Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We provide a systematic analysis of sensor vulnerabilities in autonomous vehicles, with particular focus on the emerging DVS technology and its unique security characteristics.

- We implement and evaluate realistic attack scenarios in the CARLA simulator, demonstrating their impact on autonomous agent behavior and perception accuracy.

- We develop an effective anomaly detection system using the anomalib library that can identify sophisticated attacks on both RGB and DVS camera sensors [16].

- We propose a comprehensive defense framework that combines anomaly detection, sensor fusion, and potential human intervention to ensure resilient autonomous operation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Framework

2.1.1. CARLA Simulator

2.1.2. PCLA Framework

- Ability to deploy multiple autonomous driving agents with different architectures and training paradigms

- Independence from the Leaderboard codebase, allowing compatibility with the latest CARLA version

- Support for multiple vehicles with different autonomous agents operating simultaneously

2.1.3. Autonomous Driving Agent

- NEAT AIM-MT-2D: A neural attention-based end-to-end autonomous driving agent that processes RGB images and depth information to predict vehicle controls directly. We used the NEAT variant that incorporates depth information (neat_aim2ddepth), which enhances the agent’s ability to perceive the 3D structure of the environment and improves its performance in complex driving scenarios.

2.2. Sensor Configuration

- RGB Cameras: Front-facing RGB camera with 800×600 resolution and 100° field of view, mounted at position (1.3, 0.2, 2.3) relative to the vehicle center, providing visual input for the agent’s perception system.

- Dynamic Vision Sensor (DVS): Event-based camera with 800×600 resolution and 100° field of view, mounted at position (1.3, 0.0, 2.3), with positive and negative thresholds set to 0.3 to capture brightness changes in the scene with microsecond temporal resolution.

- Depth Camera: Depth sensing camera with 800×600 resolution and 100° field of view, aligned with the RGB camera position, providing per-pixel distance measurements for 3D scene understanding.

- LiDAR: 64-channel LiDAR sensor with 85m range, 600,000 points per second, and 10Hz rotation frequency, mounted at position (0.0, 0.0, 2.5), providing detailed 3D point cloud data of the surrounding environment.

- GPS and IMU: For localization and vehicle state estimation, enabling the agent to maintain awareness of its position and orientation within the environment.

