Background

Global climate change has been shown to have an array of effects on the land as well marine animals (Deutsch et al. 2008, Häder and Barnes 2019, Sage 2020, da Silva et al. 2023). Amphibians are especially vulnerable to climate change scenarios for they are dependent on optimal temperatures and water availability at various life history stages (Lertzman-Lepofsky et al. 2020). The situation might prove more detrimental to anuran amphibians as they vocally communicate which requires high metabolic energy (see Prestwich, Brugger and Topping 1989) which is intimately related to environmental energetics (Gillooly and Ophir 2010). This creates an energetic constraint on acoustic communication while compelling the individual to produce a variety of sounds (Gillooly and Ophir 2010). It has been suggested that due to acoustic plasticity various environmental changes might immediately be reflected in the acoustic behavior of an organism (Klause and Farina 2016). Further, the acoustic performance has been shown to have been a result of complex interactions between the body mass of the individual, structure of social interactions, habitat heterogeneity, and energetic environment (Brackenbury 1979, Wallschläger 1980, Gibbs and Breisch 2001, Pröhl 2003, Ospina et al. 2013, Krause and Farina 2016, Goutte et al. 2018). Ospina et al. (2013) showed that in four species of rain frogs (Elutherodactylus) the calling activity differed in varying temperatures. They based their conclusions on the possibility of dehydration of the frogs which caused them to retreat to the closed area and stop calling. Further, Narins and Meenderink (2014) showed a correlation between climate change, altitudinal shift in the populations of E. coqui and change in acoustic patterns of migrating populations. However, for long, the effects of changes in the environmental energetics due to climate change, its effect on animal acoustics and ultimately its survival have remained elusive. In the current paper I propose a new hypothesis affecting the survival of anuran amphibians based on the current knowledge of the interactions between acoustics, individual metabolism, and environmental energetics.

