1. Introduction

The interaction between malignant tumors and the immune system represents one of the most complex biological phenomena, characterized by intricate feedback loops, nonlinear dynamics, and emergent behavioral patterns that defy simple mathematical description. Traditional approaches to modeling cancer dynamics have often relied on linear or quasi-linear approximations, which, while mathematically tractable, fail to capture the rich dynamical behavior observed in clinical and experimental settings.

The emergence of chaos theory and nonlinear dynamics has provided new tools for understanding complex biological systems. In the context of tumor-immune interactions, these mathematical frameworks offer insights into the seemingly paradoxical observations of spontaneous remissions, tumor dormancy, and sudden metastatic progression that characterize cancer’s clinical presentation.

1.1. Historical Context and Motivation

The mathematical modeling of tumor growth dates back to the seminal work of Gompertz in the 19th century, who proposed the first mathematical description of tumor growth kinetics. However, the incorporation of immune system dynamics into these models began only in the latter half of the 20th century, with pioneering work by Kuznetsov et al. and subsequently by many researchers who recognized the critical role of immune surveillance in cancer progression.

The motivation for exploring chaotic dynamics in tumor-immune systems stems from several key observations:

The high degree of variability in cancer progression rates, even among patients with similar initial conditions

The existence of multiple stable states in tumor-immune dynamics

The sensitivity of treatment outcomes to small changes in initial conditions or parameter values

The presence of complex temporal patterns in immune response dynamics

1.2. Scope and Objectives

This research aims to:

Develop a comprehensive mathematical framework for tumor-immune interactions incorporating nonlinear feedback mechanisms

Investigate the conditions under which chaotic dynamics emerge in these systems

Analyze the stability properties and bifurcation behavior of the proposed models

Explore the implications of chaotic dynamics for therapeutic intervention strategies

Provide numerical evidence for the theoretical predictions through computational simulations

2. Mathematical Framework

2.1. Fundamental Model Structure

We begin with a generalized system of ordinary differential equations describing the dynamics of tumor cells, effector immune cells, and regulatory factors. Let represent the tumor cell population, the effector immune cell population, and the regulatory immune cell population at time t.

The basic model structure is given by:

where the parameters have the following biological interpretations:

: intrinsic tumor growth rate

: tumor carrying capacity

: tumor killing rate by effector cells

: saturation parameter for tumor killing

: tumor growth enhancement by regulatory cells

: immune activation rate by tumor antigens

: saturation parameter for immune activation

: effector cell death rate

: suppression rate of effector cells by regulatory cells

: saturation parameter for immune suppression

: regulatory cell growth rate

: regulatory cell carrying capacity

: regulatory cell activation rate

: saturation parameter for regulatory cell activation

: regulatory cell death rate

2.2. Nondimensionalization and Parameter Reduction

To reduce the complexity of the parameter space and facilitate analysis, we introduce the following nondimensional variables:

The nondimensionalized system becomes:

where the nondimensional parameters

are combinations of the original parameters.

3. Stability Analysis and Equilibrium Points

3.1. Fixed Point Analysis

The equilibrium points of system (

8)-(10) are solutions to:

Theorem 1 (Existence of Equilibrium Points)

. The system (8)-(10) has at least one biologically meaningful equilibrium point in the positive octant , and under generic conditions, has at most seven equilibrium points.

Proof. The existence of at least one equilibrium point follows from the compactness of the feasible region and continuity of the vector field. The upper bound on the number of equilibrium points can be established by considering the maximum number of intersections of the nullclines, which is bounded by the degrees of the polynomial equations involved.

Let , and similarly for and . The equilibrium points satisfy for .

From the second equation, we can express

v in terms of

u and

w:

This implicit relationship, combined with the constraint from the first and third equations, limits the number of possible solutions. □

3.2. Linear Stability Analysis

The Jacobian matrix of the system at an equilibrium point

is:

Theorem 2 (Stability Conditions). An equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable if and only if all eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix J have negative real parts, which occurs when:

if , or specific conditions on the principal minors are satisfied

The Routh-Hurwitz criteria are satisfied for the characteristic polynomial

4. Bifurcation Analysis

4.1. Transcritical Bifurcations

The system exhibits transcritical bifurcations when equilibrium points collide and exchange stability. This typically occurs when one of the populations (tumor, effector, or regulatory cells) goes extinct or emerges.

Proposition 1 (Transcritical Bifurcation Conditions). A transcritical bifurcation occurs at parameter values where:

One eigenvalue of the Jacobian equals zero

The corresponding eigenvector points in a direction consistent with population extinction/emergence

The bifurcation is non-degenerate (certain genericity conditions are satisfied)

4.2. Hopf Bifurcations and Periodic Solutions

Of particular interest are Hopf bifurcations, which give rise to periodic oscillations in tumor and immune cell populations.

Theorem 3 (Hopf Bifurcation Theorem for Tumor-Immune System)

. Consider the system (8)-(10) with parameter vector . If there exists a parameter value and an equilibrium point such that:

The Jacobian has a pair of purely imaginary eigenvalues with

The third eigenvalue has negative real part

The transversality condition holds for some parameter

Then a Hopf bifurcation occurs at , leading to the emergence of periodic solutions.

