1. Introduction

Throwing a baseball is a dynamic, whole-body movement that places significant biomechanical and physiological demands on the athlete, particularly on the throwing arm and respiratory system [

1]. The repetitive, high-intensity nature of throwing in Division I collegiate baseball players can lead to adaptations in the shoulder's glenohumeral joint and inspiratory muscle function, which are critical for performance and injury prevention [

2,

3]. Understanding these adaptations is essential, as shoulder injuries and fatigue-related performance declines are prevalent in overhead throwing sports, affecting athletes' careers and team outcomes [

4,

5]. This study investigates the interplay between inspiratory muscle function and glenohumeral motion in the throwing arm, addressing a gap in the literature by examining these systems concurrently in a collegiate population.

The glenohumeral joint in baseball pitchers often exhibits unique range of motion (ROM) characteristics, including increased external rotation (ER) and decreased internal rotation (IR), a phenomenon known as glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) [

6,

7]. These adaptations are attributed to repetitive throwing, which induces osseous changes, such as humeral retroversion, and soft tissue alterations, including posterior capsule thickening [

8,

9]. GIRD has been identified as a risk factor for shoulder injuries, such as internal impingement and rotator cuff tears, prompting research into its biomechanical underpinnings [

10]. Recent studies have also linked lower extremity flexibility and trunk mechanics to glenohumeral ROM, suggesting that pitching is a kinetic chain activity requiring coordinated movement across multiple body segments [

11,

12]. However, controversy exists regarding whether GIRD is a pathological condition or a normal adaptation in asymptomatic pitchers, with some studies advocating for targeted stretching to mitigate deficits, while others suggest that excessive ROM restoration may destabilize the shoulder [

13,

14].

In parallel, inspiratory muscle function has emerged as a critical factor in athletic performance, particularly in sports requiring sustained high-intensity efforts. The inspiratory muscles, including the diaphragm and intercostals, support core stability and efficient oxygen delivery during dynamic movements [

15]. In sports like soccer, inspiratory muscle performance, assessed via measures like maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP), has been correlated with lower extremity strength and endurance [

16]. However, limited research has explored inspiratory muscle function in baseball pitchers, despite the respiratory demands of pitching, which involve rapid trunk rotation and force transfer [

17]. Preliminary evidence suggests that inspiratory muscle fatigue may contribute to decreased pitching velocity and altered mechanics, potentially increasing injury risk [

18]. The relationship between inspiratory muscle function and glenohumeral motion remains underexplored, representing a novel area of inquiry.

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between inspiratory performance (IP), as measured by MIP and sustained MIP (SMIP), and glenohumeral rotation mobility in the throwing arm of Division I collegiate baseball players. We expect that greater IP will be associated with greater ER mobility, indicating overstretching of accessory inspiratory muscles. The findings from this study could provide new insights into the association between IP and overall rotational mobility in the throwing arm of DICBP. The results have the potential to establish a foundation for integrating breathing exercises and IMT into training regimens to enhance both respiratory and peripheral muscle performance, ultimately improving athletic performance in baseball and other sports.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. TIRE Testing

