1. Introduction

Anthurium plants are notable for the aesthetic appeal of their leaves and flowers. Their vibrant colors and variety across species make them widely popular for decorative purposes. This beauty has granted

Anthuriums significant commercial value in the global ornamental flower market [

1], especially the popular

Anthurium clarinervium Matuda, known as “Hua Jai Lai” or “Millionaire’s Heart” in Thailand. This species is particularly well-suited to Thailand’s hot and humid climate and is often grown for its foliage, as its large leaves remain fresh in vases for 5-8 weeks. The sizable, heart-shaped leaves with prominent white veins radiating from the center make it highly sought after, with prices ranging from 2.3-3.0 USD per leaf or 23.0-30.0 USD per potted plant. However,

A. clarinervium production faces challenges due to its seed propagation method, which results in low germination rates and limited seedling production. Seed germination in

Anthurium species is challenging due to slow and inconsistent sprouting and low germination percentages. This may be due to the sticky coating on mature

Anthurium seeds, which hinders germination and reduces seedling survival rates if seeds are sown immediately after harvest.

Seed enhancement methods improve the quality of seeds post-harvest by achieving high, consistent germination, which is essential for cultivating many plant types. Seed priming, a physiological technique to enhance seed quality, involves hydrating the seeds to initiate germination but stopping short of radicle emergence. Priming enhances germination, reduces germination time, and improves seedling vigor, leading to better yields compared to unprimed seeds. This technique also mitigates adverse environmental impacts on seed germination, which are common challenges in current cultivation practices. Seed priming techniques are well-documented for various plant species, showing increased seed viability, higher germination percentages, and early seedling growth [2-3]. Priming involves hydrating seeds just enough to support germination without triggering radicle growth, allowing seeds to sprout uniformly [

4]. After priming, seeds are dried back to initial moisture levels, pausing germination and enabling short-term storage [

5]. Once rehydrated, primed seeds germinate more quickly and consistently [

6].

Various seed priming techniques include osmopriming (using osmotic agents), solid matrix priming (using moisture-retaining materials), and hydropriming (soaking seeds in water) [

7]. Seed priming strengthens seedlings and supports growth in unfavorable environments, enhancing germination. Priming agents include water and various solutions like PEG6000, KNO

3, KCl, NaCl, and Vitamin C, which improve germination rates, increase speed indices, and enhance seedling robustness compared to unprimed seeds [

8]. For example, a study on hydropriming buckwheat seeds at 30°C for 18 hours achieved a 90.50% germination rate compared to 82.50% for unprimed seeds [

9]. Chemical priming agents each have distinct compositions and properties; for instance, KNO3 provides nitrogen and essential nutrients that promote protein synthesis during germination, while salicylic acid (SA) enhances seed germination capacity [

10]. Additionally, wood vinegar, which contains butenolide and ethylene from combustion, is known to stimulate seed germination [

11]. Kaewsorn et al. [

12] primed chili seeds using SA, wood vinegar, and KNO

3. A 3% KNO

3 solution soaked for 24 hours yielded the highest germination rates and shortest germination time compared to other priming methods.

Thus, studying the effects of seed priming on germination and seedling growth in A. clarinervium is essential for enhancing seedling viability, growth rates, and yield. This study examines suitable priming techniques for A. clarinervium, providing essential data for farmers and growers. This approach contributes to the sustainable cultivation of A. clarinervium, supporting both local agriculture and market demand.

2. Results

2.1. Seed Quality

2.1.1. Germination Percentage

The results indicated no interaction effect between seed preparation, plant growth stimulants, and water temperature. However, there was a statistically significant difference in seed preparation and water temperature (p<0.01) with a 99% confidence level. Seeds sown immediately after extraction, treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:2 ratio, and soaked at 27°C showed the highest average germination percentage of 87.00%. This was statistically comparable to treatments where seeds were sown immediately after extraction, treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:2 ratio, and soaked at 50 and 70°C, as well as treatments using Phytonova+Germaplus at 1:1 and 2:1 ratios across all three temperatures. In contrast, treatments where seeds were left for seven days before sowing and treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at 1:1, 2:1, and 1:2 ratios at 70°C showed statistically significant differences.

