3.2. Films Deposited by CBD-HVEF-B

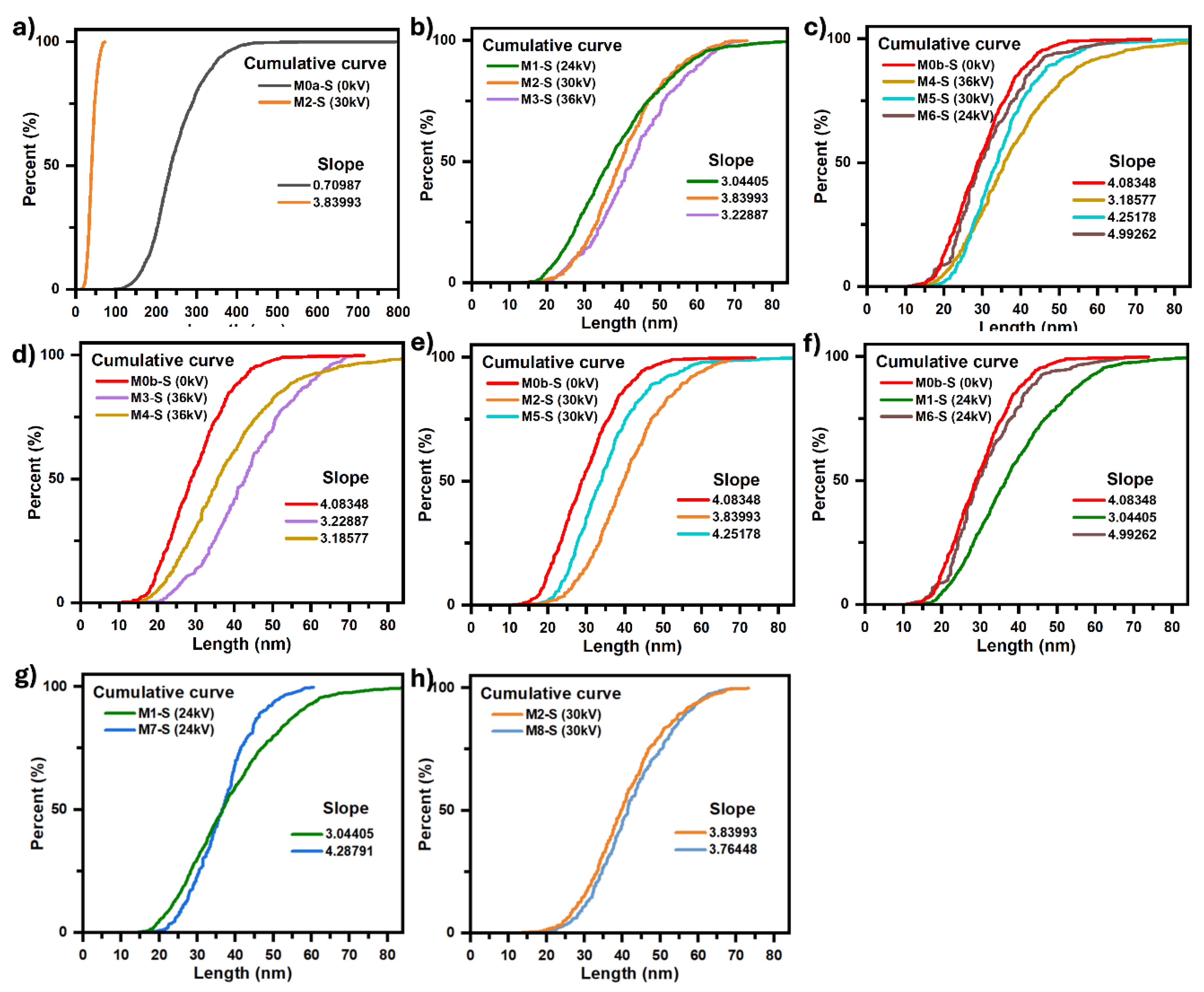

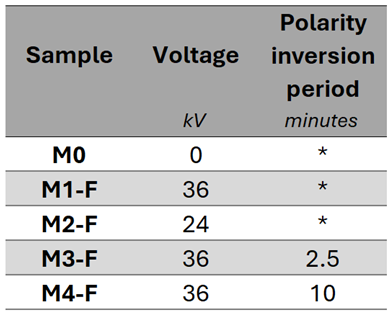

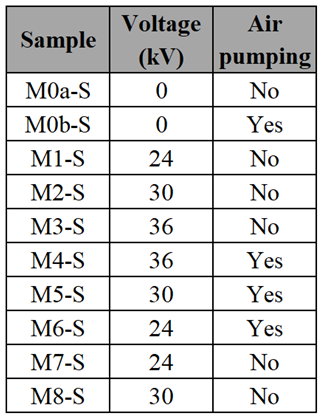

Figure 6 presents micrographs for samples obtained using the CBD-HVEF-B system, each labeled according to the corresponding sample listed in

Table 2. These micrographs showed homogeneity in the ZnO deposit as well as the fact that all the coatings were composed of nanometric-sized particles, except for M0a-S, which is the sample deposited by conventional CBD technique and was composed of submicrometric particles. Each micrograph has an insert with the percentage value of the substrate area coated by ZnO, obtained by a software developed by our research team, and employed in previous reports [

