Introduction

Prior to 1950, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia lacked specialized psychiatric services due to various reasons, including the prevalent social stigma surrounding mental illness. Cultural beliefs often attributed mental illness to spiritual possession. Individuals with mental health conditions were typically confined in asylums, where physical restraint was used to protect society from those perceived as “violent.” The staff working in these asylums primarily consisted of caretakers who were not mental health professionals. Dr. Osama Al-Radhi, the first Saudi psychiatrist, played a pivotal role in developing psychiatric care in the Kingdom. In 1952, the first psychiatric hospital in Saudi Arabia, Shehar Hospital, was established in Taif1. Present-day Saudi Arabia’s population consists of 33 million people, with children and young adults under the age of 15 accounting for nearly 24% of the total population2. The country’s ratio of mental health professionals stands at 19.4 per 100,000, which although above the global average, is still significantly lower than the median found in high-income countries3. Furthermore, only 7% of mental health workers in Saudi Arabia are psychiatrists, a figure that is considerably lower than the 20% average both globally and in high-income countries. Finally, Saudi Arabia allocates 78% of its mental health expenditure toward hospital-based treatments, a figure more closely aligned with lower-income nations than the 44% average in high-income nations3,4.

As a result of this historical inertia, psychiatric services may be expected to be in shortage at the very least, or to be underutilized even if available. This perspective may be reinforced by results from the most recent mental health survey in Saudi Arabia, conducted by the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia in 20195. The results indicated that approximately 34.2% of the population had experienced some form of a mental health condition. The most common disorders identified were anxiety disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and mood disorders. Regarding children’s mental health, the survey reported that approximately 13% of children and adolescents faced mental health challenges. Developmental disorders, including intellectual disabilities and learning disorders, were found to have a prevalence rate of 1–2%. In a recent systematic review, the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children in Saudi Arabia was estimated to be 1.3%6. Past research on psychiatric morbidity in Saudi Arabia has primarily been concentrated on specific subpopulations, often with limited sample sizes, thus the prevalence may be underrepresented by these surveys.

Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030

However, KSA is a nation with significant resources to invest in infrastructure. One relative strength of the system is in the number of primary care providers. Saudi Arabia currently has 2,390 primary healthcare centers, equating to approximately 3.7 per 10,000 people7. Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030 is a comprehensive national development plan that has placed significant emphasis on reforming and enhancing the healthcare system to improve population health outcomes and quality of life7. One of the key focus areas of Vision 2030 is the strengthening of primary healthcare delivery, with an aim to enhancing the foundation for preventive care, early disease detection, and chronic disease management8,9.

In line with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, the Ministry of Health has initiated the development of a new healthcare system aimed at promoting social, mental, and physical well-being through a patient-centered model of care 10. This new model is designed to cater to the unique needs of individual patients and comprises six patient-centered systems of care: “Keep Me Well,” Chronic Care, Urgent Care, Planned Care, Safe Birth, and Last Phase. Mental health is incorporated within the Chronic Care system. Additionally, the Ministry of Health formulated a national mental health strategy under Vision 2030, emphasizing cross-sector stakeholder collaboration to align it with the model of care and broader health transformation principles. The strategy focuses on patient-centered care, starting at the community and primary care level, with the goal of enhancing the quality, accessibility, and integration of mental health services in the Kingdom11.

Autism Spectrum Disorder in KSA

ASD is very important in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia because of the particularly high prevalence of genetically determined disorders, which may be related to the high prevalence of consanguinity. 12 The estimated prevalence of ASD varies substantially across studies, with the prevalence being unknown in many low and middle-income countries13,14. The needs of children with ASD are often not met due to the limited numbers of services and trained professionals in the field. Because ASD is associated with numerous comorbidities, such as epilepsy, sleep problems, motor impairments, intellectual disability, attention problems, externalizing behaviors, and impaired sensory perception14,15, there is a high burden on clinicians and caregivers of patients with ASD, which in turn may complicate patient management, and necessitate an increase utilization of healthcare facilities. One recent report shows that children with ASD have six times as many annual outpatient visits compared to the wider population and twice as many as children with other developmental disorders16.

