1. Background

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are a group of neurodevelopmental disorders defined as qualitative impairments in social functioning and communication. Diagnostic criteria are set out in the ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases, 11th revision) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V). The ICD-11 classification distinguishes seven groups of disorders, i.e. disorders of intellectual development, developmental speech and language disorders, autism spectrum disorders, developmental learning disorders, developmental motor coordination disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and stereotyped movement disorder [

1]. According to the DSM-V (2013) classification, a person diagnosed with autism must exhibit at least 6 of the features listed, including (1) at least two from clinically significant, persistent abnormalities in social communication and interaction: marked deficits in verbal and nonverbal communication used in social interaction, lack of social reciprocity, inability to develop and maintain peer relationships appropriate for the level of development, and (2) one from restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, and activities manifested by at least two of the following symptoms: stereotyped motor/verbal behaviours or atypical sensory behaviours, excessive attachment to routines and ritualized patterns of behaviour, restricted interests. Symptoms must be present in early childhood (but may not become fully manifest until societal demands exceed the child’s limited abilities). ASD is mostly diagnosed between 3rd and 6th year of life. Undoubtedly, early diagnosis leads to earlier behaviour-based intervention. Regardless of the classification system, the diagnosis of ASD is based on the identification of symptoms such as significant limitations in the ability to create relationships with people and participate in social interactions, abnormalities in verbal and non-verbal communication, limited, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour, interests, and activities.

Due to the growing number of ASD cases, scientists are still investigating the causes and mechanisms, however, the aetiology of this group of disorders has not been clearly established, which proves its complex and multifactorial character. There are a number of hypotheses that describe the mechanisms of these disorders. It is assumed that genetic, developmental, infectious, and pregnancy- and childbirth-related factors, maternal age, aside environmental stress, medications, pollutants might be responsible for the development of ASD phenotype.

Etiological heterogeneity makes establishing definitive diagnosis difficult. Most commonly studied molecular biomarkers are cytokines, growth factors, oxidative stress measurements, neurotransmitters, and hormones, followed by neurophysiological studies (e.g. electroencephalography), functional neuroimaging (e.g. fMRI), and other physiological assessments. In April 2020, a systematic review of MEDLINE, Embase, and Scopus database analyzed reports on the correlation between 940 different biomarkers and behavioral assessment of ASD [

20].

SHANK Proteins in the Postsynaptic Density (PSD)

Neurodevelopmental disorders, such as ASD, intellectual disability (ID), and schizophrenia (SCZ) caused by deletion or mutations of the

SHANK/ProSAP genes are sometimes termed ‘

shankopathies’. SHANK proteins (

SH3 domain and ankyrin repeat-containing protein), also called ProSAP (proline rich synapse-associated protein), are the main anchoring proteins located in the postsynaptic density at the terminals of glutamatergic synapses, encoded by three genes:

SHANK1, SHANK2, and

SHANK3 [

17].

SHANK proteins may play various roles in synaptic pathogenesis and maturation. Their levels in the PSD are strictly regulated by the level of Zn

2+ ions in an isoform-dependent manner. SHANK2 and SHANK3 are sensitive to Zn

2+ ions via their SAM domains, whereas SHANK1 is insensitive to Zn

2+. Immature synapses display a striking sensitivity to extracellular levels of Zn

2+ ions that mature synapses do not. This sensitivity is closely related to the various expression and selective binding of Zn

2+ ions to SHANK2 and SHANK3, but not SHANK1. SHANK proteins are sequentially recruited to postsynaptic sites during different stages of hippocampal tissue culture. SHANK2 was the first to appear in the PSD at all synapses, whereas SHANK1 was identified in only one third of all synapses at day 7 of culture. The presence of all three SHANK family proteins was confirmed on day 21 of culture in 95% of all synapses [

25].

