1. Introduction

Proper functioning of the mammalian reproductive system is sensitive to a number of internal and external cues including seasonal variations in photoperiod (Clarke 2011, Wahab, Atika et al. 2013, Clarke 2014, Wahab, Shahab et al. 2015, Clarke and Arbabi 2016). Many mammalian species are seasonal breeders and they have adopted to restrict their fertility to a particular time of the year in order to ensure that the birth and weaning of their offspring take place during the most favorable season of the year (Clarke 2011, Clarke and Caraty 2013, Clarke and Arbabi 2016). Majority of mammalian species use the highly predictable annual variations in photoperiod to establish the favorable time of year and to adapt their reproductive activity accordingly (Nishiwaki-Ohkawa and Yoshimura 2016, Nakane and Yoshimura 2019). The supra-chiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of hypothalamus adjusts circadian rhythms related signals in response to seasonal changes in photoperiod via the retinohypothalamic track (RHT) (Reppert and Weaver 2002). Reppert and colleagues had reported that lesions in the SCN abolish the circadian rhythms in rhesus and squirrel monkeys leading to reproductive abnormalities (Reppert, Perlow et al. 1981, Reppert, Perlow et al. 1981). Animals can be divided into long and short day breeders on the basis of short and long photoperiod. Melatonin is produced by the pineal gland in animals in response to alteration in photoperiod (Challet 2007, Challet 2007). These variations in melatonin production in pineal gland are responsible to establish the seasonal clock in most of the animals (Lincoln, Andersson et al. 2003, Lincoln, Andersson et al. 2003). Thus melatonin serves as a biological signal for the organization of photoperiod dependent seasonal functions such as reproduction, behavior, coat growth and camouflage coloring (Arendt 2005, Arendt 2005). The change in breeding pattern due to melatonin concentrations is mediated by pre-mammilary area of the posterior hypothalamus and the pars tuberalis of the pituitary gland (Malpaux, Migaud et al. 2001). Melatonin also modulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis by acting at hypothalamus (Malpaux, Daveau et al. 1998).

Lehman and colleagues (Lehman, Ladha et al. 2010) has reported peptidergic signaling mechanism that modulates the GnRH pulse generator activity and therefore GnRH is considered as an important regulatory component of the HPG axis which plays a major role in reproduction. The discovery of kisspeptin and its receptor has contributed a lot in the understanding of the reproductive processes (de Roux, Genin et al. 2003, Seminara, Messager et al. 2003) as they are reported to be involved in regulating GnRH secretion, and reproductive cycle of seasonally breeding species.

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) are seasonal breeders with mating season range from October to December and births coincides with the period of highest food availability, i.e., end of rainy season (Higashi, Takahashi et al. 1984, Bansode, Chowdhury et al. 2003, Wahab, Drummer et al. 2020). Circanual variation have been reported in different species of monkeys regarding testicular size, sperm production, semen quality, sexual behavior and hormonal milieu (FSH, LH and testosterone) with maximum values observed during the BS.

The role of kisspeptinergic system has been very well know in reproduction (Wahab, Atika et al. 2016, Ciaramella, Della Corte et al. 2018, Franssen and Tena-Sempere 2018) and seasonal reproduction in hamsters (Revel, Ansel et al. 2007), sheep (Caraty, Smith et al. 2007, Smith, Coolen et al. 2008). Despite of this information, very little is known about neuroendocrine control of seasonality in nonhuman primates. The present study was designed to demonstrate that variations in photoperiod leads to kisspeptin mediated change in reproductive physiology of a seasonally breeding higher primate, rhesus monkeys.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Monkeys

Intact adult (7-9 years old) male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) (N = 10), were used in the present study. The animals were maintained under free ranging conditions in the primate breeding colonies of Kunming Institute of Zoology, Kunming, China. The breeding season (BS) of the rhesus monkeys from Kunming (China) lasts from September to February while March to August is considered as NBS (NBS) (Zheng, Si et al. 2001). The animals were daily fed with fresh fruits and monkey chow. Water was available ad libitum. In order to reduce the stress effects on blood sampling, four animals were habituated to chair restraint several weeks prior to commencement of the experiments. The duration of restraint was gradually increased until it reached 3-6 h per day. The animals were again released to the free ranging environment and were brought back a day before the blood sampling. The animals were sedated with ketamine hydrochloride (Ketler, Astarapin, Germany; 5 mg/kg BW, im) for their placement and removal from the restraining chair. The remaining six animals, used for CSF and tissue collection, were not trained for chair restraint. The sampling was conducted in both breeding and NBS in July-August. All the animal handling protocols and experimental procedures were approved by the Kunming Institute of Zoology Committee for Care and Use of Animals.

2.2. Venous Catheterization

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (10 mg/kg BW, im) and a teflon cannula (BD Vialon, 22 G *1.16” 1.1mm * 30mm; Becton Dickinson, Medical Devices Co., Ltd. Suzhou, P.R. China) was inserted in the saphenous vein for sequential blood sampling (2 ml each time). The distal end of the cannula was attached to a butterfly tube (Length 300 mm, volume 0.29 ml, 20 GX3/4”, JMS, Singapore) and blood was drawn to haparinized vacutainer tubes (Sanli, Liuyang, Hunan, China). Experiments were only initiated when the animals were fully recovered from sedation. Blood was sampled between 1000-1700 hrs for 6 hrs duration on two consecutive days both during BS and NBS. Following withdrawal, equal volume of heparinized (5 IU/ml) normal saline was administered to avoid blood loss and to keep the cannula patent. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min plasma was separated and stored at -80°C until hormonal analysis.

2.3. Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Collection

For CSF collection, animals (N=3) were anesthetized using ketamine HCl (intramuscular: 10 mg/kg) and one ml of CSF was collected from the lumbar vertebrae by using a 22-gauge needle within 15 minutes of anesthesia. Four samples were collected with an interval of 20 minutes during both BS and NBS and immediately preserved at –70°C till further analysis.

2.4. Hormonal Analysis

Plasma testosterone levels were determined by using a commercial testosterone RIA kit (Immunotech, Marseille Cedex 9, France) following the instructions of the manufacturers. Sensitivity of the kit was 0.025ng/ml. Inter and intra assay coefficients of variation were 8.6% and 11.9% respectively. Kisspeptin levels were measured using the KiSS-1 (112-121)-NH2/Kisspeptin-10/Metastin (45-54)-NH2 RIA kit (Phoenix Pharmaceutical, Inc., AZ, USA) following instruction manual provided with the kit. Sensitivity of the kit was 10 pg/ml. Inter and intra assay coefficients of variation were 5-7% and 12-15% respectively.

2.5. Hypothalamus Tissue Collection:

The animals were anesthetized with ketamine HCl (intramuscular 10mg/kg), heart was perfused and brain was surgically removed following the sacrifice. The mediobasal hypothalamus MBH) was located as the area caudal to the optic chiasm, rostral to the mammillary body, medial to the hypothalamic sulcus and the ventral half of the hypothalamus and dissected out.

