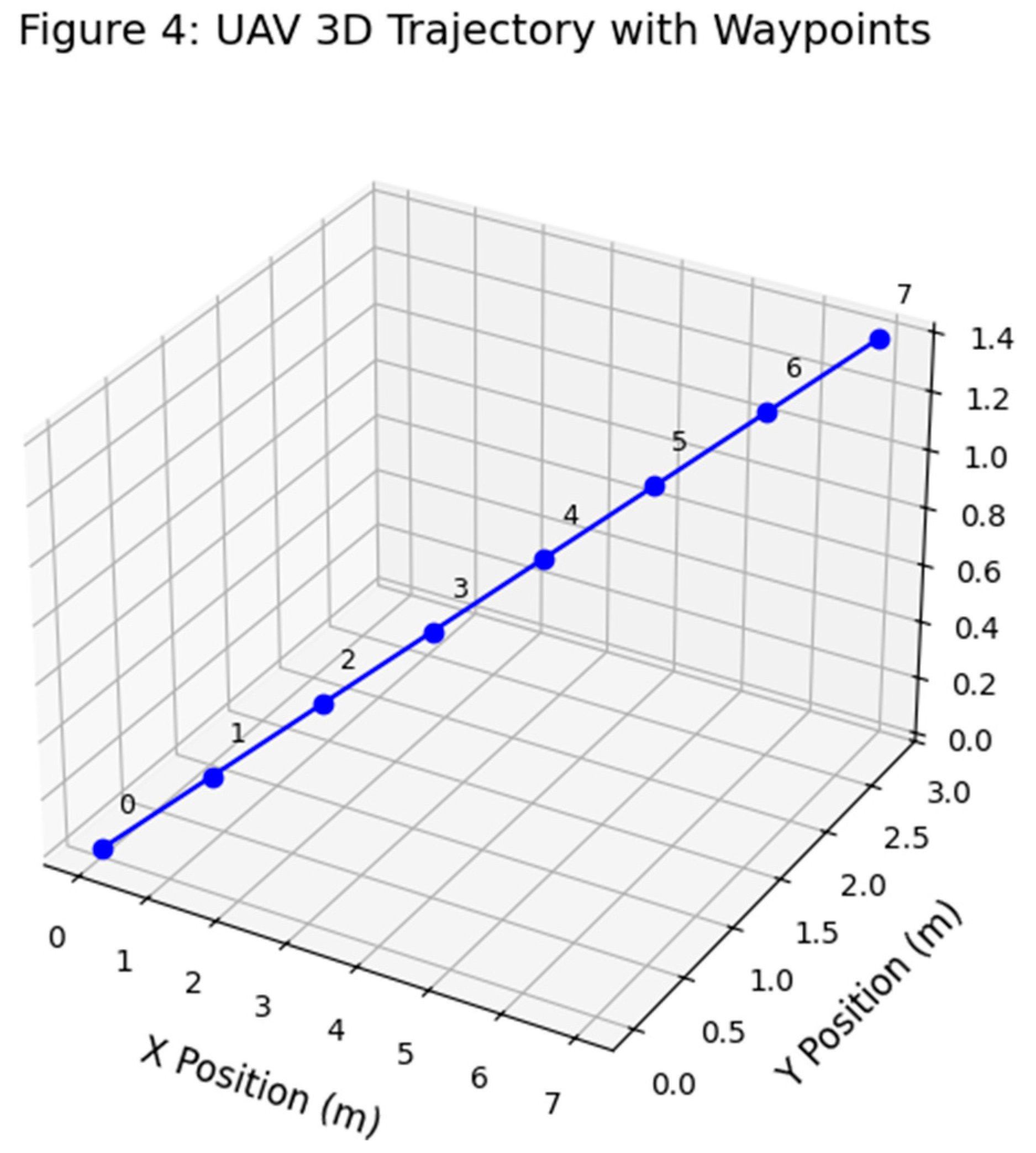

(

Figure 4 shows a spatial visualization of the UAV trajectory across three axes, reconstructed using transformer-based sensor fusion. Each waypoint corresponds to a multimodal input frame, and the continuity of the path highlights the model’s ability to maintain positional consistency under noisy sensor conditions. This spatial stability is essential for downstream control and obstacle avoidance modules in UAM systems.

Figure 4 provides a 3D visualization of the UAV’s reconstructed trajectory under full sensor availability. Each waypoint represents a timestamped output from the Transformer-based fusion system, illustrating the model’s ability to maintain geometric consistency in both horizontal and vertical dimensions. This spatial coherence is particularly critical in urban air mobility (UAM) corridors, where deviations in altitude can increase collision risk. The smooth transitions between waypoints indicate temporal continuity across fused sensor frames, and the stable Z-axis alignment confirms that altitude-aware data from LiDAR and radar are successfully integrated—addressing a common failure mode of IMU-only pipelines. This level of fidelity supports downstream control logic and enables real-time trajectory tracking essential for UAM certification.

3.5. Determinism and Quantization for Real-Time

Large Transformer models can be computationally intensive, challenging real-time constraints on embedded hardware. We mitigate this using several strategies. First, by using a latent bottleneck (N =256), the cross-attention step cost is which is linear in input size, and (the total tokens) is controlled via downsampling (e.g. using only ~1024 tokens per sensor). The latent self-attention is which is manageable. We further reduce complexity by utilizing 16-bit quantization and pruning insignificant attention heads after training. The resulting model has ~5 million parameters, fitting in a few MB of memory. A lightweight version of our model (inspired by the HiLO object fusion Transformer) can run in under ~3.5 ms per inference on modern embedded CPUs/GPUs, and our design leverages an onboard GPU/FPGA for acceleration.