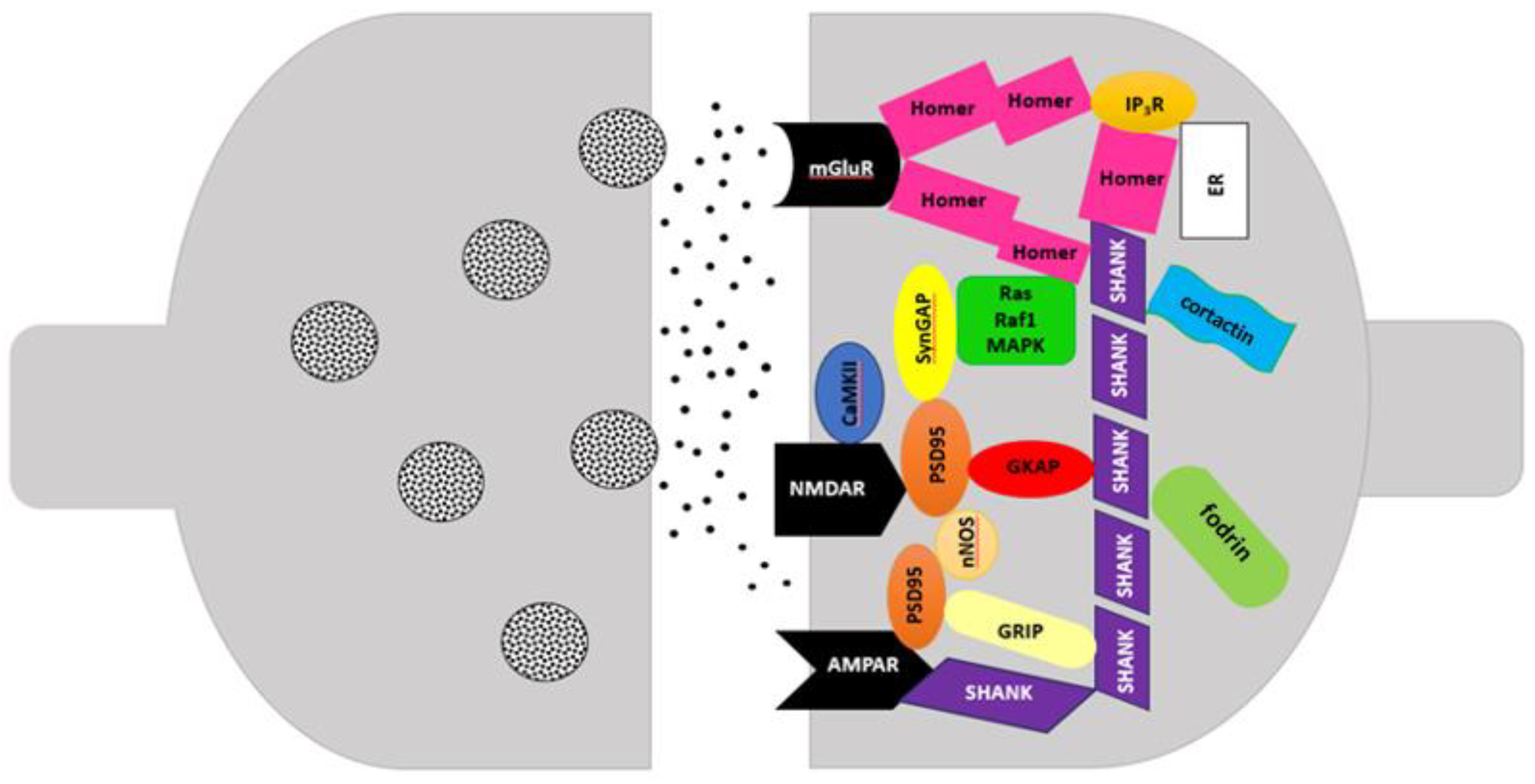

SHANK proteins coded by

SHANK1 gene (19q13.33),

SHANK2 gene (11q13.3), and

SHANK3 gene (22q13.3) participate in glutamate signaling through the assembly of glutamate receptors with other anchoring proteins, cytoskeletal elements and adhesion molecules. Multimerization of SHANK1, SHANK2, SHANK3 proteins can generate a network that attaches many proteins to postsynaptic receptors. Moreover, SHANK proteins promote the formation, maturation and elongation of dendrites [

24]. They are involved in various functions including neuronal morphogenesis, synapse formation, glutamate receptor transport, and neuronal signaling [

22]. Improper functioning of SHANK proteins can yield a wide spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders where the presence of various variants of the

SHANK genes has been detected [

10]. The structure of excitatory synapses and the number of glutamatergic AMPA (

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid) and NMDA (

N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptors have a significant impact on the communication between nerve cells. Any changes in the structure of PSD may contribute to the development of various neurodevelopmental disorders as PSD proteins ensure efficient transmission of nerve impulses [

6,

14,

24].

