Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

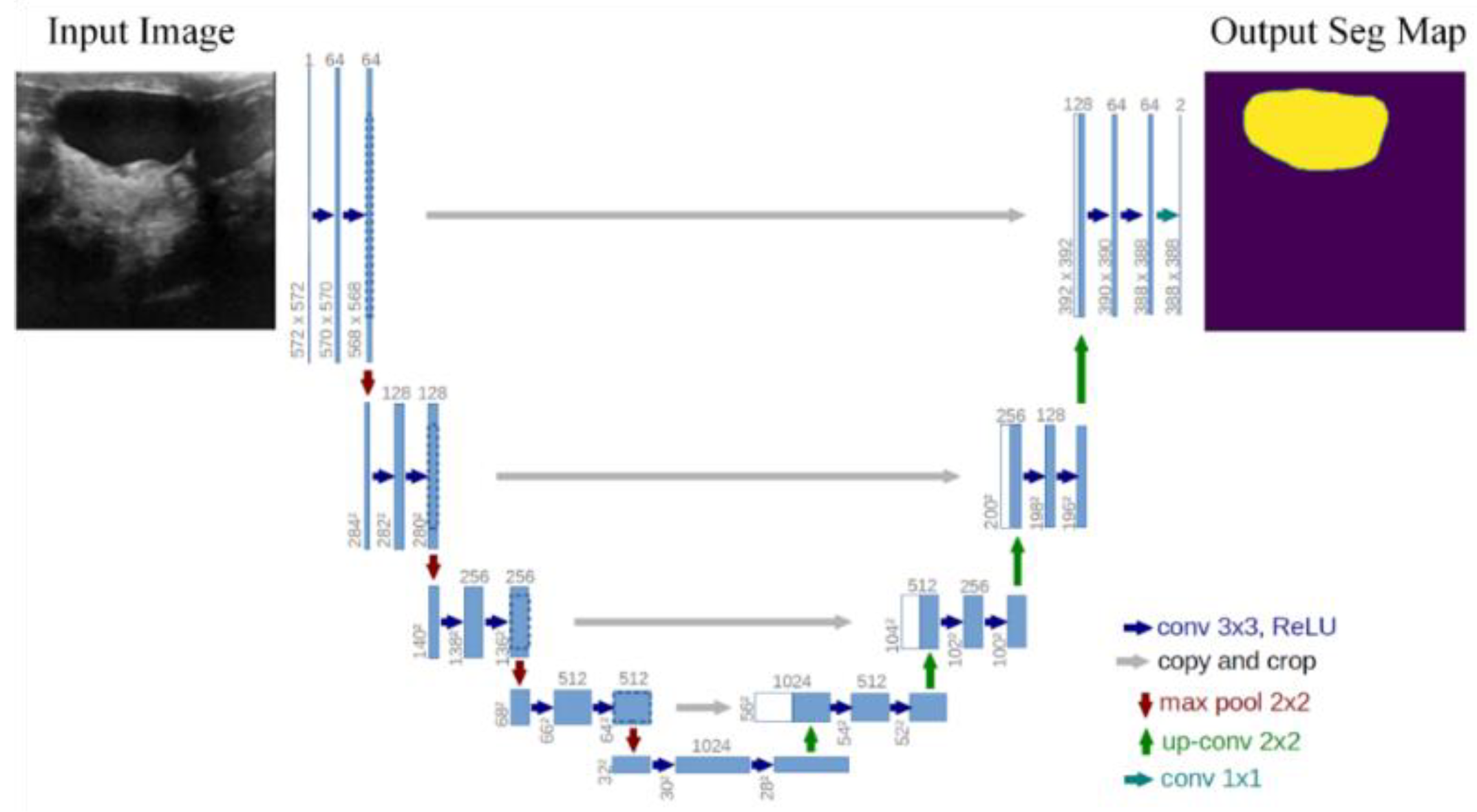

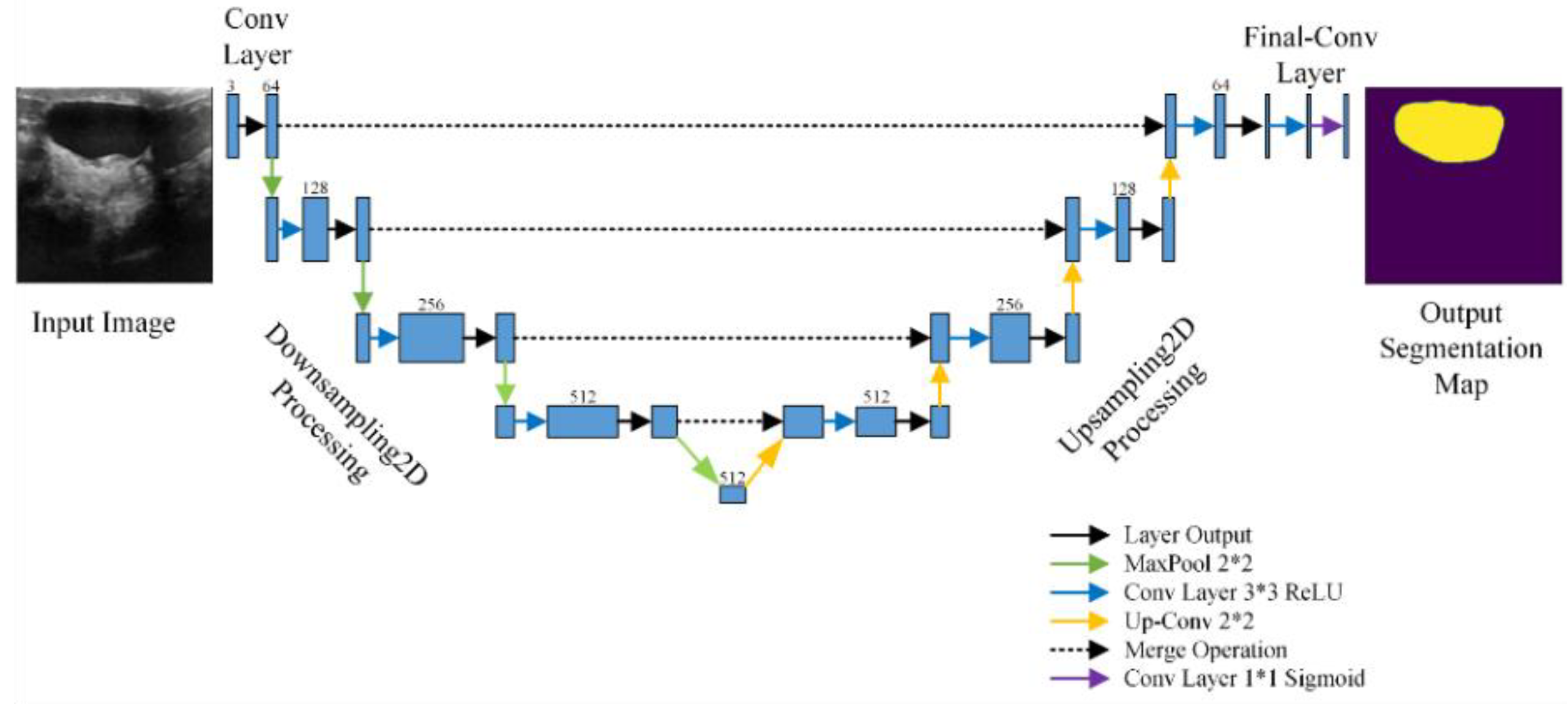

- Based on the transfer learning (TL) method, the FgFEU-Net model is proposed for breast tumor segmentation. The model adopts U-Net model as the backbone network, Vgg16 as the pre-training model for fine-grained feature extraction, and adopts combined loss as a loss function.

- (2)

- To solve the imbalance between input and output in organ images, the combination loss is employed in the experiments. The performance of the model with TC loss, dice coefficient, and binary cross loss are compared with lots of experiments, respectively.

- (3)

- The model performance is compared with SVM, CNN, VGG16, VGG19, and U-Net in the same dataset. Experimental results indicate that the proposed model obtained the best segmentation performance.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. Proposed Approach