Additional Comorbidity in ASD

Individuals with ASD who also have ADHD experience greater impairment in executive control function and daily living skills compared to individuals with ASD who do not have comorbid ADHD17. Moreover, children with ADHD who have more comorbidities also require more healthcare visits18. Similar patterns have been established between ASD and epilepsy, another condition that further worsens functionality and social adaptability. Seizure episodes occur at much earlier ages in individuals with epilepsy and ASD than in individuals with epilepsy alone19. The mortality rate is also increased in individuals with ASD, along with the comorbidity of epilepsy20. Thus, comorbid conditions can have serious effects on children with ASD, which reinforces the need for the accurate characterization of the prevalence of comorbid conditions across the ASD population. Studies have also consistently reported the influence of age and sex on the prevalence of comorbid conditions in individuals both with and without ASD. For example, the prevalence of ADHD is higher in males (13.2%) than in females (5.6%)21, schizophrenia is diagnosed 1.4 times more frequently in males than in females, typically with an earlier onset in males22.

Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare (JHAH)

JHAH is an integrated healthcare network in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, which includes a 457-bed tertiary care hospital in Dhahran, a 55-bed hospital in Al Hasa, and three satellite outpatient and third-party medical designated facilities. JHAH is responsible for the provision of healthcare to approximately 360,000 eligible persons, including Saudi Aramco employees in the Eastern Province, their dependents, and retirees. JHAH is accredited by both the Joint Commission International and the Saudi Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutes. JHAH strategic primary healthcare plan is in line with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 with emphasis on early disease detection, and chronic disease management, thus serves as an excellent locale to conduct this analysis. Mental health comorbidities are not historically well identified in KSA, yet with the current infrastructure and primary care model at JHAH, comorbidities may be recognized much more efficiently.

In the current study, we aimed to verify this impression and assess the prevalence of ASD comorbidities across sex and age groups among children ≤17 years of age. We also aimed to assess the utilization of healthcare facilities hypothesizing that if the service delivery system was working as expected, utilization would increase as the number of comorbid conditions were more efficiently identified.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This electronic record study was retrospectively conducted at JHAH, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. All patient data were retrieved from the electronic health record management system Epic to analyze comorbidities among patients diagnosed with ASD. In total, 220 records were reviewed for comorbidities, both psychiatric and medical, and healthcare utilization by children with ASD in relation to comorbidities. Prior to data collection, the study was approved by the institutional ethics committee at John Hopkins Aramco Healthcare center, Dhahran, on January 30, 2024. #H-05-DH-044. IRB# 24-25.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was determined for a population of 24,371 children, with an estimated prevalence of ASD at 1.33%6. Applying a margin of error of ±5% and a 95% confidence level, the minimum calculated sample size was 21 participants. Reports were collected using Microsoft Excel, and then coded and revised. Finally, the data were transferred into SPSS (version 23, IBM). Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables, and the mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for continuous variables. Chi-squared analyses were used as appropriate to evaluate the relationships between participants’ characteristics and disorders. All statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed tests with an alpha error of 0.05. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

