Introduction

Employee engagement has emerged as a critical factor influencing organizational success, with heightened engagement predicting lower turnover, greater productivity, and improved safety outcomes (Harter et al., 2009). As such, understanding the drivers of discretionary effort in the workplace remains a top priority for leaders and HR professionals. However, employee experiences and the dynamics shaping engagement are likely to differ based on various personal attributes, including generational cohort and gender.

Existing research has yielded mixed and sometimes contradictory findings on the relationships between generation, gender, and employee engagement. While some studies have identified distinct engagement predictors across age groups, the nuances of how factors like basic needs fulfillment, individual determinants, teamwork dynamics, and growth opportunities impact discretionary effort for different generations and genders remain under-explored. For example, research suggests that Millennial women may place greater emphasis on role clarity and supervisor support, while Baby Boomer men appear to be more motivated by the meaningfulness of their work. However, the relative salience of these engagement drivers has not been comprehensively analyzed across all generational cohorts and gender groups.

To address these gaps, the current study aims to provide a more nuanced, age- and gender-specific understanding of the key drivers of employee engagement. By analyzing survey data from over 500 U.S. employees, this research evaluates the relative influence of traditional predictors like basic needs fulfillment alongside evolving constructs like "worker activation" - discretionary commitments nurtured through empowering organizational cultures (Westover & Andrade, 2024). Importantly, the study examines these engagement dynamics separately for each generational cohort (Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z) and by gender, providing critical insights into the unique predictors of engagement across age and gender groups.

Overall, the findings aim to provide strategic direction for organizations seeking to optimize engagement and discretionary effort within their multigenerational, gender-diverse workforces. Understanding the distinct engagement drivers for different generational and gender groups can inform the development of tailored, workforce-responsive strategies to foster commitment, performance, and well-being.

Literature Review

Overview of Employee Engagement

Employee engagement refers to the level of an employee's emotional commitment, enthusiasm, and passion for their work (Harter et al., 2009). Highly engaged employees exhibit a strong sense of purpose, a willingness to go "above and beyond" in their roles, and a deep connection to the organization's mission and values (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). In contrast, disengaged workers lack motivation, show reduced productivity, and have a higher propensity for turnover (Macey & Schneider, 2008).

Employee engagement is critical for organizational success, as engaged employees are emotionally committed to their work and the organization, demonstrating high levels of enthusiasm, dedication, and discretionary effort (Gallup, 2022; Kahn, 1990). Disengaged employees, on the other hand, are physically present but psychologically absent, contributing minimally to organizational goals (Kahn, 1990; Macey & Schneider, 2008).

Scholars have conceptualized employee engagement as a multifaceted construct involving cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components (Kahn, 1990; Schaufeli et al., 2002; Shuck & Wollard, 2010). Kahn (1990) defined engagement as the "harnessing of organization members' selves to their work roles," while Schaufeli et al. (2002) described it as a "positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind" characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption.

Several theoretical frameworks have been used to explain the drivers and processes underlying employee engagement, including the job demands-resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., 2001; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004), the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989), the social exchange theory (SET) (Blau, 1964), and the self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Researchers have identified a range of individual, job-related, and organizational factors that contribute to employee engagement, such as personality traits, job characteristics, organizational support, and work-life balance (Bakker et al., 2012; Christian et al., 2011; Saks, 2006). Engagement has been linked to positive individual and organizational outcomes, including higher job satisfaction, performance, and financial success (Halbesleben, 2010; Harter et al., 2002).

Additionally, various instruments, such as the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES), the Gallup Q12, and the Intellectual, Social, and Affective Engagement Scale (ISA), have been developed to measure and assess employee engagement (Schaufeli et al., 2002; Rich et al., 2010). The measurement and assessment of engagement can be influenced by contextual factors, requiring careful consideration of the appropriate tools for a given organizational context (Albrecht, 2010; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004).

Key Determinants of Employee Engagement

Employee engagement has emerged as a critical factor for organizational success, with extensive research highlighting its impact on various outcomes (Kahn, 1990; Saks, 2006). This literature review provides an overview of the key determinants of employee engagement, drawing from existing theoretical frameworks and empirical studies.

At the foundational level, employee engagement is influenced by the fulfillment of basic needs, as outlined in Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs (Maslow, 1943). Employees require their physiological, safety, and belongingness needs to be met in order to be engaged (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004).

Beyond basic needs, individual factors also play a significant role in shaping engagement. These include personality traits, psychological states, and personal resources (Bakker et al., 2014; Christian et al., 2011; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

The work environment, particularly the quality of interpersonal relationships and team dynamics, can also influence engagement. Factors such as social support, team cohesion, and collaborative climate are associated with higher engagement levels (Breevaart et al., 2014; Kahn, 1990; Saks, 2006).

Opportunities for growth and development are crucial in fostering employee engagement. Employees are more engaged when their jobs provide autonomy, skill variety, task significance, and feedback, as well as opportunities for learning and perceived meaningfulness (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Kahn, 1990).

Finally, the degree to which employees are "activated" or empowered in their work roles can also impact engagement. Factors such as autonomy, role clarity, and feedback and recognition are positively associated with engagement (Christian et al., 2011; Kahn, 1990; Saks, 2006).

By understanding these multifaceted determinants of employee engagement, organizations can develop strategies to foster a highly engaged workforce, leading to improved organizational performance and outcomes.

Generational Differences in Employee Engagement

Over the past two decades, employee engagement has become an increasingly important topic in organizational research and practice (Gallup, 2022; Kahn, 1990). Engaged employees are emotionally committed to their work and organization, and demonstrate high levels of enthusiasm, dedication, and discretionary effort. Engagement has been linked to a variety of positive individual and organizational outcomes, including increased productivity, customer satisfaction, and financial performance (Harter et al., 2002; Saks, 2006).

As the workforce becomes more diverse, with multiple generations working side-by-side, there is growing interest in understanding how generational differences may influence employee engagement (Becton et al., 2014; Costanza & Finkelstein, 2015). Generational cohorts are typically defined as groups of individuals born within a similar time period, who share common experiences, values, and attitudes shaped by the social, economic, and political events of their formative years (Mannheim, 1952; Parry & Urwin, 2011). The most commonly recognized generational cohorts in the current workforce include Baby Boomers (born 1946-1964), Generation X (born 1965-1980), Millennials (born 1981-1996), and Generation Z (born 1997-2012) (Gallup, 2022; Pew Research Center, 2019).

Several theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain the origins and dynamics of generational differences in the workplace. The generational theory, developed by Strauss and Howe (1991), posits that generations are shaped by a cyclical pattern of social, economic, and political events. The life-stage theory suggests that differences are primarily driven by the stage of life and career development, rather than unique historical experiences (Schaie, 1965; Super, 1957). The socialization theory emphasizes the role of cultural and social influences in shaping generational differences (Mannheim, 1952; Parry & Urwin, 2011).

The existing literature on generational differences in employee engagement has produced mixed and sometimes contradictory findings (Becton et al., 2014; Costanza & Finkelstein, 2015). Researchers have identified several factors that may contribute to these differences, including work values, career expectations, management preferences, and work-life balance needs (Costanza & Finkelstein, 2015; Twenge et al., 2010). Organizational factors, such as culture, HR practices, and leadership styles, can also play a significant role in shaping generational differences in employee engagement (Costanza & Finkelstein, 2015).

Gender Differences in Employee Engagement

Recent research paints a nuanced picture of gender differences in employee engagement. A global survey found that women generally report higher levels of engagement than men, exhibiting greater commitment, enthusiasm, and positive impact within their organizations (Frumar & Truscott-Smith, 2024). This pattern holds true for women in project management, managerial, and individual contributor roles.

