1. Introduction

Cholecystectomy, conducted more than 1.2 million times per year in the United States, is fundamental in the treatment of gallbladder disease [

1]. Despite breakthroughs in surgical techniques enhancing results, problems remain in complex patients, resulting in elevated complication rates, extended hospital stays, and greater healthcare expenditures [

2]. Complications such as bile duct damage, surgical infections, and hemorrhage present considerable concerns to patient safety and impose large economic burdens on global healthcare systems [

3,

4].

This review aims to explore the factors contributing to difficult cholecystectomies, focusing on three major conditions—cirrhosis, sclero-atrophic cholecystitis (SAC), and gangrenous cholecystitis (GC)—that heighten the risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications. By examining the pathophysiology, surgical challenges and outcomes associated with these conditions, this article seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of strategies to mitigate risks and improve surgical success.

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative review was conducted to summarize the current understanding and surgical approaches to cholecystectomy in complex clinical contexts, namely liver cirrhosis, SAC, and GC.

A comprehensive literature search was performed using PubMed, and Google Scholar for studies published between January 2005 and May 2024. The search strategy included combinations of keywords and MeSH terms: “cholecystectomy”, “liver cirrhosis”, “sclero-atrophic cholecystitis”, “gangrenous cholecystitis”, “laparoscopic surgery”, and “robotic surgery”.

Inclusion criteria were original clinical studies (prospective or retrospective), meta-analyses and systematic reviews, case series, english-language articles involving human subjects.

Exclusion criteria were non-peer-reviewed articles, animal studies, and isolated case reports unless considered clinically impactful or illustrative.

The selection process involved two independent reviewers who screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text evaluation. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. References of included articles were manually reviewed to identify additional relevant sources.

Articles were assessed for their relevance to surgical indications, intraoperative challenges, perioperative management, and patient outcomes. The review was conducted in accordance with the SANRA (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles) guidelines to ensure scientific quality.

3. Cholecystectomy in Cirrhosis

3.1. Pathophysiological Challenges of Cholecystectomy in Cirrhosis

Gallstones, particularly those in the gallbladder, are prevalent among patients with cirrhosis, with an incidence of 9.5-29.4%, in contrast to 5.2-12.8% in those without cirrhosis [

5]. Their occurrence is increasing with age, female gender, thickness of the gallbladder wall and severity of concomitant liver disease [

6,

7].

Liver cirrhosis introduces a unique set of pathophysiological challenges that complicate gallbladder surgery. The altered hepatic architecture and impaired liver function significantly increase surgical risks, requiring meticulous perioperative management.

Cirrhosis impairs gallbladder mobility and alters bile composition, frequently leading to gallstone development. Moreover, portal hypertension often results in gallbladder wall thickening, edema, and vascular engorgement, which may obscure anatomical landmarks during surgery, complicating dissection and heightening the risk of damage [

8].

Patients with cirrhosis face heightened risks during cholecystectomy due to several key factors.

Cirrhosis diminishes the synthesis of clotting factors, leading to coagulopathy. This, together with thrombocytopenia due to splenic sequestration, elevates the risk of perioperative hemorrhage [

9].

Increased portal venous pressure may lead to the formation of varices within the hepatobiliary vascular system, which carry a risk of rupture during surgical procedures. Moreover, this condition intensifies fluid shifts, resulting in perioperative instability. [

10].

Ascites presents challenges in the surgical field, heightening the likelihood of infection and hindering the process of wound healing. Persistent ascites correlates with unfavorable postoperative outcomes and an increased likelihood of hernia development [

11].

Cirrhotic patients frequently exhibit immunocompromise, rendering them more vulnerable to perioperative infections, such as bile peritonitis in instances of gallbladder perforation [

12].

3.2. Indications and Timing of Surgery: Elective vs. Emergency Cholecystectomy in Cirrhotic Patients

The timing of cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients, whether elective or emergent, is a crucial factor influencing results. Elective cholecystectomy is typically advised for patients with compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class A or B) as it facilitates preoperative optimization and diminishes the likelihood of perioperative complications. Conversely, emergency cholecystectomy is frequently required for acute illnesses such gallbladder cancer or perforation, but it is associated with markedly elevated morbidity and fatality rates due to the patients’ impaired physiological status [

13].

N’Guyen et al. conducted the following Pre-operative recommendations:

- a)

Medically optimize the patient: manage ascites, rectify coagulopathy [administer fresh frozen plasma (when INR >1.5) and platelets (<50/mm3)];

- b)

Cirrhotic individuals with hemoglobin levels below 10 g/dL should get corrective blood transfusions prior to abdominal surgery;

- c)

Acquire pre-operative imaging to identify abdominal wall varices or a recanalized umbilical vein and to exclude hepatoma [

14]. Evaluate the use of a cholecystostomy tube in patients classified as Child class C (MELD > 13) [

15,

16].

Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is preferred for cirrhotic patients who do not exhibit substantial portal hypertension or ascites. This method facilitates the optimization of coagulopathy and the control of comorbidities, thereby diminishing the risk of hemorrhage, bile duct damage, and postoperative infections [

16]. Research indicates that elective operations yield reduced rates of conversion to open surgery and enhanced long-term outcomes relative to emergency interventions [

8].

In cirrhotic individuals, emergency cholecystectomy is frequently imperative in instances of severe acute cholecystitis or consequences like perforation. Nonetheless, these treatments include increased risks of intraoperative hemorrhage, hemodynamic instability, and extended hospitalizations due to insufficient time for preoperative preparation [

17]. The mortality rate for emergency procedures is significantly elevated, especially in patients with decompensated cirrhosis [

18].

Determining the time of surgery necessitates a thorough evaluation of liver function, the extent of cirrhosis, and the immediacy of the clinical situation. In patients with advanced cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class C), non-surgical interventions like percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) may be contemplated as a temporary measure prior to elective surgery or final treatment [

19,

20].

3.3. Surgical Techniques and Modifications: Laparoscopic vs. Open Approaches and Robotic Innovations

The technical challenges associated with cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients are numerous and can be categorized as follows:

Risk of collateral wound formation in the periumbilical region during optical trocar insertion;

Hemorrhagic risk associated with vascular adhesions;

Challenges in liver retraction and exposure of the Calot triangle;

Hazardous approach to the vesicular pedicle in the context of portal hypertension;

Hemorrhagic dissection of the vesicular bed. The challenges are further intensified in patients who have undergone surgery for acute or chronic cholecystitis [

21].

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has predominantly supplanted open cholecystectomy (OC) as the favored method for gallbladder excision, especially in patients with cirrhosis, owing to its reduced morbidity, abbreviated hospitalizations, and expedited recovery periods [

22].

In cirrhotic patients, LC has the additional benefit of diminished ascites-related complications and reduced interference with hepatic blood flow compared to open cholecystectomy [

8].

Nonetheless, obstacles persist with laparoscopic cholecystectomy in this patient demographic, especially owing to the fragile tissue composition, altered anatomy resulting from portal hypertension, and the potential for hemorrhage from engorged veins inside the hepatobiliary triangle. In instances of advanced cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class C) or significant ascites, oral contraceptives may still be warranted, however accompanied by increased risks [

23].

Preoperative optimization, encompassing the correction of coagulopathy, management of ascites, and meticulous identification of patients with compensated cirrhosis, is essential for reducing surgical risks [

24].

Numerous operational details hold significance:

1. Surgical configuration: Although it is acknowledged that trocars disrupt collateral circulation to a lesser extent than a midline incision, the periumbilical region should be circumvented;

2. Following the insertion of the initial trocar, transillumination of the abdominal wall facilitates the avoidance of collateral structures;

3. The positioning of the subxiphoid port to the right of the midline prevents damage to the falciform ligament and the possibly repermeabilized umbilical vein;

4. If the left lobe intrudes upon the operational field, the surgeon should elevate the patient’s right shoulder and/or utilize a long port or converter placed into the epigastric port; if this is inadequate, an additional port should be inserted to retract the left lobe;

5. During the operation, it is crucial to prevent excessive traction on the gallbladder to avert avulsion from the liver bed;

6. Finally, in the context of other procedures in cirrhotic patients, particularly those with ascites, the use of intraperitoneal drains should be eschewed [

25].

A 2020 study indicates that conversion to laparotomy occurs in 12.3% of individuals, with rates ranging from 0% to 20.8%. The predominant causes (

Table 1) included vesicular bed hemorrhage in 41.3% of patients, inadequate visualization of structures in 26.1%, the presence of adhesions in 13.0%, excessive inflammation precluding safe laparoscopic surgery in 6.5%, and other causes in 13.0% of patients [

5].

Robotic-assisted cholecystectomy (RC) provides superior dexterity, vision, and precision, rendering it especially beneficial in instances of anatomical distortion or vascular problems. Research comparing robotic-assisted surgery to laparoscopic procedures indicates similar or superior outcomes, including reduced operating durations and diminished conversion rates [

26,

27]. However, the expense and significant learning curve continue to impede wider usage [

28].

3.4. Subtotal Cholecistectomy

Subtotal cholecystectomy (SC) is acknowledged as a safe alternative to total cholecystectomy; however, the long-term outcomes for patients are influenced by the existence of residual stones in the gallbladder remains. The retention rate of stones ranges from 4% to 15% [

29,

30]. While the majority of residual stones may be extracted using ERCP, some patients still have to undergo reoperations [

31,

32]. The incidence of long-term problems following SC is greater than that following total cholecystectomy. For individuals who can exclusively undergo SC because to the local situation of the hepatocystic triangle, laparoscopic surgery yields superior outcomes compared to the open technique [

29].