2.3. Attack Implementation

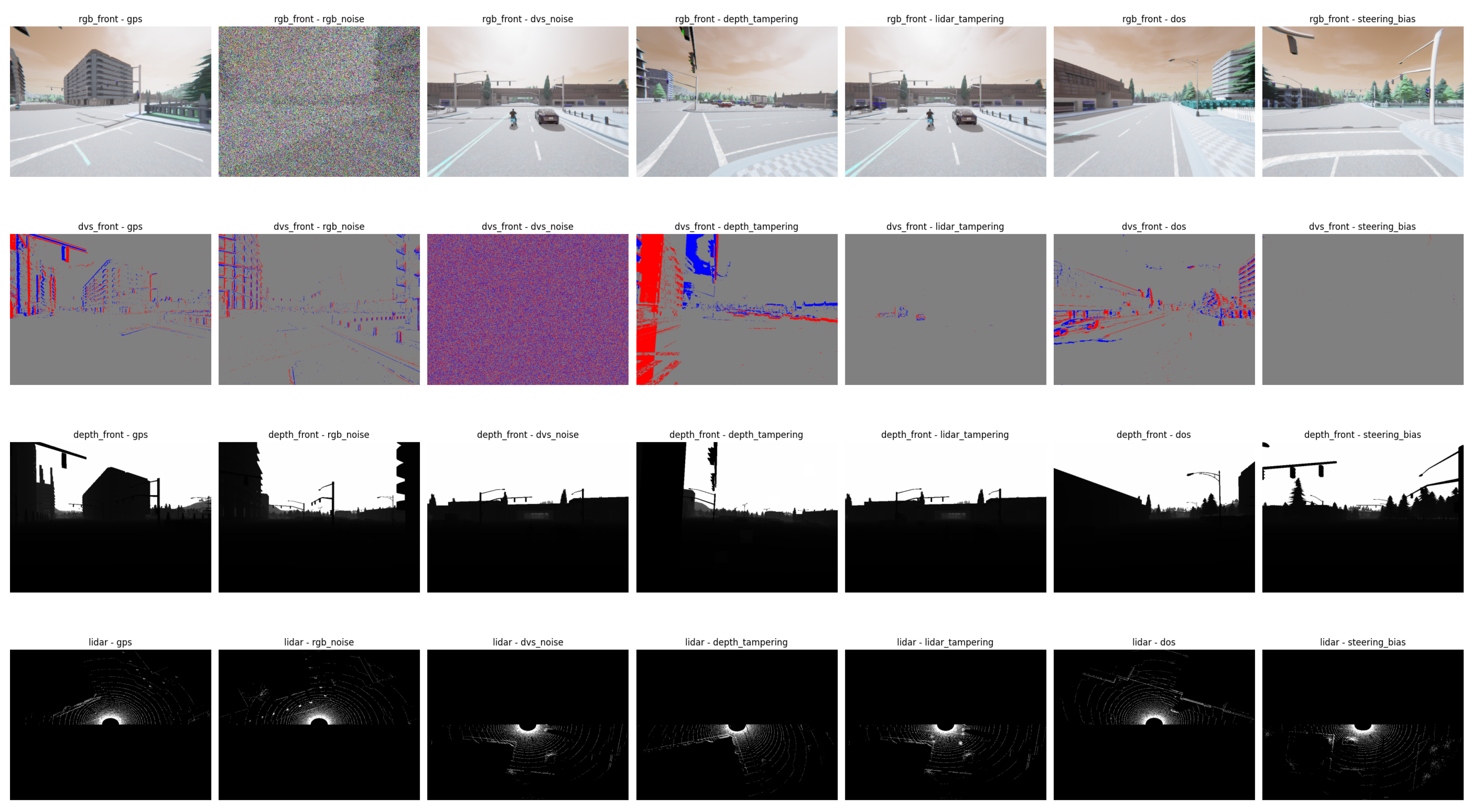

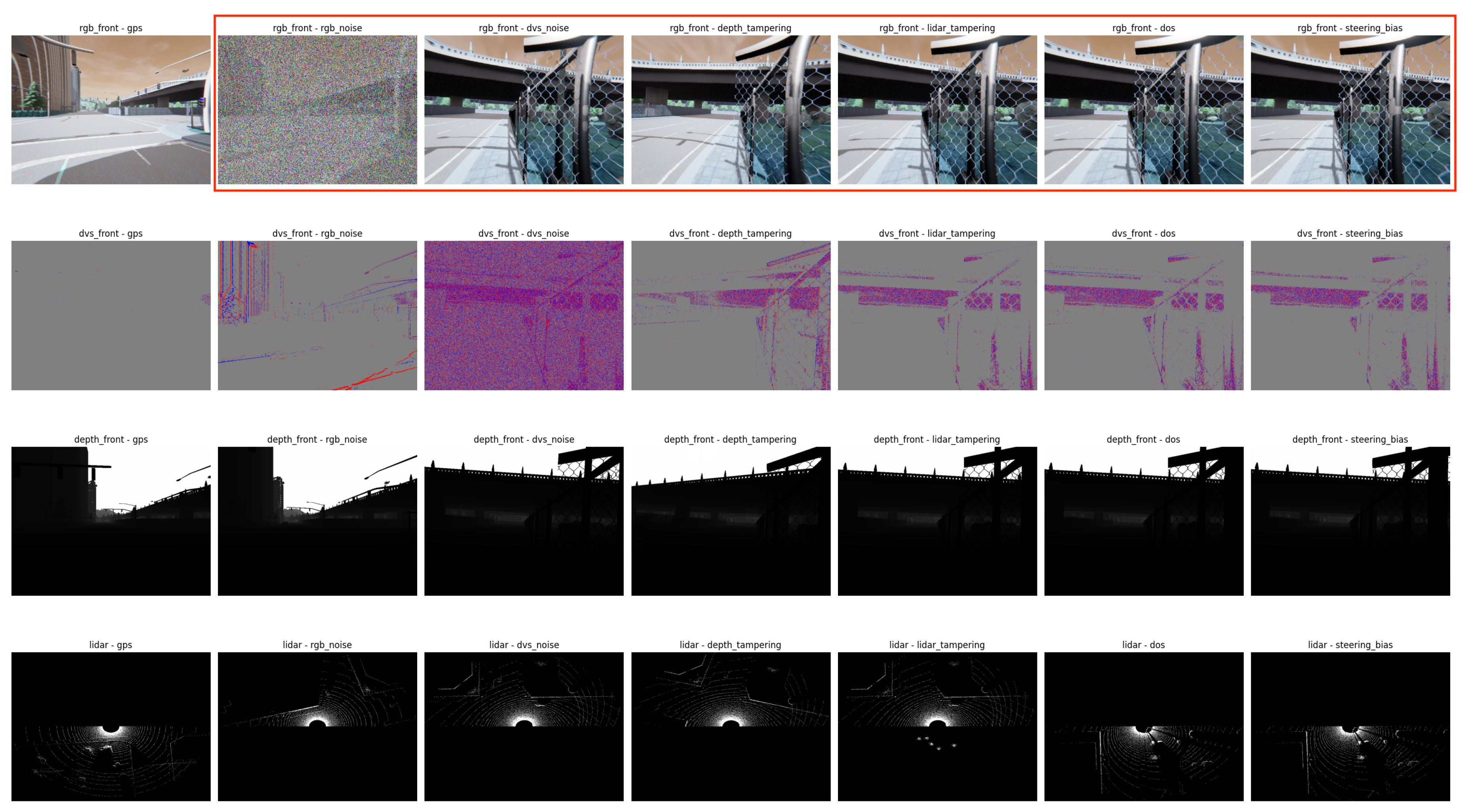

- RGB Camera Attacks, Salt-and-Pepper Noise: We implemented a high-density (80%) salt-and-pepper noise attack on RGB camera images, where random pixels were replaced with either black (0) or white (255) values with equal probability. This attack simulates severe sensor interference that could result from electromagnetic interference or hardware tampering.

- Dynamic Vision Sensor Attacks, Event Flooding: We implemented a noise injection attack that added a large number of spurious events (approximately 60% of the frame size) with random positions and polarities to the DVS output stream. This attack creates false motion perception that could confuse event-based perception algorithms and trigger unnecessary emergency responses.

- Depth Camera Attacks, Depth Map Tampering: We implemented a patch-based depth tampering attack that modified depth values in random regions of the depth map. The attack added 5 random patches of size 50×50 pixels with depth offsets ranging from 5 to 15 units, creating the illusion of obstacles closer or further than they actually are.

- LiDAR Attacks, Phantom Object Injection: We implemented a phantom object injection attack that added 5 clusters of points (100 points per cluster) to the LiDAR point cloud at random positions within a range of 5-15 meters in front of the vehicle. These phantom objects could trigger unnecessary braking or evasive maneuvers in the autonomous driving system.

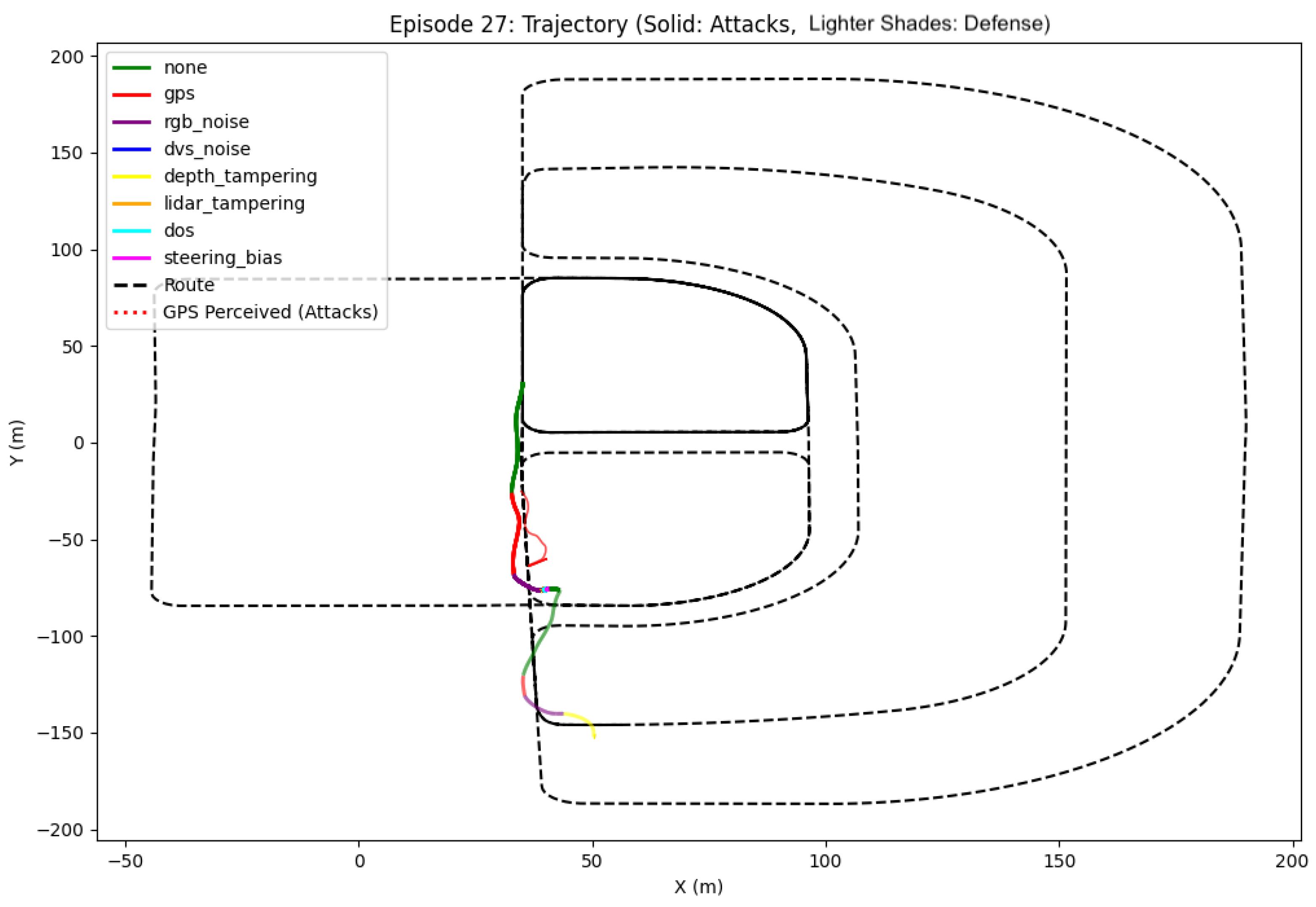

- GPS Spoofing Attacks, Position Manipulation: We implemented a GPS spoofing attack that maintains two separate location records: the actual position (vehicle._original_get_transform()) and the perceived position (vehicle.get_transform()). This allows us to analyze the discrepancy between the vehicle’s true and perceived locations during attacks. The attack creates a significant deviation between the reported and actual position, potentially causing the vehicle to make incorrect routing decisions.