However, the gender engagement gap reverses at the senior leadership level, where women are less engaged than their male counterparts. This may be attributed to factors like isolation, lack of emotional support, and the absence of close relationships that tend to characterize senior-level positions, leading women to stay in these roles for shorter durations (Frumar & Truscott-Smith, 2024).

Occupational self-efficacy also plays a role, with studies showing that men have higher career aspirations even when their self-efficacy is on par with women's (Hartman & Barber, 2020). Women, particularly those with low or moderate self-efficacy, may benefit from coaching, mentoring, and career development support to overcome this barrier.

The relationship between gender and engagement is also context-dependent. While some studies found no differences between men and women in certain work settings, others reported men experiencing higher engagement, commitment, and inclusion in roles like IT in India (Mulaudzi & Takawira, 2015; Sharma et al., 2017; Nobles, 2023; Zoe Talent Solutions, 2024).

To address these disparities, organizations can implement strategies like flexible work arrangements, leadership opportunities, mentorship, networking groups, and inclusive language training to support women's engagement and advancement, particularly in senior roles (Frumar & Truscott-Smith, 2024). Fostering a diverse organizational climate and strong team relationships can also help counter the isolation that women may face at the top.

Hypotheses

The existing literature on generational and gender differences in employee engagement has produced mixed findings, with limited understanding of how basic needs, individual determinants, teamwork factors, and growth aspects impact engagement for different age cohorts and between men and women. Research suggests younger generations and women may place greater emphasis on factors like role clarity, supervisor support, and teamwork, while older cohorts and men may be more motivated by the meaningfulness of their work and individual growth opportunities. However, the relative salience of these engagement predictors across generations and genders remains underexplored. Investigating the combined effects of generational and gender differences on the drivers of employee engagement can inform the development of tailored, responsive strategies to foster commitment, performance, and well-being across an organization's diverse workforce.

To address these gaps in the literature, we propose the following hypotheses to examine potential variations in the drivers of employee engagement across generational cohorts and by gender:

Hypothesis 1: Employee engagement levels will differ significantly between generational cohorts and gender groups.

Hypothesis 2a: The influence of basic needs and individual contribution variables on employee engagement will vary across generational cohorts and gender.

Hypothesis 2b: Basic needs determinants will be more salient in predicting engagement for younger generations (e.g., Millennials, Gen Z) compared to older cohorts, and for women compared to men.

Hypothesis 2c: Individual determinants will be more salient in predicting engagement for older generations (e.g., Baby Boomers, Gen X) compared to younger cohorts, and for men compared to women.

Hypothesis 3: Teamwork determinants will be more salient in predicting employee engagement for younger generations (e.g., Millennials, Gen Z) than older cohorts, and for women compared to men.

Hypothesis 4: Growth determinants will be more salient in predicting employee engagement for older generations (e.g., Baby Boomers, Gen X) than younger cohorts, and for men compared to women.

Hypothesis 5: Worker activation determinants will be more salient in predicting employee engagement for younger generations (e.g., Millennials, Gen Z) than older cohorts, and for women compared to men.

By testing these hypotheses, the study aims to provide a more nuanced, age- and gender-specific understanding of the key drivers of employee engagement. This knowledge can inform the development of tailored, generationally- and gender-responsive strategies to foster commitment, performance, and well-being across an organization's diverse workforce.

Research Model and Design

Drawing on prominent employee engagement frameworks, we developed a comprehensive online survey to investigate the evolving dynamics of the modern workplace. The questionnaire explored a range of factors, including basic needs, individual contributions, teamwork dynamics, growth opportunities, and employee activation. Using a stratified random sampling approach across the United States, we collected a final dataset of 566 employee responses, providing a reliable and generalizable snapshot of the contemporary work experience. By blending insights from seminal and more recent engagement research, the survey design allowed us to obtain a holistic understanding of the multifaceted influences on employee attitudes and behaviors in today's rapidly changing work environment.

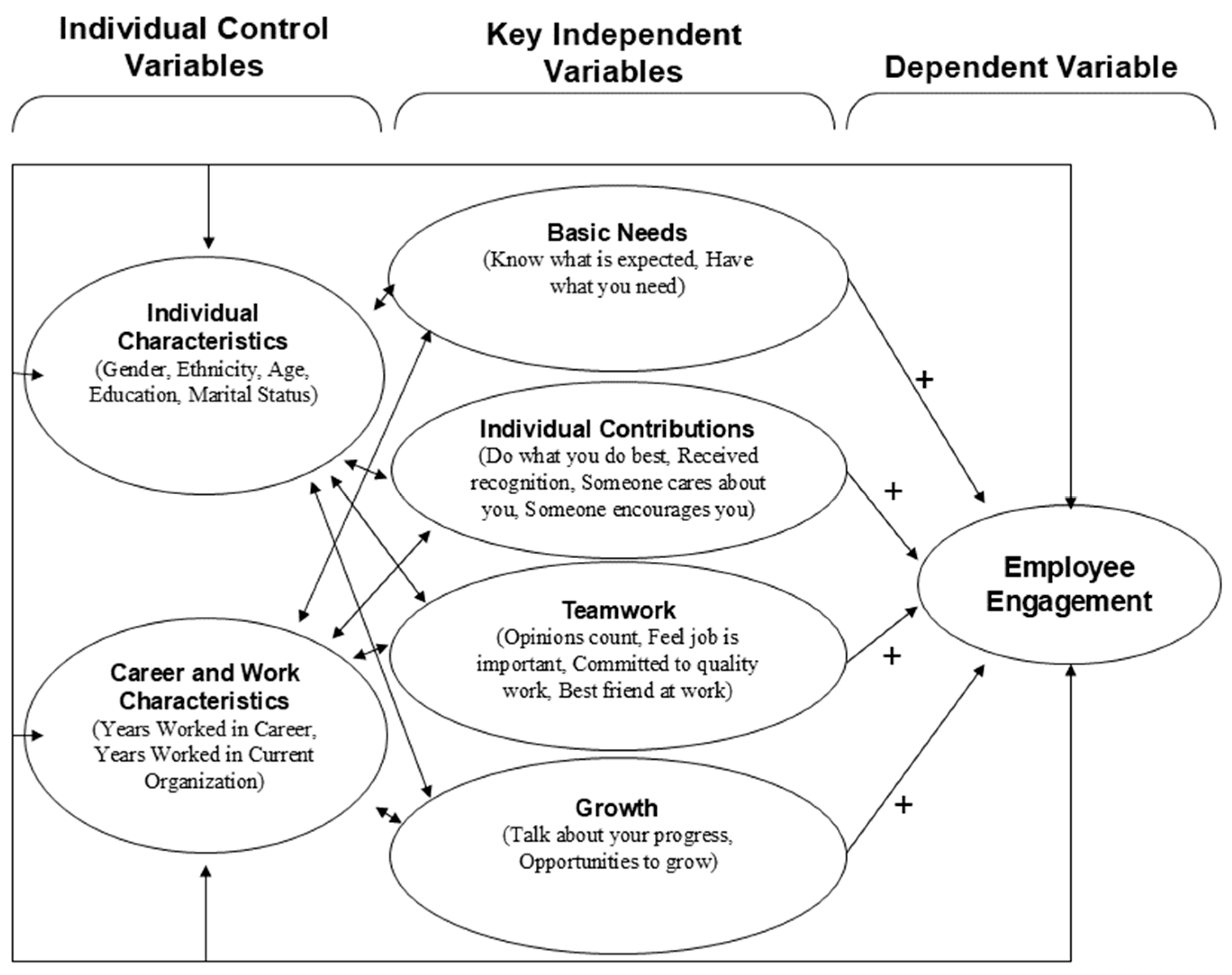

Figure 1.

RESEARCH MODEL.

Figure 1.

RESEARCH MODEL.

Operationalization of Variables

We operationalized the study variables according to the approach of Harter et al. (2009) and added new survey questions, which allowed us to introduce additional variables in the analysis. See

Table 1 below.

