1. Introduction

Pinus pinaster Aiton assumes a critical role in the north-central region of Portugal, covering 22.1% of the total forest area and projected to extend to 789,000 hectares by 2030, as reported by the 6th National Forest Inventory (IFN6) [

1]. However, the extent of this species has been adversely affected by recurrent forest fires, infestations, and sub-optimal management practices, thus undermining forest productivity and exacerbating environmental vulnerability [

2]. A significant challenge in managing these resources is the insufficient utilisation of biomass residues, which are often discarded or incinerated, leading to substantial CO₂ emissions and contributing to the deterioration of air quality [

2].

The sustainable reuse of this waste represents an opportunity to mitigate environmental impacts and promote a circular economy. Producing natural dyes from pine cone biomass offers a viable alternative for reducing dependence on highly polluting synthetic dyes, thereby decreasing CO₂-equivalent emissions [

3]. he textile industry contributes significantly to global emissions, with projections suggesting that textile consumption in the European Union has resulted in 121 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions [

4]. n addition, synthetic dyes are characterised by a considerable carbon footprint and pollute industrial effluents due to the presence of heavy metals and volatile organic compounds [

5].

Despite growing scientific interest, there are substantial gaps in the literature regarding the environmental and economic viability of this alternative. Most studies focus on the chemical properties of the extracts, but only a limited number quantify the reduction in emissions associated with replacing synthetic dyes with natural ones [

6,

7]. Consequently, this research aims to address this shortcoming by characterising and quantifying the environmental impacts associated with the valorisation of Pinus pinaster Aiton biomass, examining three components of the process: the pine cone residue, the extract used as a textile dye, and the residual pine cone material after extraction.

Using Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), this research compares the environmental impact and Global Warming Potential (GWP100) of natural dye extraction, elucidating the potential for reducing CO₂-equivalent emissions and the barriers to the sustainable integration of this biomass into industrial practices. The results derived from this study can inform forest management strategies and environmental policies, promoting more sustainable methodologies for utilising forest residues in Portugal.[

8].

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Bioeconomy and Circular Economy

The bioeconomy advocates a sustainable approach to the utilisation of biological resources, aiming to generate goods, services, and energy while facilitating the transition from dependence on fossil fuels to renewable alternatives [

9,

10]. This paradigm is in harmony with global sustainability initiatives, notably the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 11 focuses on sustainable cities and communities, whilst SDG 12 emphasises responsible consumption and production by reducing waste and optimising resource use [

9]. Through the integration of these principles, the bioeconomy encourages prudent resource management, enabling industries and communities to adopt environmentally sound practices.

The circular economy (CE) further reinforces these principles by maximising material efficiency through reuse, recycling, and closed-loop systems. CE frameworks support the transformation of waste into valuable products, thereby minimising environmental degradation and conserving natural resources [

10]. In this context, agroforestry waste from Pinus pinaster Aiton, a renewable and abundant resource, remains underutilised, despite its potential for conversion into natural dyes that could support sustainable industrial transitions.

2.2. Sustainable Forest Management and Waste Utilization

Sustainable forest management (SFM) is essential for preserving forest ecological integrity while providing economic and social benefits for future generations [

11,

12]. In north-central Portugal, pine cone by-products are often discarded or burnt, even though they have significant potential as sources of bioenergy and precursors for natural dyes [

3]. Unregulated combustion exacerbates CO₂ emissions, poses risks to public health, and undermines the resilience of forest ecosystems [

13,

14].

Efficient biomass reclamation can mitigate environmental risks, such as forest fires, by integrating agroforestry residues into value-added applications, including the production of textile dyes, energy recovery, and soil enhancement. This research builds on prior studies by demonstrating how valorizing Pinus pinaster Aiton waste addresses critical gaps in forest management and industrial sustainability.

2.3. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Emissions Inventory

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating environmental impacts across a product’s entire lifecycle [

15,

16]. LCA enables industries to optimise production processes, reduce environmental footprints and adopt more sustainable alternatives. This study applies LCA to assess the natural dye extraction process and its respective contributions to CO₂ equivalent emissions. The emissions inventory, based on the IPCC's Global Warming Potential (GWP) factors, systematically quantifies the mitigation potential of recovering pine cone waste into natural textile dyes instead of using synthetic textile dyes [

17].

2.4. Natural Dyes versus Synthetic Dyes

Synthetic dye production relies on energy-intensive processes, resulting in significant effluent contamination and greenhouse gas emissions [

4]. The textile industry accounts for 8–10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, making it one of the most environmentally impactful sectors [

18]. Additionally, synthetic dyes emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that compromise air quality and public health (L. [

18]. In 2020, textile manufacturing in the European Union was responsible for 121 million tonnes of CO₂-equivalent emissions, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable alternatives [

19].

Extracting natural dyes from pine cone waste presents a biodegradable, low-impact alternative consistent with circular economy principles, aiming to reduce industrial toxicity and carbon footprints [

20]. Optimizing solvent selection, extraction parameters, and energy use can further enhance yield and sustainability.

2.5. Pine Cone Chemical Composition and Dye Potential

Pine cones, composed of bark and seeds, are rich in organic carbon, phenolic compounds, and tannins [

21]. Their use as natural dyes aligns with Portugal’s bioeconomic objectives, facilitating greenhouse gas reduction through waste repurposing [

3]. Alkaline NaOH extraction produces reddish and yellowish hues, though further advancements are needed to improve chromatic stability and photodegradation resistance [

22]. This study advances current knowledge by quantifying avoided emissions, evaluating LCA methodologies, and assessing the industrial feasibility of incorporating pine cone-derived dyes into textile manufacturing, thereby reinforcing the role of agroforestry by-products in decarbonization and circular economy strategies.

