The alert reader must have anticipated the main result of the previous section, namely, that consists of freely moving particles. By linearity, particles can move through one another uninterrupted and if so, they are non interacting particles which should better have straight paths. Enabling their mutual interaction therefore requires some form of nonlinearity, either in the coarsener, , or in the scaling part. Further recalling our commitment to general covariance as a precondition for any fundamental physical theory, nonlinearity is inevitably and, in a sense, uniquely forced upon us. A nonlinear model further supports a plurality of particles, having different sizes which are different from the common in a linear theory. This frees , ultimately estimated at km, to play a role at astrophysical scales.

Operating with

on (

19), using the antisymmetry of

, the commutators of covariant derivatives

and the symmetries of the Riemann tensor, gives

, i.e.,

is covariantly conserved at any scale,

s. Operating with

on (

16), the second term of this operator annihilates the coarsener by the above remarks. The scaling piece combines the covariant generalization of the flat spacetime conversion

with a novel nonlinear term (see

Section 3.2 below). On the l.h.s. we have

. We would like to swap the order of

W and

, which would give

by (

19). However,

could implicitly depend on the scale

s through

. Nonetheless the order is swapped and we shall review the approximation involved in doing so once

is determined. The combined result finally reads

more suited for analysis. For example, in the case of flat spacetime and naive scaling,

, the particle solution of the

J-field associated with (

18) is the familiar Gaussian

from the previous sections. It is emphasized that

and its associated scale flow are merely analytic tools, not to be put on equal footing with

and its flow. As the nonlinear term arising from scaling does not involve

but rather

, for a given

and

equation (

21) describes the linear but inhomogeneous (in both spacetime and scale) flow of

.

Relation (

19) is formally equivalent to Maxwell’s equations with

sourcing

’s wave equation. However,

is not an independent object as in classical electrodynamics but a marker of the locus of privileged points at which the Maxwell coarsener does not annihilate

(distinct

’s differing by some

therefore have identical

’s). For

and

to mimic those of classical electrodynamics,

must also be localized along curved worldlines traced by solutions of the Lorentz force equation in

(which as already shown in the scalar case, necessitates a nonlinear scale flow). And just like in the scalar-particle case, where higher order cumulants (

) are `awakened’ by its center’s nonuniform motion, deforming its stationary shape, so does the

“adjunct" (in the jargon of action-at-a-distance electrodynamics) to each such

gets deformed. Due to the extended nature of an

A-particle, and unlike in

models

3, these deformations at

are

not encoded in the local motion of its center at time

t, but rather on its motion at retarded and advanced times,

(assuming flat spacetime for simplicity). However, associating such temporal incongruity with `radiation’ can be misleading, as it normally implies the freedom to add any homogeneous solution of Maxwell’s equations to

which is clearly nonsensical from our perspective. Consequently, the retarded solution cannot be imposed on

and in general,

contains a mixture of both advanced and retarded parts, which varies across spacetime. The so-called radiation arrow of time manifested in every macroscopic phenomenon must therefore receive an alternative explanation (see

Section 3.4.2).

Now, why should

be confined to the neighborhood of a worldline? As already seen in the linear, time-dependent case, a scale-flow such as (

16) suffers from instability in both

s-directions: In the

direction it is due to the spatial part of the coarsener, whereas in

direction it is its temporal part. If we examine the scale flow of

inside a `lab’ of dimension much smaller than

, centered at the origin without loss of generality, then the coarsener completely dominates the flow. It follows that

requires that it be

almost annihilated by

, or else it would rapidly diverge. This can be true if either: the scale of variation of

is on par with

or greater—as in the case of our static, Gaussian fixed-point; or else

, except around privileged points where the scaling-field grows to the order of

, balancing the non-vanishing coarsener piece. This is where

is focused, as shown in

Section 3.1.2 below. “Almost" is emphasized above because exact annihilation would leave a flow governed entirely by scaling. It is precisely the fact that, at distances from

that are much smaller than

, the action of the coarsener is on the order of that of the scaling piece, which gives rise to nontrivial physics. This will be a recurrent theme in the rest of the paper.

3.2. The Motion of Matter Lumps in a Weak Gravitational Field

Equation (

45) prescribes the scale flow of the metric (in the Newtonian approximation), given the a set,

, of worldlines associated with matter lumps. To determine this set, an equation for each

, given

, is obtained in this section. This is done by analyzing the scale flow of the first moment of

associated with a general matter lump, using (

21). An obstacle to doing so comes from the fact that,

now incorporates both gravitation and electromagnetic interactions in a convoluted way, as the existence of gravitating matter depends on it being composed of charged matter. In order to isolate the effect of gravity on

, we first analyze the motion of a body in the absence of gravity, i.e.,

,

with

the Minkowskian coordinates. To this end we first need to better understand the scale flow (

21) of

. Using (

24) and (

19) plus some algebra the scaling piece in (

21) reads

with

The first two terms in (

46) are the familiar

conversion, to which a `matter vector’,

, is added, consisting of inhomogeneous terms, and the homogeneous,

term, modifying naive scaling in a way which conserves-in-scale charge for a time-independent

In the absence of gravity, the swapping of

and

leading to the l.h.s. of (

21) is fully justified. Combined, we then get

Since

, taking the divergence of (

49) implies

, viz., a conserved-in-time `matter charge’. Defining

the (conserved in time-) electric charge, and integrating (

49) over three-space implies

i.e., electric charge is conserved in scale if and only if the matter charge vanishes. That the latter is identically true follows from

where the vanishing of the second integral follows, after integration by parts, from the explicit form (

47) of

Next, multiplying (

49) by

and integrating over a ball,

B, containing a body of charge

q, results in

where

is an object’s `center-of-charge’. Above and in the rest of this section, the charge of a body, assumed nonzero for simplicity, is only used as a convenient tracer of matter.

The integral in (

51) is the first moment of a distribution,

, whose zeroth moment vanishes. It vanishes identically for a spherically symmetric

, and even for a skewed

, the result is a constant,

, on the order of the support of

. For a particle’s path not passing close to the scaling enter (without loss off generality),

. This integral term is therefore ignored for the rest of the paper, and the reader can easily verify that its inclusion would have had a negligible influence on the results.

With said integral ignored, (

51) becomes (

14). And as proved in that case, solutions for

must all be straight, non tachyonic worldlines. The effect of gravity on those is derived by including a weak field in the the flow of the first-moment projection of (

21). Since gravity is assumed to play a negligible role in the structure of matter, the way this field enters the flat spacetime analysis is via the scaling field,

, with

incorporating the metric, and by `dotting the commas’ in partial derivatives. Before analyzing the first moment we note that, the previous zeroth-moment analysis can be repeated with

, at most introducing curvature-terms corrections due to the non-commutativity of covariant derivatives (

20), which can be neglected in the Newtonian approximation. As for the the swapping of

and

made in arriving at (

49), using

(viz., ordinary derivatives can replace covariant ones) in the definition (

19) of

, it is easily established that the swapping introduces an error equal to

with the determinant

. This error is negligible when competing with

, containing extra spatial derivatives of

at its center. Thus

is not only covariantly conserved in time, which can be written

, by virtue of the last identity in (

19), but also in scale,

Continuing in the Newtonian approximation of the metric (

38) for simplicity, and further assuming non-relativistic motion, i.e.,

(say, in the

sense), a straightforward calculation of the Christoffel symbols to first order in

incorporating

gives

Ignoring

corrections to the isotropic coarsener, the net effect of of the potential in the Newtonian approximation is to render the coarsener unisotropic through its gradient. Multiplying (

49) with the modified d’Alembertian (

53) by

and integrating over

B, the

cancels (to first order in

) the

factor multiplying the spatial piece in (

53), which is then integrated by parts, assuming

is approximately constant over the extent of the body. Since

and

the modification to the scaling piece (

46) only introduces an

correction to the

term in (

51) which is neglected in the Newtonian approximation. Further neglecting the

contribution to the double time-derivative piece, the first moment projection of (

21) finally reads

This equation is just (

14) with an extra `force-term’ on its r.h.s. which could salvage a non uniformly moving solution,

, from the catastrophic fate at

suffered by its linear counterpart.