Statistical Methodology

The analysis employed a multi-stage approach to examine the relationship between employee engagement and various workplace factors across generational cohorts and gender. First, we conducted preliminary and descriptive analyses of worker engagement and activation variables for the full sample, as well as by generational group (e.g., Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, Generation Z) and gender.

This initial step provided insights into potential differences in engagement and activation levels between the age cohorts and between men and women. Next, we tested for statistically significant differences in employee engagement across the generational groups and between genders using t-test analyses (Hypothesis 1). This allowed us to determine if engagement levels differed significantly between the various age cohorts and between men and women.

Building on these initial findings, we then examined generational- and gender-specific OLS and ordered probit regression models to evaluate the relative contribution of employee basic needs, individual contributions, teamwork, and growth factors on engagement for each age and gender group (Hypotheses 2a-2c, 3, 4). This analysis shed light on how the salience of these engagement determinants varied across the different generational cohorts and between men and women.

Finally, we tested for statistically significant differences between the generational groups and between genders in the impact of worker activation dimensions (purposeful work, sense of belonging, leadership efficacy, organizational commitment) on employee engagement using moderation analyses (Hypotheses 5a-5d). This allowed us to identify any generational and gender nuances in how these activation-related factors shaped discretionary effort.

By employing this multi-stage analytical approach, we were able to provide a comprehensive, age- and gender-specific understanding of the key drivers of employee engagement. The combination of descriptive, comparative, and regression-based techniques enabled us to uncover both the overarching patterns as well as the nuanced, generational and gender variations in what inspires discretionary effort across the workforce.

Results

Participant Demographics

The study's sample consisted of 566 respondents with diverse demographic characteristics. The majority of participants identified as White (67.67%), followed by Black or African American (19.96%) and Asian (9.72%), with smaller proportions identifying as Native American/Alaska Native (0.35%), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (0.71%), and Other (1.59%). In terms of education level, the largest group had a bachelor's degree (34.10%), followed by some college but no degree (26.11%), a high school diploma (17.05%), a master's degree (17.23%), and a doctoral degree (4.44%). Only 1.07% had less than a high school education. Regarding ethnicity, the majority of respondents (88.34%) indicated they were not of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin, while 11.66% did identify as such. For marital status, most participants were married or cohabitating (62.70%), with 36.59% reporting they were single, and a small percentage (0.71%) preferring not to disclose their marital status. The gender breakdown of the sample was 53.89% female and 46.11% male. In terms of generation, the largest group was Gen X (34.10%), followed by Millennials (33.00%), Baby Boomers (23.00%), and Gen Z (9.80%). The mean birth year of respondents was 1977.34 (SD = 13.99), and on average they had worked 20.57 years (SD = 13.92) in their career and 13.94 years (SD = 86.29) in their current organization. Overall, the sample represented a diverse set of participants in terms of race, education, ethnicity, marital status, gender, and generation, providing a robust foundation for the study's findings.

Table 2.

PARTICPANT DEMOGRAPHICS.

Table 2.

PARTICPANT DEMOGRAPHICS.

| Race of Respondent |

Freq. |

Percent |

| White |

383 |

67.67 |

| Black or African American |

113 |

19.96 |

| Asian |

55 |

9.72 |

| Native American or Alaska Native |

2 |

0.35 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

4 |

0.71 |

| Other |

9 |

1.59 |

| Total |

566 |

100 |

| Education Level of Respondent |

Freq. |

Percent |

| Less than high school |

6 |

1.07 |

| High school diploma |

96 |

17.05 |

| Some college, but no degree |

147 |

26.11 |

| Bachelor's degree |

192 |

34.1 |

| Master's degree |

97 |

17.23 |

| Doctoral degree |

25 |

4.44 |

| Total |

563 |

100 |

| Ethnicity of Respondent |

Freq. |

Percent |

| Hispanic or Latino or Spanish Origin |

66 |

11.66 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino or Spanish Origin |

500 |

88.34 |

| Total |

566 |

100 |

| Marital Status of Respondent |

Freq. |

Percent |

| Married or cohabitating |

353 |

62.7 |

| Single |

206 |

36.59 |

| Prefer not to say |

4 |

0.71 |

| Total |

563 |

100 |

| Gender of Respondent |

Freq. |

Percent |

| Female |

305 |

53.89 |

| Male |

261 |

46.11 |

| Total |

566 |

100 |

| Generation of Respondent |

Freq. |

Percent |

| Baby Boomer |

129 |

23.0% |

| Gen X |

191 |

34.1% |

| Millennial |

185 |

33.0% |

| Gen Z |

55 |

9.8% |

| Total |

560 |

100 |

| Other Demographic Variables |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

| Birth year |

1977.34 |

13.99 |

| Full-time years worked in career |

20.57 |

13.92 |

| Years worked in current organization |

13.94 |

86.29 |

Descriptive Results

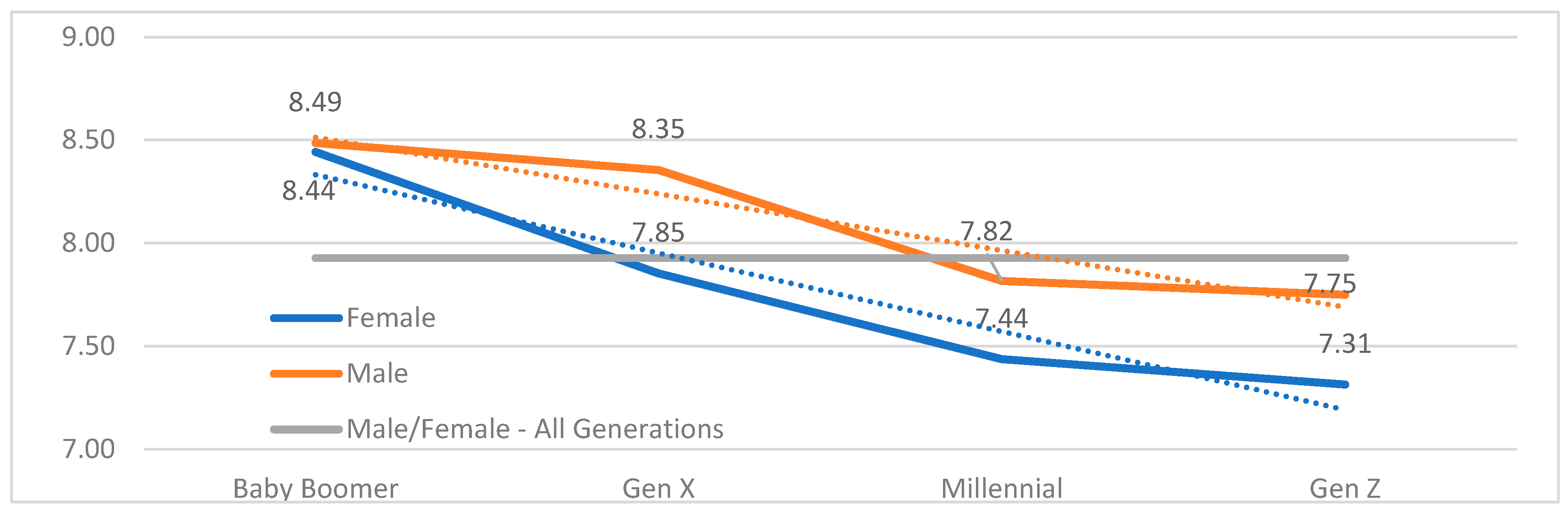

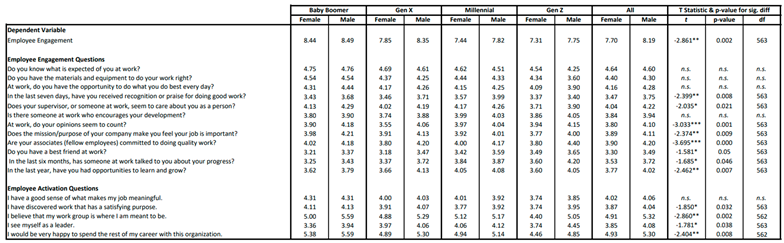

The data presented in

Table 3 reveals significant generational and gender differences in employee engagement and activation within the organization. Examining overall engagement levels, Baby Boomers stand out as the most engaged, with average scores of 8.44 for women and 8.49 for men. This is followed by Gen X (7.85 for women, 8.35 for men), Millennials (7.44 for women, 7.82 for men), and Gen Z (7.31 for women, 7.75 for men). These differences in engagement across the generational cohorts are statistically significant, indicating that employee engagement declines as we move from older to younger generations.