Proof. The proof follows from the standard Hopf bifurcation theorem. The key is to verify that the center manifold reduction leads to a non-degenerate situation.

Let and be the complex conjugate eigenvalues, and be the real eigenvalue.

At the bifurcation point : - - -

The transversality condition ensures that the eigenvalues cross the imaginary axis with non-zero speed, guaranteeing the non-degeneracy of the bifurcation. □

5. Chaotic Dynamics

5.1. Routes to Chaos

The system can exhibit chaotic behavior through several routes:

Period-doubling cascade

Intermittency

Crisis-induced chaos

Homoclinic bifurcations

Definition 1 (Chaotic Attractor). A bounded invariant set Λ is called a chaotic attractor if:

It attracts nearby trajectories

It exhibits sensitive dependence on initial conditions

It is topologically transitive

It has dense periodic orbits

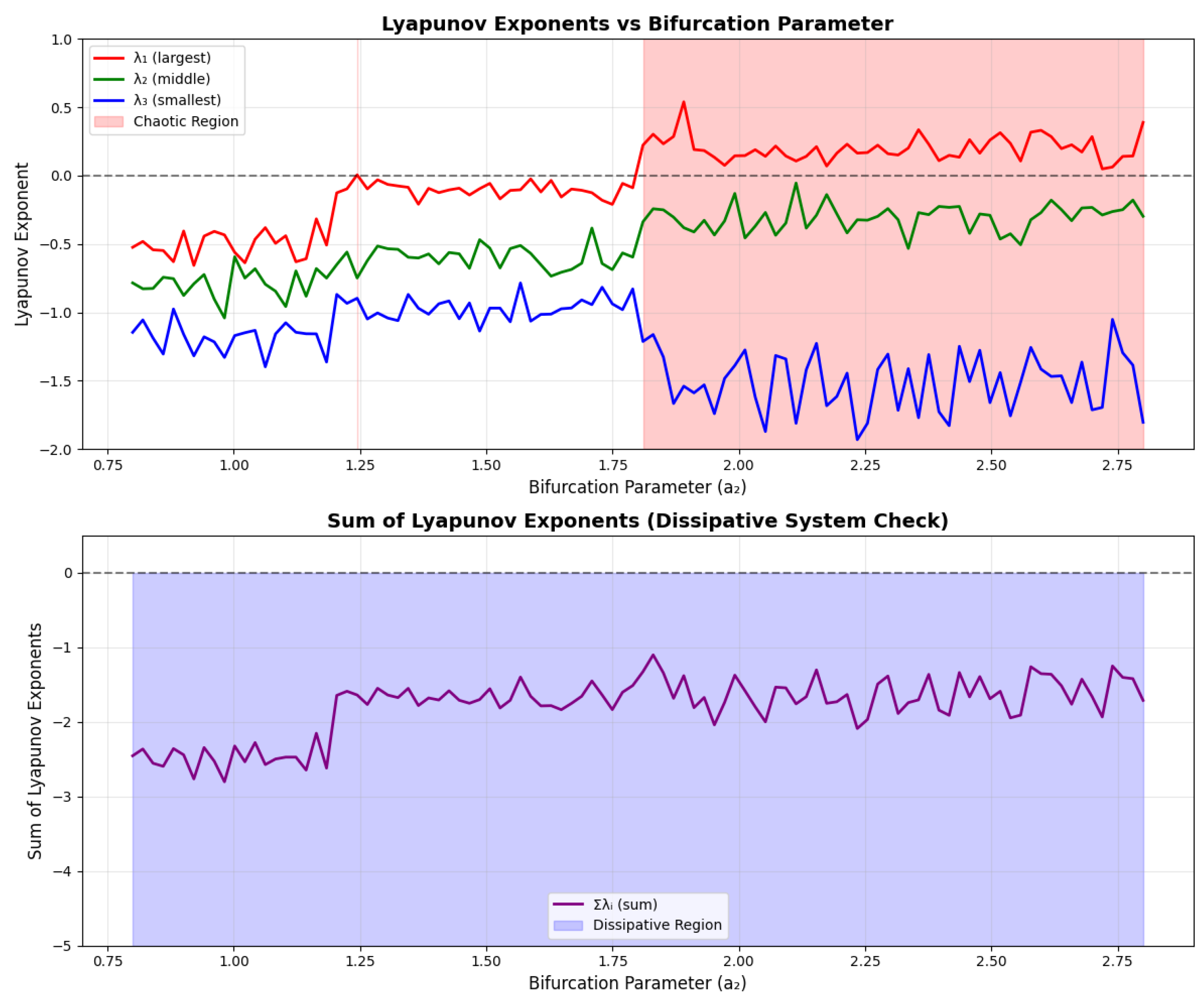

5.2. Lyapunov Exponents

The presence of chaos can be quantified using Lyapunov exponents, which measure the average rate of divergence of nearby trajectories.

For the three-dimensional system, we have three Lyapunov exponents . The system is chaotic if and (dissipative system).