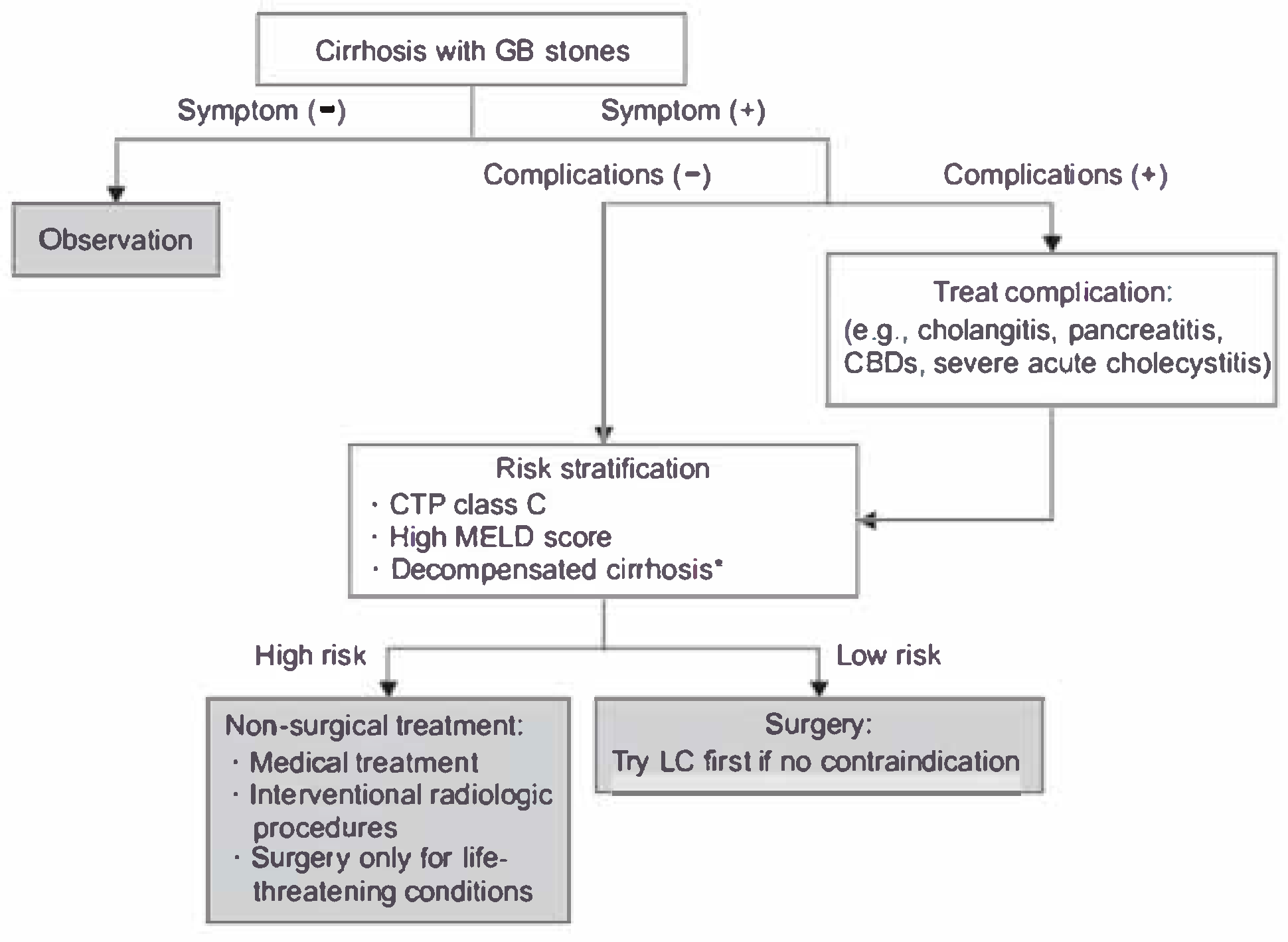

Figure 1.

Wang’s et al. proposed flowchart for the management of cirrhotic patients with cholelithiasis [

8].

Figure 1.

Wang’s et al. proposed flowchart for the management of cirrhotic patients with cholelithiasis [

8].

4. Cholecistectomy in Sclero-Atrophic Cholecystitis

4.1. Etiopathogenesis of Sclero-Atrophic Cholecystitis

Sclero-atrophic cholecystitis (SAC) is the terminal phase of chronic gallbladder inflammation, marked by extensive fibrosis, atrophy of the gallbladder wall, and occlusion of the lumen. This process arises from chronic irritation, primarily caused by gallstones or biliary sludge, which triggers and sustains the inflammatory cascade [

33].

