Submitted:

21 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

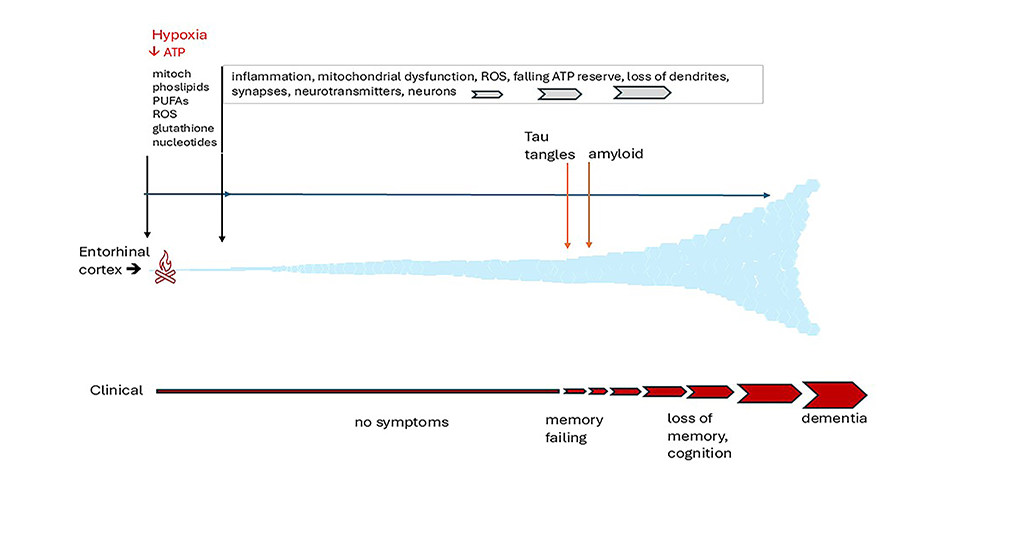

2. Brain Aging

3. A Role for ATP Depletion in the Genesis of AD

3.1. Matching ATP Production to Requirement in the Brain

3.2. Biosensors of ATP Status

3.2.1. AMPK

3.2.2. Sirtuins

3.2.3. Phosphofructokinase (PFK)

3.2.4. ATP Regulation by Mitochondrial Nucleotide Transporters

3.3. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 (HIF-1) Mediates the Response to Hypoxia