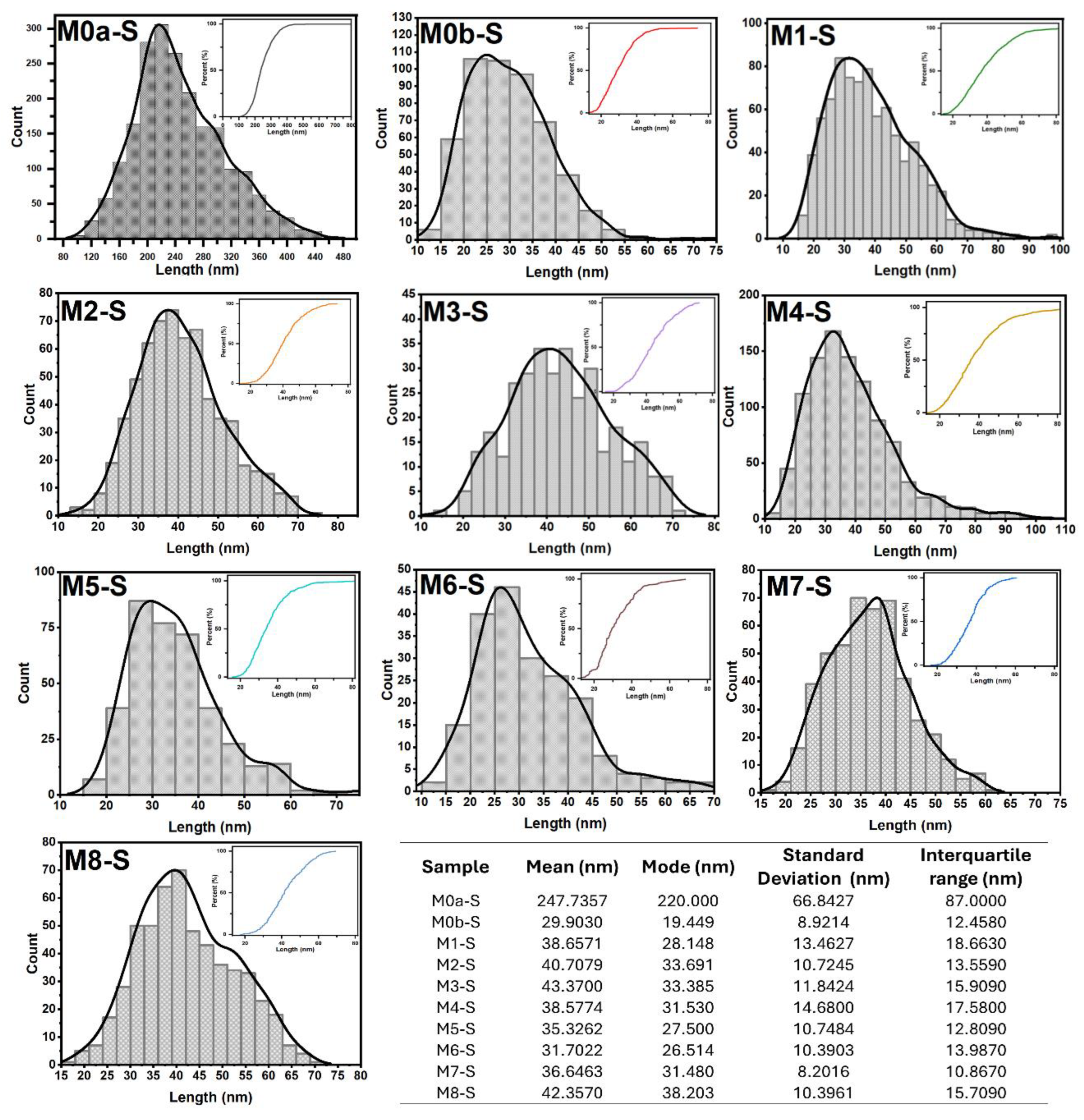

16]. The characteristic shape of the particles and the descriptive statistics of their sizes are presented in the table inserted in

Figure 7. The same figure also shows the particle size distribution functions for all the coatings, in correspondence with the micrographs in

Figure 6. There, next to each of the size distribution functions, their corresponding cumulative size curves are presented. The comparative analysis between the coatings, in terms of the shape and size of the particles that compose them, was carried out based on whether or not an electric field was used during the synthesis and whether or not the solution was stirred by injecting filtered air into it, in addition to the variation in its pH, thus resulting in eight comparative analyses between the coatings.

