Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Significance

1. Introduction

1.1.

1.2.

1.3.

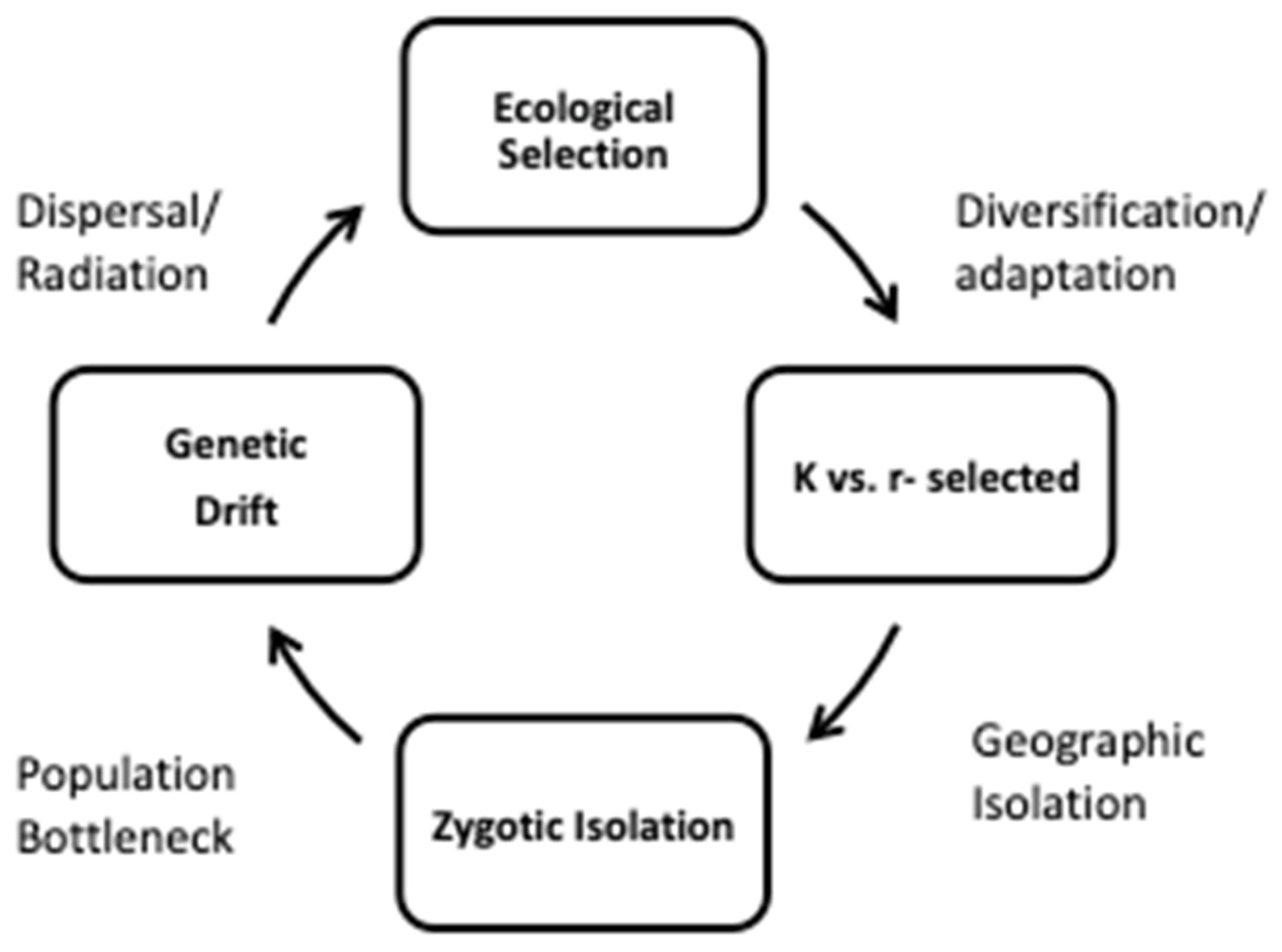

- 1)

- geographic isolation following a population split.

- 2)

- neutral (non-genic) karyotype diversification driven by genetic drift, eventually involving genes in species with small effective population sizes (microevolution).

- 3)

- reproductive (pre and post-zygotic) isolation separating diverged populations (for example, ring species).

- 4)

- ecological selection driving speciation and adaptive radiation into newly evolved niches (macroevolution).

1.4.

