1. Introduction

More than 30 economically important legume species are cultivated in tropical regions, contributing to global food and nutritional security (Abate et al., 2012). In South Asia, legumes serve as important dietary and medicinal staples. Whereas in regions such as Australia and the USA, they are often grown as a fodder crop (Jensen, 2006, as cited by Nair, 2023). Effective management of biotic stresses is essential, legumes are susceptible to biotic stresses causing yield losses of up to 70% during epidemics (Sharma et al., 2011).

Legume crops are vulnerable to a wide range of pathogens including fungi, bacteria, viruses and nematodes, which severely impact crop yield and grain quality. Economically important diseases include web blight (Rhizoctonia solani Kühn), powdery mildew (Erysiphe polygoni), Cercospora leaf spot (Cercospora canescens), anthracnose (Colletotrichum capsici), Mungbean Yellow Mosaic Virus and Urdbean Leaf Crinkle Virus (Kumar et al., 2014; Pandey et al., 2009; Dubey and Singh, 2010; Chatak and Banyal, 2020; Negi and Vishunavat, 2006). Disease severity and prevalence vary significantly among agroecological zones.

Among these, web blight caused by Rhizoctonia solani Kühn (teleomorph: Thanatephorus cucumeris [Frank] Donk) is particularly destructive in pulse crops grown in the Indo-Gangetic plains and Himalayan foothills. Yield losses due to R. solani have been reported between 33-40% (Singh, 2006; Gupta and Singh, 2002) under field conditions relative to the healthy check. Disease incidence has been reported from all over the subcontinent (Saksena and Dwivedi, 1973). Its persistence in the soil through long surviving sclerotia and wide host range has made it a recurring challenge in legume production systems (Saksena and Dwivedi, 1973; Zhang et al., 2021).

R. solani is a saprotrophic and necrotrophic soil-borne plant pathogenic fungus, with a host range exceeding 200 plant species including legumes, cereals, oilseeds and ornamentals (Moliszewska et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2021; Parmeter, 1970). Initial infection manifests as water-soaked lesions near the petiole, progressing to leaf blight and characteristic web blight with dense mycelial mats and prolific sclerotia formation (Bara, 2007). The pathogen's ecological resilience is underscored by studies reporting up to 50% germination of sclerotia after two years in the soil at 5 cm depth (Ritchie et al., 2013; Wigg et al., 2023).

Despite extensive research, resistance breeding in legumes remains constrained by the high genetic and pathogenic variability of R. solani, as well as the underutilization of available resistance sources. Most breeding programs still rely on classical phenotypic screening often disconnected with omics-informed understanding of pathogen diversity. Resistance genes identified thus far are frequently limited in effectiveness due to issues like linkage drag or AG-specificity underscoring the need for a more integrated approach.

This review consolidates current knowledge on the morphological and molecular variability of R. solani and proposes a conceptual system biology-based roadmap for developing durable resistance in legumes. By integrating functional omics data with phenotypic traits, this framework aims to enhance the development of resilient, environmentally sustainable cultivars. It is designed to aid breeders, pathologists and crop protection researchers in comprehending the complexity of R. solani-legume interactions.

2. Pathogen Biology

Rhizoctonia solani is a filamentous soil-borne fungus that lacks both sexual and asexual spores in its anamorphic stage (Gracia et al., 2006). A characteristic feature of this pathogen is its right-angled hyphal branching with a constriction and a septum at the point of branching, which serves as a key diagnostic trait under light microscopy (Lal and Khandari, 2009).

R. solani is a species complex consisting of genetically distinct yet morphologically similar strains, most of which exhibit pathogenicity toward a wide range of plants. Based on hyphal nuclear content, isolates are grouped into: binucleate Rhizoctonia (BNR) and multinucleate Rhizoctonia types (Moliszewska et al., 2023).

The species complex is classified into 13 primary anastomosis groups (AGs), from AG-1 to AG-13 based on hyphal fusion compatibility. One formerly distinct group, AG-B1 was reclassified under AG-2-IIB following molecular characterization (Dubey et al., 2014; Spedaletti et al., 2016; Basbagci et al., 2019). Within binucleate isolates, an additional 22 subgroups have been reported (Yang et al., 2015). Each AG exhibits a unique virulence profile, host specificity and ecological adaptability contributing to the pathogen's prevalence and complexity.

Molecular tools, especially sequencing of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS 2 regions of rDNA, are regarded as standard protocols for AG identification and phylogenetic resolution (Sharon et al., 2007). While classical anastomosis assays remain foundational, they have limitations, whereas some isolates fail to anastomose even within the same AG, while occasionally cross-AGs can produce false positives (Sharon et al., 2008). As a result, phylogenetic analysis tools like MEGA (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis), utilizing maximum likelihood algorithms, are widely used for accurate AG classification (Kumar et al., 2018).

The extensive genetic variability and adaptive virulence across AGs make R. solani a persistent threat to global agriculture. Recent reports confirm novel hosts and disease syndrome, where R. solani has been associated with Web Blight of mint in Israel (Nitzan et al., 2012), Rhizoctonia blight of Chinese Cabbage in India (Bahadur et al., 2024) and mung bean leaf rot in China (Wang, 2025). Cross-pathogenicity among AGs further complicates resistance deployment. For instance, AG 2-3 causes root and collar rot of chickpeas in Tunisia (Youssef et al., 2010), AG 2-2 III B induced sheath blight of rice in China (Shen et al., 2024) and AG 11 has been associated with lily blight in Japan (Misawa et al., 2017). The high genetic and pathogenic variability within R. solani undermines the stability of vertical resistance in pulse crops. Cross-infectivity and evolution under selection pressure often led to the breakdown of host resistance in field conditions. Although AG classification remains essential for epidemiology and variability studies, it does not always correlate with the virulence profiles or effector repositories, thus limiting its predictive value in resistance breeding.