3.2. Loss Function

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

4. Experiments and Analysis

4.1. Dataset Description

4.2. Experimental Procedures

4.3. Experimental Environment

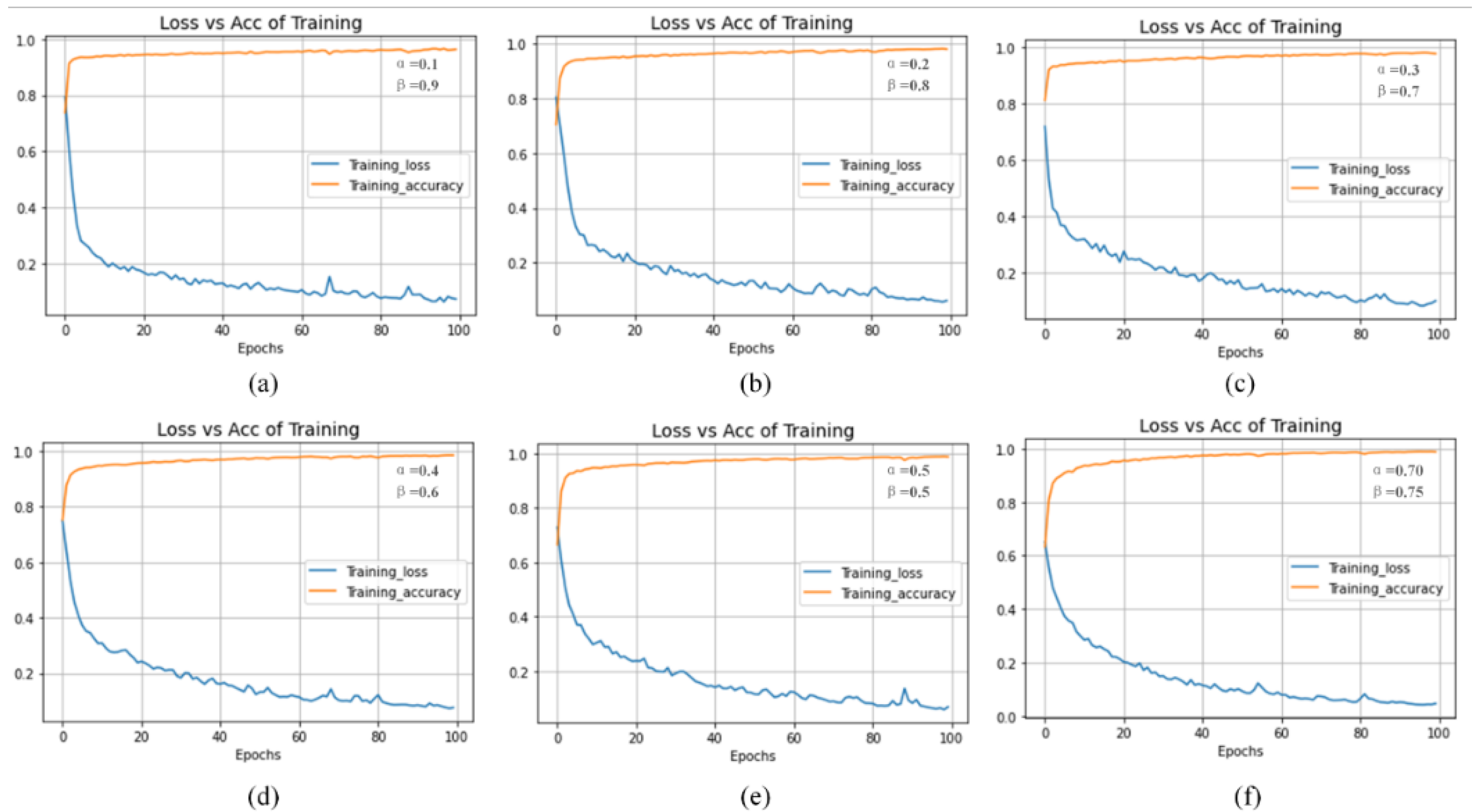

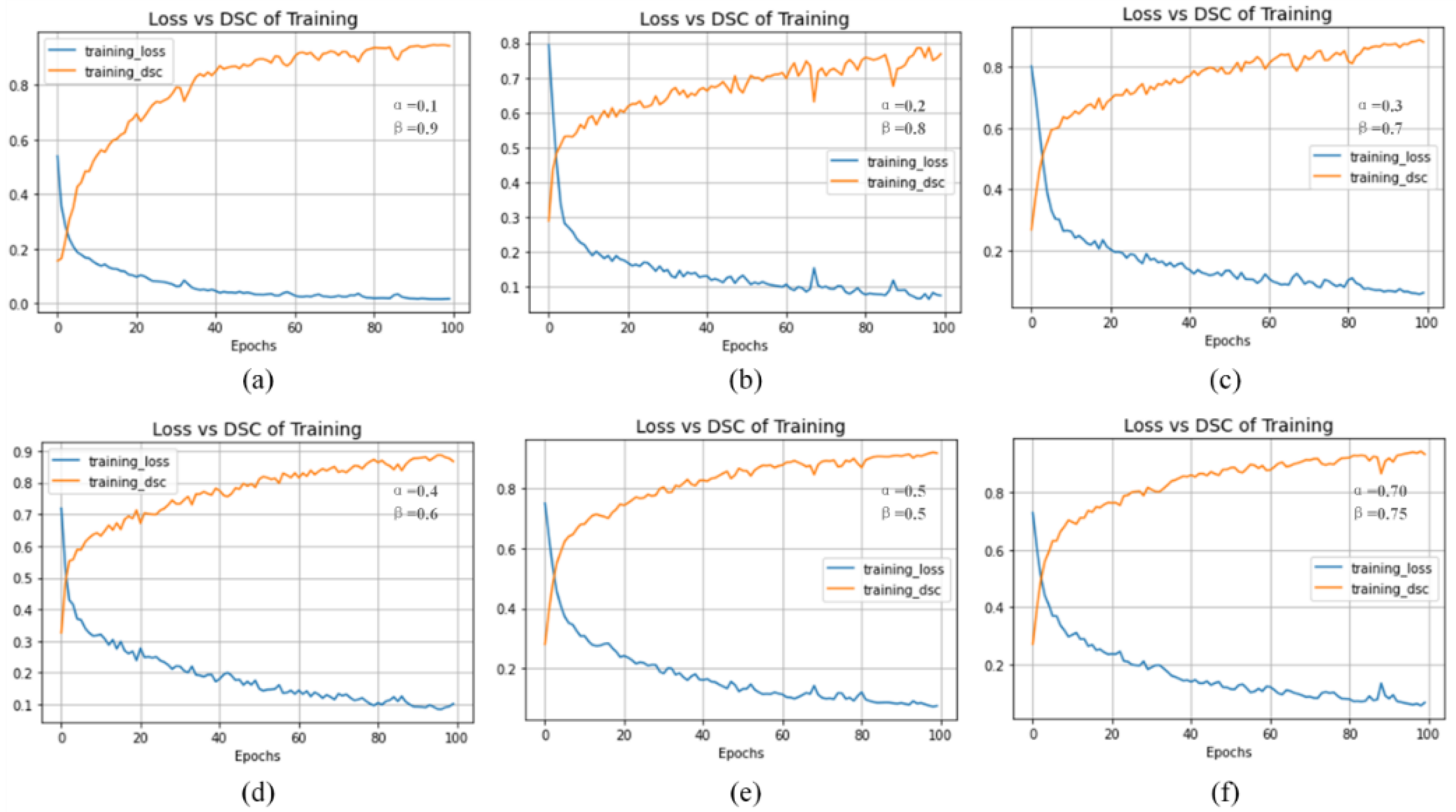

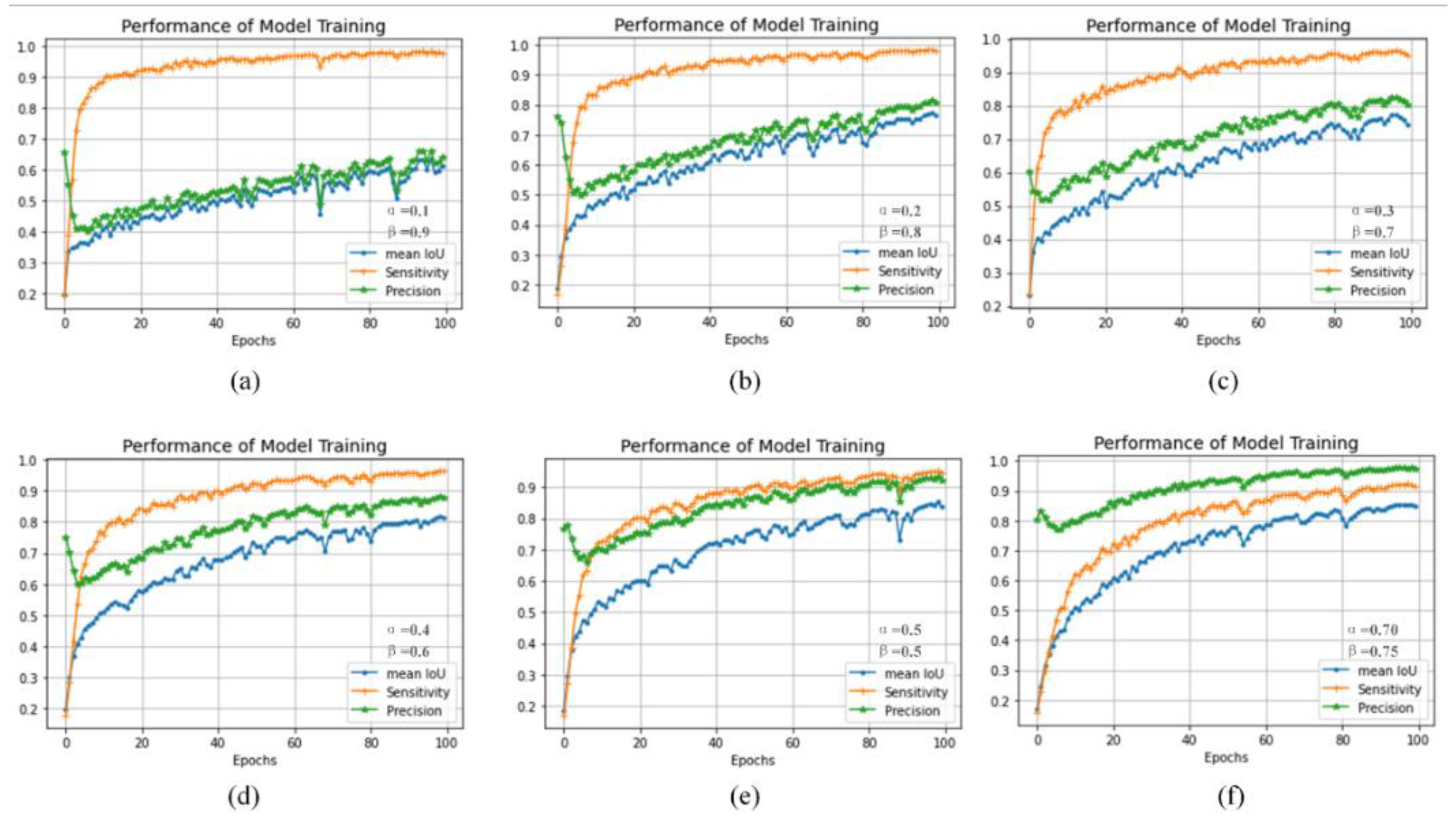

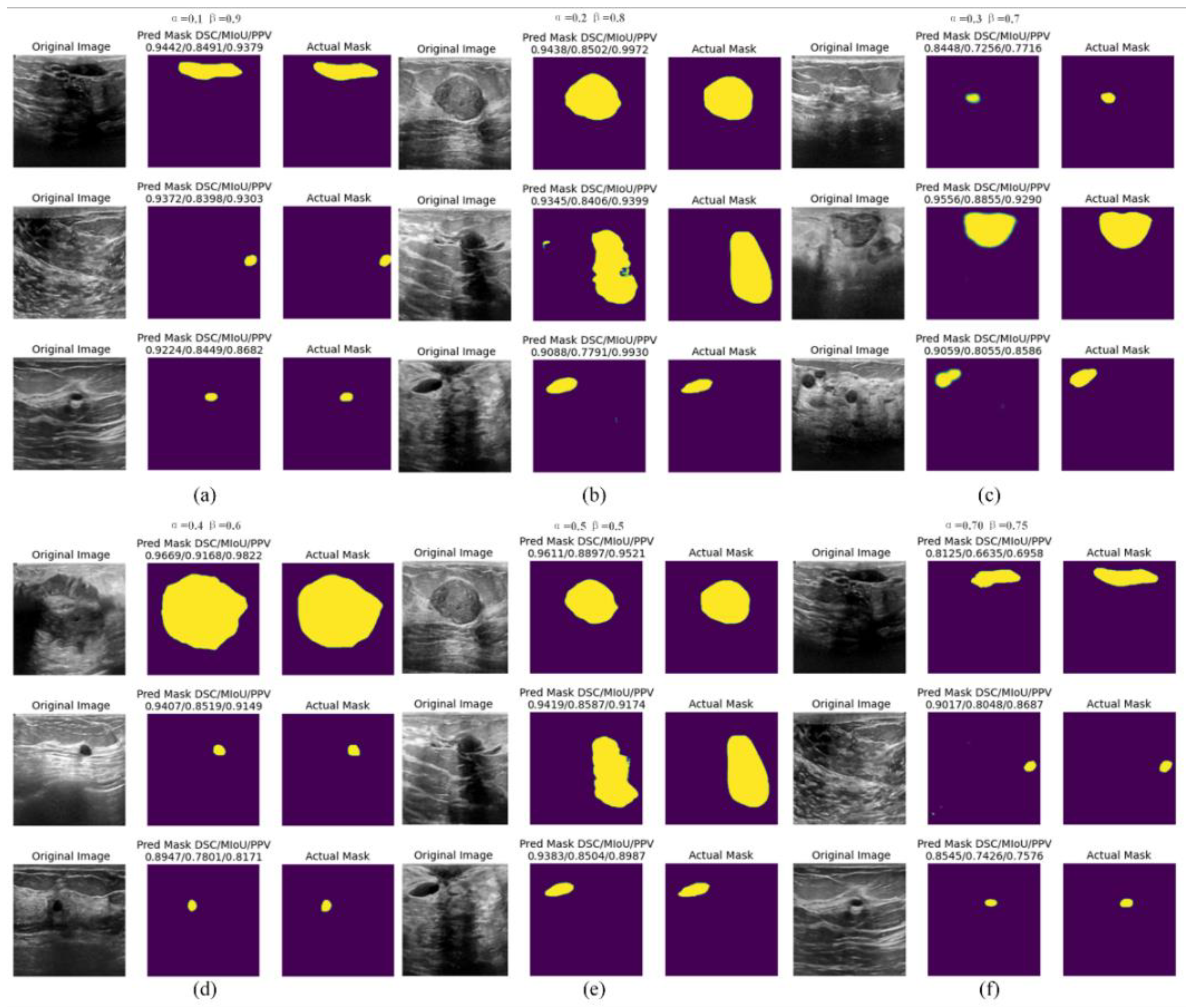

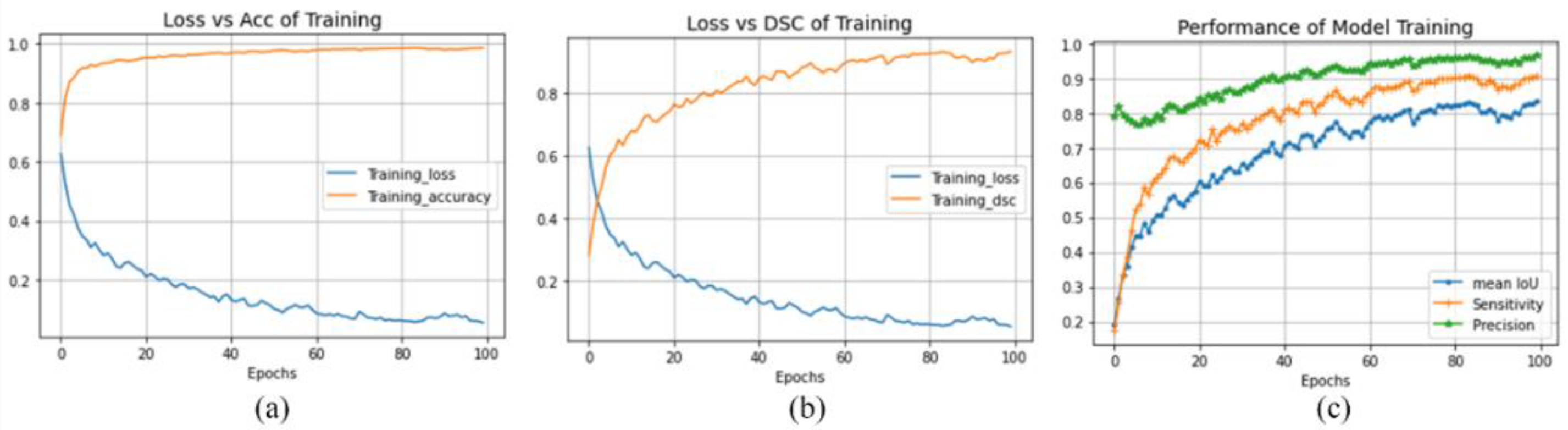

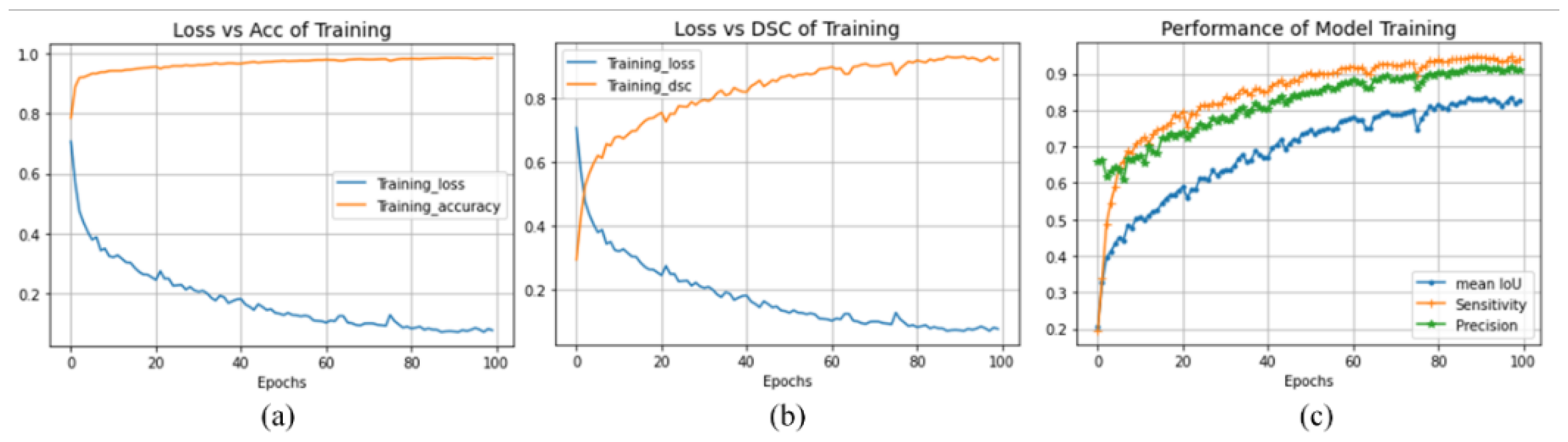

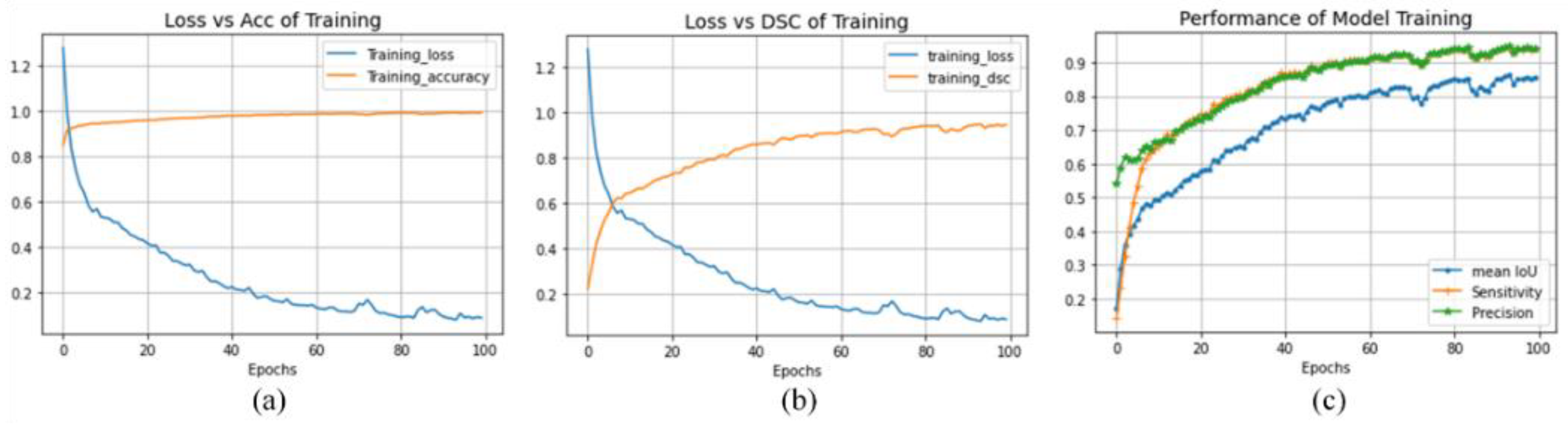

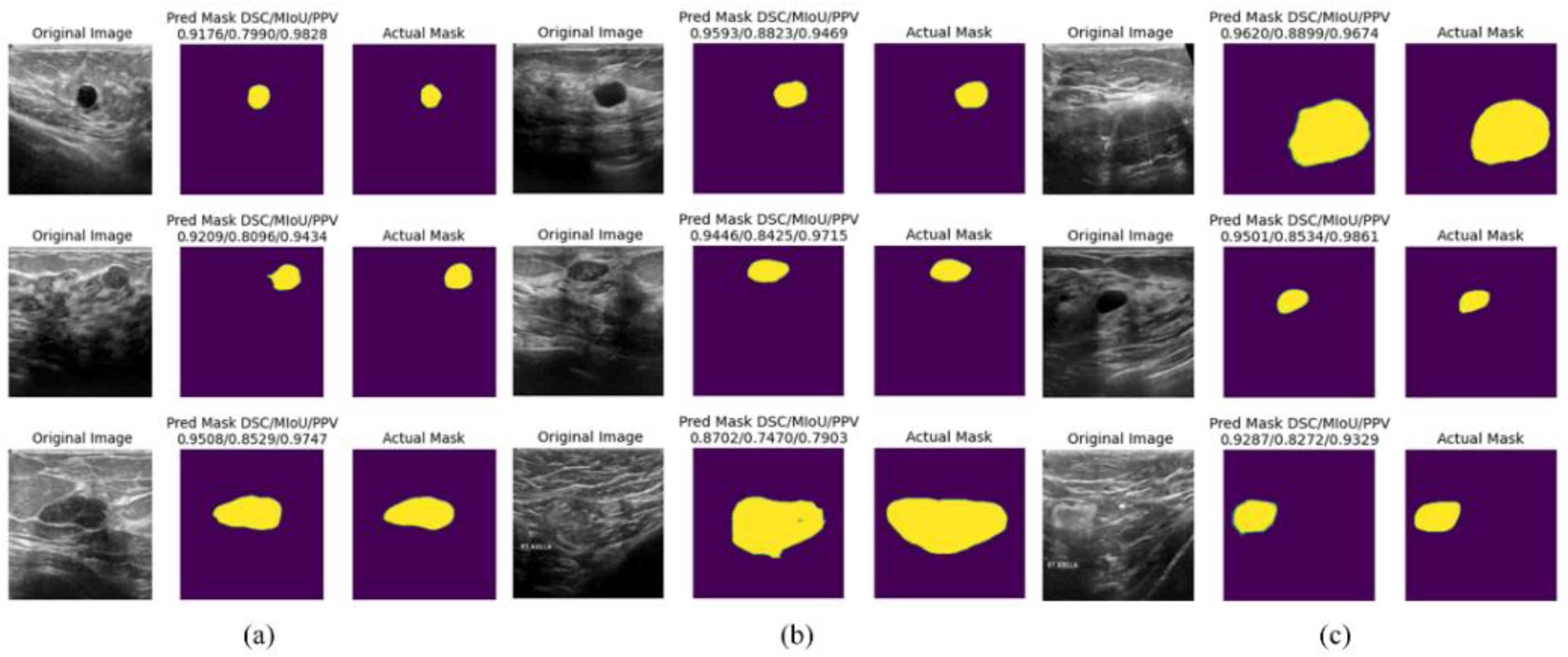

4.4. Experiment Result

4.5. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Guotai Wang, Wenqi Li, Maria A. Zuluaga, Rosalind Pratt, Premal A. Patel, Michael Aertsen, Tom Doel, Anna L. David, Jan Deprest, S’ebastien Ourselin, and Tom Vercauteren. Interactive medical image segmentation using deep learning with image-specific fine tuning. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 37(7):1562–1573, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ran Gu, GuotaiWang, Tao Song, Rui Huang, Michael Aertsen, Jan Deprest, S’ebastien Ourselin, Tom Vercauteren, and Shaoting Zhang. Ca-net: Comprehensive attention convolutional neural networks for explainable medical image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 