Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

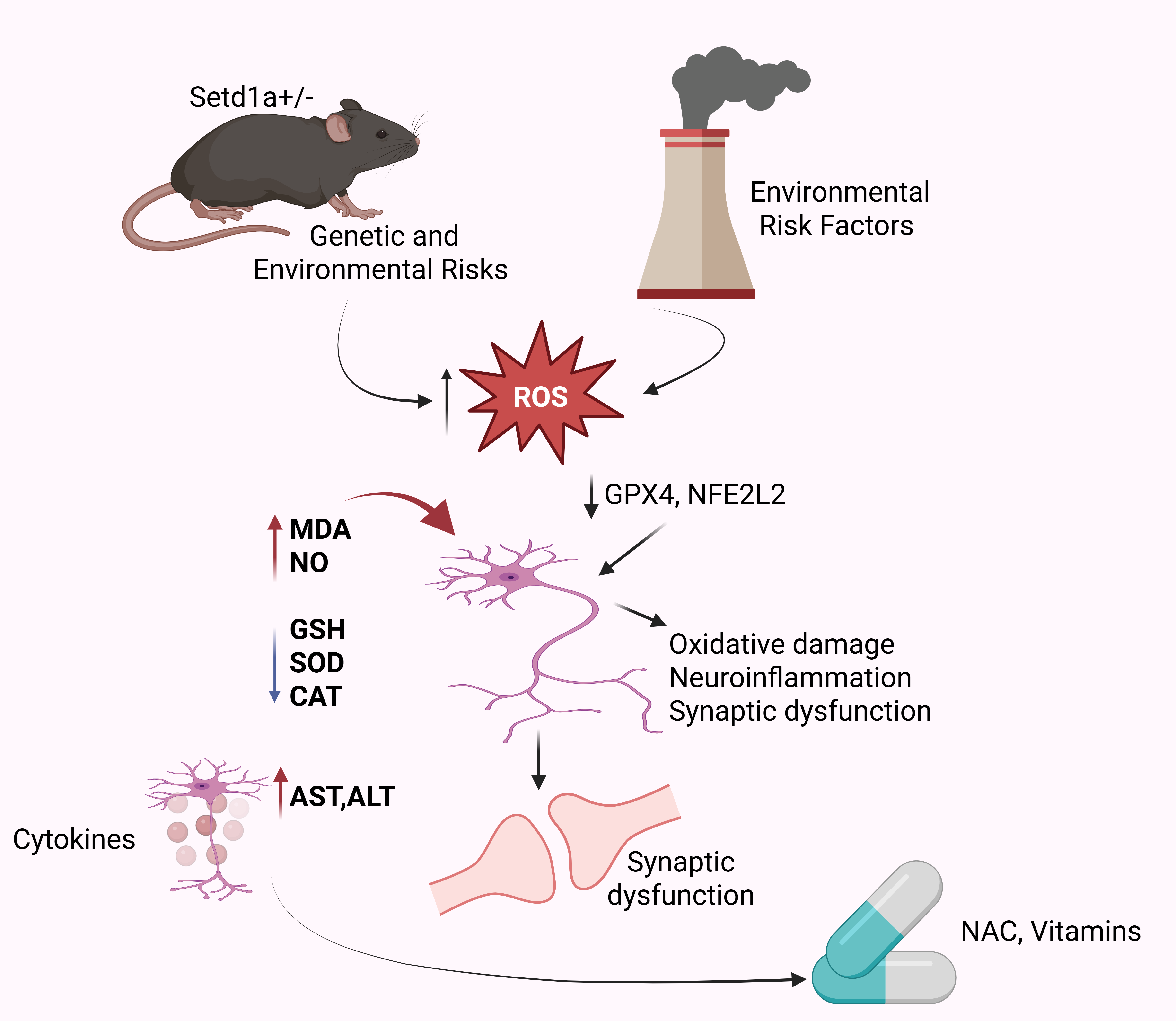

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Clinical Diagnosis and Blood Sample Collection