The pathophysiology of SAC initiates with episodes of acute cholecystitis resulting from gallstones clogging the cystic duct. Repeated inflammatory episodes result in chronic cholecystitis, characterized by histological alterations including lymphocytic infiltration, glandular atrophy, and fibrosis [

34].

With time, the gallbladder becomes inflexible and functionally dormant, increasing the risk of problems such as secondary bacterial infections or gallbladder cancer [

35].

The advancement to sclero-atrophic alterations encompasses fibrogenesis, biliary sludge, ischemia, and dysregulation of the immune response. Chronic inflammation induces the activation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, resulting in excessive extracellular matrix accumulation and fibrosis of the gallbladder wall [

36]. Persistent irritation from biliary sludge, along with ischemia damage, intensifies tissue necrosis and fibrosis [

37]. Chronic inflammation distorts the immune response, fostering a loop of tissue damage and repair that results in irreversible fibrotic remodeling [

38].

SAC presents considerable diagnostic and surgical difficulties. The clinical appearance frequently resembles gallbladder cancer due to the presence of thicker, fibrotic walls observed on imaging. Thus, surgical intervention is often necessary for conclusive diagnosis and treatment [

35].

4.2. Surgical Considerations in Sclero-Atrophic Cholecystitis

SAC has distinct technical difficulties during cholecystectomy owing to significant fibrosis and thick adhesions. These pathological alterations stem from persistent inflammation, resulting in structural deformation of the gallbladder and adjacent tissues. The destruction of standard anatomical landmarks, such as Calot’s triangle, exacerbates dissection difficulties and heightens the likelihood of intraoperative problems [

39].

LC, the gold standard for gallbladder excision, is frequently more intricate in individuals with sacral agenesis. Dense fibrotic adhesions among the gallbladder, liver, and adjacent structures may hinder visualization and restrict access. These adhesions require careful dissection, prolonging operational duration and elevating the risk of bile duct damage [

40,

41,

42].

The probability of conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy is markedly elevated in instances of severe acute cholecystitis. Conversion is frequently necessary to effectively address complications such as hemorrhage or unintentional bile duct damage, which occur more frequently due to vascularized adhesions and modified anatomy [

43]. Conversion should not be viewed as failure but as a patient safety measure. In SAC, this decision should be made early rather than persisting with risky laparoscopic dissection.

High-resolution imaging techniques, such as MRI and CT, can assist in detecting significant adhesions and anticipating possible problems [

44].

Innovations in surgical technology, including energy devices and robotic systems, have enhanced dissection accuracy and diminished the likelihood of complications [

45].

The deformation of Calot’s triangle poses significant challenges in SAC scenarios. Fibrosis frequently amalgamates the gallbladder with neighboring structures such as the duodenum or colon, erasing essential anatomical landmarks [

41,

42]. Rouvière’s sulcus, while typically a dependable marker in most laparoscopic cholecystectomies, may become obscured in cases of severe inflammation, significantly increasing the risk of damaging the right hepatic artery or common bile duct [

42].

Attaining a critical view of safety (CVS) is crucial to avert bile duct damage, especially in complex situations exhibiting sclero-atrophic alterations [

46]. The systematic identification of the ‘B-SAFE’ landmarks and the application of Strasberg’s Critical View of Safety (CVS) are essential. When CVS is unattainable due to inflammation or fibrosis, different methodologies should be examined [

40].

Innovations in minimally invasive methods, such as laparoscopic surgical procedures, have been suggested as alternatives for the management of sacral agenesis. These methods seek to minimize problems while maintaining symptom management by preserving fibrotic sections of the gallbladder wall in anatomically complex situations [

47].

The Fundus-First (Dome-Down) Technique initiates dissection from the gallbladder fundus instead of the infundibulum, facilitating progressive dissection when Calot’s triangle is not accessible. In SAC, there exists a significant risk of accessing the wrong plane, which may result in vasculo-biliary damage if dissection occurs beneath the cystic plate [

42].

SC is identified as the most feasible bailout strategy. It facilitates gallbladder decompression and mitigates hazardous dissection in the vicinity of Calot’s triangle. SC can be categorized into: Reconstituting (Closure of the residual gallbladder, which poses a danger of retained stones) and Fenestrating (The residue is left open to facilitate external drainage, hence reducing the possibility of stone retention) [

40]. Both techniques have shown favorable outcomes in high-risk SAC patients.

The application of intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) or fluorescence-guided imaging utilizing indocyanine green (ICG) is strongly advised in SAC patients. These methods offer real-time viewing of biliary anatomy, hence diminishing the risk of bile duct injury (BDI) [

48]. In

Table 2, different techniques that could mitigate the surgical risks in case of SAC are shown.