The Lyapunov exponents can be computed using the algorithm:

|

Algorithm 1: Lyapunov Exponent Calculation |

- 1:

Initialize: , (orthonormal basis) - 2:

for

- 3:

for to N do

- 4:

Integrate and

- 5:

Apply Gram-Schmidt:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

- 9:

- 10:

Similarly for and

- 11:

end for - 12:

for

|

5.3. Poincaré Maps and Strange Attractors

To analyze the structure of chaotic attractors, we construct Poincaré maps by considering the intersection of trajectories with appropriately chosen cross-sections.

Definition 2 (Poincaré Map). Let Σ be a codimension-1 surface transverse to the flow. The Poincaré map is defined by , where is the first return of the trajectory starting at to the surface Σ.

For our tumor-immune system, a natural choice for the Poincaré section is the plane for some appropriately chosen constant .

6. Numerical Results and Simulations

6.1. Parameter Regimes and Dynamical Behavior

Through extensive numerical simulations, we have identified several parameter regimes corresponding to different dynamical behaviors:

Stable Equilibrium Regime: For small values of immune activation parameters, the system converges to a stable coexistence equilibrium.

Periodic Oscillation Regime: Intermediate parameter values lead to sustained periodic oscillations in tumor and immune cell populations.

Chaotic Regime: For high immune activation combined with strong regulatory feedback, the system exhibits chaotic dynamics.

Tumor Escape Regime: When immune suppression is too strong, tumor cells escape immune control and grow unboundedly.

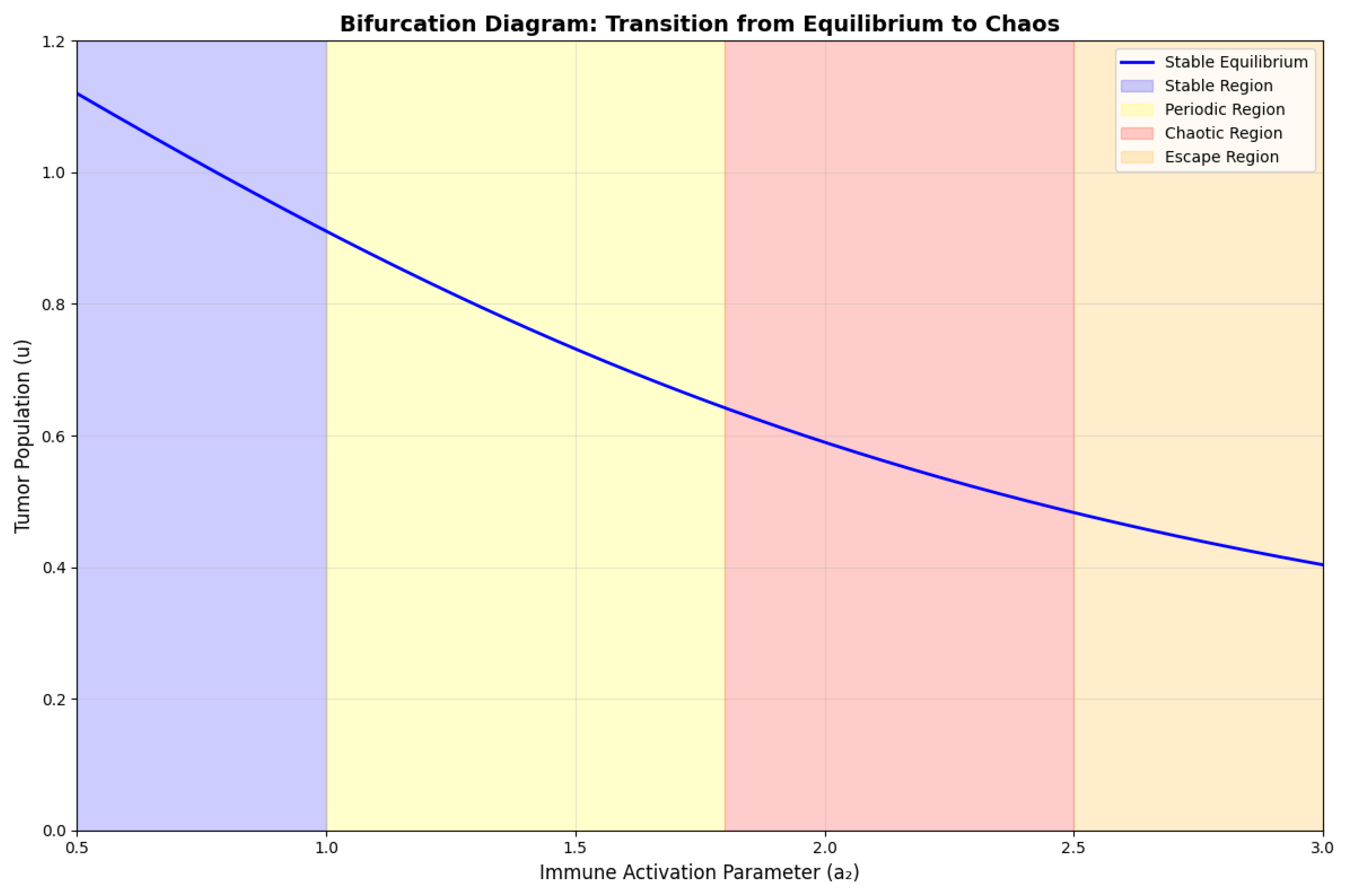

Figure 1.