At sufficiently large scales,

, when all relevant masses contributing to

occupy a small ball of radius

centered at the origin of scaling without loss of generality, the scaling part on the r.h.s of (

54) becomes negligible compared with the force term, rather benefiting from such crowdedness (

can similarly be assumed without loss of generality). It follows that each

would grow—extremely rapidly as we show next—with increasing

even when the weak-field approximation is still valid, implying that the underlying

is not in

. The only way to keep the scale evolution of

under control is for the acceleration term to similarly grow,

almost canceling the force term but not quite, which is critically important; it is the fact that the sum of these two terms, both originating from the coarsener, remains on the order of the scaling term, which is responsible for a nontrivial, non pure scaling

. This means that each worldline converges at large scales to that satisfying Newton’s equation

At small scales the opposite is true. The scaling part dominates and any

scaling path, i.e.,

is well behaved. Combined: at large scales

is determined, then simply scaled at small scales, gradually converging locally to a freely moving particle. Finally, (

55) must be true also for a loosely bound system, e.g. a wide binary moving in a strong external field, implying that Newton’s law applies also to their relative vector, not merely to their c.o.m.

Deriving a manifestly covariant generalization of (

54) is certainly a worthwhile exercise. However, in a weak field the result could only be

with

some scalar parameterization of the worldline traced by

. Above,

is the Christoffel symbols associated with

, i.e., the analytic continuation of the metric, seen as a function of Newton’s constant, to

. Recalling from

Section 3.1.3 that the fixed-point

is a solution of the standard EFE analytically continued to

,

in that case is therefore just the Christoffel symbol associated with standard solutions of EFE’s. The previous, Newtonian approximation is a private case of this, where

contains a factor of

G. Note however that the path of a particle in our model is a covariantly defined object irrespective of the analytic properties of

. Resorting to analyticity simply provides a constructive tool for finding such paths whenever

is analytic in

G. In such cases, the covariant counterpart of (

55) becomes the standard geodesic equation of GR which gives great confidence that this is also the case for non-analytic

.

The reasons for trusting (

56) are the following. It it is manifestly covarinat, as is our model; At nonrelativistic velocities and weak field, (

56) implies

which, when substituted into the

i-components of (

56), recovers (

54); It only involves local properties of

and

, i.e., their first two derivatives, which must also be a property of a covariant derivation, as is elucidated by the non-relativistic case. Thus (

56) is the only candidate up to covariant, higher derivatives terms involving

and

, or nonlinear terms in their first or second derivatives, all becoming negligible in weak fields/ at small accelerations.

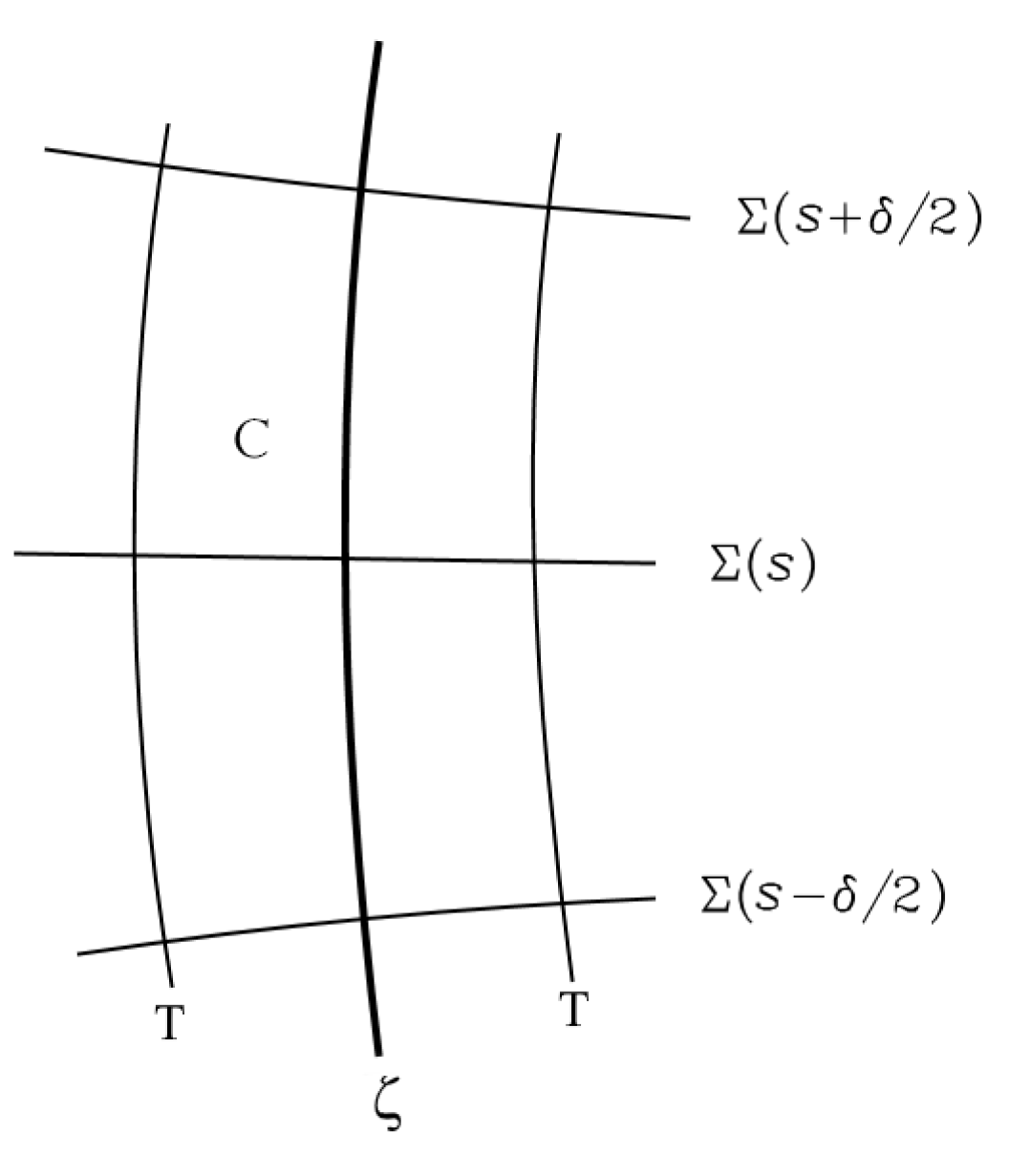

In conclusion of this section we wish to relate (

56) to the fact that

is not covariantly conserved by virtue of (

27). It was well known already to Einstein that the geodesic equation follows from local energy-momentum conservation under reasonable assumptions. Similarly, the Lorentz force equation follows quite generally from the basic tenets of classical electrodynamics (

30),(

29),(

19). Referring to

Figure 1, both results are derived by integrating

over a world-cylinder,

C, with the

term obtained by converting part of the volume integral into a surface integral over the

’s via (a relativistic generalization of-) Stoke’s theorem, leaving the remaining part for the `force term’, which gives

in the case of gravity. The integral over

T represents small radiative corrections to the geodesic/Lorentz-force equation which can be ignored in what follows. A crucial point in that derivation is that the result is insensitive to the form of

C so long as the

’s contain the support of the particle’s energy-momentum distribution. This insensitivity would not carry to the r.h.s. of (

27) should it be transferred sides, whether or not

is to include the self-field of the particle. Thus attempting to generalize the geodesic equation based on (

27) in the hope that it would reproduce fixed-

solutions of (

56) is bound to fail. Nonetheless, since the conservation-violating r.h.s. of (

27) is a tiny

, it can consistently be ignored for any reasonable choice of

C whenever the individual terms in the geodesic equation are much larger, i.e., at large scales; it is only at small scales that each term becomes comparable to the r.h.s. even for reasonable choices of

C. And since in the limit

paths become simple geodesics at any scale according to (

56), the two length parameters,

,

are not independent, constrained by consistency of solutions such as the above, and likely additional ones involving the structure of matter, as hinted to by the fixed-point example in

Section 3.1.2.

