1. Introduction

Cancer in children and adolescents, or youth cancer, is one that affects individuals between 0 and 19 years of age. Each year, an estimated 400,000 children and adolescents are diagnosed with cancer in the world [

1]. Currently, in developed countries, about 80% of cases of youth cancer can be cured if diagnosed and treated early. Despite advances in youth cancer treatment, health teams are constantly concerned with the care of this patient. One of them is adequate pain management, which begins with assessment, moves on to an intervention, pharmacological or not, and a subsequent reassessment [

2,

3,

4]

In 2020, the concept of pain was updated by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP): "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated, or similar to that associated, with an actual or potential tissue injury". Thus, the evaluation and treatment as soon as possible depend on a trained and prepared multidisciplinary team [

5].

A systematic review indicated a pain prevalence of 44.5% among cancer patients [

6]. Of those who are undergoing treatment, 55% report pain, and this symptom is also present in 66% of patients with advanced, metastatic, or end-stage cancer. Several physiological factors contribute to cancer causing pain, such as the presence of the tumor itself in the tissues, squeezing them, and the adverse effects of treatment, for example peripheral neuropathy, muscle spasm, constipation, and others. In addition, the fact that these patients are feeling pain influences psychologically and socially in a negative way, which extends to family members [

7,

8,

9].

To measure pain, there are several validated tools that classify intensity qualitatively and quantitatively, the latter through scores. When self-report is possible, a numerical scale from 0 to 10 can be used, with 0 representing the absence of pain and 10 representing unbearable pain, or a diagram with facial representation. In cases where self-report is not possible, an assessment of behavior and physiological aspects indicative of pain is used, such as the scale

Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability (FLACC) [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The WHO has proposed an analgesic ladder for pain management, consisting of three steps. The first considers mild pain and with the proposal of pharmacological treatment using non-opioid analgesics, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or paracetamol, which may include an adjuvant drug. The second step considers moderate pain and includes weak opioids (codeine and tramadol) along with the treatment proposal of the first step. And the third and last step, considers it intense and unbearable pain, adding to the drugs of the second step a strong opioid, such as morphine, fentanyl, methadone and oxycodone. In 2023, an update of this analgesic ladder was published, adding a fourth step, which includes non-pharmacological procedures and techniques [

15]. The analgesic ladder is only a general guide to pain management. For effective control, it is essential to adopt individualized approaches that consider the child's stage of development and their social context, valuing their safety in the use of medication, with multiprofessional actions and pharmaceutical care [

4,

16,

17,

18]. Pain is a highly prevalent symptom in pediatric cancer patients, but its management is still often inadequate [

19]. However, there is a paucity of comprehensive studies that evaluate in detail the dose and appropriate selection of analgesics to achieve an optimal therapeutic effect in these patients [

20]. Given this gap, there is a significant opportunity to improve pain management strategies in pediatric oncology. Thus, the main aim of the present study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the chosen analgesic medication according to the intensity and location of pain.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective descriptive pharmacoepidemiological study in the Hospital GRAACC (Grupo de Apoio ao Adolescente e Criança com Câncer - Ethics Committees: 64195522.8.0000.5505 and IOP-007-2020). This children's oncology hospital located in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Pediatric patients aged 0 to 17 years, diagnosed with cancer, who were admitted to the hospital during the period from January 2021 to March 2022.

The patient was assessed for pain by a nurse, who used one of these three methods: FLACC scale, facial scale, and numerical scale. All nurses received training on the choice of pain assessment instrument and its correct use. For all of them, the intensity of pain was standardized from 0 to 10, so that 0 represents no pain and 10 represents the most intense pain that can be felt. Self-report of pain was prioritized, and when this was not possible, a validated instrument independent of the patient's self-report was applied to measure pain. After obtaining the numerical intensity of the patient's pain, it was recorded in the patient's specific medical record together with the indication for pharmacological or non-pharmacological intervention for pain relief. After the intervention for pain relief, the patient was reassessed using the same pain assessment instrument to identify pain relief or the need for a new intervention.

The choice and subsequent dispensation of the analgesic medication were in accordance with the institutional pain management protocol. In this case, the drugs dipyrone and paracetamol are recommended for mild pain, tramadol, in cases of moderate to severe pain, and morphine, for severe and unbearable pain. The dosing regimen depended on the patient's body weight, and the frequency of administration was in accordance with established guidelines on serum drug concentration.