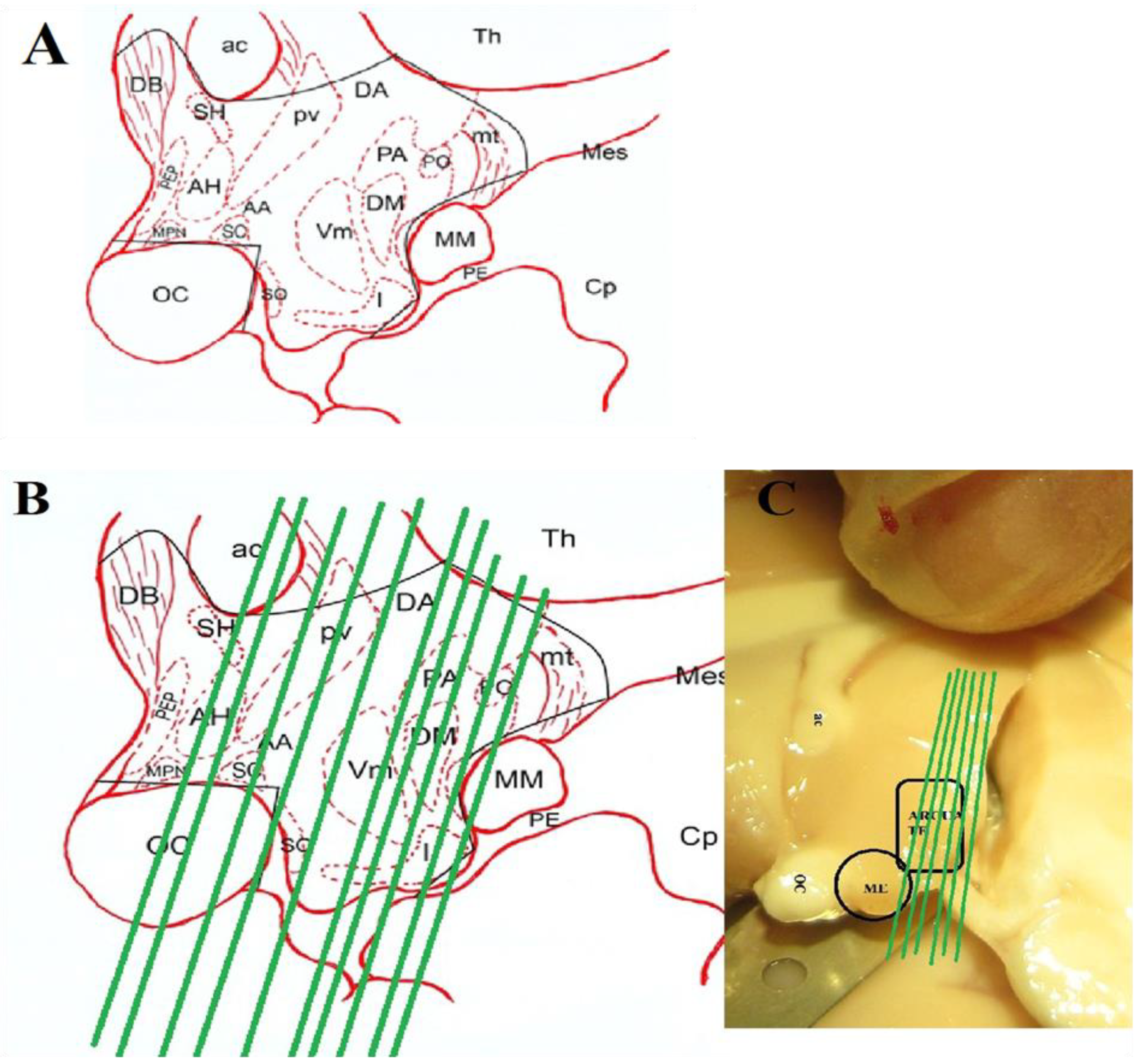

Figure 1 shows the diagrammatic presentation of the MBH location.

One MBH hemi area was snap-frozen on dry ice in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and stored in liquid nitrogen until processed for RNA extraction.

2.6. Tissue Fixation Procedure

One hemi MBH area was kept in 4% para-formaldehyde for 4-6 hrs followed by their transfer to the 20% sucrose until they sunk down to the bottom. The sections were washed with the PBS thrice and transferred to 30% sucrose till they sunk down to the bottom. Opti-mum cutting temperature compound (OCT) was used to cover the tissue, and tissues were kept at -20ºC until they were cut (20µ thick) with Leica CM 1850-Cryostat (Leica Microsystems Nussloch GmbH, Nussloch, Germany) at -28ºC.

2.7. Testicular Tissue Collection

Paired testes were collected immediately after decapitation and were weighed using manual weighing machine.

2.8. Total RNA Extraction and Real Time qPCR

Total RNA from the tissue was extracted using the tRNA extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total RNA was digested with RNase-free DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to remove genomic DNA contamination. The GeneAmp RNA PCR Core kit (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ, USA) was used for reverse transcription with 2 μg of total RNA and random hexamer primers according to the manufacturer's specifications.

The Kiss1, Kiss1r and GnRH1, mRNA expression in hypothalamic tissues from male rhesus monkeys were quantified by real-time PCR (

Table 1 for primer detail). GAPDH was used as internal control. The real time qPCR was performed in a total volume of 20µl. Each reaction contained 1 µl of reverse transcribed sample (1, 0.5, 0.25 and 0 dilutions of one of the hypothalamic sample) 10 µl of BioRad PCR master mix, 0.3 µl of each primer and 8.4µl of DEPC water. Initial step was done at 95ºC for 5min, followed by 40 cycles of a 95 ºC denaturing step for 30 sec, annealing was done at 55 ºC . For kisspeptin the annealing temperature was 65 ºC for 30 sec, and an elongation step at 72 ºC for 30 sec. After amplification dissociation curve were analyzed. Relative mRNA expression was calculated by using ∆∆C

T method.

2.9. Flourescence Immunocytochemistry:

Flourescence immunocytochemistry for kisspeptin, GnRH and KISS1R was performed on frozen sections. The primary antibodies rabbit anti-kisspeptin (1:500, Phoenix Pharmaceutical Inc, AZ, USA); mouse anti GnRH (1:500, Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) and rabbit anti- KISS1R (1:100; Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany) were used for immunocytochemistry. The respective secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz (USA).

Dual labeling was done for kisspeptin/GnRH and KISS1R/GnRH. Sections were rinsed at room temperature in 50mM PBS (ph 7.3, 4×10 minutes), incubated for 30 minutes with 3% hydrogen peroxidase and rinsed again with PBS (3×5min). Sections were then incubated overnight at 4ºC in PBS buffer containing 5% normal goat serum (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), 0.05% Triton X-100 and 0.1% BSA(Sigma Chemical Co.) to block non specific binding. For dual label immunoflouresence staining, the sections were incubated for 48 hrs at 4ºC with cocktail of primary antibodies prepared in PBS goat serum buffer at a dilution of 1:200- 1:500. Sections were washed with PBS (3×5min) at room temperatureand incubated with cocktail of respective secondary antibodies for 1.5 h at room temperature followed by PBS washing (3×5min). The slides were incubated with DAPI for 15 minutes followed by PBS washing and cover slipped by using GEL/MOUNT aqueous mounting media, stored at 4ºC until the microscopic analysis were performed.

For single labeling, same procedure was used as described above with the only difference that only one primary and its corresponding secondary antibody was used.

2.10. Confocal Microscopy

Imaging of fluorescence labeling for kisspeptin, KISS1R and GnRH was performed using an Olympus FV1000 Confocal microscope (Olympus America Inc., Melville, NY, USA). Optical sections along the z-axis were collected at 0.5-1 µm intervals. Composite digital images were converted to JPG format, imported into Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Photoshop CS2, version 9.0; Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and color balance was adjusted.

