Introduction

Black gram (Vigna mungo), commonly known as Urdbean in India, is among the 30 economically important legume species grown in the tropics (Abate et al., 2012). Being a short duration Kharif season crop it attains maturity within 60-90 days. In India, urdbean is extensively cultivated for dietary and medicinal purposes, while in Australia and USA it is primarily grown as a fodder crop (Jensen, 2006, as cited by Nair, 2023). Effective management of biotic stresses is essential as urdbean is susceptible to biotic stresses causing yield losses of up to 70% under Indian conditions (Sharma et al., 2011).

Urdbean is susceptible to a wide range of pathogens including fungi, bacteria, viruses and nematodes which significantly reduce crop yield and quality. Key diseases inflicting major economic losses include web blight (Rhizoctonia solani Kühn) (Kumar et al., 2014), powdery mildew (Erysiphe polygoni DC) (Pandey et al. 2009), Cercospora leaf spot (Cercospora canescens) (Dubey and Singh 2010), anthracnose (Colletotrichum capsici) (Chatak and Banyal, 2020), Mungbean Yellow Mosaic Virus (Dubey and Singh, 2010) and Urdbean Leaf Crinkle Virus (Negi and Vishunavat, 2006). The occurrence and severity of these diseases largely depend on prevailing agro-climatic conditions.

Among these, web blight caused by Rhizoctonia solani Kühn (teleomorph: Thanatephorus cucumeris [Frank] Donk) is particularly destructive in the North Indian plains and the lower hills of the Shivalik ranges. On an average moderate disease incidence reduces seed yield by 35.6% (Kumar et al., 2014) and broadly by 33% to 40% (Singh, 2006; Gupta and Singh, 2002) relative to the healthy check. Disease incidence has also been reported from Punjab, Haryana, Bihar, Rajasthan and other parts of India (Saksena and Dwivedi, 1973). After the widespread adoption of varieties resistant to yellow and mung bean mosaic virus, web blight has emerged as a dominant threat to pulse production leading to significant economic losses.

Rhizoctonia solani is a soil borne saprotrophic as well as necrotrophic plant pathogenic fungus (Moliszewska et al. 2023), it has a wide host range and causes disease in more than 200 plant species including legumes, cereals, oilseeds and ornamentals (Zhang et al., 2021). Its broader host range and competitive saprotrophic growth makes it an important economic pathogen (Parmeter, 1970). The initial symptoms of Rhizoctonia solani attack includes formation of water soaked lesions near the petiole of the trifoliate leaf which enlarges and affects the aerial parts resulting in twisted twigs and shrivelled pods. The lesions coalesce to cause leaf blight and the disease progresses to web blight characterized by formation of webs like mycelium on the aerial parts of the plant which finally forms sclerotia (Bara, 2007). Studies show that the fungal sclerotia is highly resistant to stress conditions and remains viable in the soil for several years under favourable conditions (Wigg et al. 2023). Another study pointed out a 25-50% germination rate of the sclerotia after burial at 5cm depth for 2 years (Ritchie et al. 2013). Given its colossal variability and adaptability, a thorough understanding of the phenotypic traits and molecular profiling of R. solani is crucial.

This review aims to consolidate the understanding on the variability of Rhizoctonia solani at morphological and molecular level. This knowledge is pivotal to guide the breeders, researchers and students in comprehending Rhizoctonia solani and developing effective disease management strategies. Special emphasis is placed on molecular methods which can pave the path for the development of host resistance that promote environmentally sustainable crop production while reducing the reliance on chemical inputs creating a robust and sustainable production system.

Pathogen Biology

Rhizoctonia solani is a filamentous fungus lacking both sexual and asexual spores in its anamorphic stage (Gracia et al., 2006). It has a characteristic right angle branching accompanied by a narrow constriction and a septum at the point of branching making it clearly identifiable under a compound microscope (Lal and Khandari, 2009).

The genus can broadly be divided into two categories- binucleate Rhizoctonia (BNR) and multinucleate Rhizoctonia based on the average number of nuclei present in each cell (Moliszewska et al., 2023). It is a species complex comprising genetically distinct yet morphologically similar strains, many of which are aggressive plant pathogens. Within the genus, Rhizoctonia is divided into 13 anastomosis groups, from AG-1 to AG-13, while AG-B1 (a bridging isolate) was classified as the 14th anastomosis groups on the basis of anastomosis reactions between their hyphae (Dubey et al. 2014) (Spedaletti et al., 2016); later AG-B1 was reclassified as AG-2-2B (Basbagci et al., 2019). Studies have identified 22 anastomosis subgroups for BNR (Yang et al., 2015). Each AG has their specific pathogenic traits, attributing to a higher adaptability.