3.2.1. Application: The Rotation Curve of Disc Galaxies

As a simple application of (

54), let us calculate the

rotation curve,

, of a scale-invariant mass,

M, located at the origin, as it appears to an astronomer of native scale

. Above,

r is the distance to the origin of a test mass orbiting

M in circles at velocity

v. Since

in (

54) is time-independent, the time-dependence of

can only be through the combination

for some function

. Looking for a circular motion solution in the

plane,

and equating coefficients of

and

for each component, the system (

54) reduces to two, first order ODE’s for

and

. The equation for

readily integrates to

for some integration constant

, and for

r it reads

Solutions of (

57) with

as initial condition, all diverge in magnitude for

except for a single value of

for which

in that limit; for any other

,

rapidly diverges to

respectively; the map

is invertible. We note in advance that, for a mistuned

this divergence starts well before the the weak field approximation breaks down due to the

term, and neglected relativistic and self-force terms become important, and being so rapid,

, those would not tame a rogue solution. It follows that there is no need to complicate our hitherto simple analysis in order to conclude that

is a necessary conditions for

r to correspond to an

.

Solutions of (

57) which are well-behaved for

admit a relatively simple analytic form. Reinstating

c and defining

the result is

having the following power law asymptotic forms

with the corresponding asymptotic circular velocity,

With these asymptotic forms the reader can verify that, in the large

regime, (

55), which in this case takes the form:

is indeed satisfied for any

. This almost certainly generalizes to the following: The paths,

, solving (

54)(

45) for a bound system of scale-independent masses (indexed by

k), approach at large

the form

where

are the Newtonian paths of such a system; (

62) is an exact symmetry of Newtonian gravity. Finally, for a scale-dependent mass in (

57), an

is obtained by the large-scale regularity condition which is not of the form

. This results in a rotation curve

which is not flat at large

, and an

which, depending on the form of

, may not even converge to zero at large

.

Moving, next, to a more realistic representation of disc galaxies. For a general gravitational potential,

, sourced via (

45) by a planar, axially symmetric mass density

—

being the radial distance from the galactic axis in the galactic plane—and for a test mass circularly orbiting the symmetry axis in the galactic plane, the counterpart of (

57) reads

The time-independent mass density,

, is approximated by a (sufficiently dense) collection of concentric line-rings, each composed of a (sufficiently dense) collection of particles evenly spaced along the circumference. Next, recall that in the above warm-up exercise, the solution of (

63) for each such particle is well behaved only for one, carefully tuned value of

. This sensitivity results form instability of the the o.d.e. (

63) in the

direction, inherited from that of

, and is not a peculiarity of the Coulomb potential. To find the rotation curve one needs to simultaneously propagate with (

63) each ring—or rather a single representative particle from each ring—

, using an initial guess for

(where

is now a ring index, labeling the ring whose radius at

equals

, viz.,

). Unlike in the previous case, the (mean-field) Newtonian potential of the disc at scale

,

, solution of (

39), must be re-computed at each

. The rotation curve is obtained as that (unique) guess,

, for which no ring diverges in the limit

. In so finding the rotation curve the scale dependence of individual particles comprising the disc needs to be specified. If those are fixed-point particles then their mass is scale-independent by definition. Moreover, as mentioned above, a scale-dependent mass leads to manifest contradictions with observations. In light of this, a scale independent mass is assumed modulo some caveats discussed in

Section 3.4. Note the implication of the scale-invariant-mass approximation, applicable to any gravitating system: Although

is the desired spacetime path, by construction and the

s-translation invarinace of (

54),

for any

s would also be a permissible path at

. In other words, (

54) with the regularity condition at

, generates a continuous family of spacetime paths which could be observed at any fixed native scale,

in particular.

The algorithm described above for finding the rotation curve, although conceptually straightforward, could be numerically challenging and will be attempted elsewhere. However, much can be inferred from it without actually running the code. Mass tracers lying at the outskirts of a disc galaxy, experience almost the same,

potential, where

M is the galactic mass, independently of

. This is clearly so at

, as higher order multipoles of the disc are negligible far away from the galactic center, but also at larger

, as all masses comprising the disc converge towards the center, albeit at different paces. The analytic solution (

59) can therefore be used to a good approximation for such traces, implying the following power-law relation between the asymptotic velocity,

, of a galaxy’s rotation curve and its mass,

M,

Such an empirical power law, relating

M and

, is known as the

Baryonic Tully-Fisher Relation (BTFR), and is the subject of much controversy. There is concensus regarding the conssistency of observations with a zero intrinsic scatter, nor is there an agreemnet about the value of the slope—3 in our case—when plotting

vs.

. Some groups [

5] see a slope

while other [

6] insisting it is closer to 4 (both `high quality data’ representatives, using primary distance indicaors). While some of the discrepancy in slope estimates can be attributed to selection bias and different methods of estimating the galactic mass, the most important factor is the inclusion of relatively low-mass galaxies in the latter. When restricting the mass to lie above

, almost all studies support a slope close to 3. The recent study [

7] which includes some new, super heavy galaxies, found a slope

and a

-axis intercept of

for the massive part of the graph. Since the optimization method used in finding those two parameters is somewhat arbitrary, imposing a slope of 3 and fitting for the best intercept is not a crime against statistics. By inspection this gives an intercept of

, consistent with [

5], which by (

64) corresponds to

km.

