1. Introduction

In recent decades, the landscape of youth sport has evolved dramatically, with increasing numbers of children and adolescents engaging in structured training programs and sport-specific competition from an early age. Driven by the desire for early talent identification and long-term elite performance, this trend has led to an increase in early specialization, where young athletes commit to a single sport, often year-round, before adolescence [

1]. While this approach may offer short-term performance gains and competitive advantages, it also raises significant concerns regarding the physiological, psychological, and developmental consequences of intense training loads during critical periods of growth and maturation [

3,

4].

Young athletes differ fundamentally from adults in terms of their biological, neuromuscular, and psychosocial development. Chronological age alone is a poor indicator of training readiness, as substantial inter-individual variation exists in biological maturation, particularly during the adolescent growth spurt [

5]. Failure to account for this variability in training and testing protocols can lead to misinterpretation of performance metrics, inappropriate load prescription, and increased risk of overuse injuries [

6,

7]. Moreover, the tendency to apply adult-based testing batteries and periodization models to youth populations overlooks key developmental needs and windows of trainability [

8].

There is a growing body of literature emphasizing the importance of developmentally appropriate and sport-specific strategies in the assessment and conditioning of youth athletes [

9,

10]. However, inconsistency remains in the implementation of evidence-informed practices across sports contexts, and limited consensus exists regarding optimal testing protocols, skill development priorities, or the balance between specialization and diversification [

11].

Furthermore, the increasing tendency toward early specialization often leads to the premature implementation of adult-derived testing models in youth populations. These protocols may neglect the dynamic interplay between biological age, psychological readiness, and technical development [

2,

4]. As such, performance assessments in youth sport must be contextualized within developmental models that prioritize age-appropriate skill acquisition and long-term athletic progression. The Developmental Model of Sport Participation (DMSP), for example, emphasizes a “sampling phase” during early adolescence, encouraging broad engagement in varied physical activities before progressive specialization [

11]. This model supports the need for adaptable testing and training strategies that align with athletes’ maturity trajectories rather than rigid chronological timelines. Given the unique physiological profile and injury susceptibility of youth athletes, it is imperative to examine current training and testing strategies through the lens of biological age and long-term development. This critical review aims to:

Synthesize the current evidence on training and testing approaches in youth sports;

Highlight the implications of growth, maturation, and specialization on athletic performance and injury risk;

Provide practical, developmentally aligned recommendations to support safe and effective youth athlete development across various sport disciplines.

2. Methodology

This review was conducted as a structured critical analysis of current research on training and testing strategies in young athletes, with a focus on age-appropriate practices, biological maturation, and the implications of early specialization across sport disciplines.

2.1. Search Strategy

Relevant studies were identified through a structured literature search in the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search covered publications from January 2000 to March 2025. Search terms were combined using Boolean operators and included:

“youth athletes” AND “training”,

“exercise testing” AND “adolescents”,

“growth and maturation”,

“early specialization”,

“long-term athlete development”,

“load monitoring”,

“injury risk” AND “developmental stage”.

Additional relevant studies were identified through reference tracking of key reviews and consensus papers.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they:

Focused on athletes aged 10 to 18 years;

Reported exercise testing, training strategies, or maturation-specific adaptations;

Were published in peer-reviewed journals in English.

Exclusion criteria included:

Studies focused solely on adult or elderly populations;

Non-sport-specific medical reviews;

Narrative articles without evidence-based focus.

2.3. Selection and Synthesis

After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Full texts of eligible studies were assessed for inclusion. A total of 87 studies were selected for thematic synthesis, including experimental studies, systematic reviews, position statements, and applied sports science reports. The included studies were categorized thematically under:

growth and maturation,

exercise testing,

training load and periodization,

motor skill development, and

early specialization.

The synthesis was structured to evaluate comparative effectiveness, developmental appropriateness, and practical applicability across youth sports contexts. No formal meta-analysis was conducted, as the heterogeneity in study design and outcomes precluded quantitative pooling.

Of the 87 studies included, 19 addressed growth and maturation, 16 focused on exercise testing, 18 examined training load and periodization, 15 explored motor skill development, and 19 analyzed the effects of early specialization and diversification. This thematic distribution reflects a balanced foundation across physiological, pedagogical, and developmental domains in youth sport science.

3. Thematic Synthesis of Current Training and Testing Strategies

This section presents a thematic synthesis of current evidence regarding training and testing strategies for young athletes, structured around five key domains: biological maturation, physical testing, training load and periodization, motor skill development, and early specialization. These domains were selected based on their consistent appearance across the literature and their practical relevance to the safe and effective management of youth athletic development. The subsections aim to critically analyze how developmental factors impact performance, injury risk, and long-term athlete progression across various sport disciplines.

3.1. Growth, Maturation, and Biological Variability in Young Athletes

Youth athletic development must be understood within the broader context of biological maturation, which does not always align with chronological age. While many training and testing programs rely on age-based grouping, considerable inter-individual variation exists in the timing and tempo of maturation, leading to disparities in physical capacity, injury risk, and training responsiveness among similarly aged athletes [

5].

The most widely used method to estimate biological maturation is the

maturity offset model, particularly the Mirwald equation, which predicts the number of years from

Peak Height Velocity (PHV) - a key marker of pubertal growth [

7]. PHV is associated with significant changes in neuromuscular control, hormonal profiles, and musculoskeletal structure, all of which influence athletic performance [

6]. However, the use of PHV-based models must be approached with caution due to their reduced accuracy in early- or late-maturing individuals, especially females [

13].

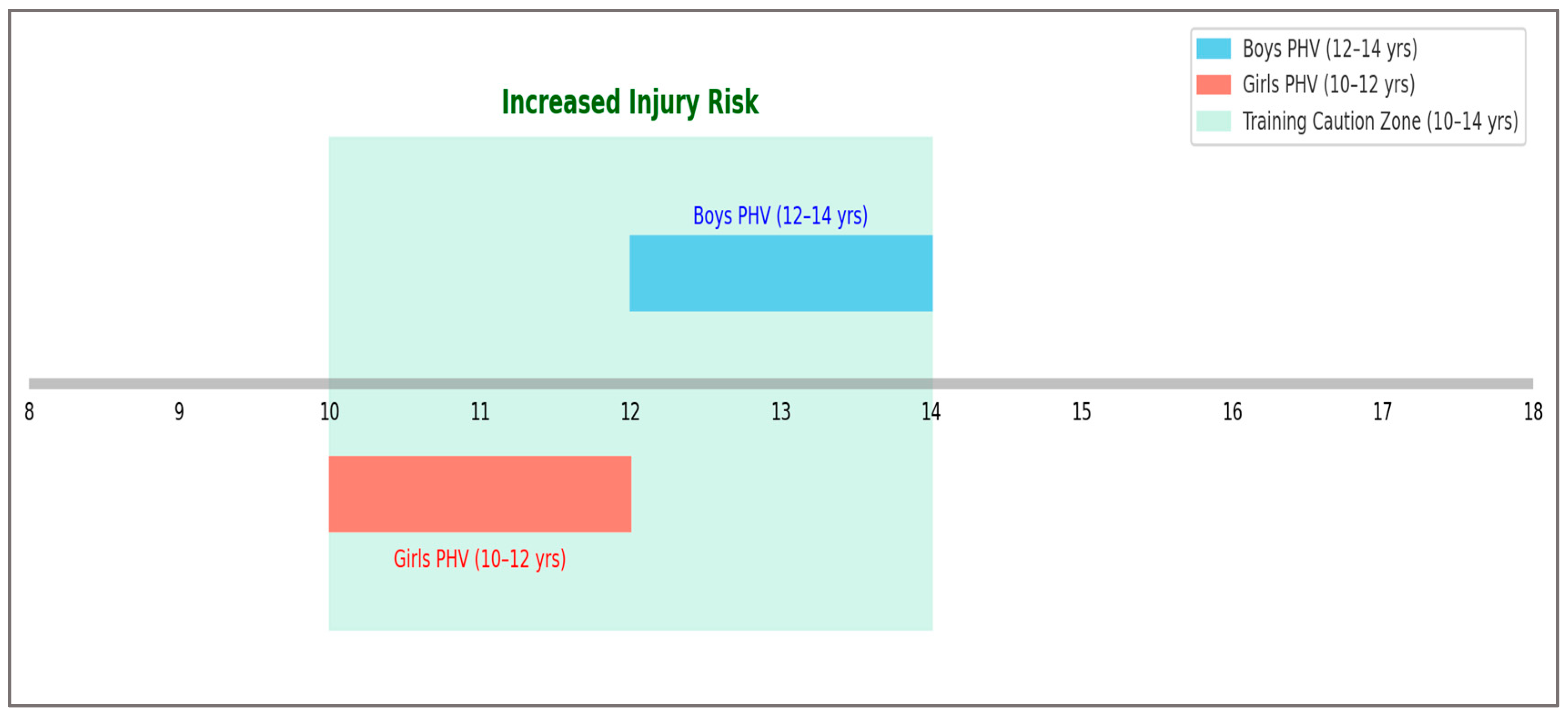

Figure 1 illustrates the age-related variations in peak height velocity (PHV) and highlights critical periods during which young athletes experience increased susceptibility to injury.