2.11. Statistical Analyses:

All the data is expressed as mean ±standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical package (Graphpadprizm) was used to compare the mean plasma levels of testosterone, CSF kisspeptin and kisspeptin perikarya, GnRH, KISS1R cell bodies count and number of cell to cell contacts between BS and NBS by applying unpaired student’s t-tests. Significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Season Affected the Kisspeptin, Testosterone Concentrations and Paired Testes Weight in Rhesus Macaques

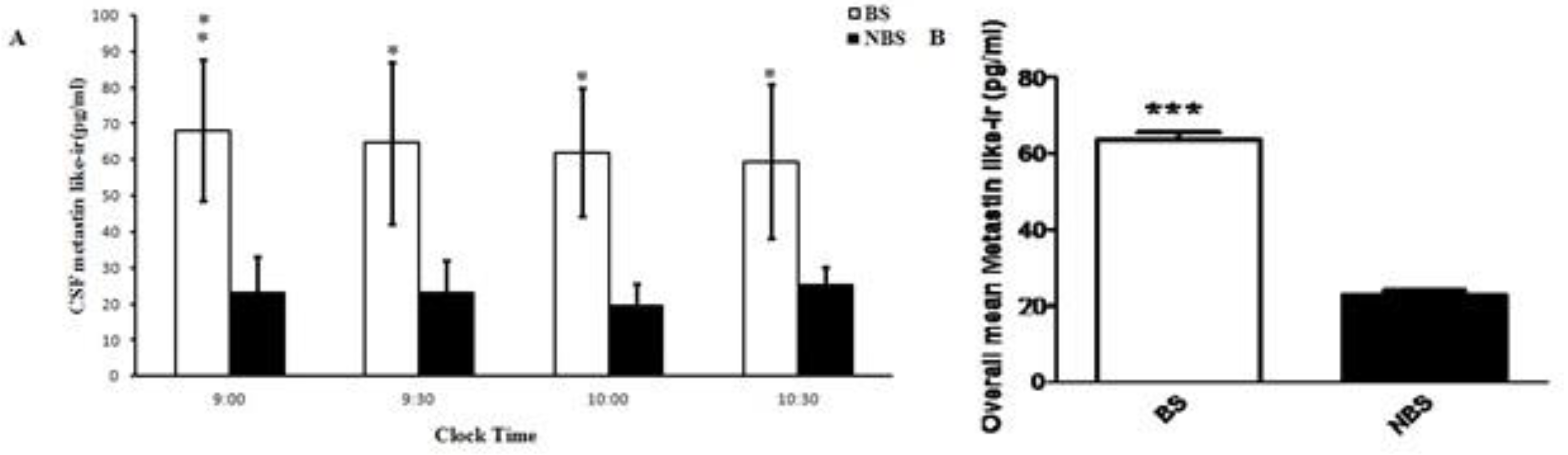

Analysis of the results revealed a significant increase in Cerebro Spinal Fluid (CSF) Kisspeptin like-ir (Kisspeptin) at the four studied time points [09:00 am, 09:30 am, 10:00 am and 10:30 am] during BS when compared with NBS (

Figure 2A). A similar trend was observed, when over all concentration of kisspeptin was compared between BS and NBS (P>0.05) (

Figure 2B).

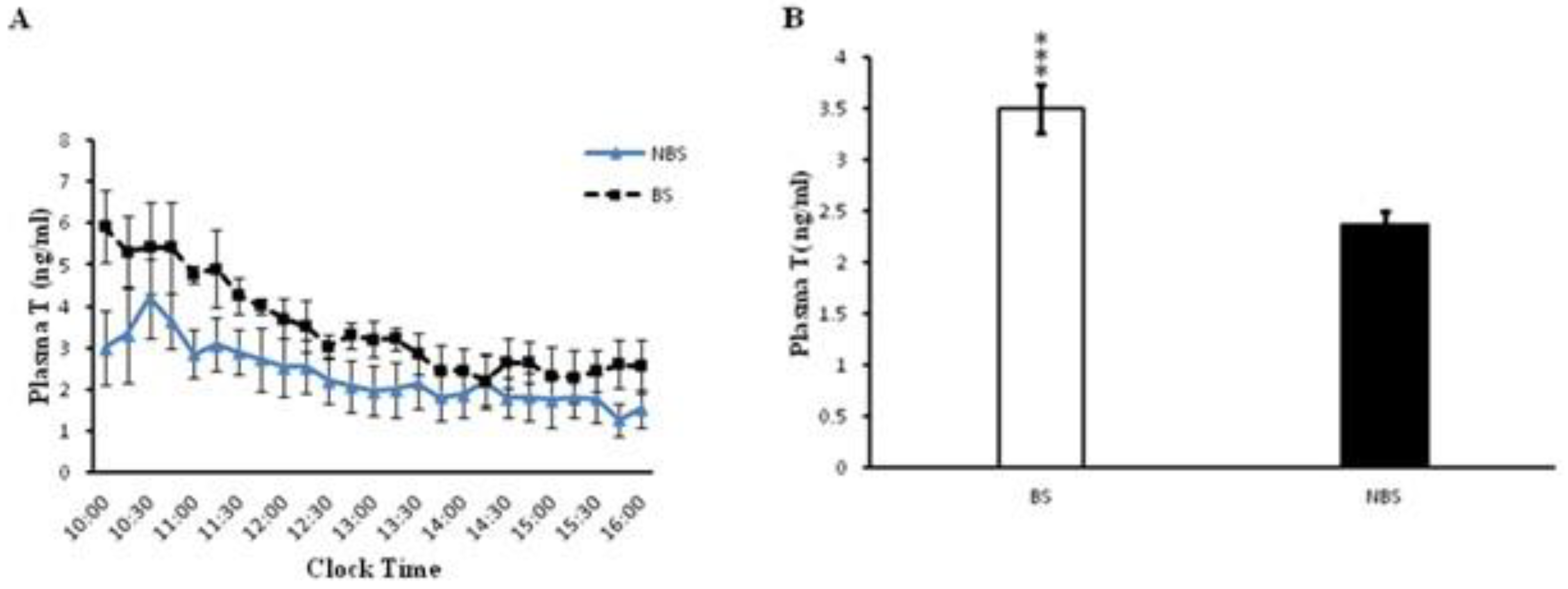

Complementary to what was observed for kisspeptin, higher plasma testosterone levels were detected during BS, at all 13 studied time points between 09:00 am to 04:00 pm, when compared with similar values during NBS (

Figure 3A). Overall, mean testosterone values were significantly higher (P <0.05) during the BS as compared to NBS (

Figure 3B). Testicular weight was also increased during the BS (p < 0.0001).