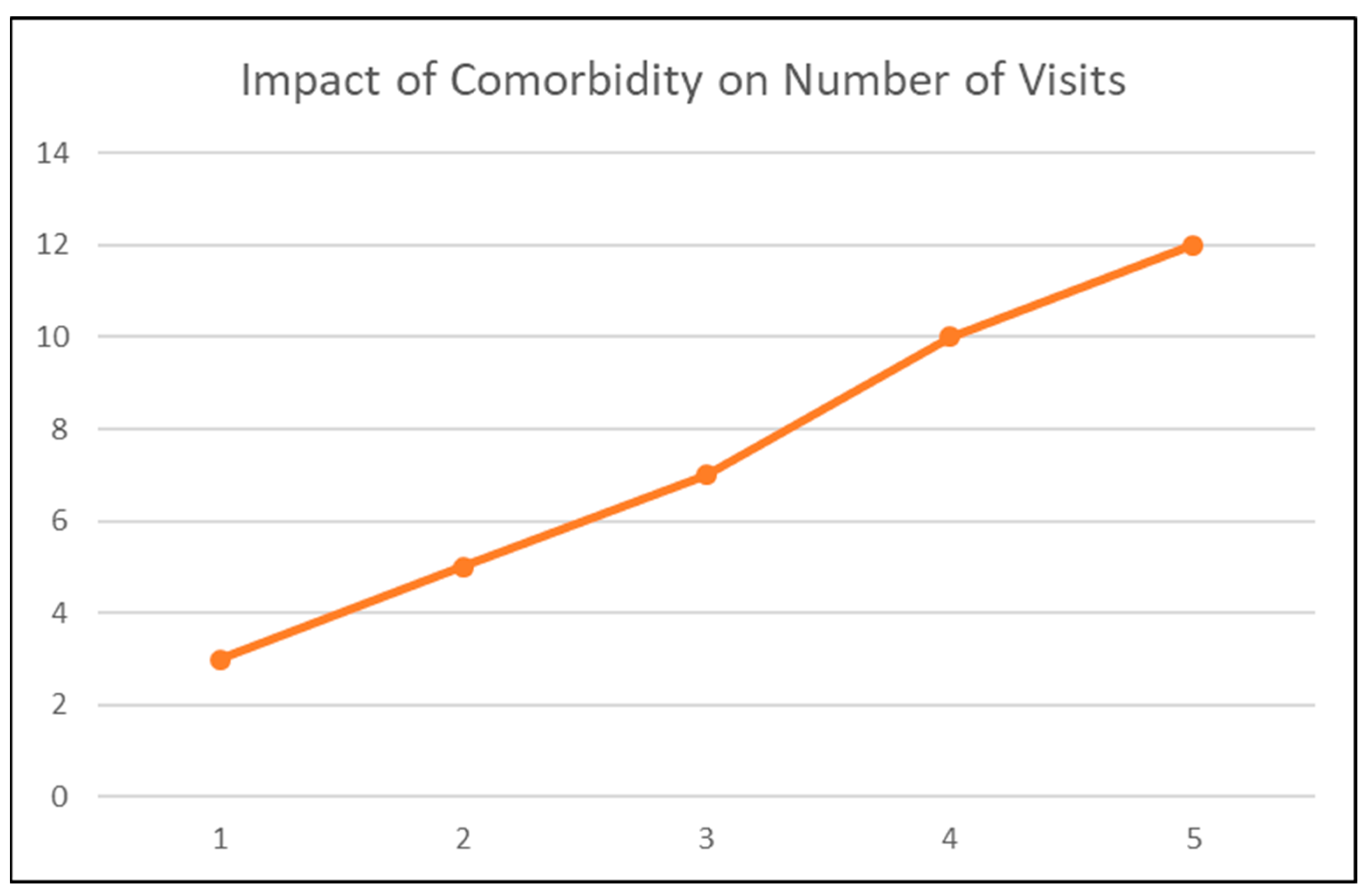

During a representative one-year period, from approximately 2019 to 2020, data from the electronic medical records showed that 220 children had a diagnosis of ASD, and they were evaluated over 1,231 healthcare visits (Table I). The age distribution did not differ between the sexes. The mean age of males was 7.6 (SD 3.19) years whereas that of females was 7.1 (SD 4.23) years (P=0.71). Similar age distributions were found across national origins and encounter settings. The mean number of clinical encounters per child was 6.4 (SD 12.2) visits, with a positive correlation between the number of comorbidities and utilization of healthcare facilities.

Table II describes the demographic characteristics of the study population. The highest proportion (34%) was in the age range of 11–15 years, followed by those aged 6–10 years (25%) and those ≤5 years of age (24%). Most of the children were male (79%), and 21% were female. Out of the 220 study participants, 135 (61.2%) were Saudi nationals, 2.6% were other Gulf Cooperation Council nationals, and 36.2% were non-GCC nationals.