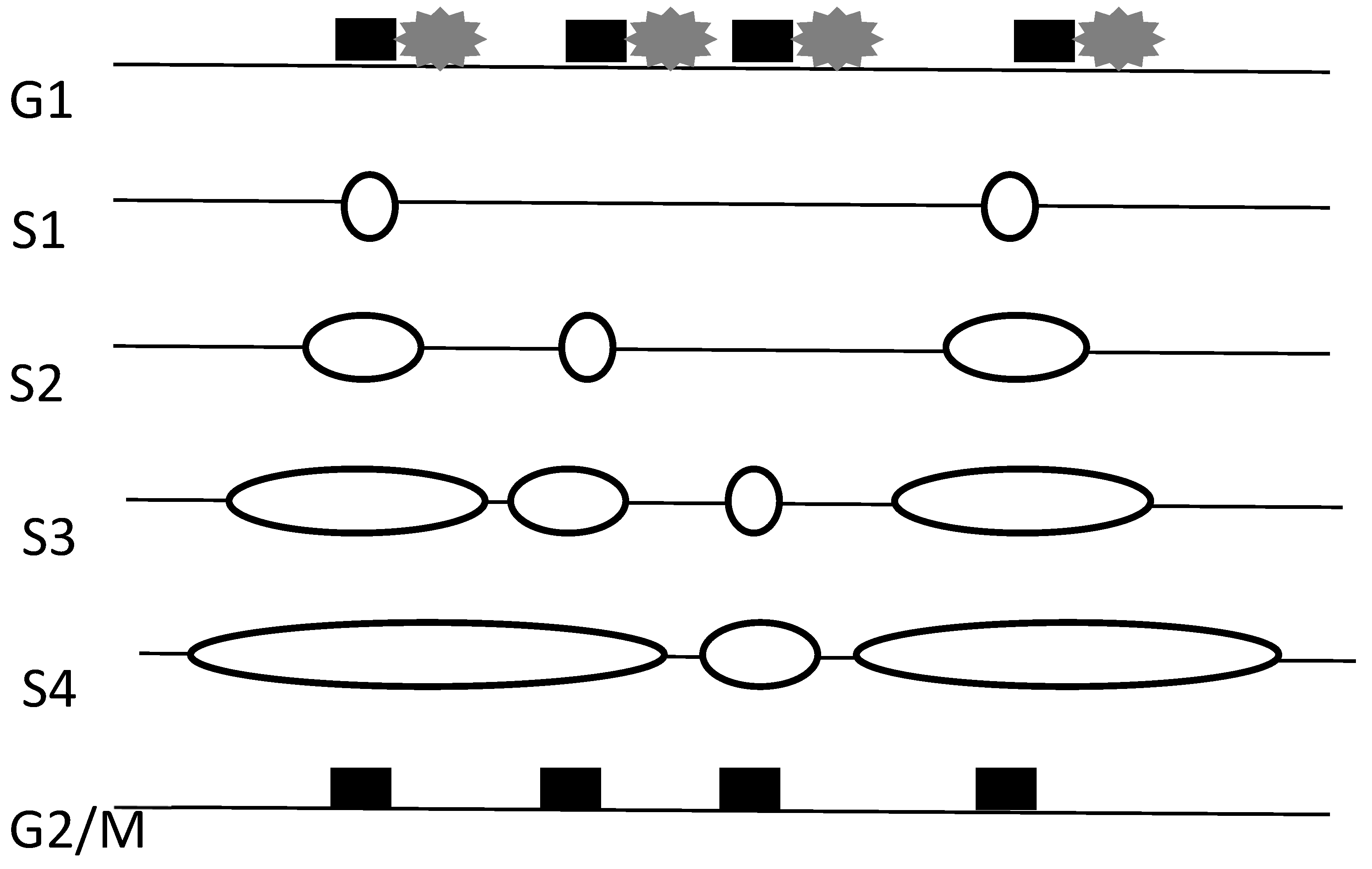

2.1. RT and Replication Origins

3.3. RT and protein folding versus protein function

4.1. RT and Genome Stability

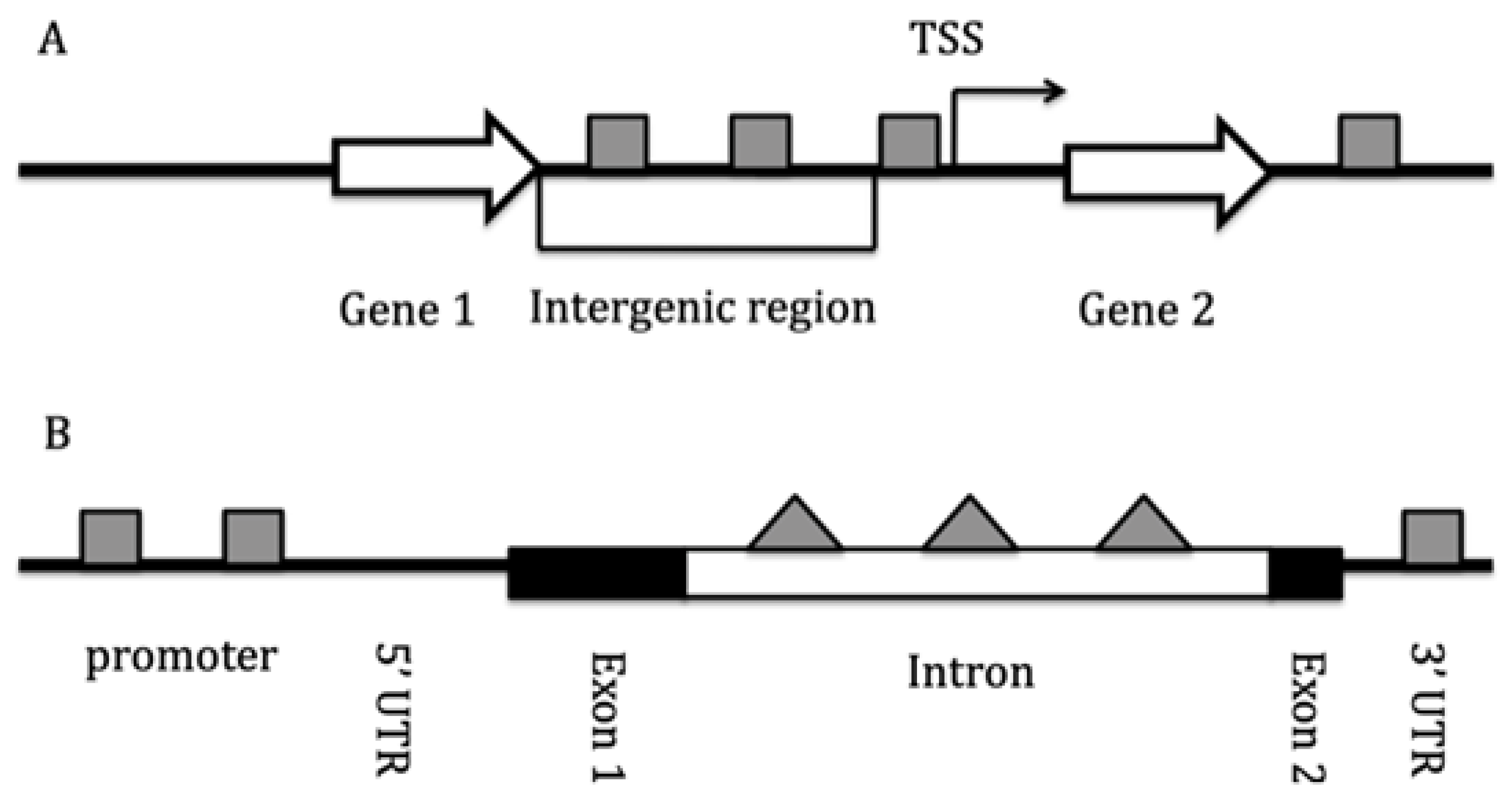

4.2. RT and Introns as Adaptations to DNA Damage

4.3. RT and DNA Repair

5.1. RT and Genome Evolution: a RT Molecular Clock?

5.2. RT and the Correlation between dN and dS

6.1. RT and Transposable Elements

6.2. RT and Two Potential Proxy Variables for Genome Stability?

6.3. Genome Stability and Life History Traits

7. Conclusions

References

- Bush, G.L.; Case, S.M.; Wilson, A.C.; Patton, J.L. Rapid speciation and chromosomal evolution in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1977, 74, 3942–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxson, L. E. , & Wilson, A. C. (1979). Rates of molecular and chromosomal evolution in salamanders. Evolution, 734-740.

