1. Introduction

In contemporary society, video surveillance has emerged as a crucial tool for maintaining public safety, deterring criminal activity, and ensuring accountability in both private and public spaces [

1,

2,

3]. Its deployment extends across urban centers, workplaces, transportation hubs, schools, and even personal residences, making it an omnipresent force in daily life [

4,

5,

6,

7]. However, this widespread use of surveillance technology raises a fundamental challenge: the delicate balance between security and individual freedom [

8,

9,

10]. The extensive integration of video surveillance technology significantly influences individual behavior [

11,

12,

13]. As such tools become embedded in various aspects of daily life, individuals experience increased pressure to conform, avoiding actions that might be perceived as deviations from social norms [

14,

15,

16]. In practice, these technologies limit opportunities for anonymous movement and access to services, thereby diminishing individuals’ ability to remain unnoticed [

17,

18]. While surveillance serves the legitimate purpose of maintaining public order, as well as fulfilling other objectives explicitly outlined in Article 6 of the GDPR, its unchecked proliferation risks undermining the very liberties it aims to protect. This could lead to a society where human autonomy is subtly but profoundly eroded [

19]. The establishment of a framework in which every action can potentially be recorded and analyzed places individuals in a context that infringes upon their fundamental need for privacy, even in public spaces [

20,

21].

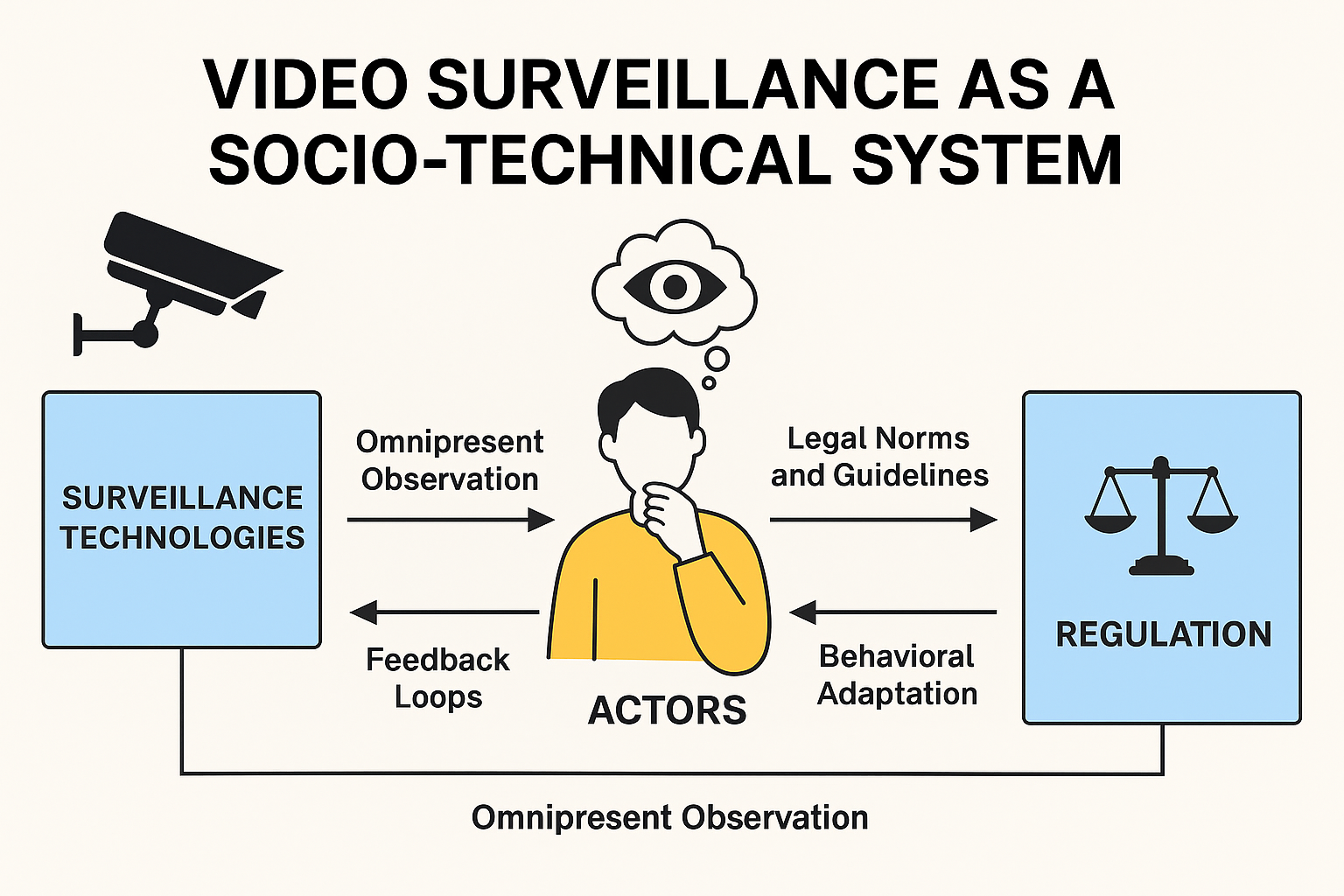

From a systems perspective, video surveillance should not be viewed in isolation as a technological artifact, but rather as a node within a larger cyber-physical-social system. It operates through dynamic feedback loops that connect technological infrastructure, legal norms, organizational practices, and human behavior. The act of observation produces measurable psychological responses in individuals, which in turn alter public behavior patterns, thus shaping the very conditions surveillance is intended to monitor. These recursive interactions reflect the systemic nature of surveillance, wherein social inputs (such as perceived insecurity) lead to technical deployments (e.g., CCTV), which then reconfigure social outputs (e.g., conformity, distrust), requiring new policy responses. This feedback mechanism makes surveillance a powerful regulator of social conduct, albeit one that may generate unintended consequences when not carefully designed and governed.

Michel Foucault’s concept of the Panopticon, derived from Jeremy Bentham’s [

22] architectural model of a prison with constant observation, remains highly relevant in analyzing modern surveillance. In such a system, individuals internalize the awareness of being watched, leading to self-censorship and behavioral conformity. The ability to engage in spontaneous, unfiltered actions, one of the defining characteristics of personal freedom, is curtailed under the silent coercion of surveillance [

23,

24,

25]. This results in what Hannah Arendt [

26] described as the “loss of the public realm,” wherein individuals no longer engage freely in discourse and action but instead operate within the constraints of a monitored society. Moreover, the psychological impact of constant surveillance fosters an environment of suspicion and alienation [

27,

28]. Trust, a fundamental element of social cohesion, is eroded when individuals perceive that their every move is being scrutinized [

29]. This not only affects interpersonal relationships but also undermines democratic participation, as individuals may be deterred from political engagement due to fears of surveillance by state authorities or private entities [

30,

31,

32].

