1. Introduction

Creativity is defined as the tendency to produce original and effective ideas (Runco & Jaeger, 2012). Literature has concluded that creativity is associated to positive outcomes in human development, such as intelligence development, academic performance and subjective well-being (Du et al., 2020). Recently, researchers have addressed both individual and contextual factors, such as personality, cognitive style or supportive context (Mathisen & Bronnick, 2009). Among the psychological mechanisms underlying the creative behavior, creative self-efficacy refers to “the belief one has the ability to produce creative outcomes” (Tierney & Farmer, 2002; p. 1138). This belief in one’s ability may help to innovatively overcome problems and achieve creative outcomes (Gonzalez et al., 2024). This concept is derived from Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy, which entails the person’s belief that he/she can successfully manage cognitive resources towards the creative generation of such outcomes within a specific social setting (Puente-Diaz, 2015). Social cognitive theory stated that self-efficacy plays a key motivational role in the process of creativity and innovation (Bandura, 1997).

Consequently, creative self-efficacy is an important antecedent of creative performance, because creative behavior requires some effort and persistence across possible difficulties. Thus, self-perception in own skills may predict creative efforts and in turn, creative performance (Tierney & Farmer, 2002). High creative self-efficacy facilitates concentration and improves self-confidence against task efforts (Du et al., 2020). The development of creative self-efficacy was associated with creative role identity and perceived creative expectation (Tierney & Farmer, 2011). Education may provide opportunities to enjoy experiences, perspectives and knowledge which reinforce the use of creative problem-solving skills, as well as the experimentation necessary to put into practice innovative tasks (Tierney & Farmer, 2002). In this line, creative self-efficacy has been identified as a mechanism between creative mindsets and creative problem solving (Royston & Reiter-Palmon, 2017). Some research has highlighted the importance of fostering the personal assets of creative self-efficacy as an important variable for performance development (Mathisen & Bronnick, 2009). A recent meta-analysis by Haase et al. (2018) concluded that creative self-efficacy was positively related to different creativity measures, with smaller size effect with objective measures of creative performance and stronger in self-report measures.

Creative self-efficacy was also found to be associated with better psychological well-being and academic performance in adolescent and youth samples. In a sample of Chinese undergraduates, Fino and Sun (2022) found that openness to experience and conscientiousness personality traits were connected to more wellbeing through its impact on creative self-efficacy. In US university students, Stolz et al. (2022) concluded that the improvement in creative self-efficacy was linked with better coping with current academic and future career challenges. Furthermore, in adolescents from the USA, Beghetto (2006) found that students with more creative self-efficacy reported more positive beliefs about their academic abilities in all subject areas, were more likely to indicate that they planned to attend college and showed more frequent participation in after-school activities. In a study with Polish adolescents, Karwowski et al. (2018) showed positive associations between creative self-efficacy, creative thinking, self-esteem, emotional intelligence and intrinsic motivation.

The connections between creative self-efficacy – as a personal asset, psychological well-being and academic outcomes could be well interpreted within the Relational Developmental Systems Theory (RDST; Overton, 2014). Creative self-efficacy may be considered as an internal asset for PYD which implies self-regulated cognitive skills to facilitate knowledge construction, task completion, problem solving, and decision making (Sun & Hui, 2012). RDST is a meta-theory in developmental science conceptualizes living organisms as active agents in their contexts, that is, self-creating, self-organizing and self-regulating. In this vein,