- Denial of Service (DoS) Attacks, Sensor Rate Limiting: We implemented a DoS attack that targets the sensor update frequency by tracking sensor update timestamps (attack_state.last_sensor_update) and artificially restricting updates to a maximum of 20 Hz. This causes delayed or missed sensor readings that affect the vehicle’s perception and decision-making capabilities.

- Steering Bias Attacks, Control Manipulation: We implemented a steering bias attack that introduces systematic errors into the vehicle’s steering commands. The attack modifies the steering values in the control data stream, and its effects are measured through trajectory deviation analysis and steering angle distribution statistics.

2.4. Defense Integration

-

RGB Camera Defenses, Adaptive Median Filter: We implemented a decision-based adaptive median filter that dynamically adjusts its kernel size (3×3 to 7×7) based on the detected noise level. The filter specifically targets salt-and-pepper noise by:

- –

- Identifying potential noise pixels (values of 0 or 255)

- –

- Growing the filter window until valid median values are found

- –

- Preserving edge details by only replacing confirmed noise pixels

-

DVS Defenses, Event Stream Analysis: We implemented a two-stage defense mechanism:

- –

- Event count monitoring with a threshold of 5000 events per frame

- –

- Spatial clustering analysis using KD-trees to detect abnormally dense event clusters

- –

- Morphological operations (dilation) to smooth legitimate events while filtering noise

-

Depth Camera Defenses, Gradient-Based Tampering Detection: Our defense system includes:

- –

- Range limiting (0-100m) to filter physically impossible measurements

- –

- Sobel gradient analysis to detect unnatural depth discontinuities

- –

- Adaptive Gaussian smoothing based on detected tampering severity

-

LiDAR Defenses, Point Cloud Filtering: We implemented a comprehensive filtering pipeline:

- –

- Distance-based outlier removal (50m maximum range)

- –

- Density-based clustering to identify and remove phantom objects

- –

- Nearest neighbor analysis to detect unnaturally dense point clusters

-

Rate Limiting Defense, Sensor Update Monitoring: To prevent DoS attacks:

- –

- Tracking of sensor update timestamps

- –

- Implementation of rate limiting thresholds

- –

- Buffering mechanism to maintain consistent sensor data flow

2.5. Anomaly Detection System

2.5.1. EfficientAd Model Architecture

- A teacher network pre-trained on normal data that learns to extract robust features from sensor inputs

- A student network that attempts to mimic the teacher’s feature representations

- A discrepancy measurement module that quantifies the difference between teacher and student outputs

2.5.2. Training Methodology

- Data Collection: We collected sensor data from multiple driving scenarios without attacks to establish a baseline of normal operation.

-

Data Preprocessing: For sensor modality, appropriate preprocessing was applied:

- RGB and DVS data: Resized to 128×128 and normalized using ImageNet mean and standard deviation values (mean=[0.485, 0.456, 0.406], std=[0.229, 0.224, 0.225]).

- Model Training: The EfficientAd model was trained exclusively on normal data, learning to represent the distribution of normal sensor readings without exposure to attack examples.

