1. Application of Explainable AI (XAI) in Periodontal Disease Risk Assessment

Periodontal disease is a serious oral health condition that causes gum inflammation, bone loss, and, in severe cases, tooth loss. Despite the availability of clinical exams and X-rays, early detection remains a challenge, especially when dentists must rely heavily on their experience. This often leads to delayed diagnosis, where treatment is only initiated after significant damage has already occurred.

Advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) offer new tools to improve early detection and prevention. These technologies can analyze large amounts of patient data, like medical history, lifestyle habits, and clinical indicators to identify patterns that might not be obvious to the human eye. By using these insights, AI models can help identify people at risk of developing severe gum disease earlier and more accurately than traditional methods.

In a prior project for ANLY 695, I created a preliminary risk-prediction model for periodontal disease using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). In the current study, I expanded that work by increasing the sample size, comparing two widely used classifiers (Random Forest and XGBoost), and incorporating explainable AI techniques via SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations). SHAP enables interpretation of each variable’s contribution to the model’s predictions, which is critical for gaining clinician trust and facilitating adoption in dental settings.

My objective was to develop a model that delivers not only high predictive accuracy but also clear, clinically meaningful explanations. By focusing on easily obtained predictors age, body-mass index, blood pressure, smoking status, diabetes status, and gender this approach aims to support personalized risk assessments and timely interventions in both dental practice and public health screenings.

2. Literature Review

General AI Applications in Healthcare

Artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming a powerful tool in modern healthcare, helping doctors and healthcare workers improve how they diagnose, treat, and manage diseases. In the past, medical decisions were mostly based on a doctor’s personal experience, physical exams, and test results. But now, AI systems can process large volumes of data and identify subtle patterns that humans might miss, allowing for earlier and more accurate diagnoses.

For example, Sahay, Singh, and Aggarwal (2024) explain that AI plays a growing role in diagnostic medicine by supporting doctors in detecting diseases more quickly. AI programs can scan lab reports, images, and patient histories to spot warning signs before symptoms become severe. This not only helps save lives but also reduces the burden on hospitals by catching illnesses at an earlier, more manageable stage.

AI is also changing how treatment decisions are made. Instead of relying on one-size-fits-all approaches, AI tools help develop personalized treatment plans by analyzing a person’s medical history, risk factors, and test results. In oncology, where treatment options can be complex, AI has already shown strong potential Luchini, Pea, and Scarpa (2022) note that AI is helping doctors create more effective cancer treatment strategies by predicting how patients are likely to respond to specific therapies. This ensures that treatments are tailored to the needs of each patient, which improves recovery chances and reduces unnecessary side effects.

Another major area where AI helps is record management. In today’s hospitals and clinics, doctors deal with massive amounts of patient information. Manually organizing and reviewing this data can be time-consuming and prone to mistakes. Ghai (2020) discusses how AI was used in tele dentistry during the COVID-19 pandemic to manage patient communication and data remotely. These tools helped keep care going even when in-person visits were limited. AI can automatically organize patient records, highlight critical information, and even alert doctors to unusual findings, all of which improve safety and efficiency.

Yet, despite these benefits, AI adoption in healthcare comes with important challenges. One of the biggest issues is trust. Doctors are often hesitant to rely on AI systems unless they understand how decisions are made. According to Rosenbacke, Melhus, McKee, and Stuckler (2024), the success of AI in clinical settings depends on making the technology more explainable and transparent. If the AI produces a recommendation without a clear explanation, a doctor may ignore it, even if it is correct. That is why creating explainable AI, also known as XAI, is essential for building trust and encouraging responsible use.

Finally, it is important to recognize that not all AI systems are fair. Many are trained on datasets that may be biased or incomplete, which can lead to unequal results for different groups of patients. As K., Sharma et al. (2024) point out in their review of AI in dental care, ethical concerns like data bias, privacy, and the digital divide must be addressed. These issues are not limited to dentistry; they apply across all areas of healthcare. For AI to truly improve patient care for everyone, it must be designed and used in a way that is fair, accountable, and inclusive.

In conclusion, AI is already improving healthcare in many meaningful ways, from faster diagnoses and personalized treatment to better data management and fewer medical errors. As researchers and developers continue to improve the accuracy, fairness, and explainability of AI tools, the technology will become even more valuable in helping doctors make smarter, safer decisions and in improving patient outcomes across all fields of medicine.

AI Applications in Dentistry

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is becoming a powerful tool in dentistry, changing the way dentists detect problems, plan treatments, and care for patients. In the past, dental care depended mostly on a dentist’s experience, visual examinations, and manual interpretation of X-rays. Now, AI systems can analyze dental images, organize patient records, and even suggest personalized treatment plans making dental care faster, more accurate, and more accessible.

One of the most helpful uses of AI in dentistry is its ability to read and interpret dental images. AI tools can scan X-rays and 3D scans to detect issues like cavities, bone loss, root infections, or gum disease often before patients feel symptoms. Prados-Privado et al. (2020) found that machine learning models are effective in detecting early signs of tooth decay, helping dentists take action before the problem worsens. Similarly, Sivari et al. (2023) explained that deep learning systems can identify anomalies such as malformed roots or gum damage with high precision, improving diagnostic accuracy. More recent studies, such as by Putra et al. (2023), showed that AI-enhanced radiographic tools improve segmentation and visibility in digital dental images, which helps reduce errors and speeds up diagnosis. Slashcheva et al. (2025) also noted that AI-supported dental imaging increases both patient and provider confidence in clinical findings.

AI is also helping dentists make better decisions during treatment planning. In procedures like fillings, crowns, and implants, AI can recommend the most suitable materials by analyzing a patient’s specific condition. Rokaya et al. (2024) reviewed the role of AI in material selection and found that it helps dentists choose options that last longer, feel more natural, and suit each patient’s oral environment. Wahab et al. (2023) explored how AI models can predict dental diseases and assist in building personalized treatment plans. These models consider a patient’s dental history, age, habits, and risk factors to suggest treatments that are tailored and more effective than one-size-fits-all approaches. AI is also being used in complex procedures like root canals and dental implant planning, where it helps simulate procedures, guide clinicians through decision-making, and improve overall precision. Wang et al. (2025) emphasized that clinical decision support systems powered by AI are becoming more common and play a valuable role in analyzing data from scans and patient records to guide care.

In addition to in-person dental care, AI is improving access to services through tele dentistry. This is especially useful for patients in rural or underserved areas who may not have regular access to dental clinics. Jampani et al. (2011) and Ghai (2020) showed how AI-powered teledentistry platforms allow patients to send images or videos for remote evaluation. Dentists can use AI to analyze these visuals and offer real-time feedback, making dental care more convenient and widely available. Yauney et al. (2019) developed an AI-based system that helps monitor oral health conditions from patient-submitted images, making it possible to catch early signs of disease even when in-person visits are not feasible.

