1. Introduction

The ability of living organisms to move through their environment is fundamental to survival – a process scientifically referred to as locomotion. In humans, walking represents the primary and most natural form of locomotion. It is a highly coordinated motor act that allows the body to navigate physical space. Early humans depended on this function to gather resources and transport them to favorable living environments [

1]. Later studies established that upright posture and bipedal locomotion evolved primarily to optimize energy efficiency during movement. Walking is considered automated motor behavior, characterized by economical muscle activation patterns and efficient mechanical movement. This efficiency is largely supported by the ventral inertial momentum of the body’s center of mass (COM) [

2].

In recent years, the analysis of human gait has garnered significant scientific attention. Research in this domain aims to provide quantitative and objective measurements of gait parameters, with applications spanning sports science, rehabilitation medicine, geriatrics, and even forensic identification. From a kinesiological standpoint, gait is defined as the translational displacement of the body through the environment, achieved via coordinated rotational movements of the joints [

3]. The entire musculoskeletal system is engaged, with the lower limbs performing the majority of the motor activity [

4]. Notably, human gait is highly individualized – often referred to as a biomechanical “fingerprint.” Gait abnormalities are most frequently observed in individuals with neurological disorders affecting the central or peripheral motor neurons. These impairments disrupt muscle tone, balance, proprioception, and coordination, and manifest in characteristic ways across different pathologies. For instance, post-stroke hemiparesis often presents with a Wernicke-Mann gait; multiple sclerosis is associated with spastic gait; and Parkinson’s disease leads to the hallmark shuffling, festinating gait. Spastic diplegic gait is commonly seen in cerebral palsy (Morbus Little), while spinal cord injuries result in paraplegic gait patterns. Peripheral nerve damage can produce a flaccid or steppage gait. When the cerebellum or vestibular system is affected – as in tumors, inner ear disorders, or cerebellar degeneration – ataxic gait patterns emerge. In hemiataxia, where only one cerebellar hemisphere is impaired, patients may veer toward the affected side. A distinctive example is the spastic-ataxic gait in multiple sclerosis, indicating combined pyramidal and cerebellar involvement. These patients often exhibit stiff, slow movements with extended lower limbs, and many eventually lose ambulatory function. Tabetic gait, caused by neurosyphilis or dorsal column dysfunction, is marked by a loss of proprioception and awareness of limb positioning. Among ataxic patterns, the so-called staggering gait resembles that of an intoxicated individual, with exaggerated lateral deviations and corrective swaying. Astasia-abasia, seen in frontal lobe lesions, features a paradoxical inability to stand or walk despite intact supine motor function. Psychogenic disorders can result in hysterical gait, where patients simulate impairments in the absence of actual deficits. Parkinsonian gait is notable for static tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, reduced arm swing, and forward-leaning posture. Affected individuals move with short, shuffling steps, often propelled by inertia, and are at increased risk of falling. Traumatic injuries of the lower extremities also significantly compromise gait. These include fractures of the femur, knee, tibia, and ankle; ligamentous injuries requiring reconstructive surgery; and joint replacements due to osteoarthritis. In addition, systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and certain cardiovascular or respiratory conditions can reduce functional independence. Age-related degenerative changes also contribute to gait decline in the elderly, representing a substantial portion of the population with locomotor limitations. Accurate and objective analysis of gait parameters is essential for early diagnosis, monitoring of disease progression, prevention of complications, and the development of individualized treatment plans [

5].

In clinical and research contexts, gait analysis methods are broadly categorized into traditional and modern techniques. Traditional gait assessment relies on observational analysis. Clinicians evaluate a patient’s gait through visual inspection, ideally without the patient’s awareness, to infer the underlying cause, whether neurological or orthopedic. While practical and widely used, this approach is inherently semi-subjective. In contrast, modern technologies have enabled more precise and objective measurement of gait parameters [

6].

Contemporary gait analysis devices fall into three main categories: non-wearable sensor (NWS) systems, wearable sensor (WS) systems, and hybrid systems that combine elements of both. Non-wearable sensor systems are designed for use in controlled laboratory environments, where fixed sensors collect data as subjects walk along predefined paths [

7]. These systems are divided into two main types: image-processing (IP) systems and floor-sensor (FS) systems. IP systems employ digital or analog cameras, often using infrared, laser range scanning (LRS) or time-of-flight (ToF) technologies to capture motion. Through techniques such as pixel filtering, thresholding, and background subtraction, they enable real-time analysis of gait via depth and distance measurements. FS systems use pressure-sensitive platforms embedded in the floor to measure ground reaction forces and pressure distribution [

6,

7]. These platforms record the magnitude and timing of forces applied during the stance phase, offering granular insight into the biomechanics of gait. Advanced FS systems feature high-resolution sensor matrices, capable of differentiating pressure across discrete regions of the foot. NWS systems are lauded for their high accuracy and reliability [

8]. However, several barriers limit their routine clinical application. These include substantial cost, complex technical setup, and spatial demands that necessitate dedicated laboratory infrastructure. Installation and calibration often require skilled technicians, increasing time and resource expenditure. Moreover, their non-portable nature renders them impractical for real-time monitoring in naturalistic or home environments – particularly for patients with mobility limitations. Despite these limitations, the detailed biomechanical data provided by NWS systems make them indispensable in high-precision research and diagnostic settings [

9].