3.3.1. Hypoxia Up-Regulated Mitochondrial Movement Regulator (HUMMR)

3.4. Mitochondrial-Derived Peptides (MDPs) and Nuclear-Encoded Microproteins

3.5. Spectrun of Molecules Involved in ATP Turnover

4. Brain Processes with Very High ATP Consumption/Turnover

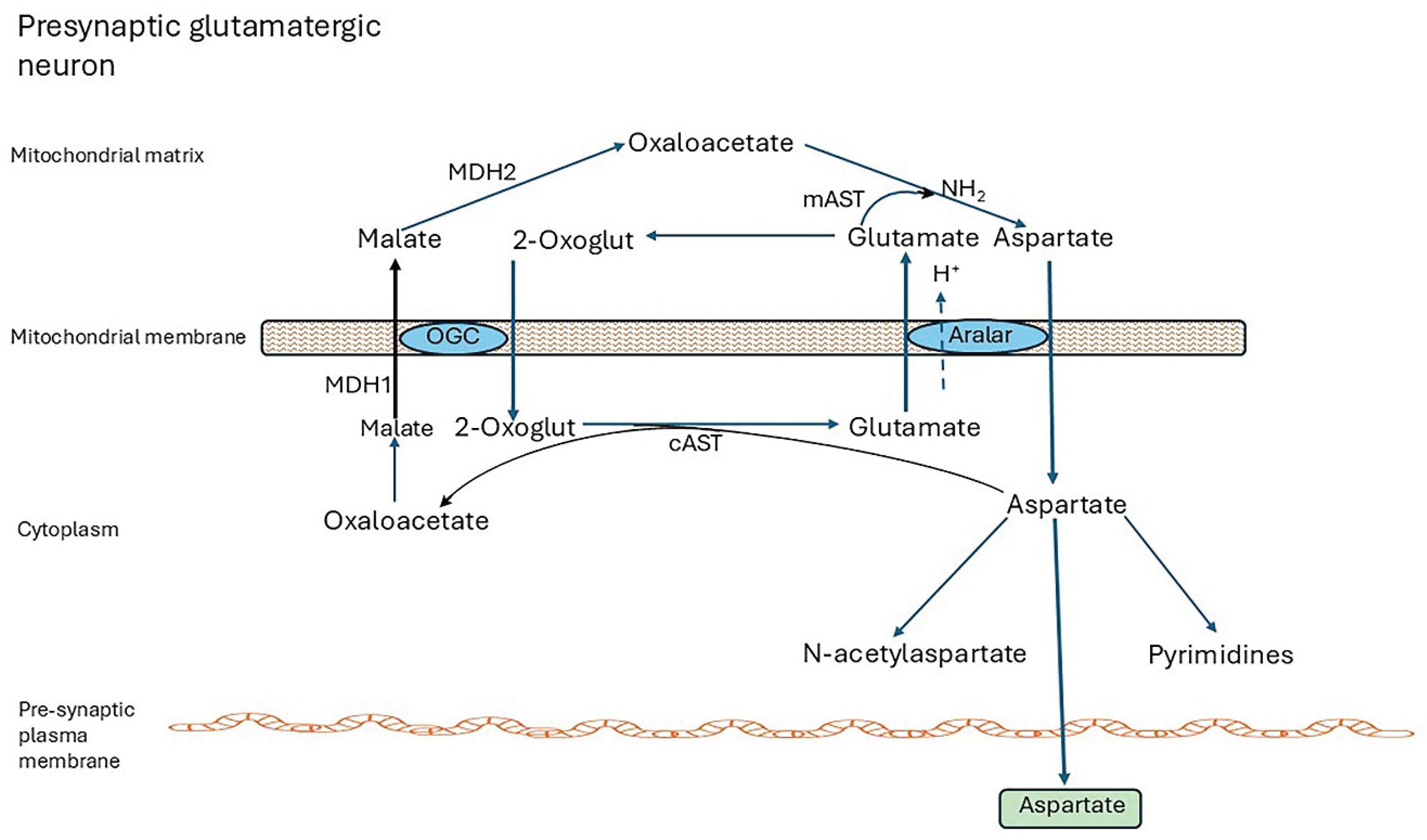

4.1. The Malate-Aspartate Shuttle

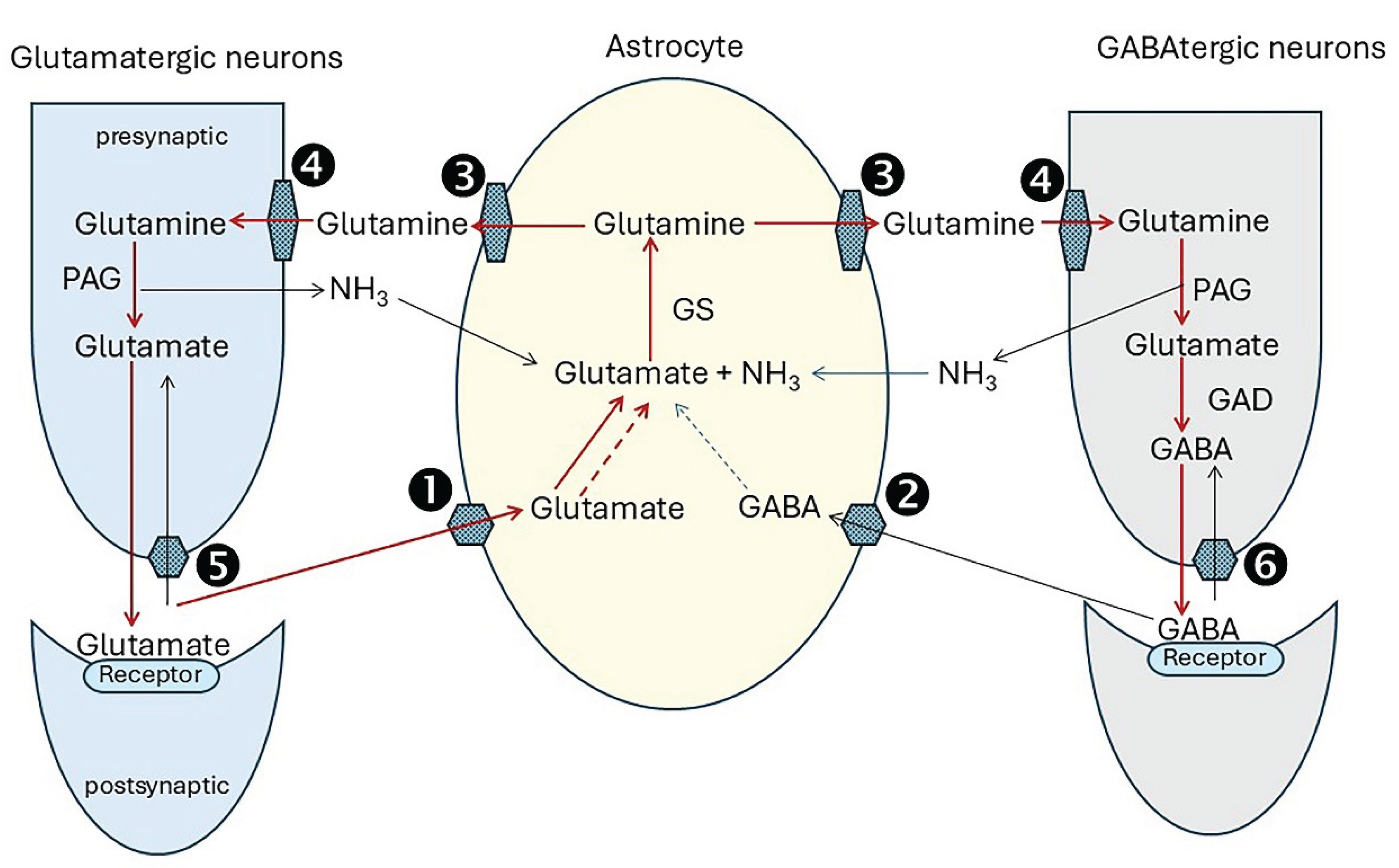

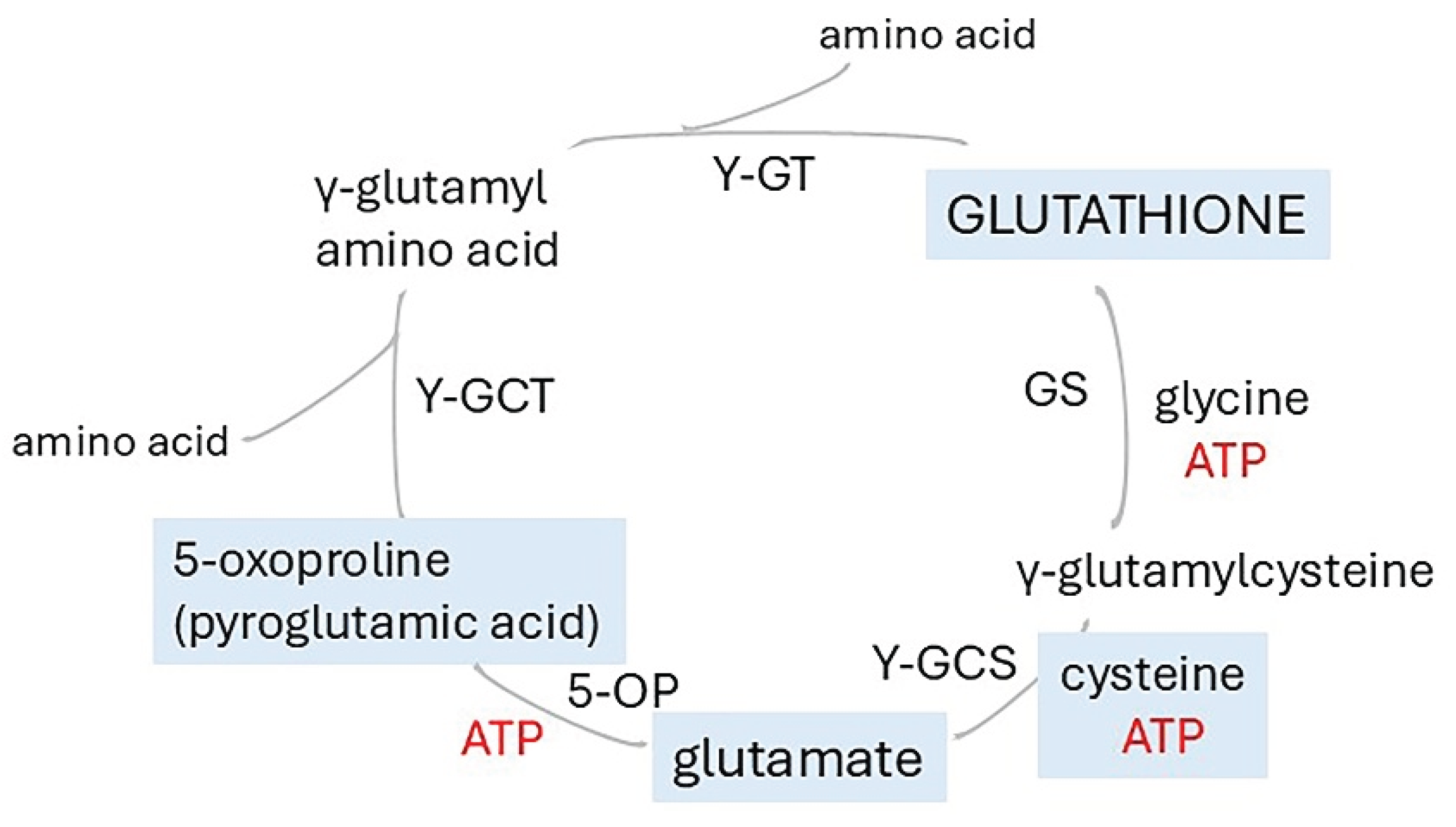

4.2. The Glutamate/GABA/Glutamine Cycle

4.2.1. The Energy Cost of the Glutamate/GABA/Glutamine Cycle

4.2.2. Disturbances of the Glutamate/GABA/Glutamine Cycle in AD

4.2.3. Effects of Hypoxia/Ischaemia on the Glutamate/GABA/Glutamine Cycle

4.2.4. Promoting Anaplerosis in Astrocytes to Support Glutamine Synthesis

4.3. Axonal Transport Has a High Energy Requirement

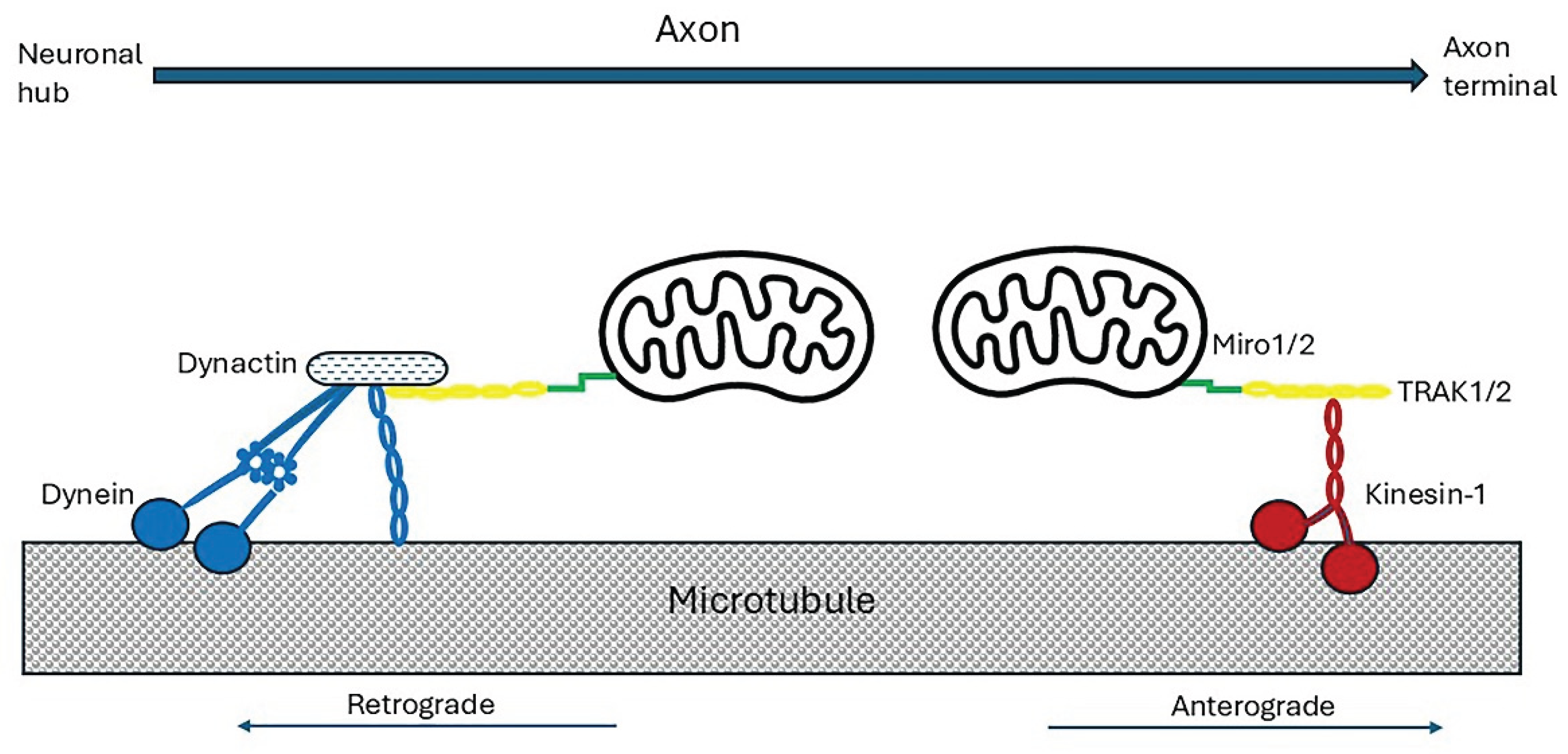

4.3.1. Axonal Transport of Mitochondria

4.3.2. Role of Tau Protein in Axon Transport

4.3.3. Disordered Axonal Transport in AD

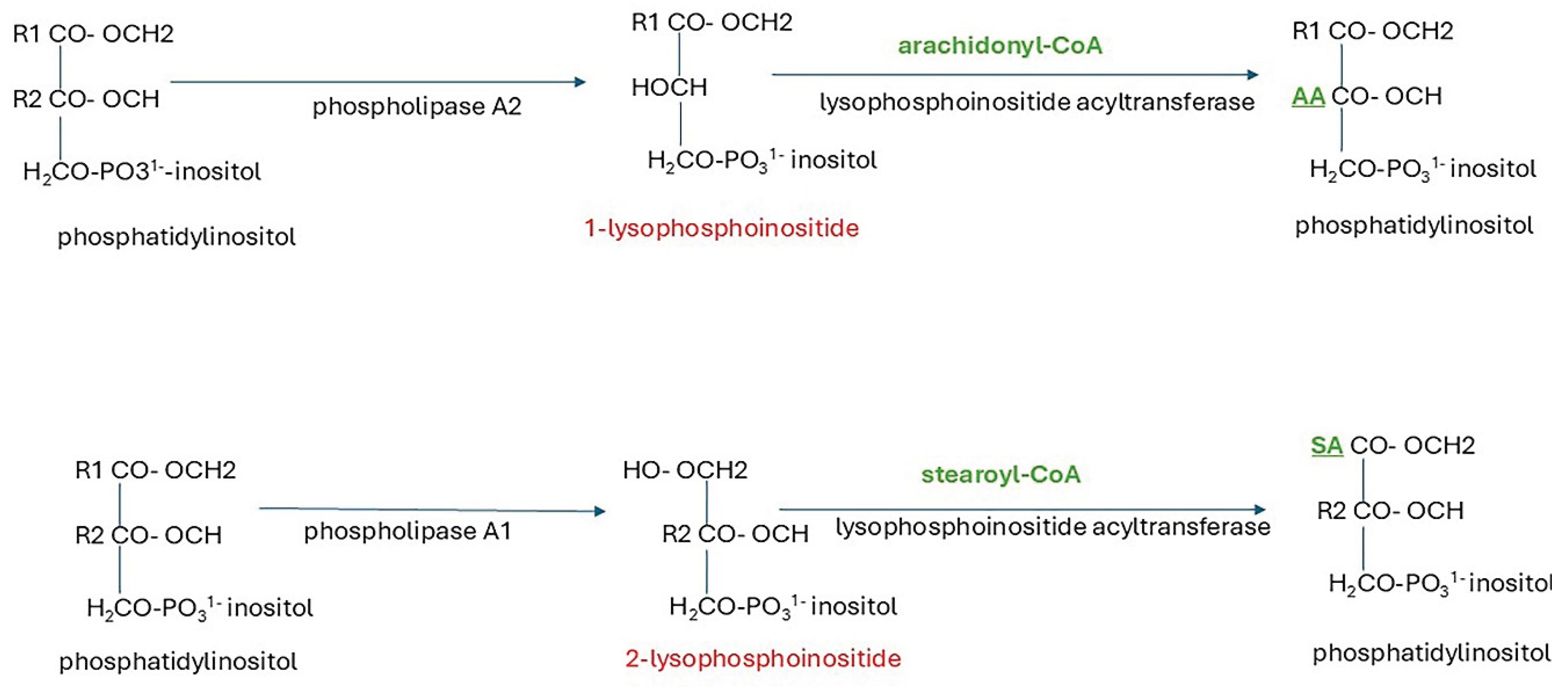

5. Effects of ATP Depletion on Lipid Metabolism

5.1. Glycerophospholipids

5.1.1. Synthesis

5.1.2. Physiological Functions

5.1.3. Pathophysiology

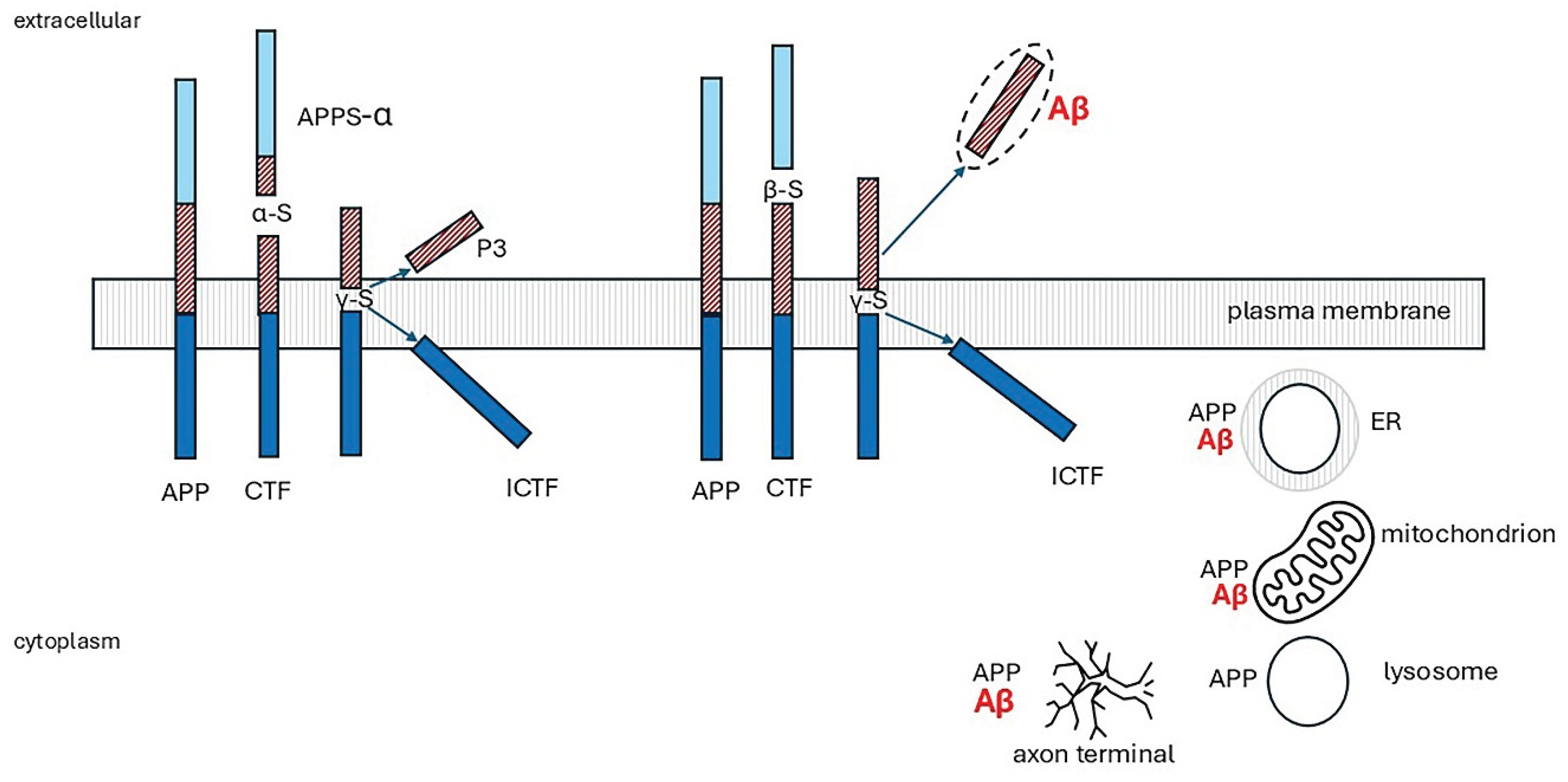

5.1.4. Potential Role of Disordered Membrane Phospholipids in Promoting Aβ Production from Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP)

5.1.5. Disturbances of Membrane Lipids in AD

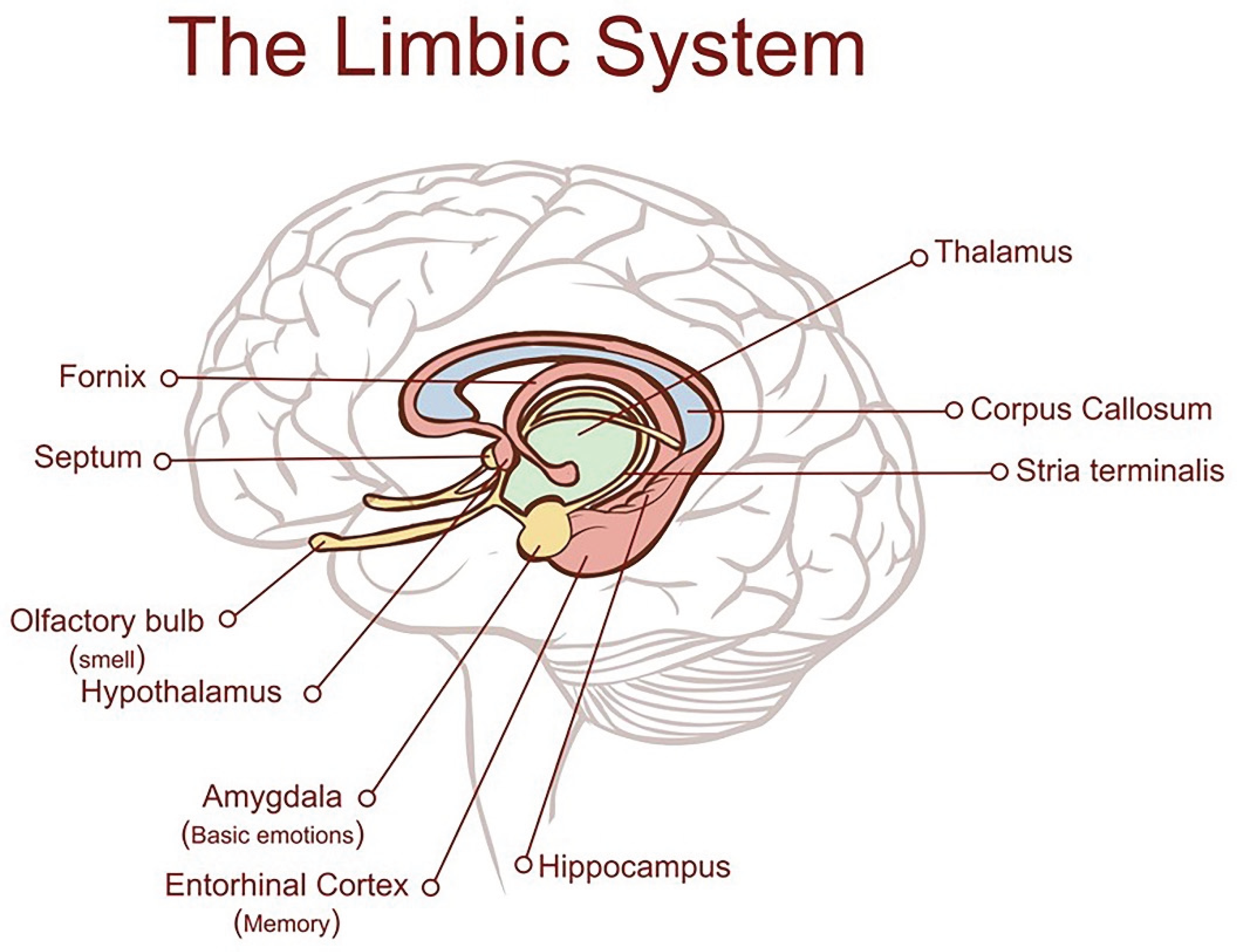

6. Hypoperfusion of the Hippocampus

6.1. Blood Supply to the Brain Cortex and Hippocampus

6.2. Features of the Hippocampal Vasculature Increase the Risk for Hypoperfusion

6.3. Neurovascular Coupling and the Effects of Hypoxia

6.4. Effects of Hypertension on Cerebral Blood Flow

7. Genomic, Proteomic, Metabolomic and Imaging Investigations to Identify Causative Genes and Pathways in AD

7.1. Human Studies

7.2. Animal Studies

| Study | Main relevant findings | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | CSF metabolome of a rabbit model for late onset AD with AD neuropathology induced by a high cholesterol diet | Profiles changed with time; Aβ-like plaques only seen at 12 weeks Four clusters identified in the top 95 metabolites, most at 12 weeks. At 12 weeks, decreased phospholipids, mainly phosphorylated fatty alcohols, akylacyl or dialkyl-glycerophosphates, all potential precursors or degradation products of phospholipids including phosphatidylcholines and plasmalogens. | Liu QY, Bingham EJ, Twine SM, et al., 2012 [26] |