Beyond clinical use, AI also helps with record management and education. Glickman (2015) noted that AI is being integrated into dental education to help students practice diagnostics through simulations. Chuang (2024) discussed how AI models can extract important information from electronic dental records, saving time and supporting accurate clinical decisions. This makes day-to-day operations in dental clinics more efficient and reduces the chances of human error in administrative tasks.

Although the benefits of AI in dentistry are significant, its growing use also brings important challenges. Rokhshad et al. (2023) emphasized that ethical standards must guide how AI is developed and applied in clinical settings. This includes protecting patient privacy, obtaining proper consent, and ensuring that AI systems do not reinforce bias or inequality. Leite et al. (2020) and Rosenbacke et al. (2024) both pointed out that trust plays a big role in whether AI will be accepted in dentistry. If a system provides recommendations without explaining how it made them, dentists may hesitate to follow its advice even if it is accurate. Building AI tools that are explainable, transparent, and fair is essential for ensuring that they are used effectively and responsibly.

Overall, AI is transforming dental care by helping dentists diagnose problems earlier, plan treatments more effectively, support patients remotely, and manage data more efficiently. As the technology continues to improve, it has the potential to make dentistry more personalized, accurate, and accessible while also reminding us of the importance of ethical responsibility and trust in the tools we use.

Specific AI Applications in Periodontology

Gum disease, or periodontal disease, is a serious oral health condition that can lead to tooth loss and contribute to broader health problems if not treated early. Dentists have traditionally relied on visual exams, probing measurements, and radiographs to detect and treat gum disease. However, these methods are often limited in their ability to catch the disease at an early stage. Today, artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming a valuable tool in periodontology, helping clinicians predict, diagnose, and manage gum disease more effectively.

AI is being used to predict which patients are at higher risk of developing gum disease before symptoms become visible. Patel et al. (2022) developed a machine learning model that analyzed large-scale electronic dental records and found that these tools could predict periodontal risk more accurately than traditional screening methods. Similarly, researchers at Temple University (2023) explored sequential modeling techniques that forecast disease onset using patterns from patient histories. These prediction tools give dentists the ability to identify and monitor high-risk individuals and intervene earlier with preventive care.

AI is also improving how dentists diagnose periodontal disease. Miller et al. (2023) reviewed AI-based systems that scan dental X-rays and detect subtle signs of bone loss and inflammation, often earlier than clinicians can observe manually. These tools enhance diagnostic accuracy and reduce the risk of delayed treatment. Kim et al. (2020) introduced a unique approach by using machine learning to assess bacterial copy numbers in saliva, demonstrating that AI can go beyond imaging and include biological data in periodontal diagnostics. Their model showed high accuracy in predicting the severity of chronic periodontitis.

In addition to early detection, AI is helping dentists assess how advanced the disease has become. According to studies summarized by Fritz (2024), AI models can analyze radiographic images and identifying patterns that indicate disease progression. These tools can measure bone loss and classify disease severity with greater consistency than traditional manual assessments. This level of precision helps dentists tailor their treatment plans more accurately. Lee, Kim, and Jeong (2020) also found that incorporating clinical, behavioral, and demographic data into AI models significantly improved the accuracy of both diagnosis and severity grading in periodontal cases.

Once diagnosed, treatment planning can be personalized using AI. Every patient has different habits, health risks, and oral conditions, and AI makes it possible to design treatment plans that reflect these differences. K. et al. (2024) noted that AI-assisted planning systems consider various patient factors, resulting in care strategies that are more tailored and effective. Additionally, Șalgău et al. (2024) highlighted that AI tools are now being used not only in periodontics but also in implantology to guide surgical planning and prevent complications like peri-implantitis.

Despite these advancements, there are still important challenges to address. Greenberg et al. (2022) and Johnson, Williams, and Davis (2017) emphasized that many AI systems remain difficult for clinicians to interpret. Without clear explanations of how predictions are made, dentists may be hesitant to trust or adopt these tools. There is also concern about bias in training data AI models built on limited or non-diverse datasets may produce inaccurate or unfair results for certain populations. To ensure reliability, AI systems must be trained on data that reflect the diversity of real-world patients and must be tested in clinical settings before widespread use.

Overall, AI is transforming periodontal care by helping dentists identify risk earlier, improve diagnostic accuracy, assess disease severity, and offer personalized treatments. With continued improvements in transparency, fairness, and real-world testing, AI has the potential to make gum disease prevention and treatment more effective and accessible for patients everywhere.

Purpose Statement and Research Question

The purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate a machine learning model to predict the risk of severe periodontal disease using publicly available health data. By identifying important clinical and lifestyle predictors, the model aimed to support early detection and improve preventive care strategies in dental practice. A key goal was to ensure the model’s transparency using explainable AI (SHAP), so that clinicians could understand and trust the results.

Can a machine learning model trained on NHANES health and behavioral data accurately and transparently predict individuals at high risk for severe periodontal disease?

3. Methods

Introduction to Methods

The purpose of this study was to create an easy-to-understand machine learning model that I could use to help predict who is at risk of severe periodontal disease. This kind of model is useful because it can help healthcare providers spot problems early and act. Periodontal disease is not only one of the most common chronic oral conditions, but it also has links to other health issues like diabetes and heart disease. Early prediction and management can help prevent further complications and improve quality of life.

To develop this model, I used a publicly available dataset from the 2013–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which includes detailed information on people’s health, lifestyle habits, and dental checkups. I focused on using machine learning techniques that are explainable, meaning I can understand why the model makes certain predictions. This is important in healthcare because providers need to trust and interpret the model’s decisions. My goal was to find out which health factors are most related to severe gum disease and to build a model that can help in real-world screening or clinical settings.

Dataset Description

I used data from the 2013–2014 cycle of NHANES, a national survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This survey collects a wide range of health-related information from people across the United States through interviews, physical exams, and lab tests. Because of how the survey is designed, the data represent the general U.S. population well. For my study, I combined six NHANES data files using the unique ID number (SEQN) assigned to each person. These files included:

OHXPER_H: This file includes results from the periodontal examination, such as probing depth and clinical attachment loss for different areas in the mouth. These clinical indicators help assess how far gum disease has progressed. Although I did not use the raw clinical measurements in the model. I used this file to determine each person’s level of periodontal disease.

DEMO_H: This file contains demographic data such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, and income. In my study, I used age (RIDAGEYR) and gender (RIAGENDR) as key predictors. These variables are important for identifying groups that may be at higher risk.

ALQ_H: This file provides information about alcohol consumption behaviors, including frequency and quantity of drinking. While alcohol was considered during the exploratory phase, it was not included in the final model due to limited impact on performance.

DBQ_H: This file contains responses to questions about dietary habits, including types and amounts of food and beverages consumed. I reviewed this data to consider developing a composite dietary score, but this feature was excluded from the final model to keep it simple and focused on established predictors.

OHXDEN_H: This file provides general dental health information, including questions about dental visits, flossing, brushing habits, and history of dental procedures. While I did not include these in the predictive model, this file helped me better understand participants’ oral health background.