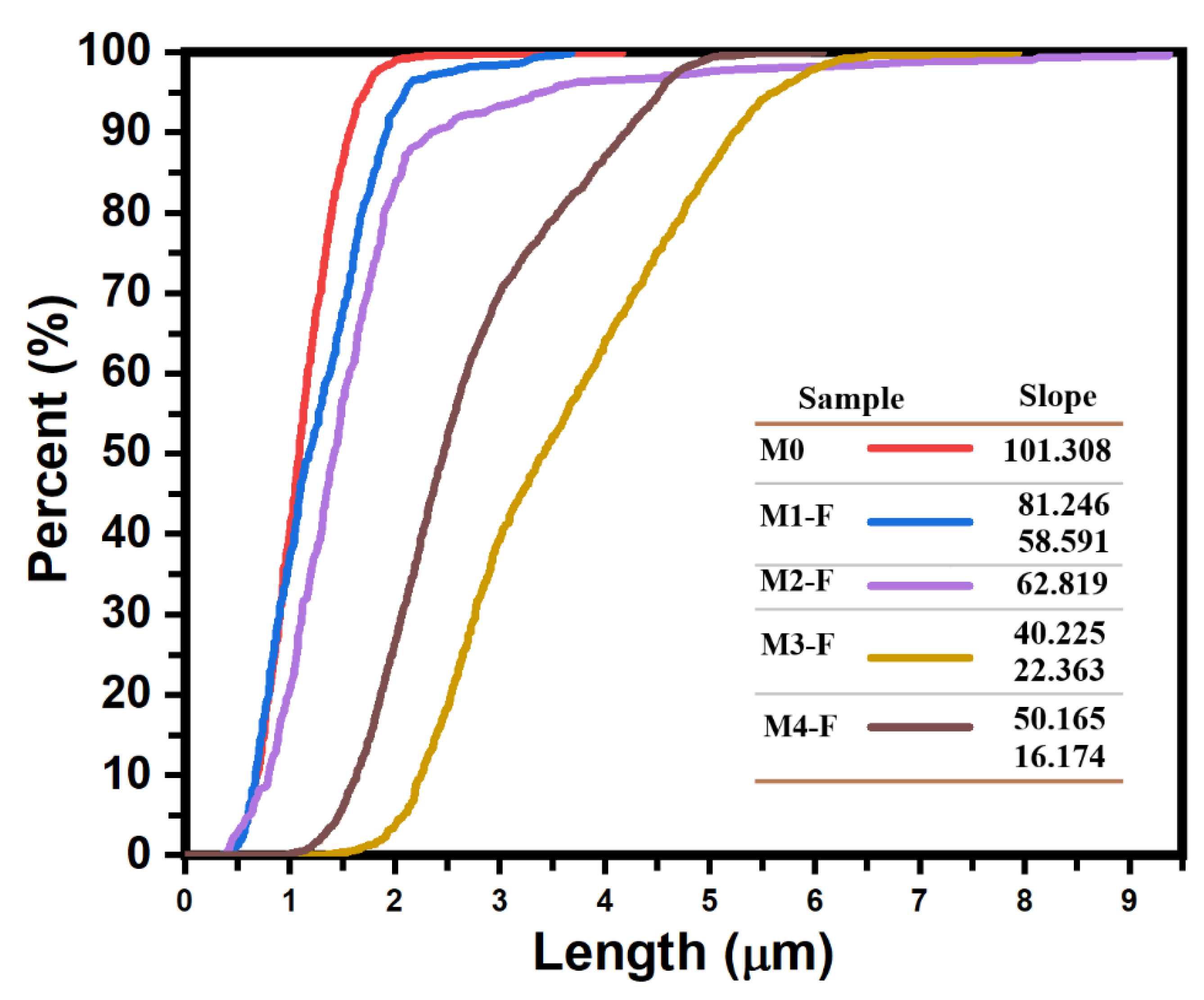

Figure 8 shows the different cumulative size curves of the coatings according to the comparative analysis in question. Likewise,