Looking within each generation, there is also a clear gender gap, with men exhibiting higher levels of engagement than their female counterparts. This gender disparity is statistically significant, with men scoring 8.19 on average compared to 7.70 for women overall.

Delving deeper into the subdimensions of engagement, the data shows no notable generational or gender differences in the more basic elements, such as role clarity, access to necessary resources, and opportunities to leverage one's strengths. However, distinct patterns emerge in areas like recognition, supervisor support, having one's opinions valued, and perceiving the organization's mission as important. In these facets, Baby Boomers and men consistently report more positive experiences than younger generations and women, respectively.

A similar trend is observed in the employee activation measures. Baby Boomers and men exhibit a stronger sense of purpose, belonging, leadership efficacy, and organizational commitment compared to other generational cohorts and women. These gaps in worker activation are also statistically significant.

Figure 2.

MEAN EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT, BY GENERATION & GENDER.

Figure 2.

MEAN EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT, BY GENERATION & GENDER.

The findings from this analysis suggest that organizations should consider implementing tailored engagement strategies to address the diverse needs and perspectives of their multigenerational and gender-diverse workforce. Adopting a more nuanced, demographic-specific approach may be key to enhancing engagement and retention across the organization.

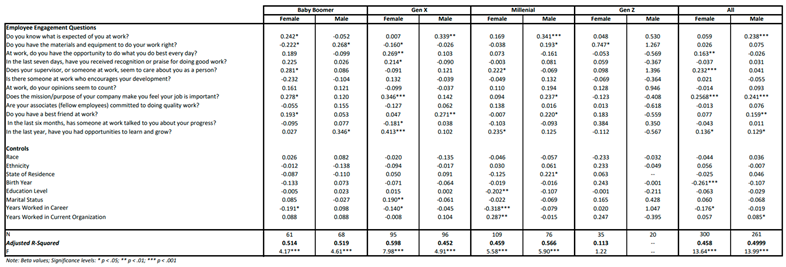

Regression Results

Building on the work of Harter et al. (2009), we conducted a series of regression analyses to examine the relationship between employee engagement and a range of independent variables. The initial model (

Table 4) explored the impact of factors like basic needs, individual contributions, teamwork, growth opportunities, and control variables on engagement, analyzing the results by gender and geographic location. In the second model (

Table 5), we expanded the analysis to consider the combined effect of all control and independent variables on engagement. Importantly, we also incorporated a set of "employee activation" variables for each gender, location, and the overall sample. The inclusion of these activation factors led to many variables from the first model becoming non-significant.

As a result, the final model (

Table 6) focuses solely on the most impactful engagement and activation variables, which we believe represents the optimal predictive framework. This parsimonious yet comprehensive model allows us to identify the key drivers of employee engagement across the organization. By taking this stepwise approach and progressively refining the regression analyses, we were able to isolate the most salient factors influencing engagement within this workforce. This data-driven process enabled us to develop what we consider to be the "best" model for understanding and promoting employee engagement in the context of this study.

Model 1: Original Employee Engagement Model

In

Table 4, the results offer valuable insights into the antecedents of engagement for each generation, by gender. The regression analysis confirms the significant generational and gender disparities in employee engagement observed in the previous analysis. Among Baby Boomers, being female is associated with higher engagement on several subdimensions, including knowing role expectations (β=0.242, p<0.05), having the necessary materials (β=-0.222, p<0.05), and having a best friend at work (β=0.193, p<0.05). In contrast, for Generation X, being female is negatively related to having the necessary materials (β=-0.160, p<0.05) and receiving progress feedback (β=-0.181, p<0.05). For Millennials, being female is positively linked to supervisor support (β=0.222, p<0.05) and opportunities for learning and growth (β=0.235, p<0.05). Across generations, men generally report higher engagement in areas like role clarity, mission/purpose, and having a best friend at work.

The regression models also controlled for various demographic factors. Notably, higher education levels are negatively associated with engagement for Millennial women (β=-0.202, p<0.01). Longer tenure in one's career is also negatively related to engagement for Baby Boomer women (β=-0.191, p<0.05) and Gen X women (β=-0.140, p<0.05), while longer tenure in the current organization is positively linked to engagement for Millennial women (β=0.287, p<0.01) and men (β=0.085, p<0.05).

The regression models demonstrate strong explanatory power, with adjusted R-squared values ranging from 0.452 to 0.598 for the generational cohorts. The overall models are statistically significant, with F-statistics significant at the p<0.001 level, indicating that the included variables can account for a substantial portion of the variance in employee engagement within each generational group. These findings underscore the importance of tailoring engagement strategies to address the unique needs and experiences of a diverse, multigenerational workforce.

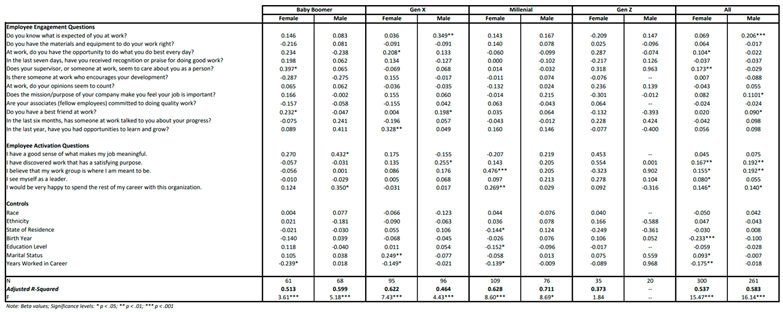

Model 2: Revised Employee Engagement Model

The revised regression analysis presented in

Table 5 provides a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing employee engagement across different generational cohorts, by gender. The regression results in this revised model continue to reveal significant generational and gender disparities in employee engagement. Among Baby Boomers, being female is positively associated with having the opportunity to do what they do best every day (β=0.234, p<0.10) and having a best friend at work (β=0.232, p<0.05). In contrast, for Generation X, being female is negatively related to having the necessary materials and equipment (β=-0.091, p<0.10) and receiving progress feedback (β=-0.196, p<0.10). For Millennials, being female is negatively linked to having opportunities to learn and grow (β=0.160, p<0.10). Demographic factors also play a role, as longer tenure in one's career is negatively associated with engagement for Baby Boomer women (β=-0.239, p<0.05), Gen X women (β=-0.149, p<0.05), and Millennial women (β=-0.139, p<0.05), while higher education levels are also negatively related to engagement for Millennial women (β=-0.152, p<0.05). Interestingly, being married is positively linked to engagement for Gen X women (β=0.249, p<0.01).

The regression analysis also examined employee activation, revealing further generational and gender differences. Baby Boomer men report a stronger sense of what makes their job meaningful (β=0.432, p<0.05) and higher organizational commitment (β=0.350, p<0.05). Gen X men exhibit a greater sense of purpose (β=0.255, p<0.05) and belief that their work group is where they are meant to be (β=0.176, p<0.10). Millennial women, on the other hand, have a stronger belief that their work group is where they are meant to be (β=0.476, p<0.001) and higher organizational commitment (β=0.269, p<0.01).

