Equation (

46) prescribes the scale flow of the metric (in the Newtonian approximation), given the a set,

, of worldlines associated with matter lumps. To determine this set, an equation for each

, given

, is obtained in this section. This is done by analyzing the scale flow of the first moment of

associated with a general matter lump, using (

21). An obstacle to doing so comes from the fact that,

now incorporates both gravitation and electromagnetic interactions in a convoluted way, as the existence of gravitating matter depends on it being composed of charged matter. In order to isolate the effect of gravity on

, we first analyze the motion of a body in the absence of gravity, i.e.,

,

with

the Minkowskian coordinates. To this end we first need to better understand the scale flow (

21) of

. Using (

24) and (

19) plus some algebra the scaling piece in (

21) reads

with

The first two terms in (

47) are the familiar

conversion, to which a ‘matter vector’,

, is added, consisting of inhomogeneous terms, and the homogeneous,

term, modifying naive scaling in a way which conserves-in-scale charge for a time-independent

In the absence of gravity, the swapping of

and

leading to the l.h.s. of (

21) is fully justified. Combined, we then get

Since

, taking the divergence of (

50) implies

, viz., a conserved-in-time ‘matter charge’. Defining

the (conserved in time-) electric charge, and integrating (

50) over three-space implies

i.e., electric charge is conserved in scale if and only if the matter charge vanishes. That the latter is identically true follows from

where the vanishing of the second integral follows, after integration by parts, from the explicit form (

48) of

With said integral ignored, (

52) becomes (

14). And as proved in that case, solutions for

must all be straight, non tachyonic worldlines. The effect of gravity on those is derived by including a weak field in the the flow of the first-moment projection of (

21). Since gravity is assumed to play a negligible role in the structure of matter, the way this field enters the flat spacetime analysis is via the scaling field,

, with

incorporating the metric, and by ‘dotting the commas’ in partial derivatives. Before analyzing the first moment we note that, the previous zeroth-moment analysis can be repeated with

, at most introducing curvature-terms corrections due to the non-commutativity of covariant derivatives (

20), which can be neglected in the Newtonian approximation. As for the the swapping of

and

made in arriving at (

50), using

(viz., ordinary derivatives can replace covariant ones) in the definition (

19) of

, it is easily established that the swapping introduces an error equal to

with the determinant

. This error is negligible when competing with

, containing extra spatial derivatives of

at its center. Thus

is not only covariantly conserved in time, which can be written

, by virtue of the last identity in (

19), but also in scale,

Continuing in the Newtonian approximation of the metric (

39) for simplicity, and further assuming non-relativistic motion, i.e.,

(say, in the

sense), a straightforward calculation of the Christoffel symbols to first order in

incorporating

gives

Ignoring

corrections to the isotropic coarsener, the net effect of of the potential in the Newtonian approximation is to render the coarsener unisotropic through its gradient. Multiplying (

50) with the modified d’Alembertian (

54) by

and integrating over

B, the

cancels (to first order in

) the

factor multiplying the spatial piece in (

54), which is then integrated by parts, assuming

is approximately constant over the extent of the body. Since

and

the modification to the scaling piece (

47) only introduces an

correction to the

term in (

52) which is neglected in the Newtonian approximation. Further neglecting the

contribution to the double time-derivative piece, the first moment projection of (

21) finally reads

This equation is just (

14) with an extra ‘force-term’ on its r.h.s. which could salvage a non uniformly moving solution,

, from the catastrophic fate at

suffered by its linear counterpart.

At sufficiently large scales,

, when all relevant masses contributing to

occupy a small ball of radius

centered at the origin of scaling without loss of generality, the scaling part on the r.h.s of (

55) becomes negligible compared with the force term, rather benefiting from such crowdedness (

can similarly be assumed without loss of generality). It follows that each

would grow—extremely rapidly as we show next—with increasing

even when the weak-field approximation is still valid, implying that the underlying

is not in

. The only way to keep the scale evolution of

under control is for the acceleration term to similarly grow,

almost canceling the force term but not quite, which is critically important; it is the fact that the sum of these two terms, both originating from the coarsener, remains on the order of the scaling term, which is responsible for a nontrivial, non pure scaling

. This means that each worldline converges at large scales to that satisfying Newton’s equation

At small scales the opposite is true. The scaling part dominates and any

scaling path, i.e.,

is well behaved. Combined: at large scales

is determined, then simply scaled at small scales, gradually converging locally to a freely moving particle. Finally, (

56) must be true also for a loosely bound system, e.g. a wide binary moving in a strong external field, implying that Newton’s law applies also to their relative vector, not merely to their c.o.m.