40(2):699–711, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Annegreet Van Opbroek, M. Arfan Ikram, MeikeW. Vernooij, and Marleen de Bruijne. Transfer learning improves supervised image segmentation across imaging protocols. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 34(5):1018–1030, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Annegreet Van Opbroek, Hakim C. Achterberg, Meike W. Vernooij, and Marleen De Bruijne. Transfer learning for image segmentation by combining image weighting and kernel learning. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 38(1):213–224,2019. [CrossRef]

- Chien-Ming Lin, Chi-Yi Tsai, Yu-Cheng Lai, Shin-An Li, and Ching-Chang Wong. Visual object recognition and pose estimation based on a deep semantic segmentation network. IEEE Sensors Journal, 18(22):9370–9381, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya Varma and Omkar Sawant. An alternative approach to detect breast cancer using digital image processing techniques. In 2018 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), pages 0134–0137, 2018.

- Etienne von Lavante and J. Alison Noble. Segmentation of breast cancer masses in ultrasound using radio-frequency signal derived parameters and strain estimates. In 2008 5th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro, pages 536–539, 2008.

- N Kavya, N Usha, N. Sriraam, D Sharath, and Prabha Ravi. Breast cancer detection using non invasive imaging and cyber physical system. In 2018 3rd International Conference on Circuits, Control, Communication and Computing (I4C), pages 1–4, 2018.

- Albert Gubern-M’erida, Michiel Kallenberg, Ritse M. Mann, Robert Mart’ı, and Nico Karssemeijer. Breast segmentation and density estimation in breast mri: A fully automatic framework. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 19(1):349–357, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Haeyun Lee, Jinhyoung Park, and Jae Youn Hwang. Channel attention module with multiscale grid average pooling for breast cancer segmentation in an ultrasound image. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 67(7):1344–1353, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Meena Prakash, K. Bhuvaneshwari, M. Divya, K. Jamuna Sri, and A. Sulaiha Begum. Segmentation of thermal infrared breast images using k-means, fcm and em algorithms for breast cancer detection. In 2017 International Conference on Innovations in Information, Embedded and Communication Systems (ICIIECS), pages 1–4, 2017.

