1. Introduction

Osteosarcopenia, defined as the concomitant presence of osteoporosis or osteopenia and sarcopenia, is an emerging geriatric syndrome associated with significant adverse health outcomes in older adults [

1]. As the global population ages, with estimates projecting 1.5 billion adults aged 65 and older by 2050 [

2], the prevalence of osteosarcopenia is expected to rise substantially, making it a public health concern.

Osteoporosis is characterized by reduced bone mineral density (BMD) and microarchitectural deterioration, which significantly raises the risk of fragility fractures. The incidence of fractures is particularly high in older adults due to their concurrent increased risk of falls [

3]. Sarcopenia, on the other hand, refers to the age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function. Currently, there is no approved pharmacological treatment for this condition [

4]. When osteoporosis and sarcopenia coexist, they can synergistically exacerbate the risk of falls, fractures, functional decline, and mortality in older individuals [

2].

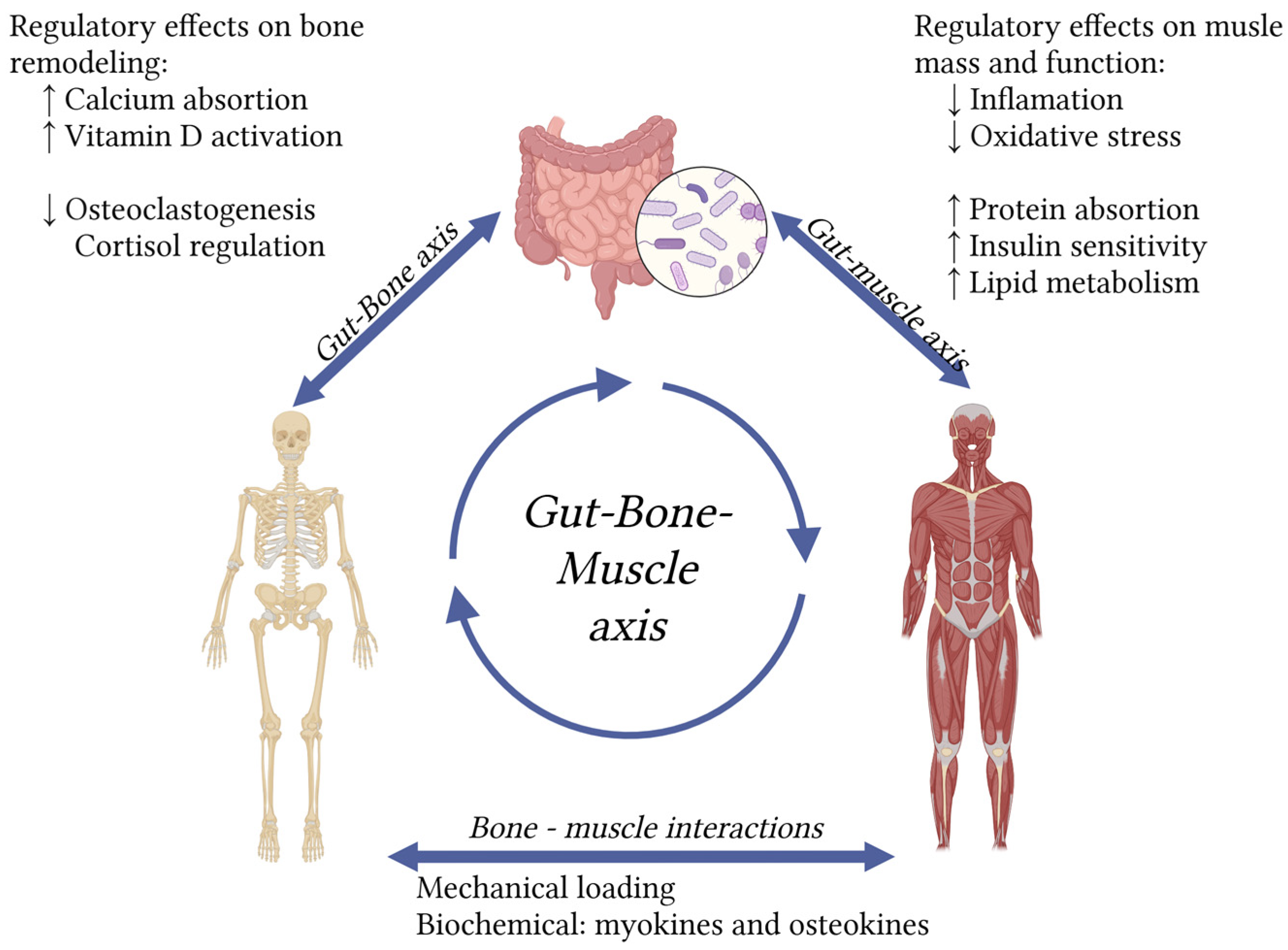

The pathophysiology of osteosarcopenia is complex and multifactorial, involving shared risk factors and biological mechanisms. Age-related hormonal changes, chronic low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress, and protein metabolism disruptions all contribute to bone and muscle degeneration [

1]. Current osteosarcopenia theories state that there is biochemical crosstalk through myokines and osteokines, as well as mechanical interactions between bone and muscle [

5], one nutritional intervention that benefits one of them, could have an impact on the other.