In conclusion of this section we wish to relate (

57) to the fact that

is not covariantly conserved by virtue of (

27). It was well known already to Einstein that the geodesic equation follows from local energy-momentum conservation under reasonable assumptions. Similarly, the Lorentz force equation follows quite generally from the basic tenets of classical electrodynamics (

30),(

29),(

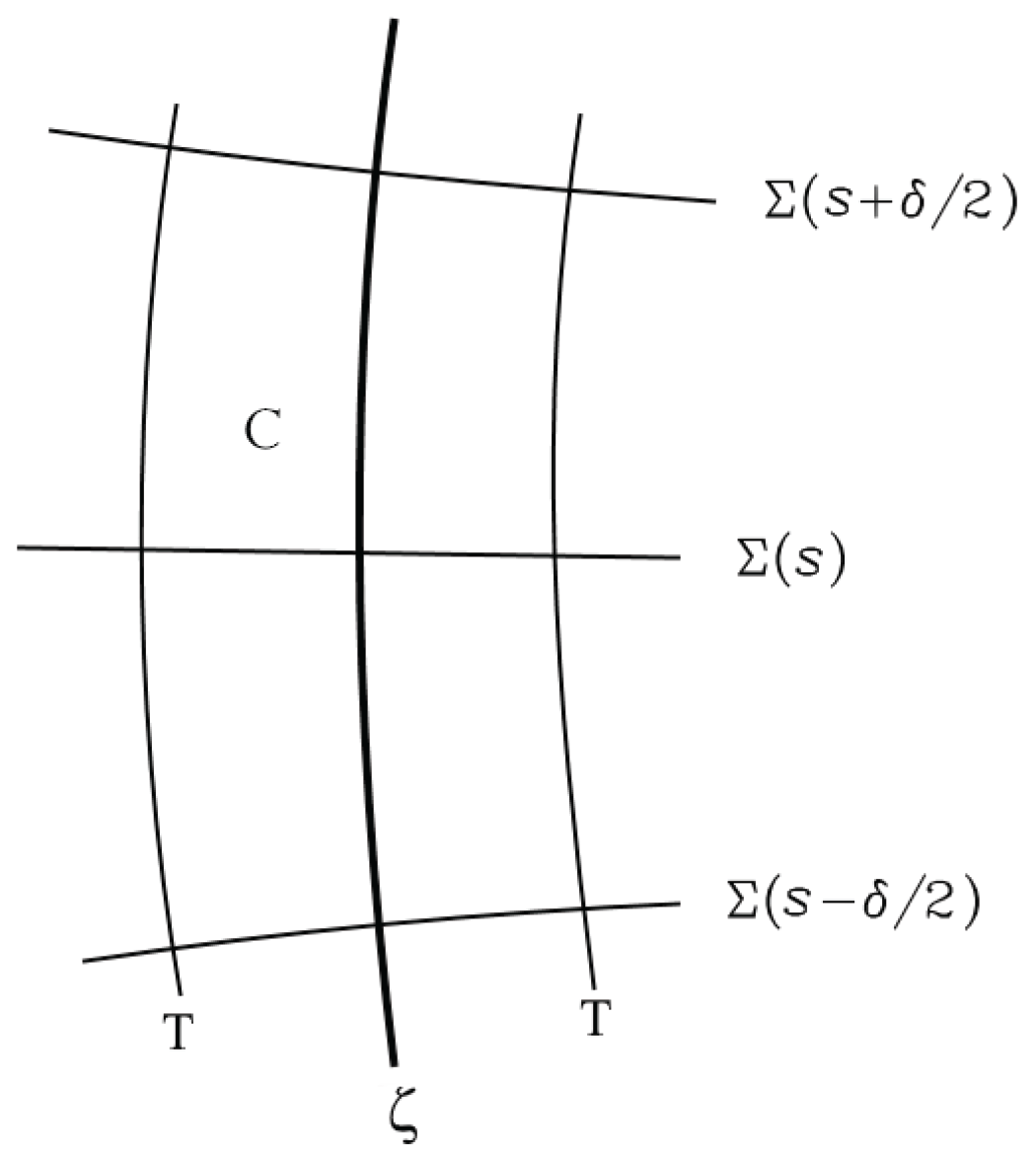

19). Referring to

fig.1, both results are derived by integrating

over a world-cylinder,

C, with the

term obtained by converting part of the volume integral into a surface integral over the

’s via (a relativistic generalization of-) Stoke’s theorem, leaving the remaining part for the ‘force term’, which gives

in the case of gravity. The integral over

T represents small radiative corrections to the geodesic/Lorentz-force equation which can be ignored in what follows. A crucial point in that derivation is that the result is insensitive to the form of

C so long as the

’s contain the support of the particle’s energy-momentum distribution. This insensitivity would not carry to the r.h.s. of (

27) should it be transferred sides, whether or not

is to include the self-field of the particle. Thus attempting to generalize the geodesic equation based on (

27) in the hope that it would reproduce fixed-

solutions of (

57) is bound to fail. Nonetheless, since the conservation-violating r.h.s. of (

27) is a tiny

, it can consistently be ignored for any reasonable choice of

C whenever the individual terms in the geodesic equation are much larger, i.e., at large scales; it is only at small scales that each term becomes comparable to the r.h.s. even for reasonable choices of

C. And since in the limit

paths become simple geodesics at any scale according to (

57), the two length parameters,

,

are not independent, constrained by consistency of solutions such as the above, and likely additional ones involving the structure of matter, as hinted to by the fixed-point example in

sect.3.1.2.

3.2.1. Application: The Rotation Curve of Disc Galaxies

As a simple application of (

55), let us calculate the

rotation curve,