Positive Youth Development (PYD) is a strength-based framework that supports young people as they transition into adulthood. It emphasizes the balance between individual abilities and supportive environments (Lerner et al., 2011). In recent decades, research across countries has supported the 5Cs model of PYD (Dimitrova & Wiium, 2021). According to Lerner et al. (2021), these 5Cs serve as indicators of a thriving individual, as they are linked to better physical health and psychological well-being (Lewin-Bizan et al., 2010): Competence (refers to a sense of efficacy in various aspects of life), Confidence (reflects a positive self-image and self-esteem), Connection (involves strong, positive relationships with others), Character (the internalization of societal and cultural norms), and Caring (represents empathy and compassion toward others). When these five dimensions are fulfilled, a sixth one—Contribution—emerges. This includes meaningful engagement that benefits both the individual and their community, such as family, peers, or society. Additionally, the 5Cs act as protective factors against risky behaviors like substance use or delinquency, as well as emotional difficulties (Lerner et al., 2014). Complementing the PYD model and rooted in the RDST, Benson (2007) introduced the concept of Developmental Assets—key conditions that support youth development. These are divided into two groups: internal assets (e.g., a drive to learn, strong values, social skills, and positive identity), and external assets (e.g., social support, empowerment, clear boundaries and expectations, and positive use of time).

Concerning the links between PYD and academic achievement, some works have provided some supportive evidence. Beck and Wiium (2019) found in a sample of Norwegian high school students that some developmental assets were positively connected with academic achievement, specifically commitment to learning, support and positive identity). In a study with Slovenian adolescents, Kozina et al. (2019) concluded that Character and Confidence were associated with better math achievement. Abdul-Kadir et al. (2021) even included self-reported creativity as a part of PYD, including a 7th C. Creativity was found to be correlated with the 5Cs of PYD and to have a positive effect on mindfulness skills. Thus, creative self-efficacy may fit very well into this RDST, as an internal asset that may be connected to more PYD and in turn with positive academic outcomes in youth.

1.1. The Present Study

Most PYD research to date has addressed the connections between PYD, risk behaviors and mental health, while further work is still needed to examine academic outcomes. As far as we know to study to date has explore this connection in Spanish youth. Moreover, despite the research evidence for the positive interrelations between creative self-efficacy, wellbeing and academic outcomes, no study has examined the relationships with the 5Cs of PYD. Following RDST model, creative self-efficacy could relate to better academic achievement through improvements in PYD. Thus, the present work aimed at examining the associations between creative self-efficacy, PYD and perceived academic performance in a sample of Spanish youth. We expected positive associations between creative self-efficacy, PYD and academic performance, in line with previous literature. Specifically, as the main new contribution of the present work, we aim to explore the mediation of the 5Cs of PYD in the relationship between creative self-efficacy and perceived academic performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Procedure and Sample Composition

A cross-sectional study was conducted during the spring of 2024 using an online self-report questionnaire. Undergraduate students completed the survey in approximately 30 minutes. The research adhered to the ethical standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of [Anonymised] on January 10, 2019 (UHU1259711). Participation was voluntary, with no compensation provided, and all participants gave written informed consent.

In total, 370 undergraduate students took part (67.2% women, 31.4% men, and 1.4% non-binary), ranging in age from 18 to 29 years (M = 21.29, SD = 3.61). They were enrolled in ten universities across Andalusia, a region in southern Spain: the Universities of Almería, Cádiz, Córdoba, Granada, Huelva, Jaén, Málaga, and Seville, as well as Pablo de Olavide University (Seville) and Loyola University (Seville and Córdoba). Most participants lived in cities with populations above 300,000 (38.4%) or between 50,001 and 300,000 (31.1%). Living arrangements were primarily with parents (49.5%) or flatmates (30.5%). Over half (54.5%) reported not being in a romantic relationship, and 65.6% were not currently seeking employment. Regarding academic disciplines, 39.7% were pursuing degrees in Law or Social Sciences, 29.6% in Sciences or Engineering, 19.2% in Arts and Humanities, and 11.5% in Health Sciences. Approximately half were in their first or second year of study, 42.6% were in their third year, and 7.4% were in their fourth year or higher.