Molecular characterization of ITS 1-5, 8S- ITS 2 regions of ribosomal DNA and their comparative analysis with sequence database is widely used for AGs categorization and is the most reliable classification method for Rhizoctonia spp. (Sharon et al., 2007). The classical AGs, although used for a long time, are found ambiguous and unreliable as some isolates fail to anastomose within the same group while occasionally different AGs anastomose giving false positives (Sharon et al., 2008). Currently molecular markers are widely used to construct phylogenetic trees using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA), based on the maximum likelihood of the isolate from the sequence database (Kumar et al., 2018).

Rhizoctonia solani poses a serious threat to several globally important crops. The host range of Rhizoctonia solani is still expanding with new disease incidences occurring every year which raises concern regarding its adaptability. In the last decade Rhizoctonia solani is reported from various parts of the globe causing diseases in plants which were not considered as traditional hosts. In recent years, Rhizoctonia solani is reported to be associated with Web Blight (WB) of mint in Israel (Nitzan et al., 2012), Rhizoctonia blight is reported to affect Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis) in India (Bahadur et al., 2024).

Various AGs are also found to cause cross pathogenicity broadening their respective host ranges, AG 2-3 was reported to cause root and collar rot of chickpea in Tunisia (Youssef et al., 2010), AG 2-2 III B caused sheath blight of rice in China (Shen et al., 2024), AG 11 caused blight of lily in Japan (Misawa et al., 2017), apart from this Rhizoctonia solani is found causing novel disease in the existing hosts, causing leaf rot of mung bean in China (Wang, 2025). Rhizoctonia solani Kühn as a causal organism of web blight in urdbean was identified in Uttarakhand state of India (Saksena and Dwivedi, 1973) since its reporting, it continues to affect crops, appearing sporadically and occasionally as an epidemic, due to the accumulation of sclerotia in the soil.

Phenotypic and Pathogenic Diversity of Rhizoctonia solani

Phenotypic and pathogenic variability is crucial in the epidemiology of Rhizoctonia solani and makes it challenging to devise management strategies. The diversity is evident from morphological, cultural and range of pathogenic effects in the host plants.

Morphological and Cultural Traits

Morphological and cultural variability is evaluated using Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium and includes diverse colony colour, texture, margins, zonation, pigmentation, growth rate and sclerotial traits. Isolates collected from urdbean fields of the central Indian agro-climatic zone reveal variation in colony morphology ranging from initial white colony colour to light brown and later dark brown with age (Chandel, 2022). In urdbean Rhizoctonia solani was found to produce on average 59.4% more sclerotia under lab conditions relative to mung bean (Neelam, 2013).

The colony growth rate was found moderate to fast covering the entire petri plate within 3-4 days with sparse to profuse (septate, hyaline, aerial) mycelium. Fast growth rate is positively correlated with pathogenicity; faster growing isolates are more virulent than the slow growing isolates.

Three types of hyphae were found:

Runner hyphae – long, straight, creeping.

Lobate hyphae – short, swollen with appressoria and penetration pegs.

Monilioid hyphae – aggregated to form sclerotia.

Although extensive data for urdbean is not available, but independent research (

Table 1) on

Rhizoctonia solani in other kharif crops support presence of high variability in the colony morphology and growth rates within the North Indian plains.