, of a scale-invariant mass,

M, located at the origin, as it appears to an astronomer of native scale

. Above,

r is the distance to the origin of a test mass orbiting

M in circles at velocity

v. Since

in (

55) is time-independent, the time-dependence of

can only be through the combination

for some function

. Looking for a circular motion solution in the

plane,

and equating coefficients of

and

for each component, the system (

55) reduces to two, first order ODE’s for

and

. The equation for

readily integrates to

for some integration constant

, and for

r it reads

Solutions of (

58) with

as initial condition, all diverge in magnitude for

except for a single value of

for which

in that limit; for any other

,

rapidly diverges to

respectively; the map

is invertible. We note in advance that, for a mistuned

this divergence starts well before the the weak field approximation breaks down due to the

term, and neglected relativistic and self-force terms become important, and being so rapid,

, those would not tame a rogue solution. It follows that there is no need to complicate our hitherto simple analysis in order to conclude that

is a necessary conditions for

r to correspond to an

.

Solutions of (

58) which are well-behaved for

admit a relatively simple analytic form. Reinstating

c and defining

the result is

having the following power law asymptotic forms

with the corresponding asymptotic circular velocity,

With these asymptotic forms the reader can verify that, in the large

regime, (

56), which in this case takes the form:

is indeed satisfied for any

. This almost certainly generalizes to the following: The paths,

, solving (

55)(

46) for a bound system of scale-independent masses (indexed by

k), approach at large

the form

where

are the Newtonian paths of such a system; (

63) is an exact symmetry of Newtonian gravity. Finally, for a scale-dependent mass in (

58), an

is obtained by the large-scale regularity condition which is not of the form

. This results in a rotation curve

which is not flat at large

, and an

which, depending on the form of

, may not even converge to zero at large

.