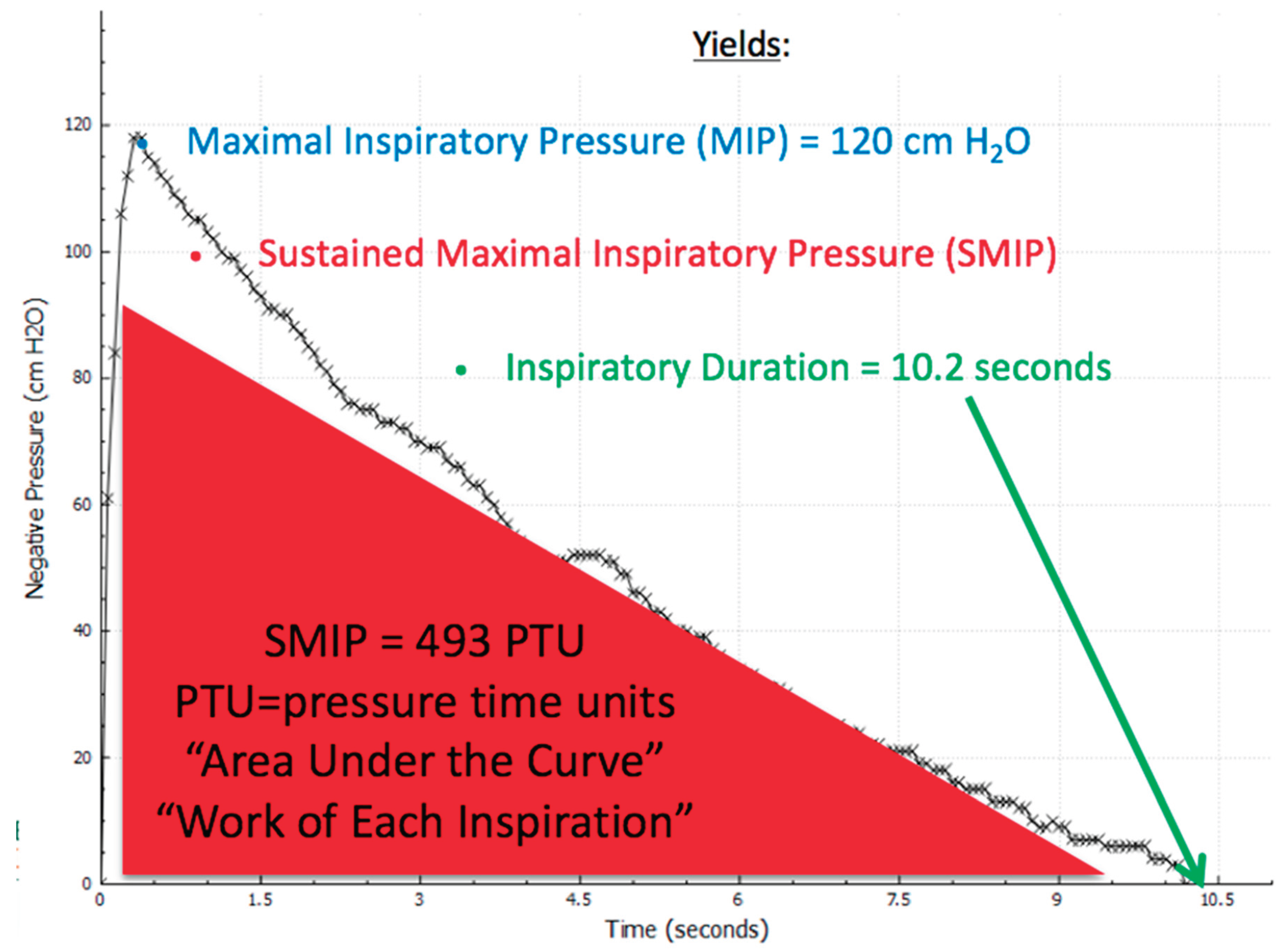

The maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP), as shown in

Figure 1, indicates the highest pressure generated by an individual during the first second of an inspiratory breath [

5]. This metric captures the peak strength of the inspiratory muscles. In contrast, the sustained maximal inspiratory pressure (SMIP) quantifies the cumulative pressure produced over the entire duration of a sustained inhalation, providing insights into the strength, endurance, and work capacity of these muscles during a single breath [

5]. In

Figure 1, MIP is represented by the initial peak of the inspiratory breath, while SMIP is depicted as the area under the pressure curve, highlighted in red.

2.2. Participants

Thirty Division I collegiate baseball players (D1CBP) from the same team participated in this study with the physical characteristics shown in

Table 1. Of the 30 participants, 14 were pitchers (7 left-handed and 7 right-handed), 11 were right-handed infielders, and 5 were outfielders (2 left-handed and 3 right-handed). A power analysis was conducted to determine the sample size necessary to detect a significant relationship between inspiratory performance and glenohumeral rotation. Based on an estimated large effect size (r= 0.5), a significance level of p < 0.05, and power (1-β) of 0.80, the minimum sample size required was determined to be 29. Thus, the current sample of 30 participants meets the threshold for detecting meaningful relationships within this specific population.