2.4. Determination of Oxidative Stress Markers.

2.4.1. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) Data Analysis

2.4.2. Lipid Peroxidation (MDA) Assay

2.4.3. Advanced Protein Oxidation Product (APOP) Assay

2.4.4. Nitric Oxide (NO) Assay

2.4.5. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity

2.4.6. Catalase (CAT) Activity

2.4.7. Glutathione (GSH) Assay

2.5. Liver Function Tests (LFT)

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Result

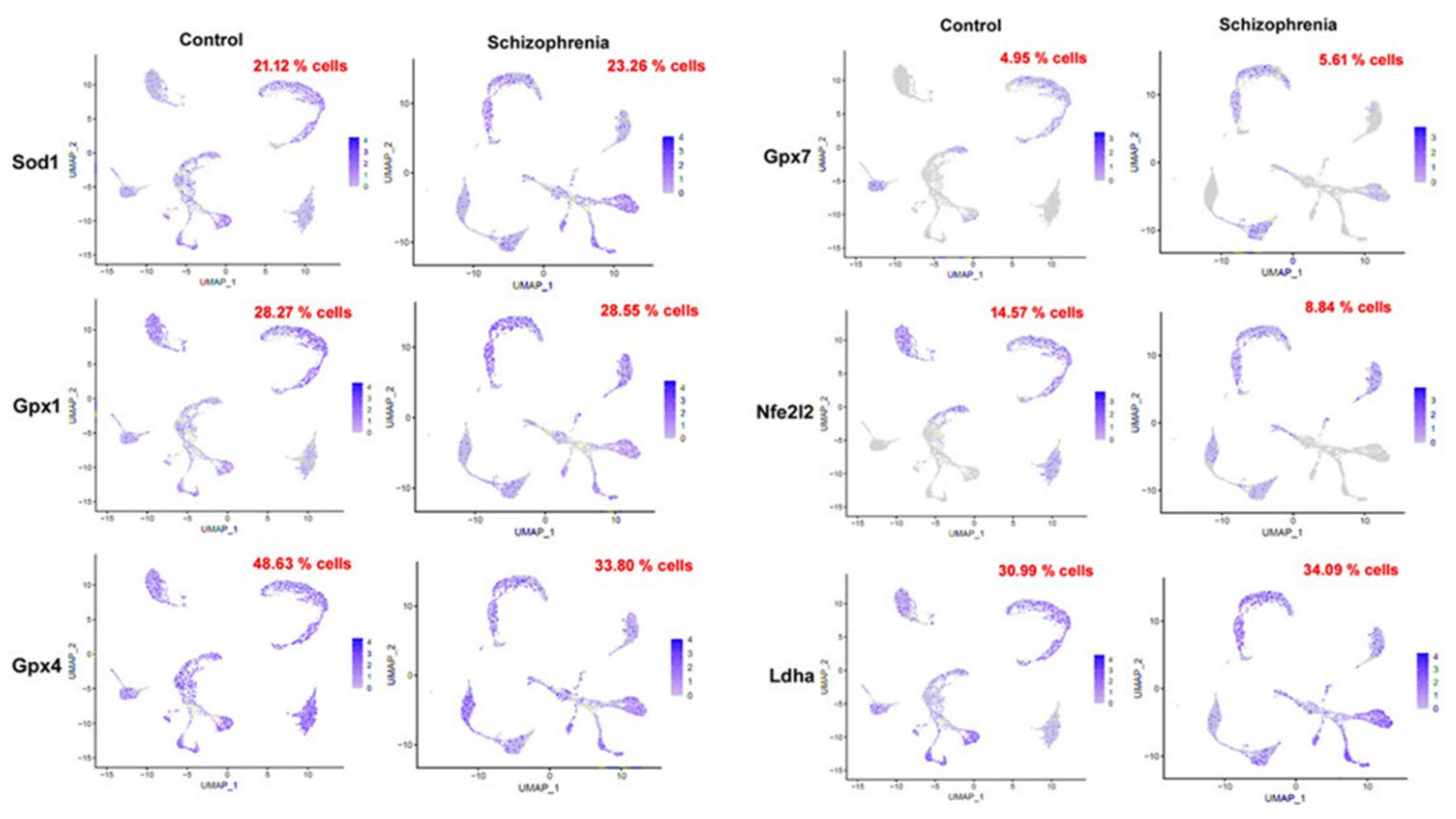

3.1. High Expression of the Oxidative Stress Biomarker( in Schizophrenia Induced Mouse Single-Cell Data

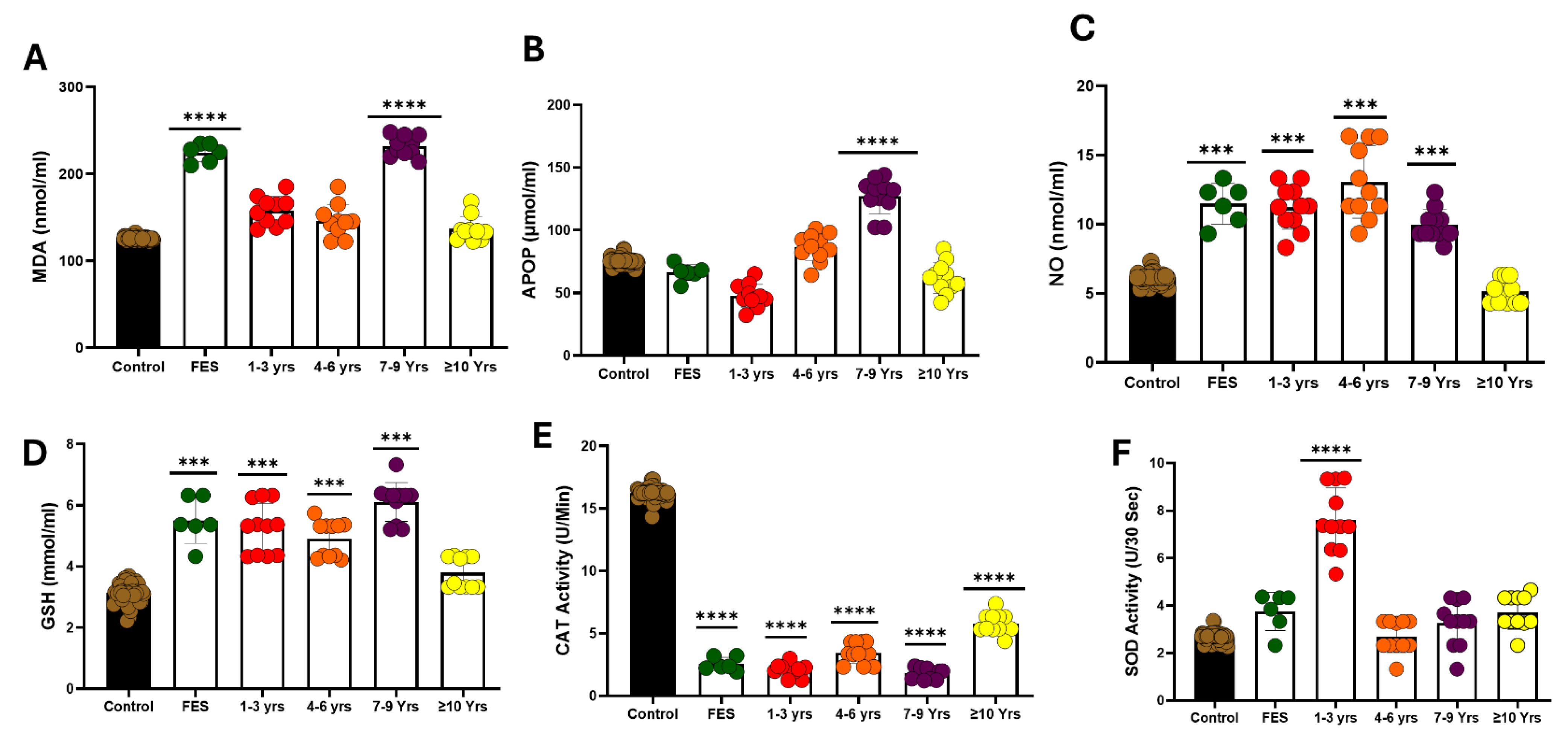

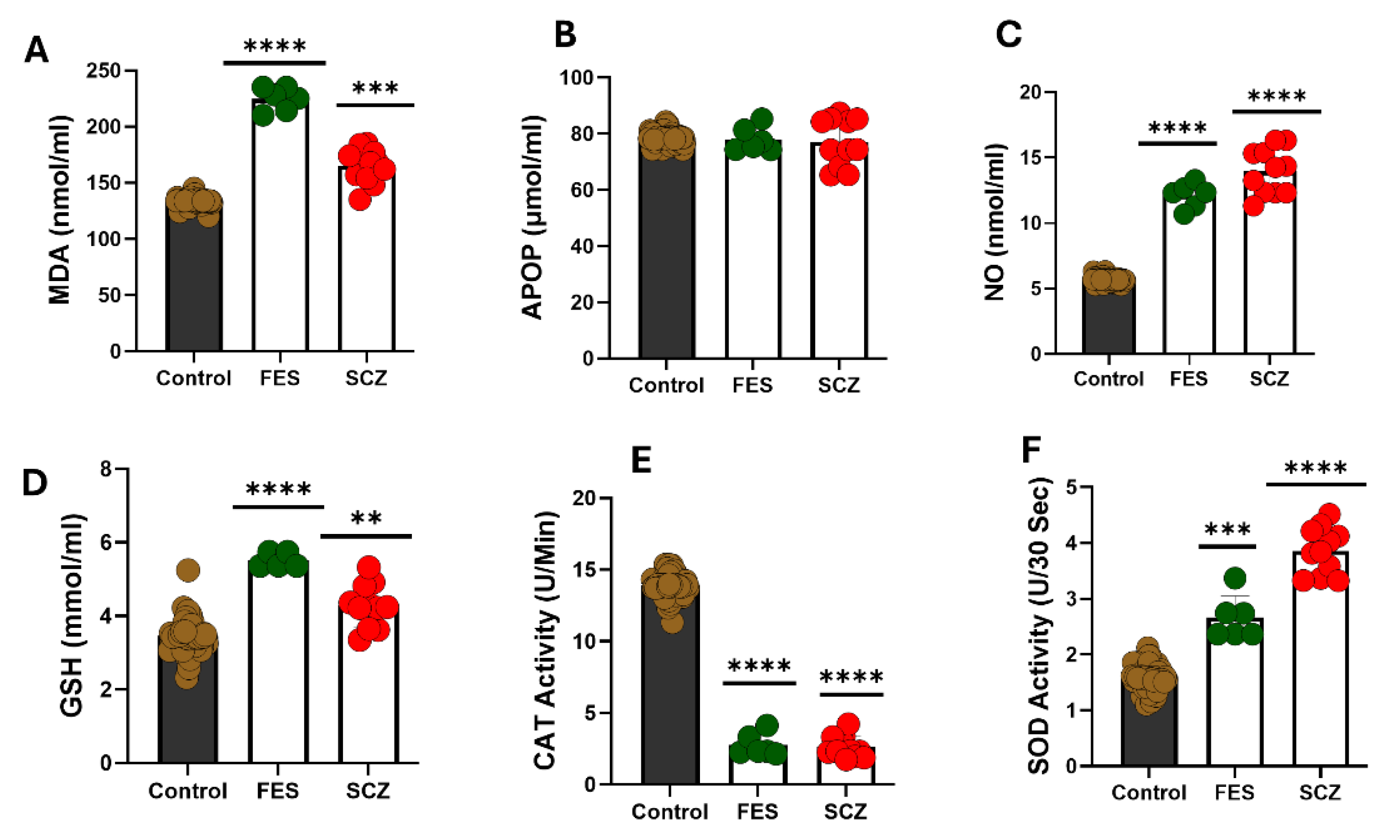

3.2. Serum Oxidative Stress

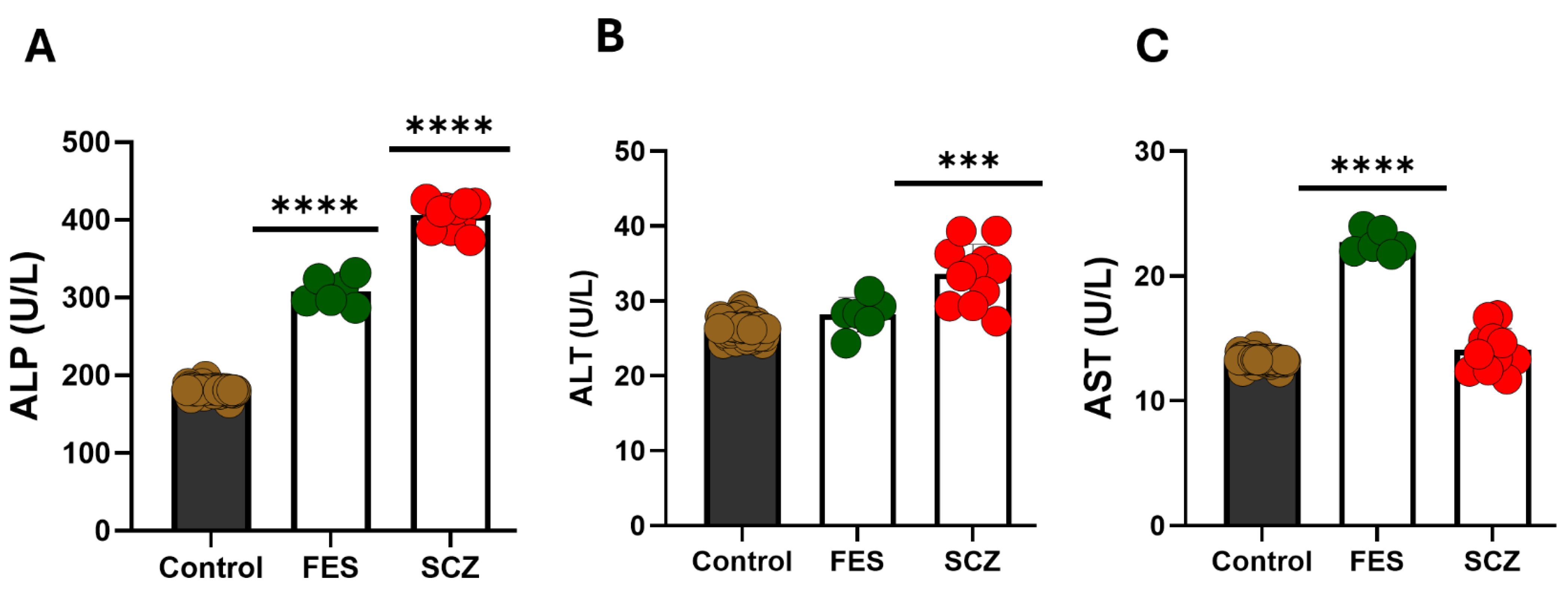

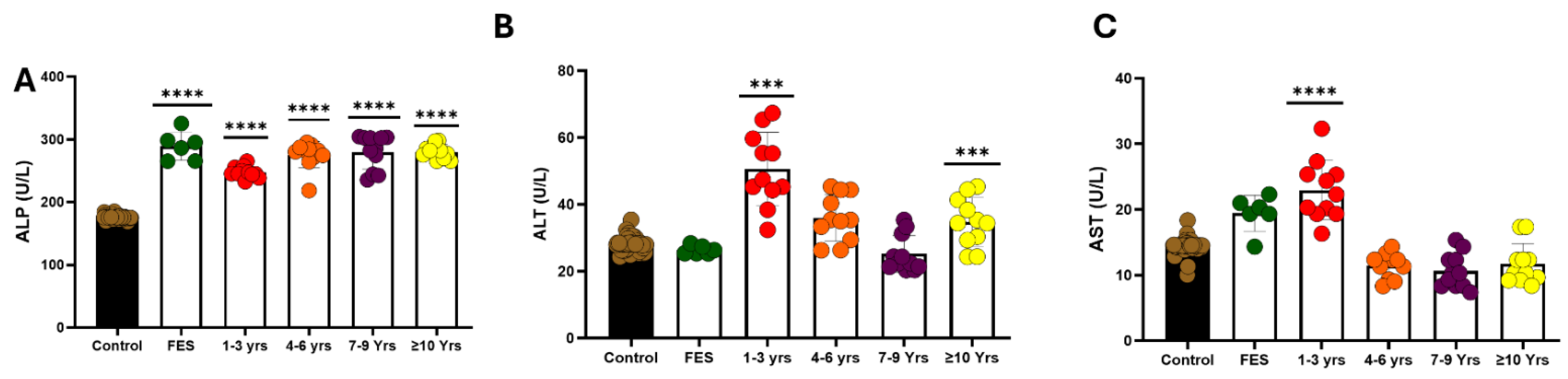

3.3. Liver Function Test

3.4. Serum Oxidative Stress in Various Lengths of Disease

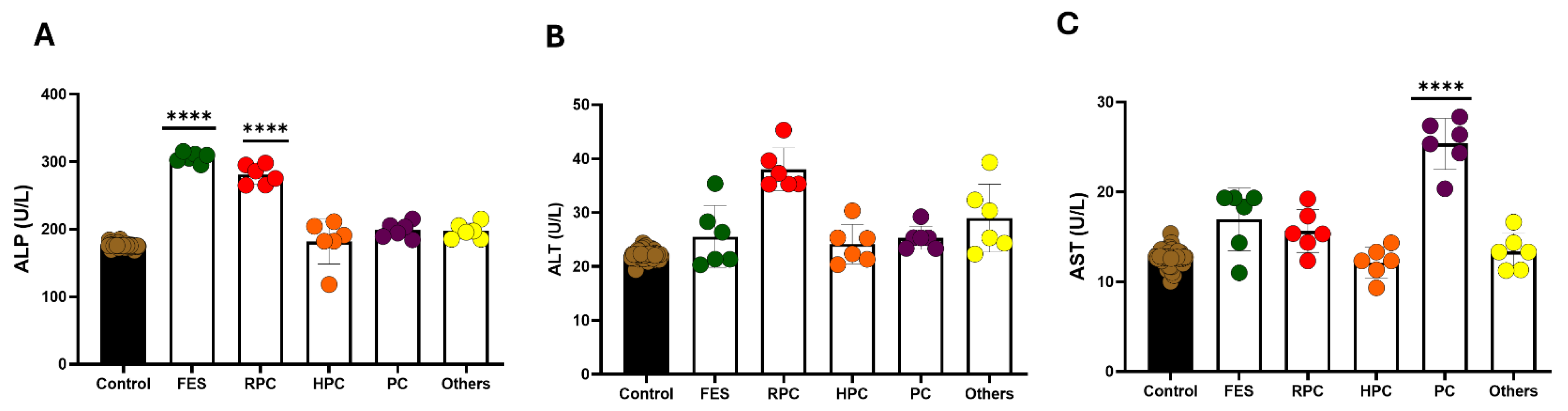