RC has emerged as a viable method, providing improved accuracy, decreased conversion rates, and superior vision of the surgical region, which are especially beneficial in addressing this problem [

49].

5. Cholecistectomy in Gangrenous Cholecystitis

5.1. Pathogenesis and Risk Factors of Gangrenous Cholecystitis

Gangrenous cholecystitis (GC) is a critical and sometimes fatal consequence of acute cholecystitis, marked by ischemia necrosis of the gallbladder wall. The transition from acute cholecystitis to gangrene happens when sustained inflammation results in impaired arterial perfusion and ensuing ischemia. The pathophysiological process is intensified by elevated intraluminal pressure, bacterial infection, and microvascular thrombosis [

50].

Studies indicate that this ischemia cascade leads to transmural necrosis, deterioration of gallbladder wall integrity, and subsequent gangrene, which, if not addressed, may advance to perforation and peritonitis. Imaging investigations, including CT and ultrasound, frequently demonstrate gallbladder wall thickening, intraluminal membranes and pericholecystic fluid; however, these findings considerably overlap with other types of complex cholecystitis [

51].

GC is frequently underdiagnosed prior to surgery because of its clinical similarities with uncomplicated acute cholecystitis [

52,

53]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), albeit infrequently utilized in emergency contexts, offers intricate soft tissue contrast, aiding in the differentiation of empyema or perforation. Cross-sectional imaging is essential for prioritizing individuals in need of urgent intervention [

54].

The implementation of the Tokyo Guidelines 2018 (TG18) (

Table 3) facilitates classification into mild, moderate, and severe categories. Grade III (severe) gastrointestinal complications, accompanied by organ dysfunction, necessitate prompt intervention or, in specific instances, temporary drainage [

55,

56].

5.2. Surgical Strategies in Gangrenous Cholecystitis

Emergency cholecystectomy is frequently the treatment of choice for gallbladder difficulties due to the significant danger of severe, life-threatening issues such as gallbladder perforation and bile peritonitis. Timely surgical intervention, preferably within 72 hours of symptom onset, correlates with less morbidity and abbreviated hospitalizations relative to postponed treatments [

57].

Nonetheless, postponed cholecystectomy is often essential, especially in critically ill or high-risk patients for whom immediate surgery presents considerable anesthetic or surgical hazards. In such instances, initial care typically involves percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) or endoscopic gallbladder drainage (EGBD) as a temporary intervention, succeeded by elective surgery once the acute inflammation resolves [

19].

A study utilizing the TriNetX database indicated that surgical patients had superior 5-year survival rates compared to those managed conservatively, particularly when surgery was performed without delay beyond the initial inflammatory phase [

58].

Minimally invasive procedures, including LC and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD), have revolutionized the management of gallbladder cancer (GC), offering safer alternatives for patients with considerable comorbidities [

59].

LC is the conventional method for the majority of GC instances. It provides diminished postoperative discomfort, expedited recovery, and a lower incidence of complications relative to open surgery. Nonetheless, complications such as significant adhesions and anatomical deformation may require conversion to open surgery in 15–30% of instances [

20].

PTGBD is a beneficial alternative for patients ineligible for surgery due to severe sepsis, advanced age, or considerable comorbidities. It efficiently decompresses the gallbladder, hence stabilizing the patient for subsequent elective surgery. Research indicates similar success rates between percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) and early surgical intervention in high-risk patients, accompanied by reduced immediate procedural risks [

60].

Innovative methods like EGBD provide minimally invasive options for biliary decompression. EGBD employs endoscopic ultrasound guidance to position a stent or catheter, offering prompt relief for individuals with contraindications to percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) [

61].

The decision about emergency surgery, postponed surgery, or drainage methods must be customized according to the patient’s clinical condition and comorbidities. A collaborative strategy incorporating surgeons, radiologists and anesthesiologists is essential for enhancing outcomes. Studies indicate that early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the gold standard for stable patients, whereas percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage or endoscopic gallbladder drainage are critical interventions for unstable or high-risk patients [

62].

GC may progress to gallbladder perforation or emphysematous cholecystitis, which is marked by the presence of gas-forming organisms in the gallbladder wall. These are surgical emergencies with death rates up to 25% if left untreated [

52,

63]. Intraoperative observations frequently reveal necrotic lesions, bile-stained ascitic fluid, or perforations. Prompt cholecystectomy accompanied by comprehensive peritoneal lavage is required [

64,

65].

Mitsala et al. indicate that most gallbladder perforations (GBP) are detected intraoperatively and are efficiently addressed with rapid surgical intervention, especially in patients exhibiting localized peritonitis (Niemeier Type II) [

53].