The regression models demonstrate strong explanatory power, with adjusted R-squared values ranging from 0.373 to 0.711 for the generational cohorts. The overall models are statistically significant, with F-statistics significant at the p<0.001 level, indicating that the included variables can account for a substantial portion of the variance in both employee engagement and activation within each generational group. These findings highlight the importance of implementing tailored strategies to address the diverse needs and experiences of a multigenerational workforce.

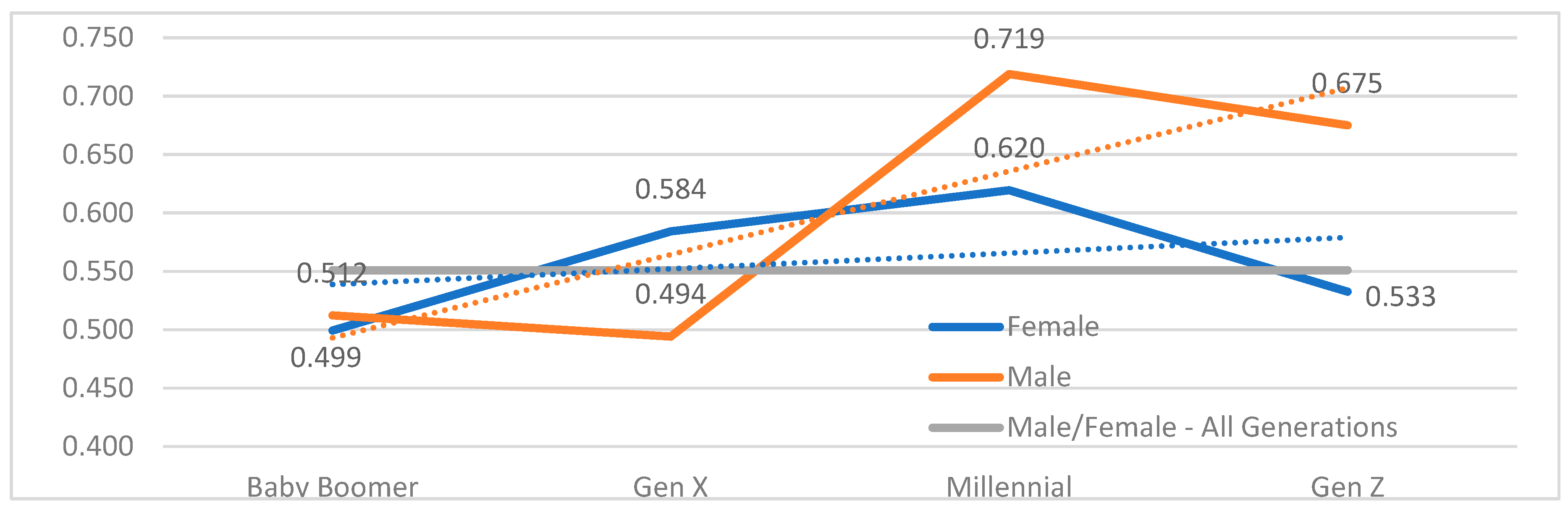

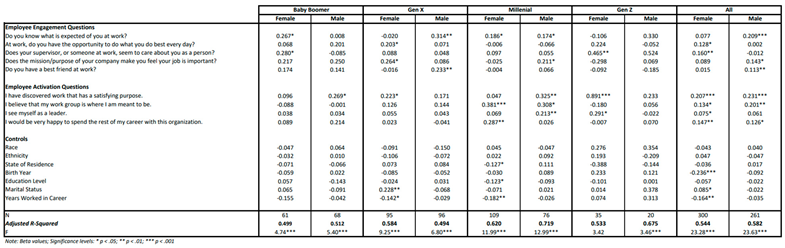

Model 3: Best Employee Engagement Model

Finally, as seen in

Table 6 below, we took the most impactful engagement and activation variables from the last model, combined with our control variables, to create our model of best fit. Among Baby Boomers, being female is positively associated with knowing what is expected at work (β=0.267, p<0.05) and having a supervisor who seems to care about them as a person (β=0.280, p<0.05). For Generation X, being female is positively related to having the opportunity to do what they do best every day (β=0.203, p<0.05) and feeling the company's mission/purpose makes their job feel important (β=0.264, p<0.05). For Millennials, being female is positively linked to knowing what is expected at work (β=0.186, p<0.05) and having a supervisor who seems to care about them as a person (β=0.465, p<0.01). Demographic factors also play a role, as longer tenure in one's career is negatively associated with engagement for Gen X women (β=-0.142, p<0.05) and Millennial women (β=-0.182, p<0.01), while being married is positively linked to engagement for Gen X women (β=0.228, p<0.01).

The regression analysis also examined employee activation, revealing further generational and gender differences. Baby Boomer men report a stronger sense of purpose in their work (β=0.269, p<0.05). Gen X men exhibit a greater belief that their work group is where they are meant to be (β=0.144, p<0.10) and see themselves as leaders (β=0.213, p<0.01). Millennial women have a stronger belief that their work group is where they are meant to be (β=0.381, p<0.001) and higher organizational commitment (β=0.287, p<0.01). Millennial men show a greater sense of purpose (β=0.325, p<0.01) and see themselves as leaders (β=0.213, p<0.01).

As seen in

Figure 3 below, the regression models demonstrate strong explanatory power, with adjusted R-squared values ranging from 0.494 to 0.719 for the generational cohorts. The overall models are statistically significant, with F-statistics significant at the p<0.001 level, indicating that the included variables can account for a substantial portion of the variance in both employee engagement and activation within each generational group. These findings highlight the importance of implementing tailored strategies to address the diverse needs and experiences of a multigenerational workforce.

Variations in Model Fit—Why it Matters

The substantial variations in adjusted R-squared values across the generational and gender-specific regression models highlight the critical value of taking a nuanced, age- and gender-specific approach to understanding and promoting employee engagement. The findings clearly demonstrate that the key drivers of engagement can differ markedly not only between generational cohorts, but also within them based on gender.

By recognizing these nuanced generational and gender differences in what motivates and fulfills workers, organizations can develop far more effective, tailored strategies to foster commitment and performance across their multigenerational workforce. A one-size-fits-all approach to engagement is unlikely to be optimally effective given the diverse needs and preferences of employees at different life and career stages, as well as the unique priorities and psychological needs of men and women within each generation.

For example, the analysis revealed that discovery of meaningful, purposeful work was a particularly strong engagement driver for Baby Boomer and Generation Z men, while a sense of belonging to one's work group was most salient for Millennial women. Likewise, supervisor support emerged as exceptionally important for engaging Generation Z employees, with the effect being more pronounced for women. Clearly, the specific factors that cultivate high engagement vary considerably based on the employee's generational background and gender.

Organizations that tailor their engagement initiatives accordingly, perhaps offering a suite of options to accommodate diverse generational and gender preferences, are far more likely to effectively inspire commitment, productivity, and well-being across their multigenerational workforce. This may involve anything from restructuring recognition and rewards programs, to enhancing opportunities for skill development and growth, to fostering more personalized manager-employee relationships.

By deeply understanding the unique engagement determinants for each generational and gender cohort, companies can make strategic, data-driven investments in their human capital that maximize returns in the form of elevated performance, reduced turnover, and stronger organizational culture. This nuanced, intersectional approach represents a crucial competitive advantage in today's dynamic, multigenerational work environments.

The substantial variations in explanatory power across the age- and gender-specific regression models underscores that a one-size-fits-all mentality is ill-advised when it comes to fostering employee engagement. Organizations that recognize and respond to the nuanced generational and gender differences in work motivation and fulfillment will be best positioned to cultivate a highly engaged, high-performing, and resilient multigenerational workforce.