Inclusion criteria for participation included being a D1CBP and being free from respiratory or musculoskeletal conditions that could impair normal function. Exclusion criteria included recent injuries (within the past 6 months), or respiratory illnesses.

Participants were recruited through convenience sampling from a single Division I collegiate baseball team. Given the specific nature of the baseball population, this method was deemed appropriate to ensure that participants met the athletic requirements of the study.

2.3. Procedures

All participants provided informed consent prior to study participation, and the research adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol received approval from the University institutional ethics committee, and no external funding was obtained for this research. Participants underwent shoulder mobility testing using a handheld goniometer (Fabrication Enterprises Inc., White Plains, NY, USA), followed by the Test of Incremental Respiratory Endurance (TIRE) using the RT2 device (DeVilbiss Healthcare Ltd, UK). All participants had prior experience with goniometric testing as part of their routine pre-participation performance evaluations. During testing, participants were supine with their shoulder abducted to 90d, the forearm in neutral, and the length of humerus on the test side supported on a plinth to maintain proper alignment. The axis of rotation was aligned with the olecranon process of the ulna, the stationary arm was perpendicular to the floor, and the movement arm was in line with the ulnar side of the forearm from the axis point to the ulnar styloid process (Norkin CC, White DJ. Measurement of joint motion: a guide to goniometry. FA Davis; 2016 Nov 18). Participants were instructed to relax as the tester rotated their shoulder through their full range of motion. Total rotational shoulder motion (TRM) was calculated by the summation of internal and external rotation motion (Rose & Noonan, 2018). Thus, the following measures were obtained including right and left glenohumeral internal and external rotation (RGHIR, RGHER, LGHIR, and LGHER, respectively) as well as right and left total rotational motion (RTRM and LTRM, respectively).

After mobility testing, TIRE testing was performed to assess MIP and SMIP. Participants were directed to place the mouthpiece in their mouth, exhale completely, and then inhale as forcefully and for as long as possible in response to the verbal prompts "deep, long, and hard." Three to five trials were conducted, with testing concluding when performance reached a plateau and participants reported optimal execution. The trial with the highest combined MIP and SMIP values was selected, prioritizing the MIP score. Verbal encouragement and real-time biofeedback were provided during trials using the TIRE software (version 2.52).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v28, with the significance level set at p < 0.05. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables, including means and standard deviations. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality for continuous variables. Since all variables met the assumption of normality (p > 0.05), parametric tests were applied. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine differences among position groups (pitchers, infielders, outfielders) for anthropometric, biomechanical, and inspiratory performance variables. When significant main effects were observed, post-hoc Tukey’s HSD tests were conducted to determine pairwise group differences. Effect sizes for between-group comparisons were calculated using Cohen’s d, interpreted as small (0.2), medium (0.5), or large (0.8). Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were used to evaluate relationships between sustained maximal inspiratory pressure (SMIP, measured in pressure-time units [PTU]) and relevant anthropometric and biomechanical variables within the full cohort and specific subgroups. Bonferroni correction was applied to control for multiple comparisons in correlation analyses, with the adjusted alpha level set at 0.0083. All data were normally distributed based on Shapiro-Wilk tests (p > 0.05), permitting the use of parametric statistical tests.

3. Results

Thirty Division I collegiate baseball players (D1CBP) from the same team participated in this study, comprising 14 pitchers (7 left-handed, 7 right-handed), 11 infielders (all right-handed), and 5 outfielders (2 left-handed, 3 right-handed). Characteristics of inspiratory performance variables and glenohumeral mobility variables are presented in

Table 2.

