1. Introduction

Micro and small enterprises (MSMEs) are essential drivers of employment, economic dynamism, and cultural continuity, particularly in rural and culturally significant areas. In Mexico’s Agave Route—designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site—the legitimacy of business leadership cannot be reduced to formal authority or financial performance alone. Instead, it is anchored in ethical consistency, community rootedness, and narrative coherence. In such contexts, the entrepreneur is not only an economic agent but also a symbolic figure who represents tradition, local identity, and interpersonal trust.

Leadership studies have increasingly emphasized the role of ethical leadership, prosocial values, and symbolic communication. The literature on ethical leadership (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Resick et al., 2006), organizational trust (Godfrey & Mahoney, 2014), and storytelling in business (Boje, 2014; Clark & Rossiter, 2008) has advanced our understanding of how legitimacy is built in organizations. However, empirical research remains scarce in culturally embedded MSMEs operating in rural or semi-informal settings, where legitimacy is negotiated not through bureaucratic systems but through relational, ethical, and symbolic means (Guinot et al., 2020; Liao, 2022).

Diverging perspectives exist in the field. Some scholars emphasize formal, legal-rational structures and top-down systems of compliance to ensure leadership legitimacy (Weber, 1947; Williamson, 1995). Others contend that in culturally dense or institutionally fragile environments, leadership is legitimized from the bottom up through moral congruence, shared narratives, and community validation (Barnard, 1938/2002; Boje, 2014; Ramachandran et al., 2023). This study builds on the latter approach.

Drawing on Chester Barnard’s theory of accepted authority and constructivist theories of organizational storytelling, this research explores how small tequila entrepreneurs in the Agave Route articulate and sustain their leadership legitimacy. Using a qualitative, interpretive methodology based on semi-structured interviews, this study examines how ethical practices, conscious cooperation, and narrative expression function as tools of symbolic leadership and trust-building.

The study proposes an interpretive model in which legitimacy emerges at the intersection of practiced ethics, narrative construction, and collective recognition. In doing so, it contributes to the understanding of moral and symbolic leadership in territorially grounded micro and small enterprises (MSMEs). It offers insights into how trust-based leadership can support sustainable development in culturally significant regions.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative, interpretive approach based on semi-structured interviews to explore how microenterprise leaders in Jalisco’s Agave Route, specifically in the tequila industry, construct and sustain legitimate leadership. The research design was grounded in constructivist epistemology, which is particularly suitable for understanding meaning-making processes in culturally embedded contexts.

2.1. Sampling and Participants

The sampling strategy was purposive and theoretical. Ten tequila entrepreneurs were selected from municipalities officially recognized as part of the Agave Landscape and Ancient Industrial Facilities of Tequila (UNESCO, 2006). Selection criteria included formal registration of the enterprise, operation within the local supply chain (production, packaging, or tourism), and demonstrated leadership role in the organization. Efforts were made to ensure variation in business size and years of operation.

2.2. Data Collection

Data were collected through in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted between January and March 2024. Each interview lasted between 45 and 70 minutes and was conducted in Spanish, the participant’s native language. All interviews were audio-recorded with informed consent and later transcribed verbatim. A flexible interview guide was developed to explore ethical leadership practices, narrative forms of communication, and sources of perceived legitimacy.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using thematic coding and constant comparison methods guided by grounded theory techniques (Charmaz, 2014). Initial open codes were generated from the transcripts and grouped into axial categories, allowing for the emergence of conceptual patterns. Coding was performed using MAXQDA 2022 software.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Research Coordination Office of the Centro Universitario de los Valles (University of Guadalajara) under the official letter CI-FI/17/2024. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study, their right to withdraw at any time and the anonymity of their responses. Pseudonyms were used to protect identities.

2.5. Availability of Materials and Data

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to confidentiality agreements with participants, raw interview transcripts will not be publicly deposited.

2.6. Use of Generative AI

Generative AI tools were used exclusively to improve the English-language clarity and structure of the manuscript draft. No AI was employed for data generation, analysis, or interpretation.