3. Phenotypic and Pathogenic Diversity of Rhizoctonia solani in Legumes

Accurate identification of phenotypic and pathogenic variability is essential for rapid screening of R. solani isolates to mitigate disease outbreaks in legume crops. The diversity among R. solani AGs is evident in their distinct morphological, cultural and pathogenic characteristics across leguminous hosts.

Morphological and Cultural Traits

The morphological and cultural variability of R. solani is typically assessed on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium and encompasses parameters such as colony colour, texture, margins, zonation, pigmentation, growth rate and sclerotial characteristics. Isolates collected from various legume-growing agro-climatic zones exhibit significant variation in colony morphology typically progressing from initial white transitioning to light brown and later dark brown with age (Chandel, 2022). Under laboratory conditions, certain isolates from legumes such as black gram have been observed to produce 59.4% more sclerotia compared to those from other legumes (Neelam, 2013) suggesting inherent variability in reproductive structures.

The growth rate in R. solani is positively correlated with pathogenicity, wherein fast-growing isolates with dense prolific sclerotia production tend to be more virulent. These traits make them particularly valuable for disease resistance screening protocols.

Among highly aggressive R. solani isolates, three distinct hyphal morphotypes have been described, each regulated by specific genetic pathways:

Runner hyphae – long, straight and creeping structures regulated by effector secretion systems (Kaushik et al., 2022).

Lobate hyphae – short and swollen branches with appressoria and penetration pegs; primarily regulated by cell wall-degrading enzymes (CWDEs) (Li et al., 2022).

Monilioid hyphae – aggregated forms that develop into sclerotia, governed by trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase (Zhao et al., 2021).

These insights into hyphal differentiation pathways offer genetic targets for molecular tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 and RNA interference (RNAi). Functional validation through gene knockout and host-induced gene silencing (HIGS) approaches may further elucidate their roles in pathogenesis.

Thermal Adaptability

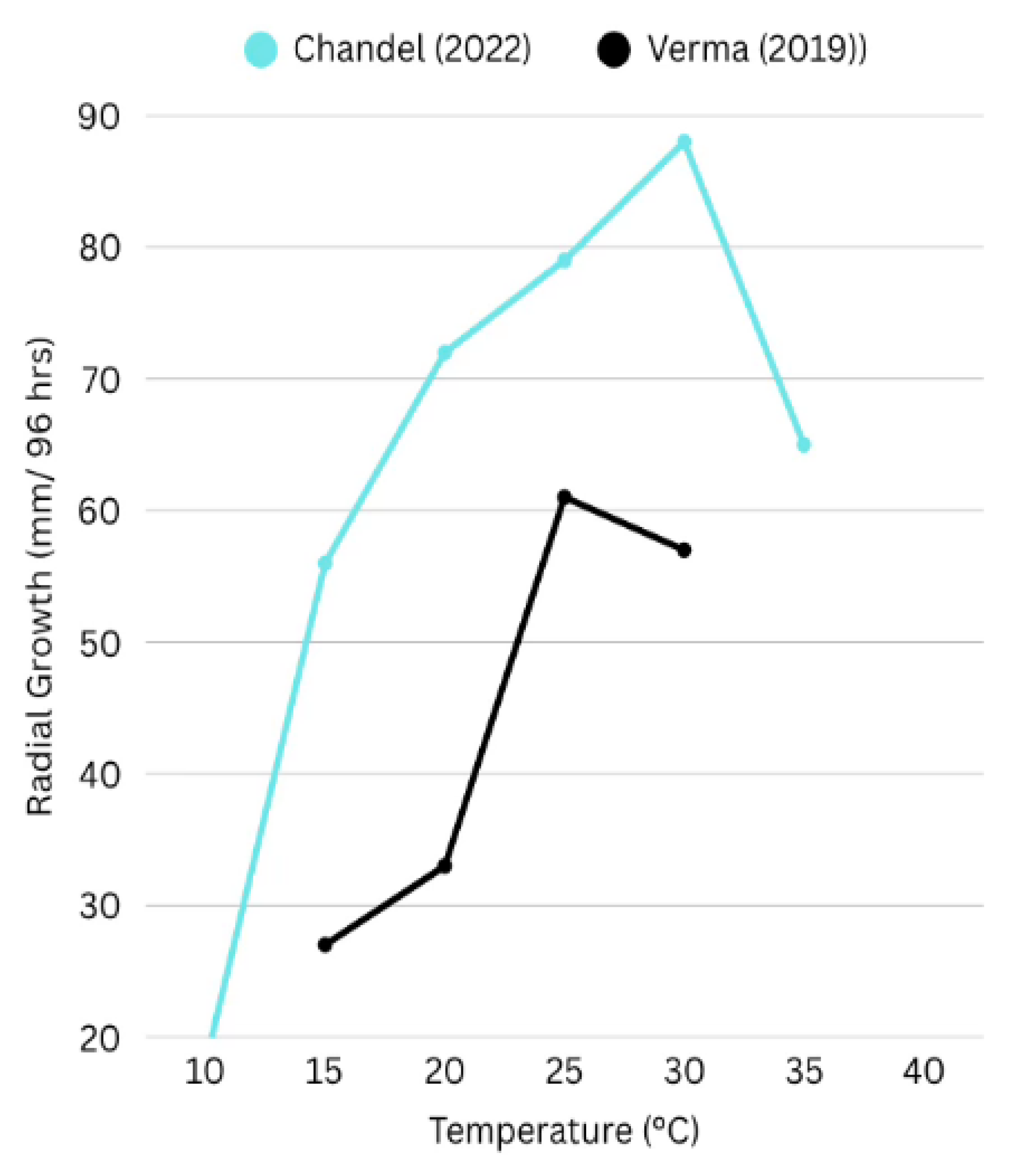

R. solani exhibits a wide thermal tolerance, though optimal growth parameters vary among isolates and AGs. In legume-associated isolates, optimal radial growth typically occurs between 25°C and 30°C. For instance, isolates from pulse-growing regions demonstrated peak mycelial expansion at 25°C and maximum sclerotia formation at 30°C (Verma, 2019) (Chandel, 2022). Such thermal response profiles, though variable, provide valuable epidemiological cues.