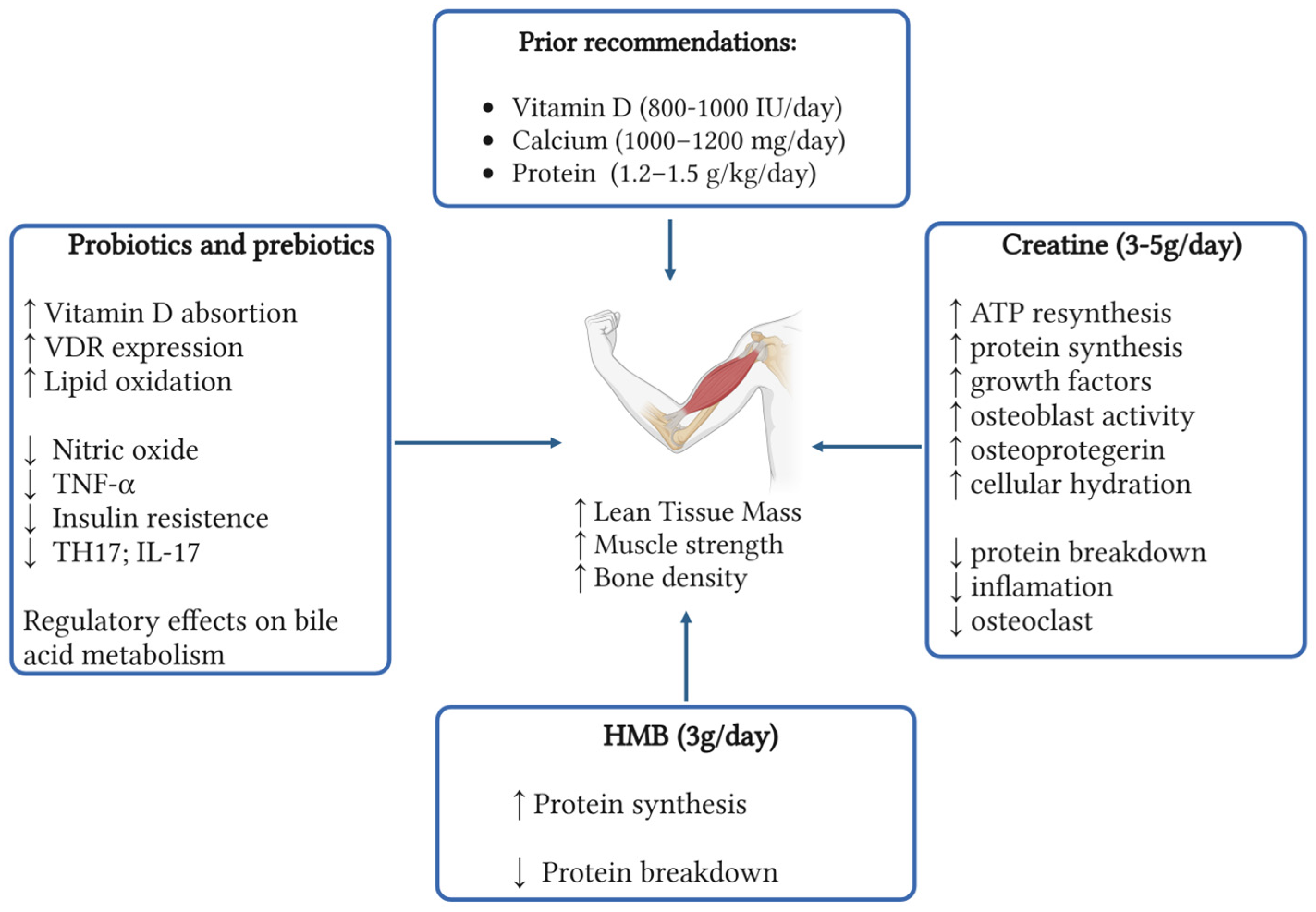

Current interventions for osteosarcopenia primarily emphasize structured exercise programs and adequate calcium (1,000–1,200 mg/day), vitamin D (800-1000 IU/day), and protein (1.2–1.5 g/kg/day) [

6]intake. However, emerging evidence suggests that novel nutritional strategies may offer additional benefits, including improvements in muscle mass, strength, fall prevention, and inflammatory modulation [

7].

This review aims to explore the potential role of emerging nutritional supplements—including creatine, β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB), prebiotics, probiotics, and agents targeting bile acid metabolism—in supporting both bone and muscle health. By synthesizing the most recent scientific findings, this review seeks to inform comprehensive management strategies for osteosarcopenia and highlight areas for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across the PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases. The MeSH terms: ‘osteosarcopenia,’ ‘osteoporosis,’ ‘sarcopenia,’, ‘sarco-osteopenia’, ‘creatine’, ‘B-hydroxy-B methylbutyrate’, ‘prebiotics’, ‘probiotics’, ‘bile acid metabolism’ and ‘nutritional supplements’ were used. OpenEvidence artificial intelligence was also employed in the literature search. Relevant observational studies, clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses published between January 2020 and June 2025 were included. Additionally, a reverse bibliography search was conducted to further explore key definitions and concepts.

2.2. Study Selection

The selection of studies was based on their relevance to the topic, initially assessed through title and abstract, and subsequently confirmed through full-text review.

Inclusion Criteria:

Published original research studies, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies exploring supplementation in osteosarcopenia.

Literature reviews of supplementation in osteosarcopenia.

Exclusion criteria were:

Studies focusing on medical interventions.

Case reports.

Only English language publications were considered.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

The reviewers conducted the database search and selected the studies to be included in this review. After identifying the relevant studies, the information was synthesized into themes and subthemes based on the supplements with the strongest supporting evidence.

2.4. Quality Assessment

Three reviewers evaluated each study’s methodology, sample size, and potential biases. The outcomes reported in each study were analyzed, and efforts were made to ensure that potential biases and limitations were adequately addressed in the review. Only studies with methodological quality and publication in high-impact journals were included.

3. Creatine

3.1. Creatine: A Well-Known Supplement

Creatine is a nitrogen-containing organic compound that plays a critical role in cellular energy metabolism. It serves as a short-term, localized energy reserve for adenosine triphosphate (ATP), particularly in tissues with high and fluctuating energy demands such as skeletal muscle and the brain [

8]. Endogenously, creatine is synthesized primarily in the kidneys and liver via a two-step enzymatic process [

9].

Dietary creatine is predominantly derived from animal-based foods, including meat and fish. In omnivorous individuals, approximately half of the body’s creatine requirements are met through dietary intake, while the remainder is synthesized from precursor amino acids. However, older adults often consume lower amounts of both creatine and its amino acid precursors, which may compromise creatine availability and suggest a potential benefit from supplementation to achieve optimal physiological levels [

10].

Since the 1990s, creatine monohydrate supplementation has gained widespread popularity, particularly in sports and clinical settings. Extensive research has confirmed its safety profile. According to the International Society of Sports Nutrition, a daily intake of 3 grams of creatine monohydrate is sufficient to maintain adequate creatine stores and is considered safe for long-term use in healthy individuals [

11].

3.1.1. Effects of Creatine in Aging Muscle

Supplementation with creatine increases intramuscular phosphocreatine availability, enhancing the capacity for ATP resynthesis during resistance exercise, this supports greater training intensity and volume, which in turn stimulates muscle protein synthesis and hypertrophy. Additionally, creatine may exert direct anabolic and anti-catabolic effects by modulating cellular hydration, influencing growth factor signaling (e.g., IGF-1), and reducing muscle protein breakdown [

12].

Over the past few decades, research has consistently demonstrated that creatine supplementation combined with resistance training yields greater improvements in muscle mass, strength, and functional performance in older adults compared to resistance training alone [

13,

14]. Notably, functional gains have been observed through assessments such as the sit-to-stand test, indicating enhanced lower-body performance [

7]. This is clinically relevant, as improvements in lower-limb muscle density are associated with a reduced risk of falls, functional impairment, disease progression, and premature mortality in aging populations [

15,

16]

3.1.2. Effects on Aging Bone

Bone cells rely on the creatine kinase reaction to generate energy, utilizing phosphocreatine to regenerate ATP [

17]. This enzyme activity increases when osteoblasts become activated [

18]. In vitro, studies have demonstrated that creatine supplementation enhances metabolic activity, promotes differentiation, and supports mineralization in osteoblast-like cells [

19]. Activated osteoblasts also produce osteoprotegerin, a protein that acts as a decoy receptor for receptor activator of nuclear factor kB ligand (RANK-L). By blocking RANK-L’s interaction with RANK, osteoprotegerin inhibits the formation of bone-resorbing osteoclasts, thereby helping to reduce bone turnover [

20].

While recent studies indicate that creatine may not significantly increase BMD in older adults [

21] , it could influence beneficial geometric changes in bone that enhance fracture protection [

14]. Furthermore, the increased muscle mass often associated with creatine supplementation may indirectly stimulate greater bone formation over time by generating increased mechanical forces on the bone [

22].

Collectively, creatine has the potential to reduce the risk of falls in aging adults, which, in turn, would decrease fracture risk [

7]. However, these benefits appear to diminish without concurrent exercise intervention [

13,

22].