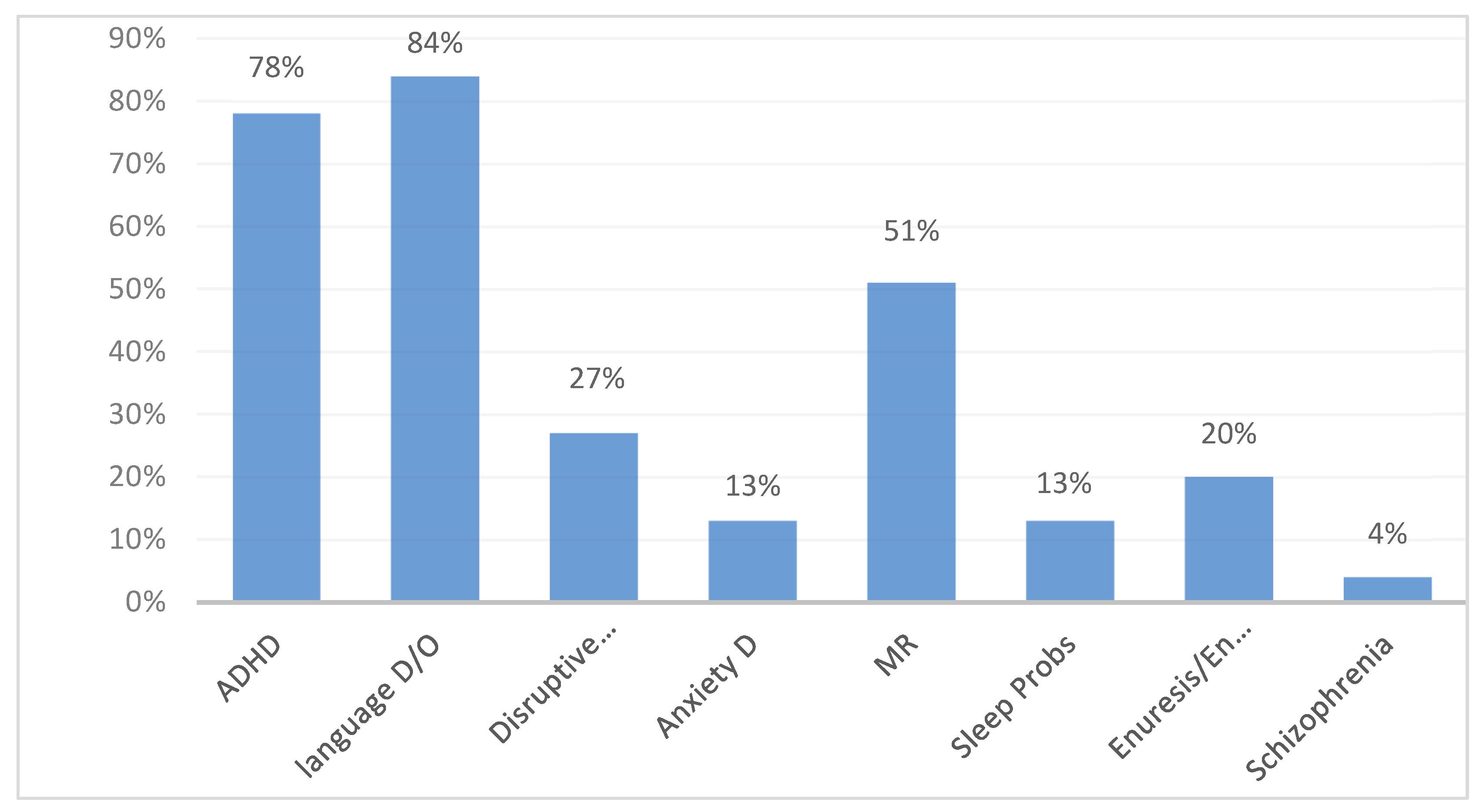

Among this cohort of children with ASD, several behavioral and mental comorbid conditions were recorded; 84% of them had a language/speech disorder, followed by 78% who had an ADHD diagnosis, 51% who had intellectual disabilities, and 27% who showed disruptive behavior (

