1. Introduction

Postpartum perineal pain and discomfort are common, particularly after episiotomy [

1]. This may discourage future vaginal deliveries [

2]. These wounds typically result in discomfort, stinging, and conditions like vulvodynia [

3]. Effective wound care solutions are essential for improving maternal recovery and quality of life.

Vaginitis during pregnancy can negatively impact pregnancy outcomes, leading to complications such as preterm labor, chorioamnionitis, premature rupture of membranes, neonatal infections, and postpartum endometritis [

3].

Episiotomy, a surgical incision of the perineum during vaginal delivery, is frequently performed to facilitate childbirth and prevent severe perineal tears [

4,

5]. However, wound healing following episiotomy remains a significant concern for postpartum recovery, affecting maternal well-being and quality of life [

6].

Episiotomy, a common obstetric intervention, can affect postpartum sexual well-being depending on the quality of wound healing [

7].

The rates of episiotomy are alarmingly high, exceeding 60% in countries such as Cyprus, Portugal, Romania, and Poland. In stark contrast, Denmark, Sweden, and Iceland demonstrate a more progressive approach with rates below 10% [

8]. This striking disparity highlights the need for a reassessment of practices in maternal care to promote safer and more effective childbirth experiences [

9].

Postpartum sexual dysfunction is a prevalent issue, with a multitude of factors influencing recovery, including education level, age, and number of births [

10]. It is crucial to understand how these factors interact with wound healing, as this knowledge can provide valuable insights into improving postpartum care and ensuring comprehensive support for new mothers [

11].

While spontaneous healing is the standard approach, interventions such as lactic acid have been proposed to accelerate tissue regeneration and reduce discomfort [

12].

Lactic acid, with its known antimicrobial and regenerative properties, holds promise for improved wound healing [

13]. While previous studies have explored the role of lactic acid bacteria and probiotics in tissue regeneration, more research is needed to fully understand the direct impact of lactic acid in episiotomy healing [

14].

Previous research suggests that lactic acid may support vaginal microbiota balance, maintain physiological pH, and modulate local inflammation, which could contribute to improved wound healing and pain reduction. In this study, we evaluated the potential benefits of intravaginal lactic acid gel (Canesbalance®, Bayer) in post-episiotomy healing.

2. Materials and Methods

After obtaining the consent of the university's ethics board and the hospital's ethics board, we enrolled 100 patients who signed an informed consent form in the study. This study was registered on MedPath, Registration Number NCT06978049 (

https://trial.medpath.com/clinical-trial/a8b6ae7627f16be2/nct06978049-lactic-acid-gel-post-episiotomy-discomfort) and on ClinicalTrials.gov), NCT Number NCT06978049 (

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06978049?term=NCT06978049&rank=1&tab=table). The study, an experimental prospective study starting on 01.02.2023, was designed with the utmost respect for ethical considerations, following ICH-GCP guidelines, Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Ethics Committees of Saint Andrew Hospital, and registered 7230/31.01.2023. The intervention group included 50 patients who received intravaginal lactic acid gel (Canesbalance®, Bayer AG, Germany), a formulation containing lactic acid, glycogen, and polycarbophil, designed to restore and maintain physiological vaginal pH. The product was administered using pre-filled 5 mL applicators, once daily for seven consecutive days, starting on postpartum day 1. The control group consisted of 50 patients who received no intervention All interventions were performed by standardized medical teams using the same episiotomy technique (right medio-lateral episiotomy) to ensure the uniformity of the procedure and the highest level of patient care. Participants were randomized (1:1) using a computer-generated sequence (randomization.org.) The intervention group received intravaginal lactic acid gel (Canesbalance®, Bayer AG, Germany), (7 applicators × 5 mL, once daily for 7 days, beginning on day 1 postpartum. The control group received standard postpartum care without gel application. Outcome assessors were not blinded; however, data were anonymized and analyzed by a blinded statistician.

Scar healing was evaluated at day 7 and day 40 postpartum using the following validated scales: POSAS, VAS, and NRS. Blood samples were collected to assess hemoglobin, hematocrit, leukocytes, and platelets.

Statistical analysis was performed using independent t-tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

A dedicated statistician interpreted the data, ensuring a blind process and eliminating bias. The study concluded on 31.12.2024.