Wearable sensor systems represent a transformative innovation in gait analysis by facilitating data collection during everyday activities [

10]. These portable devices incorporate various sensors such as accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers, goniometers, ultrasound transducers, and electromyography (EMG) sensors, strategically placed on the body (e.g., feet, shanks, hips, or lower back) to measure physiological and biomechanical parameters [

11]. Inertial measurement units (IMUs), which integrate accelerometers, gyroscopes and sometimes magnetometers are among the most widely adopted tools for gait analysis [

6,

7,

11]. Accelerometers capture linear acceleration, while gyroscopes detect angular velocity and rotational displacement [

12]. When fused, these components enable detailed 3D motion tracking, supporting the calculation of parameters such as step length, stride frequency, cadence and symmetry [

13]. Goniometers, often built on strain gauge technology, measure joint angles during dynamic movement [

14]. Ultrasound sensors can supplement spatial data acquisition by assessing parameters like step width and stride length [

15]. Surface electromyography (EMG) provides valuable insight into muscle activation patterns by detecting the electrical activity generated by muscles during contraction. EMG is particularly useful for evaluating neuromuscular coordination, fatigue, and the timing of muscle recruitment during gait [

16]. However, like goniometry and ultrasound, EMG typically requires controlled laboratory environments, fixed setups, and skilled personnel for accurate data acquisition and interpretation [

6,

14,

15,

16]. These constraints limit their applicability in real-world clinical settings or during routine rehabilitation assessments.

In contrast, wearable sensors provide a portable, accessible, and cost-effective alternative for gait and balance assessment [

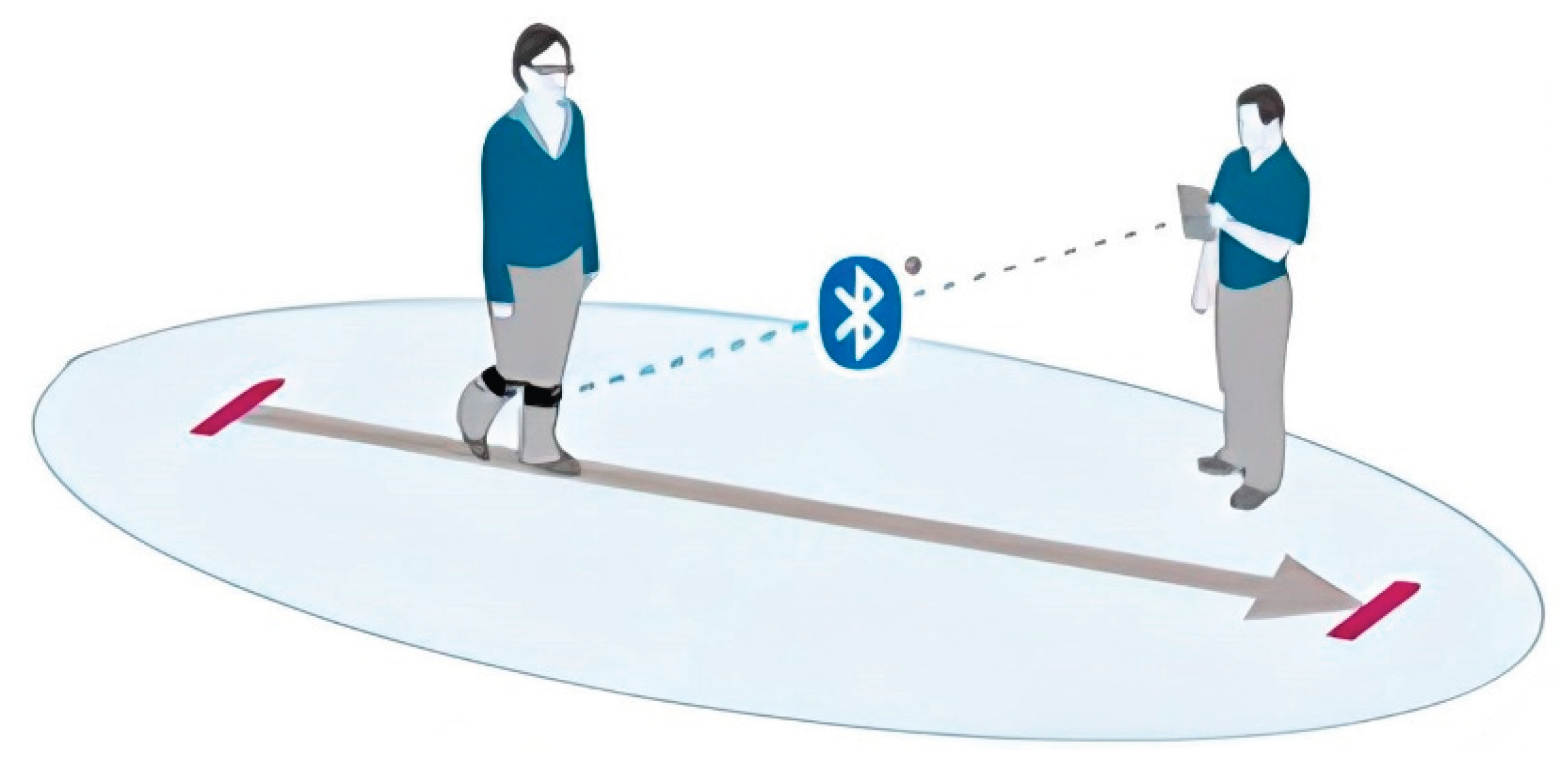

17]. These systems, commonly incorporating IMUs, include accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers that allow for three-dimensional motion capture in real-world environments. When strategically placed on anatomical landmarks such as the pelvis or lower limbs, WS enables continuous monitoring of dynamic activities without restricting natural movement (see

Figure 1) [

18].