2.6. Evaluation Methodology

2.6.1. Attack Impact Assessment

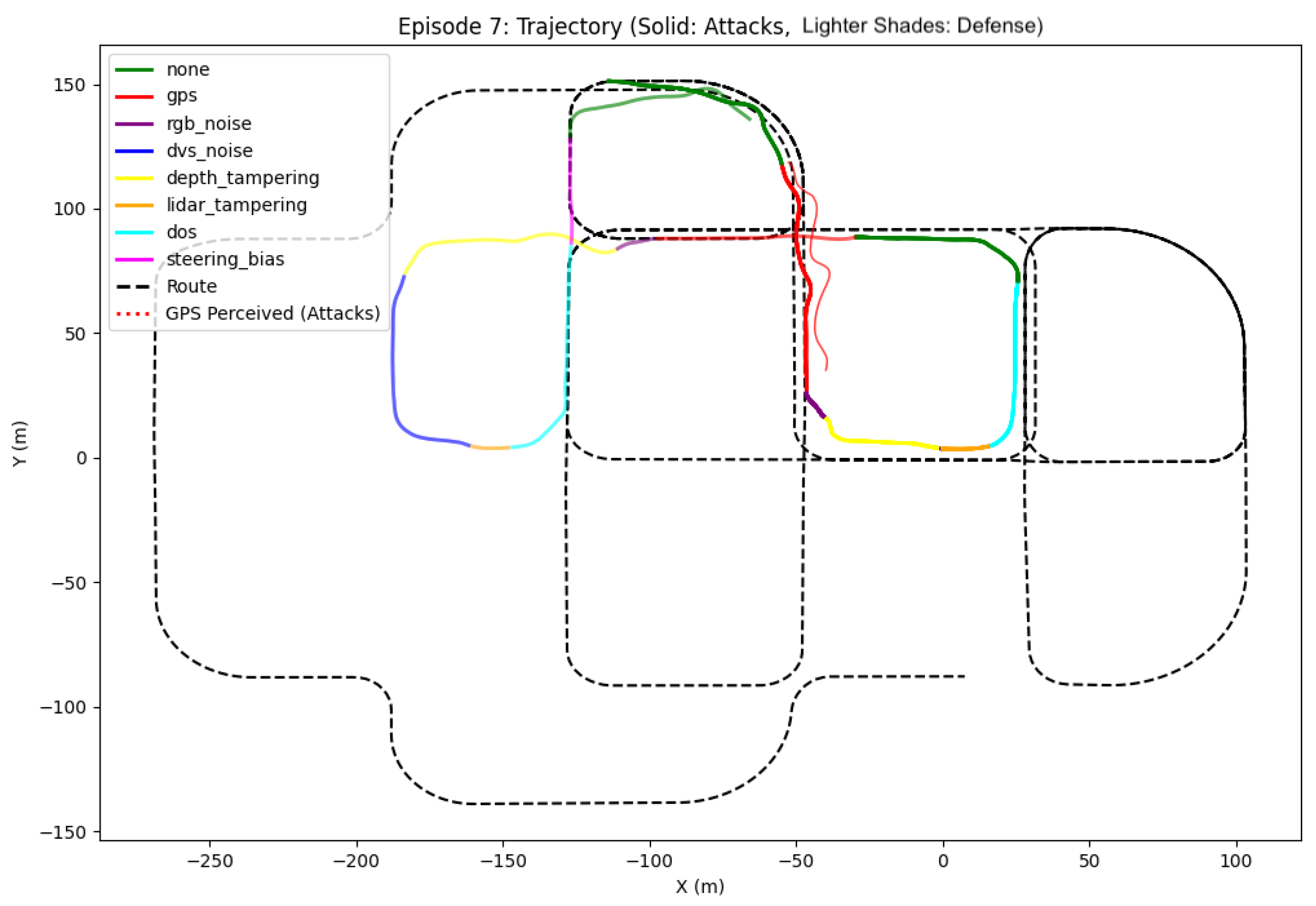

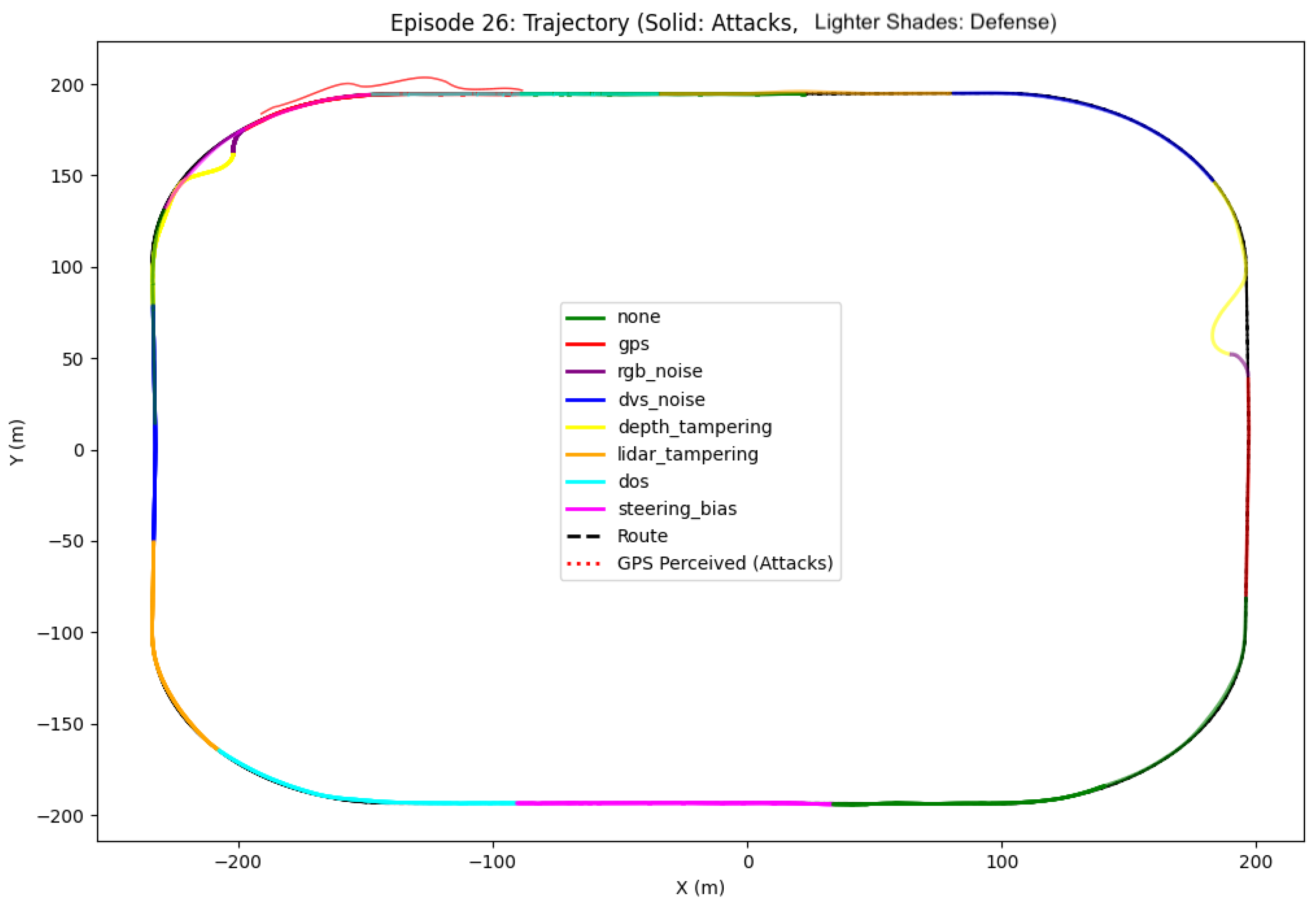

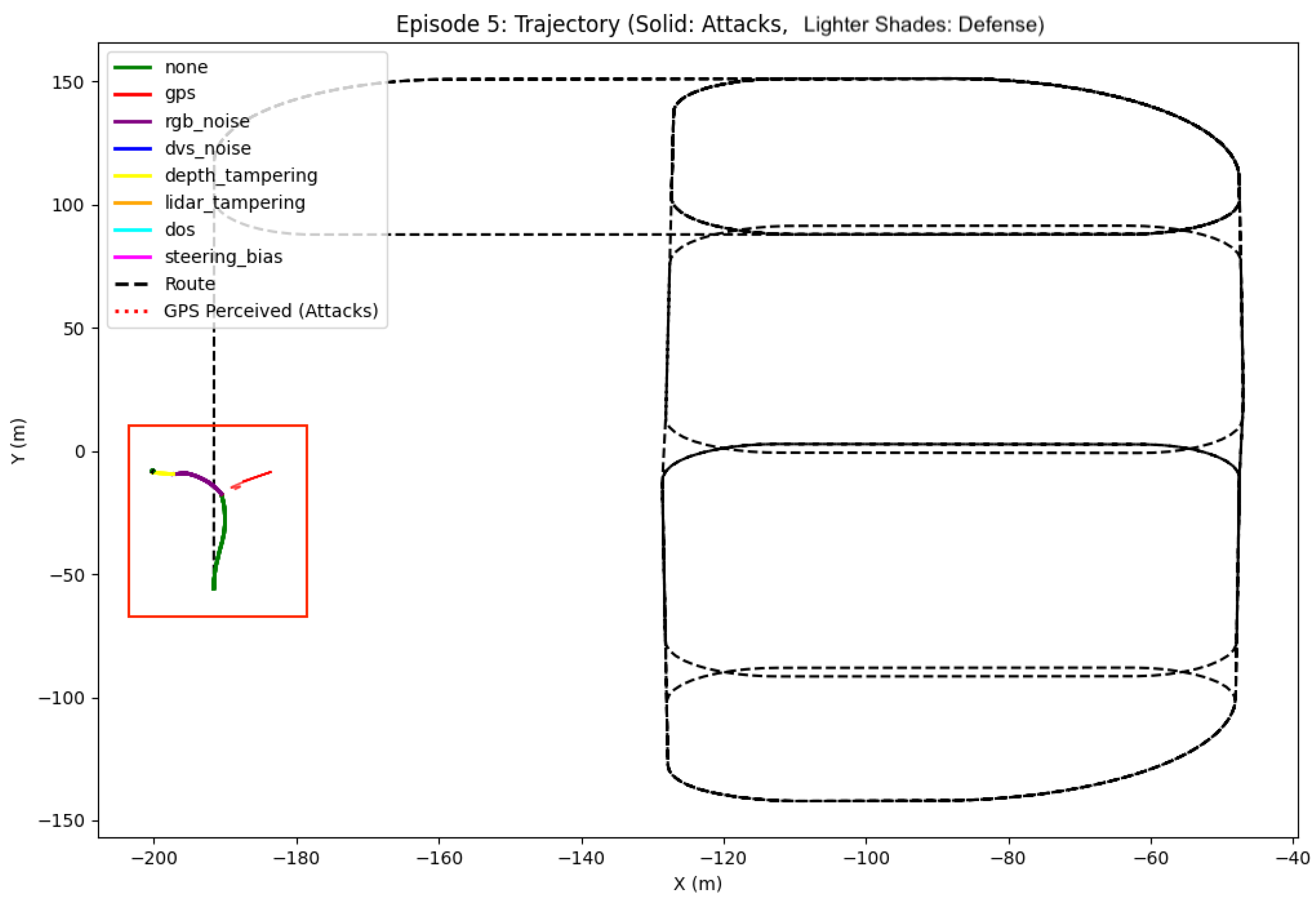

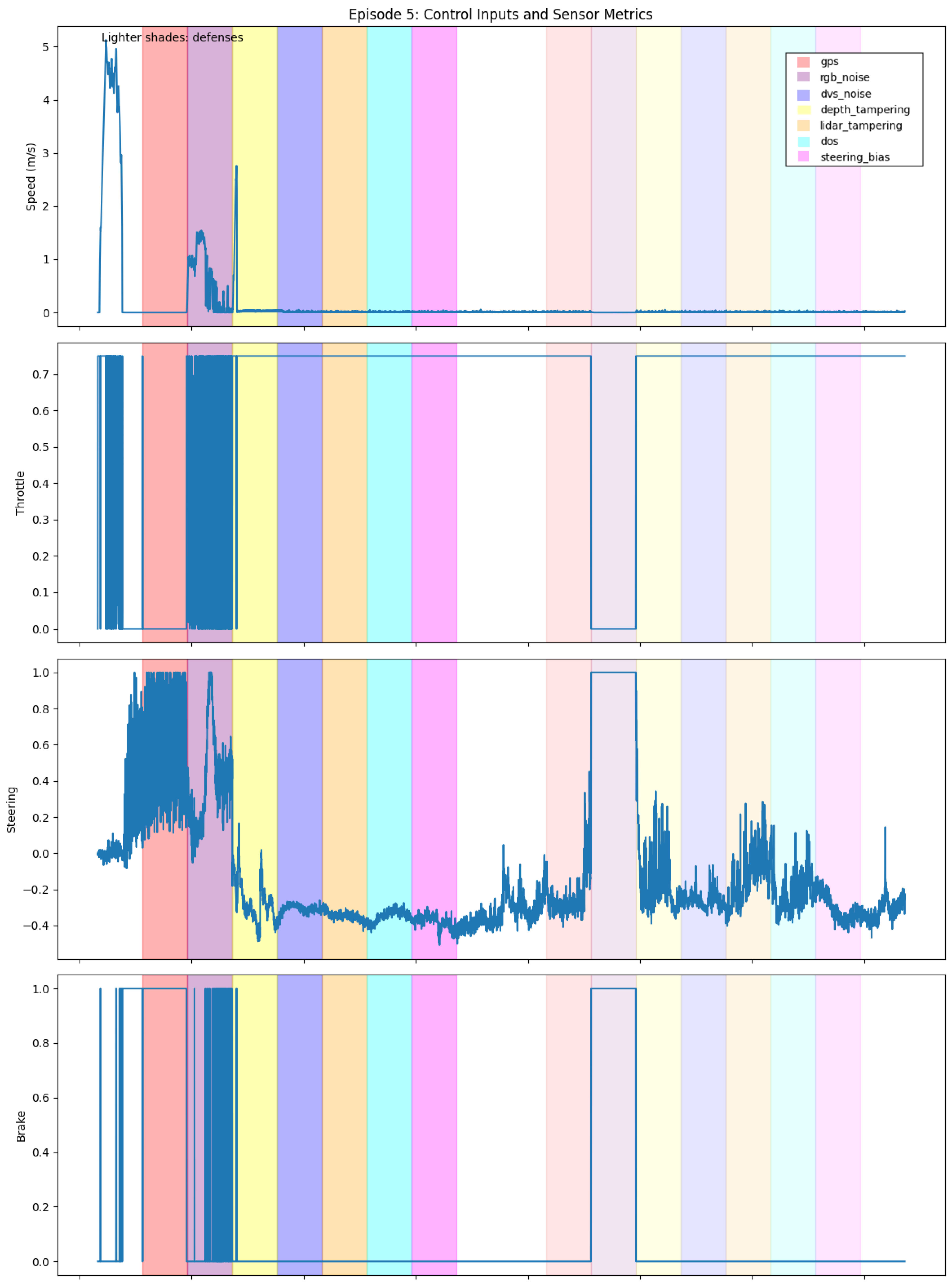

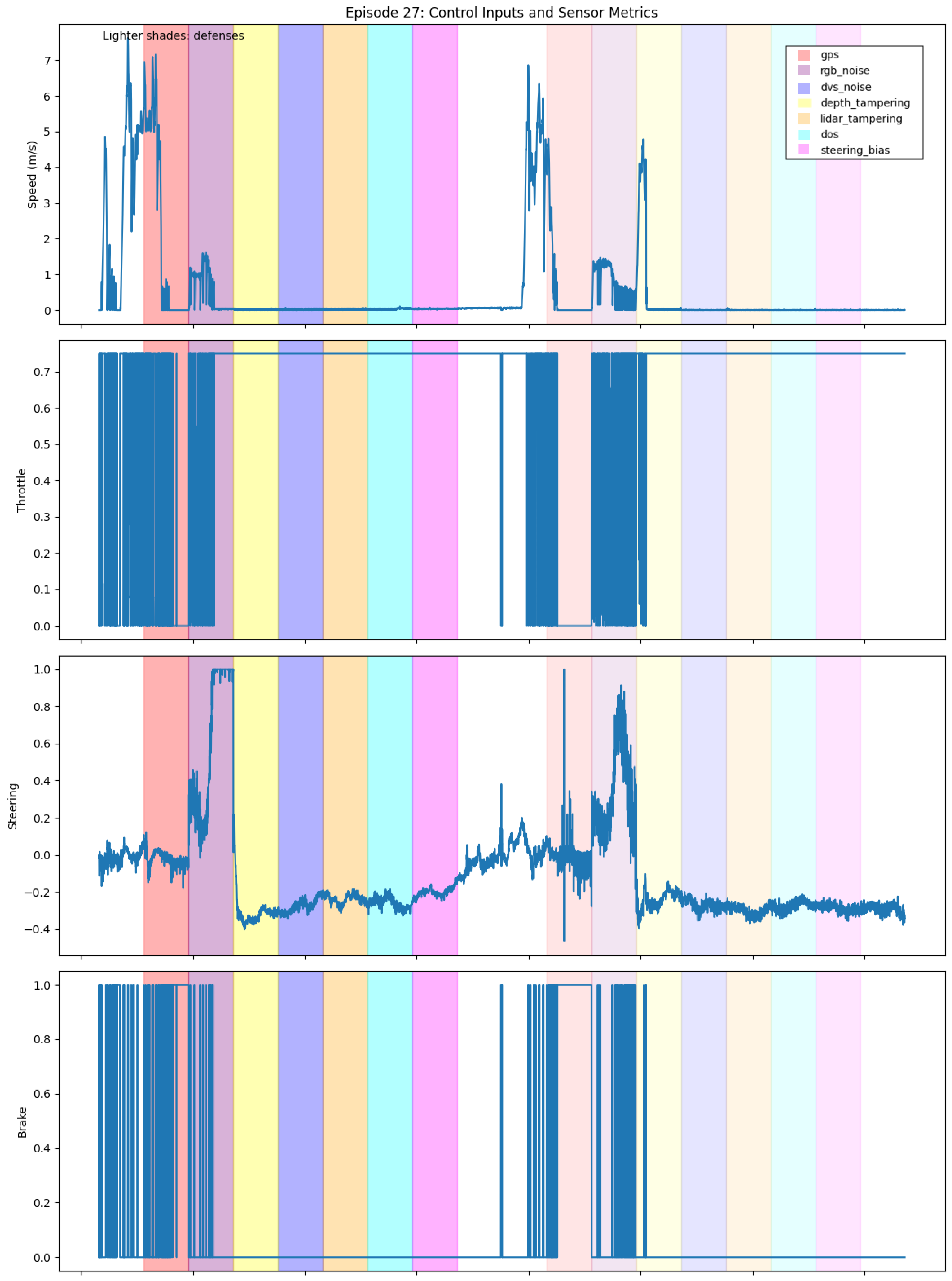

- Trajectory Analysis: We track and compare the vehicle’s actual trajectory against the planned route, calculating point-to-segment distances to measure route deviation. This analysis is particularly important for GPS spoofing attacks where perceived and actual positions may differ significantly.