3.1.3. Creatine Plus Other Supplements

Combining creatine with other supplements may offer additional benefits. One study, for instance, found that healthy older men who took whey protein and creatine three times a week for ten weeks, alongside supervised whole-body resistance training, saw greater increases in whole-body fat-free mass and relative upper-body maximal strength than those who only took creatine [

23].

Beyond protein, supplementing leucine and BCAAs (branched-chain amino acids) plus vitamin D has shown improvements in muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in older adults experiencing sarcopenia and malnutrition [

24].

Interestingly, we didn’t find any studies in this review that investigated the combined use of creatine with prebiotics or probiotics in older adults for effects on muscle mass, strength, or bone health. Similarly, while the role of creatine plus HMB (beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate) has been explored in younger populations or athletes [

25], its effectiveness when combined for older adults remains unestablished. This area is certainly of interest for future randomized controlled trials.

3.1.4. Conclusions on Creatine

Given the positive findings regarding creatine’s effects on muscle and bone in healthy older adults, it holds potential as an adjunct to exercise training for managing osteosarcopenia. However, further investigation is needed to confirm its effectiveness in older populations.

4. β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate

4.1. β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate: A Promising New Supplement

HMB, a metabolite of the amino acid leucine, is gaining attention for its potential to impact muscle mass and function, especially in older adults. About 5% of leucine converts to HMB in the human body through enzyme-mediated processes [

26]. Higher HMB plasma levels have been linked to increased appendicular lean mass and better hand grip strength (HGS) in healthy individuals [

27].

HMB primarily affects muscle by boosting protein synthesis through mTOR pathway stimulation, reducing protein breakdown, enhancing muscle repair, and improving aerobic capacity [

28]. Long-term oral supplementation (1.5-3 g/day) appears safe for at least one year, with short-term dosing up to 6 g/day for 8 weeks showing no adverse effect [

29].

4.1.1. Effects on Aging Muscle

Older adults and frail individuals often experience a decline in physical activity, which accelerates muscle loss. Recent research indicates that HMB supplementation may mitigate lean mass losses in older inpatients, outpatients, and critically ill patients [

26,

30]. For patients with reduced mobility, HMB could be a valuable intervention to counteract these effects, potentially improving quality of life and maintaining independence. However, other studies have yielded mixed results.

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have investigated HMB’s effects on muscle parameters in aging and clinical populations. While some studies suggest HMB augments lean soft-tissue mass (LSTM), others report no difference or insufficient evidence. A 2019 meta-analysis of 15 RCTs found some evidence supporting HMB’s effect on increasing skeletal muscle mass and strong evidence for improving muscle strength. However, this meta-analysis included an all-age population, and the effect sizes were small [

30].

A 2022 umbrella review analyzed 15 systematic reviews on HMB supplementation in aging and clinical populations, using DXA-measured LSTM as a proxy for muscle mass. The findings were largely inconsistent: only five reviews showed some benefit for LSTM, while the remainder found no effect or lacked sufficient evidence. Of 12 studies assessing strength, only 4 showed some benefit, with most others indicating no effect or inconclusive results, particularly showing no consistent benefit in community-dwelling individuals. Physical function outcomes were even less promising, with no study reporting a clear positive effect [

26].

More recent RCTs also present mixed results. A 2023 study involving older adults with sarcopenia reported significant improvements in HGS, gait speed, and muscle quality with HMB supplementation compared to placebo. However, no significant differences were observed in skeletal muscle mass or body composition parameters [

28]. These findings are particularly relevant given that HGS is a core component in sarcopenia diagnosis [

31].

A 2024 meta-analysis of six RCTs, specifically focusing on sarcopenia patients, found a statistically significant difference in HGS with HMB or HMB-rich nutritional supplements, but no significant differences in gait speed, fat mass, fat-free mass, or skeletal muscle index. This analysis suggested that HMB supplementation might be more effective with an intervention duration of 12 weeks or longer [

32].

Finally, a 2025 meta-analysis of five RCTs revealed beneficial effects on muscle mass and strength, demonstrated by higher skeletal muscle mass index and elevated HGS in HMB intervention groups. The overall meta-analysis showed increased HGS in the HMB intervention groups compared to control groups. Nevertheless, no evidence of benefit on physical performance (as assessed by gait speed) was found [

33].

4.1.2. Effects on Aging Bone

Current evidence regarding HMB and bone health is limited to preclinical animal studies. For instance, in spiny mouse models of osteoporosis, HMB supplementation during pregnancy was linked to improved trabecular bone microarchitecture and the prevention of bone loss. This effect is likely due to HMB’s modulation of bone cell activity and collagen remodeling [

34,

35]. However, these promising findings have not yet been replicated in human studies, and no randomized controlled trials have evaluated HMB for osteoporosis prevention or treatment in humans.

4.1.3. HMB Plus Other Supplements

Some studies have begun to explore the potential synergistic effects of combining HMB with other nutrients:

HMB plus probiotics: Research suggests that certain probiotic strains might increase HMB exposure in tissues and plasma [

36] or offer synergistic anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties when combined with HMB [

37] Further research is required to fully investigate these mechanisms and benefits.

HMB plus Creatine: Several studies indicate positive effects on athletic performance when HMB is combined with creatine, though these studies have not specifically focused on older populations [

25].

HMB plus Vitamin D: The co-administration of HMB-Ca with vitamin D3 in healthy older adults with documented vitamin D insufficiency has been shown to enhance muscle strength [

38,

39]

HMB plus Protein: HMB has been demonstrated to amplify the anabolic effects of plant-based (soy) protein ingestion during a fasting catabolic state [

40]. Conversely, other studies in young athletes did not show additional improvements when HMB was added to whey protein [

29].

4.1.4. Conclusions on HMB

The evidence for HMB supplementation improving muscle mass, strength, and function in aging and clinical populations remains inconclusive. While some studies report promising outcomes, especially concerning muscle strength and quality, others find no significant effects or present inconclusive evidence. Despite these inconsistent findings, HMB supplementation appears to be safe and well-tolerated, suggesting its potential as an option for managing age-related sarcopenia under specific conditions. However, its effect on osteoporosis is yet to be determined, and further research is crucial to establish HMB’s efficacy, particularly in the context of osteosarcopenia.

5. Prebiotics and Probiotics

5.1. Prebiotics and Probiotics: Targeting the Gut-Muscle-Bone Axis

Probiotics are described as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit to the host” [

41]. These typically include specific bacterial or yeast strains, most commonly from

the Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Streptococcus, and

Bifidobacterium genera [

42]. They are generally found in fermented foods or dietary supplements. Probiotics are believed to exert their effects by competing with pathogens for adhesion sites, enhancing the gut barrier, modulating immune responses, and aiding in neurotransmitter production.

In contrast, prebiotics are non-digestible food components, often specific types of dietary fibers or oligosaccharides (such as inulin and oligofructose) that positively impact the host by selectively promoting the growth and/or activity of beneficial microorganisms [

43,

44]. Prebiotics act as substrates for these microbes, encouraging their growth and metabolic activity, which in turn can lead to host health benefits. Prebiotics are considered safe for all ages after the fifth month of life, with potential side effects limited to bloating, gas, and increased bowel movements [

45].