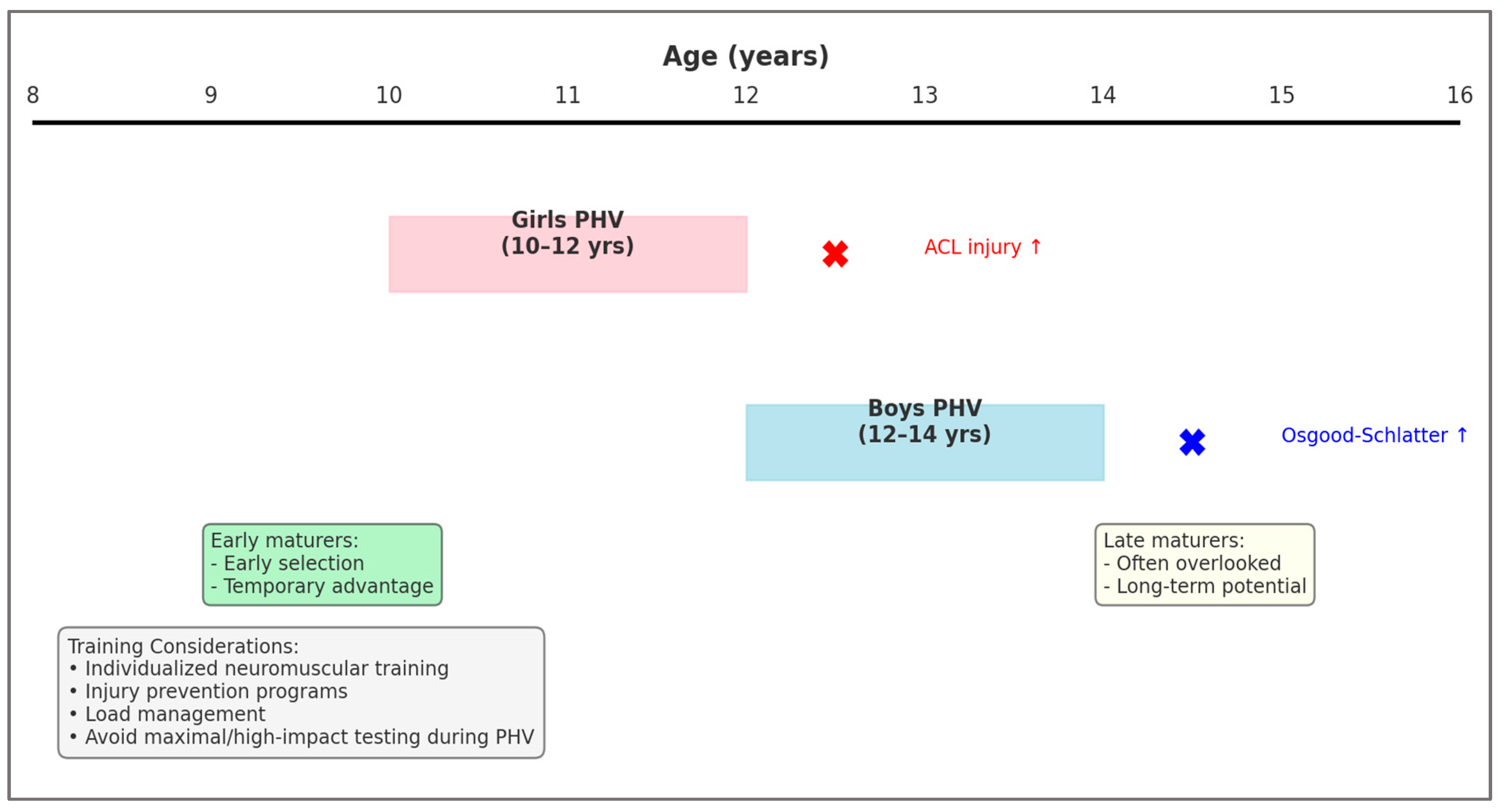

It is also important to recognize sex-specific differences in maturation trajectories. Females typically reach peak height velocity approximately 1 to 2 years earlier than males, often between the ages of 10 and 12, compared to 12 to 14 in boys [

5]. This earlier onset of maturation can coincide with increased vulnerability to specific injuries, such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears and patellofemoral pain, due to hormonal changes and altered neuromuscular control [

6]. Additionally, maturity offset prediction models, including the Mirwald equation, show reduced accuracy in early- or late-maturing girls, which may affect testing interpretation and load prescription. Training interventions should account for these differences by incorporating tailored neuromuscular training and injury-prevention strategies, particularly during early adolescence.

Athletes who mature early often demonstrate temporary advantages in size, strength, and power, which may lead to early selection in talent pathways. Conversely, late maturers may be overlooked despite long-term potential, highlighting the need for maturation-aware assessment and coaching strategies [

14]. Failure to account for these differences may contribute to overuse injuries, early dropout, or misclassification in talent identification systems.

Training programs should consider

growth-related vulnerability periods, particularly during PHV, when athletes experience increased injury risk due to structural imbalances and reduced neuromuscular coordination [

3]. Conditions such as apophysitis, Osgood-Schlatter disease, and tendinopathies are more common in this period [

2]. Load management, neuromuscular training, and individualized conditioning during these stages are essential. Testing batteries should also be adapted to ensure safety and validity, avoiding maximal-load or high-impact assessments during peak growth phases [

8].

Understanding and visualizing the sex-specific trajectories in adolescent maturation is crucial for effective injury prevention and optimized training programs. Differences in timing and intensity of growth spurts, notably peak height velocity (PHV), significantly influence the vulnerability to specific injuries in young athletes..

As depicted in

Figure 2, recognizing and addressing these maturation-specific windows of increased vulnerability are essential to implementing individualized training protocols. Coaches, trainers, and clinicians should use such insights to improve athlete monitoring and reduce injury incidence, particularly during critical developmental phases.

In summary, a biologically informed approach that integrates maturity status into testing and training design is essential to optimize development, prevent injury, and support long-term athlete retention. Understanding these maturational differences is essential for designing safe and effective training strategies.

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of early and late maturers across key physiological and developmental domains relevant to youth sports performance and injury prevention.

3.2. Exercise Testing in Youth Athletes

Exercise testing in youth athletes plays a crucial role in monitoring performance, guiding training decisions, and reducing injury risk. However, the application of testing protocols in this population must consider the ongoing processes of growth, maturation, and neuromuscular development. Unlike adult athletes, young individuals exhibit high inter-individual variability in physical responses, influenced by maturity offset, hormonal status, and training experience [

5,

6].

A common limitation in youth testing is the inappropriate use of adult-based protocols, which may not reflect the physiological reality of developing athletes. For example, maximal aerobic or anaerobic tests such as the VO₂max treadmill test or Wingate cycle ergometer test may be unreliable in younger populations due to motivation, technical execution, and musculoskeletal readiness [

14,

15]. Field-based alternatives such as the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test (IR1) or Multi-Stage Fitness Test (beep test) are often used instead, though they still require careful interpretation with respect to maturation status and training history [

16].

Neuromuscular testing, including vertical jump, sprint speed, and agility drills (e.g., T-test, 505 drill), is frequently employed to monitor motor development. However, these tests are sensitive to anthropometric changes, particularly during peak height velocity (PHV), when temporary declines in coordination and movement efficiency are common [

17]. Therefore, repeated testing across growth phases is recommended to distinguish between true training effects and growth-related changes [

18].

For injury prevention and movement screening, tests such as the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) and Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) have gained popularity. While these offer valuable insights into movement quality and asymmetries, their validity in younger populations remains under scrutiny, particularly when used without age-specific benchmarks [

19].