2.6. Carbon Economy, Emissions Reduction Potential, and Public Policies for Carbon Neutrality Targets

The carbon economy involves quantifying, reducing, and offsetting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, aiming for carbon neutrality [

23]. This approach requires industries and governments to set reduction targets, replace fossil fuels with renewables, and implement effective offsetting strategies [

17]. International frameworks, such as the UN Global Compact and Net Zero Coalition, accelerate this transition.

Converting pine cone waste into natural dyes is a viable method for reducing the ecological impact of synthetic dye production. Applying IPCC impact factors enables accurate quantification of CO₂-equivalent reductions [

24]. By valorizing forest waste instead of incinerating it, this strategy reduces direct GHG emissions and replaces carbon-intensive synthetic dyes, highlighting the importance of biomass utilization in climate change mitigation [

25].

Public policies aimed at mitigating GHG emissions are crucial for sustainable biomass utilization [

26]. In Portugal, strategies promoting the bioeconomy and agroforestry residue valorization are key components of emission reduction frameworks [

27]. Improper management of pine cone wastevia landfilling or uncontrolled combustion substantially increases GHG emissions, as methane from decomposition is 28 times more impactful than CO₂, and combustion releases CO₂ instantly [

28].

Legislation such as Decree-Law No. 102-D/2020 emphasizes waste recovery and integration into reuse markets [

29]. Portugal’s Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRR) provides incentives for replacing synthetic materials with bio-based alternatives, including forest biomass-derived dyes [

30]. Integrating pine cone recovery within circular economy frameworks enhances decarbonization initiatives and ensures compliance with European climate policies.

2.7. CO₂ Emissions in Portugal and Climate Change in Portugal

In 2022, Portugal saw a 5.4% decrease in agricultural GHG emissions compared to 1990, with agriculture comprising about 12% of national emissions [

31]. Despite progress, the land use and forestry sector (LULUCF) has fluctuated between being a carbon sink and a source, mainly due to forest fires, droughts, and climate change [

32]. Severe wildfires in 2003, 2005, and 2017 temporarily impaired forests carbon sequestration capacity, in 2017 alone, wildfires emitted an estimated 4.5 million metric tons of CO₂ about 15% of Portugal’s annual emissions [

31]. These events highlight the urgent need for improved waste recovery, sustainable land management, and policies to enhance forest resilience against climate disruptions.

Portugal’s climate trajectory shows a marked temperature increase of 0.45ºC per decade double the global average with annual temperatures above average since 2008, especially in spring [

31]. Including LULUCF, total emissions reached 50.5 million tons, a 23.6% decline since 1990, with energy production still the main contributor. The 2050 Carbon Neutrality Roadmap sets ambitious targets: a 45–55% GHG reduction by 2030, 65–75% by 2040, and 85–90% by 2050 [

26]. This underscores the need for sustainable forest waste recovery to achieve national decarbonization goals.

2.8. Research Gap

Despite progress in LCA, significant gaps remain in accurately quantifying CO₂-equivalent emissions and comparing valorization methods [

33,

34]. The production of natural dyes from biomass faces challenges in extraction efficiency, dye stability, and environmental impact assessment. Optimization strategies such as ultrasound-assisted extraction, careful solvent selection, and microencapsulation—are essential for improving pigment durability and efficacy [

35,

36]. While replacing synthetic dyes with biomass alternatives can reduce emissions, further research is needed to refine evaluation methods and quantify long-term environmental benefits [

37]. This study systematically addresses these gaps, offering concrete emission reduction metrics and highlighting the importance of valorizing forest residues for decarbonization.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparing the Material

This study used waste pine cones from Pinus pinaster Aiton, harvested in December 2024 in Viseu, Portugal. The cones were dried at 65°C, ground with a cutting mill (RETSCH SM 300), and sieved using a shaker (RETSCH S200). Particles sized 500 µm to 2 mm were selected for testing. Analyses were conducted at the Polytechnic Institute of Viseu (IPV), School of Technology and Management (ESTGV). All procedures were performed in triplicate.

3.2. Dye Extraction

The textile industry often uses sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solutions to extract dyes from plants. NaOH disrupts plant cell walls and solubilizes compounds, making it effective depending on the dye type and plant properties [

10] that have an acidic or slightly polar character [

11], such as flavonoids, anthocyanins and chlorophylls. The extraction were carried out, each with a concentration of NaOH, 1% percentages relative to the mass of dried pine cone waste. First, 40g of crushed and dried pine cone was placed in a container with approximately 350 mL of water, along with NaOH. This mixture was then placed in a thermostatic bath at 70ºC (WTCbinder/Germany) for 1 hour using ultrasound. After cooling, they were kept at 4 ºC to avoid contamination or deterioration.

3.3. Determination of the Fixed Carbon Content in the Original, Extracted Pine Cone and Its Extract

Fixed carbon was determined according to the ASTM D3172-1 method (Reapproved 2021). This method provides an indirect estimate of the fraction of structural carbon remaining in the biomass. Fixed carbon was calculated according to equation 1:

3.4. Determination of CO2 eq in the Original, Extracted Pine Cone and Its Extract

The estimation of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO₂-eq) emissions from fixed carbon in biomass was based on the recognized stoichiometric calculation, as established by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The CO

2 eq in the original, extracted and extracted pine cones was calculated according to equation 2, where,

msample total mass of wet residue (g),

U moisture fraction and 44/12 carbon to CO₂ conversion factor (3.67):

3.5. Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA)

The study adheres to ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 standards for Life Cycle Analysis (LCA). It uses an attribution method to link environmental impacts directly to converting pine cone waste into natural textile dyes. Data collection involved measuring electricity consumption and NaOH used to extract dye from 40 g of pine cones, achieving a 7.8% yield. Secondary data was sourced from databases like Ecoinvent and relevant literature, including gas emissions from synthetic dye production, converted into CO₂ equivalents by the IPCC. Modelling in SimaPro will combine experimental and secondary data to ensure robust, comparable results, assessing scenarios for 1 kg of pine cones.