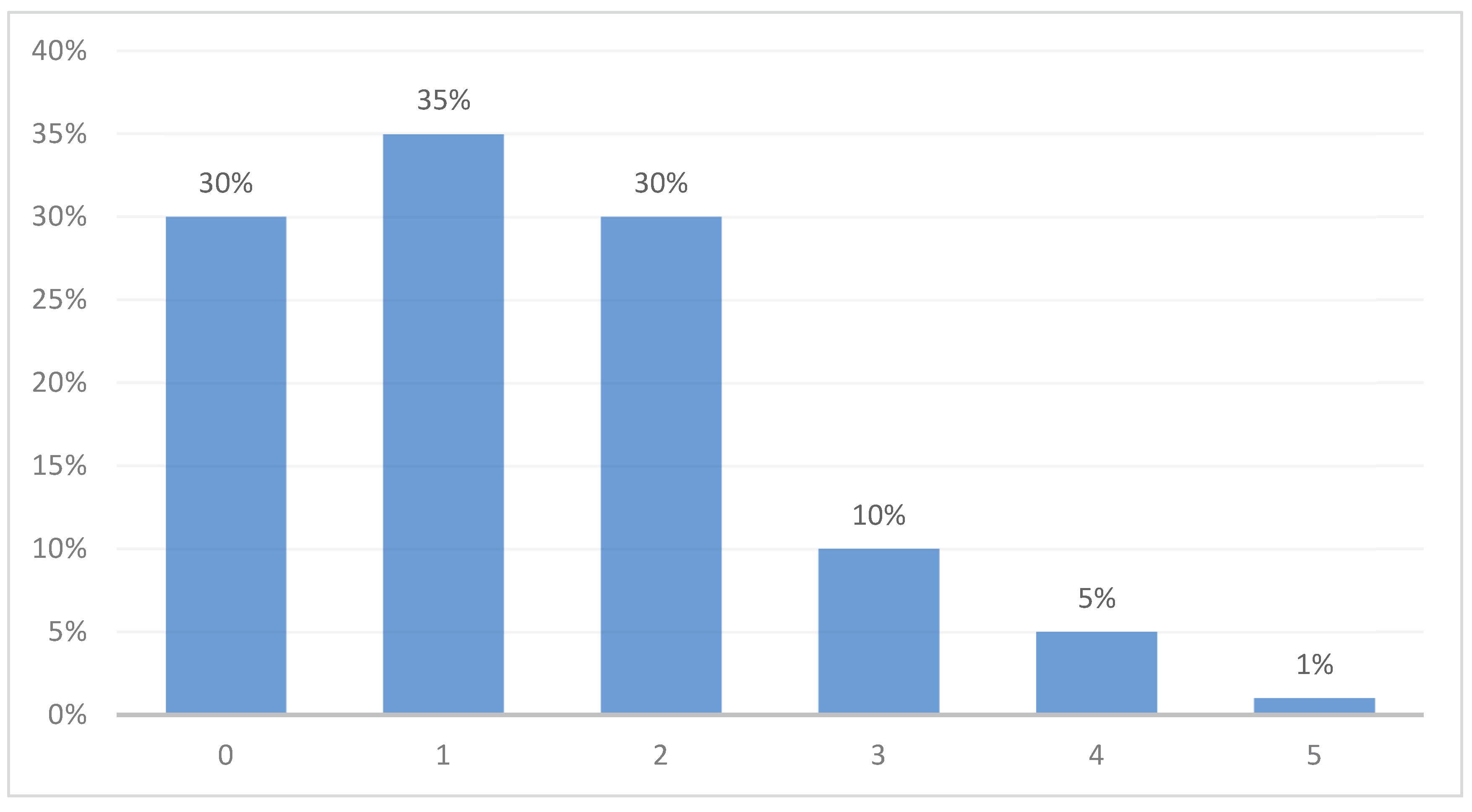

Figure 1). Approximately one third of patients (30%) had no additional behavioral comorbidity, one third had one comorbidity (35%), and almost half (46%) had two or more comorbidities (