2.1.2. Average Germination Time

There was an interaction effect between seed preparation, plant growth stimulants, and water temperature. Both plant growth stimulants and water temperature, as well as seed preparation and water temperature, showed interaction effects. Water temperature alone had a statistically significant effect (p<0.01) with a 99% confidence level. Seeds sown immediately after extraction, treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:1 ratio, and soaked at 50°C showed the shortest average germination time of 13.86 days. This was statistically similar to seeds sown immediately after extraction, treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:2 ratio, and soaked at 27, 50, and 70°C, as well as treatments with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:1 ratio at 70°C, and at a 2:1 ratio at 50 and 70°C. However, it differed significantly from other treatments, including seeds left for seven days and treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at various ratios and temperatures.

2.1.3. Germination Speed Index

There was no interaction effect between seed preparation, plant growth stimulants, and water temperature. However, seed preparation and water temperature had a statistically significant effect (

p<0.01) with a 99% confidence level. The highest average germination speed index of 0.99 was observed in seeds sown immediately after extraction, treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:2 ratio, and soaked at 27°C. This was statistically similar to treatments involving immediate sowing and Phytonova+Germaplus at various ratios and temperatures. In contrast, seeds left for seven days and treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at 1:1 and 1:2 ratios at 70°C had the lowest average germination speed index of 0.05 (

Table 1).

2.2. Seedling Growth

2.2.1. Leaf Length

There was no interaction effect between seed preparation, plant growth stimulants, and water temperature on leaf length. However, seed preparation and water temperature showed statistically significant differences (p<0.01) at a 99% confidence level. The highest average leaf length of 4.64 cm was observed in seeds sown immediately after extraction, treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:2 ratio, and soaked at 50°C. This was statistically similar to treatments with seeds soaked at 27°C, using Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:1 and 1:2 ratio across various temperatures, and seeds left for seven days with Phytonova+Germaplus at 2:1 and 1:2 ratios at lower temperatures. In contrast, treatments involving immediate sowing with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:2 ratio at 70°C showed statistically significant differences.

2.2.2. Leaf Width

No interaction was observed between seed preparation, plant growth stimulants, and water temperature on leaf width. However, significant differences were found in seed preparation and water temperature (p<0.01) at a 99% confidence level. The highest average leaf width of 4.49 cm was achieved with seeds sown immediately after extraction, treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:2 ratio, and soaked at 50°C. This was statistically comparable to various other treatments at 27 and 50°C with Phytonova+Germaplus ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1. In contrast, seeds treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at 1:2 at 70°C showed significant differences.

2.2.3. Plant Height

There was no interaction effect between seed preparation, plant growth stimulants, and water temperature on plant height. Significant differences were observed for seed preparation and water temperature (p<0.01) at a 99% confidence level. The highest average plant height, 9.81 cm, was recorded in seeds sown immediately after extraction, treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:2 ratio, and soaked at 50°C. This was statistically similar to treatments across various temperatures and ratios of Phytonova+Germaplus, excluding those using Phytonova+Germaplus at 1:2 soaked at 70°C, which showed statistically significant differences.

2.2.4. Root Length

No interaction effect was observed between seed preparation, plant growth stimulants, and water temperature on root length. Significant differences were found for seed preparation and water temperature (

p<0.01) at a 99% confidence level. The highest average root length, 13.79 cm, was obtained from seeds sown immediately after extraction, treated with Phytonova+Germaplus at a 1:2 ratio, and soaked at 50°C. This was statistically similar to other treatments across lower temperatures and varying ratios of Phytonova+Germaplus. However, significant differences were noted with treatments involving seeds soaked at 70°C with Phytonova+Germaplus at 1:1, 2:1, and 1:2 ratios (

Table 2).

