1. Introduction

Mathematical modeling and numerical simulations are important tools for describing various nonlinear complex phenomena and processes, as well as implementing computer-aided design (CAD), computational fluid dynamics (CFD), and automatic control [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Flight mechanics (also called flight dynamics) is one of the engineering fields that benefits largely from mathematical modeling and numerical simulation; because simple analytical reduced-order solutions in aerospace applications and dynamics are typically not available except under very restrained conditions, and experimental techniques through wind-tunnel tests (WTT) and flight tests are stochastic (non-deterministic), expensive, limited in terms of the amount of data that can be measured directly, and sometimes intrusive (influencing the domain being tested) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Inverse simulation (InvSim) in flight mechanics (flight dynamics) is a normative category of flight mechanics modeling in which a desired flight trajectory (flight maneuver or flight mission) is specified through a number of inputs, while the corresponding flight controls (the model-based feedforward control variables) needed to achieve this trajectory are predicted; the opposite of this modeling process is called forward flight mechanics simulation, which is an exploratory category of flight mechanics modeling [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Accurate inverse simulation flight mechanics (flight dynamics) modeling facilitates advanced modes of transportation through pilotless (autonomous) aviation activities, such as regular electrified urban air mobility (e-UAM) trips within smart cities or between neighbor cities, powered by clean renewables; although additional real-time control systems for external perturbation suppression should be augmented [34,35,36,37,38].

This work is a sequel to a previous part in which we provided a detailed mathematical framework for general modeling the motion for a fixed-wing aircraft, and this framework has several advantages; namely: (1) all six degrees of freedom (6-DOF) are included, (2) the singularity of upward/downward vertical flight (encountered in a traditional Euler-angle representation) is avoided, (3) linear (translational) momentum equations are transformed such that the order of terms does not suffer from large discrepancy under fast dynamics, (4) the assumption of airplane symmetry is eliminated, (5) the aerodynamic details for all the flight-dependent aerodynamic/stability coefficients are clearly expressed, (6) three sets of axes: inertial ground/earth axes, body-fixed axes, and wind axes are utilized instead of using the Euler angles directly to describe the attitude of the airplane, (7) two flight-path angles (azimuth and elevation) are utilized as an intermediate spherical coordinate system; allowing the separation of the flight path direction relative to air (the airplane course) from the airplane attitude relative to the ground (the airplane heading), (8) only scalar equations (rather than vector equations or quaternions) are utilized, which simplifies the implementation process as a digital flight mechanics simulator, (9) the variation of the air density with altitude is accounted for using the international standard atmosphere (ISA) model for air as an ideal homogeneous gas, and (10) the model can be easily adjusted to specific airplane conditions through user-defined input parameters, and also specialized airplane features (such as a nonlinear lift coefficient profile) can be handled through minor modifications [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65].

The current work can be used within a curriculum module in college programs related to aeronautics, numerical methods, or control [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]

We do not address here social or economic aspects of flight and aviation modeling [75,76].

In the current work, the previously explained general nonlinear differential-algebraic equations (DAE) for flight mechanics are reformulated such that they fit specifically inverse simulation flight dynamics, and an algorithm is presented to numerically integrate these equations of motion (EOM) in a simple explicit process that does not require solving an algebraic system of equations, with the use of the fourth-order Runge-Kutta (RK4) numerical integration method; also numerical differentiation expressions based on the finite difference method (FDM) may be used [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84]. We implement this proposed numerical procedure as a computer code, and demonstrate its utilization while inversely simulating a continuous-double-roll maneuver with a set of airplane data that nearly corresponds to the Mirage III fighter aircraft, produced by the French aerospace company Dassault Aviation [85,86,87].

2. Research Method

2.1. Problem Statement

The inverse simulation (InvSim) flight mechanics algorithm proposed here considers the airplane as a MIMO (multi-input multi-output) control system, with four inputs and four outputs. The four inputs are specified as the inertial (ground-referenced) Cartesian coordinates (

) of the airplane’s center of gravity (CG), and these coordinates may be described as analytical functions of time or as discrete values recorded with the corresponding time values (or with a uniform time step,

. The (

) coordinate represents the signed distance traveled by the airplane in the positive geographic north direction from the initial flight point (the take-off point). The (

) coordinate represents the signed distance traveled by the airplane in the positive geographic east direction from the initial flight point. The (

) coordinate represents the signed distance traveled by the airplane toward the earth’s center from the initial flight point, and thus this coordinate is expected to have negative values except during parts of the maneuver where the airplane descends to an altitude below the initial altitude.

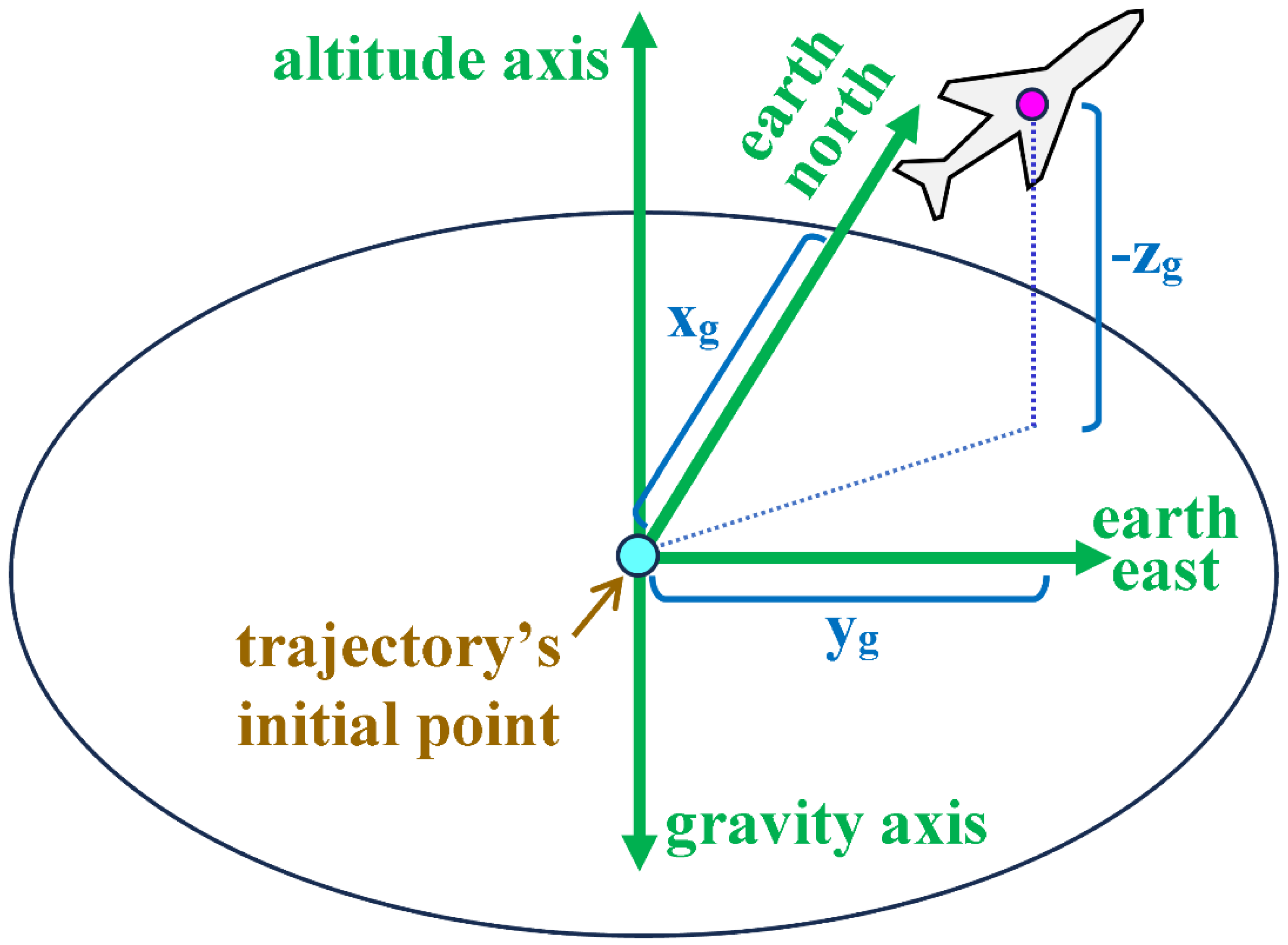

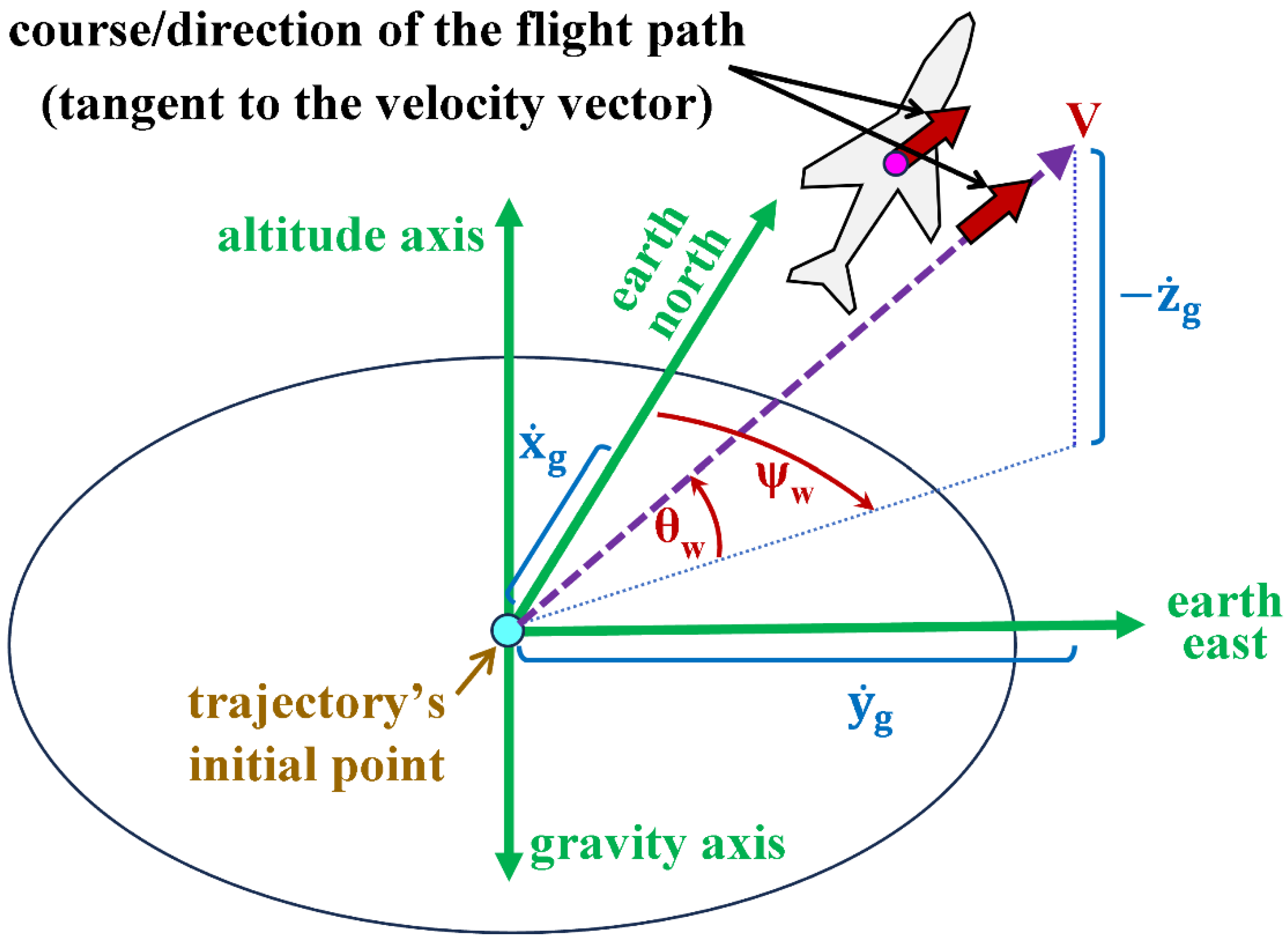

Figure 1 illustrates these three input coordinates. The term “gravity axis” here refers to the inertial axis pointing toward the earth’s center (perpendicular to the horizon plane), and it is opposite to the “altitude axis” that is also perpendicular to the horizon plane but points toward the sky. The origin of these ground-referenced rectangular coordinates is the initial flight point (the first location of the trajectory to be inversely simulated).

In the current work, the altitude of the airplane’s center of gravity as measured from the mean sea level (MSL) is designated by the symbol (

), and the initial altitude is designated by the symbol (

). Therefore, the gained height of the airplane’s center of gravity above the initial trajectory point is (

); which should be equal to the negative value of the (

) coordinate. Therefore,

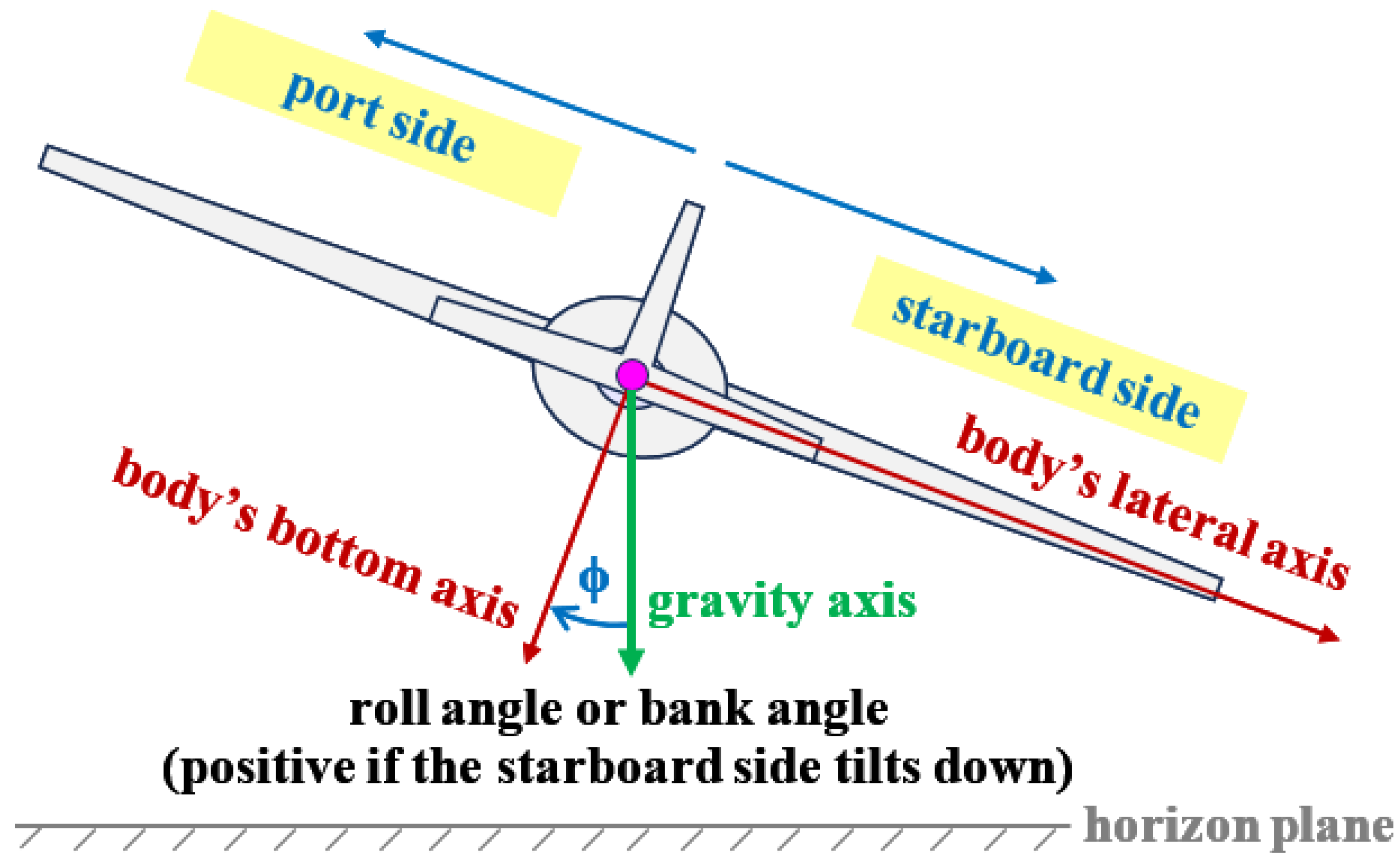

The fourth input to the airplane model is the bank angle (also called roll angle) in radians, which is one of the three Euler angles, and it describes the lateral attitude of the airplane. If the starboard (right) and port (left) tips of the wing are at the same vertical position (having the same altitude), then the bank angle (

) is zero. By convention, the bank angle is positive if the wing’s starboard tip tilts down (and the wing’s port tip tilts up) [88,89].