3.5. Liver Function Test in Various Lengths of Disease

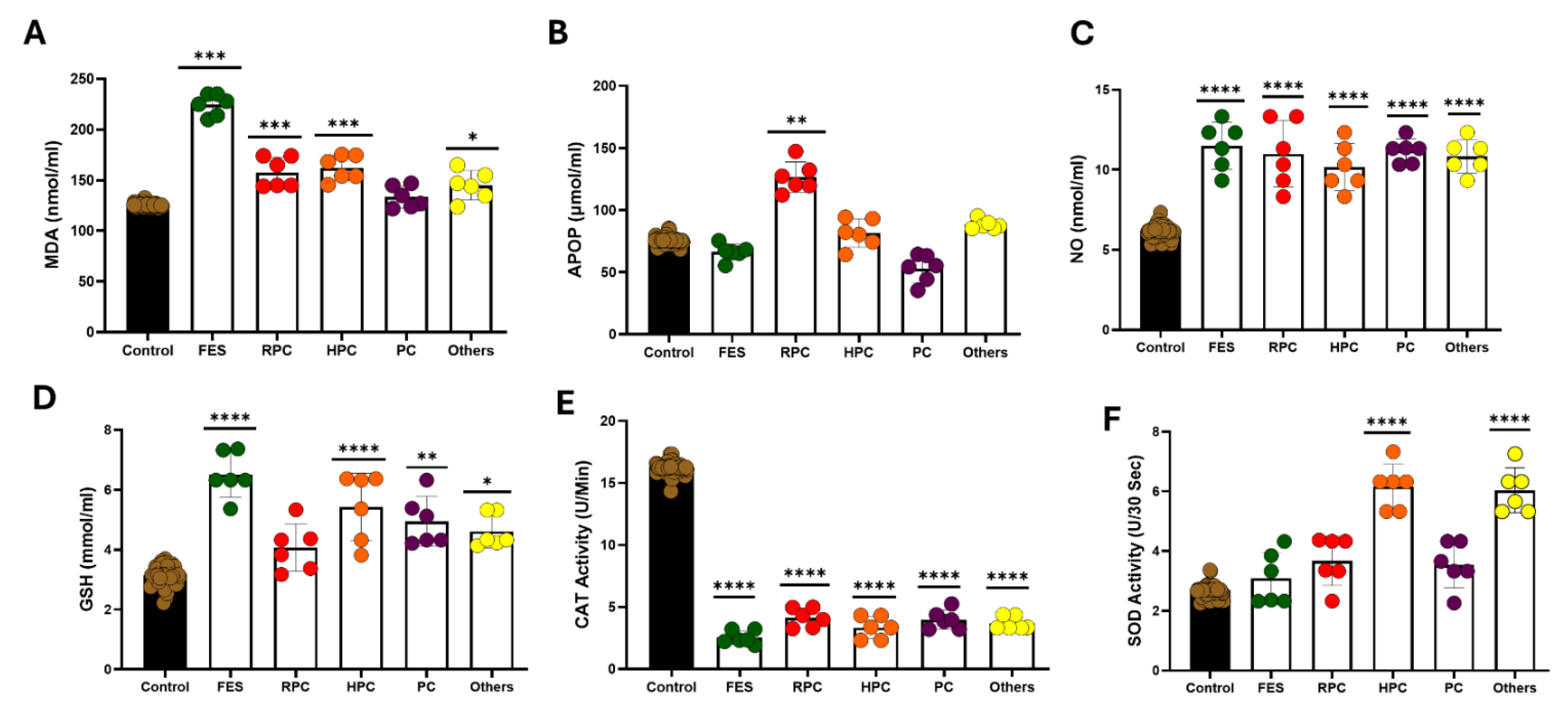

3.6. Effect of Treatment on Oxidative Stress Markers in the Serum

3.7. Effect of Treatment on Liver Function Test

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Present Study

- Other parameters that influence oxidative stress and antioxidant enzymes level were not included in the study, like dietary habits, smoking habits, lifestyles, etc.