The term “synbiotic” refers to the combination of prebiotics and probiotics, designed to enhance the viability of the consumed probiotics [

46]. Currently,

Bifidobacterium species are the most extensively studied in synbiotic applications related to bone health [

47]. Modifying the gut microbiota through these interventions appears to be a promising strategy for treating osteosarcopenia.

The gut microbiota is acquired primarily from the mother at birth, then influenced by numerous factors, including genetic background, diet, age, medical treatments, antibiotic use, and geographical location [

45,

48,

49]. Recent studies also indicate that myokines and cytokines, produced during skeletal muscle contraction and released into the bloodstream, can influence the gut microbiota. IL-6 was the first identified myokine, alongside others like irisin and myostatin. These molecules mediate metabolic processes, regulate inflammation, and influence muscle growth, contributing to overall health. Recent research has unveiled a bidirectional relationship between the gut and muscle, known as the gut-muscle axis. Exercise positively affects gut microbial diversity and composition through this axis, while the gut microbiota, in turn, impacts muscle function and metabolism. Evidence suggests that this muscle-gut axis plays a role in the pathophysiology of physical frailty and sarcopenia, although a definitive causal link has yet to be established [

50]. Adverse effects are uncommon and usually mild when using standard commercially available products, often involving temporary gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating, gas, or mild abdominal discomfort [

51], although there have been reported cases of bacteremia and liver abscess associated with probiotic use in older patients, these are rare complications[

52].

5.1.1. Effects on Aging Muscle

The gut microbiota, the most abundant and complex microbiota in the human body, is extensively studied for its association with various diseases [

42]. It plays a pivotal role in the aging process by regulating energy balance, metabolism, and inflammation, thereby impacting the progression of sarcopenia [

53]. Structural alterations in the gut microbiota are linked to the development of numerous chronic conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases [

54]. The concept of the gut-muscle axis suggests a potential correlation between gut microbiota and the quality and functionality of skeletal muscle [

55].

Currently, non-pharmacological interventions such as exercise and nutritional strategies remain the first-line treatments for sarcopenia. Developing innovative, safe, efficient, and affordable sarcopenia treatments remains a critical challenge [

56].

According to the gut-muscle axis hypothesis, muscle function and metabolism significantly depend on the quantity and composition of the gut microbiota. Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota can lead to increased gut barrier permeability, endotoxin translocation, and insulin resistance, ultimately resulting in impaired muscle protein synthesis [

56]. Consequently, gut microbes could emerge as potential biological targets for the prevention and therapy of muscle-related disorders like sarcopenia and muscle atrophy [

57].

While

Lactobacillus probiotics are commonly used for gut health and immune support, their precise mechanism in alleviating sarcopenia via the gut-muscle axis remains uncertain. However, potential mechanisms identified include the relief of inflammatory states, clearance of excess reactive oxygen species, improvement of skeletal muscle metabolism, and regulation of gut microbiota and its metabolites [

56].

A comprehensive review in 2025 synthesized findings from ten studies (421 individuals with sarcopenia and 1,642 control subjects) examining the association between gut microbiota and sarcopenia. The analysis revealed that individuals with sarcopenia exhibited an increased presence of certain inflammation-associated bacteria, such as

Proteobacteria and

Escherichia-

Shigella. Conversely, there was a decreased presence of beneficial bacteria, including

Firmicutes,

Faecalibacterium,

Prevotella 9, and

Blautia. These alterations in gut microbiota may contribute to sarcopenia by potentially inducing inflammation, impairing nutrient absorption, and disrupting metabolic processes [

58]. Specifically in older adults, a significant decrease in the proportion of

Lactobacilli,

Bacteroidetes, and

Prevotella, coupled with increased

Escherichia coli, has been observed in sarcopenia patients [

59].

Lactobacillus can restore the composition and beta diversity of intestinal microbiota, which may be one of the ways to play a therapeutic role in sarcopenia [

60].

Lactobacillus alleviates oxidative stress by indirectly or directly inhibiting nitric oxide production

. L. plantarum down-regulates the expression level of the syncytin-1, nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and TNF-α gene present in skeletal muscle, restores overall energy balance in muscle tissue of animals and reduces the oxidative response [

61].

Sarcopenia is often accompanied by insulin resistance and both are mutually pathogenic,

Lactobacillus strains contribute to a decrease in insulin resistance [

62]. Abnormal accumulation of lipids in the body will accelerate muscle atrophy and muscle steatosis [

63]. Effects of probiotics in lipid metabolism include: enhancement of lipid oxidation, reduction in white adipose tissue and fat accumulation , modulation of adiponectin (APN) and AMPK Pathways, increasing insulin sensitivity, these effects are highly strain-specific, and not all strains produce beneficial outcomes [

56].

A comprehensive analysis of 22 studies investigating the effects of probiotics on sarcopenia across all age groups provides nuanced insights. Overall, the results showed no statistically significant improvements in muscle mass or lean body mass in individuals receiving probiotic supplementation compared to placebo [

64]. Notably, only one study focused specifically on older adults aged over 70 years. In this trial, mildly frail participants supplemented with

L. plantarum TWK10 for 18 weeks demonstrated significant improvements in HGS and muscle mass, though BMD remained unchanged [

65]. These findings support the potential of probiotics to improve muscle function in sarcopenia, particularly in older adults, but emphasize the need for additional high-quality, targeted research to confirm these benefits and determine long-term effects.

5.1.2. Effects on Aging Bone

The gut microbiota significantly influences bone metabolism, presenting a potential new target to modify BMD. This interplay has led to the concept of the gut-bone axis [

54]. Evidence primarily from mouse models demonstrates the gut microbiota’s involvement in modulating the interaction between the immune system and bone cells [

45]. A recent meta-analysis further showed that prebiotics improve BMD in ovariectomized rats [

66], highlighting an opportunity to address their role in osteosarcopenia.

Several pathways connect the gut microbiota to osteosarcopenia, including its interaction with calcium and vitamin D absorption. A reduction in 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D production can lead to gut inflammation and alter GM composition [

67], hormonal secretion, and immune responses. For instance, oral supplementation with

L. reuteri has been shown to increase serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and tibial bone density [

68,

69]. Similarly,

L. rhamnosus strain GG and

L. plantarum increased vitamin D receptor (VDR) protein expression [

70]. Research has also found that

L. rhamnosus GG and

L. plantarum can increase the expression of the VDR protein in both mouse and human intestinal epithelial cells while enhancing its transcriptional activity. By activating the VDR signaling pathway, these probiotics ultimately promote vitamin D absorption and the expression of its target genes, such as the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin, exerting anti-inflammatory effects [

70].