3. Results

This section presents the core findings from ten semi-structured interviews with tequila entrepreneurs from the Agave Route in Jalisco, Mexico. The results are organized into three analytical categories: (1) ethical consistency as the root of legitimacy, (2) trust-based leadership through cooperative action, and (3) storytelling as a symbolic anchor of organizational identity. Representative quotes are included to highlight the voices of participants.

3.1. Ethical Consistency as the Root of Leadership Legitimacy

All participants emphasized that legitimacy is not granted by formal titles or institutional credentials but is earned through consistent ethical behavior. Respondents described leadership legitimacy as a function of “living your values” daily.

Several entrepreneurs mentioned that their employees and clients expected “coherence between speech and action.”

Ethical attributes such as honesty, reliability, and responsibility were often cited as pillars of credibility.

In rural settings, reputation functions as an informal mechanism of accountability, reinforcing the expectation that business leaders act as moral agents.

“Here, titles do not matter as much as keeping your word. That is what builds trust.” (Participant 4)

“I prefer to lose a sale rather than deceive a client. That is leadership to me.” (Participant 9)

Some also linked their ethical position to intergenerational responsibility, viewing the business as a legacy that must be preserved with integrity.

3.2. Trust-Based Leadership and Cooperative Engagement

Leadership was consistently described as relational and collective. Entrepreneurs emphasized that legitimacy stems from being present, accessible, and engaged, rather than issuing orders.

Participants reported that working alongside employees was critical for earning respect and trust.

Cooperative relationships extended beyond the firm, including local producers, community organizations, and tourism alliances.

Trust was seen as reciprocal: leaders trusted their people and expected that trust would be returned through commitment and shared effort.

“People follow you when they feel you are walking with them, not above them.” (Participant 1)

“If there is no trust, there is no business. We lead with example, not with authority.” (Participant 7)

Participants also reflected on crisis scenarios (e.g., agave shortages and tourism declines during the COVID-19 pandemic), where trust built over time enabled them to sustain operations through informal agreements, shared sacrifices, and transparent communication.

3.3. Storytelling as a Tool for Symbolic and Commercial Legitimacy

Entrepreneurs described storytelling as an organic practice embedded in their daily interactions with clients, partners, and community members. These narratives served to communicate values, heritage, and the distinctiveness of their tequila.

Stories often included family origins, ancestral techniques, or the founder’s struggles and triumphs.

Some entrepreneurs reported incorporating storytelling into tourist visits, guided tastings, and social media marketing.

Others acknowledged its potential but admitted they had not yet formalized or digitalized these narratives.

“Telling our story makes the client feel part of it. We are not just selling tequila—we are sharing who we are.” (Participant 2)

One notable pattern was the use of emotionally charged or moralized anecdotes, which served to position the business as both authentic and trustworthy. Several participants framed storytelling as a way of “educating” the visitor about cultural identity and ethical production.