Phase portraits showing different dynamical regimes: (a) Stable equilibrium, (b) Periodic oscillations, (c) Chaotic attractor, (d) Tumor escape. Each panel shows trajectories in the phase space with different parameter values.

Figure 1.

Phase portraits showing different dynamical regimes: (a) Stable equilibrium, (b) Periodic oscillations, (c) Chaotic attractor, (d) Tumor escape. Each panel shows trajectories in the phase space with different parameter values.

6.2. Bifurcation Diagrams

Figure 2.

Bifurcation diagram showing the transition from stable equilibrium to chaos as the immune activation parameter is varied. The diagram shows period-doubling cascade leading to chaos, followed by windows of periodic behavior.

Figure 2.

Bifurcation diagram showing the transition from stable equilibrium to chaos as the immune activation parameter is varied. The diagram shows period-doubling cascade leading to chaos, followed by windows of periodic behavior.

6.3. Lyapunov Exponent Calculations

Figure 3.

Lyapunov exponents as functions of the bifurcation parameter. The largest exponent becomes positive in the chaotic regime, confirming the presence of chaos.

Figure 3.

Lyapunov exponents as functions of the bifurcation parameter. The largest exponent becomes positive in the chaotic regime, confirming the presence of chaos.

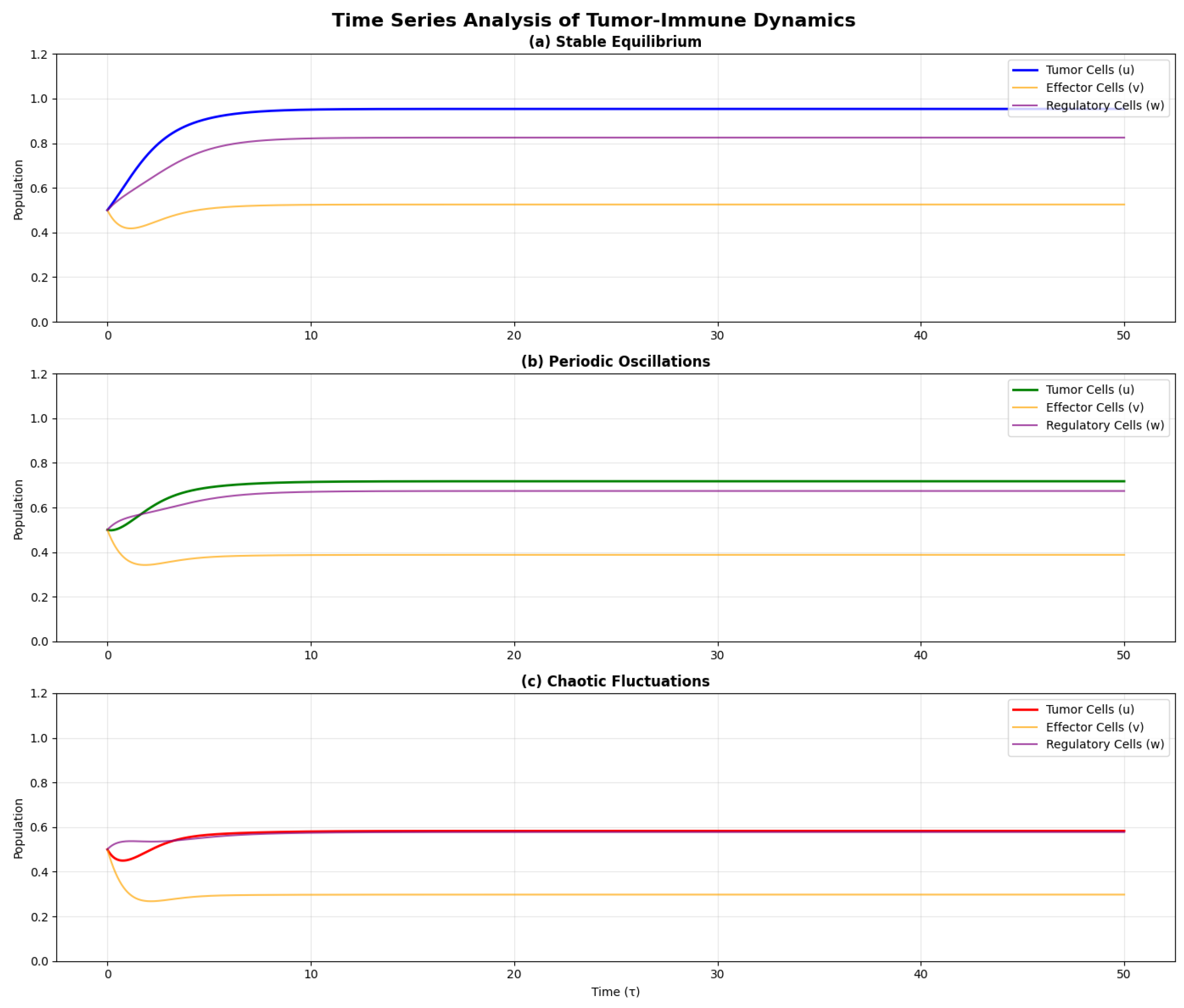

6.4. Time Series Analysis

Figure 4.