In the language of systems theory, the behavioral effects of surveillance can be understood as emergent properties resulting from the interaction of system components - technological monitoring, regulatory structures, and individual cognition. Surveillance thus functions not merely as a deterrent but as a form of distributed control, one that influences behavior not through direct enforcement but through the perceived risk of observation. The mere presence of surveillance infrastructure modifies the environment in which choices are made, steering individuals toward conformity without requiring active intervention. This embeddedness within daily environments illustrates the characteristics of self-regulating systems, wherein human behavior becomes an adaptive response to evolving systemic constraints.

The issue of video surveillance becomes even more concerning when viewed as just one component of the broader surveillance infrastructure embedded in society, with potential chilling effects on the exercise of fundamental rights. According to Schauer’s [

33] theory of “chilling effects,” government surveillance may deter individuals from engaging in legitimate or desirable online activities due to fears of legal repercussions or criminal sanctions, compounded by a lack of trust in the legal system’s ability to protect their rights and innocence.

Expanding on this concept, Solove [

34,

35] broadened chilling effects theory by examining the implications of modern surveillance and data collection. He argues that these practices function as a form of regulatory “environmental pollution”, subtly shaping behavior by fostering an atmosphere in which individuals preemptively regulate their actions. His approach highlights how government monitoring of online activities cultivates a pervasive sense of conformity and self-censorship, ultimately constraining free expression and individual autonomy. The phenomenon of “social sorting”, in which surveillance data is used to categorize and predict behaviors, exacerbates concerns related to discrimination and social stratification. This reinforces systemic biases and limits opportunities for marginalized groups [

36,

37].

Understanding surveillance as a socio-technical phenomenon benefits significantly from the conceptual lens of General Systems Theory (GST). Originating from the work of Ludwig von Bertalanffy [

38], GST emphasizes the study of systems as organized wholes composed of interrelated and interdependent elements that operate through dynamic interactions. According to Bertalanffy [

39], the traditional scientific approach relied heavily on reductionism, analyzing observable phenomena by decomposing them into elementary, isolated units. This method, while effective in controlled contexts, fails to account for emergent properties and feedback dynamics intrinsic to complex systems. In contrast, GST proposes a holistic framework in which natural, artificial, and social systems are seen as interconnected structures whose behavior cannot be understood by studying their parts in isolation but rather through the relationships and flows that bind them together.

From this perspective, surveillance is not simply a technological intervention or legal apparatus, but a multi-layered system involving human actors (data subjects, operators, regulators), technological infrastructures (CCTV, AI-based analytics), normative frameworks (such as the GDPR), and psychological or behavioral feedback loops. This integrated system functions not just through external enforcement but also by shaping internalized behaviors, individuals anticipate being observed and self-regulate accordingly.

Building on GST, Donella Meadows [

40] deepens the understanding of systemic behavior through her influential work on feedback loops and leverage points. She describes systems as inherently adaptive, governed by reinforcing or balancing loops that stabilize or transform their behavior. In the context of surveillance, a balancing feedback loop is evident in how individuals alter their actions based on the perceived presence of monitoring, thereby stabilizing social order without explicit coercion. Meadows’ notion of leverage points, places within a system where small shifts can produce significant systemic change, further suggests that altering public perception, enhancing institutional transparency, or modifying legal interpretations can significantly influence the surveillance ecosystem, often more effectively than technical regulation alone.

Expanding the systems perspective, Niklas Luhmann [

41] offers a sophisticated theory of social systems rooted in differentiation and communication. Rather than treating systems as stable entities, Luhmann views them as operations of distinction, existing only through the continuous differentiation between a system and its environment. A system, in this view, maintains its identity not by its components but by reproducing the difference that separates it from its surroundings. Luhmann identifies three types of systems: psychic, biological, and social—with social systems composed solely of communications. Human beings, accordingly, belong to the environment of social systems, not to the systems themselves. This perspective is especially insightful for analyzing surveillance: it is not the mere presence of observers or technologies that defines surveillance systems, but the symbolic and communicative constructions that determine what is seen, recorded, or acted upon [

42].

In the surveillance context, Luhmann’s insight explains how monitoring practices construct and reinforce normative expectations [

43]. Surveillance mechanisms do not only collect data; they communicate signals about acceptable behavior, deterrence, and deviance. This feedback fosters internalized control, a phenomenon aligned with Michel Foucault’s [

44] concept of the panopticon and compatible with Meadows’ balancing loops.

As Jackson [

45] observes, Luhmann’s theory also accounts for the interactions between distinct systems, each operationally closed yet structurally responsive to environmental perturbations. Drawing on the work of Maturana and Varela [

46], Luhmann introduces the idea of structural coupling and interpenetration to describe how systems—such as law, technology, or behavior—can influence one another through sustained mutual irritations. Though each system evolves based on its own logic, frequent interactions can lead to resonance, a condition where systems adapt in tandem, creating a form of stable co-dependency [

47]. This is particularly applicable to the modern surveillance regime, where legal norms, technological capabilities, and social behaviors co-evolve, shaping and reshaping one another through ongoing informational and normative exchanges.

Taken together, these theorists provide a robust foundation for conceptualizing surveillance as a dynamic and evolving socio-technical system, rather than a static intervention. Such systems function not only through formal regulatory mechanisms, but also through psychological conditioning, symbolic influence, and the ongoing shaping of social norms and legal interpretations. To fully grasp the complexity of surveillance, analysis must extend beyond narrow legalistic or technical perspectives. Instead, an interdisciplinary approach is essential—one that integrates systems theory, behavioral psychology, data protection law, and ethics. Surveillance technologies are never value-neutral; they encode assumptions about control, risk, and social order that shape both their design and implementation. Responding to their systemic consequences thus requires more than regulatory compliance. It demands adaptive governance models that include input from affected individuals, empirical data on behavioral effects, and human-centered design aligned with fundamental rights.

A broader conceptualization of surveillance as a socio-technical system demands regulatory responses that reflect its complexity and multidimensional impact. Legal instruments, while essential, are insufficient if they overlook the behavioral and psychological dynamics that surveillance environments produce. Therefore, normative frameworks must be embedded within adaptive and context-sensitive governance structures, ones capable of addressing not only the technological architecture of surveillance but also its effects on individual autonomy and social behavior. In this regard, the European Union’s data protection framework offers a valuable model for balancing innovation with fundamental rights.

The General Data Protection Regulation [

48], complemented by the guidelines of the European Data Protection Board [

17] and the evolving case law of national Data Protection Authorities (DPAs), imposes clear constraints on the deployment of video surveillance. The foundational principles articulated in Article 5 of the GDPR, such as lawfulness, purpose limitation, and data minimization, function as legal safeguards designed to prevent surveillance practices that exert excessive psychological pressure or compromise individual dignity. These principles reflect a systemic approach to protecting privacy, ensuring that surveillance technologies do not undermine the essential conditions of human autonomy [

49,

50].

A series of significant fines imposed by DPAs aim to curb and penalize surveillance practices deemed to exert disproportionate pressure, ultimately threatening individuals’ right to privacy and anonymity. One of the most notable enforcement cases involved a €10.4 million fine, in which the regulatory authority emphasized that companies must recognize that such intensive video surveillance constitutes a severe violation of employees’ rights. Furthermore, it was underscored that video surveillance represents an especially intrusive infringement on personal rights, as it enables continuous observation and behavioral analysis [

51].