Integration of these thermal growth patterns with regional agro-climatic datasets enables the development of tailored disease forecasting models and cultivars screening strategies across diverse legume production zones.

Figure 1.

Effect of temperature on radial growth of Rhizoctonia solani isolates, based on data from Chandel (2022) and Verma (2019). The graph illustrates differential growth responses to temperature across 96 hours of incubation. Chandel reported optimal growth at 30°C with significant reduction at 35°C, while Verma observed peak growth at 25°C, highlighting environmental influence on isolate-specific phenotypic traits.

Figure 1.

Effect of temperature on radial growth of Rhizoctonia solani isolates, based on data from Chandel (2022) and Verma (2019). The graph illustrates differential growth responses to temperature across 96 hours of incubation. Chandel reported optimal growth at 30°C with significant reduction at 35°C, while Verma observed peak growth at 25°C, highlighting environmental influence on isolate-specific phenotypic traits.

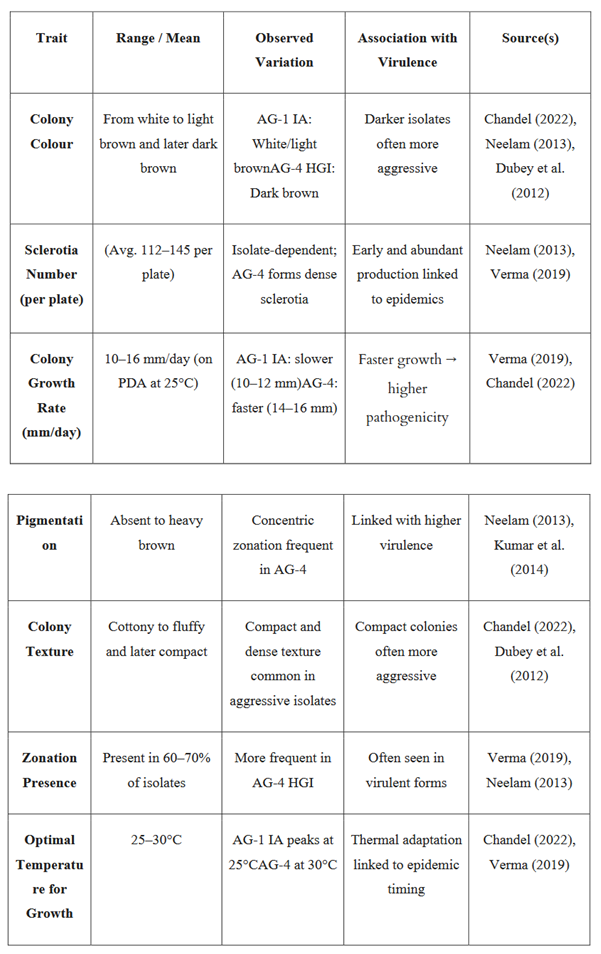

Observed Phenotypic Correlates of Virulence

Pigmentation and concentric zonation → frequently associated with highly virulent isolates.

Compact and fluffy colony texture → often correlates with increased pathogenic potential.

Phenotypic and pathogenic variability analyses offer practical, cost-effective, and rapid tools for selecting representative and aggressive R. solani isolates in legume pathology studies. Observable traits such as colony morphology, pigmentation and sclerotia density serve as preliminary indicators of potential virulence and can be used to prioritize isolates for detailed virulence testing, sequencing and surveillance during potential epidemic conditions.

Table 1.

Summary of morphological and cultural characteristics of Rhizoctonia solani isolates from legume crops and their association with pathogenicity. This table includes data on colony appearance, growth rate, pigmentation, sclerotia production, and thermal response across major AGs (particularly AG-1 IA and AG-4 HGI), facilitating the identification of high-risk isolates relevant for resistance breeding and disease forecasting in legumes.

Table 1.

Summary of morphological and cultural characteristics of Rhizoctonia solani isolates from legume crops and their association with pathogenicity. This table includes data on colony appearance, growth rate, pigmentation, sclerotia production, and thermal response across major AGs (particularly AG-1 IA and AG-4 HGI), facilitating the identification of high-risk isolates relevant for resistance breeding and disease forecasting in legumes.

4. Molecular Variability and Anastomosis Groups in Rhizoctonia solani

R. solani is a genetically diverse, multinucleate soil-borne pathogen exhibiting extensive host range adaptability across multiple legume crops. Molecular characterization plays a pivotal role in elucidating the genetic variability of the R. solani population and in understanding the epidemiological dynamics that underpin disease outbreaks in legumes. Techniques such as ITS-rDNA sequencing, ISSR profiling and transcriptome analysis have revealed substantial variation both within and between AGs, this variation significantly influences pathogenicity, host preference and effectiveness of disease management strategies.