Thermal Adaptability

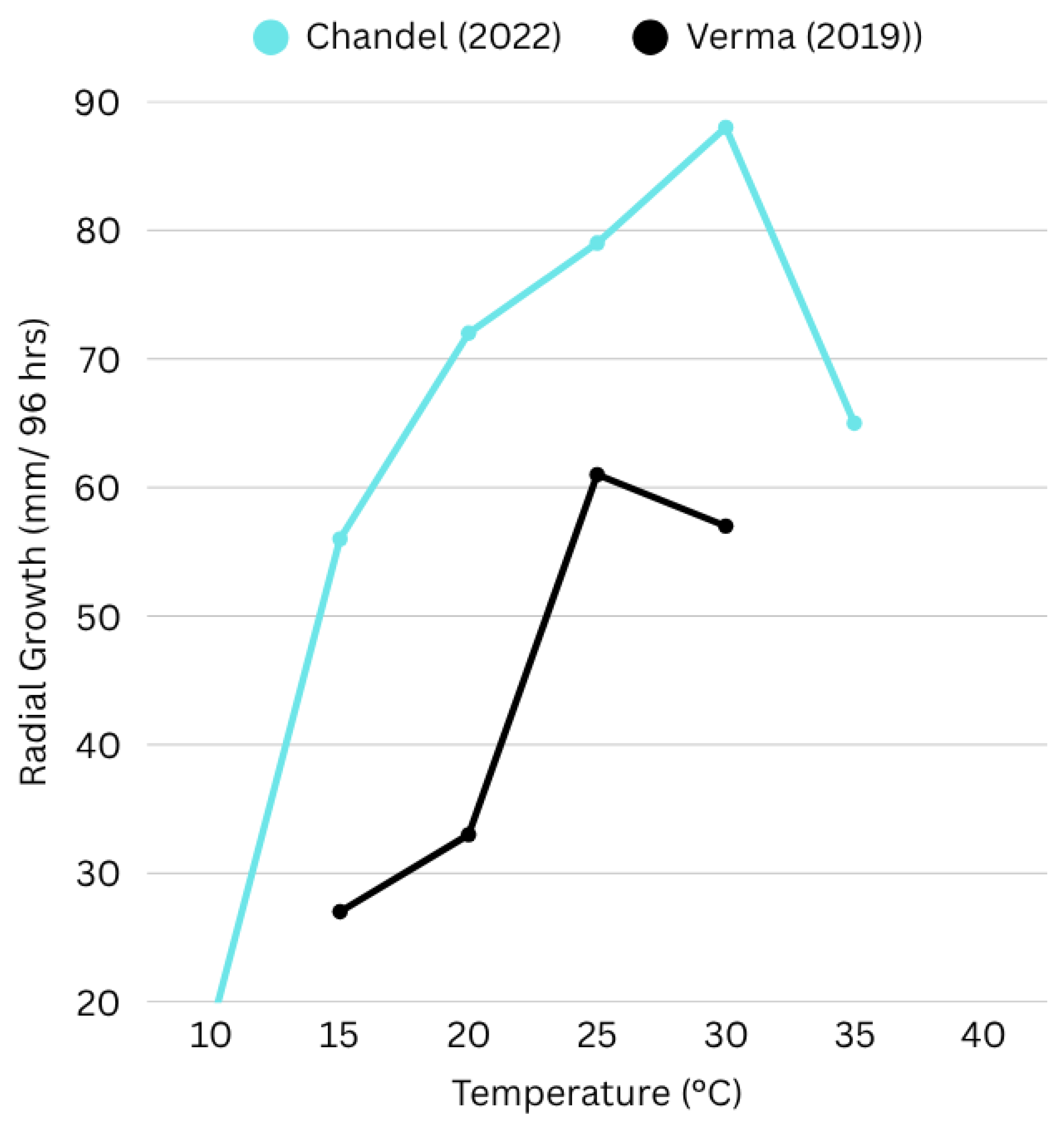

Rhizoctonia solani withstands a wide range of temperature extremes, but studies on urdbean field isolates revealed that optimal growth temperature is 25°C to 30°C (Figure 1). Maximum radial growth is at 25°C while maximum sclerotia development is observed at 30°C (Verma, 2019) (Chandel, 2022) in lab-based studies on urdbean isolates. Although the optimal temperature varies for various AG subgroups.

Figure 1.

Effect of temperature on radial growth of Rhizoctonia solani isolates, created from data adapted from (Chandel, 2022) (Verma, 2019). The graph illustrates differential growth rates of isolates under varying temperature conditions over 96 hours of incubation. Chandel (2022) observed optimal growth at 30°C, with a marked decline at 35°C, whereas Verma (2019) recorded peak growth at 25°C. These variations unveil the influence of environmental factors on the phenotypic diversity of Rhizoctonia solani.

Figure 1.

Effect of temperature on radial growth of Rhizoctonia solani isolates, created from data adapted from (Chandel, 2022) (Verma, 2019). The graph illustrates differential growth rates of isolates under varying temperature conditions over 96 hours of incubation. Chandel (2022) observed optimal growth at 30°C, with a marked decline at 35°C, whereas Verma (2019) recorded peak growth at 25°C. These variations unveil the influence of environmental factors on the phenotypic diversity of Rhizoctonia solani.

After comparative analysis following correlations have been derived among the phenotypic trait and pathogenicity: (Verma, 2019) (Neelam, 2013)

Faster colony growth rate → associated with higher virulence

Early and abundant sclerotial production → indicative of increased epidemic potential

Presence of pigmentation and concentric zonation → frequently observed in highly virulent isolates

Compact, fluffy colony texture → often correlated with increased pathogenic potential

These associations support the hypothesis that phenotypic markers could serve as preliminary indicators of virulence, facilitating rapid screening of aggressive isolates for use in resistance breeding and surveillance of epidemics. While the morphological variability is evident in the fields, molecular tools enabled deeper insights into the genetic structures and functional analysis of Rhizoctonia solani.

Molecular Variability and Anastomosis Groups in Rhizoctonia solani

Rhizoctonia solani is a genetically diverse, multinucleate soil-borne pathogen. It exhibits extensive host range and adaptability. Molecular characterization is pivotal in elucidating the genetic variability among the Rhizoctonia solani population in various legume crops. Techniques such as ITS-rDNA sequencing, ISSR profiling and transcriptome analysis reveals substantial variation within and between AGs, which influences pathogenicity, host preference and disease management strategies.

