1. Introduction

Soybean (

Glycine max L.) is cultivated on approximately 139 million hectares worldwide, with an estimated production of 421 million tons. Brazil is the largest producer, accounting for 40% of the global output [

1]. The Brazilian soybean production for the 2024/25 season is projected at 168.3 million tons, representing nearly 50% of the country’s total grain production [

2].

Since 2003, with the official approval of Roundup Ready

® (RR) soybean cultivation in commercial areas, weed control in this crop has become relatively simplified. This led to a significant increase in the adoption of RR technology due to the ease of management, low cost, and high efficiency of glyphosate herbicide [

3]. However, the widespread and continuous use of glyphosate over several consecutive years, without rotation of modes of action or crops, has resulted in the selection of weed biotypes resistant or tolerant to this herbicide. These include species such as horseweed (

Conyza bonariensis,

C. canadensis and

C. sumatrensis), ryegrass (

Lolium multiflorum), sourgrass (

Digitaria insularis), wild poinsettia (

Euphorbia heterophylla), pigweed (

Amaranthus spp.), daflower (

Commelina spp.), and morning glories (

Ipomoea spp.), among others [

4,

5].

Weed resistance has become one of the major challenges in weed management. Current strategies to mitigate this issue include the use of crop residues on the soil surface, crop rotation, increased use of pre-emergence herbicides, employing herbicides with different modes of action, and tank mixing glyphosate with other products to improve weed control [

6,

7,

8].

In this context, the herbicide saflufenacil is an important tool for pre-plant desiccation in agricultural crops, particularly soybean. It has proven effective mainly against problematic dicotyledonous weeds, including those resistant to acetolactate synthase (ALS) inhibitors, 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) inhibitors, and auxin mimics [

9,

10]. In weeds with multiple resistance mechanisms, such as horseweed, saflufenacil has demonstrated control efficacy and reduced regrowth when tank mixed with glyphosate [

11,

12].

Saflufenacil belongs to the pyrimidinedione chemical family and acts as a contact herbicide by inhibiting the protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PROTOX) enzyme. This inhibition leads to the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX, which interferes with chlorophyll biosynthesis [

13,

14]. Saflufenacil is absorbed through leaves and roots, with translocation mainly via the xylem [

9]. Susceptible plants exhibit typical symptoms, especially on younger leaves, including chlorosis, wilting, and tissue necrosis caused by lipid peroxidation and membrane disruption, ultimately leading to cell death. These symptoms impair growth and often result in plant death [

15,

16].

Some herbicides, including saflufenacil, tend to leave residues that adhere to the internal surfaces of sprayer tanks and other equipment parts after application. This has frequently been identified as a source of contamination in subsequent sprayings [

17]. Many producers have only one sprayer, and if decontamination is inadequate, residues remaining in the tank can cause injury and reduce yields in susceptible crops [

18], particularly soybean.

Therefore, careful decontamination of sprayer tanks is essential, especially when the same equipment is used across susceptible crops. The application of selective post-emergence herbicides combined with sub-lethal doses of non-selective herbicides can cause phytotoxicity and reduce crop productivity [

19,

20]. For example, contamination of sprayer tanks with dicamba residues above 1.1 g a.i. ha⁻¹ applied to RR soybean during vegetative stages caused phytotoxicity and yield reduction [

18].

Saflufenacil is commonly applied pre-plant due to its excellent control of dicotyledonous weeds and registration for desiccation before soybean planting [

21]. However, post-emergence herbicide applications, especially glyphosate, can cause phytotoxicity symptoms in soybean if saflufenacil residues remain in the sprayer tank. Phytotoxic effects from sub-lethal saflufenacil residues are exacerbated by increasing doses and by synergistic effects when mixed with glyphosate [

11,

22,

23].

Some legumes, such as soybean, tolerate pre-emergence applications of up to 100 g ha⁻¹ saflufenacil [

24]. However, limited information exists regarding safe residue levels in sprayer tanks or the maximum saflufenacil dose soybean can tolerate post-emergence without significant phytotoxicity or yield loss.

Given the scarcity of data on soybean sensitivity to saflufenacil residues, especially from sprayer tank contamination, this study aimed to simulate potential injury caused by saflufenacil residues applied alone or combined with glyphosate in soybean cultivation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description, Location, and Treatments Used in the Experiment

The experiment was conducted at the experimental area of the Federal University of Fronteira Sul (UFFS), Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil (latitude 27°43'31" S, longitude 52°17'40" W, 650 m), from November 2020 to April 2021. Sowing was performed using no-till system with crop residue cover. The area was cultivated during the winter with a mixture of black oats, radish, and vetch, which was subsequently desiccated with glyphosate + sethoxydim (1335 + 108 g ha⁻¹) 20 days before soybean sowing, resulting in a dry biomass yield of 6.0 t ha⁻¹.

The soil is classified as Humic Red Latosol [

25], with the following chemical and physical properties: pH

water 5.6; organic matter 3.2%; phosphorus 9.7 mg dm⁻³; potassium 134.4 mg dm⁻³; aluminum 0.0 cmolc dm⁻³; calcium 6.7 cmolc dm⁻³; magnesium 3.1 cmolc dm⁻³; cation exchange capacity (CEC) 10.2 cmolc dm⁻³; CEC at pH 7.0 of 14.6 cmolc dm⁻³; H+Al 4.5 cmolc dm⁻³; base saturation 51%; and texture composed of 62% clay, 15% sand, and 23% silt.