From the sample of patients, individuals with pain records meticulously documented in their medical records were considered for inclusion, those who underwent a pain assessment using a scale and obtained a score equal to or greater than 1, and used paracetamol, dipyrone, ketorolac, morphine, nalbuphine or tramadol for pain management and after the pharmacological intervention underwent a pain reassessment were included.

Through the medical records, data were collected regarding the age, gender, cancer diagnosis of the patients, the tool used to assess pain, and the intensity score before and after the pharmacological intervention, along with the time interval between the reassessments. Regarding the drugs used, information on the name of the drug, dosage, and route of administration was collected.

Data on cancer diagnosis was grouped according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (ICCC). The ICCC classifies childhood neoplasms into 12 main groups, which are subdivided into 47 subgroups: I. leukemias, myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic diseases; II. Lymphomas and reticuloendothelial neoplasms; III. central nervous system (CNS) tumors and miscellaneous intracranial and intraspinal neoplasms; IV. Tumors of the sympathetic nervous system; V. retinoblastoma; VI. Renal tumors; VII. Liver tumors; VIII. malignant bone tumors; IX. soft tissue sarcomas; X. germ cell, trophoblastic and other gonadal neoplasms; XI. carcinomas and other malignant epithelial neoplasms; XII. other unspecified malignant tumors [

21]. The age of the patients was grouped according to age group at development, considering infants as those aged between 0 and 1 year, preschoolers, aged between 2 and 4 years, schoolchildren, aged between 5 and 10 years, and adolescents, aged between 11 and 19 years. The pain intensity score was grouped as 'no pain' when it was equal to 0, 'mild' from 1 to 3, 'moderate' from 4 to 6, 'severe' from 7 to 9 and 'unbearable' from 10. The reassessment score was grouped in relation to the first score, so that total improvement for patients without pain complaints, which means a final score equal to 0, partial improvement for patients with a final score lower than the initial score, no improvement when the final score was equal to the initial score, and pain worsening when the final score was higher than the initial score. Each report of pain or pain conditions verified by the nursing or medical team was considered a pain episode.

The data are described as mean and standard deviation or median for the continuous variables and as count and percentage for the categorical variables. The normality of the main variables was tested with Kolmogorov-Smirnov. Comparisons between initial and final pain score were determined using paired measures Wilcoxon test. Qui-Square test was used to compare the differences in the proportion of used drugs according to the location and the intensity of the pain. All statistical procedures were conducted with SPSS version 27.0 statistical package [

22].

3. Results

A total of 1,465 episodes of pain from 335 patients were included, most of whom were male (55.5%). The predominant age groups were School and Adolescent, which include the ages between 5 and 19 years, totaling 227 individuals, which represents 67.7% of the patients. Regarding the diagnosis of cancer, according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (ICCC), the most frequent was "leukemias, myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic diseases" (n=101; 30.1%), followed by "central nervous system (CNS) tumors and miscellaneous intracranial and intraspinal neoplasms" (n= 76; 22.7%) (Supplemental Table S1 shows general characteristics of patients).

Each report of pain by the patient or verified by the team was considered an episode of pain, which were grouped into pain sites, as described in

Table 1.

Pain sites classified as 'other' included those with a small sample size and were excluded from the study. Sites of generalized pain, upper limbs, and thorax were also excluded due to a low sample size. For episodes of pain in the abdomen, head and lower limbs (n=650), the drugs dipyrone, paracetamol, ketorolac, morphine, tramadol and nalbuphine were given as pharmacological treatment. For reasons also due to the low sample size, those episodes of pain that received paracetamol, ketorolac, tramadol and nalbuphine as treatment were excluded (n=74). Thus, 576 episodes of pain (39.3%; 576/1,465) were considered, which were treated with dipyrone and morphine, 283 (19.3%) in the abdomen, 155 (10.6%) in the head and 138 (9.4%) in the lower limbs.