- Muhammed Emin Bagdigen and Gokhan Bilgin. Cell segmentation in triple-negative breast cancer histopathological images using u-net architecture. In 2020 28th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), pages 1–4, 2020.

- Constance Fourcade, Ludovic Ferrer, Gianmarco Santini, No’emie Moreau, Caroline Rousseau, Marie Lacombe, Camille Guillerminet, Mathilde Colombi’e, Mario Campone, Diana Mateus, and Mathieu Rubeaux. Combining superpixels and deep learning approaches to segment active organs in metastatic breast cancer pet images. In 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), pages 1536–1539, 2020.

- Than Than Htay and Su Su Maung. Early stage breast cancer detection system using glcm feature extraction and k-nearest neighbor (k-nn) on mammography image. In 2018 18th International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies (ISCIT), pages 171–175, 2018.

- Khaleel Al-Rababah, Shyamala Doraisamy, Mas Rina, and Fatimah Khalid. A color-based high temperature extraction method in breast thermogram to classify cancerous and healthy cases using svm. In 2018 2nd International Conference on Imaging, Signal Processing and Communication (ICISPC), pages 70–73, 2018.

- R. D. Ghongade and D. G.Wakde. Computer-aided diagnosis system for breast cancer using rf classifier. In 2017 International Conference on Wireless Communications, Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), pages 1068–1072, 2017.