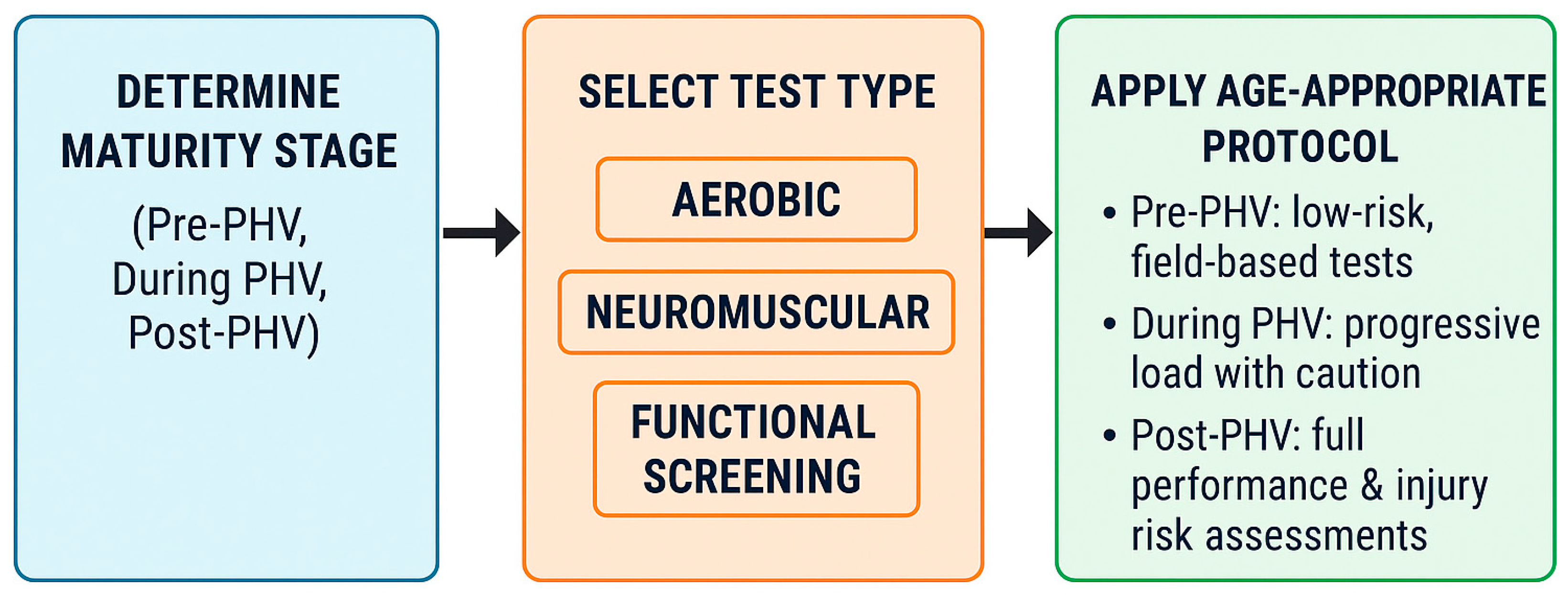

Ultimately, the selection of exercise tests for youth athletes should be guided by their biological age, sport specificity, and developmental objectives. Testing batteries should be flexible, low-risk, and capable of producing actionable insights for both coaches and medical staff.

Table 2 presents specific testing recommendations across five major sports, highlighting how test selection should vary between pre- and post-peak height velocity (PHV) stages.

The table differentiates recommended tests for major sports - football, basketball, gymnastics, swimming, and tennis - according to pre-PHV and during/post-PHV developmental stages to guide age-appropriate performance assessments.

Where possible, longitudinal testing protocols - tracking individual athletes over time, offer the most accurate depiction of progress, as they allow for maturation-adjusted interpretation [

20].

To assist in selecting appropriate exercise tests for youth athletes, the following flowchart in

Figure 3 summarizes key decision points based on biological maturity, test category, and developmental considerations.

In summary, the selection of exercise tests for youth athletes should be guided by biological age, sport specificity, and developmental objectives, with careful attention to periods of heightened injury risk.

3.3. Training Load and Periodization for Young Athletes

Effective training load management in youth athletes must consider not only physiological development but also the heightened risk of specific injuries during periods of rapid growth and maturation. A practical overview of common injury types, risk factors, and recommended assessment protocols across exampled sports is presented in

Table 3. This summary provides coaches, clinicians, and practitioners with actionable information to optimize both training and injury prevention throughout key maturational stages.

These sport- and age-specific injury patterns highlight the need for adaptable load management strategies, which will be addressed in the following discussion on periodization and training practices for young athletes.

Effective training load management and carefully structured periodization are essential in youth sport to promote adaptation, reduce injury risk, and support long-term performance progression. However, applying adult models of periodization and intensity distribution to young athletes often overlooks their unique physiological constraints and fluctuating maturity status [

21].

Understanding Load in Youth

Training load in youth is typically classified into:

External load (e.g., distance run, repetitions, speed)

Internal load (e.g., heart rate, rate of perceived exertion - RPE, hormonal response)

The ability to tolerate and respond to these loads is significantly influenced by growth-related factors, including peak height velocity (PHV), neuromuscular coordination, and musculoskeletal development [

22].

Young athletes undergoing rapid growth phases experience temporary performance plateaus or regressions, often due to altered limb mechanics, disrupted coordination, and energy inefficiency [

17]. During these periods, training intensity and volume should be adjusted proactively, with a focus on neuromuscular stability, mobility, and injury prevention.

Periodization Principles

While classical periodization models (macro-, meso-, and micro-cycles) have been adapted for elite athletes, youth training should be more flexible and nonlinear, particularly before and during PHV [

23]. Shorter training blocks (e.g., 2–3 weeks) with varied stimuli (strength, speed, skill, play) are recommended to avoid monotony and overuse.

Block periodization may be suitable in older adolescents (post-PHV) with greater physiological resilience and sport specialization. However, the emphasis should remain on multi-component development - speed, strength, mobility, and technical skill - rather than early over-specialization in any single area [

2].

Load Monitoring Strategies

Appropriate load monitoring in youth requires a balance between objective and subjective measures:

Objective tools: heart rate monitors, GPS units, session duration, jump-based neuromuscular diagnostics

Subjective tools: RPE scales (e.g., CR-10 or modified Borg), wellness questionnaires, fatigue and soreness check-ins [

24]

Coaches should interpret load data in the context of maturity offset, training history, and individual responsiveness. Overreliance on cumulative volume metrics can mask early signs of overload or misinterpret natural developmental fluctuations.

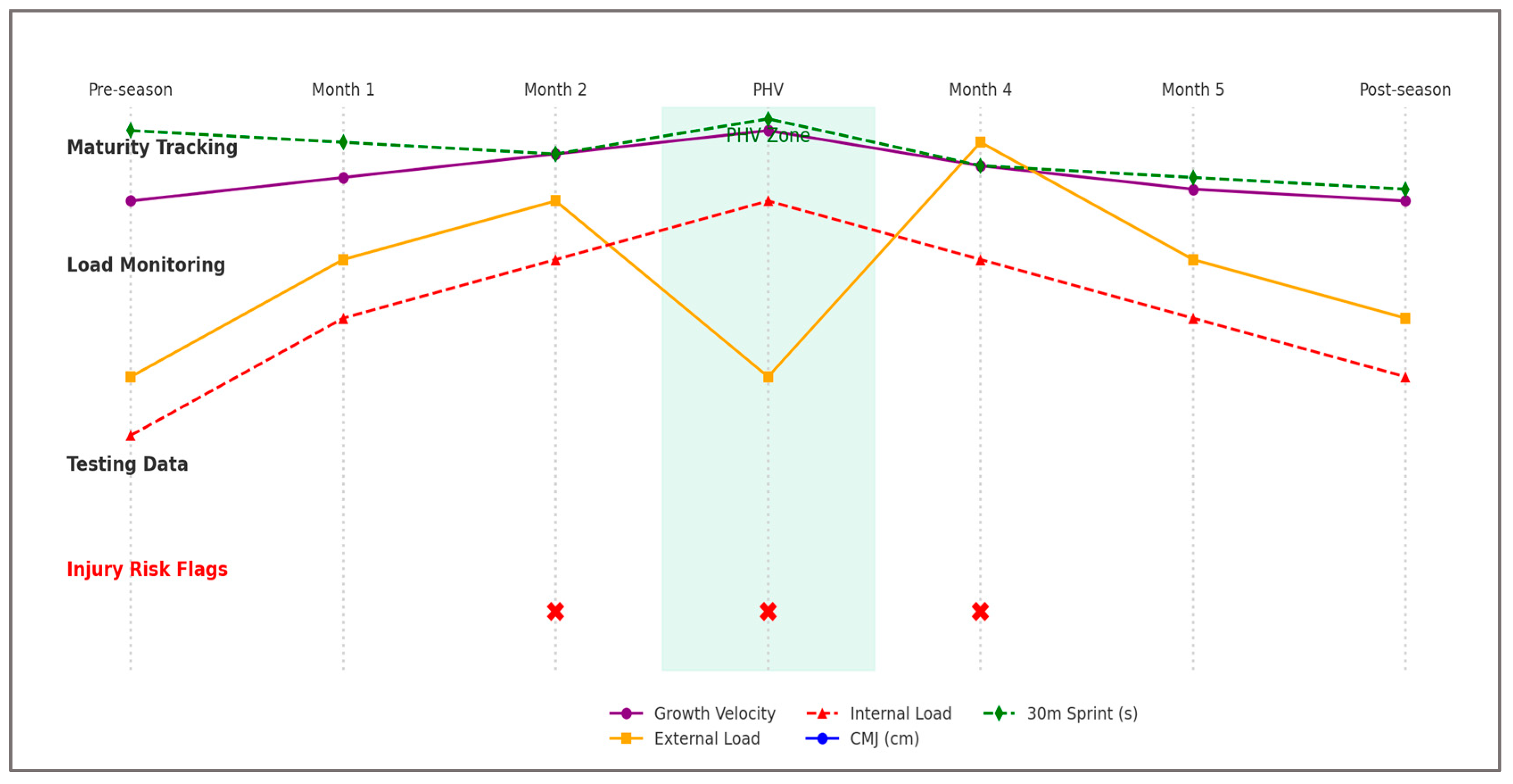

To better illustrate how these multiple factors can be integrated,

Figure 4 presents an athlete monitoring dashboard that aligns biological maturity, training load, performance testing, and injury risk indicators over the course of a season. This approach enables coaches and practitioners to make more individualized, timely, and data-informed adjustments throughout key developmental periods.