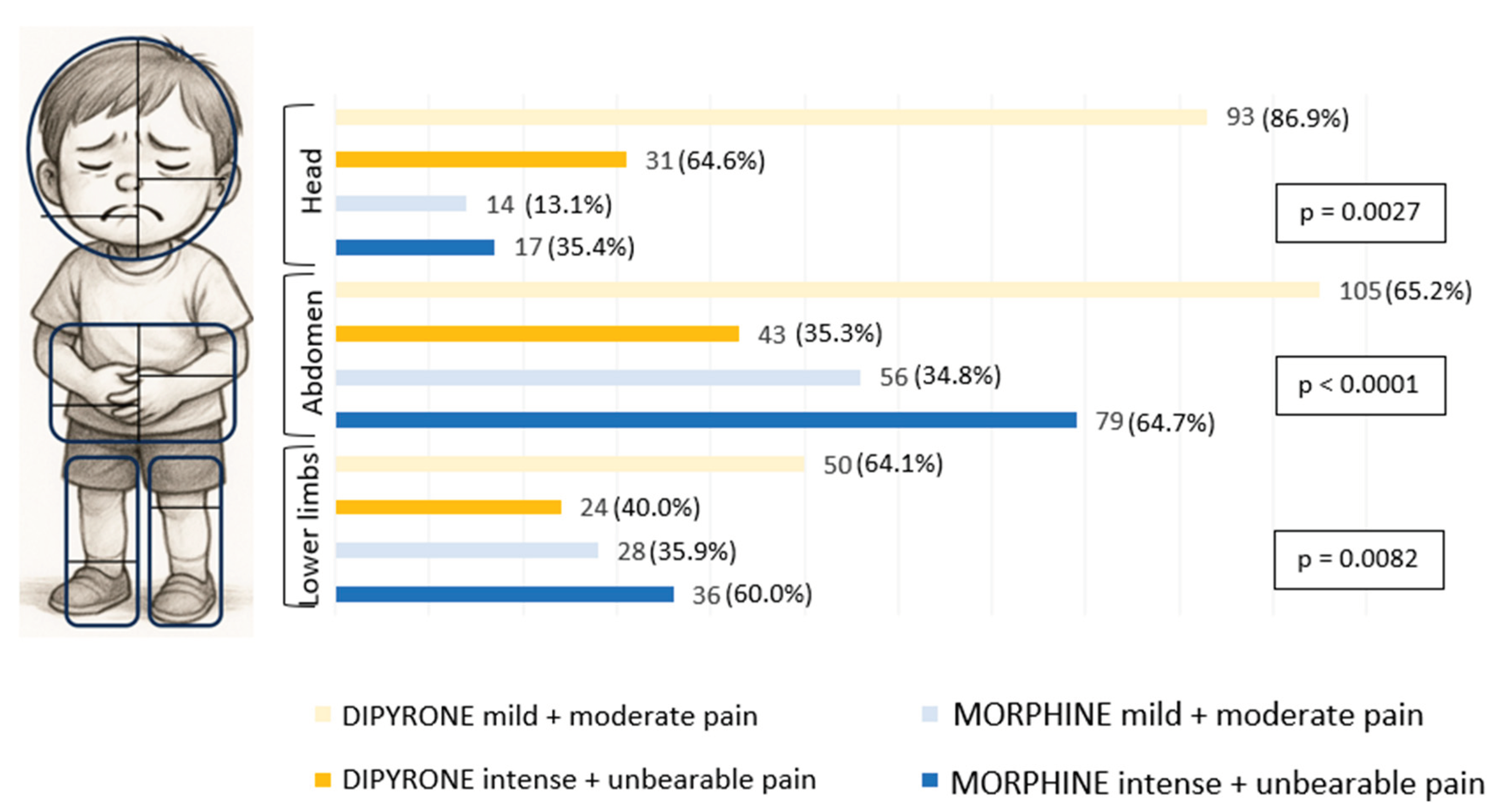

To evaluate the analgesic effect of morphine and dipyrone drugs, for each site we verified how many episodes of pain were treated with these drugs, stratifying the intensity into two groups, one group composed of mild and moderate intensities (n=346; 60%), and the other of intense and unbearable intensities (n=230; 40%) (

Figure 1).

In pain considered mild and moderate, dipyrone was preferred instead of morphine. And when the pain was stronger, as intense and unbearable, there was a preference for the drug morphine when the pain was in the abdomen and lower limbs. Only in headache pain, in intense and unbearable pains, dipyrone was more commonly used than morphine (

Figure 1).

To verify the effectiveness of the chosen medication, we compare pain intensity scores before and after the pharmacological intervention. In all situations, the median initial score is significantly different and higher than the median final score, i.e., the drugs dipyrone and morphine decreased pain in a noticeable way, improving the patient's state in relation to pain.

Table 2.

Pharmacological effectiveness according to drug, pain local and intensity.

Table 2.