Revisting Hypotheses

The research findings allow us to evaluate the hypotheses proposed at the outset of the study:

Hypothesis 1: The results supported this hypothesis. The data revealed significant differences in employee engagement levels across the generational cohorts, with Baby Boomers reporting the highest levels of engagement, followed by Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z. Similarly, gender differences were observed, with men generally exhibiting higher engagement levels than women, except for at the senior leadership level where the trend reversed.

Hypothesis 2a: The findings supported this hypothesis. The regression analyses demonstrated that the relative importance of basic needs and individual contribution factors in predicting employee engagement differed significantly across the generational cohorts and between men and women.

Hypothesis 2b: This hypothesis was partially supported. The results indicated that basic needs determinants were indeed more predictive of engagement for the younger generations (Millennials and Generation Z) compared to the older cohorts (Baby Boomers and Generation X). However, the gender differences were less pronounced, with basic needs factors being similarly important for both men and women in shaping engagement.

Hypothesis 2c: This hypothesis was supported by the findings. The regression models showed that individual determinants, such as sense of meaning and purpose, were more influential in predicting engagement for the older generational cohorts (Baby Boomers and Generation X) compared to the younger generations (Millennials and Generation Z). Additionally, individual factors were more salient for men in comparison to women.

Hypothesis 3: The results partially supported this hypothesis. Teamwork factors were indeed more predictive of engagement for the younger generations (Millennials and Generation Z) compared to the older cohorts. However, the gender differences were not as pronounced, with teamwork determinants being similarly important for both men and women in shaping engagement.

Hypothesis 4: This hypothesis was supported by the findings. The regression analyses indicated that growth factors, such as opportunities for learning and development, were more influential in predicting engagement for the older generational cohorts (Baby Boomers and Generation X) compared to the younger generations (Millennials and Generation Z). Additionally, growth determinants were more salient for men than for women in shaping engagement.

Hypothesis 5: This hypothesis was partially supported. The results showed that worker activation factors, such as purposeful work, sense of belonging, and organizational commitment, were more predictive of engagement for the younger generations (Millennials and Generation Z) compared to the older cohorts. However, the gender differences were less pronounced, with worker activation determinants being similarly important for both men and women in shaping engagement.

Overall, the findings largely supported the study's hypotheses, revealing significant generational and gender-specific differences in the drivers of employee engagement. These insights can inform the development of tailored, workforce-responsive strategies to foster commitment, performance, and well-being across an organization's diverse employee base.

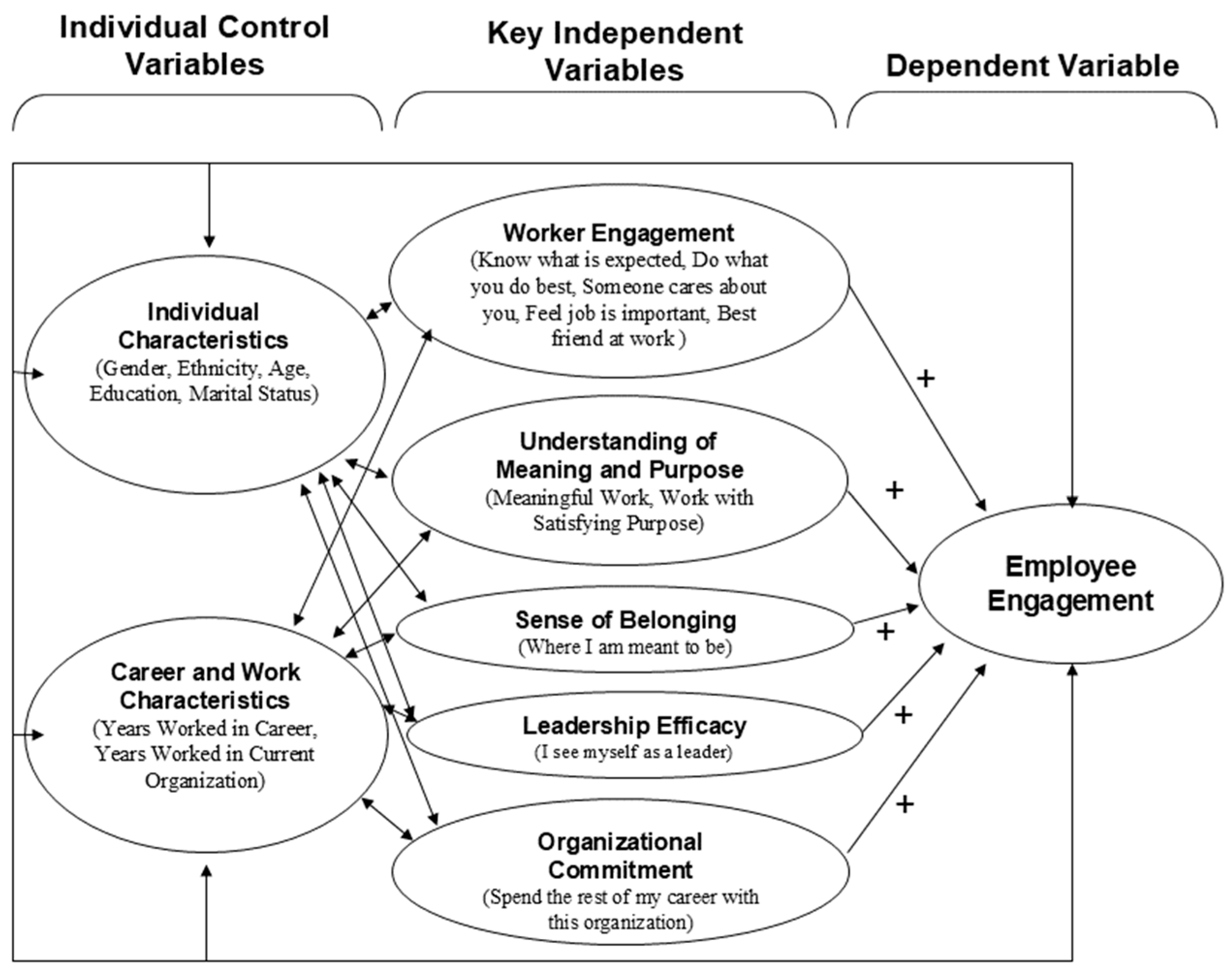

A Revised Employee Engagement Model

The initial conceptual framework and associated hypotheses presented in

Figure 1 only partially captured the complex relationships uncovered in this study between employee engagement, generational cohort, and key workplace factors. While traditional determinants like basic needs fulfillment, individual contributions, teamwork, and growth opportunities maintained relevance, the prominent influence of the worker activation constructs necessitated an update to the conceptualization.

The revised conceptual framework shown in

Figure 4 incorporates insights from the research on generational differences in engagement drivers. Notably, it positions the worker activation dimensions - including purposeful work, sense of belonging, leadership efficacy, and organizational commitment - as core influencers of employee engagement, rather than separate supplementary predictors. By conceptualizing worker activation as a multidimensional construct composed of these factors, the updated model provides a more robust and comprehensive perspective for understanding engagement across diverse generational cohorts. This refined view recognizes the central role of worker activation in driving engagement, particularly given the evolving nature of work and shifting organizational norms.

Placing worker activation at the core of the model acknowledges research demonstrating that employee engagement is influenced more by the discretionary commitment cultivated through inclusive, empowering corporate cultures, rather than solely by the fulfillment of basic expectations. The updated framework further underscores the vital importance of activation in motivating discretionary effort across all age groups to achieve optimal outcomes for both individuals and organizations.

Crucially, the revised conceptual model accounts for potential variations in the salience of activation determinants based on the employee's generational background. For example, a strong sense of belonging may be a particularly potent engagement driver for Millennials, while purposeful work could be more influential for Baby Boomers. By incorporating these generational nuances, the updated framework provides a more holistic understanding of the multifaceted factors shaping engagement in today's multigenerational workforce.