- Xiaowei Xu, Ling Fu, Yizhi Chen, Rasmus Larsson, Dandan Zhang, Shiteng Suo, Jia Hua, and Jun Zhao. Breast region segmentation being convolutional neural network in dynamic contrast enhanced mri. 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), pages 750–753, 2018.

- Meriem Sebai, Tianjiang Wang, and Saad Ali Al-Fadhli. Partmitosis: A partially supervised deep learning framework for mitosis detection in breast cancer histopathology images. IEEE Access, 8:45133–45147, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Walid S. Al-Dhabyani, Mohammed Mohammed Mohammed Gomaa, H Khaled, and Aly A. Fahmy. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data in Brief, 28, 2019.

- Kaiwen Lu, Tianran Lin, Junzhou Xue, Jie Shang, and Chao Ni. An automated bearing fault diagnosis using a self-normalizing convolutional neural network. In 2019 International Conference on Quality, Reliability, Risk, Maintenance, and Safety Engineering (QR2MSE), pages 908–912, 2019.

- Zhen Huang, Tim Ng, Leo Liu, Henry Mason, Xiaodan Zhuang, and Daben Liu. Sndcnn: Self-normalizing deep cnns with scaled exponential linear units for speech recognition. In ICASSP 2020 - 2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pages 6854–6858, 2020.