Injury Risk and Recovery

High training loads relative to individual capacity have been repeatedly linked to overuse injuries in adolescent athletes, especially during the 6-12 months surrounding PHV [

3]. Adequate recovery protocols - rest, sleep hygiene, mobility training, and psychological decompression - are essential for sustainable development.

Recovery is a critical, yet often underemphasized, component of youth training programs. Adolescents require 8–10 hours of quality sleep per night to support musculoskeletal repair, hormonal balance, and neurocognitive function [

5]. During PHV, recovery demands may be even higher due to accelerated tissue turnover and fatigue accumulation [

3]. Coaches should periodically implement “deload” microcycles - 1 to 2 weeks of reduced volume and intensity - to minimize overload during rapid growth phases [

4]. Additionally, mobility sessions, neuromuscular reset routines, and low-impact play-based activities can promote recovery without detraining. Psychological decompression strategies - such as team-based recreation, mindfulness practices, or structured rest days - also play an essential role in reducing mental fatigue and sustaining motivation across training cycles [

24].

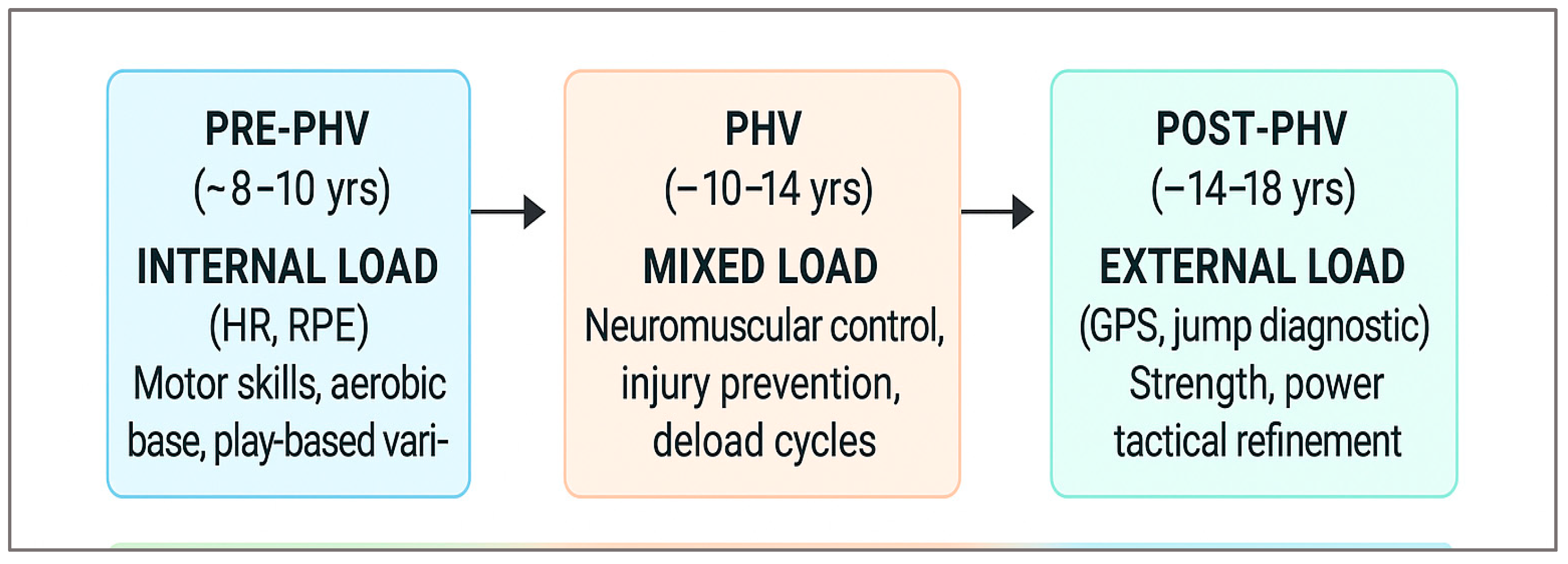

Figure 5 illustrates a periodized training model aligned with biological maturation stages, highlighting the progression of load type and primary training emphasis across pre-, during-, and post-PHV phases.

While

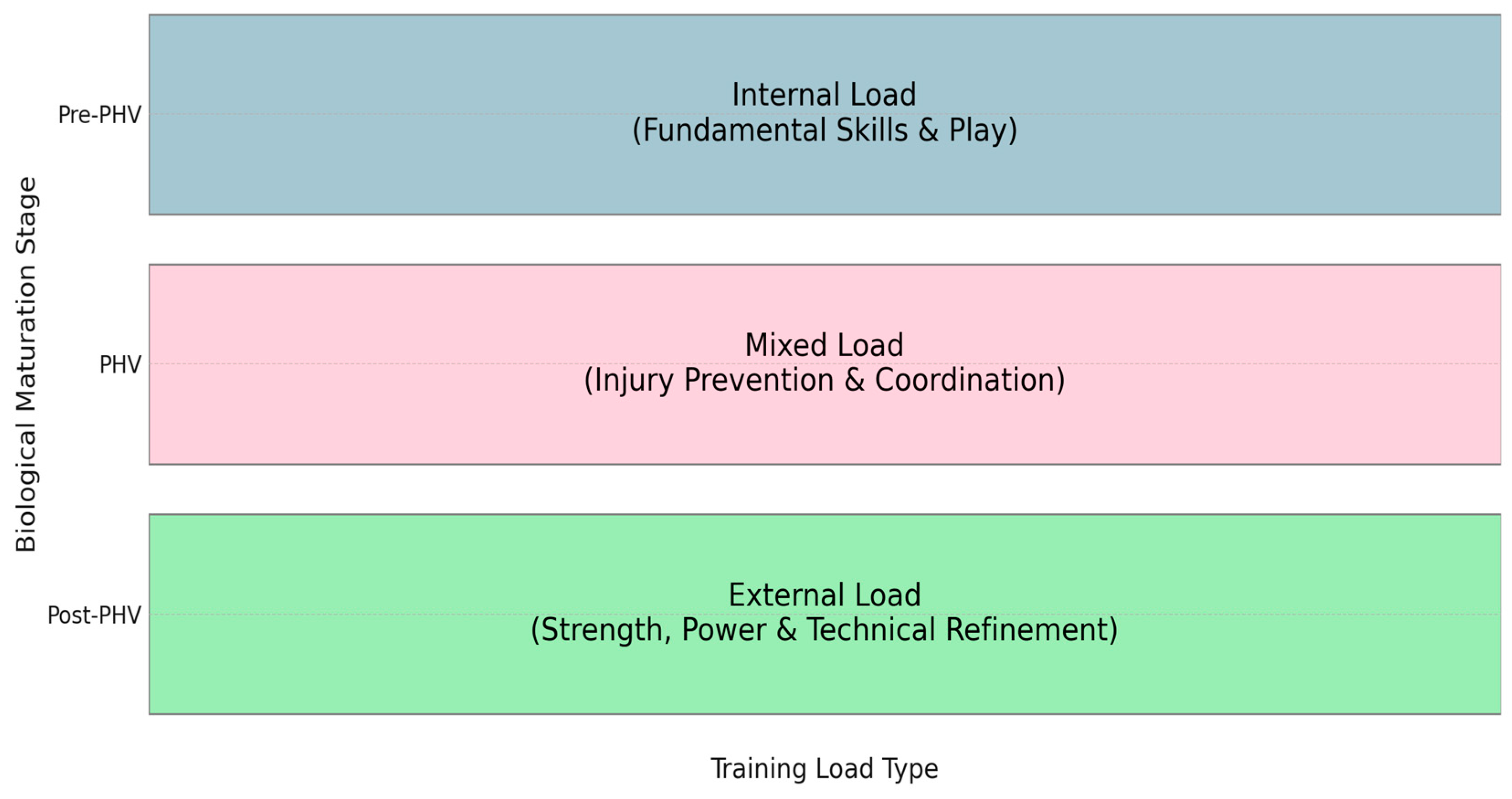

Figure 5 outlines a structured periodization model across maturation stages, the following

Figure 6 provides a concise visual alignment between biological age and the dominant type of training load recommended at each phase:

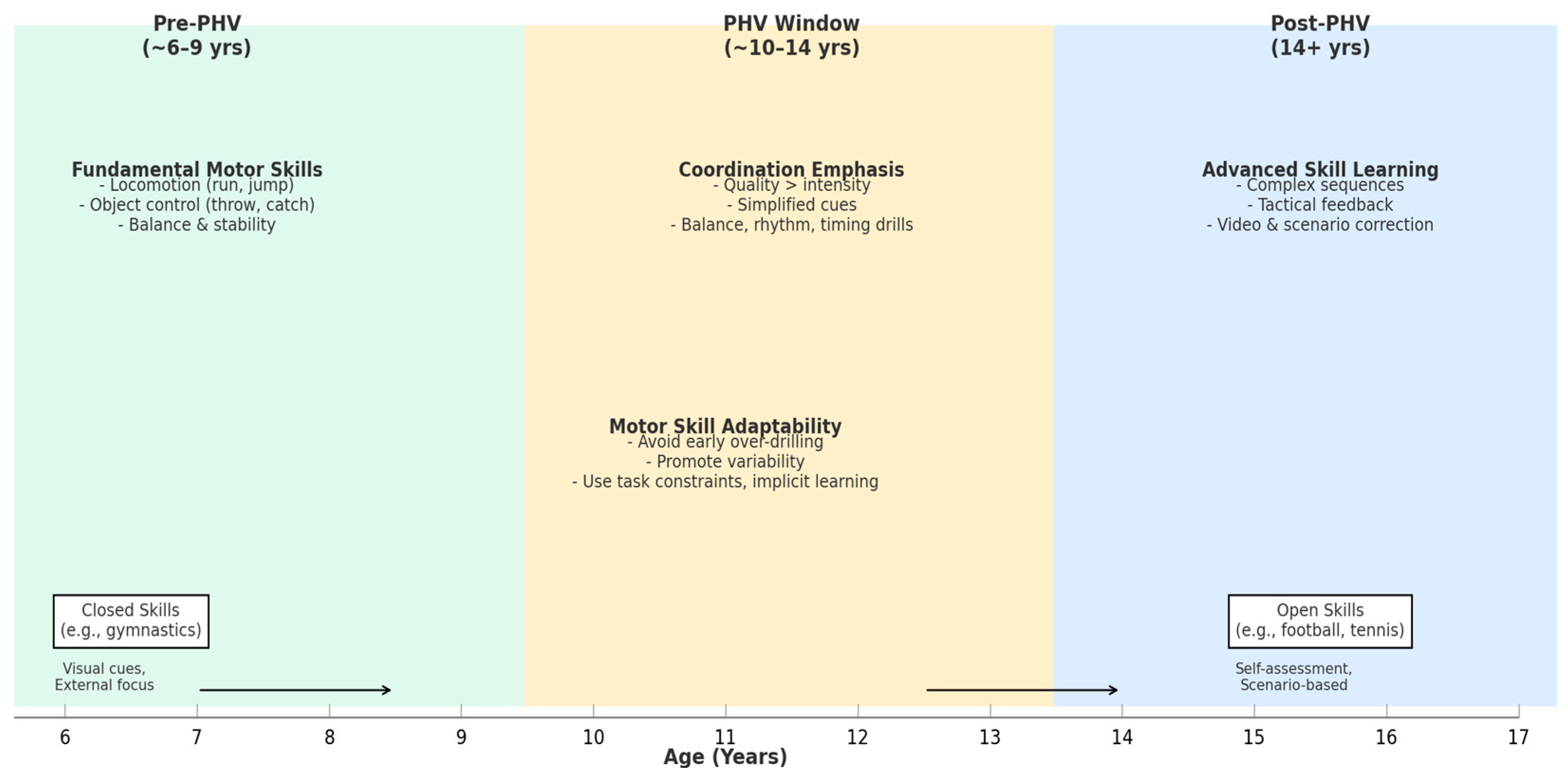

3.4. Motor Skill Development and Psychological Considerations

Motor skill acquisition during youth is a central component of athletic development. The interplay between biological maturation and neural plasticity provides a sensitive period in which technical proficiency, coordination, and movement variability can be significantly enhanced [

6]. Coaches and practitioners must therefore design age- and stage-appropriate training environments that prioritize long-term skill adaptability over early performance peaks.

Fundamental Motor Skills as a Foundation

Before sport-specific techniques are emphasized, youth athletes should develop a solid foundation of fundamental motor skills (FMS) - locomotion (e.g., running, jumping), object control (e.g., throwing, catching), and balance/stability (e.g., single-leg stance, landing) [

26]. Mastery of these skills has been shown to predict future sport participation, movement competence, and injury resistance [

27].

Training environments for children aged 6–12 should be exploratory, varied, and playful, enabling natural neuromuscular development and intrinsic feedback through movement challenges [

4].

Skill Progression Across Maturation

As athletes transition through PHV, neuromuscular control can temporarily decline due to limb length changes, decreased coordination, and altered force application. During this time, technical instruction should emphasize:

Post-PHV, the window for refined skill learning opens again, making it ideal to introduce more complex movement sequences, individualized technical feedback, and sport-specific tactical development.

Long-Term Skill Adaptability

Rigid, repetitive technique drilling at early ages may reduce movement variability, which is critical for robust skill transfer. Instead, variable practice models - task constraints, differential learning, and implicit instruction - promote adaptability, error tolerance, and performance under pressure [

29].

An important distinction in motor skill training lies between open and closed skills. Closed skills, such as gymnastics routines or sprint starts, occur in predictable environments and benefit from precise, repetitive execution. In contrast, open skills - such as passing in football or reacting in tennis - require adaptability to dynamic, unpredictable conditions. During youth development, a balanced emphasis on both types is essential. However, prioritizing open-skill contexts during key sensitive periods fosters perceptual-motor coupling, decision-making under pressure, and long-term transferability across sport situations [

26,

28].

Feedback strategies should also evolve:

Early stages: visual cues and external focus

Later stages: self-assessment, video review, and scenario-based correction

Figure 7 illustrates the progression of motor skill development across key maturation stages, emphasizing the PHV period (10–14 years) as a sensitive window for coordination-focused training.

Ultimately, motor skill development in youth should be guided not by early specialization or short-term outcomes, but by a flexible, maturation-aware approach that fosters coordination, adaptability, and a lifelong foundation for athletic performance.

Psychological Considerations in Youth Athlete Development

Mental resilience and effective psychological coping strategies play a crucial role in the holistic development of young athletes. During critical developmental phases, especially around peak height velocity (PHV), young athletes often experience heightened psychological stress due to physical changes, fluctuating performance, and increased competitive pressures. Coaches and trainers should proactively integrate age-appropriate mental training techniques such as mindfulness, goal-setting, visualization, and stress management exercises. Emphasizing mental resilience through controlled exposure to competitive situations, structured feedback, and fostering a supportive environment enhances athletes' emotional stability, motivation, and long-term commitment to sports participation.