Another key role is played by T helper 17 lymphocytes (Th17), a subset of proinflammatory T helper cells which play an important role in maintaining the mucosal barrier and preventing intestinal colonization by pathogenic bacteria [

71]. Some probiotics, such as

Bacillus clausii [

72],

L. acidophilus [

73], and

L. rhamnosus [

74], enhanced bone health by inhibiting osteoclastogenic Th17 cells and promoting anti-osteoclastogenic Treg cells in postmenopausal osteoporotic mice. Th17 produce Interleukin 17 (IL-17), which exacerbates local inflammation, leading to increased inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1, which, in turn, elevate RANK-L expression and activate osteoclast precursor cells and the RANK-L system [

71]. Other important pathways include nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain proteins (NOD1, NOD2) which are intracellular sensors of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), mainly expressed on epithelial and immune cells, that bind bacterial peptidoglycans and activate the NFkB pathway playing a key role in the effects of microbiota on bone. On the other hand, a recent study has identified Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) as a new mediator in the process of inflammation-induced bone loss and osteoclastogenesis, through the activation of the RANK-L pathway [

71,

75,

76]

Alginate oligosaccharides (AOS) have garnered attention as prebiotics capable of regulating human health. A recent study demonstrated that administering 200 mg/kg body weight AOS significantly increased bone mass, boosted muscle function, and promoted gut barrier integrity in ovariectomized (OVX) mice. This was achieved by modulating bile acid (BA) metabolism and reducing intestinal Th17 cells and peripheral inflammation [

77].

Research using germ-free mice (raised in sterile conditions without gut microbiota) has yielded conflicting effects of gut microbiota on bone health. These mice typically exhibit underdeveloped immune systems and show varied bone density outcomes [

45].

A potential mechanism by which the gut microbiota influences osteoporosis involves its effect on intestinal barrier function, particularly through the regulation of tight junctions, which are essential for maintaining barrier integrity. Disruptions in this barrier have been linked to glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis [

78]. In murine models, interventions such as

L. reuteri and high-molecular-weight polymers (which enhance barrier function) have been shown to prevent glucocorticoid-induced bone loss. Immune cells in the intestinal subepithelial tissue produce osteoclastogenic cytokines like interleukin-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α); increased intestinal permeability can elevate these cytokine levels, potentially leading to reduced BMD [

79]. Additionally, the ratio of intestinal villus height to crypt depth is an important indicator of digestive and absorptive capacity. Studies have demonstrated that dietary supplementation with probiotics such as

Bacillus subtilis,

Rhamnobacterium, and heat-inactivated

L. plantarum can increase this ratio, enhance mucosal morphology, support beneficial bacterial colonization, and ultimately improve nutrient absorption [

80,

81].

Gut microbiota can also affect bone remodeling through gut microbiota-derived metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). SCFAs, including acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid, and valeric acid, have been reported to play a significant role in osteoclasts and osteoblasts [

82,

83]. TMAO, a choline metabolite, is another important gut microbiota-dependent metabolite associated with bone remodeling. Serum TMAO levels in osteoporosis patients are often higher than in healthy individuals, showing a negative correlation with BMD [

84]. SCFAs may also influence bone health by affecting the production of hormones such as parathyroid hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and serotonin [

54].

Regarding endocrine regulation, the intestine is considered the largest endocrine organ in the human body [

85]. Cortisol can regulate immune cell activity and cytokine release in the intestine, thereby affecting intestinal permeability, gut barrier function, and GM composition.

5.1.3. Gut Microbiota and Bile Acid Metabolism

Bile acids (BAs) are a group of cholesterol metabolites, an important component of the bile. Once considered solely digestive agents, they are now recognized as multifunctional signaling molecules with effects on metabolism, the immune system, and intestinal bacterial growth [

86,

87].

They are classified into primary and secondary BAs based on their site of synthesis and degree of microbial modification. Primary BAs are synthesized in hepatocytes; the two main primary BAs are cholic acid (CA) and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA). Primary bile acid supplements are used to treat cholestatic liver diseases to replace or augment endogenous bile acids. These acids are conjugated with glycine or taurine and then secreted into the bile and stored in the gallbladder. After food intake, they are released into the duodenum. About 95% of primary BAs are reabsorbed, but the remaining 5% reach the colon and are modified by the gut microbiota into secondary BAs, mainly deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA). These modifications alter the BA pool in the individual. Recent evidence suggests that variations in the composition of the BAs pool may influence human longevity [

87]. This relationship may play a role in mitigating the development of age-related diseases, particularly in connection with microbiota dysbiosis.

BAs are believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of secondary sarcopenia promoting skeletal muscle growth while reducing skeletal muscle waste. Systemic circulation allows the secondary BAs to act as endocrine molecules [

88].

Lactobacillus can modulate BAs metabolism and affect its gastrointestinal transport [

89]. Also, metabolomic studies have identified disturbances in and BAs metabolism in patients with osteoporosis [

90,

91].

A cross-sectional study in China evaluated the relationship between serum BAs levels and BMD in 150 postmenopausal women, stratified into three groups: osteoporosis, osteopenia, and healthy controls. Researchers measured serum concentrations of total BAs, fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19), bone turnover markers and BMD. Findings revealed that women in the osteoporosis and osteopenia groups had significantly lower serum BAs levels compared to healthy controls, and BAs concentrations were positively correlated with BMD at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip regions [

92].

BAs are increasingly recognized as modulators of bone and muscle, since its metabolism seems to affect them directly as endocrine molecules and indirectly by interacting with gut microbiota, it is an interesting new pathway to explore in the treatment of osteosarcopenia.

5.1.5. Conclusions on Prebiotics and Probiotics

Literature describes the “gut-bone axis” and the “gut-muscle axis” as distinct but related concepts, both focusing on the profound influence of gut microbiota on bone and muscle health. Taken together, these results highlight that probiotics and prebiotics can positively regulate both muscle and bone. Considering the strong association and shared pathophysiology between osteoporosis and sarcopenia, the overarching concept of a gut–muscle–bone axis presents significant potential for future research and therapeutic strategies targeting osteosarcopenia.

Figure 1.

The gut-bone-muscle axis highlights the impact of gut microbiota on osteosarcopenia. (Created in

https://BioRender.com).

Figure 1.

The gut-bone-muscle axis highlights the impact of gut microbiota on osteosarcopenia. (Created in

https://BioRender.com).

4. Discussion

Searching for new strategies to treat and prevent osteosarcopenia is needed due to the upcoming shift in the aging population. In this review, we made a comprehensive analysis of some of the emerging supplements that can be used and how these affect the muscle and bone (

Figure 2). Overall, they appear safe and well tolerated in the older population with minimal risks of adverse effects. Creatine monohydrate has been studied in multiple scenarios across time, with the main action over the muscle and indirectly promoting bone health. These positive changes appear tightly linked to routine exercise, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive and multidisciplinary therapy. Literature supports the use of creatine plus protein and vitamin D, giving it an advantage over other supplements yet to be studied in combination.

The body of evidence supporting HMB supplementation continues to grow, although results remain heterogeneous. Most studies have focused on its effects on muscle health, given its role in stimulating protein synthesis, rather than on bone health. Interestingly, while some trials report less favorable outcomes in terms of body mass composition, improvements have been observed in strength measures such as HGS. Since long-term HMB supplementation is safe, a more integrative evaluation considering its impact on functional outcomes may offer a clearer understanding of its real-world benefits.