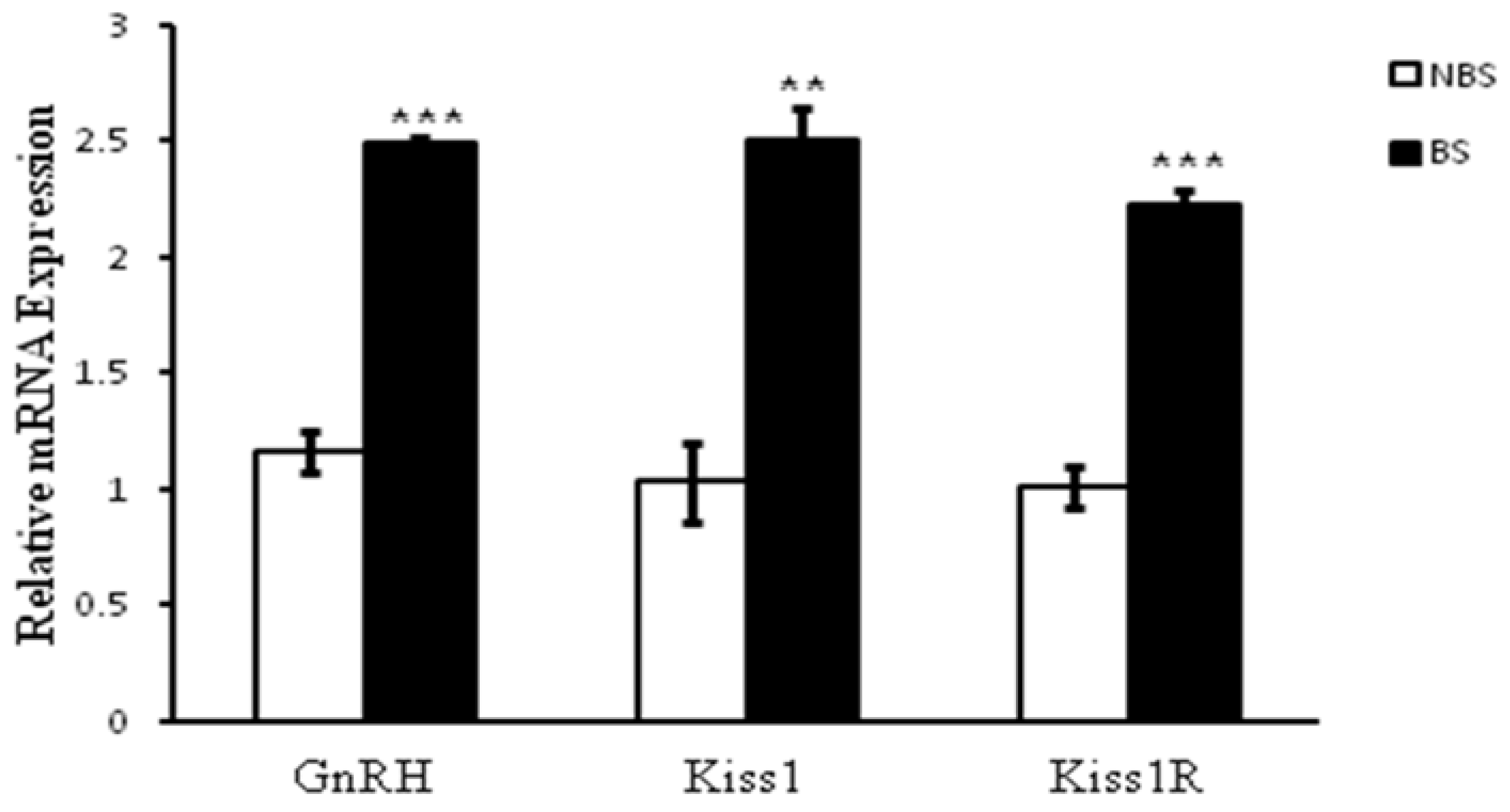

3.2. Season Affected the Expression of Studied Genes

Comparison of mRNA level indicated that GnRH (P < 0.0001), kisspeptin (P < 0.01) and KISS1R (P < 0.0005) had higher expression during the breeding than NBS (

Figure 4).

3.3. Season Affected the Immunocytochemical Expression of KISS1R

The immunocytochemistry analysis indicated an increase in the number of kisspeptin cell bodies in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) region during the BS as compared to the NBS (

Figure 5). An increased interaction of kisspeptin ir with the GnRH ir-fibers was observed in the median eminence (ME) during the BS (

Figure 6A) while there was no such observation in the NBS (

Figure 6B). It was observed that the number of GnRH ir cell bodies in the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) of adult male Rhesus monkeys was not affected by the season (

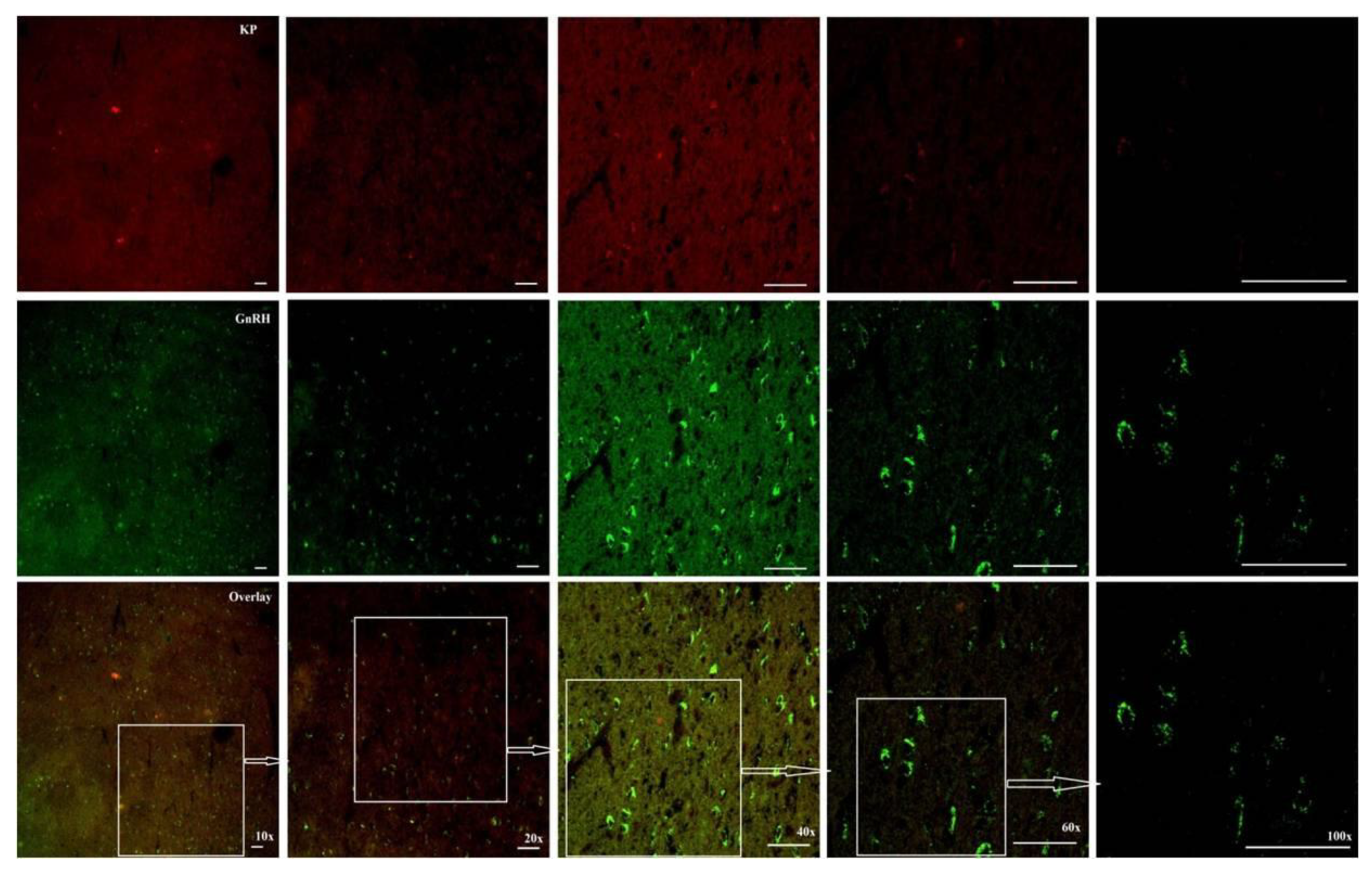

Figure 7). An increased kisspeptin ir and GnRH ir cell bodies count and their interaction in the MBH of the adult male Rhesus monkeys were observed during BS (

Figure 8).