- Levin, D.A.; Wilson, A.C. Rates of evolution in seed plants: Net increase in diversity of chromosome numbers and species numbers through time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1976, 73, 2086–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prachumwat, A.; Li, W.-H. Gene number expansion and contraction in vertebrate genomes with respect to invertebrate genomes. Genome Res. 2007, 18, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Martinez, P.; Jacobina, U.P.; Fernandes, R.V.; Brito, C.; Penone, C.; Amado, T.F.; Fonseca, C.R.; Bidau, C.J. A comparative study on karyotypic diversification rate in mammals. Heredity 2016, 118, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.K.; Kretschmer, R.; Srikulnath, K.; Singchat, W.; O’cOnnor, R.E.; Romanov, M.N. Insights into avian molecular cytogenetics—with reptilian comparisons. Mol. Cytogenet. 2024, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simakov, O.; Marlétaz, F.; Yue, J.-X.; O’cOnnell, B.; Jenkins, J.; Brandt, A.; Calef, R.; Tung, C.-H.; Huang, T.-K.; Schmutz, J.; et al. Deeply conserved synteny resolves early events in vertebrate evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.P.; Palumbi, S.R. Body size, metabolic rate, generation time, and the molecular clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993, 90, 4087–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarich, V.M.; Wilson, A.C. Immunological Time Scale for Hominid Evolution. Science 1967, 158, 1200–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bininda-Emonds, O.R.P. Fast Genes and Slow Clades: Comparative Rates of Molecular Evolution in Mammals. Evol. Bioinform. 2007, 3, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, S.B.; Marin, J.; Suleski, M.; Paymer, M.; Kumar, S. Tree of Life Reveals Clock-Like Speciation and Diversification. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, L.T. Molecular evolutionary rates predict both extinction and speciation in temperate angiosperm lineages. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 162–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldie, X.; Lanfear, R.; Bromham, L. Diversification and the rate of molecular evolution: no evidence of a link in mammals. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011, 11, 286–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPeek, M.A.; Brown, J.M. Clade Age and Not Diversification Rate Explains Species Richness among Animal Taxa. Am. Nat. 2007, 169, E97–E106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundle, H. D. , & Nosil, P. ( 8(3), 336–352.

- Futuyma, D. The origin of species by means of ecological selection. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R217–R219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, D.; Edie, S.M. Mass extinctions and their rebounds: a macroevolutionary framework. Paleobiology 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, J.P.; Wiens, J.J. Diversification rates and species richness across the Tree of Life. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20161334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMalach, N.; Ke, P.; Fukami, T. The effects of ecological selection on species diversity and trait distribution: predictions and an empirical test. Ecology 2021, 103, e03567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellborn, G.A.; Langerhans, R.B. Ecological opportunity and the adaptive diversification of lineages. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, H. On the Generality of the Latitudinal Diversity Gradient. Am. Nat. 2004, 163, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willig, M.R.; Kaufman, D.M.; Stevens, R.D. Latitudinal Gradients of Biodiversity: Pattern, Process, Scale, and Synthesis. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 273–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemske, D.W.; Mittelbach, G.G. “Latitudinal Gradients in Species Diversity”: Reflections on Pianka’s 1966 Article and a Look Forward. Am. Nat. 2017, 189, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureš, P.; Elliott, T.L.; Veselý, P.; Šmarda, P.; Forest, F.; Leitch, I.J.; Nic Lughadha, E.; Gomez, M.S.; Pironon, S.; Brown, M.J.M.; et al. The global distribution of angiosperm genome size is shaped by climate. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianka, E.R. Latitudinal Gradients in Species Diversity: A Review of Concepts. Am. Nat. 1966, 100, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Wiens, J.J. The causes of species richness patterns among clades. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2024, 291, 20232436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.J. Trait-based species richness: ecology and macroevolution. Biol. Rev. 2023, 98, 1365–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiserhardt, W.L.; Hansen, L.E.S.F.; Couvreur, T.L.P.; Dransfield, J.; Ferreira, P.d.L.; Rakotoarinivo, M.; Bellot, S.; Baker, W.J. Explaining extreme differences in species richness among co-occurring palm clades in Madagascar. Evol. J. Linn. Soc. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietje, M.; Antonelli, A.; Baker, W.J.; Govaerts, R.; Smith, S.A.; Eiserhardt, W.L. Global variation in diversification rate and species richness are unlinked in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Insua, A.; Gómez-Rodríguez, C.; Wiens, J.J.; Baselga, A. Climatic niche divergence drives patterns of diversification and richness among mammal families. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Title, P.O.; Burns, K.J.; Mooers, A. Rates of climatic niche evolution are correlated with species richness in a large and ecologically diverse radiation of songbirds. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyčka, J.; Toszogyova, A.; Storch, D. The relationship between geographic range size and rates of species diversification. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak, K.H.; Wiens, J.J. Accelerated rates of climatic-niche evolution underlie rapid species diversification. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Peterson, A.T.; Myers, C.E.; Yang, Q.; Saupe, E.E. Ecological niche conservatism spurs diversification in response to climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, K.H.; Wiens, J.J. Climatic zonation drives latitudinal variation in speciation mechanisms. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2007, 274, 2995–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta, A.; Suh, A.; Feschotte, C. Dynamics of genome size evolution in birds and mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E1460–E1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