6. Conclusions

Cholecystectomy remains a vital yet challenging surgical procedure, particularly when performed in complex clinical settings such as liver cirrhosis, SAC, and GC. This review highlights the intricacies of these conditions, underscoring the importance of individualized surgical planning and the integration of modern surgical techniques and imaging modalities.

In cirrhotic patients, preoperative optimization, careful patient selection based on liver function scores, and minimally invasive techniques—preferably laparoscopic or robotic—can significantly mitigate perioperative risks. When operating on sclero-atrophic gallbladders, distorted anatomy, fibrosis, and loss of landmarks necessitate advanced dissection strategies, including the fundus-first technique, SC, and the routine use of intraoperative imaging to reduce bile duct injuries. In GC, early surgical intervention remains the cornerstone of management; however, percutaneous or endoscopic drainage may be essential bridges in critically ill patients.

A multidisciplinary approach that integrates hepatology, anesthesia, and interventional radiology input is critical for optimizing patient safety and outcomes in these high-risk scenarios. Furthermore, emerging robotic and image-guided innovations offer promising avenues to enhance surgical precision in complex cholecystectomies. Future research should focus on refining risk stratification tools, expanding minimally invasive access, and evaluating long-term outcomes of alternative techniques such as subtotal and robotic assisted cholecystectomy.

Ultimately, tailoring the surgical approach to the specific pathophysiological context of each patient—not a one-size-fits-all technique—is fundamental to reducing morbidity and improving prognosis in difficult gallbladder surgeries.

Limitations of the Study

This review included only studies indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar. Expanding the search to additional web-based academic databases, such as Scopus, Web of Science and Embase may yield further insights into the nuances of cholecystectomy in patients with liver cirrhosis, sclero-atrophic cholecystitis, or acute gangrenous cholecystitis. It may also help identify emerging techniques and strategies to reduce perioperative risks in these complex clinical scenarios.

Author Contributions

All authors had equal contribution in the study.

Funding

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GC |

Gangrenous Cholecystitis |

| LC |

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

| PTGBD |

Percutaneous Transhepatic Gallbladder Drainage |

| OC |

Open Cholecystectomy |

| RC |

Robotic-Assisted Cholecystectomy |

| SAC |

Sclero-Atrophic Cholecystitis |

| CVS |

Critical View of Safety |

| SC |

Subtotal Cholecystectomy |

| IOC |

Intraoperative Cholangiography |

| ICG |

Fluorescence-Guided Imaging With Indocyanine Green |

| US |

Ultrasound |

References

- M. W. Jones, E. Guay, and J. G. Deppen, Open Cholecystectomy. 2024.

- S. O’Brien et al., “Adverse outcomes and short-term cost implications of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy,” Surg Endosc, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 628–635, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Stinton and E. A. Shaffer, “Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer,” Gut Liver, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 172–187, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Strasberg, “Clinical practice. Acute calculous cholecystitis.,” N Engl J Med, vol. 358, no. 26, pp. 2804–11, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