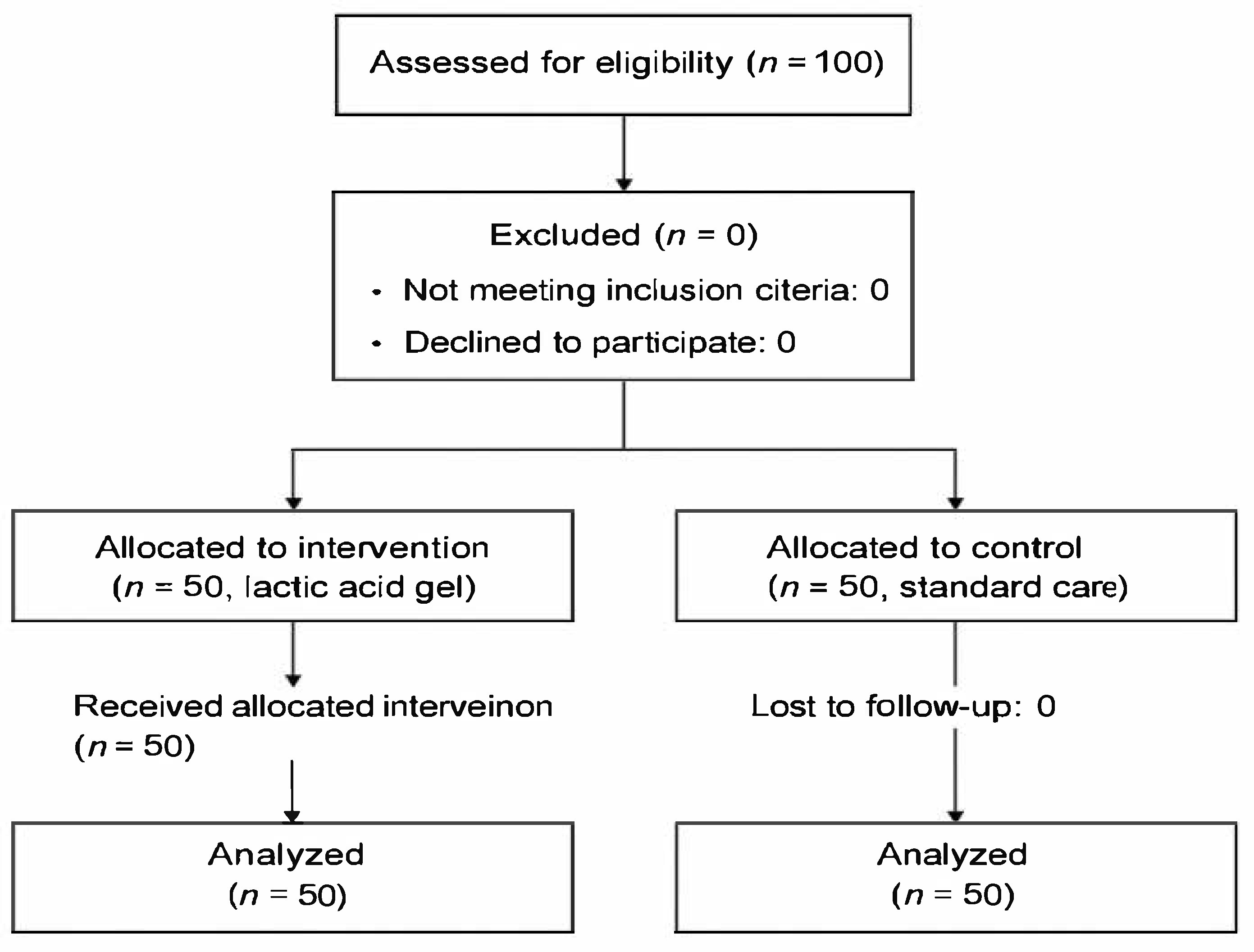

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant recruitment and allocation.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant recruitment and allocation.

Women aged ≥18 years, primiparous or second-parous, with singleton term pregnancies (38–40 weeks) and mediolateral episiotomy during vaginal delivery, were eligible as seen in

Table 1.

Patients were excluded for diabetes (gestational or type II), psychiatric or systemic hematologic disease, communicable diseases (e.g., HIV, HBV, HCV, syphilis), skin disease, or heparin intolerance.