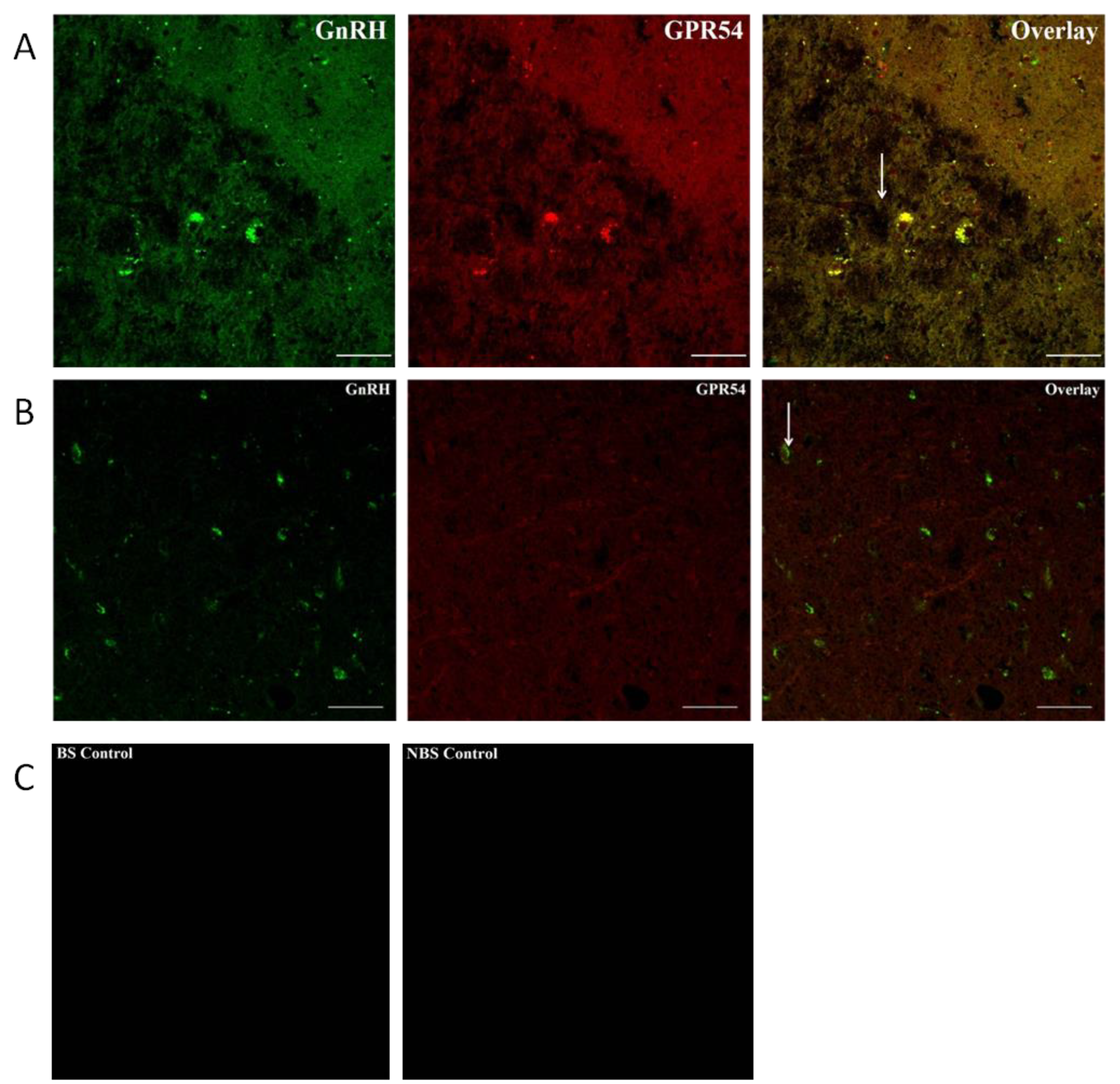

The kisspeptin receptor expression was also increased during the BS as compared to NBS (

Figure 9). Further KISS1R expression specifically on the GnRH neuronal cell bodies was also increased during the BS (

Figure 9) as compared with the NBS (

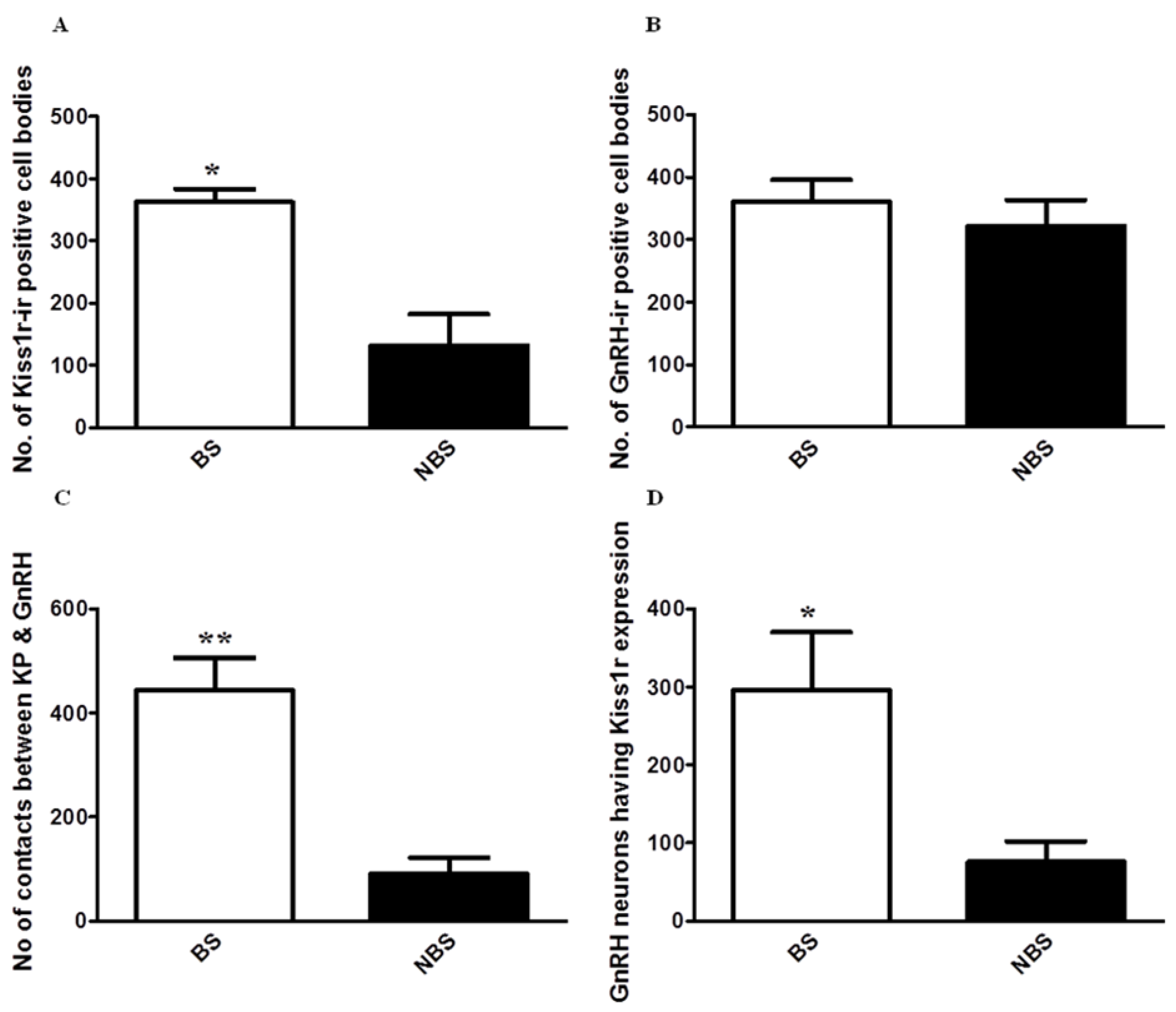

Figure 10). It was also observed that number of Kiss1r and GnRH positive cell bodies increased during BS (

Figure 11A, B). An increased in the number of contacts between kisspeptin and GnRH (

Figure 11C) and GnRH neuronal cell bodies expressing Kiss1r during BS was also observed when compared with NBS (

Figure 11D).