Moving, next, to a more realistic representation of disc galaxies. For a general gravitational potential,

, sourced via (

46) by a planar, axially symmetric mass density

—

being the radial distance from the galactic axis in the galactic plane—and for a test mass circularly orbiting the symmetry axis in the galactic plane, the counterpart of (

58) reads

The time-independent mass density,

, is approximated by a (sufficiently dense) collection of concentric line-rings, each composed of a (sufficiently dense) collection of particles evenly spaced along the circumference. Next, recall that in the above warm-up exercise, the solution of (

64) for each such particle is well behaved only for one, carefully tuned value of

. This sensitivity results form instability of the the o.d.e. (

64) in the

direction, inherited from that of

, and is not a peculiarity of the Coulomb potential. To find the rotation curve one needs to simultaneously propagate with (

64) each ring—or rather a single representative particle from each ring—

, using an initial guess for

(where

is now a ring index, labeling the ring whose radius at

equals

, viz.,

). Unlike in the previous case, the (mean-field) Newtonian potential of the disc at scale

,

, solution of (

40), must be re-computed at each

. The rotation curve is obtained as that (unique) guess,

, for which no ring diverges in the limit

. In so finding the rotation curve the scale dependence of individual particles comprising the disc needs to be specified. If those are fixed-point particles then their mass is scale-independent by definition. Moreover, as mentioned above, a scale-dependent mass leads to manifest contradictions with observations. In light of this, a scale independent mass is assumed modulo some caveats discussed in

sect.3.4. Note the implication of the scale-invariant-mass approximation, applicable to any gravitating system: Although

is the desired spacetime path, by construction and the

s-translation invarinace of (

55),

for any

s would also be a permissible path at

. In other words, (

55) with the regularity condition at

, generates a continuous family of spacetime paths which could be observed at any fixed native scale,

in particular.

The algorithm described above for finding the rotation curve, although conceptually straightforward, could be numerically challenging and will be attempted elsewhere. However, much can be inferred from it without actually running the code. Mass tracers lying at the outskirts of a disc galaxy, experience almost the same,

potential, where

M is the galactic mass, independently of

. This is clearly so at

, as higher order multipoles of the disc are negligible far away from the galactic center, but also at larger

, as all masses comprising the disc converge towards the center, albeit at different paces. The analytic solution (

60) can therefore be used to a good approximation for such traces, implying the following power-law relation between the asymptotic velocity,

, of a galaxy’s rotation curve and its mass,

M,

Such an empirical power law, relating

M and

, is known as the

Baryonic Tully-Fisher Relation (BTFR), and is the subject of much controversy. There is no concensus regarding the conssistency of observations with a zero intrinsic scatter, nor is there an agreemnet about the value of the slope—3 in our case—when plotting

vs.

. Some groups [

5] see a slope

while other [

6] insisting it is closer to 4 (both ‘high quality data’ representatives, using primary distance indicaors). While some of the discrepancy in slope estimates can be attributed to selection bias and different methods of estimating the galactic mass, the most important factor is the inclusion of relatively low-mass galaxies in the latter. When restricting the mass to lie above

, almost all studies support a slope close to 3. The recent study [

7] which includes some new, super heavy galaxies, found a slope

and a

-axis intercept of

for the massive part of the graph. Since the optimization method used in finding those two parameters is somewhat arbitrary, imposing a slope of 3 and fitting for the best intercept is not a crime against statistics. By inspection this gives an intercept of

, consistent with [

5], which by (

65) corresponds to

km.

With an estimate of

at hand, yet another prediction of our model can be put to test, pertaining to the radius at which the rotation curve transitions to its flat part. The form (

60) of

implies that the transition from the scaling to the coarsening regime occurs at

. At that scale the radius assumes a value

. Using standard units where velocities are given in km/s and distances in kpc, gives

. Now, in galaxies with a well-localized center—a combination of a massive bulge and (exponential) disc—most of the mass is found within a radius

, lying to the right of the Newtonian curve’s maximum. Approximating the potential at