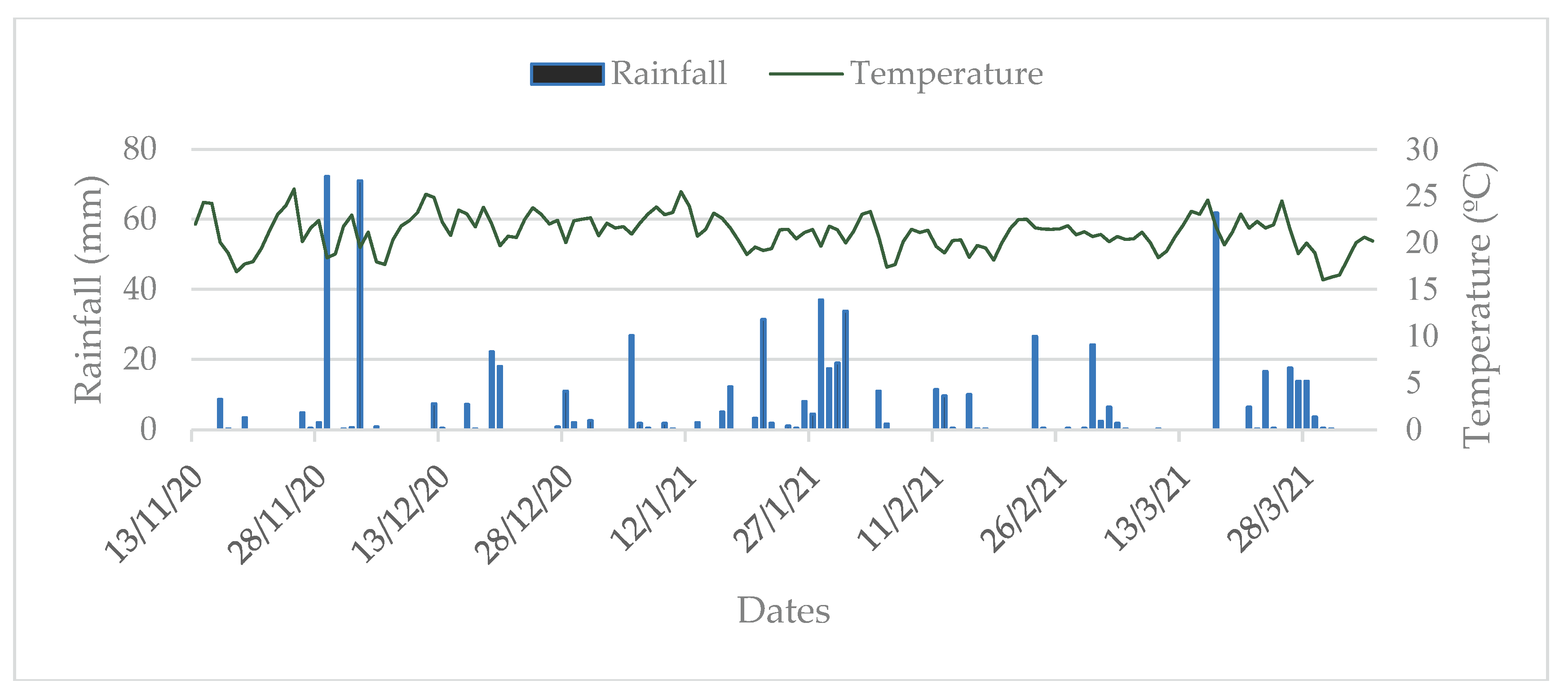

The predominant climate in the region, according to the Köppen classification, is Cfa: temperate climate with mild summers, evenly distributed rainfall, average temperature of the warmest month below 22ºC, annual precipitation between 1,100 and 2,000 mm, and frequent severe frosts occurring on average 10 to 25 days per year [

26]. Meteorological data, including precipitation (mm), mean temperature (ºC), and relative humidity (%) recorded during the experiment are shown in

Figure 1.

The experiment was arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications, comprising 18 treatments as detailed in

Table 1. Soil fertility was corrected according to technical recommendations for soybean cultivation [

28]. Fertilization in the sowing furrow consisted of 375 kg ha⁻¹ of N-P-K formulation 05-20-20. Soybean was sown at a row spacing of 0.50 m with a seeding density of 15.75 seeds per linear meter, resulting in approximately 315,000 seeds per hectare. The cultivar used was DM 5958, belonging to relative maturity group 5.8, with medium plant height and indeterminate growth habit.

Each experimental unit consisted of a 15 m² plot (5 m length × 3 m width) with six soybean rows. The useful area comprised the four central rows, excluding 1.0 m from the front and rear borders, totaling 6 m². Herbicide applications were performed using a CO₂-pressurized backpack sprayer equipped with four DG110.02 flat-fan nozzles, maintaining a constant pressure of 210 kPa and a travel speed of 3.6 km h⁻¹, delivering a spray volume of 150 L ha⁻¹.

Applications were carried out when soybean plants were at growth stages V3 to V4, 28 days after emergence. Environmental conditions at application were: 100% light intensity, air and soil temperatures of 33ºC and 28.3ºC respectively, relative humidity of 32%, and wind speed between 1.1 and 3.0 km h⁻¹. Emerging weeds in the experiment were controlled by manual hoeing whenever necessary.

2.2. Variables Evaluated

Phytotoxicity evaluations on soybean plants were conducted at 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 days after treatment (DAT). Phytotoxicity was scored on a percentage scale from 0% (no injury) to 100% (plant death), following the methodology described by Velini et al. [

29].

At 21 DAT, physiological parameters were measured, including internal leaf CO₂ concentration (Ci, µmol mol⁻¹), stomatal conductance (gS, mol m⁻² s⁻¹), photosynthetic rate (A, µmol m⁻² s⁻¹), transpiration rate (E, mol m⁻² s⁻¹), water use efficiency (WUE, mol CO₂ mol H₂O⁻¹), and carboxylation efficiency (CE, mol CO₂ m⁻² s⁻¹). WUE and CE were calculated as the ratios A/E and A/Ci, respectively. Measurements were taken on the middle third of the plants, specifically on the first fully expanded leaf. An infrared gas analyzer (IRGA), ADC LCA PRO model (Analytical Development Co. Ltd, Hoddesdon, UK), was used. Measurements were conducted between 8:00 and 11:00 a.m. to ensure homogeneous environmental conditions.

Prior to harvest, ten plants per experimental unit were evaluated for the number of pods per plant and grains per pod by direct counting. Soybean was harvested when grain moisture reached approximately 18%. After manual harvesting and threshing of a 6 m² area, thousand-grain weight (TGW, g) and grain yield (kg ha⁻¹) were determined. TGW was measured from eight samples of 100 grains each, weighed on an analytical balance. Grain moisture was standardized to 13% for yield calculations, which were extrapolated to kg ha⁻¹.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to normality and homogeneity of variance tests. After confirming normality of residuals, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using the F-test. When significant differences were detected, means were compared using the Scott-Knott test at p ≤ 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Sisvar software version 5.6 [

30].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phytotoxicity in Soybean Due to Application of Saflufenacil Alone or Combined with Glyphosate

Increasing doses of saflufenacil, whether applied alone or in combination with glyphosate, resulted in progressively more pronounced phytotoxicity symptoms in soybean plants (cultivar DM 5958 IPRO) across all evaluation periods from 7 to 35 days after treatment (DAT) (

Table 2). This phytotoxicity was especially notable when saflufenacil doses exceeded 4.38 g ha⁻¹ applied alone, or 2.17 g ha⁻¹ when combined with glyphosate.

Considering that the recommended saflufenacil dose for desiccation in soybean ranges from 35 to 140 g of commercial product per hectare (approximately 24.50 to 98.00 g ha⁻¹ of active ingredient), the doses evaluated here ranged from 1.09 to 70 g ha⁻¹. Even at 8.7 g ha⁻¹, visible phytotoxicity symptoms (55%) were observed at 7 DAT, highlighting the high potential of saflufenacil to cause damage to soybean at very low concentrations. These findings align with Barbieri et al. [

30], who reported significant phytotoxicity in soybean grown on soils with low retention capacity at doses near 9.86 g ha⁻¹—only 14% of the recommended label dose. This supports the hypothesis that herbicide residues from poorly cleaned sprayer tanks can trigger significant phytotoxic effects even without intentional application to soybean.