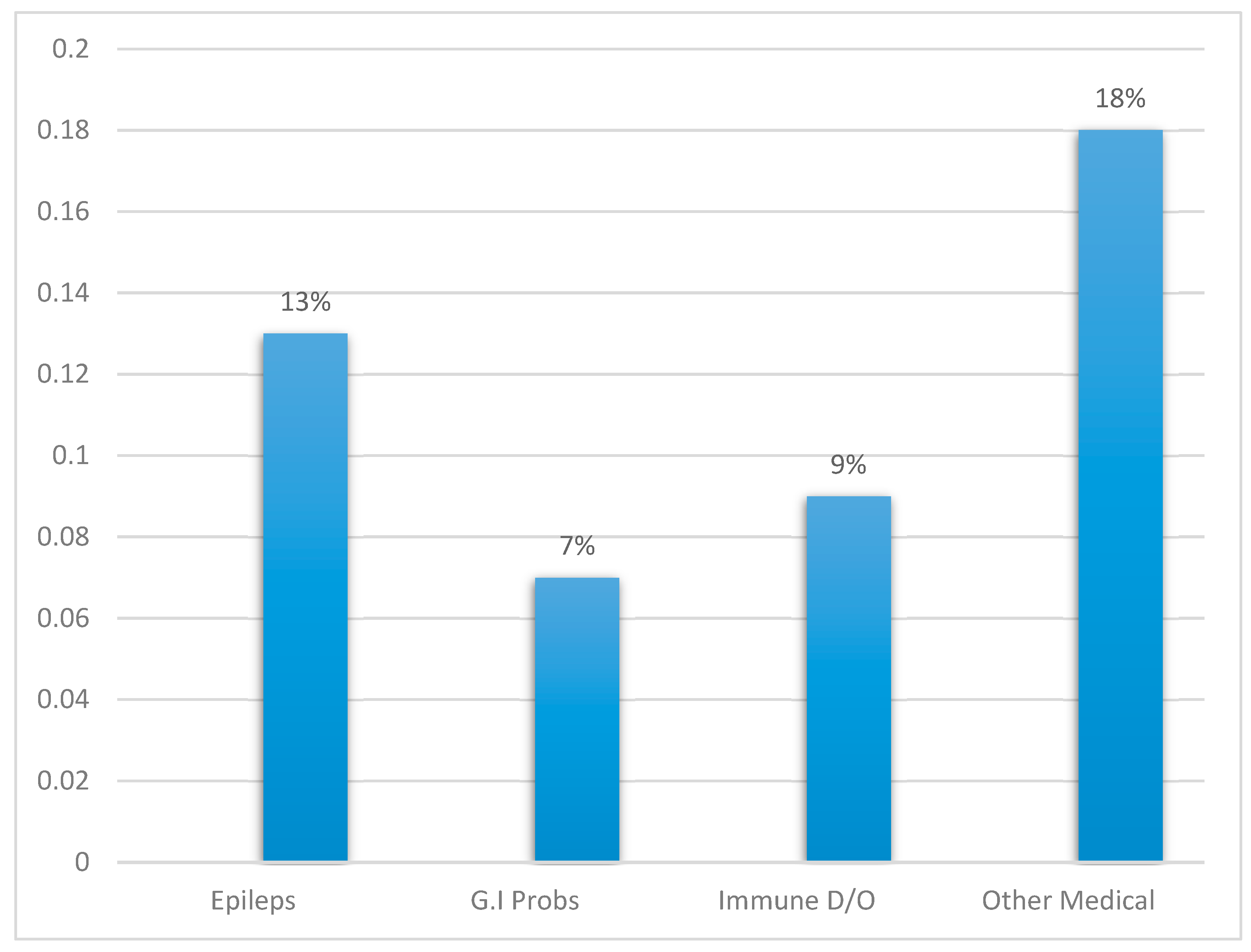

Figure 2). Almost half of the children (47%) had at least one comorbid medical or neurological disorder, with epilepsy being the most prevalent (13%), followed by gastrointestinal problems (7%), immune diseases (9%), and other medical ailments (approximately 18%) (

Figure 3).

Patterns of Healthcare Utilization

The mean number of clinical encounters per child was 6, with a clear correlation between the number of comorbidities and the number of clinical visits. Patients with more comorbidities tended to have more visits. Children with ASD with one comorbidity had an average of three clinical visits per year, whereas children with ASD and four or five comorbidities had an average of 10–12 clinical visits per year (

Figure 4).