by

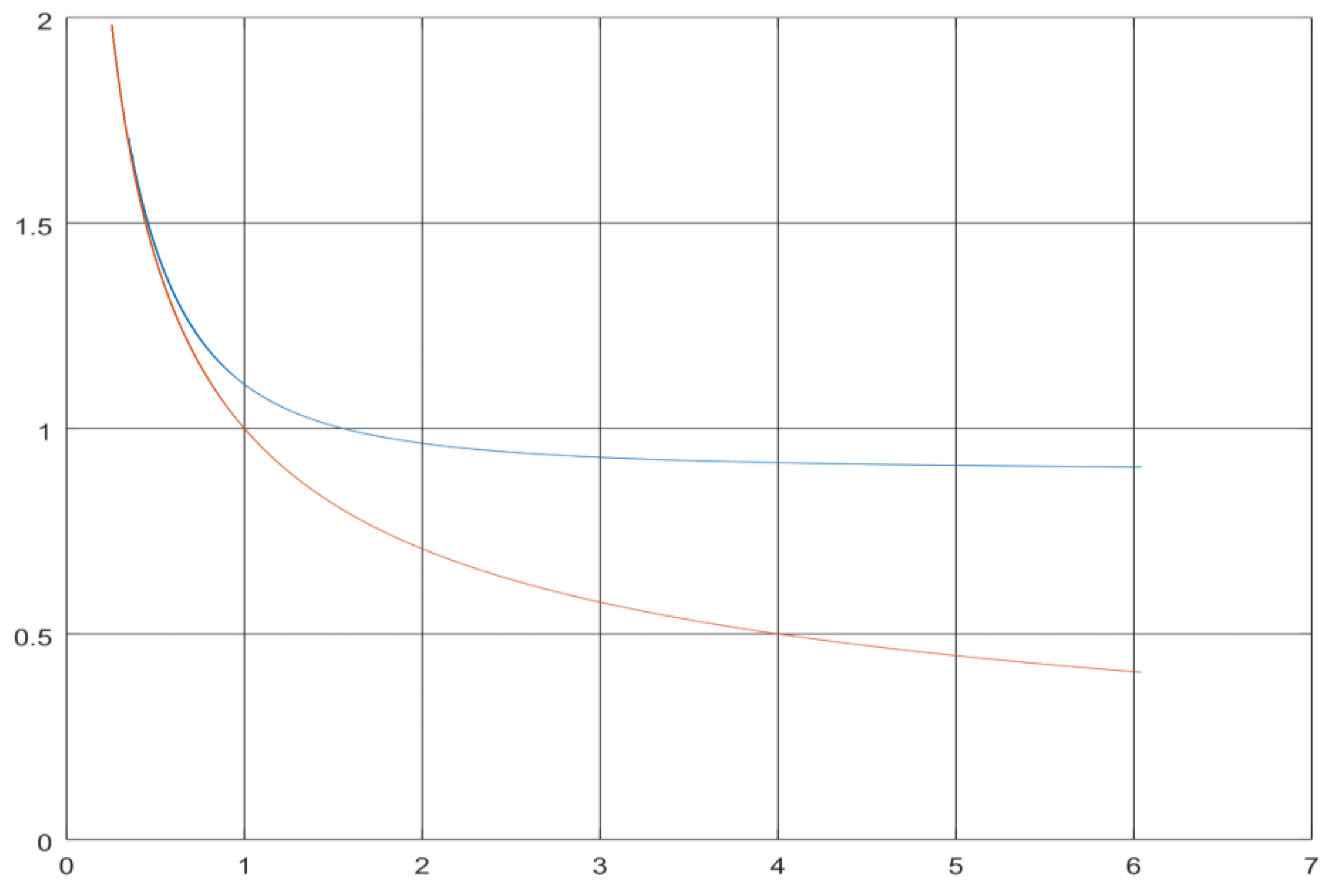

, the transition of the rotation curve from scaling to coarsening, with its signature rise from a flat part seen in

fig.2, is expected to show at

, followed by a convergence to the galaxy-specific Newtonian curve. This is corroborated in all cases—e.g. galaxies NGC2841, NGC3198, NGC2903, NGC6503, UGC02953, UGC05721, UGC08490... in fig.12 of [

8]

The above sanity checks indicate that the rotation curve predicted by our model cannot fall too far from that observed, at least for massive galaxies; it is guarantied to coincide with the Newtonian curve near the galactic center, depart from it approximately where observed, eventually flattening at the right value.