Probiotics and prebiotics represent promising interventions for maintaining a healthy gut microbiota, with potential benefits not only for osteosarcopenia but also for other chronic conditions associated with aging. However, several considerations must be addressed regarding their supplementation. First, an individual’s microbiota composition is heavily influenced by environmental and personal history factors, which makes it challenging to generalize findings across diverse populations. Additionally, different bacterial strains appear to confer benefits to specific physiological systems, raising important questions about strain selection and how to translate this knowledge into clinical practice. Bile acid metabolism, which closely interacts with gut microbiota, has emerged as a promising area of research in the aging population. While clinical evidence for probiotics is more robust, further exploration of prebiotics—and the combined use of both—offers valuable opportunities for future investigation.

5. Conclusions

Nutritional interventions for osteosarcopenia play a pivotal role not only in improving bone and muscle composition but also in enhancing functional outcomes in older adults. Emerging strategies involving creatine monohydrate, HMB, probiotics, and prebiotics show great potential as part of a comprehensive patient-centered approach. However, further research is needed to determine the most effective strategies and to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from each supplement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.M. and G.D.; methodology, J.E.M and M.F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.E.M; writing—review and editing, J.E.M, M.F.C, D.R., H.R., G.D.; supervision, G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Duque serves on the Scientific Advisory Committee and has received research grants from TSI Pharma. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Franulic F, Salech F, Rivas D, Duque G. Deciphering Osteosarcopenia through the hallmarks of aging. Mech Ageing Dev 2024;222:111997. [CrossRef]

- Kirk B, Zanker J, Duque G. Osteosarcopenia: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment—facts and numbers. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020;11:609–18. [CrossRef]

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Nicholson WK, Silverstein M, Wong JB, Chelmow D, Coker TR, et al. Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2025;333:498. [CrossRef]

- Kirk B, Cawthon PM, Arai H, Ávila-Funes JA, Barazzoni R, Bhasin S, et al. The Conceptual Definition of Sarcopenia: Delphi Consensus from the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS). Age Ageing 2024;53:afae052. [CrossRef]

- Smith C, Sim M, Dalla Via J, Levinger I, Duque G. The Interconnection Between Muscle and Bone: A Common Clinical Management Pathway. Calcif Tissue Int 2023;114:24–37. [CrossRef]

- Kirk B, Prokopidis K, Duque G. Nutrients to mitigate osteosarcopenia: the role of protein, vitamin D and calcium. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2021;24:25–32. [CrossRef]

- Candow DG, Forbes SC, Chilibeck PD, Cornish SM, Antonio J, Kreider RB. Effectiveness of Creatine Supplementation on Aging Muscle and Bone: Focus on Falls Prevention and Inflammation. J Clin Med 2019;8:488. [CrossRef]

- Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME. Creatine: Endogenous Metabolite, Dietary, and Therapeutic Supplement. Annu Rev Nutr 2007;27:241–61. [CrossRef]

- Barcelos RP, Stefanello ST, Mauriz JL, Gonzalez-Gallego J, Soares FAA. Creatine and the Liver: Metabolism and Possible Interactions. Mini-Rev Med Chem 2015;16:12–8. [CrossRef]

- Nedeljkovic D, Ostojic SM. Dietary exposure to creatine-precursor amino acids in the general population. Amino Acids 2025;57:29. [CrossRef]

- Kreider RB, Kalman DS, Antonio J, Ziegenfuss TN, Wildman R, Collins R, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2017;14:18. [CrossRef]

- Cordingley DM, Cornish SM, Candow DG. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Catabolic Effects of Creatine Supplementation: A Brief Review. Nutrients 2022;14:544. [CrossRef]

- Candow DG, Chilibeck PD, Forbes SC, Fairman CM, Gualano B, Roschel H. Creatine supplementation for older adults: Focus on sarcopenia, osteoporosis, frailty and Cachexia. Bone 2022;162:116467. [CrossRef]

- Candow DG, Kirk B, Chilibeck PD, Duque G. The potential of creatine monohydrate supplementation in the management of osteosarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2025;28:235–9. [CrossRef]

- Candow DG, Chilibeck PD, Gordon J, Vogt E, Landeryou T, Kaviani M, et al. Effect of 12 months of creatine supplementation and whole-body resistance training on measures of bone, muscle and strength in older males. Nutr Health 2021;27:151–9. [CrossRef]

- Fragala MS, Cadore EL, Dorgo S, Izquierdo M, Kraemer WJ, Peterson MD, et al. Resistance Training for Older Adults: Position Statement From the National Strength and Conditioning Association. J Strength Cond Res 2019;33:2019–52. [CrossRef]

- Wallimann T, Hemmer W. Creatine kinase in non-muscle tissues and cells. Mol Cell Biochem 1994;133–134:193–220. [CrossRef]

- Ch’ng JL, Ibrahim B. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms modulate creatine kinase expression during differentiation of osteoblastic cells. J Biol Chem 1994;269:2336–41.

- Institute of Cell Biology, ETH Hoenggerberg, CH-8093 Zurich, Switzerland, Gerber I, Ap Gwynn I, Alini M, Wallimann T. Stimulatory effects of creatine on metabolic activity, differentiation and mineralization of primary osteoblast-like cells in monolayer and micromass cell cultures. Eur Cell Mater 2005;10:8–22. [CrossRef]

- Kearns AE, Khosla S, Kostenuik PJ. Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand and osteoprotegerin regulation of bone remodeling in health and disease. Endocr Rev 2008;29:155–92. [CrossRef]

- Hong M, Wang J, Jin L, Ling K. The impact of creatine levels on musculoskeletal health in the elderly: a mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2024;25:1004. [CrossRef]

- Forbes SC, Candow DG. Creatine and strength training in older adults: an update. Transl Exerc Biomed 2024;1:212–22. [CrossRef]

- Candow DG, Little JP, Chilibeck PD, Abeysekara S, Zello GA, Kazachkov M, et al. Low-Dose Creatine Combined with Protein during Resistance Training in Older Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:1645–52. [CrossRef]

- Cochet C, Belloni G, Buondonno I, Chiara F, D’Amelio P. The Role of Nutrition in the Treatment of Sarcopenia in Old Patients: From Restoration of Mitochondrial Activity to Improvement of Muscle Performance, a Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023;15:3703. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Landa J, Calleja-González J, León-Guereño P, Caballero-García A, Córdova A, Mielgo-Ayuso J. Effect of the Combination of Creatine Monohydrate Plus HMB Supplementation on Sports Performance, Body Composition, Markers of Muscle Damage and Hormone Status: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019;11:2528. [CrossRef]

- Phillips SM, Lau KJ, D’Souza AC, Nunes EA. An umbrella review of systematic reviews of β-hydroxy-β-methyl butyrate supplementation in ageing and clinical practice. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022;13:2265–75. [CrossRef]

- Kuriyan R, Lokesh DP, Selvam S, Jayakumar J, Philip MG, Shreeram S, et al. The relationship of endogenous plasma concentrations of β-Hydroxy β-Methyl Butyrate (HMB) to age and total appendicular lean mass in humans. Exp Gerontol 2016;81:13–8. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Song Y, Li T, Chen X, Zhou J, Pan Q, et al. Effects of Beta-Hydroxy-Beta-Methylbutyrate Supplementation on Older Adults with Sarcopenia: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J Nutr Health Aging 2023;27:329–39. [CrossRef]