Case Study 1: Dubey et al., 2012

Urdbean isolates were found associated with multiple AGs: AG-1, AG-2-2, AG-2-3, AG-3, AG-4, AG-5.

The presence of AG-4 in black gram was confirmed by RPBU5 isolate based on ITS-rDNA sequencing.

While isolates RPBU7, RUKU4, RUPU23, RUPU18, RUPU50 were associated with AGs 3, 2-2, 2-3.

In contemporary studies using ISSR markers, AG-1-IA isolates was found infecting urdbean in Uttarakhand (Neelam, 2013).

Case study 2: Abbas et al., 2023

Legumes harbour Rhizoctonia solani isolates from various AGs which suggests that often there is no clear host specificity. This indicates that genetic divergence among isolates is more influenced by AGs lineage than host driven selection highlighting the importance of patho-type over host in resistance breeding. For this study ITS sequences were utilized to classify legume-infecting Rhizoctonia solani isolates which revealed clustering by AG (AG-1, AG-2, AG-4) instead of host. Principle Coordinate Analysis also supported AG-wise grouping over host-specific divergence.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of two molecular studies on Rhizoctonia solani infecting legumes, highlighting methodological approaches, AG diversity and implications for disease management. Adapted from Dubey et al. (2012) and Abbas et al. (2023).

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of two molecular studies on Rhizoctonia solani infecting legumes, highlighting methodological approaches, AG diversity and implications for disease management. Adapted from Dubey et al. (2012) and Abbas et al. (2023).

| Aspect |

Case Study 1(Dubey et al., 2012) |

Case Study 2(Abbas et al., 2023) |

| Sample Origin |

89 isolates from 21 Indian states across 16 agro-ecological zones |

Legume-infecting R. solani isolates from multiple regions (global dataset) |

| Host Focus |

Primarily pulses (including urdbean) |

Broad range of legume crops |

| Molecular Techniques Used |

URPs (Universal Rice Primers), RAPD, ISSR |

ITS-rDNA sequencing and PCoA (Principal Coordinate Analysis) |

| Anastomosis Groups (AGs) Identified |

AG-1, AG-2-2, AG-2-3, AG-3, AG-4, AG-5 in urdbean isolates |

AG-1, AG-2, AG-4; clustering not host-specific but AG-specific |

| Key Findings |

High genetic polymorphism-Multiple AGs infect urdbean, Region-specific diversity |

Isolates clustered by AG, not by host- AG lineage determines genetic divergence more than host specificity |

| Implications |

Need for region-specific management strategies- Multiple AGs complicate breeding for resistance |

Breeding for AG-targeted resistance may be more effective than host-based strategies- Reinforces AG-specific surveillance |

ITS Based Phylogenetic and AG Differentiation

Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) is the most widely used molecular method for classification of Rhizoctonia solani. It consistently distinguishes between Anastomosis groups (AG-1 to AG-13) as well as subgroups (e.g., AG-1-IA, AG-2-2WB). ITS based phylogenetic trees aligns well with classical AG grouping and affirms the genetic basis of anastomosis group classification (Sharon et al., 2008).