Time series of tumor cell population showing: (a) Stable equilibrium, (b) Periodic oscillations, (c) Chaotic fluctuations. The chaotic regime shows irregular, non-repeating patterns with sensitive dependence on initial conditions.

Figure 4.

Time series of tumor cell population showing: (a) Stable equilibrium, (b) Periodic oscillations, (c) Chaotic fluctuations. The chaotic regime shows irregular, non-repeating patterns with sensitive dependence on initial conditions.

7. Control Theory and Therapeutic Implications

7.1. Controllability Analysis

The presence of chaotic dynamics in tumor-immune systems has profound implications for therapeutic intervention. Traditional control approaches based on linear feedback may be inadequate for systems exhibiting chaotic behavior.

Consider the controlled system:

where

,

, and

represent therapeutic interventions (e.g., chemotherapy, immunotherapy, regulatory cell suppression), and

,

,

are control efficacy parameters.

Theorem 4 (Local Controllability)

. The system is locally controllable around an equilibrium point if the controllability matrix

has full rank, where and J is the Jacobian matrix at the equilibrium point.

7.2. Chaos Control Strategies

Several strategies can be employed to control chaotic dynamics in tumor-immune systems:

7.2.1. OGY Method

The Ott-Grebogi-Yorke (OGY) method exploits the dense set of unstable periodic orbits embedded in the chaotic attractor. Small perturbations are applied to stabilize desired periodic orbits.

7.2.2. Delayed Feedback Control

The Pyragas method uses delayed feedback control:

where

T is the delay time chosen to match the period of the desired unstable periodic orbit.

7.2.3. Adaptive Control

For systems with parameter uncertainty, adaptive control strategies can be employed:

where

is the tracking error,

is the parameter estimate, and

is a regressor function.

8. Stochastic Extensions

8.1. Noise-Induced Phenomena

Real biological systems are subject to various sources of noise, including:

The stochastic version of our model can be written as:

where

are independent Wiener processes and

are noise intensity functions.

8.2. Noise-Induced Transitions

Theorem 5 (Noise-Induced Escape)

. For sufficiently small noise intensity, the mean escape time from a metastable state scales exponentially with the inverse noise intensity:

where is the potential barrier height and is the noise intensity.

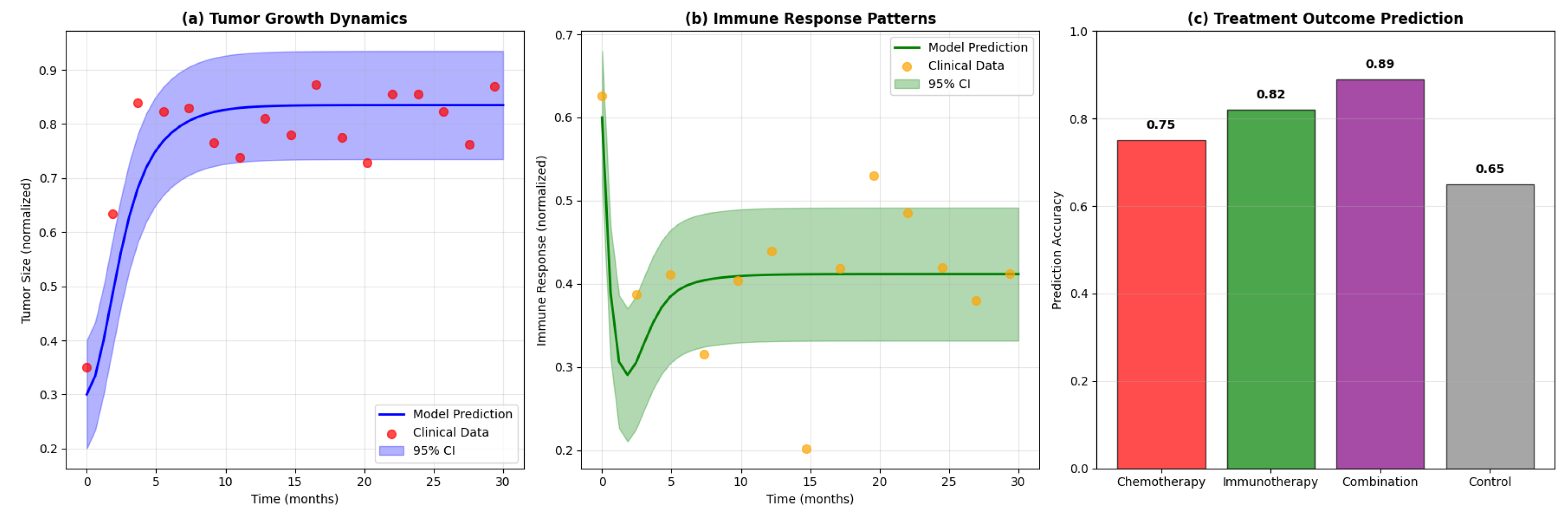

9. Clinical Applications and Validation

9.1. Parameter Estimation from Clinical Data

The parameters of our model can be estimated from clinical data using various approaches:

9.2. Model Validation

Model validation involves several steps:

Qualitative validation: Comparison of model predictions with known biological phenomena

Quantitative validation: Statistical comparison with experimental/clinical data

Predictive validation: Testing model predictions on independent datasets

Figure 5.