- Rathmacher JA, Pitchford LM, Stout JR, Townsend JR, Jäger R, Kreider RB, et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB). J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2025;22:2434734. [CrossRef]

- Bear DE, Langan A, Dimidi E, Wandrag L, Harridge SDR, Hart N, et al. β-Hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate and its impact on skeletal muscle mass and physical function in clinical practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2019;109:1119–32. [CrossRef]

- Mayhew AJ, Sohel N, Beauchamp MK, Phillips S, Raina P. Sarcopenia Definition and Outcomes Consortium 2020 Definition: Association and Discriminatory Accuracy of Sarcopenia With Disability in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J Gerontol Ser A 2023;78:1597–603. [CrossRef]

- Su H, Zhou H, Gong Y, Xiang S, Shao W, Zhao X, et al. The effects of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate or HMB-rich nutritional supplements on sarcopenia patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med 2024;11:1348212. [CrossRef]

- Gu W-T, Zhang L-W, Wu F-H, Wang S. The effects of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate supplementation in patients with sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2025;195:108219. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska E, Muszyński S, Donaldson J, Dobrowolski P, Chand DKP, Tomczyk-Warunek A, et al. Femoral µCT Analysis, Mechanical Testing and Immunolocalization of Bone Proteins in β-Hydroxy β-Methylbutyrate (HMB) Supplemented Spiny Mouse in a Model of Pregnancy and Lactation-Associated Osteoporosis. J Clin Med 2021;10:4808. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska E, Donaldson J, Kosiński J, Dobrowolski P, Tomczyk-Warunek A, Hułas-Stasiak M, et al. β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate (HMB) Supplementation Prevents Bone Loss during Pregnancy—Novel Evidence from a Spiny Mouse (Acomys cahirinus) Model. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:3047. [CrossRef]

- Rathmacher J, Pitchford L, Khoo P, Sharp R. Probiotic Bacillus coagulans GBI-30, 6086 Supplementation Improves β-Hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate Bioavailability. FASEB J 2021;35:fasebj.2021.35.S1.01949. [CrossRef]

- Gepner Y, Hoffman JR, Shemesh E, Stout JR, Church DD, Varanoske AN, et al. Combined effect of Bacillus coagulans GBI-30, 6086 and HMB supplementation on muscle integrity and cytokine response during intense military training. J Appl Physiol 2017;123:11–8. [CrossRef]

- Rathmacher JA, Pitchford LM, Khoo P, Angus H, Lang J, Lowry K, et al. Long-term Effects of Calcium β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate and Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Muscular Function in Older Adults With and Without Resistance Training: A Randomized, Double-blind, Controlled Study. J Gerontol Ser A 2020;75:2089–97. [CrossRef]

- Nasimi N, Sohrabi Z, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Eskandari MH, Bedeltavana A, Famouri M, et al. A Novel Fortified Dairy Product and Sarcopenia Measures in Sarcopenic Older Adults: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22:809–15. [CrossRef]

- Rittig N, Bach E, Thomsen HH, Møller AB, Hansen J, Johannsen M, et al. Anabolic effects of leucine-rich whey protein, carbohydrate, and soy protein with and without β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB) during fasting-induced catabolism: A human randomized crossover trial. Clin Nutr 2017;36:697–705. [CrossRef]

- Martín R, Langella P. Emerging Health Concepts in the Probiotics Field: Streamlining the Definitions. Front Microbiol 2019;10:1047. [CrossRef]

- Zaib S, Hayat A, Khan I. Probiotics and their Beneficial Health Effects. Mini-Rev Med Chem 2024;24:110–25. [CrossRef]

- Davani-Davari D, Negahdaripour M, Karimzadeh I, Seifan M, Mohkam M, Masoumi S, et al. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods 2019;8:92. [CrossRef]

- Yoo S, Jung S-C, Kwak K, Kim J-S. The Role of Prebiotics in Modulating Gut Microbiota: Implications for Human Health. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:4834. [CrossRef]

- Locantore P, Del Gatto V, Gelli S, Paragliola RM, Pontecorvi A. The Interplay between Immune System and Microbiota in Osteoporosis. Mediators Inflamm 2020;2020:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Pandey KavitaR, Naik SureshR, Vakil BabuV. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics- a review. J Food Sci Technol 2015;52:7577–87. [CrossRef]

- Whisner CM, Castillo LF. Prebiotics, Bone and Mineral Metabolism. Calcif Tissue Int 2018;102:443–79. [CrossRef]

- Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 2012;486:222–7. [CrossRef]

- Yadav D, Ghosh TS, Mande SS. Global investigation of composition and interaction networks in gut microbiomes of individuals belonging to diverse geographies and age-groups. Gut Pathog 2016;8:17. [CrossRef]

- Saponaro F, Bertolini A, Baragatti R, Galfo L, Chiellini G, Saba A, et al. Myokines and Microbiota: New Perspectives in the Endocrine Muscle–Gut Axis. Nutrients 2024;16:4032. [CrossRef]

- Chenhuichen C, Cabello-Olmo M, Barajas M, Izquierdo M, Ramírez-Vélez R, Zambom-Ferraresi F, et al. Impact of probiotics and prebiotics in the modulation of the major events of the aging process: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Exp Gerontol 2022;164:111809. [CrossRef]

- Sotoudegan F, Daniali M, Hassani S, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Reappraisal of probiotics’ safety in human. Food Chem Toxicol 2019;129:22–9. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou S. Sarcopenia: A Contemporary Health Problem among Older Adult Populations. Nutrients 2020;12:1293. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Chen Y. The potential mechanism of the microbiota-gut-bone axis in osteoporosis: a review. Osteoporos Int 2022;33:2495–506. [CrossRef]

- Liao X, Wu M, Hao Y, Deng H. Exploring the Preventive Effect and Mechanism of Senile Sarcopenia Based on “Gut–Muscle Axis.” Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020;8:590869. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Peng F, Yang H, Luo J, Zhang L, Chen X, et al. Probiotics and muscle health: the impact of Lactobacillus on sarcopenia through the gut-muscle axis. Front Microbiol 2025;16:1559119. [CrossRef]

- Ticinesi A, Lauretani F, Milani C, Nouvenne A, Tana C, Del Rio D, et al. Aging Gut Microbiota at the Cross-Road between Nutrition, Physical Frailty, and Sarcopenia: Is There a Gut–Muscle Axis? Nutrients 2017;9:1303. [CrossRef]

- Wang G, Li Y, Liu H, Yu X. Gut microbiota in patients with sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Microbiol 2025;16:1513253. [CrossRef]

- Lou J, Wang Q, Wan X, Cheng J. Changes and correlation analysis of intestinal microflora composition, inflammatory index, and skeletal muscle mass in elderly patients with sarcopenia. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2024;24:140–6. [CrossRef]

- Picca A, Ponziani FR, Calvani R, Marini F, Biancolillo A, Coelho-Júnior HJ, et al. Gut Microbial, Inflammatory and Metabolic Signatures in Older People with Physical Frailty and Sarcopenia: Results from the BIOSPHERE Study. Nutrients 2019;12:65. [CrossRef]

- Yi R, Feng M, Chen Q, Long X, Park K-Y, Zhao X. The Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum CQPC02 on Fatigue and Biochemical Oxidation Levels in a Mouse Model of Physical Exhaustion. Front Nutr 2021;8:641544. [CrossRef]