2.3. Correlation and Principal Component Analysis

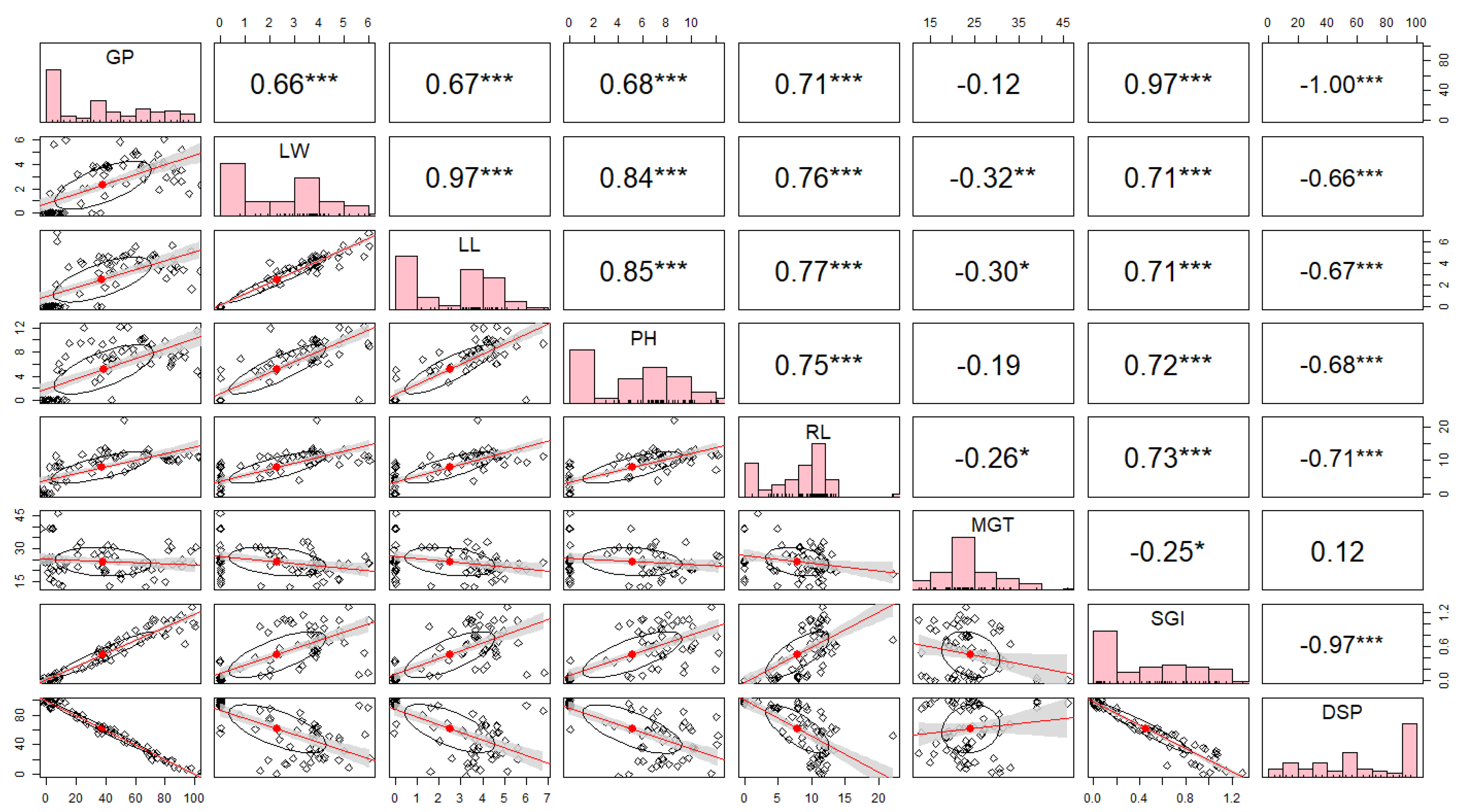

The study of correlation coefficients of seed quality traits and growth characteristics (eight traits) revealed that germination speed index (r=0.97), root length (r=0.71), plant height (r=0.68), leaf length (r=0.67), and leaf width (r=0.66) were positively correlated with germination percentage at a statistically significant level. Leaf length (r=0.97), plant height (r=0.84), root length (r=0.76), and germination speed index (r=0.71) were positively correlated with leaf width. It was also found that the percentage of dead seeds and the average germination days were negatively correlated with all traits (