The observed phytotoxicity is attributed to saflufenacil’s mode of action as a protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPO) inhibitor. Additionally, saflufenacil can disrupt the plant’s hormonal balance by interfering with abscisic acid and ethylene synthesis, compromising defense mechanisms and stress tolerance. It may also impair the integrity of electron transport chains in chloroplasts and mitochondria, reducing photosynthetic efficiency and causing accumulation of toxic compounds in tissues. Soybean is particularly vulnerable due to its limited capacity to metabolize and detoxify the herbicide, leading to accumulation of the active compound in young, more sensitive tissues. Even sublethal doses can impair early growth, reduce active leaf area, and interfere with reproductive development [

13,

31]. Symptoms include membrane disruption and tissue necrosis, manifesting as chlorosis, wilting, and necrosis, especially in young leaves [

16].

The combination with glyphosate intensified these effects, likely due to the synergistic action of the two herbicides: while saflufenacil induces oxidative stress, glyphosate inhibits synthesis of essential antioxidant compounds [

32]. This synergy explains the greater severity of phytotoxicity observed when both herbicides were tank-mixed, even when saflufenacil was applied at low doses in the mixture. Similar results were reported by Yin et al. [

31] and Salomão et al. [

33] who demonstrated that PPO inhibitors can cause significant damage to soybean, particularly when combined with herbicides affecting complementary metabolic pathways such as glyphosate.

Glyphosate applied alone caused no phytotoxicity in soybean, showing statistical equivalence to the weed-free control throughout the evaluation period (

Table 2). This is attributed to the presence of the glyphosate resistance gene (Roundup Ready

®) in the soybean cultivar used, which confers high selectivity by enabling the plant to metabolize or tolerate the herbicide without visual injury symptoms. This result aligns with Guo et al. [

34], who demonstrated high glyphosate selectivity in RR soybean across different phenological stages, confirming the safety of glyphosate use in genetically modified cultivars resistant to this herbicide.

The results indicate that isolated applications of saflufenacil up to 2.17 g ha⁻¹ caused mild phytotoxicity symptoms in soybean, statistically higher only than glyphosate alone and the weed-free control up to 14 DAT. From 14 DAT onwards, no significant differences were observed among these treatments, and by 35 DAT, injury levels were below 4% (

Table 2). This pattern is likely due to rapid herbicide degradation in soil and the soybean’s ability to recover from initial damage caused by low saflufenacil doses [

30]. Furthermore, at sublethal isolated doses, herbicide availability in plant tissues is lower, reducing oxidative stress intensity and allowing effective physiological repair mechanisms to promote recovery over time [

35,

36].

Acceptable phytotoxicity levels in soybean vary depending on herbicide, applied dose, crop phenological stage, environmental conditions, and presence of tank mixtures with other products such as adjuvants or foliar fertilizers [

37]. Generally, low phytotoxicity levels (10–20% visual leaf injury) are tolerated provided they do not significantly affect crop development or yield [

38]. In this context, symptoms observed with up to 2.17 g ha⁻¹ (a.i.) saflufenacil applied alone fall within agronomically acceptable selectivity standards for soybean.

Over the period from 7 to 35 DAT, soybean plants showed progressive recovery from phytotoxicity symptoms, especially at the lower isolated saflufenacil doses (

Table 2). This recovery likely results from activation of physiological detoxification and cellular repair mechanisms, as well as herbicide degradation in soil and plant tissues [

39]. Although glyphosate mixtures caused initially more severe injury, symptoms also diminished over time due to compound metabolism and foliar tissue regeneration. Recovery was less pronounced in mixtures, possibly due to herbicide synergy that more severely impairs the plant’s antioxidant systems [

32]. These findings underscore that soybean selectivity to herbicide treatments depends on dose, mixture type, application conditions, and soil and climatic factors.

In summary the results demonstrate that saflufenacil, even at doses well below label recommendations, can cause phytotoxicity in soybean, especially when combined with glyphosate due to synergistic herbicide interactions. However, symptom severity decreased over time, particularly at lower doses and in isolated applications, indicating the crop’s capacity for recovery. These findings highlight the importance of proper dose management, mixture formulation, and equipment cleaning to minimize injury and ensure soybean selectivity when using combined herbicides.

3.2. Effects of Saflufenacil and Glyphosate, Applied Alone or in Tank Mix, on Soybean Physiology

The physiological parameters of soybean cultivar DM 5958 IPRO were significantly affected by saflufenacil doses, with reductions observed in internal CO₂ concentration (Ci), stomatal conductance (g

S), photosynthetic rate (

A), water use efficiency (WUE), and carboxylation efficiency (CE), indicating impaired carbon assimilation and photosynthetic efficiency (

Table 3). In contrast, the transpiration rate (

E) was not influenced by the treatments, which may be related to partial maintenance of stomatal opening as a mechanism for water and thermal regulation. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that PPO-inhibiting herbicides like saflufenacil can compromise photosynthetic function and increase oxidative stress in sensitive plants [

14,

40,

41], directly affecting physiological efficiency even without significantly altering transpiration.

Soybean plants treated with saflufenacil, both alone and in combination with glyphosate, exhibited reduced Ci at certain doses (alone: 4.38–35 g ha⁻¹; tank mix: 2.17, 52.5, and 70 g ha⁻¹;

Table 3). Since saflufenacil impairs photosynthesis, lower CO₂ uptake can hinder energy production and plant growth [

42,

43]. According to Hungria et al. [

42], reductions in photosynthetic and transpiration rates after herbicide application can be explained by damage to mesophyll cells and disruption of stomatal function, impairing CO₂ fixation and energy production.

In this study, water use efficiency (WUE) was reduced in soybean plants treated with saflufenacil, both alone and mixed with glyphosate (

Table 3). This decline reflects a lower capacity of the plant to fix carbon per unit of water transpired, indicating impaired CO₂ assimilation under herbicide stress. Similar results were reported by Ribeiro et al. [

43], who observed reduced water use and photosynthetic efficiency in plants under herbicide stress, and by Takano et al. [

13], who demonstrated that the combination of glyphosate and PPO inhibitors more intensely compromises soybean physiological mechanisms.

Overall, the combination of saflufenacil and glyphosate caused significant negative effects on key physiological variables in soybean, as shown in

Table 3. Reductions in photosynthetic rate, CO₂ uptake, transpiration, and water use efficiency ultimately hinder plant growth and development, directly affecting grain yield [

34,

42,

44]. These effects suggest that the interaction between these herbicides can induce combined physiological stress, limiting soybean’s ability to efficiently utilize resources.