Figure 2 illustrates the bank angle when it has a positive value.

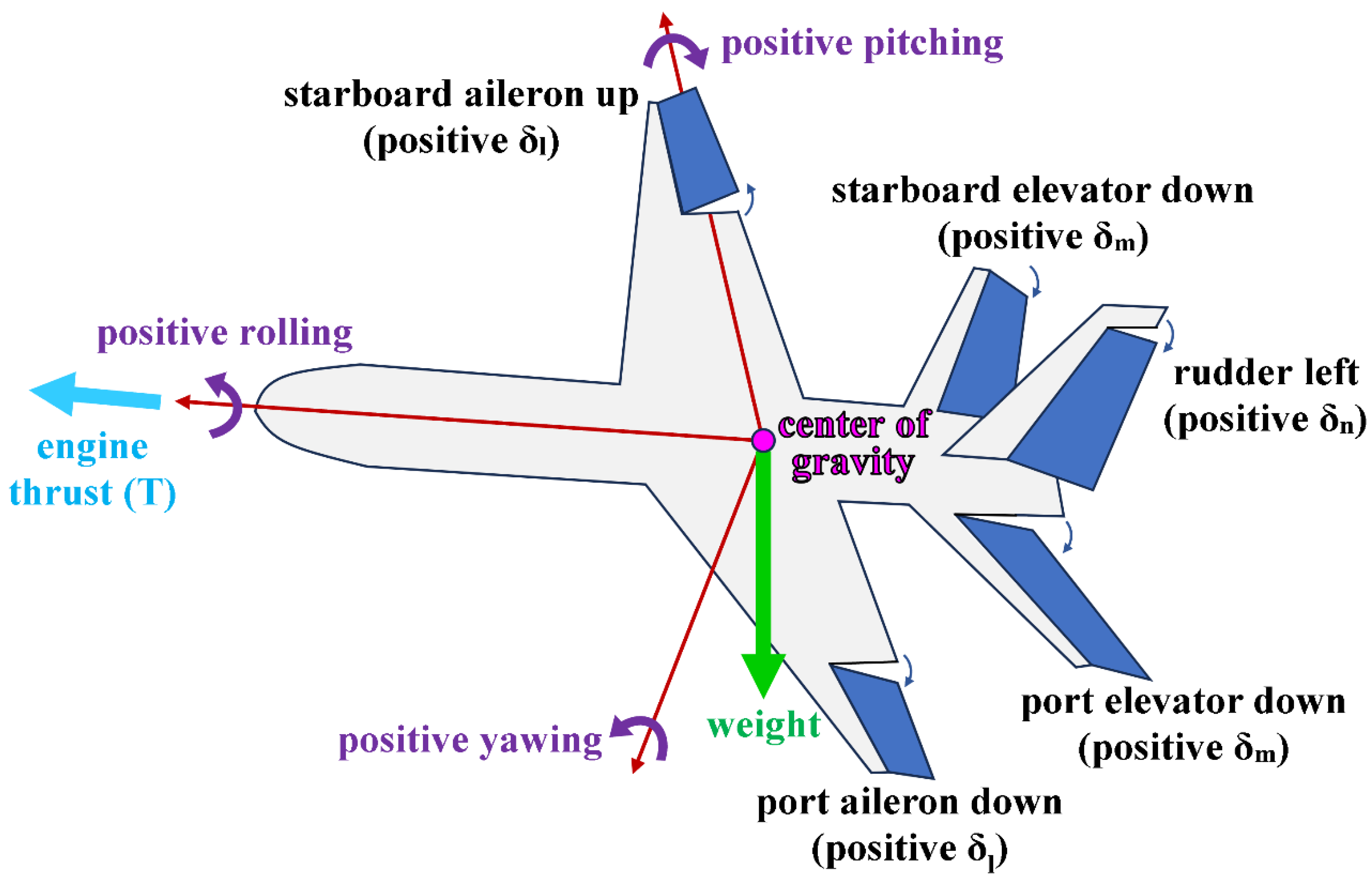

The four outputs from the inverse simulation flight mechanics model here are the four flight controls (four control variables), computed as four discrete series of values (four numerical vectors). These controls are in charge of adjusting the speed and orientation of the airplane, such that the input conditions are satisfied. These controls are:

The engine thrust force (), in newtons. This control can also be an electric propulsion force in the case of using an electric propeller or an electric ducted fan (EDF) [90,91,92,93,94]. This electrification has an environmental advantage through eliminating combustion emissions [95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108]. Hydrogen-based propulsion is also preferred environmentally due to the lack of harmful greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118]. The thrust force is a non-negative quantity.

The ailerons’ deflection angle (), in radians. This deflection is primarily in charge of the rolling degree of freedom. This deflection angle is positive when the hinged starboard aileron tilts up and simultaneously the hinged port aileron tilts down (which induces a positive bank angle, ).

The elevators’ deflection angle (), in radians. This deflection is primarily in charge of the pitching degree of freedom. This deflection angle is positive when both hinged elevators tilt down (which induces a positive pitch angle, , where the airplane’s nose tilts up).

-

The rudder’s deflection angle (), in radians. This deflection is primarily in charge of the yawing degree of freedom. This deflection angle is positive when the hinged rudder tilts toward the port/left side (which induces a positive yaw angle “heading angle”, , where the airplane’s nose tilts toward the port side).

Figure 3 illustrates these four flight controls.

2.2. Research Approach

In order to solve the stated problem in the previous subsection, symbolic mathematical manipulation is combined with computational methods to build and present here a proposed numerical algorithm for solving the inverse simulation flight mechanics problem. A general set of flight mechanics equations of motions are first presented. These equations are then reformulated to be in the inverse simulation InvSim) form, such that the four output flight controls can be obtained for specified inputs (trajectory coordinates and bank angle). Then, a proposed algorithm is presented, which allows numerically integrating the reformulated coupled differential-algebraic equations (DAE) in a simple way that can be implemented using a general-purpose computer programming language, without the need for specialized capabilities [119,120]. We here use the MATLAB/Octave programing language, which is a high-level interpreted language especially suitable for numerical computations, although other programing languages (such as Python) can also be used [121,122,123,124,125,126].

The success of the proposed computational InvSim algorithm and the underlying mathematical model is supported by numerically simulating an example flight maneuver. We obtained some symbolic expressions for needed derivative terms manually using normal calculus rules; and independently using Mathematica (a popular software tool for symbolic mathematics and computations that has been used in many research works before), and both sets of obtained expressions were exactly compatible [127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137].

3. General Equations of Motion

In this part, we present part of a flight mechanics mathematical framework, which is not optimized specifically for inverse simulations. The equations of motion listed in this section are not just the six main equations (three linear/translational momentum equations and three angular/rotational momentum equations) for a six-degree-of-freedom flight. Instead, auxiliary intermediate equations are also listed, since they need to be considered along with the six main equations as a whole integrated coupled system.

3.1. Angular Velocity Vector in Body Axes

The roll rate (

), pitch rate (

), and yaw rate (

) are related to the Euler angular rates or Euler rates (

) that are the time derivatives of the Euler angles, according to

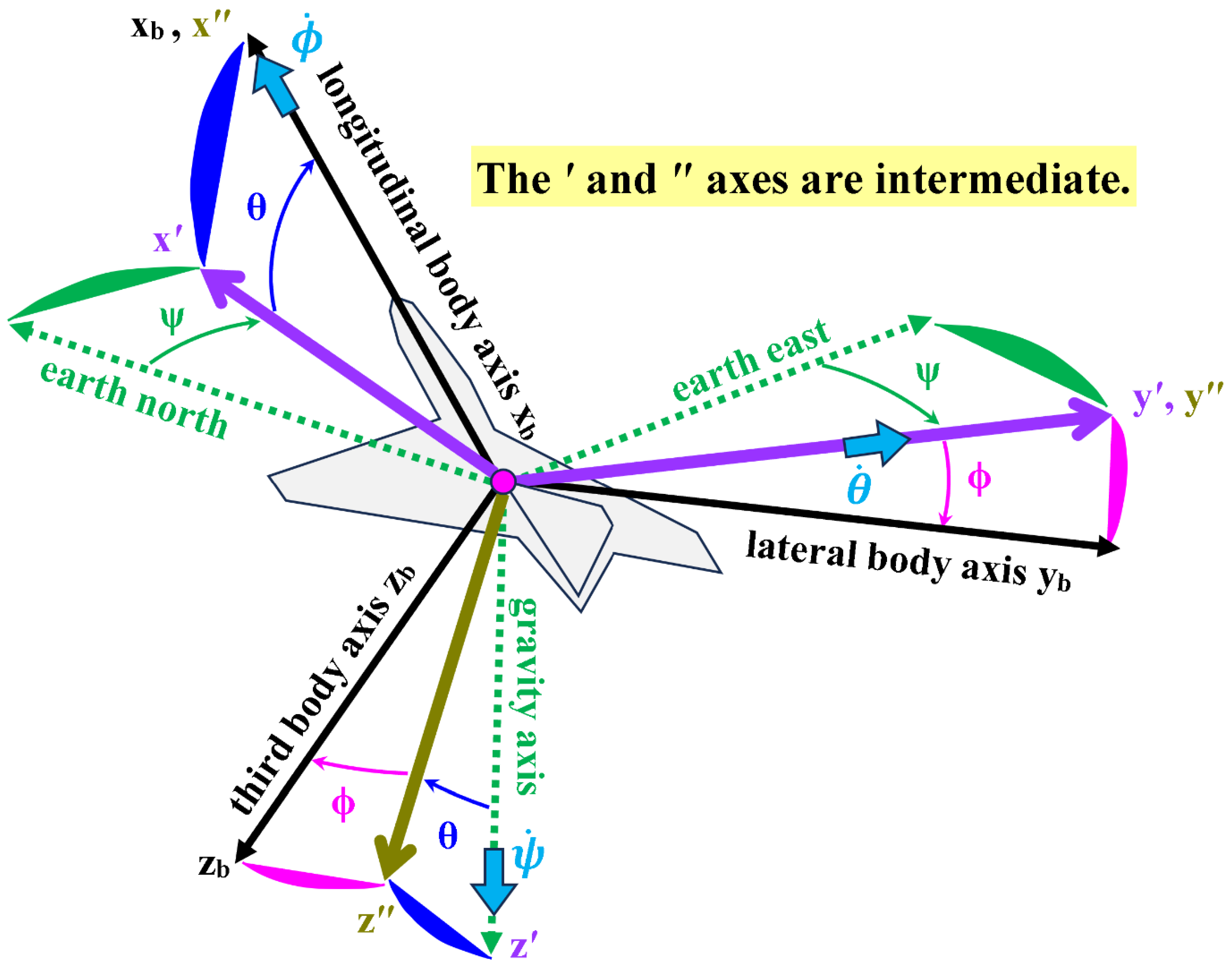

Figure 4 illustrates the three Euler angles (

) which describe the three-stage rotational transformation from the inertial axes system (north, east, gravity) into the body-fixed axes system (

).

3.2. Linear-Momentum Equations and Equilibrium

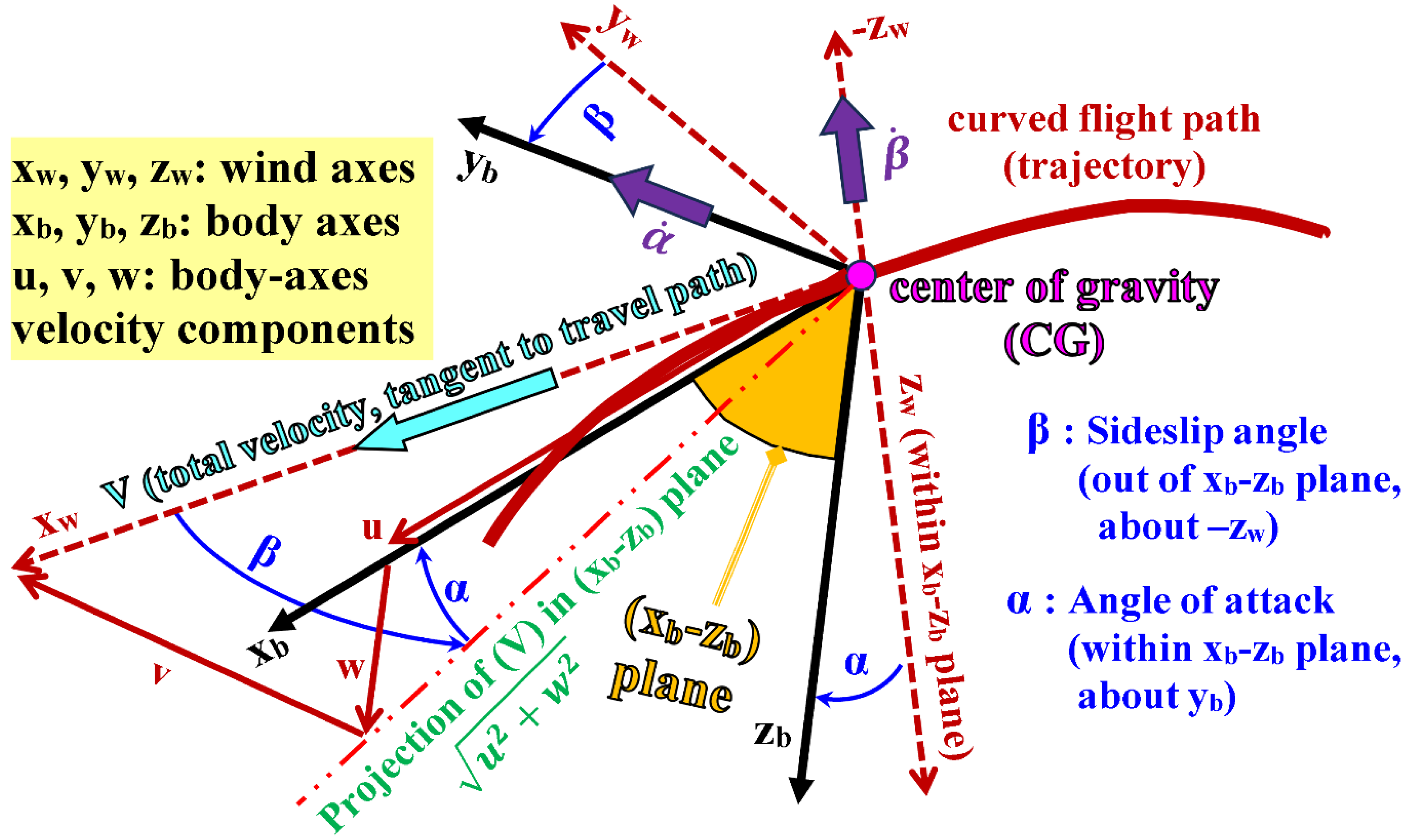

The linear-momentum equations are transformed from the orthogonal Cartesian system into the body-fixed spherical wind axes, whose coordinates are the velocity magnitude (), the sideslip angle (), and the angle of attack (). These three variables () can be viewed as spherical coordinates, with the velocity magnitude () being the radial coordinate. The forward wind axis is tangent to the flight path and thus coincides with the total velocity vector (velocity of the airplane’s center of gravity). The sideslip angle () represents a rotational transformation of the wind axes such that the rotated lies in the airplane’s fixed plane (the airplane’s midplane), which is the plane of symmetry for symmetric airplanes.

The condition (

= 0°) means that the incoming airflow relative to the airplane is symmetric with respect to the midplane. The angle of attack (

) represents a subsequent rotational transformation (after the

rotational transformation) such that the twice-rotated wind axes (

) coincide with the body-fixed axes (

).

Figure 5 illustrates the wind angles (

and

), as well as the relation between the wind axes system (

) and the body axes system (

).