- Ngoc-Son Vu, Vu-Lam Nguyen, and Philippe-Henri Gosselin. A handcrafted normalized-convolution network for texture classification. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), pages 1238–1245, 2017.

- Olaf Ronneberger, Philipp Fischer, and Thomas Brox. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (cs.CV), ArXiv, abs/1505.04597, 2015.

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (cs.CV), abs/1409.1556, 2014.

- Guotai Wang, Maria A. Zuluaga, Wenqi Li, Rosalind Pratt, Premal A. Patel, Michael Aertsen, Tom Doel, Anna L. David, Jan Deprest, S’ebastien Ourselin, and Tom Vercauteren. Deepigeos: A deep interactive geodesic framework for medical image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 41(7):1559–1572, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Laura Raquel Bareiro Paniagua, Jos’e Luis V’azquez Noguera, Luis Salgueiro Romero, Deysi Natalia Leguizamon Correa, Diego P. Pinto-Roa, Julio C’esar Mello-Rom’an, Sebastian A. Grillo, Miguel Garc’ıa-Torres, Lizza A. Salgueiro Toledo, and Jacques Facon. Impact of melanocytic lesion image databases on the pre-training of segmentation tasks using the unet architecture.In 2021 XXIII Symposium on Image, Signal Processing and Artificial Vision (STSIVA), pages 1–6, 2021.

- Carole H Sudre, Wenqi Li, Tom Vercauteren, Sebastien Ourselin, and M Jorge Cardoso. Generalised dice overlap as a deep learning loss function for highly unbalanced segmentations. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support: Third International Workshop, DLMIA 2017, and 7th International Workshop, MLCDS 2017, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2017, Qu’ebec City, QC, Canada, September 14, Proceedings 3, pages 240–248. Springer, 2017.

- Loic Themyr, Cl’ement Rambour, Nicolas Thome, Toby Collins, and Alexandre Hostettler. Full contextual attention for multiresolution transformers in semantic segmentation. 2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), pages 3223–3232, 2022.

- Yichi Zhang, Zhenrong Shen, Rushi Jiao. Segment anything model for medical image segmentation: Current applications and future directions. Computers in Biology and Medicine, Vol.171, pages 108238, 2024.

- Jiménez-Gaona, Y.; Rodríguez-Álvarez, M.J.; Lakshminarayanan, V. Deep-Learning-Based Computer-Aided Systems for Breast Cancer Imaging: A Critical Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8298. [CrossRef]

- Tianqi Yang, Oktay Karakus, Nantheera Anantrasirichai, and Alin Achim. Current advances in computational lung ultrasound imaging: A review. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 70:2–15, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Stafford Michahial and Bindu A. Thomas. A novel algorithm for locating region of interest in breast ultra sound images. 2017 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer, and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT), pages 1–5, 2017.

- Yonghao Huang and Qinghua Huang. A superpixel-classification-based method for breast ultrasound images. 2018 5th International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI), pages 560–564, 2018.

- Zhao Yu-qian, Gui Wei-hua, Chen Zhen-cheng, Tang Jing-tian, and Li Ling-yun. Medical images edge detection based on mathematical morphology. 2005 IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 27th Annual Conference, pages 6492–6495, 2005.

- M. Lalonde, M. Beaulieu, and L. Gagnon. Fast and robust optic disc detection using pyramidal decomposition and hausdorffbased template matching. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 20(11):1193–1200, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Wenan Chen, Rebecca Smith, Soo-Yeon Ji, Kevin RWard, and Kayvan Najarian. Automated ventricular systems segmentation in brain ct images by combining low-level segmentation and high-level template matching. BMC medical informatics and decision making, 9 Suppl 1:S4, November 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Tsai, A. Yezzi, W. Wells, C. Tempany, D. Tucker, A. Fan, W.E. Grimson, and A. Willsky. A shape-based approach to the segmentation of medical imagery using level sets. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 22(2):137–154, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Changyang Li, XiuyingWang, Stefan Eberl, Michael Fulham, Yong Yin, Jinhu Chen, and David Dagan Feng. A likelihood and local constraint level set model for liver tumor segmentation from ct volumes. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 60(10):2967–2977, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, T. Fevens, and Adam Krzy˙zak. A svm-based framework for autonomous volumetric medical image segmentation using hierarchical and coupled level sets. In Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery - International Congress and Exhibition, 2004.

- Saeid Asgari Taghanaki, Yefeng Zheng, Shaohua Kevin Zhou, Bogdan Georgescu, Puneet S. Sharma, Daguang Xu, Dorin Comaniciu, and G. Hamarneh. Combo loss: Handling input and output imbalance in multi-organ segmentation. Computerized medical imaging and graphics : the official journal of the Computerized Medical Imaging Society, 75:24–33, 2018.

- Xiaoya Li, Xiaofei Sun, Yuxian Meng, Junjun Liang, Fei Wu, and Jiwei Li. Dice loss for data-imbalanced NLP tasks. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 465–476, Online, Jul 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Yaoshiang Ho and Samuel Wookey. The real-world-weight cross-entropy loss function: Modeling the costs of mislabeling. IEEE Access, 8:4806–4813, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sheetal Janthakal and Girisha Hosalli. A binary cross entropy u-net based lesion segmentation of granular parakeratosis. In 2021 International Conference on Advancements in Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computing and Automation (ICAECA), pages 1–7, 2021.

- Haonan Wang, Peng Cao, Jiaqi Wang, and Osmar R Zaiane. Uctransnet: Rethinking the skip connections in u-net from a channel-wise perspective with transformer. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fenglin Liu, Xuancheng Ren, Zhiyuan Zhang, Xu Sun, and Yuexian Zou. Rethinking skip connection with layer normalization in transformers and resnets. Machine Learning (cs.LG), ArXiv, abs/2105.07205, 2021.

- Kaiming He, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pages 770–778, 2016.

- Fabian Isensee, Paul F. Jager, Simon A. A. Kohl, Jens Petersen, and Klaus Maier-Hein. Automated design of deep learning methods for biomedical image segmentation. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (cs.CV), arXiv: Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019.

- Seyed Sadegh Mohseni Salehi, Deniz Erdo˘gmus¸, and Ali Gholipour. Tversky Loss Function for Image Segmentation Using 3D Fully Convolutional Deep Networks. In: Wang, Q., Shi, Y., Suk, HI., Suzuki, K. (eds) Machine Learning in Medical Imaging. MLMI 2017. vol 10541, 2017.