- Herman MA. Glucose transport and sensing in the maintenance of glucose homeostasis and metabolic harmony. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1767–75. [CrossRef]

- Vial G, Coudy-Gandilhon C, Pinel A, Wauquier F, Chevenet C, Béchet D, et al. Lipid accumulation and mitochondrial abnormalities are associated with fiber atrophy in the skeletal muscle of rats with collagen-induced arthritis. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2020;1865:158574. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Lei P. Efficacy of probiotic supplements in the treatment of sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2025;20:e0317699. [CrossRef]

- Lee M-C, Tu Y-T, Lee C-C, Tsai S-C, Hsu H-Y, Tsai T-Y, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum TWK10 Improves Muscle Mass and Functional Performance in Frail Older Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Microorganisms 2021;9:1466. [CrossRef]

- Artoni De Carvalho JA, Magalhães LR, Polastri LM, Batista IET, De Castro Bremer S, Caetano HRDS, et al. Prebiotics improve osteoporosis indicators in a preclinical model: systematic review with meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 2023;81:891–903. [CrossRef]

- Sun J. Dietary vitamin D, vitamin D receptor, and microbiome. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2018;21:471–4. [CrossRef]

- Jones ML, Martoni CJ, Prakash S. Oral Supplementation With Probiotic L. reuteri NCIMB 30242 Increases Mean Circulating 25-Hydroxyvitamin D: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:2944–51. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson AG, Sundh D, Bäckhed F, Lorentzon M. Lactobacillus reuteri reduces bone loss in older women with low bone mineral density: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, clinical trial. J Intern Med 2018;284:307–17. [CrossRef]

- Wu S, Yoon S, Zhang Y-G, Lu R, Xia Y, Wan J, et al. Vitamin D receptor pathway is required for probiotic protection in colitis. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015;309:G341–9. [CrossRef]

- Sato K, Suematsu A, Okamoto K, Yamaguchi A, Morishita Y, Kadono Y, et al. Th17 functions as an osteoclastogenic helper T cell subset that links T cell activation and bone destruction. J Exp Med 2006;203:2673–82. [CrossRef]

- Dar HY, Pal S, Shukla P, Mishra PK, Tomar GB, Chattopadhyay N, et al. Bacillus clausii inhibits bone loss by skewing Treg-Th17 cell equilibrium in postmenopausal osteoporotic mice model. Nutrition 2018;54:118–28. [CrossRef]

- Dar HY, Shukla P, Mishra PK, Anupam R, Mondal RK, Tomar GB, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus inhibits bone loss and increases bone heterogeneity in osteoporotic mice via modulating Treg-Th17 cell balance. Bone Rep 2018;8:46–56. [CrossRef]

- Sapra L, Dar HY, Bhardwaj A, Pandey A, Kumari S, Azam Z, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus attenuates bone loss and maintains bone health by skewing Treg-Th17 cell balance in Ovx mice. Sci Rep 2021;11:1807. [CrossRef]

- Kassem A, Henning P, Kindlund B, Lindholm C, Lerner UH. TLR5, a novel mediator of innate immunity-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone loss. FASEB J 2015;29:4449–60. [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson C, Nigro G, Boneca IG, Bäckhed F, Sansonetti P, Sjögren K. Regulation of bone mass by the gut microbiota is dependent on NOD1 and NOD2 signaling. Cell Immunol 2017;317:55–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Sun J, Zhao H, Liu Y, Tang Z, Wen Y, et al. Alginate oligosaccharides relieve estrogen-deprived osteosarcopenia by affecting intestinal Th17 differentiation and systemic inflammation through the manipulation of bile acid metabolism. Int J Biol Macromol 2025;295:139581. [CrossRef]

- Schepper JD, Collins F, Rios-Arce ND, Kang HJ, Schaefer L, Gardinier JD, et al. Involvement of the Gut Microbiota and Barrier Function in Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 2020;35:801–20. [CrossRef]

- Zupan J, Komadina R, Marc J. The relationship between osteoclastogenic and anti-osteoclastogenic pro-inflammatory cytokines differs in human osteoporotic and osteoarthritic bone tissues. J Biomed Sci 2012;19:28. [CrossRef]

- Deng B, Wu J, Li X, Zhang C, Men X, Xu Z. Effects of Bacillus subtilis on growth performance, serum parameters, digestive enzyme, intestinal morphology, and colonic microbiota in piglets. AMB Express 2020;10:212. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Zhan K, Zhang M. Effects of the Use of a Combination of Two Bacillus Species on Performance, Egg Quality, Small Intestinal Mucosal Morphology, and Cecal Microbiota Profile in Aging Laying Hens. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2020;12:204–13. [CrossRef]

- Wallimann A, Magrath W, Thompson K, Moriarty T, Richards RG, Akdis CA, et al. Gut microbial-derived short-chain fatty acids and bone: a potential role in fracture healing. Eur Cell Mater 2021;41:454–70. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y-W, Cao M-M, Li Y-J, Dai G-C, Lu P-P, Zhang M, et al. The regulative effect and repercussion of probiotics and prebiotics on osteoporosis: involvement of brain-gut-bone axis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023;63:7510–28. [CrossRef]

- Lin H, Liu T, Li X, Gao X, Wu T, Li P. The role of gut microbiota metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide in functional impairment of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in osteoporosis disease. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1009–1009. [CrossRef]

- Gehart H, Van Es JH, Hamer K, Beumer J, Kretzschmar K, Dekkers JF, et al. Identification of Enteroendocrine Regulators by Real-Time Single-Cell Differentiation Mapping. Cell 2019;176:1158-1173.e16. [CrossRef]

- Larabi AB, Masson HLP, Bäumler AJ. Bile acids as modulators of gut microbiota composition and function. Gut Microbes 2023;15:2172671. [CrossRef]

- Li X-J, Fang C, Zhao R-H, Zou L, Miao H, Zhao Y-Y. Bile acid metabolism in health and ageing-related diseases. Biochem Pharmacol 2024;225:116313. [CrossRef]

- Mancin L, Wu GD, Paoli A. Gut microbiota–bile acid–skeletal muscle axis. Trends Microbiol 2023;31:254–69. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Gómez JG, López-Bonilla A, Trejo-Tapia G, Ávila-Reyes SV, Jiménez-Aparicio AR, Hernández-Sánchez H. In Vitro Bile Salt Hydrolase (BSH) Activity Screening of Different Probiotic Microorganisms. Foods 2021;10:674. [CrossRef]

- Joyce SA, MacSharry J, Casey PG, Kinsella M, Murphy EF, Shanahan F, et al. Regulation of host weight gain and lipid metabolism by bacterial bile acid modification in the gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2014;111:7421–6. [CrossRef]

- Sato Y, Atarashi K, Plichta DR, Arai Y, Sasajima S, Kearney SM, et al. Novel bile acid biosynthetic pathways are enriched in the microbiome of centenarians. Nature 2021;599:458–64. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y-X, Song Y-W, Zhang L, Zheng F-J, Wang X-M, Zhuang X-H, et al. Association between bile acid metabolism and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Clinics 2020;75:e1486. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).