| 22 | Cerebral cortical and glutamine metabolism in a mouse AD model (APPswe/PSEN1dE9) | AD mice: significantly increased lactate and alanine, decreased TCA intermediates, decreased capacity for uptake and oxidative metabolism of glutamine; no change in glial acetate metabolism. | Andersen JV, Christensen SK, Aldana BI, et al., 2017 [320] |

| 23 | Hippocampal proteomic pathways associated with memory status in normal aging and 5FXAD AD mouse model | Normal and AD mice, HDAC4 identified as regulator of memory-related proteins; Top pathways associated with memory deficits in controls: OXPHOS, mitochondrial dysfunction, glutamate receptor signalling; | Neuner SM, Wilmott LA, Hoffmann BR, et al., 2017 [321] |

| 24 | Investigation for overlap in protein expression up to 15m of normal mice following mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) aged 3m; and non-traumatised mice with AD (PSAPP and mice expressing hTau) up to 15m | Impaired in TBI: energy metabolism, clearance, neurotransmitter and intracellular signalling, glial cell function. Little overlap with altered proteins in AD models. TBI and AD damage distinct processes | Ojo JO, Crynen G, Algamal M, et al., 2020 [322] |

| 25 | Characterization of Tg4-42 mouse model for AD [323] | Significant loss of hippocampal CA1 neurons. At 9m caudate, putamen: significant decreases: GABA, glutamine, lactate: increased Aβ42, glutaminase, glutamine decarboxylase, CSF, increased neurofilament light chains (NFL) | Hinteregger B, Loeffler T, Flunkert S, et al., 2021 [323] |

| 26 | Metabolite analyses of cortex and hippocampus of a transgenic AD mouse model with high resolution magic angle spinning NMR. | Controls: changes with age in cortex; at 9m sex differences; at 9m differences from AD mice in hippocampus: glutamate, glutamine, Nacetylaspartate (NAA), glycine, phosphocholine and glycerophosphocholine. | Füzesi MV, Muti IH, Berker Y, et al. 2022 [324] |

| 27 | Investigation of mitochondrial dysfunction and effects of an antibody to a neurotoxic Tau peptide in hippocampus and retina of a mouse AD model | Decreased expression of genes involved in multiple energy generating mitochondrial pathways including OXPHOS pathways; FA oxidation; in the hippocampus and retina of Tg2576 AD mice; GSEA analysis: oxidative phosphorylation the most down-regulated gene set in hippocampus of early symptomatic Tg2576; mitochondrial alterations observed in AD mice significantly reverted by NH2htau antibody. | Morello G, Guarnaccia M, La Cognata V, et al., 2023 [325] |

8. Discussion

8.1. Suggestions for Further Study

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMPK 5′ | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| APH1 | (Anterior Pharynx defective 1) a component of the gamma-secretase complex. |

| APP | Amyloid Beta Precursor Protein |

| BACE | Beta-Secretase APP Beta-Secretase |

| BBB | blood brain barrier |

| CBF | cerebral blood flow, |

| rCBF | regional cerebral blood flow |

| FDG-PET | fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positive emission tomography (PET} |

| GSEA | gene set enrichment analysis |

| HDAC4 | Histone Deacetylase |

| HIF1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha |

| HUMMR | hypoxia up-regulated mitochondrial movement regulator |

| LOAD | late onset Alzheimers disease |

| MCI | Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| Miro1 and Miro2 | Mitochondrial Rho GTPase proteins |

| Mitochondrial-derived peptides: | |

| GAU | gene antisense ubiquitous |

| MOTS-c | Mitochondrial ORF of the 12S rRNA Type-C |

| MtALTND4 | protein encoded from an alternative open reading frame of the gene for the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4 (ND4) protein |

| SHLP1 -SHLP6 | six small humanin-like peptides with 20-35 amino acids |

| SHMOOSE | Small Human Mitochondrial ORF Over SErine tRNA. |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NFTs | neurofibrillary tangles, |

| PEN2 | Gamma-secretase subunit |

| PET | positive emission tomography |

| PS1/PS2 | Presenilin 1/ 2 |

| PUFAs | polyunsaturated fatty acids, |

| SAH | subarachnoid haemorrhage |

| SREBP-2 | Sterol regulatory-element binding protein-2, |

| Transgenic mouse models: | |

| Tg25476 AD mice | overexpress a mutated form of APP (the ‘Swedish mutation’). Develop amyloid plaques and cognitive deficits |

| APPswe/PSEN1dE9 (PSAPP) AD mice | carry two mutations: the Swedish mutation and a presenilin mutation 5xFAD mice express 5 mutations in two genes (APP and Presenilin-1); have increased Aβpeptide, amyloid plaques, cognitive deficits 3xTG mice express the Swedish mutation, a PSEN1 mutation , and a human Tau mutation Tg4-42 mouse model: Mouse model with N-truncated 4- 42 Aβ |

References

- Gómez-Isla T, Price JL, McKeel DW Jr, Morris JC, Growdon JH, Hyman BT. Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1996 Jul 15;16(14):4491-500. PMID: 8699259; PMCID: PMC6578866. [CrossRef]

- Morgan GR, Carlyle BC. Interrogation of the human cortical peptidome uncovers cell-type specific signatures of cognitive resilience against Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2024 Mar 26;14(1):7161. PMID: 38531951; PMCID: PMC10966065. [CrossRef]

- Thangavel R, Kempuraj D, Stolmeier D, Anantharam P, Khan M, Zaheer A. Glia maturation factor expression in entorhinal cortex of Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurochem Res. 2013 Sep;38(9):1777-84. Epub 2013 May 29. PMID: 23715664; PMCID: PMC3735652. [CrossRef]

- Kapadia A, Billimoria K, Desai P, Grist JT, Heyn C, Maralani P, et al. Hypoperfusion Precedes Tau Deposition in the Entorhinal Cortex: A Retrospective Evaluation of ADNI-2 Data. J Clin Neurol (2023) 19(2): 131–7. [CrossRef]

- Kahn I, Andrews-Hanna JR, Vincent JL, Snyder AZ, Buckner RL. Distinct cortical anatomy linked to subregions of the medial temporal lobe revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2008 Jul;100(1):129-39. Epub 2008 Apr 2. PMID: 18385483; PMCID: PMC2493488. [CrossRef]

- Torrico TJ, Abdijadid S. Neuroanatomy, Limbic System. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538491/.

- Patel A, Biso GMNR, Fowler JB. Neuroanatomy, Temporal Lobe. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519512/- accessed 15-06-2025.

- Baloyannis SJ. Mitochondrial alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. 2006:119–26. [CrossRef]

- Ryzhikova E, Ralbovsky NM, Sikirzhytski V, Kazakov O, Halamkova L, Quinn J, Zimmerman EA, Lednev IK. Raman spectroscopy and machine learning for biomedical applications: Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis based on the analysis of cerebrospinal fluid. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2021 Mar 5; 248:119188. Epub 2020 Nov 13. PMID: 33268033. [CrossRef]

- Yin F. Lipid metabolism and Alzheimer’s disease: clinical evidence, mechanistic link and therapeutic promise. FEBS J. 2023 Mar;290(6):1420-1453. Epub 2022 Jan 18. PMID: 34997690; PMCID: PMC9259766. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Li L, Cai S, Song K, Hu S. Identification of novel risk genes for Alzheimer’s disease by integrating genetics from hippocampus. Sci Rep. 2024 Nov 11;14(1):27484. PMID: 39523385; PMCID: PMC11551212. [CrossRef]

- Wu YY, Lee YS, Liu YL, Hsu WC, Ho WM, Huang YH, Tsai SJ, Kuo PH, Chen YC. Association study of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase polymorphism with Alzheimer Disease in the Taiwanese Population. Front Neurosci. 2021 Jan 22;15: 625885. PMID: 33551739; PMCID: PMC7862325. [CrossRef]

- Tsai CY, Wu SM, Kuan YC, Lin YT, Hsu CR, Hsu WH, Liu YS, Majumdar A, Stettler M, Yang CM, Lee KY, Wu D, Lee HC, Wu CJ, Kang JH, Liu WT. Associations between risk of Alzheimer’s disease and obstructive sleep apnea, intermittent hypoxia, and arousal responses: A pilot study. Front Neurol. 2022 Nov 30; 13:1038735. PMID: 36530623; PMCID: PMC9747943. [CrossRef]

- Adlimoghaddam A, Sabbir MG, Albensi BC. Ammonia as a Potential Neurotoxic Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016 Aug 8; 9: 57. PMID: 27551259; PMCID: PMC4976099. [CrossRef]

- Seiler N. Ammonia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int. 2002 Aug-Sep;41(2-3):189-207. PMID: 12020619. [CrossRef]

- Perkins M, Wolf AB, Chavira B, Shonebarger D, Meckel JP, Leung L, Ballina L, Ly S, Saini A, Jones TB, Vallejo J, Jentarra G, Valla J. Altered Energy Metabolism Pathways in the Posterior Cingulate in Young Adult Apolipoprotein E ɛ4 Carriers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016 Apr 23;53(1):95-106. PMID: 27128370; PMCID: PMC4942726. [CrossRef]

- Yen K, Miller B, Kumagai H, Silverstein A, Cohen P. Mitochondrial-derived microproteins: from discovery to function. Trends Genet. 2024 Dec 16: S0168-9525(24)00292-0. PMID: 39690001. [CrossRef]

- Tian J, Jia K, Wang T, Guo L, Xuan Z, Michaelis EK, Swerdlow RH; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; Du H. Hippocampal transcriptome-wide association study and pathway analysis of mitochondrial solute carriers in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2024 Jun 10;14(1):250. PMID: 38858380; PMCID: PMC11164935. [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard LT, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG, Frikke-Schmidt R. Loss-of-function mutation in ABCA1 and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11: 1430–8.

- Aikawa T, Holm ML, Kanekiyo T. ABCA7 and Pathogenic Pathways of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2018 Feb 5;8(2):27. PMID: 29401741; PMCID: PMC5836046. [CrossRef]

- De Roeck A, Van Broeckhoven C, Sleegers K. The role of ABCA7 in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from genomics, transcriptomics and methylomics. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138: 201–20. [CrossRef]

- Picard C, Julien C, Frappier J, Miron J, Théroux L, Dea D; United Kingdom Brain Expression Consortium and for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; Breitner JCS, Poirier J. Alterations in cholesterol metabolism-related genes in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2018 Jun; 66: 180.e1-180.e9. Epub 2018 Feb 9. PMID: 29503034. [CrossRef]

- Soleimani Zakeri NS, Pashazadeh S, MotieGhader H. Gene biomarker discovery at different stages of Alzheimer using gene co-expression network approach. Sci Rep. 2020 Jul 22;10(1):12210. PMID: 32699331; PMCID: PMC7376049. [CrossRef]

- Harold D, Abraham R, Hollingworth P, Sims R, Gerrish A, Hamshere ML, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009; 41:1088–93. [CrossRef]

- Lanoiselée HM, Nicolas G, Wallon D, Rovelet-Lecrux A, Lacour M, Rousseau S, Richard AC, Pasquier F, Rollin-Sillaire A, Martinaud O, et al. APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 mutations in early-onset Alzheimer disease: A genetic screening study of familial and sporadic cases. PLoS Med. 2017 Mar 28;14(3): e1002270. PMID: 28350801; PMCID: PMC5370101. [CrossRef]

- Liu QY, Bingham EJ, Twine SM, Geiger JD, Ghribi O. Metabolomic Identification in cerebrospinal fluid of the effects of high dietary cholesterol in a rabbit model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Metabolomics (Los Angel). 2012 Mar 29;2(3):109. PMID: 24851192; PMCID: PMC4026014.