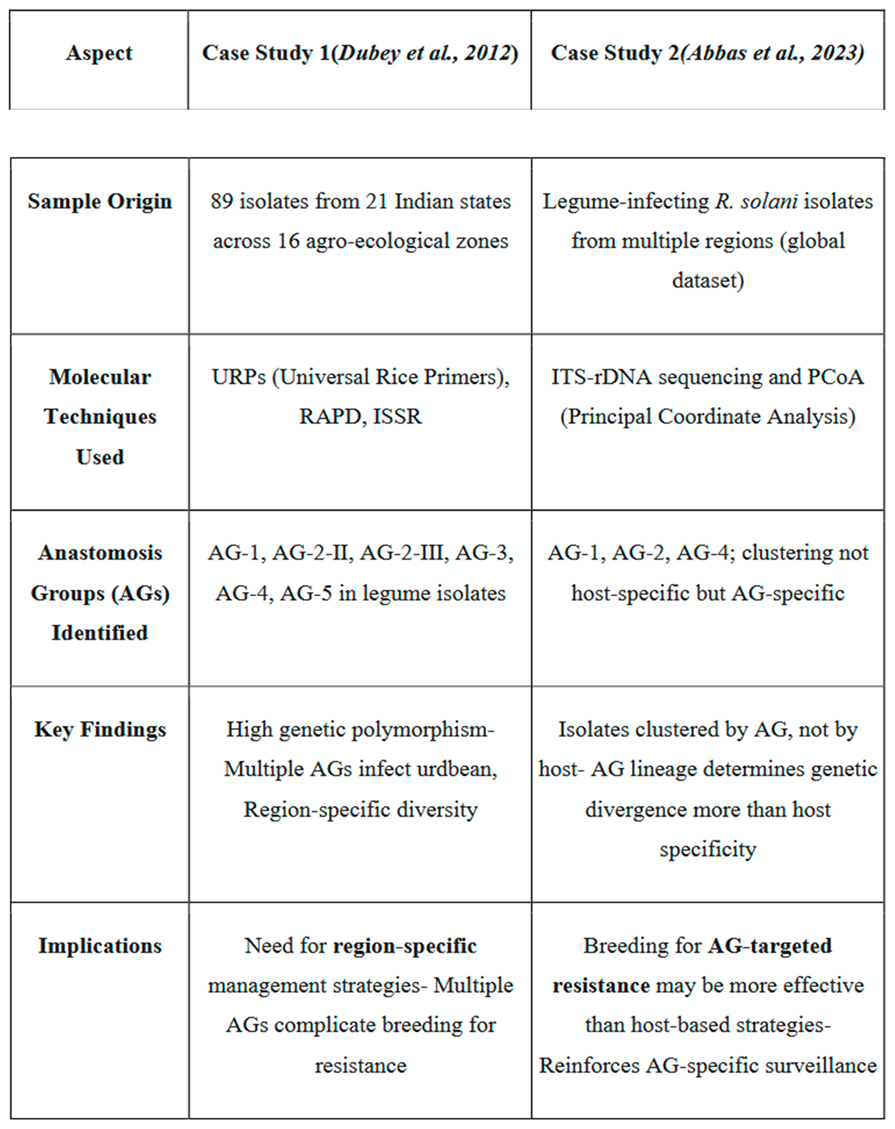

Case Study 1: Dubey et al., 2012

A comprehensive molecular investigation revealed that R. solani isolates infecting legumes can be associated with multiple Ags, including AG-1, AG-2-2, AG-2-3, AG-3, AG-4 and AG-5. For instance, isolate RPBU5 was classified under AG-4 based on ITS-rDNA sequence analysis, while other isolates (e.g., RPBU7, RUKU4, RUPU23, RUPU18 and RUPU50) were associated with Ags 2-II, 2-III and 3. This study underscores the presence of diverse Ags within single crop systems, highlighting the challenge in breeding for AG specific resistance.

Further, ISSR marker analysis confirmed the presence of AG-1-IA in legumes infecting isolates from northern India (Neelam, 2013). The detection of multiple Ags within the same host population indicates a complex pathosystem where resistance based on a single gene or QTL may be insufficient. Therefore, gene pyramiding strategies, stacking multiple resistance QTLs effective against different Ags are essential to develop a broad spectrum and durable resistance in legume crops.

Case Study 2: Abbas et al., 2023

In a recent study, molecular classification using ITS sequences demonstrated that R. solani isolates infecting various legumes clustered according to AG lineage (e.g., AG-1, Ag-2, AG-4) rather than by host species. This finding suggests that host specificity may not be the primary driver of genetic divergence in R. solani. Principal coordinate analysis (PcoA) further supported AG-wise clustering, implying that pathogenic specialization is more closely tied to AG identity than to host adaptation.

This insight has crucial implications for resistance breeding. Relying completely on host-isolate interaction studies without considering AG diversity may result in inadequate resistance coverage and failure to mitigate cross-pathogenicity between legume species.

Table 2.

Comparative summary of two molecular studies on Rhizoctonia solani infecting legumes, highlighting their methodologies, AG diversity, and implications for disease management. Adapted from Dubey et al. (2012) and Abbas et al. (2023).

Table 2.

Comparative summary of two molecular studies on Rhizoctonia solani infecting legumes, highlighting their methodologies, AG diversity, and implications for disease management. Adapted from Dubey et al. (2012) and Abbas et al. (2023).

ITS Based Phylogenetic and AG Differentiation

The Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of rDNA is the most widely adopted molecular marker for the classification of R. solani. ITS sequencing consistently distinguishes among major anastomosis groups (AG-1 to AG-13) and their subgroups (e.g., AG-1-IA, AG-2-IIWB), providing reliable phylogenetic resolution across diverse isolates. ITS based phylogenetic trees show strong concordance with classical AG classification scheme, reinforcing the genetic basis of anastomosis grouping (Sharon et al., 2008).

Beyond taxonomical utility, ITS sequencing has become a cornerstone of functional plant pathology. It facilitates not only the precise identification of R. solani isolates but also the selection of genetically diverse, representative strains for use in resistance screening programs. Such informed selection is particularly valuable for evaluating advanced breeding lines against multiple AGs, thereby supporting the development of broad spectrum and durable resistance. Moreover, regional mapping of AG distribution through ITS typing contributes significantly to epidemiological surveillance, enabling the prediction of potential outbreaks and guiding targeted management strategies in legume production systems.

5. Omics-Based Insights into Rhizoctonia solani–Legume Interactions

The expanding host range, high genetic plasticity and virulence diversity of R. solani have necessitated a shift from traditional pathogen characterization toward integrated, multiple omics enabled approach. While significant progress has been made in cereal and model legume systems such as rice (Oryzya sativa), soybean (Glycine max) and common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), most legume crops remain under-investigated at the functional genomic level. This section synthesizes the current state of multi-omics investigations in R. solani, outlining how these approaches can inform durable resistance breeding in legumes. While findings from non-leguminous systems provide a provisional framework, their direct applicability to diverse legume hosts requires validation through crop-specific studies.