- All the selected cases were acute, which might influence the oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme levels. Comparisons needed to be made with chronic cases

- Measurement of oxidative stress and antioxidant enzymes level was done before the treatment was started; no subsequent measurement was done to verify the changes in these parameters with the treatment or improvement in the disease process.

- The deficit of glutathione may result in impairment of the myelination process in the brain’s white matter in schizophrenia [47].

- The result of the present study showed an alteration of liver function parameters, including AST, ALT, and ALP. The findings of the present study are consistent with the past [68].

- We acknowledge that lifestyle-related variables such as smoking, diet, BMI, and antipsychotic medication use were not controlled in this study and may act as confounders. Future studies should incorporate these factors to better isolate disease-related oxidative and hepatic changes.

List of Abbreviations

Duration of Disease

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Schizophrenia - National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Luvsannyam, E.; Jain, M.S.; Pormento, M.K.L.; Siddiqui, H.; Balagtas, A.R.A.; Emuze, B.O.; Poprawski, T. Neurobiology of Schizophrenia: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 14, e23959. [CrossRef]

- Strassnig, M.; Signorile, J.; Gonzalez, C.; Harvey, P.D. Physical Performance and Disability in Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Cogn 2014, 1, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, A.; Jahan, S.S.; Jakanta Faika, M.; Islam, T.; Ferdous, N.-E.; Nessa, A. Bangladeshi parents’ knowledge and awareness about cervical cancer and willingness to vaccinate female family members against human papilloma virus: a cross sectional study. 2023.

- Administration, S.A. and M.H.S. Table 3.22, DSM-IV to DSM-5 Schizophrenia Comparison. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519704/table/ch3.t22/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Rahman, T.; Lauriello, J. Schizophrenia: An Overview. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 2016, 14, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exploring Health Informatics in the Battle against Drug Addiction: Digital Solutions for the Rising Concern. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4426/14/6/556 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Fatemi, S.H.; Folsom, T.D. The Neurodevelopmental Hypothesis of Schizophrenia, Revisited. Schizophr Bull 2009, 35, 528–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Schizophrenia: Current Evidence, Methodological Advances, Limitations and Future Directions - PMC. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10786022/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- MacDonald, H.J.; Kleppe, R.; Szigetvari, P.D.; Haavik, J. The Dopamine Hypothesis for ADHD: An Evaluation of Evidence Accumulated from Human Studies and Animal Models. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1492126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoretsanitis, G. The Role of Neurotransmitters in Schizophrenia. Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access 2024, 7, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, T.; See, J.W.; Vijayakumar, V.; Njideaka-Kevin, T.; Loh, H.; Lee, V.J.Q.; Dogrul, B.N. Neurostructural Changes in Schizophrenia and Treatment-Resistance: A Narrative Review. Psychoradiology 2024, 4, kkae015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevets, W.C.; Price, J.L.; Furey, M.L. Brain Structural and Functional Abnormalities in Mood Disorders: Implications for Neurocircuitry Models of Depression. Brain Struct Funct 2008, 213, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.A.; Manaye, K.F.; Liang, C.-L.; Hicks, P.B.; German, D.C. Reduced Number of Mediodorsal and Anterior Thalamic Neurons in Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 2000, 47, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, S.; Jentschke, S.; Argyropoulos, G.P.D.; Chong, W.K.; Gadian, D.G.; Vargha-Khadem, F. Volume Reduction of Caudate Nucleus Is Associated with Movement Coordination Deficits in Patients with Hippocampal Atrophy Due to Perinatal Hypoxia-Ischaemia. Neuroimage Clin 2020, 28, 102429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontiers | The Role of Glial Cells in Mental Illness: A Systematic Review on Astroglia and Microglia as Potential Players in Schizophrenia and Its Cognitive and Emotional Aspects. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fncel.2024.1358450/full (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Dietz, A.G.; Goldman, S.A.; Nedergaard, M. Glial Cells in Schizophrenia: A Unified Hypothesis. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steardo, L.; D’Angelo, M.; Monaco, F.; Di Stefano, V.; Steardo, L. Decoding Neural Circuit Dysregulation in Bipolar Disorder: Toward an Advanced Paradigm for Multidimensional Cognitive, Emotional, and Psychomotor Treatment. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2025, 169, 106030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggi, G.; Klaus, F.; Pryce, C.R. Pathophysiology in Cortico-Amygdala Circuits and Excessive Aversion Processing: The Role of Oligodendrocytes and Myelination. Brain Commun 2024, 6, fcae140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steardo, L.; D’Angelo, M.; Monaco, F.; Di Stefano, V.; Steardo, L. Decoding Neural Circuit Dysregulation in Bipolar Disorder: Toward an Advanced Paradigm for Multidimensional Cognitive, Emotional, and Psychomotor Treatment. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2025, 169, 106030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.N.; Sciarillo, X.A.; Nudelman, J.L.; Cheer, J.F.; Roesch, M.R. Anterior Cingulate Cortex Signals Attention in a Social Paradigm That Manipulates Reward and Shock. Curr Biol 2020, 30, 3724–3735.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Lu, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, H. Social Exclusion Increases the Executive Function of Attention Networks. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar-Szakacs, I.; Uddin, L.Q. Anterior Insula as a Gatekeeper of Executive Control. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2022, 139, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.P.; Robbins, T.W. The Role of Prefrontal Cortex in Cognitive Control and Executive Function. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 47, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- October 30, S.W. 2024 Understanding Neurotransmitters in Schizophrenia Beyond Dopamine. Psychiatrist.com.