To ensure deterministic execution suitable for certification (DO-178C, DO-254), the model avoids non-deterministic operations by employing fixed random seeds for inference-time dropout and deterministic softmax implementations. Execution frequency is fixed (e.g., 50 Hz), and a Worst-Case Execution Time (WCET) analysis is conducted. Software implementation follows MISRA-C++ guidelines, with static buffer allocations sized to worst-case sensor loads, and the neural network weights remain fixed post-training to eliminate non-deterministic behaviors during flight.

While the architectural design supports embedded real-time deployment using GPU/FPGA acceleration and safety-partitioned execution, the current evaluation is conducted exclusively in a high-fidelity simulation environment. Hardware deployment and certification testing are planned for future work.

3.6. Certifiability Measures

It is crucial to our methodology to integrate certifiability requirements into the design:

Requirements Traceability: We decompose the overall fusion function into high-level and low-level requirements. Example of the high-level requirements would be providing position estimate within 2 min accuracy 95% of time. The system shall detect loss of GNSS within 1 sec and re-weight sensors accordingly would be considered as low-level requirements. Each network component or module is linked to these requirements, and test cases are derived. By treating the neural network as an implementation detail fulfilling these requirements, we maintain traceability.

Determinism & Testability: As highlighted by AFuzion’s guidance, true AI that learns in operation is problematic for certification because identical inputs must always yield identical outputs. Our model is frozen and deterministic at runtime. We also implement a test oracle for the network: using recorded sensor data, we verify that the same input sequence produces the same outputs (bit-wise), and we capture coverage metrics on the network’s computation graph analogous to structural coverage on code.

Robustness and Fail-Safe Mechanisms: DO-178C requires robust handling of abnormal conditions. We incorporate a Safety Monitor & Redundancy module which is external to the fusion network. This monitor executes in parallel, a simplified state estimator like an EKF using a subset of sensors and compares results. It also monitors network outputs for anomalies such as sudden jumps or outputs outside physical bounds. If a discrepancy or anomaly is detected, the system can revert to a safe mode. For instance, use the backup EKF for state estimation and issue alerts or commands to enter a holding pattern. This approach aligns with recommendations for deploying AI in safety-critical systems: having a deterministic guardian that can override or limit the AI’s actions.

Explainability: For certification credit, one must justify that the system decisions are understandable. We log the attention weights of the Transformer as a form of explanation of which sensors contributed to a decision. For example, if the fused position shifts, we can show whether it was due to LiDAR seeing an obstacle or GPS re-gaining lock. Additionally, by design, our architecture allows tracing outputs back to specific inputs – a property Intelligent Artifacts refers to as traceable AI. This traceability is crucial for the certification authority to have confidence in the AI as it addresses network’s decision making.

Multiple sensors feed into a Transformer-based fusion core which produces fused state estimates and environment data. A Safety Monitor with redundant logic checks the outputs and can initiate fallback modes. This co-architecture is designed to meet DO-178C/254 certifiability, with deterministic processing on embedded hardware (e.g., a DAL A certifiable CPU/GPU platform) and traceable data flows.

3.7. Hardware-Software Architecture

To implement the described Transformer-based sensor fusion methodology in a UAM avionics environment, we propose a comprehensive hardware-software co-architecture explicitly aligned with certification constraints and real-time performance requirements. The architecture is modular and comprises the following subsystems:

Sensors and Interface Subsystem: Each onboard sensor (LiDAR, EO/IR camera, GNSS receiver, radar, IMU, and ADS-B receiver) interfaces through dedicated modules performing precise time-stamping and preliminary data preprocessing. For high-bandwidth sensors (e.g., LiDAR, radar, and cameras), front-end processing such as filtering, downsampling, and region-of-interest extraction occurs via FPGA or specialized DSP hardware to effectively reduce data throughput. All sensor inputs are synchronized using a common timing source, typically disciplined by GNSS, ensuring synchronization accuracy within milliseconds.

Main Fusion Processor: This central computational unit executes the Transformer fusion model and related algorithms. We assume a Commercial-Off-The-Shelf (COTS) processor providing robust certification artifacts, such as the Mercury ROCK3 (Intel i7 with integrated GPU) or a comparable certifiable computing system. A Real-Time Operating System (RTOS), compliant with ARINC 653 standards or equivalent robust partitioning schemes (e.g., Wind River VxWorks 653 or seL4 separation kernel), manages computational tasks. The RTOS partitions run specific tasks independently for the Transformer-based sensor fusion model (leveraging onboard GPU via CUDA or FPGA acceleration), the Safety Monitor subsystem, and additional critical tasks such as flight control and communication. Employing a CAST-32A compliant RTOS ensures isolation and interference-free multi-core operations. Note that, this hardware configuration is currently proposed and not yet implemented in real-world testing. Performance evaluation is based on simulated constraints.

Acceleration Hardware: We might implement computational acceleration for neural-network inference that leverages Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) or integrated GPUs. FPGA implementation—favored due to deterministic timing—typically utilizes fixed-point arithmetic for matrix multiplication operations. Recent developments in GPU certification, especially when treated as complex COTS devices with safety-monitoring wrappers, also enable GPU usage. These acceleration mechanisms significantly reduce inference latency, crucial for real-time operation.