2.2. Instrument

Positive youth development. The short form of the Positive Youth Development (PYD) scale developed by Geldhof et al. (2014) was employed in this study. A Spanish adaptation by [Anonymized] was utilized, demonstrating strong internal consistency and factorial validity. The instrument consists of 34 items distributed across five core dimensions, known as the 5Cs: Competence (6 items, e.g., “I have a lot of friends”); Confidence (6 items, e.g., “I like my physical appearance”); Character (8 items, e.g., “I never do things I know I shouldn’t do”); Connection (8 items, e.g., “I am a useful and important member of my family”), and Caring (6 items, e.g., “It bothers me when bad things happen to other people”). Responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale, with formats varying by item (e.g., from 1 = “Not at all important” to 5 = “Very important”; 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”; 1 = “Not at all” to 5 = “Very much”; or 1 = “Never or almost never” to 5 = “Always”). The reliability coefficients for each dimension were acceptable: Character (α = 0.66), Competence (α = 0.67), Confidence (α = 0.74), Connection (α = 0.75), and Caring (α = 0.79).

Creative self-efficacy. Creative Self-efficacy Scale, developed by Yi et al. (2008) and adapted to Spanish by Aranguren et al. (2011) was administered. This scale is composed of five items (“I am certain that I can produce novel and appropriate ideas” or “When I am confronted with a problem, I can try several solutions to solve it”), with a 4-point Likert response, ranging from not at all true to exactly true. Acceptable internal consistency reliability was observed, with α = 0.77.

Perceived performance at the university. This variable was evaluated by using this question “How is your academic performance?”. Five response options were showed to be selected: 1 = “Low”, 2 = “Sufficient”, 3 = “Good”, 4 = “Very good” and 5 = “Excellent”).

2.3. Data Analysis Design

First, descriptive statistics were examined for 5Cs of PYD, creative self-efficacy and perceived academic performance. Second, bivariate Pearson correlations were conducted among study variables. Third, two hierarchical regression analyses were separately performed to explain creative self-efficacy, based on demographics (i.e., gender and age) and the 5Cs of PYD, and to explain perceived academic performance, based on demographics, creative self-efficacy and the 5Cs. Standardized coefficients and R-squared were described in these regression analyses, conducted with SPSS 21.0. Fourth, based on the previous results, some mediation models were tested to explore the mediation role of each dimension of PYD in the relationship between creative self-efficacy and perceived academic performance. Total, direct, indirect, and total indirect effects were detailed, as well as Z scores and confidence intervals. These regression-based mediational models were designed and tested with JASP 0.18.3.0., according to the indications by Hayes (2013).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between study variables. Results indicated moderate high scores in creative self-efficacy and self-perceived academic performance. Up to 86.6% of the participants indicated good (44.8%), very good (34.1%) or excellent performance (7.7%). Regarding positive youth development, the highest mean scores were found in caring and character, while the lowest one was detected in competence. Acceptable internal consistency reliability was observed in all the variables. Furthermore, correlation analyses showed positive bivariate associations between the creative self-efficacy, 5Cs of PYD and perceived performance. The strongest associations with creative self-efficacy were found with confidence, character and competence. Moreover, the strongest correlations with academic performance were detected with competence and confidence.

3.2. Regression and Mediation Analyses

Table 2 describes the results of two hierarchical regression analyses to respectively explain the creative self-efficacy, based on demographics (gender and age) and the 5Cs of PYD, and to explain academic performance based on demographics, creative self-efficacy, and the 5Cs of PYD. Concerning creative self-efficacy, gender had a positive effect, t(358) = -1.99, p = .047, d = -.23, with men showing higher mean (M= 3.07, SD = .51) than woman (M = 2.96, SD = .50). In the second step, confidence and competence showed positive effects to explain creative self-efficacy in nearly 20%. Furthermore, creative self-efficacy, competence and confidence were found to present positive effects to explain academic performance (R2 = .117).