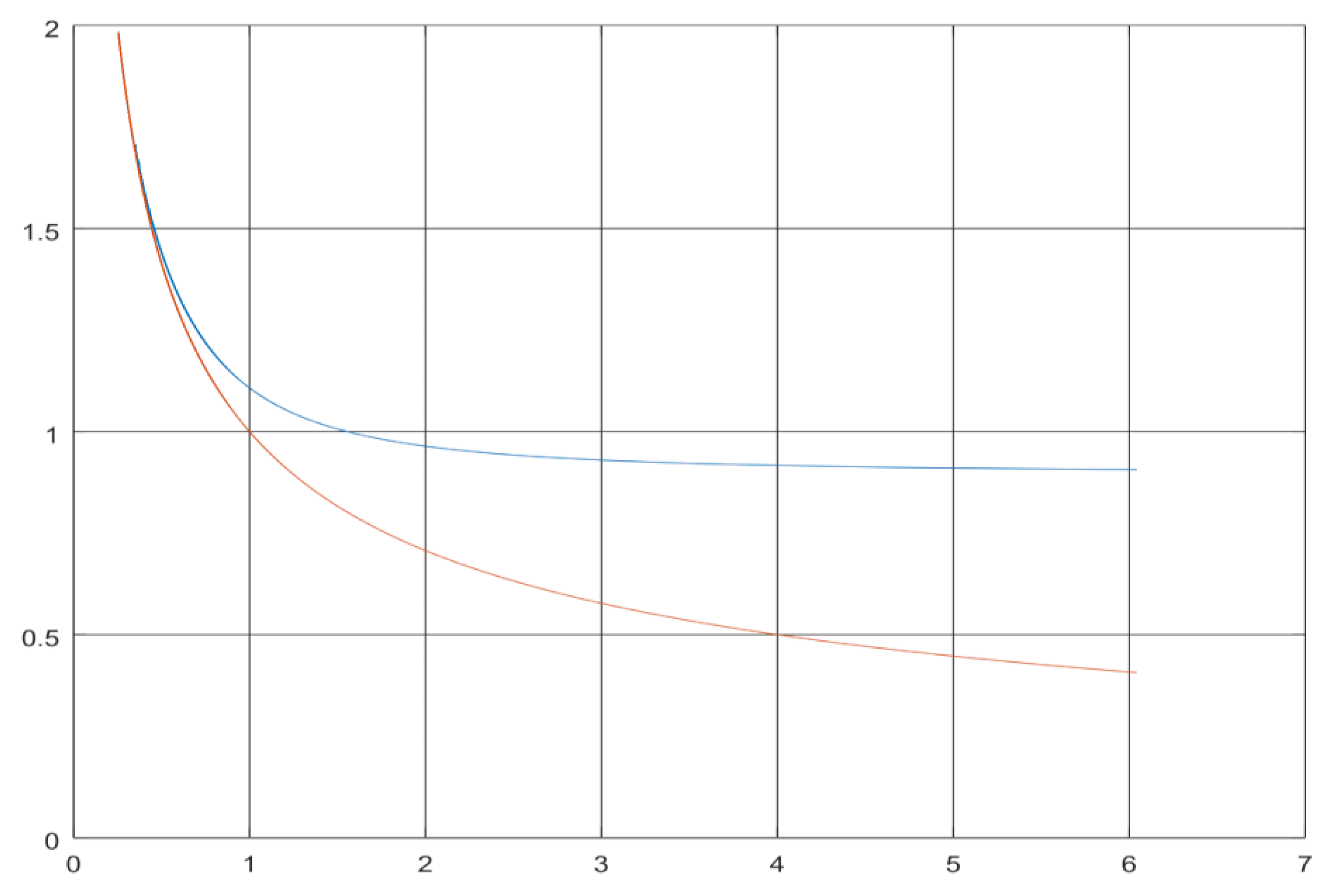

With an estimate of

at hand, yet another prediction of our model can be put to test, pertaining to the radius at which the rotation curve transitions to its flat part. The form (

59) of

implies that the transition from the scaling to the coarsening regime occurs at

. At that scale the radius assumes a value

. Using standard units where velocities are given in km/s and distances in kpc, gives

. Now, in galaxies with a well-localized center—a combination of a massive bulge and (exponential) disc—most of the mass is found within a radius

, lying to the right of the Newtonian curve’s maximum. Approximating the potential at

by

, the transition of the rotation curve from scaling to coarsening, with its signature rise from a flat part seen in

Figure 2, is expected to show at

, followed by a convergence to the galaxy-specific Newtonian curve. This is corroborated in all cases—e.g. galaxies NGC2841, NGC3198, NGC2903, NGC6503, UGC02953, UGC05721, UGC08490... in fig.12 of [

8]

The above sanity checks indicate that the rotation curve predicted by our model cannot fall too far from that observed, at least for massive galaxies; it is guarantied to coincide with the Newtonian curve near the galactic center, depart from it approximately where observed, eventually flattening at the right value.

However, the above checks do not apply to diffuse, typically gas dominated galaxies, several orders of magnitude lighter. More urgently, a slope

is difficult to reconcile with [

6] which finds a slope

when such diffuse galaxies are included in the sample. Below we therefore point to two features of the proposed model possibly explaining said discrepancy. First, our model predicts that

attributed in [

6] to such galaxies would turn out to be a gross overestimation should their rotation curves be

significantly extended beyond the handful of data points of the flat portion. To see why, consider an alternative solution strategy for finding a rotation curve (which may also turn out to be computationally superior):

Start with a guess for the mass distribution of a galaxy at some large enough scale,

, such that its rotation curve is fully Newtonian (If our conjecture regarding (

62) is true then the flow to even larger

is guaranteed not to diverge for any such initial guess).

Let this Newtonian curve flow via (

63)(

45) to

—no divergence problem in this, stable direction of the flow—comparing the resultant mass distribution at

with the observed distribution

Repeat step 1 with an improved guess based on the results of 2, until an agreement is reached. By construction the solution curve is Newtonian at

, having a

tail past the maximum, whose

rightmost part ultimately evolves into the flat segment at

. We can draw two main distinctions between the flows to

of massive and diffuse galaxies’ rotation curves. First, since the hypothetical Newtonian curve at

—that which is based on baryonic matter only—is rising/leveling at the point of the outmost velocity tracer in the diffuse galaxies of [

6], we can be certain that this tracer was at the the rising part/maximum of the

curve, rather than on its

tail as in massive galaxies. This means that, in massive galaxies, the counterpart of the short, flat segment of a diffuse galaxy’s r.c., is rather the short flat segment near its maximum, seen in most such galaxies near the maximum of the hypothetical Newtonian curve. Second, had tracers further away from the center been measured in diffuse galaxies, the true flat part would have been significantly lower relative to this maximum than in massive galaxies. With some work this can be shown via the inhomogeneous flow of

derived from (

63)

where

r is a solution of (

63) (re- expressed as a function of

). The gist of the argument is that, solutions of (

65) deep in the coarsening regime, upon flowing to smaller

, decay approximately as

, whereas in the scaling regime they remain constant (see (

60)). In massive galaxies the entire flow from

to

of a tracer originally at the maximum of the r.c. is in the coarsening regime, while in diffuse galaxies it is mostly in a hybrid, coarsening scaling intermediate mode. The velocity of that tracer relative to the true

therefore decays more slowly in diffuse galaxies. Note that to make the comparison meaningful a common

must be chosen for both galaxies such that

is equal in both.

The second possible explanation for the slopes discrepancy, which could further contribute to an intrinsic scatter around a straight BTFR, involves a hitherto ignored transparent component of the energy-momentum tensor. As emphasized throughout the paper, the

A-field away from a non-uniformly moving particle (almost solving Maxwell’s equations in vacuum) necessarily involves both advanced and retarded radiation. Thus even matter at absolute zero constantly `radiates’, with advanced fields compensating for (retarded) radiation loss, thereby facilitating zero-point motion of matter. The

A-field at spacetime point

away from neutral matter is therefore rapidly fluctuating, contributed by all matter at the intersection of its worldline with the light-cone of

. We shall refer to it as the Zero Point Field (ZPF), a name borrowed from Stochastic Electrodynamics although it does not represent the very same object. Being a radiation field, the ZPF envelopes an isolated body with an electromagnetic energy `halo’, decaying as the inverse distance squared—which by itself is not integrable!—merging with other halos at large distance. Such `isothermal halos’ served as a basis for a `transparent matter’ model in a previous work by the author [

2] but in the current context its intensity likely needs to be much smaller to fit observations. Space therefore hosts a non-uniform ZPF peaking where matter is concentrated, in a way which is sensitive to both the type of matter and its density. This sensitivity may result both in an intrinsic scatter of the BTFR, and in a systematic departure from ZPF-free slope=3 at lower mass. Indeed, in heavy galaxies, typically having a dominant massive center, the contribution of the halo to the enclosed mass at

is tiny. Beyond

orbiting masses transition to their scaling regime, minimally influenced by additional increase in the enclosed mass at

r. The situation is radically different in light, diffuse galaxies, where the ratio of

is much higher throughout the galaxy, and much more of the non-integrable tail of the halo contributes to the enclosed mass at the point where velocity tracers transition to their scaling regime. This under estimation of the effective galactic mass, increasing with decreasing baryonic mass, would create an illusion of a BTFR slope greater than 3.