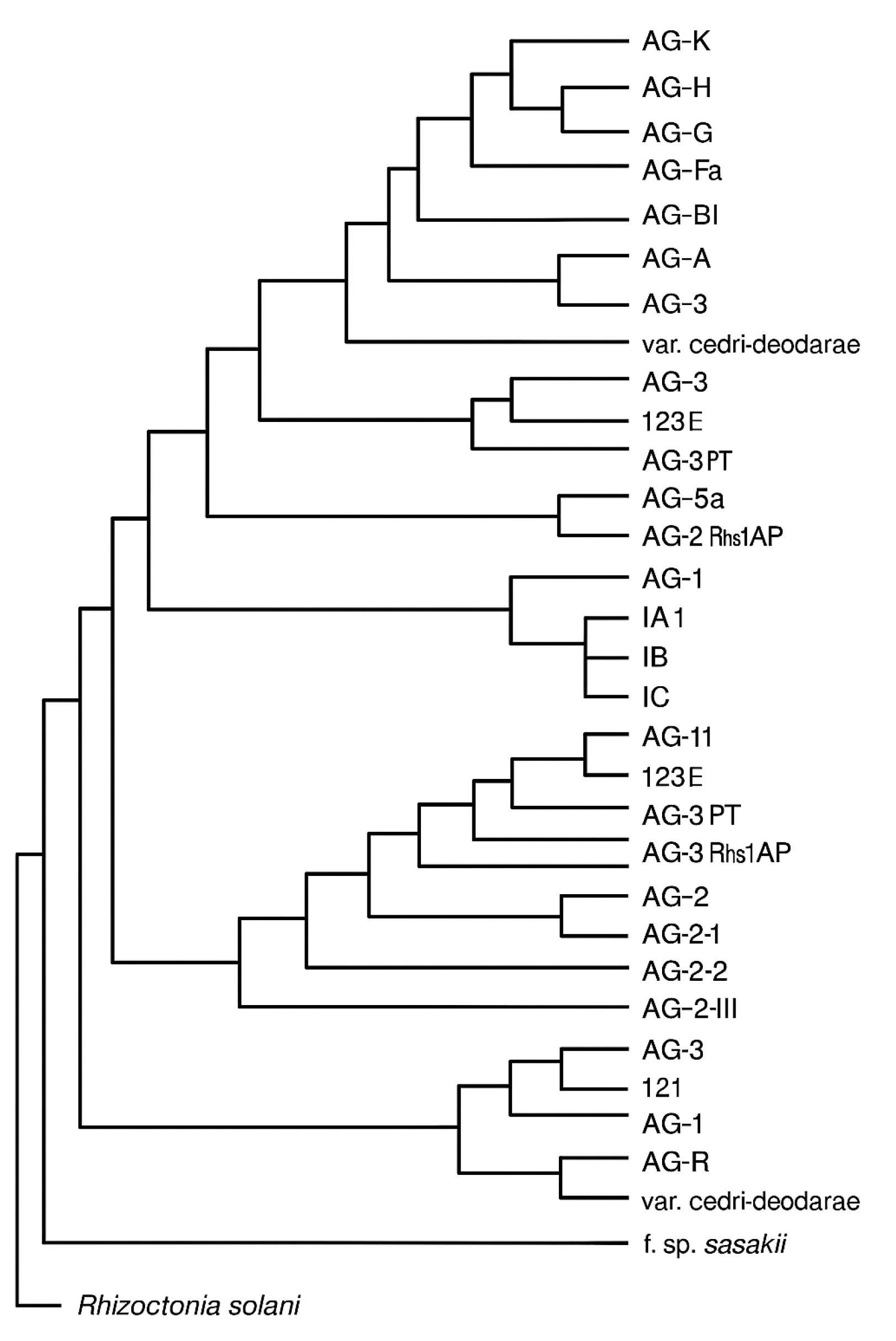

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree illustrating evolutionary relationships among Rhizoctonia solani anastomosis groups (AGs), subgroups and related variants. This representative tree includes AG-1 (IA, IB, IC, ID), AG-2 (2-1, 2-2, IIIB), AG-3 (PT, Rhs1AP), AG-4 (HGI, HGII, HGIII), AG-5, AG-6 to AG-9 and others including Rhizoctonia solani var. cedri-deodarae and f. sp. sasakii. The tree is based on molecular studies using ITS-rDNA, RFLP and sequence analyses adapted from multiple sources (Sharon et al., 2006; Carling et al., 2002; González et al., 2001; Priyatmojo et al., 2001). This representation reflects both inter- and intra-AG divergence informed by genetic similarity.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree illustrating evolutionary relationships among Rhizoctonia solani anastomosis groups (AGs), subgroups and related variants. This representative tree includes AG-1 (IA, IB, IC, ID), AG-2 (2-1, 2-2, IIIB), AG-3 (PT, Rhs1AP), AG-4 (HGI, HGII, HGIII), AG-5, AG-6 to AG-9 and others including Rhizoctonia solani var. cedri-deodarae and f. sp. sasakii. The tree is based on molecular studies using ITS-rDNA, RFLP and sequence analyses adapted from multiple sources (Sharon et al., 2006; Carling et al., 2002; González et al., 2001; Priyatmojo et al., 2001). This representation reflects both inter- and intra-AG divergence informed by genetic similarity.

Transcriptomics and Genomic Insights

With the advent of biotechnology, modern molecular methods have leveraged whole transcriptome and genome sequencing to decode pathogenicity related genes and subgroup divergence.

Transcriptome studies show that significant genetic and functional diversity exists within AGs. Even within the same anastomosis group (AG-1), subgroups (IA, IB, IC) show considerable divergence (Yamamoto et al., 2019). This explains variation in virulence patterns and host range among the same AGs. However its functional validation in urdbean remains to be tested.

Certain subgroups (eg. AG-1-IA) secrete more proteins (necrosis-inducing proteins NIPs), effectors and toxin biosynthesis genes than other subgroups (AG-1-IB, AG-1-IC) (Yamamoto et al., 2019). Enabling more efficient detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through glutathione S-transferases and peroxidases, enhancing pathogenicity which in turn enhances the severity of the infection. As there is not a single gene but a network of genes which underscore the need for a durable resistance in legumes which require targeting of multiple pathways.