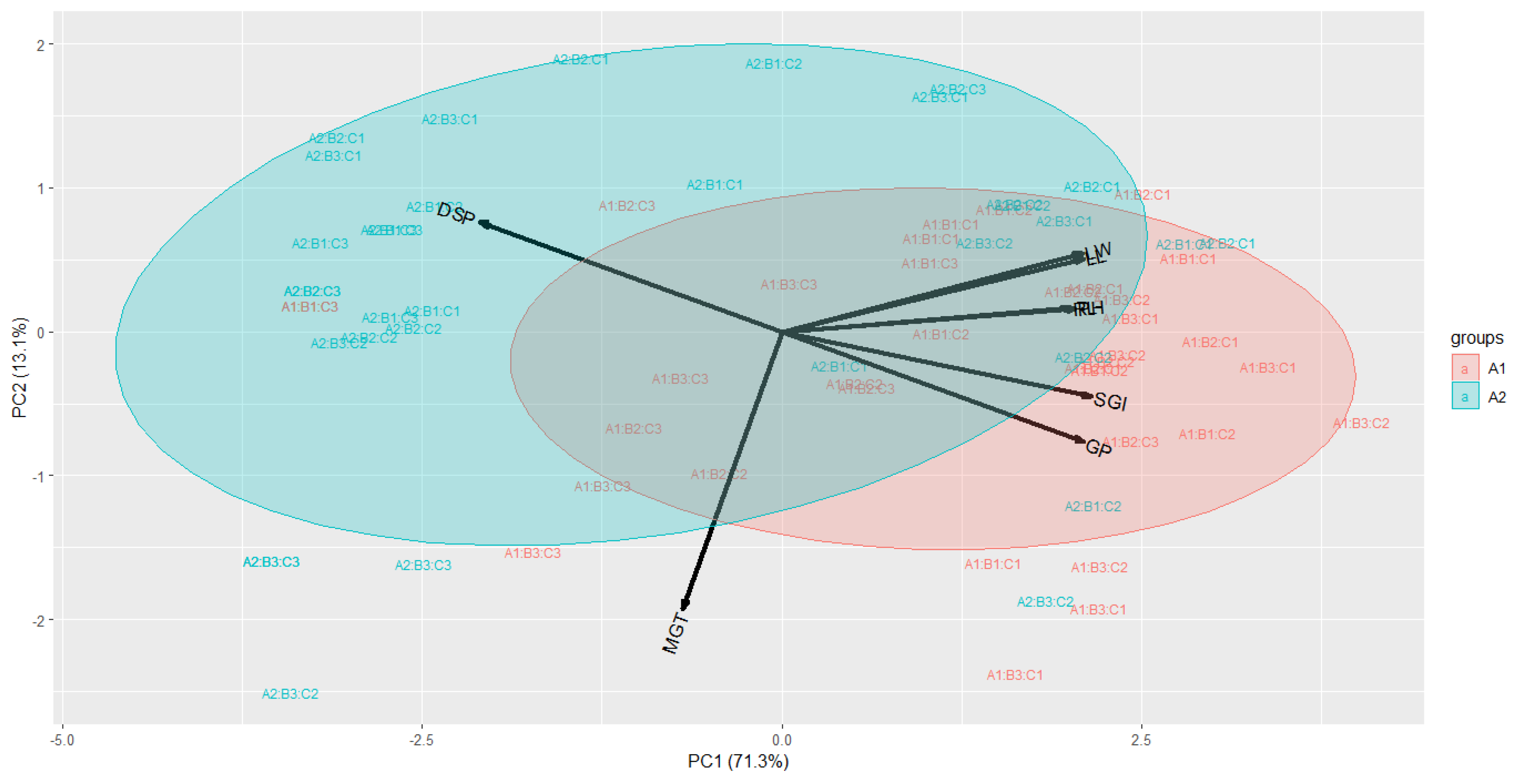

Figure 1). Principal component analysis, a multivariate method to examine the distribution patterns of the eight traits by reducing the number of variables, was used. The principal components (PCs) explained over 80% of the total variance, with two principal components covering 84.4% of the total variance. PC1 accounted for 71.3% of the variance, and PC2 for 13.1%. The analysis showed that seeds sown immediately after extraction (A1) were smaller compared to seeds left for seven days post-extraction (A2), with the A2 group closely associated with traits such as germination speed index, root length, plant height, leaf length, and leaf width (

Figure 2).