However, the above checks do not apply to diffuse, typically gas dominated galaxies, several orders of magnitude lighter. More urgently, a slope

is difficult to reconcile with [

6] which finds a slope

when such diffuse galaxies are included in the sample. Below we therefore point to two features of the proposed model possibly explaining said discrepancy. First, our model predicts that

attributed in [

6] to such galaxies would turn out to be a gross overestimation should their rotation curves be

significantly extended beyond the handful of data points of the flat portion. To see why, consider an alternative solution strategy for finding a rotation curve (which may also turn out to be computationally superior):

By construction the solution curve is Newtonian at

, having a

tail past the maximum, whose

rightmost part ultimately evolves into the flat segment at

. We can draw two main distinctions between the flows to

of massive and diffuse galaxies’ rotation curves. First, since the hypothetical Newtonian curve at

—that which is based on baryonic matter only—is rising/leveling at the point of the outmost velocity tracer in the diffuse galaxies of [

6], we can be certain that this tracer was at the the rising part/maximum of the

curve, rather than on its

tail as in massive galaxies. This means that, in massive galaxies, the counterpart of the short, flat segment of a diffuse galaxy’s r.c., is rather the short flat segment near its maximum, seen in most such galaxies near the maximum of the hypothetical Newtonian curve. Second, had tracers further away from the center been measured in diffuse galaxies, the true flat part would have been significantly lower relative to this maximum than in massive galaxies. With some work this can be shown via the inhomogeneous flow of

derived from (

64)

where

r is a solution of (

64) (re- expressed as a function of

). The gist of the argument is that, solutions of (

66) deep in the coarsening regime, upon flowing to smaller

, decay approximately as

, whereas in the scaling regime they remain constant (see (

61)). In massive galaxies the entire flow from

to

of a tracer originally at the maximum of the r.c. is in the coarsening regime, while in diffuse galaxies it is mostly in a hybrid, coarsening scaling intermediate mode. The velocity of that tracer relative to the true

therefore decays more slowly in diffuse galaxies. Note that to make the comparison meaningful a common

must be chosen for both galaxies such that

is equal in both.

The second possible explanation for the slopes discrepancy, which could further contribute to an intrinsic scatter around a straight BTFR, involves a hitherto ignored transparent component of the energy-momentum tensor. As emphasized throughout the paper, the

A-field away from a non-uniformly moving particle (almost solving Maxwell’s equations in vacuum) necessarily involves both advanced and retarded radiation. Thus even matter at absolute zero constantly ‘radiates’, with advanced fields compensating for (retarded) radiation loss, thereby facilitating zero-point motion of matter. The

A-field at spacetime point

away from neutral matter is therefore rapidly fluctuating, contributed by all matter at the intersection of its worldline with the light-cone of

. We shall refer to it as the Zero Point Field (ZPF), a name borrowed from Stochastic Electrodynamics although it does not represent the very same object. Being a radiation field, the ZPF envelopes an isolated body with an electromagnetic energy ‘halo’, decaying as the inverse distance squared—which by itself is not integrable!—merging with other halos at large distance. Such ‘isothermal halos’ served as a basis for a ‘transparent matter’ model in a previous work by the author [

2] but in the current context its intensity likely needs to be much smaller to fit observations. Space therefore hosts a non-uniform ZPF peaking where matter is concentrated, in a way which is sensitive to both the type of matter and its density. This sensitivity may result both in an intrinsic scatter of the BTFR, and in a systematic departure from ZPF-free slope=3 at lower mass. Indeed, in heavy galaxies, typically having a dominant massive center, the contribution of the halo to the enclosed mass at

is tiny. Beyond

orbiting masses transition to their scaling regime, minimally influenced by additional increase in the enclosed mass at

r. The situation is radically different in light, diffuse galaxies, where the ratio of

is much higher throughout the galaxy, and much more of the non-integrable tail of the halo contributes to the enclosed mass at the point where velocity tracers transition to their scaling regime. This under estimation of the effective galactic mass, increasing with decreasing baryonic mass, would create an illusion of a BTFR slope greater than 3.