Methodological Limitations in Current Studies

Although the increase in the literature on the variability of Rhizoctonia solani, the methodological limitations still persists, specially concerning urdbean specific research. These limitations affect the accuracy, reproducibility and applicability of the data and hinders the development of precise management strategies.

The majority of studies evaluating Rhizoctonia solani rely on pooled data, often grouping urdbean with other legumes or even cereals. This lack of specificity in data brings ambiguity in the diversity of AGs and prevents the clear understanding of specific host pathogen interactions in urdbean.

- 2.

Over reliance on ITS-rDNA for molecular characterization

While ITS sequencing is widely used and considered highly reliable for AGs classification, they lack sufficient resolution to pathogenicity related genes. Multi locus sequence typing (MLST), effector profiling and genome wide SNP analysis can be a breakthrough in understanding functional diversity.

- 3.

Limited functional genomics studies

Transcriptomics studies, although powerful, are still scarce in the context of urdbean isolates. As a result there is limited insight into the effector-receptor interactions and host adaptation mechanism that could aid resistance breeding.

- 4.

Low Integration Between Phenotypic and Genotypic Data

Studies typically focus on either morphological and cultural traits or molecular characterization. There is a need for an integrative approach that correlates phenotypic traits with specific anastomosis groups and enables rapid screening and effective surveillance of epidemics.

Conclusions

Rhizoctonia solani, the incitant of web blight in urdbean, presents a daunting challenge to the pulse production in India due to its immense phenotypic and molecular variability. Studies across diverse agro-ecological zones confirms the complex genetic variability among the isolates, many of which belong to diverse anastomosis groups (AG-1 to AG-13) and exhibit significant differences in cultural characteristics, thermal adaptability and virulence patterns. This heterogeneity impedes the development of uniform diagnostic and management strategies.

Recent advances in molecular biology particularly whole genome sequencing and transcriptomics have uncovered the functional basis of this diversity, revealing that even isolates within the same AG differ considerably in their secretions, effector profiles and ROS detoxification capacity to wade the host defences. Notably, AG-1 IA isolates have been shown to secrete a higher number of virulence-associated proteins and display broader host range adaptability which further contribute to their increased aggressiveness on legumes including urdbean.

Despite these advances, a significant research gap persists. There is a dearth of urdbean specific research studies that integrate phenotypic, molecular and transcriptomics data to draw meaningful correlations between isolate-diversity and field disease outcomes. Most studies still rely on traditional disease management methods and even molecular studies are limited to ITS- based classification, which although useful for AG identification, does not fully uncover the functional variability required for breeding durable resistance among the crops. Furthermore, comparative modern molecular studies on Rhizoctonia solani from urdbean are rare, limiting our ability to identify robust bio-markers for early diagnosis and host resistance screening.

Future Prospects

In order to develop sustainable and targeted disease management strategies, research focus should be on:

Expanding multi-locus molecular characterization and profiling of transcriptome of Rhizoctonia solani in urdbean growing regions.

Establishment effector- based diagnostics to differentiate aggressive pathotypes.

Investigation on the interaction of virulence genes of Rhizoctonia solani with the host resistance pathways through functional genomics.

Promotion of region specific Integrated Disease Management (IDM) strategies tailored to the prevalent AG and climatic conditions.

Integration of phenotypic and genotypic screening into breeding programs to develop durable resistance in the crop varieties.

A deeper understanding of the molecular architecture of Rhizoctonia solani infecting urdbean, combined with improved surveillance tools and resistant cultivars, will pave the way for more resilient and sustainable pulse production in the Indian subcontinent.

References

- Abate, T., Alene, A. D., Bergvinson, D., Shiferaw, B., Silim, S., Orr, A., & Asfaw, S. (2012). Tropical grain legumes in Africa and south Asia: knowledge and opportunities. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics.

- Abbas, A., Ali, A., Hussain, A., Ali, A., Alrefaei, A. F., Naqvi, S. A. H., Rao, M. J., Mubeen, I., Farooq, T., Ölmez, F., & Baloch, F. S. (2023). Assessment of genetic variability and evolutionary relationships of Rhizoctonia solani inherent in legume crops. Plants, 12(13), 2515. [CrossRef]

- Basbagci, G., Unal, F., Uysal, A., & Dolar, F. S. (2019). Identification and pathogenicity of Rhizoctonia solani AG-4 causing root rot on chickpea in Turkey. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research, 17(2), e1007. [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, A., Kumar, A. H. M., Singh, A., Debnath, P., Gupta, A. K., Yadav, G. K., Prashantha, S. T., & Bashyal, B. M. (2024). First report of Rhizoctonia blight caused by Rhizoctonia solani on Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis) in India. Plant Disease, 108(12), 3413. [CrossRef]

- Bara, B. (2007). Epidemiology and management of web blight disease of urdbean (Master’s thesis). Birsa Agricultural University, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India.