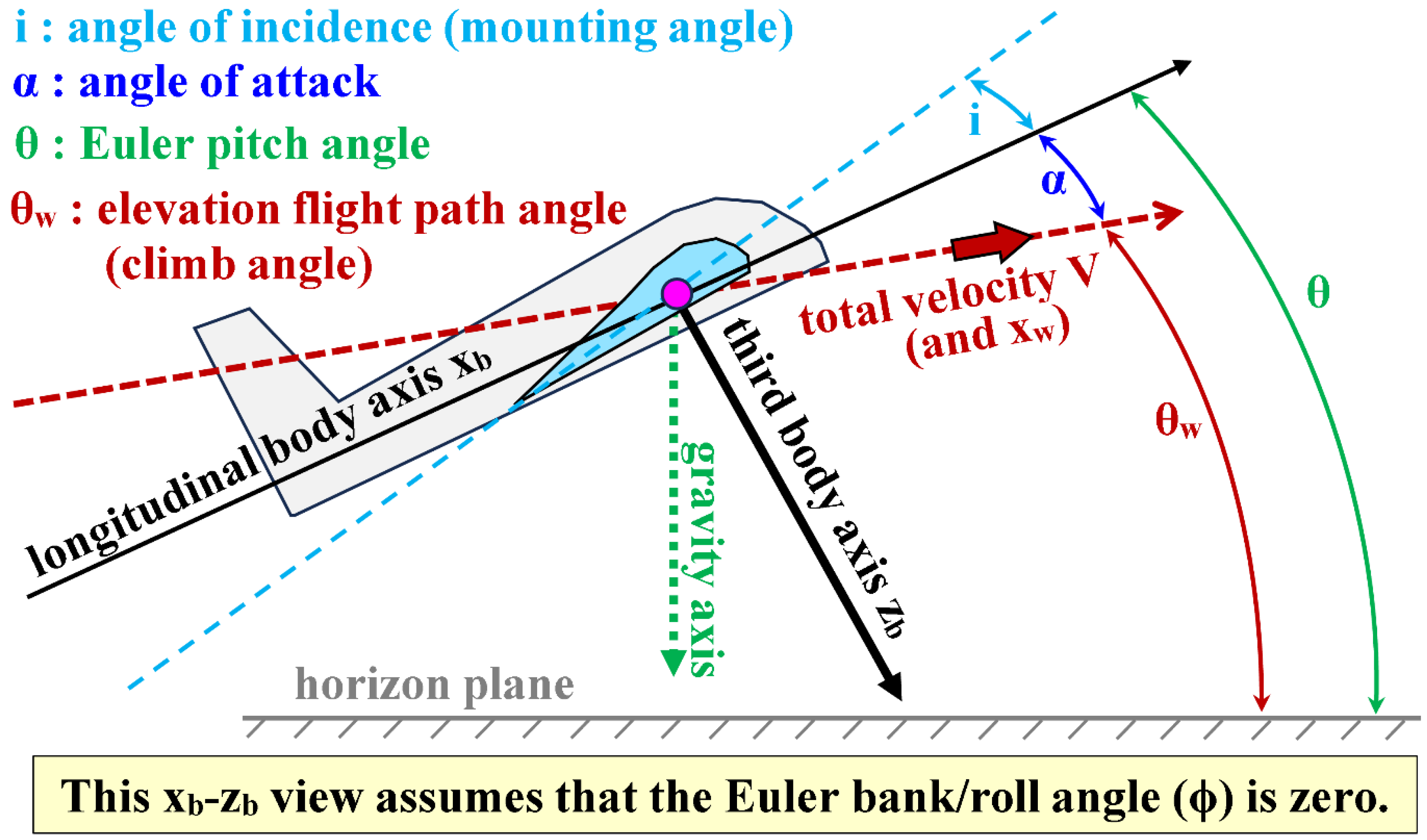

Although our definition for the angle of attack (AoA, ) discussed above, as a second angle of axes transformation, implies that in the absence of any sideslip ( = 0) and when = 0°, the longitudinal body axis () coincides with the forward wind axis (). This configuration corresponds to a horizontal steady-level flight with zero tilts by the airplane (the body-fixed plane is parallel to the horizon plane), and we refer to this configuration here as the “equilibrium” condition of flight. However, despite the horizontal orientation of the airplane’s body, and the zero value assigned to the angle of attack () as per our definition here, aerodynamic principles demand that there must be an exerted lifting force to counteract the weight of the airplane during an equilibrium flight.

The equilibrium lift force may require either using a nonsymmetrical (cambered) wing airfoil section while keeping the wing mounted parallel to the main airplane body (the fuselage), such that a non-zero upward lifting force can be induced even when the airplane is flying horizontally through the ambient air with its nose-to-tail longitudinal axis also being horizontal; or mounting the wing (which can be cambered or symmetric) at a small tilt angle called the angle of incidence or mounting angle (), such that when the airplane flies horizontally with a horizontal longitudinal body axis, there is still a non-zero lifting force that achieves the equilibrium condition because the tilted wing now faces the air asymmetrically, causing the air pressure at the lower surface of the wing to be higher than the air pressure at the upper surface of the wing due to the asymmetric air flow around the wing, and this leads to the upward lifting force component (combined with an aerodynamic drag force component) [138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152]. In the current study, we adopt the latter choice; thus, we assume that the wing is installed into the fuselage at an angle of incidence () that satisfies the equilibrium condition; and this tilt angle () is excluded from the angle of attack () used in the modeling and numerical simulation discussed here.

In the presented flight mechanics model here, the angle of attack (

) excludes any equilibrium angle between the velocity vector of the airplane’s center of gravity (whose magnitude is

) and the wing’s mean chord line (the virtual straight line connecting the leading edge with the trailing edge of the wing of an airfoil section) [153,154,155,156,157,158]. Therefore, the symbol (

) that appears in this study means the change in the conventional angle of attack (denoted here by the symbol

; and it includes the angle of incidence or the tilt of the wing relative to the velocity vector of the airplane) from its equilibrium conventional value (

), which is assumed to be equal to the angle of incidence in the current work. Therefore, we have

In aeronautics, the equilibrium conventional angle of attack () is not truly a constant, but it depends on the flight speed and air density (this, on the flight altitude). Thus, our assumption of equality between the equilibrium conventional angle of attack and the angle of incidence () implies that the angle of incidence is effectively adjustable also, for example through using movable flaps attached to the wing and these allow mildly adjusting the wing’s effective angle of incidence [159,160,161].

Figure 6 illustrates the difference between the angle of incidence (

) and the angle of attack (

), and also shows how they differ from the Euler pitch angle (

) discussed in the previous subsection, and from the elevation flight path angle (

) that describes the climb angle of the airplane based on its course of flight as a point particle.

The linear-momentum equations (with its components corresponding to the wind axes) are

where Equation (8) is the

component of the vector linear momentum equation, Equation (9) is its

component, and Equation (10) is its

component.

In the above equations, (

) is the airplane mass, (

) is the wing planform area, (

) is the thrust force, (

) is the Euler’s pitch angle, (

) is the gravitational acceleration, (

) are nondimensional force coefficients (to be discussed later), and (

) is the dynamic pressure defined as [162,163,164,165,166]

where (

) is the air density.

The gravitational acceleration is treated here as a universal constant with the value of 9.81 m/s

2

It may be useful to add here that if the linear/translational equations of motion are formulated along the body-fixed axes; then their three components along the longitudinal axis (

), the lateral body-fixed axis (

), and the third/bottom body-fixed axis (

); respectively; are

These are the three components of the following vector linear-momentum equation in the body-fixed axes:

where (

) are the three components of the velocity along the three body-fixed axes (

). The right-hand side in the above vector equation is the total applied forces on the airplane. The first part represents the aerodynamic forces, the second part represents the weight, and the third part represents the thrust force.

3.3. Angular-Momentum Equations

A derived geometric constant () needs to be computed once, and this constant is the determinant of the symmetric inertia tensor. The three diagonal components of this tensor are the moments of inertia (or rectangular moments of inertia) for rotations perpendicular to the three corresponding body axes (centered at the airplane’s center of gravity), which are positive numbers for a rigid body; while the off-diagonal elements are the products of inertia, which can be negative, zero, or positive numbers [167,168,169,170,171,172,173].

The constant (

) us expressed mathematically as

The SI unit of each component of the inertia tensor is kg.m

2, and thus the SI unit of (

) is kg

3.m

6. The six components of the inertia tensor are further explained in

Table 1.

For a symmetric airplane, the left (port) half is identical (but reflected) to the right (starboard) half; and in such a left-right symmetric condition, only the product of inertia in the symmetry midplane plane () is non-zero ( ≠ 0) in that case [174,175,176].

Because the rotational equations of motion are expressed in the body-fixed axes and the above inertia terms are formulated also with respect to the body-fixed axes, these inertia terms are considered invariant constants in the rotational equations of motion.

Three auxiliary moments (

) are defined through three algebraic equations as

Finally, the main rotational equations of motion for the airplane about its body axes are

In the special case of a symmetric airplane, the seven equations presented in the current subsection, namely Equations (13-19), can be replaced by only three differential angular-momentum equations that are listed below; which can be derived from Equations (13-19) after setting (

= 0) and (

= 0) and performing some mathematical manipulation [177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185].

which can be further manipulated and expressed using the alternative symbols for the inertia terms as

3.4. Inertial Velocity

The equations relating the rates of the ground-referenced inertial coordinates (

) to the velocity magnitude and the spherical flight path angles (azimuth flight path angle

, and elevation flight path angle

) are

Figure 7 illustrates the two spherical flight path angles (

and

), which describe the flying course (direction) of the airplane, as a particle, with respect to the inertial origin (the initial trajectory point) using the three spherical coordinates (

) as an alternative to the Cartesian inertial velocity components (

).

3.5. Flight Path Angles

Two additional algebraic equations relate the two flight path angles (

) to the three Euler angles (

) and the two wind axes angles (

,

) are provided below [186,187,188,189,190,191].

From the two above equations; it can be proven that in the condition of equilibrium flight ( = 0, = 0), the Euler yaw angle () “also called heading angle” becomes equal to the azimuth flight path angle (), and the Euler pitch angle () becomes equal to the elevation flight path angle ().

3.6. Three Aerodynamic Forces

The three body-axes aerodynamic forces acting on the airplane are expressed as

In the above equations, () is the aerodynamic force along the longitudinal body-fixed axis, and its unit vector exactly coincides with the unit vector of the thrust vector; () is the aerodynamic force along the starboard lateral body-fixed axis; and () is the aerodynamic force along the third (bottom) body-fixed axis.

3.7. Three Moments

The total moment vector is resolved into three components (which we also refer to as three moments) along the body axes. These moments are expressed in terms of nondimensional moment coefficients (

) as

In the above equations, () is the rolling moment about the longitudinal body-fixed axis (), () is the pitching moment about the lateral body-fixed axis (), and () is the yawing moment about the third/bottom body-fixed axis (). In addition, () is a characteristic length for the pitching moment (longitudinal stability), such as the mean wing chord [192,193,194]. On the other hand, the characteristic length () pertains to the rolling moment (lateral stability) and yawing moment (directional stability), and it can be the wing span [195,196,197,198,199].

3.8. Aerodynamic and Stability Coefficients

The aerodynamic lift coefficient (), aerodynamic drag coefficient () [200,201,202,203], and aerodynamic side-force coefficient () are wind-axes nondimensional quantities from which the body-axes aerodynamic coefficients () can be obtained [204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211].

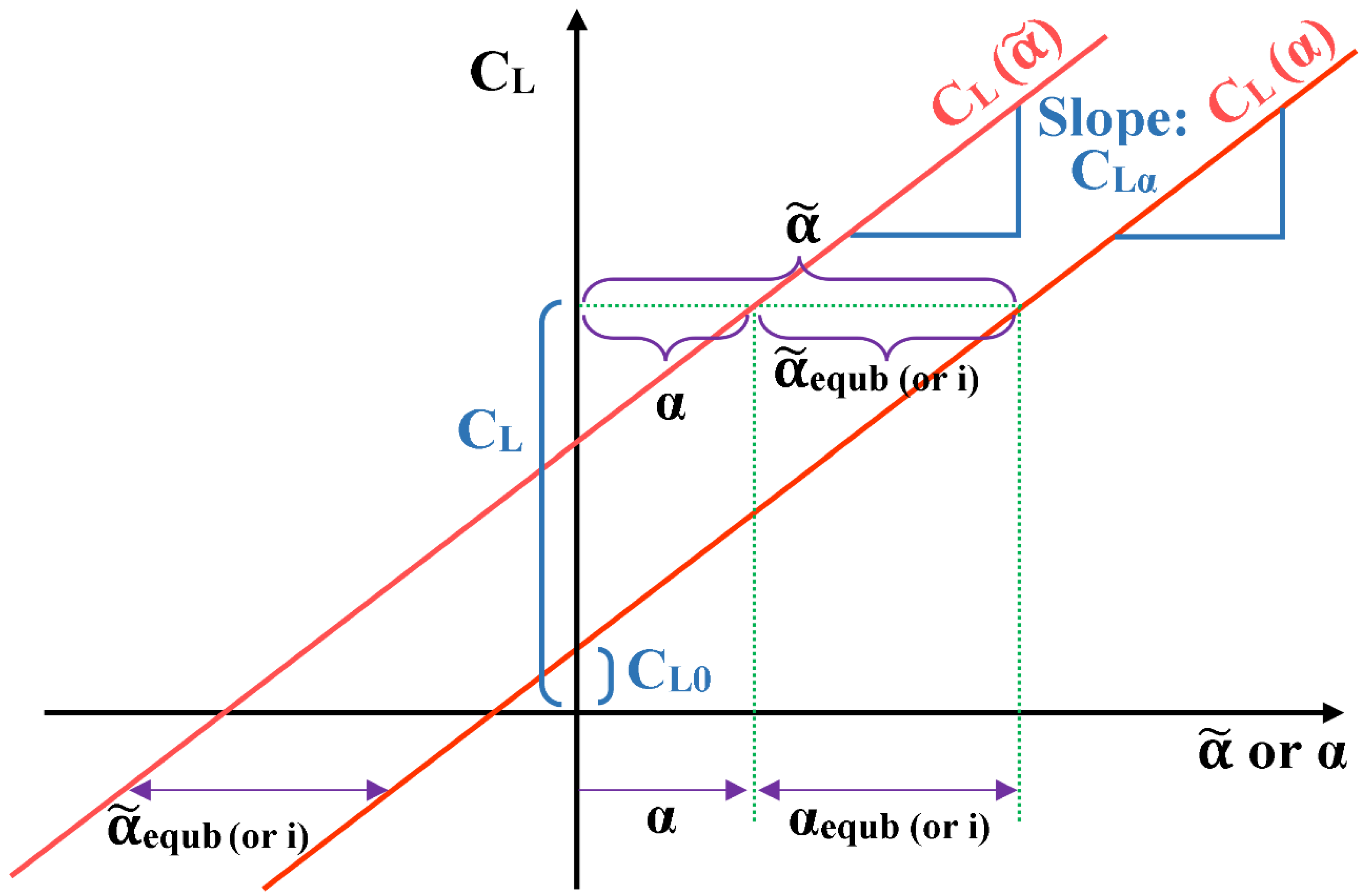

The lift coefficient is modeled here as being directly related to the conventional angle of attack (

) as

where (

) is the lift coefficient at zero conventional angle of attack, and (

) is the gain in the lift coefficient per unit increase in the angle of attack (when expressed in radians), and both values are treated as constant parameters.

As mentioned earlier in subsection 3.2, the term “angle of attack” (

) used in the proposed flight mechanics simulation modeling here is the change (either positive or negative) in the conventional angle of attack from its equilibrium value (

), which is assumed to be equal to the angle of incidence for the wing (

). Therefore, the lift coefficient (

) is related to the modeling/simulation angle of attack (

) as

Regardless of the lift coefficient being expressed as a function of the conventional angle of attack (

) as in Equation (37), or being expressed as a function of the modeling/simulation angle of attack (

) as in Equation (38), it has the same constant slope (

). At any given value of (

), the angular difference (

) is equal to the equilibrium value of the conventional angle of attack (

; and it is computed from the force balance between the weight of the airplane (

) and the equilibrium lift force (

), where (

) is the lift coefficient at equilibrium flight. Therefore,

Combining the above defining equation for the equilibrium lift coefficient with Equation (37) that relates the lift coefficient (

) linearly with the conventional angle of attack (

) gives

and this leads to an explicit expression for the conventional equilibrium angle of attack (

as

This conventional equilibrium angle of attack ( is approximately constant if the dynamic pressure is nearly constant (), and this implies that the air density and the flight speed are nearly unchanged, and this is a valid assumption in steady-level flight.

Figure 8 illustrates the linear dependence of the lift coefficient (

) on the modeling/simulation angle of attack (

), which is the default angle of attack in the current work, and on the conventional angle of attack (

) as described above. This linear dependence is appropriate as long as the airplane is away from aerodynamic stall conditions [216,217,218,219,220,221,222].