- Naudi A, Cabre R, Jove M, Ayala V, Gonzalo H, Portero-Otin M, et al. Lipidomics of human brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2015;122: 33–89. [CrossRef]

- Han X. Neurolipidomics: challenges and developments. Front Biosci. 2007 Jan 1;12:2601-15. PMID: 17127266; PMCID: PMC2141543. [CrossRef]

- Sastry PS. Sastry PS. Lipids of nervous tissue: composition and metabolism. Prog Lipid Res. 1985;24(2):69-176. PMID: 3916238. [CrossRef]

- Lamari F, Rossignol F, Mitchell GA. Glycerophospholipids: Roles in Cell Trafficking and Associated Inborn Errors. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2025 Mar;48(2): e70019. PMID: 40101691; PMCID: PMC11919462. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Lipid peroxidation, oxygen radicals, cell damage, and antioxidant therapy. Lancet. 1984 Jun 23;1(8391):1396-7. PMID: 6145845. [CrossRef]

- Walker V, Pickard JD. Prostaglandins, thromboxane, leukotrienes and the cerebral circulation in health and disease. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1985;12: 3-90. PMID: 3002404. [CrossRef]

- Feringa FM, van der Kant R. Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s Disease; from risk genes to pathological effects. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021 Jun 24;13: 690372. PMID: 34248607; PMCID: PMC8264368. [CrossRef]

- Vetrivel KS, Thinakaran G. Membrane rafts in Alzheimer’s disease beta-amyloid production. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Aug;1801(8): 860-7. Epub 2010 Mar 18. PMID: 20303415; PMCID: PMC2886169. [CrossRef]

- Jin U, Park SJ, Park SM. Cholesterol Metabolism in the Brain and Its Association with Parkinson’s Disease. Exp Neurobiol. 2019 Oct 31;28(5):554-567. PMID: 31698548; PMCID: PMC6844. [CrossRef]

- Johnson AC. Hippocampal vascular supply and its role in vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke. 2023 Mar;54(3):673-685. Epub 2023 Feb 27. PMID: 36848422; PMCID: PMC9991081. [CrossRef]

- Petralia RS, Mattson MP, Yao PJ. Communication breakdown: the impact of ageing on synapse structure. Ageing Res Rev. 2014 Mar;14: 31-42. Epub 2014 Feb 2. PMID: 24495392; PMCID: PMC4094371. [CrossRef]

- Ledig C, Schuh A, Guerrero R, Heckemann RA, Rueckert D. Structural brain imaging in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: biomarker analysis and shared morphometry database. Sci Rep. 2018; 8: 11258. [CrossRef]

- Ingram T, Chakrabarti L. Proteomic profiling of mitochondria: what does it tell us about the ageing brain? Aging (Albany NY). 2016 Dec 13;8(12):3161-3179. PMID: 27992860; PMCID: PMC5270661. [CrossRef]

- Boveris A, Navarro A. Brain mitochondrial dysfunction in aging. IUBMB Life. 2008 May;60(5):308-14. PMID: 18421773. [CrossRef]

- Ferrándiz ML, Martínez M, De Juan E, Díez A, Bustos G, Miquel J. Impairment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in the brain of aged mice. Brain Res. 1994; 644: 335–38. [CrossRef]

- Mather M, Rottenberg H. Aging enhances the activation of the permeability transition pore in mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000; 273:603–08. [CrossRef]

- Bratic A, Larsson NG. The role of mitochondria in aging. J Clin Invest. 2013 Mar;123(3):951-7. Epub 2013 Mar 1. PMID: 23454757; PMCID: PMC3582127. [CrossRef]

- Stauch KL, Purnell PR, Fox HS. Aging synaptic mitochondria exhibit dynamic proteomic changes while maintaining bioenergetic function. Aging (Albany NY). 2014 Apr;6(4):320-34. PMID: 24827396; PMCID: PMC4032798. [CrossRef]

- Stauch KL, Purnell PR, Villeneuve LM, Fox HS. Proteomic analysis and functional characterization of mouse brain mitochondria during aging reveal alterations in energy metabolism. Proteomics. 2015;15: 1574–86. [CrossRef]

- Groebe K, Krause F, Kunstmann B, Unterluggauer H, Reifschneider NH, Scheckhuber CQ, Sastri C, Stegmann W, Wozny W, Schwall GP, Poznanović S, Dencher NA, Jansen-Dürr P, et al. Differential proteomic profiling of mitochondria from Podospora anserina, rat and human reveals distinct patterns of age-related oxidative changes. Exp Gerontol. 2007; 42:887–98. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Pan J, Xin Y, Mi X, Wang J, Gao Q, Luo H. Gene expression analysis reveals novel gene signatures between young and old adults in human prefrontal cortex. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018 Aug 27;10: 259. PMID: 30210331; PMCID: PMC6119720. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabrera MC, Ferrando B, Brioche T, Sanchis-Gomar F, Viña J. Exercise and antioxidant supplements in the elderly. J Sport Health Sci. 2013; 2: 94–100. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan M, Kenworthy AK. Lipid peroxidation drives liquid-liquid phase separation and disrupts raft protein partitioning in biological membranes. J Am Chem Soc. 2024 Jan 17;146(2):1374-1387. PMID: 37745342; PMCID: PMC10515805. [CrossRef]

- Berchtold NC, Coleman PD, Cribbs DH, Rogers J, Gillen DL, Cotman CW. Synaptic genes are extensively downregulated across multiple brain regions in normal human aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013 Jun;34(6):1653-61. Epub 2012 Dec 27. PMID: 23273601; PMCID: PMC4022280. [CrossRef]

- Garin CM, Nadkarni NA, Pépin J, Flament J, Dhenain M. Whole brain mapping of glutamate distribution in adult and old primates at 11.7T. Neuroimage. 2022 May 1; 251:118984. Epub 2022 Feb 8. PMID: 35149230. [CrossRef]

- Trefts E, Shaw RJ. AMPK: restoring metabolic homeostasis over space and time. Mol Cell. 2021 Sep 16;81(18):3677-3690. PMID: 34547233; PMCID: PMC8549486. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti P, Fovez Q, Germain N, Khamari R, Kluza J. Mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity: mechanisms, regulation, and significance in non-transformed and cancer cells. FASEB j. 2020;34(10):13106–13124. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira T, Rodriguez S. Mitochondrial DNA: Inherent Complexities Relevant to Genetic Analyses. Genes (Basel). 2024 May 12;15(5):617. PMID: 38790246; PMCID: PMC11121663. [CrossRef]

- Mercer TR, Neph S, Dinger ME, Crawford J, Smith MA, Shearwood AM, Haugen E, Bracken CP, Rackham O, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Filipovska A, Mattick JS, The human mitochondrial transcriptome, Cell 146 (2011) 645–658. PubMed: 21854988. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen QL, Corey C, White P, et al. Platelets from pulmonary hypertension patients show increased mitochondrial reserve capacity. JCI Insight. 2018; 2:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Hardie DG, Schaffer BE, Brunet A, 2016. AMPK: An Energy-Sensing Pathway with Multiple Inputs and Outputs. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 190–201. [CrossRef]

- Hardie DG. Keeping the home fires burning: AMP-activated protein kinase. J R Soc Interface. 2018 Jan;15(138):20170774. PMID: 29343628; PMCID: PMC5805978. [CrossRef]

- Jeon SM. Regulation and function of AMPK in physiology and diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2016 Jul 15;48(7): e245. PMID: 27416781; PMCID: PMC4973318. [CrossRef]

- Thapa R, Moglad E, Afzal M, Gupta G, Bhat AA, Hassan Almalki W, Kazmi I, Alzarea SI, Pant K, Singh TG, Singh SK, Ali H. The role of sirtuin 1 in ageing and neurodegenerative disease: A molecular perspective. Ageing Res Rev. 2024 Dec;102: 102545. Epub 2024 Oct 17. PMID: 39423873. [CrossRef]

- Yang JH, Hayano M, Griffin PT, Amorim JA, Bonkowski MS, Apostolides JK, Salfati EL, Blanchette M, Munding EM, Bhakta M, et al. Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian aging. Cell. 2023 Jan 19;186(2):305-326.e27. Epub 2023 Jan 12. Erratum in: Cell. 2024 Feb 29;187(5):1312-1313. Doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.01.049. PMID: 36638792; PMCID: PMC10166133. [CrossRef]

- Razick DI, Akhtar M, Wen J, Alam M, Dean N, Karabala M, Ansari U, Ansari Z, Tabaie E, Siddiqui S. The Role of Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) in Neurodegeneration. Cureus. 2023 Jun 15;15(6): e40463. PMID: 37456463; PMCID: PMC10349546. [CrossRef]

- Wu QJ, Zhang TN, Chen HH, Yu XF, Lv JL, Liu YY, Liu YS, Zheng G, Zhao JQ, Wei YF, Guo JY, Liu FH, Chang Q, Zhang YX, Liu CG, Zhao YH. The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Dec 29;7(1):402. PMID: 36581622; PMCID: PMC9797940. [CrossRef]

- Burtscher J, Denti V, Gostner JM, Weiss AK, Strasser B, Hüfner K, Burtscher M, Paglia G, Kopp M, Dünnwald T. The interplay of NAD and hypoxic stress and its relevance for ageing. Ageing Res Rev. 2025 Feb; 104:102646. Epub 2024 Dec 20. PMID: 39710071. [CrossRef]

- Carafa V, Rotili D, Forgione M, Cuomo F, Serretiello E, Hailu GS, Jarho E, Lahtela-Kakkonen M, Mai A, Altucci L. Sirtuin functions and modulation: from chemistry to the clinic. Clin Epigenetics. 2016 May 25;8:61. PMID: 27226812; PMCID: PMC4879741. [CrossRef]

- Cantó C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, Elliott PJ, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009 Apr 23;458(7241):1056-60. PMID: 19262508; PMCID: PMC3616311. [CrossRef]

- Lan F, Cacicedo JM, Ruderman N, Ido Y. SIRT1 modulation of the acetylation status, cytosolic localization, and activity of LKB1. Possible role in AMP-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2008 Oct 10;283(41):27628-27635. Epub 2008 Aug 7. PMID: 18687677; PMCID: PMC2562073. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, Chao Y, Zhang J, Jia Y, Tie J, Hu D. Regulation of SIRT1 and Its Roles in Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2022 Mar 11;13:831168. PMID: 35359990; PMCID: PMC8962665. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Wu Z, Zhao P. The protective effects of activating Sirt1/NF-κB pathway for neurological disorders. Rev Neurosci. 2021 Nov 8;33(4):427-438. PMID: 34757706. [CrossRef]

- Sarubbo F, Esteban S, Miralles A, Moranta D. Effects of Resveratrol and other Polyphenols on Sirt1: Relevance to Brain Function During Aging. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018 Jan 30;16(2):126-136. PMID: 28676015; PMCID: PMC5883375. [CrossRef]

- Cimen H, Han MJ, Yang Y, Tong Q, Koc H, Koc EC. Regulation of succinate dehydrogenase activity by SIRT3 in mammalian mitochondria. Biochemistry. 2010 Jan 19;49(2):304-11. PMID: 20000467; PMCID: PMC2826167. [CrossRef]

- He J, Liu X, Su C, Wu F, Sun J, Zhang J, Yang X, Zhang C, Zhou Z, Zhang X, Lin X, Tao J. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Oxidative Damage Improves Reendothelialization Capacity of Endothelial Progenitor Cells via SIRT3 (Sirtuin 3)-Enhanced SOD2 (Superoxide Dismutase 2) Deacetylation in Hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019 Aug;39(8):1682-1698. Epub 2019 Jun 13. PMID: 31189433. [CrossRef]

- Kunji ERS, King MS, Ruprecht JJ, Thangaratnarajah C. The SLC25 Carrier Family: Important Transport Proteins in Mitochondrial Physiology and Pathology. Physiology (Bethesda). 2020 Sep 1;35(5):302-327. PMID: 32783608; PMCID: PMC7611780. [CrossRef]

- Bround MJ, Bers DM, Molkentin JD. A 20/20 view of ANT function in mitochondrial biology and necrotic cell death. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2020 Jul;144:A3-A13. Epub 2020 May 23. PMID: 32454061; PMCID: PMC7483807. [CrossRef]

- Gavaldà-Navarro A, Mampel T, Viñas O. Changes in the expression of the human adenine nucleotide translocase isoforms condition cellular metabolic/proliferative status. Open Biol. 2016 Feb;6(2):150108. PMID: 26842067; PMCID: PMC4772803. [CrossRef]

- Atlante A, Valenti D. A walk in the memory, from the first functional approach up to its regulatory role of mitochondrial bioenergetic flow in health and disease: focus on the adenine nucleotide translocator. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Apr 17;22(8):4164. PMID: 33920595; PMCID: PMC8073645. [CrossRef]

- Ho L, Titus AS, Banerjee KK, George S, Lin W, Deota S, Saha AK, Nakamura K, Gut P, Verdin E, Kolthur-Seetharam U. SIRT4 regulates ATP homeostasis and mediates a retrograde signaling via AMPK. Aging (Albany NY). 2013 Nov;5(11):835-49. PMID: 24296486; PMCID: PMC38687268. [CrossRef]

- Zhang P, Cheng X, Sun H, Li Y, Mei W, Zeng C. Atractyloside Protect Mice Against Liver Steatosis by Activation of Autophagy via ANT-AMPK-mTORC1 Signaling Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Sep 21;12:736655. PMID: 34621170; PMCID: PMC8490973. [CrossRef]

- Austin J, Aprille JR. Carboxyatractyloside-insensitive influx and efflux of adenine nucleotides in rat liver mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1984 Jan 10;259(1):154-60. PMID: 6706925. [CrossRef]

- del Arco A, Satrústegui J. Identification of a novel human subfamily of mitochondrial carriers with calcium-binding domains. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24701–24713. [CrossRef]

- Fiermonte G, De Leonardis F, Todisco S, Palmieri L, Lasorsa FM, Palmieri F. Identification of the mitochondrial ATP-Mg/Pi transporter. Bacterial expression, reconstitution, functional characterization, and tissue distribution. J Biol Chem. 2004;279: 30722–30730. [CrossRef]

- Aprille JR. Mechanism and regulation of the mitochondrial ATP-Mg/P(i) carrier. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1993;25:473–481. [CrossRef]

- Anunciado-Koza RP, Zhang J, Ukropec J, Bajpeyi S, Koza RA, Rogers RC, Cefalu WT, Mynatt RL, Kozak LP. Inactivation of the mitochondrial carrier SLC25A25 (ATP-Mg2+/Pi transporter) reduces physical endurance and metabolic efficiency in mice. J Biol Chem. 2011 Apr 1;286(13):11659-71. Epub 2011 Feb 4. PMID: 21296886; PMCID: PMC3064218. [CrossRef]

- Hofherr A, Seger C, Fitzpatrick F, Busch T, Michel E, Luan J, Osterried L, Linden F, Kramer-Zucker A, Wakimoto B, Schütze C, et al. The mitochondrial transporter SLC25A25 links ciliary TRPP2 signaling and cellular metabolism. PLoS Biol. 2018 Aug 6;16(8):e2005651. PMID: 30080851; PMCID: PMC6095617. [CrossRef]

- Hofherr A, Seger C, Fitzpatrick F, Busch T, Michel E, Luan J, Osterried L, Linden F, Kramer-Zucker A, Wakimoto B, Schütze C, et al. The mitochondrial transporter SLC25A25 links ciliary TRPP2 signaling and cellular metabolism, Supplement S2 Data. PLoS Biol 2018; 16(8): e2005651. [CrossRef]

- Lee JW, Bae SH, Jeong JW, Kim SH, Kim KW. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) alpha: its protein stability and biological functions. Exp Mol Med. 2004 Feb 29;36(1):1-12. PMID: 15031665. [CrossRef]

- Semenza GL. Regulation of mammalian O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15: 551-78. PMID: 1061197. [CrossRef]