- Ben Youssef, N. O., Krid, S., Rhouma, A., & Kharrat, M. (2010). First report of Rhizoctonia solani AG 2-3 on chickpea in Tunisia. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 49(3), 253–257.

- Carling, D. E., Kuninaga, S. & Brainard, K. A. (2002). Hyphal anastomosis reactions, rDNA-internal transcribed spacer sequences, and virulence levels among subsets of Rhizoctonia solani AG-2 and AG-BI. Mycologia, 94(2), 250–256. [CrossRef]

- Chandel, S. (2022). Studies on web blight of urdbean caused by Rhizoctonia solani and its management (Master’s thesis, Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur, India).

- Chatak, S., and Banyal, D. K. (2020). Evaluation of IDM components for the management of urdbean anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum truncatum (Schwein) Andrus and Moore. Himachal Journal of Agricultural Research 46, 156–161.

- Dubey, S. C., & Singh, B. (2010). Seed treatment and foliar application of insecticides and fungicides for management of cercospora leaf spots and yellow mosaic of mungbean (Vigna radiata). International Journal of Pest Management, 56(4), 309–314. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S. C., Tripathi, A., Upadhyay, B. K., & Deka, U. K. (2014). Diversity of Rhizoctonia solani associated with pulse crops in different agro-ecological regions of India. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 30(6), 1699–1715. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S. C., Tripathi, A., & Upadhyay, B. K. (2012). Molecular diversity analysis of Rhizoctonia solani isolates infecting various pulse crops in different agro-ecological regions of India. Folia Microbiologica, 57(6), 513–524. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Garcia, V., Portal Onco, M., & Rubio Susan, V. (2006). Review. Biology and systematics of the genus Rhizoctonia. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research, 4(1), 55-79. [CrossRef]

- González, D., Rodríguez, M. A., Mitchell, D. J. & Wilhelm, S. (2001). Differentiation of Rhizoctonia solani AG groups by RFLP analysis of the ITS region. Mycological Research, 105(7), 841–852. [CrossRef]

- Gupta AB, Gupta RP, Singh RV (2002). Effect of season on web blight development and its impact on yield in mungbean. IPS (MEZ) Annual Meet and National Symposium on Integrated Management of Plant Disease of Mid-Eastern India, 5-7 Dec. Hend at NDUA & T, Kumarganj, Faizabad. SOllvenir and Abstract, 30.

- Kuirya, S. P., Mondal, A., Banerjee, S., & Dutta, S. (2014). Morphological variability in Rhizoctonia solani isolates from different agro-ecological zones of West Bengal, India. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection, 47(6), 728–736. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Chand, G., Tripathi, H. S., & Kumar, A. (2014). Assessment of yield loss and evaluation of Urdbean genotypes against web blight. Annals of Plant Protection Sciences, 22(2), 395–397.

- Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., & Tamura, K. (2018). MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35(6), 1547–1549. [CrossRef]

- Lal M and Kandhari J. (2009). Cultural and morphological variability in Rhizoctonia solani isolates causing sheath blight of rice. Journal of Mycology and Plant Pathology, 39(1):77-81.

- Moliszewska, E., Maculewicz, D., & Stępniewska, H. (2023). Characterization of three-nucleate Rhizoctonia AG-E based on their morphology and phylogeny. Scientific Reports, 13, 17328. [CrossRef]

- Misawa, T., Toda, T., Kayamori, M., Kurose, D., & Sasaki, J. (2017). First report of Rhizoctonia disease of lily caused by Rhizoctonia solani AG-11 in Japan. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 83(6), 406–409. [CrossRef]

- Nair, R. M., Chaudhari, S., Devi, N., Shivanna, A., Gowda, A., Boddepalli, V. N., Pradhan, H., Schafleitner, R., Jegadeesan, S., & Somta, P. (2024). Genetics, genomics, and breeding of black gram (Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper). Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1273363. [CrossRef]

- Neelam. (2013). Molecular characterization of Rhizoctonia solani Kühn isolates causing web blight in urdbean (Vigna mungo L.) and their variability on various hosts (Doctoral dissertation, Govind Ballabh Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, India). Krishikosh.

- Negi, H., and Vishunavat, K. (2006). Urdbean leaf crinkle infection in relation to plant age, seed quality, seed transmission and yield in urdbean. Ann. Plant Sci. 14 (1), 169–172.

- Nitzan, N., Chaimovitsh, D., Davidovitch-Rekanati, R., Sharon, M., and Dudai, N. (2012). Rhizoctonia web blight—A new disease on mint in Israel. Plant Disease. 96:370-378.

- Pandey, S., Sharma, M., Kumari, S., Gaur, P. M., Chen, W., Kaur, L., et al. (2009). “Integrated foliar disease management of legumes,” in Grain Legumes: Genetic improvement, Management and Trade. Ed. M. Ali, et al (Kanpur, India: Indian Society of Pulses Research and Development, Indian Institute of Pulses Research), 143–161.