Discussion

Our study analyzed the comorbidities occurring in a cohort of children with ASD aged ≤17 years and evaluated the prevalence of 10 common comorbid conditions across sex and age groups. Overall, we found that epilepsy, ADHD, sleep disorders, intellectual disabilities, and language/speech disorders were comorbid in children with ASD, reinforcing that a considerable proportion of individuals with ASD are affected by medical or psychiatric comorbidities. ASD, which has a strong genetic component, is common in the Saudi Arabian population, which potentially can be attributed to high consanguinity rates. In the current study, ASD affects males more frequently than females with a ratio of over than 3:1 (174:46). This finding is closer to a recent meta-analysis that reported a male to female ratio of 4:125. In our study, most patients diagnosed with ASD were between 11 and 15 years of age.

Language/speech disorders were the most frequently occurring comorbid conditions, followed by ADHD and intellectual disabilities. These results are consistent with the observed prevalence of comorbid language/speech disorders and other conditions in children with ASD in other countries. The second most common psychiatric condition in individuals with ASD was ADHD, with 78% of individuals with ASD also being diagnosed with ADHD. This rate is much higher than that found in other contemporary studies. A recent meta-analysis of 33 research studies showed that the prevalence of ADHD in children with ASD was 33–37%21,23.

In our study, approximately 27% of the participants also showed disruptive behavior, 13% had an anxiety disorder, 51% had an intellectual disability, 13% had sleep problems, 20% had enuresis, and 4% had schizophrenia. However, the literature is sparse in terms of studies examining the prevalence of common comorbid conditions such as sleep disorders, enuresis, and schizophrenia in ASD populations22.

In the present study, the most widely reported comorbid medical condition associated with ASD was epilepsy, found in 13% of children with ASD. This rate is consistent with previously reported prevalence rates of epilepsy in the ASD population, ranging from 5% to 46%. This heterogeneity of results can be attributed to the large variation in study populations regarding age and sex26-28. The study limitations include that the data relied on the physician’s diagnosis, as the electronic records review was the primary source to identify patients with ASD and comorbidities. This may have led to under- or over-diagnoses as we could not independently confirm the accuracy of the diagnosis. A strength of the study is that we had access to the complete dataset from Epic, the electronic health record management system employed by JHAH. The study results have implications for predicting the resources needed to manage ASD and comorbidities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Further research is needed to investigate the various treatment strategies and outcomes to determine the best course of action. Moreover, studies should be conducted to investigate the influence of cognitive factors, most importantly the intelligence quotient, on the prevalence rates of comorbid conditions in ASD populations.

Conclusion

Our study confirms that ASD is associated with mental and behavioral comorbidities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia similar to other international settings. Our data illustrate that the most common ASD comorbid conditions include language/speech disorders and ADHD, followed by intellectual disabilities and other psychiatric disorders. We also found a positive correlation between the number of comorbidities and utilization of healthcare facilities as indicated by the increase in the number of annual clinic visits. The patterns of comorbidities crucially differed between males and females, thereby indicating the need for further longitudinal studies to investigate comorbidity patterns across sexes as well as the need to have a better holistic understanding of the genetic, epigenetic, and neurobiological basis of sex- and age-dependent changes in comorbidity. The study observations can be used to guide investment in clinical resources for the assessment and management of ASD and other complex mental health conditions in patients with ASD and other populations. Studies in this or similar systems can further elucidate the effectiveness of different types of infrastructure that may comprehensively guide the treatment of complex pediatric mental health conditions. This type of study may inform comprehensive efforts to improve healthcare infrastructure such as that ongoing with Saudi Arabia’s Vision2030.

Author Contributions

Ahmad Almai: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, supervision, Writing - original draft, Project Administration. Jay Salpekar: Conceptualization, writing - original draft. Anwar AlOtaibi: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software. Jumana Altayeb: Project Administration, Validation, Writing – Review and editing. Hayat Muschcab: Writing – Review and editing. Abdulhameed Alhabib: Data research, collection and review. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the Department of Epic Medical Records at Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare (JHAH), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for their assistance and support.

Article Summary: This paper describes important policy efforts in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia that have improved services for children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Summary of Policy Implications: A primary care centered model for pediatrics has proven to be effective in increasing service utilization for children with complications associated with autism spectrum disorder. Comorbid conditions are readily identified and have led to increased numbers of medical appointments, strongly implying the success of this model. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 is the next step to capitalize on the success of this primary care model, and to further develop a comprehensive approach to health care in pediatrics.