- Semenza GL. HIF-1: mediator of physiological and pathophysiological responses to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000 Apr;88(4):1474-80. PMID: 10749844. [CrossRef]

- Cui C, Jiang X, Wang Y, Li C, Lin Z, Wei Y, Ni Q. Cerebral Hypoxia-Induced Molecular Alterations and Their Impact on the Physiology of Neurons and Dendritic Spines: A Comprehensive Review. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2024 Aug 6;44(1):58. PMID: 39105862; PMCID: PMC11303443. [CrossRef]

- Lin TK, Huang CR, Lin KJ, Hsieh YH, Chen SD, Lin YC, Chao AC, Yang DI. Potential Roles of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 in Alzheimer’s Disease: Beneficial or Detrimental? Antioxidants (Basel). 2024 Nov 11;13(11):1378. PMID: 39594520; PMCID: PMC11591038. [CrossRef]

- Arany Z, Huang LE, Eckner R, Bhattacharya S, Jiang C, Goldberg MA, Bunn HF, Livingston DM. An essential role for p300/CBP in the cellular response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93:12969-73. [CrossRef]

- Ema M, Hirota K, Mimura J, Abe H, Yodoi J, Sogawa K, Poellinger L, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Molecular mechanisms of transcription activation by HLF and HIF1alpha in response to hypoxia: their stabilization and redox signal-induced interaction with CBP/p300. EMBO J 1999; 18:1905-14. [CrossRef]

- Minet E, Mottet D, Michel G, Roland I, Raes M, Remacle J, Michiels C. Hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1: role of HIF-1alpha-Hsp90 interaction. FEBS Lett 1999; 460: 251-6. [CrossRef]

- Carrero P, Okamoto K, Coumailleau P, O’Brien S, Tanaka H, Poellinger L. Redox-regulated recruitment of the transcriptional coactivators CREB-binding protein and SRC-1 to hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2000 Jan;20(1):402-15. PMID: 10594042; PMCID: PMC85095. [CrossRef]

- Mole D.R., Blancher C., Copley R.R., Pollard P.J., Gleadle J.M., Ragoussis J., Ratcliffe P.J. Genome-wide association of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha DNA binding with expression profiling of hypoxia-inducible transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 2009; 284:16767–16775. [CrossRef]

- Lok CN, Ponka P. Identification of a hypoxia response element in the transferrin receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1999 Aug 20;274(34):24147-52. PMID: 10446188. [CrossRef]

- Lei L., Feng J., Wu G., Wei Z., Wang J.Z., Zhang B., Liu R., Liu F., Wang X., Li H.L. HIF-1alpha causes LCMT1/PP2A deficiency and mediates tau hyperphosphorylation and cognitive dysfunction during chronic hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022; 23:16140. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Lim S, Hoffman D, Aspenstrom P, Federoff HJ, Rempe DA. HUMMR, a hypoxia- and HIF-1alpha-inducible protein, alters mitochondrial distribution and transport. J Cell Biol. 2009 Jun 15;185(6):1065-81. PMID: 19528298; PMCID: PMC2711615. [CrossRef]

- Miller B, Kim SJ, Kumagai H, Mehta HH, Xiang W, Liu J, Yen K, Cohen P. Peptides derived from small mitochondrial open reading frames: Genomic, biological, and therapeutic implications. Exp Cell Res. 2020 Aug 15;393(2):112056. Epub 2020 May 6. PMID: 32387288; PMCID: PMC7778388. [CrossRef]

- Miller B, Kim SJ, Kumagai H, Yen K, Cohen P. Mitochondria-derived peptides in aging and healthspan. J Clin Invest. 2022 May 2;132(9):e158449. PMID: 35499074; PMCID: PMC9057581. [CrossRef]

- Mercer TR, Neph S, Dinger ME, Crawford J, Smith MA, Shearwood AM, Haugen E, Bracken CP, Rackham O, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Filipovska A, Mattick JS, The human mitochondrial transcriptome, Cell 146 (2011) 645–658. PubMed: 21854988. [CrossRef]

- Cobb LJ, Lee C, Xiao J, Yen K, Wong RG, Nakamura HK, Mehta HH, Gao Q, Ashur C, Huffman DM, et al. Naturally occurring mitochondrial-derived peptides are age-dependent regulators of apoptosis, insulin sensitivity, and inflammatory markers. Aging (Albany NY). 2016 Apr;8(4):796-809. PMID: 27070352; PMCID: PMC4925829. [CrossRef]

- Lee C, Zeng J, Drew BG, Sallam T, Martin-Montalvo A, Wan J, Kim SJ, Mehta H, Hevener AL, de Cabo R,et al.The mitochondrial-derived peptide MOTS-c promotes metabolic homeostasis and reduces obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2015 Mar 3;21(3):443-54. PMID: 25738459; PMCID: PMC4350682. [CrossRef]

- Kienzle L, Bettinazzi S, Choquette T, Brunet M, Khorami HH, Jacques JF, Moreau M, Roucou X, Landry CR, Angers A, Breton S. A small protein coded within the mitochondrial canonical gene nd4 regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics. BMC Biol. 2023 May 18;21(1):111. PMID: 37198654; PMCID: PMC10193809. [CrossRef]

- Yen K, Mehta HH, Kim SJ, Lue Y, Hoang J, Guerrero N, Port J, Bi Q, Navarrete G, Brandhorst S, et al. The mitochondrial derived peptide humanin is a regulator of lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY). 2020 Jun 23;12(12):11185-11199. Epub 2020 Jun 23. PMID: 32575074; PMCID: PMC7343442. [CrossRef]

- Rathore A, Chu Q, Tan D, Martinez TF, Donaldson CJ, Diedrich JK, Yates JR 3rd, Saghatelian A. MIEF1 Microprotein Regulates Mitochondrial Translation. Biochemistry. 2018 Sep 25;57(38):5564-5575. Epub 2018 Sep 14. PMID: 30215512; PMCID: PMC6443411. [CrossRef]

- Stein CS, Jadiya P, Zhang X, McLendon JM, Abouassaly GM, Witmer NH, Anderson EJ, Elrod JW, Boudreau RL. Mitoregulin: A lncRNA-Encoded Microprotein that Supports Mitochondrial Supercomplexes and Respiratory Efficiency. Cell Rep. 2018 Jun 26;23(13):3710-3720.e8. PMID: 29949756; PMCID: PMC6091870. [CrossRef]

- Makarewich CA, Baskin KK, Munir AZ, Bezprozvannaya S, Sharma G, Khemtong C, Shah AM, McAnally JR, Malloy CR, Szweda LI, et al. MOXI is a mitochondrial micropeptide that enhances fatty acid beta-oxidation, Cell Rep. 23 (2018) 3701–3709. [CrossRef]

- Lin YF, Xiao MH, Chen HX, Meng Y, Zhao N, Yang L, Tang H, Wang JL, Liu X, Zhu Y, Zhuang SM. A novel mitochondrial micropeptide MPM enhances mitochondrial respiratory activity and promotes myogenic differentiation. Cell Death Dis. 2019 Jul 11;10(7):528. PMID: 31296841; PMCID: PMC6624212. [CrossRef]

- Yen K, Wan J, Mehta HH, Miller B, Christensen A, Levine ME, Salomon MP, Brandhorst S, Xiao J, Kim SJ,etal. Humanin Prevents Age-Related Cognitive Decline in Mice and is Associated with Improved Cognitive Age in Humans. Sci Rep. 2018 Sep 21;8(1):14212. PMID: 30242290; PMCID: PMC6154958. [CrossRef]

- Miller B, Arpawong TE, Jiao H, Kim SJ, Yen K, Mehta HH, Wan J, Carpten JC, Cohen P. Comparing the Utility of Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA to Adjust for Genetic Ancestry in Association Studies. Cells. 2019 Apr 3;8(4):306. PMID: 30987182; PMCID: PMC6523867. [CrossRef]

- Bennett NK, Nguyen MK, Darch MA, Nakaoka HJ, Cousineau D, Ten Hoeve J, Graeber TG, Schuelke M, Maltepe E, Kampmann M, Mendelsohn BA, Nakamura JL, Nakamura K. Defining the ATPome reveals cross-optimization of metabolic pathways. Nat Commun. 2020 Aug 28;11(1):4319. PMID: 32859923; PMCID: PMC7455733. [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn BA, et al. A high-throughput screen of real-time ATP levels in individual cells reveals mechanisms of energy failure. PLoS Biol. 2018;16: e2004624. [CrossRef]

- Vinklarova L, Schmidt M, Benek O, Kuca K, Gunn-Moore F, Musilek K. Friend or enemy? Review of 17β-HSD10 and its role in human health or disease. J Neurochem. 2020 Nov;155(3):231-249. PMID: 32306391. [CrossRef]

- Zhang D, Yip YM, Li L. In silico construction of HK2-VDAC1 complex and investigating the HK2 binding-induced molecular gating mechanism of VDAC1. Mitochondrion. 2016;30: 222–228. [CrossRef]

- Minet E, Ernest I, Michel G, Roland I, Remacle J, Raes M, Michiels C. HIF1A gene transcription is dependent on a core promoter sequence encompassing activating and inhibiting sequences located upstream from the transcription initiation site and cis elements located within the 5′UTR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999 Aug 2;261(2):534-40. PMID: 10425220. [CrossRef]

- Broeks MH, Shamseldin HE, Alhashem A, Hashem M, Abdulwahab F, Alshedi T, Alobaid I, Zwartkruis F, Westland D, Fuchs S, Verhoeven-Duif NM, Jans JJM, Alkuraya FS. MDH1 deficiency is a metabolic disorder of the malate-aspartate shuttle associated with early onset severe encephalopathy. Hum Genet. 2019 Dec;138(11-12):1247-1257. Epub 2019 Sep 19. PMID: 31538237. [CrossRef]

- Pardo B, Herrada-Soler E, Satrústegui J, Contreras L, Del Arco A. AGC1 Deficiency: Pathology and Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of the Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 4;23(1):528. PMID: 35008954; PMCID: PMC8745132. [CrossRef]

- Lacabanne D, Sowton AP, Jose B, Kunji ERS, Tavoulari S. Current Understanding of Pathogenic Mechanisms and Disease Models of Citrin Deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2025 Mar;48(2):e70021. PMID: 40145619; PMCID: PMC11948450. [CrossRef]

- Palmieri L, Pardo B, Lasorsa FM, del Arco A, Kobayashi K, Iijima M, Runswick MJ, Walker JE, Saheki T, Satrústegui J, et al. Citrin and aralar1 are Ca (2+)-stimulated aspartate/glutamate transporters in mitochondria. EMBO J. 2001 Sep 17;20(18):5060-9. PMID: 11566871; PMCID: PMC125626. [CrossRef]

- Del Arco A, González-Moreno L, Pérez-Liébana I, Juaristi I, González-Sánchez P, Contreras L, Pardo B, Satrústegui J. Regulation of neuronal energy metabolism by calcium: Role of MCU and Aralar/malate-aspartate shuttle. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2023 Jun;1870(5):119468. Epub 2023 Mar 28. PMID: 36997074. [CrossRef]

- Cory JG. Purine and Pyrimidine Metabolism in Devlin TM Editor, Textbook of Biochemistry with clinical correlations Fifth Ed Wiley-Liss New York 2002; pp 825-860.

- Amaral A, Hadera MG, Kotter M, Sonnewald U. Oligodendrocytes Do Not Export NAA-Derived Aspartate In Vitro. Neurochem Res. 2017 Mar;42(3):827-837. Epub 2016 Jul 9. PMID: 27394419; PMCID: P. [CrossRef]

- Rosko L, Smith VN, Yamazaki R, Huang JK. Oligodendrocyte Bioenergetics in Health and Disease. Neuroscientist. 2019 Aug;25(4):334-343. Epub 2018 Aug 20. PMID: 30122106; PMCID: PMC674560MC5357468. [CrossRef]

- Broeks MH, van Karnebeek CDM, Wanders RJA, Jans JJM, Verhoeven-Duif NM. Inborn disorders of the malate aspartate shuttle. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021 Jul;44(4):792-808. Epub 2021 May 24. PMID: 33990986; PMCID: PMC836216. [CrossRef]

- Wolf NI, Van Der Knaap MS. AGC1 deficiency and cerebral hypomyelination. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(20):1997-1998. [CrossRef]

- Koch J, Broeks MH, Gautschi M, Jans J, Laemmle A. Inborn errors of the malate aspartate shuttle - Update on patients and cellular models. Mol Genet Metab. 2024 Aug;142(4):108520. Epub 2024 Jun 24. PMID: 38945121. [CrossRef]

- Ait-El-Mkadem S., Dayem-Quere M., Gusic M., Chaussenot A., Bannwarth S., Francois B., Genin E.C., Fragaki K., Volker-Touw C.L.M., Vasnier C., et al. Mutations in MDH2, encoding a Krebs cycle enzyme, cause early-onset severe encephalopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100: 151–159. [CrossRef]

- van Karnebeek CDM, Ramos RJ, Wen XY, Tarailo-Graovac M, Gleeson JG, Skrypnyk C, Brand-Arzamendi K, Karbassi F, Issa MY, van der Lee R,et al. Bi-allelic GOT2 Mutations Cause a Treatable Malate-Aspartate Shuttle-Related Encephalopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2019 Sep 5;105(3):534-548. Epub 2019 Aug 15. PMID: 31422819; PMCID: PMC6732527. [CrossRef]

- Jalil MA, Begum L, Contreras L, Pardo B, Iijima M, Li MX, Ramos M, Marmol P, Horiuchi M, Shimotsu K, et al. Reduced N-acetylaspartate levels in mice lacking aralar, a brain- and muscle-type mitochondrial aspartate-glutamate carrier. J Biol Chem. 2005 Sep 2;280(35):31333-9. Epub 2005 Jun 29. PMID: 15987682. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai T, Ramoz N, Barreto M, Gazdoiu M, Takahashi N, Gertner M, Dorr N, Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Perez G, et al. Slc25a12 disruption alters myelination and neurofilaments: a model for a hypomyelination syndrome and childhood neurodevelopmental disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010 May 1;67(9):887-94. Epub 2009 Dec 16. PMID: 20015484; PMCID: PMC4067545. [CrossRef]

- Llorente-Folch I, Sahún I, Contreras L, Casarejos MJ, Grau JM, Saheki T, Mena MA, Satrústegui J, Dierssen M, Pardo B. AGC1-malate aspartate shuttle activity is critical for dopamine handling in the nigrostriatal pathway. J Neurochem. 2013 Feb;124(3):347-62. PMID: 23216354. [CrossRef]