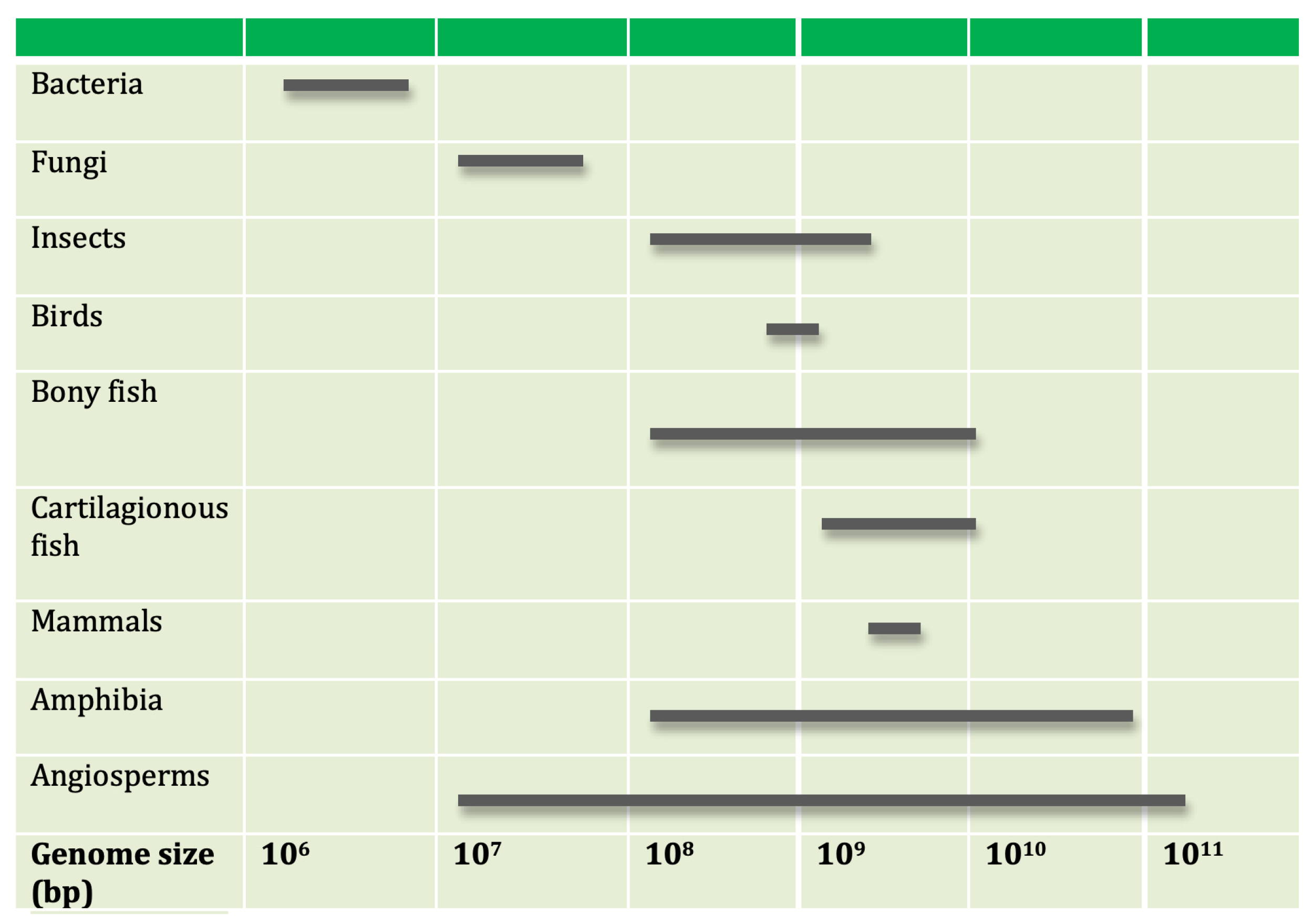

- Elliott, T.A.; Gregory, T.R. What's in a genome? The C-value enigma and the evolution of eukaryotic genome content. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decena-Segarra, L.P.; Bizjak-Mali, L.; Kladnik, A.; Sessions, S.K.; Rovito, S.M. Miniaturization, Genome Size, and Biological Size in a Diverse Clade of Salamanders. Am. Nat. 2020, 196, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.C.; Gordon, R. Differentiation trees, a junk DNA molecular clock, and the evolution of neoteny in salamanders. J. Evol. Biol. 1995, 8, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzhdin, S.V.; Mackay, T.F. The genomic rate of transposable element movement in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1995, 12, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, T.D.; de Freitas, T.R. Investigating the evolutionary dynamics of diploid number variation in Ctenomys (Ctenomyidae, Rodentia). Genet. Mol. Biol. 2023, 46, e20230180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson-Smith, M.A.; Trifonov, V. Mammalian karyotype evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, M.; Arroyo, J.M.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; Jordano, P. Founder events and subsequent genetic bottlenecks underlie karyotype evolution in the Ibero-North African endemic Carex helodes. Ann. Bot. 2023, 133, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, M. The neutral theory of molecular evolution: A review of recent evidence. Jpn. J. Genet. 1991, 66, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, A. , Usmanova, D. R., & Vitkup, D. (2025). Integrated model of the protein molecular clock across mammalian species. bioRxiv, 2025-01. doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.14. 6330. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.-S.; Chaw, S.-M. Large-Scale Comparative Analysis Reveals the Mechanisms Driving Plastomic Compaction, Reduction, and Inversions in Conifers II (Cupressophytes). Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 3740–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marais, G.; Domazet-Lošo, T.; Tautz, D.; Charlesworth, B. Correlated Evolution of Synonymous and Nonsynonymous Sites in Drosophila. J. Mol. Evol. 2004, 59, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckoff, G.J.; Malcom, C.M.; Vallender, E.J.; Lahn, B.T. A highly unexpected strong correlation between fixation probability of nonsynonymous mutations and mutation rate. Trends Genet. 2005, 21, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoletzki, N.; Eyre-Walker, A. The Positive Correlation between dN/dS and dS in Mammals Is Due to Runs of Adjacent Substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 28, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisinger, M.M.; Kuehl, J.V.; Boore, J.L.; Jansen, R.K. Genome-wide analyses of Geraniaceae plastid DNA reveal unprecedented patterns of increased nucleotide substitutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 18424–18429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garamszegi, L.Z.; de Groot, N.G.; E Bontrop, R. Correlated evolution of nucleotide substitution rates and allelic variation in Mhc-DRB lineages of primates. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 73–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeron, J.M.; Kreitman, M. The Correlation Between Synonymous and Nonsynonymous Substitutions in Drosophila: Mutation, Selection or Relaxed Constraints? Genetics 1998, 150, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, J.H.; Li, H.; Langley, C.H. Functional Bias and Spatial Organization of Genes in Mutational Hot and Cold Regions in the Human Genome. PLOS Biol. 2004, 2, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, M.; Watson, C.; Edwards, R.J.; Mattick, J.S.; Crandall, K. The Evolution of Ultraconserved Elements in Vertebrates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makałowski, W.; Boguski, M.S. Evolutionary parameters of the transcribed mammalian genome: An analysis of 2,820 orthologous rodent and human sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 9407–9412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkinson, A.; Eyre-Walker, A. Variation in the mutation rate across mammalian genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agier, N.; Fischer, G. The Mutational Profile of the Yeast Genome Is Shaped by Replication. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 29, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-L.; Rappailles, A.; Duquenne, L.; Huvet, M.; Guilbaud, G.; Farinelli, L.; Audit, B.; D'AUbenton-Carafa, Y.; Arneodo, A.; Hyrien, O.; et al. Impact of replication timing on non-CpG and CpG substitution rates in mammalian genomes. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.C.; Pink, C.J.; Hurst, L.D. Late-Replicating Domains Have Higher Divergence and Diversity in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 29, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staunton, P.M.; Peters, A.J.; Seoighe, C.; Britt, A. Somatic mutations inferred from RNA-seq data highlight the contribution of replication timing to mutation rate variation in a model plant. Genetics 2023, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A.; Adzhubei, I.; Thurman, R.E.; Kryukov, G.V.; Mirkin, S.M.; Sunyaev, S.R. Human mutation rate associated with DNA replication timing. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaboriaud, J.; Wu, P.-Y.J. Insights into the Link between the Organization of DNA Replication and the Mutational Landscape. Genes 2019, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhind, N. DNA replication timing: Biochemical mechanisms and biological significance. BioEssays 2022, 44, e2200097–e2200097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boos, D.; Ferreira, P. Origin Firing Regulations to Control Genome Replication Timing. Genes 2019, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechhoefer, J.; Rhind, N. Replication timing and its emergence from stochastic processes. Trends Genet. 2012, 28, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.Q.; Blow, J.J. Chk1 inhibits replication factory activation but allows dormant origin firing in existing factories. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldar, A.; Marsolier-Kergoat, M.-C.; Hyrien, O.; Bähler, J. Universal Temporal Profile of Replication Origin Activation in Eukaryotes. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.C.; Rhind, N.; Bechhoefer, J. Modeling genome-wide replication kinetics reveals a mechanism for regulation of replication timing. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010, 6, 404–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Bacal, J.; Desmarais, D.; Padioleau, I.; Tsaponina, O.; Chabes, A.; Pantesco, V.; Dubois, E.; Parrinello, H.; Skrzypczak, M.; et al. The Histone Deacetylases Sir2 and Rpd3 Act on Ribosomal DNA to Control the Replication Program in Budding Yeast. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, L.; Das, S.; Nordman, J.T. Rif1-Dependent Control of Replication Timing. Genes 2022, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, P.; Perez, C.; Crisp, A.; van Eijk, P.; Reed, S.H.; Guilbaud, G.; Sale, J.E. DNA replication initiation shapes the mutational landscape and expression of the human genome. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eadd3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, D.A.; Bloom, J.D.; Adami, C.; Wilke, C.O.; Arnold, F.H. Why highly expressed proteins evolve slowly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 14338–14343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhind, N. DNA replication timing: random thoughts about origin firing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, D.S.; Gilbert, D.M. The Spatial Position and Replication Timing of Chromosomal Domains Are Both Established in Early G1 Phase. Mol. Cell 1999, 4, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, J.; Gilbert, D.M. Complex correlations: replication timing and mutational landscapes during cancer and genome evolution. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2014, 25, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhind, N.; Gilbert, D.M. DNA Replication Timing. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a010132–a010132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M. , Wang, Z., Su, Z., Shibata, E., Shibata, Y., Dutta, A., & Zang, C. (2024). Integrative analysis of DNA replication origins and ORC-/MCM-binding sites in human cells reveals a lack of overlap. Elife, 12, RP89548. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.M. Replication timing and transcriptional control: Beyond cause and effect. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002, 14, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira-Mendes, J.; Díaz-Uriarte, R.; Apedaile, A.; Huntley, D.; Brockdorff, N.; Gómez, M.; Bickmore, W.A. Transcription Initiation Activity Sets Replication Origin Efficiency in Mammalian Cells. PLOS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.A.; Nieduszynski, C.A. DNA replication timing influences gene expression level. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.P.; Borrman, T.; Liu, V.W.; Yang, S.C.-H.; Bechhoefer, J.; Rhind, N. Replication timing is regulated by the number of MCMs loaded at origins. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1886–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ai, C.; Gan, T.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Lu, R.; Gao, N.; Li, Q.; Ji, X.; et al. Transcription shapes DNA replication initiation to preserve genome integrity. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.M.; Johnson, M.C.; Fiedler, L.; Zegerman, P. Global early replication disrupts gene expression and chromatin conformation in a single cell cycle. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.J.; Putta, S.; Zhu, W.; Pao, G.M.; Verma, I.M.; Hunter, T.; Bryant, S.V.; Gardiner, D.M.; Harkins, T.T.; Voss, S.R. Genic regions of a large salamander genome contain long introns and novel genes. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 19–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farlow, A.; Meduri, E.; Schlötterer, C. DNA double-strand break repair and the evolution of intron density. Trends Genet. 2011, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburne, I.A.; Silver, P.A. Intron Delays and Transcriptional Timing during Development. Dev. Cell 2008, 14, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyn, P.; Kalinka, A.T.; Tomancak, P.; Neugebauer, K.M. Introns and gene expression: Cellular constraints, transcriptional regulation, and evolutionary consequences. BioEssays 2014, 37, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffenstein, R.; Lewis, K.N.; Gibney, P.A.; Narayan, V.; Grimes, K.M.; Smith, M.; Lin, T.D.; Brown-Borg, H.M. Probing Pedomorphy and Prolonged Lifespan in Naked Mole-Rats and Dwarf Mice. Physiology 2020, 35, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groef, B.; Grommen, S.V.; Darras, V.M. Forever young: Endocrinology of paedomorphosis in the Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2018, 266, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, R.; van Schaik, B.D.; van Batenburg, M.F.; Roos, M.; Monajemi, R.; Caron, H.; Bussemaker, H.J.; van Kampen, A.H. The Human Transcriptome Map Reveals Extremes in Gene Density, Intron Length, GC Content, and Repeat Pattern for Domains of Highly and Weakly Expressed Genes. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 1998–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Davis, C.I.; Mekhedov, S.L.; Hartl, D.L.; Koonin, E.V.; Kondrashov, F.A. Selection for short introns in highly expressed genes. Nat. Genet. 2002, 31, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, W.R.; Wörheide, G. Similar Ratios of Introns to Intergenic Sequence across Animal Genomes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 1582–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddrill, P.R.; Charlesworth, B.; Halligan, D.L.; Andolfatto, P. Patterns of intron sequence evolution in Drosophila are dependent upon length and GC content. Genome Biol. 2005, 6, R67–R67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agier, N.; Delmas, S.; Zhang, Q.; Fleiss, A.; Jaszczyszyn, Y.; van Dijk, E.; Thermes, C.; Weigt, M.; Cosentino-Lagomarsino, M.; Fischer, G. The evolution of the temporal program of genome replication. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, A.; Karschau, J. Mathematical model for the distribution of DNA replication origins. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 110, 034408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, A.N.; Dallmann, A.; Ding, Q.; Hubisz, M.J.; Caballero, M.; Koren, A. The evolution of the human DNA replication timing program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.-R.; Liao, B.-Y.; Zhuang, S.