The adoption of WS in clinical settings has expanded rapidly due to their ability to collect spatiotemporal gait parameters such as cadence, step length, gait speed, and stance-to-swing phase ratios. Additionally, parameters like pelvic symmetry, stride variability, and gait stability can also be derived, offering valuable insights into functional performance and recovery progression [

19]. The principal advantages of WS include minimal setup time, ease of use, and the possibility for frequent, ecologically valid assessments. These features make WS especially useful for tracking functional improvements during rehabilitation in individuals with lower limb injuries, degenerative diseases, or post-surgical recovery. By enabling objective measurement and longitudinal monitoring, WS support data-driven clinical decisions and personalized therapeutic interventions [

20]. Nevertheless, certain limitations remain. Measurement accuracy may be affected by sensor drift, soft tissue motion artifacts, or external interference, and the interpretation of the resulting data still requires clinical expertise in gait biomechanics. Despite these challenges, the role of WS in contemporary rehabilitation continues to grow, reinforcing their value as an essential tool for evaluating functional mobility and guiding recovery strategies [

21].

Recent advancements in inertial sensor technology have significantly improved the accuracy and reliability of gait analysis. Modern systems now integrate multiple sensors with sophisticated algorithms, allowing for more precise motion tracking and data interpretation. These innovations have expanded the role of inertial sensors in personalized medicine by enabling tailored rehabilitation programs and offering predictive insights into functional recovery [

22]. Given that independent walking is frequently compromised in individuals with lower limb trauma or pathology, often leading to reduced mobility, social isolation and diminished quality of life, there is a growing clinical need for accessible and objective methods to assess and monitor gait abnormalities [

23]. This study was motivated by the need to establish a practical, clinically applicable methodology for gait assessment using wearable inertial sensor systems.

The aim of this study is to develop a methodological framework for kinesiological analysis using wearable inertial sensor systems and to demonstrate their clinical applicability in evaluating pathological gait in orthopedic patients. Through this approach, we hope to contribute to more personalized, effective, and widely accessible rehabilitation strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study population consisted of patients who sought physiotherapeutic and rehabilitative treatment at University Hospital “Dr. G. Stranski” – Pleven, Bulgaria following trauma of the hip joint. The included patients were rehabilitated and examined at the Clinic of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (CPRM), both in the inpatient rehabilitation department and outpatient diagnostic-consultative center of the hospital. The sample included patients aged over 65 years who had undergone surgical intervention for hip fractures, either with osteosynthesis metallica (OM) (Group A, n=15) or arthroplasty (Group B, n=34). All patients used assistive devices, such as underarm crutches, during the rehabilitation period.

Study Design

This observational study employed a “before-after” design, with measurements taken at two time points: at the start of the rehabilitation period (first treatment course with assistive devices) and at the end of the observed period, defined as the time when patients were allowed full weight-bearing on the injured limb. The study duration spanned from July 2023 to December 2024. The observed period was shorter than the entire rehabilitation period, focusing specifically on the gait recovery process.