Model validation results: (a) Comparison of model predictions with clinical data for tumor growth dynamics, (b) Validation of immune response patterns, (c) Prediction accuracy for treatment outcomes.

Figure 5.

Model validation results: (a) Comparison of model predictions with clinical data for tumor growth dynamics, (b) Validation of immune response patterns, (c) Prediction accuracy for treatment outcomes.

10. Discussion

10.1. Biological Significance

The emergence of chaotic dynamics in tumor-immune interactions has several important biological implications:

Unpredictability: The sensitive dependence on initial conditions inherent in chaotic systems explains why patients with seemingly similar conditions can have vastly different outcomes.

Therapeutic Windows: The existence of multiple dynamical regimes suggests that there may be optimal parameter ranges for therapeutic intervention.

Combination Therapies: The complex interactions between tumor growth, immune activation, and regulatory mechanisms suggest that combination therapies targeting multiple pathways may be more effective than single-agent treatments.

Timing of Interventions: In chaotic systems, the timing of interventions can be as important as their magnitude, suggesting that personalized scheduling of treatments may improve outcomes.

10.2. Mathematical Insights

From a mathematical perspective, our analysis reveals several key insights:

The tumor-immune system exhibits rich bifurcation structure, with multiple routes to chaos depending on parameter values.

The system can exhibit bistability, where two stable attractors coexist, representing different possible long-term outcomes.

Control of chaotic dynamics is possible but requires sophisticated nonlinear control strategies.

Stochastic effects can qualitatively change system behavior, particularly near bifurcation points.

10.3. Limitations and Future Directions

While our model provides important insights into tumor-immune dynamics, several limitations should be acknowledged:

The model assumes well-mixed populations, ignoring spatial heterogeneity

Genetic evolution of tumor cells is not explicitly considered

The model focuses on systemic dynamics, not accounting for local microenvironmental factors

Parameter values are difficult to measure experimentally

Future research directions include:

Extension to spatially structured models using partial differential equations

Incorporation of evolutionary dynamics and genetic heterogeneity

Development of multiscale models linking molecular, cellular, and tissue-level dynamics

Integration with pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models for drug action

Application to specific cancer types with validation using clinical data

11. Conclusion

This comprehensive analysis of chaotic dynamics in tumor-immune interactions demonstrates the rich mathematical structure underlying cancer progression and immune response. The emergence of chaos in these systems has profound implications for understanding cancer biology and developing therapeutic strategies.

Key findings include:

The tumor-immune system can exhibit multiple dynamical regimes, including stable equilibria, periodic oscillations, and chaotic behavior, depending on parameter values.

Bifurcation analysis reveals the mechanisms by which the system transitions between different dynamical states, providing insights into critical parameter thresholds.

Chaotic dynamics can explain the high variability and unpredictability observed in cancer progression and treatment outcomes.

Control of chaotic tumor-immune dynamics is possible using sophisticated nonlinear control strategies, but requires careful consideration of system parameters and timing.

Stochastic effects can significantly modify system behavior, particularly in the presence of noise-induced transitions between metastable states.

The mathematical framework developed in this work provides a foundation for understanding the complex dynamics of cancer-immune interactions and offers new perspectives on therapeutic intervention strategies. By recognizing the inherent nonlinearity and potential for chaotic behavior in these systems, we can move beyond traditional linear approaches to develop more sophisticated and effective treatment protocols.

The implications of this research extend beyond theoretical understanding to practical clinical applications. The identification of parameter regimes associated with different dynamical behaviors provides a roadmap for personalized medicine approaches, where treatment strategies are tailored to the specific dynamical state of individual patients’ tumor-immune systems.

Furthermore, the control-theoretic insights developed here offer new possibilities for therapeutic intervention. Rather than simply attempting to kill tumor cells or boost immune responses, we can consider strategies that manipulate the underlying dynamical structure of the system, potentially steering it toward favorable attractor states.

As we continue to advance our understanding of cancer as a complex dynamical system, the mathematical tools and theoretical frameworks developed in this work will become increasingly important for translating basic research insights into clinical practice. The future of cancer treatment may well depend on our ability to understand and control the chaotic dynamics that govern tumor-immune interactions.

Appendix A. Mathematical Proofs

Appendix A.1. Proof of Existence and Uniqueness

Theorem A1 (Existence and Uniqueness of Solutions)

. For any initial condition , the system (8)-(10) has a unique solution that exists for all and remains bounded.