3.3. Impact of Saflufenacil and Glyphosate, Applied Alone or in Combination, on Soybean Yield Components

The results of this study demonstrate that glyphosate applied alone provided the best performance for soybean yield components, including number of pods per plant (NPP), number of grains per plant (NGP), thousand-grain weight (TGW), and grain yield (GY), even surpassing the weed-free control in TGW and GY (

Table 4). This superior performance can be attributed to the high selectivity of glyphosate for soybean and its efficacy in weed control, resulting in a less competitive environment and optimal crop development. Additionally, at appropriate doses, glyphosate can induce hormetic effects, stimulating plant growth and optimizing physiological processes [

45]. Similar findings were reported by Krenchinski et al. [

45], who observed that doses between 45 and 180 g ha⁻¹ were safe and induced hormesis in both conventional and RR soybean cultivars, especially when applied as seed treatments, resulting in increased growth and biomass accumulation. These results reinforce the potential of glyphosate, when properly managed, not only as a herbicide but also as a positive growth regulator in RR soybean.

Soybean yield components showed significant variation in response to saflufenacil treatments, whether applied alone or in combination with glyphosate, with all values below those of the weed-free control (

Table 4). These data suggest that the intensity of early-stage phytotoxicity may have compromised vegetative development, directly impacting the formation and retention of reproductive structures. This hypothesis is supported by Miller et al. [

40], who demonstrated that damage from saflufenacil during early soybean development reduces the plant’s recovery capacity, negatively affecting physiological and morphological variables throughout the cycle, with direct consequences for yield. Thus, proper management of herbicide dose and combinations is essential to ensure crop selectivity and preserve yield potential.

Regarding grain yield (GY), a proportional reduction was observed with increasing saflufenacil doses, both alone and in combination with glyphosate (

Table 4). Glyphosate alone resulted in the highest yield among all treatments, even surpassing the weed-free control. This superior performance may be due to the fact that manual weeding, while effective in removing weeds, can damage soybean roots and allow regrowth after rainfall or incomplete cleaning in the sowing row. In contrast, glyphosate provides more effective and lasting weed control, reducing early competition and supporting optimal crop development. Similar results have been reported by authors who found higher yields in transgenic soybean under chemical weed control with glyphosate compared to manual weeding, due to reduced weed interference and greater operational efficiency [

23].

Glyphosate not only controlled weeds effectively but also did not cause phytotoxicity in soybean throughout the evaluation period (7–35 DAT;

Table 2), explaining the higher grain yield for this treatment. Several studies have shown that glyphosate does not harm soybean, providing a favorable environment for growth and development without negatively affecting yield [

13,

43,

46].

The reduction in soybean grain yield was most pronounced in plots treated with higher saflufenacil doses, both alone and in combination with glyphosate (

Table 4). This effect can be attributed to increased phytotoxicity at higher herbicide doses, which compromises early crop development. Furthermore, physiological damage from saflufenacil directly affects the production of photoassimilates, negatively impacting grain filling and, consequently, final yield. Similar findings were reported by Conte et al. [

47], who showed that compounds with high oxidative stress potential, such as PPO inhibitors, can interfere with essential physiological processes, hindering plant growth and productivity.

Glyphosate alone increased soybean grain yield by 9.65% compared to the average yield of the weed-free control, saflufenacil alone (1.09 and 2.17 g ha⁻¹), and the glyphosate + saflufenacil (1440 + 1.09 g ha⁻¹) mixture, which were the only treatments with yields close to glyphosate alone (

Table 4). Glyphosate application resulted in approximately 54% higher grain yield compared to the average of higher saflufenacil doses (4.38, 8.75, 17.50, 35, 52.50, and 70.00 g ha⁻¹) or tank-mixed glyphosate + saflufenacil (1440 + 2.17 to 1440 + 70.00 g ha⁻¹) (

Table 4). The reduction in average grain yield is associated with the high phytotoxicity levels caused by saflufenacil, even at low doses [

47]. These physiological parameters directly impact soybean growth and development, and consequently, grain yield [

48].

Saflufenacil applied at doses up to 2.17 g ha⁻¹ alone and up to 1.09 g ha⁻¹ when combined with glyphosate did not result in significant reductions in soybean grain yield, showing results similar to or even greater than the weed-free control (

Table 4). These findings indicate that soybean is tolerant to low doses of saflufenacil without compromising yield performance. This is particularly relevant in cases of accidental contamination from sprayer tank residues, where small amounts of herbicide may be unintentionally applied to the crop.

Despite the risk, residual doses of saflufenacil within these limits do not cause significant yield losses, reinforcing the importance of dose management for selective weed control. Furthermore, soybean tolerance to low saflufenacil doses was confirmed by Dilliott et al. [

46], who demonstrated that exposure to reduced concentrations of the herbicide does not significantly affect yield parameters, highlighting the physiological safety margin of soybean to such residues.

The results show that glyphosate applied alone was the only herbicide that did not cause phytotoxicity (

Table 2), had minimal negative effects on physiological variables, and did not damage yield components compared to saflufenacil, whether applied alone or in combination. Thus, even small amounts of saflufenacil can cause significant injury to soybean, with doses above 1.09 g ha⁻¹ already resulting in substantial yield losses. Proper cleaning of sprayer tanks to avoid saflufenacil residues from previous desiccation applications is essential to prevent problems in sensitive crops such as soybean.

5. Conclusions

This study is the first in Brazil to simulate and evaluate the effects of saflufenacil residues on soybeans when proper tank cleaning is not performed after desiccation applications of this herbicide and before post-emergence applications in soybean crops. Recently, numerous reports from Brazilian farmers have highlighted problems related to saflufenacil residues in spray tanks, resulting in significant yield losses in soybean fields. This situation has raised concerns within the scientific community, prompting further investigations into the issue. Therefore, it can be summarized (ou concluded) that:

1. Increasing doses of saflufenacil, applied alone or in combination with glyphosate above 2.17 g ha⁻¹, caused the most severe phytotoxicity symptoms in soybean cultivar DM 5958 IPRO.

2. Glyphosate applied alone showed no phytotoxicity, performing similarly to the weed-free control.

3. Saflufenacil applied alone at doses up to 2.17 g ha⁻¹ caused less than 25% phytotoxicity and resulted in soybean grain yields comparable to the weed-free control.

4. All doses of saflufenacil applied in tank mixtures with glyphosate caused high levels of phytotoxicity, which reflected in significantly reduced soybean grain yields.

5. The highest soybean grain yield was achieved with glyphosate applied alone, even surpassing the weed-free control.

6. Soybean can tolerate saflufenacil applied alone up to 2.17 g ha⁻¹ or up to 1.09 g ha⁻¹ when combined with glyphosate without experiencing severe phytotoxicity, physiological damage, or significant yield losses.

7. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to avoid herbicide applications—especially saflufenacil—when sprayer tanks contain any residual herbicide to prevent crop injury and yield reduction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-G., L-T. and R.-J.T.; methodology, L.-T. and F.-B.O.; software, G.-F.P. validation, G.-F.P., O.-A.D. and A.-D.R.A.; formal analysis, E.-B.G.; investigation, L.-T.; resources, L.-G.; data curation, G.-F.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.-J.T.; writing—review and editing, L.-G.; visualization, F.-B.O.; supervision, A.-D.R.A. and E.-B.G.; project administration, G.-F.P., O.-A.D.; funding acquisition, L.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq/Universal, grant number 403457/2023-8), the Research Support Foundation of Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS, grant number 24/2551-0001003-3), the Federal University of Fronteira Sul (UFFS, grant number PES-2024-0282) and the Studies and Projects Financing Agency (FINEP, grant number 0257/22).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

L Galon is thankful to the CNPq/PQ (process n. 312652/2023-2) for his fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- USDA-United States Department of Agriculture. Available online: https://www.usda.gov. (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- CONAB-Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento. Monitoring the Brazilian Grain Harvest. Available online: https://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/graos (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Adegas, F.S.; Correia, N.M.; Silva, A.F.; Concenço, G.; Gazziero, D.L.P.; Dalazen, G. Glyphosate-resistant (GR) soybean and corn in Brazil: past, present, and future. Adv. Weed. Sci. 2022, 40, e0202200102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holkem, A.S.; Silva, A.L.; Bianchi, M.A.; Corassa, G.; Ulguim, A.R. Weed management in Roundup Ready® corn and soybean in Southern Brazil: survey of consultants’ perception. Adv. Weed. Sci. 2022, e020220111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heap, I. The International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database [Internet]. Available from: http://www.weedscience.org. (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Liu, X.; Merchant, A.; Xiang, S.; Zong, T.; Zhou, X.; Bai, L. Managing herbicide resistance in China. Weed. Sci. 2021, 69, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreja, F.H.; Inman, M.D.; Jordan, D.L.; Vann, M.; Jennings, K.M.; Leon, R.G. Effect of cotton herbicide programs on weed population trajectories and frequency of glyphosate-resistant Amaranthus palmeri. Weed Sci. 2022, 70, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamego, F.P.; Nachtigall, J.R.; Machado, Y.M.S.; Langer, C.O.; Polino, R.C.; Bastiani, M.O. Amaranthus hybridus resistance to glyphosate: detection, mechanisms involved and alternatives for integrated management. Adv. Weed. Sci. 2024, 42, e020240046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavichioli, B.G.; Barbieri, G.F.; Pigatto, C.S.; Leães, G.P.; Kruse, N.D.; Ulguim, A.R. Control and translocation of saflufenacil in fleabane (Conyza spp.) according to plant integrity. Rev Fac Nac Agro Medellín. 2021, 74, 9523–9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreira, M.L.; Côrrea, F.R.; Silva, N.F.; Cavalcante, W.S.S.; Ribeiro, D.F.; Rodrigues, E. [Herbicides with potential for desiccation of pre-sowing areas of soybean crops]. Braz J of Sci. 2023, 2, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalazen, G.; Kruse, N.D.; Machado, S.L.O.; Balbinot, A. Synergism in the combination of glyphosate and saflufenacil for the control of horseweed]. Pesqui Agropecu Trop. 2015, 45, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, N.M. Management and development of fleabane plants in central Brazil. Planta Daninha. 2020, 38, e020238215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, H.K.; Oliveira Jr., R. S.; Constantin, J.; Osipe, J.B.; Alonso, D.G.; Pagnoncelli, F. Biotypes of Conyza sumatrensis resistant to glyphosate and ALS-inhibiting herbicides. Planta Daninha. 2013, 31, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Song, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Hu, D.; Song, R. Design and synthesis of novel PPO-inhibiting pyrimidinedione derivatives safed towards cotton. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 193, 105449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnica, V.C.; Jhala, A.J.; Harveson, R.M.; Giesler, L.J. Impact assessment of residual soil-applied pre-emergence herbicides on the incidence of soybean seedling diseases under field conditions. Crop Prot. 2022, 158, e105987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, H.H.; Soares, G.D.D.; Dias-Pereira, J.; Silva, L.C.; Machado, V.M. Impact of safufenacil and glyphosate based herbicides on the morphoanatomical and development of Enterolobium contortisiliquum (Vell.) Morong (Fabaceae): New insights into a non-target tropical tree species. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 31, 61254–61269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, C.L.; Robert, E.; Nurse, R.E.; Cowbrough, M.; Peter, H.; Sikkema, P.H. How long can a herbicide remain in the spray tank without losing efficacy? Crop Prot 2009, 28, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, N.; Nurse, R.E.; Sikkema, P.H. Response of glyphosate-resistant soybean to dicamba spray tank contamination during vegetative and reproductive growth stages. Can. J. Plant. Sci. 2016, 96, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, G.S.; Vieira, B.C.; Ynfante, R.S.; Santana, T.M.; Moraes, J.G.; Golus, J.A.; et al. Tank contamination and simulated drift effects of dicamba-containing formulations on soybean cultivars. Agrosyst. Geosci. Environ. 2020, 3, e20065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvaca, I.; Knezevic, S.; Scott, J.; Osipitan, O.A. Growth and yield losses of Roundup Ready soybean as influenced by micro-rates of 2,4-D. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2021, 10, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAPA/AGROFIT. Plant health agrotsystems - Open Consultation. [Internet]. Available from: http://agrofit.agricultura.gov.br/agrofit_cons/principal_agrofit_cons. (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Budd, C.M.; Soltani, N.; Robinson, D.E.; Hooker, D.C.; Miller, R.T.; Sikkema, P.H. Glyphosate-resistant horseweed (Conyza canadensis) dose response to saflufenacil, saflufenacil plus glyphosate, and metribuzin plus saflufenacil plus glyphosate in soybean. Weed Sci. 2016, 64, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galon, L.; Konzen, A.; Bagnara, M.A.M.; Brunetto, L.; Aspiazú, I.; Silva, A.M.L.; Brandler, D.; Piazetta, H.V.P.; Radüns, A.L.; Perin, G.F. Interference and threshold level of Sida rhombifolia in transgenic soybean cultivars. Rev Fac Cienc Agr. 2022, 54, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, N.; Shropshire, C.; Sikkema, P.H. Sensitivity of leguminous crops to saflufenacil. Weed Technol. 2017, 24, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streck, E.V.; Kampf, N.; Dalmolin, R.S.D.; Klamt, E.; Nascimento, P.C.; Giasson, E.; Pinto, L.F.S. Soils of Rio Grande do Sul. 3rd ed. Emater/RS-Ascar, BR: Porto Alegre/RS/BR, 2018, 252 pp. In Portuguese.