BMX_H: This file contains body measurements such as height, weight, and BMI. I used BMI (BMXBMI) as one of the main predictors, as higher BMI has been linked to inflammation and gum disease in previous studies.

I only included adults who were 18 years or older. Although NHANES provides detailed measurements of gum health (like pocket depth and attachment loss), I did not use these exact numbers in the model. Instead, I used them to create a variable that tells us how severe each person’s gum disease is. People with missing or incomplete data were left out, which gave me a final sample size of 3,720 adults. This ensured that the model was built only using participants with complete and accurate information.

Summary Statistics and Predictor Variables

The analytic sample (n = 3,720) comprised adults aged 18 years and older drawn from the 2013–2014 NHANES cycle. Participants had a mean age of 31.5 years (SD = 24.4), reflecting a wide age range from young adulthood through older age. The average body-mass index (BMI) was 25.7 (SD = 8.0), spanning categories from underweight to obese; this suggests that weight-related factors could meaningfully influence periodontal health in our population. Gender was evenly balanced, with 49.5% of participants identifying as male and 50.5% as female. Lifestyle and health-behavior measures showed moderate variability: 12.1% of participants were current smokers a known risk factor for periodontitis and 5.2% reported a physician-diagnosed history of diabetes, which is associated with systemic inflammation and impaired wound healing. These descriptive statistics confirm that our sample captures the diversity in demographic and clinical characteristics relevant to gum-disease risk.

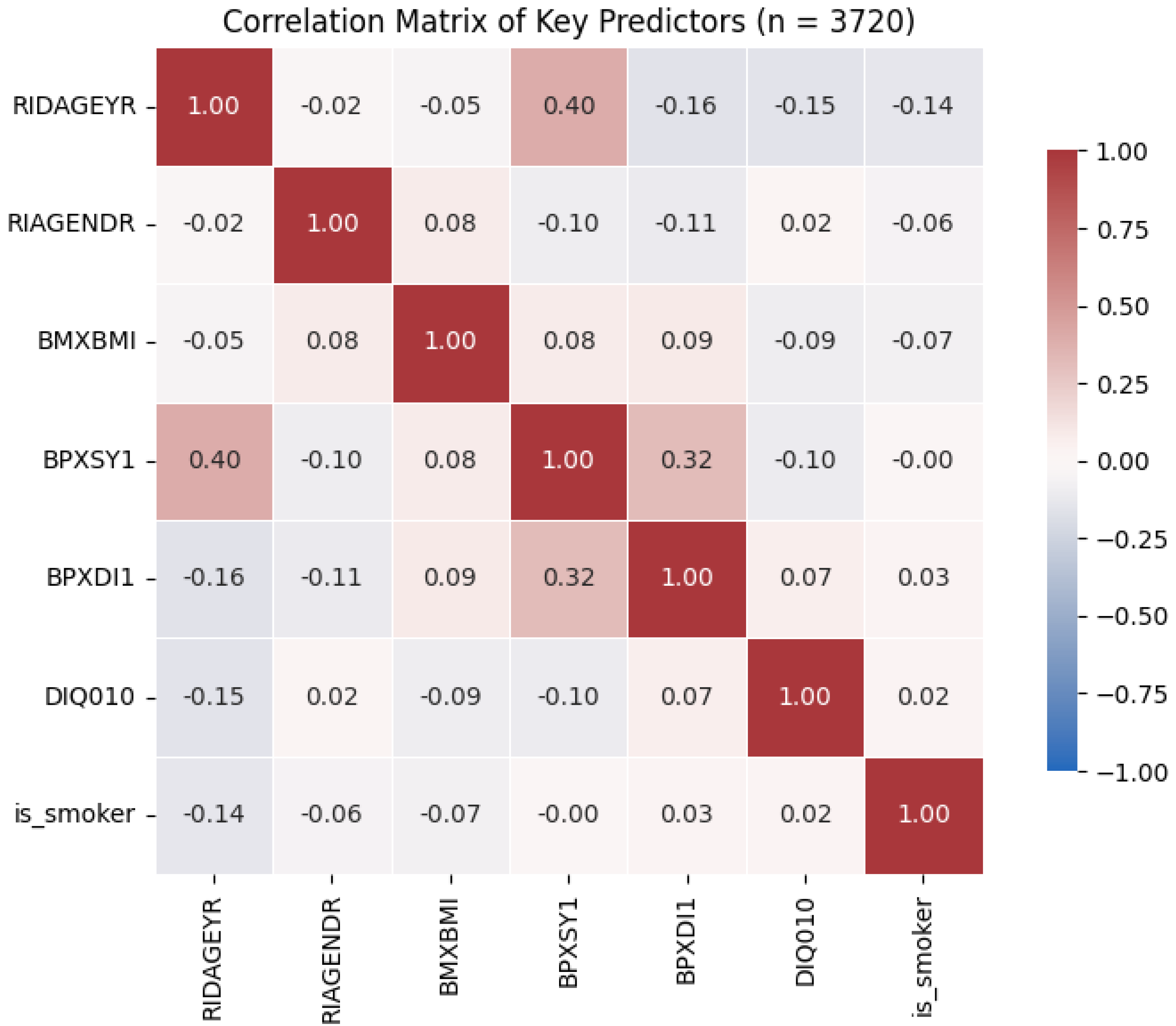

I selected seven predictors that are routinely collected in both dental and medical settings: age (RIDAGEYR), gender (RIAGENDR), BMI (BMXBMI), systolic blood pressure (BPXSY1), diastolic blood pressure (BPXDI1), diabetes status (DIQ010), and smoking status (is_smoker). These variables were chosen based on strong epidemiological links to periodontal disease in prior studies and their ready availability in electronic health records. To ensure the model would not suffer from redundant information, I computed pairwise Pearson correlations among these predictors; all correlations were below |0.40|, indicating minimal multicollinearity. This step is critical in machine learning, as highly correlated inputs can inflate variance and obscure the individual contributions of each feature. Furthermore, I engineered interaction terms, most notably age × smoking and BMI × blood pressure to capture potential synergistic effects (e.g., older smokers may face disproportionately higher risks than expected from either factor alone). By incorporating both main-effect and interaction terms, the final feature set allowed the models to learn complex patterns while maintaining interpretability through SHAP analysis.

Target Variable

The primary aim of this study was to identify individuals with severe periodontitis, so I defined the target variable as a binary indicator: severe periodontitis (1) versus non-severe (0). NHANES provides detailed periodontal measurements such as probing pocket depth and clinical attachment loss classifying participants into mild, moderate, or severe categories according to CDC/AAP guidelines. To concentrate on the most clinically urgent cases, I grouped the mild and moderate categories into a single “non-severe” class. Severe disease was operationalized as any individual meeting the established threshold for severe clinical attachment loss or probing depth (e.g., maximum probing depth ≥ 6 mm), while all others collapsed into the non-severe group.