4. Discussion

Seasonal reproduction involves complicated neuroendocrine processes of the HPG axis that is dominantly regulated by photoperiod, a crucial environmental cue (Chemineau, Bodin et al. 2010). GnRH, kisspeptin and KISS1R are known to play role in regulating the reproductive activity in various mammals and non mammals (Abbara, Ratnasabapathy et al. 2013, Wahab, Atika et al. 2016). Since the discovery of reproductive roles of kisspeptin in 2003 (Seminara, Messager et al. 2003), substantial amount of efforts has been put in to discover its role in the seasonality of reproduction (Caraty, Smith et al. 2007, Greives, Mason et al. 2007, Clarke and Smith 2010, Clarke and Caraty 2013). In recent years, it has been found that Kiss1/KISS1R system, which influence GnRH secretion avidly, is regulated by both melatonin and feedback action of gonadal steroid hormones (Smith 2008, Backholer, Smith et al. 2009). Consequently, Kiss1/KISS1R system may play a key role in seasonal reproduction (Clarke and Caraty 2013). The kisspeptin signaling is reported to play a role in passing photoperiodic and environmental signals to increase the reproductive activity during the BS in hamster and sheep (Revel, Saboureau et al. 2006, Ansel, Bentsen et al. 2011, Clarke and Caraty 2013). Little information is available in literature regarding the role of kisspeptin signaling in non-human mammals. Present study describes the qualitative and quantitative expression of the kisspeptin and KISS1R changes during the breeding and NBS in adult male rhesus monkeys.

Analysis of our results revealed an increase in the central Kisspeptin like-ir and peripheral release of testosterone during the BS along with an increase in the testicular weight of the monkeys compared to the NBS indicating a seasonal transition of the monkeys from the non breeding to the BS, leading to an increase in the reproductive activity. Our observations are consistent with the previously reported findings in several seasonal breeders (Bansode, Chowdhury et al. 2003, Greives, Mason et al. 2007, Clarke and Caraty 2013).

An important finding of this study was the seasonal changes in the expression of kisspeptin in the MBH of the adult male rhesus monkeys. A significant increase in the mRNA expression of the Kiss1 and Kiss1R was observed during the breeding as compared to the NBS. Our findings are in agreement with the previous observations in other seasonal breeders like Syrian hamsters (Revel, Saboureau et al. 2006) and sheep (Caraty, Smith et al. 2007, Smith, Clay et al. 2007) but is in contradiction with the observation in the Siberian hamsters (Greives, Mason et al. 2007, Mason, Greives et al. 2007, Greives, Kriegsfeld et al. 2008).

A significant increase in kisspeptin perikarya was also observed in the ARC of the adult male rhesus monkey during the breeding as compared to the NBS. It was interesting that the increased MBH Kiss1 mRNA and number of ARC kisspeptin cell bodies were also associated with the elevated CSF Kisspeptin like-ir levels during the BS. Together, these results reflect an increased kisspeptinergic activity in the hypothalamus of monkeys during BS. These results are in line with the findings of Smith and co-researchers (Smith, Clay et al. 2007) who had reported that the Kiss1 mRNA expression was regulated by sex steroids and season in sheep. They (Smith 2008, Smith 2012) had also reported that the connectivity of the kisspeptin perikarya with the GnRH was increased in the BS.

An important finding of this study was an increase in number of close contacts between kisspeptin and GnRH cell bodies during the breeding as compared to the NBS. Similar results were reported by Clarke and colleagues (Clarke, Smith et al. 2009) in their studies by using sheep as experimental animal.

One of the novel aspects of the present study also is the quantification of KISS1R expression on the GnRH neurons in a higher primate. To assure the validity of out immunocytochemical findings primary antibody omitted control sections were used to assess the non specific kisspeptin, KISS1R and GnRH like-ir. Absence of the discrete immunoreactivity confirmed the lack of non specific binding of the fluorescent labeled secondary antibodies. There was a marked elevation of the KISS1R expression during the breeding compared to the NBS leading to activation of the GnRH neuronal system and resulting in an increase in the reproductive activity. This result is however contrary to what was observed in ewe as Li et al. (Li, Roa et al. 2012) had reported a decrease in the KISS1R expression during the BS. This contradiction indicates that KISS1R expression varies from species to species.

All the foregoing findings of this study provide an important clue towards seasonal switch of the HPG-axis in adult male rhesus monkeys. A possible mechanism for the transition between breeding and NBS can be inferred from these observations. Onset of BS in the adult male rhesus monkeys leads to an increase in Kiss1 and Kiss1R mRNA expression in the ARC causing an increase in the central kisspeptin signaling. However what environmental/ neural/ neuroendocrine signals stimulate seasonal increase in kisspeptinergic signaling remains to be elucidated. Expression of KISS1R on GnRH neurons also increases during the BS leading to augmented binding of the kisspeptin to its receptor that ultimately results in the activation of the GnRH neurons and the HPG-axis which enhances the reproductive activity and leads to an increase in the testicular weight and plasma testosterone levels as observed during BS.

In conclusion, present study demonstrated the semi quantitative differences in the MBH expression of the kisspeptin mRNA and protein during the breeding and the NBS in adult male rhesus monkeys. The expression of hypothalamic Kiss1, Kiss1R and their close contacts with GnRH fibers were found to be higher during the BS. Further, present study established the season related changes in the expression of KISS1R on GnRH neurons for the first time in non-human primate. Based upon these findings, we have postulated that kisspeptin acts as an important arbitrator of the various environmental cues on the reproductive axis. It acts as an excitatory factor to enhance the GnRH pulse generating activity during BS and a decrease in kisspeptin signaling may lead to commencement of the NBS in higher primates.

Authors Contribution

Tanzeel Huma: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing-Original draft preparation Fazal Wahab: Data Analysis, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Zhengbo Wang: Visualization, Investigation. Yuanye Ma: Data collection, data curation.: Xiaohua Liu: Software, Validation.: Furhan Iqban: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Muhammad Shahab: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. Hu Xintian: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Supervision.