-M.; Zhang, J. Protein misinteraction avoidance causes highly expressed proteins to evolve slowly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, E831–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, D.A.; Wilke, C.O. Mistranslation-Induced Protein Misfolding as a Dominant Constraint on Coding-Sequence Evolution. Cell 2008, 134, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syljuåsen, R.G.; Sørensen, C.S.; Hansen, L.T.; Fugger, K.; Lundin, C.; Johansson, F.; Helleday, T.; Sehested, M.; Lukas, J.; Bartek, J. Inhibition of Human Chk1 Causes Increased Initiation of DNA Replication, Phosphorylation of ATR Targets, and DNA Breakage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 3553–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann, E.; Woodcock, M.; Helleday, T. Chk1 promotes replication fork progression by controlling replication initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 16090–16095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maya-Mendoza, A.; Petermann, E.; Gillespie, D.A.F.; Caldecott, K.W.; A Jackson, D. Chk1 regulates the density of active replication origins during the vertebrate S phase. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 2719–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.Q.; Jackson, D.A.; Blow, J.J. Dormant origins licensed by excess Mcm2–7 are required for human cells to survive replicative stress. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 3331–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alver, R.C.; Chadha, G.S.; Blow, J.J. The contribution of dormant origins to genome stability: From cell biology to human genetics. DNA Repair 2014, 19, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, J.; Tsaponina, O.; Crabbé, L.; Keszthelyi, A.; Pantesco, V.; Chabes, A.; Lengronne, A.; Pasero, P. dNTP pools determine fork progression and origin usage under replication stress. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hand, R. Regulation of DNA replication on subchromosomal units of mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 1975, 64, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, C.; Saccà, B.; Herrick, J.; Lalou, C.; Pommier, Y.; Bensimon, A.; Matera, A.G. Replication Fork Velocities at Adjacent Replication Origins Are Coordinately Modified during DNA Replication in Human Cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 3059–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.; Hyrien, O.; Goldar, A. Do replication forks control late origin firing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae? Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 40, 2010–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmel, L.; Rogozin, I.B.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V. Evolutionarily conserved genes preferentially accumulate introns. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, P.A.; Seoighe, C. Intron Length Coevolution across Mammalian Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 2682–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, J. Genome size evolution: towards new model systems for old questions. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2020, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Arriaza, J.R.L.; Mueller, R.L. Slow DNA Loss in the Gigantic Genomes of Salamanders. Genome Biol. Evol. 2012, 4, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheret, M.; Halazonetis, T.D. Intragenic origins due to short G1 phases underlie oncogene-induced DNA replication stress. Nature 2018, 555, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, A.; Grosso, A.R.; Elkaoutari, A.; Coleno, E.; Presle, A.; Sridhara, S.C.; Janbon, G.; Géli, V.; de Almeida, S.F.; Palancade, B. Introns Protect Eukaryotic Genomes from Transcription-Associated Genetic Instability. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 608–621.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.Q.; Han, J.; Cheng, E.-C.; Yamaguchi, S.; Shima, N.; Thomas, J.-L.; Lin, H. Embryonic Stem Cells License a High Level of Dormant Origins to Protect the Genome against Replication Stress. Stem Cell Rep. 2015, 5, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.M.; GöhLer, T.; Luciani, M.G.; Oehlmann, M.; Ge, X.; Gartner, A.; Jackson, D.A.; Blow, J.J. Excess Mcm2–7 license dormant origins of replication that can be used under conditions of replicative stress. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 173, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Shepard, D.B.; Chong, R.A.; Arriaza, J.L.; Hall, K.; Castoe, T.A.; Feschotte, C.; Pollock, D.D.; Mueller, R.L. LTR Retrotransposons Contribute to Genomic Gigantism in Plethodontid Salamanders. Genome Biol. Evol. 2011, 4, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Bozzella, M.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V. Comparison of nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination in human cells. DNA Repair 2008, 7, 1765–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastav, M.; De Haro, L.P.; Nickoloff, J.A. Regulation of DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandsma, I.; van Gent, D.C. Pathway choice in DNA double strand break repair: observations of a balancing act. Genome Integr. 2012, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Yamin, B.; Ahmed-Seghir, S.; Tomida, J.; Despras, E.; Pouvelle, C.; Yurchenko, A.; Goulas, J.; Corre, R.; Delacour, Q.; Droin, N.; et al. DNA polymerase zeta contributes to heterochromatin replication to prevent genome instability. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e104543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirouilh-Barbat, J.; Huck, S.; Bertrand, P.; Pirzio, L.; Desmaze, C.; Sabatier, L.; Lopez, B.S. Impact of the KU80 Pathway on NHEJ-Induced Genome Rearrangements in Mammalian Cells. Mol. Cell 2004, 14, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, R.; Panday, A.; Elango, R.; Willis, N.A. DNA double-strand break repair-pathway choice in somatic mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Miura, H.; Shibata, T.; Nagao, K.; Okumura, K.; Ogata, M.; Obuse, C.; Takebayashi, S.-I.; Hiratani, I. Genome-wide stability of the DNA replication program in single mammalian cells. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, T.; Callegari, A.J. Dynamics of DNA replication in a eukaryotic cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 4973–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bassetti, F.; Gherardi, M.; Lagomarsino, M.C. Cell-to-cell variability and robustness in S-phase duration from genome replication kinetics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 8190–8198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, T.; Schauer, T.; Altamirano-Pacheco, L.; Klein, K.N.; Ettinger, A.; Pal, M.; Gilbert, D.M.; Torres-Padilla, M.