3. Discussion

A pre-sowing method called “seed priming” involves soaking seeds in an osmotic solution, which permits them to absorb water and undergo the initial stage of germination but prevents the radicle from emerging (protruding through the seed coat). The seeds can then be saved and then planted using standard methods after being soaked and dried to their initial moisture content. Priming alters the seeds' biochemical characteristics, including their enzyme activity, and encourages germination activities, like the mobilization of sugar [

13]. The duration of the germination process is significantly influenced by the temperature. There is a significant temperature scale that may be used to characterize the impact of temperature on germination: minimum, optimal, and maximum temperatures to begin. The maximum germination rate in the shortest amount of time is achieved at the optimal temperature. Every germination stage has a significant temperature, and because the process is so complex, the temperature response may change as the germination phases progress. The way that seeds react to temperature depends on a number of variables, including variety, seed quality, and harvest timing [

14].

The experimental germination percentage ranged from 2.00 to 87.00%, indicating low seed quality, possibly due to the mucilage present on the heart-shaped seeds after maturation. If the seeds are immediately sown, this mucilage can absorb moisture, leading to bacterial growth that inhibits germination. Seeds with mucilage are challenging to clean. The experiment also showed that using a 70°C temperature during germination resulted in a germination rate between 20.00 and 4.00%. High temperatures can damage seeds, reduce germination viability, and result in low germination percentages. Soaking seeds in water at an optimal temperature and then drying them to near-original moisture content before sowing can improve germination rates. For example, soaking rice seeds in water for 24 hours increased germination rate to 100% and enhanced root length and fresh stem weight, indicating improved physiological potential through increased germination and vigor. Corn seeds soaked in water for 18 hours and dried for 2 hours showed increased germination rate, root length, and vigor index, particularly for inbred lines. Soaking wheat seeds improves initial germination rates, sprout count, seed weight, and both biological and economic yield. Soaking wheat seeds for 16 hours resulted in high germination percentage, growth, yield, and economic profitability [

15].

The optimal soaking temperatures vary by seed type; for example, tomato, carrot, and onion seeds germinate better at 15°C for 14 days than at 25°C [

16]. Similarly, seed soaking affects seed germination and seedling growth in five flower species (Antirrhinum, Dahlia, Impatiens, Salvia, and Zinnia). Soaking these seeds at 20°C for 24 hours and then drying them enhanced the germination rate and the fresh and dry weights of the seedlings across all five species [

17]. Youngsapanan et al. [

18] found that chia seeds soaked in water at 20°C and 30°C for 12 hours had the highest germination rates (88.00 and 84.5%, respectively) with the fastest average germination times (3.64 and 3.85 days, respectively). Piwpan et al. [

19] reported that cucumber seeds soaked at 20°C for 24 hours had faster average germination times and root emergence compared to untreated seeds, retaining the highest germination percentage.

Recommendations from this experiment indicate that germination percentages ranged from 2.00 to 87.00%, reflecting generally low seed quality. This may be due to mucilage on Anthurium crystallinum seeds after ripening; if these seeds are immediately sown without thorough cleaning, the mucilage absorbs high moisture levels, fostering bacterial growth that inhibits germination. The experiments showed that at 70°C, the germination percentage was between 2.00 and 36.00%, suggesting that high temperatures during germination may damage the seeds, resulting in low germination percentages. The optimal water temperature for germination is recommended not to exceed 50°C, as temperatures above this limit lead to lower germination rates.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Details

The experiment utilized A. clarinervium seeds sourced from the Ratchaburi Udom Garden Training Center, located at 179 Moo 9, Don Klang Subdistrict, Damnoen Saduak District, Ratchaburi Province. Conducted in 2022, the study followed a factorial experiment in a completely randomized design (2x3x3) involving three factors: seed preparation (SP), plant growth stimulants (PGS), and water temperature (TW). For seed preparation, seeds were either sown immediately after extraction or left for seven days before sowing. The plant growth stimulants (commercially known as Phytonova and Germaplus) were applied in ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 1:2. The seeds were soaked in water at three different temperatures—27, 50, and 70°C. Each treatment was replicated four times with 25 seeds per replication, resulting in a total of 1,800 seeds. Seeds with over 85% ripeness were selected, sorted for uniform size, dehulled, and cleaned of any mucilage with clean water. The seeds were divided into two groups of 900 each: (1) those sown immediately, and (2) those left for seven days before sowing. Both groups were then subjected to different treatments. Seeds were soaked in the Phytonova+Germaplus solution in ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 1:2 and were also soaked in water at temperatures of 27, 50, and 70°C for five minutes each. The seeds were sown in 8-inch pots filled with a growing medium of peat moss mixed with brick dust at a 1:1 ratio and watered daily. They were cultivated under a 70% shaded greenhouse to monitor and record germination data 40 days after sowing.