Through the drag polar relationship, the drag coefficient depends on the lift coefficient as [223,224,225]

where (

) and (

) are additional aerodynamic constants.

The side-force coefficient depends on the sideslip angle as

After knowing the wind-axes aerodynamic coefficients (

), the body-axes aerodynamic coefficients (

) can be obtained using trigonometric projections as

The body-axes total-moment coefficients (

) are modeled as

where (

) are nondimensional constant parameters, while (

) are dimensional constant parameters having the unit of 1/rad, (

) is the ailerons’ deflection angle in radians, (

) is the elevators’ deflection angle in radians, and (

) is the rudder’s deflection angle in radians.

3.9. Air Density and Speed of Sound

The variation of the air density with the altitude (

) is governed here by the International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) model. Up to an altitude of about 11,000 m above mean sea level, the stratosphere layer of the air exists, in which the air temperature decreases linearly with altitude, while the density declines nonlinearly with altitude at a faster rate according to [226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234].

where (

) is the lapse rate magnitude, taken as 0.0065 K/m; and (

) is the ideal gas constant for air, which is the universal molar gas constant divided by the molecular weight, and this gas constant for air is 287 J/kg.K [235,236,237,238]. In the previous equation, the constant 1.225 is the standard sea level air density in kg/m

3 (

); and the constant 288.15 is the standard sea level absolute temperature in kelvins (

), which corresponds to 15 °C [239,240,241,242,243].

Although the ISA model is based on geopotential altitudes for estimating the air density, we here utilize the true geometric (orthometric) altitude [244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256]. This simplification is aligned with our treatment of the gravitational acceleration as a universal constant. We assessed the difference in the two types of altitudes, and we found that the difference in the stratosphere layer of interest here is small as shown in

Table 2.

The percentage deviations in the above table are very small, much less than 1%. These percentage deviations were computed as [257]

The relationship between the geometric altitude (

) and geopotential altitude (denoted by

) is

where (

) is the mean radius of the earth, and it is taken here as 6,371,000 m [258,259,260,261,262].

In

Table 3, we further assess the influence of using a geometric altitude rather than a geopotential altitude when using Equation (37) for computing the air density. At a geometric altitude of 5,000 m for example; the air density should be computed strictly speaking at the slightly-lower geopotential altitude of approximately 4,996 m. Similarly, the air density computed at a geopotential altitude of 5,000 m strictly speaking corresponds to the slightly-higher geometric altitude of approximately 5,004 m. However, the values in the table show that these three densities are nearly the same, and the error incurred by the simplifying assumption of using the geometric altitude in lieu of the geopotential altitude leads to a marginal error in the air density that is below 0.05% at altitudes near 5,000 m; corresponding approximately to the middle of the stratosphere layer of the atmosphere.

Similarly,

Table 4 assesses the expected error in the air density but at higher altitudes near 10,000 m; located close to the upper end of the stratosphere layer of the atmosphere. Although the error grew (nonlinearly) as the altitude increased, it remains very small, below 0.2%.

Many commercial transport airplanes fly at cruising altitudes below 11 km, thus the stratospheric formula is adequate for them [263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271]. For higher altitudes, as in military aircraft, another expression for the air density should be used, which corresponds to the tropopause layer of the atmosphere; it is an interspheric layer between the lower troposphere layer and the upper stratosphere layer, extending approximately between the altitudes 11,000 m and 20,000 m [272,273,274,275,276,277]. In the tropopause layer of the atmosphere, the temperature is treated as constant (with a value of –56.50 °C or 216.65 K, making it an isothermal layer. Therefore, the decline of the air density with the altitude within the tropopause layer follows a different profile than the one described earlier for the non-isothermal troposphere layer. This decline is described as

where the value (11,000) is the altitude (in meters) at the bottom edge of the tropopause layer, the value (0.3636309) is the air density at 11,000 m (

) in kg/m

3, as computed by the tropospheric density equation, and this value is also the air density at the bottom edge of the tropopause layer; and the value (216.65) is the absolute temperature (in kelvins) of air within the tropopause layer (

).

It is worth mentioning that the decline of the air density in the non-isothermal troposphere layer is slower than its decline in the isothermal tropopause layer, because the drop of temperature in the non-isothermal troposphere layer has a compressive effect on air, causing its density to tend to increase, however the drop in the pressure due the diminishing weight of the above air column causes a stronger expansive effect of decreasing the density, which ultimately declines with the altitude [278,279,280,281,282]. In the isothermal tropopause layer, the compressive temperature effect is eliminated, thereby magnifying the expansive pressure effect, and thus the air density declines faster with the altitude. To demonstrate this faster rate of density decline in the isothermal tropopause layer, applying Equation (54) for the tropospheric density to an altitude of zero (= 0) gives an extrapolated benchmarking value sea-level air density of 2.0624 kg/m3, which clearly exceeds the true sea level value of 1.225 kg/m3 [283,284].

Although the speed of sound (

) in air is not an essential variable in the presented flight mechanics model, it is still an important property in aeronautics in general, because the ratio between the airplane speed (

) and the speed of sound is the nondimensional Mach number (

) that serves as a criterion for determining the regime of flight as well as the possible occurrence of special phenomena such as shock waves. The Mach number is defined as

The flight regime with is subsonic, the flight regime with is transonic or sonic, the flight regime with is supersonic, while the condition corresponds to the hypersonic flight regime [285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292].

The speed of sound for air, as an ideal gas, depends on its absolute temperature (

) and the specific heat ratio (the ratio of specific heat capacities, or the adiabatic index,

) as [293,294,295]

In the troposphere layer of the atmosphere (the non-isothermal layer adjacent to the ground), the air absolute temperature is estimated according to the lapse rate (

K/m) as

In the tropopause layer of the atmosphere (the isothermal layer next to the troposphere layer), the air absolute temperature is treated as a constant value of 216.65 K. Thus,

The specific heat ratio is treated here as a constant with a value of 1.4, which is commonly assigned to ambient air [296,297,298,299].

4. Summary of Equations, Variables, and Constants

In the current section, we provide a summary of the overall six-degree-of-freedom (6-DOF) fluid mechanics problem in terms of the mathematical structure.

4.1. Summary of Equations

The current fluid mechanics problem is described by a nonlinear differential-algebraic equations (DAE) system, consisting of 35 equations that are either ordinary differential equations (ODE) or algebraic equations. These 35 scalar equations can be grouped into nine categories as shown in

Table 5. It should be noted that these groups are not mathematically decoupled; the grouping is based on the scope of use for the equations.

4.2. Summary of Variables

The aforementioned 35 flight mechanics equations have 39 independent variables, which are listed in

Table 6 as categorized groups. It should be noted that constant parameters that appear in the differential-algebraic equations (such as the wing planform area and the airplane mass) are not included among the flight variables, because they are invariant during the entire flight trajectory. In addition, the time derivative of a flight variable is not considered an additional variable.

The difference between the number of equations and the number of variables is four, and this is the number of input constraints that should be specified in order to be able to integrate the flight mechanics system and obtain a unique solution. The four constraints in the case of our inverse simulation (InvSim) flight mechanics model are the profiles of the three inertial coordinates () and the profiles of the bank angle (). The output variables to be obtained by the InvSim flight mechanics solver are the discrete profiles of four airplane controls, which are the thrust and the three deflection angles of the control surfaces (). The remaining 31 variables (such as the angle of attack , and the Euler pitch angle ) are intermediate quantities that can evolve over time during the flight maneuver in response to changes in other related variables.

4.3. Summary of Constants

In addition to the 39 flight variables (that generally vary during the flight maneuver), various constant parameters need to be defined, and these values remain unchanged during the entire flight simulation. The total number of constants in the proposed InvSim model is 30, which are classified as 29 parameters for describing the airplane and its performance, and one parameter related to the trajectory (the initial altitude). These 30 constant parameters are summarized in

Table 7, which are organized as related groups.

It should be noted that physical universal constants are not counted among the 30 parameters, because these are not customizable quantities. These universal constants are

Gravitational acceleration ( = 9.81 m/s2)

Tropospheric lapse rate ( = 0.0065 K/m)

Ideal gas constant for air ( = 287 J/kg.K)

Standard sea-level air density ( = 1.225 kg/m3)

Standard sea-level air absolute temperature ( = 288.15 K)

Standard altitude of the troposphere-tropopause transition (11,000 m)

Standard air density at the troposphere-tropopause transition ( = 0.3636309 kg/m3)

Standard air absolute temperature within the tropopause layer ( = 216.65 K)

While it is possible to upgrade the model by treating the gravitational acceleration as a function of altitude (in this case, the number of flight variables increases from 39 to 40); the gain from this upgrade is not justified. This change largely increases the mathematical complexity of the model, where the time derivative of the gravitational acceleration appears in the mathematical expressions, while such a derivative is practically zero.

To demonstrate this (and justify treating the gravitational acceleration as a universal constant), we first point out that the altitude-dependent gravitational acceleration (

) declines with the geometric altitude according to the following quadratic relationship:

At a geometric altitude of 11,000 m (which is the upper limit of the troposphere layer), the altitude-dependent gravitational acceleration is 99.656 % of its approximated constant value (at sea level); and a higher geometric altitude of 20,000 m (which is the upper limit of the tropopause layer), the altitude-dependent gravitational acceleration drops further to 99.375% its approximated constant value. Thus, the relative drops in the gravitational acceleration at 11,000 m and 20,000 m geometric altitudes are only 0.344% and 0.625%; respectively. As dimensional drops in the altitude-dependent gravitational acceleration from a sea-level value of 9.81 m/s2; the respective drops at 11,000 m and 20,000 m geometric altitudes are 0.0033788 m/s2 and 0.006130 m/s2; respectively. At a rate-of-climb (RoC) of 2,000 ft/min (33.33 ft/s, 10.16 m/s, or 36.58 km/h), which is typical for a commercial jet airplane, an altitude of 11,000 m (36,089 ft) can be reached after a continuous climb for about 1,083 seconds (about 18 minutes); and this means that the average rate of change of the altitude-dependent gravitational acceleration in this case is approximately 3.12×10–6 m/s3, which is nearly zero [300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307]. Although high-performance fighter airplanes may achieve much higher climb rates and descent rates, such as 20,000 ft/min (10 times the typical rates for commercial jet airplanes), the time rate of change in the altitude-dependent gravitational acceleration in such cases remains negligible [308,309,310,311,312,313,314].

For estimating the speed of sound in air, one more universal constant was utilized, which is the nondimensional specific heat ratio [315] (or adiabatic index) for air, which is set at the reasonable value of 1.4.

Although the specific heat ratio for air, as an ideal gas, is actually a function of its temperature, which is a function of the altitude within the troposphere layer; treating the specific heat ratio as a universal constant as adopted here is appropriate given the narrow range of temperatures for atmospheric air during an airplane flight [316]. In this case of a constant specific heat ratio, air is assumed to be a “calorically perfect” gas, which is a special simplified case of ideal gases [317,318]. For air, the specific heat ratio is 1.4022 at 288.15 K (15.00 °C) and it increases to 1.4027 at 216.65 K (–56.50 °C); while it drops to 1.4015 at 323.15 K (50.00 °C); and these values show the weak deviation from the nominal used value of 1.4 [319].

5. InvSim Customized Equations of Motion

In this part, we present a variant of the general fluid mechanics equations of motion, which is adapted for use in an inverse simulation (InvSim) mode. These customized equations are presented as nine groups in the next subsections, with a different order than the one presented earlier for the general equations in section 3; this change in order facilitates explaining the rationale behind the need for additional derivative expressions beyond those appearing in the general flight mechanics equations.

In summary, the three unknown control deflection angles are computed from three algebraic equations, while the unknown thrust force is computed among eight flight variables through a classical fourth-order Runge-Kutta method (RK4) for integrating a system of nonlinear ordinary differential equation (ODE) [320,321,322,323,324,325].

5.1. InvSim Aerodynamic and Stability Coefficients

The formulas presented earlier in subsection 3.8 for the aerodynamic lift coefficient (

), aerodynamic drag coefficient (

), the side-force coefficient (

), and the three body-axes aerodynamic coefficients (

) remain in use in the transformed InvSim mode of the flight mechanics equations of motion. For completeness, these expressions are repeated here.

However, the original expressions for the body-axes total-moment coefficients (

) are restructured into three explicit expressions to obtain the three control surface deflection angles. The original expressions for the body-axes total-moment coefficients (

) are repeated below to facilitate the derivation of the restructured ones.

From Equation (48), the restructured explicit expression for the necessary control surface deflection angle for the elevators (

) can be obtained as

Solving Equations (47 and 49) simultaneously for the necessary control surface deflection angle for the ailerons (

) and the rudder (

) gives

The coupling between the rolling and yawing moments is noticeable from Equations (47 and 49), and these two moments are together decoupled from the pitching moment as indicated by Equation (48); this behavior is known for fixed-wing airplanes [326,327,328,329,330,331].

5.2. InvSim Three Moments

In subsection 3.7 of the original general flight mechanics formulation, the total moment vector was resolved into three components (three moments; ) along the body axes (); and these body-referenced moments were expressed in terms of three nondimensional moment coefficients (), respectively. However, in the previous subsection 5.1, we showed that the proposed InvSim flight mechanics formulation requires the values of these nondimensional moment coefficients to algebraically obtain the corresponding control surface deflection angles ().

Therefore, the original expressions for (

) are inverted here to be explicit expressions for (

), as follows:

5.3. InvSim Angular-Momentum Equations

In the part of the original general flight mechanics formulation covered earlier in subsection 3.7, algebraic expressions for three auxiliary moments (

) were given as functions of the body-referenced angular velocity components (

) and body-referenced total moments (

); with the body-axes inertia components (

) being constant geometric parameters. These expressions are repeated below.

Also, the original general flight mechanics formulation in subsection 3.7 included three main rotational equations of motion for the airplane about its body axes, which are repeated below.

As explained before, () is the determinant of the inertia tensor.

However, according to the discussion given in the previous subsection, the body-referenced total moments (

) are needed in order to obtain the corresponding nondimensional moment coefficients (

). These body-referenced total moments are obtained by solving simultaneously the above system of three equations, Equations (17-19), for the auxiliary moments (

) as three explicit expressions whose right-hand side include the body-referenced angular accelerations (

). The resultant explicit symbolic expressions for (

) and (

) are complicated and thus are not shown here; but we designate them by the placeholder symbols (

) and (

), respectively. However, the explicit symbolic expressions for (

) is simple enough to be shown here, and it is given below and we designate it by the symbol (

) to distinguish it from the original explicit expression in Equation (16) that also has (

) in its left-hand side as a single quantity, but that original expression is not directly used in the proposed InvSim algorithm presented here.

After the values of the auxiliary moments become known at a given time station, the body-referenced total moments (

) can be computed using an adapted version of the equations that defined the auxiliary moments (

); namely Equations (14, 15, 16), respectively. These adapted equations are suitable for computing the numerical values of (

), and they have the following form:

5.4. InvSim Angular Velocity Vector in Body Axes

The expressions relating the body-referenced roll rate (

), body-referenced pitch rate (

), and body-referenced yaw rate (

) to the Euler rates and Euler angles remain the same. These expressions were presented in Equations (2-4), and are repeated below.

The above algebraic expressions for the body-referenced angular velocities () are used to find initial values () for them at the beginning of the maneuver’s numerical simulation, at = 0.

According to the InvSim customized expressions (

) discussed earlier in the previous subsection 5.3 for the auxiliary moments (

), it is required to know the values of the derivatives of the body-referenced angular velocities (

) in order to be able to compute the dependent values of the auxiliary moments (

). Expressions for these three body-referenced angular accelerations (

) are obtained symbolically by direct differentiation of the expressions for (

) as presented in Equations (2-4). The resultant expressions for the body-referenced angular accelerations are

5.5. InvSim Flight Path Angles

The obtained explicit expressions for the three body-referenced angular accelerations (

) in the previous subsection, Equations (71-73), contain the Euler angular velocities (

) and the Euler angular accelerations (

). While (

) is considered available (either through numerically differentiating twice the input series values of

or through evaluating a symbolic expression for it if

is provided as a double-differentiable function of time), additional analytical expressions are needed for (

) and (

). These can be obtained by symbolically differentiating the two algebraic equations that relate the two flight path angles (

) to the three Euler angles (

) as well the angle of attack (

) and the sideslip angle (

). These two algebraic equations are repeated below.