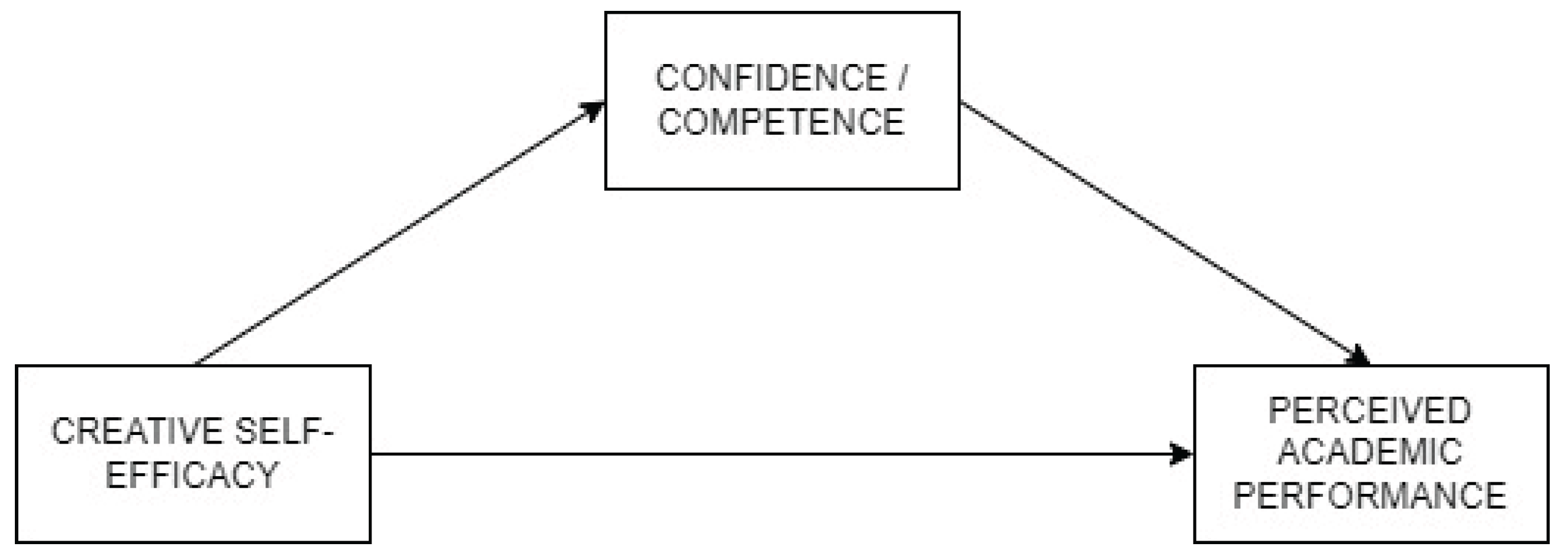

Based on the preliminary results, two mediational models were tested in order to examine the mediational role of competence and confidence in the relationship between creative self-efficacy and academic performance (

Figure 1 and

Table 3). First, confidence totally mediated the relationship between creative self-efficacy and academic performance, so that high creative self-efficacy was associated with high confidence, and in turn with high performance. After including the mediator, the direct effect by creative self-efficacy was not significant. Thus, a positive indirect effect was observed through the mediation by confidence. Second, competence was also found to totally mediate the link between creative self-efficacy and performance. The effect by creative self-efficacy on performance was not significant after including competence as mediator, which showed a positive indirect effect. Low levels of explained variance for academic performance were found in both mediational analyses.

4. Discussion

The main goal of the present work was to analyze the associations between creative self-efficacy, PYD and perceived academic performance. The results showed that the 5Cs of PYD presented positive associations with both creative self-efficacy and perceived academic performance. Concretely Competence and Confidence had the strongest effects on perceived performance after controlling for creative self-efficacy. These results underline the role of creative self-efficacy as internal asset for PYD, consistently with RDST (Overton, 2014), and with the previous literature about the connections between creative self-efficacy and well-being, such as Fino and Sun (2022) and Karwowski et al. (2018). The main contribution of the present work was the analysis of the mediation by Competence and Confidence in the relationship between creative self-efficacy and perceived academic performance. Our results pointed out that these two dimensions of PYD were total mediators in that association, so that creative self-efficacy increased both competence and confidence, and these Cs were positively related to more perceived academic performance. This mediational role of PYD is in line with results about positive academic outcomes derived from PYD, such as the works by Beck and Wiium (2019) and Kozina et al. (2019). Specifically, the dimensions of Confidence and Competence were the Cs more strongly associated with creative self-efficacy, because they respectively referred to positive self-worth and general self-efficacy. Thus, the present research provides evidence for the application of the RDST to the relationship between creative self-efficacy and academic performance, mediated by PYD. More creative self-efficacy may encourage young people to pay greater efforts to cope with academic challenges, by fostering their self-esteem and general self-efficacy. In turn, better academic achievement is derived from both increased creative self-efficacy and well-being.