2.1. Statistical Analysis:

3. Results

As shown in

Table 2 demographic characteristics were balanced between groups. No significant differences were observed in baseline age, parity, or gestational age.Hematological parameters (hemoglobin, hematocrit, leukocyte count, platelet count) did not show significant intergroup differences at either 7 or 40 days. Scar assessment scales showed significant improvement in the intervention group between day 7 and day 40 (p < 0.05). Pain scores (VAS, NRS) were lower in the treatment group at 40 days, with significant reductions compared to control.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the potential benefits of intravaginal lactic acid gel application on scar healing and pain reduction after mediolateral episiotomy. Canesbalance® (Bayer AG, Germany), primarily indicated for vaginal pH regulation and bacterial vaginosis management, contains lactic acid known for its antimicrobial properties and local pH-modulating effects. Maintaining an acidic environment postpartum may play a role in limiting pathogenic bacterial colonization, supporting the vaginal microbiome, and reducing local inflammation — factors that could potentially contribute to improved tissue regeneration. Lactic acid, a key component of the physiological vaginal environment, possesses antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and regenerative properties. Its topical application may modulate local pH, inhibit pathogen proliferation, and promote tissue remodeling — mechanisms that could be harnessed to improve episiotomy healing outcomes [

13,

14].

Episiotomy, a routine obstetric intervention, facilitates vaginal delivery but remains a major contributor to postpartum perineal morbidity [

1]. Despite a global trend towards restrictive episiotomy practices, rates remain alarmingly high in several European countries, including Romania, highlighting an urgent need for optimized postpartum care strategies [

7,

9].

We evaluated the treatment's impact on hematological parameters, scar healing, and pain outcomes at 7- and 40-days post-intervention. Several other studies have observed episiotomy wound healing [

15,

16,

17].

4.1. Hematological Parameters

Hemoglobin and Hematocrit: These parameters reflect tissue oxygenation and recovery from blood loss during birth. An increase in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels indicates effective tissue regeneration [

18,

19]. Hemoglobin Levels: At 7 days post-treatment, the treated group demonstrated a slightly higher mean hemoglobin level (M = 11.30 ± 1.07 g/dL) than the control group (M = 10.98 ± 0.95 g/dL). However, the difference was not statistically significant (p =0.125). By day 40, hemoglobin levels had increased similarly in both groups (Treated: M =12.96 ± 1.01 g/dL, Control: M = 12.99 ± 1.01 g/dL, p = 0.896), suggesting that the treatment did not significantly impact long-term hemoglobin restoration. Hematocrit Levels: The hematocrit levels followed a similar trend. At 7 days, the treated group had a mean hematocrit of 34.64 ± 5.29%, compared to 35.91 ± 5.05% in the control group (p = 0.222). By 40 days, hematocrit levels had increased in both groups (Treated: 39.53 ± 5.20%, Control: 40.43 ± 5.08%, p = 0.385). These findings suggest that the physiological recovery of hematocrit is independent of the treatment.

Leukocytes: Increased values of this parameter indicate an inflammatory response [

20]. Leukocyte Count: At 7 days, the treated group exhibited a higher leukocyte count (M = 11,863.68 ± 1,826.52 cells/dL) compared to the control group (M = 11,287.21 ± 2,061.63 cells/dL), though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.142). This elevation in the treated group may be indicative of an early inflammatory response triggered by the intervention. By 40 days, leukocyte counts decreased in both groups to baseline levels, further supporting that any initial immune response was transient [

21,

22,

23].

Platelets: Evaluation of platelets is essential as they release growth factors involved in tissue regeneration [

24].

4.2. Scar Healing Outcomes

POSAS (Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale): This scale provides a comprehensive assessment that includes the scar's appearance and the symptoms experienced by the patient, such as itching and pain. Scar Score: The treated group had lower scar scores at 40 days (M = 4.89 ± 1.15) compared to the control group (M = 6.18 ± 1.32), with a statistically significant difference (p> 0.01). The reduction in scar scores suggests that the treatment may have positively influenced the wound-healing process by modulating inflammatory and fibrotic pathways. Those findings were similar to other findings in the literature [

25,

26,

27]. The accelerated reduction in scar severity in the treated group may be attributed to improved angiogenesis or reduced fibrotic tissue deposition. Further research incorporating histological and molecular analyses could elucidate the exact mechanisms underlying these findings [

28].