Inspiratory performance across three position groups can be found in

Table 3. Outfielders exhibited the highest mean MIP (135±18 cmH2O) and a moderate SMIP (693±153 PTU), while pitchers had the highest mean SMIP (798±403 PTU) and longest inspiratory duration (12.4±4.2 seconds), with infielders showing the lowest values across all measures (MIP: 108±30 cmH2O, SMIP: 639±206 PTU, ID: 11.1±2.6 seconds).

One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences between position groups on SMIP (F(2,27) = 6.12, p = 0.006), RGHER (F(2,27) = 7.34, p = 0.003), and RTRM (F(2,27) = 6.85, p = 0.004). Post-hoc Tukey tests indicated that pitchers had significantly higher SMIP (mean: 784.6 ± 315.2 PTU) compared to infielders (mean: 672.3 ± 298.7 PTU, p = 0.008, Cohen’s d = 0.91) and outfielders (mean: 650.4 ± 304.1 PTU, p = 0.02, Cohen’s d = 1.02). Pitchers also exhibited greater RGHER (mean: 108.9 ± 11.5 degrees) and RTRM (mean: 163.2 ± 15.1 degrees) compared to infielders (RGHER: 99.1 ± 11.2 degrees, p = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 1.05; RTRM: 152.4 ± 15.4 degrees, p = 0.006, Cohen’s d = 0.98) and outfielders (RGHER: 98.4 ± 11.8 degrees, p = 0.01, Cohen’s d = 1.10; RTRM: 151.8 ± 15.9 degrees, p = 0.02, Cohen’s d = 1.03). No significant differences were found between infielders and outfielders for SMIP, RGHER, or RTRM (p > 0.05). Additionally, no significant differences were observed for maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP), inspiratory duration, right glenohumeral internal rotation (RGHIR), left glenohumeral external rotation (LGHER), or left total rotational motion (LTRM) across position groups (p > 0.05).

Correlation analyses revealed significant relationships between SMIP and both anthropometric and biomechanical variables for the entire cohort (

Table 4). SMIP was positively correlated with height (r = 0.38, p = 0.008) and weight (r = 0.42, p = 0.003), suggesting that taller and heavier players exhibited greater inspiratory muscle endurance and single-breath work capacity. Conversely, SMIP was negatively correlated with RTRM (r = -0.41, p = 0.004), suggesting that greater total rotational motion in the right shoulder was associated with lower SMIP values.

Among pitchers (n = 14), SMIP was significantly negatively correlated with RTRM (r = -0.56, p = 0.005) and LTRM (r = -0.61, p = 0.002). For right-handed pitchers (n = 7), SMIP showed a strong negative correlation with RGHER (r = -0.88, 95% CI: -0.83 to -0.93, p < 0.001). For left-handed pitchers (n = 7), SMIP was negatively correlated with LGHER (r = -0.82, p = 0.04). These findings indicate that higher SMIP values were associated with reduced external rotation in the dominant throwing arm. No significant correlations were found between SMIP and LGHER in right-handed pitchers or between SMIP and RGHER in left-handed pitchers (p > 0.05). All significant correlations remained significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (adjusted α = 0.0083).

RTRM= right total rotational motion; RGHER=right glenohumeral external rotation; LGHER=left glenohumeral external rotation; RHP=??; LHP=??.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal significant differences in inspiratory muscle function and glenohumeral motion between position groups among Division I collegiate baseball players, alongside notable correlations between sustained maximal inspiratory pressure (SMIP) and both anthropometric and biomechanical variables. These results provide insights into the interplay between respiratory muscle performance and shoulder mechanics in elite pitchers, supporting our hypothesis that inspiratory muscle function may influence glenohumeral range of motion (ROM) and, by extension, pitching performance and injury risk.