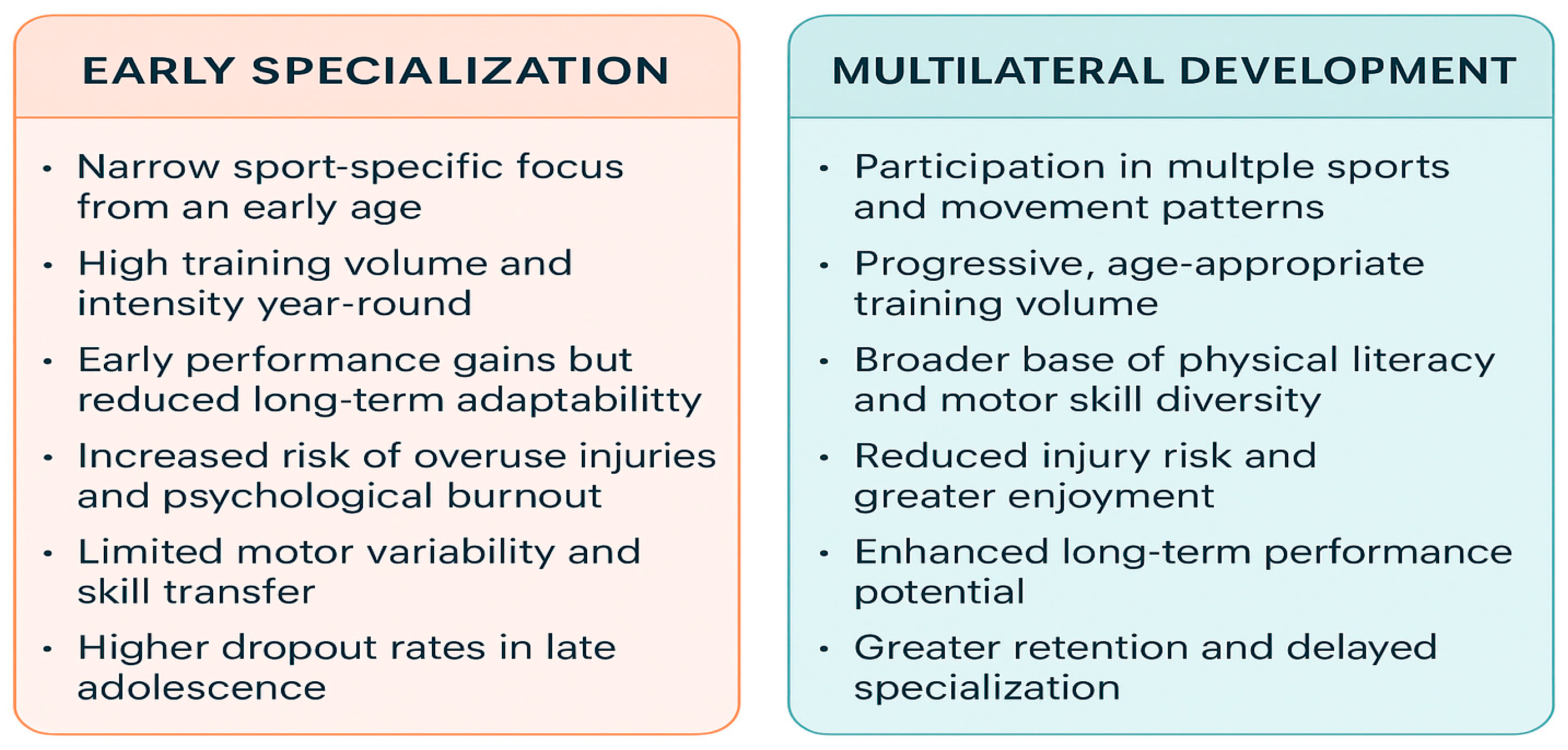

3.5. Early Specialization vs Multisport Participation

The debate between early specialization and multilateral development is central to youth athlete training philosophy. While some sports (e.g., gymnastics, figure skating) appear to reward early sport-specific commitment, evidence increasingly supports the benefits of a diversified, multilateral training background for most young athletes.

Early Specialization: Definition and Risks

Early specialization refers to intensive training in one sport from a young age, often before age 12, with the exclusion of other sports and activities. This model typically emphasizes high training volumes, year-round participation, and early competitive engagement [

3].

While early specialization can lead to rapid technical skill acquisition and short-term performance benefits, it is associated with a higher incidence of:

Overuse injuries (e.g., Osgood-Schlatter, stress fractures)

Psychological burnout and motivation loss

Reduced overall motor skill versatility

Early dropout from sport participation [

4,

6]

Multilateral Development: Definition and Benefits

Multilateral (or diversified) development involves engaging youth in multiple sports and physical activities, often rotating across seasons. It emphasizes a broad base of physical literacy, neuromuscular development, and general athleticism [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Evidence supports that this approach:

Enhances motor skill transfer across sports

Reduces the risk of overuse injuries

Improves long-term athlete retention and enjoyment

Increases the likelihood of reaching elite levels in late-specialization sports (e.g., football, basketball, athletics) [

11]

The “sampling phase” model, as advocated in the Developmental Model of Sport Participation (DMSP), proposes that early sport engagement should be broad and play-focused, with gradual specialization emerging post-PHV and around mid-adolescence (ages 14–16) [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

Individual and Sport-Specific Considerations

For example, consider two youth athletes at age 11. Athlete A specializes early in tennis, training year-round with limited engagement in other sports. While technically advanced, she begins to experience chronic shoulder pain and reports declining enjoyment by age 14. In contrast, Athlete B participates in multiple sports - football in autumn, basketball in winter, and athletics in summer - developing broad motor skills and maintaining high motivation. By age 15, he begins to specialize in football, carrying forward transferable skills and demonstrating resilience in competitive settings. These contrasting pathways reflect the core principles outlined in the DMSP, reinforcing that early sampling and delayed specialization often support more sustainable long-term athlete development [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46].

Not all athletes or sports benefit equally from delayed specialization. Sports requiring high levels of flexibility and aesthetic motor control - like rhythmic gymnastics or diving - often necessitate earlier specialization due to peak performance occurring in adolescence [

31].

However, in most sports, early diversification supports better physiological development, decision-making adaptability, and psychological resilience. Coaches should assess an athlete’s biological age, sport demands, and psychosocial environment before committing to a specialized track.

Illustrative Case Studies

Early Specialization – Jennifer Capriati (tennis)

Jennifer Capriati is a well-documented example of an athlete who followed an early specialization pathway. Starting her professional tennis career at the young age of 13, Capriati quickly achieved impressive international success. However, constant pressure, physical overload, and the lack of adequate diversification led to psychological issues, burnout, and significant personal difficulties. These challenges culminated in an extended break during her adolescence, demonstrating the potential risks associated with intense early specialization.

Multisport Participation – Roger Federer (tennis)

In contrast, Roger Federer's career illustrates the benefits of multisport participation during childhood and adolescence. Federer engaged in various sports, including football, badminton, and table tennis, choosing to specialize in tennis only later in his adolescence. This approach allowed him to develop a broad range of motor skills and significant mental flexibility, directly contributing to his longevity and exceptional performance in professional tennis.

These real-life examples underscore major differences between the two approaches and support the general recommendation favoring a multisport approach in the early stages of athletic development.

To further illustrate these contrasting development pathways,

Figure 8 compares the core characteristics and long-term outcomes of early specialization versus multilateral development in youth athlete

4. Discussion

This article highlights the need for biologically informed, sport-specific strategies when designing training and testing programs for youth athletes. Across Sections 3 to 5.5, it becomes evident that growth and maturation introduce both opportunities and vulnerabilities that must be carefully managed through individualized approaches. Structured motor development, adapted exercise testing, age-appropriate periodization, and a delayed specialization model collectively promote both performance and athlete well-being. The integration of visual maturity assessment, load monitoring, and skill variability frameworks enables practitioners to respond proactively to developmental changes rather than retroactively to injury or burnout.

From a practical standpoint, the application of maturity-based strategies allows coaches and support teams to personalize training intensity, skill emphasis, and testing benchmarks. For instance, the use of field-based aerobic or neuromuscular tests adapted to PHV status ensures valid tracking of progress, while reducing psychological or physiological overload. Similarly, embracing motor variability and implicit feedback techniques during technical training nurtures long-term skill adaptability - a crucial factor in open-skill sports such as football or basketball. Periodized load planning and structured recovery protocols, when synchronized with growth spurts, reduce overuse injury risk and support sustained development across adolescence.

At the structural level, the findings reinforce the importance of delaying single-sport specialization in favor of a multilateral development pathway. Data from talent development models and real-world athlete case profiles suggest that diversified training during the pre- and mid-pubertal phases builds a foundation for higher performance and retention in late adolescence. This model not only reduces dropout and injury rates, but also improves motor learning transfer and psychological engagement.

Despite these insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. The generalizability of models across sports with divergent demands (e.g., gymnastics vs. football) may vary, and biological maturity assessments (e.g., Mirwald method) present some margin of error. Furthermore, while this review emphasizes structured and adaptive training strategies, empirical data on long-term outcomes from such models remains limited, particularly across less-studied populations or in applied club-level settings.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies that integrate biological, psychological, and performance outcomes in youth athletes across multiple sports. Additionally, there is a growing need to validate visual and non-invasive maturity monitoring tools, as well as to explore digital technologies (e.g., wearables, AI-driven dashboards) for early detection of fatigue and injury risk during key developmental phases. Understanding how psychosocial dynamics interact with biological timing - especially regarding motivation, self-efficacy, and coach-athlete relationships - could further enhance the design of individualized training trajectories.

In summary, adopting a maturation-informed, multisystem approach to youth athletic development provides a foundation for both performance enhancement and athlete longevity. Coaches, educators, and sport scientists are encouraged to translate these principles into practice, supporting a generation of athletes equipped to thrive not only in elite pathways but also in lifelong sport participation.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This article synthesizes current knowledge on biologically informed approaches to youth athlete development, emphasizing that effective training, testing, and skill acquisition must align with the athlete’s growth stage, maturation status, and psychological readiness. The integration of maturity-based testing protocols, developmentally appropriate periodization, and diversified skill development models offers a practical framework for sustained athletic growth.

Youth athletes are not simply “miniature adults” - they exhibit unique physiological, biomechanical, and cognitive characteristics that evolve rapidly during adolescence. Addressing these developmental changes through evidence-based strategies reduces injury risk, enhances performance trajectories, and sustains long-term motivation.

A key message from this review is the importance of training flexibility, particularly during peak height velocity periods. Coaches and practitioners should adapt methodologies based not on chronological age, but on individual biological and developmental profiles. Furthermore, delaying early specialization in favor of multilateral development provides a broader foundation for motor competencies and psychological engagement, fostering elite potential and lifelong sport participation.

In addition to recommendations for coaches and trainers, parents significantly support healthy and sustainable athletic development. Encouraging diverse sports participation during childhood builds foundational motor skills and prevents early burnout. Prioritizing enjoyment, intrinsic motivation, and balanced lifestyle practices over immediate competitive results is essential. Open communication between parents and coaches regarding training objectives, monitoring strategies, and developmental needs is critical. Young athletes themselves should actively engage in goal-setting and balance training with proper recovery practices.

Socio-cultural and economic factors notably influence youth sports specialization. Socio-economic status affects access to facilities, coaching expertise, and participation opportunities, prompting earlier specialization or restricting diversified sports experiences. Cultural expectations and social norms around sports participation and success further influence youth specialization choices. These insights underscore the need for sports policies and educational programs that promote equitable access, adequate resources, and informed coaching practices. Educational institutions should adopt inclusive sport participation models that recognize developmental needs and emphasize balanced, long-term athlete development.