- Andersen JV, Schousboe A. Glial Glutamine Homeostasis in Health and Disease. Neurochem Res. 2023 Apr;48(4):1100-1128. Epub 2022 Nov 2. PMID: 363223. [CrossRef]

- Schousboe A, Bak LK, Waagepetersen HS. Astrocytic Control of Biosynthesis and Turnover of the Neurotransmitters Glutamate and GABA. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013 Aug 15;4: 102. PMID: 23966981; PMCID: PMC3744088. [CrossRef]

- Sidoryk-Węgrzynowicz M, Adamiak K, Strużyńska L. Astrocyte-Neuron Interaction via the Glutamate-Glutamine Cycle and Its Dysfunction in Tau-Dependent Neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Mar 6;25(5):3050. PMID: 38474295; PMCID: PMC10931567. [CrossRef]

- Derouiche A, Frotscher M. Astroglial processes around identified glutamatergic synapses contain glutamine synthetase: evidence for transmitter degradation. Brain Res. 1991 Jun 28;552(2):346-50. PMID: 1680531. [CrossRef]

- Walker V. Ammonia metabolism and hyperammonemic disorders. Adv Clin Chem. 2014;67:73-150. Epub 2014 Nov 4. PMID: 25735860. [CrossRef]

- Marx MC, Billups D, Billups B. Maintaining the presynaptic glutamate supply for excitatory neurotransmission. J Neurosci Res. 2015 Jul;93(7):1031-44. Epub 2015 Feb 3. PMID: 25648608. [CrossRef]

- Rothman DL, Behar KL, Hyder F, Shulman RG. In vivo NMR studies of the glutamate neurotransmitter flux and neuroenergetics: implications for brain function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003; 65: 401-27. Epub 2002 May 1. PMID: 12524459. [CrossRef]

- Sonnewald U. Glutamate synthesis has to be matched by its degradation - where do all the carbons go? J Neurochem. 2014 Nov;131(4):399-406. Epub 2014 Jul 23. PMID: 24989463. [CrossRef]

- Yu AC, Drejer J, Hertz L, Schousboe A. Pyruvate carboxylase activity in primary cultures of astrocytes and neurons. J Neurochem. 1983 Nov;41(5):1484-7. PMID: 6619879. [CrossRef]

- Schousboe A, Waagepetersen HS, Sonnewald U. Astrocytic pyruvate carboxylation: Status after 35 years. J Neurosci Res. 2019 Aug;97(8):890-896. Epub 2019 Feb 23. PMID: 30801795. [CrossRef]

- Bak LK, Walls AB, Schousboe A, Waagepetersen HS. Astrocytic glycogen metabolism in the healthy and diseased brain. J Biol Chem. 2018 May 11;293(19):7108-7116. Epub 2018 Mar 23. PMID: 29572349; PMCID: PMC5950001. [CrossRef]

- Zerangue N, Kavanaugh MP. Flux coupling in a neuronal glutamate transporter. Nature. 1996 Oct 17;383(6601):634-7. PMID: 8857541. [CrossRef]

- Bergles DE, Jahr CE. Synaptic activation of glutamate transporters in hippocampal astrocytes. Neuron. 1997 Dec;19(6):1297-308. PMID: 9427252. [CrossRef]

- Mennerick S, Zorumski CF. Glial contributions to excitatory neurotransmission in cultured hippocampal cells. Nature. 1994 Mar 3;368(6466):59-62. PMID: 7906399. [CrossRef]

- Robinson MB, Lee ML, DaSilva S. Glutamate Transporters and Mitochondria: Signaling, Co-compartmentalization, Functional Coupling, and Future Directions. Neurochem Res. 2020 Mar;45(3):526-540. Epub 2020 Jan 30. PMID: 32002773. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan JH. Biochemistry of Na,K-ATPase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:511-35. Epub 2001 Nov 9. PMID: 12045105. [CrossRef]

- Rose EM, Koo JC, Antflick JE, Ahmed SM, Angers S, Hampson DR. Glutamate transporter coupling to Na,K-ATPase. J Neurosci. 2009 Jun 24;29(25):8143-55. PMID: 19553454; PMCID: PMC6666056. [CrossRef]

- Genda EN, Jackson JG, Sheldon AL, Locke SF, Greco TM, O’Donnell JC, Spruce LA, Xiao R, Guo W, Putt M, Seeholzer S, Ischiropoulos H, Robinson MB. Co-compartmentalization of the astroglial glutamate transporter, GLT-1, with glycolytic enzymes and mitochondria. J Neurosci. 2011 Dec 14;31(50):18275-88. PMID: 22171032; PMCID: PMC3259858. [CrossRef]

- Smith CD, Carney JM, Starke-Reed PE, Oliver CN, Stadtman ER, Floyd RA, Markesbery WR. Excess brain protein oxidation and enzyme dysfunction in normal aging and in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Dec 1;88(23):10540-3. PMID: 1683703; PMCID: PMC52964. [CrossRef]

- Hensley K, Hall N, Subramaniam R, Cole P, Harris M, Aksenov M, Aksenova M, Gabbita SP, Wu JF, Carney JM et al. (1995) Brain regional correspondence between Alzheimer’s disease histopathology and biomarkers of protein oxidation. J Neurochem 65:2146–2156. [CrossRef]

- Butterfield DA, Poon HF, St Clair D, Keller JN, Pierce WM, Klein JB, Markesbery WR. Redox proteomics identification of oxidatively modified hippocampal proteins in mild cognitive impairment: insights into the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2006 May;22(2):223-32. Epub 2006 Feb 8. PMID: 16466929. [CrossRef]

- Fan S, Xian X, Li L, Yao X, Hu Y, Zhang M, Li W. Ceftriaxone Improves Cognitive Function and Upregulates GLT-1-Related Glutamate-Glutamine Cycle in APP/PS1 Mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(4):1731-1743. PMID: 30452416. [CrossRef]

- Fan S, Li L, Xian X, Liu L, Gao J, Li W. Ceftriaxone regulates glutamate production and vesicular assembly in presynaptic terminals through GLT-1 in APP/PS1 mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2021 Sep;183:107480. Epub 2021 Jun 18. PMID: 34153453. [CrossRef]

- Aksenov MY, Aksenova MV, Carney JM, Butterfield DA. Oxidative modification of glutamine synthetase by amyloid beta peptide. Free Radic Res. 1997 Sep;27(3):267-81. PMID: 9350431. [CrossRef]

- Hensley K, Carney JM, Mattson MP, Aksenova M, Harris M, Wu JF, Floyd RA, Butterfield DA. A model for beta-amyloid aggregation and neurotoxicity based on free radical generation by the peptide: relevance to Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Apr 12;91(8):3270-4. PMID: 8159737; PMCID: PMC43558. [CrossRef]

- Harris ME, Hensley K, Butterfield DA, Leedle RA, Carney JM. Direct evidence of oxidative injury produced by the Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid peptide (1-40) in cultured hippocampal neurons. Exp Neurol. 1995 Feb;131(2):193-202. PMID: 7895820. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Herrup K. Chen J, Herrup K. Glutamine acts as a neuroprotectant against DNA damage, beta-amyloid and H2O2-induced stress. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33177. Epub 2012 Mar 8. PMID: 22413000; PMCID: PMC3297635. [CrossRef]

- Buntup D, Skare O, Solbu TT, Chaudhry FA, Storm-Mathisen J, Thangnipon W. Beta-amyloid 25-35 peptide reduces the expression of glutamine transporter SAT1 in cultured cortical neurons. Neurochem Res. 2008 Feb;33(2):248-56. Epub 2007 Nov 1. PMID: 18058230; PMCID: PMC2226019. [CrossRef]

- Kulijewicz-Nawrot M, Syková E, Chvátal A, Verkhratsky A, Rodríguez JJ. Astrocytes and glutamate homoeostasis in Alzheimer’s disease: a decrease in glutamine synthetase, but not in glutamate transporter-1, in the prefrontal cortex. ASN Neuro. 2013 Oct 7;5(4):273-82. PMID: 24059854; PMCID: PMC3791522. [CrossRef]

- Andersen JV, Skotte NH, Christensen SK, Polli FS, Shabani M, Markussen KH, Haukedal H, Westi EW, Diaz-delCastillo M, Sun RC, et al. Hippocampal disruptions of synaptic and astrocyte metabolism are primary events of early amyloid pathology in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2021 Oct 16;12(11):954. PMID: 34657143; PMCID: PMC8520528. [CrossRef]

- Andersen JV, Christensen SK, Westi EW, Diaz-delCastillo M, Tanila H, Schousboe A, Aldana BI, Waagepetersen HS. Deficient astrocyte metabolism impairs glutamine synthesis and neurotransmitter homeostasis in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2021 Jan;148: 105198. Epub 2020 Nov 24. PMID: 33242587. [CrossRef]

- Masliah E, Alford M, DeTeresa R, Mallory M, Hansen L. Deficient glutamate transport is associated with neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1996 Nov;40(5):759-66. PMID: 8957017. [CrossRef]

- Abdul HM, Sama MA, Furman JL, Mathis DM, Beckett TL, Weidner AM, Patel ES, Baig I, Murphy MP, LeVine H 3rd, Kraner SD, Norris CM. Cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with selective changes in calcineurin/NFAT signaling. J Neurosci. 2009 Oct 14;29(41):12957-69. PMID: 19828810; PMCID: PMC2782445. [CrossRef]

- Jacob CP, Koutsilieri E, Bartl J, Neuen-Jacob E, Arzberger T, Zander N, Ravid R, Roggendorf W, Riederer P, Grünblatt E. Alterations in expression of glutamatergic transporters and receptors in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007 Mar;11(1):97-116. PMID: 17361039. [CrossRef]

- Seiler N. Is ammonia a pathogenetic factor in Alzheimer’s disease? Neurochem Res. 1993 Mar;18(3):235-45. PMID: 8479596. [CrossRef]

- Hamdani EH, Popek M, Frontczak-Baniewicz M, Utheim TP, Albrecht J, Zielińska M, Chaudhry FA. Perturbation of astroglial Slc38 glutamine transporters by NH4+ contributes to neurophysiologic manifestations in acute liver failure. FASEB J. 2021 Jul;35(7):e21588. PMID: 34169573. [CrossRef]

- Gropman A. Brain imaging in urea cycle disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;100 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S20-30. Epub 2010 Feb 13. PMID: 20207564; PMCID: PMC3258295. [CrossRef]

- Maestri NE, Lord C, Glynn M, Bale A, Brusilow SW. The phenotype of ostensibly healthy women who are carriers for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998 Nov;77(6):389-97. PMID: 9854602. [CrossRef]

- Gyato K, Wray J, Huang ZJ, Yudkoff M, Batshaw ML. Metabolic and neuropsychological phenotype in women heterozygous for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 2004 Jan;55(1):80-6. PMID: 14705115. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell JC, Jackson JG, Robinson MB. Transient Oxygen/Glucose Deprivation Causes a Delayed Loss of Mitochondria and Increases Spontaneous Calcium Signaling in Astrocytic Processes. J Neurosci. 2016 Jul 6;36(27):7109-27. PMID: 27383588; PMCID: PMC4938859. [CrossRef]

- Malik AR, Willnow TE. Excitatory Amino Acid Transporters in Physiology and Disorders of the Central Nervous System. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Nov 12;20(22):5671. PMID: 31726793; PMCID: PMC6888459. [CrossRef]

- Mochel F, Duteil S, Marelli C, Jauffret C, Barles A, Holm J, Sweetman L, Benoist JF, Rabier D, Carlier PG, Durr A. Dietary anaplerotic therapy improves peripheral tissue energy metabolism in patients with Huntington’s disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010 Sep;18(9):1057-60. Epub 2010 May 26. PMID: 20512158; PMCID: PMC2987415. [CrossRef]

- Marin-Valencia I, Good LB, Ma Q, Malloy CR, Pascual JM. Heptanoate as a neural fuel: energetic and neurotransmitter precursors in normal and glucose transporter I-deficient (G1D) brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013 Feb;33(2):175-82. Epub 2012 Oct 17. PMID: 23072752; PMCID: PMC3564188. [CrossRef]

- Pascual JM, Liu P, Mao D, Kelly DI, Hernandez A, Sheng M, Good LB, Ma Q, Marin-Valencia I, Zhang X, Park JY, Hynan LS, Stavinoha P, Roe CR, Lu H. Triheptanoin for glucose transporter type I deficiency (G1D): modulation of human ictogenesis, cerebral metabolic rate, and cognitive indices by a food supplement. JAMA Neurol. 2014 Oct;71(10):1255-65. PMID: 25110966; PMCID: PMC4376124. [CrossRef]

- Yuan X, Wang L, Tandon N, Sun H, Tian J, Du H, Pascual JM, Guo L. Triheptanoin Mitigates Brain ATP Depletion and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78(1):425-437. PMID: 33016909; PMCID: PMC8502101. [CrossRef]

- Aso E, Semakova J, Joda L, Semak V, Halbaut L, Calpena A, Escolano C, Perales JC, Ferrer I. Triheptanoin supplementation to ketogenic diet curbs cognitive impairment in APP/PS1 mice used as a model of familial Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2013 Mar;10(3):290-7. PMID: 23131121. [CrossRef]

- Cai Q, Sheng ZH. Mitochondrial transport and docking in axons. Exp Neurol. 2009 Aug;218(2):257-67. Epub 2009 Mar 31. PMID: 19341731; PMCID: PMC2710402. [CrossRef]

- Berth SH, Lloyd TE. Disruption of axonal transport in neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest. 2023 Jun 1;133(11):e168554. PMID: 37259916; PMCID: PMC10232001. [CrossRef]

- Cason SE, Holzbaur ELF. Selective motor activation in organelle transport along axons. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(11):699–714. [CrossRef]

- Prezel E, Elie A, Delaroche J, Stoppin-Mellet V, Bosc C, Serre L, Fourest-Lieuvin A, Andrieux A, Vantard M, Arnal I. Tau can switch microtubule network organizations: from random networks to dynamic and stable bundles. Mol Biol Cell. 2018 Jan 15;29(2):154-165. Epub 2017 Nov 22. PMID: 29167379; PMCID: PMC5909928. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z, Schaedel L, Portran D, Aguilar A, Gaillard J, Marinkovich MP, Théry M, Nachury MV. Microtubules acquire resistance from mechanical breakage through intralumenal acetylation. Science. 2017 Apr 21;356(6335):328-332. PMID: 28428427; PMCID: PMC5457157. [CrossRef]