VAS (Visual Analog Scale): This is a self-assessment scale for the patient to rate the pain experienced. VAS Pain Score: At 7 days, the treated group reported slightly higher pain scores (M = 5.26 ± 1.89) compared to the control group (M = 4.97 ± 1.75, p = 0.208). However, by 40 days, the treated group exhibited a significantly more significant reduction in pain scores (M = 1.82 ± 0.94) compared to the control group (M = 3.01 ± 1.12, p < 0.05), suggesting enhanced long-term pain relief. VAS score was similar in other studies that studied the use of lactic acid in wound healing [

29,

30].

NRS (Numeric Rating Scale): Another numerical scale for self-rating pain. NRS Pain Score: A similar trend was observed in the numerical rating scale (NRS) for pain. At 7 days, the treated group had higher NRS scores (M = 3.92 ± 1.78) than the control group (M = 3.45 ± 1.52), with no significant difference (p = 0.341). However, by day 40, the treated group reported significantly lower pain (M = 1.21 ± 0.86) compared to the control group (M = 2.65 ± 1.03, p> 0.01), indicating a more substantial analgesic effect. Our findings were similar to other medical literature studies [

30,

31].

4.3. Statistical Implications

Despite the lack of statistical significance in hematological parameters, the trend observed suggests that the intervention does not impair normal recovery processes.

The significantly lower scar scores and pain reduction in the treated group at 40 days highlight the treatment's potential efficacy in promoting wound healing and long-term comfort.

Effect sizes (Cohen's d) for scar score and pain reduction were moderate to high, further supporting the clinical relevance of these findings.

Future studies incorporating a larger sample size and randomized controlled trial (RCT) design are warranted to confirm these results and explore underlying mechanisms.

The study findings suggest that while the treatment does not significantly impact hematological recovery, it benefits scar healing and long-term pain reduction. Patients receiving the treatment exhibited significantly lower scar scores and more significant reductions in pain scores by 40 days post-intervention, indicating its potential clinical relevance.

Primiparous patients exhibited slightly higher pain and scar scores at both time points, likely due to tissue rigidity and first-time stretching trauma. Multiparous patients had a faster recovery trajectory, benefiting from prior adaptation to vaginal delivery. Age did not significantly influence healing rates, indicating that the gel's efficacy is independent of maternal age.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The research was conducted in a single center with a relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. The lack of blinding of outcome assessors and participants introduces the possibility of performance and detection bias. Additionally, the statistical analysis was limited to basic comparisons without adjustment for potential confounding factors such as body mass index, smoking status, or socioeconomic background, which could influence wound healing outcomes.

Moreover, the trial registration process was ongoing at the time of manuscript submission, and the registration number will need to be confirmed to ensure compliance with clinical trial reporting standards. Finally, important biological parameters such as local inflammatory markers and vaginal microbiota composition were not assessed, which limits the understanding of the biological mechanisms that may underlie the observed clinical effects.

Although Canesbalance® is primarily indicated for vaginal pH regulation and bacterial vaginosis management, its lactic acid content may exert local anti-inflammatory and regenerative effects. Our findings suggest that this approach could be beneficial in the context of episiotomy wound healing, although further research is warranted.

5. Conclusions

This randomized trial demonstrates that intravaginal lactic acid gel application post-episiotomy may accelerate wound healing and significantly reduce long-term pain, with no detectable adverse hematological effects. These findings suggest a potential paradigm shift in postpartum care by leveraging physiological agents to optimize recovery outcomes.

However, considering the single-center design, modest sample size, and limited biomarker analysis, these results should be interpreted cautiously. Larger, multicenter trials integrating microbiological and inflammatory marker assessments are urgently needed to validate these results and elucidate the molecular pathways involved.

If confirmed, intravaginal lactic acid gel could be established as a simple, safe, and cost-effective adjunct to postpartum care, enhancing the quality of life for millions of new mothers worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B. and A.B.; methodology, V.T.; software, S.C.; validation, S.C., formal analysis, S.C.; investigation, D.B.; resources, A.B.; data curation, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.; writing—review and editing, V.T.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Written Informed Consent

Has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Bayer AG for providing the Canesbalance® product used in this study. The company had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, manuscript preparation, or decision to publish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Bayer AG had no influence on the study conduct, data interpretation, or publication process.