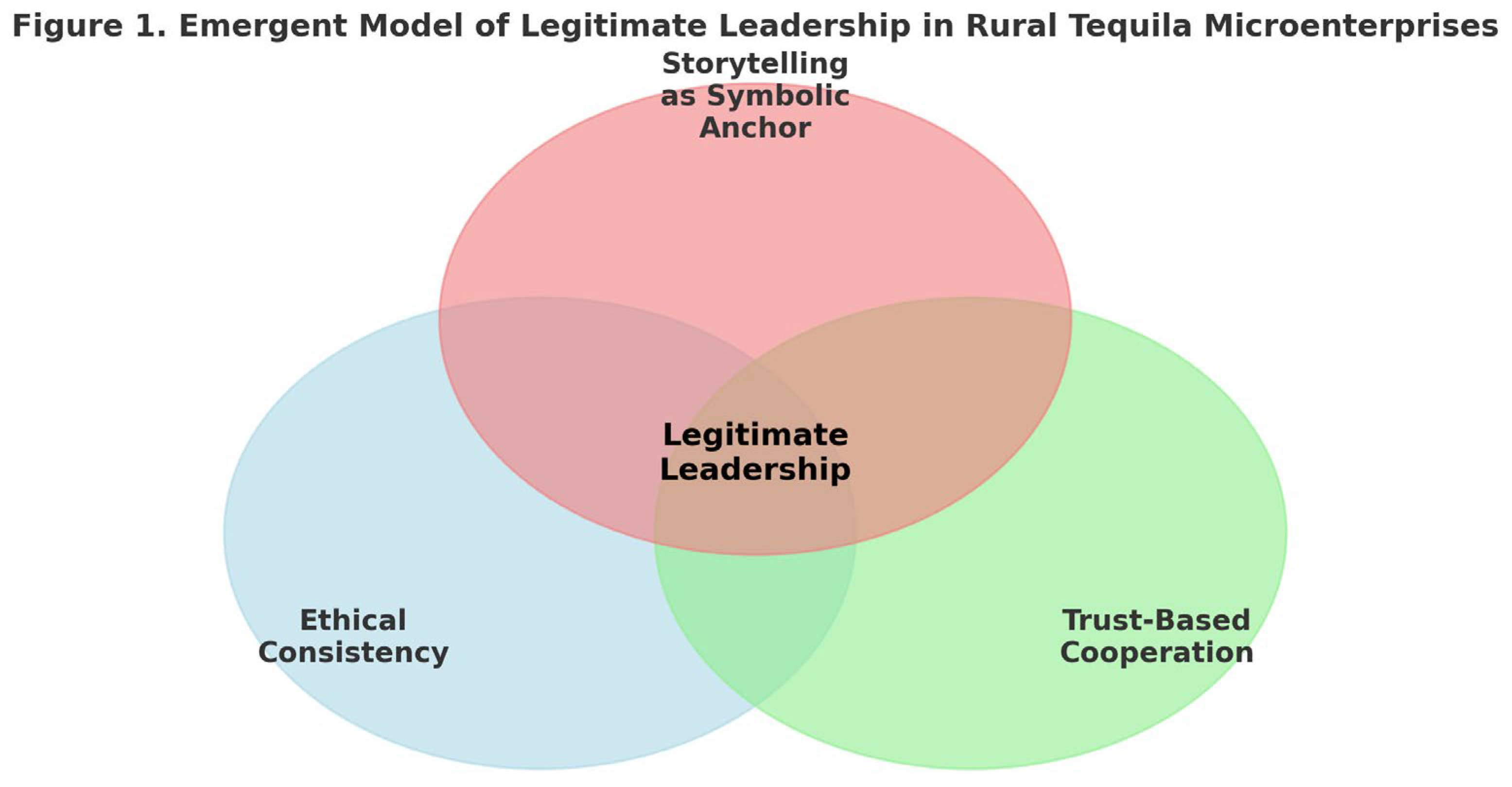

3.4. Visual Synthesis

Figure 1. Emergent Model of Legitimate Leadership in Rural Tequila Microenterprises.

This figure synthesizes the findings into a three-dimensional model where ethical consistency, trust-based cooperation, and symbolic storytelling intersect to generate leadership legitimacy.

4. Discussion

This study examined the construction of legitimate leadership among tequila entrepreneurs operating in rural microenterprises along Mexico’s Agave Route. The emergent model—centered on ethical consistency, trust-based cooperation, and symbolic storytelling—offers a novel lens through which to understand how legitimacy is negotiated in culturally embedded contexts with limited formal institutional oversight.

4.1. Interpreting the Findings in Light of Theory

The results reaffirm the relevance of Chester Barnard’s (1938/2002) foundational concept of authority, which is rooted in acceptance rather than position. In these microenterprises, leadership legitimacy is built not through hierarchical imposition but through demonstrated ethical conduct, sustained relational trust, and culturally resonant communication.

This supports and extends recent leadership theories that emphasize moral credibility and follower alignment (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Treviño et al., 2014). Unlike approaches grounded in transactional logic or organizational formalism (Weber, 1947; Williamson, 1995), the leaders in this study operate through relational-symbolic authority, validated daily through their interactions and alignment with community values.