Collectively implementing these recommendations supports a comprehensive approach to youth athlete development, providing immediate performance benefits and encouraging sustainable athletic engagement.

Future youth sport development programs should embrace an interdisciplinary approach—integrating physiological monitoring, skill development strategies, psychological well-being, and responsible digital innovation—to guide young athletes safely toward high performance and sustained health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.H., C.H., and D.C.M.; methodology, S.S.H., C.H. and D.C.M; validation, S.S.H., C.H. and D.C.M.; formal analysis, S.S.H, C.H., and D.C.M.; investigation, S.S.H., C.H. and D.C.M..; resources, S.S.H., C.H., and D.C.M.; data curation, S.S.H, C.H., D.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.H., C.H., and D.C.M.; writing—review and editing, S.S.H., C.H., and D.C.M.; visualization, S.S.H., C.H., and D.C.M; supervision, S.S.H., C.H., and D.C.M.; project administration, S.S.H., C.H., and D.C.M. All authors have equal contributions, have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

References

- Brenner, J.S. Sports specialization and intensive training in young athletes. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162148. [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, M.F.; Mountjoy, M.; Armstrong, N.; et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on youth athletic development. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 843–851. [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C. Elements of the specific conditioning in football at university level. Marathon 2015, 7(1), 107-111.

- DiFiori, J.P.; Benjamin, H.J.; Brenner, J.S.; et al. Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2014, 24, 3–20. [CrossRef]

- Myer, G.D.; Jayanthi, N.; DiFiori, J.P.; et al. Sports specialization, part I: Does early sports specialization increase negative outcomes and reduce the opportunity for success in young athletes? Sports Health 2015, 7, 437–442. [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C. Fundamente teoretice ale activității fizice. 2013, Editura ASE.

- Malina, R.M.; Bouchard, C.; Bar-Or, O. Growth, Maturation, and Physical Activity, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2004.

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L. The youth physical development model. Strength Cond. J. 2012, 34, 61–72. [CrossRef]

- Manescu, D.C. Solutions to fight against overtraining in bodybuilding routine. Marathon 2013, 5(2), 182- 186.

- Mirwald, R.L.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G.; Bailey, D.A.; Beunen, G.P. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 689–694. [CrossRef]

- Manescu, D.C. Alimentaţia în fitness şi bodybuilding. 2010, Editura ASE.

- Beunen, G.; Malina, R.M. Growth and biologic maturation: Relevance to athletic performance. In The Young Athlete; Hebestreit, H., Bar-Or, O., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 3–17.

- Lloyd, R.S.; Cronin, J.B.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; et al. National Strength and Conditioning Association position statement on long-term athletic development. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1491–1509. [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C.; Mănescu, A.M. Artificial Intelligence in the Selection of Top-Performing Athletes for Team Sports: A Proof-of-Concept Predictive Modeling Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9918. [CrossRef]

- Ford, P.R.; De Ste Croix, M.; Lloyd, R.; et al. The long-term athlete development model: Physiological evidence and application. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 389–402. [CrossRef]

- Côté, J.; Vierimaa, M. The developmental model of sport participation: 15 years after its first conceptualization. Sci. Sports 2014, 29, S63–S69. [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C. Computational Analysis of Neuromuscular Adaptations to Strength and Plyometric Training: An Integrated Modeling Study. Sports 2025, 13, 298. [CrossRef]

- Malina, R.M.; Kozieł, S.M. Validation of maturity offset in a longitudinal sample of Polish boys. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 424–437. [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.; MacNamara, Á.; McCarthy, N. Putting the bumps in the rocky road: Optimizing the pathway to excellence. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1482. [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, A.M.; Grigoroiu, C.; Smîdu, N.; Dinciu, C.C.; Mărgărit, I.R.; Iacobini, A.; Mănescu, D.C. Biomechanical Effects of Lower Limb Asymmetry During Running: An OpenSim Computational Study. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1348. [CrossRef]

- Rowland, T.W. Developmental Exercise Physiology, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2005.

- Armstrong, N.; McManus, A.M. Physiology of elite young male athletes. Med. Sport Sci. 2011, 56, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Baquet, G.; Berthoin, S.; Dupont, G.; Blondel, N.; Fabre, C.; Van Praagh, E. Effects of high-intensity intermittent training on peak VO₂ in prepubertal children. Int. J. Sports Med. 2002, 23, 439–444. [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C. Big Data Analytics Framework for Decision-Making in Sports Performance Optimization. Data 2025, 10, 116. [CrossRef]

- Philippaerts, R.M.; Vaeyens, R.; Janssens, M.; et al. The relationship between peak height velocity and physical performance in youth soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Meylan, C.M.; Cronin, J.B.; Oliver, J.L.; Hughes, M.G. Talent identification in soccer: The role of maturity status on physical, physiological and technical characteristics. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2010, 5, 571–592. [CrossRef]

- Manescu, D.C. Noțiuni complementare ale antrenamentului sportiv. 2025, Editura Risoprint.

- Myer, G.D.; Ford, K.R.; Brent, J.L.; Hewett, T.E. Reliability and validity of a modified drop vertical jump assessment. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 1975–1983.

- Manescu, D.C. Bazele generale ale antrenamentului sportiv. 2025, Editura Risoprint. https://www.risoprint.ro/detaliicarte.php?id=2515.

- Lloyd, R.S.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Stone, M.H.; et al. Position statement on youth resistance training: The 2014 International Consensus. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 498–505. [CrossRef]

- Manescu, D.C. Nutriție ergogenă, suplimentație și performanță. 2025, Editura Risoprint. https://www.risoprint.ro/detaliicarte.php?id=2522.

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; et al. Long-term athletic development, part 1: A pathway for all youth. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 1439–1450. [CrossRef]

- Malina, R.M.; Beunen, G.P. Maturity-associated variation in adolescent physical performance. Sports Med. 1996, 22, 65–89. [CrossRef]

- Manescu, D.C. Powerlifting. 2025, Editura Risoprint. https://www.risoprint.ro/detaliicarte.php?id=2525.

- Oliver, J.L.; Lloyd, R.S.; Rumpf, M.C.; et al. Developing speed and agility in youth: The role of maturation and training. Strength Cond. J. 2013, 35, 42–48.

- Manescu, D.C. Fotbal – Știința performanței. 2025, Editura Risoprint. https://www.risoprint.ro/detaliicarte.php?id=2524.

- Halson, S.L. Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports Med. 2014, 44 (Suppl 2), S139–S147. [CrossRef]

- Manescu, D.C. Fitness. 2025, Editura Risoprint. https://www.risoprint.ro/detaliicarte.php?id=2521.

- Jayanthi, N.A.; Pinkham, C.; Dugas, L.; Patrick, B.; LaBella, C. Sports specialization in young athletes: Evidence-based recommendations. Sports Health 2013, 5, 251–257. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Lai, S.K.; Veldman, S.L.; et al. Correlates of gross motor competence in children and adolescents. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1663–1686. [CrossRef]

- Manescu, D.C. Bodybuilidng. 2025, Editura Risoprint. https://www.risoprint.ro/detaliicarte.php?id=2517.

- Robinson, L.E.; Stodden, D.F.; Barnett, L.M.; et al. Motor competence and its effect on positive developmental trajectories of health. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1273–1284. [CrossRef]

- Vaeyens, R.; Lenoir, M.; Williams, A.M.; Philippaerts, R.M. Talent identification and development programmes in sport: Current models and future directions. Sports Med. 2008, 38, 703–714. [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, R.; Newell, K.M. Emergent flexibility in motor learning. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 583–590. [CrossRef]

- Côté, J.; Lidor, R.; Hackfort, D. ISSP position stand: To sample or to specialize? Seven postulates about youth sport activities that lead to continued participation and elite performance. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 7, 7–17. [CrossRef]

- Law, M.P.; Côté, J.; Ericsson, K.A. Characteristics of expert development in rhythmic gymnastics: A retrospective study. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 5, 82–103. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Timeline depicting the typical peak height velocity (PHV) age ranges for boys and girls, highlighting periods of increased injury risk and decreased neuromuscular control. Coaches should apply cautious and adaptive training strategies within the highlighted "Training Caution Zone" (ages 10–14).

Figure 1.

Timeline depicting the typical peak height velocity (PHV) age ranges for boys and girls, highlighting periods of increased injury risk and decreased neuromuscular control. Coaches should apply cautious and adaptive training strategies within the highlighted "Training Caution Zone" (ages 10–14).

Figure 2.

Sex-specific maturation timelines highlighting Peak Height Velocity (PHV) and associated periods of increased injury risk during adolescence. Explicitly, girls typically reach PHV earlier (ages 10–12) with heightened risk of ACL and patellofemoral injuries, whereas boys experience PHV slightly later (ages 12–14) and are more susceptible to conditions such as Osgood-Schlatter disease. Recommendations emphasize tailored neuromuscular interventions, careful load management, and avoiding high-impact assessments during peak growth periods.