Another PSD protein is SHARPIN, localized in the cytoplasm, cytosol and synapses. Its higher amounts are detected in mature neurons, where it occurs alongside the SHANK1 protein.

SHARPIN (8q24.3) encodes proteins interacting with the RH domain, and is a component of the linear ubiquitin chain activation complex [

31]. SHARPIN protein forms a complex with SHANK in heterologous cells and brain. The C-terminal half of SHARPIN interacts with SHANK and its N-terminal half mediates homomultimerization. Alternative splicing can truncate the ankyrin repeats and the SH3 domain of SHANK which can suggest regulatory function of the Shank-based protein network [

13].

Figure 1.

Postsynaptic density (PSD) (based on Soler et al., 2018).

Figure 1.

Postsynaptic density (PSD) (based on Soler et al., 2018).

The objective of study was to review literature on the role of SHANK proteins in developing ASD. Considering the results of numerous scientific reports we analyzed the expression of the SHANK1, SHANK2, SHANK3, and SHARPIN genes based on the assumption that peripheral venous blood may provide an alternative research tool in the search for diagnostic biomarkers of ASD. We assessed the expression of the SHANK gene family and SHARPIN in the peripheral venous blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in the examined population.

2. Material and Methods

The research material included samples of peripheral venous blood collected from pediatric patients with ASD (Genetic Clinic, Independent Public Clinical Hospital No.4, Lublin, Poland) and peripheral venous blood from children without ASD (Medical Laboratory Diagnostyka Ltd., University Children’s Hospital in Lublin, Poland). The research was approved by the Bioethical Committee, Medical University of Lublin, Poland (decision no. KE-0254/175/2019 and KE-0254/133/2021). Consent was also obtained from parents of the children with and without ASD for the use of biological material for research purposes.

The study group consisted of 29 patients (aged 2-14 years) with ASD, 20 boys and 9 girls. The control group consisted of 29 children at the same age without ASD. The inclusion of patients with ASD was based on pediatric diagnosis.

The level of gene expression was assessed in peripheral venous blood mononuclear cells. Peripheral venous blood from minors with ASD and minors without ASD was collected into test tubes containing EDTA. Isolation of peripheral venous blood mononuclear cells was performed using Gradisol L (Dembińska-Kieć and Naskalski, 2009) by density gradient centrifugation at room temperature, first at 2600 rpm for 30 minutes, then at 2000 rpm for10 min. (Centrifuge 5810R). The isolates containing mononuclear cells in the form of pellets deposited at the bottom of a sterile polypropylene Eppendorf tubes were then frozen (-80°C) to protect the material for RNA isolation. Isolation of total RNA was performed according to the modified method of Chomczyński-Sacci (1987).

To separate DNA from RNA and extract protein impurities, 0.1 ml of chloroform (POCH Basic S.A.) was added to the test tubes, shaken manually, and left for 15 minutes at room temperature). Samples were centrifuged at 13,600 rpm, 4oC for 15 minutes (Centrifuge 5415R). The aqueous phase containing RNA was transferred using an automatic pipette, and 0.25 ml of isopropyl alcohol (POCH Basic S.A.) was added to precipitate the RNA from the solution. The samples were mixed gently and left at room temperature for 20 min., then centrifuged at 13,600 rpm at 4°C for 20 minutes (Centrifuge 5415R, Eppendorf). After removing the supernatant, 0.25ml of 80% cold (-20oC) ethyl alcohol solution was added to the precipitated pellet. Samples were stored at -20°C until further analysis. Spectrophotometric analysis was subsequently performed using NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). The cell suspension (2 µl) was subjected to quantitative and qualitative assessment.

The amount of RNA was measured as the absorbance value at a wavelength of 260 nm. Samples with an absorbance ratio A260/A280 in the range of 1.8-2.0 were subjected to reverse transcription, which indicated their purity. After qualitative and quantitative assessment of the isolated RNA, the reaction mixture was prepared using the High-Capacity cDNA Transcription Kit reagents according to the manufacturer’s protocol (High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit Applied Biosystems™, ThermoFisher Scientific). The entire procedure was performed under a laminar chamber on ice.

Gene expression was assessed using real-time PCR using dedicated probes according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ThermoFisher Scientific). The production of PCR products was read from the fluorescence signal emitted by the probes.