Interestingly, legitimacy is constructed performatively: entrepreneurs are continuously evaluated by employees, clients, suppliers, and neighbors based on their perceived congruence between discourse, values, and action. This dynamic is consistent with constructivist theories of leadership (Uhl-Bien, 2006) that view leadership as a socially constructed and reciprocally enacted phenomenon.

4.2. Storytelling as a Mechanism of Legitimacy

One of the most distinctive findings is the role of storytelling not only as a communication strategy but also as a symbolic mechanism for legitimacy formation. This confirms Boje’s (2014) argument that narratives are central to organizational sensemaking but extends it by demonstrating how, in rural entrepreneurial contexts, storytelling is interwoven with moral authority and cultural identity.

These stories—family legacies, struggles to start the business, or moments of moral decision-making—serve multiple functions:

They communicate authenticity to visitors and clients.

They educate about local traditions and ethics.

They reinforce internal cohesion by grounding the business in a shared narrative.

In line with organizational storytelling theory (Gabriel, 2000; Denning, 2011), these narratives become “moral performances” that authenticate the entrepreneur’s position and affirm the business’s purpose beyond profit.

However, many participants reported that they had not formalized this practice, instead relying on spontaneous or oral forms of communication. This presents an opportunity for training and digitalization to enhance both internal identity and external market positioning.

4.3. Trust and Cooperation in Contexts of Informality

The cooperative dimension of leadership reflects principles from stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984) and recent studies on compassionate and inclusive leadership (Ramachandran et al., 2023; Liao, 2022). Trust in these firms is not a byproduct of policies or control systems—it is a prerequisite for survival in uncertain, low-infrastructure environments.

This relational dynamic is especially significant in the tequila industry, where community-based supply chains, seasonal work, and reliance on family labor are the norm. The entrepreneurs interviewed emphasized “walking alongside” workers and partners, which resonates with the servant leadership perspective (Eva et al., 2019) and with culturally rooted forms of Latin American leadership that emphasize care, mutual respect, and consistent presence (Dávila & Elvira, 2012).

Thus, leadership legitimacy is sustained through ethical engagement and emotional proximity rather than through technical expertise or strategic abstraction.

4.4. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to leadership theory in four specific ways:

It contextualizes ethical leadership within rural, culturally embedded microenterprises —a field underrepresented in the literature.

It introduces storytelling as a core mechanism for legitimacy construction, not merely as a means of communication.

It validates a relational trust model of leadership for informal economic settings.

It offers a visual, conceptual model that integrates symbolic, ethical, and cooperative dimensions.

4.5. Practical Implications

The findings are highly relevant for rural economic development, entrepreneurship training, and leadership formation programs. Rather than importing managerial models designed for large firms or urban settings, training in these regions should:

Encourage leaders to explore and articulate their ethical narratives.

Formalize storytelling practices as tools for transmitting value and branding identity.

Promote cooperative leadership practices that align with cultural expectations of proximity and humility.

Additionally, public policy aimed at developing rural enterprises should recognize informal legitimacy mechanisms—such as narrative credibility and moral reputation—as equally important as financial metrics or formal registration.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research

Like all qualitative studies, this research is contextually bounded. The focus on a single industry (tequila) within a specific cultural-geographical region (the Agave Route) limits generalizability. However, the proposed model may be adapted and tested in other settings with a strong cultural identity (e.g., mezcal, coffee, indigenous crafts).

Future research could pursue:

Comparative studies across industries and regions.

Mixed methods are designed to quantify the impact of perceived legitimacy on employee engagement or customer loyalty.

Longitudinal studies track how legitimacy narratives evolve with business growth or generational change.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to understand how leadership legitimacy is constructed and sustained within rural microenterprises operating in Mexico’s tequila sector, specifically along the Agave Route. In contrast to dominant models that conceptualize leadership as the exercise of formal authority or the implementation of strategic competence, this research reveals a more situated and morally grounded reality: legitimacy emerges through the ethical, relational, and symbolic practices of local entrepreneurs.