Abbreviations

ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD = autism spectrum disorder; JHAH = Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare; SD = standard deviation; WHO = World Health Organization

References

- Koenig, H. , Al Zaben, F., Sehlo, M., Khalifa, D., Al Ahwal, M., Qureshi, N. and Al-Habeeb, A. Mental Health Care in Saudi Arabia: Past, Present and Future. Open Journal of Psychiatry 2014, 4, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health—KSA [homepage on the Internet]. Annual Statistical Book—2018. [cited 2024 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/book-Statistics.pdf.

- World Health Organization [homepage on the Internet]. Mental health atlas 2017 member state profile: Saudi Arabia. [updated 2018; cited 2024 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/mental-health-atlas-2017-country-profile-saudi-arabia.

- Qureshi NA, Al-Habeeb AA, Koenig HG. Mental health system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013, 9, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altwaijri YA, Al-Subaie AS, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the Saudi National Mental Health Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2020, 29, e1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsulami AN, Alsolami FN, Alsulami JNJ, Alharbi IM, Alotaibi NF, Alotaibi FM. Prevalence and determinants of autism spectrum disorder in children in Saudi Arabia in comparison to developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. IJMDC 2024, 8, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x Vision 2030. (2016). Saudi Vision 2030. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. (2017). National eHealth Strategy. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/nehs/Pages/default.

- Almalki, M. , Fitzgerald, G., & Clark, M. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: An overview. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 2011, 17, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health—KSA [homepage on the Internet]. Annual Statistical Book—2017. [updated 2018; cited 2024 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/ANNUAL-STATISTICAL-BOOK-1438H.pdf.

- Council of Economic and Development Affairs [homepage on the Internet]. Saudi Vision 2030. [updated 2019; cited 2024 Oct 12]. Available from: https://vision2030.gov.sa/en.

- El-Hazmi MA, Al-Swailem AR, Warsy AS, AL-Swailem AM, Sulaimani R, AL-Meshari AA. Consanguinity among the Saudi Arabian population. J Med Genet 1995, 32, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsabbagh M, Divan G, Koh YJ, Kim YS, Kauchali S, Marcín C, et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res 2012, 5, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association;

- Matson JL, Nebel-Schwalm MS. Comorbid psychopathology with autism spectrum disorder in children: an overview. Res Dev Disabil 2007, 28, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hand BN, Miller JS, Guthrie W, Friedlaender EY. Healthcare utilization among children with early autism diagnoses, children with other developmental delays and a comparison group. J Comp Eff Res 2021, 10, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerys BE, Wallace GL, Sokoloff JL, Shook DA, James JD, Kenworthy L. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms moderate cognition and behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res 2009, 2, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almai AM, Salpekar JA. Healthcare utilisation in the United Arab Emirates for children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbidities. BJPsych Int 2023, 20, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence SJ, Schneider MT. The role of epilepsy and epileptiform EEGs in autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Res 2009, 65, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickett J, Xiu E, Tuchman R, Dawson G, Lajonchere C. Mortality in individuals with autism, with and without epilepsy. J Child Neurol 2011, 26, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcutt, EG. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picchioni MM, Murray RM. Schizophrenia. BMJ 2007, 335, 91–95.

- Berenguer-Forner C, Miranda-Casas A, Pastor-Cerezuela G, Roselló-Miranda R. [Comorbidity of autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit with hyperactivity. A review study]. Rev Neurol.

- Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Baron-Cohen S. Autism. Lancet 2014, 383, 896–910.

- Supekar K, Iyer T, Menon V. The influence of sex and age on prevalence rates of comorbid conditions in autism. Autism Res 2017, 10, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielsson S, Gillberg IC, Billstedt E, Gillberg C, Olsson I. Epilepsy in young adults with autism: a prospective population-based follow-up study of 120 individuals diagnosed in childhood. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes JR, Melyn M. EEG and seizures in autistic children and adolescents: further findings with therapeutic implications. Clin EEG Neurosci 2005, 36, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki Y, Yokota K, Shinomiya M, Shimizu Y, Niwa S. Brief report: electroencephalographic paroxysmal activities in the frontal area emerged in middle childhood and during adolescence in a follow-up study of autism. J Autism Dev Disord 1997, 27, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).