ThermoFisher and Statistica v. 13 software was used to statistically analyze the results, which ensured the reliability of data. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare independent groups to determine statistically significant differences between the tested parameters. The dependences between the expression levels of examined genes were evaluated using the Spearman rank correlation test.

4. Discussion

The development of genetic research conducted over the last 30 years has provided a number of evidence confirming changes in the genome in people with ASD. In 2017 whole-genome sequencing of ASD families was carried out to determine phenotypes and underlying genetic factors. The researchers sequenced 5,205 samples from ASD families and correlated the results with clinical signs and symptoms. The study confirmed an average of 73.8

de novo SNVs and 12.6

de novo insertions, deletions and copy number changes in people with ASD. The results demonstrated that people with mutations in the susceptibility genes presented significantly lower adaptive capacity (P = 6 × 10-4). In 294 of 2620 (11.2%) ASD cases, a molecular basis could be determined, and 7.2% of these contained copy number changes and/or chromosomal abnormalities. Studies have highlighted the importance of detecting all forms of genetic variation as diagnostic and therapeutic targets in ASD [

12]. Chromosomal rearrangements, submicroscopic deletions, duplications, CNVs, pathogenic

de novo mutations, or SNPs indicate the genetic background [

5]. In total, mutations in over 1,000 genes have been detected in ASD patients [

17]. It is currently accepted that the genetic risk of developing ASD can be attributed to many common gene variants with a frequency >1%, i. e. SNPs, each of which carries a moderate level of risk (odds ratio = 1.1–1.5) or rare mutations with a frequency <1%: SNVs and CNVs, usually associated with a greater penetrance of the phenotype (odds ratio >2) [

24].

Among the ASD risk genes, the

SHANK family genes are increasingly studied due to their role in the formation of synaptic connections. The results of studies on animal models of SHANK family proteins indicate an growing number of genetic links between mutations in

SHANK, including the protein products encoded by them, and the development of ASD [

16]. Animal studies confirm that mice with different mutations in

SHANK1,

SHANK2, and

SHANK3 genes have some distinct and common phenotypes at the molecular and functional level. All mutants seem to have an altered molecular composition of excitatory synapses and altered neurotransmission, and often show impaired social interaction and repetitive behaviors [

28].

Genetic studies of ASD indicate disturbed synthesis and function of synaptic scaffolding proteins. In the case of developmental ‘

synaptopathies’, researchers postulate two pathological mechanisms: impaired regulation of transcription, translation and quality control of synthesized proteins, and disturbed structure of synaptic scaffolding proteins and receptor channels. The first of these mechanisms occurs in fragile X chromosome syndrome (FXS), (loss of

FMRP target mRNA repression in dendrites), tuberous sclerosis complex (

TSC1 or

TSC2 mutations lead to deregulated mTOR-dependent translation, and Angelman syndrome (loss of Ube3a- dependent ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation). The other mechanism occurs in Phelan-McDermid syndrome, caused by disruption of the postsynaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3, which is a critical link between glutamate receptors and signaling pathways that build scaffolding proteins and actin cytoskeleton in the postsynaptic density (PSD) [

7].

Numerous CNVs of several genes regulating synaptogenesis and signaling pathways are pivotal in the pathogenesis of ASD. The complexity of CNV causes mutations in genes encoding molecules involved in cell adhesion, ion channels, anchoring proteins, as well as PTEN/mTOR (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten/mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathways. Mutated genes affect synaptic transmission, causing dysfunction of synaptic plasticity, which in turn is responsible for the development of ASD phenotype. Moreover,

de novo mutations also constitute another important group of causative factors in ASD [

26]. Among the mechanisms associated with ASD, “

channelopathies” found in Timothy syndrome indicate that variability and mutations in genes encoding ion channels (Ca

2+ , K

+, Na

+ and Cl

− channels) are the leading risk factor for ASD [

1]. Epigenetic modifications affecting DNA transcription and prenatal and postnatal exposure to various environmental factors may also contribute to the development of ASD. Deregulated glutamatergic signaling as well as imbalance in the excitatory/inhibitory pathways activates glial cells and release of inflammatory mediators responsible for the abnormal social behaviors observed in patients with ASD [

4].