Figure 9 and

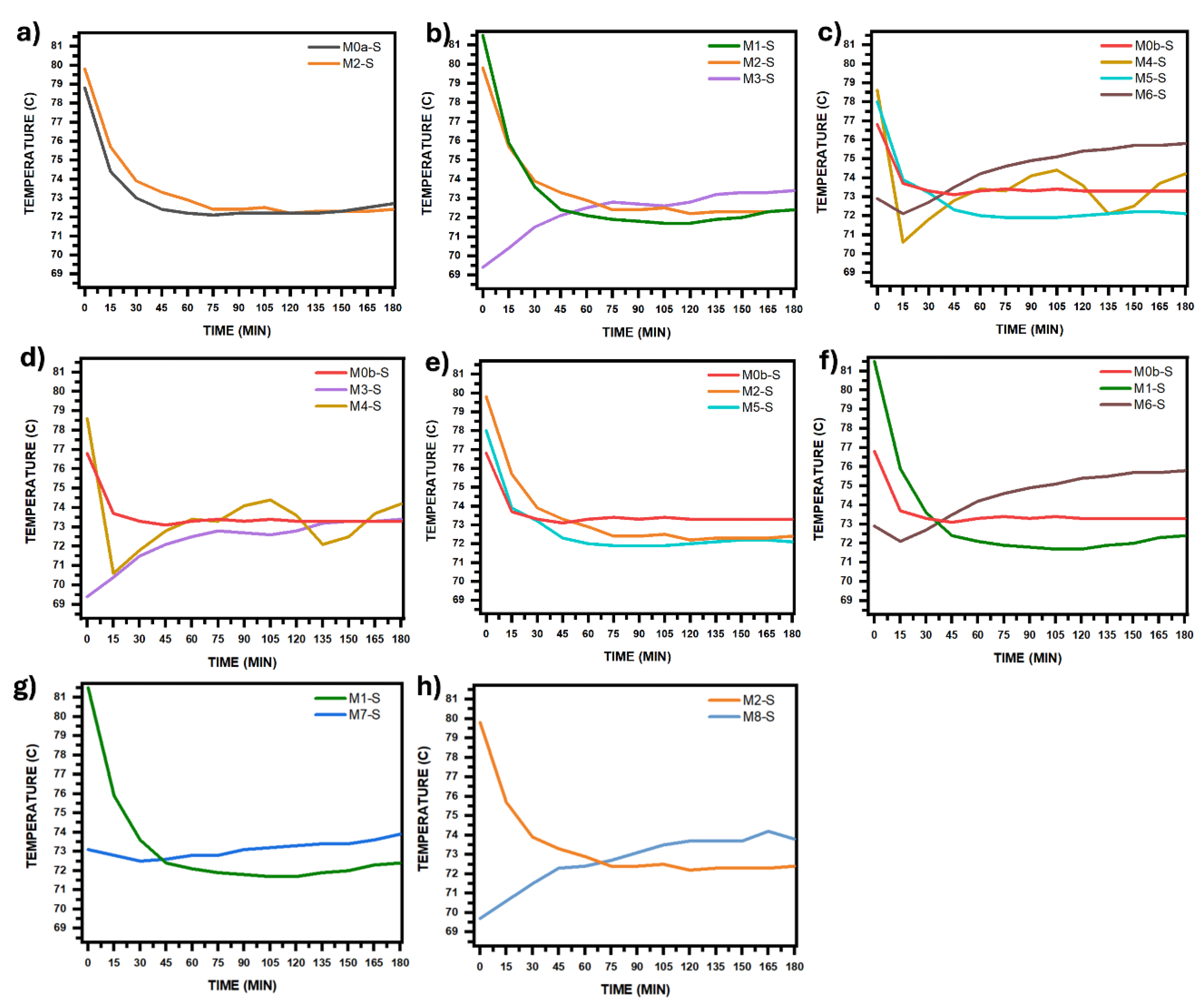

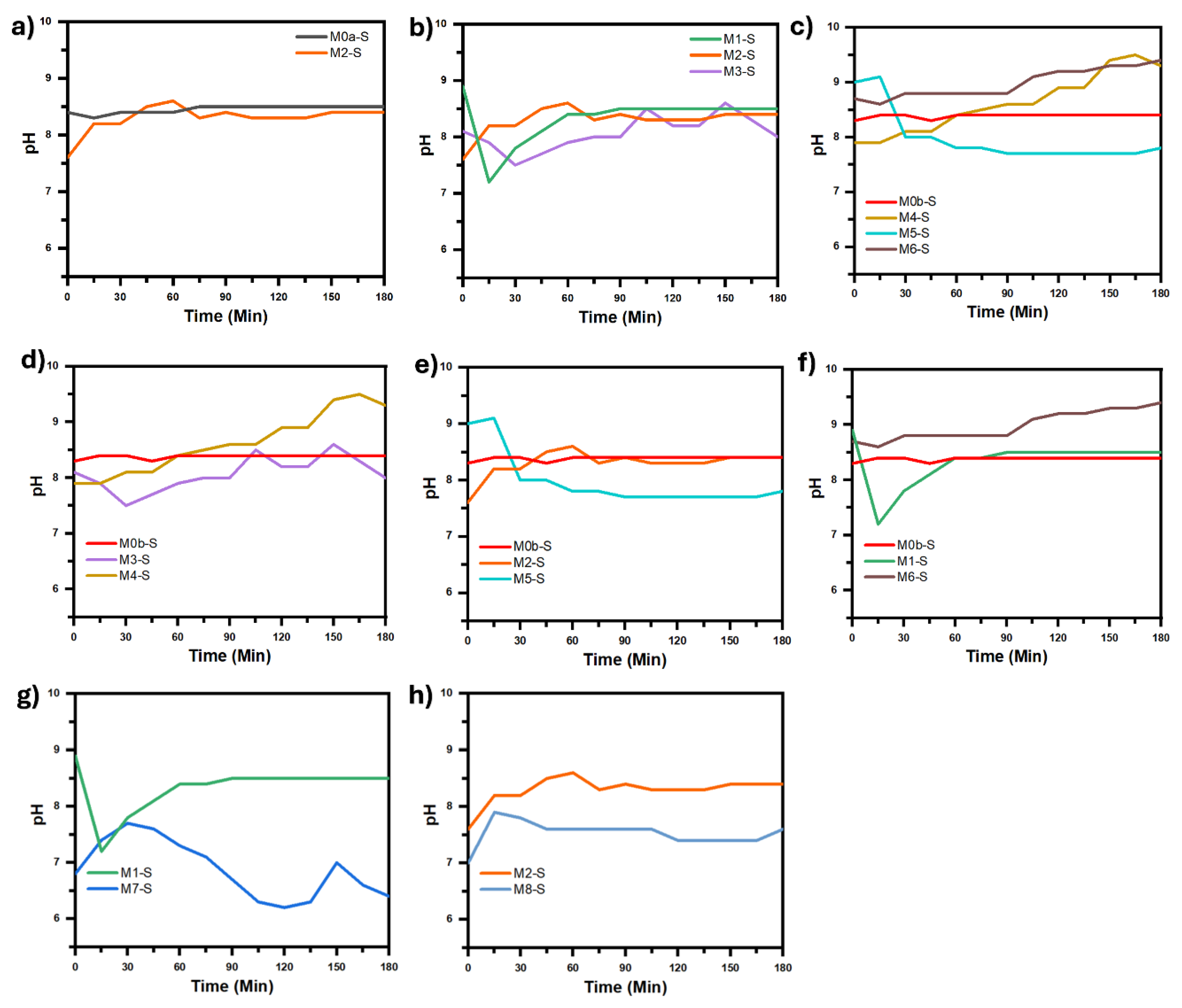

Figure 10 show the temperature and pH curves of the solution during synthesis process, corresponding to each comparative analysis in

Figure 8, this is in order to assess whether or not there are significant differences between the temperature and pH curves that should be considered for the corresponding analysis.