- Control Stability: We analyze steering, throttle, and brake commands through detailed time-series analysis. For steering bias attacks, we perform statistical analysis of steering angle distributions to detect anomalous patterns.

-

Sensor Performance Metrics:

- –

- RGB Camera: Noise percentage measurements during salt-and-pepper attacks

- –

- DVS: Event count tracking to detect abnormal spikes in event generation

- –

- Depth Camera: Mean depth measurements to identify tampering

- –

- LiDAR: Point cloud density analysis to detect phantom objects

-

Defense Effectiveness: Comparison of performance metrics with and without defensive measures enabled, including:

- –

- Adaptive median filtering for RGB noise

- –

- Spatial clustering analysis for DVS event flooding

- –

- Gradient-based analysis for depth tampering

- –

- Density-based filtering for LiDAR attacks

- –

- Rate limiting for DoS attacks

2.6.2. Visualization and Analysis Tools

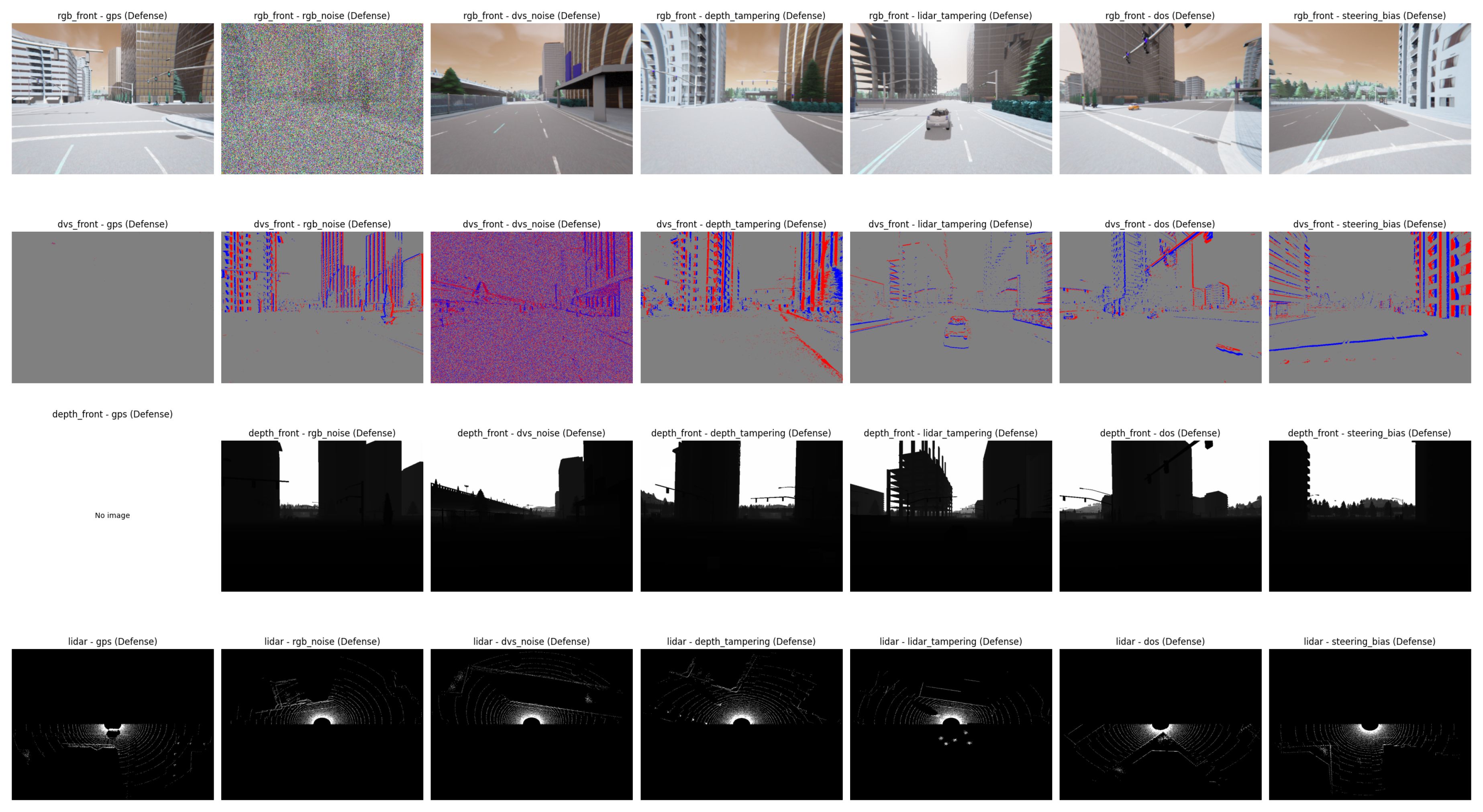

- Combined Video Generation: Synchronized display of multiple sensor feeds (RGB, DVS, depth, LiDAR) with attack state indicators

- Trajectory Plots: Visualization of actual vs. perceived trajectories during GPS spoofing

- Statistical Analysis: Histograms of steering distributions and sensor metrics under different attack conditions

2.6.3. Experimental Scenarios

- Urban Navigation: Complex urban environments with intersections, traffic lights, and other vehicles.

- Highway Driving: High-speed scenarios with lane changes and overtaking maneuvers.

- Dynamic Obstacles: Scenarios with pedestrians and other vehicles executing unpredictable maneuvers.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Cyberattacks on Autonomous Driving Performance