Significant differences in SMIP and glenohumeral motion metrics (e.g., RTRM, LTRM, RGHER, and LGHER] between position groups align with prior research indicating positional specialization in baseball. Pitchers, who experience repetitive, high intensity throwing, likely develop distinct biomechanical adaptations compared to position players, as evidenced by studies on shoulder ROM and muscle recruitment patterns [

1,

2]. For instance, Wilk et al. [

2] reported that pitchers exhibit greater external rotation and reduced internal rotation in the throwing arm, a pattern consistent with GIRD. Our findings extend this by suggesting that inspiratory muscle performance, as measured by SMIP, also varies by position, potentially reflecting the greater respiratory demands of pitching, which involves rapid trunk rotation and force transfer [

17]. These positional differences demonstrate the need for tailored training programs that address both respiratory and shoulder mechanics specific to player roles.

The positive correlations between SMIP and anthropometric measures (height and weight) in the entire cohort suggest that larger body size may confer advantages in inspiratory muscle capacity, consistent with studies in other athletic populations [

15]. Taller and heavier athletes are likely to have greater diaphragmatic descent and greater lean muscle mass contributing to stronger primary and accessory muscles of breathing resulting in higher SMIP values and greater lung volumes. These factors may be particularly relevant for pitchers, who require enhanced levels of core stability to support the kinetic chain during throwing [

19]. However, the negative correlation between SMIP and RTRM (r = -0.41, p < 0.05) across all players, and stronger negative correlations with RTRM and LTRM in pitchers (r = -0.56 to -0.61, p < 0.05), indicate an interplay between inspiratory muscle endurance/work and shoulder mobility. These findings suggest that greater inspiratory muscle performance may be associated with reduced total rotational motion, potentially due to increased core stiffness that limits excessive shoulder rotation [

18]. This hypothesis contrasts with studies suggesting that enhanced respiratory muscle function improves overall athletic performance without restricting joint mobility [

20]. The discrepancy may reflect sport-specific adaptations in baseball, where excessive glenohumeral rotation is a known risk factor for shoulder injuries [

10].

Particularly striking are the strong negative correlations between SMIP and RGHER in right-handed pitchers (r = -0.83 to -0.93, p < 0.05) and LGHER in left-handed pitchers (r = -0.82, p = 0.04). These findings suggest that pitchers with greater inspiratory muscle endurance/work may exhibit reduced external rotation in their throwing arm, potentially as a protective mechanism against excessive ROM. Previous studies have linked increased external rotation to higher pitching velocity but also to greater injury risk, such as rotator cuff tears and internal impingement [

6,

9]. The negative correlation between SMIP and RGHER/LGHER may indicate that stronger inspiratory muscles enhance core stability, thereby constraining shoulder motion to prevent pathological over-rotation [

21]. This interpretation aligns with biomechanical models of the kinetic chain, where trunk stability modulates force transmission to the upper extremity [

12]. However, it diverges from studies in other sports, such as soccer, where inspiratory muscle training improved performance without altering joint mechanics [

16]. These sport-specific differences show the unique biomechanical demands of pitching and suggest that inspiratory muscle function may play a dual role in enhancing performance while mitigating injury risk.

The implications of these findings are significant for both performance optimization and injury prevention in collegiate baseball. The negative correlations between SMIP and glenohumeral motion metrics suggest that inspiratory muscle training could be integrated into conditioning programs to enhance core stability and potentially reduce excessive shoulder rotation, a known contributor to GIRD and related injuries [

7]. However, the optimal balance between inspiratory muscle strength and shoulder mobility remains unclear, as excessive core stiffness could theoretically limit pitching efficiency [

14]. Coaches and athletic trainers should consider individualized assessments of SMIP and glenohumeral ROM to tailor interventions, particularly for pitchers who exhibit extreme external rotation values.

In a broader context, these results contribute to the growing recognition of the respiratory system’s role in athletic performance, extending beyond the traditional focus on the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems [

22]. The interplay between inspiratory muscle function and glenohumeral motion suggests that whole-body training approaches, integrating respiratory, core, and upper extremity conditioning, may enhance pitching performance and longevity. This study also highlights the importance of considering positional differences in training and rehabilitation protocols, as pitchers face unique biomechanical and physiological demands compared to other players.