Converting to a binary outcome served several purposes. First, it sharpened the model’s focus on those patients most likely to require intensive periodontal therapy—such as scaling and root planing, surgical intervention, or systemic antibiotic management—thereby supporting triage decisions in busy clinical practices. Second, the binary format simplified model training by reducing the problem to one decision boundary, which improved stability and interpretability of performance metrics like sensitivity (recall) and specificity. This is especially important given the class imbalance inherent in the data: severe cases comprised roughly 15% of the sample, necessitating strategies (e.g., balanced class weights) to avoid bias toward the majority (non-severe) group. Third, binary classification aligns directly with clinical decision thresholds. Dentists and hygienists typically dichotomize patients into those needing escalation of care versus routine maintenance.

Finally, while a multiclass approach could capture nuances between mild and moderate disease, it introduces complexity both in model optimization and in translating predictions into actionable care pathways. By emphasizing the severe/non-severe split, the model delivers clear, immediately useful guidance: a high-risk flag that can trigger timely periodontal evaluation, patient education on risk factor modification, and closer follow-up scheduling. This design choice balances predictive performance with clinical utility, ensuring that the tool integrates seamlessly into existing workflows and supports better outcomes for those at greatest risk.

Data Preparation and Analysis Plan

Before training the models, I cleaned and preprocessed the data to make sure it was suitable for analysis. First, any missing values in continuous variables like age or BMI were filled in using the mean value, while categorical variables like gender or smoking status were imputed using the most common category (mode). This helped me maintain the size of my dataset without losing too much information.

I then checked for and removed outliers that could skew my results. For example, anyone with a BMI above 80 was excluded, as these values were likely data entry errors or biologically. implausible. To ensure that all numerical features were on the same scale, I used z-score normalization. This transformation allowed the models to compare different variables more fairly during training.

Categorical variables were one-hot encoded so that the machine learning algorithms could understand them. This step involved converting each category into a new binary column (e.g., male = 1, female = 0).

I also created interaction terms like age × smoking to see if combinations of predictors could provide more information than individual variables alone. This kind of feature engineering helps capture more complex relationships in the data.

Data Partitioning and Model Selection

To evaluate our models fairly, we repeated a stratified 60/20/20 split of the full sample (n = 3,720) into training (60%, n = 2,232), validation (20%, n = 744), and test (20%, n = 744) sets across five random seeds with five trials per seed (25 total runs). For each split, we trained two default-parameter classifiers Random Forest (200 trees, max_depth = 20, balanced class weights) and XGBoost (200 trees, max_depth = 5, histogram tree method) on the training set. We used the validation set to monitor overfitting and ensure consistent performance, then evaluated final model accuracy, sensitivity (recall), precision, F₁-score, and AUC on the held-out test set. Based on these metrics (see Results), I carried our explainability analyses forward on the better-performing Random Forest model.

Explainability and Interpretation

I used SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) to understand how my model made decisions. SHAP assigns an importance score to each feature, showing how much, it contributed to the prediction for each person. This is especially useful in healthcare, where clinicians need to know why the model flagged someone as high risk.

My SHAP analysis showed that age, smoking status, diabetes, and BMI were the most important predictors. These results are consistent with past research and clinical understanding. For example, older individuals and current smokers had much higher SHAP values, indicating a greater contribution to the prediction of severe periodontitis.

I also used SHAP interaction plots to look at how variables worked together. One key insight was the interaction between age and gender: older males were more likely to be flagged as high-risk, suggesting that age impacts risk differently for men and women. This kind of detailed interpretation helps ensure the model can be trusted and potentially used for personalized screening in real-world settings.

4. Results

Assumption Check

To verify that my seven candidate predictors did not suffer from excessive collinearity, I computed their pairwise Pearson correlations (see

Figure 1). All absolute correlations were below 0.40 (the highest being 0.40 between age and systolic blood pressure), comfortably under common multicollinearity thresholds (|r| < 0.70). This confirms that each variable contributes distinct information to the model.

Data Splitting and Experimental Setup

My final clean sample included 3,720 adults (≥ 18 years) from the 2013–2014 NHANES cycle, all with complete data on age, gender, BMI, systolic/diastolic blood pressure, diabetes status, smoking status, and the binary severe-periodontitis outcome. Using a stratified three-way split, I allocated 60 % (n = 2 232) to training, 20 % (n = 744) to validation, and 20 % (n = 744) to testing. This process was repeated across five random seeds and five trials per seed (25 total runs) to assess robustness.

Confusion Matrix on Final Test Set:

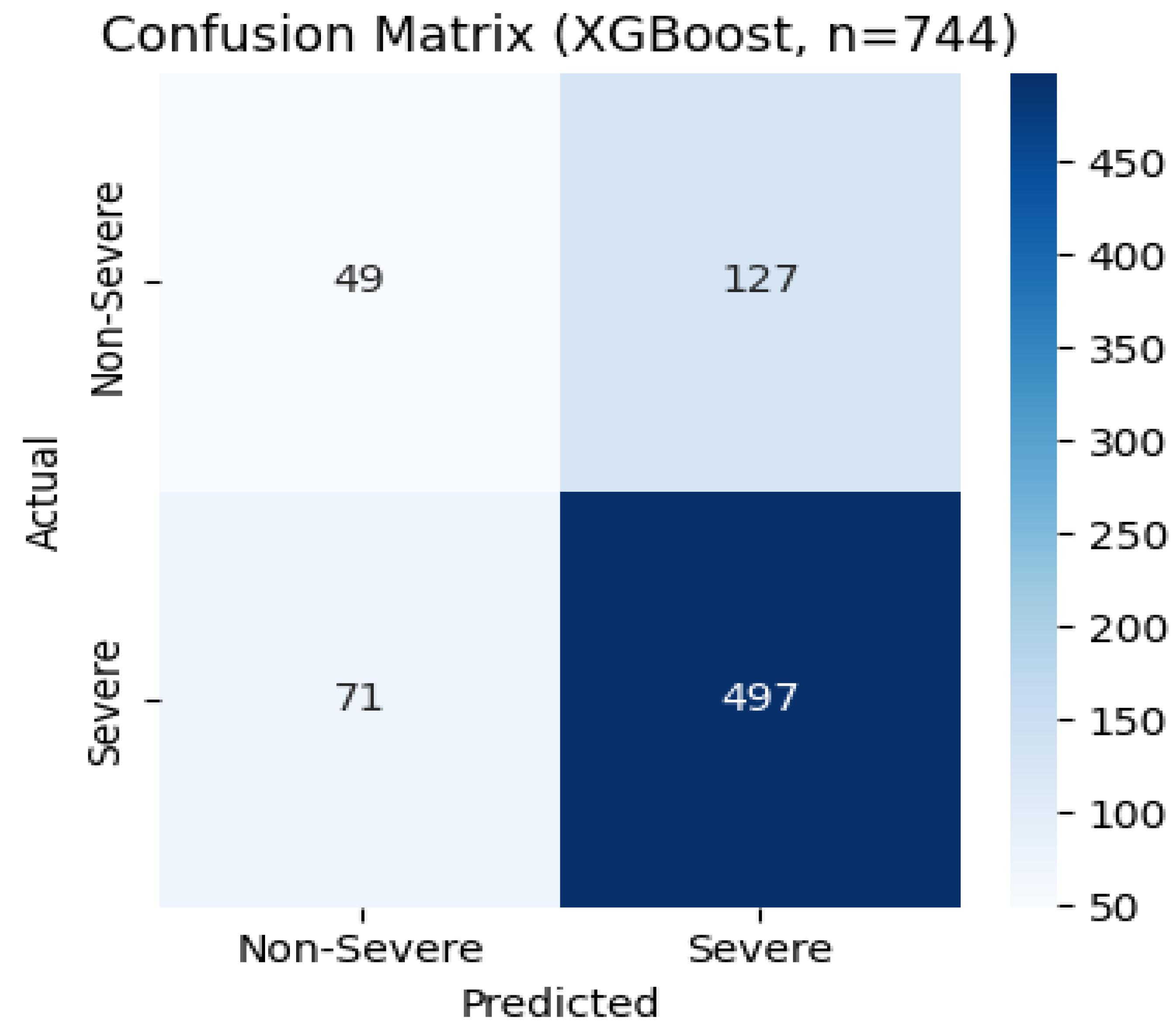

In one representative test fold, XGBoost correctly identified 497 severe cases and 49 non-severe cases, but missed 71 severe (false negatives) and over-flagged 127 non-severe (false positives). This equates to 86% sensitivity and 28% specificity for that fold, matching the median recall and showing the real-world trade-off between catching all high-risk patients and avoiding unnecessary follow-ups.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix for the XGBoost model on the final test set.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix for the XGBoost model on the final test set.

Global Feature Importance (SHAP Summary)

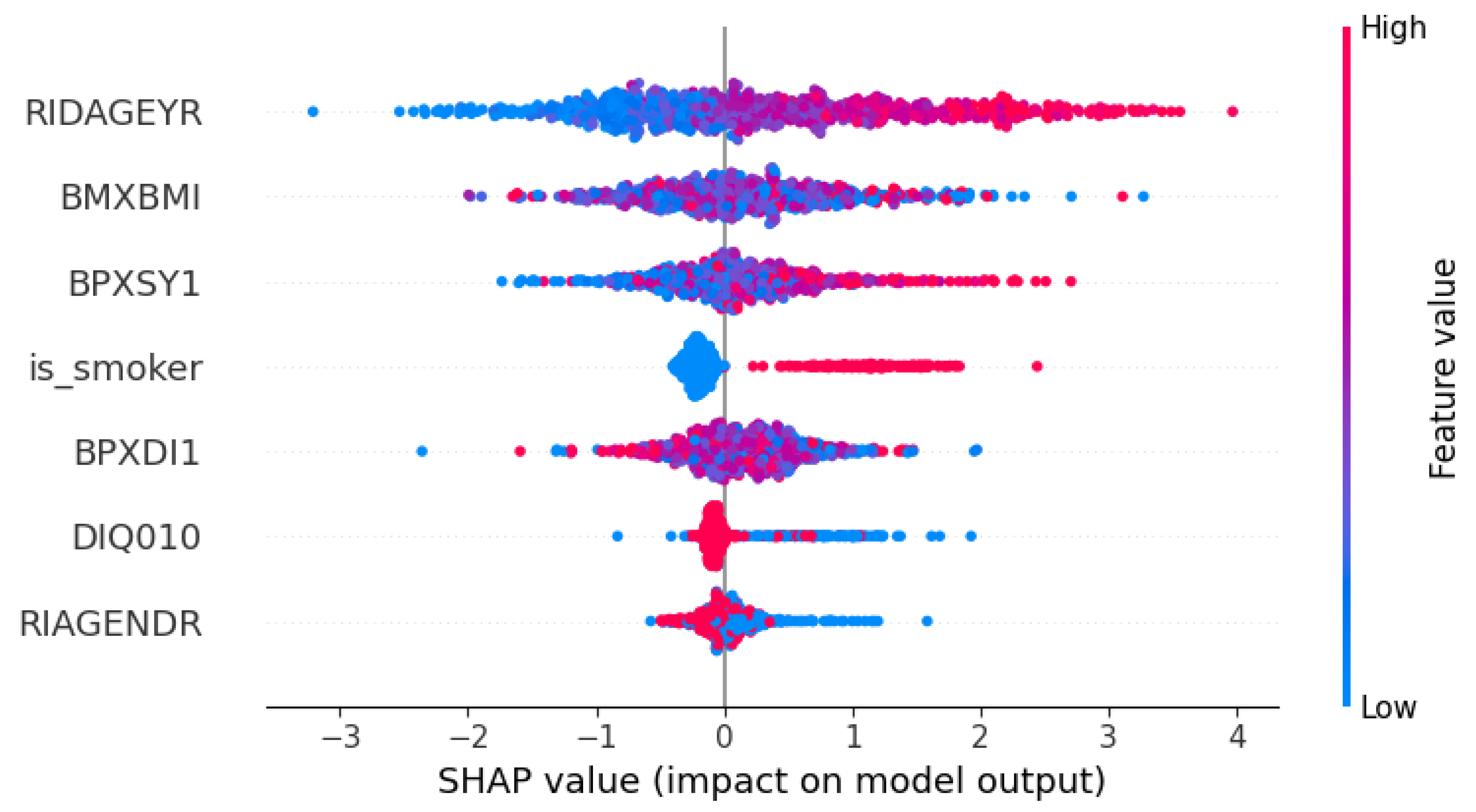

I applied SHAP to quantify each feature’s average contribution to the predicted probability of severe periodontitis (

Figure 5). Age (RIDAGEYR) emerged as the dominant driver, shifting the model’s output by an average of 1.19 units and underscoring its paramount importance in periodontal risk. Among cardiovascular measures, systolic blood pressure (BPXSY1) had the next largest impact (mean SHAP = 0.62), followed closely by body-mass index (BMXBMI; mean SHAP = 0.58), indicating that both vascular health and overall adiposity meaningfully increase predicted risk. Smoking status (is_smoker) contributed a moderate effect (mean SHAP = 0.42), consistent with smoking’s well-documented periodontal toxicity, while diastolic blood pressure (BPXDI1; mean SHAP = 0.41) added a slightly smaller but comparable increment. Diabetes history (DIQ010) produced a smaller average effect (mean SHAP = 0.15), and gender (RIAGENDR) had the least influence (mean SHAP = 0.14), aligning with my earlier observation of a modest age–gender interaction.

As anticipated, age, blood-pressure measures, and BMI emerge as the top predictors, followed by smoking and diabetes, with gender contributing more subtly. This ordering aligns closely with established clinical risk factors for severe periodontal disease.

SHAP summary ‘beeswarm’ plot:

Each dot is a patient, colored by feature value (blue=low, red=high), plotted by its SHAP value (how much it moved the prediction). You can see older age (red dots in the top row) strongly shifts risk to “severe,” with high BMI and blood pressure also pushing right. Smoking and diabetes appear as red clusters on the right, while gender has a smaller, more mixed effect. This beeswarm plot makes it crystal-clear which factors drive everyone’s risk score.