4.2. Data Collection

1) Seed quality testing: This includes assessing germination percentage, seed mortality percentage, mean germination time (MGT), speed of germination index (SGI), and seedling growth rate. The key calculations are as follows:

- MGT is calculated based on the daily number of normal seedlings in a soil germination test, using the formula:

where, D = Day of counting

- Speed of germination index (SGI) measures seed vigor. Seeds with high vigor germinate faster than those with lower vigor. For calculating SGI, the number of normal seedlings is recorded daily for 40 days in the seed germination test, then calculated using the following formula:

2) Seedling Growth: Growth parameters include leaf length (average of all leaves), leaf width (average of all leaves), plant height (measured from the stem base to the leaf tip), and root length (measured from the stem base to the root tip).

4.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using ANOVA in a factorial experiment with a completely randomized design (2x3x3), involving three factors: seed preparation, plant growth stimulant, and water temperature. Mean comparisons were conducted with Duncan’s New Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at confidence levels of 95 and 99% (p<0.05 and p<0.01), and analyses were performed using SPSS software. Peason’s correlation coefficient was performed, and principal component analysis (PCA) was used for multivariate data, examining the relationships between variables by reducing the data to identify the distribution patterns of eight characteristics. These characteristics were extracted as principal components, which were expressed as linear functions of the original variables. The correlation coefficients and PCA were calculated and illustrated using R program (version 4.1.2) according to psych and ggbiplot packages [20-21], respectively.

5. Conclusions

The effects of different seed germination methods on the germination and growth of A. clarinervium seedlings were examined by testing various techniques and assessing seed quality and seedling growth. The study found that using the method of sowing seeds immediately after extraction, combined with Phytonova+Germa Plus (1:2) and soaking the seeds at 27°C, yielded the best seed quality and growth results for A. clarinervium. This method produced a germination rate of 87.00%, a dead seed percentage of 13.00%, an average germination time of 15.00 days, a germination speed index of 0.99, a leaf length of 3.68 cm, a leaf width of 3.44 cm, a shoot length of 9.81 cm, and a root length of 10.83 cm. Alternatively, using the same method but soaking the seeds at 50°C achieved a germination rate of 77.00%, a dead seed percentage of 23.00%, an average germination time of 21.20 days, a germination speed index of 0.93, a leaf length of 4.64 cm, a leaf width of 4.49 cm, a shoot height of 9.81 cm, and a root length of 13.79 cm. However, the method of sowing seeds after letting them sit for seven days, combined with Phytonova+Germa Plus at any concentration and soaking at 70°C, resulted in the poorest seed quality and seedling growth. This method produced a germination rate between 2.00 and 4.00%, a dead seed percentage of 96.00 to 98.00%, an average germination time of 25.00 to 39.00 days, a germination speed index of 0.05 to 0.14, a leaf length of 1.60 to 1.70 cm, a leaf width of 0.50 to 1.50 cm, a shoot height of 1.25 to 2.35 cm, and a root length of 1.25 to 4.27 cm. The use of high temperatures, specifically up to 70°C, in any method negatively impacted seed quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C., W.N., S.C., and C.K.; methodology, S.C. and A.D.; software, A.D. and T.K.; validation, S.C. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, S.C.; investigation, S.C., W.N., C.K., and T.K.; resources, A.D. and C.D.; data curation, S.C. and T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C. and T.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K.; visualization, C.D. and T.K.; supervision, W.N. and U.T.; project administration, S.C., W.N., and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to Faculty of Agriculture, Rajamangala University of Technology, Srivijaya and Udomgarden, Ratchaburi, Thailand for supporting research fund, equipment, and experimental place. This work was partially supported by Walailak University under the international research collaboration scheme [WU-CIA-04007/2024].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ramírez-Mosqueda, M.A.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.G.; Serrano-Romero, M.; Sosa-Ramírez, J.; Sandoval-Villa, M. Anthurium clarinervium Matuda: A promising ornamental plant with high potential for use in interiorscapes. Ornam. Plants. 2017, 7(3), 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Pre-sowing seed treatment - A shotgun approach to improve germination, plant growth, and crop yield under saline and non-saline conditions. Adv. Agron. 2005, 88, 223–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.; Pathan, A.K.; Gothkar, P.; Joshi, A.; Chivasa, W. On-farm seed priming: Using participatory methods to revive and refine a key technology. Agric. Syst. 2013, 112, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.A.; Koutroubas, S.D.; Fotiadis, S. Hydro-priming effects on seed germination and field performance of faba bean in spring sowing. Agriculture 2019, 9, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Apaolaza, L. Priming with silicon: A review of a promising tool to improve micronutrient deficiency symptoms. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 840770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbineau, F.; Taskiran-Özbingöl, N.; El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H. Improvement of seed quality by priming: Concept and biological basis. Seeds 2023, 2, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Jassal, R.; Kang, J.; Sandhu, S.; Kang, H.; Grewal, K. Seed priming techniques in field crops -A review. Agric. Rev. 2015, 36(4), 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetchakama, N. and Khaengkhan, P. Improvement of seed qualities with seed priming techniques. Prawarun Agric. J. 2018, 15(1), 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kaewsorn, P.; Saengsurasin, P.; Chulaka, P. Effects of temperature and duration during hydropriming on germination and vigor of buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) seeds. J. Agric. Res. Ext. 2020, 38(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Gray, D.; Dickson, G.M. The combined effects of osmotic priming with plant growth regulators and fungicide soaks on the seed quality of five bedding plant species. Seed Sci. Technol. 1991, 19, 495–503. [Google Scholar]