- Murray, A.J.; Rogers, J.C.; Katshu, M.Z.U.H.; Liddle, P.F.; Upthegrove, R. Oxidative Stress and the Pathophysiology and Symptom Profile of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 703452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenod, M.; Steullet, P.; Cabungcal, J.-H.; Dwir, D.; Khadimallah, I.; Klauser, P.; Conus, P.; Do, K.Q. Caught in Vicious Circles: A Perspective on Dynamic Feed-Forward Loops Driving Oxidative Stress in Schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1886–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, E.A.; Dmitrieva, E.M.; Parshukova, D.A.; Kazantseva, D.V.; Vasilieva, A.R.; Smirnova, L.P. Oxidative Stress-Related Mechanisms in Schizophrenia Pathogenesis and New Treatment Perspectives. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021, 2021, 8881770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertan Copoglu, U.; Virit, O.; Hanifi Kokacya, M.; Orkmez, M.; Bulbul, F.; Binnur Erbagci, A.; Semiz, M.; Alpak, G.; Unal, A.; Ari, M.; et al. Increased Oxidative Stress and Oxidative DNA Damage in Non-Remission Schizophrenia Patients. Psychiatry Research 2015, 229, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaud, V.; Marzo, A.; Chaumette, B. Oxidative Stress and Emergence of Psychosis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.-F.; Zheng, W.-Y.; Si, T.L.; Su, Z.; Cheung, T.; Jackson, T.; Li, X.-H.; Xiang, Y.-T. Schizophrenia and Oxidative Stress from the Perspective of Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Jia, Q.; Mao, J.; Jiang, S.; Ma, Q.; Luo, X.; An, Z.; Huang, A.; Ma, C.; Yi, Q. The Role of Ferroptosis and Oxidative Stress in Cognitive Deficits among Chronic Schizophrenia Patients: A Multicenter Investigation. Schizophr 2025, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Liu, S. Oxidative Stress and Schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatry and Brain Science 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawani, N.S.; Chan, A.W.; Dursun, S.M.; Baker, G.B. The Underlying Neurobiological Mechanisms of Psychosis: Focus on Neurotransmission Dysregulation, Neuroinflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.K.; Ramadan, H.K.-A.; Elbeh, K.; Haridy, N.A. The Role of Infections and Inflammation in Schizophrenia: Review of the Evidence. Middle East Current Psychiatry 2024, 31, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, D.A.; Vallès, A.; Martens, G.J.M. Oxidative Stress, Prefrontal Cortex Hypomyelination and Cognitive Symptoms in Schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1171–e1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zou, L.; Cai, Y. Progress in the Study of Oxidative Stress Damage in Patients with Schizophrenia: Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loven, D.P.; James, J.F.; Biggs, L.; Little, K.Y. Increased Manganese-Superoxide Dismutase Activity in Postmortem Brain from Neuroleptic-Treated Psychotic Patients. Biological Psychiatry 1996, 40, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.J.; Rogers, J.C.; Katshu, M.Z.U.H.; Liddle, P.F.; Upthegrove, R. Oxidative Stress and the Pathophysiology and Symptom Profile of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zou, L.; Cai, Y. Progress in the Study of Oxidative Stress Damage in Patients with Schizophrenia: Challenges and Opportunities. Front Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1505397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, E.M.; Kurtulmus, A.; Gul, A.Z.; Kocyigit, A.; Kirpinar, I. Oxidative Stress and Schizophrenia: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study of Multiple Oxidative Markers in Patients and Their First-Degree Relatives. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2021, 75, e14711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several Lines of Antioxidant Defense against Oxidative Stress: Antioxidant Enzymes, Nanomaterials with Multiple Enzyme-Mimicking Activities, and Low-Molecular-Weight Antioxidants. Arch Toxicol 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Kim, U.J.; Lee, B.H.; Cha, M. Safeguarding the Brain from Oxidative Damage. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2025, 226, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxidative Stress - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/oxidative-stress (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, A.B.; Samal, R.R.; Bhol, N.K.; Duttaroy, A.K. Cellular Red-Ox System in Health and Disease: The Latest Update. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 162, 114606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljsak, B.; Šuput, D.; Milisav, I. Achieving the Balance between ROS and Antioxidants: When to Use the Synthetic Antioxidants. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013, 2013, 956792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Abdul Manap, A.S.; Attiq, A.; Albokhadaim, I.; Kandeel, M.; Alhojaily, S.M. From Imbalance to Impairment: The Central Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Oxidative Stress-Induced Disorders and Therapeutic Exploration. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda-Rivera, A.K.; Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Arancibia-Hernández, Y.L.; Hernández-Cruz, E.Y.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. RONS and Oxidative Stress: An Overview of Basic Concepts. Oxygen 2022, 2, 437–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Zucca, P.; Varoni, E.M.; Dini, L.; Panzarini, E.; Rajkovic, J.; Tsouh Fokou, P.V.; Azzini, E.; Peluso, I.; et al. Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, U.C.; Bhol, N.K.; Swain, S.K.; Samal, R.R.; Nayak, P.K.; Raina, V.; Panda, S.K.; Kerry, R.G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Neurological Disorders: Mechanisms and Implications. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2025, 15, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fizíková, I.; Dragašek, J.; Račay, P. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Altered Mitochondrial Oxygen, and Energy Metabolism Associated with the Pathogenesis of Schizophrenia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, T.; Wu, A.; Laksono, I.; Prce, I.; Maheandiran, M.; Kiang, M.; Andreazza, A.C.; Mizrahi, R. Mitochondrial Function in Individuals at Clinical High Risk for Psychosis. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, F. The Interplay of Dopamine Metabolism Abnormalities and Mitochondrial Defects in the Pathogenesis of Schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumadewi, K.T.; Harkitasari, S.; Tjandra, D.C. Biomolecular Mechanisms of Epileptic Seizures and Epilepsy: A Review. Acta Epileptologica 2023, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov Kirdajova, D.; Kriska, J.; Tureckova, J.; Anderova, M. Ischemia-Triggered Glutamate Excitotoxicity From the Perspective of Glial Cells. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohmadi, N.H.; Al-kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Albuhadily, A.K.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Jabir, M.S.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; Batiha, G.E.-S. Glutamatergic Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases Focusing on Parkinson’s Disease: Role of Glutamate Modulators. Brain Research Bulletin 2025, 225, 111349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O.; Gerke-Duncan, M.B.; Holsinger, R.M.D. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y. The Initiator of Neuroexcitotoxicity and Ferroptosis in Ischemic Stroke: Glutamate Accumulation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magdaleno Roman, J.Y.; Chapa González, C. Glutamate and Excitotoxicity in Central Nervous System Disorders: Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors as a Target for Neuroprotection. Neuroprotection 2024, 2, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, N.; Giovenzana, M.; Misztak, P.; Mingardi, J.; Musazzi, L. Glutamate-Mediated Excitotoxicity in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Neurodevelopmental and Adult Mental Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Gong, X.; Qin, Z.; Wang, Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Excitotoxicity and Their Relevance to the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases—an Update. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczowska-Łącka, I.; Słowikowski, B.; Piekut, T.; Hurła, M.; Banaszek, N.; Szymanowicz, O.; Jagodziński, P.P.; Kozubski, W.; Permoda-Pachuta, A.; Dorszewska, J. Disorders of Endogenous and Exogenous Antioxidants in Neurological Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several Lines of Antioxidant Defense against Oxidative Stress: Antioxidant Enzymes, Nanomaterials with Multiple Enzyme-Mimicking Activities, and Low-Molecular-Weight Antioxidants. Arch Toxicol 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezema, B.O.; Eze, C.N.; Ayoka, T.O.; Nnadi, C.O. Antioxidant-Enzyme Interaction in Non-Communicable Diseases. Journal of Exploratory Research in Pharmacology 2024, 9, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.-J.; Won, Y.-S.; Kim, E.-K.; Park, S.-I.; Lee, S.J. Free Radicals and Their Impact on Health and Antioxidant Defenses: A Review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeme-Nmom, J.I.; Abioye, R.O.; Flores, S.S.R.; Udenigwe, C.C. Regulation of Redox Enzymes by Nutraceuticals: A Review of the Roles of Antioxidant Polyphenols and Peptides. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 10956–10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, T.; Tian, K.; Li, Z.; Luo, F. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Scavenging Biomaterials for Anti-Inflammatory Diseases: From Mechanism to Therapy. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2023, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, D.E.; Salvadores, N.A.; Moya-Alvarado, G.; Catalán, R.J.; Bronfman, F.C.; Court, F.A. Axonal Degeneration Induced by Glutamate Excitotoxicity Is Mediated by Necroptosis. Journal of Cell Science 2018, 131, jcs214684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Xiao, X. Genetic Insights of Schizophrenia via Single Cell RNA-Sequencing Analyses. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2023, 49, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blog, R.-S. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Uncovers Cell Type-Specific Genetic Insights Underlying Schizophrenia | RNA-Seq Blog 2024.