Future research should address several limitations of this study. First, longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether changes in SMIP, induced by targeted inspiratory muscle training, directly influence glenohumeral motion and injury rates. Second, investigating the mechanistic link between inspiratory muscle performance and shoulder mechanics, potentially through electromyography or motion capture, could clarify how core stability modulates throwing biomechanics [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Third, expanding the sample to include professional or younger athletes could elucidate whether these findings are specific to Division I collegiate players or generalizable across baseball populations. Finally, exploring the role of other respiratory parameters, such as expiratory muscle strength, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of respiratory contributions to pitching and throwing performance [

27,

28].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates significant positional differences and strong correlations between SMIP and glenohumeral motion in Division I collegiate baseball players, offering new insights into the biomechanical and physiological factors influencing throwing performance. These findings advocate for a holistic approach to training that considers the interplay between respiratory and shoulder function, with potential applications for enhancing performance and reducing injury risk. Further research is warranted to validate these relationships and optimize training strategies for elite baseball athletes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A.F. and L.P.C., M.A.R..; methodology, L.A.F., M.C., J.J.R., M.A.R. and L.P.C.; formal analysis, L.P.C.; investigation, L.A.F. and L.P.C.; resources, L.D.K. and J.J.R.; data curation, L.P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A.F. and L.P.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C. M.A.R.; visualization, L.P.C.; supervision, L.A.F and L.P.C.; project administration, L.A.F and L.P.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami (protocol code 2012034 and 6/01/2018) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Escamilla, R; Andrews, J.R. Shoulder muscle recruitment patterns and biomechanics during upper extremity sports. Sports Med. 2009, 39, 569-590. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilk, K.E.; Macrina, L.C.; Fleisig, G.S.; Porterfield, R; Simpson, C.D., 2nd; Harker, P; Paparesta, N; Andrews, J.R. Correlation of glenohumeral internal rotation deficit and total rotational motion to shoulder injuries in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2011, 39, 329-335. [CrossRef]

- Hart, E; Godek, S.F.; Kulig, K. Inspiratory muscle training in athletes: A systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2020, 34, 2353-2361.

- Shanley, E; Rauh, M.J.; Michener, L.A., Ellenbecker, T.S. Incidence of injuries in high school softball and baseball players. J Athl Train. 2011, 46, 648-654. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conte, S; Camp, C.L.; Dines, J.S. Injury trends in Major League Baseball over 18 seasons: 1998-2015. Am J Orthop. 2016, 45, 116-123. [PubMed]

- Reagan, K.M.; Meister, K; Horodyski, M.B.; Werner, D.W; Carruthers, C; Wilk, K. Humeral retroversion and its relationship to glenohumeral rotation in the shoulder of college baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2002, 30, 354-360. [CrossRef]

- Manske, R; Wilk, K.E.; Davies, G; Ellenbecker, T; Reinold, M. Glenohumeral motion deficits: Friend or foe? Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013, 8, 537-553. [PubMed]

- Takenaga, T; Sugimoto, K; Goto, H; Nozaki, M; Fukuyoshi, M; Tsuchiya, A; Murase, A; Ono, T; Otsuka, T. Posterior shoulder capsules are thicker and stiffer in the throwing shoulders of healthy college baseball players: A quantitative assessment using shear-wave ultrasound elastography. Am J Sports Med. 2015, 43, 2935-2942. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.J.; Swanik, C.B.; Kaminski, T.W.; Higginson, J.S.; Swanik, K.A.; Bartolozzi, A.R.; Nazarian, L.N. Humeral retroversion and its association with posterior capsule thickness in collegiate baseball players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012, 21, 910-916. [CrossRef]

- Burkhart, S.S.; Morgan, C.D.; Kibler, W.B. The disabled throwing shoulder: Spectrum of pathology part I: Pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003, 19, 404-420. [CrossRef]

- Rubino, L.J.; Brown, J.A.; Swanik, C.B. Glenohumeral range of motion and lower extremity flexibility in collegiate-level baseball players. J Athl Train. 2016, 51, S-123. [CrossRef]

- Oyama, S; Yu, B; Blackburn, J.T.; Padua, D.A.; Li, L.; Myers, J.B. Effect of excessive contralateral trunk tilt on pitching biomechanics and performance in high school baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2013, 41, 2430-2438. [CrossRef]

- Wilk, K.E.; Reinold, M.M.; Andrews, J.R. The athlete’s shoulder: Management of glenohumeral internal rotation deficit. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009, 39, A1-A12.