Table 1.

Inventory of the Pine Cone Valorisation Process for Natural Textile Dye Production. Here is your table translated into English:

Table 1.

Inventory of the Pine Cone Valorisation Process for Natural Textile Dye Production. Here is your table translated into English:

| Category |

Inputs |

Outputs |

| Raw Material |

Pine cone (kg) – 1 kg |

Solid residues from processing (~6.98 kg) |

| Distilled Water |

8.74 kg (Produced by reverse osmosis) |

Treated wastewater |

| Chemical Products |

NaOH (g) – 10 g |

Liquid effluents with dissolved compounds |

| Electric Energy |

Distilled water production (14.15 kWh) |

CO₂, NOₓ, CO, PM₂.₅ emissions |

| Thermostatic Bath |

Energy consumption for ultrasound (2 kWh) |

CO₂, NOₓ, CO, PM₂.₅ emissions |

| Atmospheric Emissions |

CO₂, NOₓ, CO, PM₂.₅ |

Pollutant gases released during extraction |

| By-products |

Natural dye – 87.5 g |

Possible reuse of organic residues |

Functional Unit and System Boundaries

The functional unit used in all the scenarios evaluated in this study is 1 kg of pine cone waste from pine cone exploitation activities, from the Punus pinaster Aiton.

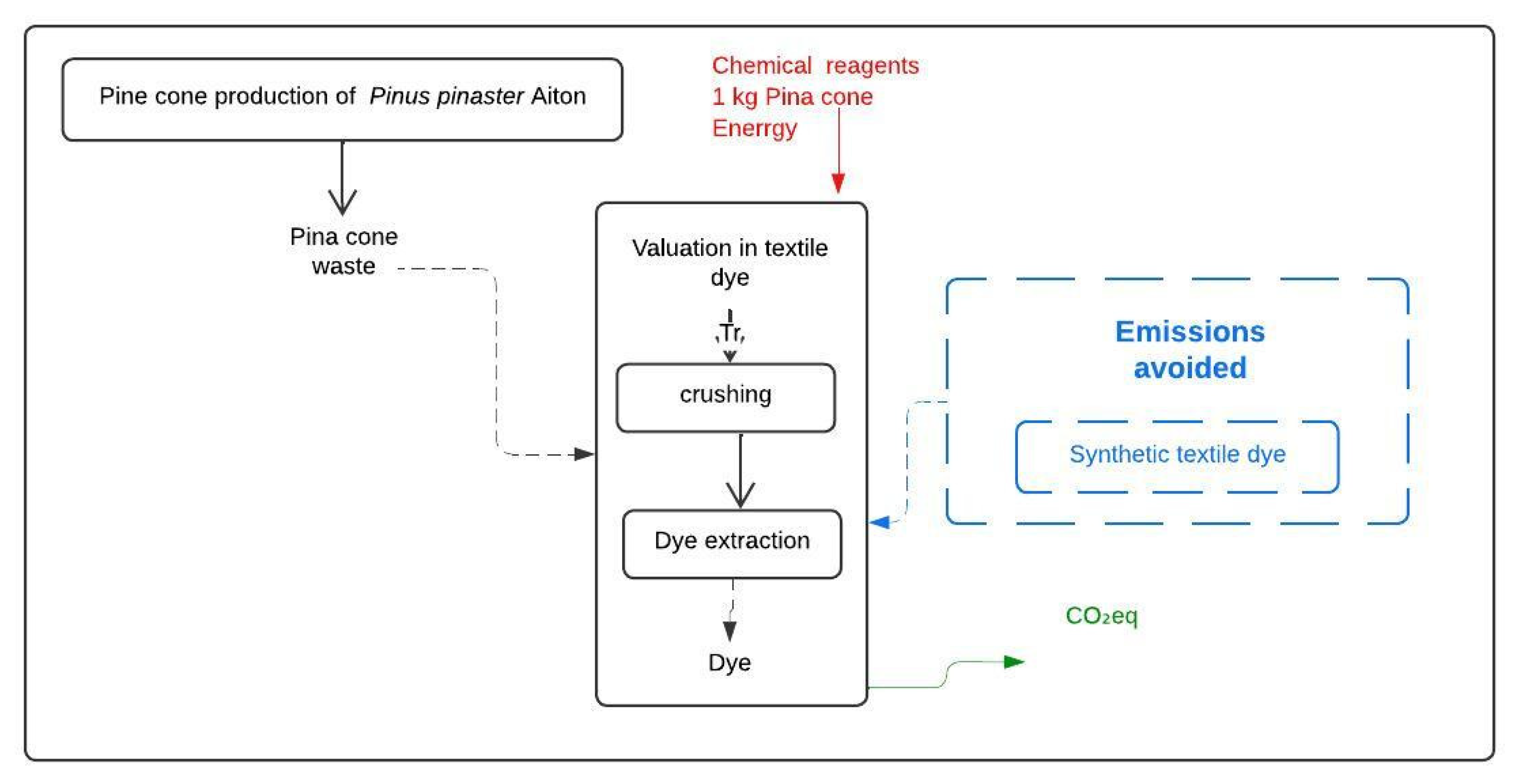

In the valorisation scenarios, a novel product is generated that embodies an alternative function of the system (

Figure 1). To address the multifunctionality of the system, the environmental burdens mitigated by substituting conventional raw materials are duly considered. In this manner, a 'credit' is conferred for diminishing the necessity for materials derived from traditional raw materials.