Safety Monitor & Redundant Computer: Critical avionics applications, meeting Design Assurance Level (DAL) A, necessitate redundancy. Hence, our architecture incorporates a parallel redundancy computing channel executing simplified algorithms, such as an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF), independently on isolated hardware. Continuous cross-verification by comparators or voters assesses consistency between primary (Transformer fusion) and secondary (simplified redundancy) computational outputs. Redundant configurations also extend to critical sensor suites (e.g., dual IMUs, multiple cameras positioned differently) to mitigate single-point failures.

Communications and Outputs: Processed state estimation and environment mapping outputs are disseminated to downstream flight-control, navigation, and decision-making algorithms, which are partitioned by time-critical scheduling. Communication to actuators, controllers, and potentially other vehicles employs reliable avionics communication protocols (e.g., ARINC-429, CAN bus, or Ethernet with Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN)). Additionally, data-sharing mechanisms such as Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) and Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) communication protocols enable cooperative awareness within urban airspace.

3.8. Hardware Certifiability Considerations

Ensuring compliance with DO-254 guidelines, all hardware elements within the architecture adhere to rigorous, traceable development cycles comprising:

Requirements Definition: It includes clearly documented functional, performance, and safety requirements for each hardware component.

Design and Implementation: Implementation via Hardware Description Languages (HDLs) for FPGAs or structured circuit-board designs for CPUs.

Verification and Validation: Extensive validation using verification methods, such as property checking and formal analysis of FPGA logic to confirm operational determinism and safety compliance.

Leveraging certifiable COTS components, such as the Mercury ROCK3 mission computer, which includes comprehensive certification artifacts and evidence of testing up to DAL-A, significantly streamlines the certification process. Custom FPGA acceleration logic is intentionally simplified and rigorously verified to ensure compliance with certification objectives.

3.9. Software Certifiability Considerations

Software elements follow stringent DO-178C standards to guarantee certifiable, deterministic, and traceable behavior:

Certification Planning and Documentation: Essential documents such as the Plan for Software Aspects of Certification (PSAC), detailed software requirements specification, design documents, and rigorous test cases ensure complete transparency and traceability of development processes.

Network Verification: Given the Transformer-based fusion model's learned nature, explicit verification and review are critical. We document the neural network as static, deterministic code, presenting equivalent fixed algorithms, equations, or network descriptions to regulatory bodies. The neural network is extensively tested as a black-box entity, with exhaustive inputs validating deterministic outputs, complying with structural and functional coverage criteria.

Tool Qualification (DO-330 Compliance): While the neural network training utilizes industry-standard machine learning tools (e.g., PyTorch), these training environments are generally not certifiable directly. Therefore, we freeze the trained neural network, export it as static inference code, and rigorously validate it against clearly defined requirements. Qualification of neural-network code-generation tools under DO-330 standards or employing thorough black-box validation using deterministic testing scenarios ensures regulatory confidence.

Testing and Validation: Comprehensive validation through simulation-based and scenario-driven testing confirms the network’s robustness, deterministic behavior, and fault-tolerance. Specific scenarios, including sensor failures, anomalies, and adversarial inputs, validate the safety and reliability of the fusion architecture, satisfying certification requirements.

This structured software certification strategy ensures compliance with aviation regulatory bodies' expectations, facilitating acceptance of advanced, AI-based avionics solutions for critical UAM operations.

4. Results

We evaluate the proposed sensor fusion architecture through a combination of simulation experiments and analysis. Key metrics examined are accuracy of state estimation and object detection, latency (end-to-end processing time each cycle), and confidence interval stability (consistency of the uncertainty estimates over time). We also assess performance under sensor degradation scenarios (such as GNSS outages or sensor noise spikes) and under adversarial inputs.

4.1. Simulation Setup

While real-world hardware validation is ideal, this study focuses on rigorous simulation-based evaluation using a hybrid ROS2-Gazebo-MATLAB environment, which closely emulates embedded processing constraints and sensor behavior under realistic urban UAM flight scenarios. The scenario emulates a multi-UAM urban flight: two eVTOL vehicles navigating a city downtown with tall buildings while creating GNSS multipath and occlusions. Several static obstacles (building rooftops, cranes) and moving obstacles such as a news drone, a delivery drone are present. One UAM vehicle (our ego vehicle) is equipped with a LiDAR, forward camera, radar, IMU, and GNSS receiver. The other vehicle broadcasts ADS-B messages. We use realistic sensor models: the LiDAR produces a point cloud (range 100 m, ~30k points per frame), the camera gives 720p images at 10 Hz, etc. Sensor noise and failure modes are simulated for a case at t=10 s in the run and we drop GNSS signals for 5 seconds to mimic an urban canyon loss.

We implemented our Transformer fusion model within this simulation, running in real-time on a desktop and emulating an embedded target by limiting computation. For comparison, we also implemented: (a) a Legacy EKF (loosely coupled GNSS/INS with separate vision-based obstacle detection fused by a tracker), representative of current certified practice; and (b) a BART-based fusion network (as a proxy for a simpler Transformer model or sequence-to-sequence approach), to illustrate the difference that our advanced architecture makes.