-E. Emergence of replication timing during early mammalian development. Nature 2023, 625, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massip, F.; Laurent, M.; Brossas, C.; Fernández-Justel, J.M.; Gómez, M.; Prioleau, M.-N.; Duret, L.; Picard, F. Evolution of replication origins in vertebrate genomes: rapid turnover despite selective constraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5114–5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryba, T.; Hiratani, I.; Lu, J.; Itoh, M.; Kulik, M.; Zhang, J.; Schulz, T.C.; Robins, A.J.; Dalton, S.; Gilbert, D.M. Evolutionarily conserved replication timing profiles predict long-range chromatin interactions and distinguish closely related cell types. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, E.; Farkash-Amar, S.; Polten, A.; Yakhini, Z.; Tanay, A.; Simon, I.; Bickmore, W.A. Comparative Analysis of DNA Replication Timing Reveals Conserved Large-Scale Chromosomal Architecture. PLOS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Goldberg, M.; Harris, K.; Corbett-Detig, R. Mutational Signatures of Replication Timing and Epigenetic Modification Persist through the Global Divergence of Mutation Spectra across the Great Ape Phylogeny. Genome Biol. Evol. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B. Evolutionary Insights into the Relationship of Frogs, Salamanders, and Caecilians and Their Adaptive Traits, with an Emphasis on Salamander Regeneration and Longevity. Animals 2023, 13, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Carlos, H.; Segovia-Ramírez, M.G.; Fujita, M.K.; Rovito, S.M. Genomic Gigantism is not Associated with Reduced Selection Efficiency in Neotropical Salamanders. J. Mol. Evol. 2024, 92, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddy, A.B.; Alvarez-Ponce, D.; Roy, S.W.; Larracuente, A. Mammals with Small Populations Do Not Exhibit Larger Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3737–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohlhenrich, E.R.; Mueller, R.L. Genetic drift and mutational hazard in the evolution of salamander genomic gigantism. Evolution 2016, 70, 2865–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessions, S.K. Evolutionary cytogenetics in salamanders. Chromosom. Res. 2008, 16, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liedtke, H.C.; Gower, D.J.; Wilkinson, M.; Gomez-Mestre, I. Macroevolutionary shift in the size of amphibian genomes and the role of life history and climate. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1792–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venditti, C.; Pagel, M. Speciation as an active force in promoting genetic evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefébure, T.; Morvan, C.; Malard, F.; François, C.; Konecny-Dupré, L.; Guéguen, L.; Weiss-Gayet, M.; Seguin-Orlando, A.; Ermini, L.; Der Sarkissian, C.; et al. Less effective selection leads to larger genomes. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 1016–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuselli, S.; Greco, S.; Biello, R.; Palmitessa, S.; Lago, M.; Meneghetti, C.; McDougall, C.; Trucchi, E.; Stabelli, O.R.; Biscotti, A.M.; et al. Relaxation of Natural Selection in the Evolution of the Giant Lungfish Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, M. Evolution of the mutation rate. Trends Genet. 2010, 26, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.K.; Frantz, A.C.; Burke, T.; Geffen, E.; Sin, S.Y.W. Both selection and drift drive the spatial pattern of adaptive genetic variation in a wild mammal. Evolution 2022, 77, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabi, M.; Filion, G.J. Heterochromatin: did H3K9 methylation evolve to tame transposons? Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.; Colmenares, S.U.; Karpen, G.H. Heterochromatin: Guardian of the Genome. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 34, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintersberger, E. Why is there late replication? Chromosoma 2000, 109, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrick, J. GENETIC VARIATION AND DNA REPLICATION TIMING, OR WHY IS THERE LATE REPLICATING DNA? Evolution 2011, 65, 3031–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, M.; Albergante, L.; Moreno, A.; Carrington, J.T.; Blow, J.J.; Newman, T.J. Inevitability and containment of replication errors for eukaryotic genome lengths spanning megabase to gigabase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E5765–E5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuny, A.; Polo, S.E. The response to DNA damage in heterochromatin domains. Chromosoma 2018, 127, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mamun, M.; Albergante, L.; Blow, J.; Newman, T. 3 tera-basepairs as a fundamental limit for robust DNA replication. Phys. Biol. 2020, 17, 046002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Carrington, J.T.; Albergante, L.; Al Mamun, M.; Haagensen, E.J.; Komseli, E.-S.; Gorgoulis, V.G.; Newman, T.J.; Blow, J.J. Unreplicated DNA remaining from unperturbed S phases passes through mitosis for resolution in daughter cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E5757–E5764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angileri, K.M.; Bagia, N.A.; Feschotte, C. Transposon control as a checkpoint for tissue regeneration. Development 2022, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuntini, A.R.; Carruthers, T.; Maurin, O.; Bailey, P.C.; Leempoel, K.; Brewer, G.E.; Epitawalage, N.; Françoso, E.; Gallego-Paramo, B.; McGinnie, C.; et al. Phylogenomics and the rise of the angiosperms. Nature 2024, 629, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowska-Zuchowska, N.; Senderowicz, M.; Trunova, D.; Kolano, B. Tracing the Evolution of the Angiosperm Genome from the Cytogenetic Point of View. Plants 2022, 11, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, I.; Vu, G.T. Genome Stability and Evolution: Attempting a Holistic View. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannattasio, M.; Branzei, D. S-phase checkpoint regulations that preserve replication and chromosome integrity upon dNTP depletion. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 2361–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voskarides, K.; Giannopoulou, N. The Role of TP53 in Adaptation and Evolution. Cells 2023, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