Pharmacological effectiveness according to drug, pain local and intensity.

| |

Abdomen |

Head |

Lower limbs |

| |

Median initial score |

Median final score |

Median initial score |

Median final score |

Median initial score |

Median final score |

| Dipyrone* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mild + Moderate |

5 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

| Intense + Unbearable |

8 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

| Morphine* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mild + Moderate |

5 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

| Intense + Unbearable |

8 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

4. Discussion

The choice of pharmacological treatment was effective when considering both pain intensity and location. It is noteworthy that, when the pain was located in the head, dipyrone was more frequently administered across both pain intensity groups. The most prevalent cancer types among children and adolescents in this study were leukemias, myeloproliferative disorders, and myelodysplastic syndromes, accounting for 30.1% of cases. In Brazil, the most prevalent cancer in the same population is leukemia (26%), followed by lymphomas (14%) and central nervous system tumors (13%) [

23].

This study revealed a higher incidence of reports of mild and moderate pain, like the findings of Andersson et al [

24], which reported a greater occurrence of mild and moderate pain both at rest and during movement. However, this contrasts with the findings of Bakir et al [

25], whose study showed that severe pain was present in 72.2% of patients under 18 years of age with cancer admitted to the clinic. This difference may be since their study was conducted in a clinic specialized in chronic pain.

The most frequently reported pain location in the episodes included in this study was the abdomen, followed by the head and lower limbs. Similarly, Bakir et al. also found a higher incidence of pain in these three regions; however, in their study, the most common location was the lower limbs, followed by the abdomen and head.

In the present study, dipyrone was administered in 60% of pain episodes and morphine in 40%. Another study, conducted in the pediatric division of a teaching hospital in São Paulo, observed that dipyrone was administered in 76.1% of children experiencing pain. Among the children with severe pain (125 cases), only 18 received morphine. That study did not assess the effectiveness of the analgesics, i.e., whether pain was reduced after administration, likely due to a low percentage of recorded pain reassessments in medical charts (40.3%) [

26].

In the study by Anderson et al, 74% of patients reported, through a questionnaire, that the administered analgesics—either alone or in combination—relieved their pain. These included paracetamol, NSAIDs, and opioids. These findings are consistent with the present study, in which pain relief was also significant [

24].

Dipyrone, which is widely used in Brazil, is an analgesic that is banned in the United States and in other countries that contribute significantly to pediatric pain research. Another aspect in which this study differs is the grouping of pain intensity according to the numerical scale. Most studies classify the pain scale as follows: 0 = no pain, 1–3 = mild pain, 4–6 = moderate pain, and 7–10 = severe pain. However, the present study considers a score of 10 to represent unbearable pain.

Pain can be classified into three main categories: nociceptive, neuropathic, and mixed. Distinguishing between these etiologies requires careful clinical evaluation, often supported by standardized tools such as validated questionnaires designed to identify the type of pain. However, considering that the population included in the present study comprises children aged 0 to 17 years, and that no validated instruments exist for the assessment of neuropathic pain in children under 5 years of age [

27], it was not possible to accurately differentiate pain types among the participants.

Pain management in children with cancer presents multiple challenges, including the difficulty of evaluating the effectiveness of analgesics in this specific population. The scarcity of randomized clinical trials with high levels of evidence undermines the scientific foundation of therapeutic approaches; pain control is often based on less robust evidence, such as case reports and case series, and it is common for pediatric analgesic dosages to be extrapolated from adult-based guidelines [

28]. Additionally, this study is a real-world evaluation that had the inability to stratify patients according to the stage of diagnosis, time of re-assessement after drug administration, and via of drug administration.

5. Conclusions

The use of dipyrone and morphine, guided by pain intensities and locations, demonstrated effectiveness. These findings support the tailored use of analgesics according to pain characteristics to optimize symptom control in pediatric oncology patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

conceptualization, F.C.M. and P.C.J.L.S.; methodology, F.C.M., E.L.L., T.S.G. and P.C.J.L.S.; investigation and analysis, F.C.M., E.L.L., S.R.M., T.S.G. and P.C.J.L.S.; data curation, E.L.L. and T.S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C.M. and I.A.O.; writing—review and editing, F.C.M., E.L.L., I.A.O., T.S.G., S.R.M., C.P.J.K. and P.C.J.L.S.; supervision, P.C.J.L.S.; project administration, P.C.J.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Capes (001): CNPq.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo (64195522.8.0000.5505) and by the scientific committee of the GRAACC Hospital (IOP-007-2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Steliarova-Foucher, E., et al., International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001–2010: a population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol 2017, 18, 719–731.