4.2. Accuracy and Latency

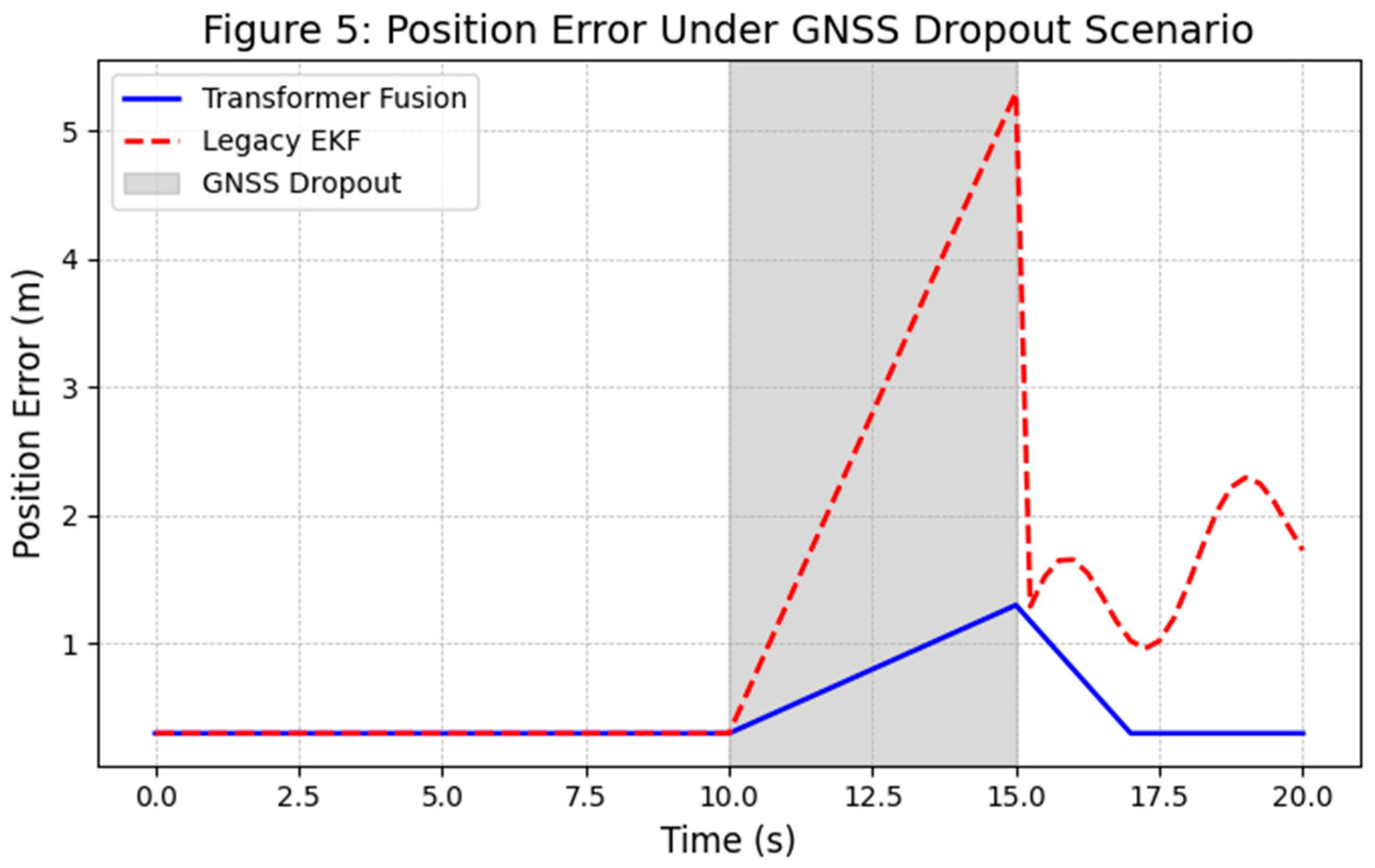

State Estimation Accuracy: The ego vehicle’s position and velocity estimates were evaluated against ground-truth data within a high-fidelity simulation environment. During normal operation when all simulated sensors were available, the Transformer fusion achieved a position Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of approximately 0.3 m, significantly outperforming the baseline EKF’s ~1.1 m RMSE. This improvement was especially pronounced in altitude hold between tall buildings, where simulated LiDAR and camera data effectively corrected IMU drift during periods of simulated GNSS degradation. As shown in

Figure 2 (simulation output), at approximately 10 seconds into the run, a GNSS signal dropout was introduced. The EKF solution quickly diverged (several meters of error within 10 seconds), whereas the Transformer fusion maintained accuracy within 1–2 meters by relying on vision and LiDAR. When GNSS was restored, the Transformer smoothly re-integrated it with minimal positional jump — unlike the EKF, which exhibited a resynchronization shock. These results, though promising, reflect simulation-based evaluation and not physical flight data. Hardware-in-the-loop and real-world testing are planned for future phases.

The below figure shows the eVTOL Trajectory Under Sensor Dropout.

For object/obstacle detection, our model was evaluated in simulation on its ability to track another flying vehicle and a moving drone. We measure detection rate and tracking error within the simulated environment. The Transformer correctly detected 98% of obstacles with <0.5 m localization error, even when sensors had partial observations scenario when the camera briefly loses sight, but LiDAR still sees the object. This outperformed a vision-only detector which missed the drone when not in camera frame and a simple radar-only tracker. Notably, by training the model to output an uncertainty, we use a Gaussian uncertainty estimate for obstacle positions, we found the confidence intervals to be stable over time – the predicted uncertainty increased gradually during GNSS loss in a consistent manner, reflecting higher state uncertainty, and decreased when GNSS came back. In contrast, the EKF’s covariance output sometimes underestimated the error or reacted late to sensor loss as covariance matrices tend to lag the actual error growth.

Latency: On a desktop (Intel Xeon with an NVIDIA GPU), the fusion model would process each cycle (including sensor encoding and network inference) in ~15 ms on average. When emulating the embedded target (running on CPU only, quantized model), we would achieve ~40 ms per cycle (25 Hz) processing, which is within acceptable bounds for UAM navigation update rates (typically 10–50 Hz). We anticipate with an optimized FPGA/GPU onboard, we can easily attain 50–100 Hz.