- F. Cauchy, E. Vibert, and L. Barbier, “What are the Specifics of Biliary Surgery in Cirrhotic Patients?,” Chirurgia (Bucur), vol. 115, no. 2, pp. 191–207, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, D. Liu, Q. Ma, C. Dang, W. Wei, and W. Chen, “Factors influencing the prevalence of gallstones in liver cirrhosis,” J Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 21, no. 9, pp. 060616025538010-???, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Acalovschi, “Gallstones in patients with liver cirrhosis: Incidence, etiology, clinical and therapeutical aspects,” World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG, vol. 20, no. 23, p. 7277, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Wang, C. N. Yeh, Y. Y. Jan, and M. F. Chen, “Management of Gallstones and Acute Cholecystitis in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis: What Should We Consider When Performing Surgery?,” Gut Liver, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 517, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Abbas, J. Makker, H. Abbas, and B. Balar, “Perioperative Care of Patients With Liver Cirrhosis: A Review,”vol. 10, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Carpenter, P. Liou, and A. Mathur, “Management of Patients with Cirrhosis and Portal Hypertension Requiring Surgery,” Dig Dis Interv, vol. 04, no. 02, pp. 168–179, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Harmouch and M. J. Hobeika, “Perioperative Management of the Cirrhotic Patient,” Common Problems in Acute Care Surgery, pp. 43–54, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Rai, S. Nagral, and A. Nagral, “Surgery in a Patient with Liver Disease,” J Clin Exp Hepatol, vol. 2, no. 3, p. 238, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Pinheiro et al., “Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and cirrhosis: patient selection and technical considerations,” Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 35–35, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. T. Nguyen et al., “Cirrhosis is not a contraindication to laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Results and practical recommendations,” HPB, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 192–197, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Delis, A. Bakoyiannis, J. Madariaga, J. Bramis, N. Tassopoulos, and C. Dervenis, “Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients: The value of MELD score and ChildPugh classification in predicting outcome,” Surg Endosc, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 407–412, 2010. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Diaz and T. D. Schiano, “Evaluation and Management of Cirrhotic Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery,” Curr Gastroenterol Rep, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 1–11, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Puggioni and L. L. Wong, “A metaanalysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with cirrhosis,” J Am Coll Surg, vol. 197, no. 6, pp. 921–926, Dec. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Adiamah, C. J. Crooks, J. S. Hammond, P. Jepsen, J. West, and D. J. Humes, “Cholecystectomy in patients with cirrhosis: a population-based cohort study from England,” HPB, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 189–197, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Ke and S. D. Wu, “Comparison of Emergency Cholecystectomy with Delayed Cholecystectomy After Percutaneous Transhepatic Gallbladder Drainage in Patients with Moderate Acute Cholecystitis,” https://home.liebertpub.com/lap, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 705–712, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Z. Huang et al., “Comparison of emergency cholecystectomy and delayed cholecystectomy after percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Updates Surg, vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 481–494, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Palanivelu et al., “Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in Cirrhotic Patients: The Role of Subtotal Cholecystectomy and Its Variants,” J Am Coll Surg, vol. 203, no. 2, pp. 145–151, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. Aziz et al., “A potential role for robotic cholecystectomy in patients with advanced liver disease: Analysis of the NSQIP database,” American Surgeon, vol. 86, no. 4, pp. 341–345, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Aziz, K. Hanna, N. Lashkari, N. U. S. Ahmad, Y. Genyk, and M. R. Sheikh, “Hospitalization Costs and Outcomes of Open, Laparoscopic, and Robotic Liver Resections,” American Surgeon, vol. 88, no. 9, pp. 2331–2337, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Wong and R. W. Busuttil, “Surgery in Patients with Portal Hypertension,” Clin Liver Dis, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 755–780, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Cassinotti, L. Baldari, L. Boni, S. Uranues, and A. Fingerhut, “Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in the Cirrhotic: Review of Literature on Indications and Technique,” Chirurgia (Bucur), vol. 115, no. 2, p. 208, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Aziz et al., “A potential role for robotic cholecystectomy in patients with advanced liver disease: Analysis of the NSQIP database,” American Surgeon, vol. 86, no. 4, pp. 341–345, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M. Ito, and A. K. Lefor, “Laparoscopic and Robot-Assisted Hepatic Surgery: An Historical Review,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, Vol. 11, Page 3254, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 3254, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, J. P. Sijberden, and M. A. Hilal, “What Is the Current Role and What Are the Prospects of the Robotic Approach in Liver Surgery?,” Cancers 2022, Vol. 14, Page 4268, vol. 14, no. 17, p. 4268, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Elshaer, G. Gravante, K. Thomas, R. Sorge, S. Al-Hamali, and H. Ebdewi, “Subtotal cholecystectomy for ‘Difficult gallbladders’: Systematic review and meta-analysis,” JAMA Surg, vol. 150, no. 2, pp. 159–168, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kohga et al., “Calculus left in remnant gallbladder cause long-term complications in patients undergoing subtotal cholecystectomy,” HPB, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 508–514, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- W. M. Tay et al., “Subtotal cholecystectomy: early and long-term outcomes,” Surg Endosc, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 4536–4542, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. van Dijk et al., “Short- and Long-Term Outcomes after a Reconstituting and Fenestrating Subtotal Cholecystectomy,” J Am Coll Surg, vol. 225, no. 3, pp. 371–379, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Meirelles-Costa, C. J. C. Bresciani, R. O. Perez, B. H. Bresciani, S. A. C. Siqueira, and I. Cecconello, “Are histological alterations observed in the gallbladder precancerous lesions?,” Clinics, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 143–150, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Zemour, M. Marty, B. Lapuyade, D. Collet, and L. Chiche, “Gallbladder tumor and pseudotumor: Diagnosis and management,” J Visc Surg, vol. 151, no. 4, pp. 289–300, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. de Paula Reis Guimarães et al., “A comprehensive exploration of gallbladder health: from common to rare imaging findings,” Abdominal Radiology, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 131–151, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. K. B., V. Reddy, S. R. V., R. M. C., and J. Koneru, “A study of clinical presentations and management of cholelithiasis,” International Surgery Journal, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 2164–2167, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Beuran, I. Ivanov, and M. D. Venter, “Gallstone Ileus–Clinical and therapeutic aspects,” J Med Life, vol. 3, no. 4, p. 365, Oct. 2010. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3019077/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ferrozzi, G. Garlaschi, and D. Bova, “Anatomical Sites of Metastatic Colonization,” CT of Metastases, pp. 27–80, 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. Akoǧlu, M. Ercan, E. B. Bostanci, Z. Teke, and E. Parlak, “Surgical outcomes of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in scleroatrophic gallbladders,” Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 156–162, Jun. 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Montalvo-Javé, E. A. Ayala-Moreno, E. H. Contreras-Flores, and M. A. Mercado, “Strasberg’s Critical View: Strategy for a Safe Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy,” Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 40–44, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Abdallah, M. H. Sedky, and Z. H. Sedky, “The difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a narrative review,” BMC Surg, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Missori, F. Serra, and R. Gelmini, “A narrative review about difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy: technical tips,” Laparosc Surg, vol. 6, no. 0, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Duca et al., “Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Incidents and complications. A retrospective analysis of 9542 consecutive laparoscopic operations,” HPB, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 152–158, Aug. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Fingerhut, P. Shukla, M. Soltès, and I. Khatkov, “Cholecystectomy for Complicated Biliary Disease of the Gallbladder,” Emergency Surgery Course (ESC®) Manual: The Official ESTES/AAST Guide, pp. 139–145, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Kapoor, “Mechanisms of Causation of Bile Duct Injury,” Post-cholecystectomy Bile Duct Injury, pp. 21–35, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Iwashita et al., “Delphi consensus on bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an evolutionary cul-de-sac or the birth pangs of a new technical framework?,” J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 591–602, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Peker and H. Aliş, “Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy could be an alternative to conversion,” Medical Journal of Bakirkoy, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 113–117, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Iwashita et al., “Delphi consensus on bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an evolutionary cul-de-sac or the birth pangs of a new technical framework?,” J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 591–602, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Zaman and T. P. Singh, “The emerging role for robotics in cholecystectomy: the dawn of a new era?,” Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 21, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Önder, M. Kapan, B. V. Ülger, A. Oǧuz, A. Türkoǧlu, and Ö. Uslukaya, “Gangrenous Cholecystitis: Mortality and Risk Factors,” Int Surg, vol. 100, no. 2, pp. 254–260, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. G. Marinova, “Predictors for Gangrene and Perforation of Gallbladder Wall in Patients with Acute Cholecystitis,” Journal of Biomedical and Clinical Research, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 146–152, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Fabbri et al., “Enhancing the management of acute and gangrenous cholecystitis: a systematic review supported by the TriNetX database,” Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 10, no. 0, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tsalikidis et al., “Gallbladder perforation. A case series and review of the literature.,” Ann Ital Chir, vol. 91, Dec. 2020.