Considering the role of PSD anchor proteins, i.e. control of information transfer in intracellular networks and regulatory involvement in dendrite formation and function, scientists have postulated that variants in the genes encoding these proteins are associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Defective proteins can lead to synaptic dysfunction in ASD [

7]. Numerous evidence confirming biological links of gene mutations encoding SHANK proteins with ASD allow for a deeper insight into the etiology of these disorders and their diagnosis and treatment [

6].

Studies have found that

SHANK1, SHANK2, and

SHANK3 genes can encode several mRNA splice variants, generating multiple protein isoforms whose expression is detected in the tissue of different brain regions [

2,

15,

22,

24]. After the first publication discussing the

SHANK3 variant in patients with ASD [

27], subsequent studies confirmed a close relationship between

SHANK variants and ASD and intellectual disability [

8].

SHANK1 mRNA was found in the hippocampal cortex, amygdala, Purkinje cells, and the hypothalamus.

SHANK1 and

SHANK3 mRNA was detected in the molecular layer of the hippocampus.

SHANK2 mRNA expression was confirmed in the hippocampus, striatum, cerebral cortex, olfactory bulb, cerebellum, and Purkinje cells.

SHANK1, SHANK2, SHANK3 mRNA expression was observed in the neuropil layer of the CA1 region of the hippocampus: the highest dendritic expression was

SHANK1 mRNA, followed by

SHANK3 mRNA and

SHANK2 mRNA [

9].

To determine epigenetic influence, DNA methylation in

SHANK genes has been studied in the lymphocytes, cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and heart tissue. Seven CpG islands in the

SHANK1 and

SHANK2 genes and five in the

SHANK3 genes were examined for methylation. Most CpG islands in

SHANK1 and

SHANK2 showed high methylation variability with no apparent tissue specificity. On the other hand,

SHANK3 showed tissue-specific methylation on most of its CpG islands and high levels of methylation in tissues where its expression was low or absent, suggesting that

SHANK3 expression may be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms [

3].

To date, most SNVs in

SHANK1 have been associated with ASD. The tests did not detect

SHANK1 duplication. Also, deletions in

SHANK1 have been associated with marked social dysfunctions [

24]. Studies in animal models have shown that

SHANK1 deletion may be associated with mild autism occurring only in males, but the gender association of

SHANK1 has to be confirmed [

11]. Animal studies were conducted to elucidate the role of SHANK proteins in brain development and synaptic function. Experimental mice were bred with mutant

SHANK1 genes obtained by the deletion of exons 14 and 15 leading to the loss of all

SHANK1 splice variants. A decrease in basal postsynaptic transmission, reduced expression of GKAP/SAPAP and Homer, particularly in the PSD fractions and reduced thickness of the PSD area at CA1 synapses were observed. Behaviorally,

SHANK1 mutant mice showed reduced sniffing during male-female interactions and fewer interactions with new mice compared to wild-type littermates [

17]. Interestingly, mice showed improved spatial memory despite impaired contextual fear memory and severely impaired object recognition memory. The results suggest that

SHANK1 plays a key role in memory retention [

19].

Once first

SHANK2 gene mutations were identified in patients with ASD and ID [

24], subsequent publications confirmed variants of missense mutations, gene deletions, and mutations in the

SHANK2 promoter regions. Various mutations of this gene and dysfunctional domains or shortened products lacking domains responsible for the interactions with other proteins may lead to increased or decreased protein expression. This, in turn, may alter protein-protein interactions and the organization of the postsynaptic protein network. Thus,

SHANK2 mutations can alter processes at the molecular and cellular levels in neurons, causing a wide spectrum of ASD behavioral phenotypes [

8]. Animal models have used independent mutant lines with a mutated

SHANK2 gene in exons 6 and 7 [

29] and exon 7 [

23], with both models lacking all

SHANK2 isoforms. Both studies showed similar development of proteins and synaptic plasticity. Basal synaptic transmission was reduced only in

SHANK2 mutant mice. Similar behavioral features resembling autism were observed, including excessive grooming, hyperactivity, reduced digging, altered ultrasonic vocalization, and impaired social interaction in both models. The results suggest that changes in NMDA function are critical in inducing behaviors characteristic of ASD [

23,

29].