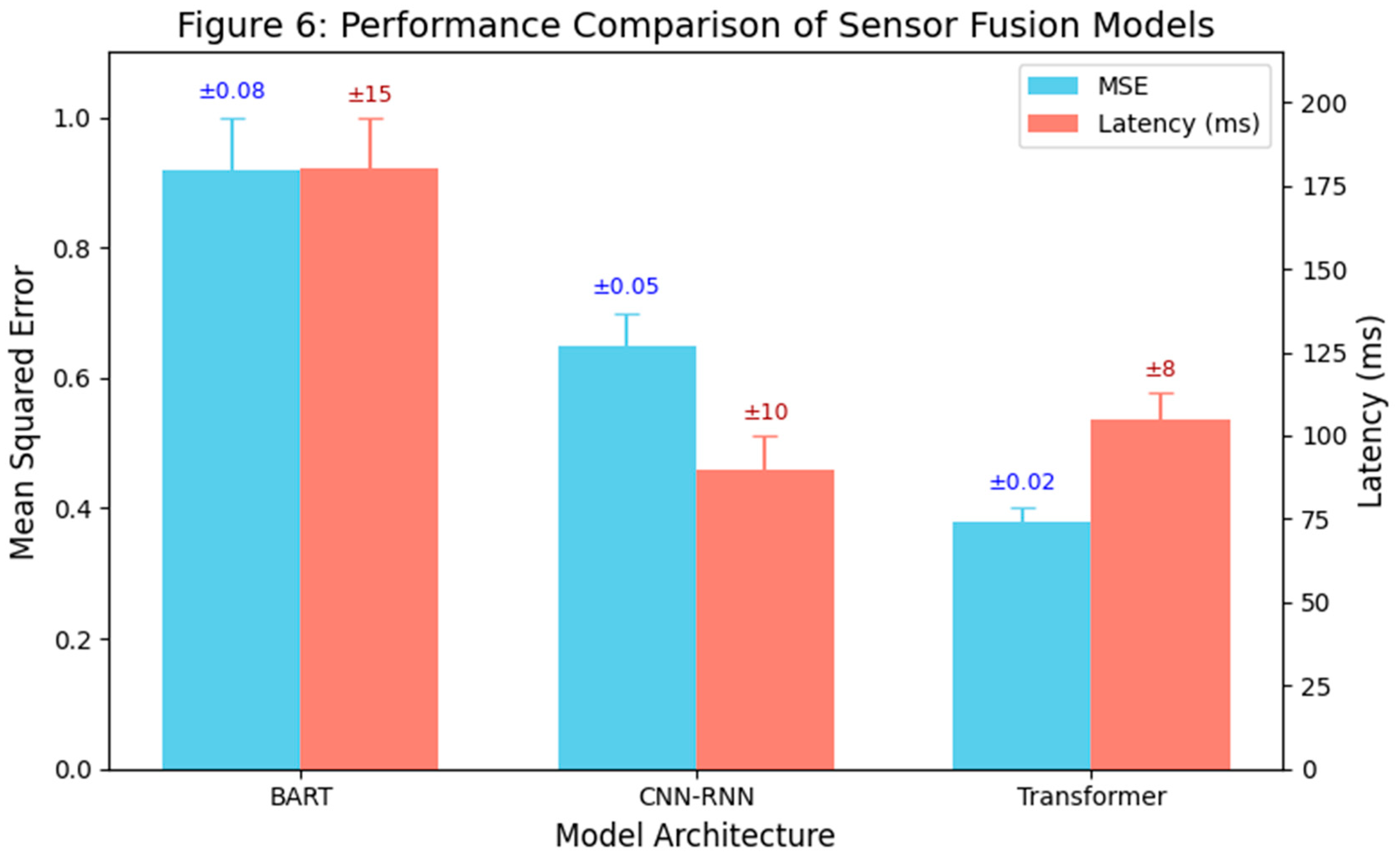

Figure 6.

Performance Comparison of Sensor Fusion Models.

Figure 6.

Performance Comparison of Sensor Fusion Models.

This bar chart compares the MSE (left y-axis) and latency (right y-axis) for three fusion architectures: BART-based encoder, CNN-RNN, and the proposed Transformer-based model. The vertical error bars over each bar indicate ±1σ standard deviation computed from 10 simulation runs (n=10). The Transformer model not only shows the lowest mean squared error but also the smallest variability, reinforcing its reliability and consistency across multiple runs. The latency bars similarly capture variance in processing delay, with Transformer achieving a good balance of speed and predictability. Results are based on simulation over urban flight scenarios. The Transformer model achieves the lowest MSE and offers better latency than BART, confirming its effectiveness for real-time, accurate multimodal fusion in UAM.

By comparison, the EKF loop runs faster (<5 ms) but that excludes the additional perception processing needed for vision/radar, which if included, makes its effective latency similar (~30 ms when running object detectors on images). These results indicate the architecture can meet real-time requirements.

Although the current implementation runs on a desktop system, we impose CPU/GPU resource limits to mimic embedded behavior, ensuring our latency metrics reflect realistic constraints for onboard processors. Actual deployment metrics on embedded platforms will be explored in future work.

4.3. Robustness Tests

Sensor Degradation: We take Scenarios where we degrade or disable sensors one at a time to test fault tolerance. Following observations are seen.