- V. Gupta et al., “The Multifaceted Impact of Gallstones: Understanding Complications and Management Strategies,” Cureus, vol. 16, no. 6, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Yokoe et al., “Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos),” J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 41–54, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Loozen, M. M. Blessing, B. van Ramshorst, H. C. van Santvoort, and D. Boerma, “The optimal treatment of patients with mild and moderate acute cholecystitis: time for a revision of the Tokyo Guidelines,” Surg Endosc, vol. 31, no. 10, pp. 3858–3863, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Pisano et al., “2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis,” World Journal of Emergency Surgery 2020 15:1, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–26, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Fabbri et al., “Enhancing the management of acute and gangrenous cholecystitis: a systematic review supported by the TriNetX database,” Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 10, no. 0, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Oh, E. Kim, E. J. Ahn, J.-M. Park, and and S.-H. Park, “The Benefits of Percutaneous Transhepatic Gallbladder Drainage prior to Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for Acute Cholecystitis,” Journal of Minimally Invasive Surgery, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 63–69, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Melloul, A. Denys, N. Demartines, J. M. Calmes, and M. Schäfer, “Percutaneous drainage versus emergency cholecystectomy for the treatment of acute cholecystitis in critically Ill patients: Does it matter?,” World J Surg, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 826–833, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Morcos et al., “Outcomes of Gallbladder Drainage Techniques in Acute Cholecystitis: Percutaneous Versus Endoscopic Methods,” Cureus, vol. 16, no. 11, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Navuluri, M. Hoyer, M. Osman, and J. Fergus, “Emergent Treatment of Acute Cholangitis and Acute Cholecystitis,” Semin Intervent Radiol, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 14–23, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, Q. Chen, Y. Hu, L. Zhao, P. Cai, and S. Guo, “Cholecystopleural fistula: A case report and literature review,” Medicine (United States), vol. 103, no. 33, p. e39366, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H.R, “Narrative Review on Complicated Cholecystitis: An Update on Management,” Asian Journal of Medicine and Health, vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 98–105, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nve, J. M. Badia, M. Amillo-Zaragüeta, M. Juvany, M. Mourelo-Fariña, and R. Jorba, “Early Management of Severe Biliary Infection in the Era of the Tokyo Guidelines,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, Vol. 12, Page 4711, vol. 12, no. 14, p. 4711, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).