However, there is no uniform case law among DPAs across EU member states, despite the fact that they apply the same regulation, the GDPR. This discrepancy reflects a lack of systemic coherence in regulatory enforcement, suggesting that the GDPR—though designed as a unified legal framework—functions within a fragmented implementation landscape. Such fragmentation underscores the need for interdisciplinary studies that approach surveillance not merely as a legal or technological issue, but as an integral component of a broader socio-technical system. These studies should illuminate how surveillance practices operate within complex regulatory ecosystems, producing feedback loops between legal norms, psychological responses, and institutional behavior. The right to privacy is intrinsically linked to fundamental aspects of human dignity, such as autonomy, self-esteem, and the freedom to act without unwarranted scrutiny—each of which can be impacted by the systemic dynamics of surveillance. Research on regulatory enforcement emphasizes the crucial role of national DPAs in shaping GDPR compliance through case law and administrative decisions [

52,

53], but also reveals how divergent interpretations disrupt system-level consistency. Therefore, this study seeks to provide interdisciplinary arguments that could contribute to the development of a more integrated and coherent practice for ensuring data protection compliance within the system of video surveillance governance.

Grounded in the theoretical framework of behavioral self-censorship under surveillance [

44,

54,

55] and recent studies on the psychological impact of perceived surveillance [

56], this study aims to explore the mechanisms through which video surveillance functions as part of a larger socio-technical system, influencing psychological pressure and behavioral change. By conceptualizing surveillance not merely as a standalone intervention but as a system of interacting technological, legal, and human elements, the study investigates how these components generate feedback loops that shape individual behavior in monitored environments. To systematically examine these effects, the study is structured around two primary objectives, each addressing specific hypotheses designed to capture the dynamic interplay between perceived surveillance and self-regulation.

Research Objectives

Objective 1: The Impact of Perceived Psychological Pressure on Behavioral Adjustments

This objective seeks to determine the extent to which individuals modify their behavior in response to the psychological pressure induced by video surveillance. It focuses on two key aspects [

Appendix A]:

H1: The effect of perceived psychological pressure on behavioral modifications

According to the theory of self-censorship and the panoptic effect [

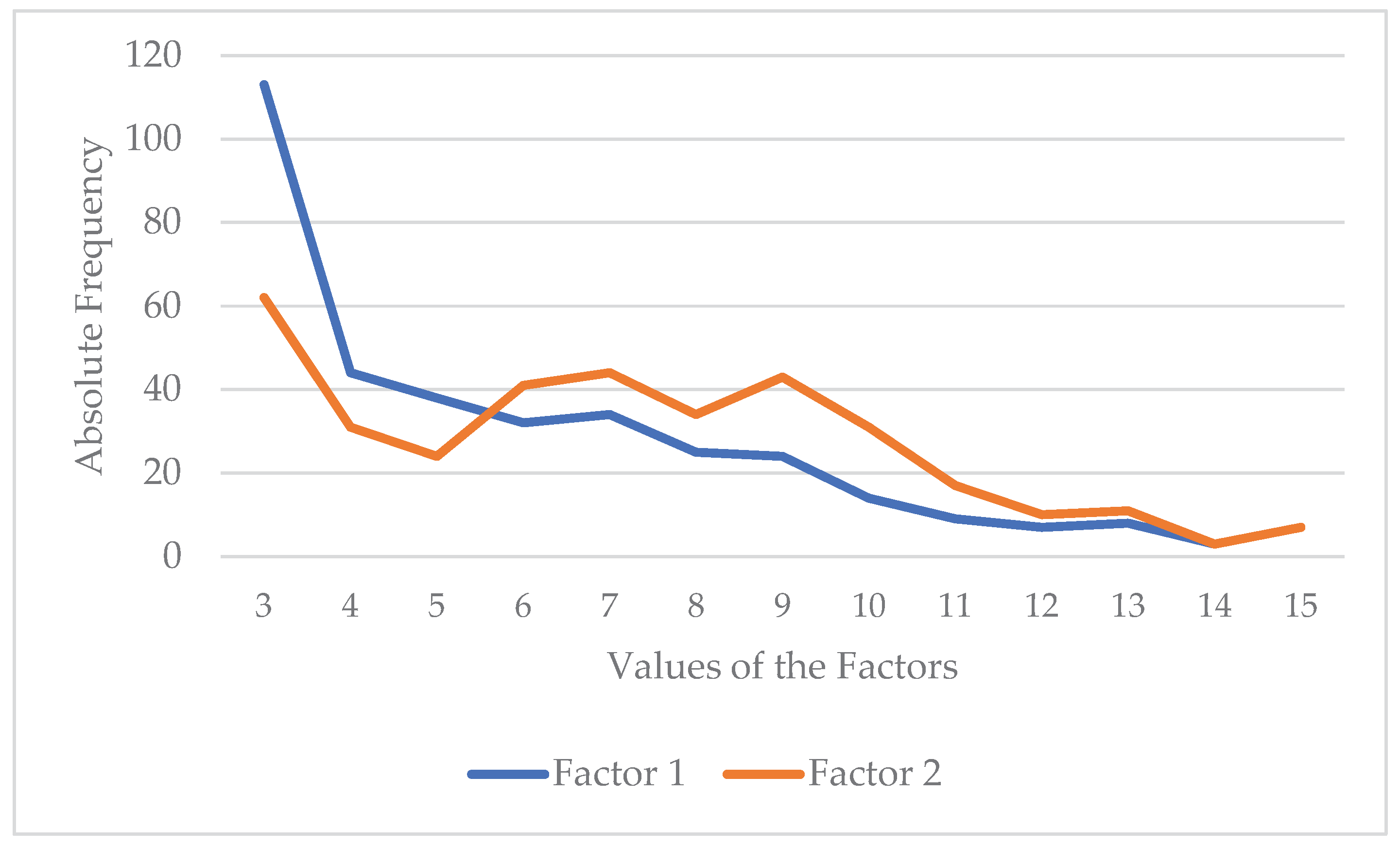

44], individuals who experience heightened psychological pressure due to surveillance tend to regulate their actions to conform to perceived social expectations or avoid negative judgments. This study operationalizes perceived psychological pressure as Factor 1 (aggregating Items 9, 11, and 13), which captures respondents’ discomfort and awareness of constant monitoring. Behavioral modifications are assessed through Factor 2 (Items 7, 8, and 10), which examines the extent to which individuals alter their actions, exhibit greater self-awareness, or suppress certain behaviors in response to surveillance. If a significant relationship is found, it will support the notion that the mere awareness of being watched influences people’s actions, reinforcing the concept of panoptic self-regulation in contemporary surveillance environments.