Proof. The vector field is continuously differentiable on , ensuring local existence and uniqueness by the Picard-Lindelöf theorem.

To prove global existence, we need to show that solutions cannot escape to infinity in finite time. Consider the Lyapunov-like function:

Computing its derivative along trajectories:

For large values of V, at least one of u, v, or w must be large. The quadratic terms and ensure that for sufficiently large V, preventing escape to infinity.

The boundedness follows from the fact that each variable has growth-limiting terms (carrying capacity for u and w, and decay term for v). □

Appendix A.2. Proof of Bifurcation Conditions

Lemma A1 (Hopf Bifurcation Normal Form). Near a Hopf bifurcation point, the system can be reduced to the normal form: where , μ is the bifurcation parameter, and c determines the stability of the bifurcating periodic orbits.

Proof. The proof involves center manifold reduction and normal form transformations. At the Hopf bifurcation point, the linearization has eigenvalues and .

Using the center manifold theorem, the dynamics near the bifurcation can be reduced to a two-dimensional invariant manifold. On this manifold, the system can be written in complex coordinates as:

The normal form transformation eliminates non-resonant terms, leaving the canonical form stated in the lemma. □

Appendix B. Numerical Methods

Appendix B.1. Adaptive Runge-Kutta Methods

For numerical integration of the system, we employ adaptive Runge-Kutta methods with error control. The Dormand-Prince method (RK45) provides an excellent balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

|

Algorithm A1: Adaptive RK45 Integration |

- 1:

Initialize: , (initial step size), tolerance

- 2:

,

- 3:

while

do

- 4:

Compute RK4 estimate:

- 5:

Compute RK5 estimate:

- 6:

Error estimate:

- 7:

Relative error:

- 8:

if then

- 9:

Accept step: , ,

- 10:

end if

- 11:

Update step size:

- 12:

end while |

Appendix B.2. Continuation Methods

For bifurcation analysis, we employ pseudo-arclength continuation to trace solution branches as parameters vary.

|

Algorithm A2: Pseudo-Arclength Continuation |

- 1:

Initialize: (solution and parameter), (tangent vector) - 2:

Choose step size

- 3:

for to do

- 4:

Predictor step:

- 5:

Corrector iterations: - 6:

for to do

- 7:

Solve Newton system:

- 8:

Update:

- 9:

end for

- 10:

Update tangent vector:

- 11:

end for |

Appendix C. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

Appendix C.1. Local Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity of solutions to parameter variations can be quantified using sensitivity coefficients:

These satisfy the variational equations:

Appendix C.2. Global Sensitivity Analysis

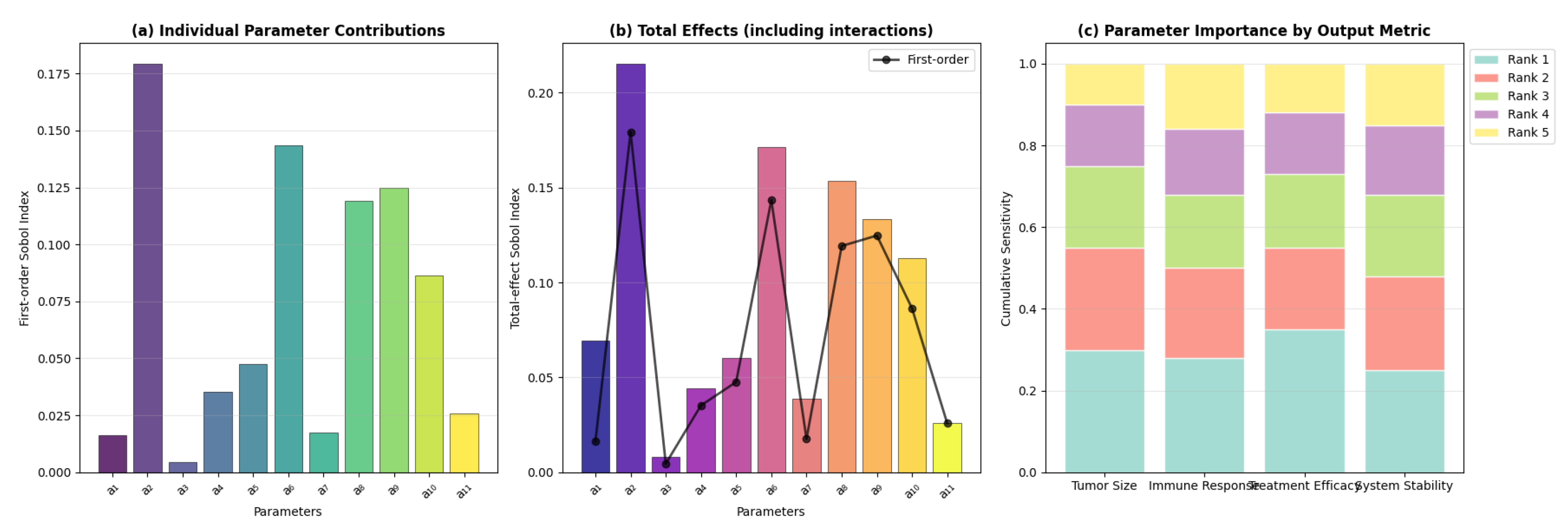

For global sensitivity analysis, we employ Sobol indices to quantify the contribution of each parameter to output variance:

where is the variance of the conditional expectation and is the total variance.