After performing symbolic differentiation twice, the resultant equations can be manipulated to obtain the explicit expressions for () and (), as well as for the first derivatives () and (). These () and () expressions are used in initializing the time loop for the numerical integration through the maneuver’s discrete-time stations by estimating () and () at the start of the maneuver’s simulation.

The symbolic explicit expressions for (, , , ) are too complicate to be shown here with convenience. So, we alternatively refer to these four symbolic explicit expressions using the placeholder symbols , , , and ; respectively.

5.6. InvSim Linear-Momentum Equations and Equilibrium

The first equation of the wind-referenced linear-momentum equations, which is Equation (8), can be reformulated to be an explicit expression for the thrust force (

), as follows:

This algebraic explicit expression for the thrust () is used at the InvSim initialization stage for computing an initial thrust value (). Although the previous expression for () has a singularity at ( = ±90° or ±π/2 rad), these conditions are not realistic for a fixed-wing airplane as they imply that the airplane is flying relatively perpendicular to its wing’s surface. Also, although the previous expression for () has a singularity at ( = ±90° or ±π/2 rad), these conditions are not realistic for a fixed-wing airplane as they imply that the airplane is drifting sideways by flying laterally, perpendicular to its longitudinal axis [332,333,334,335].

The explicit symbolic expressions ( and ) discussed in the previous subsection involve the second time derivative of the angle of attack () and the second time derivative of the sideslip angle (), which appear in the right-hand side of () and (). Therefore, two additional explicit symbolic expressions (to be denoted by the placeholder symbols and ) are needed, which describe mathematically the second derivatives ( and ), respectively. Like ( and ), the explicit expressions ( and ) are very complicated and are not shown here, but we discuss next how these expressions can be obtained.

We provide below a reformulated version of the third equation of the wind-referenced linear momentum equations, which is Equation (10) that represents the component along the third wind axis

, as an explicit expression for the first derivative of the angle of attack (

). Differentiating this expression once with respect to time yields the explicit expression (

).

A reformulated version of the second equation of the wind-referenced linear momentum equations, which is Equation (9) that represents the component along the lateral wind axis

, is provided below as an explicit expression for the first derivative of the sideslip angle (

). Differentiating this expression once with respect to time yields the explicit expression (

).

Although either of the two previous expressions for ( and ) has a singularity at ( = 0), this condition is not realistic for a fixed-wing airplane, as it implies that the airplane is stagnant relative to the ambient air (a hovering condition).

In the explicit expressions ( and ), the first derivative of the trust () appears on the right-hand side. In order to construct a symbolic explicit expression for (), Equation (74), as an explicit expression for (), is differentiated once with respect to time. The resultant expression is very elaborate and thus is not shown, but is denoted by the placeholder symbol ().

The discussions given before in subsection 3.2 and subsection 3.8 regarding the interpretation of the angle of attack () appearing in the general flight mechanics modeling, and the relation of this angle to the conventional angle of attack () and its equilibrium value () remain the same here for the InvSim mode of flight mechanics modeling.

5.7. InvSim Inertial Velocity

Going back to the needed explicit expressions ( and ) discussed earlier in subsection 5.5; the explicit expression () has the second time derivative of the azimuth flight path angle () in its right-hand side, while the right-hand side of the explicit expression () requires the second time derivative of both of the azimuth flight path angle () and the elevation flight path angle ().

The original expression for the inertial Cartesian velocity components (

) in subsection 3.4 can be mathematically altered to give two explicit expressions for these flight path angles (

and

). We recall below the original equations for the ground-referenced velocity components.

From these equations, the velocity of the airplane’s center of gravity can be expressed in terms of the spherical coordinates (

) as

The quantity () is the projected velocity component in the horizon plane (), and it is equivalent to () according to Equations (26 and 27); and it can be shown to be also equivalent to () given that () and ().

It should also be noted that the derivatives of the inertial Cartesian coordinates () are computed either numerically using approximated finite different expressions that are applied to the input discrete series of the inertial Cartesian coordinates (), or through evaluating symbolic expressions if these coordinates are described as symbolic differentiable functions. In either case, these derivatives () are assumed to eventually become available as series of discrete values covering the entire maneuver duration.

The numerical values of the second derivatives of the inertial Cartesian coordinates () are needed to evaluate the symbolic expression for the first derivatives of the two flight angles ( and ), while the numerical values of the third derivatives of these inertial Cartesian coordinates () are needed to evaluate the symbolic expression for the second derivatives of the two flight angles ( and ). Again, the values of () and () can be obtained through numerical differentiation or symbolic differentiation (followed by numerical substitution at each of the times stations along the maneuver trajectory), depending on how the input coordinates () for the maneuver trajectory are described.

Similarly, expressions for the first and second derivatives of the velocity magnitude ( and ) can be developed in terms of the inertial accelerations () and inertial jerks (). Alternatively, one may compute the discrete values of () from the numerical values of () by using the above Equations (77-79), and then applying finite difference formulas to estimate the values of the first derivatives () and the second time derivatives ().

We list below standard finite difference method (FDM) formulas to approximate a first derivative (

), a second derivative (

), and a third derivative (

), of a generic time-dependent function

, if its values at uniformly-spaced time stations having a fixed time step (

) are known [336,337,338,339]. These formulas are second-order-accurate, which means that the discretization error decays at a rate that is related to the decay rate of the time step squared. For each derivative order (one, two, or three); three types of the finite difference formulas are provided, namely (1) forward difference (FD), (2) central difference (CD), and (3) backward difference (BD). At the initial time station (assigned a time station index

= 1), forward difference should be used, since no past “backward” values are available. At the final time station (assigned a time station index

) backward difference should be used, since no future “forward” values are available. At other intermediate time stations (having time station index values of

for

and

; but

for

), central difference is preferred because it involves less computation and it is symmetric (considering both past and future data). The finite difference formulas are listed in

Table 7. In this table, the subscript indices (such as “

”, “

”, and “

”) refer to the time position relative to the generic time station (

).

With this, the numerical values of the following 12 quantities should be known at each time station before the main InvSim flight mechanics simulation starts:

We provide below symbolic expressions for the first derivatives (

), while the symbolic expressions for the second derivatives (

) are much more detailed and thus are not provided here, but we denote them by the placeholder symbols (

), respectively.

Either of the two previous expressions for () and () has a singularity at (), which corresponds to ( = ±90° or ±π/2 rad). In a real flight setting, this means that the airplane is flying straight up or straight down with respect to the fixed ground (thus, the airplane is flying perpendicular to the horizon). This is a restriction in the present InvSim numerical algorithm, which fails in this case. Therefore, such two particular flight movements (vertical ascent, nose-up; and vertical ascent, nose-down) should be excluded although some military airplanes are capable of performing such unconventional flight situations, with their thrust exceeding their weight [340,341,342].

5.8. InvSim Three Aerodynamic Forces

In the proposed InvSim here for inverse simulation (InvSim) of flight mechanics problems, the nondimensional aerodynamic coefficients along the body axes () are used in lieu of the dimensional aerodynamic forces along the body axes (). Therefore, the explicit expressions for the aerodynamic forces presented in the original flight mechanics formulation, Equations (31-33) in subsection 3.6, are not needed for performing the InvSim computations. However, these expressions can still be used for computing and reporting these aerodynamic forces as supplementary post-processing quantities.

5.9. InvSim Air Density and Speed of Sound

The variation of the air density (), air temperature (), and speed of sound () with the altitude () as described by the International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) model and discussed earlier for the general flight mechanics formulation are independent of the mode of solving the flight mechanics problem (either forward or inverse). Rather, these are standalone relationships that serve to supply the proper air conditions at the altitude of each time station.

Therefore, this part of the InvSim algorithm is not repeated here, as it is the same as the one discussed earlier for the general flight mechanics formulation in subsection 3.9.

We clarify again that only the air density is needed in the InvSim algorithm computations, while the air temperature only facilitates computing the Mach number as a supplementary flight feature.

6. InvSim Numerical Algorithm

In this section, we describe the main stages of the numerical integration algorithm for solving the inverse simulation (InvSim) flight mechanics problem for an airplane, based on the miscellaneous equations and theoretical overview given before.

In summary, the algorithm has three main stages, namely (1) pre-processing of inputs, (2) initialization, and (3) time loop Runge-Kutta method.

6.1. Pre-Processing of Inputs

This first stage of the InvSim numerical algorithm can be further divided into the following steps:

The initial time for the trajectory is set to (

= 0). If the entire trajectory duration is (

), then the number of time stations is

where (

) is the uniform time step; and the number of time steps is (

) or (

).

The 30 constants needed for defining the airplane’s geometry and its aerodynamic/stability behavior, as well as the initial altitude (as listed in subsection 4.3), are received by the user.

-

The four main InvSim inputs are also received by the user, either as analytical (symbolic) expressions or as equally-spaced discrete values (a numerical vector) with a constant time step (). These four main inputs to the InvSim algorithm are

Using the initial altitude () and the values of () into Equation (1), all numerical values of the altitude () are obtained.

Using the obtained values of the altitude () into either Equation (50) or Equation (54), all numerical values of the air density () are obtained.

Optionally, all numerical values of the speed of sound can be also computed as we explained in subsection 3.9.

- 6.

Using either analytical (symbolic) differentiation (if the bank angle is provided as a functional form) or second-order finite difference formulas (if the bank angle is provided as a vector of discrete values), all numerical values of the first derivative of the bank angle () and the second derivative of the bank angle () are obtained.

- 7.

Using either analytical (symbolic) differentiation (if the inertial coordinates are provided as functional forms) or second-order finite difference formulas (if the inertial coordinates are provided as vectors of discrete values); all numerical values of their first derivative (), second derivative (), and third derivative () are obtained.

- 8.

Using Equation (77), all numerical values of the velocity magnitude () are obtained.

- 9.

Using the obtained values of the air density () and the obtained values of the airplane speed () into Equation (11), all numerical values of the dynamic pressure () are obtained.

- 10.

Using Equation (78), all numerical values of the azimuth flight path angle () are obtained.

- 11.

Using Equation (79), all numerical values of the elevation flight path angle () are obtained.

- 12.

Using second-order finite difference formulas discussed in subsection 5.7, all numerical values of the first derivative () are obtained.

Alternatively, Equation (80) can be used.

- 13.

Using the Equation (81), all numerical values of the first derivative () are obtained.

- 14.

Using the Equation (82), all numerical values of the first derivative () are obtained.

- 15.

Using second-order finite difference formulas discussed in subsection 5.7, all numerical values of the second derivative () are obtained.

Alternatively, the explicit expression () discussed in subsection 5.7, can be used.

- 16.

Using the explicit expression () discussed in subsection 5.7, all numerical values of the second derivative () are obtained.

- 17.

Using the explicit expression () discussed in subsection 5.7, all numerical values of the second derivative () are obtained.

At the end of this first stage of the InvSim numerical algorithm, the following 27 vectors (series of numerical values) become available, covering all the () times stations of the flight maneuver:

(the four InvSim inputs)

Optionally, 4 more pre-processing vectors can be computed entirely from the user’s provided data, before solving for other flight variables; although these 4 quantities are not core elements in the InvSim algorithm, thus the simulation can be completed without knowing these quantities. These 4 optional pre-processing vectors are

6.2. Initialization

The initial conditions correspond to the first time station, with the index ( = 1). The following initial conditions are implemented:

- 18.

The initial angle of attack () and the initial sideslip angle () are set to zero values, in alignment with an equilibrium condition.

- 19.

The above mention initial zero values for ( and ) dictate that the initial values of the two unspecified Euler angles ( and ) take in the initial values of the known spherical flight path angles ( and ), respectively. Therefore, and . These initial conditions are implied by Equation (29) and Equation (30), respectively, as was discussed in subsection 3.5.

- 20.

The initial thrust force () is computed using Equation (74).

- 21.

The initial angle of attack rate () and the initial sideslip angle rate () are set to zero values.

- 22.

The explicit expressions ( and ) discussed in subsection 5.5 imply that the initial Euler yaw rate () and the initial Euler pitch rate (), respectively, have zero values.

- 23.

Equations (2, 3, 4) imply that the initial body-referenced angular velocities () respectively, have zero values.

- 24.

Equations (71, 72, 73) imply that the initial body-referenced angular velocities (), respectively, have zero values.

- 25.

The initial control surface deflection angles () are computed using Equations (61, 62, 63), respectively.

6.3. Time Loop Runge-Kutta Method

This third stage of the InvSim numerical algorithm is the main stage, where the classical explicit fourth-order Runge-Kutta (RK4) four-step integration method is used to numerically estimate the evolution of eight flight variables through a system of nonlinear coupled ordinary differential equations (ODE) [343,344,345,346,347]. These eight variables are:

In this subsection, we describe how these eight variables are advanced in discrete time through the proposed InvSim numerical algorithm from an arbitrary time station (discrete time index ) with known values for these eight variables to the next time station (discrete time index ) with unknown values for these eight variables.

In the beginning, it might be useful to make a brief description of the classical fourth-order Runge-Kutta method for a generic nonlinear scalar ordinary differential equation (ODE) of the form

with a known starting condition denoted as

.

The procedure of numerically integrating this exemplar ODE in order to find the estimated value

is as follows:

where the superscript asterisk in (

,

, and

) refers to a temporary (intermediate) value.

Considering the proposed InvSim algorithm presented here, the above procedure is to be applied four times per time step as follows:

- 26.

Either of the four intermediate derivatives for the thrust () is computed using the explicit expression () discussed in subsection 5.6.

- 27.

Using the explicit expressions (

and

) along with Equations (75 and 76) discussed in subsection 5.6, the intermediate derivatives for the angle of attack (

) and the sideslip angle (

) are computed, respectively as

- 28.

Using the explicit expressions (

and

) along with the explicit expressions (

and

) discussed in subsection 5.5, the intermediate derivatives (

) and (

) are computed as

- 29.

Either of the four intermediate derivatives of the body-referenced roll rate () is computed using Equation (71). Similarly, either of the four intermediate derivatives of the body-referenced pitch rate () is computed using Equation (72), and either of the four intermediate derivatives of the body-referenced yaw rate () is computed using Equation (73).

- 30.

The computed 32 temporary derivatives (8 temporary derivatives for 8 variables are computed in each of the 4 steps of the RK4 procedure) are used to update the 8 variables of the RK4 procedure at time station (

), as follows:

With this update, one of the four output flight controls (namely the thrust,

) becomes known at the new time station (

). We need to obtain the remaining three output flight controls (the three moving surface deflection angles;

,

,

). This is done in the remaining part of the InvSim numerical algorithm as explained next.

- 31.

The new values (at time station ) of the 8 updated variables through the RK4 procedure are used to evaluate several derivative expressions, ending with the body-referenced angular acceleration () at the new time station () using Equations (71, 72, 73), respectively.

- 32.

The obtained new body-referenced angular accelerations () are used in the explicit algebraic expressions () to compute the auxiliary moments () at the new time station ().

- 33.

The obtained new auxiliary moments () are used in Equations (68, 69, 70), respectively, to find the corresponding total body-referenced moments () at the new time station ().

- 34.

The obtained new total body-referenced moments () are used in Equations (64, 65, 66), respectively, to find the corresponding nondimensional moment coefficients () at the new time station ().

- 35.

Finally, the obtained new nondimensional moment coefficient () is used into Equation (61) to find the necessary deflection angle for the elevators () at the new time station (). Similarly, the obtained new nondimensional moment coefficients () are used in Equations (62, 63), respectively, to find the necessary deflection angles for the ailerons () and for the rudder () at the new time station ().

If this is not the last time station (), the above 10 computational actions are repeated to find the four necessary flight control variables () at the next time station.

7. InvSim Example for Mirage III

Although the main contribution of this work is the detailed presentation of the numerical inverse simulation (InvSim) flight mechanics algorithm, where the required flight controls corresponding to a desired flight trajectory for a given fixed-wing airplane may be computed; it is a valuable addition to this study to provide an example case in which the proposed InvSim algorithm is completely applied. This demonstrative example is performed in this section for a set of airplane data representing the family of military fighters called “Mirage III”.

7.1. About Mirage III

Mirage III is a family of military all-weather aircraft, capable of interception at supersonic speeds and capable of taking off using compact runways. Mirage III airplanes are produced by the French aerospace company Dassault Aviation, which is a major partner of the French national defense [348,349,350,351,352]. The Mirage III family is characterized by a delta wing (shaped as a triangle), and a single powerful jet engine able to deliver a thrust force of about 80 kN (80,000 N).