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, TA. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INMET - National Institute of Meteorology. Climatological data. Available online: https://portal.inmet.gov.br. (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- CQFS-RS/SC—Comissão de Química e Fertilidade do Solo. Liming and Fertilization Manual for the States of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina, 11rd ed., Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo—Núcleo Regional Sul, BR: Porto Alegre, RS, BR, 2016, 376 pp. In Portuguese.

- Velini, E.D.; Osipe, R.; Gazziero, D. L. P. Procedures for the establishment, evaluation, and analysis of experiments with herbicides. SBCPD/BR: Londrina/PR/BR, 1995, 42 pp. In Portuguese.

- Barbieri, G.F.; Pigatto, C.S.; Leães, G.P.; Kruse, N.D.; Agostinetto, D.; da Rosa Ulguim, A. Physicochemical properties of soil and rates of saflufenacil in emergence and growth of soybean. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2021, 61, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin K, Wu H, Zhang Y. Efficient and practical synthesis of saflufenacil. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2023, 55, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valença, D.C.; Lelis, D.C.C.; Pinho, C.F.; Bezerra, A.N.M.; Ferreira, M.A.; Junqueira, N.E.G.; Macrae, A.; Medici, L.O.; Reinert, F.; Silva, B.O. Changes in leaf blade morphology and anatomy caused by clomazone and saflufenacil in Setaria viridis, a model C4 plant. S Afr J Bot. 2020, 135, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomão, H.M.; Trezzi, M.M.; Viecelli, M.; Pagnocelli Junior, F.D.B.; Patel, F.; Damo, L.; Frizzon, G. Weed management with pre-emergent herbicides in soybean crops. Commun Plant Sci. 2021, 1, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.F.; Hong, H.L.; Han, J.N.; Zhang, L.J.; Liu, Z.X.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, L.J. Development and identification of glyphosate-tolerant transgenic soybean via direct selection with glyphosate. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.M.; Owen, M.D.K. Herbicide-resistant crops: Utilities and limitations for herbicide-resistant weed management. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2011, 59, 5819–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Evans, R.; Singh, B. Herbicidal inhibitors of amino acid biosynthesis and herbicide-tolerant crops. J. Amino Acids. 2006, 30, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCown, S.; Barber, T.; Norsworthy, J.K. Response of non–dicamba-resistant soybean to dicamba as influenced by growth stage and herbicide rate. Weed Technol. 2018, 32, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.J.P.; Magalhães, T.B.; Ovejero, R.F.L.; Palhano, M.G. Phytotoxicity of low doses of dicamba when sprayed in pre-emergence on non-tolerant soybean. Rev. Ciênc. Agrovet. 2022, 21, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Nelson, K.A.; Singh, G.; Udawatta, R.P. Cover crop impacts water quality in a tile-terraced no-till field with corn-soybean rotation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 360, e108794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.T.; Soltani, N.; Robinson, D.E.; Kraus, T.E.; Sikkema, P.H. Soybean (Glycine max) cultivar tolerance to saflufenacil. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 92, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. E, Geist, M.L.; Pereira, J.P.M.; Schedenffeldt, B.F.; Nunes, F.A.; da Silva, P.V.; Dupas, E.; Mauad, M.; Monquero, P.A.; Medeiros, E.S. Selectivity of post-emergence herbicides and foliar fertilizer in soybean crop. Rev Ciênc Agrovet. 2022, 21, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Mendes, I.C.; Nakatani, A.S.; Reis Junior, FB, Morais, J.Z.; Oliveira, M.C.N. de; Fernandes, M.F. Effects of the glyphosate-resistance gene and herbicides on soybean: Field trials monitoring biological nitrogen fixation and yield. Field Crops Res. 2014, 158, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V.H.V.; Maia, L.S.G.; Arneson, N.J.; Oliveira, M.C.; Read, H.W.; Ané, J.M.; Santos, J.B.; Werle, R. Influence of pre-emergence herbicides on soybean development, root nodulation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Crop Prot. 2021, 144, 105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, Z.A.; Jhala, A.J. Weed control and crop safety in sulfonylurea/glyphosate-resistant soybean. Can. J. Plant. Sci. 2020, 100, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenchinski, F.H.; Costa, R.N.; Pereira, V.G.C.; Bevilaqua, N.C.; Cruz, R.A.; Velini, E.D.; Carbonari, C.A. Glyphosate hormesis induced by treatment via seed stimulates the growth and biomass accumulation in soybean seedlings. Sci Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilliott, M.; Soltani, N.; Hooker, D.C.; Robinson, D.E.; Sikkema, P.H. The addition of saflufenacil to glyphosate plus dicamba improves glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane (Erigeron canadensis L.). J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, F.M.; Cestonaro, L.V.; Piton, Y.V.; Guimarães, N.; Garcia, S.C.; Silva, D.D.; et al. Toxicity of pesticides widely applied on soybean cultivation: Synergistic effects of fipronil, glyphosate and imidacloprid in HepG2 cells. Tox Vitr. 2022, 84, 105446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapado, L.P.; Kölpin, F.U.G.; Zeyer, S.; Anders, U.; Piccard, L.; Porri, A.; Asher, S. Complementary activity of trifludimoxazin and saflufenacil when used in combination for postemergence and residual weed control. Weed Sci. 2024, 73, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