This revised conceptual model presents new opportunities for maximizing diverse and thriving workforces through customized approaches tailored to nurturing high activation among employees of all ages. Rather than a fixed state, engagement may depend on specific generational contexts and be shaped not just by individual attributes, but also by strategically designed workplace experiences that adapt to evolving organizational and societal norms. This perspective can guide future theory development and ongoing study of employee engagement across different age cohorts.

Discussion

The findings from this comprehensive study contribute to the growing body of research on employee engagement by providing a more nuanced, age- and gender-specific understanding of the key drivers of discretionary effort in the workplace. The results offer several important insights that can inform organizational strategies and HR practices to optimize engagement and performance across diverse generational and gender groups.

One of the key takeaways is the significant differences observed in employee engagement levels between the generational cohorts and between men and women. Consistent with previous research, Baby Boomers reported the highest levels of engagement, followed by Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z (Costanza & Finkelstein, 2015). This pattern may be attributed to factors such as differing work values, career expectations, and life-stage considerations across the age groups (Parry & Urwin, 2011; Twenge et al., 2010). The gender differences, with men generally exhibiting higher engagement levels than women except at the senior leadership level, align with recent global surveys and may be linked to issues like isolation, lack of emotional support, and the absence of close relationships that can characterize top-level roles for women (Frumar & Truscott-Smith, 2024).

The study's regression analyses provide deeper insights into how the relative influence of various engagement determinants varies across generations and between genders. Consistent with Hypothesis 2b, basic needs factors were more salient in predicting engagement for the younger cohorts (Millennials and Generation Z) compared to older generations, suggesting that fulfilling foundational physiological, safety, and belongingness needs is particularly important for driving discretionary effort among younger workers. This finding aligns with life-stage theory, which posits that younger employees are more focused on satisfying basic needs early in their careers (Schaie, 1965; Super, 1957).

Interestingly, the gender differences in the importance of basic needs were less pronounced, with these factors being similarly predictive of engagement for both men and women. This contrasts with the hypothesis (2b) that basic needs would be more salient for women, and may indicate that the generational differences outweigh the gender-based variations in the relative influence of these foundational engagement drivers.

The results also supported the notion that individual determinants, such as sense of meaning and purpose, are more influential in shaping engagement for older generations (Baby Boomers and Generation X) compared to younger cohorts (Hypothesis 2c). This finding aligns with the life-stage theory, which suggests that as employees progress in their careers, they tend to place greater emphasis on intrinsic factors like the meaningfulness of their work (Schaie, 1965; Super, 1957). The gender differences were also in line with the hypothesis, with individual determinants being more salient for men than for women in predicting engagement.

Regarding teamwork factors, the results confirmed that these determinants are more predictive of engagement for the younger generations (Millennials and Generation Z) compared to older cohorts, as hypothesized (Hypothesis 3). This may be attributed to the greater emphasis that younger employees place on collaboration, social connections, and a positive work environment (Costanza & Finkelstein, 2015; Parry & Urwin, 2011). However, the gender differences in the influence of teamwork factors were less pronounced, suggesting that the generational variations may be more significant than the gender-based differences in this regard.

The findings also supported the hypothesis (4) that growth determinants, such as opportunities for learning and development, are more salient in predicting engagement for the older generations (Baby Boomers and Generation X) compared to younger cohorts. This aligns with the notion that as employees mature in their careers, they tend to prioritize opportunities for personal and professional growth (Schaie, 1965; Super, 1957). The gender differences were also in line with the hypothesis, with growth factors being more influential for men than for women in shaping engagement.

Regarding worker activation determinants, the results partially supported the hypothesis (5), indicating that these factors (e.g., purposeful work, sense of belonging, organizational commitment) are more predictive of engagement for the younger generations (Millennials and Generation Z) compared to older cohorts. This suggests that empowering, activating work environments may be particularly important for fostering discretionary effort among younger employees. However, the gender differences were less pronounced, with worker activation determinants being similarly important for both men and women in shaping engagement.

Practical Implications & Recommendations for Organizations & Workers

The implications of these findings are twofold. First, they underscore the need for organizations to adopt a more tailored, generationally- and gender-responsive approach to employee engagement initiatives. Strategies that effectively engage Baby Boomers and Generation X may not resonate as strongly with Millennials and Generation Z, and vice versa. Similarly, engagement drivers that motivate men may differ from those that are most salient for women, particularly at the senior leadership level.

Second, the insights gained from this study can inform the development of comprehensive, workforce-responsive engagement strategies that address the unique needs and preferences of an organization's multigenerational, gender-diverse employee base. By aligning engagement initiatives with the distinct drivers of discretionary effort across age and gender groups, organizations can foster stronger commitment, performance, and well-being throughout their diverse workforce.

Some potential strategies include:

Tailored onboarding and development programs that cater to the basic needs, individual growth aspirations, teamwork preferences, and activation requirements of different generational cohorts.

Flexible work arrangements, leadership opportunities, mentorship programs, and inclusive language training to support women's engagement and advancement, particularly in senior roles.

Emphasis on meaningful work, autonomy, and opportunities for continuous learning and development to engage older employees.

Collaborative work environments, strong team relationships, and clear communication of organizational purpose and values to foster engagement among younger generations.

Comprehensive employee listening and feedback mechanisms to capture the evolving needs and preferences of the multigenerational, gender-diverse workforce.

By adopting these generationally- and gender-responsive approaches, organizations can optimize employee engagement and discretionary effort, ultimately driving improved organizational performance and outcomes.

Overall, this study's findings underscore the importance of understanding the nuanced, age- and gender-specific determinants of employee engagement. By tailoring engagement strategies to the unique needs and preferences of an organization's diverse workforce, leaders and HR professionals can cultivate a highly committed, productive, and resilient employee base - a critical competitive advantage in today's rapidly evolving business landscape.

Limitations & Opportunities For Future Research

While this study offers valuable insights into the generational and gender-based differences in employee engagement drivers, it is important to acknowledge several limitations that provide opportunities for future research.

First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to make causal inferences about the relationships between the various engagement determinants and employee outcomes. Longitudinal research designs would allow for a deeper understanding of how these dynamics evolve over time, particularly as generational cohorts and gender representation in the workforce continue to shift.

Second, the data was collected from a sample of U.S. employees, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other cultural and geographical contexts. Replicating this study in different countries and regions would provide a more comprehensive, globally-representative understanding of generational and gender-based engagement patterns.

Third, the study focused on the main effects of generational cohorts and gender on engagement drivers, but did not explore potential interaction effects. It is possible that the influence of certain determinants may be amplified or diminished when considering the intersections between age and gender. Future research should investigate these more nuanced, interactive effects to uncover a richer, more holistic picture of engagement dynamics.

Fourth, the analysis was limited to the broad generational categories commonly used in organizational research (Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, Generation Z). While this approach aligns with established frameworks, it may overlook important within-group variations that could provide additional insights. Examining engagement drivers at a more granular, year-of-birth level may reveal more fine-grained differences across the generational spectrum.

Fifth, the study relied on self-reported survey data, which may be subject to common method bias and social desirability effects. Incorporating multi-source data, such as manager assessments, performance metrics, and objective organizational records, could enhance the validity and reliability of the findings.

Finally, the current study focused primarily on the main drivers of engagement, but did not explore potential mediating or moderating mechanisms that could help explain the observed generational and gender differences. Future research should investigate the underlying psychological, social, and organizational processes that shape engagement outcomes for different age and gender groups.

Despite these limitations, this study offers a strong foundation for continued exploration of generational and gender-based engagement dynamics. Opportunities for future research include:

Longitudinal investigations to examine the evolving nature of engagement drivers over time, particularly as workforce demographics continue to shift.