The framework for assessing environmental impact incorporates the conversion of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions into equivalent carbon dioxide (CO₂ eq), compliant with global standards. Direct CO₂ emissions, already quantified in kg CO₂ eq, are aggregated with those of methane (CH₄), which is transformed using an equivalence factor of 28 to accurately represent its enhanced global warming potential over a century-long timeframe. For additional gases, such as carbon monoxide (CO) and nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), specific factors referenced in the literature are employed, or their environmental ramifications are examined independently, including their capacity for tropospheric ozone formation and the acidification of ecosystems.

Utilizing the emissions inventory produced, the scenarios for the recovery of pine cone waste will be quantitatively compared, emphasizing the tonnes of CO₂ eq either avoided or generated during each process. This methodology facilitates the quantification of the climate mitigation potential associated with the extraction of natural textile dyes in contrast to conventional practices (such as incineration or landfill), thereby underscoring its role in diminishing the carbon footprint of the textile sector. Concurrently, non-climate-related impacts—such as the eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems or human toxicity—will be qualitatively assessed to provide a comprehensive analysis, ensuring that the sustainability of the process transcends the climate dimension alone.

3.6. Emissions Avoided (Synthetic Dye)

Comparison of CO₂ emissions from natural dyes with those from synthetic dyes was calculated according to equation 3, where E

synthetic dye synthetic dye emissions (kg CO

2) e E

valorization Emissions from natural dyes (kg CO₂).

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Analysing the Composition of Unsorted Waste

Analysing the fixed carbon of Pinus pinaster Aiton pine cone waste, extract and residual pine cone from the dye extraction process is extremely important prior to implementing a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), as it facilitates a comprehensive understanding of the ecological ramifications and practicality of material recovery.

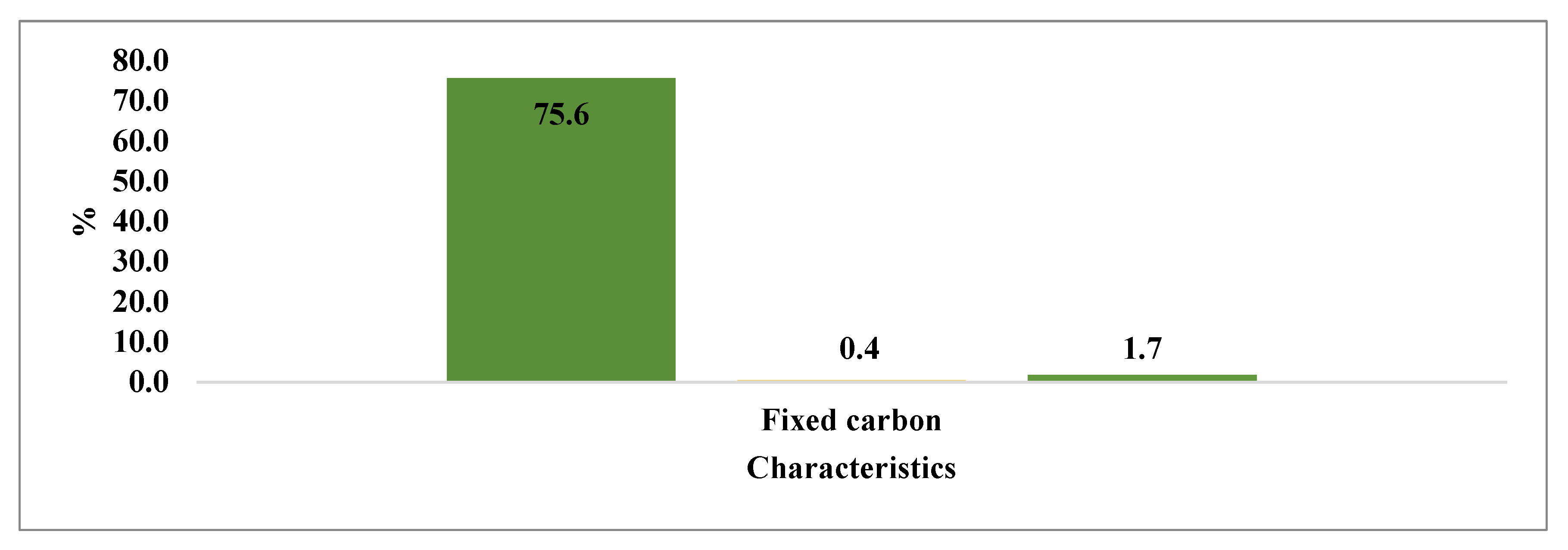

The fixed carbon content of 75.6% observed in the waste derived from

Pinus pinaster Aiton pine cones can be juxtaposed with findings from various studies that have scrutinized this specific biomass

Figure 2. In the northern region of Portugal, the fixed carbon concentration in the wood and bark of

Pinus pinaster exhibits variability ranging from 70% to 80%, contingent upon the age of the trees and the conditions under which they are cultivated [

13]. Research suggests that both stand management and the age of the trees significantly affect fixed carbon levels, with older specimens demonstrating concentrations exceeding 72% attributed to enhanced lignification processes [

41]. Furthermore, an additional investigation has estimated that the mean carbon content within the biomass of

Pinus pinaster Aiton is approximately 45.7%. Nevertheless, in the case of woody residues, including bark and pine cones, the carbon content values can attain levels between 75% and 78%, which aligns with the findings of this current study [

42].

The waste extract from

Pinus pinaster Aiton pine cones possesses a fixed carbon content of 0.4%, which is relatively modest when compared to other botanical extracts utilized in the synthesis of natural textile dyes (

Figure 2). Dyes derived from onion and pomegranate peels exhibit fixed carbon levels exceeding 1%, attributable to the lignocellulosic compounds that impact the thermal stability of the pigments [

43]. Conversely, turmeric dyes display fluctuations in fixed carbon content ranging from 0.5% to 1%, depending on the extraction technique applied [

44]. The presence of fixed carbon can influence the interactions between dyes and mordants, which are essential for ensuring color fastness. The implementation of effective mordanting practices can engender more robust chemical bonds, thereby enhancing the dye's stability within the fabric [

45].