Gait Analysis Methodology

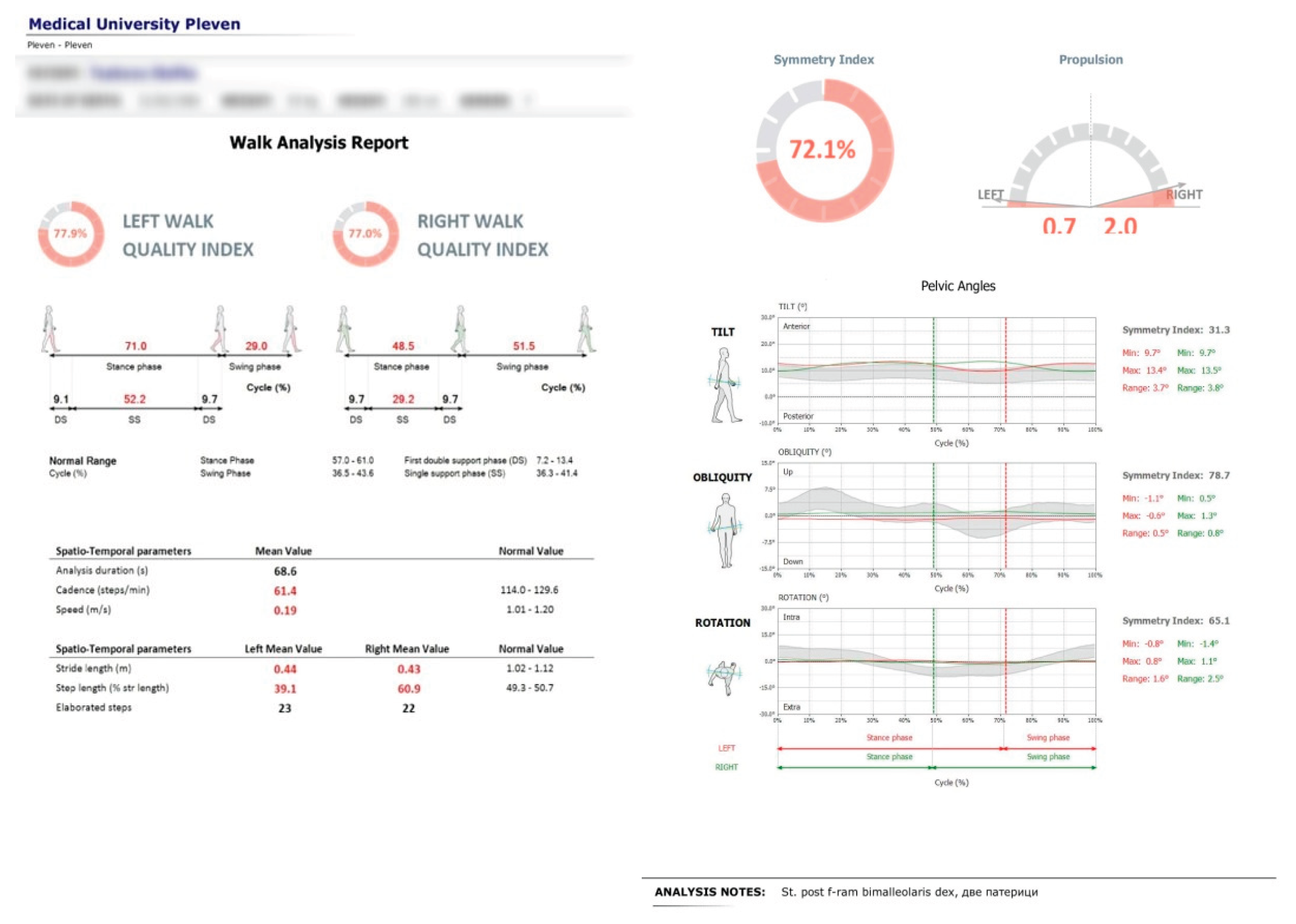

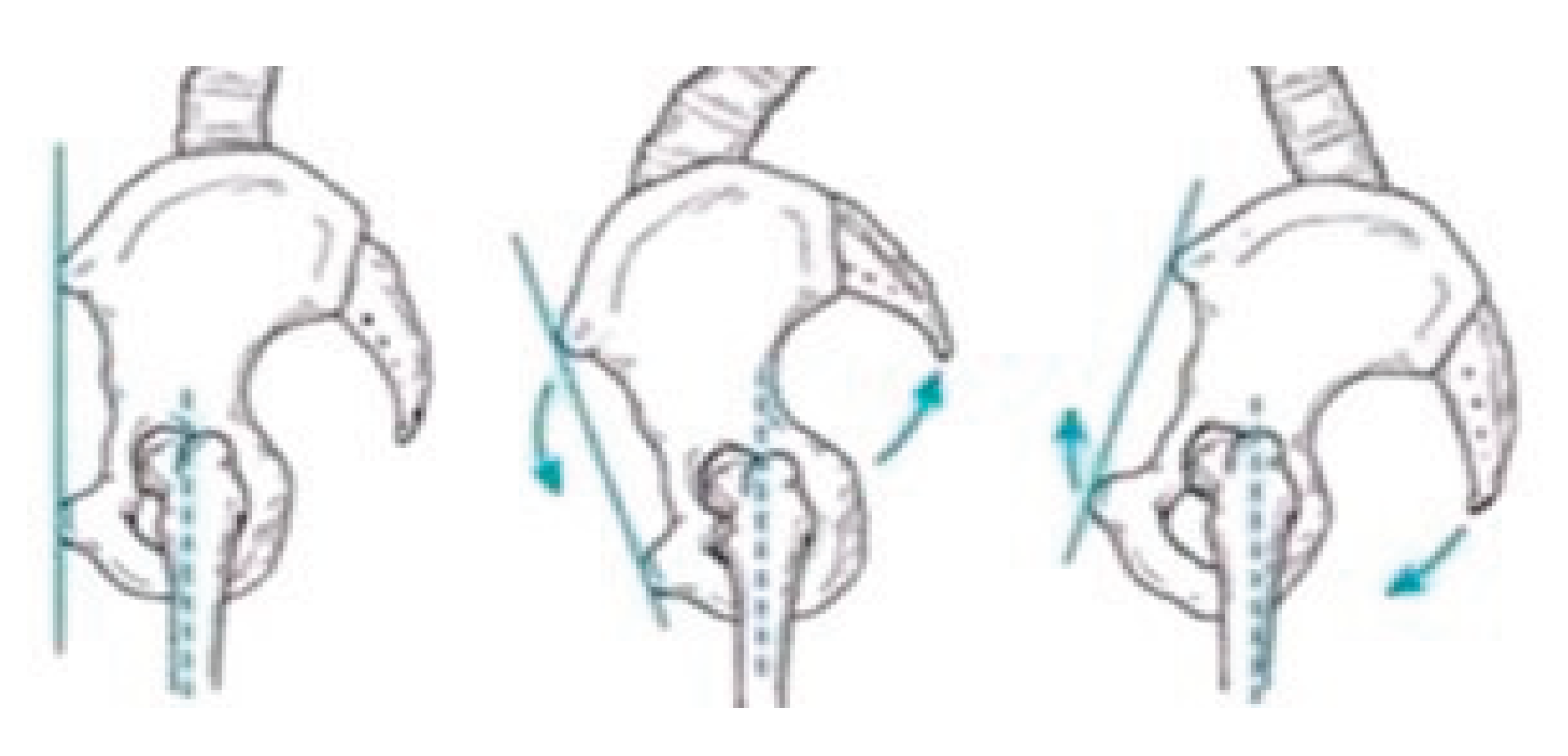

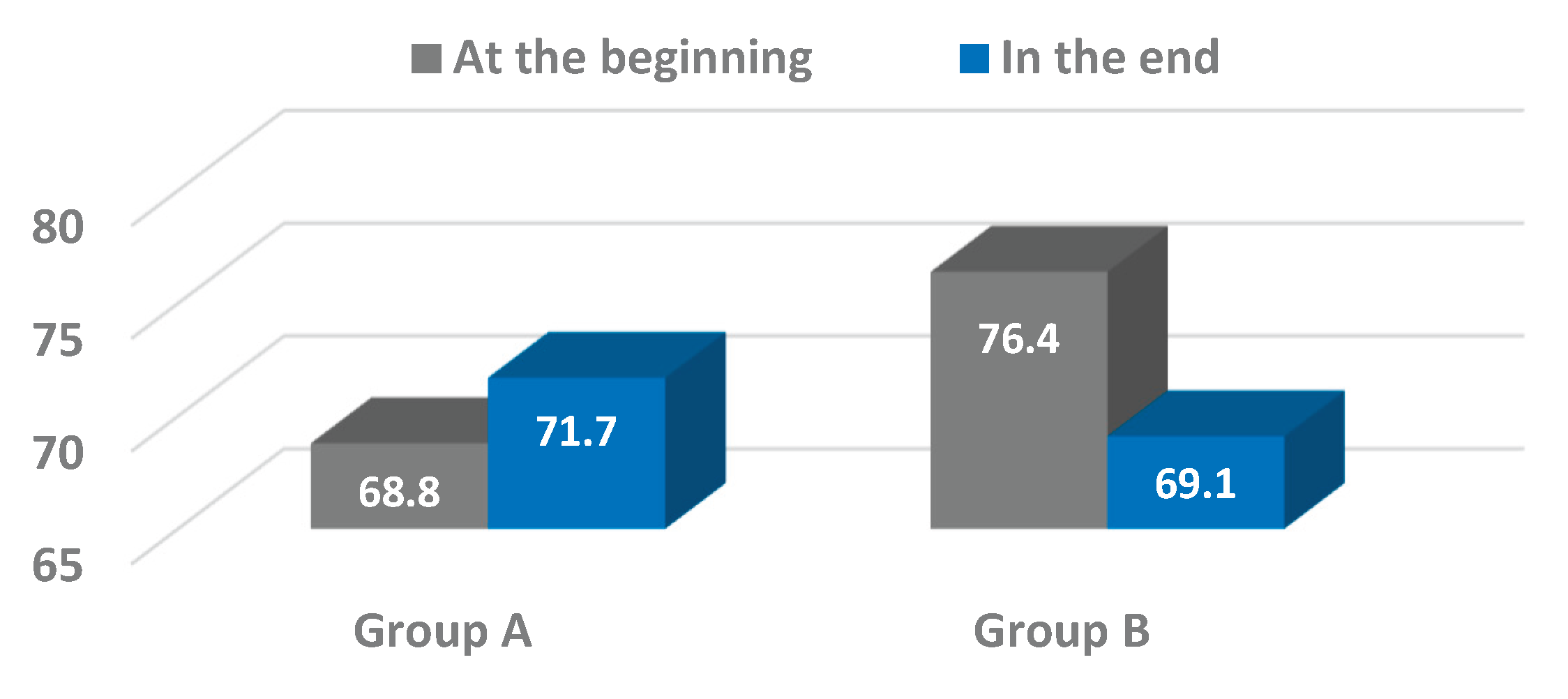

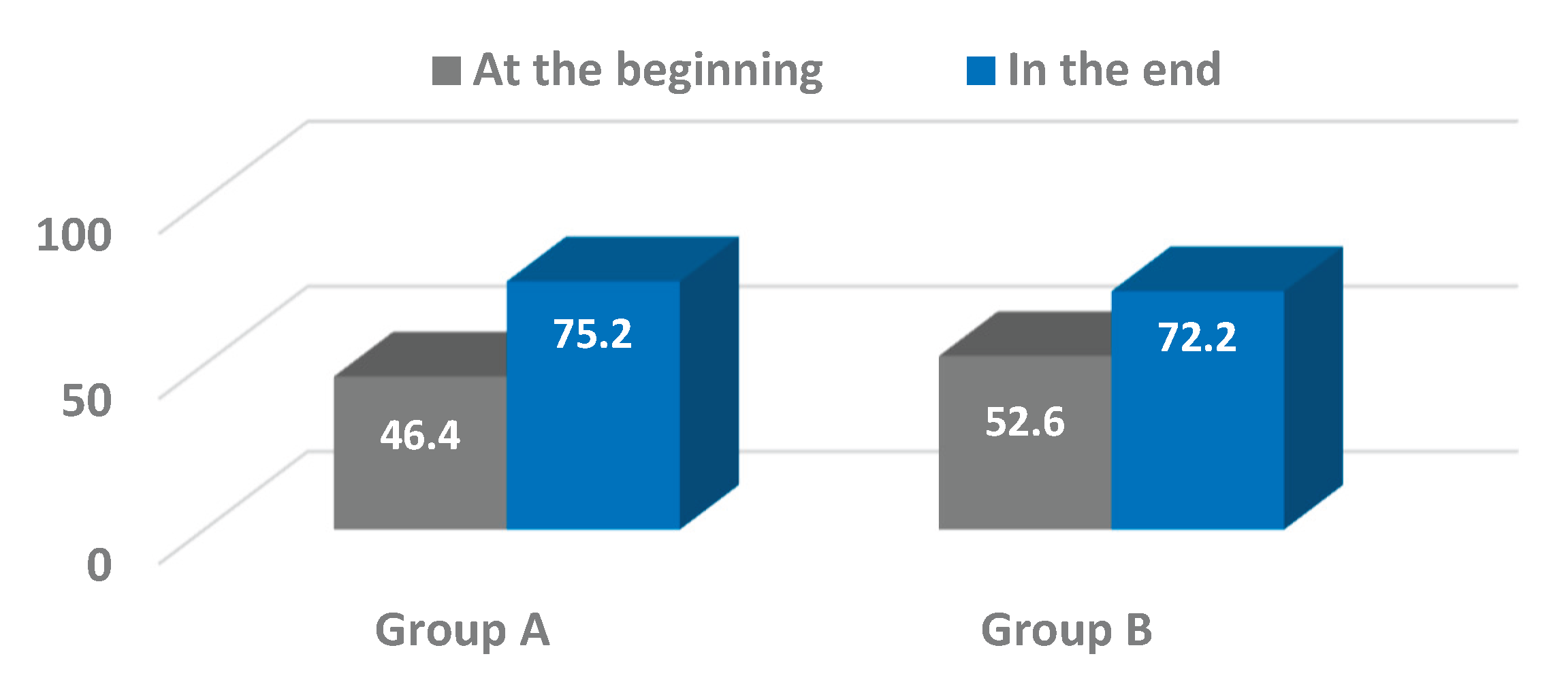

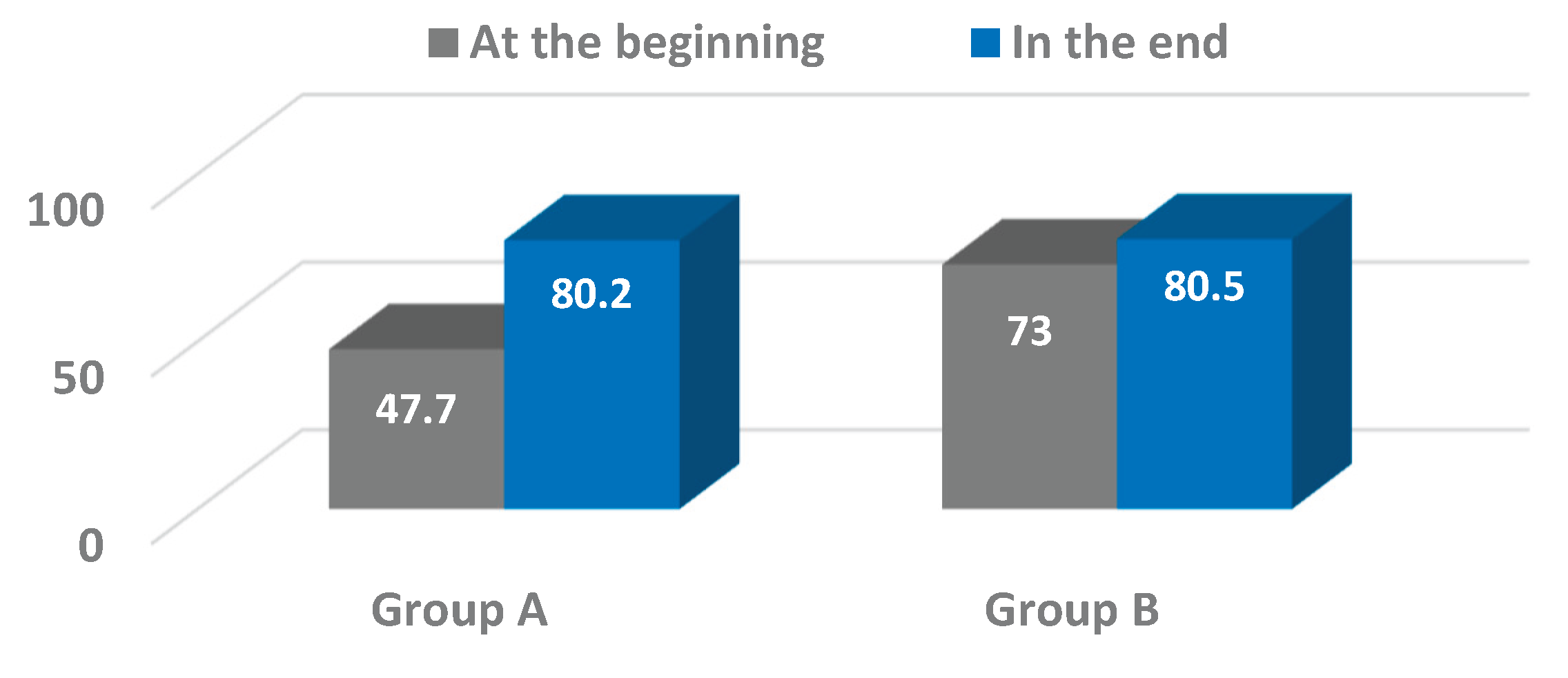

Gait parameters were recorded using the portable inertial sensor device G-WALK (BTS Bioengineering). The sensor was positioned at the pelvic region, centered approximately at the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) or first sacral vertebra (S1). The device captured various gait parameters including gait speed, cadence, and step length. The primary focus of this study was on pelvic oscillations in the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes, expressed as percentages relative to normal ranges (see

Figure 2).