- Shimu, S.J. A 10-Year Retrospective Quantitative Analysis of The CDC Database: Examining the Prevalence of Depression in the Us Adult Urban Population. Frontiers in Health Informatics 2025, 6053–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwecka, M.; Rajewsky, N.; Rybak-Wolf, A. Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics: Deciphering Brain Complexity in Health and Disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2023, 19, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Xiao, X. Genetic Insights of Schizophrenia via Single Cell RNA-Sequencing Analyses. Schizophr Bull 2023, 49, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehimi, S.N.; Crist, R.C.; Reiner, B.C. Unraveling Psychiatric Disorders through Neural Single-Cell Transcriptomics Approaches. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Tian, R.; Zhou, X.; Tan, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomics Reveals Sox6 Positive Interneurons Enriched in the Prefrontal Cortex of Female Mice Vulnerable to Chronic Social Stress. Mol Psychiatry 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, F.J.; Galinski, S.; Papiol, S.; Falkai, P.G.; Schmitt, A.; Rossner, M.J. Studying and Modulating Schizophrenia-Associated Dysfunctions of Oligodendrocytes with Patient-Specific Cell Systems. npj Schizophr 2018, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, M.; Di Stefano, V.; Pullano, I.; Monaco, F.; Steardo, L. Psychiatric Implications of Genetic Variations in Oligodendrocytes: Insights from hiPSC Models. Life (Basel) 2025, 15, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, R.; Kimura, H.; Ikeda, M. Genetic Association between Gene Expression Profiles in Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells and Psychiatric Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Santo, F.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Fernández-Egea, E.; González-Blanco, L.; Sáiz, P.A.; Giordano, G.M.; Galderisi, S.; Bobes, J. The Dimensional Structure of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale in First-Episode Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: An Exploratory Graph Analysis from the OPTiMiSE Trial. Schizophr 2024, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GEO Accession Viewer. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE181021 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Aguilar Diaz De Leon, J.; Borges, C.R. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress in Biological Samples Using the Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances Assay. J Vis Exp 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsikas, D. Assessment of Lipid Peroxidation by Measuring Malondialdehyde (MDA) and Relatives in Biological Samples: Analytical and Biological Challenges. Anal Biochem 2017, 524, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorlu, M.E.; Uygur, K.K.; Yılmaz, N.S.; Demirel, Ö.Ö.; Aydil, U.; Kızıl, Y.; Uslu, S. Evaluation of Advanced Oxidation Protein Products (AOPP) and Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Tissue Levels in Patients with Nasal Polyps. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2022, 74, 4824–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustarini, D.; Rossi, R.; Milzani, A.; Dalle-Donne, I. Nitrite and Nitrate Measurement by Griess Reagent in Human Plasma: Evaluation of Interferences and Standardization. Methods Enzymol 2008, 440, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, I.; Yurtarslanl, Z.; Canbolat, O.; Akyol, O. A Methodological Approach to Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity Assay Based on Inhibition of Nitroblue Tetrazolium (NBT) Reduction. Clin Chim Acta 1993, 214, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, L.F.; Martins, J.D.; Cavallaro, C.H.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Oliveira, P.J.; Pereira, S.P. Development of a 96-Well Based Assay for Kinetic Determination of Catalase Enzymatic-Activity in Biological Samples. Toxicol In Vitro 2020, 69, 104996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipple, T.E.; Rogers, L.K. Methods for the Determination of Plasma or Tissue Glutathione Levels. Methods Mol Biol 2012, 889, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, V.; Zubair, M.; Minter, D.A. Liver Function Tests. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative Stress in Ischemia/Reperfusion Injuries Following Acute Ischemic Stroke - PMC. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8945353/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Several Lines of Antioxidant Defense against Oxidative Stress: Antioxidant Enzymes, Nanomaterials with Multiple Enzyme-Mimicking Activities, and Low-Molecular-Weight Antioxidants - PMC. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11303474/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Clinical Relevance of Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress - PMC. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4657513/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Yang, H.; Zhang, C.; Yang, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X. Variations of Plasma Oxidative Stress Levels in Male Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia. Correlations with Psychopathology and Matrix Metalloproteinase-9: A Case-Control Study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahake, H.S.; Warade, J.; Kansara, G.S.; Pawade, Y.; Ghangle, S. Study of Malondialdehyde as an Oxidative Stress Marker in Schizophrenia. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2016, 4, 4730–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordiano, R.; Di Gioacchino, M.; Mangifesta, R.; Panzera, C.; Gangemi, S.; Minciullo, P.L. Malondialdehyde as a Potential Oxidative Stress Marker for Allergy-Oriented Diseases: An Update. Molecules 2023, 28, 5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletti, B.; Banaj, N.; Piras, F.; Bossù, P. Schizophrenia and Glutathione: A Challenging Story. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yu, P.; Yang, H.; Huang, C.; Sun, W.; Zhang, X.; Tang, X. Altered Serum Glutathione Disulfide Levels in Acute Relapsed Schizophrenia Are Associated with Clinical Symptoms and Response to Electroconvulsive Therapy. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, T.; Weng, Y.-H.; He, J.; Chen, M.-R.; Chen, Y.; Qi, Z.-Q.; Zhang, Z.-M. A Genetic Variant of the Glutamate-Cysteine Ligase Catalytic Subunit Is Associated with Susceptibility to Ischemic Stroke in the Chinese Population. European Journal of Medical Research 2025, 30, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, E.A.; Dmitrieva, E.M.; Parshukova, D.A.; Kazantseva, D.V.; Vasilieva, A.R.; Smirnova, L.P. Oxidative Stress-Related Mechanisms in Schizophrenia Pathogenesis and New Treatment Perspectives. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 8881770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Yan, M.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Li, J. Aging and Aging-Related Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Interventions and Treatments. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djordjević, V.V.; Kostić, J.; Krivokapić, Ž.; Krtinić, D.; Ranković, M.; Petković, M.; Ćosić, V. Decreased Activity of Erythrocyte Catalase and Glutathione Peroxidase in Patients with Schizophrenia. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yao, L.; Yuan, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Li, L. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Liver Diseases. Genes & Diseases 2024, 11, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, L.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; Pan, Q.; Verstegen, M.M.A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Liver Transplantation and Underlying Diseases: New Insights and Therapeutics. Transplantation 2021, 105, 2362–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allameh, A.; Niayesh-Mehr, R.; Aliarab, A.; Sebastiani, G.; Pantopoulos, K. Oxidative Stress in Liver Pathophysiology and Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, L.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; Pan, Q.; Verstegen, M.M.A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Liver Transplantation and Underlying Diseases: New Insights and Therapeutics. Transplantation 2021, 105, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmanto, A.G.; Yen, T.-L.; Jan, J.-S.; Linh, T.T.D.; Taliyan, R.; Yang, C.-H.; Sheu, J.-R. Beyond Metabolic Messengers: Bile Acids and TGR5 as Pharmacotherapeutic Intervention for Psychiatric Disorders. Pharmacological Research 2025, 211, 107564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, R.K.; Brindle, W.M.; Donnelly, M.C.; McConville, P.M.; Stroud, T.G.; Bandieri, L.; Plevris, J.N. Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review. World J Gastroenterol 2022, 28, 5515–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangopadhyay, A.; Ibrahim, R.; Theberge, K.; May, M.; Houseknecht, K.L. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Mental Illness: Mechanisms Linking Mood, Metabolism and Medicines. Front Neurosci 2022, 16, 1042442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Angona, Ó.; Anmella, G.; Valdés-Florido, M.J.; De Uribe-Viloria, N.; Carvalho, A.F.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Berk, M. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) as a Neglected Metabolic Companion of Psychiatric Disorders: Common Pathways and Future Approaches. BMC Medicine 2020, 18, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davinelli, S.; Medoro, A.; Siracusano, M.; Savino, R.; Saso, L.; Scapagnini, G.; Mazzone, L. Oxidative Stress Response and NRF2 Signaling Pathway in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Redox Biology 2025, 83, 103661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Q.; Kosten, T.R.; Zhang, X.Y. Free Radicals, Antioxidant Defense Systems, and Schizophrenia. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2013, 46, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, U.C.; Bhol, N.K.; Swain, S.K.; Samal, R.R.; Nayak, P.K.; Raina, V.; Panda, S.K.; Kerry, R.G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Neurological Disorders: Mechanisms and Implications. Acta Pharm Sin B 2025, 15, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, X.X.; Tang, P.Y.; Tee, S.F. Blood-Based Oxidation Markers in Medicated and Unmedicated Schizophrenia Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2022, 67, 102932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Enzyme Levels in Patients with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder - Kuloglu - 2002 - Cell Biochemistry and Function - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://analyticalsciencejournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/cbf.940 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Grignon, S.; Chianetta, J.M. Assessment of Malondialdehyde Levels in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis and Some Methodological Considerations. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2007, 31, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.M.N.; Sultana, F.; Uddin, Md.G.; Dewan, S.M.R.; Hossain, M.K.; Islam, M.S. Effect of Antioxidant, Malondialdehyde, Macro-mineral, and Trace Element Serum Concentrations in Bangladeshi Patients with Schizophrenia: A Case-control Study. Health Sci Rep 2021, 4, e291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serum Malonyldialdehyde Levels of Patients with Schizophrenia. Available online: http://psychiatry-psychopharmacology.com/en/serum-malonyldialdehyde-levels-of-patients-with-schizophrenia-13652 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Uddin, S.M.N.; Sultana, F.; Uddin, Md.G.; Dewan, S.M.R.; Hossain, M.K.; Islam, M.S. Effect of Antioxidant, Malondialdehyde, Macro-Mineral, and Trace Element Serum Concentrations in Bangladeshi Patients with Schizophrenia: A Case-Control Study. Health Science Reports 2021, 4, e291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.-L.; Hwu, H.-G.; Hwang, T.-J.; Hsieh, M.H.; Liu, C.-C.; Lin-Shiau, S.-Y.; Liu, C.-M. Clinical Implications of Oxidative Stress in Schizophrenia: Acute Relapse and Chronic Stable Phase. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2020, 99, 109868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, M.; Atig, F.; Mhalla, A.; Kerkeni, A.; Mechri, A. Decreased Glutathione Levels and Impaired Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Drug-Naive First-Episode Schizophrenic Patients. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mednova, I.A.; Smirnova, L.P.; Vasilieva, A.R.; Kazantseva, D.V.; Epimakhova, E.V.; Krotenko, N.M.; Semke, A.V.; Ivanova, S.A. Immunoglobulins G of Patients with Schizophrenia Protects from Superoxide: Pilot Results. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenod, M.; Steullet, P.; Cabungcal, J.-H.; Dwir, D.; Khadimallah, I.; Klauser, P.; Conus, P.; Do, K.Q. Caught in Vicious Circles: A Perspective on Dynamic Feed-Forward Loops Driving Oxidative Stress in Schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1886–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buosi, P.; Borghi, F.A.; Lopes, A.M.; Facincani, I. da S.; Fernandes-Ferreira, R.; Oliveira-Brancati, C.I.F.; do Carmo, T.S.; Souza, D.R.S.; da Silva, D.G.H.; de Almeida, E.A.; et al. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Treatment-Responsive and Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia Patients. Trends Psychiatry Psychother 2021, 43, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxidative Stress and Emergence of Psychosis. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/11/10/1870 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Pei, J.; Pan, X.; Wei, G.; Hua, Y. Research Progress of Glutathione Peroxidase Family (GPX) in Redoxidation. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjević, V.V.; Kostić, J.; Krivokapić, Ž.; Krtinić, D.; Ranković, M.; Petković, M.; Ćosić, V. Decreased Activity of Erythrocyte Catalase and Glutathione Peroxidase in Patients with Schizophrenia. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrico, F.; Laurance, S.; Lopez, A.C.; Lefevre, S.D.; Thomson, L.; Möller, M.N.; Ostuni, M.A. Oxidative Stress in Healthy and Pathological Red Blood Cells. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Pan, X.; Wei, G.; Hua, Y. Research Progress of Glutathione Peroxidase Family (GPX) in Redoxidation. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, M.; Mechri, A.; Othman, L.B.; Fendri, C.; Gaha, L.; Kerkeni, A. Decreased Glutathione Levels and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Untreated and Treated Schizophrenic Patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2009, 33, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, M.; Atig, F.; Mhalla, A.; Kerkeni, A.; Mechri, A. Decreased Glutathione Levels and Impaired Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Drug-Naive First-Episode Schizophrenic Patients. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).