3.1.1. Completed Routes Under Attack

3.1.2. Route Failures and Crashes

3.2. Effectiveness of Defense Mechanisms

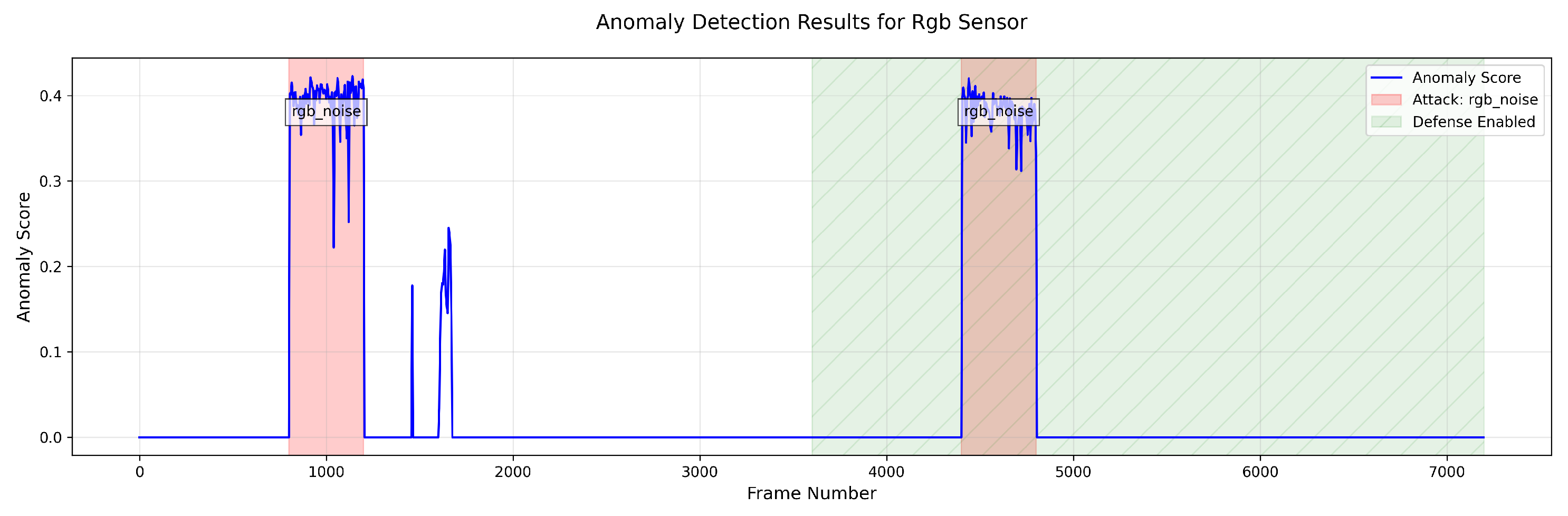

- RGB Camera Attacks: Our anomaly detection model for RGB cameras successfully identified attacks on the camera feed, but the subsequent filtering techniques showed limited effectiveness against sophisticated attacks. While some noise reduction was achieved, the filtered images often remained significantly compromised, resulting in continued trajectory deviations even with defenses active.

- Depth Sensor Attacks: The depth sensor anomaly detection system effectively detected anomalies in depth data, but defense mechanisms for depth sensor attacks demonstrated limited effectiveness against targeted attacks, with filtered depth maps still containing significant distortions that affected the vehicle’s perception capabilities.

- GPS Spoofing: Our GPS-specific anomaly detection and defense system successfully detected and mitigated GPS spoofing attacks by implementing plausibility checks and cross-checking with IMU data. This was our most effective defense, as it clearly identified spoofed GPS coordinates and prevented the vehicle from making unwarranted course corrections based on falsified location data.

- Steering Bias: The steering-specific anomaly detection system combined with rate limiting showed partial effectiveness in identifying malicious steering commands, but sophisticated attacks could still influence vehicle control in certain scenarios.

- Continuously monitor all sensor inputs for anomalies using our trained detection models

- When anomalies are detected, reduce reliance on AI models for driving decisions

- Transfer driving control to human operators for a safer experience when sensor integrity is compromised

- Alternatively, selectively shut down compromised sensors and cross-check with remaining functional sensors to maintain autonomous operation

3.3. Anomaly Detection Performance

3.3.1. RGB Camera Anomaly Detection

- Normal Operation: Mean anomaly score of 0.000000 with standard deviation of 0.000000, establishing a clear baseline for normal behavior.

- RGB Noise Attacks: Mean anomaly scores of 0.378064 (with defense) and 0.389462 (without defense), both significantly higher than normal operation. This demonstrates the model’s ability to reliably detect RGB camera attacks regardless of whether defenses are active.

- Our RGB camera anomaly detection model is specifically designed to detect anomalies in RGB camera data only and does not process data from other sensors.

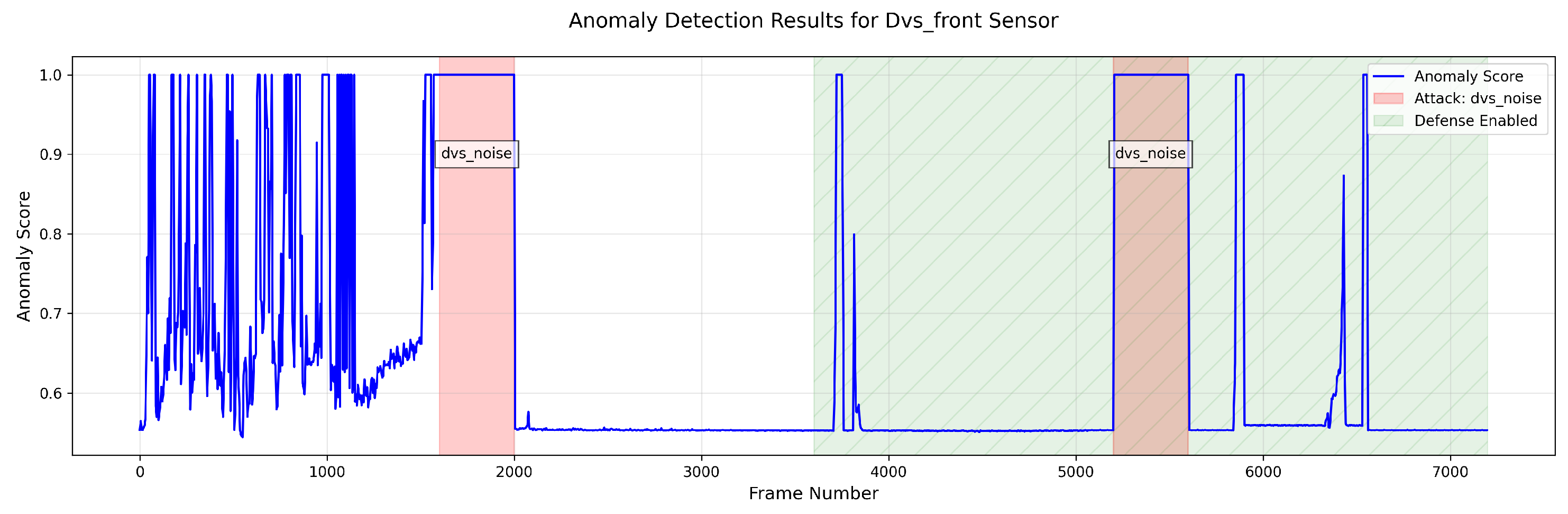

3.3.2. DVS Camera Anomaly Detection

- Normal Operation: Mean anomaly score of 0.608308 with standard deviation of 0.121466, establishing a baseline that reflects the inherent variability of event-based vision data.

- DVS Noise Attacks: Mean anomaly scores of 0.552093 (with defense) and 0.758073 (without defense). Interestingly, the score with defense is slightly lower than normal operation, while the score without defense is significantly higher. This suggests that our defense mechanisms not only mitigate the attack but also stabilize the event generation process.

- It’s important to note that our DVS anomaly detection model is specifically designed to detect anomalies in DVS sensor data only and does not process data from other sensors. Additionally, DVS cameras are currently used for research purposes only and are not integrated into the vehicle’s driving decision model.

3.4. Comparative Analysis of RGB and DVS Sensor Security

- Research Context: It is important to emphasize that DVS cameras in our study were used exclusively for research purposes and were not integrated into the vehicle’s driving decision model. The data collected from DVS sensors was analyzed separately from the main autonomous driving pipeline.