The gait analysis was performed in a clinical environment within the physical therapy ward of CPRM. Each patient was briefed on the procedure and gave informed consent prior to testing. The examination began with a brief anamnesis and review of medical documentation, followed by anthropometric measurements (including limb circumferences and joint range of motion) recorded in an individual patient file.

Patients were registered in the G-WALK software database with their anthropometric data, age, sex, and diagnosis. The sensor was calibrated via Bluetooth connection to a laptop. Patients walked a straight, 10-meter corridor at a self-selected comfortable speed, free from obstacles. Data collected during each gait trial were stored within the device software and documented in the individual patient file.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS software. Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (Cv%), standard error, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Comparative analysis of pre- and post-rehabilitation measurements was conducted using paired t-tests to assess the significance of changes in gait parameters.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University – Pleven, in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted at the University Hospital “Dr. G. Stranski” – Pleven and adhered to the provisions of Ordinance No. 14 of 27.09.2007, which governs the conditions and procedures for conducting therapeutic and non-therapeutic scientific research involving human subjects in Bulgaria.

All participants received detailed information about the purpose and procedures of the study and provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. Consent was obtained using a standardized clinical consent form, ensuring that participants were fully informed about their involvement in the research.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are stored securely on the hospital’s computer system and are not publicly available due to privacy and institutional restrictions. Data can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Generative AI Use

Generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT) was used to assist with language editing and formatting of the manuscript. All scientific content was reviewed and validated by the authors.

4. Discussion

This study examined the rehabilitation outcomes of elderly patients with hip joint trauma, employing a wearable inertial sensor system (BTS G-WALK) to objectively assess pelvic kinematics during gait. The use of this portable sensor technology allowed precise, real-time capture of spatiotemporal and kinematic gait parameters in clinical settings, demonstrating its potential as a valuable tool for monitoring functional recovery in rehabilitation [

24].