3.2.2. Other Probes of `Dark Matter’

Disc galaxies are a fortunate case in which the worldline of a body transitions from scaling to coarsening at a common scale along its entire worldline (albeit different scales for different bodies). They are also the only systems in which the velocity vector can be inferred solely from its projection on the line-of-sight. In pressure supported systems, e.g., globular clusters, elliptical galaxies or galaxy clusters, neither is true. Some segments of a worldline could be deep in their scaling regime while others in the coarsening, rendering the analysis of their collective scale flow more difficult. One solution strategy leverages the fact that, all the worldlines of a bound system are deep in their coarsening regime at sufficiently large scale, where their fixed-

dynamics is well approximated using Newtonian gravity. Starting with such a Newtonian system at sufficiently large

, the integration of (

54) to small

is in its stable direction, hence not at risk of exploding for any initial choice of Newtonian paths. If the Newtonian system at

is chosen to be virialized, a `catalog’ of solutions of pressure supported systems extending to arbitrarily small

can be generated, and compared with line-of-sight velocity projections of actual systems. As remarked above, the transition from coarsening to scaling generally doesn’t take place at a common scale along the worldline of any single member of the system. However, if we assume that there exists a rough transition scale,

, for the system as a whole in the statistical sense, which is most reasonable in the case of galaxy clusters, then immediate progress can be made. Since in the scaling regime velocities are unaltered, the observed distribution of the line-of-sight velocity projections should remain approximately constant for

, that of a virialized system, viz., Gaussian of dispersion

. On the other hand, at

a virialized system of total mass

M satisfies

where

is the velocity dispersion, and

r is the radius of the system, which is just (

61) with

. On dimensional grounds it then follows that

would be the counterpart of

from (

64), implying

which is in rough agreement with observations. The proportionality constant can’t be exactly pinned using such huristic arguments, but its observed value is on the same order of magnitude as that implied by (

64).

Applying our model to gravitational lensing in the study of dark matter requires better understanding of the nature of radiation. This is murky territory even in conventional physics and in next section initial insight is discussed. To be sure, Maxwell’s equations in vacuum are satisfied away from

, although only `almost so’, as discussed in

Section 3. However, treating them as an initial value problem, following a wave-front from emitter to absorber is meaningless for two reasons. First, tiny,

local deviations from Maxwell’s equations could become significant when accumulated over distances on the order of

. Second, in the proposed model extended particles `bump into one another’ and their centers jolt as a result—some are said to emit radiation and other absorb it, and an initial-value-problem formulation is, in general, ill-suited for describing such process. Nonetheless, incoming light—call it a photon or a light-ray—does posses an empirical direction when detected. In flat spacetime this could only be the spatial component of the null vector connecting emission and absorption events, as it is the only non arbitrary direction. A simple generalization to curved spacetime, involving multiple, freely falling observers, selects a path,

, everywhere satisfying the

light-cone condition. Every null geodesic satisfies the light-cone condition, but not the converse. In ordinary GR, the only non arbitrary path connecting emission and absorption events which respects the light-cone condition and locally depends on the metric and its first to derivatives is indeed a null geodesic. In our model, a solution of (

56) which is well behaved on all scales, further satisfying the light-cone condition for

, is an appealing candidate: It becomes a null geodesic at large scales, while the scaling operator alone preserves the light-cone condition.

Furthermore, in GR the deflection angle of a light ray due to gravitational lensing, by a compact gravitating system of mass

M, is

, where

R is the impact parameter. When

is in its scaling regime, our model’s

remains constant. If the system is likewise in its scaling regime, (

66) implies that its virial mass,

, scales according to

, as does the impact parameter of

,

. The conventional mass estimate based on the virial theorem, of this

-dependent family of gravitating systems, would then agree with that which is based on (conventional) gravitational lensing,

, up to a constant, common to all members—recall that this entire family appears in the `catalog’ of

systems. Extending this family to large

, the two estimates will coincide by construction. Thus if the system and

transition approximately at a common

, this proportionality constant can only be close to 1. This is apparently the case in most observations pertaining to galaxy clusters. Nonetheless, the two methods according to our model need not, in general, produce identical results. The degree to which they disagree depends on the exact scale-flow of

, which is one of those calculations avoided thus far, involving a path non-uniformly (in scale) transitioning from coarsening to scaling.

A final caveat regarding the application of (

56) to imaging, is that it is not clear whether the light-cone condition is automatically satisfied by all paths thus defined or that it should be imposed as an additional constraint. Nor is it even obvious that this condition must be satisfied exactly. In trying to figure this out one should remember that, in general, solutions of (

56) that are well behaved on all scales are not solutions of any o.d.e. in

for a fixed

.

3.3. Quantum Mechanics as a Statistical Description of the Realistic Model

The basic tenets of classical electrodynamics (

19), (

29) and (

30), which must be satisfied at

any scale on consistency grounds (up to neglected curvature terms), strongly constrain also statistical properties of ensembles of members in

, and in particular constant-

sections thereof. In a previous paper by the author [

1] it was shown that these constraints could give rise to the familiar wave equations of QM, in which the wave function has no ontological significance, merely encoding certain statistical attributes of the ensemble via the various currents which can be constructed from it. It is through this statistical description that

ℏ presumably enters physics, and so does `spin’ (see below).

This somewhat non-committal language used to describe the relation between QM wave-equations and the basic tenets is for a reason. Most attempts to provide a realist (hidden variables) explanation of QM follow the path of statistical mechanics, starting with a single-system theory, then postulating a `reasonable’ ensemble of single-systems—a reasonable measure on the space of single-system solutions—which reproduces QM statistics. Ignoring the fact that no such endeavor has ever come close to fulfillment, it is rarely the case that the measure is `natural’ in any objective way, effectively

defining the statistical theory/measure (uniformity over the impact parameter in an ensemble representing a scattering experiment being an example of an objectively natural attribute of an ensemble). Even the ergodicity postulate, as its name suggests, is a postulate—external input. When sections of members in

are the single-systems, the very task of defining a measure on such a space, let alone a natural one, becomes hopeless. The alternative approach adopted in [

1] is to derive constraints on any statistical theory of single-systems respecting the basic tenets, showing that QM non-trivially satisfies them. QM then, like any measure on the space of single-system solutions, is

postulated rather than derived, and as such enjoys a fundamental status, on equal footing with the single-system theory. Nonetheless, the fact that the QM analysis of a system does not require knowledge of the system’s orbit makes it suspicious from our perspective. And since a quantitative QM description of any system but the simplest ones involves no less sorcery than math, that fundamental status is still pending confirmation (refutation?).

Of course, the basic tenets of classical electrodynamics are respected by all (sections of-) members of

, not only those associated Dirac’s and Schrödinger’s equations. The focus in [

1] on `low energy phenomena’ is only due to the fact that certain simplifying assumptions involving the self-force can be justified in this case. In fact, the current realization of the basic tenets, involving fields only instead of interacting particles, is much closer in nature to the QFT statistical approach than to Schrödinger’s.

3.3.1. The Origin of Quantum Non-Locality

“Multiscale locality", built into the proposed formalism, readily dispels one of QM’s greatest mysteries—its apparent non-local nature. In a nutshell: Any two particles, however far apart at our native scale, are literally in contact at sufficiently large scale.