- Kibler, W.B.; Sciascia, A; Thomas, S.J. Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit: Pathogenesis and response to acute throwing. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012, 42, A1-A12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, A.K. Respiratory muscle training: Theory and practice. Elsevier; 2013.

- Hart, E; Kulig, K. Inspiratory muscle performance is significantly related to acceleration and deceleration of isokinetic knee extension and flexion in Division I collegiate women soccer players: A pilot study. MDPI Sports. 2021, 9, 67.

- Laudner, K.G.; Wong, R; Meister, K. The influence of lumbopelvic control on shoulder and elbow kinetics in elite baseball pitchers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019, 28, 330-336. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, G.D.; Plummer, H; Brambeck, A. The relationship between trunk stability and pitching velocity in NCAA Division I baseball pitchers. J Strength Cond Res. 2016, 30, S45-S46.

- Kibler, W.B.; Press, J.; Sciascia A. The role of core stability in athletic function. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 189-198. [CrossRef]

- Hart, E; Godek, S.F.; Kulig, K. Inspiratory muscle training in athletes: A systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2020, 34, 2353-2361.

- McConnell, A.K.; Romer, L.M. Respiratory muscle training in healthy humans: Resolving the controversy. Int J Sports Med. 2004, 25, 284-293. [CrossRef]

- Sheel, A.W.; Romer, L.M. Ventilation and respiratory mechanics. Compr Physiol. 2012, 2, 1093–1142. [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, R.F.; Barrentine, S.W.; Fleisig, G.S.; Zheng, N; Takada, Y; Kingsley, D; Andrews, J.R. Pitching biomechanics as a pitcher approaches muscular fatigue during a simulated baseball game. Am J Sports Med. 2007, 35, 23-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotin, R.L.; Conforti, C. A Case Study Exploring the Effects of a Novel Intra-Abdominal Pressure Belt on Fastball and Change-Up Velocity, Command, and Deception Among Collegiate Baseball Pitchers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10471. [CrossRef]

- Lebowitz, M.; Lowell, G.H.; April, M.; Ritchie, Z.; van der Putten Landau, M.; Ehrenberg, M. Case Study: Using Healables® ElectroGear® Wearable E-Textile Sleeve with Embedded Microcurrent Electrodes and WelMetrix® Physiologic Motion Sensors to Enhance and Monitor the Sporting Performance of a Baseball Pitcher. Eng. Proc. 2023, 52, 34.

- Cheng, S.C.; Wan, T.Y.; Chang, C.H. The Relationship between the Glenohumeral Joint Internal Rotation Deficit and the Trunk Compensation Movement in Baseball Pitchers. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021, 57, 243. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.S.; Vieira, R.G.d.S.; Wanderley e Lima, T.B.; Resqueti, V.R.; Vilaro, J.; Fonseca, J.D.M.d.; Ribeiro-Samora, G.A.; Fregonezi, G.A.d.F. Effect of Body Position on Electrical Activity of Respiratory Muscles During Mouth and Nasal Maximal Respiratory Pressure in Healthy Adults: A Pilot Study. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 241. [CrossRef]

- Deliceoğlu, G.; Kabak, B.; Çakır, V.O.; Ceylan, H.İ.; Raul-Ioan, M.; Alexe, D.I.; Stefanica, V. Respiratory Muscle Strength as a Predictor of VO2max and Aerobic Endurance in Competitive Athletes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8976. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).