Statement of Ethics

The experimental approval for the current study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Zoology Department, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research funds from a TWAS-CAS visiting fellowship awarded to Tanzeel Huma and a Pilot Academy strategic technology projects XDB02020005, National Natural Science Foundation of China 31271167. Tanzeel Huma was also supported by Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan through their indigenous Ph.D fellowship program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbara, A.; Ratnasabapathy, R.; Jayasena, C.N.; Dhillo, W.S. The effects of kisspeptin on gonadotropin release in non-human mammals. Adv Exp Med Biol 2013, 784, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ansel, L.; Bentsen, A.H.; Ancel, C.; Bolborea, M.; Klosen, P.; Mikkelsen, J.D.; Simonneaux, V. Peripheral kisspeptin reverses short photoperiod-induced gonadal regression in Syrian hamsters by promoting GNRH release. Reproduction 2011, 142, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendt, J. Melatonin in humans: it's about time. J Neuroendocrinol 2005, 17, 537–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendt, J. Melatonin: characteristics, concerns, and prospects. J Biol Rhythms 2005, 20, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backholer, K.; Smith, J.; Clarke, I.J. Melanocortins may stimulate reproduction by activating orexin neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus and kisspeptin neurons in the preoptic area of the ewe. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 5488–5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansode, F.W.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Dhar, J.D. Seasonal changes in the seminiferous epithelium of rhesus and bonnet monkeys. J Med Primatol 2003, 32, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraty, A.; Smith, J.T.; Lomet, D.; Said, S.B.; Morrissey, A.; Cognie, J.; Doughton, B.; Baril, G.; Briant, C.; Clarke, I.J. Kisspeptin synchronizes preovulatory surges in cyclical ewes and causes ovulation in seasonally acyclic ewes. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 5258–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challet, E. [Clock genes, circadian rhythms and food intake]. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2007, 55, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challet, E. Minireview: Entrainment of the suprachiasmatic clockwork in diurnal and nocturnal mammals. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 5648–5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemineau, P.; Bodin, L.; Migaud, M.; Thiery, J.C.; Malpaux, B. Neuroendocrine and genetic control of seasonal reproduction in sheep and goats. Reprod Domest Anim 2010, 45, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramella, V.; Della Corte, C.M.; Ciardiello, F.; Morgillo, F. Kisspeptin and Cancer: Molecular Interaction, Biological Functions, and Future Perspectives. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, I. J. Control of GnRH secretion: one step back. Front Neuroendocrinol 2011, 32, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, I. J. Interface between metabolic balance and reproduction in ruminants: focus on the hypothalamus and pituitary. Horm Behav 2014, 66, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, I.J.; Arbabi, L. New concepts of the central control of reproduction, integrating influence of stress, metabolic state, and season. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2016, 56, S165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, I.J.; Caraty, A. Kisspeptin and seasonality of reproduction. Adv Exp Med Biol 2013, 784, 411–430. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, I.J.; Smith, J.T. The role of kisspeptin and gonadotropin inhibitory hormone (GnIH) in the seasonality of reproduction in sheep. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl 2010, 67, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, I.J.; Smith, J.T.; Caraty, A.; Goodman, R.L.; Lehman, M.N. Kisspeptin and seasonality in sheep. Peptides 2009, 30, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Roux, N.; Genin, E.; Carel, J.C.; Matsuda, F.; Chaussain, J.L.; Milgrom, E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 10972–10976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franssen, D.; Tena-Sempere, M. The kisspeptin receptor: A key G-protein-coupled receptor in the control of the reproductive axis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018, 32, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greives, T. J., L. J. Kriegsfeld and G. E. Demas. Exogenous kisspeptin does not alter photoperiod-induced gonadal regression in Siberian hamsters (Phodopus sungorus). Gen Comp Endocrinol 2008, 156, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greives, T. J., A. O. Mason, M. A. Scotti, J. Levine, E. D. Ketterson, L. J. Kriegsfeld and G. E. Demas. Environmental control of kisspeptin: implications for seasonal reproduction. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashi, Y., J. Takahashi, K. Yoshida, S. J. Winters, H. Oshima and P. Troen. Seasonal changes in steroidogenesis in the testis of the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). J Androl 1984, 5, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, M. N., Z. Ladha, L. M. Coolen, S. M. Hileman, J. M. Connors and R. L. Goodman. Neuronal plasticity and seasonal reproduction in sheep. Eur J Neurosci 2010, 32, 2152–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q., A. Roa, I. J. Clarke and J. T. Smith. Seasonal variation in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone response to kisspeptin in sheep: possible kisspeptin regulation of the kisspeptin receptor. Neuroendocrinology 2012, 96, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, G. A., H. Andersson and I. J. Clarke. Prolactin cycles in sheep under constant photoperiod: evidence that photorefractoriness develops within the pituitary gland independently of the prolactin output signal. Biol Reprod 2003, 69, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, G.A.; Andersson, H.; Hazlerigg, D. Clock genes and the long-term regulation of prolactin secretion: evidence for a photoperiod/circannual timer in the pars tuberalis. J Neuroendocrinol 2003, 15, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpaux, B.; Daveau, A.; Maurice-Mandon, F.; Duarte, G.; Chemineau, P. Evidence that melatonin acts in the premammillary hypothalamic area to control reproduction in the ewe: presence of binding sites and stimulation of luteinizing hormone secretion by in situ microimplant delivery. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpaux, B.; Migaud, M.; Tricoire, H.; Chemineau, P. Biology of mammalian photoperiodism and the critical role of the pineal gland and melatonin. J Biol Rhythms 2001, 16, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.O.; Greives, T.J.; Scotti, M.A.; Levine, J.; Frommeyer, S.; Ketterson, E.D.; Demas, G.E.; Kriegsfeld, L.J. Suppression of kisspeptin expression and gonadotropic axis sensitivity following exposure to inhibitory day lengths in female Siberian hamsters. Horm Behav 2007, 52, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakane, Y.; Yoshimura, T. Photoperiodic Regulation of Reproduction in Vertebrates. Annu Rev Anim Biosci 2019, 7, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiwaki-Ohkawa, T.; Yoshimura, T. Molecular basis for regulating seasonal reproduction in vertebrates. J Endocrinol 2016, 229, R117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reppert, S.M.; Perlow, M.J.; Tamarkin, L.; Orloff, D.; Klein, D.C. The effects of environmental lighting on the daily melatonin rhythm in primate cerebrospinal fluid. Brain Res 1981, 223, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reppert, S.M.; Perlow, M.J.; Ungerleider, L.G.; Mishkin, M.; Tamarkin, L.; Orloff, D.G.; Hoffman, H.J.; Klein, D.C. Effects of damage to the suprachiasmatic area of the anterior hypothalamus on the daily melatonin and cortisol rhythms in the rhesus monkey. J Neurosci 1981, 1, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reppert, S.M.; Weaver, D.R. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 2002, 418, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revel, F.G.; Ansel, L.; Klosen, P.; Saboureau, M.; Pevet, P.; Mikkelsen, J.D.; Simonneaux, V. Kisspeptin: a key link to seasonal breeding. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2007, 8, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revel, F.G.; Saboureau, M.; Masson-Pevet, M.; Pevet, P.; Mikkelsen, J.D.; Simonneaux, V. Kisspeptin mediates the photoperiodic control of reproduction in hamsters. Curr Biol 2006, 16, 1730–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminara, S.B.; Messager, S.; Chatzidaki, E.E.; Thresher, R.R.; Acierno, J.S., Jr. .; Shagoury, J.K.; Bo-Abbas, Y.; Kuohung, W.; Schwinof, K.M.; Hendrick, A.G.; Zahn, D.; Dixon, J.; Kaiser, U.B.; Slaugenhaupt, S.A.; Gusella, J.F.; S. O'Rahilly; Carlton, M.B.; Crowley, W.F., Jr..; Aparicio, S.A.; Colledge, W.H. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med 2003, 349, 1614-1627.