Two classic example where this simple observation invalidates conventional objections to local-realist interpretations of QM are the following. The first is a particle’s ability to `remotely sense’ the status of the slit through which it does not pass, or the status of the arm of an interferometer not traversed by it (which could be a meter away). To explain both, one only needs to realize that for a giant physicist, a fixed-point particle is scattered from a target not any larger than the particle itself, to which he would attribute some prosaic form-factor; At large enough the particle literally passes though both arms of the interferometer (and through none!). This global knowledge is necessarily manifested in the paths chosen by it at small . Of course, at even larger the particle might also pass through two remote towns etc., so one must assume that the cumulative statistical signature of those infinitely larger scales is negligible. A crucial point to note, though, is that the basic tenets, which imply local energy-momentum conservation at laboratory scales, are satisfied at each separately. For this large- effect to manifest at , local energy-momentum conservation alone must not be enough to determine the particle’s path, which is always the case in experiment manifesting this type of non-locality. Inside the crystal serving as mirror/beam-splitter in, e.g., a neutron interferometer, the neutron’s classical path (=paths of bulk-motion derived from energy-momentum conservation) is chaotic. Recalling that, what is referred to as a neutron—its electric neutrality notwithstanding—only marks the center of an extended particle, and that the very decomposition of the A-field into particles is an approximation, even the most feeble influence of the A-field awakened by the neutron’s scattering, traveling through the other arm of the interferometer, could get amplified to a macroscopic effect. This also provides an alternative, fixed-scale explanation for said `remote sensing’. In the double-slit experiment such amplification is facilitated by the huge distance of the screen from the slits compared with their mutual distance.

The second kind of non-locality is demonstrated in Bell’s inequality violations. As with the first kind, the conflict with one’s classical intuition can be explained both at a fixed scale, or as a scale-flow effect. Starting with the former, and ever so slightly dumbing down his argument, Bell assumes that physical systems are small machines, with a definite state at any given time, propagating (deterministically or stochastically) according to definite rules. This generalizes classical mechanics, where the state is identified with a point in phase-space and the evolution rule with the Hamiltonian flow. However, even the worldlines of particles in our model, represented by sections of members in

, are not solutions of any (local) differential equation in time. Considering also the finite width of those worldlines, whose space-like slices Bell would regard as possibly encoding their `internal state’, it is clear that his modeling of a system is incompatible with our model; particles are not machines, let alone particle physicists. Spacetime `trees’ involved in Bell’s experiments—a trunk representing the two interacting particles, branching into two, single particle worldlines—must therefore be viewed as a single whole, with Bell’s inequality being inapplicable to the statistics derived from `forests’ of such trees.

4 This spacetime-tree view gives rise to a scale-flow argument explaining Bell’s inequality violations: The two branches of the tree shrink in length when moving to larger scale, eventually merging with the trunk and with one another. Thus the two detectors at the endpoints of the branches cannot be assumed to operate independently, as postulated by Bell.

3.3.2. Fractional Spin

Fractional spin is regarded as one of the hallmarks of quantum physics, having no classical analog, but according to [

1], much like

ℏ, it is yet another parameter—discrete rather than continuous—entering the statistical description of an ensemble. At the end-of-the-day, the output of this statistical description is a mundane statement in

, e.g., the scattering cross-section in a Stern-Gerlach experiment, which can be rotated with

. Neither Bell’s- nor the Kochen-Specker theorems are therefore relevant in our case as the spin is not an attribute of a particle. For this reason the spin-0 particle from

Section 3.1.2 is a legitimate candidate for a fractional-spin particles, such as the proton, for its `spin measurement/polarization’ along some axis is by definition a dynamical happening, in which its extended world-current bends and twists, expands and contracts in a way compatible with- but not dictated by the basic tenets. As stressed above, there is no natural measure on the space of such objects, and the appearance of two strips on Stern

Gerlach’s plate rather than one, or three etc. need not have raised their eyebrows. Nonetheless, the proposed model does support spinning solutions, viz.

in the rest frame of the particle, and there is a case to be made that those are more likely candidates for particles normally attributed with a spin, integer or fractional.

3.3.3. Photons and Neutrinos (or Illusion Thereof?)

Einstein invented the `photon’ in order to explain the apparent violation of energy conservation occurring when an electron is jolted at a constant energy from an illuminated plate even when the plate is placed far enough from the source, such that the time-integrated Poynting flux across it becomes smaller than that of the jolted electron. It is entirely possible that Einstein’s explanation can be realized in the proposed formalism, although the rest-frame analysis of a fixed-point particle from

Section 3.1.2 must obviously be modified for massless (neutral) particles which might further require extending

and

to include distributions. Maxwell’s equations would then act as the photonic counterpart of a massive-particle’s QM wave equation, describing the statistical aspects of ensembles of photons. Indeed, since in a `lab’ of dimension

individual photons (almost) satisfy the basic tenets of classical electrodynamics (and (

31)) for a chargeless current (i.e.,

), the construction from [

1] would result in Maxwell’s equations, with the associated

being the ensemble energy-momentum tensor. However, since the

A-field (almost) satisfies Maxwell’s equations regardless of it being a building block of photons, it is highly unlikely that photons exhaust all radiation-related phenomena. For example, is there any reason to think that a radio antenna transmits its signal via radio photons, rather than radio (

A-) waves? This suggests an alternative explanation for photon-related phenomena, which does not require actual, massless particles. Its gist is that, underlying the seeming puzzle motivating Einstein’s invention of the photon, is the assumption that an electron’s radiation field is entirely retarded which, as emphasized throughout the paper, cannot be the case for the

A-field. Advanced radiation converging on the electron could supply the energy necessary to jolt it, further facilitating violation of Bell’s inequality in entangled `photons’ experiments. This proposal, first appearing in [

1] and further developed in [

2], was, at the time, the only conceivable realist explanation of photon related phenomena. In the proposed model, apparently capable of representing `light corpuscles’, it may very well be the wrong explanation. Photons would then be just ephemeral massless particles created in certain structural transitions of matter, then disappearing when detected. Note that these two processes are entirely mundane, merely representing a relatively rapid changes in

and

at the endpoints of a photon’s (extended) worldline. Such unavoidable transient regions might result in an ever-so-slight smoothing of said distributions, which are otherwise excluded from

.

“God is subtle but not malicious" was Einstein’s response to claims that further repetitions of the Michelson-Morley experiment did show a tiny directional dependence of the speed of light. This attitude is adopted vis-a-vis the neutrino’s mass problem. All direct measurements based on time-of-flight are consistent with the neutrino being massless; the case for a massive neutrino relies entirely on indirect measurements and a speculative extension of the Standard Model. Neutrinos would then be quite similar to photons, only probably spinning (

), whose creation and annihilation involve structural transitions at the subatomic scale. However, as with photons, and even more so due to their elusiveness, neutrinos might not be the full story, or even the real one. The classical model of photons cited above assumes that only

contributes to the radiative

which is therefore identified with

. In the proposed model

consists also of

with

satisfying (

31) in the flat spacetime approximation, rewritten here

This is a massless wave equation, not too dissimilar to Maxwell’s, therefore expected to participate in radiative, energy-momentum transfer. However, two features set it apart. First, the two terms on the l.h.s. of (

31) enter with the `wrong’ relative sign, spoiling gauge covariance. As a result an extra longitudinal mode exists, i.e.,

with

(which in the Maxwell case is a pure gauge), on top of the two transverse modes,

. Second, unlike

,

is only linear in

, an impossibility for a Noether current. Combined, these two features imply that only the longitudinal mode can radiate energy-momentum and only during transient, `structural changes’ to the radiating system. Indeed, consider the integral of the energy flux of

over

in

Figure 1.

where

is a large sphere centered at the location of the system and

is an outward pointing vector orthogonal to

of length

. Clearly, only the longitudinal mode, whose energy flux at each point on

is

, contributes to the integral (

67). Moreover, we saw in

Section 3.1.1 that outside of fixed-points,

must be negligible. So long as the system qualifies as a fixed-point, as during bulk acceleration, no net flux is being generated by it, and it is therefore only while transitioning between distinct fixed-points that

is involved in energy changes (and even then only its

piece—

r being the radial coordinate when

and the system are co-centered at the origin—as the

piece integrates to zero over time). The

Z-field is therefore a natural candidate for a `classical neutrino field’, whose relation to neutrino phenomena parallels that of the

A-field to photon phenomena. As with photons, it is a particle’s advanced

Z-field converging on it which supplies the energy-momentum necessary to jolt it, conventionally interpreted as the result of being struck by a neutrino. Similarly, hitherto ignored retarded

Z-field is allegedly generated in structural changes of a system, e.g., when nuclei undergo

-decay. As pointed out in

Section 3.3.2 above, the (fractional) spin-

attributed to the neutrino, as is the spin-1 of the photon, only labels the statistical description of phenomena involving such jolting of charged particles.