Although there are different models of Mirage III, we here use the following set of geometric and performance parameters listed in

Table 8, which are considered to be an archetype representation. Due to the delta-shaped wing, the characteristic longitudinal length (

) and the characteristic lateral length (

) are assigned equal values.

In addition, we select an initial altitude of = 0. This means that the trajectory starts from a point located at the mean sea level.

7.2. Proposed Test Maneuver

The flight maneuver we use here to verify the applicability of the proposed inverse simulation (InvSim) numerical algorithm is a simple one, being a horizontal north-wise straight flight at a constant altitude of 5,000 m and with a constant flight speed of 150 m/s while performing a continuous double-roll rotation with a non-linear angular profile constituting of a two-harmonic function. This simple maneuver has several advantages, making it a favored test case here, as well as for others who may want to develop this InvSim solver and test its implementation. With this proposed test maneuver, it is easier to inspect the computational procedure of various flight variables than with a complex maneuver. In this proposed maneuver, different vector quantities reduce practically to a scalar value (a single value repeated over all time stations), and various derivatives become zero throughout the entire maneuver. In addition, all the main InvSim input profiles can be specified through concise analytical functions, rather than as extensive numerical lists.

The four main inputs to the InvSim flight mechanics algorithm in the test maneuver are

where (

) are in meters, and (

) is in radians.

Taking the derivatives of the bank angle (

) gives the following expressions for its Euler rate (

), and Euler acceleration (

):

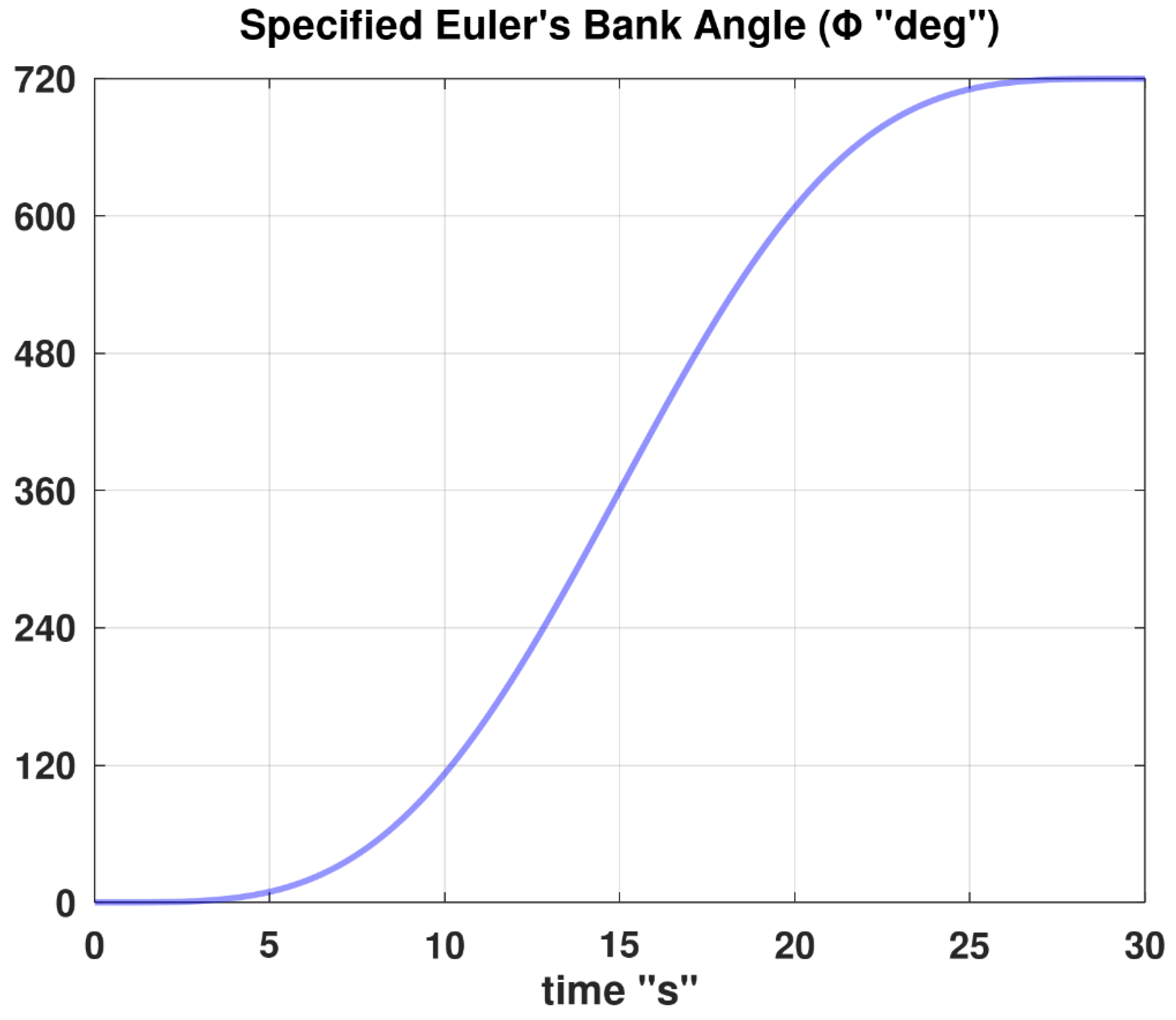

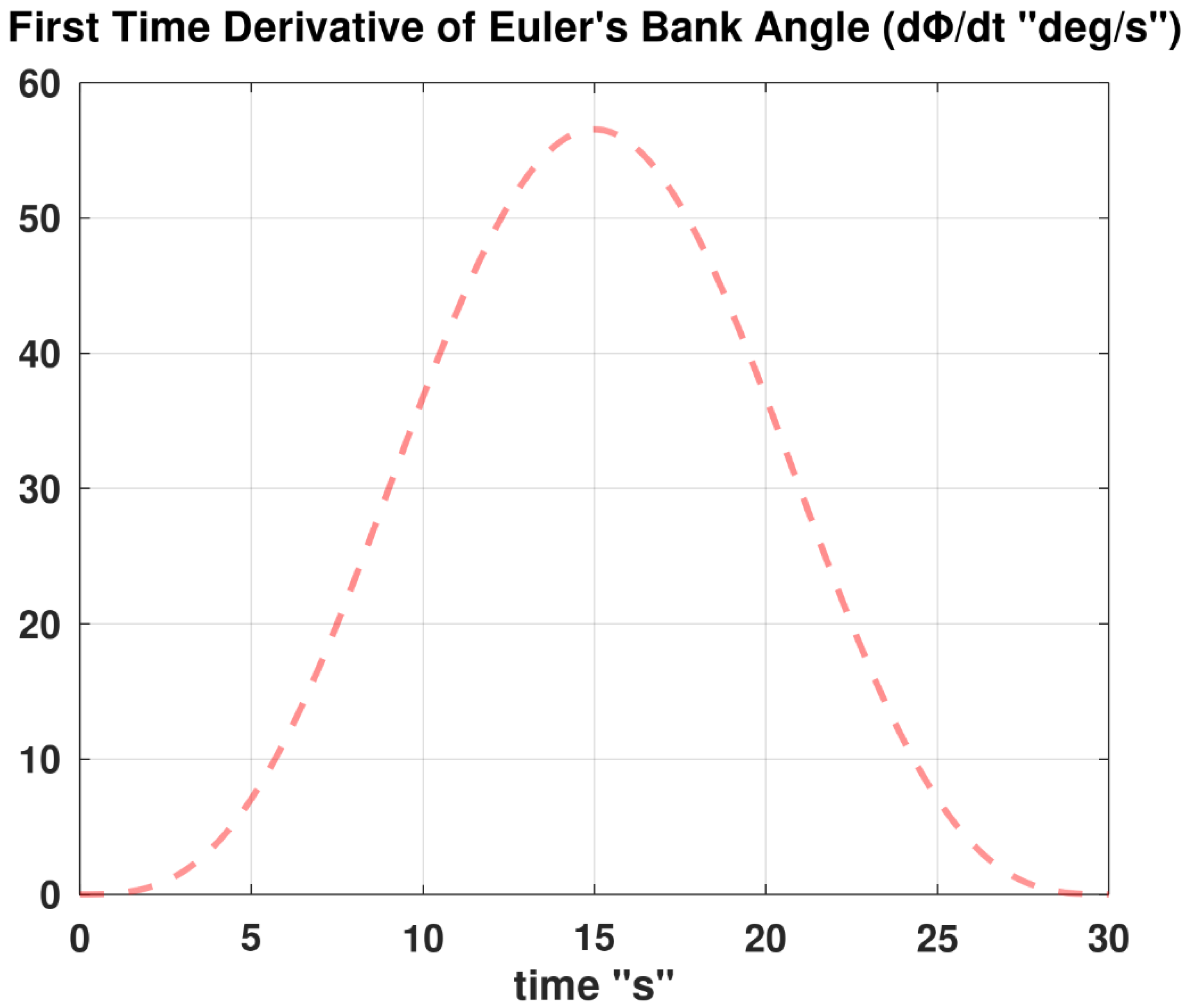

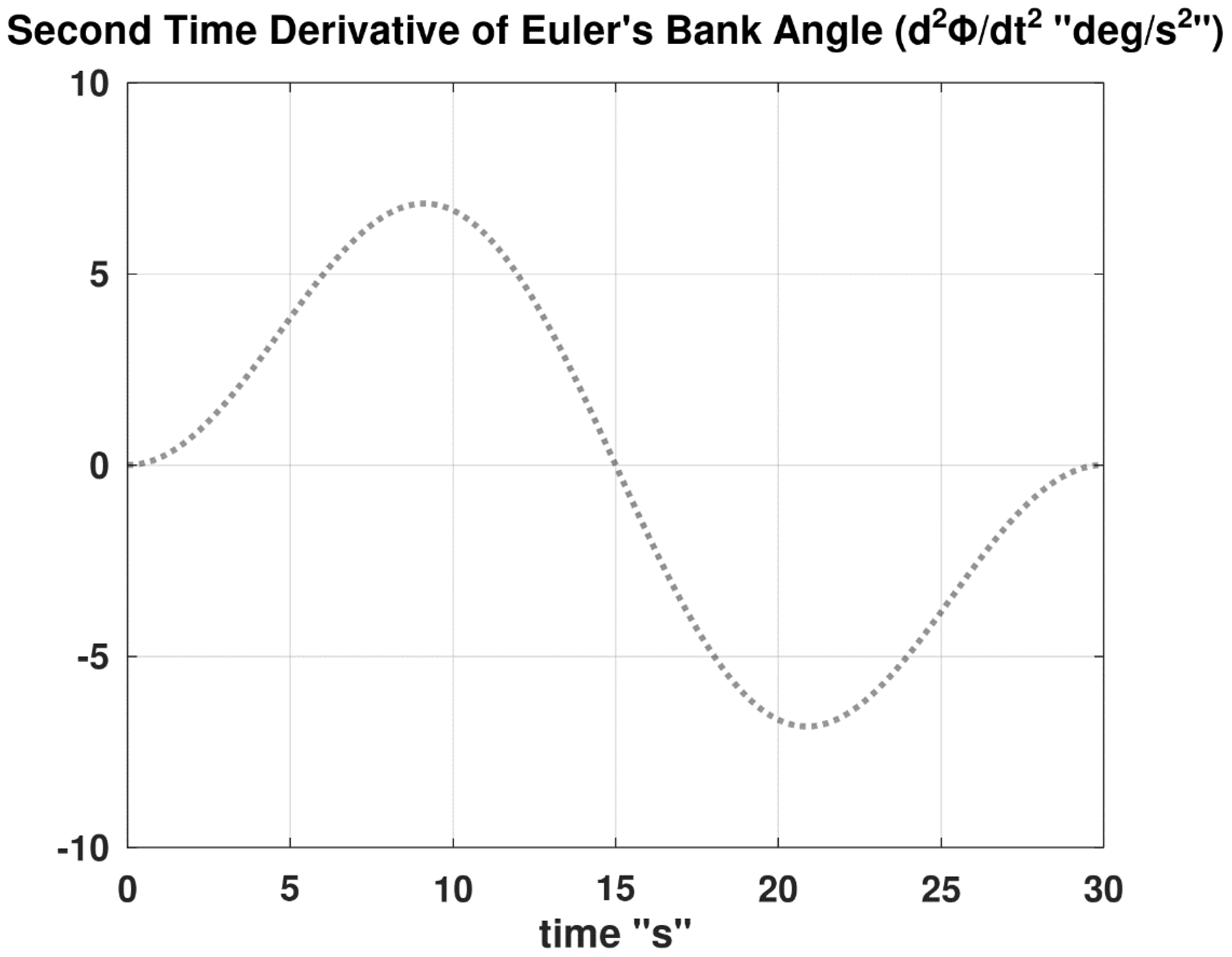

Figure 9,

Figure 10, and

Figure 11 illustrate the temporal profile of the bank angle or roll angle (

), its first derivative (

), and its second derivative (

); respectively, during the continuous-double-roll maneuver. In these figures, the angles are expressed in degrees (through scaling by the multiplicative value

= 57.296 °/rad). The bank angle changes from 0° to 720° over a duration of 30 s. The rate (

) has a non-negative symmetric profile, peaking at the midpoint of 15 s to reach a maximum value of 56.549 °/s; while (

) has an antisymmetric profile, with a positive peak of 6.838 °/s

2 at 9.123 s and a negative peak of –6.838 °/s

2 at 20.877 s.

Table 9 lists some of the computed characteristics for the test maneuver. These characteristics aid in validating computational implementations by others because these quantities can be computed at the initial time station (

= 1,

= 0) independently of the time loop calculations. In addition, the quantitative characteristics provide useful insights into the nature of this numerical test maneuver when viewed as a real flight mission. It should be noted that due to the maneuver simplicity, these scalar quantities are actually vectors of constants (vectors representing frozen or static variables), thus all time stations have the same value of each characteristic quantity.

7.3. Inverse Simulation Results

We implemented the proposed InvSim numerical algorithm as a MATLAB/Octave computer code, and we applied it here using GNU Octave version 6.1.0. The algorithm does not require specialized toolboxes. The time step () we used is 0.001 s (thus, there is a total of = 30,001 time stations). We tried different values for the time step, and we found that this selected value to be proper. With much lower values (such as 0.01 s), the simulation can still be performed without instability, but minor spurious oscillations or non-smooth variations near sharp peaks may occur.

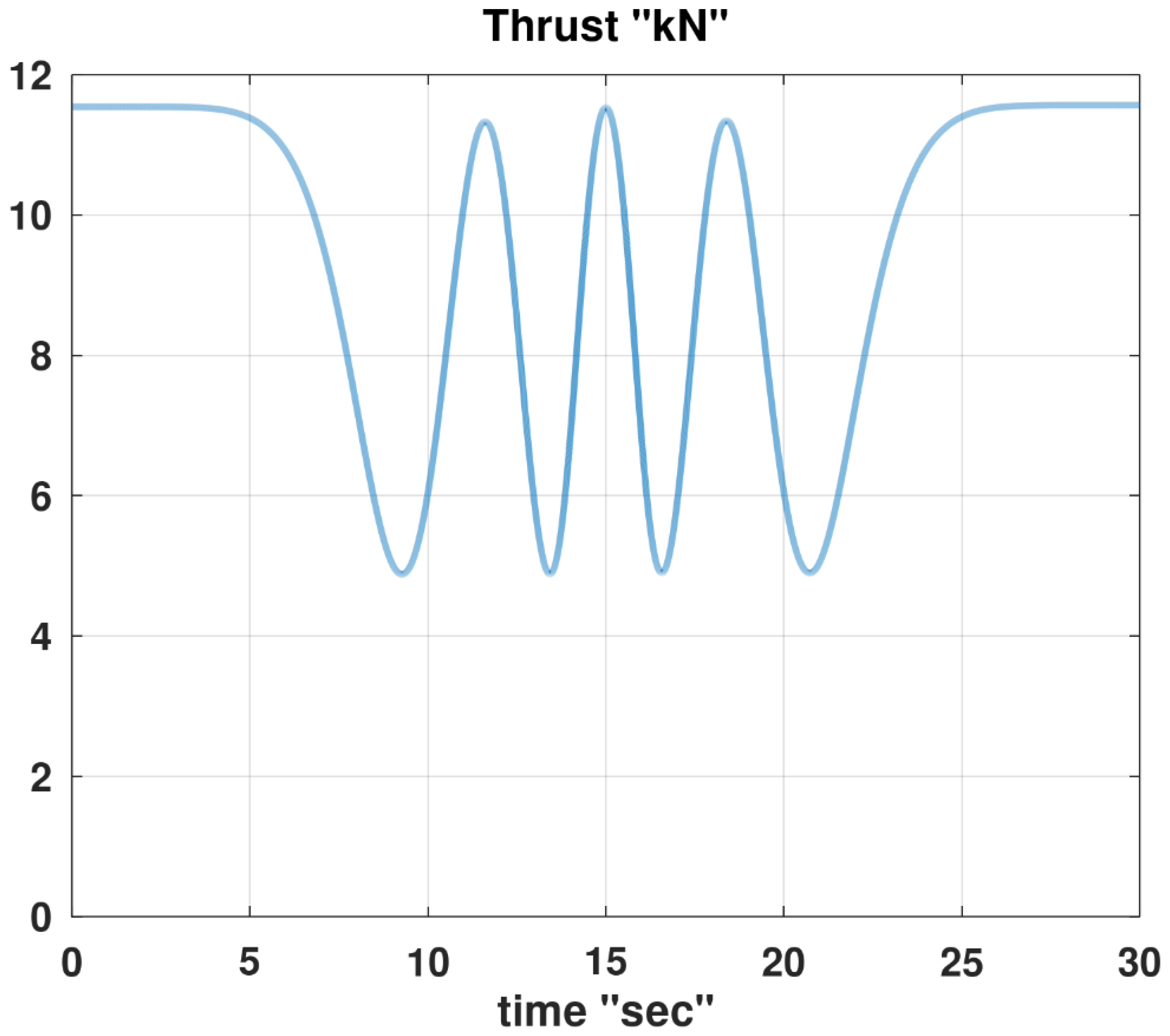

We start the results of the InvSim algorithm for the test maneuver with the four outputs, which are the flight controls.