5.1. Genomic Characterization of Rhizoctonia solani

Comparative genomic studies of R. solani isolates from AG1-IA, AG2-2IIIB and AG 8 reveals substantial variations in genome size (ranging from ~37 Mb to 56 Mb), gene content (9,324- 11,900 genes) and the proportion of repetitive elements (Zheng et al., 2013; Hane et al., 2014; Wibberg et al., 2016). A high proportion of isolate-specific genes particularly those encoding carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), laccase and pectinase illustrates the genomic plasticity that underpins the pathogen's ability to infect a broad host range.

The extent of the CAZyme repertoire is directly linked to the pathogen's ability for host cell wall degradation, which is particularly relevant for legumes due to their pectin-rich cell wall composition. Genomic evidence also suggests AG-specific variation in enzymatic profiles, potentially driving host adaptation and virulence specialization. However, the genome of R. solani isolates infecting legume crops has not been extensively sequenced or annotated, leaving critical knowledge gaps regarding effector-host compatibility and the genetic basis of pathogenicity. Legume-specific genomic resources are essential for the rational design of resistance strategies tailored to AG diversity.

5.2. Transcriptomic Analyses in Legumes

Transcriptomic profiling reveals significant intra-AG variation in gene expression among R. solani subgroups (AG-1 IA, IB, IC) particularly in pathways related to effector secretion, reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification and toxin biosynthesis (Yamamoto et al., 2019). Functional enrichment of resistant hosts highlights the upregulation of genes involved in peroxisomal metabolism, acetaldehyde detoxification and secondary signalling cascades, suggesting that host defence priming relies heavily on stress response modulation (Xia et al., 2017).

Although these insights have largely emerged from rice and soybean systems, limited transcriptomic studies in legumes such as mungbean have reported the induction of key defence-related genes, including PR10, catalase and calmodulin in response to bioagent application (Dubey et al., 2018). Comprehensive transcriptomic datasets for other legume crops, particularly under AG-1 and AG-4 infection scenarios, remain lacking. This hinders the identification of legume-specific defence genes and regulatory networks essential for AG-informed resistance breeding.

5.3. Proteomics of the Fungal Secretome

Proteomics analyses have revealed that the R. solani secretome is enriched with cell wall degrading enzymes including CAZymes, carbohydrate-binding molecules (CBMs), pectate lyases (PLs) and cutinases which enable rapid colonization through rapid cell wall degradation. In rice, over 30 pectin-degrading enzymes were detected within 72 hours post-infection, demonstrating the rapid temporal development of virulence factors (Anderson et al., 2016). Additionally, manipulation of host ROS signalling through suppression of peroxidase enzymes (e.g., via OsERF65) has been identified as a key virulence mechanism (Xie et al., 2023). Secretome composition differs significantly across AGs and may serve as a molecular signature of aggressiveness. Given the biochemical complexity of legume cell walls, proteomic comparison between legume-infecting and non-infecting AGs can help identify core effectors that are crucial for broad host infectivity. Such data can inform the development of protein-based markers for early detection and aggressiveness profiling in legume pathosystems.

5.4. Metabolomic Responses in Infected Legumes

Metabolomic profiling of Phaseolus vulgaris during R. solani infection has revealed the accumulation of a diverse array of secondary metabolites including flavonoids, terpenoids, phenols and amino acid derivatives involved in redox balance, structural reinforcement and signalling pathways (Mayo-Prieto et al., 2019). Notably, coumarins and phenylalanine derived from the phenylpropanoid pathway have emerged as potential biomarkers of systemic acquired resistance and hypersensitive responses. These conserved metabolites constitute critical components of legume innate immunity and hold promise as screenable biochemical markers in resistance phenotyping pipelines. Despite metabolic overlaps between common beans and other legumes, species-specific metabolomic datasets for R. solani interactions across legume crops remain largely absent. Establishing such profiles will be crucial for dissecting the biochemical basis of resistance and for identifying metabolic traits associated with durable defence.

5.5. Integration of Multi-Omics Techniques

Despite isolated advances in genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic domains, integrative omics studies in legumes are lacking. The cross-pathogenic nature of AGs across legumes (AG 2 and 3 in chickpeas, AG-4 in mungbean) demands AG-informed resistance strategies. A system biology framework that combines transcriptomics (RNA sequencing), secretome mapping and metabolic profiling layered with high throughput phenotyping can reveal core responses and AG- specific host responses.

We propose the development of AG-specific host and pathogen interaction models. Profiling transcriptional and metabolic responses of legumes to AG-1 IA, AG-2-IIB and AG-4 can help uncover:

Coumarin biosynthesis genes

Detoxification enzymes (e.g., GSTs, peroxidases)

Effector-triggered signaling pathways (e.g., JA/SA cross talk)

Figure 2.

A systems biology approach for the development of durable resistance against Rhizoctonia solani. Integration of multi-omics platforms including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics enables the identification of resistance markers. These markers, in combination with high-throughput phenotyping, support the selection of resistant plant genotypes. The approach facilitates a comprehensive understanding of host–pathogen interactions and accelerates resistance breeding.

This integrated knowledge will accelerate the identification of molecular markers for durable, broad-spectrum resistance and reduce reliance on classical resistance screening.

Recommendations for future research:

Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA): to identify modules of co-regulated genes and metabolites correlated with resistance traits across AGs.

Dual RNA-seq: to simultaneously capture host and pathogen transcriptomes during infection, enabling precise mapping of effector–target interactions and defence gene induction dynamics.

GWAS + Omics integration: Combine genome-wide association studies with transcriptomic or metabolomic data to identify expression QTLs (eQTLs) or metabolite QTLs (mQTLs) associated with resistance against specific AGs.

Comparative AG profiling in legumes: Functional and secretome comparison of isolates representing major AGs (AG-1, AG-2-2, AG-4) infecting legume, to identify conserved vs. AG-specific effectors and target pathways.