H2: The effect of belief in active surveillance on behavioral vigilance

Beyond general psychological pressure, the study also examines whether individuals’ perception that video recordings are actively monitored (Item 5) heightens behavioral vigilance in surveilled spaces (Item 7). Social control theory [

57] suggests that when individuals believe they are under direct and active scrutiny, they are more likely to engage in self-regulation to avoid potential repercussions. This hypothesis investigates whether respondents who strongly believe that surveillance footage is reviewed exhibit increased attentiveness to their own behavior, reinforcing the link between perceived oversight and behavioral control mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The present study employed a survey-based methodology, administering a structured questionnaire to undergraduate and master’s students at the Petroleum-Gas University of Ploiesti. From a total student population of 5,132, a sample of 358 participants was obtained.

Prior to administering the questionnaire, a G*Power analysis was conducted to determine the minimum required sample size for ordinal logistic regression. The two-tails analysis was performed using the following parameters: α = 0.05, power (1 – β) = 0.80, odds ratio = 1.5, and P(Y = 1 | X = 1) = 0.5, assuming that the event of interest had an equal probability of occurring in the presence of the predictor. Additionally, Nagelkerke’s R² was set at 0.4, indicating a relatively strong model and a commonly accepted value in studies of this nature [

59]. The choice of Nagelkerke’s R² at 0.4 was made considering that other factors, not included in the study, may also influence the variation in the dependent variable. This is a common occurrence, given that phenomena of this type are typically influenced by multiple factors that are difficult to quantify.

The analysis determined the required sample size of 346 participants.

The final sample comprised individuals aged 18 to 57 years (M = 23.54, SD = 7.387). The gender distribution was 73.5% female and 26.5% male.

All procedures involving human participants adhered to the ethical standards of the Petroleum-Gas University of Ploiesti, as well as the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. To ensure compliance with ethical standards and protect participant confidentiality, no personal data were collected. Prior to participation, respondents received detailed information regarding the anonymous nature of their responses and their right to voluntary participation.

No material incentives or other forms of compensation were offered to participants.

2.2. Design

Factor analysis identified three latent factors with an Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of 0.729 for Perceived Pressure, 0.700 for Behavioral Modification, and 0.548 for Perceived Surveillance Awareness. Confirmatory analysis validated the model, achieving a Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) of 0.998 and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of 0.063. Ordinal logistic regression was used to test hypotheses. Model reliability was confirmed with Cronbach’s Alpha values of 0.835 and 0.836 for the two main factors.

This questionnaire was designed to assess various aspects identified in the academic literature, European Data Protection Board (EDPB) guidelines, and Data Protection Authorities (DPA) case law as potential risks associated with widespread video surveillance. The questionnaire employs a five-point Likert scale to capture respondents’ perceptions and behaviors.

The first category of items evaluates respondents’ interest in the existence of video surveillance in their surroundings (Item 1) and their self-assessed knowledge of the conditions under which video surveillance cameras can be installed (Item 2).

The second category measures respondents’ actions regarding video surveillance, ranging from requesting information about the legality of camera installations (Item 3) to formally contesting being recorded by a surveillance camera (Item 4).

A latent factor capturing the perceived likelihood of identification through video surveillance was constructed by aggregating Items 5 and 6. This factor reflects respondents’ perceptions of the extent to which recorded video footage may be analyzed and used to identify individuals.

Another latent factor measuring the perceived pressure of continuous surveillance and the limitation of anonymity was developed by aggregating Items 9, 11, and 13. This factor aims to capture the extent to which respondents feel constrained by the omnipresence of surveillance cameras, limiting their ability to remain unnoticed in public spaces.

A third factor, assessing behavioral modifications in surveilled spaces, was created by aggregating Items 7, 8, and 10. This factor reflects respondents’ tendency to alter their behavior in response to video surveillance, either by becoming more self-conscious about their actions or by actively modifying their conduct to conform to perceived social norms.

The final category of items examines respondents’ attitudes toward the generalization of video surveillance. Item 14 assesses the extent to which respondents perceive continuous surveillance as a means of enhancing security, measuring their level of comfort with the idea of being monitored throughout their daily activities. Item 15 evaluates the acceptance of the notion that, due to technological advancements, privacy and confidentiality have become obsolete, capturing respondents’ broader perspectives on the implications of surveillance in contemporary society.

2.3. Procedure

Students were informed about the study through the online portals of their respective university departments and faculties. They were provided with details regarding the estimated completion time of 5-7 minutes and were assured that the collected data would be processed solely for scientific purposes. Additionally, they were explicitly informed that personal data would not be disclosed and that respondents’ email addresses were not collected.

The questionnaire was administered individually without the intervention of an interviewer. The data collection method employed was Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI). This method was chosen in alignment with the research objectives, considering the target audience’s accessibility to and preference for digital technology.

The questionnaire consisted exclusively of mandatory questions. To ensure data reliability, response patterns were examined for inconsistencies, particularly in cases where answers to positively and negatively worded items contradicted each other in an implausible manner. Furthermore, the questionnaire was optimized for mobile devices to enhance accessibility and ease of completion.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Factor Analysis

To explore the latent structure of the item set and validate the proposed factorial model, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), followed by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

For the EFA, the factor extraction method used was Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) with Promax rotation. The analysis was based on a polychoric correlation matrix, which more accurately models relationships among ordinal items.

To assess sample adequacy, we employed the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test, which yielded a value of 0.839, indicating a very good fit for factor analysis. To verify the presence of significant correlations among the variables, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was applied. The test result showed a significance level of p < 0.001, suggesting that the data are suitable for factor analysis. In conclusion, the obtained KMO value and the significance level of Bartlett’s test confirm that factor analysis is both appropriate and justified.

Based on the factor loadings of the items on the factors identified by the EFA, as well as the research context, we identified three latent factors: Factor 1 (Perceived Pressure) – Items 9, 11, 13; Factor 2 (Behavioral Modification) – Items 7, 8, 10; Factor 3 (Perceived Surveillance Awareness) – Items 5, 6. Considering that the research variables are ordinal, the Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator was used to determine the CFA indicators, as it is the most appropriate for the data structure. The following results have been obtained. The model fit indices suggest an acceptable fit. The chi-square value for the model was significant, χ²(17) = 41.182, p < 0.001, with a χ²/df ratio of 2.422, indicating an adequate model fit to the data. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) was 0.998, suggesting a good fit between the hypothesized model and the observed data. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.993, the Normed Fit Index (NFI) was 0.988, and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) was 0.989, all of which indicate a strong model fit. Additionally, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.063, suggesting an acceptable model fit. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.028, which indicates a strong model fit. Given that the model involves factors in the analysis, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) indicator was used to assess convergent validity. The AVE values obtained were Factor 1 = 0.729, Factor 2 = 0.700, and Factor 3 = 0.548, indicating an adequate level of convergent validity. Additionally, to evaluate discriminant validity, the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) indicator was used. The HTMT values were: Factor 1 ↔ Factor 2 = 0.848, Factor 1 ↔ Factor 3 = 0.254, Factor 2 ↔ Factor 3 = 0.370. These values suggest an acceptable level of discriminant validity, indicating that the factors are sufficiently distinct from one another.

Overall, these indices support the validity of the three latent factors in explaining the underlying factors that govern individuals’ psychological responses and behavioral adjustments in surveilled environments, confirming the robustness of the proposed factorial structure.