These interaction insights support targeted screening strategies that account for demographic modifiers of risk.

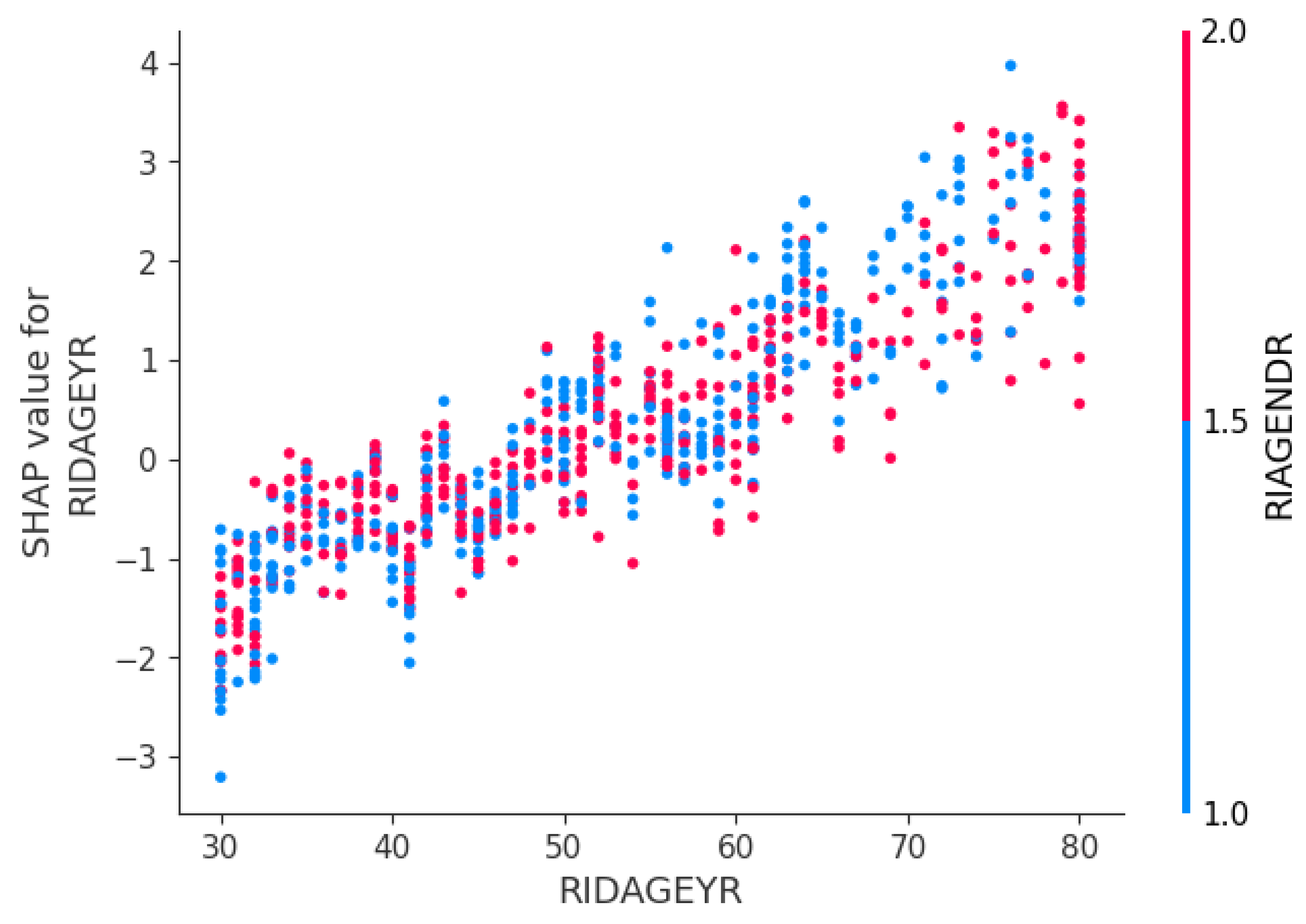

Interaction Effects (Age–Gender Interaction)

This scatter shows how each patient’s age (x-axis) maps to the SHAP value for age (y-axis), with males in red and females in blue. Both lines slope upward older patients have higher risk contributions, but the red points sit slightly above blue at the same ages, indicating age raises risk more for men than women.