By merging omics layers (genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics), researchers can pinpoint resistance hubs—conserved regulatory nodes and metabolic bottlenecks—critical for durable, broad-spectrum defence. This will not only guide the rational design of breeding targets but also enhance our understanding of co-evolutionary dynamics in the R. solani–legume pathosystem.

6. Methodological Limitations and Research Gaps

Although there is a significant increase in the literature on the variability and functional genomics of Rhizoctonia solani, the methodological limitations persist, concerning legume-specific research. These limitations affect the accuracy, reproducibility and applicability of the data and hinder the development of precise management strategies.

Most studies evaluating Rhizoctonia solani rely on pooled data, often grouping legumes with cereals. This lack of specificity in data brings ambiguity in the diversity of AGs and prevents a clear understanding of specific host-pathogen interactions in legumes.

While ITS sequencing is widely used and considered highly reliable for AG classification, it lacks sufficient resolution to pathogenicity-related genes. Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST), effector profiling and genome-wide SNP analysis can be a breakthrough in understanding functional diversity.

Transcriptomics studies, although powerful, are still scarce in the context of legume isolates. As a result, there is limited insight into the effector-receptor interactions and host adaptation mechanism that could aid resistance breeding.

Studies typically focus on either morphological and cultural traits or molecular characterization. There is a need for an integrative approach that correlates phenotypic traits with specific anastomosis groups and enables rapid screening and effective surveillance of epidemics.

No studies were found directly profiling secreted enzymes or effectors in pulses. Most available studies focus on transcriptomics, metabolomics, or qRT-PCR in pulse–R. solani systems, not secretome analyses.

7. Conclusion

Rhizoctonia solani remains a significant constraint in legume production, AG1-IA and AG-4 HGI specifically being highly virulent strains causing significant losses. The extensive phenotypic and molecular variability in South Asia reflects its high adaptive potential, posing challenges for durable resistance breeding. Conventional screening methods, although simple and economic, often fail to capture the dynamics of host-pathogen interactions shaping disease outcomes.

To address these limitations, integration of multi-omics technologies including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics and phenomics- is essential for a systemic understanding of R. solani pathogenesis and legume defence responses. Genomic tools such as QTL mapping and GWAS can identify the resistance gene loci, while transcriptomic profiling at the infection stage can reveal AG and cultivar-specific expression patterns of key defence genes, including PR proteins, ROS detox enzymes and transcription factors. Proteomic and metabolomic approaches contribute to understanding resistance-related proteins, post-translational modifications and secondary metabolites (e.g., salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, phytoalexins) central to immune signaling.

Despite these advancements in other crop models and crop systems, legumes remain largely unexplored at the omics level. No secretome, effector or functional transcriptome study have been reported for R. solani in legumes. This represents a critical knowledge gap that must be addressed to enable precision breeding for a durable resistance. Functional validation of candidate resistance genes, transcriptomic responses to AG1-IA/AG-4 HGI and secretome profiling of aggressive isolates is required. Furthermore, integration through network modelling will facilitate the identification of core resistance networks and potential biomarkers for marker-assisted selection (MAS) and gene editing through CRISPR/cas technique. Bioagent induced resistance as shown in mung beans should also be explored in other legumes using high-throughput gene expression and phenomics analysis.

In conclusion, combining multi-omics approaches with robust phenotyping and AG level pathogen diagnosis will provide the foundational knowledge necessary to develop durable, broad spectrum resistance to R. solani in legumes. This holistic strategy can also serve as a model for disease management in other under studied legume crops facing similar necrotrophic pathogens.

Author Contributions

Shagun Grewal is the sole contributor to the conceptualization, data collection, analysis, writing, and editing of this manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely thanks Dr. Shiwali Dhiman for her encouragement and motivation to undertake and complete this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

References

- Abate, T., Alene, A. D., Bergvinson, D., Shiferaw, B., Silim, S., Orr, A., & Asfaw, S. (2012). Tropical grain legumes in Africa and south Asia: knowledge and opportunities. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics.

- Abbas, A., Ali, A., Hussain, A., Ali, A., Alrefaei, A. F., Naqvi, S. A. H., Rao, M. J., Mubeen, I., Farooq, T., Ölmez, F., & Baloch, F. S. (2023). Assessment of genetic variability and evolutionary relationships of Rhizoctonia solani inherent in legume crops. Plants, 12(13), 2515. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. P., Hane, J. K., Stoll, T., Pain, N., Hastie, M. L., Kaur, P., Hoogland, C., Gorman, J. J., & Singh, K. B. (2016). Proteomic analysis of Rhizoctonia solani identifies infection-specific, redox associated proteins and insight into adaptation to different plant hosts. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 15(4), 1188–1203. [CrossRef]

- Basbagci, G., Unal, F., Uysal, A., & Dolar, F. S. (2019). Identification and pathogenicity of Rhizoctonia solani AG-4 causing root rot on chickpea in Turkey. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research, 17(2), e1007. [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, A., Kumar, A. H. M., Singh, A., Debnath, P., Gupta, A. K., Yadav, G. K., Prashantha, S. T., & Bashyal, B. M. (2024). First report of Rhizoctonia blight caused by Rhizoctonia solani on Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis) in India. Plant Disease, 108(12), 3413. [CrossRef]

- Bara, B. (2007). Epidemiology and management of web blight disease of urdbean (Master's thesis). Birsa Agricultural University, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India.

- Ben Youssef, N. O., Krid, S., Rhouma, A., & Kharrat, M. (2010). First report of Rhizoctonia solani AG 2-3 on chickpea in Tunisia. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 49(3), 253–257.

- Cantarel, B. L. et al.(2009). The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 233–238.

- Carling, D. E., Kuninaga, S. & Brainard, K. A. (2002). Hyphal anastomosis reactions, rDNA-internal transcribed spacer sequences, and virulence levels among subsets of Rhizoctonia solani AG-2 and AG-BI. Mycologia, 94(2), 250–256. [CrossRef]

- Chandel, S. (2022). Studies on web blight of urdbean caused by Rhizoctonia solani and its management (Master's thesis, Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur, India).