As an indicator of the internal reliability of the item sets forming the factors, Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated for each factor: Factor 1: α = 0.835; Factor 2: α = 0.836; Factor 3: α = 0.587. The first two factors exhibit values greater than 0.8, indicating very good reliability.

For Factor 3, which consists of only two items, the Cronbach’s Alpha value is naturally lower and does not carry significant interpretative weight. As a result, the items within this factor will not be used as an aggregated latent variable. However, the relatively high reliability index, even for a factor with only two items, suggests that they share meaningful common content.

2.4.2. Hypothesis Modelling

To test the proposed hypotheses, the following statistical models will be employed:

H1: An ordinal logistic regression will be conducted, where Factor 1 serves as the predictor, and Factor 2 is the dependent variable.

H2: An ordinal logistic regression will be performed, with Item 5 as the predictor and Item 7 as the dependent variable.

H3: An ordinal logistic regression will be applied, where Item 15 serves as the predictor, and Factor 1 is the dependent variable.

H4: A mediation analysis using ordinal logistic regression will be conducted. Item 13 will serve as the predictor, Item 9 as the mediator, and Item 10 as the dependent variable.

H4a: An ordinal logistic regression will be applied, where Item 13 serves as the predictor, and Item 10 is the dependent variable.

H4b: An ordinal logistic regression will be applied, where Item 13 serves as the predictor, and Item 9 is the dependent variable.

H4c: An ordinal logistic regression will be applied, where Item 9 serves as the predictor, and Item 10 is the dependent variable.

H4d: An ordinal logistic regression will be applied, where Item 13 and Item 9 serve as predictors, and Item 10 is the dependent variable.

Before conducting the ordinal logistic regression analysis, key assumptions were verified to ensure the validity of the model.

For the interpretation of the obtained values, the following significance thresholds were applied. A p-value < 0.05 in the Model Fitting Information test indicates that the model with predictors provides a significantly better fit than the null model. A p-value > 0.05 in the Goodness-of-Fit test suggests that the selected model adequately represents the data. Likewise, a p-value > 0.05 in the Test of Parallel Lines confirms that the predictor coefficients remain stable across all threshold levels, thereby supporting the proportional odds assumption.

The Pseudo R-Square values offer an indication of the extent to which predictor variability explains the variance in the dependent variable. While these values do not have a direct interpretation equivalent to R² in linear regression, they serve as a general measure of model acceptability. Additionally, given that Pearson’s test is highly sensitive to small or zero-frequency cells, it may tend to reject otherwise valid models. Regarding the acceptance of the H4b model, the observed Pseudo R-Square values, along with the significance level of the Deviance test, provide robust statistical justification for considering the model appropriate.

Data presented in

Table 1 confirms that all required conditions for implementing the proposed models have been met, further supporting their validity and applicability within the research framework.

3. Results

To test H1, H2, and H3, ordinal logistic regression analyses were performed under the proportional odds assumption, utilizing the Logit function.

The results of the ordinal logistic regression model for H1 (

Table 2) confirm the statistical significance of both the predictor and the threshold estimates. The threshold values (αj) indicate the cumulative log-odds of transitioning between adjacent categories of the dependent variable. These estimates progressively increase from α

3 = 1.240 (SE = 0.235, p < 0.001) to α

14 = 9.562 (SE = 0.635, p < 0.001), highlighting the ordered nature of the dependent variable. The standard errors of the thresholds gradually increase at higher response levels, suggesting a limited number of observations in extreme categories, which is a common occurrence in ordinal logistic regression. The widening of the confidence intervals for higher thresholds further reflects this pattern, indicating greater variability in these regions.

The predictor coefficient (β = 0.603, SE = 0.042, Wald = 201.783, p < 0.001) confirms a statistically significant relationship between independent and dependent variables. The positive coefficient suggests that an increase in the predictor is associated with higher odds of transitioning to a superior category. The significance of the Wald test and the relatively narrow confidence interval (CI = [0.520, 0.686]) reinforce the robustness of this effect.

To verify the stability of the model, the PROCESS macro for SPSS [

60] was applied using 10,000 bootstrap resamples with bias correction. The analysis of the obtained results indicates that only one bias exceeds 0.1, corresponding to the last threshold (α

14). This discrepancy is solely attributed to the limited number of observations near this threshold. Furthermore, an additional argument supporting the model’s reliability is that the predictor coefficient exhibits a very small bias of 0.005, reinforcing the overall stability of the estimates.

The overall pattern of results supports the proportional odds assumption, as the predictor’s effect appears stable across different levels of the dependent variable. However, the increasing standard errors for higher thresholds indicate a potential data sparsity issue in these extreme categories.

These findings confirm that the predictor exerts a meaningful influence on the dependent variable, demonstrating a clear and statistically significant effect. The model appears well-fitted, and while the sparsity of observations in extreme categories may introduce some variability, the overall estimates remain stable and reliable.

Figure 1 provides a graphical interpretation of the Logit coefficient, illustrating that for a one-unit increase in the predictor, the odds of transitioning to a higher category in the dependent variable increase by approximately 1.83 times.

The results of the ordinal logistic regression analysis for H2 (

Table 3) confirm the statistical significance of both the predictor and the majority of the threshold estimates. The threshold values define the cumulative log-odds for transitioning between adjacent categories of the dependent variable. While the first threshold (α

1 = 0.493, p = 0.138) is not statistically significant, indicating a weaker distinction between the lower response categories, the subsequent thresholds are highly significant at p < 0.001, reinforcing the ordered nature of the dependent variable. The progressive increase in threshold values suggests a clear transition between response levels, with larger differences observed at the upper categories, which aligns with the expectations of an ordinal model.

The predictor coefficient (β = 0.534, SE = 0.104, Wald = 26.381, p < 0.001) indicates a strong and statistically significant effect. The positive coefficient suggests that an increase in the predictor is associated with a higher probability of transitioning to a superior category of the dependent variable. The confidence interval (0.330 – 0.738) does not include zero, further confirming the robustness of the estimated relationship.

To assess model stability, a bootstrap analysis with 10,000 resamples was conducted. The results indicate that all bias values are below 0.05, both for the threshold estimates and the predictor coefficient, suggesting that the model provides stable and reliable estimates without significant distortions introduced by resampling.

A relevant aspect that may influence the interpretation of the results is the imbalanced distribution of the predictor across the categories of the dependent variable. In the first category, the predictor accounts for only 2% of the total observations, which may affect the precision of estimates at this level. This unequal distribution may explain the lack of significance for the first threshold, suggesting a possible aggregation of observations in the upper categories and a potential need to reconsider the granularity of the lower levels.

Overall, the results support the proportional odds assumption, as the predictor’s effect remains stable across all categories of the dependent variable. However, the non-significance of the first threshold, combined with the low representation of the predictor in the lowest category, may indicate a tendency for response clustering in the higher levels.

The results of the ordinal logistic regression model for H3 (

Table 4) confirm the statistical significance of the predictor and most of the threshold estimates.