- Parmeter, J. R. (Ed.). (2023). Rhizoctonia solani: Biology and pathology (Original work published 1970). University of California Press. [CrossRef]

- Priyatmojo, A., Sato, Y., Kanematsu, S., & Hyakumachi, M. (2001). Anastomosis grouping and genetic variation of Rhizoctonia solani isolates from leguminous vegetables in Japan. Mycoscience, 42(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, F., Bain, R. and Mcquilken, M. (2013), Survival of Sclerotia of Rhizoctonia solani AG3PT and Effect of Soil-Borne Inoculum Density on Disease Development on Potato. Journal Phytopathology, 161: 180-189. [CrossRef]

- Saksena, H. K., & Dwivedi, R. P. (1973). Web blight of black gram caused by Thanatephorus cucumeris. Indian Journal of Farm Sciences, 1(1), 58–61.

- Sharma, O. P., Bambawale, O. M., Gopali, J. B., Bhagat, S., Yelshetty, S., & Singh, S. K. (2011). Field guide: Mungbean and urdbean. National Centre for Integrated Pest Management.

- Sharon, M., Freeman, S., Kuninaga, S., Sneh, B. & Hyakumachi, M. (2006). Genetic structure of Rhizoctonia solani AG-1 IA populations from Israel, Japan, and the USA. Phytopathology, 96(5), 480–489. [CrossRef]

- Sharon, M., Freeman, S., Kuninaga, S., & Sneh, B. (2007). Genetic diversity, anastomosis groups, and virulence of Rhizoctonia spp. from strawberry. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 117(3), 247–265. [CrossRef]

- Sharon, M., Kuninaga, S., Hyakumachi, M., Naito, S., & Sneh, B. (2008). Classification of Rhizoctonia spp. using rDNA-ITS sequence analysis supports the genetic basis of the classical anastomosis grouping. Mycoscience, 49(2), 93–114. [CrossRef]

- Saksena, H. K., & Dwivedi, R. P. (1973). Web blight of black gram caused by Thanatephorus cucumeris. Indian Journal of Farm Sciences, 1(1), 58–61.

- Shen, C.-m., Zhou, Z.-m., Li, C.-t., Zhao, Z.-f., Luo, L., & Yang, G.-h. (2024). First report of Rhizoctonia solani AG-2-2 IIIB causing rice sheath blight in China. Plant Disease, 108(12), 3650. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. (2006). Rhizoctonia solani in rice-wheat cropping system (PhD thesis). Department of Plant Pathology, G. B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, Uttarakhand, India.

- Spedaletti, Y., Aparicio, M., Cárdenas, G. M., Rodriguero, M., Taboada, G., Aban, C., Sühring, S., Vizgarra, O., & Galván, M. (2016). Genetic characterization and pathogenicity of Rhizoctonia solani associated with common bean web blight in the main bean growing area of Argentina. Journal of Phytopathology, 164(11–12), 1054–1063. [CrossRef]

- Verma, B. (2019). Studies on Rhizoctonia solani (Kühn) causing web blight of urdbean and its management (Master’s thesis, Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India).

- Wang, D., Wu, W., Deng, D., Duan, C., Sun, S., & Zhu, Z. (2025). First report of Rhizoctonia solani causing leaf rot disease on mung bean (Vigna radiata) in China. Plant Disease. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Wigg, K. S., Brainard, S. H., Metz, N., Dorn, K. M., & Goldman, I. L. (2023). Novel QTL associated with Rhizoctonia solani Kühn resistance identified in two table beet × sugar beet F₂:₃ populations using a new table beet reference genome. Crop Science, 63(2), 535–555. [CrossRef]

- Yaduman, R., Singh, S., & Lal, A. A. (2019). Morphological and pathological variability of different isolates of Rhizoctonia solani Kühn causing sheath blight disease of rice. Plant Cell Biotechnology and Molecular Biology, 20(1&2), 73–80.

- Yamamoto, N. et al. (2019). Integrative transcriptome analysis discloses the molecular basis of a heterogeneous fungal phyto-pathogen complex, Rhizoctonia solani AG-1 subgroups. Scientific Reports, 9, 19626. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. G., Zhao, C., Guo, Z. J., & Wu, X. H. (2015). Characterization of a new anastomosis group (AG-W) of binucleate Rhizoctonia, causal agent for potato stem canker. Plant Disease, 99(12), 1757–1763. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. K., Xia, X. Y., Du, Q., Xia, L., Ma, X. Y., Li, Q. Y., & Liu, W. D. (2021). Genome sequence of Rhizoctonia solani Anastomosis Group 4 strains Rhs4ca, a widespread pathomycete in field crops. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 34(7), 826–829. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).