- Smith, J. T. Kisspeptin signalling in the brain: steroid regulation in the rodent and ewe. Brain Res Rev 2008, 57, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. T. The role of kisspeptin and gonadotropin inhibitory hormone in the seasonal regulation of reproduction in sheep. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2012, 43, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.T.; Clay, C.M.; Caraty, A.; Clarke, I.J. KiSS-1 messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the hypothalamus of the ewe is regulated by sex steroids and season. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.T.; Coolen, L.M.; Kriegsfeld, L.J.; Sari, I.P.; Jaafarzadehshirazi, M.R.; Maltby, M.; Bateman, K.; Goodman, R.L.; Tilbrook, A.J.; Ubuka, T.; Bentley, G.E.; Clarke, I.J.; Lehman, M.N. Variation in kisspeptin and RFamide-related peptide (RFRP) expression and terminal connections to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the brain: a novel medium for seasonal breeding in the sheep. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 5770–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, F.; Atika, B.; Shahab, M. Kisspeptin as a link between metabolism and reproduction: evidences from rodent and primate studies. Metabolism 2013, 62, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, F.; Atika, B.; Shahab, M.; Behr, R. Kisspeptin signalling in the physiology and pathophysiology of the urogenital system. Nat Rev Urol 2016, 13, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, F.; Drummer, C.; Matz-Rensing, K.; Fuchs, E.; Behr, R. Irisin is expressed by undifferentiated spermatogonia and modulates gene expression in organotypic primate testis cultures. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2020, 504, 110670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, F.; Shahab, M.; Behr, R. The involvement of gonadotropin inhibitory hormone and kisspeptin in the metabolic regulation of reproduction. J Endocrinol 2015, 225, R49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Si, W.; Wang, H.; Zou, R.; Bavister, B.D.; Ji, W. Effect of age and breeding season on the developmental capacity of oocytes from unstimulated and follicle-stimulating hormone-stimulated rhesus monkeys. Biol Reprod 2001, 64, 1417–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A) Diagrammatic presentation of the hypothalamic location. B) Orientation of section. C) Original picture of the tissue block with plane of sectioning.

Figure 1.

A) Diagrammatic presentation of the hypothalamic location. B) Orientation of section. C) Original picture of the tissue block with plane of sectioning.

Figure 2.

A) CSF Kisspeptin like-ir value of male Rhesus monkeys (N = 3) at different time points during BS and NBS. CSF Kisspeptin was significantly elevated in BS (p< 0.05–0.005). B) Overall CSF Kisspeptin like-ir values of the adult male rhesus monkeys (N = 3). All the data is expressed as mean ±SEM. Unpaired t-test indicated a highly significant increase in CSF Kisspeptin during BS (p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

A) CSF Kisspeptin like-ir value of male Rhesus monkeys (N = 3) at different time points during BS and NBS. CSF Kisspeptin was significantly elevated in BS (p< 0.05–0.005). B) Overall CSF Kisspeptin like-ir values of the adult male rhesus monkeys (N = 3). All the data is expressed as mean ±SEM. Unpaired t-test indicated a highly significant increase in CSF Kisspeptin during BS (p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

A) Mean ± SEM plasma testosterone levels during BS and NBS in male rhesus monkeys (n=4). Two way ANOVA followed by F-crit as post test indicated highly significant effect with respect to time and season (p < 0.0001). B) Overall mean ± SEM plasma testosterone levels were increased (p < 0.0001) during the BS.

Figure 3.

A) Mean ± SEM plasma testosterone levels during BS and NBS in male rhesus monkeys (n=4). Two way ANOVA followed by F-crit as post test indicated highly significant effect with respect to time and season (p < 0.0001). B) Overall mean ± SEM plasma testosterone levels were increased (p < 0.0001) during the BS.

Figure 4.

The relative mRNA expression for GnRH, Kiss1, and Kiss1r in the hypothalamus of the adult male Rhesus monkey (N = 3). GnRH (P < 0.0001), kisspeptin (P < 0.01) and GPR54 (P < 0.0005) had higher expression during the BS than NBS.

Figure 4.

The relative mRNA expression for GnRH, Kiss1, and Kiss1r in the hypothalamus of the adult male Rhesus monkey (N = 3). GnRH (P < 0.0001), kisspeptin (P < 0.01) and GPR54 (P < 0.0005) had higher expression during the BS than NBS.

Figure 5.

A) Number of kisspeptin perikrya in the BS and NBS in the ARC of the adult male Rhesus monkeys. B) Semi quantitative data of kisspeptin cell bodies count in the ARC. C) Antibody ommitted control for the BS and NBS.

Figure 5.

A) Number of kisspeptin perikrya in the BS and NBS in the ARC of the adult male Rhesus monkeys. B) Semi quantitative data of kisspeptin cell bodies count in the ARC. C) Antibody ommitted control for the BS and NBS.

Figure 6.

Kisspeptin-ir and GnRH ir fibers expression and colocalization as observed in the median eminence (ME) of the adult male rhesus monkeys (N = 3) (40x magnification). Arrows indicates the magnified area. Increased interaction of kisspeptin ir- with the GnRH Ir-fibers was observed in the ME during the BS (A), no such observation in the NBS (B).

Figure 6.

Kisspeptin-ir and GnRH ir fibers expression and colocalization as observed in the median eminence (ME) of the adult male rhesus monkeys (N = 3) (40x magnification). Arrows indicates the magnified area. Increased interaction of kisspeptin ir- with the GnRH Ir-fibers was observed in the ME during the BS (A), no such observation in the NBS (B).

Figure 7.

GnRH-ir cell bodies in the full name (MBH) of adult male Rhesus monkeys during BS and NBS without any apparent change. Control for GnRH immunoreactivity is also visible.

Figure 7.

GnRH-ir cell bodies in the full name (MBH) of adult male Rhesus monkeys during BS and NBS without any apparent change. Control for GnRH immunoreactivity is also visible.

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph at 10, 20, 40, 60 and 100x indicating the increased kisspeptin ir and GnRH ir cell bodies count and their interaction in the MBH of the adult male Rhesus monkeys during the BS.

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph at 10, 20, 40, 60 and 100x indicating the increased kisspeptin ir and GnRH ir cell bodies count and their interaction in the MBH of the adult male Rhesus monkeys during the BS.

Figure 9.

Observations as described in figure 8. The kisspeptin ir cell bodies and their interaction with the GnRH ir cell bodies were decreased during the NBS.

Figure 9.

Observations as described in figure 8. The kisspeptin ir cell bodies and their interaction with the GnRH ir cell bodies were decreased during the NBS.

Figure 10.

Photomicrograph showing the GnRH, Kiss1r immunoreactivity and their interaction in the MBH of the adult male Rhesus monkeys (N = 3) during BS (A) and NBS (B). Antibody omitted controls are also shown for kiss1r. The kiss1 receptor expression and its interaction with GnRH neuronal cell bodies were increased in the BS which was not observed during NBS.

Figure 10.

Photomicrograph showing the GnRH, Kiss1r immunoreactivity and their interaction in the MBH of the adult male Rhesus monkeys (N = 3) during BS (A) and NBS (B). Antibody omitted controls are also shown for kiss1r. The kiss1 receptor expression and its interaction with GnRH neuronal cell bodies were increased in the BS which was not observed during NBS.

Figure 11.

Comparison of A) number of kiss1r-ir cell bodies, B) number of GnRH positive cell bodies, C) number of contacts between kisspeptin and GnRH, and D) GnRH neuronal cell bodies expressing Kiss1r during NB and NBS. Data is expressed as mean ±SEM.

Figure 11.

Comparison of A) number of kiss1r-ir cell bodies, B) number of GnRH positive cell bodies, C) number of contacts between kisspeptin and GnRH, and D) GnRH neuronal cell bodies expressing Kiss1r during NB and NBS. Data is expressed as mean ±SEM.

Table 1.

Primers used for the RT-qPCR.

Table 1.

Primers used for the RT-qPCR.

| Serial No |

Gene |

Accession Number |

Forward Primer

5’-3’ |

Reverse Primer

5’-3’ |

Product Size

(bp) |

| 1 |

KISS1 |

XM_001098284.2 |

ACCGAGAGGAAGCCGTCTGCTA |

AGTTGTAGTTCGGCAGGTCCTTCT |

181 |

| 2 |

KISS1R |

XM_001117198.1 |

CTCGCTGGTCATCTACGTCA |

CGAACTTGCACATGAAATCG |

173 |

| 3 |

GnRH |

NM_001195436.1 |

CGGCTGGAGGAAAGAGAGATGCCG |

GCCAGTTGACCAACCTCTTTGA |

76 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).