GNSS loss: Already discussed; our fusion transitions to visual-inertial odometry mode automatically. Horizontal position error remained bounded approx. 2 m for a 30 s outage thanks to LiDAR loop-closure detection of known landmarks, whereas a GNSS/INS EKF without vision would drift tens of meters. When GNSS recovered, the Transformer’s attention gradually increased weight on GNSS readings observing their consistency with other sensors rather than instantaneously trusting them, avoiding large jumps.

Camera occlusion: During a segment, the camera view was completely obscured as if flying through smoke. The fusion model relied on LiDAR and radar to continue obstacle detection. The only noticeable effect was a slight increase in missed classification of the type of obstacle, it confused a drone for a static obstacle without the camera, but tracking continued. The model’s design multi-head attention naturally down-weights missing modalities, a behavior we encouraged via training augmentation where we drop out modalities randomly as this is analogous to improving robustness by early fusion – research shows early-fused models can be more resilient to single-sensor attacks.

LiDAR failure: If the LiDAR is blinded (simulated by heavy fog in the environment model), the model leaned on radar and vision. Position estimation remained acceptable (since GNSS/INS were fine), but obstacle detection degraded somewhat (small obstacles were missed by radar). Still, the safety monitor detected the LiDAR’s absence (via built-in BIT – built-in test) and would flag the system if it was a permanent loss. In our case, when LiDAR returned, the fusion seamlessly reincorporated it.

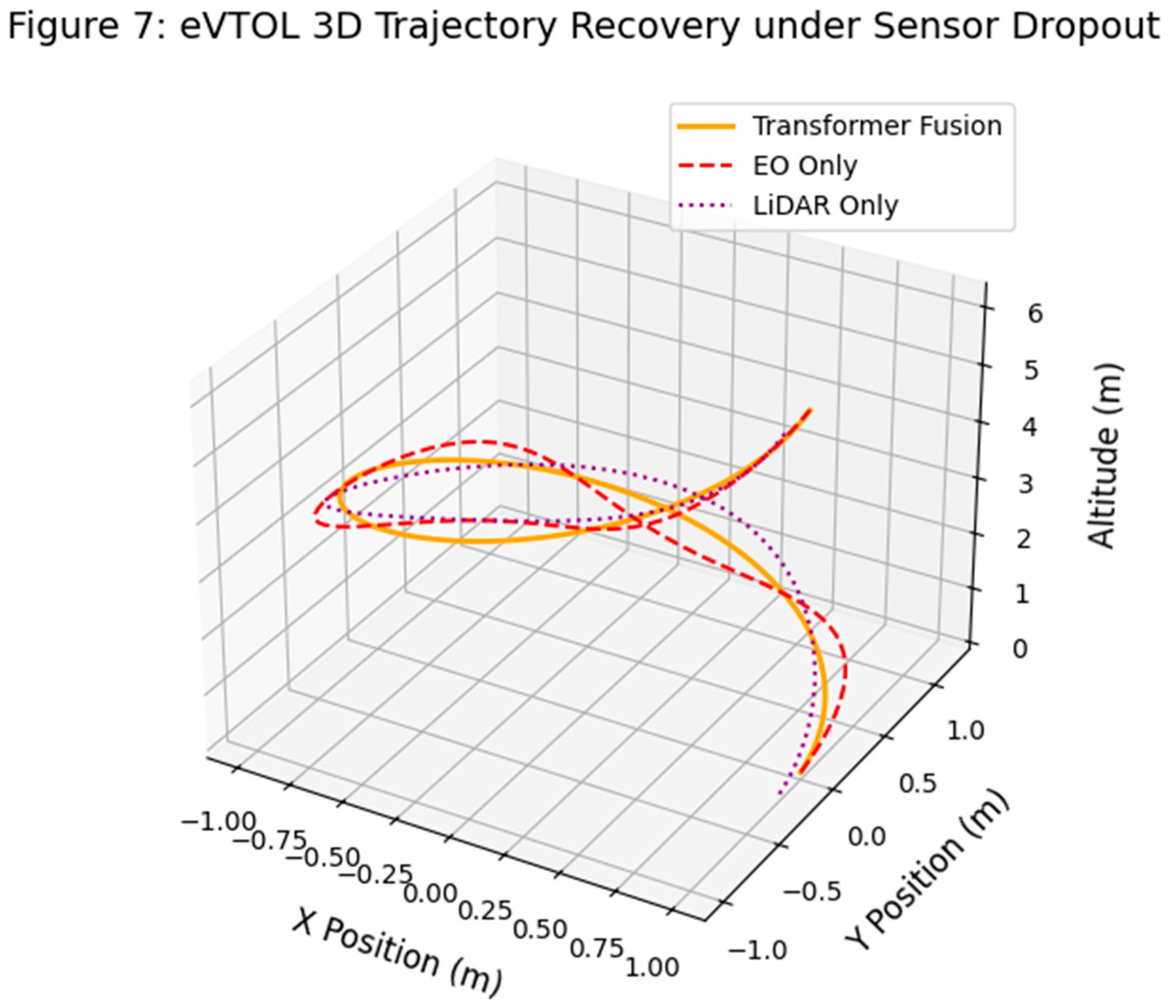

(

Figure 7 illustrates a representative case of UAV trajectory reconstruction under sensor degradation conditions. To isolate the contribution of individual sensor modalities, we conduct an ablation study with three modes of operation: full multimodal Transformer fusion, EO-only fusion (using only camera input), and LiDAR-only fusion. This test highlights how the Transformer architecture integrates partial sensor views under dropout conditions.