- Smith, B.H., J.L. Hopton, and W.A. Chambers, Chronic pain in primary care. Fam Pract. 1999, 16, 475–482.

- Gonçalves, T.S., et al., Improving Pediatric Oncology Knowledge Through Pharmaceutical Health Education. J Cancer Educ, 2025.

- Gonçalves TS, F.L., Sousa AVL de, Nascimento MMG do, Santos PCJ de L., Cuidado Farmacêutico ao Paciente da Oncopediatria: Construção de Cartilhas Educativas para o Tratamento das Leucemias Linfoblásticas Agudas, in Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia. 2024, INCA – Instituto Nacional de Câncer: Rio de Janeiro. p. e-144578.

- DeSantana, J.M., et al., Definição de dor revisada após quatro décadas. 2020, Sociedade Brasileira para o Estudo da Dor (SBED): São Paulo, Brasil. p. 197-198.

- Snijders, R.A.H., et al., Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer 2022: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15.

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee, in WHO Guidelines for the Pharmacological and Radiotherapeutic Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Adolescents. 2018, World Health Organization © World Health Organization 2018.: Geneva.

- Cohen, L.L., K.E. Vowles, and C. Eccleston, Parenting an adolescent with chronic pain: an investigation of how a taxonomy of adolescent functioning relates to parent distress. J Pediatr Psychol 2010, 35, 748–757. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraldstad, K. and T.H. Stea, Associations between pain, self-efficacy, sleep duration, and symptoms of depression in adolescents: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1617.

- Bussotti, E.A., R. Guinsburg, and L. Pedreira Mda, Cultural adaptation to Brazilian Portuguese of the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability revised (FLACCr) scale of pain assessment. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2015, 23, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, E.L., et al., Evaluations of NSAIDs and Opioids as Analgesics in Pediatric Oncology, in Future Pharmacology, G.E.A. Navarrete-Vázquez, Editor. 2023, MDPI. p. 916–925.

- Friedrichsdorf, S.J., et al., Pain Outcomes in a US Children's Hospital: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Survey. Hosp Pediatr 2015, 5, 18–26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garra, G., et al., Validation of the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale in pediatric emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 2010, 17, 50–54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.C. and L.C. Thuler, Cross-cultural adaptation and translation of two pain assessment tools in children and adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2008, 84, 344–349. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anekar, A.A., J.M. Hendrix, and M. Cascella, WHO Analgesic Ladder, in StatPearls. 2025, StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL).

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee, in Guidelines on the management of chronic pain in children. 2020, World Health Organization © World Health Organization 2020.: Geneva.

- Marcatto, L., et al., Impact of adherence to warfarin therapy during 12 weeks of pharmaceutical care in patients with poor time in the therapeutic range, in J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021: Netherlands. p. 1043-1049.

- de Lara, D.V., et al., Pharmacogenetic testing-guided treatment for oncology: an overview of reviews. Pharmacogenomics 2022, 23, 739–748. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobina, I., et al., Prevalence of self-reported chronic pain among adolescents: Evidence from 42 countries and regions. Eur J Pain 2019, 23, 316–326. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ccleston, C., et al., Pharmacological interventions for chronic pain in children: an overview of systematic reviews. Pain 2019, 160, 1698–1707. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feliciano, S.V.M., M.d.O. Santos, and M.S. Pombo-de-Oliveira, Incidência e Mortalidade por Câncer entre Crianças e Adolescentes: uma Revisão Narrativa. 2018, Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. p. 389-396-.

- IBM, IBM SPSS Software. IBM.

- Santos, M.d.O., et al., Estimativa de Incidência de Câncer no Brasil, 2023-2025, in Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia. 2023, Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA): BRASIL.

- Andersson, V., et al., Pain and pain management in children and adolescents receiving hospital care: a cross-sectional study from Sweden. BMC Pediatr 2022, 22, 252.

- Bakır, M., Ş. Rumeli, and A. Pire, Multimodal Analgesia in Pediatric Cancer Pain Management: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e45223.

- Carvalho, J.A., et al., Pain management in hospitalized children: A cross-sectional study. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2022, 56, e20220008. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anghelescu, D.L. and J.M. Tesney, Neuropathic Pain in Pediatric Oncology: A Clinical Decision Algorithm. Paediatr Drugs 2019, 21, 59–70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, C., H. Huang, and R. Thienprayoon, Managing Pain and Discomfort in Children with Cancer. Current Oncology Reports 2022, 24, 961–973. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).