The comparison between micrographs of samples M0a-S and M2-S, figures 6a and 6d, respectively, clearly shows the influence of the electric field during the CBD synthesis process. It can be observed that the conventional CBD coating M0a-S covers only 10.33% of the ITO substrate surface, while the coating whose synthesis was assisted by the electric field (M2-S) covers 99.66% of the surface, as well as that the particles that make up the coating went from being bars of dimensions in the order of 247 nm with very well-defined edges in M0a-S to particles with rounded edges and practically no defined corners, the average dimensions for M2-S was 40.71 nm with a mode of 33.69 nm, thus reducing its size by 6 times (see table inserted in

Figure 7). This reduction in particle size is even better appreciated by comparing the cumulative size curves for both coatings, see

Figure 8a. Now, on the other hand, when comparing the micrographs for M0a-S and M0b-S coatings, figures 6a and 6b, respectively, both synthesized without an electric field, it can be seen that stirring the solution with injection of filtered air during the synthesis process has the effect of reducing the size of the particles that make up the coating, same effect as exposed above for when an electric field is applied, but in this case the particles achieved a greater reduction, up to 12 times their size, resulting in an average size of 29.90 nm and a mode of 19.45 nm (see table inserted in

Figure 7), in addition to retaining the morphology of bars with very well-defined edges, most of them growing perpendicular to the substrate surface, however; the area of the substrate that was covered by ZnO was smaller, around 60.46 %. In summary, applying an electric field or stirring the solution through the injection of filtered air led to a higher growth rate of ZnO and a reduction in the size of the particles that make up the coating, in addition to the fact that the electric field promoted the aggregation of the nanoparticles, which resulted in a much more compact coating.

Micrographs associated with coatings M1-S, M2-S and M3-S (figures 6c,d and e) were compared to study the effect of the electric field intensity on the coating morphology, this for electric fields produced by potential differences between electrodes of 24, 30 and 36 kV, respectively. It was observed that the morphology of the coatings was similar, independent of the field intensity, observing a nodular type growth followed by a coalescence process between particles. The degree of aggregation of the particles, as well as the percentage of the covered substrate area were greater for 30 kV, covering up to 99.66% of the substrate surface, while for 24 and 36 kV it was 88.31 and 58.22%, resulting in a coating with greater compactness for 30 kV. When comparing the cumulative particle size curves,

Figure 8b, it is observed that the particle size grows slightly by 16.9 % when the potential difference goes from 24 to 36 kV as well as a variation in the dispersion of their sizes, the latter is noticeable by the relative change in the slope of the curves (see values in the same figure), the dispersion being lower for 30 kV where the slope of the curve is greater, which is consistent with its interquartile range of 13.56 nm (see table in

Figure 7), while for the coatings obtained at 24 and 36 kV, the interquartile range was 18.66 and 15.91 nm, respectively.

To study the effect that the intensity of the electric field in combination with the injection of filtered air has on the coating morphology, micrographs for M4-S, M5-S and M6-S were compared for 36, 30 and 24 kV, respectively (see

Figure 6). It is observed that the nanoparticles that make up the coating seem to be composed of smaller particles with well-defined edges, which suggests a columnar type growth, unlike the nodular growth observed when only the electric field is applied. Likewise, it is also observed that the coating that now presents greater compactness is the one obtained at 36 kV and not at 30 kV as it was when the solution was not stirred with filtered air, and that the substrate coverage reached up to 91.79% for 36 kV, while for 30 and 24 kV it was 46.36 and 75.64%, respectively.