SHANK3 protein is thought to be essential for the development of synaptic functions. Mutations in the

SHANK3 gene have been associated with many neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD. Research indicates that

SHANK3 mutations contribute to pathological changes. Scientists have identified two SNVs in the

SHANK3 gene in patients with schizophrenia, and various SNP variants, SNVs and CNVs have been associated with ASD. Among them, a missense variant

G1011V (g.49506159G>T) was identified in exon 21 in patients with schizophrenia and in patients with ASD [

24]. There were 1,179 missense variants identified, 29 of which were considered harmful and were subjected to structural and stability analysis. Mutations were modeled, including

L47P,

G54W,

G172D,

G250C/D, and

G627E, which had a drastic effect on the secondary structure of

SHANK3. Stability analysis confirmed

L47P,

G54W and

G250D as the most destabilizing mutations, so they were subjected to molecular dynamics simulation. The simulation revealed altered intramolecular interactions and large fluctuations in 1–350 residues which significantly affected the functional domain of ANK. Deleterious mutations

G250C/

D and

G635R were identified in the first and second binding domains of

SHANK3, but were not detected in sites of post-translational modifications. This study suggests that deleterious

L47P and

G54W mutations are priority targets for future research into the role of

SHANK3 [

18].

As one of PSD proteins, SHARPIN’s involvement was confirmed not only in the inflammatory response, but also as an inhibitor of integrins activator and a contributor to carcinogenesis and Alzheimer’s disease. Tests on an animal model found that SHARPIN regulates immune signaling and contributes to full transcriptional activity and the prevention of TNF-dependent cell apoptosis. These results provided unexpected information about the developmental significance of SHARPIN [

21].

Research into the development of diagnostic biomarkers for ASD is complicated due to the complex nature of ASD and diversity of phenotypes. The search for causes and characteristic biomarkers requires a series of studies and in-depth genome analysis. The discovery of a large number of candidate gene variants illustrates the genetic complexity of ASD. Molecular and imaging studies performed

post mortem on the brain tissue have a number of limitations, such as

post-mortem time, time of death and its cause, storage procedure and integrity of the biomaterial. Currently, alternative materials collected from patients, such as blood, fibroblasts and stem cells, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and feces are used for the analysis, which allows for deeper insight into the pathophysiology and establish reliable diagnostic biomarkers for ASD [

30].

Taking into account the results of numerous scientific reports indicating the involvement of genes from the SHANK family in the etiology of autism spectrum disorders we focused on the analysis of the SHANK1, SHANK2, SHANK3, and SHARPIN genes in the peripheral venous blood collected from ASD patients. A literature review of PubMed (06/02/2023) using the terms peripheral blood and SHANK1, SHANK2, SHANK3, and SHARPIN genes did not yield any publications discussing this issue. Our objective was to determine whether biomarkers based on the expression of the SHANK gene family and SHARPIN can be established from the peripheral venous blood mononuclear cells in the examined population.

In case of patients with ASD, especially children, the study material is very challenging. Very limited amounts of RNA can be extracted when only small/scarce amounts can be obtained,. Another hurdle is that sample material is sometimes obtained from a different tissue as where a disorder manifests itself most prominently, as in neurodevelopmental disorders and deficits. Also, the number of samples is often problematic. According to a standard sample size calculation, the numbers required may be impossible to reach. Thus, to obtain more samples or more (uniform) material than available from humans, frequently model systems or organisms are used, mostly cultured cell lines, or animal studies. The peripheral venous blood seems to be an easily accessible diagnostic tool, however it is not easy to gather a group of young patients with ASD. Blood sampling is an invasive procedure. Children often react with anger, anxiety and/or fear during the procedure and in contact with foreign surroundings of the treatment room and medical staff.