- Defense Effectiveness: Our defense mechanisms were evaluated separately for each sensor type. RGB cameras, which are actively used in the driving model, required more aggressive filtering that sometimes reduced image quality. DVS defenses were studied in isolation as a research component.

- Anomaly Detection: The anomaly detection models for both sensors were designed to work exclusively with their respective sensor data. The RGB model showed clearer separation between normal and attack conditions and directly impacted vehicle safety, while the DVS model’s patterns were analyzed purely for research insights.

- Future Potential: While not currently used for driving decisions, the complementary nature of RGB and DVS sensors suggests that sensor fusion approaches could potentially enhance security in future implementations.

| Sensor Type | Attack Type | Results Without Defense | Results With Defense |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB Camera | Salt-and-Pepper Noise (80%) | Severe trajectory deviations; vehicle weaving across lanes; crashes in some episodes | Limited effectiveness; 30–45% trajectory drift still present; filtered images remain compromised |

| Dynamic Vision Sensor (DVS) | Event Flooding (60% spurious events) | False motion perception; higher anomaly scores (0.76) | Limited effectiveness; anomaly detection detects attack phase; event filter still compromised; lower anomaly scores (0.55) |

| Depth Camera | Depth Map Tampering (random patches) | Misinterpreted obstacle distances; affected perception of road boundaries | Limited effectiveness; filtered depth maps still contain significant distortions |

| LiDAR | Phantom Object Injection (5 clusters) | Unnecessary braking; evasive maneuvers | Partial mitigation through point cloud filtering; density-based clustering removes some phantom objects |

| GPS | Position Manipulation | Significant deviation between reported and actual position; incorrect routing decisions | Highly effective mitigation; IMU cross-checking prevented course corrections based on falsified data |

| Sensor Update | Denial of Service (rate limiting) | Delayed/missed sensor readings; affected perception and decision-making | Partial mitigation through sensor update monitoring and buffering mechanisms |

| Control System | Steering Bias | Systematic errors in steering commands; trajectory deviation | Partial effectiveness; sophisticated attacks could still influence vehicle control |

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Autonomous Vehicle Security

4.2. Significance of Anomaly Detection Approach

4.3. Comparative Security of RGB and DVS Sensors

4.4. Limitations and Challenges

4.5. Future Research Directions

- Enhanced Anomaly Detection: Developing more sophisticated anomaly detection models that can identify subtle attacks while maintaining low false positive rates. This could include exploring deep learning architectures specifically designed for time-series sensor data and incorporating contextual information from multiple sensors.

- Sensor Fusion for Security: Investigating how data from complementary sensors (RGB, DVS, LiDAR, radar) can be fused not only for improved perception but also as a security mechanism. Inconsistencies between different sensor modalities could serve as indicators of potential attacks.

- Graceful Degradation: Designing autonomous systems that can gracefully degrade performance when attacks are detected, rather than failing catastrophically. This could involve developing fallback driving policies that rely on uncompromised sensors or implementing safe stop procedures.

- Human-in-the-Loop Security: Exploring how human operators could be effectively integrated into the security framework, particularly for remote monitoring and intervention when anomalies are detected. This raises important questions about interface design, situation awareness, and response time.

- DVS Integration: Further investigating the potential of DVS technology for enhancing autonomous vehicle security, including developing specialized perception algorithms that leverage the unique properties of event-based vision and exploring hybrid RGB-DVS architectures.

- Standardized Security Evaluation: Developing standardized benchmarks and evaluation methodologies for assessing the security of autonomous vehicle sensor systems, enabling more systematic comparison of different defense approaches.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AV | Autonomous Vehicle |

| CUDA | Compute Unified Device Architecture |

| DoS | Denial of Service |

| DVS | Dynamic Vision Sensors |

| EfficientAd | Efficient Anomaly Detection |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| NEAT | Neural Attention |

| PCLA | Pretrained CARLA Leaderboard Agent |

| RGB | Red Green Blue |

| VRAM | Video Random Access Memory |

References

- Giannaros, A.; Karras, A.; Theodorakopoulos, L.; Karras, C.; Kranias, P.; Schizas, N.; Kalogeratos, G.; Tsolis, D. Autonomous Vehicles: Sophisticated Attacks, Safety Issues, Challenges, Open Topics, Blockchain, and Future Directions. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2023, 3, 493–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhai, M.; Mazurek, S.; Caputa, J.; Argasiński, J.K.; Wielgosz, M. Spiking Neural Networks for Real-Time Pedestrian Street-Crossing Detection Using Dynamic Vision Sensors in Simulated Adverse Weather Conditions. Electronics 2024, 13, 4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Hong, J.-E. Reconstruction-Based Adversarial Attack Detection in Vision-Based Autonomous Driving Systems. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2023, 5, 1589–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guesmi, A.; Hanif, M.A.; Shafique, M. AdvRain: Adversarial Raindrops to Attack Camera-Based Smart Vision Systems. Information 2023, 14, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahima, K.T.Y.; Perera, A.; Anavatti, S.; Garratt, M. Exploring Adversarial Robustness of LiDAR Semantic Segmentation in Autonomous Driving. Sensors 2023, 23, 9579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Y. Wang et al., "EV-Gait: Event-Based Robust Gait Recognition Using Dynamic Vision Sensors," 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 2019, pp. 6351-6360. [CrossRef]

- Y. Suh et al., "A 1280×960 Dynamic Vision Sensor with a 4.95-μ Pixel Pitch and Motion Artifact Minimization," 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Seville, Spain, 2020, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, B.; Graca, R.; Delbruck, T. Experimental methods to predict dynamic vision sensor event camera performance. Opt. Eng. 2022, 61, 074103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Leutenegger, S.; Davison, A.J. Real-Time 3D Reconstruction and 6-DoF Tracking with an Event Camera. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2016.

- Sakhai, M.; Sithu, K.; Oke, M. K. S.; Mazurek, S.; Wielgosz, M. Evaluating Synthetic vs. Real Dynamic Vision Sensor Data for SNN-Based Object Classification. In Proceedings of the KU KDM 2025 Conference, 2025.

- K. Eykholt et al., "Robust Physical-World Attacks on Deep Learning Visual Classification," 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018, pp. 1625-1634. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jia, J.; Cong, G.; Na, M.; Xu, W. Adversarial Sensor Attack on LiDAR-Based Perception in Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS ’19), 2019.

- Sun, J.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Q. A.; Mao, Z. M. Towards Robust LiDAR-Based Perception in Autonomous Driving: General Black-Box Adversarial Sensor Attack and Countermeasures. In Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 20), 2020.

- Petit and S. E. Shladover, "Potential Cyberattacks on Automated Vehicles," IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2015, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 546-556, April 2015. [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, D., Scaramuzza, D. Low-latency automotive vision with event cameras. Nature 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bogdoll, D.; Hendl, J.; Zöllner, J. M. Anomaly Detection in Autonomous Driving: A Survey. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 2022.

- Kołomański, M., Sakhai, M., Nowak, J., Wielgosz, M. (2023). Towards End-to-End Chase in Urban Autonomous Driving Using Reinforcement Learning. In: Arai, K. (eds) Intelligent Systems and Applications. IntelliSys 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 544. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Sakhai, M., Wielgosz, M. (2024). Towards End-to-End Escape in Urban Autonomous Driving Using Reinforcement Learning. In: Arai, K. (eds) Intelligent Systems and Applications. IntelliSys 2023. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 823. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).