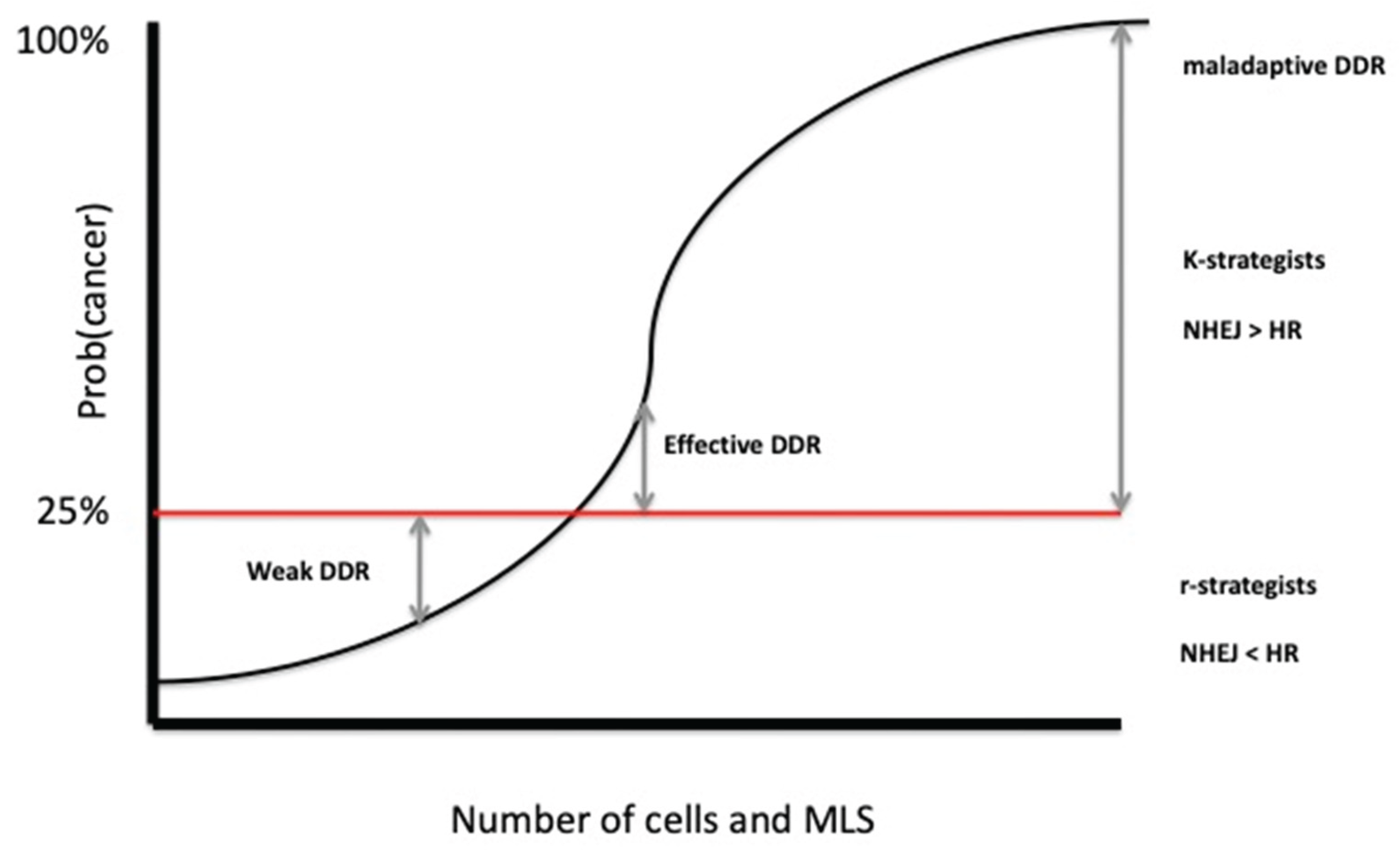

- Roche, B.; E Hochberg, M.; Caulin, A.F.; Maley, C.C.; A Gatenby, R.; Misse, D.; Thomas, F. Natural resistance to cancers: a Darwinian hypothesis to explain Peto’s paradox. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 387–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, O.; Colchero, F.; Lemaître, J.-F.; Conde, D.A.; Pavard, S.; Bieuville, M.; Urrutia, A.O.; Ujvari, B.; Boddy, A.M.; Maley, C.C.; et al. Cancer risk across mammals. Nature 2021, 601, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dart, A. Peto’s paradox put to the test. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 129–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, J. , & Lynch, V. J. (2024). Rapid evolution of genes with anti-cancer functions during the origins of large bodies and cancer resistance in elephants. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Maciak, S. Cell size, body size and Peto’s paradox. BMC Evol. Biol. 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, Z.T.; Mellon, W.; Harris, V.K.; Rupp, S.; Mallo, D.; Kapsetaki, S.E.; Wilmot, M.; Kennington, R.; Noble, K.; Baciu, C.; et al. Cancer Prevalence across Vertebrates. Cancer Discov. 2024, 15, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulak, M.; Fong, L.; Mika, K.; Chigurupati, S.; Yon, L.; Mongan, N.P.; Emes, R.D.; Lynch, V.J. TP53 copy number expansion is associated with the evolution of increased body size and an enhanced DNA damage response in elephants. eLife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.; Baker, J.; Amend, S.R.; Pienta, K.J.; Venditti, C. No evidence for Peto’s paradox in terrestrial vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2025, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Firsanov, D.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, L.; Tombline, G.; Tan, R.; Simon, M.; Henderson, S.; Steffan, J.; et al. SIRT6 Is Responsible for More Efficient DNA Double-Strand Break Repair in Long-Lived Species. Cell 2019, 177, 622–638.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov, A.A.; Petruseva, I.O.; Lavrik, O.I. Activity of DNA Repair Systems in the Cells of Long-Lived Rodents and Bats. Biochem. (Moscow) 2024, 89, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagan, A.; Baez-Ortega, A.; Brzozowska, N.; Abascal, F.; Coorens, T.H.H.; Sanders, M.A.; Lawson, A.R.J.; Harvey, L.M.R.; Bhosle, S.; Jones, D.; et al. Somatic mutation rates scale with lifespan across mammals. Nature 2022, 604, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, F.; Baer, C.; Wolf, J. Allometric scaling of somatic mutation and epimutation rates in trees. Evolution 2024, 79, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.P.; Singh, P. Linking DNA damage and senescence to gestation period and lifespan in placental mammals. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1480695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damas, J.; Corbo, M.; Kim, J.; Turner-Maier, J.; Farré, M.; Larkin, D.M.; Ryder, O.A.; Steiner, C.; Houck, M.L.; Hall, S.; et al. Evolution of the ancestral mammalian karyotype and syntenic regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2209139119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, A.; Escudero, M. Karyotypic diversity: a neglected trait to explain angiosperm diversification? Evolution 2023, 77, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, S. H. , Otto, S. S. ( 2021). Broad variation in rates of polyploidy and dysploidy across flowering plants is correlated with lineage diversification. bioRxiv, 2021–03. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Shang, H.; Shu, H.; Liu, D.; Yang, H.; Jia, K.; Wang, X.; Sun, W.; Zhao, W.; et al. Convergent Patterns of Karyotype Evolution Underlying Karyotype Uniformity in Conifers. Adv. Sci. 2024, 12, e2411098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.A.; Maliet, O.; Aristide, L.; Nogués-Bravo, D.; Upham, N.; Jetz, W.; Morlon, H. Negative global-scale association between genetic diversity and speciation rates in mammals. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, L.A.; Besenbacher, S.; Zheng, J.; Li, P.; Bertelsen, M.F.; Quintard, B.; Hoffman, J.I.; Li, Z.; Leger, J.S.; Shao, C.; et al. Evolution of the germline mutation rate across vertebrates. Nature 2023, 615, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futuyma, D.J. EVOLUTIONARY CONSTRAINT AND ECOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES. Evolution 2010, 64, 1865–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, B.; Pothof, J.; Vijg, J.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J. The central role of DNA damage in the ageing process. Nature 2021, 592, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahm, A. , Cherkasov, A. ( 2024). The Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) genome provides insights into extreme longevity. bioRxiv, 2024–09. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. , Nishiwaki, K., Mizobata, H., Asakawa, S., Yoshitake, K., Watanabe, Y. Y.,... & Kinoshita, S. (2025). The Greenland shark genome: insights into deep-sea ecology and lifespan extremes. bioRxiv, 2025-02. [CrossRef]

- Kilili, H.; Padilla-Morales, B.; Castillo-Morales, A.; Monzón-Sandoval, J.; Díaz-Barba, K.; Cornejo-Paramo, P.; Vincze, O.; Giraudeau, M.; Bush, S.J.; Li, Z.; et al. Maximum lifespan and brain size in mammals are associated with gene family size expansion related to immune system functions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland, J.; Henao-Diaz, L.F.; Doebeli, M.; Germain, R.; Harmon, L.J.; Knowles, L.L.; Liow, L.H.; Mank, J.E.; Machac, A.; Otto, S.P.; et al. Conceptual and empirical bridges between micro- and macroevolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertucci-Richter, E.M.; Parrott, B.B. The rate of epigenetic drift scales with maximum lifespan across mammals. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Liang, G.; Molloy, P.L.; Jones, P.A. DNA methylation enables transposable element-driven genome expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 19359–19366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adj R2 | P | |

| MLS vs Body Mass (+) | 0.73 | 2 x 10-16 |

| MLS vs C-value | 0,007 | 0,5 |

| SR vs Body Mass (-) | 0.56 | 0.01 |

| MLS vs Synteny (+) | 0.48 | 0.03 |

| Synteny vs SR | 0.18 | 0.1 |

| MLS vs SR (-) | 0.59 | 0.016 |

| rKD Macro vs SR (+) | 0.42 | 3 x 10-10 |

| rKD Micro vs SR | 0.07 | 0.06 |

|

Table 2 Species |

Gestation Time | Embryo Cell Cycle Duration |

| Drosophila | (24 hours) | 8–10 minutes |

| Frog | (6–21 days) | 0.5 hours |

| Salamanders | (14)–728 days | 4–8 hours |

| Mouse | 19–21 days | 2–4 hours |

| Rabbit | 30–32 days | 5–8 hours |

| Dog | 58–69 days | 8–12 hours |

| Naked mole rat | 66 -77 days | NA |

| Beaver | 105–107 days | NA |

| Human | 280 days | 12–24 hours |

| Cow | 279-292days | 32 hours |

| Elephant | 660 days | 18–36 hours |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).