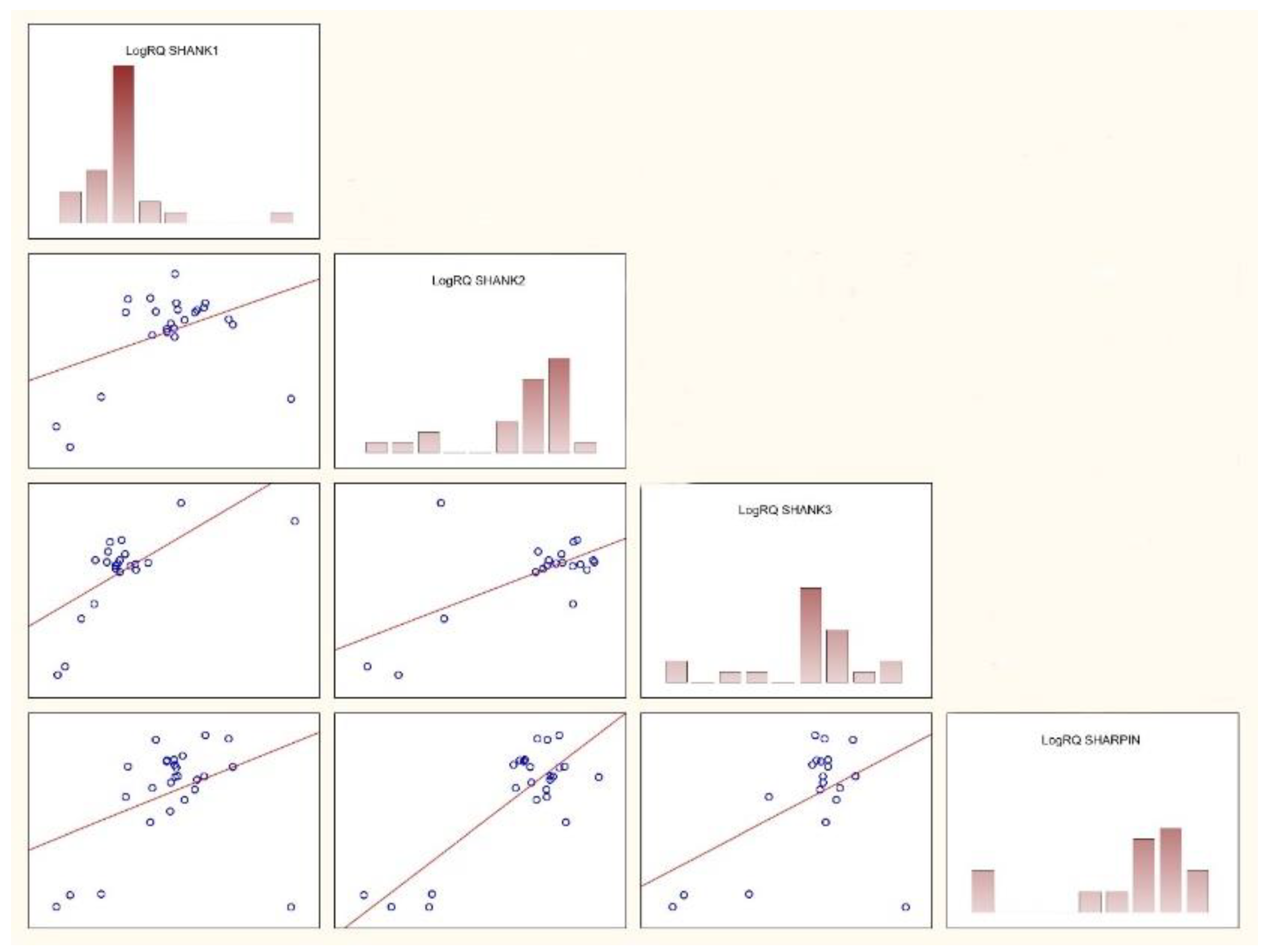

The presented research focused on the analysis of the expression of SHANK1, SHANK2, SHANK3, and SHARPIN genes isolated from the PBMCs in children with ASD and without ASD. The results showed on average low level of expression of the SHANK1, SHANK2, SHANK3, and SHARPIN genes in the studied groups. The analysis revealed only one statistical difference in the expression level of the SHANK1 gene compared to the SHANK2 which was statistically significantly higher compared to the expression of the SHANK1 gene. The assessed differences in the expression levels between the tested genes found the expression of the SHANK2 gene was statistically significantly higher compared to the SHANK1 gene. The analysis also revealed significant correlations between SHANK3 gene expressions in ASD patients compared to the control group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W., J.K., G.W., and E.G.; methodology, J.W., J.K., G.W., and E.G.; formal analysis, J.W., J.K., G.W., M.G., B.K., T.U., M.R.-H., and E.G.; investigation, J.W., J.K., G.W., M.G., B.K., T.U., M.R.-H., and E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W., J.K., G.W., M.G., B.K., T.U., and M.R.-H.; writing—review and editing, J.K. and E.G.; visualization, J.W., J.K., G.W., M.G., B.K., T.U., M.R.-H., and E.G.; funding acquisition, M.G., B.K., and T.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.