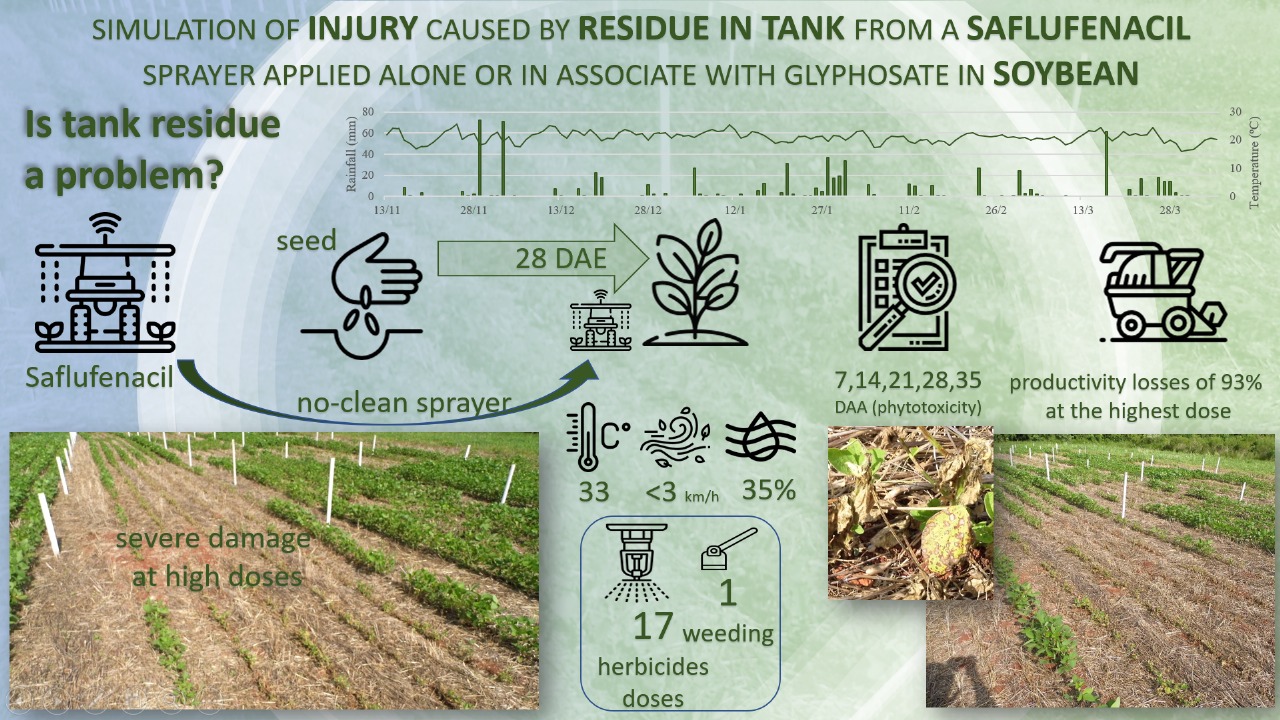

Figure 1.

Precipitation (mm), average temperature (ºC), and relative air humidity (%) during the experimental period from November 2020 to April 2021. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil. Source: INMET [

27].

Figure 1.

Precipitation (mm), average temperature (ºC), and relative air humidity (%) during the experimental period from November 2020 to April 2021. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil. Source: INMET [

27].

Table 1.

Treatment description. Treatments, doses, and adjuvants used in the 2020/21 experiment. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil.

Table 1.

Treatment description. Treatments, doses, and adjuvants used in the 2020/21 experiment. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil.

| Treatment |

Dose $$$(g ha⁻¹) |

Dose $$$(L or kg ha⁻¹) |

Adjuvant $$$(0.5% v/v) |

| Weed-free control |

--- |

--- |

--- |

| Glyphosate |

1440 |

3.000 |

--- |

| Saflufenacil |

1.09 |

0.0016 |

Assist |

| Saflufenacil |

2.17 |

0.0031 |

Assist |

| Saflufenacil |

4.38 |

0.00625 |

Assist |

| Saflufenacil |

8.75 |

0.0125 |

Assist |

| Saflufenacil |

17.50 |

0.0250 |

Assist |

| Saflufenacil |

35.00 |

0.0500 |

Assist |

| Saflufenacil |

52.50 |

0.0750 |

Assist |

| Saflufenacil |

70.00 |

0.1000 |

Assist |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 1.09 |

3.00 + 0.0160 |

Assist |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 2.17 |

3.00 + 0.0031 |

Assist |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 4.38 |

3.00 + 0.0625 |

Assist |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 8.75 |

3.00 + 0.0125 |

Assist |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 17.50 |

3.00 + 0.0250 |

Assist |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 35.00 |

3.00 + 0.0500 |

Assist |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 52.50 |

3.00 + 0.0750 |

Assist |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 70.00 |

3.00 + 0.1000 |

Assist |

Table 2.

Phytotoxicity. Phytotoxicity (%) caused by saflufenacil doses applied alone or in combination with glyphosate in soybean cultivar DM 5958 IPRO during the 2020/21 growing season. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil.

Table 2.

Phytotoxicity. Phytotoxicity (%) caused by saflufenacil doses applied alone or in combination with glyphosate in soybean cultivar DM 5958 IPRO during the 2020/21 growing season. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil.

| Treatment |

Dose$$$(g ha⁻¹) |

Phytotoxicity (%) |

| 7 DAT1

|

14 DAT |

21 DAT |

28 DAT |

35 DAT |

| Weed-free control |

--- |

0.00 e2

|

0.00 e |

0.00 d |

0.00 d |

0.00 d |

| Glyphosate |

1440 |

0.00 e |

0.00 e |

0.00 d |

0.00 d |

0.00 d |

| Saflufenacil |

1.09 |

16.25 d |

12.50 d |

7.50 d |

5.00 d |

3.75 d |

| Saflufenacil |

2.17 |

23.25 d |

17.00 d |

10.00 d |

6.25 d |

2.50 d |

| Saflufenacil |

4.38 |

36.25 c |

28.75 d |

22.50 c |

20.00 c |

17.50 c |

| Saflufenacil |

8.75 |

55.00 b |

50.00 c |

46.25 b |

45.00 b |

38.75 b |

| Saflufenacil |

17.50 |

76.25 a |

65.00 b |

58.75 b |

56.25 b |

48.75 b |

| Saflufenacil |

35.00 |

80.00 a |

73.75 a |

67.50 a |

67.50 a |

65.00 a |

| Saflufenacil |

52.50 |

81.50 a |

76.25 a |

75.00 a |

81.25 a |

79.50 a |

| Saflufenacil |

70.00 |

94.00 a |

90.00 a |

87.75 a |

90.00 a |

85.00 a |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 1.09 |

45.00 c |

40.00 c |

32.50 c |

28.75 c |

21.25 c |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 2.17 |

47.50 c |

43.75 c |

40.00 b |

37.00 c |

32.50 c |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 4.38 |

68.75 b |

61.25 b |

51.25 b |

47.50 b |

40.00 b |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 8.75 |

68.75 b |

61.25 b |

55.00 b |

48.75 b |

43.75 b |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 17.50 |

70.00 b |

63.75 b |

58.75 b |

57.50 b |

51.25 b |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 35.00 |

76.25 a |

61.25 b |

56.25 b |

55.00 b |

50.00 b |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 52.50 |

82.50 a |

77.00 a |

67.50 a |

73.75 a |

71.25 a |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 70.00 |

83.25 a |

79.50 a |

75.00 a |

73.75 a |

73.25 a |

| Mean average |

--- |

55.74 |

50.06 |

45.08 |

44.07 |

40.22 |

| C.V.3 (%) |

--- |

21.13 |

21.11 |

24.57 |

27.80 |

30.13 |

Table 3.