Figure 12 shows the computed thrust force, which is one of the four flight controls. The equilibrium value is 11,543 N (11.543 kN), which changes between four minima and three maxima until the same equilibrium value is restored at the end of the maneuver. The three encountered maxima values of the trust are 11,332 N at 11.613 s; 11,535 N at 15.002 s; and 11,348 N at 18.390 s. All these peaks are less than (but close to) the equilibrium value. Knowing the global maximum thrust needed during a prospective maneuver is particularly important because it helps in deciding whether that target maneuver is achievable or not with the available maximum thrust for the airplane of concern. The four thrust minima are nearly 4,900 N. Knowing the global minimum thrust needed during a maneuver is also important, because negative values (reversed backward thrust) typically imply that the maneuver is not achievable.

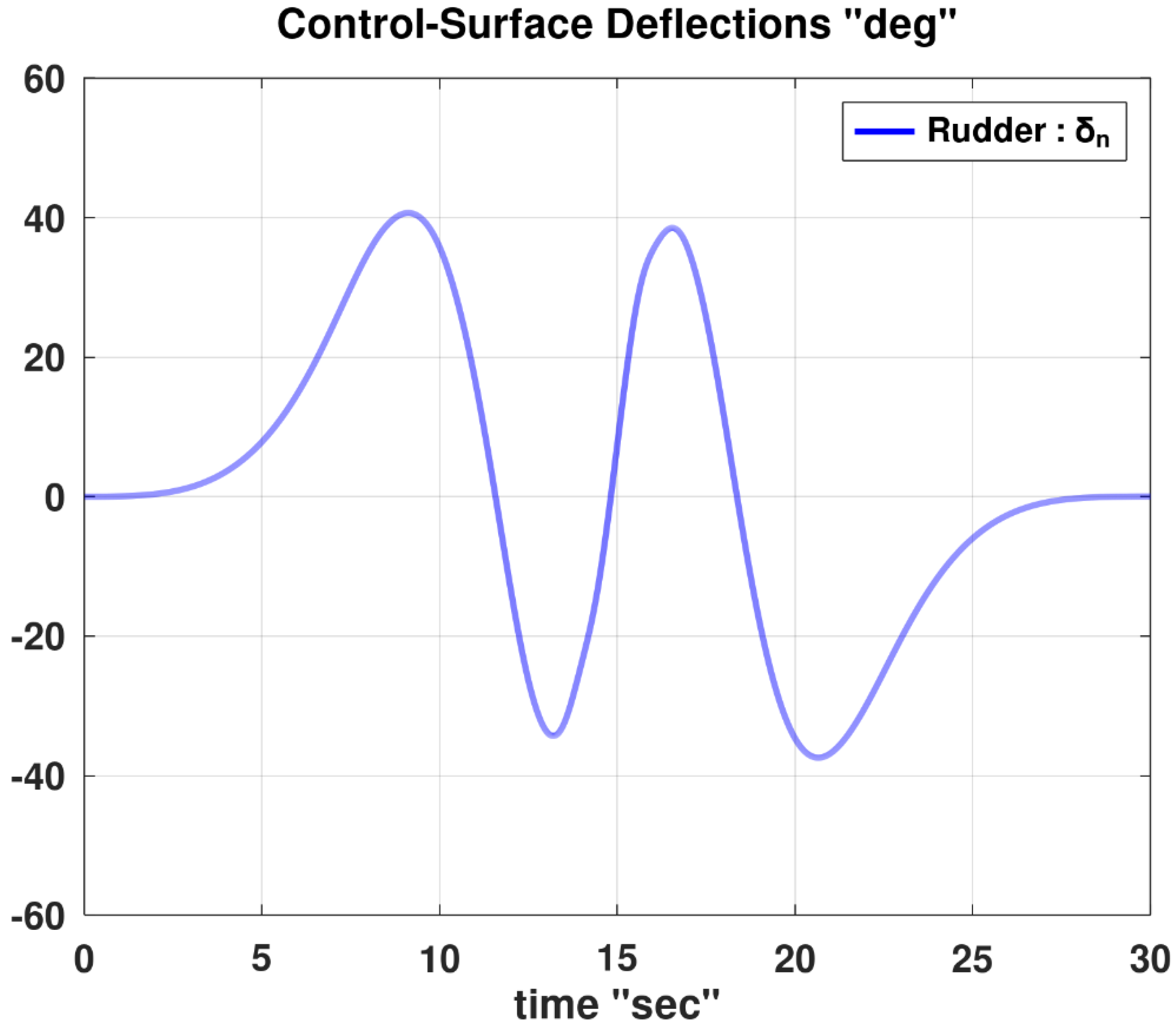

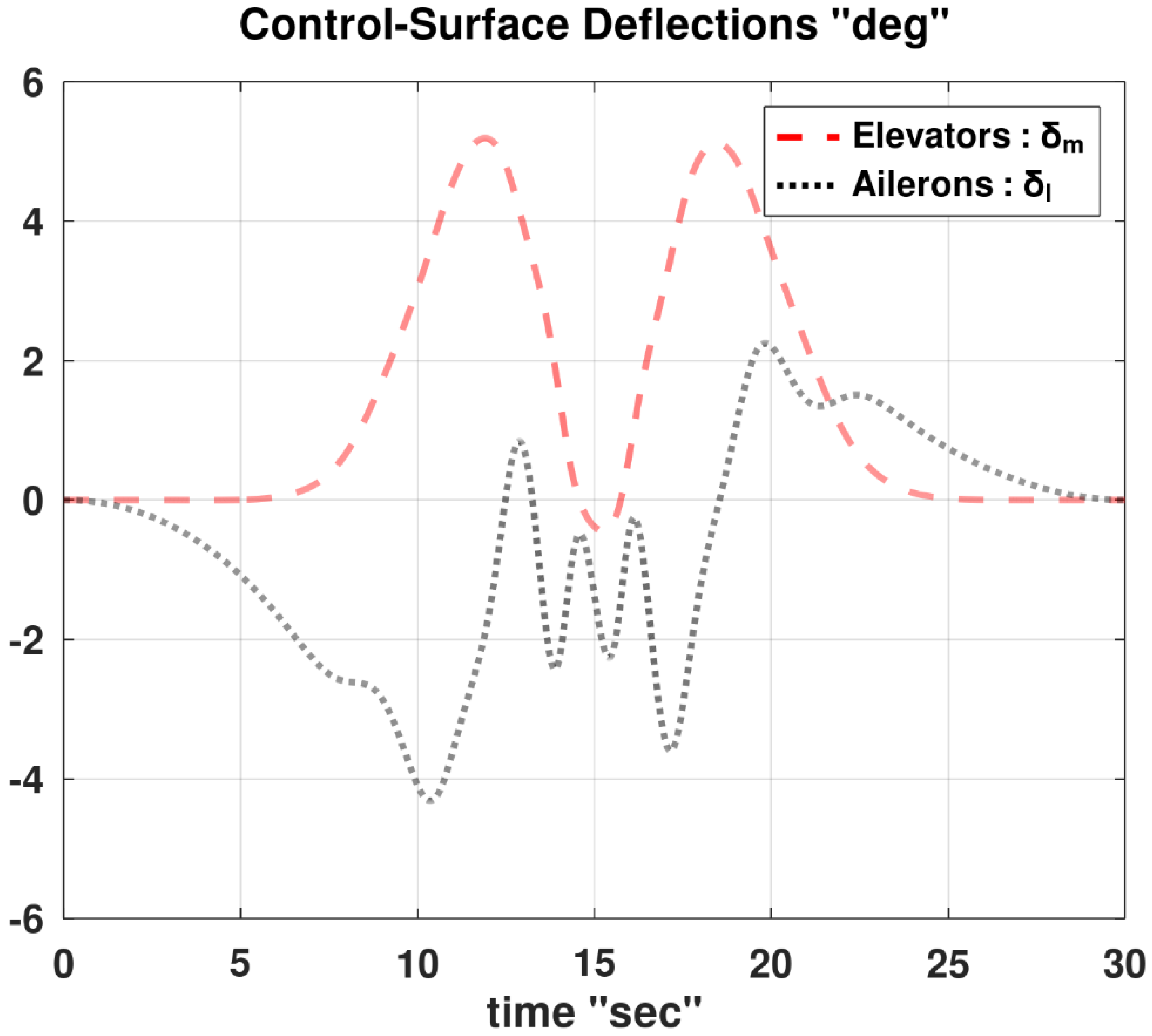

Figure 13 shows the necessary variations in the rudder control surface deflection angle (

) during the test maneuver. The maximum absolute deflection angle here is 40.68°. This value is apparently acceptable in terms of geometric constraints; whereas deflections near or exceeding 60° may not be realistic, and thus suggest that the maneuver is too challenging to be accomplished with the present configuration of the airplane [353,354,355]. The necessary deflection angles of the elevators (

) and the ailerons (

) are much smaller than those demanded by the rudder, as shown in

Figure 14. The elevators deflection angle is positive most of the time, with negative values encountered for a brief period near the middle of the maneuver. None of the rudder deflection angle and the ailerons deflection angle are exactly symmetric about the horizontal zero line. The rudder deflection angle is positively biased, with a positive mean value of 1.294°; while the ailerons deflection angle is negatively biased, with a negative mean value of –0.624°.

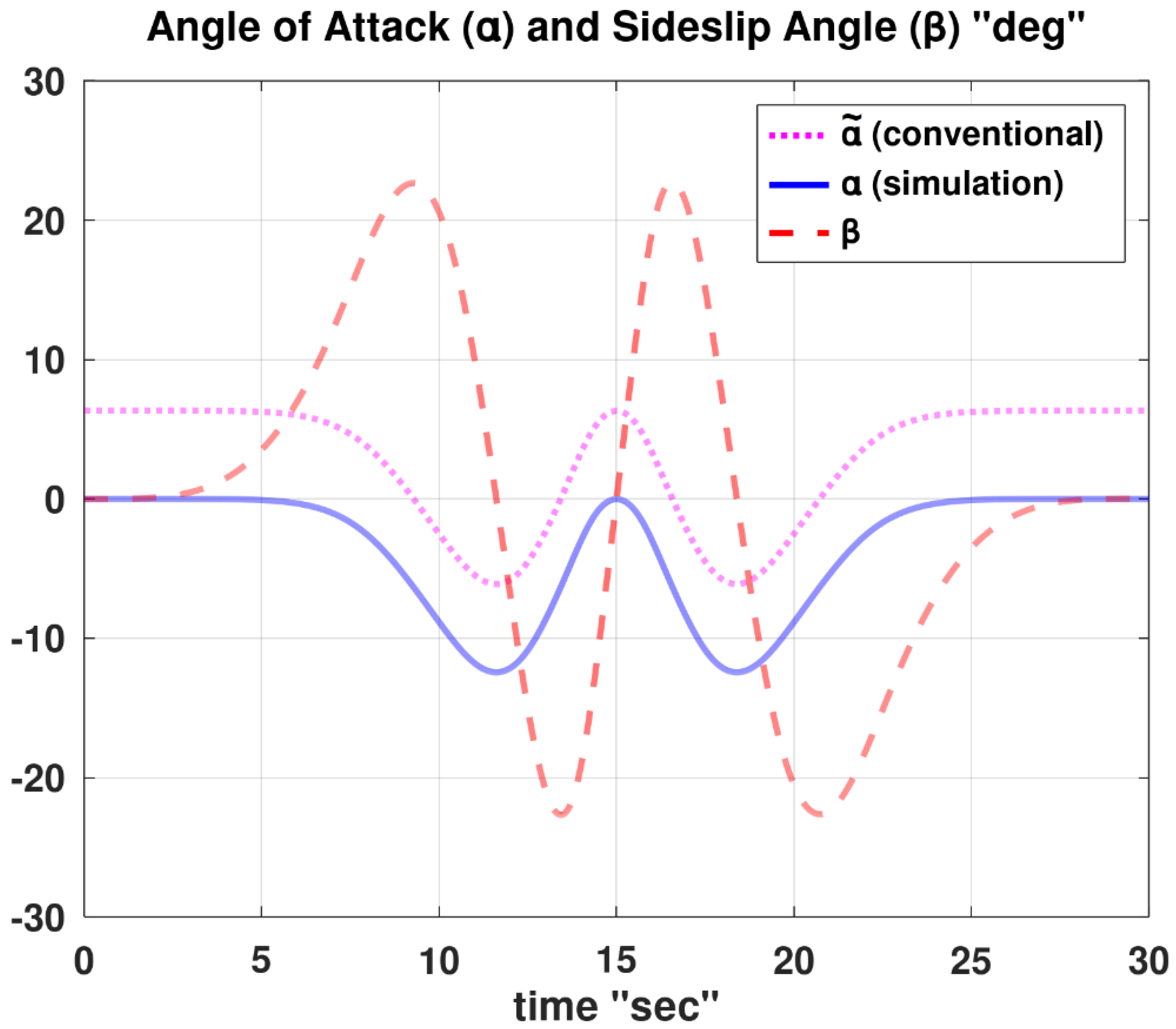

Figure 15 provides additional information about the inversely-simulated test maneuver, through displaying the variations in the angle of attack (and its conventional counterpart) and the sideslip angle. A strong correlation can be qualitatively observed between the sideslip angle and the rudder deflection angle. This can be explained by noting that a positive sideslip angle (while the thrust vector is collinear with the longitudinal body axis) leads to a drift in the airplane’s travel path toward the left (the port side) due to a continuously applied port-wise force component of the thrust, and therefore the path becomes curved. To counteract this and maintain a straight flight path, as in the target test maneuver here, a restoring moment needs to be induced through a positive rudder deflection angle (the ridder tilts toward the port side). The profile of the conventional angle of attack (

) is just a shifted version of the simulation-reported angle of attack (

); with the difference being the frozen equilibrium conventional angle of attack (

), which is 6.3322° (0.110518 rad) in the current test maneuver. During the maneuver, the conventional angle of attack (

) is bound between –6.1129° and 6.3322°; which is a narrow range around the zero value, thus validating the assumption of non-stall.