- Chatak, S., and Banyal, D. K. (2020). Evaluation of IDM components for the management of urdbean anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum truncatum (Schwein) Andrus and Moore. Himachal Journal of Agricultural Research 46, 156–161.

- Dubey, S. C., & Singh, B. (2010). Seed treatment and foliar application of insecticides and fungicides for management of cercospora leaf spots and yellow mosaic of mungbean (Vigna radiata). International Journal of Pest Management, 56(4), 309–314. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S. C., Tripathi, A., Upadhyay, B. K., & Deka, U. K. (2014). Diversity of Rhizoctonia solani associated with pulse crops in different agroecological regions of India. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 30(6), 1699–1715. [CrossRef]

- Dubey S.C., Tripathi A., & Upadhyay B.K. (2012). Molecular diversity analysis of R. solani isolates infecting various pulse crops in different agroecological regions of India. Folia Microbiologica, 57(6), 513–524. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.C., Tripathi, A. & Tak, R. (2018). Expression of defence-related genes in mung bean varieties in response to Trichoderma virens alone and in the presence of Rhizoctonia solani infection. 3 Biotech 8, 432. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Garcia, V., Portal Onco, M., & Rubio Susan, V. (2006). Review. Biology and systematics of the genus Rhizoctonia. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research, 4(1), 55-79. [CrossRef]

- González, D., Rodríguez, M. A., Mitchell, D. J. & Wilhelm, S. (2001). Differentiation of Rhizoctonia solani AG groups by RFLP analysis of the ITS region. Mycological Research, 105(7), 841–852. [CrossRef]

- Gupta AB, Gupta RP, Singh RV (2002). Effect of season on web blight development and its impact on yield in mungbean. IPS (MEZ) Annual Meet and National Symposium on Integrated Management of Plant Disease of Mid-Eastern India, 5-7 Dec. Hend at NDUA & T, Kumarganj, Faizabad. SOllvenir and Abstract, 30.

- Hane JK, Anderson JP, Williams AH, Sperschneider J, Singh KB (2014) Genome Sequencing and Comparative Genomics of the Broad Host-Range Pathogen Rhizoctonia solani AG8. PLoS Genet 10(5): e1004281. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik A, Roberts DP, Ramaprasad A, Mfarrej S, Nair M, Lakshman DK and Pain A (2022) Pangenome Analysis of the Soilborne Fungal Phytopathogen Rhizoctonia solani and Development of a Comprehensive Web Resource: RsolaniDB. Front. Microbiol. 13:839524. [CrossRef]

- Kuirya, S. P., Mondal, A., Banerjee, S., & Dutta, S. (2014). Morphological variability in Rhizoctonia solani isolates from different agroecological zones of West Bengal, India. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection, 47(6), 728–736. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., & Tamura, K. (2018). MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35(6), 1547–1549. [CrossRef]

- Lal M and Kandhari J. (2009). Cultural and morphological variability in Rhizoctonia solani isolates causing sheath blight of rice. Journal of Mycology and Plant Pathology, 39(1):77-81.

- Li, D., Li, S., Wei, S. et al. Strategies to Manage Rice Sheath Blight: Lessons from Interactions between Rice and Rhizoctonia solani. Rice 14, 21 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Li X, An M, Xu C, Jiang L, Yan F, Yang Y, Zhang C and Wu Y (2022) Integrative transcriptome analysis revealed the pathogenic molecular basis of Rhizoctonia solani AG-3 TB at three progressive stages of infection. Front. Microbiol. 13:1001327. [CrossRef]

- Moliszewska, E., Maculewicz, D., & Stępniewska, H. (2023). Characterization of three-nucleate Rhizoctonia AG-E based on their morphology and phylogeny. Scientific Reports, 13, 17328. [CrossRef]

- Misawa, T., Toda, T., Kayamori, M., Kurose, D., & Sasaki, J. (2017). First report of Rhizoctonia disease of lily caused by Rhizoctonia solani AG-11 in Japan. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 83(6), 406–409. [CrossRef]

- Mayo-Prieto, S., Marra, R., Vinale, F., Rodríguez-González, Á., Woo, S. L., Lorito, M., Gutiérrez, S., & Casquero, P. A. (2019). Effect of Trichoderma velutinum and Rhizoctonia solani on the Metabolome of Bean Plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(3), 549. [CrossRef]

- Nair, R. M., Chaudhari, S., Devi, N., Shivanna, A., Gowda, A., Boddepalli, V. N., Pradhan, H., Schafleitner, R., Jegadeesan, S., & Somta, P. (2024). Genetics, genomics, and breeding of black gram (Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper). Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1273363. [CrossRef]

- Neelam. (2013). Molecular characterization of Rhizoctonia solani Kühn isolates causing web blight in urdbean (Vigna mungo L.) and their variability on various hosts (Doctoral dissertation, Govind Ballabh Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, India). Krishikosh.

- Negi, H., and Vishunavat, K. (2006). Urdbean leaf crinkle infection in relation to plant age, seed quality, seed transmission and yield in urdbean. Ann. Plant Sci. 14 (1), 169–172.

- Nitzan, N., Chaimovitsh, D., Davidovitch-Rekanati, R., Sharon, M., and Dudai, N. (2012). Rhizoctonia web blight—A new disease on mint in Israel. Plant Disease. 96:370-378.

- Oliver, R.P. & Solomon, P.S. (2010) New developments in pathogenicity and virulence of necrotrophs. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 13, 415–419.

- Pandey, S., Sharma, M., Kumari, S., Gaur, P. M., Chen, W., Kaur, L., et al. (2009). "Integrated foliar disease management of legumes," in Grain Legumes: Genetic improvement, Management and Trade. Ed. M. Ali, et al (Kanpur, India: Indian Society of Pulses Research and Development, Indian Institute of Pulses Research), 143–161.