Some practical implications may be derived from these contributions. Interventions to foster creative self-efficacy in Higher Education jointly with PYD should be encouraged in order to promote better academic achievement. The importance of creative cognitive processes in Higher education has been well recognized (Miller and Dumford, 2014). Some authors have underlined the need to establish the conditions for the flourishing of creativity in higher education institutions, in example, having sufficient time and space for creativity development, presenting varied working situations, allowing students the freedom to work in new ways, challenging students with real problems, taking into account previous knowledge, encouraging students to pursue topics that interest them most, and understanding individual differences in problem solving (Soriano de Alencar et al., 2017). In this line, some programs have received some support. In China, Byrge and Tang (2015) developed an embodied creative program for undergraduates, based on creative fitness exercising, 20-hour workshop about creative techniques, a national entrepreneurship festival and a final theoretical reflection. This program was found to increase creative self-efficacy and creative production. Furthermore, in Norway, Mathisen and Bronick (2009) conducted a program for students and municipality employees about lectures, discussions, and demonstrations about central theories and research on creativity. Self-efficacy levels increased significantly for both students and municipality employees. Other intervention in a Portuguese university found that a cooperative learning program to teach creative skills improved creative and divergent thinking (Catarino et al., 2009). A recent experience, conducted with higher education students in Israel, found that a 3-month Future Problem-Solving program focused on peace education and teacher training through engendering creativity and innovation skills, improved their beliefs about their abilities to produce creative ideas and innovative behaviors. These creativity programs may be well-integrated into PYD promotion programs, such as 4-h program (Arnold and Gagnon, 2020; Lerner et al., 2014), in university context, which was found to be effective in promoting good academic outcomes, such as academic competence and engagement (Li et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2009).

Despite the contributions and potential implications for practice, some limitations may be acknowledged in the conclusions of this study. First, the conclusions are only based on associations between the variables and directionally cannot be concluded. The directionality in the relationships included in the model are only inferences based on regression analyses. The examination of causal relationships would require an experimental design, while the establishment of directionality would need a prospective design. Concerning the assessment of creativity, the present work addressed creative self-efficacy, which could be well measured by using a self-report. Other instruments may complete the analysis of creativity, by administering other instruments, such as Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (Kaufman, 2012), Creative Potential and Practised Creativity (DiLiello & Houghton, 2008), or Lifetime Creativity Scales (Richards et al., 1988). Future research may also examine other academic results, such as academic anxiety or motivation. Another limitation came from the size and characteristics of the sample. The use of a small and convenient sample would limit the generalization of the results to the undergraduates’ population in Spain.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this manuscript provides evidence for the positive interrelations between creative self-efficacy, PYD and academic performance. Creative self-efficacy was found to have a positive effect on perceived academic performance through its positive associations with both Confidence and Competence dimensions of PYD. These results may suggest the need to integrate creativity and PYD programs in Higher education in order to strengthen academic performance.