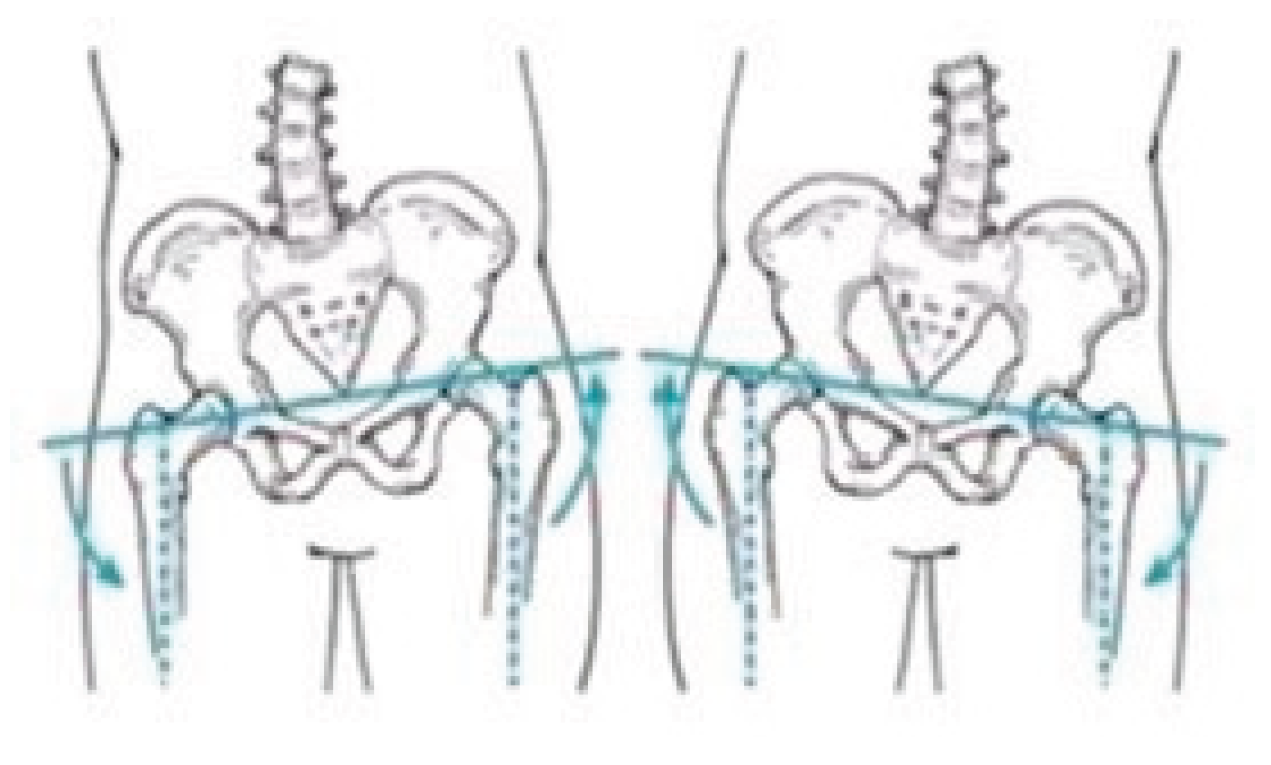

Our findings showed positive trends in pelvic oscillations across the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes during the progression from assisted walking with devices to independent ambulation. Significant improvements were particularly evident in the frontal plane for both osteosynthesis (Group A) and arthroplasty (Group B) patients, with Group A also exhibiting notable progression in the transverse plane. These results are consistent with prior studies emphasizing the importance of pelvic control in maintaining gait stability and efficiency following hip surgery [

25,

26]. The greater improvement observed in Group A’s transverse plane oscillations may reflect compensatory mechanisms associated with postoperative pain and joint preservation, whereas the relatively stable values in Group B align with their use of artificial joints, which tend to reduce pain and mechanical compensation.

The wearable inertial sensor system enabled a detailed analysis of three-dimensional pelvic movements, providing insights that are difficult to achieve with conventional gait analysis methods or subjective clinical evaluation alone. This highlights the growing relevance of wearable sensor technologies in rehabilitation medicine, as they facilitate objective quantification of complex movement patterns and enable continuous monitoring in diverse settings – ranging from clinical environments to patients’ homes [

27,

28]. Such capabilities are crucial for tailoring individualized rehabilitation programs and optimizing therapy outcomes.

While the improvements observed in the frontal and transverse planes were statistically significant or approaching significance, changes in the sagittal plane were less pronounced and did not reach significance within the study period. This variability underscores the multifactorial nature of gait recovery, influenced by factors including pain, muscle strength, joint integrity, and patient compliance. It also suggests that pelvic motion in the sagittal plane may require longer rehabilitation or additional therapeutic focus to achieve significant gains.

The integration of wearable sensors like the BTS G-WALK within rehabilitation protocols offers several advantages: non-invasiveness, portability, ease of use, and the ability to generate automated, quantitative reports. These features support clinicians in making informed decisions and tracking patient progress objectively over time. Moreover, the adoption of wearable sensor technology aligns with emerging trends in digital health and tele-rehabilitation, which have gained increasing importance, especially in contexts limiting frequent clinical visits [

29].

Future research should investigate the longitudinal application of wearable sensor monitoring over extended rehabilitation periods and in larger patient populations. Incorporating machine learning algorithms could further enhance data interpretation, enabling predictive modeling and real-time adaptive feedback for patients. Additionally, correlating sensor-derived gait parameters with patient-reported outcome measures would provide a holistic view of recovery, integrating objective data with subjective experience.

In summary, this study demonstrates that wearable inertial sensors provide a robust and practical approach for assessing gait and pelvic kinematics during rehabilitation following hip trauma. By facilitating detailed, objective movement analysis, these technologies have the potential to revolutionize rehabilitation assessment and contribute to more effective, personalized treatment strategies in musculoskeletal care.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the valuable application of wearable inertial sensor technology in objectively assessing pelvic kinematics during gait rehabilitation in elderly patients following hip surgery. The use of the G-WALK sensor system enabled precise quantification of pelvic oscillations in the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes at two critical time points – ambulation with assistive devices and independent walking without aids. Significant improvements in pelvic motion were observed, particularly in the frontal and transverse planes, reflecting enhanced postural control and gait recovery. Although changes in the sagittal plane were less pronounced, the overall trends suggest positive functional gains.

The portability, ease of use, and real-time data acquisition capabilities of the wearable sensor provided a comprehensive and clinically relevant evaluation that traditional gait assessment methods may lack. This technology facilitated detailed monitoring of subtle gait compensations and rehabilitation progress in a non-invasive, repeatable manner across clinical and ambulatory settings.

These findings underscore the potential of wearable inertial sensors to enhance individualized rehabilitation protocols by enabling objective, continuous, and quantitative gait analysis. Future research should focus on expanding the sample size, exploring long-term outcomes, and integrating sensor data with machine learning algorithms to further optimize patient-specific rehabilitation strategies. The integration of such advanced sensor technology into routine clinical practice holds promise for improving functional recovery and quality of life in patients with lower limb musculoskeletal impairments.