Figure 2.

Sex-specific maturation timelines highlighting Peak Height Velocity (PHV) and associated periods of increased injury risk during adolescence. Explicitly, girls typically reach PHV earlier (ages 10–12) with heightened risk of ACL and patellofemoral injuries, whereas boys experience PHV slightly later (ages 12–14) and are more susceptible to conditions such as Osgood-Schlatter disease. Recommendations emphasize tailored neuromuscular interventions, careful load management, and avoiding high-impact assessments during peak growth periods.

Figure 3.

Decision-making flowchart for selecting age- and maturity-appropriate exercise tests in youth athletes. The process begins by determining biological maturity (pre-, during-, or post-PHV), followed by the selection of aerobic, neuromuscular, or functional screening tests. The final decision aligns test protocols with the athlete’s developmental stage to ensure safe, valid, and actionable assessments.

Figure 3.

Decision-making flowchart for selecting age- and maturity-appropriate exercise tests in youth athletes. The process begins by determining biological maturity (pre-, during-, or post-PHV), followed by the selection of aerobic, neuromuscular, or functional screening tests. The final decision aligns test protocols with the athlete’s developmental stage to ensure safe, valid, and actionable assessments.

Figure 4.

Integrated athlete monitoring dashboard illustrating how biological maturity (growth velocity), training load (external and internal), testing performance (CMJ and sprint speed), and injury risk flags can be aligned across a youth athlete’s seasonal timeline. This visualization reinforces the need for individualized monitoring strategies that account for PHV-related vulnerabilities and training adaptations.

Figure 4.

Integrated athlete monitoring dashboard illustrating how biological maturity (growth velocity), training load (external and internal), testing performance (CMJ and sprint speed), and injury risk flags can be aligned across a youth athlete’s seasonal timeline. This visualization reinforces the need for individualized monitoring strategies that account for PHV-related vulnerabilities and training adaptations.

Figure 5.

Periodized training framework based on maturation stage. Pre-PHV training emphasizes internal load and skill development; PHV introduces mixed loads and injury-conscious programming; Post-PHV enables external load progression focused on strength, power, and tactical refinement.

Figure 5.

Periodized training framework based on maturation stage. Pre-PHV training emphasizes internal load and skill development; PHV introduces mixed loads and injury-conscious programming; Post-PHV enables external load progression focused on strength, power, and tactical refinement.

Figure 6.

Alignment of training load strategies with biological maturation stages. The figure highlights the recommended emphasis on internal loads and fundamental skills before Peak Height Velocity (Pre-PHV), the importance of mixed loads focused on injury prevention and coordination during Peak Height Velocity (PHV), and the progression to external loads targeting strength, power, and technical refinement after PHV (Post-PHV).

Figure 6.

Alignment of training load strategies with biological maturation stages. The figure highlights the recommended emphasis on internal loads and fundamental skills before Peak Height Velocity (Pre-PHV), the importance of mixed loads focused on injury prevention and coordination during Peak Height Velocity (PHV), and the progression to external loads targeting strength, power, and technical refinement after PHV (Post-PHV).

Figure 7.

Progressive motor skill development across biological maturation stages in youth. The timeline illustrates the transition from fundamental motor skills in the pre-PHV stage (~6–9 years), through coordination-focused training during the PHV window (~10–14 years), to advanced, sport-specific skill refinement post-PHV (14+ years). The model emphasizes movement adaptability, stage-appropriate feedback strategies, and the integration of both closed and open-skill development for long-term athletic potential.

Figure 7.

Progressive motor skill development across biological maturation stages in youth. The timeline illustrates the transition from fundamental motor skills in the pre-PHV stage (~6–9 years), through coordination-focused training during the PHV window (~10–14 years), to advanced, sport-specific skill refinement post-PHV (14+ years). The model emphasizes movement adaptability, stage-appropriate feedback strategies, and the integration of both closed and open-skill development for long-term athletic potential.

Figure 8.

Comparative overview of early specialization and multilateral development models in youth sports. Early specialization is characterized by intense, single-sport focus from a young age, often leading to short-term performance gains but increased injury risk and reduced long-term adaptability. In contrast, multilateral development involves diverse sport participation, fostering broader motor skill acquisition, reduced overuse injuries, and improved long-term athletic outcomes.

Figure 8.

Comparative overview of early specialization and multilateral development models in youth sports. Early specialization is characterized by intense, single-sport focus from a young age, often leading to short-term performance gains but increased injury risk and reduced long-term adaptability. In contrast, multilateral development involves diverse sport participation, fostering broader motor skill acquisition, reduced overuse injuries, and improved long-term athletic outcomes.

Table 1.

Key developmental differences between early and late maturers, with implications for training load management, injury prevention, and talent identification in youth athletes.

Table 1.

Key developmental differences between early and late maturers, with implications for training load management, injury prevention, and talent identification in youth athletes.

| Characteristic |

Early Maturers |

Late Maturers |

| Growth Spurt Timing |

Before peers

(~10–12 y/o) |

After peers

(~12–14 y/o) |

| Muscle Mass Gain |

Earlier

and more pronounced |

Delayed

but sustained |

| Strength & Power |

Temporary

advantage |

Temporary

disadvantage |

| Injury Risk During PHV |

Moderate–High |

High

during rapid growth phase |

| Talent Identification Bias |

Often favored

in youth selection |

Often overlooked |

| Psychosocial Maturity |

Varies;

may face high pressure early |

Resilient,

motivated |

| Long-Term Performance Potential |

Not always sustained |

Often higher in adulthood |

Table 2.

Sport-specific testing recommendations for youth athletes before and after peak height velocity (PHV).

Table 2.

Sport-specific testing recommendations for youth athletes before and after peak height velocity (PHV).

| Sport |

Recommended Tests

(Pre-PHV) |

Recommended Tests

(During/Post-PHV) |

| Football |

Multi-Stage Fitness Test,

T-test agility,

Vertical Jump |

Yo-Yo IR1,

Sprint Tests (10–30 m),

FMS, CMJ |

| Basketball |

Beep Test,

5-10-5 Shuttle,

Standing Long Jump |

Sprint Agility Tests,

Jump Tests (CMJ, SJ),

LESS, FMS |

| Gymnastics |

Flexibility assessment,

Static Balance,

Core Endurance |

Dynamic Strength (Plank Hold), Movement Screening,

Landing Mechanics |

| Swimming |

25 m Swim Time Trials,

Push-off Power,

Kick Efficiency |

VO₂ Swim Test,

Repeated Sprint Swim Test,

Start Reaction Time |

| Tennis |

Agility Ladder,

Medicine Ball Throw,

Hand-Eye Coordination |

Serve Velocity,

Lateral Movement Test,

Anaerobic Intervals |

Table 3.

Overview of typical injury patterns, underlying risk factors, and developmentally appropriate performance assessments for youth athletes across major sports during periods of growth and maturation.

Table 3.

Overview of typical injury patterns, underlying risk factors, and developmentally appropriate performance assessments for youth athletes across major sports during periods of growth and maturation.

Sport &

Typical

PHV Age

|

Common Injuries

During PHV |

Contributing Factors |

Recommended Tests

(Pre-PHV) |

Recommended Tests

(During/Post-PHV) |

Football

Boys: 12–14

Girls: 10–12 |

Osgood-Schlatter, Sever’s disease, hamstring strains, ankle sprains, growth plate injuries |

Rapid growth, increased training load,

neuromuscular imbalance |

Beep/Multi-Stage Fitness Test,

T-test agility, Standing Long Jump |

Yo-Yo IR1,

Sprint

(10–30m),

FMS, CMJ,

LESS |

Basketball

Boys: 12–14

Girls: 10–12 |

Patellofemoral pain,

ankle sprain,

stress fractures, Osgood-Schlatter |

Jumping/landing frequency, coordination deficits, high growth velocity |

Shuttle Run,

Vertical Jump, Balance Testing |

Sprint Agility,

Jump Tests

(CMJ, SJ),

LESS, FMS |

Gymnastics

Girls: 10–12 |

Wrist pain,

stress fracture,

ACL injury, spondylolysis |

Early specialization, repetitive loading, flexibility demands |

Flexibility,

Static Balance,

Core Endurance |

Plank Hold, Movement Screening,

Landing Mechanics |

Swimming

Boys: 12–14

Girls: 10–12 |

Shoulder impingement, lumbar pain, apophysitis |

Repetitive

overhead movement,

poor technique, growth spurts |

25m

Time Trials,

Push-off

Power, Kick Efficiency |

VO₂

Swim Test, Repeated Sprint, Start Reaction

Time |

Tennis

Boys: 12–14

Girls: 10–12 |

Little League elbow, rotator cuff tendinopathy,

back pain |

Repetitive strokes, single-sided loading,

early specialization |

Agility Ladder, Medicine Ball Throw, Hand-Eye Coordination |

Serve Velocity, Lateral Movement Test,

Anaerobic Intervals |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).