3.2.2. Other Probes of ‘Dark Matter’

Disc galaxies are a fortunate case in which the worldline of a body transitions from scaling to coarsening at a common scale along its entire worldline (albeit different scales for different bodies). They are also the only systems in which the velocity vector can be inferred solely from its projection on the line-of-sight. In pressure supported systems, e.g., globular clusters, elliptical galaxies or galaxy clusters, neither is true. Some segments of a worldline could be deep in their scaling regime while others in the coarsening, rendering the analysis of their collective scale flow more difficult. One solution strategy leverages the fact that, all the worldlines of a bound system are deep in their coarsening regime at sufficiently large scale, where their fixed-

dynamics is well approximated using Newtonian gravity. Starting with such a Newtonian system at sufficiently large

, the integration of (

55) to small

is in its stable direction, hence not at risk of exploding for any initial choice of Newtonian paths. If the Newtonian system at

is chosen to be virialized, a ‘catalog’ of solutions of pressure supported systems extending to arbitrarily small

can be generated, and compared with line-of-sight velocity projections of actual systems. As remarked above, the transition from coarsening to scaling generally doesn’t take place at a common scale along the worldline of any single member of the system. However, if we assume that there exists a rough transition scale,

, for the system as a whole in the statistical sense, which is most reasonable in the case of galaxy clusters, then immediate progress can be made. Since in the scaling regime velocities are unaltered, the observed distribution of the line-of-sight velocity projections should remain approximately constant for

, that of a virialized system, viz., Gaussian of dispersion

. On the other hand, at

a virialized system of total mass

M satisfies

where

is the velocity dispersion, and

r is the radius of the system, which is just (

62) with

. On dimensional grounds it then follows that

would be the counterpart of

from (

65), implying

which is in rough agreement with observations. The proportionality constant can’t be exactly pinned using such huristic arguments, but its observed value is on the same order of magnitude as that implied by (

65).

Applying our model to gravitational lensing in the study of dark matter requires better understanding of the nature of radiation. This is murky territory even in conventional physics and in next section initial insight is discussed. To be sure, Maxwell’s equations in vacuum are satisfied away from

, although only ‘almost so’, as discussed in

sect.3. However, treating them as an initial value problem, following a wave-front from emitter to absorber is meaningless for two reasons. First, tiny,

local deviations from Maxwell’s equations could become significant when accumulated over distances on the order of

. Second, in the proposed model extended particles ‘bump into one another’ and their centers jolt as a result—some are said to emit radiation and other absorb it, and an initial-value-problem formulation is, in general, ill-suited for describing such process. Nonetheless, incoming light—call it a photon or a light-ray—does posses an empirical direction when detected. In flat spacetime this could only be the spatial component of the null vector connecting emission and absorption events, as it is the only non arbitrary direction. A simple generalization to curved spacetime, involving multiple, freely falling observers, selects a path,

, everywhere satisfying the

light-cone condition . Every null geodesic satisfies the light-cone condition, but not the converse. In ordinary GR, the only non arbitrary path connecting emission and absorption events which respects the light-cone condition and locally depends on the metric and its first to derivatives is indeed a null geodesic. In our model, a solution of (

57) which is well behaved on all scales, further satisfying the light-cone condition for

, is an appealing candidate: It becomes a null geodesic at large scales, while the scaling operator alone preserves the light-cone condition.

Furthermore, in GR the deflection angle of a light ray due to gravitational lensing, by a compact gravitating system of mass

M, is

, where

R is the impact parameter. When

is in its scaling regime, our model’s

remains constant. If the system is likewise in its scaling regime, (

67) implies that its virial mass,

, scales according to

, as does the impact parameter of

,

. The conventional mass estimate based on the virial theorem, of this

-dependent family of gravitating systems, would then agree with that which is based on (conventional) gravitational lensing,

, up to a constant, common to all members—recall that this entire family appears in the ‘catalog’ of

systems. Extending this family to large

, the two estimates will coincide by construction. Thus if the system and

transition approximately at a common

, this proportionality constant can only be close to 1. This is apparently the case in most observations pertaining to galaxy clusters. Nonetheless, the two methods according to our model need not, in general, produce identical results. The degree to which they disagree depends on the exact scale-flow of

, which is one of those calculations avoided thus far, involving a path non-uniformly (in scale) transitioning from coarsening to scaling.

A final caveat regarding the application of (

57) to imaging, is that it is not clear whether the light-cone condition is automatically satisfied by all paths thus defined or that it should be imposed as an additional constraint. Nor is it even obvious that this condition must be satisfied exactly. In trying to figure this out one should remember that, in general, solutions of (

57) that are well behaved on all scales are not solutions of any o.d.e. in

for a fixed

.