Cross-cultural studies to understand how cultural and national contexts may influence the generational and gender-based patterns observed in this research.

Intersectional analyses to uncover the interactive effects of age, gender, and other demographic factors on engagement determinants.

Granular, year-of-birth level examinations of generational differences to identify more nuanced variations within broad age cohorts.

Multi-source data collection and mixed-methods approaches to enhance the validity and depth of the findings.

Exploration of mediating and moderating mechanisms that can help explain the underlying processes shaping engagement outcomes for diverse generational and gender groups.

By addressing these limitations and pursuing these research directions, scholars can build upon the insights provided by this study to further advance the understanding of employee engagement in the context of an increasingly diverse, multigenerational workforce. These efforts can inform the development of tailored, evidence-based strategies to foster commitment, performance, and well-being across organizations.

Conclusion

This comprehensive study provides valuable insights into the generational and gender-based differences in the drivers of employee engagement. By analyzing survey data from over 500 U.S. employees, the research offers a nuanced understanding of how the relative influence of various engagement determinants varies across age cohorts and between men and women.

The findings reveal significant differences in engagement levels, with Baby Boomers reporting the highest levels, followed by Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z. Gender differences were also observed, with men generally exhibiting higher engagement than women, except at the senior leadership level where the trend reversed.

The regression analyses shed light on the distinct engagement drivers for different generational and gender groups. Basic needs factors, such as physiological and safety requirements, were more salient in predicting engagement for the younger cohorts (Millennials and Generation Z) compared to older generations. In contrast, individual determinants, like sense of meaning and purpose, were more influential for the older cohorts (Baby Boomers and Generation X) and for men compared to women.

Teamwork-related factors were more predictive of engagement for the younger generations (Millennials and Generation Z), while growth determinants, including opportunities for learning and development, were more important for the older cohorts (Baby Boomers and Generation X) and for men. Worker activation variables, such as purposeful work and organizational commitment, were more salient in shaping engagement for the younger generations compared to older cohorts, but exhibited similar importance for both men and women.

These findings underscore the need for organizations to adopt a more tailored, generationally- and gender-responsive approach to employee engagement initiatives. By aligning engagement strategies with the distinct drivers of discretionary effort across age and gender groups, leaders and HR professionals can foster stronger commitment, performance, and well-being throughout their diverse workforce.

Potential strategies include tailored onboarding and development programs, flexible work arrangements and inclusive leadership opportunities for women, emphasis on meaningful work and continuous learning for older employees, and collaborative work environments and clear communication of organizational purpose for younger generations.

Future research directions include longitudinal investigations, cross-cultural studies, intersectional analyses, and the exploration of underlying mechanisms that shape engagement outcomes for diverse generational and gender groups. By building on the insights provided by this study, scholars can continue to advance the understanding of employee engagement in the context of an increasingly diverse, multigenerational workforce.

Overall, this research offers critical guidance for organizations seeking to optimize engagement and discretionary effort within their multigenerational, gender-diverse employee base - a strategic imperative for driving improved organizational performance and sustained competitive advantage in the modern business landscape.

References

- Agarwal, U. A. Linking justice, trust and innovative work behaviour to work engagement. Personnel Review 2014, 43(1), 41–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S. L. Handbook of employee engagement: Perspectives, issues, research and practice; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anitha, J. Determinants of employee engagement and their impact on employee performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2014, 63(3), 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International 2008, 13(3), 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. I. Burnout and work engagement: The JD-R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2014, 1(1), 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becton, J. B.; Walker, H. J.; Jones-Farmer, A. Generational differences in workplace behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2014, 44(3), 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. M. Exchange and power in social life; Wiley, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.; Hetland, J.; Demerouti, E.; Olsen, O. K.; Espevik, R. Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2014, 87(1), 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M. S.; Garza, A. S.; Slaughter, J. E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology 2011, 64(1), 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, D. P.; Finkelstein, L. M. Generationally based differences in the workplace: Is there a there there? Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2015, 8(3), 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, D. P.; Badger, J. M.; Fraser, R. L.; Severt, J. B.; Gade, P. A. Generational differences in work-related attitudes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology 2012, 27(4), 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M. S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management 2005, 31(6), 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A. B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumar, C.; Truscott-Smith, A. Women’s engagement advantage disappears in leadership roles. Gallup Workplace. 9 July 2024. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/646748/women-engagement-advantage-disappears-leadership-roles.aspx#:~:text=Despite%20women%20almost%20universally%20exhibiting,to%20lose%20star%20female%20employees.

- Gallup. 2022 State of the Global Workplace. 2022. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace.aspx.

- Hackman, J. R.; Oldham, G. R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 1976, 16(2), 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. Bakker, A. B., Leiter, M. P., Eds.; A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research; Psychology Press, 2010; pp. 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, J. K.; Schmidt, F. L.; Hayes, T. L. Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 2002, 87(2), 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, R. L.; Barber, E. G. Women in the workforce: The effect of gender on occupational self-efficacy, work engagement and career aspirations. Gender in Management 2020, 35(1), 92–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist 1989, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology 2001, 50(3), 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, S. E.; Nahrgang, J. D.; Morgeson, F. P. Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. Journal of Applied Psychology 2007, 92(5), 1332–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W. A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal 1990, 33(4), 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, W. H.; Schneider, B. The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2008, 1(1), 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, K. Kecskemeti, P., Ed.; The problem of generations. In Essays on the sociology of knowledge; Routledge, 1952; pp. 276–320. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. H. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 1943, 50(4), 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D. R.; Gilson, R. L.; Harter, L. M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2004, 77(1), 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobles, C. The gender inequality statistic you might not be tracking. Achievers. 7 February 2023. Available online: https://www.achievers.com/blog/gender-recognition-inequality/.

- Parry, E.; Urwin, P. Generational differences in work values: A review of theory and evidence. International Journal of Management Reviews 2011, 13(1), 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/.

- Rich, B. L.; Lepine, J. A.; Crawford, E. R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal 2010, 53(3), 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, A. L. Everyone wants an engaged workforce: How can you create it? Workspan 2006, 49(1), 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 2000, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A. M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2006, 21(7), 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Agut, S.; Peiró, J. M. Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. Journal of Applied Psychology 2005, 90(6), 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Goel, A.; Sengupta, S. How does work engagement vary with employee demography?:—Revelations from the Indian IT industry. Procedia Computer Science 122 2017, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaie, K. W. A general model for the study of developmental problems. Psychological Bulletin 1965, 64(2), 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Bakker, A. B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2004, 25(3), 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A. B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two-sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 2002, 3(1), 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuck, B.; Wollard, K. Employee engagement and HRD: A seminal review of the foundations. Human Resource Development Review 2010, 9(1), 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, W.; Howe, N. Generations: The history of America's future, 1584 to 2069; William Morrow & Company, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Super, D. E. The psychology of careers; Harper & Row, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J. M.; Campbell, S. M.; Hoffman, B. J.; Lance, C. E. Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. Journal of Management 2010, 36(5), 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Ferris, D. L.; Chang, C. H.; Rosen, C. C. A review of self-determination theory's basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Management 2016, 42(5), 1195–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cooper Thomas, H. How can leaders achieve high employee engagement? Leadership & Organization Development Journal 2011, 32(4), 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W. B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management 2007, 14(2), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westover, J. H.; Andrade, M. S. Examining the influence of employee activation on gender differences in employee engagement. Journal of Business Diversity 2024a, 24(3), 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solutions, Zoe Talent. Breakdown of male vs. female employee engagement statistics. Zoe Talent Solutions. 2024. Available online: https://zoetalentsolutions.com/male-vs-female-employee-engagement-statistics/#:~:text=Despite%20efforts%20for%20gender%20equality,only%2066%25%20of%20women%20do.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).