The fixed carbon content (1.7%) (

Figure 2) is indicative of the material's thermal stability, which is advantageous in processes such as the production of activated carbon or biochar [

46]. The recovery of this waste can adopt various methodologies, including its use in the production of bioenergy through pyrolysis or gasification, thus reducing dependence on fossil fuels [

47,

48]. Another route involves their application as a substrate in the synthesis of biopolymers or as adsorbent materials that interact with dyes and industrial effluents [

49]. Improper disposal in unregulated dumps can emit greenhouse gases such as methane and carbon dioxide, thus exacerbating climate change [

50]. Effective management of this material must therefore prioritise reuse, thereby minimising pollution and promoting environmental and industrial benefits [

51].

4.2. Comparative Analysis of the Carbon and CO2eq of the Pine Cone Residue, the Pine Cone Extract and the Extracted Pine Cone

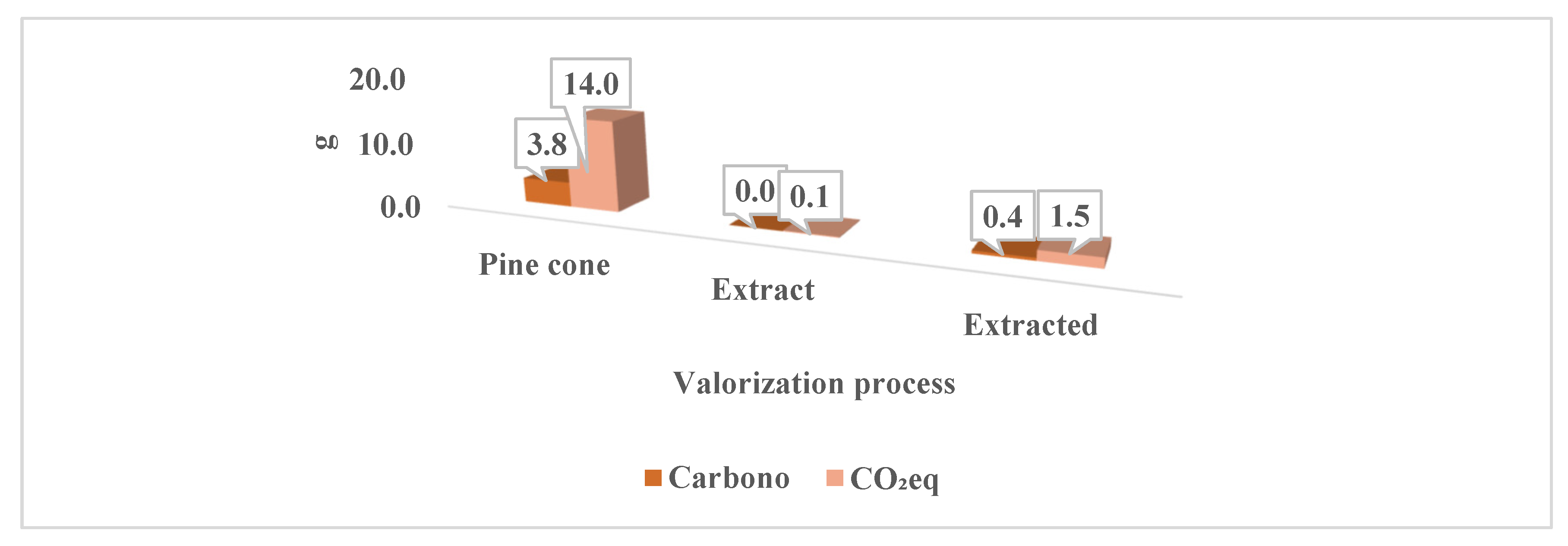

The examination of carbon quantities and the release of CO₂ equivalent (CO₂ eq.) during the process of converting Pinus pinaster Aiton pine cone waste into natural textile dyes is essential for comprehending its ecological ramifications and for facilitating comparisons with alternative valorisation methods and synthetic dye production.

The data indicates that the initial pine cone possesses a carbon content of (3.8 g), which corresponds to (14.0 g of CO₂eq), thereby suggesting that, prior to extraction, the material harbors a considerable quantity of fixed carbon, which could potentially affect its carbon footprint when subjected to combustion or decomposition processes (

Figure 3). Following the extraction of the dye, the resultant extract contains (0.0 g) of carbon, equivalent to (0.1 g of CO₂eq), implying that the liquid fraction obtained does not significantly contribute to carbon emissions and is characterized by a minimal environmental impact (

Figure 3). Conversely, the extracted pine cone, defined as the solid residue that remains post-extraction, contains (0.4 g) of carbon, which equates to (1.5 g of CO₂eq), thereby signifying that a fraction of carbon persists, albeit with a notable decrease relative to the original pine cone (

Figure 3).

In valorisation processes, research suggests that the synthesis of synthetic dyes can yield substantial CO₂ emissions, attributable to the employment of petrochemical solvents and reactions that involve volatile organic compounds [

52]. Furthermore, traditional industrial methodologies frequently exhibit elevated carbon footprints as they entail chemical synthesis stages that necessitate high temperatures and substantial energy consumption, thereby markedly amplifying greenhouse gas emissions [

53].