The threshold values exhibit a progressive increase from α3=0.022 (SE = 0.366, p = 0.952) to α14=4.748 (SE = 0.528, p < 0.001), emphasizing the ordered nature of the dependent variable. The standard errors of the thresholds tend to increase at higher response levels, particularly for α14, where SE reaches 0.528. This pattern suggests a reduced number of observations in extreme categories, a common characteristic in ordinal logistic regression. The broadening of confidence intervals for higher thresholds (e.g., CI for α14 is [3.714, 5.782]) further reflects this trend, indicating increased variability in these regions.

The predictor coefficient (β=0.222, SE = 0.096, Wald = 5.349, p = 0.021) establishes a statistically significant relationship between the independent and dependent variables. The positive coefficient suggests that an increase in the predictor variable is associated with higher odds of transitioning to a superior category. The significance of the Wald test, coupled with the confidence interval (CI = [0.034, 0.411]), reinforces the robustness of this effect, though the magnitude of influence remains moderate.

While the proportional odds assumption appears to hold overall, the increasing standard errors for higher thresholds indicate potential sparsity in extreme response categories. Nevertheless, the findings confirm that the predictor exerts a meaningful and statistically significant effect on the dependent variable.

The mediation analysis applied within the ordinal logistic regression framework confirms significant relationships between the predictor, mediator, and dependent variable. The direct effect of the predictor on the dependent variable (H4a) is significant (β=1.108, SE = 0.099, Wald = 125.847, p < 0.001, CI = [0.914, 1.302]), indicating a strong positive influence

Table 5).

The relationship between the predictor and mediator (H4b) is even stronger (β=1.291, SE = 0.105, Wald = 151.503, p < 0.001, CI = [1.085, 1.496]) (

Table 6), while the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable (H4c) is the most pronounced (β=1.430, SE=0.108, Wald = 174.699, p < 0.001, CI = [1.218, 1.642]) (

Table 7).

The inclusion of additional predictors (H4d) (

Table 8) reveals that Item 9 (β=1.157, SE = 0.121, Wald = 92.095, p < 0.001, CI = [0.921, 1.393]) has a greater impact on the dependent variable than Item 13 (β=0.513, SE = 0.112, Wald = 21.087, p < 0.001, CI = [0.294, 0.732]).

Bootstrap resampling (10,000 iterations,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12) confirms the stability of the estimates, with minimal bias and consistent confidence intervals.

These findings support the validity of the mediation model and indicate a significant indirect effect of the predictor on the dependent variable through the mediator, reinforcing the hypothesis that intermediary mechanisms play a crucial role in the relationship between variables.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide compelling evidence that video surveillance systems exert a significant psychological impact, leading to observable behavioral modifications in individuals subjected to continuous monitoring. By examining the interrelations between perceived psychological pressure, belief in active surveillance, and the perceived omnipresence of surveillance technologies, the study contributes to a systemic understanding of how surveillance environments operate as socio-technical systems that shape human behavior. These systems function through recursive feedback loops in which technological infrastructures, cognitive perceptions, and behavioral adaptations interact dynamically. The results are consistent with established theoretical frameworks, particularly Foucault’s [

44] concept of the Panopticon and Zuboff’s [

56] theory of surveillance capitalism, reinforcing the idea that the mere perception of being observed activates mechanisms of internalized control, resulting in behavioral self-regulation and conformity.

The results confirmed H1, indicating that perceived psychological pressure significantly influences behavioral modifications. The factor analysis demonstrated that individuals who experience higher levels of discomfort and heightened awareness of constant monitoring (Factor 1) are more likely to alter their actions, exhibit greater self-awareness, or suppress certain behaviors (Factor 2). This supports Foucault’s panoptic self-regulation theory, which suggests that surveillance fosters a form of internalized discipline, where individuals proactively conform to perceived social expectations to avoid negative scrutiny.

Further, H2 was supported by the findings, showing that the belief in active surveillance (Item 5) heightened behavioral vigilance in surveilled spaces (Item 7). The statistically significant relationship between these variables confirms the premise of social control theory [

57], which posits that individuals who believe their actions are actively monitored are more likely to engage in self-regulation. From a systems perspective, this illustrates how surveillance functions as a feedback mechanism within a broader socio-technical system, where belief in observation alone can trigger behavioral adjustments without the need for direct intervention. Similarly, Yesil [

4] and Shapiro [

5] emphasize that surveillance in urban spaces is designed not just to deter criminal activity but also to subtly guide and control social behavior. This finding thus highlights a key psychological pathway within surveillance systems: the perception of being observed becomes a systemic input that modifies behavioral outputs, reinforcing control through internalized awareness rather than external enforcement.

The study also found support for H3, indicating that the perceived omnipresence of surveillance technology (Item 15) significantly amplifies psychological pressure (Factor 1). This finding aligns with the literature [

55,

56], which suggests that advancements in surveillance technology have led to a widespread perception that monitoring is continuous and inescapable. Individuals who perceive surveillance as omnipresent experience higher levels of psychological distress, reinforcing the argument that modern technological surveillance fosters a persistent state of self-regulation. This psychological impact is further supported by McCahill and Finn [

29], who argue that the normalization of surveillance in contemporary societies creates a culture of suspicion, in which individuals continuously evaluate their actions based on the possibility of being observed. The results also align with Monahan [

27], who highlights that the expansion of surveillance technology contributes to feelings of alienation and distrust, as people become increasingly aware that their movements, interactions, and decisions may be monitored and assessed.

The mediation analysis confirmed H4, demonstrating that immediate psychological pressure (Item 9) serves as an intermediary mechanism through which concerns about lifestyle monitoring (Item 13) lead to behavioral modifications (Item 10). This supports Staples’ [

2] assertion that surveillance-related anxiety does not always directly alter behavior but operates through intermediate emotional and cognitive responses. The study found that macro-level concerns about surveillance gradually translate into real-time psychological discomfort, which, in turn, results in behavioral self-regulation.

These findings have significant implications for both policy and practice, particularly when surveillance is viewed as part of an interconnected socio-technical system. The results underscore the need for regulatory frameworks that account not only for legal compliance but also for the unintended psychological and behavioral consequences that emerge from systemic interactions between surveillance technologies and human perception. While the GDPR provides essential safeguards against excessive and disproportionate monitoring, emphasizing principles such as lawfulness, purpose limitation, and data minimization, this study demonstrates that even lawful surveillance can generate psychological pressure that indirectly constrains individual autonomy. In this context, surveillance functions as a regulatory system in itself, influencing behavior through internalized norms rather than formal sanctions. The role of Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) is therefore critical: their interventions serve as external control mechanisms that can realign system behavior with fundamental rights. Cases in which organizations have been fined for intrusive video surveillance practices show that regulatory bodies acknowledge the broader systemic impact on individuals’ rights and freedoms. These fines should not be viewed merely as punitive measures, but as corrective signals within a dynamic compliance system. Given the complexity of surveillance ecosystems, GDPR enforcement must integrate legal, psychological, and behavioral perspectives to ensure holistic protection of individual rights in increasingly monitored environments.