- Parmeter, J. R. (Ed.). (2023). Rhizoctonia solani: Biology and pathology (Original work published 1970). University of California Press. [CrossRef]

- Priyatmojo, A., Sato, Y., Kanematsu, S., & Hyakumachi, M. (2001). Anastomosis grouping and genetic variation of Rhizoctonia solani isolates from leguminous vegetables in Japan. Mycoscience, 42(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, F., Bain, R. and Mcquilken, M. (2013), Survival of Sclerotia of Rhizoctonia solani AG3PT and Effect of Soil-Borne Inoculum Density on Disease Development on Potato. Journal Phytopathology, 161: 180-189. [CrossRef]

- Robison FM, Turner M, Jahn CE, et al. Common bean varieties demonstrate differential physiological and metabolic responses to the pathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Cell Environ. 2018; 41: 2141–2154. [CrossRef]

- Saksena, H. K., & Dwivedi, R. P. (1973). Web blight of black gram caused by Thanatephorus cucumeris. Indian Journal of Farm Sciences, 1(1), 58–61.

- Sharma, O. P., Bambawale, O. M., Gopali, J. B., Bhagat, S., Yelshetty, S., & Singh, S. K. (2011). Field guide: Mungbean and urdbean. National Centre for Integrated Pest Management.

- Sharon, M., Freeman, S., Kuninaga, S., Sneh, B. & Hyakumachi, M. (2006). Genetic structure of Rhizoctonia solani AG-1 IA populations from Israel, Japan, and the USA. Phytopathology, 96(5), 480–489. [CrossRef]

- Sharon, M., Freeman, S., Kuninaga, S., & Sneh, B. (2007). Genetic diversity, anastomosis groups, and virulence of Rhizoctonia spp. from strawberry. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 117(3), 247–265. [CrossRef]

- Sharon, M., Kuninaga, S., Hyakumachi, M., Naito, S., & Sneh, B. (2008). Classification of Rhizoctonia spp. Using rDNA-ITS sequence analysis supports the genetic basis of the classical anastomosis grouping. Mycoscience, 49(2), 93–114. [CrossRef]

- Saksena, H. K., & Dwivedi, R. P. (1973). Web blight of black gram caused by Thanatephorus cucumeris. Indian Journal of Farm Sciences, 1(1), 58–61.

- Shen, C.-m., Zhou, Z.-m., Li, C.-t., Zhao, Z.-f., Luo, L., & Yang, G.-h. (2024). First report of Rhizoctonia solani AG-2-2 IIIB causing rice sheath blight in China. Plant Disease, 108(12), 3650. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. (2006). Rhizoctonia solani in rice-wheat cropping system (PhD thesis). Department of Plant Pathology, G. B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, Uttarakhand, India.

- Spedaletti, Y., Aparicio, M., Cárdenas, G. M., Rodriguero, M., Taboada, G., Aban, C., Sühring, S., Vizgarra, O., & Galván, M. (2016). Genetic characterization and pathogenicity of Rhizoctonia solani associated with common bean web blight in the main bean growing area of Argentina. Journal of Phytopathology, 164(11–12), 1054–1063. [CrossRef]

- Verma, B. (2019). Studies on Rhizoctonia solani (Kühn) causing web blight of urdbean and its management (Master's thesis, Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India).

- Wang, D., Wu, W., Deng, D., Duan, C., Sun, S., & Zhu, Z. (2025). First report of Rhizoctonia solani causing leaf rot disease on mung bean (Vigna radiata) in China. Plant Disease. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Wibberg D, Andersson L, Tzelepis G, Rupp O, Blom J, Jelonek L, Pühler A, Fogelqvist J, Varrelmann M, Schlüter A, Dixelius C. Genome analysis of the sugar beet pathogen Rhizoctonia solani AG2-2IIIB revealed high numbers in secreted proteins and cell wall degrading enzymes. BMC Genomics. 2016 Mar 17;17:245. [CrossRef]

- Wigg, K. S., Brainard, S. H., Metz, N., Dorn, K. M., & Goldman, I. L. (2023). Novel QTL associated with Rhizoctonia solani Kühn resistance identified in two table beet × sugar beet F₂:₃populations using a new table beet reference genome. Crop Science, 63(2), 535–555. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., Fei, B., He, J. et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals the host selection fitness mechanisms of the Rhizoctonia solani AG1-IA pathogen. Sci Rep 7, 10120 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Xie, W., Cao, W., Lu, S., Zhao, J., Shi, X., Yue, X. et al. (2023) Knockout of transcription factor OsERF65 enhances ROS scavenging ability and confers resistance to rice sheath blight. Molecular Plant Pathology, 24, 1535–1551. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Yaduman, R., Singh, S., & Lal, A. A. (2019). Morphological and pathological variability of different isolates of Rhizoctonia solani Kühn causing sheath blight disease of rice. Plant Cell Biotechnology and Molecular Biology, 20(1&2), 73–80.

- Yamamoto, N. et al. (2019). Integrative transcriptome analysis discloses the molecular basis of a heterogeneous fungal phytopathogen complex, Rhizoctonia solani AG-1 subgroups. Scientific Reports, 9, 19626. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. G., Zhao, C., Guo, Z. J., & Wu, X. H. (2015). Characterization of a new anastomosis group (AG-W) of binucleate Rhizoctonia, causal agent for potato stem canker. Plant Disease, 99(12), 1757–1763. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. K., Xia, X. Y., Du, Q., Xia, L., Ma, X. Y., Li, Q. Y., & Liu, W. D. (2021). Genome sequence of Rhizoctonia solani Anastomosis Group 4 strains Rhs4ca, a widespread pathomycete in field crops. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 34(7), 826–829. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M., Wang, C., Wan, J., Li, Z., Liu, D., Yamamoto, N. et al. (2021) Functional validation of pathogenicity genes in rice sheath blight pathogen Rhizoctonia solani by a novel host-induced gene silencing system. Molecular Plant Pathology, 22, 1587–1598. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A., Lin, R., Zhang, D. et al. The evolution and pathogenic mechanisms of the rice sheath blight pathogen. Nat Commun 4, 1424 (2013). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).