The significance of this data in quantifying CO₂ equivalents is rooted in its potential to evaluate the sustainability of the valorization process. The extraction of natural textile dyes from the waste of Pinus pinaster Aiton pine cones demonstrates a diminished environmental impact, particularly during the liquid phase of the extract, which contributes insignificantly to carbon emissions. Also, the solid remnants derived can be transformed for usage in biofuel generation, activated carbon development, or composting, hence preventing its disposal and further cutting down the carbon footprint associated with the method.

4.3. LCA

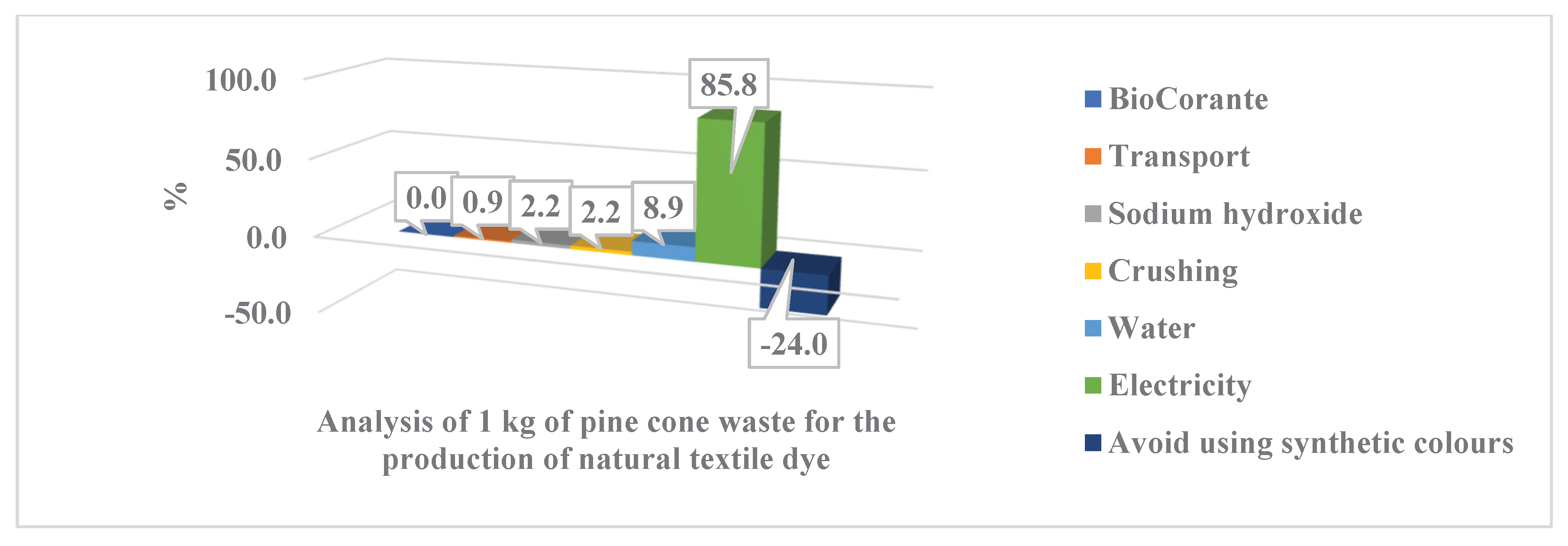

Analyzing the ecological ramifications associated with the production of natural dyes derived from the waste of Pinus pinaster Aiton pine cones underscores the imperative for sustainable methodologies that exert minimal ecological repercussions.

The statistical evidence points out that 85.8% of emissions in CO₂ equivalents stem from electricity use, with an additional 8.9% stemming from the water employed in the production process (

Figure 4). The contributions from transportation, crushing, and sodium hydroxide usage are comparatively negligible.

The investigation indicates a compensatory effect of -24% on the carbon footprint when substituting synthetic colorants with natural alternatives, thereby implying that the adoption of natural dyes may diminish the dependence on petrochemical resources and alleviate the environmental consequences associated with the textile sector (

Figure 4).

To effectively mitigate emissions, it is essential to enhance energy efficiency during production and to incorporate renewable energy sources such as solar power or residual biomass. Additionally, implementing efficient water management practices, encompassing reuse and reduction during the production phase, can further diminish the ecological impact.

The transition from synthetic dyes to natural alternatives serves to significantly reduce environmental toxicity and fosters the principles of a circular economy through the repurposing of plant waste. The valorization of pine cones for dye extraction presents a sustainable paradigm, contributing to the reduction of the textile industry's carbon footprint while simultaneously promoting the health of ecosystems.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights the potential of Pinus pinaster biomass as a sustainable alternative to synthetic dyes, contributing to global decarbonisation efforts and promoting sustainability initiatives in the textile sector. The results highlight the favourable physicochemical properties of pine cone waste for energy recovery and chemical applications, with a fixed carbon content of 75.6%, indicating its suitability for biochar production, carbon sequestration and thermal energy conversion.

With regard to dye extraction, the pine cone extract has a low fixed carbon content (0.4%), while the residual biomass maintains a moderate content (1.7%), making it viable for biochar synthesis and adsorption applications. Life cycle analysis (LCA) reveals that the production of natural dyes reinforces the environmental advantages associated with replacing synthetic dyes. The results indicate that (85.8%) of emissions are attributed to electricity consumption, while water use accounts for (8.9%), highlighting the need to optimise energy efficiency in extraction processes.

The data indicates that the initial pine cone has a carbon content of (3.8 g), equivalent to (14.0 g of CO₂eq), suggesting that, before extraction, the material contains a considerable amount of fixed carbon, which can influence its carbon footprint when subjected to combustion or decomposition processes. After extraction of the colourant, the resulting extract contains (0.0 g) of carbon, equivalent to (0.1 g of CO₂eq), indicating that the liquid fraction obtained does not contribute significantly to carbon emissions and has minimal environmental impact. On the other hand, the extracted pine cone, defined as the solid residue remaining after extraction, contains (0.4 g )of carbon, equivalent to (1.5 g of CO₂eq), demonstrating that a fraction of carbon persists, albeit with a significant reduction compared to the original pine cone.