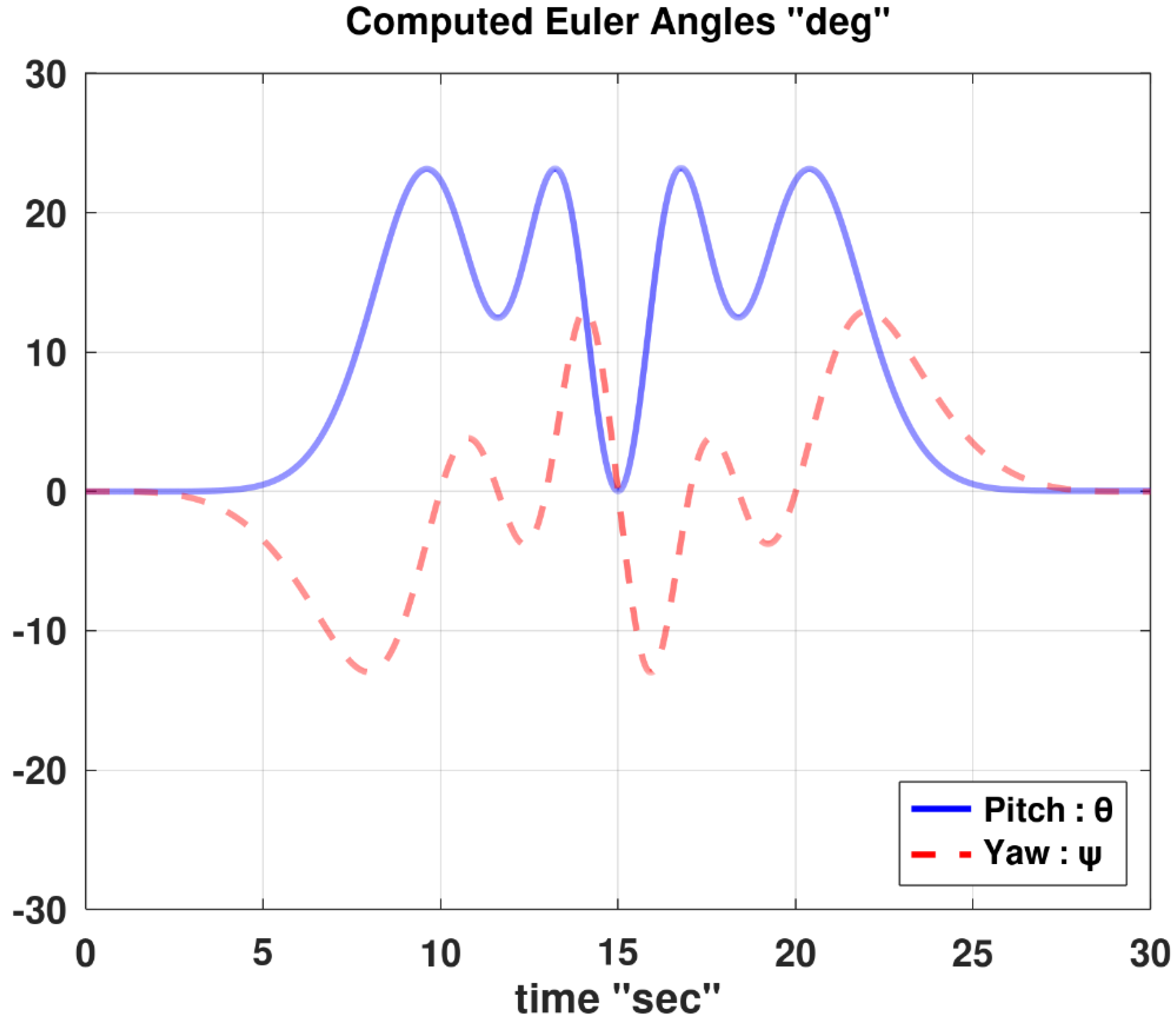

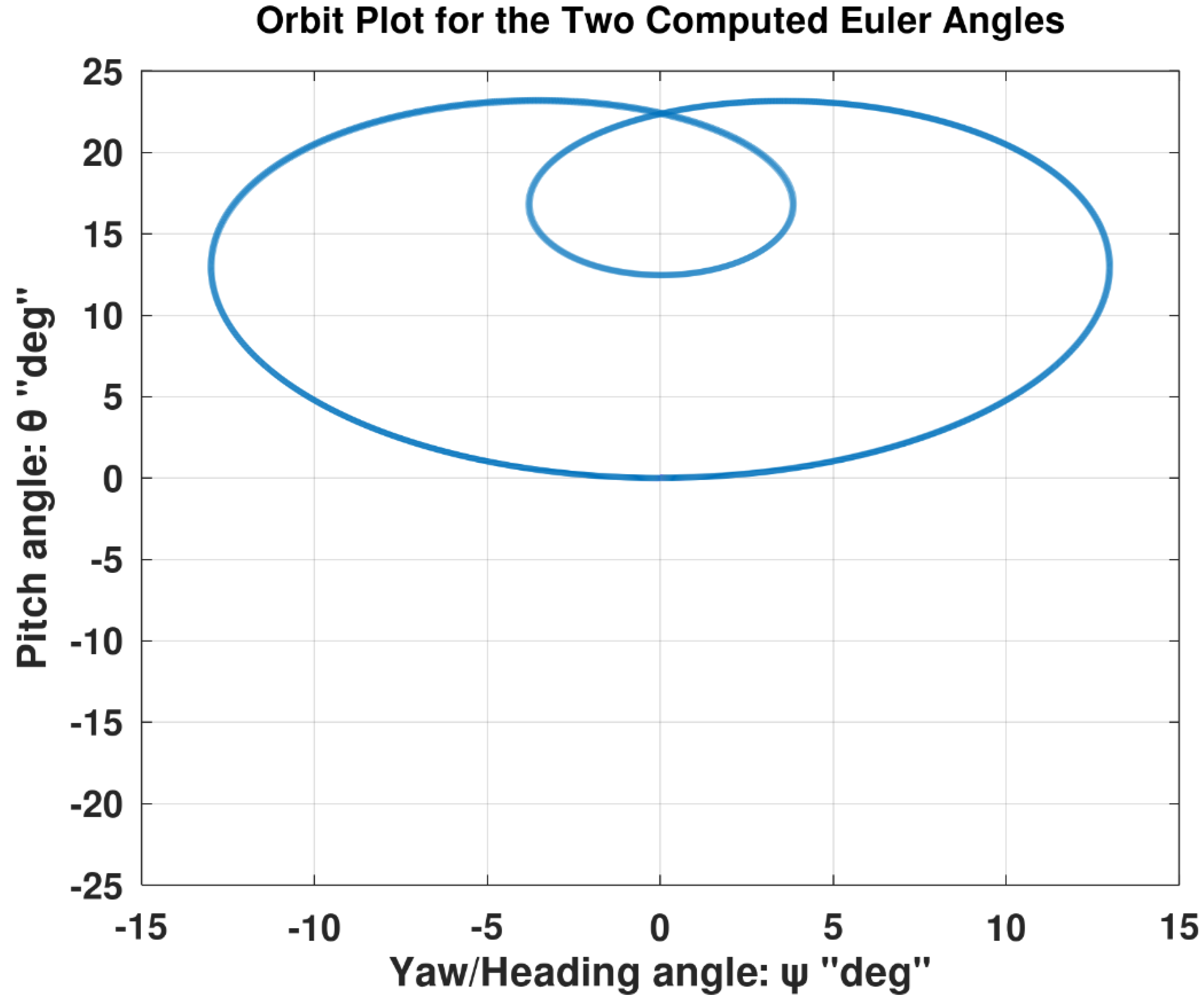

Figure 16 provides the profiles of the two Euler angles that were not specified as input constraints, but were computed by the InvSim algorithm, and these angles are the pitch angle and the yaw (or heading) angle.

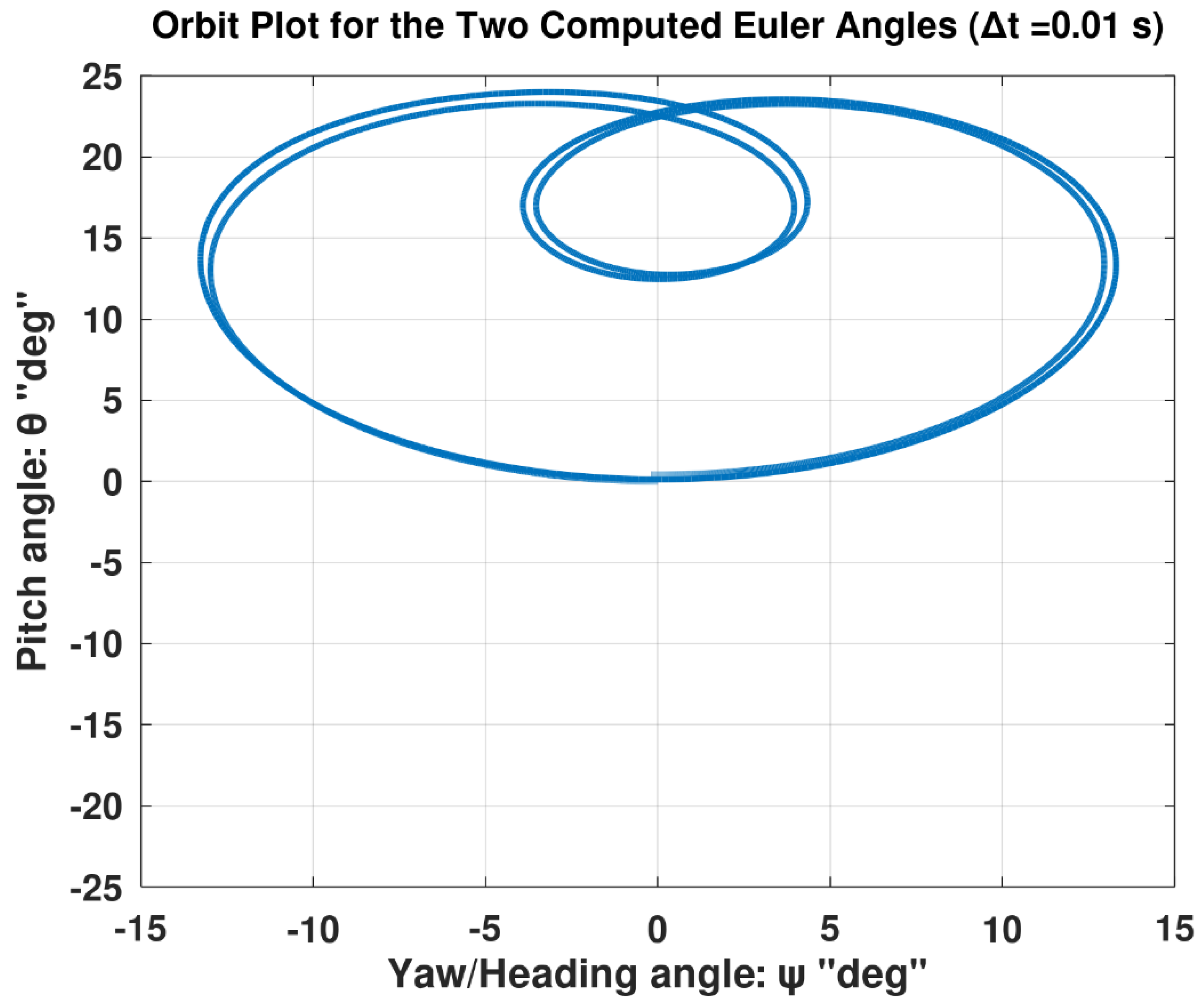

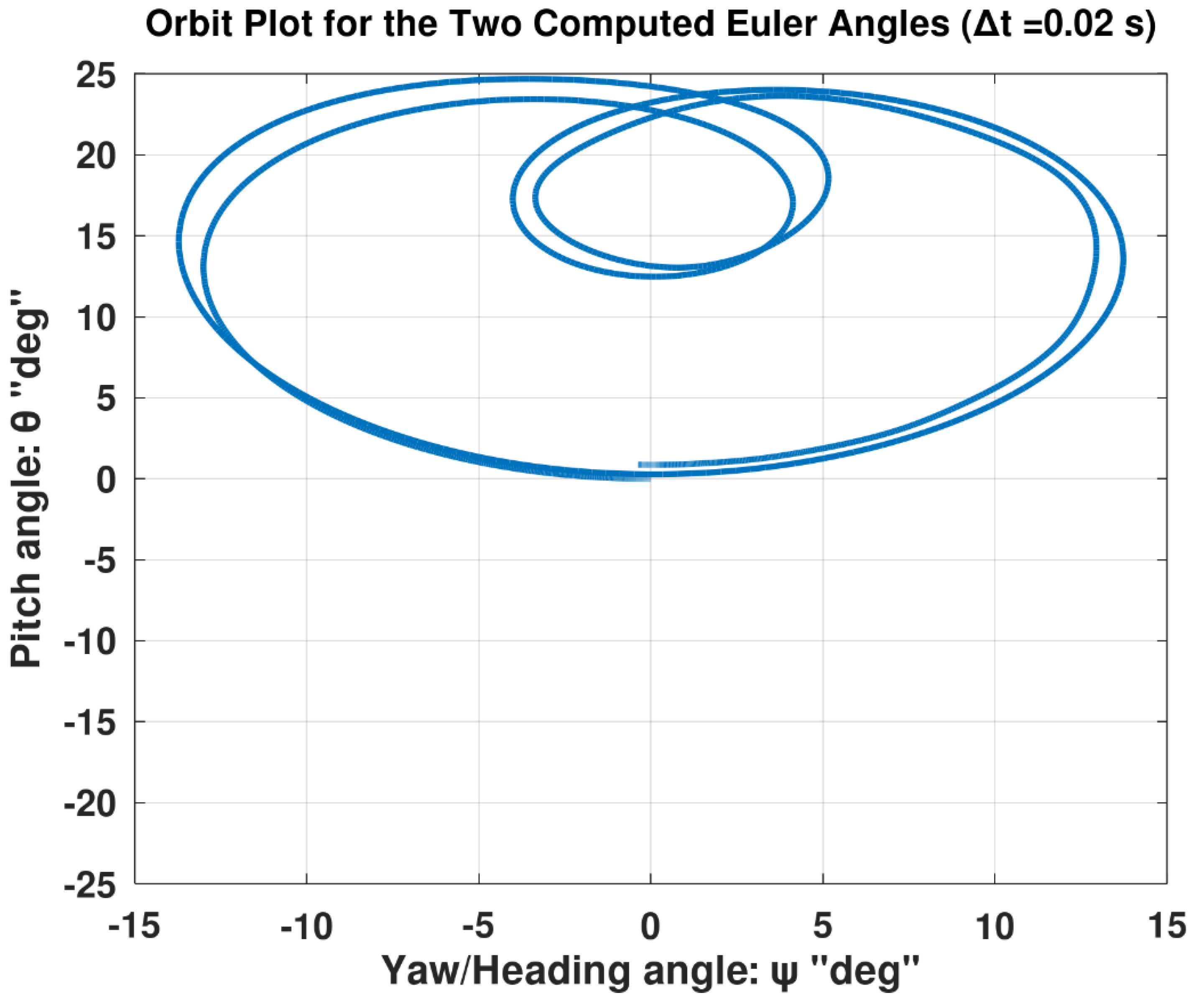

Figure 17 visualizes the variation of these two airplane attitude angles, but as an orbit plot, where the pitch angle is plotted against the yaw angle with the time being a parametric variable. This particular figure allows judging the convergence of the simulation as the time step is successively refined. At a satisfactorily small time step (like the one used here, 0.001 s), the orbit plot shows a smooth continuous closed double-loop resembling a cardioid. In fact, this plot shows two double-loop curves on top of each other, each one is formed due to one rolling revolution by the airplane during one-half of the total maneuver duration. At an improper coarser time step (such as 0.01 s as shown in

Figure 18, and 0.02 s as shown in

Figure 19), these two curves become detached so they can be visually differentiated. This means that the profiles of these two Euler angles during the first rolling revolution deviate from their profiles during the second rolling revolution, due to pronounced numerical errors.

8. Conclusions

In the current study, a numerical algorithm for solving the six-degree-of-freedom inverse simulation (InvSim) flight mechanics problem for an arbitrary fixed-wing airplane was described in detail, starting from the governing equations of motion and elementary geometric relations, and including a submodel for estimating properties of atmospheric air, and steps followed in deriving the underlying system of 35 differential-algebraic equations in 39 variables, with 30 constant parameters.

The algorithm utilizes the four-step Runge-Kutta method, along with finite difference formulas. By specifying the aimed three rectangular coordinates of a trajectory and the aimed profile for the bank angle during a maneuver, the algorithm computes how the four flight control variables (the thrust force; and the three deflection angles of movable control surfaces – rudder, elevators, and ailerons) should change with time to achieve this target maneuver.

The algorithm was demonstrated through a complete test case of a constant-speed two-harmonic double-roll level flight for an airplane resembling the Mirage III French fighters. The settings and results of the test problem were discussed, and the effect of the time step size was illustrated.

The work presented here may be extended to more complex operations, for example through implementing real-time feedback control to compensate for external disturbances (such as gusts), or through accommodating additional geometric features (such as wing flaps).

Funding

Not applicable (this research received no funding).

Declaration of Competing Interests Statement