- Portran D, Schaedel L, Xu Z, Théry M, Nachury MV. Tubulin acetylation protects long-lived microtubules against mechanical ageing. Nat Cell Biol. 2017 Apr;19(4):391-398. Epub 2017 Feb 27. PMID: 28250419; PMCID: PMC5376231. [CrossRef]

- Eshun-Wilson L, Zhang R, Portran D, Nachury MV, Toso DB, Löhr T, Vendruscolo M, Bonomi M, Fraser JS, Nogales E. Effects of α-tubulin acetylation on microtubule structure and stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 May 21;116(21):10366-10371. Epub 2019 May 9. PMID: 31072936; PMCID: PMC6535015. [CrossRef]

- Janke C, Montagnac G. Causes and Consequences of Microtubule Acetylation. Curr Biol. 2017 Dec 4;27(23):R1287-R1292. PMID: 29207274. [CrossRef]

- Saxton WM, Hollenbeck PJ. The axonal transport of mitochondria. J Cell Sci. 2012 May 1;125(Pt 9):2095-104. Epub 2012 May 22. PMID: 22619228; PMCID: PMC3656622 . [CrossRef]

- Kruppa AJ, Buss F. Motor proteins at the mitochondria-cytoskeleton interface. J Cell Sci. 2021 Apr 1;134(7):jcs226084. Epub 2021 Apr 13. PMID: 33912943; PMCID: PMC8077471 . [CrossRef]

- Hirokawa N, Noda Y, Tanaka Y, Niwa S. Kinesin superfamily motor proteins and intracellular transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Oct;10(10):682-96. PMID: 19773780 . [CrossRef]

- Vale RD, Reese TS, Sheetz MP. Identification of a novel force-generating protein, kinesin, involved in microtubule-based motility. Cell. 1985;42: 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Du J, Wei Y, Liu L, Wang Y, Khairova R, Blumenthal R, Tragon T, Hunsberger JG, Machado-Vieira R, Drevets W, et al. A kinesin signaling complex mediates the ability of GSK-3beta to affect mood-associated behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jun 22;107(25):11573-8. Epub 2010 Jun 7. PMID: 20534517; PMCID: PMC2895136 . [CrossRef]

- Banerjee R, Chakraborty P, Yu MC, Gunawardena S. A stop or go switch: glycogen synthase kinase 3β phosphorylation of the kinesin 1 motor domain at Ser314 halts motility without detaching from microtubules. Development. 2021 Dec 15;148(24):dev199866. Epub 2021 Dec 23. PMID: 34940839; PMCID: PMC8722386 . [CrossRef]

- Padzik A, Deshpande P, Hollos P, Franker M, Rannikko EH, Cai D, Prus P, Mågård M, Westerlund N, Verhey KJ,et al. KIF5C S176 Phosphorylation Regulates Microtubule Binding and Transport Efficiency in Mammalian Neurons. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016 Mar 15;10:57. PMID: 27013971; PMCID: PMC4791394 . [CrossRef]

- Brady ST, Morfini GA. Regulation of motor proteins, axonal transport deficits and adult-onset neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;105: 273–282. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz TL. Mitochondrial trafficking in neurons. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013 Jun 1;5(6):a011304. PMID: 23732472; PMCID: PMC3660831 . [CrossRef]

- Fransson S, Ruusala A, Aspenström P. The atypical Rho GTPases Miro-1 and Miro-2 have essential roles in mitochondrial trafficking. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006 Jun 2;344(2):500-10. Epub 2006 Apr 3. PMID: 16630562 . [CrossRef]

- Glater EE, Megeath LJ, Stowers RS, Schwarz TL. Axonal transport of mitochondria requires milton to recruit kinesin heavy chain and is light chain independent. J Cell Biol. 2006 May 22;173(4):545-57. PMID: 16717129; PMCID: PMC2063864. [CrossRef]

- Klosowiak JL, Focia PJ, Chakravarthy S, Landahl EC, Freymann DM, Rice SE. Structural coupling of the EF hand and C-terminal GTPase domains in the mitochondrial protein Miro. EMBO Rep. 2013 Nov;14(11):968-74. Epub 2013 Sep 27. PMID: 24071720; PMCID: PMC3818075 . [CrossRef]

- Macaskill AF, Rinholm JE, Twelvetrees AE, Arancibia-Carcamo IL, Muir J, Fransson A, Aspenstrom P, Attwell D, Kittler JT. Miro1 is a calcium sensor for glutamate receptor-dependent localization of mitochondria at synapses. Neuron. 2009 Feb 26;61(4):541-55. PMID: 19249275; PMCID: PMC2670979 . [CrossRef]

- Cai Q, Zakaria HM, Simone A, Sheng ZH. Spatial parkin translocation and degradation of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy in live cortical neurons. Curr Biol. 2012 Mar 20;22(6):545-52. Epub 2012 Feb 16. PMID: 22342752; PMCID: PMC3313683 . [CrossRef]

- Miller KE, Sheetz MP. Axonal mitochondrial transport and potential are correlated. J Cell Sci. 2004 Jun 1;117(Pt 13):2791-804. Epub 2004 May 18. PMID: 15150321 . [CrossRef]

- Pilling AD, Horiuchi D, Lively CM, Saxton WM. Kinesin-1 and Dynein are the primary motors for fast transport of mitochondria in Drosophila motor axons. Mol Biol Cell. 2006 Apr;17(4):2057-68. Epub 2006 Feb 8. PMID: 16467387; PMCID: PMC1415296 . [CrossRef]

- Kolarova M, García-Sierra F, Bartos A, Ricny J, Ripova D. Structure and pathology of tau protein in Alzheimer disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:731526. [CrossRef]

- Elie A, Prezel E, Guérin C, Denarier E, Ramirez-Rios S, Serre L, Andrieux A, Fourest-Lieuvin A, Blanchoin L, Arnal I. Tau co-organizes dynamic microtubule and actin networks. Sci Rep. 2015 May 5;5: 9964. PMID: 25944224; PMCID: PMC4421749 . [CrossRef]

- Kadavath H, Jaremko M, Jaremko Ł, Biernat J, Mandelkow E, Zweckstetter M. Folding of the tau protein on microtubules. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54: 10347–10351. [CrossRef]

- Watamura N, Foiani MS, Bez S, Bourdenx M, Santambrogio A, Frodsham C, Camporesi E, Brinkmalm G, Zetterberg H, Patel S, et al. In vivo hyperphosphorylation of tau is associated with synaptic loss and behavioral abnormalities in the absence of tau seeds. Nat Neurosci. 2025 Feb;28(2):293-307. Epub 2024 Dec 24. PMID: 39719507; PMCID: PMC11802456. [CrossRef]

- Roveta F, Bonino L, Piella EM, Rainero I, Rubino E. Neuroinflammatory Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Nov 6;25(22):11941. PMID: 39596011; PMCID: PMC11593837. [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi M, Yandiev S, Meyer-Dilhet G, Ellouze S, Kerkhofs M, Dos Reis R, Garcia A, Blondet C, Amar A, Kneppers A, et al. The AMPK-related kinase NUAK1 controls cortical axons branching by locally modulating mitochondrial metabolic functions. Nat Commun. 2024 Mar 21;15(1):2487. PMID: 38514619; PMCID: PMC10958033 . [CrossRef]

- Li S, Xiong G-J, Huang N, Sheng Z-H. The cross-talk of energy sensing and mitochondrial anchoring sustains synaptic efficacy by maintaining presynaptic metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2020;2: 1077–1095. [CrossRef]

- DeTure MA, Dickson DW. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2019 Aug 2;14(1):32. PMID: 31375134; PMCID: PMC6679484 . [CrossRef]

- Rico T, Gilles M, Chauderlier A, Comptdaer T, Magnez R, Chwastyniak M, Drobecq H, Pinet F, Thuru X, Buée L, Galas MC, Lefebvre B. Tau Stabilizes Chromatin Compaction. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Oct 14;9: 740550. PMID: 34722523; PMCID: PMC8551707 . [CrossRef]

- Magrin C, Bellafante M, Sola M, Piovesana E, Bolis M, Cascione L, Napoli S, Rinaldi A, Papin S, Paganetti P. Tau protein modulates an epigenetic mechanism of cellular senescence in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023 Oct 3;11:1232963. PMID: 37842084; PMCID: PMC10569482 . [CrossRef]

- Stokin GB, Lillo C, Falzone TL, Brusch RG, Rockenstein E, Mount SL, Raman R, Davies P, Masliah E, Williams DS, Goldstein LS. Axonopathy and transport deficits early in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2005 Feb 25;307(5713):1282-8. PMID: 15731448 . [CrossRef]

- Lauretti E, Dincer O, Praticò D. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2020 May;1867(5):118664. Epub 2020 Jan 30. PMID: 32006534; PMCID: PMC7047718 . [CrossRef]

- Lin CW, Chang LC, Ma T, Oh H, French B, Puralewski R, Mathews F, Fang Y, Lewis DA, Kennedy JL, et al. Older molecular brain age in severe mental illness. Mol Psychiatry. 2021 Jul;26(7):3646-3656. Epub 2020 Jul 6. PMID: 32632206; PMCID: PMC7785531 . [CrossRef]

- Vance JE, Hayashi H, Karten B. Cholesterol homeostasis in neurons and glial cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005 Apr;16(2):193-212. PMID: 15797830 . [CrossRef]

- Sych T, Gurdap CO, Wedemann L, Sezgin E. How Does Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in Model Membranes Reflect Cell Membrane Heterogeneity? Membranes (Basel). 2021 Apr 28;11(5):323. PMID: 33925240; PMCID: PMC8146956 . [CrossRef]

- Brown D A, London E. Structure and origin of ordered lipid domains in biological membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 1998, 164 (2), 103–114. [CrossRef]

- London E. How principles of domain formation in model membranes may explain ambiguities concerning lipid raft formation in cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 2005, 1746 (3), 203–220. [CrossRef]

- Shaw T R, Ghosh S, Veatch SL Critical Phenomena in Plasma Membrane Organization and Function. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2021, 72, 51–72. [CrossRef]

- Levi M, Gratton E. Visualizing the regulation of SLC34 proteins at the apical membrane. Pflugers Arch. 2019 Apr;471(4):533-542. Epub 2019 Jan 6. PMID: 30613865; PMCID: PMC6436987 . [CrossRef]

- Sebastiao AM, Colino-Oliveira M, Assaife-Lopes N, Dias RB, Ribeiro JA. Lipid rafts, synaptic transmission and plasticity: impact in age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64: 97–107. [CrossRef]

- Sezgin E, Levental I, Mayor S, Eggeling C. The mystery of membrane organization: composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:361–74. [CrossRef]

- Simons K, Toomre D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1: 31–39. [CrossRef]

- Helms JB, Zurzolo C. Lipids as targeting signals: lipid rafts and intracellular trafficking. Traffic. 2004;5: 247–254. [CrossRef]

- Korbecki J, Bosiacki M, Pilarczyk M, Gąssowska-Dobrowolska M, Jarmużek P, Szućko-Kociuba I, Kulik-Sajewicz J, Chlubek D, Baranowska-Bosiacka I. Phospholipid Acyltransferases: Characterization and Involvement of the Enzymes in Metabolic and Cancer Diseases. Cancers (Basel). 2024 May 31;16(11):2115. PMID: 38893234; PMCID: PMC11171337 . [CrossRef]

- Agarwal AK. Lysophospholipid acyltransferases: 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferases. From discovery to disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2012;23: 290–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Maeda Y, Tashima Y, Houjou T, Fujita M, Yoko-o T, Jigami Y, Taguchi R, Kinoshita T. Fatty acid remodeling of GPI-anchored proteins is required for their raft association. Mol Biol Cell. 2007 Apr;18(4):1497-506. Epub 2007 Feb 21. PMID: 17314402 . [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita T. Biosynthesis and biology of mammalian GPI-anchored proteins. Open Biol. 2020 Mar;10(3):190290. Epub 2020 Mar 11. PMID: 32156170; PMCID: PMC7125958 . [CrossRef]

- Hishikawa D, Hashidate T, Shimizu T, Shindou H. Diversity and function of membrane glycerophospholipids generated by the remodeling pathway in mammalian cells. J Lipid Res. 2014 May;55(5):799-807. Epub 2014 Mar 19. Erratum in: J Lipid Res. 2014 Nov;55(11):2444. PMID: 24646950; PMCID: PMC3995458 . [CrossRef]

- Baker MJ, Crameri JJ, Thorburn DR, Frazier AE, Stojanovski D. Mitochondrial biology and dysfunction in secondary mitochondrial disease. Open Biol. 2022 Dec;12(12):220274. Epub 2022 Dec 7. PMID: 36475414; PMCID: PMC9727669 . [CrossRef]

- Ikon N, Ryan RO. Cardiolipin and mitochondrial cristae organization. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2017 Jun;1859(6):1156-1163. Epub 2017 Mar 20. PMID: 28336315; PMCID: PMC5426559 . [CrossRef]

- Gilkerson RW, Selker JM, Capaldi RA. The cristal membrane of mitochondria is the principal site of oxidative phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2003 Jul 10;546(2-3):355-8. PMID: 12832068 . [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Mileykovskaya E, Dowhan W. Cardiolipin is essential for organization of complexes III and IV into a supercomplex in intact yeast mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005 Aug 19;280(33):29403-8. Epub 2005 Jun 22. PMID: 15972817; PMCID: PMC4113954 . [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer K, Gohil V, Stuart RA, Hunte C, Brandt U, Greenberg ML, Schägger H. Cardiolipin stabilizes respiratory chain supercomplexes. J Biol Chem. 2003 Dec 26;278(52):52873-80. Epub 2003 Oct 15. PMID: 14561769 . [CrossRef]

- Kowaltowski AJ, de Souza-Pinto NC, Castilho RF, Vercesi AE. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009 Aug 15;47(4):333-43. Epub 2009 May 8. PMID: 19427899 . [CrossRef]

- Su LJ, Zhang JH, Gomez H, Murugan R, Hong X, Xu D, Jiang F, Peng ZY. Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Lipid Peroxidation in Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019 Oct 13;2019: 5080843. PMID: 31737171; PMCID: PMC6815535 . [CrossRef]

- Braughler JM, Duncan LA, Chase R. The involvement of iron in lipid peroxidation. Importance of ferric to ferrous ratios in initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261 (22), 10282–10289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Koppenol WH, Hider RH. Iron and redox cycling. Do’s and don’ts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019 Mar;133: 3-10. Epub 2018 Sep 17. PMID: 30236787 . [CrossRef]

- Slater TF. Overview of methods used for detecting lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105: 283-93. PMID: 6427 . [CrossRef]