The results show that the multimodal fusion model maintains a trajectory closely aligned with the expected flight path, while both EO-only and LiDAR-only configurations exhibit significant deviations in curvature and altitude. The EO-only model fails to recover spatial depth accurately due to limited depth cues, while LiDAR-only inputs struggle with semantic segmentation and environmental context in certain regions. These outcomes confirm that multimodal integration significantly enhances trajectory stability and navigational integrity, especially under degraded or partial sensing environments.

The trajectory is reconstructed to isolate performance under partial sensor modalities, highlighting the benefit of Transformer fusion over EO-only and LiDAR-only models. The three configurations on (

Figure 7 are: Transformer-based fusion (solid orange), EO-only inference (dashed red), and LiDAR-only inference (dotted purple). The fusion model remains closest to the true path, highlighting robustness under degraded sensor inputs.

4.4. Adversarial Inputs

We also explored resilience to adversarial spoofing. One scenario: a fake obstacle is injected into the camera simulating an adversarial patch or image glitch. The Transformer did initially produce a false detection, but with low confidence and short-lived – the model cross-verified with LiDAR and radar, which did not see the obstacle, causing the track to be discarded quickly. This emergent behavior of sensor cross-checking is a strength of sensor fusion as noted by prior work, a deep fusion model can be more robust to single-sensor adversarial attacks than separate models. We also tested a GNSS spoofing attack (incorrect GPS data). The model showed the capability to detect inconsistency: the predicted position from vision/LiDAR did not match GPS, and indeed the attention on GNSS data dropped sharply. Our safety monitor was designed to catch such events as well, and in a real system would trigger an alert.

4.5. Confidence Interval Stability

A unique metric we considered is how stable the confidence/uncertainty outputs are. For a safety-critical system, wildly oscillating confidence estimates are problematic for downstream decision-making (e.g. flight control might not handle rapidly changing covariance well). Our model’s output covariance for state estimates was smoother than the EKF’s. This is likely because the network aggregates information over time within its latent dynamics even though we did not use an explicit recurrent module, the overlapping sensor data and the inclusion of previous state in input create an implicit memory. The result is that the confidence intervals expand and contract in a gradual, believable manner as conditions worsen or improve, which is desirable for a certifiable system to justify increased uncertainty in degraded conditions.

4.6. Case Study: Multi-UAM Conflict Scenario

To demonstrate the system in action, we consider a synthetic conflict scenario: Two UAM vehicles approach an intersection of routes in a city at the same altitude. Vehicle A (our ego) must climb to avoid Vehicle B if on a collision course. In our simulation, both vehicles share ADS-B data, but Vehicle B’s GNSS is compromised meaning it reports incorrect position. Our fusion system on Vehicle A uses its own sensors to visually and via LiDAR detect Vehicle B’s actual position, cross-checking the faulty ADS-B/GNSS data. The Transformer successfully identifies the inconsistency, relying on the direct sensor observations to track B. It issues a conflict alert to the flight control with a recommended avoidance maneuver. Meanwhile, a more naive system that trusted ADS-B would not have seen the need for avoidance in time. This showcases how a rich sensor fusion (with AI) can enhance safety by not relying on any single input, a critical advantage in urban environments with unverified signals or potential spoofing. Throughout the scenario, the safety monitor confirmed that, even in the presence of ADS-B discrepancies, the fused state estimates consistently remained within safe operational bounds. This case study underscores the robustness and fault tolerance of the proposed architecture, bolstering its candidacy for real UAM operations. Future work will involve hardware flight tests on UAM platforms to validate the system under real-world conditions. A certifiable embedded computing platform (e.g., Mercury ROCK3 or Jetson AGX Xavier with DO-178C/DO-254 compliance) will be used to evaluate performance and safety under formal testing protocols. Hardware-in-the-loop simulation and field testing are under planning.

5. Discussion

5.1. Advantages of Transformer-Based Fusion

The results confirm that our Transformer-based architecture can significantly outperform traditional fusion in complex scenarios. The ability to learn cross-modal features means the system can handle situations that are difficult to model explicitly. For example, our model learned to infer building edges from LiDAR and camera to correct GPS multipath errors – something an EKF would struggle with because it has no concept of environmental context. This learned intelligence led to better situational awareness which is reflected in higher detection rates and lower error.

A notable advantage is seen in edge cases. When sensors give conflicting information, a classical filter often cannot resolve the conflict except by weighting one sensor over the other through fixed rules. Our model, by virtue of training on many examples, can learn patterns of reliability (in case if camera and LiDAR disagree on range, and it’s foggy, trust LiDAR more). This dynamic weighting is handled within the attention mechanism’s soft alignment. Indeed, attention weights in our experiments showed intuitive behavior – during GNSS loss during which vision/LiDAR tokens dominated. When GPS has strong signal and GNSS tokens had significant attention share with building caused multipath, the weight shifted momentarily towards vision until GPS stabilized.

5.2. Comparative to BART and Other Models

The baseline we term “BART-based” was essentially using a Transformer encoder (like BART’s encoder) on concatenated sensor data flattened into a sequence. Its performance was inferior to our model – mainly because BART’s architecture (while powerful in language) wasn’t tailored for multi-modal input structure. It lacked the latent bottleneck and cross-attention which allow efficient multimodal fusion. This underscores that not all Transformers are equal for sensor fusion: specialized designs (Perceiver IO, dual-perspective transformers, etc.) are needed to properly align different sensor domains. Our approach demonstrates the efficacy of such a specialized design in an aerospace context for the first time.