References

- Choudhari, R.G.; Tayade, S.A.; Venurkar, S.V.; Deshpande, V.P. A Review of Episiotomy and Modalities for Relief of Episiotomy Pain. Cureus 2022, 14, e31620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qian, X.; Carroli, G.; Garner, P. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2, CD000081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro, S. Vaginitis and pregnancy. J. Reprod. Med. 1989, 34 (Suppl. 8), 602–604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carroli, G.; Mignini, L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, 21, CD000081. [Google Scholar]

- Barjon, K.; Vadakekut, E.S.; Mahdy, H. Episiotomy, In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing, [Updated 2024 Oct 6].

- Choudhari, R.G.; Tayade, S.A.; Venurkar, S.V.; Deshpande, V.P. A Review of Episiotomy and Modalities for Relief of Episiotomy Pain. Cureus 2022, 14, e31620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Hartmann, K.; Palmieri, R.; et al. The Use of Episiotomy in Obstetrical Care: A Systematic Review: Summary. In: AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2005 May, 112.

- Blondel, B.; Alexander, S.; Bjarnadóttir, R.I.; Gissler, M.; Langhoff-Roos, J.; Novak-Antolič, Ž.; Prunet, C.; Zhang, W.H.; Hindori-Mohangoo, A.D.; Zeitlin, J. Euro-Peristat Scientific Committee. Variations in rates of severe perineal tears and episiotomies in 20 European countries: A study based on routine national data in Euro-Peristat Project. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016, 95, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve Maternal Health [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020 Dec. 4, STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS: IMPROVING MATERNAL HEALTH AND REDUCING MATERNAL MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY.

- Donarska, J.; Burdecka, J.; Kwiatkowska, W.; Szablewska, A.; Czerwińska-Osipiak, A. Factors affecting for women’s sexual functioning after childbirth-pilot study. European Journal of Midwifery 2023, 7 Suppl. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Y.J.; Miller, M.L.; Agbenyo, J.S.; Ehla, E.E.; Clinton, G.A. Postpartum care needs assessment: women's understanding of postpartum care, practices, barriers, and educational needs. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023, 23, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olteanu, G.; Neacșu, S.M.; Joița, F.A.; Musuc, A.M.; Lupu, E.C.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.B.; Lupuliasa, D.; Mititelu, M. Advancements in Regenerative Hydrogels in Skin Wound Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, P. R. P.; Balachander, N.K. Anti-inflammatory and wound healing properties of lactic acid bacteria and its peptides. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2023, 68, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bădăluță, V.A.; Curuțiu, C.; Dițu, L.M.; Holban, A.M.; Lazăr, V. Probiotics in Wound Healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; et al. The role of lactic acid in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2020, 28, 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.; et al. Collagen-based therapies for wound recovery: A systematic review. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 12, 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.; et al. The effect of lactic acid on fibroblast proliferation in wound healing. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Elizalde, J.I.; et al. Early changes in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels after packed red cell transfusion in patients with acute anemia. Transfusion 1997, 37, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, R.S.; Bennett-Guerrero, E. Impact of red blood cell transfusion on global and regional measures of oxygenation. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2012, 79, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; et al. Lactic acid modulation of inflammatory response in tissue repair. Adv. Wound Care 2022, 11, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, L.; et al. Collagen hydrogel in enhancing wound tensile strength. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 145, 1342–1354. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.; et al. Comparative analysis of lactic acid and hyaluronic acid in wound healing. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2021, 109, 478–491. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, A.; et al. Clinical efficacy of collagen dressings in surgical wounds. Int. Wound J. 2022, 19, 564–573. [Google Scholar]

- Nurden, A.T. Platelets, inflammation and tissue regeneration. Thromb. Haemost. 2011, 105 (Suppl. 1), S13–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, B.; et al. The impact of collagen supplementation on post-surgical wound healing. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2045. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.; et al. The role of bioactive peptides in lactic acid and collagen-mediated wound repair. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D.; et al. Lactic acid and collagen: Synergistic effects on fibroblast migration. J. Wound Manag. 2020, 19, 745–758. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P.; et al. The use of lactic acid-based formulations in post-surgical scar reduction. Dermatol. Surg. 2022, 48, 673–685. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, H.; et al. Lactic acid in dermal wound modulation and infection control. Wound Care Today 2020, 18, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, L.; et al. Clinical benefits of combining lactic acid and collagen in wound healing. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, R.; et al. Role of exogenous collagen in tissue remodeling post-episiotomy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 2021, 47, 3541–3553. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).