- Akagi S, Kono N, Ariyama H, Shindou H, Shimizu T, Arai H. Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 protects against cytotoxicity induced by polyunsaturated fatty acids. FASEB J. 2016;30: 2027–2039. [CrossRef]

- Rybnikova E, Damdimopoulos AE, Gustafsson JA, Spyrou G, Pelto-Huikko M. Expression of novel antioxidant thioredoxin-2 in the rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2000 May;12(5):1669-78. PMID: 10792444 . [CrossRef]

- Phadnis VV, Snider J, Varadharajan V, Ramachandiran I, Deik AA, Lai ZW, Kunchok T, Eaton EN, Sebastiany C, Lyakisheva A, et al. MMD collaborates with ACSL4 and MBOAT7 to promote polyunsaturated phosphatidylinositol remodeling and susceptibility to ferroptosis. Cell Rep. 2023 Sep 26;42(9):113023. Epub 2023 Sep 8. PMID: 37691145; PMCID: PMC10591818 . [CrossRef]

- Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM,Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012; 149, 1060–1072. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Stockwell BR, and Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. 2021; Cell Biol. 22, 266–282. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Han X, Lan X, Gao Y, Wan J, Durham F, Cheng T, Yang J, Wang Z, Jiang C, et al. Inhibition of neuronal ferroptosis protects hemorrhagic brain. JCI Insight 2017; 2, e90777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMe. [CrossRef]

- Thinakaran G, Koo EH. Amyloid precursor protein trafficking, processing, and function. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283: 29615–29619. [CrossRef]

- Lazarov O, Lee M, Peterson DA, Sisodia SS. Evidence that synaptically released beta-amyloid accumulates as extracellular deposits in the hippocampus of transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22: 9785–9793. [CrossRef]

- Koo EH, Sisodia SS, Archer DR, Martin LJ, Weidemann A, Beyreuther K, Fischer P, Masters CL, Price DL. Precursor of amyloid protein in Alzheimer disease undergoes fast anterograde axonal transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1561–1565. [CrossRef]

- Capone R, Tiwari A, Hadziselimovic A, Peskova Y, Hutchison JM, Sanders CR, Kenworthy AK. The C99 domain of the amyloid precursor protein resides in the disordered membrane phase. J Biol Chem. 2021 Jan-Jun;296: 100652. Epub 2021 Apr 9. PMID: 33839158; PMCID: PMC8113881 . [CrossRef]

- Vassar R. BACE1: the beta-secretase enzyme in Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;23 :105–114. [CrossRef]

- Allinson TM, Parkin ET, Turner AJ, Hooper NM. ADAMs family members as amyloid precursor protein alpha-secretases. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74 :342–352. [CrossRef]

- Iwatsubo T. The g-secretase complex: machinery for intramembrane proteolysis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:379–383. [CrossRef]

- Abraham CB, Xu L, Pantelopulos GA, Straub JE. Characterizing the transmembrane domains of ADAM10 and BACE1 and the impact of membrane composition. Biophys J. 2023 Oct 3;122(19):3999-4010. Epub 2023 Sep 1. PMID: 37658602; PMCID: PMC10560698. [CrossRef]

- Runz H, Rietdorf J, Tomic I, de Bernard M, Beyreuther K, Pepperkok R, Hartmann T. Inhibition of intracellular cholesterol transport alters presenilin localization and amyloid precursor protein processing in neuronal cells. J Neurosci. 2002; 22:1679–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Yao J, Kim TW, Tall AR. Expression of liver X receptor target genes decreases cellular amyloid beta peptide secretion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278: 27688–27694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Hemming ML, Elias JE, Gygi SP, Selkoe DJ. Identification of beta-secretase (BACE1) substrates using quantitative proteomics. PLoS One. 2009;4: e8477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Prasad MR, Lovell MA, Yatin M, Dhillon H, Markesbery WR. Regional membrane phospholipid alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res. 1998 Jan;23(1):81-8. PMID: 9482271. [CrossRef]

- Fabelo N, Martín V, Marín R, Moreno D, Ferrer I, Díaz M. Altered lipid composition in cortical lipid rafts occurs at early stages of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and facilitates APP/BACE1 interactions. Neurobiol Aging. 2014 Aug;35(8):1801-12. Epub 2014 Feb 11. PMID: 24613671. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson DT, Lemere CA, Selkoe DJ, Clemens JA. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) immunoreactivity is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol Dis. 1996 Feb;3(1):51-63. PMID: 9173912 . [CrossRef]

- Rubinski A, Tosun D, Franzmeier N, Neitzel J, Frontzkowski L, Weiner M, et al. Lower Cerebral Perfusion Is Associated with Tau-PET in the Entorhinal Cortex across the Alzheimer’s Continuum. Neurobiol Aging 2021; 102:111–8. [CrossRef]

- Chao LL, Buckley ST, Kornak J, Schuff N, Madison C, Yaffe K, Miller BL, Kramer JH, Weiner MW. ASL perfusion MRI predicts cognitive decline and conversion from MCI to dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010 Jan-Mar;24(1):19-27. PMID: 20220321; PMCID: PMC2865220 . [CrossRef]

- Love S, Miners JS. Cerebrovascular disease in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2016 May;131(5):645-58. Epub 2015 Dec 28. PMID: 26711459; PMCID: PMC4835514 . [CrossRef]

- Mattsson N, Tosun D, Insel PS, Simonson A, Jack CR Jr., Beckett LA, et al. Association of brain amyloid-β with cerebral perfusion and structure in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Brain: a journal of neurology 2014; 137(Pt 5): 1550–61. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, Nation DA, Schneider LS, Chui HC, Harrington MG, Pa J, Law M, Wang DJJ, et al. Vascular dysfunction-The disregarded partner of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019 Jan;15(1):158-167. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.222. Erratum in: Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Mar;18(3):522. PMID: 30642436; PMCID: PMC6338083. [CrossRef]

- de la Torre JC. Alzheimer disease as a vascular disorder: nosological evidence. Stroke. 2002 Apr;33(4):1152-62. PMID: 11935076. [CrossRef]

- Kalaria RN. Small vessel disease and Alzheimer’s dementia: pathological considerations. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002; 13: 48–52. [CrossRef]

- Iadecola C, Gorelick PB. Converging pathologic mechanisms in vascular and neurodegenerative dementia. Stroke. 2003; 34: 335–337. [CrossRef]

- Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Foster NL, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Associations between cognitive, functional, and FDG-PET measures of decline in AD and MCI. Neurobiol Aging. 2011 Jul;32(7):1207-18. Epub 2009 Aug 5. PMID: 19660834; PMCID: PMC2891865 . [CrossRef]

- Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Reiman EM, Foster NL, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Jack CR Jr, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Comparing predictors of conversion and decline in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2010 Jul 20;75(3):230-8. Epub 2010 Jun 30. PMID: 20592257; PMCID: PMC2906178 . [CrossRef]

- Ossenkoppele R, van der Flier WM, Zwan MD, Adriaanse SF, Boellaard R, Windhorst AD, Barkhof F, Lammertsma AA, Scheltens P, van Berckel BN. Differential effect of APOE genotype on amyloid load and glucose metabolism in AD dementia. Neurology. 2013 Jan 22;80(4):359-65. Epub 2012 Dec 19. PMID: 23255822 . [CrossRef]

- Protas HD, Chen K, Langbaum JB, Fleisher AS, Alexander GE, Lee W, Bandy D, de Leon MJ, Mosconi L, Buckley S, et al. Posterior cingulate glucose metabolism, hippocampal glucose metabolism, and hippocampal volume in cognitively normal, late-middle-aged persons at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013 Mar 1;70(3):320-5. PMID: 23599929; PMCID: PMC3745014 . [CrossRef]

- Spallazzi M, Dobisch L, Becke A, Berron D, Stucht D, Oeltze-Jafra S, Caffarra P, Speck O, Düzel E. Hippocampal vascularization patterns: A high-resolution 7 Tesla time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography study. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;21: 101609. Epub 2018 Nov 19. PMID: 30581106; PMCID: PMC6413539 . [CrossRef]

- Shaw K, Bell L, Boyd K, Grijseels DM, Clarke D, Bonnar O, Crombag HS, Hall CN. Neurovascular coupling and oxygenation are decreased in hippocampus compared to neocortex because of microvascular differences. Nat Commun. 2021 May 27;12(1):3190. Erratum in: Nat Commun. 2021 Jul 19;12(1):4497. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24833-y. PMID: 34045465; PMCID: PMC8160329 . [CrossRef]

- Ando S, Tsukamoto H, Stacey BS, Washio T, Owens TS, Calverley TA, Fall L, Marley CJ, Iannetelli A, Hashimoto T, Ogoh S, Bailey DM. Acute hypoxia impairs posterior cerebral bioenergetics and memory in man. Exp Physiol. 2023 Dec;108(12):1516-1530. Epub 2023 Oct 29. PMID: 37898979; PMCID: PMC10988469 . [CrossRef]

- Geraghty JR, Lara-Angulo MN, Spegar M, Reeh J, Testai FD. Severe cognitive impairment in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Predictors and relationship to functional outcome. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020 Sep;29(9):105027. Epub 2020 Jun 20. PMID: 32807442; PMCID: PMC7438604 . [CrossRef]

- Pickard JD, Walker V, Perry S, Smythe PJ, Eastwood S, Hunt R. Arterial eicosanoid production following chronic exposure to a periarterial haematoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984 Jul;47(7):661-7. PMID: 6589362; PMCID: PMC1027891 . [CrossRef]

- Erdem A, Yaşargil G, Roth P. Microsurgical anatomy of the hippocampal arteries. J Neurosurg. 1993 Aug;79(2):256-65. PMID: 8331410 . [CrossRef]

- den Abeelen AS, Lagro J, van Beek AH, Claassen JA. Impaired cerebral autoregulation and vasomotor reactivity in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014 Jan;11(1):11-7. PMID: 24251392 . [CrossRef]

- Pires PW, Dams Ramos CM, Matin N, Dorrance AM. The effects of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013 Jun 15;304(12):H1598-614. Epub 2013 Apr 12. PMID: 23585139; PMCID: PMC4280158 . [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Papadopoulos P, Hamel E. Endothelial TRPV4 channels mediate dilation of cerebral arteries: impairment and recovery in cerebrovascular pathologies related to Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2013 Oct;170(3):661-70. PMID: 23889563; PMCID: PMC3792003 . [CrossRef]

- Roher AE, Esh C, Kokjohn TA, Kalback W, Luehrs DC, Seward JD, Sue LI, Beach TG. Circle of Willis atherosclerosis is a risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003; 23: 2055–2062. [CrossRef]

- Roher AE, Esh C, Rahman A, Kokjohn TA, Beach TG. Atherosclerosis of cerebr arteries in Alzheimer disease. Stroke. 2004 Nov;35(11 Suppl 1):2623-7. Epub 2004 Sep 16. PMID: 15375298 . [CrossRef]

- Maass A, Düzel S, Goerke M, Becke A, Sobieray U, Neumann K, Lövden M, Lindenberger U, Bäckman L, Braun-Dullaeus R, et al. Vascular hippocampal plasticity after aerobic exercise in older adults. Mol Psychiatry. 2015 May;20(5):585-93. Epub 2014 Oct 14. PMID: 25311366 . [CrossRef]

- Maksimovich IV. Differences in cerebral angioarchitectonics in Alzheimer’s Disease in comparison with other neurodegenerative and ischemic lesions. World Journal of Neuroscience 2018; 8: 454-469. [CrossRef]

- Lawley JS, Macdonald JH, Oliver SJ, Mullins PG. Unexpected reductions in regional cerebral perfusion during prolonged hypoxia. J Physiol. 2017 Feb 1;595(3):935-947. Epub 2016 Sep 24. PMID: 27506309; PMCID: PMC5285718 . [CrossRef]

- Mottahedin A, Prag HA, Dannhorn A, Mair R, Schmidt C, Yang M, Sorby-Adams A, Lee JJ, Burger N, Kulaveerasingam D, et al. Targeting succinate metabolism to decrease brain injury upon mechanical thrombectomy treatment of ischemic stroke. Redox Biol. 2023 Feb;59: 102600. Epub 2023 Jan 2. PMID: 36630820; PMCID: PMC9841348 . [CrossRef]

- Beason-Held LL, Moghekar A, Zonderman AB, Kraut MA, Resnick SM. Longitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow in the older hypertensive brain. Stroke. 2007 Jun;38(6):1766-73. Epub 2007 May 17. PMID: 17510458 . [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz MA, Kiwak KJ, Hekimian K, Levine L. Synthesis of compounds with properties of leukotrienes C4 and D4 in gerbil brains after ischemia and reperfusion. Science.1984;224(4651):886-889. [CrossRef]

- Hota SK, Barhwal K, Singh SB, Ilavazhagan G. Differential temporal response of hippocampus, cortex and cerebellum to hypobaric hypoxia: a biochemical approach. Neurochem Int. 2007 Nov-Dec;51(6-7):384-90. Epub 2007 Apr 8. PMID: 17531352 . [CrossRef]

- Shukitt-Hale B, Kadar T, Marlowe BE, Stillman MJ, Galli RL, Levy A, Devine JA, Lieberman HR. Morphological alterations in the hippocampus following hypobaric hypoxia. Hum Exp Toxicol.1996 Apr;15(4):312-9. PMID: 8845221 . [CrossRef]

- Maiti P, Singh SB, Sharma AK, Muthuraju S, Banerjee PK, Ilavazhagan G. Hypobaric hypoxia induces oxidative stress in rat brain. Neurochem Int. 2006 Dec;49(8):709-16. Epub 2006 Sep 5. PMID: 1691184. [CrossRef]

- Tahir MS, Almezgagi M, Zhang Y, Zhonglei D, Qinfang Z, Ali M, Shouket Z, Zhang W. Experimental brain injury induced by acute hypobaric hypoxia stimulates changes in mRNA expression and stress marker status. International Journal of Research and Review 2021;8 (10): 242-247. [CrossRef]

- Ji X, Ferreira T, Friedman B, Liu R, Liechty H, Bas E, Chandrashekar J, Kleinfeld D. Brain microvasculature has a common topology with local differences in geometry that match metabolic load. Neuron. 2021 Apr 7;109(7):1168-1187.e13. Epub 2021 Mar 2. PMID: 33657412; PMCID: PMC8525211 . [CrossRef]

- Perosa V, Priester A, Ziegler G, Cardenas-Blanco A, Dobisch L, Spallazzi M, Assmann A, Maass A, Speck O, Oltmer J, et al. Hippocampal vascular reserve associated with cognitive performance and hippocampal volume. Brain. 2020;143: 622–634. [CrossRef]