Proposal

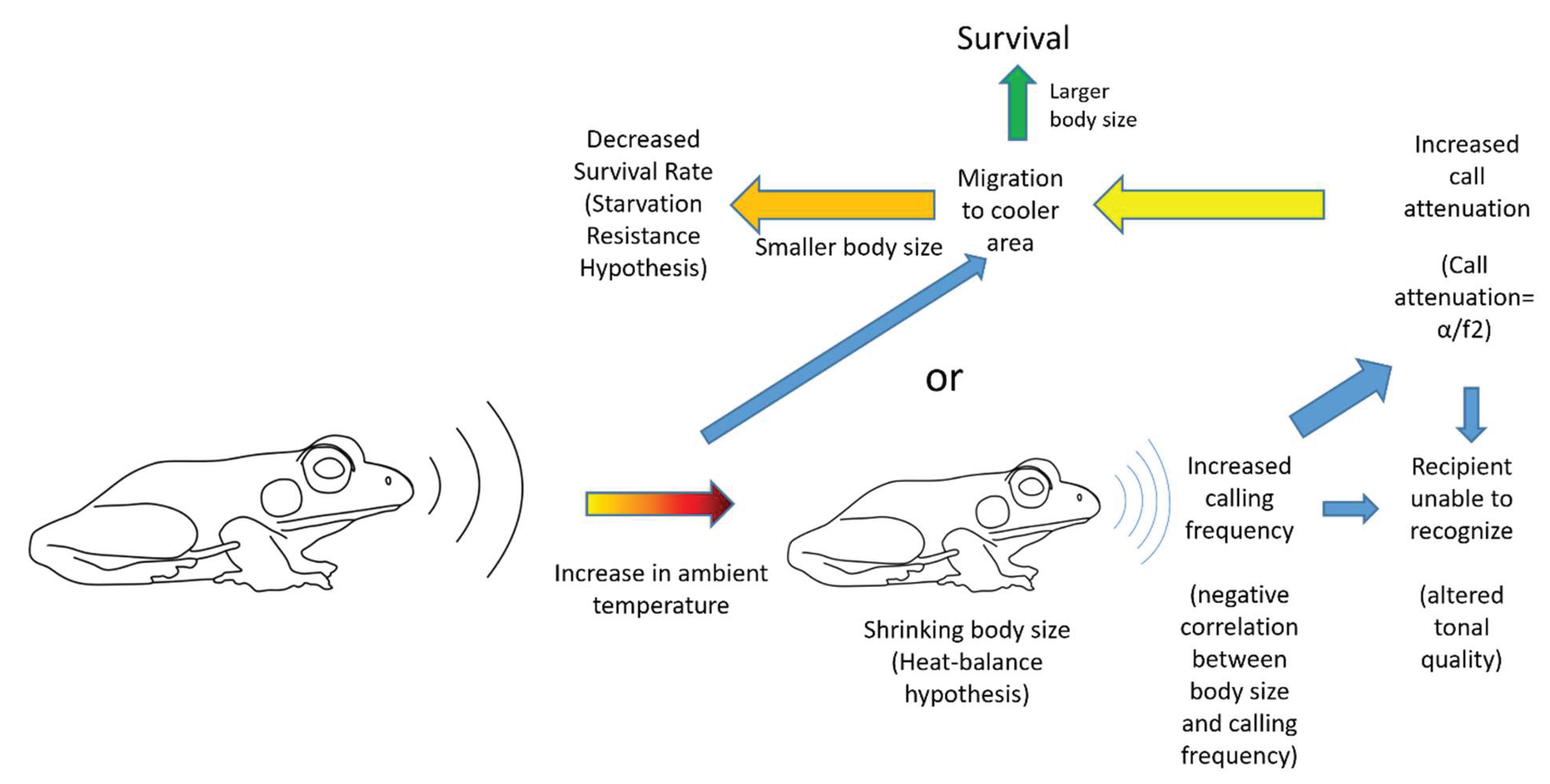

The first part of the proposal suggests that the global temperature rise will lead to selection of smaller individuals from the population of frogs (see Sheridan and Bickford 2011). It is supported by three prevailing hypothesis

1) Heat-balance hypothesis suggests that in ectotherms, which are below certain body size threshold and physiological and/or behavioral thermoregulatory abilities, larger body size would be favored in cooler climates where their low surface-to-volume ratio is better for conserving heat (Olalla-Tárraga and Rodriguez 2007). Anurans are below this threshold and are considered to be thermoregulators which should compel the selection of smaller size individuals under the global temperature increase.

2) The temperature-size rule (Atkinson 1994) states that for ectotherms, lower development temperature results in larger body size hence higher developmental temperatures due to global rise in temperatures might result in smaller body size individuals.

3) The starvation resistance hypothesis (Boyce 1979) states that larger animals are favored in cooler, more seasonal environments due to their larger capacity to store fat and use it to enhance survival during stress periods, mainly during overwintering. This also would mean that the smaller individuals will be selected in warmer conditions proposed due to global temperature rise

Second part of the proposal suggests that, the smaller individuals selected under these constraints will be producing calls with higher frequencies (Cunnington and Fahrig 2010, Gingras et al. 2013). The air particles move faster at higher frequencies losing the energy faster which is magnified by increase in temperature. Also, due to increase in temperature the smaller individuals (larger surface area) would dehydrate faster and would therefore would shift to cooler areas to avoid adversity (see Narins and Meenderink 2014). Therefore, the amplitude of these higher frequency calls would tend to die out faster in increased temperature scenarios. The animals would try to avoid such conditions by changing their geographical distribution leading to compromise in the availability of resources (Farina 2012). The local migrations under prevailing conditions would therefore drive the anuran amphibians to cooler areas for facilitating the propagation of calls and/or local or regional extinctions based on the extent of area where the ambient temperatures have increased.

This would however unleash the vicious cycle. The smaller sized individuals compelled to shift in cooler climates due to acoustic constraint would lose body heat faster than larger body individuals and would have lesser fat reserves to survive cooler climates which might ultimately lead to their death (see starvation resistance hypothesis).

The above sequence of events is termed here as an acoustic death. The phenomenon entails that the smaller individuals of anuran amphibians selected under the global warming conditions would produce higher frequency calls within the given population. Such individuals might remain undetected due to altered tonal quality or reduction in the distance travelled by the sound due to dampened amplitude under the increased temperature scenario magnified by higher frequency of calling. These individuals would then be driven to cooler areas to achieve the acoustic success. Nonetheless, in the cooler areas they would face a challenge of maintaining their metabolic energy due to lesser availability of fat reserves compared to larger individuals from the population. Therefore, inhabiting warmer or cooler climatic niches would be challenging to such individuals compromising their survival (

Figure 1).