The study advances the theoretical understanding of surveillance and self-regulation by situating psychological and behavioral responses within the dynamics of complex socio-technical systems. By demonstrating that the mere perception of surveillance can activate self-censorship, the research reinforces prior work on behavioral regulation under conditions of perceived observation [

44,

56], illustrating how internalized monitoring functions as a feedback mechanism within a broader system of social control. This systemic perspective highlights that surveillance does not operate in isolation but as part of an interactive network of technologies, norms, and individual cognition.

Furthermore, the study contributes to ongoing debates about the erosion of anonymity in public spaces, showing that widespread surveillance diminishes the capacity for individuals to navigate social environments without being subject to observation or profiling. This contributes to a systemic contraction of expressive freedom, as individuals adapt their behavior not in response to direct intervention, but to the implicit conditions of monitored environments. Echoing Arendt’s [

26] concerns about the loss of the public realm, the findings emphasize a growing societal challenge: how to maintain a resilient equilibrium between the functional imperatives of security systems and the preservation of fundamental freedoms in democratic societies.

5. Conclusions

This study provides empirical and theoretical insights into the behavioral and psychological impacts of video surveillance, framing it as a component of a broader socio-technical system. By demonstrating that the mere perception of being monitored can lead to self-censorship and behavioral adaptation, the research supports the conceptualization of surveillance as a dynamic feedback mechanism that influences individual agency through internalized control. The statistically significant relationships between perceived psychological pressure, belief in active monitoring, and the omnipresence of surveillance technologies underscore how behavioral regulation emerges not only from formal enforcement but also from the anticipatory actions of individuals navigating surveilled environments.

These findings contribute to the growing literature that treats surveillance as a complex system involving interactions among legal norms, technological infrastructures, and psychological processes. For systems scholars, the study offers concrete evidence of how feedback loops, symbolic control, and emergent behavioral norms operate within socio-technical systems. It illustrates how subtle regulatory mechanisms, like perceived observation, can stabilize or disrupt system behavior without direct coercion. Moreover, it suggests potential leverage points (in the Meadowsian sense) where small interventions in public perception or regulatory communication could produce disproportionate systemic effects. This opens up pathways for modeling behavioral dynamics in adaptive governance systems and supports a shift in surveillance analysis from static design to evolving interaction patterns.

While the GDPR provides a uniform legal framework, the divergence in enforcement practices across Data Protection Authorities reveals systemic inconsistencies that can affect the broader social perception of privacy rights and technological governance. In regulatory terms, the study suggests that DPAs should not only consider legal compliance but should also evaluate surveillance systems in terms of their behavioral and psychological impact. This implies that the assessment of video surveillance systems must place at the center of the analysis the need to preserve the intrinsic characteristics of the human being, and should not allow data controllers to create a mere appearance of legality through a strictly technical interpretation of GDPR provisions.

The findings also highlight broader societal risks associated with the erosion of the public realm, a theme articulated by Hannah Arendt [

26] and revisited in light of contemporary surveillance practices. In societies where individuals fear scrutiny or judgment in public spaces, the conditions for democratic participation and civic engagement are weakened. Surveillance, when normalized and internalized, may discourage protest, dissent, or even casual acts of expression. These consequences are particularly concerning in democratic societies, where freedom of assembly and expression are foundational rights. The challenge, therefore, lies in designing surveillance systems that uphold security and efficiency without compromising the psychological and behavioral conditions necessary for a free and open society.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations, particularly in the context of understanding surveillance as a complex socio-technical system. First, the reliance on self-reported survey data introduces potential biases, such as social desirability effects, which may influence participants’ responses. Future research could adopt experimental or behavioral observation methods to more accurately capture real-time behavioral adaptations within surveilled environments, thereby enriching system-level understanding through multi-modal data sources.

Second, the sample was drawn exclusively from a university population, which may limit the generalizability of findings across broader demographic or institutional settings. To better model how surveillance systems function across varied social contexts, future studies should include diverse populations, including workplace and urban surveillance scenarios, which operate under different behavioral and normative pressures.

Third, while the study identified a clear relationship between perceived surveillance and behavioral modification, it did not account for moderating variables such as individual differences in privacy sensitivity, prior exposure to surveillance, or personality traits. Integrating such factors into future models could enhance the explanatory power of surveillance systems by recognizing human heterogeneity as a critical system variable. Finally, the growing implementation of artificial intelligence-driven surveillance—such as facial recognition and predictive analytics—adds further layers of opacity and complexity to these systems. These technologies alter the structure and perception of surveillance by introducing automated decision-making elements, which may amplify behavioral self-regulation and erode individual autonomy in new ways.

Overall, this study offers strong empirical support for the hypothesis that video surveillance exerts psychological pressure, thereby triggering self-regulatory behaviors that align with system-level feedback dynamics. The findings underscore the need for surveillance policies to consider not only legal frameworks but also psychological and behavioral consequences emerging from these socio-technical assemblages. As video monitoring becomes increasingly embedded in daily life, it is essential that policymakers, regulators, and designers of surveillance systems ensure that such technologies do not undermine fundamental human freedoms. By bridging theoretical models with empirical data, this study contributes to a growing interdisciplinary discourse on surveillance, self-censorship, and autonomy within complex digital ecosystems.

Future research should continue to examine these systems holistically, incorporating diverse populations, contextual factors, and emerging surveillance technologies such as AI-driven analytics and facial recognition. As surveillance infrastructures become increasingly embedded in daily life, maintaining a balance between public safety and individual autonomy will require interdisciplinary collaboration between technologists, legal scholars, behavioral scientists, and policymakers. The results presented here serve as a foundation for that dialogue, highlighting the need for surveillance systems that are not only effective but also ethically and psychologically sustainable. Ultimately, understanding surveillance through a systems lens enables more adaptive, accountable, and ethically grounded governance, where technological efficiency is harmonized with the preservation of fundamental human values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.V. and D.G.I.; methodology, D.G.I.; formal analysis, D.G.I.; resources, D.V.; writing—original draft preparation, D.V. and D.G.I.; writing—review and editing, D.V. and D.G.I.; funding acquisition, D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Petroleum-Gas University of Ploiesti, grant number GO-GICS-30813/11.12.2024.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire.