As well as mitigating environmental impacts, the adoption of natural colourants makes it possible to valorise forestry waste, promoting its reuse in production. However, challenges related to process scalability, economic viability and industrial implementation require further investigation.

Future research should prioritise advances in energy efficiency, the development of innovative solvents and the optimisation of extraction methodologies to increase the yield and stability of natural dyes. The application of these strategies could consolidate the valorisation of biomass as a sustainable paradigm, accelerating the transition to environmentally responsible industrial practices in the textile sector and in the management of forest resources in Portugal.

Acknowledgments

This work was developed under the Science4Policy 2023 (S4P-23): annual science for policy project call, an initiative by PlanAPP – Competence Centre for Planning, Policy and Foresight in Public Administration in partnership with the Foundation for Science and Technology, financed by Portugal ́s Recovery and Resilience Plan."

References

- Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas (ICNF). 6.o Inventário Florestal Nacional (IFN6) - Relatório Final. Available online: https://www.icnf.pt/api/file/doc/0f0165f9df0d0bbe (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Avillez, F.; et al. Linhas estratégicas dos sectores de produção primária no contexto do desenvolvimento da estratégia nacional para a bioeconomia sustentável 2030: Relatório principal.

- Barreto, A.; Martins, J.M.; Ferreira, N.; Brás, I.; Carvalho, L.H. Valorisation of forest waste into natural textile dyes—Case study of pine cones. Forests 2025, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O impacto da produção e dos resíduos têxteis no ambiente (infografias). Temas | Parlamento Europeu. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pt/article/20201208STO93327/o-impacto-da-producao-e-dos-residuos-texteis-no-ambiente (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Manzoor, J.; Sharma, M. Impact of textile dyes on human health and environment. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/gateway/chapter/www.igi-global.com/gateway/chapter/240902 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Arias, A.; Costa, C.E.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T.; Domingues, L. Process modeling, environmental and economic sustainability of the valorization of whey and eucalyptus residues for resveratrol biosynthesis. Waste Management 2023, 172, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, D.G.; Tripathi, D.S.; Barot, D.P.; Modhia, D.C.Y. Zero waste manufacturing: A case study of circular and sustainable economy practices. Journal of Informatics Education and Research 2025, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Miceikienė, A. Contribution of the European Bioeconomy Strategy to the Green Deal Policy: Challenges and opportunities in implementing these policies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Towards zero waste: A catalyst for delivering the Sustainable Development Goals. 2023. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/xmlui/handle/20.500.11822/44102 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Wattanakit, C.; Fan, X.; Mukti, R.R.; Yip, A.C.K. Green chemistry, catalysis, and waste valorization for a circular economy. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, 9, e202400389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J.R.; Tappeiner, J.C.; Waring, R.H.; Tattersall Smith, C. Sustainable forestry: Ecology and silviculture for resilient forests. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; et al. Sustainable forest management (SFM) for C footprint and climate change mitigation. In Agroforestry to Combat Global Challenges: Current Prospects and Future Challenges; Jatav, H.S., Rajput, V.D., Minkina, T., Van Hullebusch, E.D., Dutta, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasugunasekar, D.; Patel, A.K.; Devi, K.B.; Singh, A.; Selvam, P.; Chandra, A. An integrative review for the role of forests in combating climate change and promoting sustainable development. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 2023, 13, 11, 4331–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, B.; Yakoob, M.; Shah, M.P. Agricultural waste management strategies for environmental sustainability. Environmental Research 2022, 206, 112285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.A. Life cycle assessment. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2016; pp. 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Jolliet, O.; Saade-Sbeih, M.; Shaked, S.; Jolliet, A.; Crettaz, P. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment. CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Mussinelli, E.; Tartaglia, A.; Castaldo, G.; Riva, R.; Cerati, D.; Sereni, A. The mitigation potential of environmental compensations: A challenge for the carbon neutrality transition. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1402, 1, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraetzig, E.R.S.; Ávila, L.V.; Beuron, T.A.; Garlet, V. Mudanças climáticas e setor têxtil: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Revista GESTO: Revista de Gestão Estratégica de Organizações 2024, 12, 1, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Azoia, N.; Silva, C.; Marques, E. Textile industry in a changing world: Challenges of sustainable development. U.Porto Journal of Engineering 2020, 6, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.A.; El-Gamal, A.R.; Gouda, M.; Mahrous, F. A new approach for natural dyeing and functional finishing of cotton cellulose. Carbohydrate Polymers 2010, 82, 4, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolasco, A.; et al. Exploring the untapped potential of pine nut skin by-products: A holistic characterization and recycling approach. Foods 2024, 13, 7, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordenunsi, B.R.; Oliveira do Nascimento, J.R.; Genovese, M.I.; Lajolo, F.M. Influence of cultivar on quality parameters and chemical composition of strawberry fruits grown in Brazil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 9, 2581–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacentini, R.D.; Garro, S. Carbon neutral industries and compensation for greenhouse gas emissions. Drying Technology 2022, 40, 16, 3371–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; et al. Forest for sustainable development. In Land and Environmental Management through Forestry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2023; pp. 293–311. [CrossRef]