Summary of Results

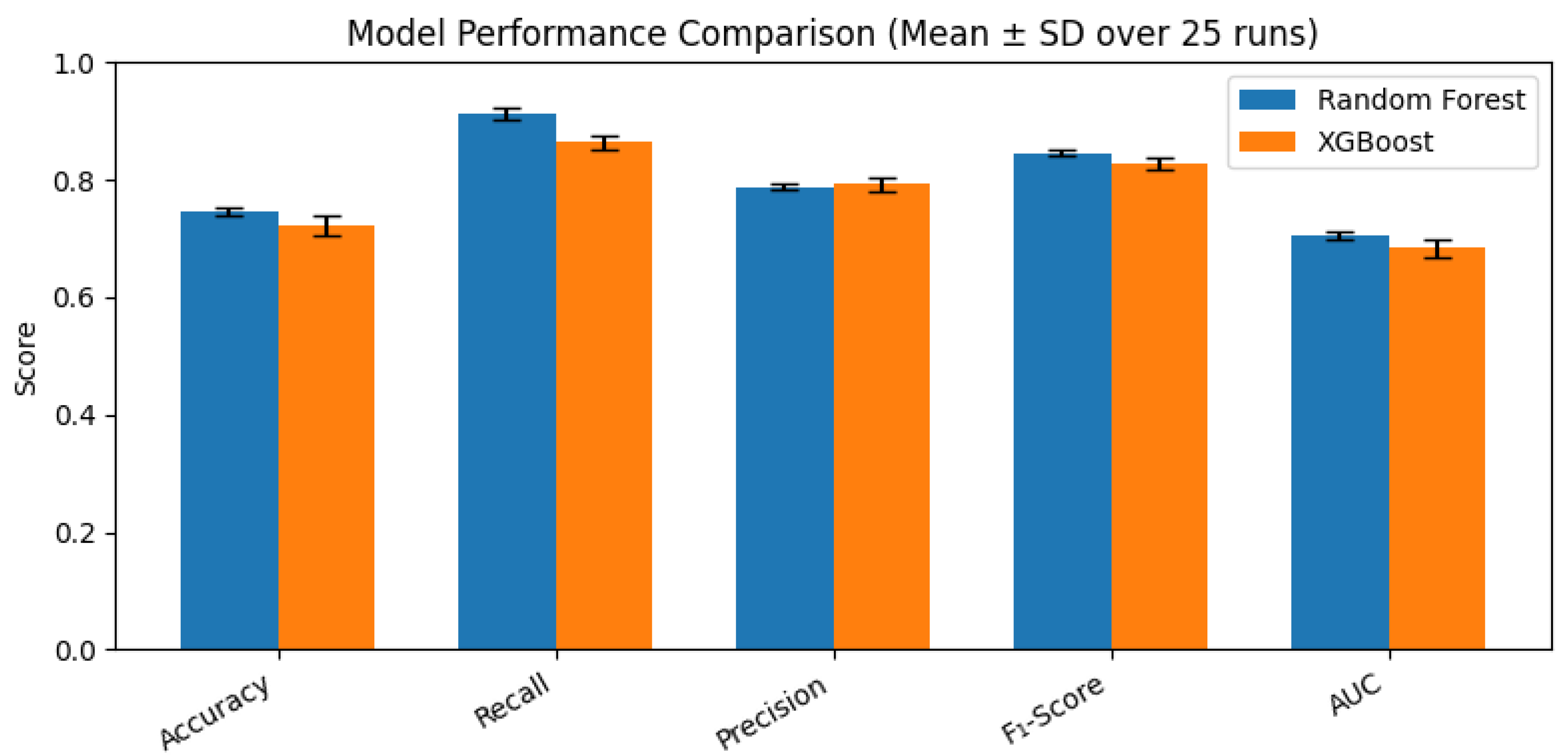

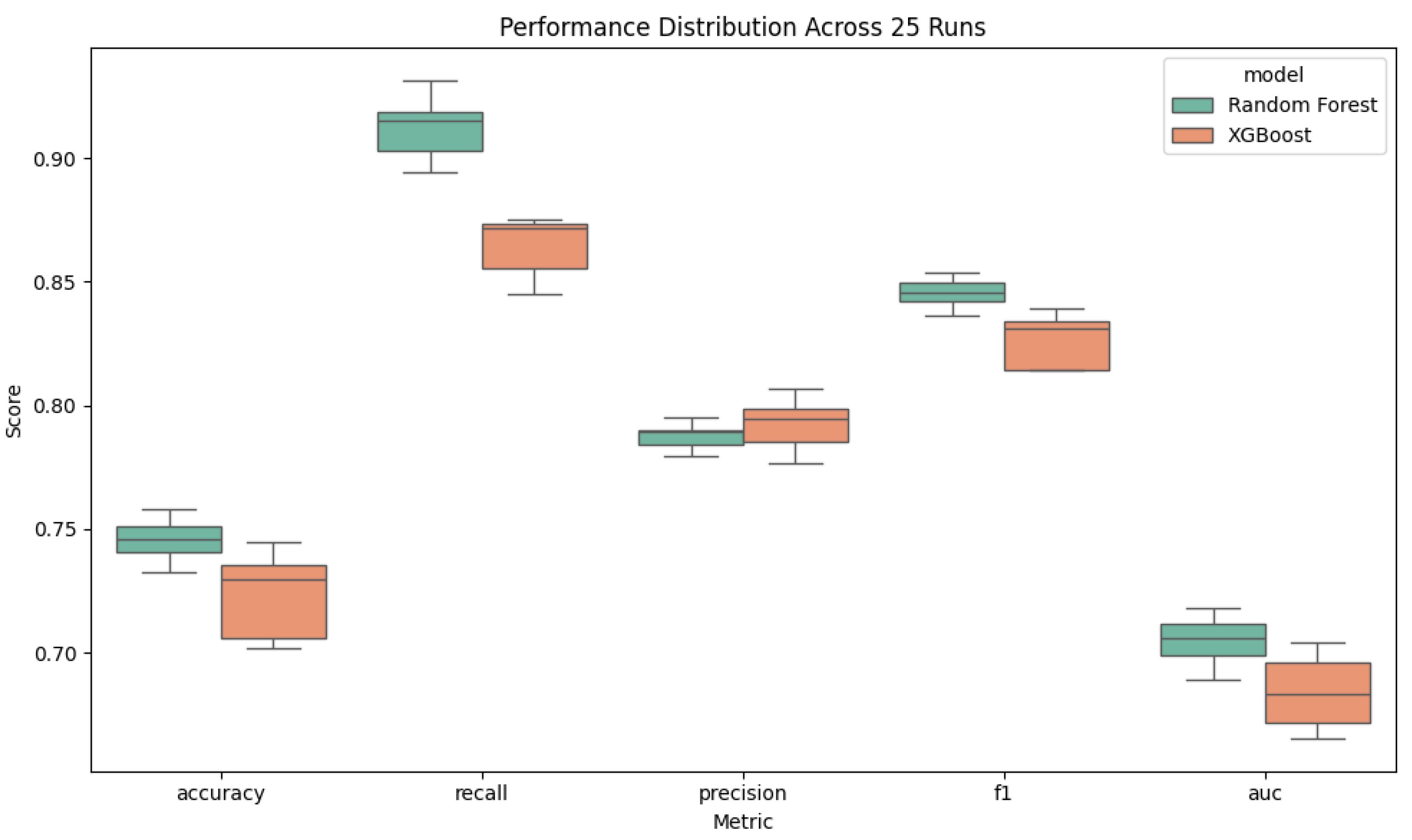

Across 25 stratified 60/20/20 train–validation–test splits (five seeds × five trials), the Random Forest classifier consistently delivered high performance in identifying severe periodontitis. As shown in

Table 1, performance metrics were accuracy = .74 (

SD = .01), sensitivity = .91 (

SD = .01), precision = .79 (

SD = .00), F₁-score = .84 (

SD = .01), and discrimination (AUC) = .70 (

SD = .01). This robust design ensures results are not driven by any single partition.

Explainability via SHAP further validated clinical relevance. The global importance bar chart (

Figure 5) highlights age, body-mass index, and systolic blood pressure consistent with known risk factors as the strongest predictors of severe disease. The SHAP beeswarm plot (

Figure 6) confirms that higher values of these features consistently push individual predictions toward “severe,” while smoking status and diastolic blood pressure exert moderate influence, and diabetes status and gender smaller, yet still meaningful, effects. A SHAP dependence plot for age × gender (

Figure 7) reveals that advancing age increases predicted risk more steeply for males than for females. On one representative hold-out fold (n = 744;

Figure 4), the confusion matrix showed a 9% false-negative rate (71 of 568 severe cases missed), acceptable for screening. Patient-level SHAP explanations for misclassifications illuminate precisely why those errors occurred, offering clinicians transparent insights into each decision.

Together, these findings demonstrate that Random Forest not only performs reliably but does so with transparent, clinically sensible logic fulfilling the promise of Application of Explainable AI (XAI) in Periodontal Disease Risk Assessment.

5. Discussion

Interpretation of Key Findings

In this study, I developed and rigorously evaluated an explainable XGBoost model for predicting severe periodontal disease using seven readily available predictors age, gender, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, diabetes status, and smoking status from the 2013–2014 NHANES dataset. By repeating a stratified 60/20/20 train/validation/test split over five random seeds with five trials each (25 total runs), Random Forest outperformed XGBoost (accuracy = .74 vs. .72; recall = .91 vs. .86; AUC = .70 vs. .68). These tight performance intervals illustrated by narrow box plots demonstrate the model’s robustness to different data partitions. Notably, the consistency of feature importance across all 25 runs suggests that these predictors are not only statistically significant but also biologically plausible drivers of periodontal breakdown. This stability in variable ranking implies that the model is capturing genuine relationships rather than overfitting noise in the data.