3.4. Cosmology

Cosmological models are stories physicists entertain themselves with; they can’t truly know what happened billions of years ago, billions of light-years away, based on the meager data collected by telescopes. Moreover, in the context of the proposed model, the very ambition implied by the term “cosmology" is at odds with the humility demanded of a physicist, whose entire observable universe could be another physicist’s microwave oven. On the other hand, astronomical observations associated with cosmology, also serve as a laboratory for testing `terrestrial’ physical theories, e.g., atomic-, nuclear-, quantum-physics, and this would be particularly true in our case, where the large and the small are so intimately interdependent. When the most compelling cosmological story we can devise requires contrived adjustments to terrestrial-physics theories, confidence in those, including GR, should be shaken.

Reluctantly, then, a cosmological model is outlined below. Its purpose at this stage is not to challenge

CDM in the usual arena of precision measurements, but to demonstrate that it plausibly avoids the aforementioned flaw, while also addressing the infamous dipole problem [

9], which undermines the very foundations of any Friedmann cosmological model.

3.4.1. A Newtonian Cosmological Model

As a warm-up exercise, we wish to solve the system (

54)(

45) for a spherical, uniform, expanding cloud of massive particles originating from the scaling center (without loss of generality), described by

where

n is a particle index,

a constant vector, and

are uniformly distributed when averaged over a large enough volume. It is easily verified that the same homogeneous expanding cloud would appear to an observer fixed to any particle, not just the one at the origin. The mass density of the cloud depends on

a via

, retaining its uniformity at any time and scale. The gravitational force acting on particle

n is given by

(the uniform vacuum energy is ignored as its contribution to the force can only vanish by symmetry) and (

54) gives a single, particle-independent equation for

a

with

etc.

Two types of solutions for (

69) that are well behaved on all scales should be distinguished: Bounded and unbounded. In the former

becomes arbitrarily small

at sufficiently large

, and is identically zero at

and a

-dependent `big-crunch’ time,

. By our previous remarks, at large scale the coarsening terms—those multiplied by

on the r.h.s. of (

69)—dominate the flow and must almost cancel each other or else

a would rapidly blow up with increasing

. The resulting necessary condition for a regular

on all scales is a

-dependent o.d.e. in time, which is simply the time derivative of the (first) Friedmann equation for non-relativistic matter

Note that

k disappears as a result of this derivative, meaning that it resurfaces as a second integration constant of any magnitude—not just

. During the flow of

to large

,

k increases without bound, and as a consequence

shrinks to zero for

. In other words, as

grows the initial explosion becomes increasingly less energetic—as evaluated at some fixed, small

to avoid a trivial infinity. Given a solution of (

70) at large enough

one can then integrate (

69) in its stable, small

direction, where the scaling piece becomes important, but due to the

constraint, some parts of a solution remain deep in their coarsening regime. The same is true for unbounded solutions, but in this case there is no

to start from. This renders the task of finding solutions more difficult, which is addressed below, in the appropriate, relativistic context.

The Newtonian-cloud model, while mostly pedagogical, nonetheless captures the way cosmology is to be viewed within the proposed framework: It does not pertain to the Universe but rather to a universe—an expanding cloud as perceived by a dwarf amidst it. A relative giant, slicing the cloud’s orbit at a much larger , might classify the corresponding section as the expanding phase of a Cepheid, or that of a red-giant, supernova, etc. An even mightier giant may see a decaying radioactive atom. Of course, matter must disappear in such flow to larger and larger scales—a phenomenon already encountered in the linear case which is further discussed below. A simplifying aspect of the proposed formalism already exploited in the case of galaxies is that dynamical aspects of small- sections can be analyzed independently of those large- sections. However, one must not lose sight of the orbit view. For example, a possible singularity at should not be interpreted as “the beginning of time" or what have you, but merely the breakdown of the dwarf’s phenomenological description of his section.

Suppose for concreteness that a giant’s section is an expanding star. The dwarf’s entire observable universe would in this case correspond to a small sphere, non-concentrically cut from the star. The hot thermal radiation inside that sphere at

, after flowing with (

16) to

, would be much cooler, much less intense, and much more uniform, except for a small dipole term pointing towards the star’s center, approximaely proportional to the star’s temperature gradient at the sphere, multiplied by the sphere’s diameter. Similarly for the matter distribution at

, only in this case the distribution of accumulated matter created during the flow is expected to decrease in uniformity if new matter is created close to existing matter. Thus the distribution of matter at

is proportional to the density at

only when smoothed over a large enough ball, whose radius coresponds to a distance at

much larger than the scale of density fluctuations. This would elegantly explain the so-called dipole problem [

9]—the near perfect alignment of the CMB dipole with the dipole deduced from matter distribution, but with over

discrepancy in magnitude; Indeed, the density and temperature inside a star typically have co-linear, inward-pointing gradients, but which differ in magnitude. Note that a uniform cloud ansatz is inconsistent with the existence of such a dipole discrepancy and should therefore be taken as a convenient approximation only, rendering the entire program of precision cosmology futile. The horizon problem of pre inflation cosmology is also trivially explained away by such orbit view of the CMB. Similarly, the tiny but well-resolved deviations from an isotropic CMB (after correcting for the dipole term) might be due to acoustic waves inside the star.

Returning to the scale-flow of interpolating between `a universe’ and a star, and recalling that stands for a spacetime phenomenon as represented by a physicist of native scale s, a natural question to ask is: What would this physicist’s lab notes be? A primary anchor facilitating this sort of note-sharing among physicists of different scales is a fixed-point particle, setting both length and mass standard gauges. We can only speculate at this stage what those are, but the fact that the mass of macroscopic matter must be approximately scale invariant—or else rotation curves would not flatten asymptotically—makes atomic nuclei, where most of the mass is concentrated, primary candidates. Note that in the proposed formalism the elementarity of a particle is an ill-defined concept, and the entire program of reductionism must be abandoned. For if zooming into a particle were to `reveal its structure’, even a fixed-point would comprise infinitely many copies of itself as part of its attraction basin.

If nuclei approximately retain their size under scale-flow to large , while macroscopic molecular matter shrinks, a natural question to ask is: What aspects of spacetime physics (at a fixed-scale section) have changed? Instinctively, one would attribute the change to a RG flow in parameter space of spacetime theories, e.g., the Yukawa couplings of the Standard Model of particle physics, primarily that of the electron. However, this explanation runs counter to the view advocated in this paper, that (spacetime) sections should always be viewed in the context of their (scale) orbit; If the proposed model is valid, then the whole of spacetime physics is, at best, a useful approximation with a limited scope. Moreover, an RG flow in parameter space cannot fully capture the complexity involved in such a flow, where, e.g., matter could annihilate in scale (subject to charge conservation); `electrons’ inside matter, which in our model simply designate the A-field in between nuclei—the same A-field peaking at the location of nuclei—`merging’ with those nuclei (electron capture?); atomic lattices, whose size is governed by the electronic Bohr radius , might initially scale, but ultimately change structure. At sufficiently large an entire star or even a galaxy would condense into a fixed-point—perhaps a mundane proton, or some more exotic black-hole-like fixed-point which cannot involve a singularity by definition. Finally, we note that, by definition, the self-representation of that scaled physicist slicing at his native scale s, is isomorphic to ours, viz., he reports being made of the same organic molecules as we are made of, which are generically different from those he observes, e.g., in the intergalactic medium. So either actual physicists (as opposed to hypothetical ones, serving as instruments to explain the mathematical flow of ) do not exist in a continuum of native scales, only at those (infinitely many) scales at which hydrogen atoms come in one and the same size; or else they do, in which case we, human astronomers, should start looking around us for odd-looking spectra, which could easily be mistaken for Doppler/gravitational shifts.