Figure 8c presents the cumulative size curves for the three coatings, as well as the curve for the one in which only air injection was applied (M0b-S), as can be seen, applying an electric field in addition to air injection has the effect of increasing the average particle size in such a way that when its intensity is increased this effect is even greater, going from an average size of 26.5 nm for a field produced by 24 kV to 31.5 nm for that produced by 36 kV, the same also occurs with the size dispersion, as can be seen through the decrease in the slope of the curve as the field intensity increases (values are in the same figure), going from 4.99 to 3.19 for 24 and 36 kV respectively.

To further highlight the effect that applying an electric field and air injection have together on the average particle size that constitute the coating and the dispersion of their sizes,

Figure 8e presents the cumulative size curves for the M0b-S, M2-S and M5-S coatings, which synthesis was assisted by: air injection in M0b-S, electric field produced by a voltage of 30 kV between electrodes in M2-S and electric field of 30 kV in addition to air injection in M5-S. These cumulative curves show how the effects of the electric field and the air injection on the size of the particles that make up the M5-S coating overlap, giving rise to a film made up of nanoparticles with an average size of 35.33 nm and a mode of 27.50 nm, which are intermediate values between the average sizes and modes values for when only air injection is applied (M0b-S): 29.90 nm and 19.45 nm and when only electric field is applied (M2-S): 40.71 nm and 33.79 nm. Likewise, figures 8d, e and f show how the effect of the electric field on the size of the particles is shielded by the effect that air injection has on them. It is observed that as the intensity of the electric field is reduced, the size of the particles becomes increasingly similar to that obtained by only injecting filtered air into the precursor solution. Now, regarding the morphology of the coating, it is observed that applying an electric field, in addition to air injection, does not affect the columnar type growth that ZnO presents with only air injection, it is even also possible to observe the perpendicular growth of the bars with respect to the substrate surface in the M5-S coating (30 kV) for which the coverage of the substrate surface was lower, around 46.38%. In the M6-S (24 kV) and M4-S (36 kV) coatings, the amount of material deposited on the substrate is such that the growth of bars perpendicular to the surface cannot be seen.

To determine the effect of the pH of the precursor solution on the coating morphology and particle size that comprise it, a comparison was made between micrographs M1-S vs M7-S and micrographs M2-S vs M8-S that were synthesized only under the influence of an electric field and at the same synthesis conditions between them, except for the pH of the solution, which between the coatings M1-S and M7-S, synthesized at 24 kV, had a pH difference of up to 2.5 (

Figure 8g), while between M2-S and M8-S, synthesized at 30 kV, the pH difference was never greater than 1 (

Figure 8h). In both comparisons it is observed that when the pH decreases the coalescence between the particles that make up the coating decreases notably to such an extent that it is practically imperceptible, in addition to the fact that the average size of the particles that make up the coating practically does not change, however, the dispersion of the particle sizes decrease notably when the pH decreases to such an extent that the solution goes from alkaline to acidic, which can be seen in

Figure 8g with the significant increase in the slope of the cumulative size curve for M7-S with respect to M1-S.

As a general discussion, we propose that the growth conditions employed in our ZnO thin film system exert a significant influence on coalescence and, consequently, on film compaction. These phenomena are directly correlated with the attainment of crystallinity, crystallite size, and surface morphology. Coalescence refers to the process wherein particles merge to form a continuous film, evidently affecting both morphological features and the structural crystallinity of the film. Meanwhile, film compaction, related to density and absence of porosity, can impact transparency and optical properties.