- Chumpookam, J.; Lin, H.L.; Shiesh, C.C. Effect of smoke-water derived from burnt dry rice straw (Oryza sativa) on seed germination and growth of papaya seedling (Carica papaya) cultivar ‘Tainung No. 2’. Hortic. Sci. 2012, 47(6), 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewsorn, P.; Chotanakoon, K.; Chulaka, P.; Chanprasert, W. Effect of seed priming on germination and seedling growth of pepper. Agric. Sci. J. 2017, 48(1), 70–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao, Y.; Asea, G.; Yoshino, M.; Kojima, N.; Hanada, H.; Miyamoto, K.; Yabuta, S.; Kamioka, R.; Sakagami, J. Development of Hydropriming Techniques for Sowing Seeds of Upland Rice in Uganda. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaeim, H.; Kende, Z.; Balla, I.; Gyuricza, C.; Eser, A.; Tarnawa, Á. The effect of temperature and water stresses on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sustainability 2022, 14, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Prasad, D.; Khan, F.A.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, B.; Astha. Seed priming: An overview of techniques, mechanisms, and applications. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11(1), 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, A.M.; Barlow, E.W.R.; Milthorpe, F.L.; Sinclair, P.J. Field emergence of tomato, carrot, and onion seeds primed in an aerated salt solution. Hortic. Sci. 1986, 111, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, O.; Sıtkı, E.; Ibrahim, D. Seed priming increases germination and seedling quality in antirrhinum, dahlia, impatiens, salvia and zinnia seeds. Ornam. Plants 2017, 7(3), 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Youngsapanan, Y.; Chulaka, P.; Kaewsorn, P. Effect of hydropriming on quality of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seeds. Thai Sci. Technol. J. 2021, 29(1), 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwpan, W.; Chulaka, P.; Kaewsorn, P. Effects of temperature and soaking duration of hydropriming on vigor of cucumber seed. Thai Sci. Technol. J. 2021, 29(4), 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. Package ‘psych’: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality Research. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/index.html (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Vu, V.Q.; Friendly, M.; Tavadyan, A. Package ‘ggbiplot’: A grammar of graphics implementation of biplots. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggbiplot/readme/README.html (accessed on 18 February 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).