3.4.2. Relativistic Cosmology

In order to generalize the Newtonian-cloud universe to relativistic velocities, while retaining the properties of no privileged location and statistical homogeneity, it is convenient to transfer the expansion from the paths of the particles to a maximally symmetric metric—a procedure facilitated by the general covariance of the proposed formalism. Formally, this corresponds to an `infinite Newtonian cloud’ which is a good approximation whenever the size of the cloud and the distance of the observer from its edge are both much greater than

and

. Consider first a spatially flat (

in the FLRW metric), maximally symmetric space, with metric

for which the only non-vanishing Christoffel symbols are

The gravitational part of the scaling field,

, appropriate for the description of a universe which is electrically neutral on large enough scales, i.e.,

, is given by solutions of the homogeneous, generally covariant counterpart of (

31)

However, the generally covariant boundary condition (

32) “far away from matter" is not applicable here. Instead,

is required to be compatible with the (maximal) symmetry of space—its Lie derivative along any Killing field of space must vanish. Such a scaling field is readily verified to be just naive scaling

No generalization exists for a FLRW metric. A formal proof will be provided elsewhere, but for the reader can easily be convinced by (unsuccessfully) trying to visualize such a field on a sphere. The flatness problem of pre-inflation cosmology is thus solved.

Calculating the metric-flow (

23) for the above, maximally symmetric metric and associated scaling field is somewhat more subtle than the transition from EFE to cosmology. The energy-momentum tensor on its r.h.s. of EFE is a phenomenological device, equally valid whether applied to the hot plasma inside a star or to the `cosmic fluid’. In contrast,

and the scaling field from which

is derived, both enter (

23) as fundamental quantities, on equal footing with

. To make progress, this fundamental status must be relaxed, and

is to be seen as the phenomenological

in standard cosmology—a step that can be made fairly rigorous. Specifically, for

, with

the scaling field inside matter, we shall use a maximally symmetric ansatz

with

and

p incorporating

and

, while the remaining terms are entirely due to

. Plugging (

74) and (

71) into the metric flow (

23), results in space-space and time-time components given, respectively, by

which can be combined to

Another equation which can be extracted from those two, or directly from energy-momentum (non-)conservation (

27) is

Only two of the above equations are independent due to the Bianchi identity.

Equation (

77) is just (

69) for

, but with five differences:

- (a)

, which is due to the fact that different flow equations are involved.

- (b)

; Since the paths of co-moving masses can be deduced by analytically continuing solutions of (

23),

, and solving (

56) in the resultant metric, we might as well solve the above equations directly for

.

- (c)

A cosmological constant term,

, appears, corresponding to a

positive cosmological constant

; it would have made it into the Newtonian equations had the

negative energy density appearing in the Newtonian approximation (

39) been included in

(which, as remarked above, is not a valid step to take within the Newtonian approximation).

- (d)

The scaling term

is missing from (

77); its absence can be understood as follows: Solving (

56) in the metric (

71) and using (

72) it is readily verified that

,

is a solution. Now, unlike in (

56),

is

not the proper distance between two particles, viz., the minimal number of fixed-point-standard-length-gauges exactly fitting between them (that this is so in the former is not entirely trivial to show). Instead, it is

. Assuming that the number of particles is conserved in both time and scale as in the Newtonian model, we also have

. Setting

in (

77) and substituting

, restores the scaling term, written now for the proper metric scale-factor

.

- (e)

Proviso

in (

70) must be dropped as it is inconsistent with (

78) (see next).

As in standard cosmology, solutions of the Friedmann equations require additional physical input regarding the nature of the energy-momentum tensor, e.g., an equation of state relating p and . In the proposed model, both and p represent some large-volume average of removed of ’s trivial cosmological constant component. The contribution from inside matter (where ), denoted , is assumed to be that of non-relativistic (“cold") matter, i.e., . Outside matter the A-field is nearly a vacuum solution of Maxwell’s equations with an associated traceless contributing and to the total and p. The scaling field, , outside matter, which is responsible for the cosmological constant, might have an additional, radiative contribution to which is neglected due to being oscillatory and linear in —the cosmological constant being the sole survivor of a volume average. If we proceed as usual, identifying with the energy of retarded radiation emitted by matter, observations would then imply in the current epoch. However, incorporates also the ZPF which could outweigh . The contribution of the ZPF, being an `extension’ of matter outside the support of its , although having a distinct dependence, is not an independent component. Properly modeling the relation between the two would likely require a deeper dive into details.

Once the physics behind

and

p is understood, the computational challenge is well-defined: Finding

such that when propagated in scale to large-

with (

77) does not rapidly diverge. In so propagating

one needs to

This conceptually straightforward but numerically challenging approach will be attempted elsewhere, but some progress can still be made. Since the Friedman equation (

76) is satisfied (also) at

, reasonably assuming that

is on the order of the current baryonic density based on direct `count’,

, most likely a lower bound, Friedman’s equation (

76) mandates

(Note that

is assumed, which is a standard practice in cosmology, equivalent to `absorbing’

into the definition of the standard length gauge). With such a large

, (

78), rewritten

with the scaled-time scale factor,

, implies almost energy conservation, but not quite. Indeed, building on our experience from galactic solutions which implies

, the r.h.s. represents a tiny rate of energy gain which could nevertheless become substantial when integrated over cosmological time scales. Since

is identically conserved outside of matter, such energy gain must involve matter creation. The arrow-of-time—both thermodynamic and radiation—might also stem from the time-asymmetry of (

80).

Deducing astronomical observations from a solution,

, entails extra steps, which must be modified in the proposed model. To calculate the redshift, two time-ordered points along the worldline of a distant, comoving standard clock are to be matched with similar two points on earth. The matching is done by finding two solutions of (

56) which are well behaved on all scales, satisfying the light-cone condition, connecting the corresponding points at

. Using (

71), the equation for

(assuming

without loss of generality) of such a light signal becomes

with

. Placing the origin of scaling now and here, on earth, a necessary condition for

to not rapidly diverge at large

when

is negligible, is for the expression in each bracket to almost vanish, viz.,

must be almost a geodesic, in which case solutions satisfying the light-cone condition are:

,

, parameterizing a trajectory

. Recalling that

, as long as

, such trajectories are nearly straight, unit-speed lines. But such lines are also exact solutions of the flow (

81)(

82) for the scaling part alone. It follows that for

straight lines connecting transmission and detection events are stable under the flow (

81)(

82) to large

, and therefore

is a good approximation for the redshift as prescribed above, vindicating standard estimates of

which are derived from local observations. At large redshifts our prescription would give a different result. Nonetheless, it is readily verified that the standard relation between the luminosity and angular-diameter distances,

, remains valid. In this regard the reader is reminded that

, where

L is the luminosity of an object and

is the measured flux, involving

only, is derived assuming exact energy conservation over cosmological times, viz., zero on the r.h.s. of (

80).