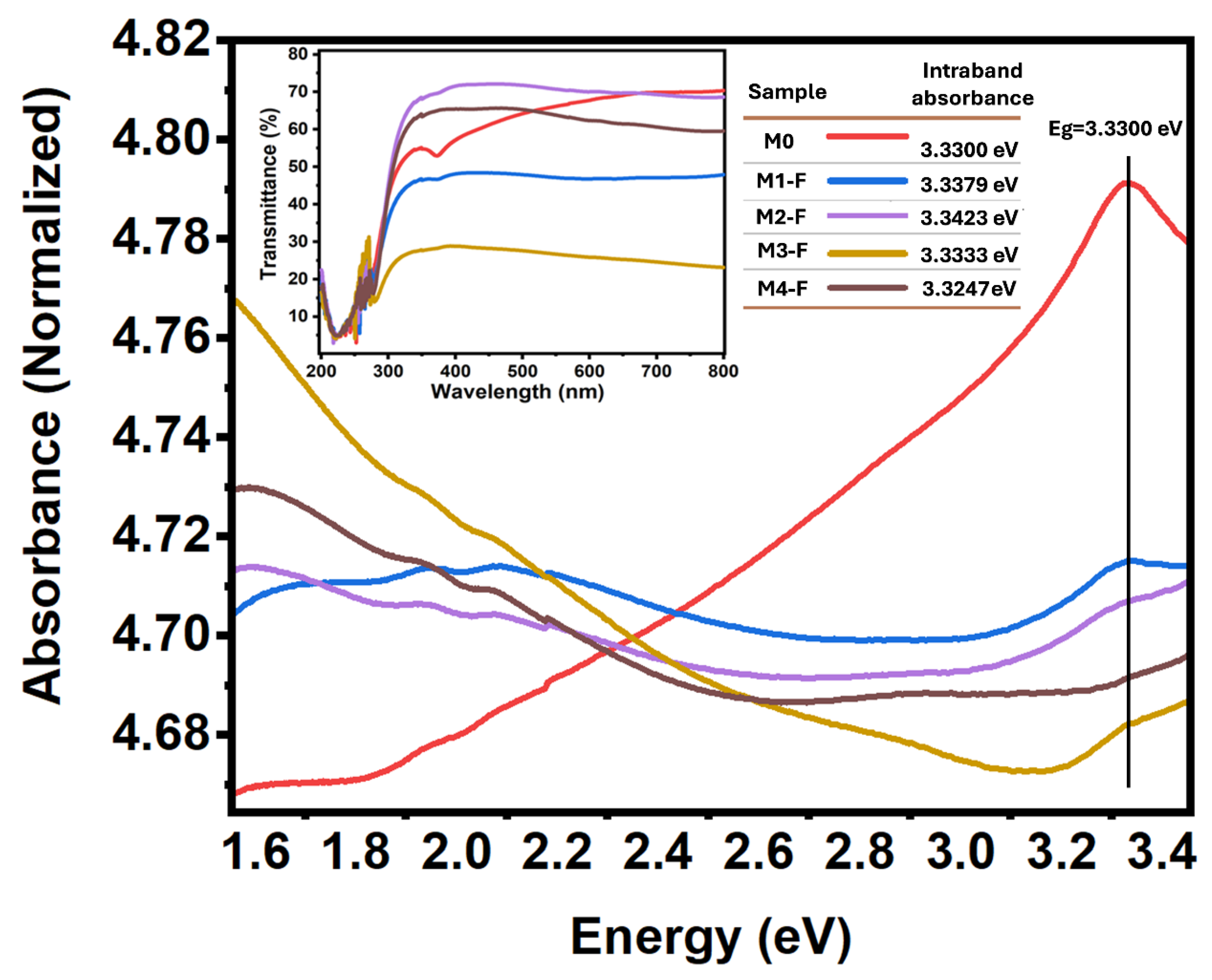

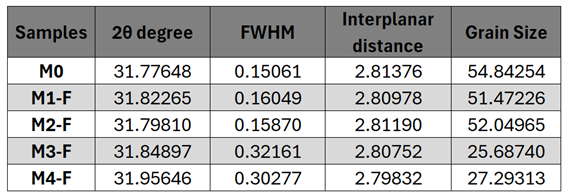

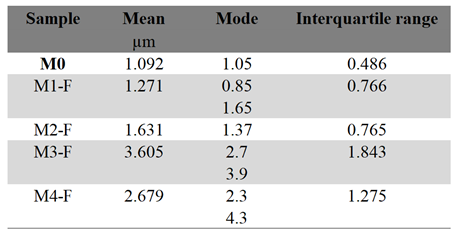

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis revealed that the application of an electric field and polarity inversion induced a reduction in interplanar spacing and an enhancement of crystallinity, suggesting increased coalescence of crystallites. This is further reflected in the reduced crystallite size, implying a higher density of defects, although the improved crystallinity may mitigate some of these effects.

Regarding crystallite size, the CBD-HVEF-B configuration at 30 kV achieved a higher degree of coalescence and substrate coverage, resulting in a more compact film with minimal particle size dispersion. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) confirmed that the combination of electric field application and air agitation produced a mixed morphology featuring both nodular and columnar characteristics, alongside enhanced substrate coverage. Future studies could explore residual stresses, surface strain, and electrical properties [

21].