| Code |

Item |

| Item 1 |

In general, how interested are you in whether the space you are in is under video surveillance? |

| Item 2 |

To what extent do you know the conditions under which video surveillance cameras can be installed in a space? |

| Item 3 |

Have you ever requested information regarding the legality of installing video surveillance cameras in a specific space? |

| Item 4 |

Have you ever challenged the fact that you are being recorded by a video surveillance camera? |

| Item 5 |

Do you believe that video recordings are analyzed by those who conduct the surveillance? |

| Item 6 |

How likely do you think it is that, under normal conditions, you could be identified in a video recording? |

| Item 7 |

When entering a space that is under video surveillance, are you more attentive than usual to your gestures? |

| Item 8 |

Have there been situations where you refrained from making a gesture in a video-surveilled space for fear that it might be perceived as abnormal by those who have access to the recordings? |

| Item 9 |

Have you ever felt discomfort or pressure from being recorded while carrying out everyday activities (e.g., shopping, participating in recreational activities, etc.)? |

| Item 10 |

Do you believe that video surveillance changes the way you behave? |

| Item 11 |

In a video-surveilled space, have you ever felt the need to avoid the cameras’ field of view because you did not want it to be known that you were in that space? |

| Item 12 |

In a video-surveilled space, have you ever felt the need to avoid the cameras’ field of view because you did not want it to be known that you were participating in a certain activity or using a particular service? |

| Item 13 |

Have you ever felt discomfort or pressure from the possibility that, due to video surveillance, your lifestyle could be detected and analyzed? |

| Item 14 |

Would you feel safe if there were continuous video monitoring from the moment you leave your home until you return? |

| Item 15 |

To what extent do you agree with the statement: “Nowadays, everything you do is known anyway”? |

References

- Lyon, D. Surveillance Society: Monitoring Everyday Life; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Staples, W.G. Everyday Surveillance: Vigilance and Visibility in Postmodern Life, 2nd ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Purnell, N. A world with a billion cameras watching you is just around the corner. Wall Str. J. 2019. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-billionsurveillance-cameras-forecast-to-be-watching-within-two-years-11575565402 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Yesil, B. Video Surveillance: Power and Privacy in Everyday Life; LFB Scholarly Publishing: El Paso, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, A. Design, Control, Predict: Logistical Governance in the Smart City; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer, J.; Lipartito, K. (Eds.) Surveillance Capitalism in America; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bodie, M.T. The law of employee data: Privacy, property, governance. Ind. Law J. 2022, 97, 707–748. [Google Scholar]

- Rule, J.B. Privacy in Peril: How We Are Sacrificing a Fundamental Right in Exchange for Security and Convenience; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Macnish, K. The Ethics of Surveillance: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan, T. Crisis Vision: Race and the Cultural Production of Surveillance; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, A.M.; Giebels, E.; van Rompay, T.J.L.; Junger, M. The influence of the presentation of camera surveillance on cheating and pro-social behavior. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volosevici, D. Some Considerations on Video-Surveillance and Data Protection. Jus Civitas J. Soc. Legal Stud. 2018, 69, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Merrick, R.; Ryan, S. Data privacy governance in the age of GDPR. Risk Manag. 2019, 66, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Aas, K.F.; Gundhus, H.O.; Lomell, H.M. Technologies of Insecurity: The Surveillance of Everyday Life; Routledge-Cavendish: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, J.M. Performance, Transparency, and the Cultures of Surveillance; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, K. Surveillance in the workplace: Past, present, and future. Surveill. Soc. 2022, 20, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Data Protection Board (EDPB). Guidelines 3/2019 on Processing of Personal Data through Video Devices. 2019. Available online: https://edpb.europa.eu (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Kaplan, S. To be a face in the crowd: Surveillance, facial recognition, and a right to obscurity. In Everyday Life in the Culture of Surveillance; Samuelsson, L., Cocq, C., Gelfgren, S., Enbom, J., Eds.; Nordicom, University of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2023; pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J. Citizen Spies: The Long Rise of America’s Surveillance Society; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, C.; Armstrong, G. The Maximum Surveillance Society: The Rise of CCTV; Berg: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alfino, M.; Mayes, G.R. Reconstructing the right to privacy. Soc. Theory Pract. 2003, 29, 1–18. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23559211 (accessed on 10 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bentham, J. Panopticon; T. Payne: London, UK, 1791. [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty, K.D.; Samatas, M. (Eds.) Surveillance and Democracy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.E. Configuring the Networked Self: Law, Code, and the Play of Everyday Practice; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, D. The Culture of Surveillance; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H. The Human Condition; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan, T. Surveillance in the Time of Insecurity; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard-Wills, D. Surveillance and Identity: Discourse, Subjectivity and the State; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McCahill, M.; Finn, R.L. Surveillance, Capital and Resistance: Theorizing the Surveillance Subject; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rachels, J. Why privacy is important. Philos. Public Aff. 1975, 4, 323–333. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2265077 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Vélez, C. Privacy Is Power: Why and How You Should Take Back Control of Your Data; Melville House: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, I.; Wildhaber, I.; Adams-Prassl, J. Big data in the workplace: Privacy due diligence as a human rights-based approach to employee privacy protection. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8, 20539517211013051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, F. Fear, Risk and the First Amendment: Unraveling the Chilling Effect. Faculty Publ. 1978, 879. Available online: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/879 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Solove, D.J. A taxonomy of privacy. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 2006, 154, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solove, D.J. Understanding Privacy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nissenbaum, H. Privacy in Context: Technology, Policy, and the Integrity of Social Life; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, G.T. Windows into the Soul: Surveillance and Society in an Age of High Technology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy, L. von. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy, L. von. Perspectives on General System Theory: Scientific-Philosophical Studies; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Wright, D., Ed.; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Social Systems; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Introduction to Systems Theory; Barrett, P., Ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, H.G. Luhmann Explained: From Souls to Systems; Open Court: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison; Sheridan, A., Trans.; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977.

- Jackson, M. Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding, 2nd ed.; Shambhala Publications: Boulder, CO, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tabilo Álvarez, J.; Ramírez Correa, P. Brief Review of Systems, Cybernetics, and Complexity. Complexity 2023, 8205320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679). 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&from=EN (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Ogriseg, C. GDPR and Personal Data Protection in the Employment Context. Labour Law Issues 2017, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuner, C.; Bygrave, L.A.; Docksey, C.; Drechsler, L.; Tosoni, L. The EU General Data Protection Regulation: A Commentary/Update of Selected Articles. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der Landesbeauftragte für den Datenschutz Niedersachsen. LfD Niedersachsen verhängt Bußgeld über 10,4 Millionen Euro gegen notebooksbilliger.de. 2021. Available online: https://www.lfd.niedersachsen.de/startseite/infothek/presseinformationen /lfd-niedersachsen-verhangt-bussgeld-uber-10-4-millionen-euro-gegen-notebooksbilliger-de-196019.html (accessed on 7 Febru-ary 2025).

- Kamarinou, D.; Van Alsenoy, B. Data protection law in the EU: Roles, responsibilities, and liability. Int. Data Priv. Law 2020, 10, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hert, P.; Papakonstantinou, V. The new general data protection regulation: Still a sound system for the protection of individuals. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2016, 32, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissenbaum, H. Protecting privacy in an information age: The problem of privacy in public. Law Philos. 1998, 17, 559–596. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3505189 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Lyon, D. Surveillance Studies: An Overview; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zuboff, S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power; PublicAffairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, G.T. What’s new about the “new surveillance”? Classifying for change and continuity. Surveill. Soc. 2002, 1, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henschke, A. Ethics in an Age of Surveillance: Personal Information and Virtual Identities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. The Acceptable R-Square in Empirical Modelling for Social Science Research. In Social Research Methodology and Publishing Results: A Guide to Non-Native English Speakers; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).