Three central dimensions were identified: (1) ethical consistency, understood as the alignment between discourse and action; (2) trust-based cooperation, expressed through participatory engagement and mutual responsibility; and (3) storytelling, functioning as a vehicle of cultural continuity and symbolic anchoring. These elements coalesce into a contextual model of legitimate leadership, distinct from traditional bureaucratic or transactional paradigms.

Theoretically, this work contributes to the ongoing redefinition of leadership in management literature. It challenges the applicability of standardized frameworks in culturally rich and informally structured settings. By integrating perspectives from ethical leadership, organizational storytelling, and stakeholder trust, it offers an interpretive model rooted in lived practices and territorial belonging. This is especially relevant for rural development contexts where leadership is enacted not only through decision-making but also through moral authorship and cultural stewardship.

Practically, the findings underscore the need to design leadership development strategies that are culturally responsive and ethically oriented. For institutions promoting entrepreneurship in rural regions, it is not enough to teach business models or financial literacy; it is essential to recognize and cultivate the symbolic, emotional, and ethical dimensions that sustain social legitimacy. Storytelling emerges as a high-potential, low-cost tool for reinforcing organizational identity, communicating purpose, and engaging stakeholders.

Moreover, the study has implications for policymakers, educators, and NGOs working in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). Supporting rural entrepreneurship requires not only infrastructure and capital but also a deep understanding of local values and the mechanisms through which legitimacy and trust are built.

In conclusion, this research affirms that leadership in rural microenterprises is not simply a managerial function—it is a moral and symbolic practice shaped by culture, proximity, and community. The entrepreneurs studied here are led not only by directing operations but also by embodying integrity, sustaining relationships, and narrating a collective story of identity and purpose. Future research would benefit from expanding this approach across industries and territories to explore further how localized leadership models contribute to broader processes of sustainable territorial development.

6. Patents

There are no patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Francisco Javier Maldonado Virgen; validation, Francisco Javier Maldonado Virgen; investigation, Francisco Javier Maldonado Virgen; writing—original draft preparation, Adriana Rodríguez López; formal analysis, Ma. del Refugio López Palomar; methodology, Ma. Del Refugio López Palomar; software, Sara Adriana García Cueva; resources, Sara Adriana García Cueva; data curation, Sara Adriana García Cueva; writing—review and editing, Adriana Rodríguez López; visualization, Sara Adriana García Cueva; supervision, Sara Adriana García Cueva; project administration, Francisco Javier Maldonado Virgen; funding acquisition, Francisco Javier Maldonado Virgen. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Centro Universitario de los Valles (University of Guadalajara) through the 2024 internal research funding call, as outlined in the official letter CI-FI/17/2024. The same institution funded the APC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitario de los Valles (University of Guadalajara) under protocol code CI-FI/17/2024, approved in January 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participants were informed of the purpose of the research, their voluntary participation, and the confidentiality of their responses. No personally identifiable information is included in the publication.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Interview transcripts contain sensitive information and are protected by confidentiality agreements with participants. Data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the administrative and academic staff of the Centro Universitario de los Valles (University of Guadalajara) for their support during the coordination and development of this research project. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4, 2024) to refine language, enhance academic clarity, and generate visual figures. The authors have reviewed and edited all output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Meaning |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of Open Access Journals |

| TLA |

Three Letter Acronym |

| LD |

Linear Dichroism |

| MSMEs |

Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| APC |

Article Processing Charge |

Appendix A

The following is the semi-structured interview guide used during the fieldwork. The guide served as a flexible framework to explore ethical practices, leadership perceptions, community ties, and storytelling experiences among tequila microentrepreneurs.

Can you describe your role as a business leader in your community?

What values do you consider important in the daily management of your business?

How do you build trust with your workers, clients, or partners?

Are there stories or experiences that represent your business identity?

In what ways do you think your leadership is perceived as legitimate?

How has your leadership been tested in moments of difficulty?

Appendix B. Thematic Coding Summary

Table A1.