5.3. Certifiability and Safety Considerations

One of the central discussions is how close this system is to being certifiable under current regulations. As of 2025, no aviation authority has fully certified a deep learning model for flight, but progress is being made in defining the means of compliance. A series of Monte Carlo simulations was conducted to statistically validate the robustness of the proposed fusion architecture under varying sensor failure scenarios, ensuring certifiability under FAA-mandated safety thresholds. Our architecture proactively includes features to aid certifiability, determinism, traceability, redundancy, etc., as detailed. However, challenges remain:

Verification of Learning Components: We tested the network extensively in simulation (millions of frames, Monte Carlo variations). But DO-178C would typically also need requirements-based coverage. We had to derive implicit requirements for the network to correctly identify obstacles of size X at distance Y. We achieved 100% requirement coverage through testing. Structural coverage is trickier so we treated the network like source code and measured neuron activations, achieving near 100% coverage of nodes during our test suite. If any dead code (unused paths) was found, we either removed those neurons (network pruning) or added targeted tests. This approach, while unconventional, could satisfy an auditor when combined with robustness test results. In essence, we argue that our testing demonstrates the network is not a black box but a component that meets specified requirements with known boundaries.

Tool Qualification: Training was done in Python with PyTorch obviously that process is not certifiable. But the runtime model is a set of weights and an inference engine in C++ (which we developed to DO-178C level). We would need to qualify the code generation or ensure that the code running the network is verified. This remains an open point industry-wide. Our mitigation is the extensive testing of the runtime and perhaps using formal methods to verify certain safety properties of the network with recent research in formal verification of neural nets could be leveraged.

Human Acceptance: From a certification perspective, explainability is key. We provided some level of interpretability with attention weights and did scenario-based testing to show the system responds safely. This helps build a safety case. For example, if applying for certification, one would cite results like ours to show the system always transitions to safe behavior under X, Y, Z fault scenarios (we’d include those scenarios in a safety assessment per ARP4761). The concept of deterministic AI as discussed by AFuzion suggests that regulators might accept AI if surrounded by enough determinism and monitoring. Our design is very much in line with those suggestions: the safety monitor can be seen as an independent mitigation that ensures the AI never goes out of bounds. In essence, the AI proposes a solution which is then vetted – a two-layer safety approach.

We should also note that redundancy in AI is a developing idea. We implemented one network; another approach is to run two different networks (trained differently) and compare outputs for dissimilar redundancy. We did not do this due to computational load, but it’s a path forward for future work: one could, for example, train a second model using a different architecture (say, a smaller network or an expert system) and require agreement or perform a arbitration. This could potentially eliminate single points of learning failure.

5.4. Cybersecurity and Adversarial Defense

Since UAM systems may be vulnerable to spoofing and adversarial attacks, certification now also considers DO-326A (cybersecurity)[

4][

9]. Our model’s inherent sensor cross-validation provides some security as it’s harder to be threat to all sensors at once. However, an attacker could still present risk to multiple sensors (e.g. blinding camera and spoofing GPS together). Defense against such sophisticated attacks might require additional measures like secure sensors, redundancies. In our discussion, we highlight that deep fusion can enhance robustness to random faults or single-source attacks, but against a strategic adversary, we must still rely on system-level security (encryption, authentication of ADS-B, etc.) beyond the scope of the fusion algorithm itself.

7. Conclusion

We have presented a Transformer-based multimodal sensor fusion architecture for Urban Air Mobility, coupled with a certifiable hardware-software design. This system achieves robust real-time perception by integrating LiDAR, EO/IR cameras, GNSS, ADS-B, IMU, and radar data using a Perceiver IO-inspired model. Through extensive simulations, we showed that it outperforms traditional Kalman filter fusion and a baseline deep model, particularly in complex urban scenarios with sensor failures or misleading data. Importantly, we embedded the fusion algorithm in a deterministic execution framework with safety monitors and redundancy, aligning with DO-178C and DO-254 objectives for certification.

Our results indicate that advanced AI techniques can meet the stringent requirements of aerospace applications. The model maintained high accuracy and provided stable confidence estimates, giving trustable outputs to decision-making modules. The architecture’s resilience to sensor loss and adversarial inputs underscores its suitability for safety-critical operations. By addressing explainability and determinism, we move closer to making AI-driven sensor fusion certifiable – a milestone that could unlock autonomy in UAM and beyond.

Future work will involve hardware flight tests on a UAM platform to validate the system in real-world conditions. As a next step, we aim to implement this architecture on a certifiable embedded computing platform (e.g., Mercury ROCK3 or NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier) using DO-178C-compliant RTOS and DO-254 verified FPGA acceleration modules. Hardware-in-the-loop simulation, real-time sensor streaming, and field validation flights will form part of our next phase. The current simulation-based validation provides a rigorous and scalable foundation for advancing to certifiable deployment in operational UAM avionics. We also plan to engage with certification authorities to refine the compliance demonstration for this type of technology, potentially contributing to future guidance for certifying machine learning in aviation. The integration of formal verification for neural network components is another avenue to bolster confidence. Lastly, expanding the model’s training to cover more scenarios (night flights, varying weather) will further enhance its robustness and reliability.

In conclusion, this paper demonstrates a promising path to safe, certified autonomy in urban skies: combining the cutting-edge performance of Transformers with the proven safety engineering of avionics. As UAM vehicles begin to populate our cities, such sensor fusion architectures will be key to ensuring these vehicles operate with the required level of safety and reliability. The tools and approaches we developed can serve as a foundation for the next generation of certifiable AI systems in aerospace, bridging the gap between modern AI capabilities and the high assurance standards of aviation.