Author Contributions

D.G.-B. and M.G.M. contributed to the conceptualization. D.G.-B. and F.J.G.-M. contributed to the methodology. D.G.-B. and G.T. were responsible for the validation and carried out data analysis. D.G.-B. wrote the original draft preparation. F.J.G.-M., G.T. and M.G.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Excellence Project of the Consejeria de Universidad, Investigacion e Innovacion of Junta de Andalucia (Spain), entitled Positive Youth Development in Andalusian University Students: Longitudinal Analysis of Gender Differences in Well-Being Trajectories, Health-Related Lifestyles and Social and Environmental Contribution, grant number PROYEXCEL_00303).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Huelva (protocol code UHU-1259711 and date of approval: 10 January 2019) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdul Kadir, N.B.Y., Mohd, R.H., & Dimitrova, R. (2021). Promoting mindfulness through the 7Cs of positive youth development in Malaysia. In Handbook of Positive Youth Development: Advancing Research, Policy, and Practice in Global Contexts, pp. 49–62. [CrossRef]

- Alt, D., Kapshuk, Y., & Dekel, H. (2023). Promoting perceived creativity and innovative behavior: Benefits of future problem-solving programs for higher education students. Thinking Skills and Creativity 47: 101201. [CrossRef]

- Aranguren, M., Oviedo, A.B., & Irrazabal, N. (2011). Estudio exploratorio de las propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Autoeficacia Creativa. Revista de Psicología de la Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina 7(14): 69–91.

- Arnold, M.E., & Gagnon, R.J. (2020). Positive youth development theory in practice: An update on the 4-H Thriving Model. Journal of Youth Development 15(6): 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control, vol. 604. New York: Freeman.

- Beck, M., & Wiium, N. (2019). Promoting academic achievement within a positive youth development framework. Norsk Epidemiologi 28(1–2): 79–87. [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R.A. (2006). Creative self-efficacy: Correlates in middle and secondary students. Creativity Research Journal 18(4): 447–457. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1207/s15326934crj1804_4.

- Benson, P.L. (2007). Developmental assets: An overview of theory, research, and practice. In Approaches to Positive Youth Development, pp. 33–58. [CrossRef]

- Byrge, C., & Tang, C. (2015). Embodied creativity training: Effects on creative self-efficacy and creative production. Thinking Skills and Creativity 16: 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Catarino, P., Vasco, P., Lopes, J., Silva, H., & Morais, E. (2019). Cooperative learning on promoting creative thinking and mathematical creativity in higher education. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 17(3): 5–22. [CrossRef]

- DiLiello, T.C., & Houghton, J.D. (2008). Creative potential and practised creativity: Identifying untapped creativity in organizations. Creativity and Innovation Management 17(1): 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, R., & Wiium, N. (2021). Handbook of Positive Youth Development: Advancing the Next Generation of Research, Policy and Practice in Global Contexts. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Du, K., Wang, Y., Ma, X., Luo, Z., Wang, L., & Shi, B. (2020). Achievement goals and creativity: The mediating role of creative self-efficacy. Educational Psychology 40(10): 1249–1269. [CrossRef]

- Fino, E., & Sun, S. (2022). “Let us create!”: The mediating role of Creative Self-Efficacy between personality and mental well-being in university students. Personality and Individual Differences 188: 111444. [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G.J., Bowers, E.P., Boyd, M.J., Mueller, M.K., Napolitano, C.M., Schmid, K.L., … & Lerner, R.M. (2014). Creation of short and very short measures of the five Cs of positive youth development. Journal of Research on Adolescence 24(1): 163–176. [CrossRef]

- González, A.C., Laforêt, B., & Levillain, P.C. (2024). Abstract mindset favors well-being and reduces risk behaviors for adolescents in relative scarcity. Psychology, Society & Education 16(1): 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Haase, J., Hoff, E.V., Hanel, P.H.P., & Innes-Ker, Å. (2018). A meta-analysis of the relation between creative self-efficacy and different creativity measurements. Creativity Research Journal 30(1): 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

- Karwowski, M., Lebuda, I., & Wiśniewska, E. (2018). Measuring creative self-efficacy and creative personal identity. The International Journal of Creativity & Problem Solving 28(1): 45–57.