- Michael Yeung, Evis Sala, Carola-Bibiane Sch¨onlieb, and Leonardo Rundo. Unified focal loss: Generalising dice and cross entropy-based losses to handle class imbalanced medical image segmentation. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 95, 2021.

- Liangliang Liu, Jianhong Cheng, Quan Quan, Fang-Xiang Wu, Yu-Ping Wang, and Jianxin Wang. A survey on u-shaped networks in medical image segmentations. Neurocomputing, 409:244–258, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jo Schlemper, Ozan Oktay, Michiel Schaap, Mattias P. Heinrich, Bernhard Kainz, Ben Glocker, and Daniel Rueckert. Attention gated networks: Learning to leverage salient regions in medical images. Medical image analysis, 53:197 – 207, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Fausto Milletari, Nassir Navab, and Seyed-Ahmad Ahmadi. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), pages 565–571, 2016.

- Hoel Kervadec, Jihene Bouchtiba, Christian Desrosiers, Eric Granger, Jos’e Dolz, and Ismail Ben Ayed. Boundary loss for highly unbalanced segmentation. Medical image analysis, 67:101851, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Antonio Galli, Stefano Marrone, Gabriele Piantadosi, Mario Sansone, and Carlo Sansone. A pipelined tracer-aware approach for lesion segmentation in breast dce-mri. Journal of Imaging, 7(12), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kaiwen Yang, Aiga Suzuki, Jiaxing Ye, Hirokazu Nosato, Ayumi Izumori, and Hidenori Sakanashi. Ctg-net: Cross-task guided network for breast ultrasound diagnosis. PloS one, 17(8):e0271106, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bendeg’uz H Zov’athi, R’eka Moh’acsi, Attila Marcell Sz’asz, and Gy¨orgy Cserey. Breast tumor tissue segmentation with areabased annotation using convolutional neural network. Diagnostics, 12(9):2161, 2022.

- Xianjun Fu, Hao Cao, Hexuan Hu, Bobo Lian, Yansong Wang, Qian Huang, and Yirui Wu. Attention-based active learning framework for segmentation of breast cancer in mammograms. Applied Sciences, 13(2):852, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Anu Singha and Mrinal Kanti Bhowmik. Alexsegnet: an accurate nuclei segmentation deep learning model in microscopic images for diagnosis of cancer. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 82(13):20431–20452, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Anusua Basu, Pradip Senapati, Mainak Deb, Rebika Rai, and Krishna Gopal Dhal. A survey on recent trends in deep learning for nucleus segmentation from histopathology images. Evolving Systems, pages 1–46, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xuejian Li, Shiqiang Ma, Junhai Xu, Jijun Tang, Shengfeng He, Fei Guo. TranSiam: Aggregating multi-modal visual features with locality for medical image segmentation. Expert Systems with Applications, vol.237, pages 121574, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yongjian Wu, Xiaoming Xi, Xianjing Meng, Xiushan Nie, Yanwei Ren, Guang Zhang, Cuihuan Tian, and Yilong Yin. Label-distribution learning-embedded active contour model for breast tumor segmentation. IEEE Access, 7:97857–97864, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kexin Ding, Mu Zhou, HeWang, Olivier Gevaert, Dimitris Metaxas, and Shaoting Zhang. A large-scale synthetic pathological dataset for deep learning-enabled segmentation of breast cancer. Scientific Data, 10(1):231, 2023. [CrossRef]

| Loss Function | Model Prediction Evaluation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penalty Coefficient | ||||

| TC Loss | α | β | Loss | Accuracy |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0602 | 0.9876 | |

| 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.0746 | 0.9848 | |

| 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.0988 | 0.9777 | |

| 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.0549 | 0.9801 | |

| 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.0956 | 0.9612 | |

| 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.0537 | 0.9866 | |

| BCE Loss | 0.0161 | 0.9916 | ||

| Dice Loss | 0.0874 | 0.9836 | ||

| Combo Loss | 0.0750 | 0.9903 | ||

| Loss Function | Model Prediction Evaluation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penalty Coefficient | ||||||

| TC Loss | α | β | DSC | MIOU | Sensitivity | Precision |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9400 | 0.8456 | 0.9436 | 0.9368 | |

| 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9160 | 0.8163 | 0.9692 | 0.8702 | |

| 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.9015 | 0.7414 | 0.9435 | 0.8194 | |

| 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.8903 | 0.7742 | 0.9863 | 0.8119 | |

| 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.7635 | 0.5993 | 0.9496 | 0.6398 | |

| 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.9356 | 0.8346 | 0.9097 | 0.9632 | |

| BCE Loss | 0.9501 | 0.8654 | 0.9690 | 0.9222 | ||

| Dice Loss | 0.9138 | 0.8083 | 0.9556 | 0.8773 | ||

| Combo Loss | 0.9802 | 0.8645 | 0.9935 | 0.9683 | ||

| Model | Loss | Accuracy | F1 | ROC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Test | Training | Test | |||

| SVM | 0.1325 | 0.1589 | 0.9832 | 0.9829 | 0.9829 | 0.9876 |

| CNN | 0.4088 | 0.5516 | 0.7474 | 0.7924 | 0.7862 | 0.9016 |

| VGG16 | 0.4363 | 0.7057 | 0.9017 | 0.7350 | 0.7322 | 0.8645 |

| VGG16_Enhanced | 0.0315 | 0.0751 | 0.9866 | 0.9573 | 0.9567 | 0.9819 |

| VGG19 | 0.7640 | 0.5889 | 0.9480 | 0.7607 | 0.7571 | 0.8937 |

| VGG19_Enhanced | 0.1016 | 0.1519 | 0.9866 | 0.9573 | 0.9576 | 0.9879 |

| LSTM | 0.2457 | 0.8186 | 0.8859 | 0.7761 | 0.6855 | 0.6838 |

| Bi-LSTM | 0.1105 | 0.7648 | 0.9732 | 0.8034 | 0.7999 | 0.8034 |

| ResNet50 | 0.1574 | 0.2764 | 0.9782 | 0.9573 | 0.9570 | 0.9903 |

| DenseNet121 | 0.1774 | 0.2392 | 0.9285 | 0.9159 | 0.9126 | 0.9215 |

| U-Net | 0.0756 | 0.1985 | 0.9861 | 0.9656 | 0.9602 | 0.9762 |

| FgFEU-Net (Ours) | 0.0161 | 0.0874 | 0.9916 | 0.9836 | 0.9815 | 0.9906 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).