- Biswal, T.; Priyadarsini, M. Dyeing processing technology: Waste effluent generated from dyeing and textile industries and its impact on sustainable environment. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/gateway/chapter/www.igi-global.com/gateway/chapter/240900 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente (APA). Roteiro para a Neutralidade Carbónica 2050. Available online: https://apambiente.pt/clima/roteiro-para-neutralidade-carbonica-2050 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente (APA). Bioeconomia. Available online: https://apambiente.pt/apa/bioeconomia (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Parlamento Europeu. Emissões de gases com efeito de estufa por país e setor (Infografia). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/pt/article/20180301STO98928/emissoes-de-gases-com-efeito-de-estufa-por-pais-e-setor-infografia (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Diário da República. Decreto-Lei n.o 102-D/2020. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/102-d-2020-150908012 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Plano de Recuperação e Resiliência - Recuperar Portugal (PRR). Available online: https://recuperarportugal.gov.pt/prr/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente (APA). Inventário Nacional de Emissões 2024. Available online: https://apambiente.pt/sites/default/files/_Clima/Inventarios/20240408/20240327%20memo_emiss%C3%B5es_2024.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Lourenço, L. Incêndios florestais de 2003 e 2005. Tão perto no tempo e já tão longe na memória!

- Rodrigues, R.M.; Branco, A.; Sardinha, I.D.; Oliveira, C.; Faustino, S. Estudo de contextualização e operacionalização de pequenas centrais de valorização de biomassa florestal em Portugal. Available online: https://www.icnf.pt/api/file/doc/011d74e5ed3846bc (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Branca, A.; et al. Estudo de contextualização e operacionalização de pequenas centrais de valorização de biomassa (CVB) em Portugal. Available online: https://www.agif.pt/app/uploads/2024/09/20231012-SinteseDosRelatorios.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Gomes, J.; Serrano, C.; Oliveira, C.; Moldao-Martins, M. Impacto do microencapsulamento na estabilidade do corante natural obtido a partir dos subprodutos do morango e do mirtilo. Available online: https://repositorio.ulisboa.pt/handle/10400.5/16282 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ferreira, J.H.M.; de Sousa, A.C.; Magalhães, V.L.S.; Rodrigues, R.L.D.; Queiroz, S.R.S.; Coutinho, R.M.P. Corantes naturais: Extração e utilização no tingimento de substratos orgânicos como alternativa sustentável. 2024.

- Integrating circular economy, SBTI, digital LCA, and ESG benchmarks for sustainable textile dyeing: A critical review of industrial textile practices. Global NEST Journal 2023, June. [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, I.I.; Hassan, N.D.; Mamat, S.N.H.; Nawi, N.M.; Rashid, W.A.; Tan, N.A. Extraction technologies and solvents of phytocompounds from plant materials: Physicochemical characterization and identification of ingredients and bioactive compounds from plant extract using various instrumentations. In Ingredients Extraction by Physicochemical Methods in Food; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 523–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Phenolics and polyphenolics in foods, beverages and spices: Antioxidant activity and health effects – A review. Journal of Functional Foods 2015, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.F.C. Equações de biomassa para Pinus pinaster e Quercus pyrenaica na Região Norte de Portugal, 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10348/5470 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Nunes, L.; Patrício, M.; Tomé, J.; Tomé, M. Carbon and nutrients stocks in even-aged maritime pine stands from Portugal. Forest Systems 2010, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, L.S. Pinhais bravos: Ecologia e gestão. Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa. 2004. Available online: https://repositorio.ulisboa.pt/bitstream/10400.5/14258/1/Pinhais%20bravos-sbPbEcoges.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ferreira, J.H.M.; de Sousa, A.C.; Magalhães, V.L.S.; Rodrigues, R.L.D.; Queiroz, S.R.S.; Coutinho, R.M.P. Corantes naturais: Extração e utilização no tingimento de substratos orgânicos como alternativa sustentável. 2024.

- Galeti Narimatsu, B.M.; do Bem, N.A.; Wachholz, L.A.; Linke, P.P.; Perez Lizama, M. de los A.; Soto Herek Rezende, L.C. Corantes naturais como alternativa sustentável na indústria têxtil. Revista Valore 2021, 5, e–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; et al. Understanding the fastness issues of natural dyes. In Dye Chemistry - Exploring Colour from Nature to Lab; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacinto, R.C.; Brand, M.A.; Rios, P.D.; Cunha, A.B.D.; Allegretti, G. Análise da qualidade energética da falha de pinhão para a produção de briquetes. Scientia Forestalis 2016, 44, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.; Oliveira, C.E.L.; Reflexões acerca do aproveitamento energético de resíduos de biomassa por pirólise e gaseificação. Ensaio Energético 2022. Available online: https://ensaioenergetico.com.br/reflexoes-acerca-do-aproveitamento-energetico-de-residuos-de-biomassa-por-pirolise-e-gaseificacao/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Rykała, W.; Fabiańska, M.J.; Dąbrowska, D. The influence of a fire at an illegal landfill in southern Poland on the formation of toxic compounds and their impact on the natural environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 20, 13613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, A.S.; Suresh, S.; Umesh, M.; Stanly, L.M.; Grigary, S.; James, N. Biodegradable organic polymers for environmental protection and remediation. In Organic Polymers in Energy-Environmental Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2024; pp. 381–402. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.; Mishra, P.; Singh, N.; Pathak, A.K. Landfill emissions and their impact on the environment. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology 2020, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangam, I.S.S.; Reddy, K.B.; Prakash, P.H.; Reddy, P.H. A holistic approach to handling metallic waste for environmental sustainability. In 2024 3rd International Conference for Advancement in Technology (ICONAT), 2024; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Trotta, P.A. Corantes têxteis: Impacto e sustentabilidade uma revisão bibliográfica. 2025. Available online: https://app.uff.br/riuff/handle/1/37068 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Júnior, W.A.G.P.; de Azevedo, F.R.P. Corantes sintéticos e seus impactos ambientais: Desafios, legislação e inovações tecnológicas sustentáveis. Revista Ibero-Americana de Humanidades, Ciências e Educação 2024, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).