- Kaufman, J.C. (2012). Counting the muses: Development of the Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS). Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 6(4): 298. [CrossRef]

- Kozina, A., Wiium, N., Gonzalez, J.M., & Dimitrova, R. (2019). Positive youth development and academic achievement in Slovenia. Child & Youth Care Forum 48: 223–240. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M., Lerner, J.V., & Benson, J.B. (2011). Positive youth development: Research and applications for promoting thriving in adolescence. Advances in Child Development and Behavior 41: 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M., Lerner, J.V., Murry, V.M., Smith, E.P., Bowers, E.P., Geldhof, G.J., & Buckingham, M.H. (2021). Positive youth development in 2020: Theory, research, programs, and the promotion of social justice. Journal of Research on Adolescence 31(4): 1114–1134. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M., Wang, J., Chase, P.A., Gutierrez, A.S., Harris, E.M., Rubin, R.O., & Yalin, C. (2014). Using relational developmental systems theory to link program goals, activities, and outcomes: The sample case of the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. New Directions for Youth Development 2014(144): 17–30. [CrossRef]

- Lewin-Bizan, S., Bowers, E.P., & Lerner, R.M. (2010). One good thing leads to another: Cascades of positive youth development among American adolescents. Development and Psychopathology 22(4): 759–770. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Bebiroglu, N., Phelps, E., Lerner, R.M., & Lerner, J.V. (2008). Out-of-school time activity participation, school engagement and positive youth development: Findings from the 4-H study of positive youth development. Journal of Youth Development 3(3): 22. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L., Phelps, E., Lerner, J.V., & Lerner, R.M. (2009). Academic competence for adolescents who bully and who are bullied: Findings from the 4-H study of positive youth development. The Journal of Early Adolescence 29(6): 862–897. [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, G.E., & Bronnick, K.S. (2009). Creative self-efficacy: An intervention study. International Journal of Educational Research 48(1): 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.L., & Dumford, A.D. (2016). Creative cognitive processes in higher education. The Journal of Creative Behavior 50(4): 282–293. [CrossRef]

- Overton, W.F. (2013). A new paradigm for developmental science: Relationism and relational-developmental systems. Applied Developmental Science 17(2): 94–107. [CrossRef]

- Puente-Díaz, R. (2016). Creative self-efficacy: An exploration of its antecedents, consequences, and applied implications. The Journal of Psychology 150(2): 175–195. [CrossRef]

- Richards, R., Kinney, D.K., Benet, M., & Merzel, A.P. (1988). Assessing everyday creativity: Characteristics of the Lifetime Creativity Scales and validation with three large samples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54(3): 476. [CrossRef]

- Royston, R., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2019). Creative self-efficacy as mediator between creative mindsets and creative problem-solving. The Journal of Creative Behavior 53(4): 472–481. [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.A., & Jaeger, G.J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal 24(1): 92–96. [CrossRef]

- Soriano de Alencar, E.M., de Souza Fleith, D., & Pereira, N. (2017). Creativity in higher education: Challenges and facilitating factors. Temas em Psicologia 25(2): 553–561. [CrossRef]

- Stolz, R.C., Blackmon, A.T., Engerman, K., Tonge, L., & McKayle, C.A. (2022). Poised for creativity: Benefits of exposing undergraduate students to creative problem-solving to moderate change in creative self-efficacy and academic achievement. Journal of Creativity 32(2): 100024. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.C., & Hui, E.K. (2012). Cognitive competence as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal 2012(1): 210953. [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P., & Farmer, S.M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal 45(6): 1137–1148. [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P., & Farmer, S.M. (2011). Creative self-efficacy development and creative performance over time. Journal of Applied Psychology 96(2): 277. [CrossRef]

- Yi, X., Scheithauer, H., Lin, C., & Schwarzer, R. (2008). Creativity, Efficacy and Their Organizational Cultural Influences (PhD thesis). Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie der Freien Universität Berlin. Recuperado de https://refubium.fu-berlin.de.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).