Equally important, I used SHAP to interpret the global feature-importance bar chart (

Figure 5) . It confirmed that age, body-mass index, and systolic blood pressure were the dominant risk factors, exactly as clinical experience suggests. A SHAP dependence plot further revealed that the marginal effect of age on risk rises more steeply in men than in women, particularly after age 60. Finally, when I retrained the chosen model on combined training + validation data and evaluated it on a held-out test fold, the confusion matrix showed a false-negative rate of 9% (71 of 568 severe cases), ensuring that most high-risk patients would be correctly identified for early intervention.

Clinical Relevance of Predictors and Comparison to Prior Work

Our SHAP analyses not only identified which features drive severe periodontitis risk but also underscored their clinical importance in guiding preventive and therapeutic strategies. By quantifying the marginal contribution of each predictor, clinicians can better prioritize modifiable risk factors such as hypertension or obesity through targeted patient education and appropriate medical referrals. For example, a patient with high systolic blood pressure and elevated BMI could be counseled on lifestyle changes and referred for cardiovascular evaluation, thereby addressing both systemic and oral health concerns.

Furthermore, the steep age–gender interaction revealed by SHAP highlights an opportunity for sex-specific screening guidelines. Our dependence plot showed that advancing age increases predicted risk more sharply in men than in women, suggesting that dental providers might consider recommending earlier or more frequent periodontal assessments for male patients as they enter late middle age. This insight could inform personalized care plans and help prevent the progression of severe disease.

Compared to prior AI applications in periodontology, which have often relied on specialized inputs such as salivary biomarkers or radiographic imaging, our model fills a critical gap by leveraging routinely collected vital signs and demographic information. Unlike resource-intensive approaches, our reliance on NHANES variables makes wide-scale implementation feasible in primary-care settings and community health programs. Moreover, our findings extend the literature by demonstrating that even without advanced laboratory measures, a parsimonious, explainable model can achieve performance comparable to more complex methods. This balance of accuracy, interpretability, and practicality positions our approach as a promising tool for early risk screening in both dental offices and broader public health initiatives.

Limitations

Despite these encouraging results, there are several limitations. First, relying on a single NHANES cycle may not capture trends over time or regional differences in periodontal health. Second, some potentially valuable predictors such as flossing frequency and dental visit history were excluded due to missing data, which might slightly undercut model accuracy. Third, collapsing mild and moderate cases into a single “non-severe” category simplifies the problem but sacrifices nuance; future work could explore a multiclass approach to stage disease progression more finely. Finally, although NHANES is nationally representative, clinical validation on independent dental or electronic health record datasets is still needed to confirm real-world performance. Because its data are cross-sectional, our model cannot capture changes in individual risk over time; longitudinal validation would help determine its value in monitoring disease progression. The exclusion of socioeconomic variables may have masked important social determinants of periodontal health; future models should explore proxies for income and education to address health disparities.

Future Directions

To address these gaps, I plan to incorporate additional NHANES cycles and collaborate with dental clinics to test the model on localized EHR data. Enriching the feature set with behavioral, socioeconomic, or genetic markers could uncover new risk interactions and further boost predictive power. I also aim to wrap this pipeline into a user-friendly web or mobile application, so that dentists can visualize patient-specific risk profiles and SHAP explanations at the point of care. To facilitate real-world uptake, I plan to pilot the model within a university-affiliated dental clinic and measure its impact on referral rates and early treatment outcomes. Enhancing the user interface with interactive SHAP visuals will allow providers to simulate ‘what-if’ scenarios (e.g., the effect of smoking cessation) and engage patients in goal setting.

Ethical Considerations

As AI tools become more common in healthcare and dentistry, it is important to think about how they are used fairly and responsibly. One concern is that if a model is trained on data that does not represent all kinds of people, its predictions may not be fair for everyone. In this study, I used data from NHANES because it is standardized and publicly available, but future models should make sure they include people from different backgrounds. Another important point is that patients and dentists should be able to understand how a model makes decisions. Using explainable tools like SHAP helps make the model’s predictions clearer and more trustworthy. Finally, AI should be used to help healthcare providers not replace them. It is important that we keep humans in control of important health decisions. Ongoing audits for algorithmic bias will be necessary to ensure the model does not systematically underpredict risk in marginalized populations. Implementing a feedback loop where clinicians can flag incorrect predictions will help retrain and improve the model over time, embedding ethical oversight into its lifecycle.

Importance and Implications

This study shows that explainable AI tools like SHAP can make machine learning models more transparent and easier to understand in a clinical setting. Knowing which factors contribute to a patient’s risk of severe gum disease can help guide prevention and treatment. Models like this could be used in public health screenings, dental offices, or even as part of mobile health tools. By offering early warnings and personalized insights, this work has the potential to improve oral health outcomes and reduce long-term complications. By democratizing access to advanced analytics, such explainable models can help reduce the gap between academic research and routine clinical practice. This work underscores how transparency, rather than opacity, can drive clinician confidence and patient engagement in AI-guided care.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a default-parameter Random Forest classifier, when rigorously evaluated across multiple random seeds and trials, can accurately and transparently identify individuals at high risk for severe periodontitis using simple, routinely collected predictors. By integrating SHAP explanations into the modeling pipeline, we not only achieved reliable predictive performance (accuracy = .74, sensitivity = .91, AUC = .70) but also uncovered clear, patient-level insights into which factors such as age, body-mass index, and systolic blood pressure drive risk estimates. These explanations bridge the gap between “black box” algorithms and clinical decision-making, empowering providers to understand and trust model outputs.

The implications of our findings are twofold. First, the demonstrated stability of model performance across 25 data partitions underscores its potential for real-world deployment in dental and medical settings, where robustness to changing patient cohorts is essential. Second, by offering interactive SHAP visualizations, clinicians can engage patients in informed discussions about modifiable risk factors fostering shared decision-making and motivating preventive behavior changes (e.g., smoking cessation, weight management). In this way, the model becomes not just a predictive tool but a catalyst for personalized care pathways.

Looking ahead, the successful application of explainable AI in this context suggests broader opportunities across healthcare domains. Any clinical scenario that relies on risk stratification whether predicting cardiovascular events, identifying patients at risk for diabetic complications, or triaging dermatological lesions stands to benefit from the combination of rigorous validation and transparent interpretation. The key will be to maintain a balance between model complexity and interpretability, ensuring that advanced algorithms remain accessible to end users.

Ultimately, fulfilling the promise of Application of Explainable AI (XAI) in Periodontal Disease Risk Assessment will require ongoing collaboration between data scientists, clinicians, and patients. By continuing to refine algorithmic fairness, integrating additional data sources, and embedding these tools into electronic health records and mobile platforms, we can transform explainable AI from an academic exercise into an indispensable component of preventive dentistry and beyond.