Conflict Statement

Author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Atkinson, D. (1994). Temperature and organism size-a biological law for ectotherms?. Adv. Ecol. Res., 25, 1-58.

- Boyce, M. S. (1979). Seasonality and patterns of natural selection for life histories. The American Naturalist, 114(4), 569-583. [CrossRef]

- Brackenbury, J. H. (1979). Power capabilities of the avian sound-producing system. Journal of Experimental Biology, 78(1), 163-166. [CrossRef]

- Cunnington, G. M., & Fahrig, L. (2010). Plasticity in the vocalizations of anurans in response to traffic noise. Acta Oecologica, 36(5), 463-470.

- Cusano, D. A., Matthews, L. P., Grapstein, E., & Parks, S. E. (2016). Effects of increasing temperature on acoustic advertisement in the Tettigoniidae. Journal of Orthoptera Research, 39-47. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C. R., Beaman, J. E., Youngblood, J. P., Kellermann, V., & Diamond, S. E. (2023). Vulnerability to climate change increases with trophic level in terrestrial organisms. Science of The Total Environment, 865, 161049.

- Deutsch, C. A., Tewksbury, J. J., Huey, R. B., Sheldon, K. S., Ghalambor, C. K., Haak, D. C., & Martin, P. R. (2008). Impacts of climate warming on terrestrial ectotherms across latitude. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(18), 6668-6672. [CrossRef]

- Farina, A. (2012). A biosemiotic perspective of the resource criterion: Toward a general theory of resources. Biosemiotics, 5, 17-32.

- Gibbs, J. P., & Breisch, A. R. (2001). Climate warming and calling phenology of frogs near Ithaca, New York, 1900–1999. Conservation Biology, 15(4), 1175-1178. [CrossRef]

- Gillooly, J. F., & Ophir, A. G. (2010). The energetic basis of acoustic communication. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1686), 1325-1331.

- Gingras, B., Boeckle, M., Herbst, C. T., & Fitch, W. T. (2013). Call acoustics reflect body size across four clades of anurans. Journal of Zoology, 289(2), 143-150. [CrossRef]

- Häder, D. P., & Barnes, P. W. (2019). Comparing the impacts of climate change on the responses and linkages between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Science of the Total Environment, 682, 239-246.

- Lertzman-Lepofsky, G. F., Kissel, A. M., Sinervo, B., & Palen, W. J. (2020). Water loss and temperature interact to compound amphibian vulnerability to climate change. Global Change Biology, 26(9), 4868-4879. [CrossRef]

- Narins, P. M., & Meenderink, S. W. (2014). Climate change and frog calls: long-term correlations along a tropical altitudinal gradient. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1783), 20140401. [CrossRef]

- Olalla-Tárraga, M. Á., & Rodríguez, M. Á. (2007). Energy and interspecific body size patterns of amphibian faunas in Europe and North America: anurans follow Bergmann’s rule, urodeles its converse. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16(5), 606-617.

- Ospina, O. E., Villanueva-Rivera, L. J., Corrada-Bravo, C. J., & Aide, T. M. (2013). Variable response of anuran calling activity to daily precipitation and temperature: implications for climate change. Ecosphere, 4(4), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Prestwich, K. N., Brugger, K. E., & Topping, M. A. R. Y. (1989). Energy and communication in three species of hylid frogs: power input, power output and efficiency. J. exp. Biol, 144(1), 53-80.

- Pröhl, H. (2003). Variation in male calling behaviour and relation to male mating success in the strawberry poison frog (Dendrobates pumilio). Ethology, 109(4), 273-290. [CrossRef]

- Sage, R. F. (2020). Global change biology: A primer. Global Change Biology, 26(1), 3-30.

- Sheridan J. A., Bickford D. (2011). Shrinking body size as an ecological response to climate change. Nature Climate Change 1, 401– 406. [CrossRef]

- Wallschläger, D. (1980). Correlation of song frequency and body weight in passerine birds. Experientia, 36, 412-412.

- Ziegler, L., Arim, M., & Bozinovic, F. (2016). Intraspecific scaling in frog calls: the interplay of temperature, body size and metabolic condition. Oecologia, 181, 673-681. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).