Physiological variables. Internal CO₂ concentration (Ci, µmol mol⁻¹), stomatal conductance (gS, mol m⁻² s⁻¹), photosynthetic rate (A, µmol m⁻² s⁻¹), transpiration rate (E, mol m⁻² s⁻¹), water use efficiency (WUE, mol CO₂ mol H₂O⁻¹), and carboxylation efficiency (CE, mol CO₂ m⁻² s⁻¹) of soybean cultivar DM 5958 IPRO under different doses of saflufenacil, applied alone or combined with glyphosate, during the 2020/21 growing season. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil.

Table 3.

Physiological variables. Internal CO₂ concentration (Ci, µmol mol⁻¹), stomatal conductance (gS, mol m⁻² s⁻¹), photosynthetic rate (A, µmol m⁻² s⁻¹), transpiration rate (E, mol m⁻² s⁻¹), water use efficiency (WUE, mol CO₂ mol H₂O⁻¹), and carboxylation efficiency (CE, mol CO₂ m⁻² s⁻¹) of soybean cultivar DM 5958 IPRO under different doses of saflufenacil, applied alone or combined with glyphosate, during the 2020/21 growing season. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil.

| Treatment |

Dose(g ha⁻¹) |

Physiological variables |

|

| Ci |

gS

|

A |

E |

WUE |

CE |

| Weed-free control |

--- |

261.75 a1

|

0.40 b |

21.79 b |

3.52 ns

|

6.36 b |

0.08 b |

| Glyphosate |

1440 |

250.75 b |

0.38 b |

22.44 b |

2.99 |

7.05 a |

0.09 b |

| Saflufenacil |

1.09 |

277.25 a |

0.40 b |

18.18 c |

3.18 |

5.91 b |

0.07 c |

| Saflufenacil |

2.17 |

273.25 a |

0.44 a |

19.84 c |

3.20 |

6.28 b |

0.07 c |

| Saflufenacil |

4.38 |

249.00 b |

0.40 b |

23.67 a |

3.17 |

7.58 a |

0.09 b |

| Saflufenacil |

8.75 |

245.25 b |

0.45 a |

23.80 a |

3.08 |

7.80 a |

0.09 b |

| Saflufenacil |

17.50 |

248.75 b |

0.43 a |

22.36 b |

2.99 |

7.58 a |

0.09 b |

| Saflufenacil |

35.00 |

243.00 b |

0.43 a |

22.04 b |

2.93 |

7.67 a |

0.09 b |

| Saflufenacil |

52.50 |

271.75 a |

0.37 b |

15.45 d |

2.93 |

5.39 b |

0.06 c |

| Saflufenacil |

70.00 |

268.50 a |

0.40 b |

18.38 c |

2.65 |

6.95 a |

0.07 c |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 1.09 |

265.25 a |

0.42 b |

18.63 c |

3.15 |

6.07 b |

0.07 c |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 2.17 |

222.67 b |

0.41 b |

24.48 a |

3.03 |

8.29 a |

0.11 a |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 4.38 |

262.50 a |

0.46 a |

22.68 b |

3.10 |

7.41 a |

0.09 b |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 8.75 |

262.25 a |

0.45 a |

21.22 b |

2.95 |

7.26 a |

0.08 b |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 17.50 |

257.25 b |

0.44 a |

23.17 a |

3.15 |

7.47 a |

0.09 b |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 35.00 |

262.00 a |

0.43 a |

20.61 b |

3.02 |

6.90 a |

0.07 c |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 52.50 |

249.25 b |

0.42 a |

23.41 a |

2.90 |

8.11 a |

0.09 b |

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 70.00 |

252.50 b |

0.42 a |

22.73 b |

3.02 |

7.67 a |

0.09 b |

| Mean average |

--- |

256.88 |

0.42 |

21.38 |

3.05 |

7.10 |

0.09 |

| C.V.2 (%) |

--- |

5.96 |

8.34 |

5.89 |

8.70 |

8.87 |

10.49 |

Table 4.

Yield components. Number of pods per plant (NPP), number of grains per plant (NGP), thousand-grain weight (TGW, g), and grain yield (GY, kg ha⁻¹) of soybean cultivar DM 5958 IPRO under different doses of saflufenacil, applied alone or combined with glyphosate, during the 2020/21 growing season. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil.

Table 4.

Yield components. Number of pods per plant (NPP), number of grains per plant (NGP), thousand-grain weight (TGW, g), and grain yield (GY, kg ha⁻¹) of soybean cultivar DM 5958 IPRO under different doses of saflufenacil, applied alone or combined with glyphosate, during the 2020/21 growing season. UFFS, Erechim Campus, RS, Brazil.

| Treatment |

Dose$$$(g ha⁻¹) |

Yield Components |

| NPP |

NGP |

TGW |

GY |

|

| Weed-free control |

--- |

63.25 a1

|

127.00 a |

163.93 b |

3549.22 b |

|

| Glyphosate |

1440 |

65.55 a |

147.35 a |

168.86 a |

3977.32 a |

|

| Saflufenacil |

1.09 |

49.20 b |

124.10 a |

167.90 a |

3522.21 b |

|

| Saflufenacil |

2.17 |

54.40 b |

122.35 a |

155.36 b |

3666.61 b |

|

| Saflufenacil |

4.38 |

49.55 b |

106.55 a |

158.34 b |

3271.05 c |

|

| Saflufenacil |

8.75 |

46.53 b |

95.87 b |

164.79 b |

2581.03 d |

|

| Saflufenacil |

17.50 |

60.05 a |

109.00 a |

178.10 a |

2313.32 e |

|

| Saflufenacil |

35.00 |

56.07 a |

96.70 b |

172.50 a |

947.13 g |

|

| Saflufenacil |

52.50 |

53.17 b |

86.80 b |

170.17 a |

376.05 h |

|

| Saflufenacil |

70.00 |

25.73 d |

55.47 c |

167.75 a |

275.19 h |

|

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 1.09 |

49.05 b |

91.45 b |

159.87 b |

3634.61 b |

|

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 2.17 |

50.40 b |

97.30 b |

167.90 a |

3076.72 c |

|

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 4.38 |

39.10 c |

75.75 c |

175.16 a |

2840.30 d |

|

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 8.75 |

36.93 c |

88.73 b |

173.32 a |

2507.97 d |

|

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 17.50 |

53.33 b |

88.30 b |

165.87 b |

2153.19 e |

|

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 35.00 |

54.40 b |

104.25 a |

171.47 a |

1805.88 f |

|

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 52.50 |

58.28 a |

118.00 a |

179.33 a |

1209.59 g |

|

| Glyphosate + Saflufenacil |

1440 + 70.00 |

56.93 a |

121.65 a |

175.06 a |

601.11 h |

|

| Mean average |

--- |

51.21 |

103.15 |

168.65 |

2349.99 |

|

| C.V.2 (%) |

--- |

10.73 |

16.12 |

3.99 |

9.82 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).