Summary of Thematic Categories and Sample Codes.

Table A1.

Summary of Thematic Categories and Sample Codes.

| Theme |

Code Example |

Participant Quote (translated) |

| Ethical Consistency |

“Keeping your word” |

“Aquí no vale tanto el título que tengas, sino que cumplas lo que dices.” |

| Trust-Based Cooperation |

“Leading by example” |

“Uno lidera con hechos, no con órdenes.” |

| Symbolic Storytelling |

“Sharing identity through story” |

“Contar nuestra historia es una forma de que el cliente se sienta parte de esto.” |

References

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable leadership practices for enhancing business resilience and performance. Strategy & Leadership 2011, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, C.I. The functions of the executive; Harvard University Press, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boje, D.M. Storytelling organizational practices: Managing in the quantum age; Routledge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Language and symbolic power; Harvard University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners; SAGE Publications, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheffi, W.; Jarjoui, Y.; Moustafa, M. Ethical leadership and circular economy: The mediating role of internal control systems in SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13577. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M.C.; Rossiter, M. Narrative learning in adulthood. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 2008, 119, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, S. The leader’s guide to storytelling: Mastering the art and discipline of business narrative, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass, 2011. [Google Scholar]

-

The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, F.; Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Cuervo-Arango, A. Strategic innovation in rural family SMEs: A multiple case study. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 2023, 30, 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes Business Council. How storytelling strengthens leadership credibility. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2024/03/15/how-storytelling-strengthens-leadership-credibility/ (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Gabor, A.; Mahoney, J.T. Chester Barnard and the Systems Approach to Nurturing Organizations. History of Economic Ideas 2010, 18, 89–118. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, P.C.; Mahoney, J.T. The Functions of the Executive at 75: An invitation to reconsider a timeless classic. Journal of Management Inquiry 2014, 23, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinot, J.; Chiva, R.; Mallén, F. Understanding the link between compassionate love and organizational performance: The role of organizational learning capability. Personnel Review 2020, 49, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyamukenge, J.; Kagwaini, D. Ethical leadership and community engagement in African SMEs: Evidence from South Africa. Journal of Small Business Strategy 2024, 34, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Khdour, N.; Fenech, R.; Baguant, P.; Wahid, F. The power of organizational storytelling: The story of a company in times of transformation. Corporate Governance and Organizational Behavior Review 2023, 7, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, J.; Dodd, S.D.; Wilson, F. Narrative change and community innovation: Storytelling as a tool for collective transformation. Local Economy 2024, 39, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Malanga, D.; Banda, W. Challenges facing rural small and medium enterprises: A qualitative perspective. International Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Research 2021, 9, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mamabolo, M.A.; Myres, K.; Visser, K. Values-driven leadership and legitimacy in social enterprises: Evidence from South African entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Ethics 2023, 188, 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ozuem, W.; Thomas, T.; Howell, K.E.; Willis, M.; Lancaster, G. Exploring SME decision-making through qualitative thematic analysis: The case of digitally driven resilience. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 2024, 27, 102–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, S.; Balasubramanian, S.; James, W.F.; Al Masaeid, T. Whither compassionate leadership? A systematic review. Management Review Quarterly 2023, 74, 1473–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resick, C.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Dickson, M.W.; Mitchelson, J.K. A cross-cultural examination of the endorsement of ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics 2006, 63, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, M.W.; Bullough, A.; Webb, J.W. Entrepreneurial resilience and community connection in small rural firms. Journal of Small Business Management 2023, 61, 200–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sauers, K. Ethical leadership in community organizations: A qualitative study using narrative interviews. Leadership and Policy in Schools 2022, 21, 456–475. [Google Scholar]

- Şengüllendi, A.; Yıldız, B.; Durmaz, V. The role of ethical leadership in ESG-oriented SME strategy. European Journal of Management and Business Economics 2024.

- Stake, R.E. Qualitative case studies. In In Strategies of qualitative inquiry; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE Publications, 2007; pp. 119–149. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).