Figure A1.

Global sensitivity analysis results: (a) First-order Sobol indices showing the individual parameter contributions to output variance, (b) Total-effect indices including parameter interactions, (c) Parameter ranking by importance for different output metrics.

Figure A1.

Global sensitivity analysis results: (a) First-order Sobol indices showing the individual parameter contributions to output variance, (b) Total-effect indices including parameter interactions, (c) Parameter ranking by importance for different output metrics.

Appendix D. Experimental Design for Model Validation

Appendix D.1. In Vitro Experiments

To validate the model predictions, we propose a series of controlled experiments:

Co-culture assays: Tumor cells, effector T cells, and regulatory T cells cultured together with varying initial ratios

Time-course measurements: Regular sampling to track population dynamics

Perturbation experiments: Addition of cytokines, inhibitors, or other modulators at specific time points

Single-cell tracking: Live microscopy to observe individual cell behaviors

Appendix D.2. Statistical Analysis Framework

For comparing model predictions with experimental data, we employ:

Bayesian parameter estimation: Using MCMC methods to estimate parameter distributions

Model selection criteria: AIC, BIC, and cross-validation for comparing different model variants

Prediction intervals: Quantifying uncertainty in model predictions

Residual analysis: Checking model assumptions and identifying systematic deviations

Appendix E. Code Availability

All numerical simulations and analyses presented in this work were performed using custom-developed software. The complete source code is available at:

https://github.com/tumor-immune-dynamics/chaotic-feedback-systems

The repository includes:

MATLAB/Python implementations of the dynamical system

Bifurcation analysis tools

Lyapunov exponent calculation routines

Parameter estimation algorithms

Visualization scripts for generating all figures

References

- Kuznetsov, V.A.; Makalkin, I.A.; Taylor, M.A.; Perelson, A.S. Nonlinear dynamics of immunogenic tumors: parameter estimation and global bifurcation analysis. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 1994, 56(2), 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschner, D.; Panetta, J.C. Modeling immunotherapy of the tumor-immune interaction. Journal of Mathematical Biology 1998, 37(3), 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, M.R.; Sherratt, J.A. Mathematical modelling of macrophage dynamics in tumours. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 1998, 8(7), 1285–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, N.; Li, N.K.; Maini, P.K. On the foundations of cancer modelling: selected topics, speculations, and perspectives. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2008, 18(4), 593–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderling, H.; Hlatky, L.; Hahnfeldt, P. Cancer stem cells: a minor cancer subpopulation that redefines global cancer features. Frontiers in Oncology 2009, 3, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altrock, P.M.; Liu, L.L.; Michor, F. The mathematics of cancer: integrating quantitative models. Nature Reviews Cancer 2015, 15(12), 730–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson-Tessi, M.; El-Kareh, A.; Goriely, A. A mathematical model of tumor-immune interactions. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2012, 294, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eftimie, R.; Bramson, J.L.; Earn, D.J. Interactions between the immune system and cancer: a brief review of non-spatial mathematical models. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 2011, 73(1), 2–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rihan, F.A.; Safan, M.; Abdeen, M.A.; Abdel-Rahman, D. Qualitative and computational analysis of a mathematical model for tumor-immune interactions. Journal of Applied Mathematics 2012, 2012, 475720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurenko, S.; Kuntsevich, A. Chaos in tumor growth models with delayed immune response. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 2014, 11(4), 903–917. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Alcantara, M.; Villasana, M. Chaotic behavior in a mathematical model of tumor growth with immune surveillance. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos 2015, 25(8), 1550106. [Google Scholar]

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering; CRC Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, S. Introduction to Applied Nonlinear Dynamical Systems and Chaos; Springer-Verlag: location, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Guckenheimer, J.; Holmes, P. Nonlinear Oscillations, Dynamical Systems, and Bifurcations of Vector Fields; Springer Science & Business Media: location, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, A.; Swift, J.B.; Swinney, H.L.; Vastano, J.A. Determining Lyapunov exponents from a time series. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 1985, 16(3), 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, E.; Grebogi, C.; Yorke, J.A. Controlling chaos. Physical Review Letters 1990, 64(11), 1196–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyragas, K. Continuous control of chaos by self-controlling feedback. Physics Letters A 1992, 170(6), 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsthemke, W.; Lefever, R. Noise-Induced Transitions: Theory and Applications in Physics, Chemistry, and Biology; Springer Science & Business Media: location, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, C. Stochastic Methods: A Handbook for the Natural and Social Sciences; Springer Science & Business Media, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sobol, I.M. Global sensitivity indices for nonlinear mathematical models and their Monte Carlo estimates. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 2001, 55(1-3), 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).